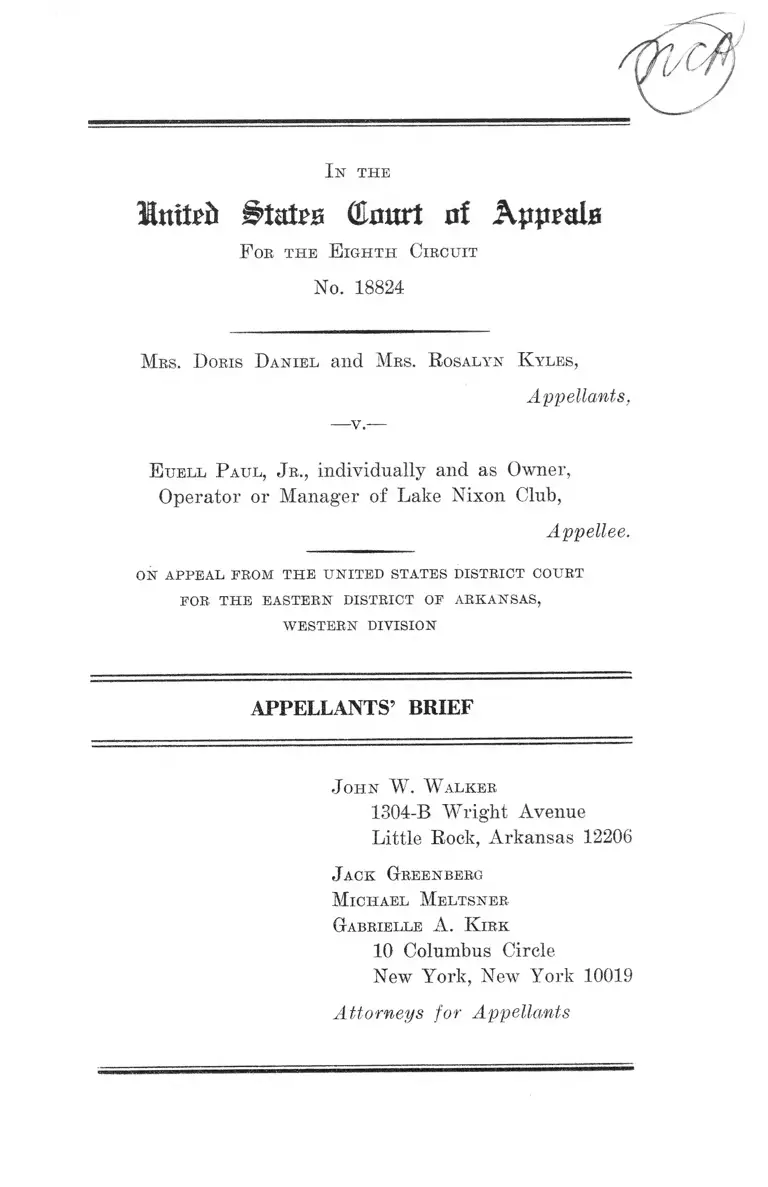

Daniel v. Paul Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

June 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Daniel v. Paul Appellants' Brief, 1967. 462df2eb-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b15d996c-d177-4bf6-8a24-cacd27f4b13d/daniel-v-paul-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

lotted States (Emtrt of Appeals

F ob the E ighth Circuit

No. 18824

Mbs. Doris Daniel and Mrs. Rosalyn Ivyles,

Appellants,

Ettell Paul, Jr., individually and as Owner,

Operator or Manager of Lake Nixon Club,

Appellee.

ON A PPE A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E EA STE R N D ISTRICT OF ARK AN SAS,

W ESTE R N DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

John W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas 12206

Jack Greenberg

M ichael Meltsner

Gabrielle A. K irk

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement .............................................................................. 1

Statement of Points to Be Argued .......... .................... 5

A rgument-—

I. Lake Nixon Is an Establishment Covered by

Section 201(b)(4) (42 TT.S.C. §2000a(b) (4)) of

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ............. 8

A. The snack bar at Lake Nixon is a facility

principally engaged in selling food for con

sumption on the premises within the mean

ing of Sections 201(b)(2) and 201(c)(2) (42

U.S.C. §§2000a(b) (2) and (c )(2 )) of Title II 8

B. The snack bar is located within the premises

of Lake Nixon, therefore, the whole of Lake

Nixon is a covered establishment ...... ............ 10

II. Lake Nixon Is a “Place of Entertainment”

Whose Operations Affect Commerce Within the

Meaning of Sections 201(b)(3) and 201(c)(3)

(42 TT.S.C. §§2000a(b) (3) and (c) (3)) of Title II

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ........................... 14

A. The dichotomy between spectator and par

ticipative activity is unrealistic and not sup

ported by the legislative history of Title II

or by the case law with respect to the cov

erage of state public accommodations laws .... 14

B. The operations of Lake Nixon affect com

merce within the meaning of Section 201-

(c)(3 ) of Title II .............................................. 19

Conclusion ................................................................... 22

Certificate of Service .......................................................... 23

PAGE

T able of Cases

A.B.T. Sightseeing Tours, Inc. v. Gray Line, 242 F.

Supp. 365 (S.D. X.Y. 1965) .............. .......... ............. 6,

Amos v. Prom, Inc., 117 F.Supp. 615 (N.D. Iowa

1954) ................ .. .......... ................................... ................ 6,

Central Amusement Company v. District of Columbia,

121 A.2d 865 (Mun. Ct. App. D.C. 1956) ...................6,

Dilworth v. Riner, 343 F.2d 226 (5th Cir. 1965) .........6,

Evans v. Laurel Links, Inc., 216 F.Supp. 474 (E.D.

Va. 1966) . 5,9,

Fraser v. Robin Dee Day Camp, 44 N.J. 480 (1965) ....

City of Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808 ...............6,

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 ...........5, 6,10,

Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294 ...........................5,

Lambert v. Mandel’s of California, 156 Cal. App. Rep.

2d 855 (1957) .................................... ..............................6,

McClung v. Katzenbach, 233 F.Supp. 815 (N.D. Ala.

1964), rov'd. 379 U.S. 294 .................. .............. ............. 6,

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 239 F.Supp.

323 (E.D. La. 1967) .................................. 6,

Pinkney v. Meloy, 241 F.Supp. 943 (M.D. Fla. 1965) ....5,

Rachel v. Georgia, 384 U.S. 780 .........................................6,

Robertson v. Johnston, 249 F.Supp. 618 (E.D. La.

1966) ............................... 6,

20

18

18

17

13

6

17

17

21

17

17

14

11

17

14

Ill

Stiska v. City of Chicago, 405 111. 374 (1950) ............... 6,18

Twitty v. Vogue Theatre Corp., 242 F.Supp. 281 (M.D.

Fla. 1965) .......................................................................... 6

United States v. Alabama, 304 F.2d 583 (5th Cir. 1962),

371 U.S. 37 .................................-.............. -.................... 7,17

United States v. Sullivan, 332 U.S. 689 ...........................7,20

Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U.S. I l l .................-.......... ..... 7,21

PAGE

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. §§1343(3) and 1343(4) .

42 U.S.C. §§2000a et seq. .................... 3, 5

42 U.S.C. §2000a(b) (2) ... ........................ 5,8

42 U.S.C. §2000a(b)(3) ... ............................. 6, 7,14

42 U.S.C. §2000a(b)(4) ... .................... 5, 8

42 U.S.C. §2000a(c)(2) ... ...... ...... 5,8

42 U.S.C. §2000a(c) (3) ... .....................6, 7,14,19

Civil Rights Act of 1957 . ................ 17

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title II :

<201(b) ........................

§201(b ) (2) ..................

§201 (b) (3) ............. ..

§201(b) (4) ..............

§201(c)(2 ) .................

§201(c ) (3) .................

................... 8

........... 13

.............4, 6, 8, 9,10,14,15,17,19

................4, 5, 8,10,11,12,13

....................8,10

............6,14,17,19, 20

Alaska Stat., §§11.60.230 to 11.60.240 (1962) .................7,16

IV

111. Ann. Stat. (Smith-Hurd ed.), c. 38, §§13-1 to 13-4

PAGE

(1964), c. 43, §133 (1944) .............................................. 7,16

Iowa Code Ann. §§735.1 and 735.2 (1950) .......................7,18

NJ Stat. Ann., §§10:1-2 to 10:1-7 (1960), §§18:25-1 to

18:25-6 (1964 Snpp.) ....................................... .............. 7,16

NM Stat. Ann., §§49-8-1 to 49-8-7 (1963 Supp.) .... ...... 7,16

NY Civil Eights Law (McKinney ed.) Art. 4, §§40 and

41 (1948, 1964 Supp.), Exec. Law, Art. 15, §§290 to

301 (1951, 1964 Supp.), Penal Law, Art. 46, §§513

to 515 (1944) ................................................................... 7,16

Pa. Stat. Ann., Tit. 18, §4654 (1963) .......................... .7,16

RI Gen. Laws Ann., §§11-24-1 to 11-24-6 (1956) .........7,16

Other Authorities:

U.S. Code Cong, and Ad. News (1964), p. 2358 ........... 11

2 U.S. Cong. Adm. News 2357 (1964) ........................... 20

110 Cong. Eec. 1511 ................... 16

110 Cong. Eec. 1520 ........................................................ 13

110 Cong. Eec. 7402 .............................................. 15

110 Cong. Eec. 7406-07 ...................... 12,13

Hearings on S. 1732 before the Senate Committee on

Commerce, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963) at 24 ....... 21

I n the

lmt£& ntvB (Unun nf Amalfi

F ob the E ighth Cibcuit

No. 18824

Mbs. Dobis Daniel and Mbs. Rosalyn K yles,

-v.-—

Appellants,

E tjell Paul, Jk., individually and as Owner,

Operator or Manager of Lake Nixon Club,

Appellee.

ON A PPE A L FBOM T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTRICT COURT

FOE T H E EASTERN D ISTRICT OF A R K A N SAS,

W ESTE R N DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Statement

This is an appeal from the February 1, 1967 Decree of

the District Court o f the Eastern District of Arkansas,

dismissing appellants’ complaint with prejudice.

On or about July 10, 1966, appellants Mrs. Doris Daniel

and Airs. Rosalyn Kyles, both of whom are Negroes, went

to Lake Nixon to swim and use the other available facil

ities after hearing its advertisements on the radio. Lake

Nixon is owned and operated by appellee Euell Paul, Jr.

and his wife (R. 38 and 40). Appellants were told by

2

Mrs. Paul that Lake Nixon was a private club and that

they had to be members in order to use the facilities.

They were further informed that the membership was

filled (E. 39). However, it was subsequently disclosed

that, in fact, the membership has never been full and

appellants were rejected because they were Negro (E.

26 and 46). Mrs. Paul further testified that the club ar

rangement is used to exclude Negroes (E. 44).

Lake Nixon, located on Eoute 1 a few miles outside of

Little Eock, Arkansas, is comprised of 232 acres (E. 42

and 43). Appellee and his wife purchased this property

in 1964 for $100,000 (E. 43). Approximately 100,000 people

make use of the facilities at Lake Nixon every season

(E. 44). Appellee has always operated Lake Nixon for

white persons only, to the exclusion of Negroes, and only

since 1964 has appellee considered Lake Nixon to be a

private club (E. 46 and 47).

Lake Nixon offers swimming, boating, picnicking, sun

bathing, miniature golf and general relaxation (E. 18 and

54). The 15 paddle boats available for use at Lake Nixon

are leased by appellee from a company in Bartlesville,

Oklahoma. Appellee also has two “yaks” (which are simi

lar to surf boards) which may be used by its patrons.

These “yaks” were purchased from the same company in

Oklahoma (E. 28 and 29). Appellee has two rented juke

boxes on the premises which were manufactured outside

of the State of Arkansas but are rented from a local dealer

(E. 29, 30 and 54). Patrons may dance or simply listen

to the juke box music (E. 30). Lake Nixon customarily

presents dances on Friday night (E. 30). Small bands

play at these dances (E. 33).

There is a snack bar located on the premises which sells

hamburgers, hot dogs, soft drinks and milk to Lake Nixon’s

patrons (E. 12, 30 and 35). The snack bar is run by

3

appellee’s sister-in-law. Under a mutual agreement they

share the profit (E. 32). In 1965 and 1966 appellee spent

from five to six thousand dollars for the purchase of the

food sold at the snack bar. The net profit from these food

sales was from $1,500 to $2,000 for those same years.

Lake Nixon’s net income for the years 1965 and 1966 was

$15,121.28 and $17,892 respectively (E. 12). The court

took judicial notice that the principal ingredients going

into the bread sold were produced and processed in other

states and that certain ingredients going into the processing

of soft drinks were obtained from sources outside of the

state (E. 58). Borden’s of Arkansas, Wonder Bakery,

Frito-Lay and Coca Cola Bottling Company are some of

the companies which supply goods and products sold at

Lake Nixon (E. 11).

The membership fee at Lake Nixon is 25 cents for the

season. I f a person wishes to swim in the lake, he must

pay an additional 50 cents; to boat, 25 cents; to play

miniature golf, 35 cents; and to attend the dances, $1.00

(E. 27 and 28).

On July 18, 1966, appellants filed a class action complaint

in the District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas,

Western Division, seeking to enjoin the appellee from

maintaining any policy of depriving or interfering with

the rights of appellants and others similarly situated to

admission to and full enjoyment and use of the goods,

services and facilities of Lake Nixon. Appellants allege

that they were denied admission in violation of Title II

of the Civil Eights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000a et seq.

The jurisdiction of the district court was invoked pursuant

to 28 U.S.C. §§1343(3) and 1343(4) (E. 3).

On December 7, 1966, trial was held before the Honorable

J. Smith Henley. On February 1, 1967 Judge Henley, in a

4

memorandum opinion, held that Lake Nixon was not an

establishment covered by Title II of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964. Although appellee’s claim of exemption as a

private club was rejected (R. 58), the court held that

Lake Nixon was not covered by Section 201(b)(4) of

Title II since its food sales were not its principal business

but were only adjunct to its principal business of making

recreational facilities available to the public. The court

further held that Lake Nixon was not a place of “ enter

tainment” within the meaning of Section 201(b)(3) since

its facilities were primarily for the purpose of recreation

whereby patrons could enjoy and amuse themselves as

compared with being amused as a passive spectator (R. 60)

and that even if it were a “place of entertainment” it did

not affect commerce within the meaning of §201 (c) of

Title II (R. 61). The court found that only passive amuse

ment constitutes “ entertainment” within the meaning of

Title II (R. 59-61).

A decree of dismissal was entered on February 1, 1967

and the instant appeal was filed on March 2, 1967 (R. 63).

5

STATEMENT OF POINTS TO BE ARGUED

I.

Lake Nixon Is an Establishment Covered by Section

2 0 1 ( b ) ( 4 ) (42 U.S.C. §2000a ( b ) ( 4 ) ) of Title II

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Cases:

Evans v. Laurel Links, Inc., 216 F.Supp. 474

(E.D. Ya. 1966);

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306;

Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294;

Pinkney v. Meloy, 241 F.Supp. 943 (M.D. Fla.

1965).

Statutes:

42 U.S.C. §§2000a(b)(2), (b )(4 ), and (c)(2 ).

6

Lake Nixon is a “ place of entertainment” whose

operations affect commerce within the meaning of

Sections 2 0 1 ( b ) ( 3 ) and 2 0 1 ( c ) ( 3 ) (42 U.S.C.

§§2000a(b ) (3 ) and (c) (3 ) ) of Title II of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964.

Cases:

A.B.T. Sightseeing Tours, Inc. v. Gray Line,

242 F.Supp. 365 (S.D. N.Y. 1965);

Amos v. Prom, Inc., 117 F.Supp. 615 (N.D.

Iowa 1954);

Central Amusement Company v. District of

Columbia, 121 A.2d 865 (Mun. Ct. App. D.C.

1956);

Dilworth v. Riner, 343 F.2d 226 (5th Cir. 1965);

Fraser v. Robin Dee Day Camp, 44 N.J. 480

(1965).;

City of Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808;

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306;

Katzenbach v. McClung-, 379 U.S. 294;

Lambert v. Mandel’s of California, 156 Cal. App.

Rep.2d 855 (1957);

McClung v. Katzenbach, 233 F.Supp. 815 (N.D.

Ala. 1964), rev’d. 379 U.S. 294;

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 239

F.Supp. 323 (E.D. La. 1967);

Rachel v. Georgia, 384 U.S. 780;

Robertson v. Johnston, 249 F.Supp. 618 (E.D.

La. 1966);

Stiska v. City of Chicago, 405 111. 374 (1950);

Twitty v. Vogue Theatre Corp., 242 F.Supp.

281 (M.D. Fla. 1965);

II.

7

United States v. Alabama, 304 F.2d 583 (5th

Cir. 1962), aff’d 371 U.S. 37;

United States v. Sullivan, 332 U.S. 689;

Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U.S. 111.

Statutes:

42 U.S.C. §§2000a(b)(3) and (c )(3 );

Alaska Stat., §§11.60.230 to 11.60.240 (1962);

111. Ann. Stat. (Smith-Hurd ed.), c. 38, §§13-1

to 13-4 (1964), c. 43, §133 (1944);

Iowa Code Ann. §§735.1 and 735.2 (1950) ;

NJ Stat. Ann., §§10:1-2 to 10:1-7 (1960),

§§18:25-1 to 18:25-6 (1964 Supp.) ;

NM Stat. Ann., §§49-8-1 to 49-8-7 (1963 Supp.);

NY Civil Eights Law (McKinney ed.) Art. 4,

§§40 and 41 (1948, 1964 Supp.), Exec. Law,

Art. 15, §§290 to 301 (1951, 1964 Supp.),

Penal Law, Art. 46, §§513 to 515 (1944);

Pa. Stat. Ann., Tit. 18, §4654 (1963);

E l Gen. Laws Ann., §§11-24-1 to 11-24-6 (1956).

8

ARGUMENT

I.

Lake Nixon is an Establishment Covered by Section

2 0 1 ( b ) ( 4 ) (42 U.S.C. §2000a ( b ) ( 4 ) ) of Title II

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

It is appellants’ position that since a snack bar covered

by Section 201(b) (2) of Title II is physically located within

the premises of Lake Nixon, the entire facility is covered

under Title II by the operation of Section 201(b)(4).

A. The snack bar at Lake Nixon is a facility principally

engaged in selling food for consumption on the premises

within the meaning of Sections 2 0 1 (b ) (2 ) and 2 0 1 (c ) (2 )

(4 2 U.S.C. §§2 0 0 0 a (b )(2 ) and ( c ) ( 2 ) ) of Title II.

Section 201(b)(2) of Title II of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 provides:

(b) Each of the following establishments which

serves the public is a place of public accommodation

within the meaning of this title if its operations affect

commerce, or if discrimination or segregation by it is

supported by State action:

# * #

(2) any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom, lunch

counter, soda fountain, or other facility principally

engaged in selling food for consumption on the

premises, including, but not limited to, any such

facility located on the premises of any retail estab

lishment; or any gasoline station.

The district court held that Lake Nixon was not covered

by this section since its food sales were not its principal

business—but only “ adjunct to the principal business of

9

making recreational facilities available to the public.” Ob

viously, Lake Nixon is a recreation area and not a restau

rant. However, it is appellants’ position that the snack

bar located on the premises of Lake Nixon is clearly

covered by §201 (b)(2). A simple reading of this section

indicates that a lunch counter “ located on the premises

of a retail establishment” (using the language of the

statute) is covered by Title II. Yet, the principal business

of a retail establishment is not the sale of foods. Likewise,

the lunch counter at Lake Nixon cannot be exempted simply

because the establishment as a whole is not engaged in

the sale of foods. In Evans v. Laurel Links Inc., 261

F.Supp. 474 (E.D. Va. 1966), a district court found a lunch

counter located on a golf course to be covered by §201 (b) (2),

although it accounted for only 15% of the gross receipts

of the golf course.

Hamburgers, hot dogs, soft drinks and milk are sold

at the Lake Nixon snack bar. The court took judicial

notice that the principal ingredients going into the bread

sold and some of the ingredients in the soft drinks were

produced and processed outside of the State of Arkansas.

Thus, since a substantial portion of the food sold has tra

velled through interstate commerce, the operations of the

snack bar affect commerce within the meaning of §201(c) (2)

of Title II. See Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294.

Approximately 100,000 people use the facilities at Lake

Nixon each season. Located on Route 1, a few miles out

side of Little Rock, Arkansas, it is comprised of 232 acres.

The court found that some out-of-state people spending

time in or around Little Rock have probably used the

facilities and since membership cards were routinely dis

tributed without the name and address of the member

being inserted on the cards it is very possible that such

10

travellers obtained membership. Appellee recognized such

a possibility. Appellee did not in any way discourage or

prohibit interstate travellers from using Lake Nixon. By

offering the facilities, including the snack bar, to the gen

eral public it was offering to interstate travellers as well.

Therefore, the snack bar’s operations can be said to affect

commerce because it “ offers to serve” interstate travellers.1

The Supreme Court found such an offer to the general

public sufficient for coverage in Hamm v. City of Rock Hill,

379 U.S. 306.

The snack bar is engaged in selling food for consumption

on the premises; a substantial portion of the food has

travelled through interstate commerce and it offers to sell

to the general public. It is therefore clearly a facility

covered by §201 (b)(2) of Title II of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964.

B. The snack bar is located within the premises of Lake

Nixon, therefore, the whole of Lake Nixon is a covered

establishment.

Section 201(b)(4) of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 provides:

Each of the following establishments which serves

the public is a place of public accommodation within

the meaning of this title if its operations affect com

merce, or if discrimination or segregation by it is

supported by State action:

# # #

(4) any establishment (A )(i) which is physically

located within the premises of any establishment

otherwise covered by this subsection, or (ii) within

1 There is no substantiality requirement in the “ offers to serve” portion

of §201 (e) (2). Hamm v. City of Bock Hill, 379 U.S. 306.

11

the premises of which is physically located any .such

covered establishment, and (B) which holds itself

out as serving patrons of such covered establishment.

The district court construed this section as contemplating

at least two distinct and separate establishments, one of

them covered by the Act, operating from the same general

premises. It viewed Lake Nixon as a single unit operation

with the sales of food and drink being merely adjunct to

the principal business of making recreational facilities

available to the public and therefore not covered by

§201(b)(4). Pinkney v. Meloy, 241 F.Supp. 943 (M.D.

Fla. 1965) was cited by the court in support of its con

clusion. It is appellants’ position that this is a completely

erroneous construction of the statute; one that ignores

the legislative history and creates anomalous results.

Admittedly, Pinkney involved two establishments—a

barbershop and a hotel under different managements. The

court found the hotel to be an establishment covered by

Title II and by the operation of §201 (b)(4) included the

barbershop in this coverage. However, Pinkney does not

represent the only possible interpretation of the coverage

of §201 (b) (4) of Title II. In Pinkney, the court recognized

that §201 (b)(4) of the Act originally used the term “ in

tegral part” rather than physically located within as fol

lows :

Prior to the adoption of this section it was noted

in U.S. Code Cong, and Ad. News (1964), p. 2358:

“ The term ‘integral part’ is defined * * * as mean

ing physically located on the premises of an estab

lishment subject to subsection 3(a) [substantially

similar to 201 of the final bill] * ". Thus, in all

instances, to be an integral part, the establishment

12

would have to be physically located on the premises

of an included establishment or located contiguous

to such an establishment. A hotel barbershap or

beauty parlor would be an integral part of the hotel,

even though operated by some independent person

or entity.” At 947 (Emphasis added.)

As the emphasized language indicates, Congress contem

plated that a single management enterprise would cer

tainly be covered by §201(b)(4) and if operated by an

independent person and if integral to the total operations,

the entire facility would likewise be covered. Therefore,

Congress was most immediately directing its attention

to single management establishments contrary to the dis

trict court’s finding. I f the district court’s interpretation

were to prevail, the anomalous result would be that a hotel

operating its own barbershop could somehow discriminate

by refusing to cut a Negro’s hair, while an independently

owned shop within the hotel could not so discriminate.

Or, a lunch counter in a retail establishment not otherwise

covered could discriminate if owned by the retail store,

but not if operated by a separate owner. Certainly Con

gress did not intend such a situation to be permissible.

The following statements by Senator Magnuson also

make it clear that the existence of an eating facility covered

by Title II within a dominant establishment which itself

would not otherwise be covered causes the whole establish

ment to be covered.

The specific mention in section 201(b) of eating facil

ities ‘located on the premises of any retail establish

ment’ is aimed principally at such facilities in depart

ment and variety stores.

^

13

The best example of this fourth category of section

201(b) are a barbershop located in a hotel which

holds out its services to guests and a department

store which maintains a lunchroom within its premises.

A department store or other retail establishment would

not be subject as such to the restrictions of Title II.

But if it contains a public lunchroom or lunch counter,

it would be required to make all its facilities, not

simply its eatery facilities, available on a nondis-

criminatory basis. 110 Cong. Rec. 7406-07.

Also see similar statements by Representative Celler, Chair

man of the Judiciary Committee which reported the bill.

110 Cong. Rec. 1520.

Appellants submit that Evans v. Laurel Links, Inc., 261

F.Supp. 474 (E.D. Ya. 1966) is a more reasoned inter

pretation of the meaning and scope of §201 (b)(4) of

Title II. In that case, the court found that a lunch counter

located in the clubhouse of a golf course was an eating

facility within the meaning of §201 (b)(2) and that the

location of the lunch counter on the premises brought the

entire golf course within the act by the operation of

§201(b)(4).

Neither the legislative history nor the clear language

of the statute justifies the district court’s decision to

exclude the snack bar at Lake Nixon and consequently

the entire facility, because the sale of food is not the

major concern of Lake Nixon. The snack bar at Lake

Nixon is no different in character than an eating facility

in a retail store clearly covered by §201 (b )(2 ), and this

facility causes the entire store to be covered by §201 (b) (4)

of Title II. Appellants submit that this Court should like

wise find Lake Nixon to be a covered establishment under

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

14

II.

Lake Nixon is a “ Place of Entertainment” Whose

Operations Affect Commerce Within the Meaning of

Sections 2 0 1 ( b ) ( 3 ) and 2 0 1 ( c ) ( 3 ) (42 U.S.C.

§§2000a(b ) (3 ) and (c) ( 3 ) ) of Title II of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964.

It is appellants’ position that the Court should find that

Lake Nixon is covered by §201(b) (4) of Title II ; however,

it is also submitted that Lake Nixon is a “place of enter

tainment” covered by §201 (b) (3) of Title II.

A. The dichotomy between spectator and participative ac

tivity is unrealistic and not supported by the legislative

history of Title II or by the case law with respect to the

coverage of state public accommodations laws.

Section 201(b)(3) of Title II of the Civil Eights Act of

1964 provides:

(b) Each of the following establishments which

serves the public is a place of public accommodation

within the meaning of this title if its operations affect

commerce, or if discrimination or segregation by it is

supported by State action:

(3) any motion picture house, theater, concert

hall, sports arena, stadium or other place of exhibi

tion or entertainment; and

The district court held that Lake Nixon’s activities did

not constitute “ entertainment” within the meaning of

§201(b)(3). The court accepted the dichotomy between

spectator and exhibitive activities with respect to the

meaning of “ entertainment” adopted by Robertson v. John

ston, 249 F.Supp. 618 (E.D. La. 1966) and Miller v. Amuse

15

ment Enterprises, Inc., 239 F.Supp. 323 (E.D, La. 1967).

It is appellants’ position that the Eastern District of

Louisiana as well as the court below have thus miscon

strued the intent and clear language of the Act.

Lake Nixon offers swimming, boating, picnicking, sun

bathing and miniature golf. There are also two juke boxes

which patrons may simply listen to or dance. Lake Nixon

also regularly presents dances on Friday nights and in

vites bands to play. The distinct court held that these

activities were not “ entertainment” since they are essen

tially participative in nature. This technical and narrow

approach is not justified by the legislative history of

Title II.

There is no language to be found in the legislative his

tory of Title II which specifically includes or excludes a

facility like Lake Nixon from the meaning of the term

“ entertainment.” There is also no evidence in the legis

lative history which shows that Congress intended the

coverage of §201 (b)(3) to be limited to exhibitive enter

tainment. Indeed, the following statement of Senator

Magnuson, floor manager of Title II, indicates that Con

gress did not intend §201 (b)(3) to be limited to motion

picture theaters (which are exhibitive activities) to the

exclusion of participative activities:

These principles [restriction of the flow of goods

through interstate commerce] are applicable not merely

to motion picture theaters but to other establishments

which receive supplies, equipment or goods through

the channels of interstate commerce. 110 Cong. Ree.

7402 (emphasis added).

In calling up the Civil Rights Act of 1964 for considera

tion by the House, Representative Madden spoke of the Act

16

as “ the first really comprehensive civil rights legislation

in our history.” 2 3 Representative Daniels spoke thusly:

Racial discrimination in places of public accommoda

tions is one of the most irritating and humiliating

forms of discrimination the Negro citizen encounters

and one which requires immediate remedy. 110 Cong.

Rec. 1511.

He viewed Title II as designed to eliminate these injustices.

Representative Celler, Chairman of the House Judiciary

Committee, which reported out the bill and who was one

of the chief proponents of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in

Congress, stated that Title II was intended to apply what

“ . . . thirty states anĉ the District of Columbia are now

doing to the rest of the states so that there shall be no

discrimination in places of public accommodations pri

vately owned . . .” 110 Cong. Rec. 1518.3 These statements

show that Congress sought to eliminate racial discrimina

tion in all places of accommodation open to the general

2 110 Cong. Rec. 1511.

3 Five states have public accommodations laws which specifically cover

amusement parks.

Pennsylvania: Pa. Stat. Ann., Tit. 18, §4654 (1963); New Jersey:

FJ Stat. Ann., §§10:1-2 to 10:1-7 (1960), §§18:25-1 to 18:25-6 (1964

Snpp.) ; New York: NY Civil Rights Law (McKinney ed.) Art. 4,

§§40 and 41 (1948, 1964 Supp.), Exec. Law, Art. 15, §§290 to 301

(1951, 1964 Supp.), Penal Law, Art. 46, §§513 to 515 (1944); New

Mexico: NM Stat. Ann., §§49-8-1 to 49-8-7 (1963 Supp.); Rhode Island:

RI Gen. Laws Ann., §§11-24-1 to 11-24-6 (1956).

Seven state public accommodations laws cover skating rinks.

Supra, note 10 and Illinois: 111. Ann. Stat. (Smith-Hurd ed.), c. 38,

§§13-1 to 13-4 (1964), c. 43, §133 (1944); and Alaska: Alaska Stat.,

§§11.60.230 to 11.60.240 (1962).

The activities covered by these state laws are clearly participative and

not just of the passive spectator type.

17

public, if their operations have an effect upon interstate

commerce.4 5

Title II should be liberally construed.6 The Civil Rights

Act of 1964 should be given the same liberal construction

that the courts afforded the Civil Rights Act of 1957.*

And this Court should give §§201(b)(3) and (c)(3 ) the

same broad application that other appellate courts have

given Title II in other situations.7

Webster’s dictionary defines entertainment as “ that

which engages the attention agreeably, amuses, or diverts,

whether in private as by conversation, etc., or in public.”

The district court ignored the plain meaning of Section

201(b)(3) in construing “ entertainment” to embrace only

exhibitive activity. The Court’s reliance on the principle

of ejusdem generis to reach this construction was mis

placed.

The contention that ejusdem generis requires a court to

construe a state public accommodations statute to exclude

from coverage participative activities (i.e., Lake Nixon)

because the types of activities which are specifically cov

4 Cf. McClung v. Katzenbach, 233 F.Supp. 815, 825 (N.D. Ala. 1964),

rev’d. 379 U.S. 294, in which, although the court declared the act un

constitutional, concluded that it was “ simple truth” that Congress in

tended “ to put an end to racial discrimination in all restaurants.”

5 Cf. Lambert v. Mandel’s of California, 156 Cal. App. Rep.2d 855

(1957)—state public accommodations law is to be given a “ liberal, not

a strict, construction” ; similarly, Fraser v. Robin Dee Day Camp, 44

N.J. 480 (1965).

6 United States v. Alabama, 304 F.2d 583, 591 (5th Cir. 1962), ail’d.

371 U.S. 37.

7 Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306—Title II applied retro

actively to invalidate “sit-in” convictions obtained prior to its enactment;

Rachel v. Georgia, 384 U.S. 780— Title II read broadly to authorize

removal of State “sit-in” prosecution to federal courts although other

types of prosecution are not removable; compare City of Greenwood v.

Peacock, 384 U.S. 808, and Dilworth v. Riner, 343 F.2d 226 (5th Cir.

1965).

18

ered by the statute are exhibitive in nature has been

presented in a number of jurisdictions. The courts have

generally rejected this contention. The following cases

are good examples of the ways this issue has been

presented.

In Amos v. Prom, Inc., 117 F.Supp. 615, 623 (N.D. Iowa

1954) the Court construed Iowa’s public accommodations

law8 which covered, among other places, “ theaters and

other places of amusement” as being applicable to a public

ballroom or dance hall. This was done in the face of a

contention by the defendant that the term other places of

amusement should be limited to exhibitive entertainment

because of the principle of ejusdem generis. Stiska v.

City of Chicago, 405 111. 374 (1950) is another example

of a court’s refusal to limit amusement to exhibitive enter

tainment although the term amusements had been preceded

by “theatricals and other exhibitions, shows . . .” in its

statute and although defendants who were operators of

bowling alleys, billiard parlors and ballrooms claimed that

their establishments were not covered by a state statute

which conferred authority upon municipalities to “ license,

tax, regulate or prohibit . . . theatricals and other exhibi

tions, shows and amusements.” In a similar case involving

a municipal licensing statute, Central Amusement Com

pany v. District of Columbia, 121 A.2d 865 (Mun. Ct. App.

D.C. 1956), the types of activities which were specifically

enumerated in a state licensing statute were also only

exhibitive in nature. The court held that a bowling alley

could be construed to fall within the meaning of that

statute.

However, even if the district court’s dichotomy were

adopted, Lake Nixon would still be a place of entertain

8 Iowa Code Ann. §§735.1 and 735.2 (1950).

19

ment since many of its activities are of the spectator type.

Certainly not all of Lake Nixon’s patrons dance to the

music of the two juke boxes—many passively (to use the

standard of the court below) stand by and listen. Likewise

not all persons actually dance at the dances regularly

sponsored at Lake Nixon—many passively stand by and

listen. Therefore, even within the confines of the district

court’s narrow interpretation, Lake Nixon is a place of

entertainment within the meaning of §201 (b)(3).

B. The operations of Lake Nixon affect commerce within the

meaning of Section 2 0 1 (c ) (3 ) of Title II.

Section 201(c) (3) provides:

(c) The operations of an establishment affect com

merce within the meaning of this title if . . . (3) in

the case of an establishment described in paragraph

(3) of subsection (b), it customarily presents films,

performances, athletic teams, exhibitions, or other

sources of entertainment which move in commerce;

The district court narrowly construed §201 (c)(3 ) and

held that Lake Nixon’s operations do not affect commerce

because they do not move (meaning continuously move)

in interstate commerce. The fact that the entertainment

apparatus had moved in interstate commerce was not

sufficient for the district court. It is submitted that the

court has thus disregarded the legislative intent and the

established notions of what constitutes interstate commerce.

In a section-by-section analysis of Title II, the Senate

Report (Judiciary Committee) made reference to what

constitutes an effect on commerce within the meaning of

§201(c)(3) (42 U.S.C. §2000a(c)(3)) in the following way:

These public establishments would be within the pur

view of the Bill even though at any particular time

20

the sources of entertainment being provided do not

move in interstate commerce. It is sufficient if the

establishment “customarily” presents entertainment

that has moved in interstate commerce. I f this test is

met then the establishment would be subject to the

Bill at all times, even if current entertainment had

not moved in interstate commerce. 2 U.S. Cong. Adm.

News 2357 (1964) (emphasis added).

If this is an indication of legislative intent, it is clear that

if the sources of entertainment had moved in interstate

commerce, the establishment would affect commerce within

the meaning of §201(c)(3) and it would not be necessary

to show a continuous movement.

This interpretation was adopted in Twitty v. Vogue

Theatre Corp., 242 F.Supp. 281, 287 (M.D. Fla. 1965).

In this case the defendant contended that since the films

had come to rest, the establishment in question did not

affect commerce within the meaning of §201 (c)(3). This

contention was rejected and the court stated, “ . . . but the

act does not restrict the time for determining the nature

of the movement of the film. . .

It is also clear that if an item has been shipped through

the channels of interstate commerce, although it has come

to rest it is still in commerce in the sense that Congress

still retains authority to regulate with respect to it. United

States v. Sullivan, 332 U.S. 689; A.B.T. Sightseeing Tours,

Inc. v. Gray Line, 242 F.Supp. 365 (S.D. N.Y. 1965).

The fifteen (15) paddle boats available for use at Lake

Nixon are leased from a company in Bartlesville, Okla

homa; the two “yaks” were purchased from this same

company. The two rented juke boxes were manufactured

outside of the State of Arkansas. Therefore, most of the

21

sources of entertainment available at Lake Nixon have

come from outside of the State of Arkansas. Admittedly,

if viewed in isolation, the volume of these instruments

supplied from out of state is insignificant when compared

with the total movement of similar items through com

merce ; however, as the Attorney General testified:

We intentionally did not make the size of the busi

ness the criterion for coverage because we believe that

discrimination by many small establishments imposes

a cumulative burden on interstate commerce.9

In Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294, the Supreme

Court, citing Wickard v. Filburn, 317 IT.S. I l l , refused to

limit itself to an examination of the individual establish

ment’s contribution to interstate commerce but accepted

the test of commerce enunciated in the Filburn case as

being “his contribution, taken together with that of many

others similarly situated.” At 127-128.

I f this Court is to effectuate the intent of Congress it

must find that Lake Nixon is a public accommodation cov

ered by Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

9 Hearings on S.1732 before the Senate Committee on Commerce, 88th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1963) at 24.

22

CONCLUSION

W herefore, appellants pray that the judgment below

be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

John W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas 12206

Jack G-reenberg

Michael Meltsner

Gabrielle A. K irk

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

Certificate o f Service

This is to certify that on t h e ------ day of June, 1967,

I served a copy of the foregoing Appellants’ Brief upon

Sam Robinson, 115 East Capitol Street, Little Rock, Ar

kansas, by mailing a copy thereof to him at the above

address via United States mail, postage prepaid.

Attorney for Appellants

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N, V. C . ^ » 219