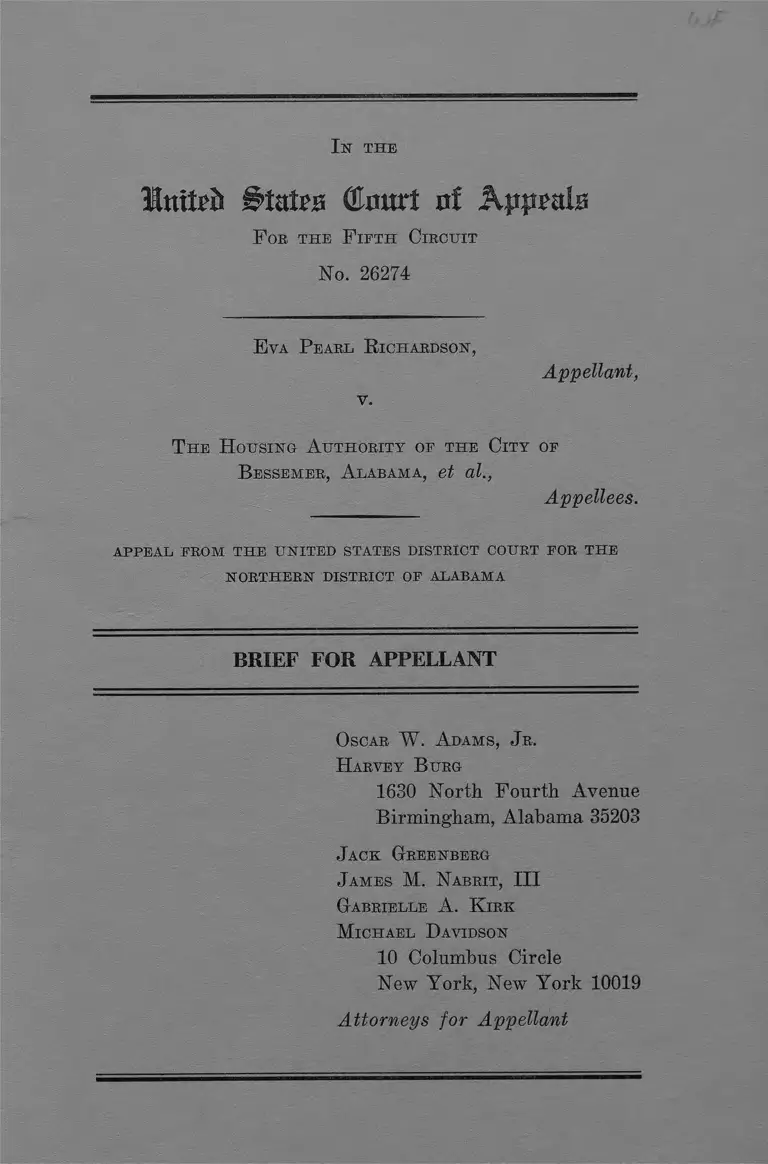

Richardson v The Housing Authority of the City of Bessemer Alabama Brief Appellant

Public Court Documents

July 12, 1968

48 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Richardson v The Housing Authority of the City of Bessemer Alabama Brief Appellant, 1968. 3a45a031-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b0eeec9d-63bf-405b-bf2d-c289fb76b81a/richardson-v-the-housing-authority-of-the-city-of-bessemer-alabama-brief-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

Unittb £>tatru Court of Kppmb

F ob the F ifth Circuit

No. 26274

E va Pearl R ichardson,

v.

Appellant,

T he H ousing A uthority of the City of

B essemer, A labama, et al.,

Appellees.

A P PE A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTRICT COURT FOR T H E

N O R T H E R N D ISTRICT OF ALAB A M A

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Oscar W . A dams, Jr .

Harvey B urg

1630 North Fourth Avenue

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Jack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Gabrielle A. K irk

Michael Davidson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellant

I N D E X

Statement of tlie Case ............ .......................................... 1

Specification of Errors ...................................................... 5

Argument:

I. The Constitution Prohibits Arbitrary, Dis

criminatory or Capricious Action by the Hous

ing Authority in Terminating a Tenant’s Ben

efits Under the Public Housing Laws ........... 6

A. A Public Housing Authority Can Only

Evict Its Tenants for Constitutionally

Permitted Reasons ......................................... 6

B. A Tenant in a Public Housing Project

Is Entitled to Notice of the Reasons for

Eviction.................................... 13

C. A Tenant in a Public Housing Project

Is Entitled to a Pair Hearing Prior to

Eviction ......... 16

II. The Housing Authority’s Asserted Compliance

With the February 7, 1967 Circular Does Not

Comport With the Guarantees of the Con

stitution .................................................................. 21

Conclusion ..................................................... 23

Certificate of Service ........................................................ 24

Appendix:

Opinion of the Court of Appeals ........................... la

Order of Temporary Injunction ...... 14a

PAGE

11

T able of Cases

page

Banks v. Housing Authority of City and County of

San Francisco, 120 Cal.App.2d 1, 260 P.2d 668

(1953), cert, denied 347 U.S. 974 ............................... 6

Berman v. Parker, 348 U.S. 26 ....................................... 19

Chicago Housing Authority v. Blackman, 4 111. 2d 319,

122 N.E,2d 522 (1954) .................................................. 8

Detroit Housing Commission v. Lewis, 226 F.2d 180

(6th Cir. 1955) .............................................................. 6

Dixon v. Alabama State Bd. of Ed., 294 F.2d 150

(5th Cir. 1961), cert, denied, 368 U.S. 930 ....11,15,16,18

Frost Trucking Co. v. R.R. Comm., 271 U.S. 583 ....... 7

Goldsmith v. United States Board of Tax Appeals,

270 U.S. 117 ...................................................................... 17

Gonzales v. Freeman, 334 F.2d 570 (D.C. Cir. 1964) ....16,18

Gonzales v. United States, 348 U.S. 407 ....................... 15

Greene v. McElroy, 360 U.S. 474 ................................... 17

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 ............................ 12

Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Ry. Co. v. Ellis, 165 U.S.

150 ...................................................................................... 8,13

Hanover Fire Insurance Co. v. Carr, 272 U.S. 494 .... 7

Harper v. Virginia State Bd. of Elections, 383 U.S.

663 ...................................................................................... 8

Holmes v. New York City Housing Authority, No.

31972 (2nd Cir., July 18, 1968) .............................. 8-9,13

Holt v. Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Au

thority, 266 F. Supp. 397 (E.D. Va. 1966) ...............8,14

Hornsby v. Allen, 326 F.2d 605 (5th Cir. 1964) ...........16,18

Ill

Housing Authority of Los Angeles v. Cordova, 130

Cal.App.2d 883, 279 P.2d 215 (App. Dept. Super.

Ct. 1955) .............. .■.............................................. ........... 8

In the Matter of Yinson v. Greenburgh Housing Au

thority, 29 App.Div.2d 338, 288 N.Y.S.2d 159 (1968) 11

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm. v. McGrath, 341

U.S. 123 ....................................... ..................................15,18

Jones v. City of Hamtramck, 121 F. Supp. 123 (E.D.

Mich. 1954) .......................................... ........................... 6

Jordan v. American Eagle Fire Insurance Co., 169

F.2d 281 (D.C. Cir. 1948) .......................................... 21, 22

PAGE

Keyishian v. Board of Regents of the University of

the State of New York, 385 U.S. 589 ........................... 17

Kutcher v. Housing Authority of Newark, 20 N.J. 181,

119 A.2d 1 (1955) .......................................................... 8

Lawson v. Housing Authority of City of Milwaukee,

270 Wise. 269, 70 N.W.2d 605 (1955), cert, denied

350 U.S. 882 ......... ...... .................................................. 8

Londoner v. Denver, 210 U.S. 373 ....................... 11,17, 22

Morgan v. United States, 304 U.S. 1 ........................... 15,17

Quevedo v. Collins et al., C.A. 3-2626-C (N.D. Tex.,

July 12, 1968) .................................................................. 18

Rudder v. United States, 226 F.2d 51 (D.C. Cir.

1955) ............................................ ................................8,11,13

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 .................................. 7,17

Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 .................................. 7,17

Simmons v. United States, 348 U.S. 397 ....................... 15

IV

Slochower v. Board of Higher Education, 350 U.S.

PAGE

551 ......................................................................................7,18

Southern R. Co. v. Virginia, 290 U.S. 190 ................... 17

Specht v. Patterson, 386 U.S. 605 ................................... 22

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 ................................... 17

Taylor v. Leonard, 30 N.J. Super. 116, 103 A.2d 632

(1954) ................................................................................ 6

Thomas v. Housing Authority of the City of Little

Rock, 282 F. Supp. 575 (E.D. Ark. 1967) ............... 8

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Durham,

No. 20, Oct. Term 1968 .................................................. 6

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Durham,

386 U.S. 670 ...................................................................... 9,13

Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488 ................................... 7

Tucker v. Texas, 326 U.S. 517 ....................................... 12

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 7 5 ........... 7

V ann v. Toledo Metropolitan Housing Authority, 113

F. Supp. 210 (N.D. Ohio 1953) ................................... 6

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 ...............................7,17

Willner v. Committee on Character and Fitness, 373

U.S. 9 6 ........................................................... ...... 15,17, 21, 22

Wong Yang Sung v. McGrath, 339 U.S. 33 ................... 17

Statutes

24 C.F.R. Subtitle A, Part I .......................................... 7

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VI, 78 Stat. 252, 42

U.S.C. Sec. 2000d .......................................................... 6

Civil Rights Act of 1968, Title VIII, 82 Stat. 81

(April 11, 1968) ............ .......... ....................................... 7

V

Code of Alabama, Title 25, § 5 ....................................... 10

Executive Order No. 11063, 27 Fed. Reg. 11527 (1962) 6

42 U.S.C. §§ 1401 et seq.................................................5, 9,10

42 U.S.C. § 1404a ................................................................ 10

42 U.S.C. § 1410(g)( 3 ) .............. ......................................... 10

Other A uthorities

1 Davis, Administrative Law Treatise, Sec. 8.05 ....... 16

Gellliorn and Byse, Administrative Law, Cases and

Comments (1960) ........ 16

Note, Public Landlords and Private Tenants: The

Eviction of “ Undesirables” From Public Housing

Projects, 77 Yale L.J. 988 (1968) .............................. 20

O’Neil, Unconstitutional Conditions: Welfare Bene

fits With Strings Attached, 54 Calif. L. Rev. 443

(1966) ................................................................................ 7

Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil

Disorders (Bantam ed. 1968) .......... 19

Rosen, Tenants’ Rights in Public Housing, “Housing

for the Poor: Rights and Remedies,” Project in

Social Welfare Law, Supp. No. 1, N.Y.TT. School

of Law, New York, N. Y. (1967) .............................. 20

PAGE

I n' th e

Inttfd #tat£g (Emirt of Appeals

F or the F ifth Circhit

No. 26274

E va P earl R ichardson,

v.

Appellant,

T he H ousing A uthority of the City of

B essemer, A labama, et al.,

Appellees.

appeal from the united states district court for the

N O R T H E R N DISTRICT OF AL A B A M A

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Statement of the Case

On October 12, 1966, appellant Mrs. Eva Pearl Richard

son, a Negro, became a tenant in one of the public housing

projects in the City of Bessemer. This project is a fed

erally assisted low-rent public housing project owned and

operated by the Housing Authority of Bessemer, Alabama,

a state agency (R. 4-8). On February 17, 1967, appellant

received a notice from appellee cancelling her lease as of

March 1, 1967 (R. 49, 74). At no prior time to the is

suance of this notice to vacate was appellant notified of

the reason for the cancellation nor was she given an op-

2

portunity to explain any conduct upon which the housing

authority might have relied to issue these notices, although

appellant, in person and by her attorney, requested the

authority to state the reason for the termination (R. 76).

On March 1, 1967, appellant filed a complaint, motion

for temporary restraining order and a motion for prelim

inary injunction in the United States District Court for

the Northern District of Alabama, Southern Division, seek

ing injunctive and declarative relief (R. 6, 17 and 19).

On March 1, 1967, the Honorable H. H. Grooms entered

an order restraining the housing authority from evicting

or threatening to evict the appellant (R. 21). Oh March 7,

1967, the district court continued the temporary restrain

ing order until April 3, 1967. On February 12, 1968, this

cause came on for trial (R. 23).

At his deposition, Mr. A. W. Kuhn, Executive Director

and Secretary of the Housing Authority, testified that

appellant had never been given a reason for the can

cellation of her lease (R. 30). However, at the time of

the trial, Mr. Kuhn stated that after the notices were

issued to appellant, she “came to the office and in an in

direct way was told of the reasons why we were taking

this action” (R. 80).

The complete reason for the cancellation of her lease

has not yet been given appellant. Mr. Kuhn stated that

the “ tenant [appellant] was becoming troublesome to the

community” (R. 34) and on the basis of inter-office memo

randums and as a result of contacts with the tenants, the

housing authority began an investigation and finally dis

covered that a contractor fired an employee who visited

Mrs. Richardson in her apartment during working hours.

All of the complaints received by the housing authority

were oral—either in person or in the form of telephone

3

calls. Mrs. Richardson was never given the names of

the persons who made the complaints and was not given

an opportunity to confront these persons or explain her

conduct (R. 34-35).

Appellant, at the time she received the notices of can

cellation, satisfied all the requirements for admission and

continued occupancy in the housing project (R. 29). The

housing authority relied on the provision of the lease

which permits the management to terminate the lease by

giving the tenant 10 days prior notice in writing (R. 33).

Since 1963 or 1964, the housing authority has maintained

a policy fep not advising tenants of the reasons for their

eviction because it has found that it is extremely difficult

to point out the reasons for the lease cancellation and be

cause the tenant would argue with the housing authority

and either deny or otherwise refuse to accept the reasons

given them (R. 31-32).

On February 7, 1967, the Department of Housing and

Urban Development issued a circular to all public housing

projects receiving federal funds declaring:

Since this is a federally assisted program, we believe

it is essential that no tenant be given notice to vacate

without being told by the Local Authority, in a private

conference or other appropriate manner, the reasons

for the eviction, and given an opportunity to make

such reply or explanation as he may wish.

In addition to informing the tenant of the reason(s)

for any proposed eviction action, from this date each

Local Authority shall maintain a written record of

every eviction from its federally assisted public hous

ing. Such records are to be available for review from

time to time by HUD representatives and shall contain

the following information:

4

1. Name of tenant and identification of unit occupied.

2. Date of notice to vacate.

3. Specific reason(s) for notice to vacate. For ex

ample, if a tenant is being evicted because of un

desirable actions, the record should detail the ac

tions which resulted in the determination that

eviction should be instituted.

4. Date and method of notifying tenant with summary

of any conferences with tenant, including names of

conference participants.

5. Date and description of final action taken.

The appellee housing authority received this circular on

or about February 15, 1967 (R. 66). However, the housing

authority did not comply with this circular in the issuance

of the notice of cancellation to appellant (R. 51). Since

the circular had been issued, the housing authority, at the

time of trial, had not evicted any tenant for other than

non-payment of rent. One eviction for misrepresentation

was pending (R. 87). The Executive Director of the Hous

ing Authority testified that the authority would comply

with the circular in all future evictions (R. 111). However,

no written notice of the reasons for eviction would be

given a tenant (R. 107), and the authority would not

permit any person (neither an attorney nor any lay per

son) to accompany the tenant at the conference notifying

the tenant of the reason for the eviction (R. 109).

On February 12, 1968, an order was entered and filed

directing the Housing Authority to comply with the terms

and provisions of the circular; dissolving the temporary

restraining order; denying injunctive relief sought by ap

pellant ; retaining jurisdiction of the cause to determine

compliance by the Housing Authority with the circular in

5

any future evictions of appellant and taxing costs against

the Housing Authority (It. 53). Notice of appeal was filed

on March 13, 1968 (R. 54).

Specification of Errors

1. The court below erred in denying appellants an in

junction enjoining the appellee housing authority from

evicting or threatening to evict tenants living in any one

of its public housing projects without first notifying them

of the reasons for the eviction and giving them a fair

hearing on the alleged charges prior to the eviction. 2

2. The court below erred in denying appellants a declara

tory judgment that the appellee housing authority’s policy

and practice of evicting or threatening to evict tenants

without first notifying them of the reasons for the eviction

and giving them a fair hearing on the alleged charges prior

to the eviction violates rights secured by the due process

and equal protection clauses of the Constitution of the

United States and by the United States Housing Act,

42 U.S.C. §§1401 et seq.

6

ARGUMENT

I.

The Constitution Prohibits Arbitrary, Discriminatory

or Capricious Action by the Housing Authority in Ter

minating a Tenant’s Benefits Under the Public Housing

Laws.1 2

A. A Public Housing Authority Can Only Evict Its Tenants

for Constitutionally-Permitted Reasons.

The Housing Authority of the City of Bessemer, a fed

erally assisted low-rent public housing project, is subject

to constitutional limitations, for the government, acting

as landlord, dispenser of benefits or in any other capacity,

must not contravene guarantees of the Constitution. It is

manifest, for example, that denial of benefits on the ground

of race violates the Constitution. This principle has fre

quently been applied to racial discrimination in public

housing, despite the government’s status as “ landlord.”

Detroit Housing Commission v. Lewis, 226 F.2d 180 (6th

Cir. 1955); Jones v. City of Hamtramck, 121 F. Supp.

123 (E.D. Mich. 1954); Vann v. Toledo Metropolitan Hous

ing Authority, 113 F. Supp. 210 (N.D. Ohio 1953); Banks

v. Housing Authority of City and County of San Francisco,

120 Cal. App.2d 1, 260 P.2d 668 (1953), cert, denied, 347

U.S. 974; Taylor v. Leonard, 30 N.J. Super. 116, 103 A.2d

632 (1954).2

1 See Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Durham, No.

20, October Term, 1968 pending before the Supreme Court of

the United States; scheduled for oral argument on October 22,

1968.

2 See also, Executive Order No. 11063, 27 Fed. Reg. 11527

(1962), prohibiting racial discrimination in federally-assisted hous

ing; Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 252, 42

7

Similarly, the government may not, in any capacity,

place conditions upon providing benefits which operate to

deter or infringe the exercise of rights and freedoms

guaranteed by the Constitution. See, e.g., Sherbert v.

Verner, 374 U.S. 398, 404, where the Supreme Court stated

(with respect to the denial of unemployment compensa

tion) :

It is too late in the day to doubt that the liberties

of religion and expression may be infringed by the

denial of or placing of conditions upon a benefit or

privilege. American Communications Ass’n. v. Douds,

339 U.S. 382, 390; Wiemann v. Updegraff, 344 U.S.

183, 191, 192; Hannegan v. Esquire, Inc., 327 U.S. 146,

155, 156 . . . In Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513,

we emphasized that conditions upon public benefits

cannot be sustained if they so operate, whatever their

purpose, as to inhibit or deter the exercise of First

Amendment freedoms. (Emphasis added.)3

This principle, too, has been applied to public housing.

It has been held that public housing authorities may not

deny the benefits of public housing to persons solely be

U.S.C., See. 2000d, and the implementing regulations (24 C.F.R.,

Subtitle A, Part I), prohibiting discrimination in federally-assisted

programs, including low-rent housing projects; and Title VIII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1968, 82 Stat. 81 (April 11, 1968).

3 The doctrine prohibiting the imposition of unconstitutional

conditions is not limited to the above cases, Torcaso v. Watkins,

367 U.S. 488; Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479; United Public

Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 75, 100; Slochower v. Board of

Higher Education, 350 U.S. 551, 555; Wiemann v. Updegraff, 344

U.S. 183, 191 (all public employment), or to cases involving the

First Amendment. See, e.g., Frost Trucking Co. v. R. R. Comm.,

271 U.S. 583 (use of public highways); Hanover Fire Insurance

Co. v. Carr, 272 U.S. 494 (foreign corporations doing business in

a State). See generally, O'Neil, Unconstitutional Conditions: Wel

fare Benefits With Strings Attached, 54 Calif. L. Rev. 443 (1966).

8

cause of their exercise of guaranteed rights of free speech

and association. Holt v. Richmond Redevelopment and

Housing Authority, 266 F. Supp. 397 (E.D. Ya. 1966);

Rudder v. United States, 226 F.2d 51 (D.C. Cir. 1955);

Kutcher v. Housing Authority of Newark, 20 N.J. 181, 119

A.2d 1 (1955); Housing Authority of Los Angeles v. Cor

dova, 130 Cal. App.2d 883, 279 P.2d 215 (App. Dep’t.

Super. Ct. 1955); Lawson v. Housing Authority of City

of Milwaukee, 270 Wis. 269, 70 N.W.2d 605 (1955); cert,

denied, 350 U.S. 882; Chicago Housing Authority v. Stock

man, 4 I11.2d 319, 122 N.E.2d 522 (1954).

Moreover, the Fourteenth Amendment requires that the

action of government be rationally related to the purposes

of the legislation. Thus, in Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe

Ry. v. Ellis, 165 U.S. 150, 155, the Supreme Court held that

a classification:

. . . must always rest upon some difference which

bears a reasonable and just relation to the act in

respect to which the classification is proposed, and

can never be made arbitrarily and without any such

basis.

See also, Harper v. Virginia State Ed. of Elections, 383

U.S. 663. This principle, too, is applicable to public hous

ing. Action taken to deny the benefits of low-income hous

ing must be rationally related to that purpose or its

implementation. Thus, in Thomas v. Housing Authority of

the City of Little Rock, 282 F. Supp. 575 (E.D. Ark. 1967),

the housing authority’s action denying access to public

housing on the ground that the applicant had an illegiti

mate child was held unconstitutional in that there was no

rational connection between that ground and the purposes

of the legislation. Likewise in Holmes v. New York City

9

Housing Authority, No. 31972 (2nd Cir., July 18, 1968)

a Court of Appeals held:

It hardly need be said that the existence of an ab

solute and uncontrolled discretion in an agency of

government vested with the administration of a vast

program, such as public housing would be an in

tolerable invitation to abuse.

The expressed purposes of the state-federal low-income

housing program is:

. . . to promote the general welfare of the Nation by

employing its fund and credit, . . . to assist the sev

eral States and their political subdivisions to alleviate

present and recurring unemployment and to remedy

the unsafe and insanitary housing conditions and the

acute shortage of decent, safe, and sanitary dwellings

for families of low income, in urban and rural non

farm areas, that are injurious to the health, safety,

and morals of the citizens of the Nation. 42 TJ.S.C.

§1401.

The program is an exercise of the general governmental

power to protect the health, safety, and welfare of an

economically disadvantaged segment of the citizenry. The

initiation of the program rested on explicit recognition

of the fact that without public housing large numbers of

persons would be condemned to live in urban and rural

slums, suffering all the indignities and despair stemming

from unsafe, overcrowded and unsanitary dwellings.

Surely, the power to exclude persons arbitrarily and with

out reason from the benefits of the housing program cannot

be reconciled with these enunciated purposes and concerns.

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Durham, 386

U.S. 670.

1 0

This conclusion is supported by the fact that there is

nothing in either the federal4 or state acts creating the

publicly supported low-income housing program adminis

tered by the Housing Authority which confers such an

arbitrary power to evict or otherwise withhold the benefits

of the program. Neither of the two provisions of the

federal law which authorize the local agencies to require

tenants to move from low-income projects (42 U.S.C.

§1410(g) (3) and 42 U.S.C. §1404a) grants arbitrary power;

both provisions are related to a policy of limiting occu

pancy to low-income families. Likewise, the policy of the

State of Alabama is to provide:

safe, sanitary and uncongested dwelling accommoda

tions at such rentals that persons who now live in

unsafe or unsanitary or congested dwelling accom

modations can afford to live in safe, sanitary and un

congested dwellings. . . . Code of Alabama, Tit. 25, §5.

Nor are there any existing administrative regulations un

der either the federal or state legislation which confer

the power to evict without accountability. The only ad

ministrative pronouncement directly bearing on the prob

lem is the HUD circular of February 7, 1967, which re

quires local authorities to afford tenants notice and an

opportunity to be heard.

Finally, government action affecting vital interests may

not be arbitrary in the sense of being without factual

foundation. The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

stated, with regard to school expulsions:

The possibility of arbitrary action is not excluded by

the existence of reasonable regulations. There may be

arbitrary application of the rule to the facts of a

4 The United States Housing Act of 1937, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

§1401 et seq.

11

particular case. Dixon v. Alabama State Bd. of Educ.,

294 F.2d 150, 157 (5th Cir. 1961), cert, denied 368

U.S. 930.

Thus, even if a legitimate reason is advanced for denial

of a benefit, due process requires that there be a factual

foundation making the reason applicable to the specific

individual. This principle, too, has been applied to public

housing:

The government as landlord is still the government.

It must not act arbitrarily, for, unlike private land

lords it is subject to the requirements of due process

of law. Arbitrary action is not due process. Rudder

v. United States, 226 F.2d 51, 53 (D.C. Cir. 1955).

See, In the Matter of Vinson v. Greenburgh Housing Au

thority, 29 App. Div. 2d 338, 288 N.Y.S.2d 159 (1968),

holding on constitutional grounds, that notice of reasons

for an eviction must be given. Indeed, it is the principle

forbidding arbitrary action which serves as the logical

premise for the general rule that administrative and judi

cial determinations be supported by “ evidence” after notice

and a hearing on the issues. Cf. Londoner v. Denver, 210

U.S. 373.

The question here is whether, under these vital consti

tutional principles, a government agency may evict for

no reason at all, i.e. reliance upon the lease provision

permitting the management to cancel the lease upon

10 days notice or for an unreasonable, arbitrary and

capricious reason. The answer to that question must be

negative if there is to be any protection at all for the

civil rights and civil liberties of public housing tenants.

Rudder v. United States, 226 F.2d 51 (D.C. Cir. 1955).

Otherwise, housing project managers would be granted

12

“ full authority to regulate the conduct of those living in

the [project].” Tucker v. Texas, 326 U.S. 517, 519.

Additionally, the February 7, 1967 circular now requires

housing authorities to notify tenants of the reason for

evictions. Thus, appellee’s policy of relying on its lease

cancellation power on 10 days notice is no longer per

missible. It is also submitted that the Housing Authority

may not constitutionally evict appellant on the basis of

the reasons which it has asserted.

All of the complaints received by the Housing Authority

against appellant have been oral—either in person or over

the telephone (R. 34-35). The Executive Director does not

remember the names of any persons in the project who

have made complaints against appellant (R. 83). Yet, he

reached the decision that Mrs. Richardson has disturbed

the community and neighbors (R. 36). The single com

plaint that has been specified is not a complaint against

Mrs. Richardson, but against an employee of the contractor

who allegedly was fired because he visited appellant dur

ing working hours (R. 34). The Executive Director has

not been able to give the name of either the contractor

or the employee who was fired. Thus, the Housing Au

thority has failed factually to give a reason for appellant’s

eviction. Assuming, arguendo, that the authority was able

to document this visit with names and witnesses, this is

not a valid reason which can support the eviction.

In addition to rights of privacy, Griswold v. Connecticut,

381 U.S. 479, 515 (and cases cited therein), the housing

authority cannot exclude persons from participating in

the enjoyment of state benefits based upon factors that

bear no rational relation to the purposes of the program.

The purposes of low-income public housing have been dis

cussed. Nowhere is there an iota of Congressional indica

13

tion that otherwise eligible low-income families might be

excluded or evicted for unrelated reasons. The Housing

Authority has admitted that appellant satisfies the eligibil

ity requirements for admission and continued occupancy

(E. 29), but chooses to evict appellant for other reasons.

It has, however, failed to establish any standards which

could have apprised the appellant that her behavior might

result in eviction from the project. This absence of stan

dards renders the action arbitrary. “ . . . due process

requires that selections among applicants be made in

accordance with ‘ascertainable standards, . . .’ ” Holmes v.

New York City Housing Authority, supra; Rudder v.

United States, supra; Thorpe v. The Housing Authority

of the City of Durham, supra.

What is paramount, however, is that the appellant’s

behavior outlined by the Housing Authority does not

justify her eviction. The job of the Housing Authority

is not to set moral standards for its tenants or to regulate

visitations of its tenants, without a showing that the com

munity within the housing project is in fact disrupted

but to provide low-income housing for the needy. Ex

amined in the light of the purposes of public housing,

the attempted eviction of appellant for the reasons given

is unreasonable and arbitrary, Gulf, Colorado and Santa

Fe Ry. v. Ellis, supra, and violates appellant’s rights of

due process and equal protection.

R. A Tenant in a Public Housing P roject Is Entitled to Notice

of the Reasons fo r Eviction.

Since certain kinds of reasons for terminating peti

tioner’s lease are impermissible, including race, religion,

speech, association, illegitimacy, and purely arbitrary or

capricious reasons, it follows that petitioner must be told

the basis for the termination of her lease. It is necessary

14

for petitioner to know what reasons are allegedly relied

on in order to insure that impermissible reasons are not

involved. I f the Housing Authority is forced to disclose

a reason for termination, it might readily appear that the

Authority is relying on an illegal or, an arbitrary or

capricious reason, i.e., no reason at all. Even if the reason

asserted appears on its face to be a permissible ground

for termination, the atfected individual must know it in

order to contest the factual basis for applying that reason

to him.5

Notice of reasons would at least offer a possibility of

relief if an official is mistaken about the facts and he or

some reviewing authority can be persuaded that he is

mistaken, or if the official is mistaken about the law and

it can be shown that the proposed action violates the law,

or if the official acts contrary to policy established by

superior administrative officials. A requirement that the

housing agency state its reasons for terminating low-

income benefits serves the salutary function of requiring

that the agency act responsibly and actually have a reason.

It is a protection against capricious action.

Indeed, the policy of secrecy serves as a shield for

arbitrariness. As Mr. Justice Frankfurter put it:

Secrecy is not congenial to truth-seeking and self-

righteousness gives too slender an assurance of right

ness. No better instrument has been developed for

arriving at truth than to give a person in jeopardy

of serious loss notice of the case against him and

opportunity to meet it. Nor has a better way been

5 The tenant may even prove that the application is so lacking

in factual foundation that it is probably a subterfuge for some

illegal reason such as reprisal for exercise of a protected freedom.

Cf. Holt v. Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority, 266

F. Supp. 397 (E.D. Va. 1966).

15

found for generating the feeling, so important to a

popular government, that justice has been done. Joint

Anti-Fascist Refugee Com. v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 123,

171-2 (concurring opinion).

The right to know a reason for official action is vital

so long as there remains any conceivable method, however

informal, of influencing that action. Gonzales United

States, 348 U.S. 407, illustrates the point. In Gonzales, a

draft registrant was held entitled to have a copy of an

“ advisory recommendation” made by the Department of

Justice to his Selective Service Appeal Board, and to an

opportunity to file a reply. Though there was no hearing

before the appeal board and the statute involved was

silent on the right to know the recommendations, the

Court found that this right was implicit in the Act,

“viewed against our underlying concepts of procedural

regularity and basic fair play” 348 U.S. at 412.6

It has long been recognized that it is an integral part

of procedural due process, that notice must be given to

an individual adversely affected by administrative action

that is sufficiently specific to apprise the individual of the

nature and grounds of the action against him.7 The general

principle is well established that reasons for adverse ac

tion by government must be disclosed even if a “benefit”

or “privilege” is involved. Thus, for example, in Willner

v. Committee on Character and Fitness, 373 U.S. 96, this

6 Cf. Simmons v. United States, 348 U.S. 397, finding a depriva

tion of the fair hearing required by the selective service law in

the failure to furnish a fair resume of an adverse FBI report con

sidered by the hearing officer.

7 See Morgan v. United. States, 304 U.S. 1, 18, 19; Willner v.

Committee on Character and Fitness, 373 U.S. 96, 105-106; Dixon

v. Alabama State Bd. of Education, 294 F.2d 150, 157 (5th Cir.

1961).

1 6

Court held that an applicant for admission to the New

York State Bar had to be told the reasons for his ex

clusion.8

Notice in modern administrative law is not a formalistic

requirement. Formal pleadings setting forth reasons for

action are, of course, unnecessary. Yet the Constitution

requires that the functional purposes of notice he served—

that a person affected adversely by government “ adjudica

tory” action be made aware of the issues in the case at

some sufficiently early point in the proceedings to prepare

a case. See, 1 Davis, Administrative Law Treatise, Sec

tion 8.05; Gellhorn and Byse, Administrative Law, Cases

and Comments, 840-41 (1960).

Mrs. Richardson has only been told in “ an indirect way”

of the reasons for her eviction (R. 80). Thus, she has not

yet received notice of the reasons for her eviction suffi

ciently specific to apprise her of the charges against her.

C. A Tenant in a Public Housing Project Is Entitled to a

Fair Hearing Prior to Eviction.

Appellant has been denied a fair hearing to contest the

factual and legal adequacy of the Housing Authority’s

decision to evict her. Her only explanation of the reasons

for her eviction was a conversation with an official who

told her the reasons in an “ indirect way.” More is re

quired by the due process clause of the United States Con

stitution. Appellant must be given an opportunity to be

8 Other eases which have required procedural due process as a

prerequisite to denial or termination of “privileges” include:

Gonzales v. Freeman, 334 F.2d 570 (D.C. Cir. 1964) (debarment

from government contracts); Dixon v. Alabama State Bd. of Ed

ucation, 294 F.2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961), cert, denied 368 U.S. 930

(expulsion from state university); Hornsby v. Allen, 326 F.2d

605 (5th Cir. 1964) (denial of liquor license).

17

heard to offer proof to contest the Authority’s cancellation

of her low-income housing benefits.

The right to a hearing has long been regarded as one

of the fundamental rudiments of fair procedure necessary

where the government acts against a citizen’s vital in

terests.9 Hearings are an important protection against

arbitrariness. They are customary in our law where the

decision about how government will treat the citizen turns

on issues of fact. The expectable ordinary controversies

that may lead to public housing evictions need fair proce

dures for fact finding. They might involve various claims

of misbehavior by tenants affecting other tenants or the

property. Tenants should have the right to have decisions

on such issues based on evidence and not on rumor or

fancy. For the indigent, eviction is a serious penalty. The

Supreme Court and lower federal courts have consistently

held that no matter how certain interests are categorized,10

a hearing is necessary to determine whether they may be

terminated by the government. Thus, a hearing is neces

sary before an individual may be denied admittance to the

State Bar (Willner v. Committee on Character and Fitness,

373 U.S. 96); before a person may be denied the privilege

of practicing before the Board of Tax Appeals {Gold

smith v. United States Board of Tax Appeals, 270 TJ.S.

117); before security clearance may be revoked {Greene

v. McElroy, 360 IJ.S. 474); before a State College profes

9 See, e.g., Londoner v. Denver, 210 U.S. 373; Wong Yang Sung

v. McGrath, 339 U.S. 33; Southern R. Co. v. Virginia, 290 U.S.

190; Morgan v. United States, 304 U.S. 1.

10 The verbal distinction between “rights” and “privileges” may

not be allowed to impose unconstitutional conditions upon the re

ceipt of “benefits” or “privileges.” See, e.g., Sherbert v. Verner,

374 U.S. 398; Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513; Shelton v. Tucker,

364 U.S. 479; Wiemann v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183; Keyishian v.

Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York, 385

U.S. 589.

18

sor may be dismissed for invoking the privilege against

self-incrimination (Slochower v. Board of Higher Educa

tion, 350 U.S. 551); before individuals may be debarred

from receiving government contracts (Gonzales v. Free

man, 334 F.2d 570 (D.C. Cir. 1964)); before a student

may be expelled from a state university (Dixon v. Alabama

State Board of Education, 294 F.2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961),

cert, denied 368 U.S. 930); and before a liquor license may

be denied (Hornsby v. Allen, 326 F.2d 605 (5th Cir. 1964)).

At least one district court in Quevedo v. Collins, et al.,

C.A. 3-2626-C (N.D. Tex., July 12, 1968), has recognized

this right by recently granting a temporary restraining

order enjoining a state public housing authority from :

Seeking to evict plaintiff through summary judicial

proceedings unless the plaintiff has first been afforded

an opportunity to contest the reason for eviction at

a fair hearing, whether before the agency or a court,

which complies with the elements of due process and

equal protection of the laws.

In his concurring opinion in Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee

Com. v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 123, Mr. Justice Frankfurter

stated what he thought were the proper considerations in

determining whether there is a right to a hearing:

The precise nature of the interest that has been ad

versely affected, the manner in which this was done,

the reasons for doing it, the available alternatives to

the procedures that were followed, the protection im

plicit in the office of the functionary whose conduct is

challenged, the balance of hurt complained of and

good accomplished— these are some of the considera

tions that must enter into the judicial judgment. 341

U.S. at 163.

19

Appraising the circumstances of Mrs. Richardson’s case

against the tests mentioned by Mr. Justice Frankfurter

persuasively demonstrates her right to a hearing as a

matter of fundamental fairness:

1. “ The precise nature of the interest that has adversely

affected.” Appellant’s interest involves the difference be

tween living in a low-cost, decent, sanitary and stable

environment, and being relegated to slums that “may in

deed make living an almost insufferable burden.” Berman

v. Parker, 348 U.S. 26, 32. In Mrs. Richardson’s case,

the slum may well be a racial ghetto with the kind of

dilapidated, overcrowded housing that the National Ad

visory Commission identified as one of the most significant

grievances leading to the recent riots and disorder.11

2. “ [T]he manner in which this was done, the reason

for doing it.” The eviction notice stated no reason for

the action. The Housing Authority at first refused to give

a reason for the eviction, although appellant, in person

and through her attorney, so requested. Finally, she was

told in an indirect way, the reasons for the eviction. This

is sufficient commentary on the arbitrary manner in which

she was treated.

3. “ [T]he available alternatives to the procedure that

was followed.” The Housing Authority could have af

forded Mrs. Richardson a written statement of the grounds

for cancelling her lease, and an opportunity to present her

version of any contested issues of fact affecting her right

to remain in the housing project. Great formality of proce

dures in the conduct of a hearing would not appear to be

necessary so long as the procedures employed give Mrs.

Richardson a fair chance to know and meet the issues, to

11 Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Dis

orders, p. 472-3 (Bantam ed. 1968).

2 0

make her own position known, and to document or support

that position factually. The Authority has made no effort

to show that a hearing to resolve factual disputes deter

minative of a tenant’s right to remain in a project would

be burdensome or impractical. Surely some traditional

safeguards are needed lest tenants be deprived of their

low-income housing benefits on the basis of vicious and

unfounded rumors about their personal lives or for any of

a variety of invidious reasons.18

4. “ \T]he protection implicit in the office of the func

tionary whose conduct is challenged.” Housing authority

managers and supervisory officials ordinarily have no train

ing in or special sensitivity to problems of constitutional

law, are not directly responsive to an electorate, and are

unlikely to be morally or intellectually superior to any

other class of government administrators. They have no

special distinction which makes them the safe repositories

of arbitrary power.

5. “ [T\he balance of hurt complained of and good ac

complished.” The injury threatened to Mrs. Richardson

has been discussed above. The Housing Authority’s refusal

to give a full and complete explanation of its reasons for

evicting her deprives the Court of any opportunity to

appraise what good, if any, might be accomplished by

evicting her. Denial of a hearing may plainly hide evil,

but we are unable to perceive any useful public purpose

that it might accomplish. 12

12 For full discussion of the issues, procedural and substantive,

relating to rights of tenants in public housing, see, Rosen, Tenants’

Rights in Public Housing, in “ Housing for the Poor: Rights and

Remedies,” Project on Social Welfare Law, Supp. No. 1, N.Y.U.

School of Law, New York, N.Y. (1967). See also, Note, Public

Landlords and Private Tenants: The Eviction of “ Undesirables”

From Public Housing Projects, 77 Yale L.J. 988 (1968).

21

Thus, Mrs. Richardson’s right to her apartment should

not be taken away without giving her a fair chance to be

heard. And the hearing must be more than an empty

formality.

II.

The Housing Authority’s Asserted Compliance With

the February 7, 1967 Circular Does Not Comport

With the Guarantees of the Constitution.

Mr. A. W. Kuhn, the Executive Director of the Housing

Authority, testified that the Authority would not give a

tenant written notice of the reasons for the eviction but

would only notify the tenant in a “private discussion”

(R. 107). In addition, the tenant would be prohibited from

bringing either counsel or a lay person with her to this

conference (R. 109). Appellant submits that this refusal

to provide the tenant with a written statement of the

reasons for eviction prior to the conference with the Au

thority and the refusal to permit a tenant to be repre

sented by legal counsel or other lay person at the con

ference denies tenants of public housing the basic and

fundamental due process right to a fair hearing. It is

necessary that the individual be given a realistic oppor

tunity to confront and come to grips with the reasons

for adverse action by the government.

That the concept of a fair hearing includes, at the least,

the right to subject the rationale of agency action to

scrutiny was recognized before Willner v. Committee on

Character and Fitness, 373 U.S. 96, and even earlier in

Jordan v. American Eagle Fire Insurance Co., 169 F.2d

281 (D.C. Cir. 1948). The Court of Appeals for the Dis

trict of Columbia stated:

2 2

It is clear that the hearing afforded by the Super

intendent was not valid as a quasi-judicial hearing. . . .

Neither the bases nor the processes of the Superin

tendent’s order were explored, because they were not

revealed except in the most summary fashion. 169

F.2d at 287.

In sum, due process requires some procedure that

minimally provides certain safeguards for the adjudica

tion of the basis for the governmental action challenged.

The form and forum of the proceeding may vary. The

hearing may take place before the agency or in court.

See Jordan v. American Eagle Fire Insurance Co., supra.

But whatever the nature of the proceeding, it must at

least provide opportunity to know and to meet the evidence

and the argument on the other side before the govern

mental action becomes effective. This includes the oppor

tunity to present evidence and arguments (Londoner v.

Denver, 210 U.S. 373), to confront opposing witnesses

(Willner v. Committee on Character and Fitness, 373 U.S.

96), and effectively to present the tenant’s own version

of the facts, with the decision to be based on the facts

presented.13

The Housing Authority has not provided for a fair

hearing in keeping with constitutional guarantees. Indeed,

it has indicated that it has no intention of making such

provision.

13 Cf. Specht v. Patterson, 386 U.S. 605, where the Court said

that in a sentencing procedure

Due process . . . requires that [the person affected] . . . have

an opportunity to be heard, he confronted with witnesses

against him, have the right to cross-examine, and to offer

evidence, on his own. And there must be findings adequate

to make meaningful any appeal that is allowed. 386 U.S. at

610.

23

CONCLUSION

For all the foregoing reasons, appellant submits that

the order of the trial court denying an injunction and

declaratory judgment should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Oscar W. A dams, Jr.

Harvey B urg

1630 North Fourth Avenue

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Gabrielle A. K irk

Michael Davidson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellant

24

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that the undersigned, one of Appel

lant’s attorneys, on this date,---------------- , 1968, has served

two copies of the foregoing Brief for Appellant on J. W.

Patton, Jr., Huey, Stone & Patton, Realty Building, Bes

semer, Alabama 35020, by mailing same to said address

by United States air mail, postage prepaid.

Attorney for Appellant

APPENDIX

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F or the Second Circuit

Opinion of Court of Appeals

No. 442— September Term, 1967.

(Argued April 24, 1968 Decided July 18, 1968.)

Docket No. 31972

James H olmes, et al.,

Plaintiff s-Appellees,

—-v.—

New Y ork City H ousing A uthority,

Defendant-Appellant.

B e f o r e :

H ays, A nderson and F einberg,

Circuit Judges.

Appeal from an order of the United States District Court

for the Southern District of New York, Thomas P. Murphy,

Judge, denying the defendant’s motion to dismiss an action

brought against it under the Civil Rights Act, 42 U. S. C.

§1983. Affirmed.

H arold W e i n t r a u b , Esq., New York, N. Y.

(Harry Levy, Esq., New York, N. Y., on the

brief), for Defendant-Appellant.

la

2a

Nancy E. L bBlanc, Esq., New York, N. Y.

(Harold J. Rothwax, Esq., and Michael B.

Rosen, Esq., New York, N. Y., on the brief),

for Plaintiffs-Appellees.

O pinion o f C ou rt o f A p p ea ls

A n d e b s o n , Circuit Judge:

This class action was brought on September 9, 1966 by

31 named plaintiffs on behalf of themselves and all others

similarly situated under the Civil Rights Act, 42 U. S. C.

§1983, and the Federal Constitution, challenging the pro

cedures employed by the defendant New York City Hous

ing Authority in the admission of tenants to low-rent pub

lic housing projects administered by it in New York City.

The jurisdiction of the district court is predicated upon 28

U. S. C. §1343(3).

The New York City Housing Authority is a public cor

poration created pursuant to the Public Housing Law of

the State of New York for the purpose of implementing

the State Constitution by providing “ low-rent housing for

persons of low income as defined by law . . . ” New York

State Constitution, Art. XVIII, §1. At the time of the com

plaint in this action, the Authority was providing housing

facilities for more than 500,000 persons, in 152 public proj

ects which it owned and administered in New York City.

Approximately half of these were federal-aided projects,

the remainder being supported by either State or local

funds.

The eligibility requirements for prospective public hous

ing tenants are set out in the Public Housing Law, and in

resolutions adopted by the Authority pursuant to its rule-

making power. Public Housing Law, §37(1) (w). While

3a

these vary somewhat for federal, state, and local-aided

projects, two requirements common to all are that the

applicant’s annual income and total assets not exceed speci

fied limits, and that, at the time of admission, the applicant

have been a resident of New York City for not less than

two years. In addition each candidate must be situated

in an “ unsafe, insanitary, or overcrowded” dwelling, Reso

lution No. 62-7-473, §3 (federal-aided projects), or living

“under other substandard housing conditions.” Resolution

No. 56-8-433, §4 (state-aided projects). Each of the plain

tiffs in the present action is alleged to meet these require

ments.

Each year the Authority receive approximately 90,000

applications out of which it is able to select an average of

only 10,000 families for admission to its public housing

projects. In doing so the Authority gives preference to

certain specified classes of candidates, e.g., “ site residents,”

families in “emergency need of housing,” “ split families,”

“ doubled up and overcrowded families.” Resolution No.

56-8-433, §4.

In federal-aided projects the Authority is required to

allocate the remaining apartments among non-preference

candidates in accordance with “an objective scoring sys

tem” which is designed to facilitate comparison of the

housing conditions of these applicants. Resolution No.

62-7-473, §4(b). For state-aided projects, however, there is

no similar regulation and we assume that this is also the

case with local-aided projects.1 The plaintiffs in this action

are all non-preference candidates seeking admission to any

of the public housing projects run by the defendant.

O pinion o f C ourt o f A p p ea ls

1 Resolutions of the Authority governing admissions to local-

aided projects have not been made a part of the record on appeal.

4a

In the complaint the named plaintiffs allege that although

they have filed with the Authority a total of 51 applica

tions for admission to its housing facilities, 36 in 1965 or

earlier, and some as long ago as 1961, none has been ad

vised in writing at any time of his eligibility, or ineligibility,

for public housing.

The complaint cites numerous claimed deficiencies in the

admissions policies and practices of the Authority. Regula

tions on admissions (other than those pertaining to income

level and residence) are not made available to prospective

tenants either by publication or by posting in a conspicuous

public place. Applications received by the Authority are

not processed chronologically, or in accordance with ascer

tainable standards, or in any other reasonable and system

atic manner. All applications, whether or not considered

and acted upon by the Authority, expire automatically at

the end of two years. A renewed application is given no

credit for time passed, or precedence over a first applica

tion of the same date. There is no waiting list or other

device by which an applicant can gauge the progress of

his case and the Authority refuses to divulge a candidate’s

status on request. Many applications are never considered

by the Authority. I f and when a determination of ineligi

bility is made (on any ground other than excessive income

level), however, the candidate is not informed of the Au

thority’s decision, or of the reasons therefor.

The complaint charges that these procedural defects in

crease the likelihood of favoritism, partiality, and arbitrari

ness on the part of the Authority, and deprive the plain

tiffs of a fair opportunity to petition for admission to

public housing, and to obtain review of any action taken

by the Authority. The deficiencies are alleged to deprive

O pinion o f C ou rt o f A p p ea ls

5a

applicants of due process of law in violation of the Four

teenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution.2

In the district court the defendant moved to dismiss

the complaint for failure to state a claim within the court’s

civil rights jurisdiction. Alternatively it requested that

the court refrain from the exercise of its jurisdiction under

the doctrine of abstention.

On October 20, 1967, the motion was denied by the trial

court which also refused abstention. Thereafter permis

sion was granted to the defendant to take this interlocutory

appeal under 28 U. S. C. §1292 (b). The issues here are

whether the plaintiffs have stated a federal claim,3 and, if

so, whether the district court should proceed to the merits.

We have concluded that the district judge was correct in

answering each of these points in the affirmative and we,

therefore, affirm his order.

Clearly there is sufficient in the complaint to state a

claim for relief under §1983 and the due process clause.

One charge made against the defendant, which has merit

at least in connection with state-aided projects where the

Authority has adopted no standards for selection among

non-preference candidates, is that it thereby failed to es

tablish the fair and orderly procedure for allocating its

O pinion o f C ourt o f A p p ea ls

2 The constitutional claims in the complaint are directed at local

Resolutions or regulations (or the lack thereof) issued by the

Authority, which have effect only within the City of New York.

Public Housing Law §31. No specific provision of the Public Hous

ing Law or any other statute of general statewide application is

called into question. Accordingly, a three-judge court is not re

quired by 28 U. S. C. §2281. See e.g., Moody v. Flowers, 387 U. S.

97, 101-102 (1967).

3 While this issue was not specifically mentioned in the defen

dant’s §1292 (b) papers, we have decided to consider it in view of

its close relationship to the other question, both of which have been

fully briefed by the parties.

6a

scarce supply of housing which due process requires. It

hardly need be said that the existence of an absolute and

uncontrolled discretion in an agency of government vested

with the administration of a vast program, such as public

housing, would be an intolerable invitation to abuse. See

Eornsby v. Allen, 326 F. 2d 605, 609-610 (5 Cir. 1964).

For this reason alone due process requires that selections

among applicants be made in accordance with “ ascertainable

standards,” icl. at 612, and, in cases where many candi

dates are equally qualified under these standards, that

further selections be made in some reasonable manner

such as “by lot or on the basis of the chronological order

of application.” Hornsby v. Allen, 330 F. 2d 55, 56 (5 Cir.

1964) (on petition for rehearing). Due process is a flexible

concept which would certainly also leave room for the em

ployment of a scheme such as the “ objective scoring sys

tem” suggested in the resolution adopted by the Authority

for federal-aided projects.4 * * * * * * * 12

There is no merit in the Authority’s contention that the

plaintiffs are without standing to raise the due process

objection. As applicants for public housing, all are im

mediately affected by the alleged irregularities in the prac

tices of the Authority. Compare Thomas v. Housing Au

thority of City of Little Rock, 282 F. Supp. 575 (E. D.

Ark. 1967); Banks v. Housing Authority of City of San

Francisco, 120 Cal. App. 2d 1, 260 P. 2d 668 (Dist. Ct. App.

4 The possibility of arbitrary action is not excluded here, how

ever, by the. existence of this reasonable regulation. The “ scoring

system” scheme will hardly assure the fairness it was devised to

promote if, as the plaintiffs allege, some applicants, but not others,

are secretly rejected by the Authority, are not thereafter informed

of their ineligibility, and are thereby deprived of the opportunity

to seek review of the Authority’s decision, as provided by New

York law under CPLR §7803(3). Cf. Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U. S

12 (1955).

O pin ion o f C ou rt o f A p p ea ls

7 a

1953), cert, denied, 347 U. S. 974 (1954); cf., Norwalk

Core v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency, Slip Opinion p.

2599 (2 Cir. June 7, 1968).

The mere fact that some of the allegations in the com

plaint are lacking in detail is not a proper ground for

dismissal of the action. Harman v. Valley National Bank

of Arizona, 339 F. 2d 564, 567 (9 Cir. 1964); 2A Moore’s

Federal Practice 1)12.08, at 2245-2246 (2d ed. 1968). A

case brought under the Civil Rights Act should not be

dismissed at the pleadings stage unless it appears “ to a

certainty that the plaintiff would be entitled to no relief

under any state of facts which could be proved in support

of his claim.” Barnes v. Merritt, 376 F. 2d 8, 11 (5 Cir.

1967). This strict standard is consistent with the general

rule. See 2A Moore’s, supra at 2245. Clearly it has not

been met here.

The principal argument which the Authority has pressed

on this appeal is that the district court should have re

fused to exercise its jurisdiction under the judicially-

created “ abstention” doctrine, which recognizes circum

stances under which a federal court may decline to proceed

with an action although it has jurisdiction over the case

under the Constitution and the statutes. See generally

Wright on Federal Courts §52, at 169-177 (1963). We

agree with the district judge that this is not an appro

priate case for abstention.

At least in actions under the Civil Rights Act the power

of a federal court to abstain from hearing and deciding

the merits of claims properly brought before it is a closely

restricted one which may be invoked only in a narrowly

limited set of “ special circumstances.” Zwickler v. Koota,

389 U. S. 241, 248 (1967); cf. Allegheny County v. Mashuda

Co., 360 U. S. 185, 188-189 (1959). In enacting the pred

ecessor to §1983 Congress early established the federal

O pinion o f C ou rt o f A p p ea ls

8a

courts as the primary forum for the vindication of fed

eral rights, and imposed a duty upon them to give “due

respect” to a suitor’s choice of that forum. Zwickler v.

Koota, supra at 247-248; Harrison v. N. A. A. C. P., 360

U. S. 167, 180-181 (1959) (dissenting opinion). As a con

sequence it is now widely recognized that “cases involving

vital questions of civil rights are the least likely candi

dates for abstention.” Wright v. McMann, 387 F. 2d 519,

525 (2 Cir. 1967). See also McNeese v. Board of Educa

tion, 373 U. S. 668, 672-674 (1963); Stapleton v. Mitchell,

60 F. Supp. 51, 55 (D. Kan.), appeal dismissed per stipu

lation, 326 IT. S. 690 (1945); Note, Federal-Question Ab

stention: Justice Frankfurter’s Doctrine in an Activist

Era, 80 Harv. L. Rev. 604, 607-611 (1967); Note, Judicial

Abstention from the Exercise of Federal Jurisdiction, 59

Col. L. Rev. 749, 768-769 (1959). Where a district judge

chooses to exercise his equitable discretion in favor of re

taining such an action it will be unusual indeed when an

appellate court refuses to uphold his decision. Cf., Har

rison v. N. A. A. C. P., supra; Note, Federal Judicial Re

view of State Welfare Practices, 67 Col. L. Rev. 84, 98-100

(1967).

Nevertheless the Authority vigorously contends that the

district court should have deferred to the courts of the

State of New York, where an adequate remedy is said to

be provided under state law, in order to avoid “ possible

disruption of complex state administrative processes,”

Zwickler v. Koota, supra at 249 n. 11, which it envisions

as the inevitable result of an attempt by the federal court

to resolve the issues presented in the complaint.

We fail to see how federal intervention in the present

case will result in any substantial way in the disruption

of a complex regulatory scheme of the State of New York,

O pin ion o f C ou rt o f A p p ea ls

9a

or in interference from the outside with problems of

uniquely local concern. The Authority clearly does direct

and control a complex administrative process, much of

which is concerned with the establishment of standards and

policies for the admission of tenants, a function which

Congress has recognized that localities are “ in a much bet

ter position than the Federal Government” to perform. S.

Rep. No. 281, 87th Cong., 1st Sess. (1961) in 2 U. S. Code

Cong. & Ad. News, pp. 1943-1944. But the complaint in

this action wages only a very limited attack on that proc

ess, and in no sense does it seek to interpose the federal

judiciary as the arbiter of purely local matters. Rather the

plaintiffs assert a narrow group of constitutional rights

based upon overriding federal policies, and ask federal in

volvement only to the limited extent necessary to assure

that state administrative procedures comply with federal

standards of due process. This fundamental concept

hardly can be said to be “ entangled in a skein of state law

that must be untangled before the federal case can pro

ceed,” McNeese v. Board of Education, supra at 674. Nor

do we see here any “ danger that a federal decision would

work a disruption of an entire legislative scheme of regu

lation.” Hostetter v. Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor Corp.,

377 U. S. 324, 329 (1964). In fact the issue in the present

case arises out of a total lack of any system for the orderly

processing of applications and notification to applicants

outside of the few categories mentioned.

The ground for federal abstention upon which the Au

thority relies derives from the Supreme Court’s decisions

in Burford v. Sun Oil Co., 319 U. S. 315 (1943), and Ala

bama Public Service Commission v. Southern Railway Co.,

341 IT. S. 341 (1951), discussed in Note, 59 Col. L. Rev.,

O pinion o f C ou rt o f A p p ea ls

10a

supra at 757-762.5 But in those cases the federal courts

were asked to resolve problems calling for the comprehen

sion and analysis of basic matters of state policy, see 319

U. S. at 332; 341 U. S. at 347, which were complicated

by non-legal considerations of a predominantly local na

ture, and which made abstention particularly appropriate.

In contrast to the present case which presents only issues

of federal constitutional law, Burford and Alabama in

volved situations to which concededly the “ federal courts

can make small contribution.” 319 U. S. at 327. Equally

important as a distinguishing factor is the fact that the

state legislatures in those cases had specially concentrated

all judicial review of administrative orders in one state

court, see 319 U. S. at 325-327; 341 U. S. at 348; Note, 59

Col. L. Rev., supra at 759-760, in effect designating the

state courts and agencies as “working partners” in the

local regulatory scheme. 319 U. S. at 326. While this might

be said to hold true in future cases in New York where

the Authority makes a specific determination of ineligi

bility affecting a particular applicant for public housing,* 6

O pinion o f C ou rt o f A p p ea ls

6 Burford involved an attack in the district court on a proration

order issued by the Texas Railroad Commission as part of a com

plex state regulatory program devised for the conservation of oil

and gas in Texas. Alabama was an action in the federal court

challenging an order of a state regulatory commission in which a

railroad was refused permission to discontinue certain of its intra

state train service. In each case the Supreme Court ordered the

federal suit dismissed on the ground that it involved issues of a

peculiar local interest regarding which the particular state con

cerned had established a specialized regulatory system for both

decision and review.

6 Judicial review in the- New York courts is available to any re

jected public housing applicant under CPLR §7803(3), where he

may question “ whether a determination was made in violation of.

lawful procedure, was affected by an error of law or was arbitrary

and capricious or an abuse of discretion . . . .” Once an adminis-

11a

it is certainly not so here where the very concern of the

plaintiffs is that no such determinations have been made,

and where New York law provides a remedy for the plain

tiffs’ ills which is dnbions at the very best.7 What we have

just said also serves to distinguish the recent case of

Randell v. Newark Housing Authority, 384 F. 2d 151 (3

Cir. 1967), cited by both parties, where the federal court * S.

O pinion o f C ou rt o f A p p ea ls

trative procedure has been instituted by the Authority which in

all respects complies with Federal constitutional standards, then

the great majority of claims arising out of the acceptance or re

jection of applicants by the Authority will be matters entirely

within the purview of the State courts, which sit in a “much better

position . . . to ascertain the myriad factors that may be involved

in a particular situation and to determine their proper weight.”

S. Rep. No. 281, 87th Cong., 1st Sess. (1961) in 2 U. S. Code

Cong. & Ad. News, at 1944; cf., Austin v. NYCHA, 40 Misc. 2d

206, 267 N. Y. S. 2d 300 (1965); Sanders v. Cruise, 10 Misc. 2d

533, 173 N. Y. S. 2d 871 (1965).

7 The only possibility for relief in the state courts in the present

case where no determination as to the eligibility of any of the

plaintiffs has been made, is by way of mandamus under §7803(1),

brought to compel the Chairman or Executive Director of the

Authority “ to perform a duty enjoined upon [him] by law,” i.e.,

to issue regulations to remedy the procedural defects alleged in

the complaint, as he is empowered to do under Resolutions ap

plicable to both federal and state-aided projects. See Res. No.

56-8-433, §9(i ) , (iii), and (iv) ; Res. No. 62-7-473, §10(i), (ii),

and (iv). We do not think, however, that this section would pro

vide the plaintiffs a “plain, adequate and complete” remedy in the

state courts, Potwora v. Dillon, 386 F. 2d 74, 77 (2 Cir. 1967), a

necessary precondition to abstention. Compare Wright v. McMann,

387 F. 2d 519, 523-524 (2 Cir. 1967). The restrictive New York

case law supports this conclusion. See, e.g., Gimprich v. Board of

Ed. of City of New York, 306 N. Y. 401, 118 N. E. 2d 578 (1954)

(mandamus does not lie to compel an act of administrative discre

tion) ; Grand Jury Ass’n of New York County, Inc. v. Schweitzer,

11 A. D. 2d 761, 202 N. Y. S. 2d 375 (1960) (petitioner must show

“clear legal right” to mandamus) ; C. S. D. No. 2 of Towns of

Cosy mans, et al. v. New York State Teachers Retirement System,

46 Misc. 2d 225, 250 N. Y. S. 2d 535 (1965) (even then, relief

may be denied in court’s discretion).

12a

action was “ closely tied” to various landlord and tenant

actions already pending before the courts of New Jersey.

384 F. 2d at 157, n. 15.

Equitable considerations also favor the result reached

by the district judge. The 31 named plaintiffs speak not

only for themselves, but also for thousands of New York’s

neediest who may have been unfairly entrenched in squalor

due to the alleged inadequacies of the Authority’s proce

dures. The need for relief is thus immediate, and should

not be aggravated further by delay in the courts. See

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360, 378-379 (1964); Allegheny

County v. Mashuda Co., supra at 196-197; England v.

Louisiana State Bd. of Medical Examiners, 375 U. S. 411,

425-427 (1964) (Justice Douglas concurring); Note, 80

Harv. L. Rev., supra at 606-607.

The order of the district court is affirmed.

O pinion o f C ou rt o f A p p ea ls

H ays, Circuit Judge (dissenting) :

I dissent.

The plaintiffs allege that applicants for public housing

are not notified as to whether they are eligible, that they

must refile their applications every two years and do not

get priority because of earlier filing, and that the Housing

Authority has not published and posted its regulations

regarding selection of tenants. These complaints hardly

seem to raise federal constitutional questions. See Chaney

v. State Bar, 386 F. 2d 962 (9th Cir. 1967), cert, denied,

36 H. S. L. W. 3390 (April 8, 1968); Powell v. Workmen’s

Comp. Board, 327 F. 2d 131 (2d Cir. 1964); Sarelas v.

Sheehan, 326 F. 2d 490 (7th Cir. 1963), cert, denied, 377

H. S. 932 (1964).

13a

But even if we assume that some constitutional issues

are raised, there are no allegations which tend to show

that the individual plaintiffs have been denied rights. We

should not entertain such a vague, uncertain, abstract and

hypothetical complaint. See Birnbaum v. Trussell, 347

F. 2d 86 (2d Cir. 1965).

O pinion o f C ou rt o f A p p ea ls

14a

Order of Temporary Injunction

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F oe the Northern D istbict of T exas

Dallas D ivision

Civil A ction No. CA 3-2626-C

Mbs. Dominga Q u e v e d o , and on behalf o f all others

similarly situated,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

Me. W illiam W. Collins, Jr,, Individually and as Regional

Administrator of the Department of H ousing and U r

ban Development, Mb. J. W. Simmons, Jb,, Individually

and in his capacity as Chairman of the Board of Di

rectors of the H ousing A uthority of the City of Dal

las, Mb. James L. Stephenson, Individually and in his

capacity as Executive Director of the H ousing A uthor

ity of the City of Dallas and in his capacity as Secre

tary to the Board of Directors of the H ousing A uthor

ity of the City of Dallas, and Me. K eith B eard,

Individually and as Manager of Elmer Scott Housing

Project, 1600 Morris Street, Dallas, Texas,

Defendants.

On the 19th day of June, 1968, came on to be heard the

above styled and numbered cause, and came the plaintiff

in person and by attorney and announced ready for trial,

and the defendants having been duly served appeared in

person and by attorney and announced ready for trial;

15a

Order of Temporary Injunction

And it appearing to the Court from an inspection of the

pleadings herein and from the argument of counsel for

plaintiff and of counsel for defendants that the Court has

jurisdiction over all parties hereto except defendant Wil

liam C. Collins and of the issues raised by the pleadings,

and no jury having been demanded by either of the parties

hereto, the Court proceeded to try said cause; and there

upon all matters in controversy as well of facts as of law,

were submitted to the Court, and the Court having heard

the pleadings and the evidence and argument of counsel,

is of the opinion that the material facts alleged in the

Plaintiff’s Petition have been proven by full and satis

factory evidence, and that plaintiff is entitled to a tem

porary injunction against the defendants,

I t i s , t h e r e f o r e , o r d e r e d , a d j u d g e d a h d d e g r e e d by the

Court that the named defendants, their agents, employees,

successors, and all persons in active concert with them be

temporarily enjoined from: