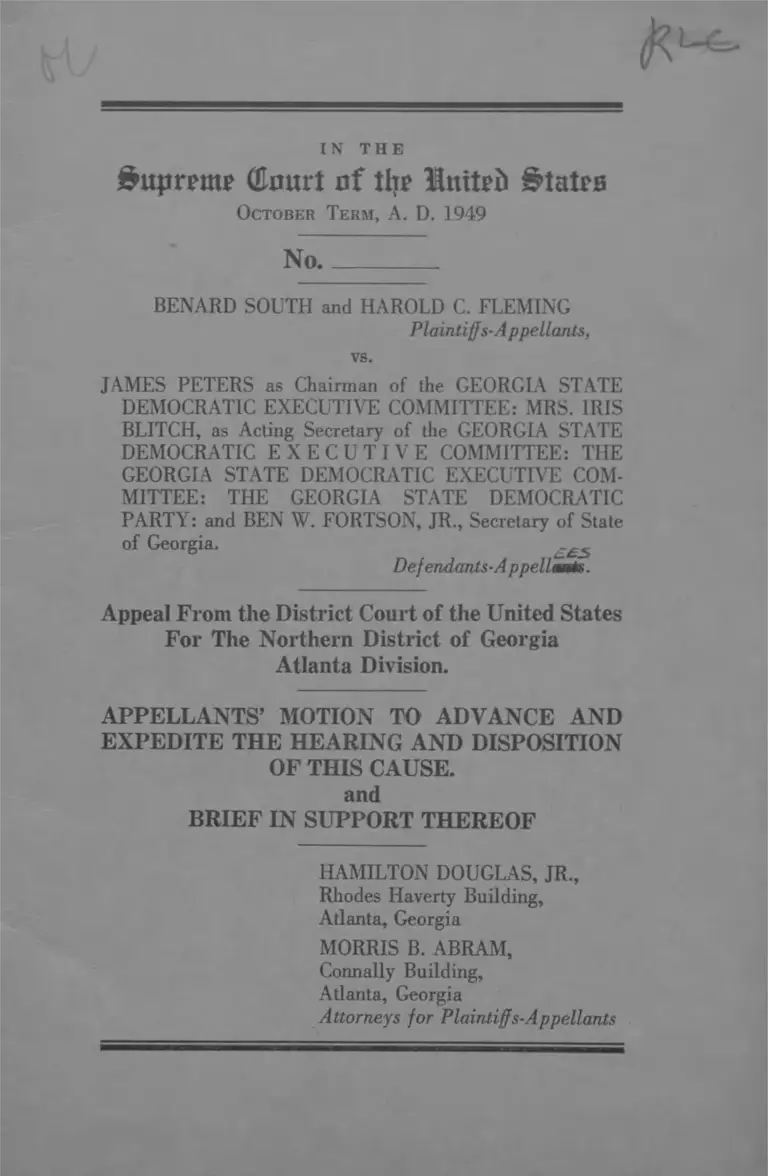

South v Peters Motion to Advance and Expediate Hearing and Disposition

Public Court Documents

March 21, 1950

20 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. South v Peters Motion to Advance and Expediate Hearing and Disposition, 1950. eb61c9d9-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b17fc9e3-af0c-45d2-9157-d004a7acd4c5/south-v-peters-motion-to-advance-and-expediate-hearing-and-disposition. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

(Urntri nf tf|? £>tatra

October Term, A. D. 1949

No___________

BENARD SOUTH and HAROLD C. FLEMING

Plaintiffs-A ppellants,

JAMES PETERS as Chairman o f the GEORGIA STATE

DEMOCRATIC EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE: MRS. IRIS

BLITCH, as Acting Secretary o f the GEORGIA STATE

DEMOCRATIC E X E C U T I V E COMMITTEE: THE

GEORGIA STATE DEMOCRATIC EXECUTIVE COM

MITTEE: THE GEORGIA STATE DEMOCRATIC

PARTY: and BEN W. FORTSON, JR., Secretary o f State

o f Georgia. ££S

Defendants-A ppellumks.

Appeal From the District Court of the United States

For The Northern District of Georgia

Atlanta Division.

APPELLANTS’ MOTION TO ADVANCE AND

EXPEDITE THE HEARING AND DISPOSITION

OF THIS CAUSE,

and

BRIEF IN SUPPORT THEREOF

HAMILTON DOUGLAS, JR.,

Rhodes Haverty Building,

Atlanta, Georgia

MORRIS B. ABRAM,

Connally Building,

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

NOTICE AND PROOF OF SERVICE

Please take notice that on 21st day o f March, 1950, or as

soon thereafter as the convenience o f the Court will permit,

we shall present to the United States Supreme Court in

Washington, D. C., in the above-entitled cause, a Motion to

Advance and Expedite the Cause and a Brief in Support

Thereof, a copy o f which is served upon you herewith. At

which time you may appear or be represented by counsel if

you so see fit.

Hamilton Douglas, Jr.

Morris B. A bram

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellants

Received true and exact copies o f the Motion to Advance

and Expedite the Cause and a Brief in Support Thereof

and o f this Notice and Proof o f Service this_______ day of

March, 1950.

Eugene Cook B. D. Murphy

Attorney-General, State of

Georgia

Atlanta, Georgia

C. Baxter Jones M. F. Goldstein

Macon, Georgia Atlanta, Georgia

M. H. Blackshear, Jr .

Asst. Attorney-General,

State of Georgia

i

AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE

....................................................................... . being duly sworn,

deposes and says that he is one of the Attorneys for Appel

lants in the above entitled cause, that he gave notice of the

Motion to Advance and Expedite the Cause by sending on

March 18, 1950, a telegraphic notice of said Motion to

each attorney o f record and by depositing on March 18,

1950, in a United States Mail Box in the City o f Atlanta a

copy o f said Motion addressed to each o f the attorneys of

record.

Subscribed and sworn to before me by......... ........................

__________ ________________, who is to me personally known,

this......................day of March, 1950.

Notary Public

IN THE

£>uprpmp (Court of tfyr llnttpb £>tatpa

October Term, A. D. 1949

No.

BENARD SOUTH and HAROLD C. FLEMING

Plaintiffs-A ppellants,

JAMES PETERS as Chairman of the GEORGIA STATE

DEMOCRATIC EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE: MRS. IRIS

BLITCH, as Acting Secretary o f the GEORGIA STATE

DEMOCRATIC E X E C U T I V E COMMITTEE: THE

GEORGIA STATE DEMOCRATIC EXECUTIVE COM

MITTEE: THE GEORGIA STATE DEMOCRATIC

PARTY: and BEN W. FORTSON, JR., Secretary o f State

o f Georgia.

Appeal From the District Court of the United States

For The Northern District of Georgia

Atlanta Division.

APPELLANTS’ MOTION TO ADVANCE AND

EXPEDITE THE HEARING AND DISPOSITION

OF THIS CAUSE.

2

BASIS OF MOTION

This motion is made in accordance with Rule 20, para

graph 3, o f the Rules o f this Court.

PURPOSE OF THIS MOTION

On June 28th, 1950, near the date when this Court

customarily adjourns for the Summer recess, the Democratic

Party o f Georgia is planning to hold a primary for statewide

offices. Candidates successful in that primary will, if the

unvarying practice o f more than 75 years holds true, serve

as Governor o f the State, United States Senator from the

State, and in many other offices including the highest judi

cial posts.

The primary will be conducted by the County Unit System

o f consolidating votes. This means that after the ballots of

all voters are cast and counted, the results o f the primary

election will be determined by the defendants giving effect

to the law under constitutional attack. (Georgia nominations

by County Units Act o f August 14,1917, Georgia Laws 1917,

pp. 183-189.) Under this law the defendants will determine

the outcome o f the primary by diluting the votes which

plaintiffs intend to cast. By this arbitrary method the

defendants will count the votes in Chattahoochee County,

Georgia, as being worth perhaps 122 times as much as the

votes o f plaintiffs. In 45 Counties o f Georgia voters will

be accorded twenty or more times the voting influence of

plaintiffs. On a state average, voters outside Fulton County

will be given 11.5 times more franchise than the plaintiffs.

No basis in experience, practicality or necessity supports

the gross discrimination against plaintiffs which is vividly

portrayed in the dissenting opinion below: “ The vote o f a

citizen living on one side o f Moreland Avenue in Atlanta,

3

DeKalb County, equals five o f his neighbors directly across

the street in Atlanta, Fulton County.”

The system discriminates to a less degree against the

voters o f every single county in the state save those who

live in the smallest county of all.

This discrimination complained o f is not in reference to

representation, but in the fact that having been permitted to

vote for an officer on the same basis as all other citizens,

and after the votes are counted, the defendants will deliber

ately and arbitrarily discount the value o f plaintiffs’ votes.

Citizens o f no other State in the Union are victimized by a

County Unit System. This case presents a matter sui generis,

generis.

TIMING OF THE SUIT

The bill below was for a declaration and injunction

declaring the discrimination against plaintiffs to be uncon

stitutional and preventing the defendants from employing

the County Unit System in consolidating returns, determin

ing victorious candidates, and in certifying them as such.

No injunction was sought against holding a primary election

nor attempting to overturn the results o f one already held.

The bill was filed January 25th, 1950, at the first indi

cations that a primary would be called, but actually six

weeks before the call. (Under Georgia law no primary need

actually have been held.) When the bill was filed, statute

required that if a primary were held it must occur on

September 13th, 1950. But after the filing o f this suit, the

Administration recommended and the Legislature enacted a

revision o f the law permitting the Party Executive Committee

to choose an earlier date. That Committee met on March

11, 1950, and pushed the primary forward almost three

months, so it will now be held on June 28th, 1950.

4

Unless the Court grants a motion to advance, these

plaintiffs cannot possibly have a final adjudication o f their

constitutional rights to have their votes properly valued in

the pending primary. A prior attempt to void the county

unit law was dismissed by this Court on account o f mootness

( Turman v. Duckworth, 329 U. S. 675). Plaintiffs are

pursuing now the course recommended in the District Court

decision in the Turman case in the sense that they brought

their bill before the primary. Indeed, they have not awaited

the call o f the primary as specifically recommended in the

Turman vs. Duckworth, 68 F. Supp. 744, 747, but ran the

risk o f prematurity by instituting suit even before the

primary was called.

As primaries have always been held in Georgia in the

summer or fall, it is improbable that any relief against the

deprivation o f plaintiffs’ rights can ever be afforded in this

Court without an advancement o f the case.

To be effective, relief in this case will be needed before

June 28th, 1950 (unless the defendant Committee again

advances the primary date). But no relief is required

until the actual day o f the primary election. For the only

relief sought is to prevent the consolidation o f votes and

the declaration and certification o f the results o f the election

on the county unit basis.

THIS MOTION

This motion is for such order o f this Court as will

advance and expedite the hearing and decision o f this cause

in light o f the emergency which the case presents. Specifi

cally appellants move:

(1 ) That this case be docketed in order that it may have

a hearing at the present term of this Court.

5

(2 ) That the time permitted by the Rules o f this Court

for accomplishing the following steps be constricted

so as to afford a decision from this Court which

can be known and enforced before the Democratic

Primary in Georgia scheduled to be held June 28th,

1950:

(a ) The time permitted under paragraph 3 o f Rule

12 for filing o f a statement in opposition to

appellants’ Statement o f Jurisdiction.

(b ) Time permitted by paragraph 3 o f Rule 7 for

filing o f a brief in opposition to any motion to

dismiss the appeal.

(c ) Time permitted under paragraph 1, Rule 27,

for filing appellants’ brief.

(d ) Time permitted under paragraph 4 o f Rule 27

for filing appellees’ brief.

(3 ) That the case here pending should be advanced for

argument ahead o f the order in which it might

normally be assigned for hearing and decision in

this Court.

(4 ) That the printing o f the Record in this case be expe

dited to prepare it for an advanced hearing, or in

lieu thereof that the appeal be heard on the type

written record certified to this Court by the Clerk

o f the District Court.

CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTIONS PRESENTED

This case presents to the Court three constitutional ques

tions:

(1 ) Whether, considering the provisions o f the “ Equal

Protection Clause” o f the 14th Amendment, it is

allowable for a State arbitrarily to dilute the ballots

6

o f fully qualified voters so that some persons voting

for the same candidates as plaintiffs are accorded

122 times the voting power o f the plaintiffs, and all

other voters, on a statewide average, are accorded

11.5 times the voting influence o f plaintiffs in elect

ing that candidate. Whether this discrimination is

justified by an historic antagonism against urban

centers and a fear o f Negro, progressive and labor

votes in those centers; and whether geography o f

residence is a permissible basis for dilution o f one’s

ballot.

(2 ) Whether the abridgment o f a voter’s right to choose

a United States Senator by gross dilution o f his

ballot is a violation o f a Privilege and Immunity

o f a Citizen o f the United States within the meaning

o f the 14th Amendment.

(3 ) Whether the choice by County Units o f a United

States Senator in the Georgia Democratic Primary

is a violation o f the 17th Amendment to the Con-

sitution o f the United States, guaranteeing to plain

tiffs the right to choose Senators by a vote o f the

people.

COURSE OF PROCEEDINGS BELOW

The complaint seeking injunctive and declaratory relief

was filed on January 25, 1950. The case was originally

assigned for hearing on February 17th, 1950, before a

three-judge court. The hearing was postponed at the request

o f Counsel for the Appellees and the trial was held on

February 24, 1950. At the conclusion o f the hearing,

Counsel for plaintiffs submitted a brief. Counsel for defend

ants requested two weeks for filing their brief. The Court

allowed but one week. On March 15th, the decision o f the

Court was announced. The majority denied all relief sought,

7

but one judge, dissenting, held that plaintiffs were entitled

to injunctive and declaratory relief on all the constitutional

grounds urged. Two days after the entry o f the final order

in this cause, plaintiffs filed their appeal.

WHEREFORE, appellants pray that this their motion to

advance be inquired into by the Court and the relief herein

specifically sought be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Hamilton Douglas, Jr.

Morris B. A bram

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

8

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF THE MOTION TO ADVANCE

INTRODUCTION

The nature o f the case and the questions presented are

set out in the motion herein. A fuller presentation o f the

same is to be found in plaintiffs’ Statement o f Jurisdiction.

ARGUMENT

I.

What this Case is Not

This is not a Colegrove v. Green (328 U. S. 549) situa

tion. There is no necessity for this Court to remap the State

politically; no question of interference with Congress’ power

to control the manner o f holding elections; no claim of

wrong against a state as a polity; no remedy sought against

unequal representation o f a county in the legislature. Plain

tiffs in this case complain that they are not being allowed an

equal vote with every other voter who is to be governed by

the successful candidate. In the Colegrove case, each voter

had an equal voice in determining the candidate who was

to represent him.

This is not a case like MacDougall v. Green (335 U. S.

281). The relief sought here will not interrupt a pending

election so as to invalidate absentee and soldier vote ballots.

The injunction prayed would in no way interfere with any

stage o f the voting and in fact would become operative only

at the stage where the defendants proceeded to dilute the

effectiveness o f the whole ballots which the plaintiffs are per

mitted to cast and which are required by law to be counted.

Relief sought would disfranchise none but would enfranchise

all equally.

Furthermore, the degree o f discrimination in the Mac

Dougall case (which is thought to be o f some decisiveness

in the holding) does not remotely approach the situation

9

against'which these plaintiffs seek relief. On the facts o f

the MacDougall case, this Court held: . . the State is en

titled to deem this power not disproportionate.” (Emphasis

supplied.) As related to Cook County, the facts in the

MacDougall case showed that 61% o f the political initiative

could come from the subdivision with 52% o f the popula

tion. But these plaintiffs show this Court that (NOT AS A

MATTER OF POLITICAL INITIATIVE) but in the actual

choice o f state officers in the only effective election, they are

practically disfranchised as compared to citizens in other

counties.

There may be some reasonable basis for the requirement

in the MacDougall case that political initiative spring from

a source wide enough to prevent the splintering o f the elec

torate. But the County Unit System does not purport to

deal with that problem. The raison d’etre o f the County Unit

System is the same as its effect: To discriminate against

plaintiffs and other urban voters.

In the dissenting opinion filed below in this case, Judge

Andrews notes another difference with the MacDougall case:

“ . . . proportionately no more city folks vote [in Georgia

Democratic primaries] than do country people. This dis

poses o f the notion, tacitly approved in MacDougall v. Green,

that difficulty in getting to the polls should be recognized

here as a makeweight in justifying a rank discrimination

based on place o f residence.”

This is not like Turman v. Duckworth (329 U. S. 625).

This case is not now moot. The primary is scheduled for

June 28, 1950. Nor does the pending case ask the Court to

upset an election already held.

Plaintiffs are not attaacking the right o f Georgia to

establish the qualifications requisite for electors within the

State. Plaintiffs are, however, insisting that once Georgia

10

has established the criteria for qualifications o f an elector,

all who qualify must be treated equally. Plaintiffs are not

attacking the Presidential Electoral College, nor the equal

vote in the United States Senate. The Federal Government

is in no way enjoined or commanded by the 14th Amend

ment. Plaintiffs are not attempting to use judicial power to

correct malproportions in legislative representation. This

Court is not being asked to juggle boundary lines and accom

modate and adjust them to the influx o f the new born and

the efflux o f the dead and the emigrant. Plaintiffs are merely

asserting that one vote is not 122 votes and are requesting

the Court to judicially declare that fact and grant injunctive

relief upon it.

n.

What this Case is

There is but one County Unit System in the United

States. The Tennessee Legislature attempted to foist the

system on that state but the attempt was struck down by the

Supreme Court o f Tennessee in a unanimous decision apply

ing some o f the Constitutional principles urged here. (See

Gates v. Long, 172 Tenn. 471, 113 SW (2 ) 388.) The

Georgia County Unit System is purely and simply a delib

erate method for disfranchising certain classes o f citizens

whose influence is thought to be pernicious.

The degree o f discrimination is unparalleled and is indi

cated by some o f the ratios already presented. Under the

holding o f the majority o f the Court below the ratio of

discrimination would be permissible state practice no matter

how far it might be carried. Yet, can a Court of Equity

which is zealous o f the right o f the franchise and the equality

of its protection permit the virtual cancelling out o f the

ballot by indirection?

11

in.

Judge Andrews who dissented below thoroughly weighed

the balance o f convenience which historically has determined

the issuance o f equitable relief. His conclusion was that the

injunction would be practical, effective and easy o f enforce

ment. He well summarized the consequences o f the issuance

o f the decree:

“ I am unable to find any unpalatable practical con

sequences to the granting o f an injunction in this case.

There will be no necessity for this Court to supervise

any election, an eventually upon which GILES v. HAR

RIS turned. The gross discrimination wrought by the

offending statute occurs after the votes have been cast

and counted by a method employed by the State Demo

cratic Executive Committee and its chairman and secre

tary. The effective application o f the discrimination to

the plaintiffs occurs when the nominees are placed on

the general election ballot by the Secretary o f State.

All o f these instruments o f discrimination are defend

ants here and an injunction forbidding their actions

under the offending statute will effectively end the

discrimination. The relief granted in RICE v. EL

MORE, supra, required o f the Court vastly greater

supervision o f the electoral process than is asked or

required in this case.

“ Granting o f injunctive relief will not bring about

any o f the practical consequences feared by the Court

in COLEGROVE v. GREEN, supra. No disruption of

a pending election will ensue. The only change which

will be effected is the method o f consolidating the vote

at the top level o f the Georgia Democratic Party. The

votes will be cast and counted in precinct, ward and

county without change or interruption. The Georgia

General Assembly need take no action to provide an

12

alternative method o f determining nominees, for under

Georgia law the responsibility will revert to the party.

Defendants in argument and brief have relied heavily

upon two other suits which involved attacks upon the

Georgia County Unit System, TURMAN v. DUCK

WORTH, 68 F. Supp. 744, and COOK v. FORTSON,

68 F. Supp. 624, both decided in 1946 by this Court.

The Supreme Court o f the United States dismissed

appeals on the grounds o f mootness, citing UNITED

STATES v. ANCHOR COAL COMPANY, 279 U. S.

812. TURMAN v. DUCKWORTH, 329 U. S. 675.

“ These cases have no application to the case at bar.

The District Court in each case based its decision on

COLEGROVE v. GREEN, supra. As discussed above,

that case is authority only for the discretionary power

o f equity to deny relief under the circumstances o f that

case. In the earlier county unit cases, the plaintiffs

sought to overturn a completed primary election after

they had participated in the primary without objection,

on the grounds that candidates for whom they had

voted received a plurality o f votes cast in their respec

tive contest but were not declared nominees o f the

party. The candidates themselves did not complain and

one o f them even went so far as to intervent to ask that

the suit be dismissed.

“ The consequences o f injunctive relief in those two

cases presented practical problems in the exercise of

the Court’s discretionary powers not perceivable in the

instant case, and view in this light the District Court

decisions in them are not precedent for deniel o f relief

here.”

13

IV.

Other Relief

There is no practical hope that the vicious discrimination

against appellants can ever be remedied otherwise than

through the intervention o f this Court. The Georgia Legis

lature is composed so as to reflect precisely the discrimina

tion o f the county unit system.

This vast disproportion o f legislative power in rural

counties (for which plaintiffs seek no relief) insures that

the County Unit System will endure. Indeed, the last Gen

eral Assembly by the required 2 /3 vote proposed, and there

is being submitted to the people in the General Election of

November, 1950, a constitutional amendment to extend the

County Unit System into future General Elections.

As legislative relief is hopeless, so is constitutional relief

through amendment. All constitutional initiative lies with

the legislature— with 1 /3 o f either house able to stifle any

proposal.

So even if the people strongly will the end of the County

Unit System, they are powerless to accomplish it.

V.

Implications of the County Unit System

Since Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 629, many Southern

legislatures have been groping for a means o f keeping the

Negro disfranchised. These attempts have been recorded in

a steady stream o f decisions. In Alabama the Boswell

Amendment was the method o f attempted circumvention.

The effort was ill-fated. Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872.

South Carolina made two tries. Both failed. Elmore v. Rice,

72 F. Supp. 516, aff. 165 Fed. (2 ) 387, cert. den. 338 U. S.

875; Brown v. Baskin, 78 F. Supp. 933.

Georgia had hopes. These were dashed in Chapman v.

14

King, 62 F. Supp. 639, aff. 154 F. (2 ) 460. But Georgia

still has in the County Unit System a most effective and, so

far, the most constitutionally promising method o f Negro

disfranchisement. It was argued below, and indeed the fact

is judicially known and cannot be disputed, that in Georgia

the Negro in the small rural county is, through intimidation,

threats, economic reprisal and occasional lynchings, pre

vented from voting in any numbers. (In Wrightsville, John

son County, Georgia, four hundred Negroes were registered

to vote in a local primary in 1948. The night before the

primary a Ku Klux Klan parade was held and a cross burned

on the Court House lawn. Not one Negro voted the following

day.) In the cities the Negroes do vote. But these votes, like

white city votes, are sterilized by the County Unit System.

The County Unit System thus “ heavily disfranchises the

Negro population. Almost half o f Georgia’s Negroes live

in the most populous counties. Here the Negro vote has

been large. But the County Unit System cancels the Negro

vote in these counties— the only counties where the Negroes

have been able to vote in important numbers. In small

counties, where any single vote is at a premium, Negroes

generally have been denied the franchise.” New South pub

lished by the Southern Regional Council, Atlanta, Ga., Vol.

4, Nos. 5&6, 1949.

The same point was referred to in the hearing below by

expert witness, Doctor Linwood Holland, Associate Professor

o f Political Science o f Emory University, Atlanta, Ga., and

author o f The Direct Primary in Georgia, published by the

University o f Illinois Press:

“ . . . your Negro vote is predominately in your

urban areas, it means he would be prevented.”

If the Georgia County Unit System is permissible state

practice, it will come to replace the white primary as the

15

instrument o f Negro disfranchisement throughout those areas

o f the South which are still determined to find a means of

preventing the black man from voting.

The Chattanooga (Tenn.) Times lead editorial o f March

16, 1950, in commenting on the decision below in this

case, summed up these implications o f the County Unit

System:

“ But the U. S. Supreme Court is likely to consider it

from another viewpoint. The county unit system of

Georgia is the last loophole remaining whereby the U. S.

Supreme Court decision that there must be no dis

crimination because o f race in Southern primaries is

defeated.

“ In the Georgia rural counties, Negroes theoretically

have the right to vote, but they are intimidated and in

many cases they dare not exercise their right.

“ The danger is that if this loophole remains, the

same technique may be copied in other states to invali

date the U. S. Supreme Court decision. . . .

“ At any rate, a U. S. Supreme Court ruling on the

county unit system is o f importance to the whole South,

for the county unit system discriminates not only against

city voters in Georgia, but it is the system by which

the Supreme Court ruling on the right o f all citizens to

vote is dodged.”

VL

Precedents for Granting the Motion to Advance

This is a case, o f public gravity and importance. In other

cases this Court has granted and disposed o f cases on motions

to advance as provided in the Rules o f the Supreme Court.

In MacDougall v. Green, supra, the Motion to Advance

was served on Counsel opposite on October 12th, 1948, the

16

cause was argued on October 18th and the decision rendered

three days later.

In Wood v. Broom, 287 U. S. 1, an appeal was filed in

this court on October 2. Briefs were submitted on October

11 and oral argument was heard on October 13. The Court

announced its decision on October 18.

In McPherson v. Blacker, 146 U. S. 1, a motion to

advance the cause was filed on the second day o f Term,

October 11, and was granted at once. The cause was heard

on that day and the decision rendered on October 17.

Plaintiffs respectively submit to the Court that there are

the most compelling reasons for granting this Motion to

Advance, and they earnestly pray that their motion be

favorably considered.

PRAYER OF THE MOTION

For the reasons indicated above, appellants respectfully

move this Court for such order o f this Court as will advance

and expedite the hearing and disposition o f this cause at

the earliest time convenient to this Court.

Respectfully submitted,

Hamilton Douglas, Jr.

M orris B. A bram

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants