Memo from Hershkoff and Cohen to Counsel Re: Quality Education Meeting with Slavin and Dolan

Correspondence

November 27, 1991

4 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Memo from Hershkoff and Cohen to Counsel Re: Quality Education Meeting with Slavin and Dolan, 1991. 4fba6690-a446-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b1679353-17c8-4f9e-aa53-d7932aa572cd/memo-from-hershkoff-and-cohen-to-counsel-re-quality-education-meeting-with-slavin-and-dolan. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

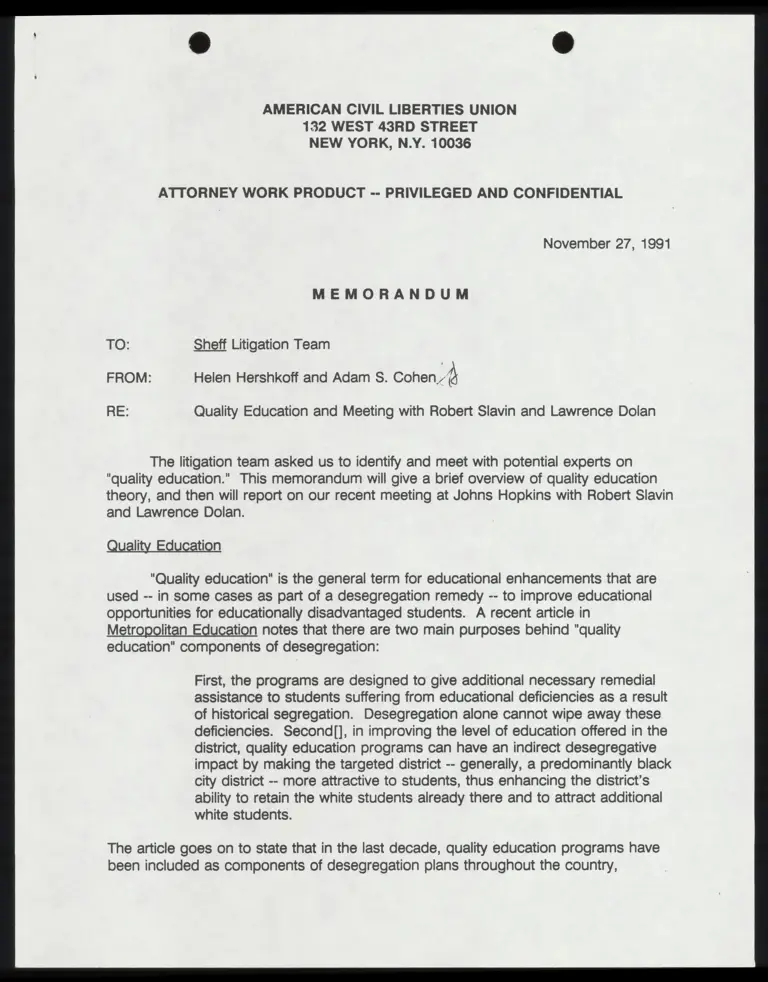

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

132 WEST 43RD STREET

NEW YORK, N.Y. 10036

ATTORNEY WORK PRODUCT -- PRIVILEGED AND CONFIDENTIAL

November 27, 1991

MEMORANDUM

TO: Sheff Litigation Team

FROM: Helen Hershkoff and Adam S. Cohen |

RE: Quality Education and Meeting with Robert Slavin and Lawrence Dolan

The litigation team asked us to identify and meet with potential experts on

"quality education." This memorandum will give a brief overview of quality education

theory, and then will report on our recent meeting at Johns Hopkins with Robert Slavin

and Lawrence Dolan.

lity E tion

"Quality education” is the general term for educational enhancements that are

used -- in some cases as part of a desegregation remedy -- to improve educational

opportunities for educationally disadvantaged students. A recent article in

Metropolitan Education notes that there are two main purposes behind “quality

education" components of desegregation:

First, the programs are designed to give additional necessary remedial

assistance to students suffering from educational deficiencies as a result

of historical segregation. Desegregation alone cannot wipe away these

deficiencies. Second(], in improving the level of education offered in the

district, quality education programs can have an indirect desegregative

impact by making the targeted district -- generally, a predominantly black

city district -- more attractive to students, thus enhancing the district's

ability to retain the white students already there and to attract additional

white students.

The article goes on to state that in the last decade, quality education programs have

been included as components of desegregation plans throughout the country,

including in such major cities as Chicago, Dallas, Indianapolis, Nashville, Wilmington,

Cleveland, and Buffalo, as well as smaller communities.

Quality education programs that have been implemented as part of the

remedies in previous desegregation lawsuits include five major components:

q Effective Schools. Traditional effective schools models are based on

five characteristics: a clear mission statement; continuous monitoring of student

progress; a principal who is an instructional leader; high expectations of teachers; and

an orderly and safe school environment. In the Kansas City case, the city district

proposed a plan whereby each elementary school with a reading level below the

national average would be eligible for grants of up to $100,000 in each of three years

to implement effective schools programs.

9 Reduction in Pupil-Teacher Ratios. Research in the past decade has

shown that smaller class sizes enhance student achievement particularly for

educationally disadvantaged students. Significant positive effects appear when the

pupil-teacher ratio is less than 25 to one, with the greatest improvements occurring

when the ratio is 15 to one or lower. In the Kansas City case, significant class

reductions were ordered and the state was required to fund the full cost of these

reductions up to a three-year maximum of $12 million.

q Early Childhood. Considerable research indicates that early childhood

education programs have a positive impact on the academic and social readiness of

pre-school children and that children who participate in these programs are more likely

to be socially and academically successful in school. The district court in St. Louis

approved an early childhood component of the settlement agreement and required the

state and city to share its cost.

9 Buildings. The condition of school buildings has a critical relationship

to public perception of the quality of education provided in a particular school and to

student attitudes and learning. This relationship was confirmed in a 1988 study by the

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and by an independent study

of the District of Columbia’s public schools earlier this year which found that student

achievement on standardized tests would be five to 11% higher if the physical

condition of the local schools improved. A study commissioned by the Kansas City

school district concluded that the total cost of necessary improvements in school

buildings would be between $55 and 70 million. The district court ordered the state to

pay $27 million for immediate facility improvements with an additional $10 million

coming from the city. These funds are to be spent according to the following

priorities: (1) eliminate safety and health hazards; (2) correct conditions which impede

the level of comfort needed for the creation of a good learning environment; and (3)

improve the facilities to make them visually attractive. After these improvements are

made, an additional plan is to be developed to bring Kansas City facilities "to a point

comparable with the facilities in the neighboring suburban school districts."

q Staff Development. Research indicates that the successful

implementation of new programs and the improvement of quality education requires

teachers and administrators to participate in staff-development programs. The St.

Louis settlement provided for the creation of a Staff Development Division that assisted

schools in the implementation of the effective schools program; provided staff training

in the development and implementation of new curriculum; and provided human

relations training programs for staff. The district court in Kansas City ordered the city

district to establish a staff development program and ordered the state to provide a

$500,000 fund to be used for stipends for after-school, weekend, and summer

sessions for teacher training, when it is impossible for such training to occur during

the regular school day.

Meeting with Slavin and Dolan

On November 15, 1991, we met for two hours with Robert Slavin and Lawrence

Dolan at Slavin’s office in Baltimore. Slavin is Director of the Center for Research on

Effective Schooling for Disadvantaged Students at The Johns Hopkins University, and

Dolan work with him there. They are the architects of the highly regarded "Success

for All" program for educationally disadvantaged youth. Success for All is a schoolwide

program for students in pre-K to three, with options for expansion to grades four and

five. The program is designed to take advantage of the availability of Chapter | funds.

At our meeting, we focused on four major topics: (1) the relationship between

a quality education remedy and desegregation; (2) the adequacy of Hartford’s current

programs for educationally disadvantaged students; (3) the components of a quality

education remedy and why they are effective; and (4) the potential cost of and funding

for a quality education remedy.

First, Slavin and Dolan see no inconsistency between a quality education

remedy and integration. Although it is true that quality education programs are

frequently provided as an alternative to desegregation, Slavin and Dolan agreed that

there was no reason that they could not be implemented in conjunction with a

desegregation remedy. In particular, Success for All programs are based on a

concept of cooperative learning and have been implemented as part of desegregation

remedies in Rockford, lll., Fort Wayne, Ind. and East Allen, Ind. Dolan promised to

provide us with information about the decrees entered in these school districts.

Second, Slavin and Dolan believe that in order for them to construct a quality

education remedy for the Hartford area, it is necessary for them to have an

understanding of the programs now in place in Hartford and the surrounding suburbs.

We provided them with a variety of reports that Martha had given us about special

programs in the Hartford school system. Slavin and Dolan do not, however, want to

undertake a comprehensive review of these programs. Instead, they have asked that

we find a Connecticut expert to review those programs and to help them with the

portion of their study that describes programs now in place. They are familiar with

Herman LaFontaine and Francis Archambault.

Third, Slavin provided us with two reports that describe in different ways the

components of a potential quality education remedy. The first, "Preventing Early

School Failure: What Works?," discusses the effectiveness of nine principal types of

early school intervention programs on children who are otherwise at risk of academic

failure. The second, "Effective Research-Based Programs for Use in the Baltimore City

Public Schools," sets out a possible quality education program for use in the Baltimore

schools. We also have a copy of Slavin’s book, Effective Programs for Students At

Risk: A Practical Synthesis of the Latest R rch on What Works to Enhance th

Achievement of At-Risk Elementary Students (1989).

Finally, Slavin and Dolan are willing to cost out a potential quality education

remedy for Hartford and the surrounding suburbs. For them to do so, we must

provide them with the following information:

1) Cost of Personnel -- State figure representing cost of personnel in

salary and benefits for master teachers, teachers, and aides (use Hartford scale rather

than suburban);

2) Training -- State figure representing cost of training teachers including

local per diem for training;

3) School Characteristics -- Size of system; Chapter 1 program; number

of schools impacted by the judgment; and

4) Student Demographics -- Percent free lunch; percent limited English

proficiency (currently and if desegregation remedy put into effect).

We believe that the team should retain Slavin and Dolan as experts, but we do

not yet have a cost estimate. They have asked us to send them a letter describing the

project and they will use that to develop a budget. With the possibility of a spring trial,

it is important that we get them started as soon as possible if we want to use them.

We will also need to retain a Connecticut expert to work with them (this could be the

education consultant that PRRAC has agreed to fund). We suggest that the team

convene by conference call the week of December 2 to discuss how to best to

proceed. Thank you.