Muntaqim v. Coombe Reply Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

May 13, 2005

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Muntaqim v. Coombe Reply Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 2005. 601356f1-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b16d5a7c-a5e1-451f-8260-ece5367cd85c/muntaqim-v-coombe-reply-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

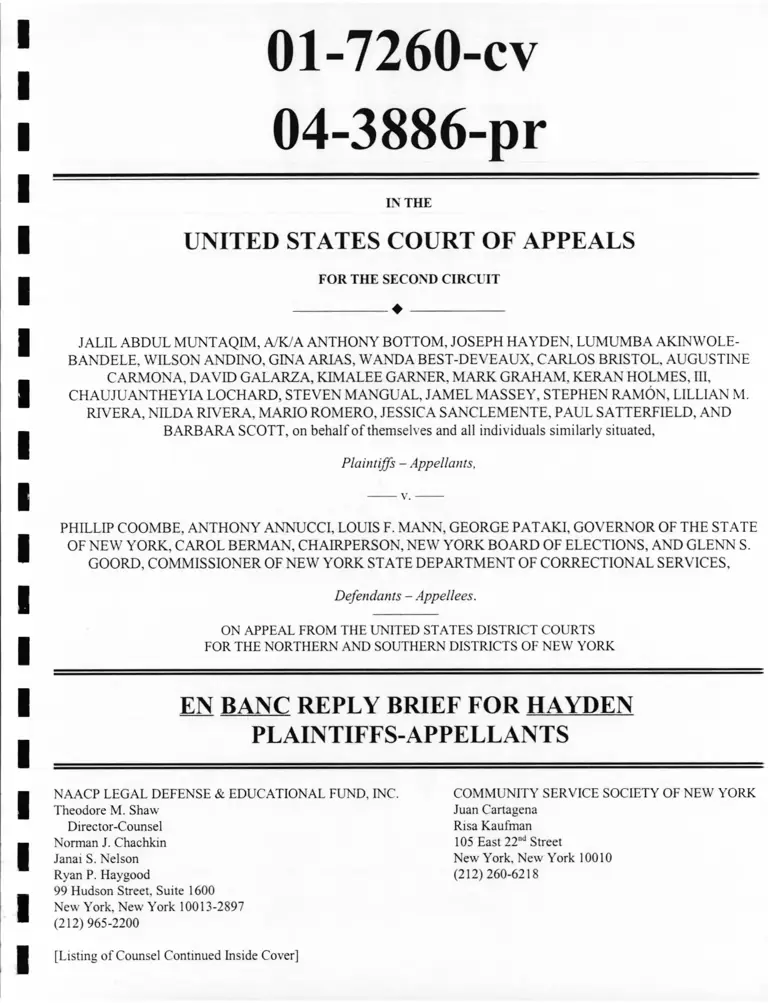

01-7260-cv

04-3886-pr

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

---------------------- + -----------------------

JALIL ABDUL MUNTAQIM, A/K/A ANTHONY BOTTOM, JOSEPH HAYDEN, LUMUMBA AKINWOLE-

BANDELE, WILSON ANDINO, GINA ARIAS, WANDA BEST-DEVEAUX, CARLOS BRISTOL, AUGUSTINE

CARMONA, DAVID GALARZA, KIMALEE GARNER, MARK GRAHAM, RERAN HOLMES, III,

CHAUJUANTHEYIA LOCHARD, STEVEN MANGUAL, JAMEL MASSEY, STEPHEN RAMON, LILLIAN M.

RIVERA, NILDA RIVERA, MARIO ROMERO, JESSICA SANCLEMENTE, PAUL SATTERFIELD, AND

BARBARA SCOTT, on behalf of themselves and all individuals similarly situated,

Plaintiffs - Appellants,

PHILLIP COOMBE, ANTHONY ANNUCCI, LOUIS F. MANN, GEORGE PATAKI, GOVERNOR OF THE STATE

OF NEW YORK, CAROL BERMAN, CHAIRPERSON, NEW YORK BOARD OF ELECTIONS, AND GLENN S.

GOORD, COMMISSIONER OF NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONAL SERVICES,

Defendants - Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURTS

FOR THE NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN DISTRICTS OF NEW YORK

EN BANC REPLY BRIEF FOR HAYDEN

PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

Theodore M. Shaw

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

Janai S. Nelson

Ryan P. Haygood

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013-2897

(212) 965-2200

[Listing of Counsel Continued Inside Cover]

COMMUNITY SERVICE SOCIETY OF NEW YORK

Juan Cartagena

Risa Kaufman

105 East 22nd Street

New York, New York 10010

(212) 260-6218

CENTER FOR LAW AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

MEDG.AR EVERS COLLEGE

Joan P. Gibbs

Esmeralda Simmons

1150 Carroll Street

Brooklyn. New York 11225

(718) 270-6296

Attorneys fo r Plaintiffs-Appellants

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Pursuant to Rule 26.1 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, the NAACP

Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc., Community Service Society of New York,

and the Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College, by and through

the undersigned counsel, make the following disclosures:

Counsel for Hayden Plaintiffs-Appellants. all not-for-profit corporations of the

State of New York, are neither subsidiaries nor affiliates of a publicly owned

corporation.

1

1

1

1

1

■

! tfndi ̂ fvM-WO

Janai S. Nelson, Esq.

Director of Political Participation

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2237

jnelson@naacpldf.org

1

mailto:jnelson@naacpldf.org

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

TABLE OF CONTENTS . . . .

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES . .

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

ARGUMENT...................................................................................................................3

I. NEW YORK’S FELON DISFRANCHISEMENT LAWS FALL

SQUARELY WITHIN THE AMBIT OF § 2 OF THE VRA ...........3

A. Section 5-106 Is A Regulatory Law and Therefore Creates No

Ambiguity in Section 2 of the V R A .............................................3

1. Section 5-106 Is Clearly A Regulatory Law Pursuant to

the Law of this Circuit and the Supreme C o u rt................5

2. The Regulatory Nature of §5-106 Is Not Altered by Its

1971 Amendment................................................................8

II. SECTION 2’S APPLICABILITY TO §5-106 IS FIRMLY AND

INDEPENDENTLY AUTHORIZED BY THE FIFTEENTH

AMENDMENT....................................................................................... 11

III. FELON DISFRANCHISEMENT INTERACTS WITH THE RACIAL

BIAS THAT EXISTS IN NEW YORK’S CRIMINAL JUSTICE

SYSTEM TO DENY AND UNLAWFULLY DILUTE

APPELLANTS’ RIGHT TO VOTE ON ACCOUNT OF RACE. . . 13

A. Bias in the Criminal Justice System ........................................ 13

B. Proof Under the Senate Factors of Section 2........................... 18

1

iv

11

CONCLUSION

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

FEDERAL CASES

In re Adams.

761 F.2d 1422 (9th Cir. 1985) ....................................................................................... 10

Baker v. Cuomo.

58 F.3d 814 (2d Cir. 1995)............................................................................................. 5.6

Chisom v. Roemer.

501 U.S. 380(1991)......................................................................................................... n

FTC v. Jantzen. Inc..

386 U.S. 228 (1967)......................................................................................................... 10

Flemming v. Nestor.

363 U.S. 603 (1960)........................................................................................................... 7

Fourco Glass Co. v. Transmirra Corp..

355 U.S. 222 (1957)........................................................................................................... 9

Foxhall Realty v. Telecomm. Serv..

156 F.3d 432 (2d Cir. 1998)............................................................................................. 10

Green v. Board of Elections.

380 F.2d 445 (2d Cir. 1967)............................................................................... e , S , U

Gregory v. Ashcroft.

501 U.S. 452 (1991)........................................................................................................... 3

Hudson v. U.S..

522 U.S. 93 (1997)............................................................................................................. 7

Kansas v. Hendricks.

521 U.S. 346 (1997)........................................................................................................... 7

Lassiter v. Northampton County Board o f Elections.

360 U.S. 45 (1959).......... 6

Peerless Casualty Co. v. U.S..

344 F.2d 495 (D.C. Cir. 1964) .......................................................................................... 9

Porter v. Committee of Internal Revenue.

856 F.2d 1205 (8th Cir. 1988) ....................................................................................... 10

Richardson v, Ramirez.

418 U.S.24 (1974)............................................................................................................ 12

IV

Ruth v. Eagle-Picher Company.

225 F.2d 572 (10th Cir. 1955) 9

Smith v. Doe.

538 U.S. 84 (2003).................................................................................................... 5; 6, 7

Trop v. Dulles.

356 U.S. 86 (1958)............................................................................................................. 6

United States v. Ward.

448 U.S. 242 (1980)........................................................................................................... 7

STATE CASES

People v. Oliver.

1 N.Y.2d 152 (1956) 19

DOCKETED CASES

Hayden v. Pataki.

No. 04-3886-PR 20

FEDERAL STATUTES

S. Rep. No. 97-417, at 27, 39 (1982), reprinted in 1982 U.S.C.A.N.N. 177, 179 .... 11,19

Section 2, S. Rep. at 28, U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News 1982 at 206 ........................ 18

STATE STATUTES

New York Election Law §5-106..................................

New York Elect. Law § 152.........................................

.passim

....... 5

MISCELLANEOUS

En Banc Brief for Hayden Plaintiffs-Appellants (“Hayden Appellants’ Opening

Br ”)........................................................................................................................... .. 14, 16

En Banc Brief in Support of Plaintiff-Appellant Jalil-Abdul Muntaquim, a/k/a Anthony

Bottom, and in Support of Reversal, on Behalf of Amici Curiae NAACP Legal

Defense & Educational Fund, Inc., Community Service Society o f New York, and

Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College (“Hayden Counsel

Amicus B rief”) ........................................................................................................... 16,18

v

Christopher Uggen and Jeff Manza, Democratic Contraction? Political

Consequences of Felon Disfranchisement in the United States. 67 Am.

Soc. Rev. 777 ............................................................................................................ 14 15

Cong. Globe, 40th Cong., 3d Sess. 1012-13 (1869) ........................................................ 12

In Banc Brief for Appellees (“Appellees’ Br.”)........................................................... .passim

In Banc Reply Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant Muntaquim......................................................3

New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services Study. 1995................................. 17

N.Y.S. Gov. Bill Jacket 1973, 679 .................................................................................. 9

vi

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Appellees and certain amici in their support would have this Court focus on

felon disfranchisement’s entrenchment in this Nation’s history, rather than confront

the racial context in which such laws operate today. In essence, Appellees ask this

Court to permit history and federalism concerns to trump racial discrimination, a

result that is antithetical to the United States Constitution. Felon disfranchisement,

regardless of its longevity or its general sanction by the Supreme Court, is not

immune from scrutiny where it results in palpable racial disparities that deny equal

access to the franchise on account of race. That scrutiny is anticipated and provided

for within the broad scope of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (“Voting

Rights Act,” “VRA” or “Act”).

Appellees have failed to remove New York’s felon disfranchisement laws from

Section 2 ’s reach, despite their efforts to distinguish it as a punitive measure and not

a voting qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice or procedure. Not only has this

Circuit interpreted New York Election Law §5-106 (“New York’s felon

disfranchisement statute,” or “§5-106”) as regulatory and not punitive, but the

Supreme Court has generally held that felon disfranchisement laws are accorded

regulatory status. This fact cannot be changed by the legislative history of §5-106’s

amendments or by the mere wishes of Appellees. Such a construction of §5-106

simply defies logic and legal precedent.

Moreover, Section 2’s coverage of felon disfranchisement laws like §5-106 is

grounded in the Reconstruction Amendments. The Fifteenth Amendment in

particular provides an independent source of Congressional authority to legislate

against racial discrimination in voting as it has through Section 2. As Appellees

concede, a Section 2 violation may be proved based on the disparate impact of felon

disfranchisement laws so long as the evidence of disparity is statistically significant

and is part of a broader analysis of the totality of the circumstances. Appellants’

(“Hayden Appellants”or “Appellants”) non-exhaustive description of the types and

quantity of evidence to support a Section 2 claim set forth in the En Banc Brief for

Hayden Plaintiffs-Appellants (“Hayden Appellants’ Opening Br.”) meets this

standard and is well supported by Section 2 case law. In addition, the Havden

Appellants are adequate and appropriate representatives to press claims of vote

dilution and vote denial through their designated subclasses.

2

ARGUMENT

I. NEW YORK’S FELON DISFRANCHISEMENT LAWS FALL

SQUARELY WITHIN THE AMBIT OF § 2 OF THE VRA1

A. Section 5-106 Is A Regulatory Law and Therefore Creates No

Ambiguity in Section 2 of the VRA

In an apparent, albeit confused,2 recognition of the need to establish ambiguity

in the text of Section 2 before applying the clear statement rule or the canon of

constitutional avoidance, Appellees attempt to create ambiguity in Section 2’s

crystalline text. Essentially, Appellees argue §5-106 is penal — not regulatory —

and, therefore, may not be considered a “voting qualification or prerequisite to voting

1 In addition to presenting the arguments raised in Section I of this brief,

Hayden Appellants join in the arguments set forth in Sections II and III of the In Banc

Reply Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant Muntaqim.

2 In Appellees’ feigned attempt to create ambiguity in Section 2, they fall prey

to the common misapplication of law in this area by conflating the clear statement

requirement with the threshold consideration of whether Section 2 is ambiguous on

its face. See, e.g.. In Banc Brief for Appellees (“Appellees’ Br.”), at 33 (“[T]he

question here is not whether a law requiring the electorate to be free of prior felony

convictions could be considered a ‘voting qualification or prerequisite to voting’ ..

. . Rather, the question is whether New York’s law, which serves only to punish an

offender while under the correctional supervision of the State, is necessarily covered

by the VRA.”) (emphasis in original). This is clearly the wrong standard, as the clear

statement rule may only be applied if is it determined that (1) a statute is ambiguous

on its face and (2) a possible construction of the statute alters the balance between

federal and state power. See, e.g.. Gregory v. Ashcroft. 501 U.S. 452, 470 (1991).

3

or standard, practice or procedure” under Section 2.3 Appellees hope that by

convincing this Court of this specious argument, they will clear the way for

application of the clear statement rule or the canon of constitutional avoidance and

prevail on the notion that states are accorded nearly absolute deference in the arena

of punishment.

Appellees’ strategy fails, however, because §5-106 is regulatory on its face and

has been interpreted as such by this Court. Indeed, the Supreme Court has held that,

as a general matter, felon disfranchisement laws are regulatory and not penal in

nature. Appellees, however, anchor their entire argument against this binding legal

precedent on the theory that select statements in the legislative history of the 1971

amendment to §5-106 transform it from regulatory to punitive. For the following

reasons, this Court must ignore Appellees’ attempt to create ambiguity in Section 2

where none exists and enforce the broad scope of Section 2 by holding that it applies

to §5-106.

3Of the many tribunals and parties examining whether Section 2 of the VRA

applies to felon disfranchisement, Appellees are the only ones to argue that an

ambiguity exists in the statute itself, raising the issue for the first time at the en banc

stage. The absence of any prior attempt by Appellees or the courts that have

considered this issue to demonstrate that the text of Section 2 is ambiguous on its face

is telling. Indeed, even now, in the most favorable construction of their argument,

Appellees do not state that Section 2 on its face is ambiguous; rather, they attempt to

take §5-106 out of the scope of Section 2 by denying §5-106’s regulatory character.

4

1. Section 5-106 Is Clearly A Regulatory Law Pursuant to the

Law of this Circuit and the Supreme Court

According to Supreme Court precedent, as well as corresponding

interpretations in the Second Circuit and elsewhere, courts must scrutinize legislative

intent in order to determine whether a statute is punitive or regulatory. Such a

determination requires a well-established two-part inquiry, as articulated by the

Supreme Court in its recent decision in Smith v. Doe. 538 U.S. 84, 92 (2003). First,

the court must consider whether the legislature clearly intended to designate the

statute as either punitive or regulatory, and if the statute is clearly punitive, the

inquiry ends, kb However, if the legislature intended the statute to serve as a civil

regulation, the court must then determine whether the law is nevertheless punitive in

“purpose or effect,” such that its regulatory intent is negated. Id,

In evaluating New York’s felon disfranchisement law, the Second Circuit held

in Green v. Board of Elections. 380 F.2d 445 (2d Cir. 1967) that the statute, then

codified as N.Y. Elect. Law § 152, was to be interpreted as a regulation, as opposed

to a punishment. Despite the various amendments that have been incorporated into

the New York felon disfranchisement law since Green, the Second Circuit’s

interpretation of the nature of the statute has not changed, since the state has continued

to cite the same regulatory justifications for the law. See Baker v. Cuomo. 58 F.3d

5

814, 821 (2d Cir. 1995) (ruling vacated on other grounds) (citing the justifications

stated in Green with respect to §5-106). Furthermore, applying the Smith two-part

inquiry to the current iteration of New York’s felon disfranchisement statute leads this

Court to the same conclusion that §5-106 is a regulatory measure.

The Supreme Court addressed this issue directly in Trop v. Dulles. 356 U.S. 86

(1958), where it held that the purpose of the statute controls whether it is penal or

regulatory. Id. at 97 (holding that felon disfranchisement laws are “a nonpenal

exercise of the power to regulate the franchise”).

The Trop decision essentially establishes felon disfranchisement laws as a

prototype of non-penal statutes.4 In recent years, particularly in connection with sex

offender registration statutes passed in conjunction with Megan’s Law, the Court has

further clarified its statutory interpretation analysis. In Smith v. Doe. 538 U.S. 84

(2003), which involved Alaska’s registration requirement, the Court drew on a

number of past decisions in articulating the framework for determining whether a

Subsequently, in Lassiter v. Northampton Countv Board of Elections. 360 U.S.

45, 51 (1959) (overruled with respect to the Court’s analysis of literacy tests and

grandfather clauses as prerequisites for voting), the Court held that states have the

authority to consider a range of factors in determining who should be eligible to vote.

Specifically, the Court found that states may consider a broad range of factors in

determining who may vote in its elections, including, as “obvious examples” of

permissible restrictions, “residence requirements, age, [and] previous criminal

record.” kL This suggests that felon disfranchisement provisions have long been

considered non-punitive measures meant to regulate the franchise.

6

statute is either punitive or regulatory. As a threshold matter, it is necessary to look

to the text and structure of the statute in order to determine its legislative purpose.

Smith. 538 U.S. at 92 (citing Flemming v. Nestor. 363 U.S. 603, 617 (I960)). If the

court finds that the legislature clearly intended to enact a punitive statute, the inquiry

must end there, particularly in light of the deference given to the legislature’s stated

intent. Smith. 538 U.S. at 92 (citing Kansas v. Hendricks. 521 U.S. 346, 361(1997)).

However, if the court finds that the legislature set out to enact a regulatory measure,

the statute must be examined further to determine whether the law is nonetheless so

punitive in its effect as to negate the legislature’s intent. Smith. 538 U.S. at 92;

Hendricks. 521 U.S. at 361; United States v. Ward. 448 U.S. 242, 248-249 (1980).

Despite this further inquiry, however, a determination that the legislature meant to

create a regulatory scheme may be overridden only where there exists the “clearest

proof’ that the scheme should be interpreted as a criminal penalty nevertheless.

Hudson v. U.S.. 522 U.S. 93, 100 (1997).

In their zeal to establish §5-106 as a regulatory law, Appellees failed to apply

any of these tests to the law and have not demonstrated that it is in fact punitive. In

reality, the law of this Circuit and Supreme Court precedent in this area firmly

7

establishes that §5-106 is a regulatory function of election administration and not a

punitive measure.-

2. The Regulatory Nature of §5-106 Is Not Altered by Its 1971

Amendment

To foreclose Appellants’ claims, Appellees, in a newly-manufactured

argument, assert that Section 2 of the VRA is inapplicable to New York’s felon

disfranchisement statute because it is “intended as a punishment of criminal

offenders, not as a regulation of voting.” Appellees’ Br. at 17. Appellees’

conclusory argument offends the rules of statutory construction and is wholly

unsupported by this Court’s ruling in Green that, with regard to an earlier version of

New York’s felon disfranchisement law, “[depriving convicted felons of the

franchise is not a punishment but rather is a ‘nonpenal exercise of the power to

regulate the franchise.’” Green. 380 F.2d at 449. The Appellees struggle mightily

to diminish Green’s primacy, arguing that the 1971 amendment to New York’s felon

disfranchisement statute — which narrowed §5-106 ’s application to people who were

incarcerated or on parole — somehow “severed the purely regulatory aspect of the

disenfranchisement law,” Appellees’ Br. at 26, and transformed it into “a law tailored

'Appellants submit that, even if §5-106 were a punitive law, it would still fall

within Section 2’s reach to the extent that it nonetheless functions as voting

prerequisite or qualification.

8

only to punish persons convicted of serious crimes during the period of their sentence

of imprisonment.” I d 6

Notwithstanding Appellees’ assertion to the contrary, the original intent behind

the enactment of New York's felon disfranchisement law was not altered by the mere

passage of the 1971 amendment, which simply narrowed the class of people subjected

to the law. Indeed, as case law makes clear, such an alteration must satisfy a very

high standard, as it is a “rule long established that in a general revision by

codification the revised sections will be presumed to bear the same meaning as did

the original sections, unless an intent to change meaning is clearly and indubitably

manifested.” Peerless Casualty Co. v. IJ.S.. 344 F.2d 495, 496 (D.C. Cir. 1964)

(citing Fourco Glass Co. v. Transmirra Corp.. 355 U.S. 222 (1957) (emphasis added);

Ruth v. Eagle-Picher Company. 225 F.2d 572, 575 (10th Cir. 1955). Moreover, with

respect to statutory construction, “amending legislation is perceived as clarifying,”

not changing, as Appellees improperly suggest here, “an original statute’s intended

6 Though Appellees rely on the legislative history of the amendments to §5-106

to support their contention that such amendments superseded the original intent of

New York’s felon disfranchisement law, they have, not surprisingly, failed to note

that the legislative history of the subsequent 1973 amendment expressly refers to the

law as a “voting qualification.” See, e.g.. N.Y.S. Gov. Bill Jacket 1973, 679 (Memo

Re: 1973 Proposed Amendment, May 2, 1973 to Michael Whiteman from Eric Seff:

“This bill further liberalizes from the voting qualification a convicted felon whose

sentence consists of a fine or probation or conditional discharge.”)(emphasis added).

9

meaning when a conflict of statutory interpretation has arisen.” Porter v. Comm, of

Internal Revenue. 856 F.2d 1205, 1209 (8th Cir. 1988); see also In re Adams. 761

F.2d 1422, 1426-27 (9th Cir. 1985). Finally, when considering amendments to

legislation, a court “must read the Act as a whole . . . [and should not] ignore the

‘common sense, precedent, and legislative history.’” Foxhall Realty v. Telecomm.

Serv., 156 F.3d 432, 437 (2d Cir. 1998) (quoting FTC v. Jantzen. Inc.. 386 U.S. 228,

235 (1967)).

In the instant case, Appellees’ unsupported argument that New York’s

decidedly regulatory felon disfranchisement statute was transformed into a punitive

one by virtue of the 1971 amendment is woefully insufficient under each of the tests

articulated above. Appellees provide no evidentiary articulation — “clearly,”

“indubitably” or otherwise — that the 1971 amendment was enacted to replace the

original intent behind the enactment of New York’s felon disfranchisement law.

Without this showing, the 1971 Amendment is presumed under Peerless Casualty to

bear the same meaning as the original enactment. Moreover, under Porter, the 1971

amendment can rightly be interpreted as a clarification, not alteration of, the original

enactment of New York’s felon disfranchisement statute — an interpretation that is

consistent with precedent and common sense. For these reasons, Appellees’

10

arguments fail to overcome this Court’s ruling in Green and the obvious fact that New

York’s felon disfranchisement statute is regulatory, not punitive, in nature.

II. SECTION 2’S APPLICABILITY TO §5-106 IS FIRMLY AND

INDEPENDENTLY AUTHORIZED BY THE FIFTEENTH

AMENDMENT

In their opening brief, Appellants, along with certain amici, provide strong

support for Section 2’s applicability to §5-106 pursuant to the Fifteenth Amendment,

notwithstanding the Fourteenth Amendment’s explicit recognition of felon

disfranchisement. Hayden Appellants’ Opening Br., at 22-23; See afro Brief for

Plaintiff-Appellant In Banc (“Muntaqim Opening Br.), at 47-49; En Banc Brief of

the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law and the

University of North Carolina School of Law Center for Civil Rights as Amici Curiae

Supporting Plaintiff-Appellant Jalil Abdul Muntaqim and in Support of Reversal, at

2-22. The Appellees’ cursory attention to this argument fails to rebut the fact that the

Fifteenth Amendment provides an independent source of Congressional authority for

the Voting Rights Act, and thus Section 2 ’s application to §5-106.

As the Supreme Court has noted, the primary purpose of the VRA is to

“enforce the fifteenth amendment to the Constitution of the United States.” Chisom

v. Roemer, 501 U.S. 380, 383 (1991). See afro S. Rep. No. 97-417, at 27, 39 (1982)

11

(invoking both the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendment enforcement powers to

amend Section 2 of the VRA). The Fifteenth Amendment, which provides a broad

right to be free from racial discrimination, contains no exemption for felon

disfranchisement. Indeed, the legislative history of the Fifteenth Amendment reveals

that Congress considered, but repeatedly rejected, proposed versions of the Fifteenth

Amendment that would have explicitly permitted states to disfranchise persons

convicted of felonies. Cong. Globe, 40th Cong., 3d Sess., 1012-13, 1041 (1869)

(rejecting by a wide margin two versions of the Fifteenth Amendment proposed by

Representative Warner that sought to incorporate felon disfranchisement language).

The text of the Fifteenth Amendment that finally passed both Houses of Congress

made no reference to felon disfranchisement.

Indeed, the Fifteenth Amendment, which was enacted a year and a half after the

Fourteenth Amendment, and supersedes that Amendment, expressly bans

disfranchisement on account of race.7 The Fifteenth Amendment does not import,

'Contrary to the Appellees’ assertion, Appellees’ Br., at 31 n.14, Havden

Appellants do not argue that the Fifteenth Amendment repeals the Fourteenth

Amendment, but rather assert that the Fifteenth Amendment provides an independent

source of protections greater than those afforded by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Moreover, while the Court in Richardson v. Ramirez. 418 U.S.24 (1974), relied on

Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment in addressing felon disfranchisement, the

Court did not conduct any analysis of Congress’ enforcement powers pursuant to the

Fifteenth Amendment.

12

either expressly or implicitly, the exemption of felon disfranchisement contained in

Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment. Thus, even if there are limits on Section

2 of the VRA’s applicability to felon disfranchisement because of that Amendment's

reference to criminal disfranchisement, which Appellants do not concede, Congress’

power to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment includes the ability to require New York

to discontinue enforcement of §5-106, which discriminates against people with felony

convictions on the basis of race.

III. FELON DISFRANCHISEMENT INTERACTS WITH THE

RACIAL BIAS THAT EXISTS IN NEW YORK’S

CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM TO DENY AND

UNLAWFULLY DILUTE APPELLANTS’ RIGHT TO

VOTE ON ACCOUNT OF RACE.

A. Bias in the Criminal Justice System

In their opening brief, and in response to this Court’s inquiries, Appellants set

forth several types of proof that would be required to establish their vote dilution

claim under the Voting Rights Act. In addition to showing that New York Election

Law §5-106 has a disparate impact on Blacks and Latinos, Appellants would be

required to show, under the totality of circumstances analysis, that felon

disfranchisement intersects with disparities in the criminal justice system to yield a

13

disparate impact in its application. Havden Appellants’ Opening Brief, at 30-31.

Appellants proffered a non-exhaustive discussion of the types of evidence that would

support a totality of circumstances finding. Id , at 30-39. Appellants agree with

Appellees that, because the district court decided this case on a motion for judgment

on the pleadings and thus did not consider any of the evidentiary questions that this

Court raises, these matters should be determined upon a remand to the district court.

Appellees’ Br., at 54 n.25. That said, Appellees’ preliminary assessment of the types

of proof necessary to establish a Voting Rights Act claim falls short in a number of

areas.

First, Appellees’ assertion that withholding the vote from persons with felony

convictions constitutes a de minimus injury since felons are allegedly less likely to

vote and, if they do, are likely to vote for losing candidates is a perverse assessment

of the rights at stake in this action. See Appellees’ Br., at 60-61. The Voting Rights

Act guarantees that all citizens be afforded an equal opportunity to elect candidates

of their choice — whether the candidates so chosen are successful or not. Moreover,

Appellees failed to fairly characterize the studies they relied upon and skewed the

purported propositions that the studies allegedly support.

For example, Appellees cite and rely upon the research of Christopher Uggen

and Jeff Manza, Democratic Contraction? Political Consequences of Felon

14

Disfranchisement in the United States. 67 Am. Soc. Rev. 777, for the proposition that

minority preferred candidates in heavily minority districts would likely win in an

election without the votes of the currently disfranchised felons. Appellees’ Br., at 58-

59. In fact, however, Uggen and Manza assert that a preferred minority candidate in

a contested primary election is less likely to win without the votes of people with

felony convictions. Uggen and Manza, 67 Am. Soc. Rev. at 796 n. 17. The same

Uggen and Manza study is also cited to support Appellees’ argument that currently

disfranchised voters are unlikely to vote in significant numbers, and thus would have

no impact upon elections. Appellees’ Br., at 60-61. In reality, Uggen and Manza did

not conclude that people with felony convictions would vote less than their non-felon

counterparts, and instead noted that “[a]ithough non-felon voters resemble felons in

many respects, we cannot be certain that the experience of criminal conviction itself

may not suppress (or conversely, mobilize! political participation.” Uggen and

Manza, 67 Am. Soc. Rev. at 796 (emphasis added). Significantly, Uggen and Manza

hypothesize that the political impact would be greater in local elections if people with

felony convictions were permitted to vote, asserting that “it is likely that such impact

is even more pronounced in local or district-level elections, such as House, state

legislative, and mayoral elections.” Id.

15

Second, Appellees’ cursory review of the substantial, publicly-available

research on racial bias in New York’s criminal justice system is curiously selective.

Missing from the Appellees’ discussion ofbias in its criminal justice apparatus is the

New York Attorney General’s commissioned report, entitled The New York Citv

Police Department’s “Stop & Frisk” Practices. Office of the Attorney General of the

State of New York, Civil Rights Bureau (1999), which tracks racial bias at the first

point of contact between New York Police and minority citizens. See En Banc Brief

in Support of Plaintiff-Appellant Jalil Abdul Muntaqim, a/k/a Anthony Bottom, and

in Support of Reversal, on Behalf of Amici Curiae NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc., Community Service Society of New York, and Center for

Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College ("Hayden Counsel Amicus Br.”), at

15-16. Nor do Appellees address the types of evidence of racial bias outlined in the

Hayden Appellants’ Opening Br., at 33-35, including numerous studies which show

that relative to Blacks’ and Latinos’ crime participation, the rates of stops, arrests and

criminal processing they incur is much higher than for Whites; measures of police

activity, showing again that even controlling for crime rates, the allocation of police

resources and staff and their activity indicate how minority communities are

disproportionately targeted; and measures of the concentration of incarceration that

16

show how incarceration in minority communities reinforces racial disparities in the

criminal process.

Instead of dealing squarely with the force of the Havden Appellants’ evidence

of bias in New York’s criminal justice system, Appellees attempt to reduce the import

of that research by asserting that it must comply with stringent statistical standards

(citing civil rights cases outside of the Voting Rights Act context) in order to be

probative. Once again Appellees ignore the weight of the research already available,

all of which made statistically significant findings, that lays a strong foundation for

any other proof that Appellants present on remand. See Cassia Spohn, U.S. Dep’t

of Justice, Thirty Years of Sentencing Reform: The Quest for a Racially Neutral

Sentencing Process (finding that race and ethnicity are strong determinants in

sentencing); New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services Study. 1995

(finding statistically significant differentials in detention rates for minorities and

whites). Given the availability of studies evidencing racial bias in New York’s

criminal justice system, Appellants can meet the rigorous standards of social science

evidence that courts routinely rely upon in assessing discriminatory impact.

In sum, Havden Appellants and Appellees agree that the record in the Havden

case does not allow this Court to fully assess the weight of Appellants’ evidence in

support of their Voting Rights Act claim. But Havden Appellants have clearly

17

provided this Court with enough statistical evidence to determine that remand is

appropriate, thus allowing a district court to fully evaluate their potential claims.

B. Proof Under the Senate Factors of Section 2

The Hayden Appellants agree with the Appellees that no one Senate Factor in

the Senate Judiciary Committee Report accompanying the amended Section 2, S. Rep.

at 28, U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News 1982 at 206, is dispositive under Section 2’s

flexible approach. Appellees’ Br., at 71. As previously briefed by the Hayden

Appellants, a number of Senate Factors can yield probative evidence that would assist

a court on remand, including whether minority voters bear the effects of

discrimination in education, employment and health that negatively impacts their

political participation, Hayden Counsel Amicus Br., at 23-25; the extent to which the

state has used voting practices or procedures that enhance opportunities for

discrimination, id, at 36; racial appeals in voting, id.; access to candidate slating

processes, id.; the extent to which minority candidates are successful, id.; and lack of

responsiveness by elected officials to the needs of minority voters, id. at 38-39.

Among the Senate Factors that accompany Section 2, proof is permitted

regarding “whether the policy underlying the state or political subdivision’s use of

such voting qualification, prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice or procedure

18

is tenuous.” S. Rep. No. 97-417 at 28-29 (1982) reprinted in 1982 U.S.C.A.N.N. 177,

179. Appellees, however, have exaggerated their newly-found penological purpose

of retribution and punishment behind New York’s felon disfranchisement laws in an

attempt to foreclose the very broad inquiry that Section 2 invites. Appellees’ Br., at

68-70. But New York rejects punishment for the sake of punishment as a valid

purpose of its penal system. The general purposes of the penal code of New York

attest to deterrence, rehabilitation and incapacitation as the goals of its criminal law.

Specifically, the penal code of New York seeks to “insure the public safety by

preventing the commission of offenses through the deterrent influence of the

sentences authorized, the rehabilitation of those convicted and their confinement

when required in the interests of public protection.”

Consistent with this legislative policy is the case of People v. Oliver. 1 N.Y.

2d 152 (1956), where the court recognized that punishment has only three goals in

New York: deterrence, incapacitation and rehabilitation. In that case, the court noted

that “the punishment or treatment of criminal offenders is directed toward one or

more of three ends: 1) to discourage and act as a deterrent upon future criminal

activity, 2) to confine the offender so that he may not harm society, and 3) to correct

and rehabilitate the offender. There is no place in the scheme for punishment for its

19

own sake, the product simply of vengeance or retribution.” 1 N.Y. 2d at 160

(emphasis added).

Accordingly, a broad inquiry under the Voting Rights Act, including an

assessment of the Senate Factors will invite close scrutiny of the tenuousness of the

Appellees’ insistence on depriving fundamental citizenship rights to persons with

felony convictions. In this regard, the Havden Appellants adopt and incorporate by

reference En Banc Brief Submitted on Behalf of Certain Criminologists as Amici

Curiae in Support of Appellants and in Support of Reversal, at 8-22, which asserts

that depriving Havden Appellants of the vote does not serve any legitimate criminal

justice objective.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons and authorities, and for those previously set forth in

the Havden Appellants’ Opening Br., this Court should reverse the judgment of the

district court in part8 and remand this case for further proceedings.

8Because the Court has excluded from consideration in this consolidated appeal

the other bases for appeal in Havden v. Pataki. No. 04-3886-PR, the Havden

Appellants seek only reversal of the district court’s dismissal of its VRA claims in

this appeal. Notwithstanding this specific limitation, the Havden Appellants do not

waive any of the grounds for and arguments in support of the appeal of the remainder

of their claims.

20

RULE 32 (a) (7) (C) CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

The undersigned hereby certifies that this brief complies with the type-volume

limitations of Rule 32 (a) (5) (A) of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure.

Relying on the word count of the word processing system used to prepare this brief,

I hereby represent that the En Banc Reply Brief of Flavden Appellants contains 4,616

words, not including the corporate disclosure statement, table of contents, table of

authorities, and certificates of counsel, and is, therefore, within the 7,000 word limit

set forth under Rule 32 (a) (7) (B) (ii).

Janai S. Nelson, Esq.

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2237

jnelson@naacpldf.org

Dated: May 13,2005

21

mailto:jnelson@naacpldf.org

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify under penalty of perjury pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1746 that, on May

13, 2005, I caused true and correct copies of the foregoing En Banc Reply Brief for

Havden Plaintiffs-Appellants to be served via United States Postal Service first-class mail

to the following attorneys:

Jonathan W. Rauchway, Esq.

William A. Bianco

Gale T. Miller

Davis Graham & Stubbs LLP

1550 Seventeenth Street

Suite 500

Denver, Colorado 80202

J. Peter Coll, Jr.

Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP

666 5th Avenue

New York, New York 10013-0001

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

Muntaqim

Elliot Spitzer

Attorney General o f the State o f New York

Caitlin J. Halligan

Solicitor General

Michelle M. Aronowitz

Deputy Solicitor General

Julie M. Sheridan

Gregory Klass

Benjamin Gutman

Assistant Solicitors General

New York State Office of the Attorney

General

120 Broadway - 24th floor

New York, New York 10271-0332

Patricia Murray

First Deputy Counsel

New York State Board of Elections

40 Steuben Street

Albany, New York 12207-0332

Attorneys for the Defendants-Appellees

By:

Jc

N

NkhoA

nai S. Nelson, Esq.

A.ACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

inelson@naacpldf.org

mailto:inelson@naacpldf.org