United States v. Price Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

September 30, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Price Brief for Appellant, 1965. 336774c4-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b1441d76-0b2d-4bae-84d1-d714acbb20a7/united-states-v-price-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

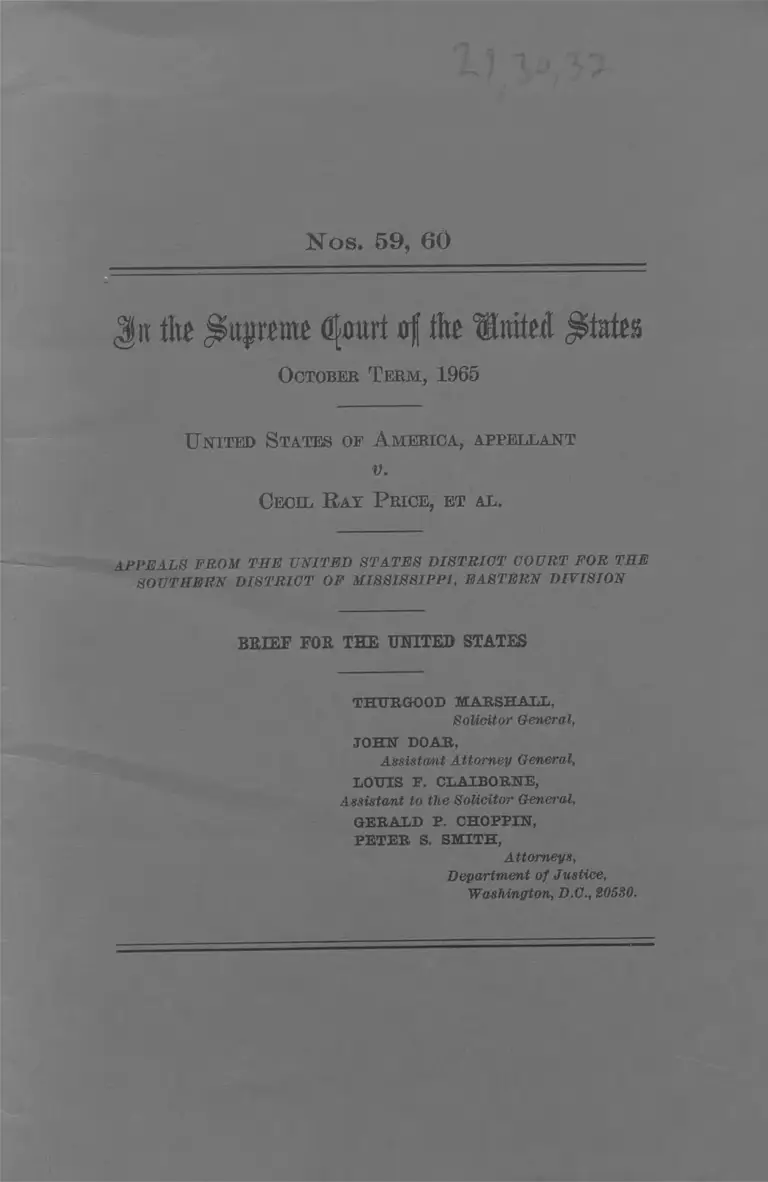

Nos. 59, 60

Jit M j&tjime dfourt of to United states

O ctober T e r m , 1965

U n it e d S ta t e s of A m e r ic a , a p p e l l a n t

v.

C e c il R a y P r ic e , e t a l .

APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI, EASTERN DIVISION

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

THURGOOD M ARSH ALL,

Solicitor General,

JOHN DOAR,

Assistant Attorney General,

LOTUS F. CLAIBORNE,

Assistant to the Solicitor General,

GERALD P. CHOPPIN,

P E T E R S. SM ITH ,

Attorneys,

Department of Justice,

Washington, D.C., S05S0.

I N D E X

Page

Opinions Below______________________________________________ 1

Jurisdiction__________________________________________________ 1

Questions presented_________________ 2

Statutes involved____________________________________________ 2

Statement____________________ :______________________________ 3

Argument:

Introduction and Summary____________________________ 7

I. Section 241 of the Criminal Code protects rights

secured by the Due Process Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment____ __________________ :_________ 12

A. The text and context of Section 241_________ 15

B. The legislative history of Section 241_____ 25

II. Section 242 of the Criminal Code reaches private

individuals who act in association with state

officers to carry out a scheme to invade rights

secured by the provision_________________________ 28

Conclusion___________________________________________________ 36

Appendix____________________________________________________ 37

Cases:

Baldwin v. Franks, 120 U.S. 678______________________ 20

Baldwin v. Morgan, 251 F. 2d 780____________________ 31, 35

Barron v. United States, 5 F. 2d 799___________________ 34

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715_ 30

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 1__________________________ 25

DiPreia v. United States, 270 Fed. 73--------------------------- 33

Downie v. Powers, 193 F. 2d 760______________________ 32

Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94____________________________ 22

Gebardi v. United States, 287 U.S. 112-------------------------- 10

Griffin v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 130______________________ 30

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347---------------------- 14, 17, 21

Haggerty v. United States, 5 F. 2d 224_________________ 34

Hampton v. City oj Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320_______ 31

Hodges v. United States, 203 U.S. 1____________________ 14

James v. Bowman, 190 U.S. 127----------------------------------- 28

Jin Fuey M oy v. United States, 254 U.S. 189-------------- 9

(T.)

786- 542— 65------------1

II

Cases— Continued Page

Koehler v. United States, 189 F. 2d 711---------------- -------34, 35

Logan v. United States, 144 U.S. 263------------------- 8, 16, 21, 22

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267----------------------------- 30

M ay v. United States, 175 F. 2d 994----------------------------- 34

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 668-------------- 31

Melling v. United States, 25 F. 2d 92--------------------------- 33

Minor v. ILappersett, 21 Wall. 162-------------------------------- 21

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167--------------------------------------- 31

Motes v. United States, 178 U.S. 458---------------------------- 17, 22

Nye db Nissen v. United States, 168 F. 2d 846, affirmed,

336 U.S. 613_________________________________________ 9

Pennsylvania v. Board of Trusts, 353 U.S. 230------------ 30

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244------------------ 30

Pope v. Williams, 193 U.S. 621------------------------------------ 21

In re Quarles, 158 U.S. 532_______ _____________________ 16, 22

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533------------------------------------- 31

Ex parte Riggins, 134 Fed. 404-------------------------------------- 13

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U.S. 153--------------------------------- 30

Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91---------- 7, 8, 14, 18, 19, 29

Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323 F.

2d 959________________________________________________ 31

Slaughter-House Cases, 16 Wall. 36------------------------------ 27

Smith v. Holiday Inns of America, 336 F. 2d 630_____ 31

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303----------------------- 25

Swanne Soon Young Pang v. United States, 209 F. 2d

245___________________________________________________ 33

Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 U.S. 350___________ 31

United States v. Bayer, 4 Dill. 407, 24 Fed. Cas. 1046.. 34

United States v. Borden Co., 308 U.S. 188_____________ 9

United States v. Braverman, 373 U.S. 405_____________ 2

United States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299__________ 14, 17, 19, 21

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542______________ 14

United States v. Decker, 51 F. Supp. 20_______________ 33

United States v. Guest, No. 65, this term__________ 16, 22, 28

United States v. Hall, 26 Fed. Cas. 79_________________ 13

United States v. Holte, 236 U.S. 140___________________ 10

United States v. Hvass, 355 U.S. 570___________________ 2, 9

United States v. Knickerbocker Fur Coat Co., 66 F. 2d

388___________________________________________________ 33

United States v. Lynch, 94 F. Supp. 1011, affirmed,

189 F. 2d 476, certiorari denied, 342 U.S. 831____ 32, 35

Ill

Cases— Continued Page

United. States v. Mall, 26 Fed. Cas. 1147______________ 13

United States v. Melekh, 193 F. Supp. 586____________ 34

United Slates v. Mosley, 238 U.S. 383_____ 14, 15, 17, 21, 28

United States v. Palermo, 172 F. Supp. 183__________ 33

United States v. Rabinowich, 238 U.S. 78______________ 10

United States v. Russo, 284 F. 2d 539________ 33

United States v. Saylor, 322 U.S. 385__________________ 17, 21

United States v. Selph, 82 F. Supp. 56_________________ 33

United States v. Snyder, 14 Fed. 554__________________ 33, 34

United States v. Trierweiler, 52 F. Supp. 4____________ 10

United States v. Waddell, 112 U.S. 76_____________ 16, 21, 22

United States v. J. R. Watlcins Co., 127 F. Supp. 97. _ 33

United States v. Wheeler, 254 U.S. 281_________________ 14

United States v. Williams, 341 U.S. 70________________ 12,

13, 14, 15, 18, 22, 23

United States v. Wise, 370 U.S. 405___________________ 2

United States v. Woodson, 371 U.S. 12_________________ 2

Valle v. Stengel, 176 Fed. 2d 697______________________ 31

Vane v. United States, 254 Fed. 32____________________ 33

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339_________________ *_____ 25

Williams v. United States, 341 U.S. 97______________ 7, 8, 29

Williams v. United States, 179 F. 2d 644, affirmed, 341

U.S. 70_______________________________________________ 5, 21

Williams v. United States, 179 F. 2d 656, affirmed, 341

U.S. 97_________ ______________________________________ 32

Wilson v. United States, 230 F. 2d 521________________ 34

Ex parte Yarbrough, 110 U.S. 651_____________________ 16, 21

Constitution and statutes:

United States Constitution:

Thirteenth Amendment___________________________ 24

Fourteenth Amendment______________ 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 13,

14, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 30, 31

Fifteenth Amendment________________________ 14, 27, 28

Rev. Stat. 2289___________________________ __________________ 21

Revised Statutes, § 5508______________________________ 23

Criminal Code of 1909, § 20, 35 Stat. 1092___________ 16

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27___________ 18, 20, 22, 24, 27

Enforcement Act of 1870, 16 Stat. 140 et seq.:

Section 2_________ 15

Section 3 ________________________________________________ 15

Sections 1 -4_____________________________________________ 20

IV

Enforcement Act of 1870— Continued Page

Section 6________ ___________________________ 13 ,1 5 ,2 0 ,2 3 ,26

Section 7______ 20

Section 16_________ _______________________________ ; ____18, 20

Section 17_________________________ _____________ 16, 18, 20, 25

14 Stat. 74___________________________________________________ 23

16 Stat. 96_____ * ___________________________________________ 23

United States Code:

18 U.S.C. 2_____________________________________________ 3, 9

18U.S.C. 2(a)_______________________________ 33

18 U.S.C. 201__________ 34

18 U.S.C. 241 — , _____________________________ 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9,

10, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26

18 U.S.C. 242_______________ 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 14, 16, 17,

18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 35

18 U.S.C. 371_________________________________ 5

18 U.S.C. 3731_______ 2

28 U.S.C. 1343(3)______________________________________ 31

42 U.S.C. 1983_________________________________________ 31

Miscellaneous:

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 2d Sess., pp.:

2942________________________________________________ 20

3479 _____________________________________________ 20

3480 __ ____________________ 1_____________________ 20

3611 _____ j ____________________ _____________ _ 26, 27, 28

3612 _______________________________________________ 20,28

3613 ______________________ __________________ 26,27 ,28

3679________________________________________________ 20

3688________________________________________________ 20

3690________________________________________________ 20

Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, Rule 7(d)______ 8

Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, Rule 20_______ 4

James, The Framing of the Fourteenth Amendment

(1956), p. 1 4 3 ._______________________________________

S. Rep. No. 102, 82d Cong., 1st Sess., p. 7___________

22

34

Jn Hit §$n$m\xt d{imrt of Hit Hinted

O ctober T e r m , 1965

Nos. 59, 60

U n it e d S tates of A m e r ic a , a p p e l l a n t

v.

C e c il R a y P r ic e , e t a l ,

APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI, EASTERN DIVISION

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinions o f the district court (R. 4-7, 18-25)

are not yet reported.

j u r i s d i c t i o n

The judgments of the district court dismissing one

indictment in its entirety as to all appellees (R. 8)

and three counts of a second indictment as to fourteen

of the appellees (R. 26-28) were entered on March 2,

1965. Notices of appeal to this Court were tiled on

the same day (R. 9-10, 28-29). On April 26,1965, the

Court entered an order postponing further considera

tion of the question of jurisdiction and consolidating

these appeals (R. 30). The jurisdiction o f this Court

to review the decision o f the district court on direct

a)

2

appeal is conferred by 18 U.S.C. 3731. United States

v. Braverman, 373 U.S. 405; United States v. Hvass,

355 U.S. 570.1

QUESTIONS PBESENTED

1. Whether the right, secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment, not to be deprived o f life or liberty with

out due process of law by persons acting under color

of State law is a “ right or privilege secured * * * by the

Constitution” within the meaning of Section 241 o f

the Criminal Code.

2. Whether private individuals who act in associa

tion with public officials to carry out a scheme to de

prive persons o f rights protected by the Fourteenth

Amendment are within the reach of Section 242 o f the

Criminal Code.

STATUTES IN VOLVED

18 U.S.C. 241 provides:

I f two or more persons conspire to injure,

oppress, threaten, or intimidate any citizen in

the free exercise or enjoyment of any right

or privilege secured to him by the Constitution

or laws of the United States, or because of his

having so exercised the same; or

I f two or more persons go in disguise on the

highway, or on the premises of another, with

intent to prevent or hinder his free exercise

1 The j urisdiction of this Court to entertain the direct appeal

in No. 60 is not affected by the fact that Counts 2, 3 and 1

were dismissed only as to some of the defendants. See, e.g.,

United States v. Wise, 370 U .S. 405; United States v. Wood-

son, 371 U .S. 12. The objections to jurisdiction interposed in

response to the government’s jurisdictional statement— all with

out substance— are discussed in note 4, mfra, pp. 8-9.

3

or enjoyment of any right or privilege so se

cured—

They shall be fined not more than $5,000 or

imprisoned not more than ten years, or both.

18 U.S.C. 242 provides:

Whoever, under color of any law, statute,

ordinance, regulation, or custom, willfully sub

jects any inhabitant of any State, Territory,

or District to the deprivation o f any rights,

privileges, or immunities secured or protected

by the Constitution or laws of the United

States, or to different punishments, pains, or

penalties, on account of such inhabitant being

an alien, or by reason of his color, or race, than

are prescribed for the punishment o f citizens,

shall be fined not more than $1,000 or im

prisoned not more than one year, or both.

18 U.S.C. 2 provides:

(a) Whoever commits an offense against the

United States or aids, abets, counsels, com

mands, induces or procures its commission, is

punishable as a principal.

(b) Whoever willfully causes an act to be

done which if directly performed by him or

another would be an offense against the United

States, is punishable as a principal.

STATEM EN T

On January 15, 1965, the United States grand jury

for the Southern District of Mississippi returned two

indictments (R. 1-2, 11-16), each charging the same

4

eighteen persons 2 with offenses against the civil rights

of Michael Henry Schwerner, James Earl Chaney and

Andrew Goodman, who were killed during the sum -'

mer of 1964 in the vicinity of Philadelphia, Missis

sippi. Three of the defendants (Rainey, Price and

W illis) were alleged to be State law enforcement o f

ficers then “ acting by virtue of [their] official positions

and under color of the laws of the State of Missis

sippi” . There is no claim that the remaining defend

ants held public office.

1. The indictment in No. 59 (R. 1-2) involves a

single count charging all the defendants with a crim

inal conspiracy in violation of 18 U.S.C. 241. It

alleges that, between stated dates in 1964, the eighteen

named persons (R. 2 )—

* * * conspired together, with each other and

with other persons to the Grand Jury unknown,

to injure, oppress, threaten and intimidate

Michael Henry Schwerner, James Earl Chaney

and Andrew Goodman, each a citizen of the

United States, in the free exercise and enjoy

ment of the right and privilege secured to them

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States not to be deprived

of life or liberty without due process o f law by

persons acting under color of the laws of

Mississippi.

2 James E. Jordan, one of the defendants charged in the two

indictments, was not before the district court and is not affected

by the rulings below or the present appeals. His case was

transferred to the United States District Court for the Middle

District of Georgia under Rule 20, F.R. Cr. P.

The indictment further alleges the means by which

the defendants planned to achieve the objects of their

conspiracy.

The district court dismissed the indictment in its

entirety, as to all defendants, on the ground that it

did not state an offense against the United States

(R. 8). Invoking an alternative ground of the ruling

in Williams v. United States, 179 F. 2d 644 (C.A. 5),

affirmed, in paid on other grounds, 341 U.S. 70, the

court held that Section 241 of the Criminal Code

vindicates only “ federally created rights” , and does

not embrace the Fourteenth Amendment right set

forth in the indictment (R. 4-7).

2. The indictment in No. 60 (R. 11-16) is in four

counts, each of which names all eighteen defendants.

Count 1—which was sustained as to all defendants and

is not in issue here— charges a violation of 18 U.S.C.

371 by conspiring to commit offenses defined in 18

U.S.C. 242. The present appeal is directed to the

partial dismissal of Counts 2, 3 and 4, which charge

substantive violations of Section 242.

The three substantive counts are identical, except

that each involves a different victim. Thus, Count 2

(R. 13-14) charges that the several defendants—

* * * while acting under color of the laws

of the State of Mississippi, did wilfully assault,

shoot and kill Michael Henry Schwerner, an

inhabitant of the State of Mississippi, then and

there in the custody o f Cecil Ray Price, for

the purpose and with the intent of punishing

Michael Henry Schwerner summarily and with

out due process of law and for the purpose and

786-542— 65------- 2

6

with the intent of punishing Michael Henry

Schwerner for conduct not so punishable under

the laws of Mississippi, and did thereby wil

fully deprive Michael Henry Schwerner of

rights, privileges, and immunities secured and

protected by the Constitution and the laws of

the United States, namely, the right not to be

deprived of his life and liberty without due

process of law, the right and privilege to be

secure in his person while in the custody of

the State o f Mississippi and its agents and

officers, the right and privilege to be immune

from summary punishment without due process

of law, and the right to be tried by due process

of law for an alleged offense and, if found

guilty, to be punished in accordance with the

laws of the State of Mississippi.

The district court granted motions to dismiss Counts

2, 3 and 4 as to all the private defendants (while

denying similar motions with respect to the three

defendants who are law enforcement officers) (R.

26-28). The court read Section 242 as reaching only

the acts o f public officers while acting officially. In

the court’s view, no offense was stated against the

private defendants because it was “not charged as

an ultimate fact that [any of them] did anything

as an official” or that the “ individual defendants

were officers in fact, or defacto in anything allegedly

done by them hinder color of law’ ” (R. 19-20).

7

ARGU M EN T

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY

These cases rest on a charge that the eighteen de

fendants—three of them State officials acting under

color of their offices—jointly conceived and executed

a plan against three citizens of the United States

and inhabitants of Mississippi, then in State custody,

that they be released, intercepted, assaulted and

murdered. It is alleged that these acts violated

rights guaranteed to the victims by the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the de

fendants were accordingly indicted for entering into

a conspiracy punishable under Section 241 of the

Criminal Code (No. 59), and, in a second indictment

(No. 60), for conspiring to violate Section 242 (Count

1) and for committing the substantive crime there

defined as to each victim (Counts 2, 3 and 4).

On this appeal, there can be no question that a

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment—at least by

the three official defendants—has been adequately

charged. Nor is it debatable that the Due Process

rights described in the indictments have been suffi

ciently “made definite by decision or other rule o f

law” to support a criminal prosecution against those

charged with “ willfully” invading them. See Screws

v. United States, 325 U.S. 91, 103; 'Williams v. United

States, 341 U.S. 97, 101-102. So much is unchal

8

lenged.3 Indeed, those matters are foreclosed by the

decision below sustaining the conspiracy count of

the indictment under Section 242 and, with respect

to the three State officers, the substantive charges of

violating the same statute. Finally, there is no ques

tion as to the technical sufficiency of either indict

ment. The rulings below point out no pleading defect

o f that kind; they were squarely based on a construc

tion of the statutes involved4 and, in the circum-

3 The indictment alleges more than ordinary murder for

personal reasons by a group of individuals, some of whom

happened to be holding State office. Not only is it alleged

that the State law enforcement officers were acting under color

of their office (It. 1, 11), but the charge is that they used

their official powers to release State prisoners and turn them

over to a lynch mob, which one of the officers shielded by his

presence, with a vieAV that they be summarily punished with

out benefit of trial (see It. 2, 12, 14, 14-15, 15-16). Thus,

the case is plainly within the rule announced in Screws and

the third Williams decision. That the death of the victims

was the ultimate consummation of the conspiracy does not

put in doubt the applicability of Section 242 is settled by

Screws. The same question with respect to Section 241 (as

suming it protects Fourteenth Amendment rights) is settled

by Logan v. United States, 144 U.S. 268.

4 There is accordingly no doubt about the jurisdiction of this

Court to entertain the government’s appeal. To be sure, the

court below noted that the indictment in No. 59 alleged that

the three State officers charged were “each acting at all times

under ‘color of laws’ ” , whereas “ [t]lie statute mentions nothing

about ‘color of law’ in the description lof the crime embraced” (R.

4). But the suggestion that the court was pointing to a plead

ing defect and dismissed the indictment partly on that ground

is frivolous. A t worst, the allegation is surplusage which

would support a motion to strike. F.R. Cr. P., Rule 7 (d ).

In any event, it is plain the court at as quarreling, not Avith

9

stances, no other issue is open on this direct appeal.

See United States v. Borden Co., 308 U.S. 188, 193;

United States v. Hvass, 355 U.S. 570, 574. Only two

questions remain:

1. The first is whether Section 241 reaches the in

vasion of rights guaranteed by the Due Process

Clause o f the Fourteenth Amendment, I f so, dis

missal o f the indictment in No. 59 must be reversed.

No interpretation of the Constitution is required to

sustain that charge. Three of the accused are State

officials, alleged to have acted under color of their

offices. They, of course, have the capacity directly

to violate the Fourteenth Amendment. The others

the wording of the indictment, but its theory— that Section

241 reaches Fourteenth Amendment rights.

Nor does the trial court’s comment that the substantive

counts of the indictment in No. 60 do not charge that the

private defendants were “officers in fact, or de facto in any

thing allegedly done by them ‘under color of law’ ” (R. 20)

amount to a holding that the indictment was technically de

ficient in this respect. W e are not questioning the court’s

reading of the indictment; our appeal is from the ruling that

persons without official status are never amenable to Section

242, no matter how involved they may be in the crime of

State officers. The answer to that question depends upon a

construction of the substantive statute (read in the light of

the Fourteenth Amendment) or of the aider or abettor statute

(18 U.S.C. 2).

Finally, there is no merit to the suggestion that the direct

appeal in No. 60 is defeated by the failure to plead the “aider

and abettor” statute, 18 U.S.C. 2, which is now relied upon

to sustain the substantive charges against the private defend

ants. It is well settled that an aider and abettor, made a prin

cipal by 18 U.S.C. 2, may be indicted as a principal. Jin

Fuey M oy v. United States, 254 U.S. 189; Nye <& Nissen v.

United States, 168 F. 2d 846 (O.A. 9), affirmed, 336 U.S. 613.

10

are charged as co-conspirators who joined in a scheme

to deprive the victims of their right “ not to be sum

marily punished without due process of law by per

sons acting under color of the laws of the State of

Mississippi” (R. 12). In No. 59, it does not matter

whether or not they are themselves viewed as having

acted “ under color of law,” for the only charge here

is one of conspiracy and it is settled that a “ person

may be guilty of conspiring although incapable of

committing the objective offense.” United States v.

Rabinowich, 238 U.S. 78, 86; Gebardi v. United States,

287 U.S. 112, 121; United States v. Holte, 236 U.S.

140, 145. See, also, United States v. Trierweiler, 52

F. Supp. 4 (E.D. 111.). Indeed, the court below so

ruled with respect to the conspiracy count under Sec

tion 242 in No. 60, and the same principle obviously

applies to Section 241 if it also reaches invasion of

Fourteenth Amendment rights.

To repeat, the only question in No. 59 is one of

statutory construction: Whether rights guaranteed by

the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

(and made specific by decisions o f this Court) are

“ right[s] or privilege [s] secured * * * by the Con

stitution” within the meaning of Section 241.. We

answer that question in the affirmative on the basis

o f the language of the statute, its context, and its legis

lative history. Because the text itself, in its historical

setting, so naturally lends itself to that reading, the

principal burden of our argument on this point is a

rebuttal of the several considerations recently sum

moned against such a construction.

11

2. The other issue arises only in No. 60—with re

spect to the dismissal of the substantive charges laid

under Section 242 against the defendants without o f

ficial status. Counts 2, 3 and 4 of the indictment

allege that fifteen private persons, together with three

State officials, committed the offense defined in Sec

tion 242. Although they were all formally described

as “ acting under color of the laws of the State o f

Mississippi” (R. 13-14, 14, 15), the court below cor

rectly noted that “ [t.jhe indictment states that three

of the defendants were acting as officers in all that

they did, but then does not state or indicate that any

of the other individual defendants were officers in fact,

or de facto in anything allegedly done by them ‘under

color o f law’ ” (R. 20). The question is whether such

private persons can be prosecuted under Section 242

when they act in association with State officials.

W e present two answers to the ruling. First, we

argue that the close association alleged between the

private defendants and the State officials charged with

them makes all of them amenable to the statute as per

sons acting “ under color o f law,” albeit those without

official status do not become de facto officers. A l

ternatively, we urge that the private defendants, even

i f incapable of violating the statute on their own in

the circumstances of this case, are properly indicted as

aiders and abettors of persons with capacity to com

mit the offense.

12

I

SECTION 241 OF THE CRIMINAL CODE PROTECTS RIGHTS

SECURED BY THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE OF THE FOUR

TEENTH AMENDMENT

The question whether Section 241 punishes con

spiracies directed against Fourteenth Amendment

rights was fully canvassed in this Court less than

fifteen years ago in United States v. Williams, 341

U.S. 70, and the two major opinions in that case fully

explored the arguments on each side of the issue.

Against that background one hesitates to rehearse the

considerations involved once again. I f we do so

briefly it is only because, on that occasion, the Court

divided evenly and did not resolve the question—four

Justices, in an opinion by Mr. Justice Frankfurter, ex

pressing their view that Fourteenth Amendment

rights were not within the scope of Section 241 (341

U.S. at 71-82), four other Justices, in an opinion by

Mr. Justice Douglas, reaching the opposite conclusion

{id. at 87-96), and Mr. Justice Black voting to affirm

dismissal o f the charge on independent grounds {id.

at 85-86). Inevitably, our discussion will track much

of the opinion of Mr. Justice Douglas in that case and

will attempt to answer the objections raised by the

opinion of Mr. Justice Frankfurter.

Section 241, among other things, punishes “ per

sons” who conspire to interfere with the exercise or

enjoyment by a “ citizen” of “ any right or privilege

secured to him by the Constitution or laws of the

United States.” On its face, the provision is certainly

broad enough to reach conspiracies directed against

13

Fourteenth Amendment rights, and its enactment less

than two years after the ratification o f that Amend

ment— as Section 6 of the Enforcement Act o f 1870

(16 Stat. 140, 141)—would naturally support that in

ference. There is a heavy burden, it seems to us, on

those who would encumber the straightforward text

with a restrictive gloss to the effect that Section 241

does not protect all federal constitutional rights, in

cluding he rights then recently declared by the post

w ar Amendments.

The situation might be different if the narrow read

ing given Section 241 by the court below derived from

a venerable tradition initiated by judges who were

immediately familiar with the enactment of the pro

vision. But that is not the case. Indeed, until Wil

liams, there seems to have been no doubt expressed

on the point. As Mr. Justice Douglas there noted

(341 U.S. at 92-93), the early lower federal courts

had taken it for granted that Section 241 covered

Fourteenth Amendment rights. See United States

v. Hall, 26 Fed. Cas. 79 (S.D. A la ) ; United States v.

Mall, 26 Fed. Cas. 1147 (S.D. A la .) ; Ex parte Riggins,

134 Fed. 404 (iST.D. Ala.). And this Court had implied

as much. There were first a series o f cases involving

prosecutions of private individuals under Section 241

for alleged violations of Fourteenth Amendment rights

which were decided on constitutional grounds—pre

sumably on the premise that the statute reached viola

tions of the Amendment and that it was necessary to

determine the scope of the constitutional provision.

7S6-542— 6: 3

14

See, e.g., United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542;

Hodges v. United States, 203 U.S. 1; United States v.

Wheeler, 254 U.S. 281. Then came the decision in

Guinn v. ZJm'ied S'feA.s, 238 U.S. 347, where, in a case

involving a congressional election, the Court upheld a

prosecution under Section 241 which seems to have

rested wholly on an alleged violation of the Fifteenth

Amendment—which is no more within the scope of the

statute than the Fourteenth Amendment if the restric

tive view espoused in IFilliam is correct. On the same

day, in United States v. Mosley, 238 U.S. 383, 387-388,

the Court, speaking through Mr. Justice Holmes, char

acterized the “ sweeping general words” of Section 241

as dealing “ with Federal rights and with all Federal

rights,” “ in the lump.” The “ broad language of the

statute” was again noticed in United States v. Classic,

313 U.S. 299, and (albeit no Fourteenth Amendment

rights were involved), the Court seems to have as

sumed that Section 241 (then § 19), like Section 242

(then § 20), protects all constitutional rights. And, as

late as Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91— where

the Court explicitly ruled that Section 242 protects

rights guaranteed by the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment—no one took issue with Mr.

Justice Rutledge’s statement that there are “ no differ

ences in the basic rights guarded” by Sections 241 and

242. Id. at 119. As Mr. Justice Douglas has fully

shown (341 U.S. at 93-94), that decision also set at

rest the objection that Section 241 must necessarily

fail as unduly vague if construed to encompass Four

teenth Amendment rights.

15

Obviously the suggested limited scope of Section

241 does not appear on the surface—else three genera

tions of judges would not have overlooked it until

1950. Accordingly, we must look on the words more

critically and carefully assess them in their context.

And, lest the true meaning lie buried still deeper, we

must attempt to elucidate the sparse legislative his

tory of the provision.

A . T H E TEXT AND CONTEXT OF SECTION 241

The most convenient method for the initial inquiry

is to parse Section 241, phrase by phrase, focusing on

the restrictive implications attributed to each (by four

o f the Justices) in Williams.

1. “Persons.” It has been suggested that char

acterization of the offenders under Section 241 as

mere “persons” implies private individuals, acting

on their own, rather than State officials or persons

acting “ under color o f law,” and that the provision

therefore does not encompass Fourteenth Amendment

rights which only those wielding State power can

invade. See 341 U.S. at 76-78. The term “ persons”

was designedly used, it is said, to reach the members

of the Ku Klux Klan, the acknowledged object o f

Senator Pool who wrote the provision in question.

See United States v. Mosley, 238 U.S. 383, 387. The

significance of that usage is further illumined— so

goes the argument—when one notices that other pro

visions of the 1870 Act (where our provision origi

nated as Section 6) carefully delineated the scope of

coverage. Thus, Sections 2 and 3 of that Act were

directed to “ persons or officers” (16 Stat. 140) and

16

Section 17, now 18 U.S.C. 242, reached only

“ person[s] [acting] under color of * * * law” (16

Stat. 144).3 The suggestion apparently is that there

is a purposeful symmetry, dividing the measure into

three neat categories o f provisions— those which cover

only governmental action, those which reach only

private acts, and, finally, those which encompass

both—and that all o f this is confused, with resulting

overlapping, if the modern Section 241 is not con

fined to rights which are secured by the federal

Constitution or laws against private invasion.

Perhaps the short answer is that the entire argu

ment is constructed upon the false premise that

Congress can never reach invasion o f Fourteenth

Amendment rights by private persons. As we elab

orate in United States v. Guest, No. 65, this Term,

this was certainly not the assumption of those who

wrote Section 241, nor do we think it a correct state

ment o f constitutional law. But we do not rest there.

Even accepting the proposition that all legislation

under the Fourteenth Amendment must speak directly

to the State or those acting under its authority, the

argument derived from the use of the unqualified

word “ persons” in Section 241 does not hold up.

First, it is well settled that Section 241 reaches

both private and public action— offenses of mere indi

viduals acting on their own ( e.g., Ex parte Yarbrough,

110 U.S. 651; United States v. Waddell, 112 U.S. 76;

Logan v. United States, 144 U.S. 263; In re Quarles, 5

5 In the codification of Section 17 as Section 20 of the

Criminal Code of 1909 (35 Stat. 1092), “person” became

“whoever” and that change has been retained.

17

158 U.S. 532; Motes v. United States, 178 U.S. 458),

and acts o f State officials acting “ under color of law.”

E.g., Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347; United

States v. Mosley, 238 U.S. 383; United States v.

Classic, 313 U.S. 299; United States v. Saylor, 322

U.S. 385. That is an end of the distinction between

the provisions o f the 1870 Act which are directed

solely against non-governmental action and those

which encompass both officials and other Avrongdoers.

Section 241 has precisely the same scope as if it Avere

explicitly addressed to “persons or officers.”

Once that flaw is uncovered, the Avhole complicated

edifice built upon the choice of the word “ persons”

falls of its own weight. I f State officials are within

the statutoiy coverage, Ave can no longer rely on Sen

ator P oo l’s preoccupation with the Klan as implying

an intention to restrict the provision to private con

spiracies. Nor does fear o f overlapping among the

several provisions of the Enforcement Act of 1870

deter us, for, whether or not § 241 protects Fourteenth

Amendment rights, overlapping is now inevitable Avith

respect to the invasion of civil rights by State offi

cials. See, e.g., United States y. Classic, supra. W e

need merely answer with Mr. Justice Holmes, speak

ing for the Court in United States v. Mosley, supra,

238 U.S. at 387: “ Any overlapping that there may

have been might well have escaped attention, or if

noticed have been approved.”

To be sure, there subsists a difference between the

coverage of Section 241, Avhich encompasses both

private and official offenders, and Section 242, \Adiich

reaches only persons acting “ under color of any law,

18

statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom.” These

opening words of Section 242 were deemed appro

priate (or necessary) when the provision (originally

Section 17 of the Enforcement Act of 1870) protected

only a limited category of Fourteenth Amendment

equal protection rights.6 But, of course, it does not

6 As already noted, Section 242 derives from Section 17 of

the Enforcement Act of 1870 (16 Stat. 144). In relevant part,

that provision punished deprivations of “any right secured or

protected” by Section 16 of the Act, which, in turn (tracking

the language of the Civil Rights x\ct of 1866), guaranteed

“all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States * * *

the same right in every State and Territory in the United

States to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give

evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and

proceedings for the security of person and property as is en

joyed by white citizens.”

The subsequent history of the provision is traced by Mr.

Justice Rutledge in his concurring opinion in Screws v. United

States, 325 U .S. 91, 120:

“A t first §20 [now §242] secured only rights enumerated in

the Civil Rights Act. The first ten years brought it, through

broadening changes, to substantially its present form. Only

the word ‘willfully’ has been added since then, a change of

no materiality, for the statute implied it beforehand. 35 Stat.

1092. The most important change of the first decade replaced

the specific enumeration of the Civil Rights Act with the pres

ent broad language covering ‘the deprivation of any rights,

privileges, or immunities, secured or protected by the Constitu

tion and laws of the United States.’ R.S. 5510. This in

clusive designation brought §20 into conformity with §19’s

[now § 241] original coverage of ‘any right or privilege se

cured to him by the Constitution or laws of the United States.’

Since then, under these generic designations, the two have been

literally identical in the scope of the rights they secure. The

slight difference in wording cannot be one of substance.”

For the full text of each of the successive versions of Sec

tion 242— as well as Section 241— see the table appended to the

opinion of Mr. Justice Frankfurter in United States v. W il

liams, 341 U .S. at 83.

19

follow that the absence of a similar restriction in a

provision that protects rights secured against all cat

egories of offenders forecloses protection of Four

teenth Amendment rights. The statute need not

enumerate those with capacity to violate the Amend

ment: the Constitution itself does that. Indeed, since

the substantive coverage of Section 242 was broad

ened to include all federal constitutional and statu

tory rights (see Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91,

120 (concurring opinion of Mr. Justice Rutledge)),

the restriction of the provision to offenders wielding

State power has become somewhat anomalous. In

sofar as Section 242 now punishes* invasion of rights

also secured against private action (see United States

v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299), there is plainly no consti

tutional necessity for the restriction and the conse

quence is that individual offenses against such rights

are not federal crimes if no part of a conspiracy.

There is certainly no warrant for imputing to the

drafters of Section 241 the forced dilemma of cover

ing Fourteenth Amendment rights, i f at all, only by

restricting their entire provision to State officers.

The upshot is that there is a certain overlapping

between the predecessor of Section 241 and the other

provisions of the Enforcement Act of 1870—the area

of overlapping having increased since the expansion

of Section 242. But, as already noted, that is not a

sound argument against our reading of Section 241.

The fact is that the Act of 1870 is not a symmetrical

construction. It is a composite, hastily welded out

o f disparate pieces, attributable to a variety of spon

2 0

sors, each with his particular concern.7 As we shall

see, Senator Pool, the author of our provision, had

perhaps the broadest view and meant to cover all

rights against all interference, including those rights

recently declared by the Fourteenth Amendment,

which he thought Congress might safeguard against

both official and unofficial invasion.

2. “ Citizen.” Section 241 punishes only offenses

against citizens of the United States. See Baldtvin

v. Franks, 120 U.S. 678. Hence, it is argued that the

provision is concerned alone with rights appertaining

to national citizenship, not including the Fourteenth

Amendment rights to due process and equal protec-

7 Thus, Sections 1-4 of the Act— which are concerned solely

with the right to vote— derive from the parent bill reported

by the Senate Judiciary Committee as a substitute for other

voting measures before the Senate. Cong. Globe, 41st Cong.,

2d Sess., pp. 2942, 3479-3480. Sections 16 and 17— which re

enacted provisions of the Civil Eights Act of 1866 and ul

timately became Section 242 of the Criminal Code— are trace

able to an amendment submitted by Senator Stewart of Nevada.

Id., p. 3480. And Section 6— now our Section 241— , together

with Section 7, was proposed by Senator Pool. Id., pp. 3612,

3679. There were many other amendments, besides. See id.,

p. 3688 (comment of Senator Trumbull). Just before the bill

was finally passed {id., p. 3688), one Senator characterized

it as “a conglomeration of incongruities and contradictions”

and claimed no one knew its true content in light of the num

ber of amendments hastily adopted {ibid., Senator Thurman).

Another member accurately stated: “The bill as it now stands

is the child of many fathers. It is a piece of patchwork

throughout.” Ibid. (Senator Casserly). See, also, the opin

ion of Mr. Justice Frankfurter in United States v. Williams,

supra, at pp. 74-75, and n. 2.

21

tion which are not derived from citizenship or re

stricted to citizens. And, again, a contrast is made

with Section 242 which, like the Fourteenth Amend

ment itself, expressly protects every “ inhabitant” o f

the land, citizen or not.

Significantly, this argument has never gained a

foothold in this Court. Although the court of ap

peals, in Williams, had stressed the fact that Section

241 protects only the rights of citizens (see 179 F. 2d

at 647), nothing was made of the point by Mr. Justice

Frankfurter when the case came here. That is doubt

less because the argument immediately runs into an

insuperable barrier when we notice that, of all the

rights held to be protected by Section 241, none is

peculiar to citizens. It is so with respect to the right

to vote in congressional elections (Ex parte Yar

brough, supra; Guinn v. United States, supra; United

States v. Mosley, supra; United States v. Classic,

supra; United States v. Saylor, supra), which is not

derived from citizenship or necessarily restricted to

citizens. Minor v. Happersett, 21 Wall. 162; Pope v.

Williams, 193 U.S. 621, 632-633. And the same is true

of the right to peaceful enjoyment o f federal home

steads (United States v. Waddell, supra) which were

open to aliens who had merely declared their intention

to become citizens (Rev. Stat. 2289), of the right to be

secure against unauthorized violence when in federal

custody (Logan v. United States, supra), and of

the right to inform on violations of the Federal tax

786-542—65- 4

22

laws (In re Quarles, supra; Motes v. United States,

supra) .8

W e can speculate why Section 241 was written to

protect citizens alone. Perhaps there was a conscious

purpose to avoid encompassing Indians who were not

generally viewed as naturalized by the Fourteenth

Amendment. See Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94; James,

The Framing of the Fourteenth Amendment (1956),

p. 143. But, without doubt, the primary focus was on

the Negro in the reconstructed States, recently eman

cipated and now granted citizenship; for that pur

pose, it was enough to protect all citizens. Section

242, on the other hand, was explicitly written to pro

tect aliens as well as Negro citizens, as the text makes

clear. Moreover, in using the word “ inhabitant” it

was merely tracking the language of the Civil Rights

Act of 1866 (14 Stat. 27) which assured the recently

emancipated slaves, not yet citizens, some of the same

8 Mr. Justice Frankfurter’s opinion for four members of the

Court in Williams can be read as characterizing the right to

vote in federal elections and the rights vindicated in Logan,

Quarles and Motes as rights of national citizenship (see 341 U.S.

at 77, 79-80). While that description would not be wholly ac

curate, the point is not important in light of the explicit rec

ognition that the right involved in United States v. Waddell,

supra, “did not pertain to United States citizenship” (id. at

80), and the conclusion of the opinion that the category of

rights protected by Section 241 are those “arising from the sub

stantive powers of the Federal Government” (id. at 73, 77, 78,

79, 82)— rather than only those appertaining to national citi

zenship. In United States v. Guest, No. 65, this Term, we note

our difficulty with the proposition that the Fourteenth Amend

ment (and presumably also the Fifteenth) did not— by its

Fifth Section— enlarge the “substantive powers” of the national

government. See Brief for the United States, pp. 18-46.

23

rights as were “ enjoyed by white citizens” . See note

6, supra, p. 18. In sum, the substantive coverage of

these provisions does not depend on the class o f per

sons protected: just as Section 242 originally secured

a narrow group of rights for everyone, Section 241

protects only a limited class (citizens) but with re

spect to all federal rights.

3. u[R]ight or privilege [granted or] secured * * *

by the Constitution or laws of the United States.” As

originally enacted (as Section 6 of the Act o f 1870),

Section 241 was directed at the invasion of “ any right

or privilege granted or secured” to citizens by the fed

eral Constitution or statutes. The word “ granted”

was dropped four years later when the federal statutes

were revised. See Rev. Stat. § 5508. Presumably, this

was done on the ground that the word “ granted”— at

best a mere alternative descriptive separated by a dis

junctive—was surplusage, for the “ revision” of 1874

was not meant to alter substance. See 14 Stat. 74; 16

Stat. 96. Nevertheless, apparently focusing on that

word, and contrasting the present language o f Sec

tion 242 (“ rights, privileges, or immunities secured or

protected by the Constitution or laws of the United

States” ), it has been argued that the “ narrow phase”

of Section 241 does not cover Fourteenth Amendment

rights. See 341 U.S. at 78.

The proposition is difficult to grasp. Insofar as

any contrast between the language of Section 241

and Section 242 is appropriate, the argument seems

reversed. Indeed, if one or the other o f the two

provisions must be restricted to rights o f national

citizenship, an echo of the “ privileges or immunities”

24

clause o f the Fourteenth Amendment is more obvious

in Section 242 ( “ rights, privileges, or immunities” )

than in Section 241 ( “ right or privilege” ). And the

absence of the word “ granted” in Section 242 and its

presence in the predecessor of Section 241 suggests,

if anything, that the former provision deals only with

pre-existing rights inherent in national citizenship,

not conferred by the Fourteenth Amendment, but

merely re-affirmed by it and .guaranteed (somewhat

redundantly) against contrary State laws, whereas the

latter section (§241) protects the new constitutional

rights declared for the first time by the Due Process

and Equal Protection Clauses of the Amendment.

But the comparison, in any event, is wholly mis

leading, for the two texts put in opposition are not

o f the same date. The phrase “ secured or protected”

in Section 242 is directly derived from the Civil

Rights Act of 1866 (see note 6, supra, p. 18) written

some years before Section 241. That the rights in

volved are not described as “ granted” may well be

due to the fact that there, as well as in the 1870

text, the direct reference was to a previous section

o f the same statute—not the Constitution—which was

viewed as merely implementing rights already con

ferred by the Thirteenth or Fourteenth Amendment.

The rest o f the quoted language of Section 242 was

substituted in 1874 for a longer and very different

phrase o f apparently narrower content in the original

provision of 1870. See note 6, supra, p. 18. And

at the same time that new text came into the law

the word “ granted” was deleted from Section 241.

25

Plainly nothing can be learned by now comparing

the language of two provisions which have wholly

different verbal histories.

Comparisons aside, there is nothing in the char

acterization of the rights protected by Section 241

which excludes the rights to due process and equal

protection conferred by the Fourteenth Amendment.

To be sure, the Due Process and Equal Protection

Clauses did not grant absolute rights, good against

the world: the Amendment only deals with the rela

tionship between the inhabitant and the State. But

even if they run only against the State, these are

nevertheless properly termed “ rights,” “ granted,” or

at least “ secured” by the Constitution. As this Court

said in the Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 1, 11, “ Posi

tive rights and privileges are undoubtedly secured

by the Fourteenth Amendment.” See, also, Strauder

v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 307-308; Ex parte

Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 345. That this was the usage

of the time is illustrated by Section 17 of the 1870

Act (the predecessor of § 242) which referred to the

equal protection guarantees enumerated in the pre

vious section as “ right[s] secured or protected” by

that provision. Note 6, supra, p. 18.

B. THE LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF SECTION 2 4 1

W e have seen that the most painstaking analysis

of the text of Section 241, viewed alone and in the

context of the statute where it originated, merely

confirms what the language, on its face, indicates:

that the provision broadly punishes conspiracies in

terfering with all federal rights, including those de

clared by the Fourteenth Amendment. It only re-

26

mains to notice that the immediate legislative history

of Section 241 fully supports that conclusion.

W e begin with the seemingly decisive fact that Sen

ator Pool, introducing Section 241 in its original

form, explicitly referred to “ rights which are con

ferred upon the citizen by the fourteenth amendment”

as among those covered by his provision. Cong.

Globe, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. 3611; id., at 3613 (App.,

infra, pp. 43, 48).9 There is no explaining away that

statement. In context, it is clear that the sponsor of

the provision had in mind the rights conferred by

the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses and

not, as has been suggested (341 U.S. at 76-77, n. 4),

the pre-existing rights of national citizenship avail

able for the first time to those whom the Amendment

made citizens and now expressly guaranteed against

State invasion by the new Privileges and Immunities

Clause. The indications are numerous.

First, Senator Pool expressly invoked the language

of the due process and equal protection guarantees

of the Amendment. He showed his particular con

cern with the Equal Protection Clause by stressing

the use of the word “ deny” in that provision “ in

contradistinction” to the mere prohibition against a

State “ making or enforcing latvs” abridging the priv

ileges and immunities of national citizenship in the

first clause— arguing that here the State’s obligation

was affirmative and that, in the event o f default, con-

8 W e have reproduced as an appendix (infra, pp. 37-50) the

whole ox Senator Pools speech introducing the amendment

which became Section 6 of the Enforcement Act of 1870, and,

ultimately, Section 241 of the Criminal Code. It is the only

pertinent text of legislative history.

27

gressional power was therefore greater. Id., at 3611

(App., infra, pp. 40-41). In light of later decisions,

beginning with the Slaughter-House Cases, 16 Wall.

36, the Senator was o f course correct in neglecting the

rights “ conferred” by the Privileges and Immunities

Clause: whatever they are, they pre-existed the Four

teenth Amendment and could be secured against State

invasion without benefit of the new Amendment.

Again, in the same passage, Senator Pool makes

repeated reference to the Civil Rights Act of 1866

and indicates that those rights, among others, are

those which his measure will protect. Ibid. As we

know, those are basically equal protection rights, now

vindicated (along with rights derived from the Due

Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and

others) by Section 242.

Finally, the sponsor’s purpose to protect the right

secured by the Fifteenth Amendment against the ac

tion of hostile conspiracies is unmistakable. Ibid.

(App., infra, pp. 40-43). Yet, that right is no more

a right “ appertaining to national citizenship” or one

derived “ from the substantive powers of the federal

government” than are those secured by the Due

Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment. Having strayed so far from the

narrow category of rights it is said he was concerned

with, it seems highly imlikely that the sponsor should

have stopped short of including all Fourteenth

Amendment rights—which he mentions in one breath

with the right secured by the Fifteenth Amendment.

Id., at 3611, 3613 (App., infra, pp. 40, 43, 48).

To be sure, Senator Pool believed the rights pro

tected by his bill could be secured against private in-

28

terference as well as State denial. Id. at 3611-3613

(App., infra, pp. 38-49). But that does not tend to

indicate that he meant to exclude rights derived from

those constitutional provisions which are explicitly-

directed to States alone. As we have noted, he meant

to cover the right guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amend

ment which presents the identical problem. See

James v. Bowman, 190 U.S. 127. Plainly, he thought

that Congress might legislate to protect Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendment rights against the action of

private conspiracies whenever the State had failed ot

effectively secure those rights. W e advance a like

contention in United States v. Guest, No. 65, this

Term. Whether he was right or wrong, however, does

not matter here. The provision enacted is carefully

limited to “ rights secured by the Constitution” ; its

scope is measured by the constitutional provision in

volved. As Mr. Justice Holmes noted in United

States v. Mosley, supra, 238 U.S. at 387, here “ Con

gress put forth all its powers” ; it meant to afford

all possible protection but it was careful not to over

step the constitutional line, wherever it might later be

drawn.

II

SECTION 242 OF THE CRIMINAL CODE REACHES PRIVATE

INDIVIDUALS WHO ACT IN ASSOCIATION WITH STATE

OFFICERS TO CARRY OUT A SCHEME TO INVADE RIGHTS

SECURED BY THE PROVISION.

As we have already noted, the two indictments be

fore the Court clearly charge violations of specific

rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. It

is settled that such conduct “ under color of law,” if

29

done willfully as here alleged, contravenes Section 242

of the Criminal Code. Screws v. United States, 325

U.S. 91; Williams v. United States, 341 U.S. 97. Ac

cordingly, the court below sustained the indictment in

No. 60 with respect to the defendants who hold State

office and were alleged to be acting officially (albeit

illegally). But—while upholding as to all the charge

of conspiring to violate Section 242—the court dis

missed the substantive charges against the private de

fendants on the ground that they lacked capacity to

commit the offense defined by Section 242. W e think

the ruling erroneous, first, because, in the circum

stances alleged, the private defendants, although not

State officials, were acting “ under color of law” with

in the meaning of the statute; and, second, because, !

regardless of their capacity to themselves commit the

offense, they are amenable to Section 242 as aiders

and abettors of the State officials charged.

A. The trial judge correctly observed that the in

dictment in No. 60 does not claim that fourteen of

the defendants were public officials of the State of

Mississippi, de jure or de facto. On the other hand,

the substantive counts (R. 13-16) explicitly charge

that each of the defendants, including those who held

no official position, were “ acting under color of the

laws of the State of Mississippi,” and the indictment,

as a whole, alleges that all of them were joint con

spirators, the private defendants acting in close as

sociation with those who were law enforcement officers,

one of whom was present at all times and presumably

lent the protective umbrella of his office to all that

30

was done. Thus, it is apparent that the court below

held that private persons are never amenable to the

sanctions of Section 242, no matter what the circum

stances. Otherwise, the allegation of action “ under

color of law” , in the language of the statute, should

have required upholding the charge. In effect, the

ruling is that none but State officers can act “ under

color of law” within the meaning of Section 242. The

proposition, we submit, is untenable.

Certainly, nothing in the nature of the rights pro

tected by Section 242 requires confining its reach to

State officers in all circumstances. Indeed, it has long

been settled that the conduct of private persons may

be subject to the prohibitions of the Fourteenth

Amendment i f the State, through its officers, “ has so

far insinuated itself into a position of interdepend

ence * * * that it must be recognized as a joint par

ticipant in the challenged activity.” Burton v. Wil

mington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715, 725. There

are many variations, E.g., Pennsylvania v. Board of

Trusts, 353 U.S. 230; Peterson v. City of Greenville,

373 U.S. 244; Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267;

Griffin v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 130; Robinson v. Flor

ida, 378 U.S. 153. But the basic situation is always

the same: a private activity falls within the scope of

the Fourteenth Amendment because— albeit without

assuming full official status or altogether losing its

private character— it becomes involved in a “ joint

venture” of soils with the State. That is our case.

I f the scope of action “ under color of law” is co

extensive with “ State action” under the Fourteenth

31

Amendment— as is usually tacitly assumed 10—the de

cisions just cited end the question. But there are, in

any event, like rulings construing the phrase “ under

color of law” in 18 U.S.C. 242 or its civil counterpart,

42 U.S.C. 1983—where it has the same meaning.

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167, 185. Thus, in Baldwin

v. Morgan, 251 F. 2d 780, 788 (C.A. 5), the court re

jected a claim that private persons were not acting

“ under color of any law” in these words:

State action is indeed required under the

Fourteenth Amendment and 42 U.S.C.A. § 1983.

But those who directly assist the admitted state

agency in carrying out the unlawful action be

come a part of and subject to the sanction of

Section 1983. * * *

See, also, Smith v. Holiday Inns of America, 336 F.

2d 630 (C.A. 6 ) ; Hampton v. City of Jacksonville, 304

F. 2d 320 (C.A. 5) ; Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Me

morial Hospital, 323 F. 2d 959 (C.A. 4 ) ; Valle v.

Stengel, 176 F. 2d 697 (C.A. 3).

10 Thus, most of the modern cases construing the Fourteenth

Amendment were filed under 28 U.S.C. 1343(3) which gives

the district courts jurisdiction of civil cases to redress depriva

tion of constitutional rights “under color of any State law,

statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or usage,” and the in

junction was sought and granted under 42 U.S.C. 1983 which

provides for equitable relief from a deprivation of constitution

al right “under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, cus

tom, or usage, of any State or Territory.” See, e.g.. Turner v.

City of Mem,phis, 369 U.S. 350, 351; McNeese v. Board of Edu

cation, 373 U.S. 668, 671; Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 537.

The assumption apparently indulged is that whatever violates

the Amendment necessarily was done “under color of law.”

32

Closest in point, perhaps, is United States v. Lynch,

94 F. Supp. 1011 (N.D. Ga.), affirmed, 189 F. 2d 476

(C.A. 5), certiorari denied, 342 U.S. 831, a case strik

ingly similar to ours. There, it was charged that a

sheriff and his deputy arrested several persons and

“ turn[ed] them over to a hooded group in disguise to

be beaten.” On these facts the court held:

While it is true that one must be acting under

color of state law in order to violate Section 242,

and that ordinarily a private citizen would not

act under color of law, it is also true that the

presence of state officers and their active par

ticipation with other defendants who were not

officers would furnish the “ color of law” re

quired as to all the defendants. [94 F. Supp.

at 1014. J11

W e conclude, as in Lynch, that when the private

members of the mob knowingly linked hands with

the officers to carry out a common plan to deprive

Schwerner, Goodman and Chaney of their constitu

tional rights they lost their claim to be treated as

mere private citizens. Having united with State

officials and invoked the protective umbrella of their

presence, the private defendants were acting “ under

color o f law” and became amenable to the sanctions

of Section 242.

11 See, also, Downie v. Powers. 193 F. 2d 760 (C.A. 10), where

the court held that “ * * * a wilful or purposeful failure of the

Chief of Police or other City officials to preserve order, keep the

peace, and to make the Jehovah’s Witnesses secure in their

right to peaceably assemble, would undoubtedly constitute ac

quiescence in, and give color of law to, the actions of the mob.”

193 F. 2d at 764. And see 'Williams v. United States, 179 F. 2d

656 (C.A. 5 ), affirmed, 341 U.S. 97.

33

B. In addition, the substantive charges against the

private defendants should have been sustained on the

ground that they may have been aiders and abettors

of the State officers jointly indicted. While that rela

tionship is suggested by the language of indict

ment, it is true that the private defendants are for

mally charged as principals, as themselves acting

“ under color of the laws of the State of Mississippi.”

But, as already noted (note 4, supra, p. 9), indict

ment as a principal is no bar to conviction as an

aider or abettor (which, in turn, permits punishment

as a principal).12

The governing principle that one without capacity

to commit an offense may nevertheless be convicted

if he aided and abetted its commission is well settled.

The rule is embodied in 18 U.S.C. 2(a) which provides

that “ [wjhoever * * * aids, abets, counsels, com

mands, induces, or procures [the] commission [o f an

offense against the United States] is punishable as a

principal.” Whatever doubt there may have been that

persons lacking capacity to commit the substantive

offense were covered was removed in 1951 when the

12 See, in addition to the authorities cited at note 4, supra,

p. 9, United States v. Russo, 284 F. 2d 539 (C .A. 2 ) ; Swanne

Soon Young Pang v. United Stales, 209 F. 2d 245 (C.A. 9) ;

United States v. Knickerbocker Fur Coat Co., 66 F. 2d 388

(C.A. 2 ) ; Melting v. United States, 25 F. 2d 92 (C.A. 7 ) ;

DiPreta v. United States, 270 Fed. 73 (C.A. 2 ) ; Vane v. United

States, 254 Fed. 32 (C.A. 9 ) ; United States v. Snyder, 14 Fed.

554 (D. Minn.) ; United States v. Palermo, 172 F. Supp. 183

(E.D. N .Y .) ; United States v. ■/. R. Watkins C o 127 F. Supp.

97 (D. M inn .); United States v. Selph, 82 F. Supp. 56 (S.D.

C a l.) ; United States v. Decker, 51 F. Supp. 20 (D. M d.).

34

aider and abettor statute was amended to read as it

does now. The report accompanying that legislation

(S. Rep. No. 1020, 82d Cong., 1st Sess., p. 7) ex

plicitly states:

This section is intended to clarify and make

certain the intent to punish aiders and abettors

regardless of the fact that they may be in

capable of committing the specific violation

which they are charged to have aided and

abetted. * * *

The judicial decisions are in accord. See Wilson

v. United States, 230 F. 2d 521, (C.A. 4 ) ; Koehler v.

United States, 189 F. 2d 711, (C.A. 5 ) ; May v.

United States, 175 F. 2d 994 (C.A. D .C .); Haggerty

v. United States, 5 F. 2d 224 (C.A. 7 ) ; Barron v.

United States, 5 F. 2d 799, (C.A. 1) ; United States v.

Snyder, 14 Fed. 554 (D. M inn .); United States

v. Melekh, 193 F. Supp. 586, (N.D. 111.); United

States v. Bayer, 4 Dill. 407, 24 Fed. Cas. 1046 (D.

Minn.). The Wilson and Snyder cases make it clear

that the rule applies when the aider and abettor is

incapable of committing the offense because he is not

acting “ officially” or does not hold the described

public office. Thus, in Wilson, the statute (now 18

U.S.C. 201) reached only the solicitation or accept

ance of bribes by a government officer acting in his

“ official capacity” and the court sustained the con

viction of one who claimed not to be so acting on

the alternative ground that he was, in any event,

punishable as an aider or abettor. And in Snyder,

a co-defendant who was not himself a postmaster but

had aided and abetted the postmaster was held ac

countable under a statute that punished “ [a]ny post

35

master who shall make a false return to the auditor

for the purpose of fraudulently increasing his

compensation. ’ ’

The same rule applies with respect to Section 242.

Thus, in Koehler v. United States, supra, a State o f

ficer and one Ackermann, who was a private indi

vidual,13 were jointly indicted for violating Section

242 and the court sustained Ackermann’s conviction

for having “ aided, abetted and counseled Koehler in

the commission of this otfense” , finding that the “ evi

dence conclusively reveals that Ackermann and Koehler

were acting in concert in perpetrating the offense”

and that Ackermann was “ assisting” Koehler. 189

F. 2d at 712-714. Likewise, in United States v.

Lynch, 94 F. Supp. 1011 (K.D. Ga.), affirmed, 189 F.

2d 476 (C.A. 5), certiorari denied, 342 U.S. 831, some

of the defendants were police officials and others were

private citizens. In answer to the private defendants’

argument that they could not violate Section 242 “ be

cause it related only to deprivations by a state,” the

district court ruled (94 F. Supp. at 1013):

True, Section 242 was enacted pursuant to the

Fourteenth Amendment and relates to depriva

tions by states (acting through state officials)

and not to acts of private individuals. It does

13 Although the Koehler opinion itself does' not explicitly

state that Ackermann was a private person, a subsequent opin

ion of the same court describes the Koehler case as one “in

which a private citizen assisted a constable in a brutal assault

and unlawful imprisonment * * *” Baldtvin v. Morgan, 251 F.

2d 780, 789 (C.A. 5). Thus the court below was in error

when, in referring to the Koehler case, it stated that “Acker

mann was not a mere private citizen * * *” (It. 21).

36

not follow, however, that private individuals

cannot be guilty as principals if they aid and

abet state officers in such violations. Section 2,

Title 18, United States Code Annotated.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgments of the

district court dismissing the indictment in No. 59 in

its entirety and parts of three counts of the indict

ment in No. 60 should be reversed and the causes

remanded for trial.

Respectfully submitted.

T hurgood Marshall,

Solicitor General.

John Doar,

Assistant Attorney General.

Louis F. Claiborne,

Assistant to the Solicitor General.

Gerald P. Choppin,

P eter S. Smith ,

Attorneys.

September 1965.

A P P E N D IX

Remarks of Senator Pool of North Carolina on

sponsoring Sections 5, 6 and 7 of the Enforcement

Act of 1870 (Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 2d Sess., pp.

3611-3613).

Mr. P ool. Mr. President, the question in

volved in the proposition now before the Senate

is one in which my section of the Union is par

ticularly interested; although since the ratifica

tion of the fifteenth amendment, which we are

now about to enforce by appropriate legisla

tion, other sections of the country have become

more or less interested in the same question.

It is entering upon a new phase of reconstruc

tion; that is, to enforce by appropriate legis

lation those great principles upon which the

reconstruction policy of Congress was based.

I said upon a former occasion on this floor

that the reconstruction policy of Congress had

been progressive, and that it was necessary that

it should be progressive still. The mere act

of establishing governments in the recently in

surgent States was one thing; the great prin

ciples upon which Congress proposed to pro

ceed in establishing those governments was

quite another thing, involving principles which

lie at the very foundation of all that has been

done, and which are intimately connected with

all the results that must follow from that and

from the legislation of Congress connected with

the whole subject.

Mr. President, the first thing that was done

was the passage of the thirteenth amendment,

by which slavery in the United States was

abolished. By that four millions of people

( 3 7 )

38

were taken out from under the protecting hand

of interested masters and turned loose to take

care of themselves. They were turned loose

and put upon their own resources in communi

ties which were imbued with prejudices against

them as a race, communities which for the most

part had for years past—indeed from the very

time when those who are now in existence were

born—been taught and had instilled into them

a prejudice against the equality which has been

attempted to be established for the colored

citizens of the United States.

Mr. President, the condition which that thir

teenth amendment imposed on the late insur

rectionary States was one which demanded the

serious consideration and attention of this Gov

ernment. The equality which by the thirteenth,

fourteenth, and fifteenth amendments has been

attempted to be secured for the colored men,

has not only subjected them to the operation

of the prejudices which had theretofore existed,

but it has raised against them still stronger

prejudices and stronger feelings in order to

fight down the equality by which it is claimed

they are to control the legislation o f that section

o f the country. They were turned loose among

those people, weak, ignorant, and poor. Those

among the white citizens there who have sought

to maintain the rights which you have thrown

upon that class o f people, have to endure every

species of proscription, of opposition, and of

vituperation in order to carry out the policy

of Congress, in order to lift up and to uphold

the rights which you have conferred upon that

class. It is for that reason not only necessary

for the freedmen, but it is necessary for the

white people of that section that there should be

stringent and effective legislation on the part

of Congress in regard to these measures of

reconstruction.

39

We have heard on former occasions on the

floor o f the Senate that there were organizations

which committed outrages, which went through

communities for the purposes, of intimidating