Dowell v. Oklahoma City Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dowell v. Oklahoma City Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1988. 2afe1325-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b148e474-7edf-4a6e-962e-eec8aa8f1b77/dowell-v-oklahoma-city-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

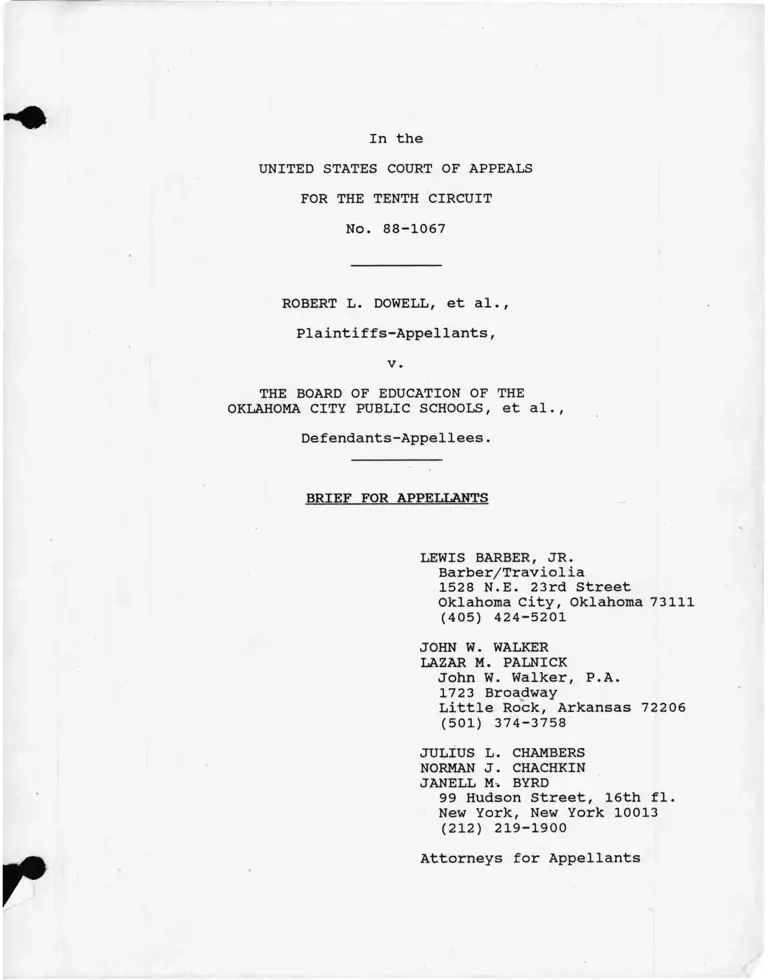

In the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

No. 88-1067

ROBERT L. DOWELL, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

OKLAHOMA CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

LEWIS BARBER, JR.

Barber/Traviolia

1528 N.E. 23rd Street

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73111

(405) 424-5201

JOHN W. WALKER

LAZAR M. PALNICK

John W. Walker, P.A.

1723 Broadway

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

(501) 374-3758

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

JANELL M> BYRD

99 Hudson Street, 16th fl.

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Appellants

In the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

No. 88-1067

ROBERT L. DOWELL, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

OKLAHOMA CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

CERTIFICATION REQUIRED BY 10th CIR. R. 28.2 ( a )

The undersigned certifies that the following parties or attor

neys are now or have been interested in this litigation or any

related proceedings. These representations are made to enable

judges of the Court to evaluate the possible need for disqualifi

cation or recusal.

Robert L. Dowell, a minor, by his father A.L. Dowell (plain

tiff) ;

Vivial C. Dowell, a minor, by her father A.L. Dowell; Edwina

Houston Shelton, a minor, by her mother Gloria Burse; Gary Rus

sell, a minor, by his father George Russell; Stephen S. Sanger,

Jr. (intervening plaintiffs);

Yvonne Monet Elliot and Donnoil S. Elliot, minors, by their

father Donald R. Elliot; Diallo K. McClarty, a minor, by his mother

Donna R. McClarty; Donna Chaffin and Floyd Edmun, minors, by their

mother Glenda Edmun; Chelle Luper Wilson, a minor, by her mother

Clara Luper; Donna R. Johnson, Sharon R. Johnson, Kevin R. Johnson,

and Jerry D. Johnson, minors, by their mother Betty R. Walker; Lee

Maur B. Edwards, a minor, by his mother Elrosa Edwards; Nina Hamil

ton, a minor, by her father Leonard Hamilton; Jamie Davis, a minor,

by his mother Etta T. Davis, and Romand Roach, a minor, by his

mother Cornelia Roach (intervening plaintiffs);

l

The Board of Education of the Oklahoma City Public Schools,

Independent District No. 89, Oklahoma County, Oklahoma, a public

body corporate? Jack F. Parker, Superintendent of the Oklahoma

City Public Schools; M.J. Burr, Assistant Superintendent of the

Oklahoma City Public Schools; Otto F. Thompson, Melvin P. Rogers,

Phil C. Bennett, William F. Lott, Mrs. Warren F. Welch, Luke F.

Skaggs, Jr., Foster Estes, and their successors as members of the

Board of Education of the Oklahoma City Public Schools, Independent

District No. 89; William C. Haller, County Superintendent of

Schools of Oklahoma County, Oklahoma, and his successors (defen

dants) ;

Jenny Mott McWilliams and David Johnson McWilliams, minors,

by their father William Robert McWilliams? Renee Hendrickson,

Bradford Hendrickson, Cindy Hendrickson, and Teresa Hendrickson,

minors, by their mother Donna P. Hendrickson; Donna P. Hendrickson

(intervening defendants);

John E. Green, Esq., U. Simpson Tate, Esq., E. Melvin Porter,

Esq., Archibald Hill, Esq., John W. Walker, Esq., Philip E. Kaplan,

Esq., Lewis Barber, Jr., Esq., Jack Greenberg, Esq., James M.

Nabrit, III, Esq., Derrick A. Bell, Jr., Esq., Sylvia Drew Ivie,

Esq., Michael Henry, Esq., Norman J. Chachkin, Esq., Julius LeVonne

Chambers, Esq., Theodore M. Shaw, Esq., Napoleon B. Williams, Esq.,

Janell M. Byrd, Esq. (counsel for plaintiff and intervening plain

tiffs) ;

W .A . Lybrand, Esq., Coleman Hayes, Esq., J. Harry Johnson,

Esq., J. Howard Edmondson, Esq., Joe Canno, Esq., Robert H. Warren,

Esq. , Leslie Conner, Esq., Robert Chase Gordon, Esq., Ronald L.

Day, Esq., Laurie W. Jones, Esq., D.K. Cunningham, Esq., Curtis

P. Harris, Esq. (counsel for defendants);

Calvin W. Hendrickson, Esq., Robert J. Emery, Esq., Hugh A.

Baysinger, Esq. (counsel for intervening plaintiffs);

George F. Short, Esq., Norman F. Reynolds, Esq., George S.

Guysi, Esq., William G. Smith, Esq., Harold G. Thweat, Esq., Robert

C. Warren, Esq. (counsel for intervening defendants)?

Robert D. Looney, Esq., Thomas C. Smith, Jr., Esq., Val R.

Miller, Esq., Hon. William S. Price, Esq., Hon. William Bradford

Reynolds, Esq., David K. Flynn, Esq., Mark L. Gross, Esq. (counsel

for amici curiae).

lants

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Certification Required by 10th Cir. R. 28.2(a) . . . . i

Table of Authorities................................... iv

Preliminary Statement as to Jurisdiction ............. 1

Issues on Appeal ........................................ 1

Statement of the C a s e ................................. 3

Introduction ...................................... 3

Procedural History ............................... 3

Statement of Facts ............................... 5

A. Public School Desegregation in

Oklahoma C i t y ............................. 5

B. Elementary School Resegregation ......... 8

C. Justifications for the New P l a n ......... 12

D. The District Court's Ruling ............. 18

ARGUMENT —

Introduction and Summary ........................ 22

I The District Court Failed To Give Effect

To This Court's Remand Directions In 1986

And Erred As A Matter Of Law In Requiring

A New Showing Of Discriminatory Intent . . . 25

II The District Court Erred As A Matter Of Law

And Made A Clearly Erroneous Finding When It

Determined That The Impact Of Prior Racially

Discriminatory Policies Of Oklahoma City

School Authorities Had Become Too Attenuated

To Warrant Continued Enforcement Of The 1972

Remedial Decree In This C a s e ........... .. . 3 3

III The District Court Should Have Ordered The

Finger Plan Modified To More Nearly Equalize

The Burdens On Black And White Students Rather

Than Dissolving Its Decree Entirely . . . . 40

iii

Conclusion............................................... 49

Statement As To Oral A r g u m e n t ........................ 50

Appendix: Opinion and Judgment of District Court . . la

Table of Authorities

Cases:

Arvizu v. Waco Independent School District, 495 F.2d

499 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) .................................... 44n

Booker v. Special School District No. 1, 585 F.2d 347

(8th Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 443 U.S. 915 (1979) 44n

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 338 F. Supp. 67

(E.D. Va.), rev'd on other grounds, 462 F.2d 1058

(4th Cir. 1972), aff'd by equally divided court,

412 U.S. 92 (1973) ............................... 17n

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

483 ( 1 9 5 4 ) ........................... 6, 14, 22, 23, 25, 29

Brown v. Board of Education, 349U.S. 294 (1955) . . . 29

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 432

F . 2d 875 (5th Cir. 1970) lln

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) ......... 35

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449

(1979) lln

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S.l (1958) .................... 46n

Correll v. Easley, 237 P.2d 1017 (Okla. 1951) . . . . 16n

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 721

F . 2d 1425 (5th Cir. 1 9 8 3 ) .............................. 46n

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 443 U.S.

526 (1979) ........................................ lln, 31

Table of Contents (continued)

Page

- iv -

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

Dowell v. Board of Education of Oklahoma City,

795 F .2d 1516 (10th Cir.), cert, denied,

107 S. Ct. 486 (1986) ....................

Dowell v. Board of Education of Oklahoma City,

606 F. Supp. 1548 (W.D. Okla. 1985), rev'd

and remanded, 795 F.2d 1516 (10th Cir.),

cert, denied, 107 S. Ct. 420 (1986) . . .

Dowell v. Board of Education of Oklahoma City,

338 F. Supp. 1256 (W.D. Okla.), aff'd, 465

F .2d 1012 (10th Cir.), cert, denied, 409

U.S. 1041 (1972) ............................. 3, 7n,

Dowell v. Board of Education of Oklahoma City,

244 F. Supp. 971, 976 (W.D. Okla. 1965), aff'd

in pertinent part, 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir.), cert,

denied, 387 U.S. 931 (1967) ......................

Dowell v. Board of Education of Oklahoma City,

219 F. Supp. 427, 431 (W.D. Okla.

1 9 6 3 ) ................................. 6, 16n, 17n,

Dowell v. Board of Education of the Oklahoma City

Public Schools, No. CIV-9452 (W.D. Okla.

Jan. 18, 1977) ...................................

Evans v. Buchanan, 512 F. Supp. 839 (D. Del. 1981) . .

Hemsley v. Hough, 157 P.2d 182 (Okla. 1945) .........

Hemsley v. Sage, 154 P.2d 577 (Okla. 1944) ...........

Higgins v. Board of Education of Grand Rapids, 508

F .2d 779 (6th Cir. 1974) ........................

Keyes v.

189

School

(1973)

District No. 1# Denver, 413 U.S.

Keyes v. School District No. If Denver, 521 F .2d

465 (10th Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 423 U.S.

1066 (1976) ...................................

King-Seeley Thermos Company v. Aladdin Industries,

Inc., 418 F .2d 31 (2d Cir. 1969) ...........

passim

4

3 6n, 48

, 7, 34n

36n, 40n

8n

44n

16n

16n

47

36n, 40

44n

44n

v

Lee v. Russell County Board of Education, 563 F.2d

1159 (5th Cir. 1977) lln

Lee v. Walker County School System, 594 F.2d 156 (5th

Cir. 1979) lln

Liddell v. State of Missouri, 731 F.2d 1294 (8th Cir.

1 9 8 4 ) ............................................... 48a

Lyons v. Wallen, 133 P.2d 555 (Okla. 1 9 4 1 ) ........... 16n

Mays v. Board of Public Instruction of Sarasota County,

428 F . 2d 809 (5th Cir. 1970) .................... lln

McPherson v. School District No. 186, 426 F. Supp. 173

(S.D. 111. 1976) 44n

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of Jackson, 391 U.S.

450 (1968) 46n

Morgan v. Kerrigan, 530 F.2d 401 (1st Cir.), cert, denied,

426 U.S. 935 (1976)............................... 46n

Morgan v. Nucci, 831 F.2d 313 (1st Cir. 1987) . . . . 30n

Parent Association of Andrew Jackson High School v.

Ambach, 598 F.2d 705 (2d Cir. 1 9 7 9 ) ............. 47

Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler, 427 U.S.

424 ( 1 9 7 6 ) ............................... 30n, 42, 43n, 44

Riddick v. School Board of Norfolk, 784 F.2d 521 (4th

Cir.), cert, denied, 107 S. Ct. 486 (1986) . . . 30n, 47

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982).................. 35

Securities and Exchange Commission v. Jan-dal Oil &

Gas, Inc., 433 F.2d 304 (10th Cir. 1970) . . . . 29, 30n, 31, 32n

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ................ 16n

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

419 F . 2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1 9 6 9 ) .................... lln

Sizzler Family Steak Houses v. Western Sizzlin Steak

Houses, Inc., 793 F.2d 1529 (11th Cir. 1986) . . 44n

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

- vi

Snell v. Suffolk County, 611 F. Supp. 521 (E.D.N.Y.

1 9 8 5 ) ............................................... 38n

Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 537 F.2d

800 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 6 ) ............................... 47

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1, 20-21 (1971) ......... 18, 29n, 31, 44, 48, 49

System Federation No. 91 v. Wright, 364 U.S. 642 (1961) 40n, 44

United States & Pittman v. Hattiesburg Municipal

Separate School District, 808 F.2d 385 (5th Cir.

1 9 8 7 ) ............................................... 46n

United States v. Board of Education of Waterbury, 605

F . 2d 573 (2d Cir. 1 9 7 9 ) .......................... 44n

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

District, 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir.), cert, denied,

395 U.S. 907 (1969)........................................ lln

United States v. Lawrence County School District, 799

F . 2d 1031 (5th Cir. 1 9 8 6 ) ........................ 44n

United States v. Louisiana, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) . . . 31

United States v. Missouri, 388 F. Supp. 1058 (E.D. Mo.),

modified on other grounds, 515 F.2d 1365 (8th Cir.),

cert, denied, 423 U.S. 951 (1975)................ 44n

United States v. Overton, 834 F.2d 1171 (5th Cir. 1987) 30n

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education,

407 U.S. 484 (1972).............................. 46n

United States v. Swift & Company, 286 U.S. 106, 119

( 1 9 3 2 ) ....................... 29, 30n, 31, 32, 42, 43

United States v. Swift & Company, 189 F. Supp. 885

(N.D. 111. 1960), aff'd per curiam, 367 U.S.

909 ( 1 9 6 1 ) ........... ............................ 32n

United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corporation, 391

U.S. 244 (1968)................................... 43n, 44n

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

- vii

United States v. Western Electric Company, Inc., 592

F. Supp. 846 (D.D.C. 1984), appeal dismissed,

777 F . 2d 23 (D.C. Cir. 1985) .................... 32n

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia, 407 U.S.

451 (1972) ........................................ 46n

Statutes and Court Rules:

28 U.S.C. § 1 2 9 1 ........................................ 1

28 U.S.C. § 1 3 3 1 ........................................ 1

28 U.S.C. § 1343 (a) ( 3 ) ................................. 1

28 U.S.C. § 1343 (a) ( 4 ) ................................. 1

Fed. R. App. P. 4 (a) (1) ............................... 1

Fed. R. Civ. P. 52 ...................................... 33n

10th Cir. R. 28.2(a).................................... i

10th Cir. R. 2 8 . 2(d)................................... 25n

10th Cir. R. 2 8 . 2(e).................................... 2

10th Cir. R. 2 8 . 2(g)................................... 2, 4n

Other Authorities:

Clark, Judicial Intervention, Busing and Local Resi

dential Change, in T. Herbert & R. Johnston, ed.,

Geography and the Urban Environment 254 (1984) . 37n

Clark, Residential Mobility and Neighborhood Change:

Some Implications for Racial Residential Segr

egation, 1 Urban Geography 95 (1980) ........... 38n

M. Danielson, The Politics of Exclusion (1976) . . . . 39n

R. Lake, The New Suburbanites: Race and Housing in the

Suburbs (1981) .................................... 39n

J. Levin & W. Levin, The Functions of Discrimination

and Prejudice 73 (2d ed. 1982) .................. 39n

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

- viii

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Other Authorities (continued):

Loewenberg, The Psychology of Racism, in G. Nash & R.

Weiss, eds., The Great Fear — Race in the Mind

of America (1970)................................. 39n

D. H. Nelson & W. Clark, The Los Angeles Metropolitan

Experience: Unigueness, Generality, and the Goal

of the Good Life (1976)........................... 37n

D. Pearce, Breaking Down Barriers: New Evidence on the

Impact of Metropolitan School Desegregation Housing

Patterns (1978) 34n

U.S. Department of Health, Education & Welfare/Office

for Civil Rights, Directory of Public Elementary

and Secondary Schools in Selected Districts:

Enrollment and Staff by Racial/Ethnic Group, Fall

1972 (1974)........................................ 12n

D. Wellman, Portraits of White Racism (1977) ......... 39n

Prior Appeals*

Dowell v. Board of Education of Oklahoma City, 795 F.2d

1516 (10th Cir.), cert, denied, 107 S. Ct. 486 (1986)

Dowell v. Board of Education of

(10th Cir. Jan. 28, 1975),

(1975)

Dowell v. Board of Education of

(10th Cir.), cert, denied,

Dowell v. Board of Education of

(10th Cir. 1970)

Dowell v. Board of Education of

(10th Cir.), cert, denied,

Oklahoma City, No. 74-1415

cert, denied, 423 U.S. 824

Oklahoma City , 465 F .2d 1012

409 U.S. 1041 (1972)

Oklahoma City , 430 F .2d 865

Oklahoma City , 375 F .2d 158

387 U.S. 931 (1967)

*See 10th Cir. R. 28.2(b)

In the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

No. 88-1067

ROBERT L. DOWELL, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

OKLAHOMA CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Preliminary Statement as to Jurisdiction

The district court had jurisdiction over this civil action

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331, 1343(a)(3) and (4) because it is a

suit arising under the Constitution and laws of the United States

brought to protect civil rights and to redress the deprivation of

constitutional rights. This Court's appellate jurisdiction is

provided by 28 U.S.C. § 1291. The judgment from which this appeal

is prosecuted was entered December 11, 1987 and the Notice of

Appeal was filed January 7, 1988, within the time limit provided

by Fed. R. App. P. 4(a)(1).

Issues on Appeal

1. Whether the district court properly carried out the remand

instructions of this Court on the prior appeal, 795 F.2d 1516 (10th

Cir. 1986)?

2. Whether the district court erred in concluding that a

school board which achieves "unitary status" under a continuing

desegregation decree is free to take action in contravention of

that decree regardless of the resegregative impact of that action,

as long as the board acts without discriminatory intent?

3. Whether the district court erred in concluding that all

vestiges of the prior dual system operated by the Oklahoma City

Schools have been eliminated and have no continuing effect under

the system's current student assignment plan?

4. Whether the Board of Education demonstrated that since

entry of the original desegregation decree, there have been legal

or factual changes which justify dissolving that decree because

the danger of recurrence of the unconstitutional condition which

the decree was intended to remedy has become "attenuated to a

shadow"?

5. Whether the district court erred in dissolving rather than

modifying the permanent injunction, and in dismissing the case?

6. Whether the district court erred in failing to modify its

prior order to require continued desegregation of the elementary

schools of Oklahoma City on an equitable basis?

[Pursuant to 10th Cir. R. 28.2(e), counsel state that each

of these issues was raised before the district court and is reflec

ted in the Final Pre-Trial Order of June 4, 1987. Each of these

issues was ruled upon by the district court in its Memorandum

Opinion of December 9, 1987, reprinted infra pp. la-56a pursuant

to 10th Cir. R. 28.2(g).]

2

Statement of the Case

Introduction

This case is about the continuing impact of long-maintained

policies of racial discrimination and segregation in the State of

Oklahoma and the public schools of Oklahoma City. Having succeed

ed, after more than a decade of litigation, in obtaining judicial

relief in 1972 that resulted in the elimination of segregated

public education from Oklahoma City, plaintiffs now seek to protect

those gains from a fresh assault — the abandonment of the 1972

plan in grades 1-4 and the substitution of a "neighborhood" assign

ment scheme which recreates many of the same segregated, virtually

all-black facilities to which black students were consigned prior

to 1972.

Procedural History

The extensive history of this case is described in the opinion

of this Court on the prior appeal (Dowell,1 795 F.2d 1516, 1517-

18 (10th Cir.), cert, denied. 107 S. Ct. 420 (1986)). The action

was originally commenced in 1961 seeking the elimination of state-

mandated and officially enforced public school segregation in Okla

homa City. A comprehensive desegregation decree, which succeeded

(while implemented) in eliminating racially identifiable public

schools, was entered in 1972 and affirmed by this Court (338 F.

Supp. 1256 (W.D. Okla.), aff'd. 465 F.2d 1012 (10th Cir.), cert,

denied. 409 U.S. 1041 (1972)).

-'-Citations to prior opinions in this case, see supra p. ix,

either refer to "Dowell" or omit the case name entirely.

3

In 1985 the school board abandoned the existing plan at the

elementary grade level and adopted a "neighborhood school" assign

ment plan. This change resulted in the operation of eleven elemen

tary schools2 with student enrollments in excess of 90% black (Mem.

Op. 3).3 Plaintiffs-appellants challenged the new plan, but in

1985 the district court sustained the school board's actions (see

506 F. Supp. 1548 (W.D. Okla. 1985), rev1d and remanded. 795 F.2d

1516 (10th Cir.), cert, denied. 107 S. Ct. 420 (1986)).

On plaintiffs' appeal, this Court reversed. It ruled that

because the 1972 injunctive decree had never been vacated, the

district court's 1977 finding of unitariness "does not preclude

plaintiffs from asserting that a continuing mandatory order is

not being obeyed and the consequences of the disobedience have

destroyed the unitariness previously achieved by the district"

(795 F . 2d at 1522 [emphasis supplied]), and that plaintiffs were

not required to prove discriminatory intent in order to enforce

the injunction fid, at 1519). The panel added that the district

court should examine whether the 1972 decree should be modified

because changed circumstances had produced "hardship so extreme

and unexpected as to make the decree oppressive" or that "the

dangers prevented by the injunction 'have become attenuated to a

2"Elementary schools" refers to schools serving grades K-4.

Separate "fifth-grade centers" in Oklahoma City are not currently

part of the "neighborhood plan."

3Citations in the form "Mem. Op. __" refer to the typewritten

Memorandum Opinion of the court below issued December 9, 1987,

reprinted in the appendix infra pp. la-56a pursuant to 10th Circuit

Rule 28.2(g).

4

Thus, this Court held that the standardshadow'" fid, at 1521).4

for judging any school board request for modification or dissolu

tion of the decree is hardship or efficacy in carrying out the

purposes of the decree, not the presence or absence of discrimina

tory intent underlying the request.

The matter was tried to the court below from June 15 to 24,

1987, pursuant to that remand. Following the submission of post

trial proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law by the par

ties, and oral argument, the district court released a Memorandum

Opinion (infra pp. la-56a) on December 9, 1987 and a judgment on

December 11, 1987 finfra p. 57a) dissolving the injunctive decree,

dismissing the action with prejudice, and taxing costs against

plaintiffs-appellants. In spite of the prior ruling of this Court,

the district judge relied heavily, to support this disposition,

upon his conclusion that the school board did not act with dis

criminatory intent (see infra pp. 19-20). This appeal followed.

Statement of Facts

A. Public School Desegregation in Oklahoma City

It should be remembered that Oklahoma was admitted into

the Union in 1907 as what is commonly known as a "Jim

Crow State," being an expression having to do with the

law that was common among southern states requiring the

separation of white and Negro people in public vehicles

and places of resort, and at all times since Statehood

40n this issue, the school board was to shoulder the burden

of proof: "The defendants, who essentially claim that the injunc

tion should be amended to accommodate neighborhood elementary

schools, must present evidence that changed conditions require

modification or that the facts or law no longer require enforcement

of the order" (795 F.2d at 1523).

5

the Oklahoma [City] School District was completely and

fully segregated.

(Dowell. 219 F. Supp. 427, 431 (W.D. Okla. 1963).) Separate public

schools for black and white students were mandated by provisions

of the Oklahoma Constitution (id. at 431-33) . Although state-

enforced segregation was declared unconstitutional in Brown v .

Board of Education. 347 U.S. 483 (1954), at the time of the initial

district court decision in this matter nine years later, there

was "no tangible evidence to show the defendants ha[d] made a good

faith effort to integrate the public schools of Oklahoma City"

beyond the passage of a resolution in 1955 recognizing the appli

cation of the Brown decision (219 F. Supp. at 434-35; see also

id. at 437-38, 442-43, 445-46 [overwhelming pattern of student

and faculty segregation in Oklahoma City public schools]).

After Brown. the school board established "neighborhood" boun

daries for school attendance purposes, which were superimposed

upon the pattern of residential segregation created by governmental

action and public policy (219 F. Supp. at 433-34 ; Mem. Op. 3),

and which resulted in the continued segregation of the public

schools (244 F. Supp. 971, 976 (W.D. Okla. 1965), aff'd in per

tinent part. 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir.), cert, denied. 387 U.S. 931

(1967)). In addition, the district court found that the board's

"neighborhood" attendance plan both exacerbated the level of resi

dential segregation and increased the number of segregated schools;

The Board's desegregation plan professes adherence to a

neighborhood school policy based on "logically consistent

geographical areas." But such a policy, when superim

posed over already existing residential segregation

6

initiated by law in Oklahoma City, leads inexorably to

continued school segregation. This result follows be

cause :

(b) integrated areas and schools are destroyed

because uncorrected racial restrictions in the housing

field enable whites to move to areas served by all white

or virtually all white schools, secure in the knowledge

that housing segregation and the neighborhood school

policy will not enable Negroes to follow them.

. . . The Integration Report concludes, and correctly

this Court holds, that inflexible adherence to the neigh

borhood school policy in making initial assignments

serves to maintain and extend school segregation by ex

tending areas of all Negro housing, destroying in the

process already integrated neighborhoods and thereby

increasing the number of segregated schools.

(244 F. Supp. at 976-77.) 5 The situation was unchanged in 1972

when the district court rejected an elementary school part-time

desegregation plan suggested by the school board, which it found

to have been designed "to protect the 'neighborhood schools' and

to keep desegregation on a voluntary basis" (338 F. Supp. at 1270;

see id. at 1265).6

Not until 1972 were the public schools of the district effec

tively desegregated, through a plan employing grade restructuring

and pupil transportation (the "Finger Plan") (see 795 F.2d at

5See also id. at 978: "Continuing racial discrimination in

housing and in economic opportunities, combined with still viable

public adherence to the standards of a segregated society, render

impossible meaningful school desegregation unless vigorous, affir

mative measures are undertaken by the School Board."

6See also 338 F. Supp. 1256, 1259-60 & n.3 (W.D. Okla.),

af f ' d . 465 F . 2d 1012 (10th Cir.), cert, denied. 409 U.S. 1041

(1972)(extent of continuing school segregation).

7

1518).7 These methods of student assignment, developed as part

of the Finger Plan, were maintained at all grade levels through

the 1984-85 school year (Mem. Op. 3).

B. Elementary School Researeaation

Effective for the 1985-86 school year, however, the Board

adopted a new student assignment proposal for elementary schools

which was once again based on "neighborhood" attendance zoning.8

7In 1977 the district court found — at a time when the plan

was still being implemented — that the Oklahoma City public

schools were being operated as a "unitary system:"

The Court has concluded that this [Finger Plan] was in

deed a plan that worked and that substantial compliance

with the constitutional requirements has been achieved.

The School Board, under the oversight of the Court, has

operated the Plan properly, and the Court does not fore

see that the termination of its jurisdiction will result

in the dismantlement of the Plan or any affirmative ac

tion by the defendant to undermine the unitary system

so slowly and painfully accomplished over the 16 years

during which the cause has been pending before-the Court.

. . . The Court believes that the present members and

their successors on the [School] Board will now and in

the future continue to follow the constitutional desegre

gation requirements.

. . . The Court believes and trusts that never again

will the Board become the instrument and defender of

racial discrimination so corrosive of the human spirit

and so plainly forbidden by the Constitution.

(Dowell v. Board of Education of the Oklahoma City Public Schools.

No. CIV-9452 (W.D. Okla. Jan. 18, 1977)). The district court dis

missed the action but "did not vacate or modify the 1972 order

mandating implementation of the Finger Plan" (795 F.2d at 1518).

8The elementary school zones under the 1985 plan are the same

as those used in 1971 and earlier, except for modifications neces

sitated over the years as individual facilities were closed (Mem.

Op. 34? Tr. 346 [former Board President Hermes]). In particular,

prior to the 1972-73 school year and after the 1984-85 school year,

the "northeast quadrant" or "central east" section of the "inner

8

Under this new plan, in contrast to the situation from 1972 to

1984 when all schools were integrated, during the 1985-86 and 1986-

87 school years eleven schools had student enrollments which were

more than 95% black, as shown in the following table, taken from

PI. Ex. 41; see Mem. Op. at 16 (1985-86 enrollments).9

% Black Enrollment**

School* 1984-85 1985-86 1986-87

Creston Hills 41.4 98.8 99.4

Dewey 33.5 97.1 97.9

Edwards 29.7 99.3 100.0

Garden Oaks 36.9 98.8 98.0

King 43.2 99.5 99.5

Lincoln 36.9 97.5 99.1

Longfellow 32.2 99.3 98.9

North Highland 46.5 96.3 97.6

Parker 72.3 97.3 97.0

Polk 31.6 97.7 99.5

Truman 27.6 99.3 99.7

*In the 1984-85 school year, each school housed a neighborhood

kindergarten and grade 5. In the 1985-86 and 1986-87 school years,

each school served grades K-4 as a neighborhood school.

**Percentages based on enrollment in grades other than kindergar

ten .

Under the Finger Plan, from the 1972-73 school year through

the 1984-85 year, none of these schools had approached this level

of segregation; indeed, with minor exceptions, none was even major

city" coincided precisely with a group of attendance zones for

elementary schools — each of which was more than 95% black in

student enrollment, both prior to the implementation of the Finger

Plan and once again after it had been abandoned. See PI. Ex. 5

(1968-72 attendance areas), 7 (map), 41 (table).

9Although the School Board closed seven elementary schools

at the end of the 1986-87 school year, no major shift in these

results was anticipated. Of the schools with more than 95% black

enrollments, Lincoln and Truman were closed while Dunbar, previ

ously shut, would be reopened and was projected to be a virtually

all-black facility. See PI. Ex. 28, Def. Ex. 62 (projections).

9

ity-black (see Pi. Ex. 41). On the other hand, all (except for

North Highland) had been operated as virtually all-black (more

than 95% black) schools prior to the entry of the 1972 decree (see

id. 1 . More than 40% of all black students in grades 1-4 attended

these virtually all-black schools in 1985-86 and 1986-87 (PI. Ex.

26, 27).10

After the new plan was adopted in 1985,.the pattern of faculty

assignments to elementary schools in the district also began to

change. Between the 1984-85 and 1986-87 school years, "the blacker

schools in enrollment became much blacker in percentage black fac

ulty, while in the schools with the least black enrollment, the

10In addition to the eleven virtually all-black schools listed

in the text, eighteen schools enrolled fewer than 10% black pupils

in grades 1-4 in the 1985-86 school year, when black students were

37% of the total student population in those grades (PI. Ex. 26).

(The figures shown at Mem. Op. 3 differ slightly because

they include kindergarten students, who had never been subject to

reassignment for desegregation purposes under the Finger Plan.)

The school board pointed out at the hearing that none of the

schools with fewer than 10% black pupils was more than 90% white.

However, none of the decisions in this case was predicated on a

claim or on evidence that school authorities deliberately segrega

ted other than black children; plaintiffs' expert witness found no

indication that the small number of other-race minority students

in Oklahoma City had ever previously been taken into account in

the student assignment process, and the school board had provided

figures only for "black" and "other" in response to interrogatory

requests for enrollment by race (Tr. 1353; PI. Ex. 11-27).

According to the only record evidence providing this informa

tion for an earlier school year, in 1982-83 only one elementary

school (Rancho Village, at 9.7% black), enrolled fewer than 10%

black students (Def. Ex. 208).

10

In 1986-faculty becomes less black" (Tr. 1270 [Dr. Foster])-11

87, of the ten elementary schools with the highest proportions

of black faculty, nine had student enrollments more than 90% black

(PI. Ex. 54) . 1 2 Comparison of faculty assignments for the eleven

elementary schools which were re-established as virtually all-black

facilities under the 1985 "neighborhood" plan with their staffing

during the initial and final year of implementation of the Finger

Plan is instructive:

11See Tr. 551 (Vern Moore [school board's Director of Person

nel Services]: "The majority of the staffs [in northeast quadrant

schools] were black")? PI. Ex. 48, 50, 52, 54.

12The district court found that these changes occurred be

cause, under the agreement negotiated by the school board with

the teachers' union after implementation of the 1985 elementary

school plan, "teachers with seniority had more discretion in selec

ting their teaching assignment" and "[w]here teachers lived, no

doubt, influenced their preferences about where they wished to

work." Mem. Op. 37. But see, e.a. . Mays v. Board of Public

Instruction of Sarasota County. 428 F.2d 809 (5th Cir. 1970); Uni

ted States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School District. 406

F.2d 1086 (5th Cir.), cert, denied. 395 U.S. 907 (1969).

The trial court ruled that the trend toward black schools

having largely black faculties was of no significance, citing

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board. 432 F.2d 875, 878-

79 (5th Cir. 1970); Lee v. Walker County School System. 594 F.2d

156, 159 (5th Cir. 1979); Lee v. Russell County Board of Education.

563 F .2d 1159, 1163 (5th Cir. 1977). All of these cases are inap

posite because they deal with faculty layoffs. see Carter. 432

F .2d at 878; Walker County. 594 F.2d at 158, 159; Russell County,

563 F . 2d at 1162-64, or failure to hire, see Russell County. 563

F . 2d at 1163-64, rather than assignment. Although "[t]he objective

criteria requirement of Singleton fv. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District. 419 F.2d 1211, 1218 (f 3) (5th Cir. 1969)] does

not apply . . . after a formerly segregated school system 'ha[s]

for several years operated as a unitary system,' " Walker County,

594 F .2d at 157-58, this is not true with respect to the require

ment that "principals, teachers, teacher-aides and other staff

who work directly with children at a school shall be so assigned

that in no case will the racial composition of a staff indicate

that a school is intended for Negro students or white students,"

419 F .2d at 1217-18. Cf. Columbus Board of Education v. Penick.

443 U.S. 449, 461 (1979); Davton Board of Education v. Brinkman.

443 U.S. 526, 535-36 & n.9, 539 & n.ll (1979).

11

% Black Faculty

School 1972-73 1984-85 1985-86 1986-87

Creston Hills 28 48 57 43

Dewey 21 15 48 42

Edwards 15 48 65 70

Garden Oaks 39 48 40 50

King 2413 30 26 43

Lincoln 21 55 49 64

Longfellow 20 16 31 38

North Highland 19 34 39 38

Parker 22 29 44 46

Polk 19 32 43 46

Truman 32 42 33 44

(PI. Ex. 48.)14

C. Justifications for the new plan

The 1985 student assignment plan for elementary pupils was a

marked departure from the Finger Plan and, as noted above, markedly

changed the racial composition of the district's elementary

schools. In accordance with the remand directions given by this

Court in 1986, the school board sought to establish that there

were changed circumstances providing legal justification for modi

fying the 1972 decree so as to authorize implementation of the

new plan.

13Prior to 1974-75, King was called Harmony Elementary School.

Although defendants provided no faculty information for Harmony

in response to plaintiffs' interrogatories, data provided by the

district to federal authorities indicate that in 1972-73, Harmony's

faculty was 24% black. U.S. Department of Health, Education &

Welfare/Office for Civil Rights, Directory of Public Elementary

and Secondary Schools in Selected Districts: Enrollment and Staff

by Racial/Ethnic Group, Fall 1972 1127 (1974)).

140n April 22, 1987, after plaintiffs pointed out the corre

lation between the race of students and that of faculty members,

the school board adopted a new policy limiting transfers among

schools by teachers.

12

The school board argued that "the primary factor motivating

its adoption of the new student assignment plan at the elementary

level" was "demographic change in Oklahoma City [which] rendered

the 'stand-alone' school feature in the Finger Plant15] inequitable

and oppressive" (Mem. Op. 23, 28). Both the plaintiffs and the

district court agreed that by 1985, two circumstances existed which

justified some alteration of the Finger Plan: (a) the burdens

of transportation in the lower grade levels were being borne dis-

proportionately by black pupils,16 and (b) creation of additional

"stand-alone" schools would increase that burden and might lead to

closing down existing facilities located in the "northeast quad

rant" or "east inner-city area"17 (Mem. Op. 25-28).

15This Court summarized the features of the Finger Plan in

its prior opinion, 795 F.2d at 1518.

16In the 1971-72 school year, when the Finger Plan was de

signed, black students were only 24% of the total elementary school

population in these grades (PI. Ex. 12). By virtue of the division

of grades among formerly black and white schools, black students

in grades 1-5 attended school without busing for one year (20%)

while white children in the same grades did so for four years

(80%). By the 1984-85 year, the black proportion of elementary

students had risen to 36% (PI. Ex. 25), but schools in black neigh

borhoods still housed only one of five grades (20%). The school

board never sought to add an additional grade to schools in black

neighborhoods, although this was suggested by the system's research

staff (Tr. 498-99; Def. Ex. 72); one of the school board's expert

witnesses testified that this would have maintained integration

with the minimum amount of busing (Tr. 292-93 [Welch]).

17In 1984 the school system's staff identified 13 attendance

areas which qualified under the standard of the Finger Plan for

K-5 "stand-alone" status (Def. Ex. 72). Had all of these schools

been changed to "stand-alone" status, pupils from black neighbor

hoods, already bused a disproportionate number of years in grades

1-5 (see supra note 16) would have had also to be transported

longer distances than when the Finger Plan was first implemented:

13

In addition, the school board suggested that there had been

substantial change in the demography of Oklahoma City. It argued

that current residential patterns no longer reflected the influence

of the prior governmental restrictions and pervasive private dis

crimination which — aggravated by the school system's resistance

to carrying out the mandate of Brown — had created the severe,

interrelated housing and school segregation which the Finger Plan

was intended to neutralize.18

The board's evidence demonstrated that Oklahoma City's black

population was no longer as concentrated in as small an area within

the "northeast quadrant" of the city as had been true in 1960 (Mem.

In the 1972-73 school year, there were eleven "stand-alone"

schools in the main geographic area of the system (Tr. 289 [Welch];

PI. Ex. 6, 8, 13). Four (Columbus, Ross, Shidler, Stand Watie)

were located south of the Canadian River, five (Edgemere, Horace

Mann, Mark Twain, Orchard Park, Riverside) were located north of

the river in the central portion of the area, and two (Nichols

Hills, North Highland) were in the northern portion of the area.

See PI. Ex. 3.

In 1984 the areas which qualified for "stand-alone" status

were less widely dispersed and formed a virtual band across the

middle of the area. Two (Bodine, Rockwood) were located south of

the Canadian River; six (Edgemere, Eugene Field, Gatewood, Horace

Mann, Putnam Heights, Wilson) were located north of the river

adjacent to the "northeast quadrant"; two (Britton — which now

included the former Nichols Hills and Lone Star areas — and Wes

tern Village) were north of the river in the northern portion of

the district's main geographic area. See PI. Ex. 3.

In addition, reassigning white fifth grade students from

northeast quadrant schools to these eleven facilities would likely

have lowered enrollments in the northeast quadrant schools to such

a degree that the board would have had to close facilities in the

black neighborhoods (Mem. Op. 25-26).

18See Pre-Trial. Order, Defendants' Contentions, at 5.

14

Op. 7, 9);19 that unlike the situation in 1972, by 1986 black

pupils in at least small numbers resided within every school at

tendance area in the district (Mem. Op. 10; see Def. Ex. 13).

However, the northeast quadrant remained very heavily black

throughout the period (Mem. Op. 5, 21; Tr. 66 [Clark], 1129-31

[Rabin]; see Def. Ex. 1-4, 12-13).20 The board's expert witness,

Dr. William Clark, testified that whites simply will not move into

areas that have been established as minority residential zones by

discriminatory policies and practices (Tr. 106-07),21 and the

l^The district court noted that the population of the few

census tracts which in 1960 had housed the vast majority of Okla

homa City blacks had decreased substantially by 1980 (Mem. Op. 8-

9). The expert witnesses for both the school board and the plain

tiffs agreed that significant highway construction and urban renew

al in the area forced the population to relocate, and that the

black population of adjacent census tracts increased over the

period (Tr. 68 [Clark]; 1154, 1158, 1162 [Rabin]). The availa

bility of public housing outside the northeast quadrant in the

1970's was also a factor in the relocation of blacks outside the

area (Tr. 60, 77 [Clark]).

20The district court suggested (Mem. Op. 19 n.4) that there

are a number of attractive "recreational facilities and cultural

sites" within the northeast quadrant which account for the fact

"that many blacks have chosen to remain" there. There is abso

lutely no record evidence on the matters discussed by the court,

much less evidence that the existence of such facilities was a

factor in determining black residential patterns. The court's

remarks are pure speculation.

21Another board witness, Dr. Welch, utilized a computer pro

gram to project levels of residential and school integration in

Oklahoma City in 1995 (Mem. Op. 10; Tr. 229-55) . Dr. Welch reached

the conclusion, diametrically opposite to that of Dr. Clark, and

contrary to the experience of the last four decades in Oklahoma

City, that white families with school-age children would move into

presently all-black areas of the northeast quadrant (compare Tr.

252-53 [Welch] with Tr. 106-07 [Clark]).

15

Never-experience of Oklahoma City bears out this observation.22

theless, it was Dr. Clark's opinion that neither past nor present

discrimination is a substantial factor affecting the current demo

graphic patterns in the United States, and that this conclusion

is applicable to Oklahoma City (Tr. 89, 100).23 In his view, the

22There has been no significant movement of white residents

into the area of Oklahoma City into which blacks were originally

concentrated; rather, that area has expanded in population and

geographic size but remained almost totally black (Tr. 45, 93-94

[Clark], 388-89 [Hermes], 1127-31 [Rabin]; Def. Ex. 1-4, 5A, 12-

13; PI. Ex. 58, 60, 62).

23Dr. Clark does not believe that the admittedly discrimina

tory practices of the past significantly affected residential pat

terns. For example, he guestioned the effectiveness of restrictive

covenants, which had been widely and rigidly enforced in Oklahoma

City (see 219 F. Supp. at 433-34; 244 F. Supp. at 975), although

he had conducted no historical study of conditions in the city

(Tr. 95-96) and was unaware of state court enforcement of the

covenants by cancelling deeds executed in favor of black purchasers

or renters by willing sellers [see, e .q .. Hemslev v. Hough. 157

P.2d 182 (Okla. 1945); Hemslev v. Sage. 154 P.2d 577 (Okla. 1944);

Lyons v. Wallen. 133 P.2d 555 (Okla. 1941)] (Tr. 98).

Dr. Clark pointed to the decision in Correll v. Easley. 237

P.2d 1017 (Okla. 1951), in which the Oklahoma Supreme Court fol

lowed Shelley v. Kraemer. 334 U.S. 1 (1948) and refused to cancel

such a deed, as "very important in changing the [segregated] pat

terns — of allowing the patterns to change" (Tr. 89) . He was

unaware that in the same decision, the Oklahoma Supreme Court sus

tained an award of damages against the white seller for violating

the restrictive covenant (237 P.2d at 1021) and he had not con

sidered whether such damages awards made property owners reluctant

to make sales in violation of the covenants (Tr. 99-100).

According to Dr. Clark, even the impacted concentration of

blacks in a few census tracts in Oklahoma City in 1950 was attrib

utable, in large measure, to nondiscriminatory factors such as

the availability of jobs in the downtown area, preferences of

blacks to live near other blacks, the information network among

blacks available to those seeking to relocate, and the availability

of cheaper housing in the area "having been vacated by other fami

lies who had moved out" (Tr. 45-46). This conclusion is directly

contrary to the district court's finding in 1963 that the segrega

16

principal causes of current racial stratification in housing are

(1) economics (the lower incomes and assets of black families),24 25

(2) preference (including both the desire of all groups to main

tain social relationships with like individuals and the strong

white antipathy to residing in black neighborhoods), (3) urban

structure (the observed tendency of city dwellers to relocate

through short-distance moves), and (4) some small residue of cur

rent private discrimination2 ̂ (Tr. 83-88; see Def. Ex. 10).

ted residential pattern was "set by law for a period in excess of

fifty years" (219 F. Supp. at 433) .

Finally, although he was aware of the Federal Housing Admin

istration's (FHA's) discriminatory practices prior to 1949 which,

he admitted, "did not encourage the movement into — well, black

households into white neighborhoods" (Tr. 110), he did not know

whether these practices continued after 1949 and he could not

estimate the extent to which FHA financing contributed to the

pattern of white suburbanization in the United States (id. at 107-

11) . Compare, e.q.. Bradley v. School Board of Richmond. 338 F.

Supp. 67, 217 (E.D. Va.), rev'd on other grounds. 462 F.2d 1058

(4th Cir. 1972), aff'd bv equally divided court, 412 U.S. 92

(1973)("Policies fixed during the initial years of the FHA spread

and have endured to have a substantial effect on the current hous

ing market practices").

24Although Dr. Clark recognized that there are still very

large wealth differentials between black and white families, he

stated that any determination of the relationship between prior

discrimination against black people in the United States and their

current economic status is beyond his area of expertise (Tr. 84,

107, 114).

25Dr. Clark believes that most private discrimination in the

housing market was discouraged and eliminated by the passage of

the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and similar legislation (Tr. 84-85,

88; but see Tr. 113-14). The Executive Director of the Metropoli

tan Fair Housing Council of Greater Oklahoma City testified that

"steering continues to determine where people live, where people

buy homes" (Tr. 1166, 1171-72).

17

albeit more subtle than in the past, continues to exist in Oklahoma

City (Tr. 312-15 [Biscoe], 1168, 1170-72, 1177-78 [Silovsky]), and

that current demographic patterns are directly related to prior

discrimination (Tr. 1172-73). Unlike Dr. Clark, plaintiffs' expert

witness Dr. Marylee Taylor has considered the link between past

discriminatory practices, especially on the part of governmental

agencies, and the factors which Dr. Clark suggested explain current

residential separation of the races:

Doctor Clark and I agree that economic resources and

preferences are important influences on residential deci

sions. They're factors that help to explain why there

has not been a complete exodus from the black residential

community here.

Where Doctor Clark and I disagree is in our view of the

genesis of the economic and — economic factors and pref

erences. He sees them, as I understand him, as inciden

tal individual matters, and I think this view suffers

from taking — from having a limited perspective on the

'■ impact of discrimination over time.

In fact, I think that economic resources and preferences

are proximate causes of residential segregation, but

they are also effects of past officially-produced resi

dential segregation. In that sense, they're intervening

links. They help to explain why the black residential

area, once it was created through official segregation,

continues to exist even in the absence of continuing

official action.

(Tr. 1229; see also, e. g. . id. at 1226-28, 1236; cf. Swann v. Char-

lotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education. 402 U.S. 1, 20-21 (1971).)

Plaintiffs elicited testimony that housing discrimination,

D. The district court's ruling

The district court not only agreed that the 1972 decree could

be modified so as to permit the school board to implement its

"neighborhood" plan in grades 1-4, but it also dissolved the entire

18

injunction and dismissed the case. In reaching this result, the

trial court did not track the analysis of the 1986 panel decision

but progressed through its opinion as follows:

The court concluded, first, that demographic patterns within

Oklahoma City today are not attributable to any degree to actions

taken by the school board since 1963 (Mem. Op. at 21) because

discriminatory statutes, ordinances and housing market devices

have been outlawed and replaced by fair housing legislation; blacks

and whites in the city today reside where they freely choose ( id.

at 18) . Thus, the court decided, any school segregation which

accompanied the institution of the board's 1985 "neighborhood"

plan has only a most attenuated connection with its past segrega

tive acts and does not violate the Constitution (id. at 22-23).26

The court next examined whether the school system had

"retained unitary status" after implementing the K-4 "neighborhood"

plan (id. at 29). While it complied with this Court's remand

instructions to place the burden of proof upon the school board

(see supra note 4), it overlooked the panel's recognition that

plaintiffs would be entitled to relief if the consequence of adopt

ing the 1985 "neighborhood" plan was to "destro[y] the unitariness

previously achieved by the district" (795 F.2d at 1522). Instead,

26Compare 795 F.2d at 1523 ("The plaintiffs were required

not only to prove the mandatory injunction had been violated, but

also that the violation contravened the constitution. In the

framework of this case, the latter element was beyond the scope

of the hearing and certainly never the plaintiffs' burden").

19

the school board would prevail:

At trial, the Oklahoma City Board of Education carried

the burden of proof; this court concludes that the Board

proved by a preponderance of the evidence that its new

student assignment plan was adopted without the intent

to discriminate on the basis of race.

(Mem. Op. 31).27

the court insisted that unless discriminatory intent were found,

27The district court's focus on the need to find "discrimin

atory intent" as a basis for retaining the protections of the 1972

decree is evident in many statements or findings which run through

out the opinion. For example:

a. "[Sjubsequent to the achievement of unitary

status, the de facto/de jure distinction mandates a

search for discriminatory intent before governmental

action may be declared unconstitutional" (id. at 30).

b. "[M]any of the schools which were predominately

black before the Finger Plan was implemented are predom

inately black today as a result of the neighborhood plan.

. . . In sum, the only evidence which could support the

notion that the Board adopted the plan with discrimina

tory intent is the fact that the plan did have a dispro

portionate impact upon some blacks in the district" (id.

at 34) .

c. The post-1985 imbalances in faculty assignment

among elementary schools "were not motivated by discrim

inatory purposes" (id. at 37-38).

d. "At the hearing, a substantial number of black

school administrators and black patrons unequivocally

testified that in their opinion the Board's K-4 neigh

borhood school plan was not discriminatory and did not

result in the recreation of a dual school system" (id.

at 38).

e. The presence of black employees on the central

staff of the system "will serve to deter racially dis

criminatory actions or any attempt to return to the dual

system" (id. at 40).

f. "This court's 1977 unitary finding signifies that

the Oklahoma City Board of Education had satisfied its

affirmative duty to desegregate by eliminating the dual

school system. Since the Board had dismantled its dual

20

Although the court recognized the agreement of both parties

that increasing inequity in the distribution of burdens under the

Finger Plan warranted a modification of the 197 2 decree (id. at

28, 46), it rejected plaintiffs' proposal for a plan which would

continue desegregation while alleviating the inequity28 in favor

of dissolving the injunction completely, thus leaving the school

board free not only to continue its 1985 "neighborhood" elementary

school plan but also to dismantle the remaining portions of the

Finger Plan at any time.

system at the time it adopted its neighborhood plan,

effect does not govern over purpose as plaintiffs sug

gest" (id. at 49).

28The court rejected the plan drafted by plaintiffs' expert

witness Dr. Gordon Foster to illustrate the feasibility of pre

serving integrated elementary schools with a fairer distribution

of burdens because it viewed such a plan as granting "additional

relief" to which this Court had said plaintiffs were not entitled,

see 795 F.2d at 1522, anticipated additional "white flight" from

the district if such a plan were implemented, and believed the

plan was too costly (Mem. Op. 53-55).

21

ARGUMENT

Introduction and Summary

If the ruling below is permitted to stand, then the long ef

fort to achieve meaningful school desegregation in Oklahoma City

— which consumed eleven years between the filing in 1961 of liti

gation to enforce the Brown decision and the 1972 decree requiring

implementation of an effective and comprehensive plan that assigned

students to integrated schools — will prove to have been a pyrrhic

effort. Barely more than a single twelve-grade generation of Okla

homa City schoolchildren will have attended a system of desegre

gated schools before the district, with the sanction of the court

below, returned (thus far, in grades 1-4 only) to the same mechan

ism of pupil assignment utilized prior to 1972.

In 1972, those pupil assignments produced segregated, all

black schools in the "northeast quadrant" of Oklahoma City whose

continued existence violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States. In 1988 those same schools—

unless they have been shut down — are again being operated as all

black schools. Yet the court below held that Oklahoma City school

officials had completely satisfied their affirmative constitutional

obligation to disestablish all vestiges of the dual biracial school

system which they had operated for well over half a century. And

the court below approved the return to pre-1972 pupil assignment

techniques in the elementary grades because it found no "discrimin

atory intent." It is logically and legally absurd to suggest that

22

a school system which becomes "unitary" — corrects its past con

stitutional violations through the adoption and maintenance of a

particular student assignment scheme — may thereafter abandon or

dismantle that assignment scheme and restore segregated, one-race

schools without again violating the Constitution. As this Court

held in 1986, the attainment of "unitary status," without more,

cannot justify a return to the segregation of the past.

Readoption of pre-1972 assignments and the reestablishment

of historically segregated black schools can be justified, if at

all, this Court held, only by a showing, consistent with well-set

tled legal principles, that a change in the law or the facts jus

tifies modification of the 1972 injunctive requirements. While

the trial court was satisfied that these standards had been met,

its conclusion is insupportable on the record and makes a mockery

of the solemn requirements of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In 1963 and 1965 the district court made specific findings

concerning residential segregation in Oklahoma City. It summarized

a long pattern of deliberately discriminatory governmental actions

which identified the "northeast quadrant" as intended for black

individuals and families (including city ordinances, state-enforced

restrictive covenants, etc.) In addition, the court observed that

school authorities' practices after Brown had further entrenched

and exacerbated the segregated residential patterns established

by these governmental policies. It is clear beyond peradventure

that the residential segregation existing in 1972 was attributable

in substantial measure to official policy and practice.

23

The school board's own expert witness testified below, without

contradiction, that white individuals and white families simply

will not, of their own volition, move into an established predomi

nately black area, so that once created as a black residential

zone, the area will remain predominantly black. The defendants'

own evidence establishes, therefore, that the present segregated,

heavily black character of the "northeast quadrant" is the direct

consequence of the officially sanctioned establishment of the area

for black housing in the past. The fact that some black families

can now move into formerly white sections of Oklahoma City is

wholly inadequate to satisfy the school authorities' legal liabil

ity for the reimposition of "neighborhood" all-black schools in

the "northeast quadrant."

The inequitable burdens placed upon black children under the

1972 decree, and the aggravation of those inequities as demographic

patterns in the city changed, are valid concerns but also cannot

justify returning to the segregation of the past. Rather than

abandoning desegregation entirely, the school board could and

should have modified the Finger Plan, subject to the approval of

the district court, to make it fair. It did not do so because it

argued, and the district court agreed, ironically, that a plan

which more evenly distributed the burdens by transporting both

black and white pupils in grades 1-4 (rather than only black pu

pils) would not be equitable. The adoption of this rationale by

the court below is an affront to the principles of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

24

This case is not, as the school board contended below, an

effort to alter demographic patterns in Oklahoma City through a

school desegregation plan. Plaintiffs' position is that school

desegregation is required because the effects of the long-main

tained dual school system in Oklahoma City persist. Nor is it a

case in which plaintiffs seek to require the school authorities

to make changes in student assignments to account for post-1972

demographic shifts. It is a case about whether the important ef

fort to eliminate the scourge of official racism from our society,

which was symbolized by the Brown decision in 1954, is now to be

abandoned. This Court must hold defendant school officials to

the task imposed upon them by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution and keep open to black schoolchildren in Oklahoma City

the promise of equal educational opportunities, without discrimi

nation or segregation.

I

The District Court Failed To Give Effect To

This Court's Remand Directions In 1986 And

Erred As A Matter Of Law In Requiring A New

_____ Showing Of Discriminatory Intent______29

In 1985 the court below first sustained the Oklahoma City

school board's "neighborhood" plan in grades 1-4, despite the reap

pearance, under the plan, of ten virtually all-black schools (whose

29The standard of review on this issue, see 10th Cir. R.

28.2(d), is plenary since appellants contend that the district

court erred as a matter of law.

25

racial identities had been fixed by discriminatory action) that

the 1972 decree was designed to uproot. The trial judge based

his ruling on two factors: first, the court in 1977 had found

that, while enforced, the earlier decree had achieved a "unitary

system"; and second, plaintiffs had failed to show that adoption

of the new plan was motivated by discriminatory intent. See 795

F .2d at 1518-19.

This Court reversed and remanded for further proceedings.

It instructed that the plaintiffs "only have the burden of showing

the court's mandatory order has been violated," and that the dis

trict court had erred in requiring a showing "not only [that] the

mandatory injunction had been violated, but also that the violation

contravened the constitution" (795 F.2d at 1523).

The panel specifically rejected the notion that the achieve

ment of "unitary status," at a time when the injunction was being

obeyed, in and of itself removed either the district court's auth

ority to mandate continued enforcement of the decree, or the

grounds for the exercise of that authority:

According to the government, the defendants could not

be compelled to follow the Finger Plan once the court

determined the district was unitary. We find the con

tention without merit. The parties cannot be thrust

back to the proverbial first square just because the

court previously ceased active supervision over the oper

ation of the Finger Plan. . . .

The government's position ignores the fact that the pur

pose of court-ordered school integration is not only to

achieve, but also to maintain, a unitary school system.

(795 F.2d at 1520 [emphasis in original].) This Court also made

26

it clear that when it is alleged that a school board, against which

a desegregation decree was entered, has acted by changing the

method of pupil assignment in a manner which appears to restore

the school segregation originally held to violate the Constitution,

the right to continued enforcement of the decree does not depend

upon a new showing of discriminatory intent:

Here, the plaintiffs do not seek the continuous inter

vention of the federal court decried by the Supreme

Court. We are not faced with an attempt to achieve fur

ther desegregation based upon minor demographic changes

not "chargeable" to the board. Spangler. 427 U.S. at

435, 96 S. Ct. at 2704. Rather, here the allegation is

that the defendants have intentionally abandoned a plan

which achieved unitariness and substituted one which

appears to have the same segregative effect as the atten

dance plan which generated the original lawsuit.

Given the sensitive nature of school desegregation liti

gation and the peculiar matrix in which such cases exist,

we are cognizant that minor shifts in demographics or

minor changes in other circumstances which are not the

result of an intentional and racially motivated scheme

to avoid the consequences of a mandatory injunction can

not be the basis of judicial action. See Spangler. 427

U.S. at 434-35, 96 S. Ct. at 2703-04; Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education. 402 U.S. 1, 91 St. Ct.

1267, 28 L. Ed. 2d 554 (1971). However, when it is as

serted that a school board under the duty imposed by a

mandatory order has adopted a new attendance plan that

is significantly different from the plan approved by

the court and when the results of the adoption of that

new plan indicate a resurgence of segregation, the court

is duty bound either to enforce its order or inquire

whether a change of conditions consistent with the test

posed in Jan-dal has occurred.

(Id. at 1522 [emphasis in original].)

We had thought this Court's opinion quite clear. However,

the district court on remand has reached the same result it did

in 1985 and has justified it for the same reasons — simply placing

them in a new framework. Instead of advancing the 1977 finding

27

of "unitary status" as an independent ground for allowing the re

segregation of the Oklahoma City elementary schools, the court

now identifies this holding as a post-decree change in circumstan

ces which warrants dissolution of the injunction.30 Instead of

considering whether the new plan has "the same segregative effect

as the attendance plan which generated the original lawsuit," the

court holds that it should not enforce the 1972 decree unless the

K-4 plan was discriminatorily motivated.31 (See supra pp. 19-2 0*.)

30The district court said:

With an understanding of the conditions presently exist

ing in Oklahoma City, the court now shifts its attention

to the fundamental issue on remand: Should the 1972

desegregation decree be enforced, modified or dissolved?

. . . The Oklahoma City School District dismantled the

dual system and met th[e] objective [of the litigation]

in 1977, when it was declared unitary. Accordingly,

perpetuation of the 1972 decree no longer serves the

objective of this case.

(Mem. Op. 40, 43 [emphasis supplied].)

3-'-The district court stated:

Plaintiffs point out that many of the schools which

were predominately black before the Finger Plan was im

plemented are predominately black today as a result of

the neighborhood plan. Plaintiffs make much of the point

that when the Board adopted the new plan, they incor

porated the same neighborhood attendance zones that were

used prior to the time the Finger Plan was implemented.

However, . . . the Board never gerrymandered the geo

graphic composition of its attendance zones . . . . In

sum, the only evidence which could support the notion

that the Board adopted the plan with discriminatory in

tent is the fact that the plan did have a disproportion

ate impact upon some blacks in the district. . . . It

follows that a school board serving a unitary school

system is free to adopt a neighborhood school plan so

long as it does not act with discriminatory intent.

(Mem. Op. 34-35.) This same position was rejected by this Court

in 1986 (see 795 F.2d at 1520).

28

Unfortunately, the trial court has once again misapplied the gov

erning legal principles enunciated by this Court and its judgment

must be again reversed.

In Securities and Exchange Commission v. Jan-dal Oil & Gas,

Inc. . 433 F.2d 304 (10th Cir. 1970), this Court established the

appropriate standard for modifying or dissolving injunctions:

the party seeking to relax the requirements of the decree must

show that the law or the underlying facts have so changed that

the dangers prevented by the injunction "'have become attenuated

to a shadow'" (id. at 305, quoting United States v. Swift & Com

pany . 286 U.S. 106, 119 (1932)). This standard was explicitly

adopted for application to school desegregation decrees in the

1986 ruling in this litigation (795 F.2d at 1522), consistent with

the Supreme Court's admonition in Brown v. Board of Education.

349 U.S. 294, 299-300 (1955)(Brown II) that traditional equitable

principles would apply in desegregation suits.32

It is entirely inconsistent with Jan-dal to hold that the

very effectiveness of a desegregation decree — its success in

eliminating the racially identifiable attendance patterns which

characterized the dual system and in creating a "unitary" school

system — is a change in circumstances that should lead a court to

32As the Supreme Court reiterated in Swann, 402 U.S. at 15-

16, "a school desegregation case does not differ fundamentally

from other cases involving the framing of equitable remedies to

repair the denial of a constitutional right."

29

dissolve the injunction itself.33 A school system which becomes

"unitary" by effectuating a court-ordered plan for integrating

schools is like a heart patient who becomes "healthy" by having a

pacemaker implanted. Just as the patient who is healthy so long

as the pacemaker functions becomes sick when it is removed (unless

the heart problem has been cured by some other means in the in

terim) , a school system that is "unitary" because of an affirmative

desegregation plan employing particular means to insure school

integration will become "dual" again when it deliberately recon

stitutes a substantial number of its one-race schools by reinsti

tuting the previous method of school assignments.34

33In Jan-dal. the same district judge who has dismissed this

suit ruled that in light of the defendants' compliance with the

permanent injunction and the operation of "their securities busi

ness in affirmative compliance with S.E.C. requirements .

reasons for imposing the original injunction no longer existed"

(433 F.2d at 305). This Court held that such circumstances did

not meet the Swift standard.

34As this Court noted when the case was last here, "the Fourth

Circuit has taken a different view with which [this Court] cannot

agree" (795 F.2d at 1520, citing Riddick v. School Board of Nor

folk. 784 F.2d 521 (4th Cir.), cert, denied. 107 S. Ct. 420

(1986)). See also United States v. Overton, 834 F.2d 1171, 1174-

77 (5th Cir. 1987)(dictum).

In Morgan v. Nucci. 831 F.2d 313 (1st Cir. 1987), the Court

of Appeals vacated an order which directed "the school defendants

. . . for an indefinite period to maintain specific racial mixes

in the city's schools" f id. at 317); see Pasadena City Board of

Education v. Spangler. 427 U.S. 424 (1976). The First Circuit

found explicitly that the order could not be justified on instru

mental grounds — as a temporary race-based mechanism to undo the

vestiges of the prior dual system — since the school board's com

pliance with earlier orders (which had been sustained on appeal)

"ha[s] made the schools as desegregated as possible given the real

ities of modern urban life" (id. at 326) . However, the Court of

Appeals in Morgan was not confronted with the question whether

the school authorities could dismantle the previous desegregative

plan which they had implemented pursuant to court direction. That

plan was still in place.

30

Moreover, such an approach trivializes the constitutional

right enforced in school desegregation litigation by making relief

necessarily transitory.35 School districts that operated racially

separate facilities are not only forbidden through "future school

construction and abandonment . . . to perpetuate or re-establish

the dual system," Swann. 402 U.S. at 21, but may not allow "pupil

assignment policies" to have this effect either. Dayton Board of

Education v. Brinkman. 443 U.S. 526, 538 (1979) . In desegregation

cases, as in other constitutional litigation, the remedy is shaped

to "so far as possible eliminate the discriminatory effects of

the past as well as bar like discrimination in the future." United

States v. Louisiana. 380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965)(emphasis supplied).

This Court was therefore exactly right in distinguishing between

"minor shifts in demographics or minor changes in other circum