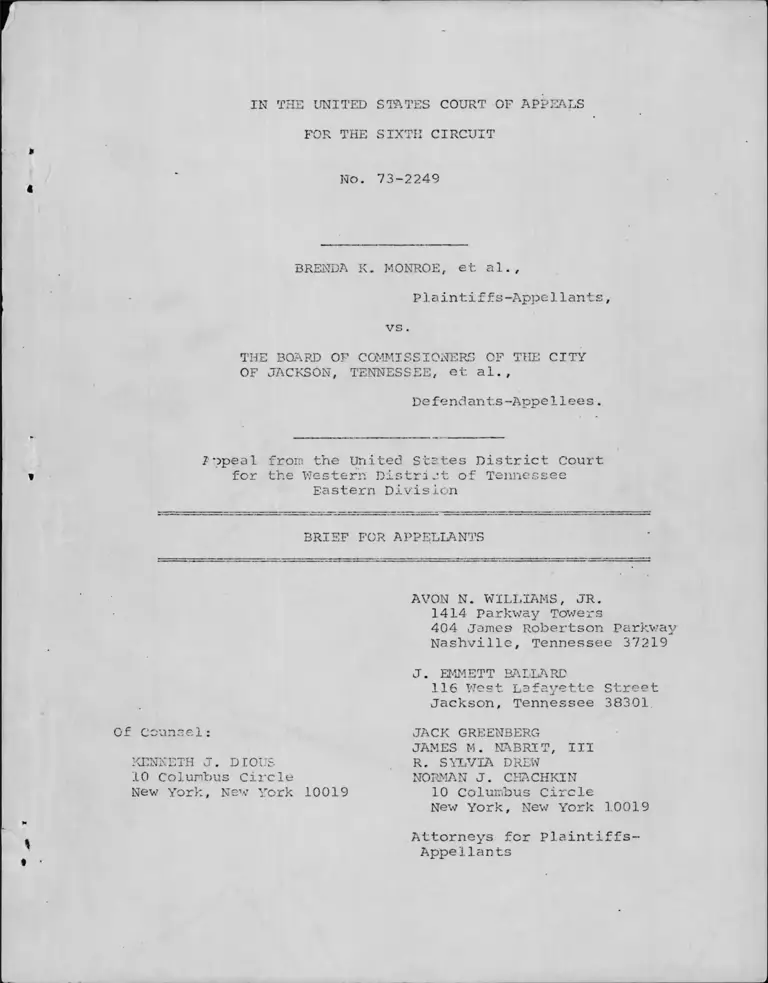

Monroe v. City of Jackson, TN Board of Commissioners Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Monroe v. City of Jackson, TN Board of Commissioners Brief for Appellants, 1973. 5d3cc423-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b1a70bea-cc8a-471f-a859-e8660bc1e4fd/monroe-v-city-of-jackson-tn-board-of-commissioners-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

r

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

*

« No. 73-2249

BRENDA K. MONROE, et al.,

Plaintiff s-Appe Hants,

vs.

THE BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF THE CITY

OF JACKSON, TENNESSEE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Tennessee

Eastern Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

s

* •

Of Counsel:

KENNETH J. DIOUS

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.1414 Parkway Towers404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

J. EMMETT BALLARD116 West Lafayette Street

Jackson, Tennessee 38301.

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

R. SYLVIA DREW

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appellants

I N D E X

Page

Table of Authorities................................ ii

Issues Presented for Review ........................ 1

Statement

A. History of the Case ........................

B. Desegregation of the Jackson Elementary

Schools .................................... 4

1. The 1972-73 Elementary School Zones . . . 6

2. The Board's 1973-74 Proposals .......... 8

3. Plaintiffs' P l a n ...................... 10

4. The District Court's Baling ............ 12

C. Attorneys' Fees ............................. 15

ARGUMENT

I. The Board Failed To Carry Its Burden Of

Showing That The Decision To Close South

Jackson Elementary School Was Based Upon

Objective, Non-Racial Factors. The Evidence

Demonstrated Inconsistent Application Of

Standards To Black And WThite School Facilities

A. Review Of The District Court's Decision

Permitting The Board To Close South

Jackson Is Not Governed By Rule 52 . . . 16

B. Racial Discrimination In The

Desegregation Process .................. 18

C. Adequate Non-Racial Justification

For Closing The South Jackson

Elementary School Was Not Shown By

Defendants............................ 21

1. Condition of the facility........ 23

2. Location of the school............ 25

i

Page

3. Declining enrollment and

uneconomical operation.......... . . 27

4. Segregated neighborhood .......... 30

5. Other f a c t o r s .................... 31

6. Unequal burden.................... 32

7. S u m m a r y .......................... 33

II. Whatever The Fate Of South Jackson Elementary

School, The Case Must Be Returned To The

District Court To Complete The Process Of

Desegregating Jackson's Elenentary Schools . . 34

III. The District Court Must Provide An Oppor

tunity For The Submission Of Evidence And

Make Finding® In Order To Permit Review Of

Its Counsel Fqe A w a r d ...................... 40

Conclusion.......... ................................ 42

Appendix "A" — Decision of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc.

(January 21, 1974)

Table of Authorities

Cases;

Adams v. School Dist. No. 5, Orangeburg, 444 F.2d

99 (4th Cir. 1971) ............................ 40

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396

U.S. 19 (19§9) 18n

Bell v. West Point Municipal Separate School Dist.,

446 F.2d 1362 (5th Cir. 1971).................. 20n

Bradley v. Milliken, 484 F.2d 215 (6th Cir.),

cert, granted, 42 U.S.L.W. 3306 (Nov. 19, 1973) . 40n

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 472 F.2d

318 (4th Cir. 1972)............................ 42n

n

Page

Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk, 456 F.2d 943

(4th Cir.)/ cert, denied, 406 U.S. 905 (1972) . . 39

t Brice v. Landis, 314 F. Supp. 974 (N.D. Cal. 1969) . . 33

Brown v. Board of Educ. of Bessemer, 464 F.2d 382

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 981 (1972) . . 39

» Brown v. Board of Educ. of DeWitt, 263 F. Supp.

734 (E.D. Ark. 1966) .......................... 23

Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 429 F.2d

382 (5th Cir. 1970)............................ 23

Chambers v. Iredell County Bd. of Educ., 423

F.2d 613 (4th Cir. 1970) ...................... 23

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School Dist.,

467 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 413

U.S. 902, 922 (1973) ...................... . . 38

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 449 F.2d

493 (8th Cir. 1971), cert, denied, 405 U.S.

936 (1972) 39

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Reck, 426 F.2d

1035 (8th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 402 U.S.

952 (1971) 39

» Davis v. Beard of School Comm'rs of Mobile, 402

U.S. 33 (1971) ................................ 2, 6

Davis v. School Dist. of Pontiac, 443 F.2d 573

(6th Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 913 (1971) . . 17, 19, 30

Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, 482 F.2d 1044

(6th Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 42 U.S.L.W.

3423 (Jan. 21, 1974) 16, 18n

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 417 Fi2d

801 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 904

(1969) 39

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ., 429 F.2d 364 (8th

Cir. 1970) .................................... 17n, 20

Hill v. Franklin County Bd. of Educ., 390 F.2d

. 583 (6th Cir. 1968).............................. 20n

Jackson v. Wheatley School Dist., 430 F.2d 1359

(8th Cir. 1970).................................. 23, 30

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 5th

Cir. No. 72-3294 (Jan. 21, 1974) .............. 41

Kelley v. Guinn, 456 F.2d 100 (9th Cir. 1972),

cert, denied, 413 U.S. 919 (1973).............. 36n

iii

Page

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ., 463

F.2d 732 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 '

U.S. 1001 (1972) .............................. 38, 39

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 413 U.S.

189 (1973) .................................... 18n, 19

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) .............. 33n

McFerren v. County Bd. of Educ., 455 F.2d 199

(6th Cir.), cert, denied, 407 U.S. 934 (1972) . . 20n, 23

McFerren v. County Bd. of Educ. of Fayette County,

Civ. No. C-65-136 (W.D. Tenn., Aug. 4, 16, 1973). 20, 25

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964) . . . . . . 33n

Medley v. School Bd. of Danville, 482 F.2d 1061

(4th Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 42 U.S.L.W. 3423

(Jan. 21, 1974)................................ 36n

Mims v. Duval County School Bd., 447 F.2d 1330

(5th Cir. 1971)................................ 19

Mims v. Duval County School Bd., 329 F. Supp. 123

(M.D. Fla.), aff'd 447 F.2d 1330 (5th Cir. 1971). 27

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs, 453 F.2d 259 (6th Cir.),

cert, denied, 406 U.S. 945 (1972).............. 2 , 4-6/ 41

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs, 427 F.2d 1005 (6th Cir.

1970).......................................... 39

Monroe v. County Bd. of Educ., 439 F.2d 804 (6th

Cir. 1971) 12n

Newburg Area Council, Inc. v. Board of Educ., 6th

Cir. No. 73-1403 (December 28, 1973) .......... 16, 36-37, 39

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 412 U.S.

427 (1973) 15

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 466 F.2d

890 (6th Cir. 1972)............................. 37 , 39, 40n

Palmer v. Thompson, 403 U.S. 217 (1971) 18n

Pitts v. Board of Trustees of DeWitt, 84 F. Supp.

975 (E.D. Ark. 1949) 23

Quarles v. Oxford Municipal Separate School Dist.,

Civ. No. WC6962-K (N.D. Miss., Jan. 7, 1970) . . 20

Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., 442 F.2d

255 (6th Cir. 1971)............................. 2

Rolfe v. County Bd. of Educ., 391 F.2d 77 (6th

Cir. 1968) 20n

IV

Page

Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ., 311 F.

Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1970) .................... 17, 30

Sparks v. Griffin, 460 F.2d 433 (5th Cir. 1972) . . . 23

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971).............................. 2, 6, 35

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 372

F.2d 836 (1966), aff'd en banc, 380 F.2d 385

(5th Cir.), cert, denied sub nom. Caddo Parish

School Bd. v. United States, 389 U.S. 840 (1967)• 23

United States v. Scotland Neck City Bd. of Educ.,

407 U.S. 484 (1972)............................ 20n

United States v. Wilcox County Bd. of Educ., 454

F. 2d 1144 (5th Cir. 1972)..................... 23

Statutes and Rules:

20 U.S.C. § 1 6 1 7 .................................. - 15, 41

F.R.C.P. 5 2 ........................................ 17n

v

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 73-2249

BRENDA K. MONROE, et al.,

Pla.i.ntif fs-Appellants,

vs.

THE BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF THE CITY OF JACKSON, TENNESSEE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees„

/appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Tennessee

Eastern Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Issues Presented for Review

1. Did the Board of Commissioners carry its burden of

demonstrating that the proposed closing of formerly black

South J^kson y School was based upon non-racial

grounds?

2. Have the Board of Commissioners and/or the district

court yet achieved the constitutionally required dismantling

of Jackson's dual school system when the plan ordered into

effect by the court (a) utilizes limited non-contiguous

zoning of black students only; and (b) results, in this small

half-white school system, in the operation of one elementary

school over 98% black, one 75% black, and two less than 30%

black?

3. Did the district court commit error in arbitrarily

fixing an inadequate counsel fee award to plaintiffs, without

a hearing, opportunity for submission of evidence, or specific

findings indicating the court's method of computation?

Statement

A . History of the Case

This school desegregation suit, originally commenced in

1963, appears before this Court for the fourth time. See •

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs, 453 F.2d 259 (1972). The detailed

history of the litigation prior to the recent district court

proceedings is set out in this Court's decision, ibid.,

remanding the matter to the district court for reconsideration

of the elementary school assignment plan in light of Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ,, 402 U.S. 1 (1971); Davis

v. Board of School Comm'rs, 402 U.S. 33 (1971); and Robinson

v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., 442 F.2d 255 (6th Cir. 1971).

Upon receipt of the mandate, the district court held

1/evidentiary hearings commencing August 29, 1972 (see 5a-171a),

T T Citations to Appendix on these cross-appeals, Nos. 73-2249,

-2250 and -2251.

-2-

in which the plaintiffs, the Board of Commissioners, and the

United States, as amicus curiae, participated. The Board of

Commissioners [which also serves as the Jackson system's

school board, (257a)] has consistently maintained the position

that it was operating in conformity to constitutional require

ments, and the Superintendent testified that no significant

changes in pupil assignment were contemplated for 1972-73

(39a).

Following that hearing, the district court permitted the

parties and the amicus curiae to submit proposed Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law, extending the time for this

purpose in order to allow study of the complete transcript

of proceedings. On March 15, 1973, the United States filed

a comprehensive Memorandum recommending, inter alia, that the

district court require further desegregation of the elementary

schools (see 188a) . In response thereto, the Board of

Commissioners again insisted that it was operating in full

compliance with the Fourteenth Amendment (189a) but proposed

the closing of the formerly all-black South Jackson Elementary

School for the following school year with reassignment of

its remaining students in a manner "which will result in

greater integration of these schools." (ibid.) .

Plaintiffs objected to the sufficiency of these steps

to achieve adequate dismantling of Jackson's dual system,

and to the proposal to close South Jackson School (195a-197a)

and at the subsequent hearings in May, 1973, presented an

-3-

alternative desegregation plan (527a-530a) developed by their

2/expert witness, Dr. Michael Stolee (520a-526a; 272a-373a).

In a Memorandum Opinion issued July 17, 1973 (597a-625a)

and implementing Order entered nunc pro tunc on August 28,

1973 (632a-633a), the district court allowed the South Jackson

closing, rejected the submissions of both the Board of Commis

sioners and the plaintiffs, and directed certain modifications

of the Board of Commissioners' plan for the 1973-74 school

3/

year. This appeal and cross-appeals followed.

B. Desegregation of the Jackson Elementary Schools

This appeal questions the adequacy of desegregation in

the Jackson, Tennessee elementary schools. Excerpts from

this Court's 1972 opinion provide the appropriate background:

. . . In August of 1968 . . . [t]he Board

responded by submitting a plan containing

the identical geographic zones drawn at

the inception of this litigation . . . .

27 At the May hearings, the Superintendent revealed that a

contract of sale for the South Jackson school property had

been executed between the City of Jackson (Board of Commis

sioners) and the Jackson Housing Authority in March, 1973 and

a warranty deed of conveyance signed (554a-557a) although

district court approval of the school's closing had not yet

been obtained. The plaintiffs thereupon filed a petition for

contempt, to add the Housing Authority as a party and to issue

injunctive orders to maintain the status quo pending judicial

determination of the propriety of the closing and property

transaction (531a-544a). The Housing Authority was joined

(578a-580a) and the district court's orders to date have

preserved the school from destruction pending determination

of this appeal (ibid.; 632a-633a) .

3/ The district court also awarded plaintiffs' counsel $1,500.00 in attorneys' fees, which had been sought by motion

during the proceedings (583a); on this appeal plaintiffs con

test the amount of the award, while on the cross-appeal the

City of Jackson contests the appropriateness of any such award.

-4-

On May 28, 1969, the District Court ordered

the elimination of the free transfer provi

sion, and ordered the revision of school

zones to accomplish greater desegregation.

Following entry of that order, the Board

requested a stay with respect to the elim

ination of the free transfer provision and

the revision of the zones. The Court granted

the motion with respect to the zones, but

refused to stay the elimination of the free

transfer provision. On June 19, 1970, the

order of the District Court was affirmed by

this Court. 427 F.2d 1005 (6th Cir. 1970).

One month later, the school board sought

approval of an amended plan of desegregation

for the 1970-71 school year which retained

the identical zones which the District Court

had ordered altered. . . . [N]o alternative

zones for the elementary grades were pro

vided . . . .

. . . [T]he litle IV Center . . . concluded

that geographic factors and residential

housing patterns were such that no other

zoning patterns "would be likely" to signif

icantly alter the existing racial imbalance

. . . it proposed some adjustments or

alterations in the existing zones which admittedly differed very little from those

then in use. The report then suggested two

further alternative plans: (1) non-contiguous

zoning might be utilized if school supported

transportation could be instituted, or (2)

adjacent schools might be paired and the

boundary zones enlarged to encompass the new

area. Several pairings were suggested, any

of which would result in greater integration

than is possible with the present method of

zoning.

. . . [T]he District Court ordered that theproposed zone changes be adopted. . . . The

plaintiffs contend that the District Court

was obligated to adopt either the pairing or

the non-contiguous zoning proposal of the

Title IV Center because these alternative

plans provided for greater desegregation than

the zones adopted by the Court . . . .

. . . [F]our of the nine elementary schools

are integrated in ratios similar to those

just cited for the junior high schools; but

-5-

. . . in the five remaining elementary schools,

three are over 90% black and two are over 90% white. Integration in these five schools is

minimal because the location in the city is

such that no conceivable zoning change would

produce any substantially greater integration.

Regardless, however, of these salutary evidences

of accomplishment, the possibility exists that

even greater accomplishment might result from a

further study of the situation in the light of

Swann, and of Robinson and Davis. The cause will therefore be remanded to give the District

Court opportunity for such consideration.

(453 F.2d, at 261-62). The district court did reassess the

matter in light of Swann and Davis; it accepted the use of

pupil transportation as an essential tool which had to be

used in Jackson to bring about what it considered a constitu

tionally adequate measure of desegregation (613a-619a). In

our view, however, the district court stopped short of requiring

that the tool be used in an effective manner; the continued

retention of even one all-black school in this small system,

together with three other facilities which we submit are •

racially identifiable in the context of the entire plan, is

constitutionally unacceptable.

1. The 1972-73 elementary school zones

As this Court noted in its 1972 opinion, Jackson's

elementary school zones had remained virtually intact from the

inception of the litigation and the implementation of the

Title IV Center's rezoning recommendations in 1971-72 made

only minimal changes. This conclusion was substantiated at

the August, 1972 hearings before the district court (18a-19a,

-6-

22a, 30a, 54a). The only appreciable effect of the Center's

recommendations shifted approximately fifty black students

from South Jackson Elementary School to West Jackson Elementary

School (52a-53a). And the October, 1972 enrollment report

filed by the Board of Commissioners demonstrated little prog

ress in eradicating the vestiges of Jackson's dual elementary

system: three schools were more than 99% black and two were

more than 95% white (185a).

The Superintendent of Schools testified, however, that

no further desegregation steps were contemplated by the Board

of Commissioners (39a). He had studied the non-contiguous

zoning and contiguous pairing alternatives discussed in. the

Title IV Center report but concluded they were impracticable

of execution in Jackson because they would lead only to reseg

regation within the school system and/or white flight from •

the district (58a-64a, 84a, 89a, 101a, 106a-108a, 114a-115a).

He admitted that one-race schools remained in Jackson because

residential patterns were segregated and schools had been

located within one-race neighborhoods (44a); and that the

schools had been designed and located to accommodate children

in one-race neighborhoods (72a-76a); but he expressed the view

that eventual housing integration was the only method of1/desegregating the Jackson public schools (96a). His testimony

The Superintendent admitted, however, that housing segre

gation was not lessening, but remaining at the same level, in

Jackson (103a). See also, 132a (Mayor believes housing

integration will occur in future, even though it has not yet taken place).

-7-

also demonstrated that such elementary school desegregation

as existed in Jackson in 1972-73 resulted from changing

residential patterns in school zones which were formerly

white and into which blacks now were able to move (46a-48a).

This major population shift coincided with the opening of

7\ndrew Jackson Elementary School in the extreme northwest

portion of the City and the elimination of the free transfer

option (136a-138a, 143a, 171a).

2. The Board's 1973-74 proposals

After the transcript of the August, 1972 hearings became

available, the United States submitted a Memorandum in which

it urged that further desegregation of Jackson's elementary

schools was required (see 188a). The Board's response con

tended that it was already operating a unitary system (189a)

but added that the Board now found it necessary to close the

South Jackson Elementary School and that the student reassign

ments which would thereby be necessitated would improve ele

mentary school integration (ibid.). Treating this Response

as the equivalent of submission of a new plan, plaintiffs

filed Objections thereto, which stated in part as follows:

1. Defendants have not and cannot carry their

burden of establishing that the closing of the

formerly all-black South Jackson Elementary

School is related solely to non-racial objec

tive criteria as required by law.

2. Closing of said South Jackson Elementary

School places an unwarranted, unfair and

unequal burden of school desegregation upon

black school children and causes school deseg

regation in the City of Jackson to operate

unequally as to them.

-8-

3. The revised geographic zones proposed by-

defendants will result in the continued mainte

nance of one virtually all black elementary

school (Lincoln), one virtually all white elementary school (Andrew Jackson) and will substantially increase the degree of segregation

in two other elementary schools (Alexander and

parkview). . . .

(195a). Plaintiffs also engaged the services of an expert

witness in educational administration and desegregation, Dr.

Michael Stolee (520a-526a), who prepared an alternative plan

of desegregation (527a-530a). Hearings were held May 10 and

May 22-23, 1973.

At these hearings, the Superintendent testified in

support of the Board" contention that it was operating a

unitary system and was in compliance with constitutional

requirements; he said the proposed attendance zone changes were

not part of a desegregation effort but were necessitated only

because the Board found it otherwise necessary to close the

5/ . .South Jackson School (386a). While black students living

within the former South Jackson zone would be dispersed among

the remaining eight elementary schools under the Board s

proposal, zone changes were basically contiguous (218a-219a,

224a-227a) and would not have altered the continued operation

of Andrew Jackson and Lincoln schools as virtually all-white

and all-black schools, respectively (191a).

W ~ Because consideration of the legality of the Board's decision to close South Jackson requires detailed evaluation

of the evidence, the testimony and exhibits will not be

summarized here but will be discussed in the course of the

Argument, infra.

-9-

The Board did not propose to provide transportation for

the reassigned black students; neither the Superintendent nor

any of the Commissioners had investigated the cost of providing

buses or utilizing the city—owned public bus system (265a, 271a,

412a; see 117a-118a).

3. Plaintiffs' Plan

When the May, 1973 hearings resumed, plaintiffs presented

the plan of desegregation developed by Dr. Stolee for the

Jackson elementary schools (527a-530a). Unlike the Board, Dr.

Stolee proposed the retention of South Jackson because it

was, in his opinion, educationally adequate (284a-286a, 29ja)

and because the move to close it seemed to him not coincidental

but typical of the national pattern of discrimination among

school districts required to desegregate (277a). Using one

non-contiguous pairing (309a) and one non-contiguous clustering

6/

(310a) requiring the transportation of 925 students (312a),

Dr. Stolee proposed to eliminate all racially identifiable

schools and thus to desegregate the entire system (319a). The

attendance zones for schools not involved in the pair and

7/

cluster would remain unchanged (306a).

6/ There are approximately 7500 students in the system (644a).

Slightly more than half this number are in the elementary grades

(ibid. ) .

7/ Dr. Stolee explained that he considered these schools

adequately desegregated, in the context, of the Jackson system,

with their 1972-73 zone lines in effect. (306a). He recognized,

however, that enrollments at these schools were affected by the

existing majority-to-minority transfers, and suggested an amend

ment to his plan altering a line between Lincoln and Whitehall

should the number of black students transferring into Whitehall

drop significantly (308a).

-10-

Dr. Stolee testified that he found the Board's proposal

unacceptable as a desegregation measure since it failed'to

eliminate racially identifiable schools (276a-277a); that is,

schools attended by proportions of black and white students

which differed significantly from the system-wide ratio (302a).

Under cross-examination, he denied that he had attempted to

achieve "racial balance," but stated that he was particularly

concerned with the five racially identifiable elementary

schools noted by this Court in 1972, and that he had sought

a method of effectively desegregating each with the least pupil

transportation (356a-358a; see also, 318a). The greatest

distance between any of the paired or clustered schools was

determined by the Board to be between 4.2 and 5.0 miles (183a);

Dr. Stolee testified that he drove between the schools,

following posted limits, along a 4.9-mile route and covered

the distance in thirteen minutes (314a). He recommended school

to-school busing and estimated that by staggering school

opening hours, the plan could be implemented with the purchase

of only five school buses, including one for a spare (319a).

The Superintendent of Schools testified in rebuttal

that he was opposed to a plan requiring the expenditure of

funds for pupil transportation (383a), which was not a priority

8/of the Jackson school system (413a-414a). He summarized his

grounds for rejecting Dr. Stolee's proposals as concern for

K7 The Board's annual budget is approximately $4 million, of

which the Stolee plan might require slightly less than $50,000

for initial capital expenditure (to purchase buses) (325a-326a)

-11-

"community acceptance and cost" (409a). However, he had

2/investigated neither the Madison County busing plan nor the

amount of State reimbursement for operating expenses to which

Jackson might be entitled (416a-417a). Rather, despite his

recognition that some of the "school neighborhoods" defined

by Jackson's attendance areas were very extensive (400a-401a),

that "residential neighborhoods" reflect social and economic

homogeneity (402a), and that more black than white families

in Jackson are below the poverty line (425a), the Superintendent

nonetheless sought to preserve the "neighborhood school"

concept because it would encourage parental allegiance and

support of particular -schools (403a).

4. The District Court's ruling

On July 17, 1973, the district court filed a Memorandum

Opinion (597a-625a) which approved the Board's request to close

South Jackson Elementary School (606a-612a) but found the

Board's proposal for elementary student assignment inadequate

because it "does not sufficiently meet the requirement of ful

filling its affirmative duty to eliminate discriminatory effects

of the past. Green v. New Kent County School Board, 391 U.S.

430, 438 (1968)." (616a). The district court also rejected

plaintiffs' plan/ both because as drafted it contemplated the

w ~ Monroe v. County Bd. of Educ. of Madison County, 439 F.2d

804 (6th Cir. 1971). Jackson is located within Madison County,

Tennessee. See also, Seals v. Quarterly Court of Madison

County, No. 73-1673 (pending).

-12-

, 10/ .continued use of the South Jackson facility (ibid.) and

because it required greater pupil transportation than the

court felt necessary (cf. 617a). Instead, without directing

further submission of plans by any party, the district court

undertook to

prescrib[e] a plan involving a minimum of

transportation and some elementary school

zone or district changes which this Court

believes will meet constitutional requirements with the least disruptive effects.

This plan has been fashioned in recognition

of the -fact, among others alluded to, that

the defendants in making the progress here

tofore noted have not totally defaulted in

their duty to submit an acceptable plan, and because it has never before operated a

bus system as was the case in Swann, supra, and to some degree in Davis, supra (both in

Mobile and in Pontiac), and because sub

stantial progress has already heretofore

been made.

(617a). The rudiments of the district court's plan are as

follows: the remaining students residing within the former

South Jackson Elementary School zone, rather than being

reassigned to contiguous elementary schools, would be trans

ported to Highland Park and Andrew Jackson Schools, as well

11/as to Washington-Douglas; and certain other boundary lines

would be altered. The following table compares the racial

composition of each elementary school's student body as pro-

10/ nr.stolee testified that closure of South Jackson would require the drafting of a new plan but that it could be based

upon the same principles as his plan: effective desegregation

(346a).

11/ The district court's plan contemplated assignment of additional black students from the former South Jackson zone

to Highland Park and Andrew Jackson on a rigid, mathematical

basis (618a).

-13-

jected under the various plans, and as actually resulted in

both 1972-73 and 1973-74:

School

% Black, Actual

1972-73— -/

Projected

% Black, Board 1s Plan 13/

Projected

% Black,

Plaintiffs 1

Plan 14/

Proj ected

% Black,

• Court1s

Plan 15/

% Black, Actual 1973-74 i§/

Alexander 36 % 27 % 36 % 40 % 45 %

Andrew Jackson 5 % 4 % 55 % 21 % 28 %

Highland Park 3 % 24 % 50 % 18 % 24 %

Lincoln 99 % 99 % 59 % 98 % 98 %

Parkview 46 % 70 % 46 % 53 % 60 %

South Jackson 98 % — 54 % — —

Washington-

Douglass 98 % 48 % 53 % 79 % 75 %

West Jackson 42 % 52 % 42 % 39 % 43 %

Whitehall 58 % 62 % 58 / 57 % 56 %

The district court's plan requires the transportation of

approximately 200 students (618a-619a, 626a-627a) from the former

South Jackson zone to Andrew Jackson and Highland Park Schools,

a distance of up to 5.9 miles (183a).

/ (185a). includes majority-to-minority transfers.

13/ (191a) . Projections do not anticipate majority-to-minority transfers.

14/ (527a-529a). Projections anticipate continued majority-to-

minority transfers to Whitehall sufficient to maintain ratio.See note 7 supra.

15/ (G2la). Pro jections anticipate majority-to-minority

transfers into Alexander from Lincoln and Whitehall.

16/ (644a). Includes majority-to-minority transfers.

-14-

C . Attorneys 1 Fees

After the May, 1973 evidentiary hearings, plaintiffs

moved for an award of counsel fees and litigation expenses

(583a) based in part upon Section 718 of the Education Amend

ments of 1972, 20 U.S.C. § 1617 (584a-585a). (See Northcross

v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 412 U.S. 427 (1973)). The memo

randum incorporated by reference in the motion asked the

district court "to fix a date for hearing thereon or otherwise

designate appropriate procedure for determination of said

Motion" (585a). Without receiving evidence or argument, or

holding a hearing, the district court'disposed of the prayer

for a counsel fee award in its July 17, 1973 Memorandum Opinion

(624a-625a). Expressing doubt whether § 718 authorized an

award in the circumstances of this case, the court nonetheless

determined to make an award "in the exercise of equitable

discretion" (625a). Although it had no information concerning

the amount of fees requested or the time invested in the -case

by plaintiffs' counsel, the district court fixed the award at

$1500.00 (625a, 633a).

Following entry of an Order on the opinion (632a-633a),

these appeals and cross-appeals followed.

15-

ARGUMENT

I.

The Board Failed To Carry Its Burden Of.Showing

That The Decision To Close South Jackson

Elementary School Was Based Upon Objective, Non-

Racial Factors. The Evidence Demonstrated

Inconsistent Application Of Standards To Black

And White School Facilities.

A. Review of the District Court's Decision Permitting TheBoard to Close South Jackson Is Not Governed By Rule 52.

This Court has demonstrated a very substantial disinclina

tion, in school desegregation cases, to substitute its judgment

for that of the district courts in assaying factual determina

tions. E.g., Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, 482 F.2d 1044

(6th Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 42 U.S.L.W. 3423 (Jan. 21, 1974);

Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., 467 F.2d 1187 (6th Cir.

1972) . Compare Newburg Area Council,_Inc. v. Board of Educ.,

6th Cir. No. 73-1403 (December 28, 1973). For that reason,

it is important to recognize, as the Court reviews this matter,

that the district court's decision to permit the closing of

11/Jackson's historically black South Jackson School does not

rest upon factual findings which must be accepted as presump- i

i 7 7 Although presently used as an elementary school, South

Jackson was the city's only black secondary school from 1936

to 1957 (255a); its opening may well have marked the first

time the city provided any secondary education to black

students.

-16-

tively correct. There are no-contested factual issues, for

example, on whose resolution this matter conclusively turns.

Plaintiffs challenge not the verity of the "factors" listed

in support of the district court's determination, but the legal

significance to be accorded them in light of the other, equally

uncontested, facts of record. When all the evidence is con

sidered, the inconsistent approach of the school authorities

with respect to every factor by which the South Jackson closing

is sought to be justified is readily apparent and it becomes

impossible to hold as a matter of law that a non-racial basis

therefor has been demonstrated. Cf. Davis v. School pist, of

Pontiac^ 443 F.2d 573, 576 (6th Cir.), cert. denied, 404 U.S.

913 (1971); Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ.. 311 F. Supp.

501 (C.D. Cal. 1970).

The essential matter to be established here, however, 'is

simply that the ultimate determination of the district court,

i.e., that

the closing [is not] . . . associated with

unconstitutional racial overtones. See

Robinson v. Shelby County, supra. The

18/

.We do not mean to suggest that cases in which black school closings are challenged may never turn upon clearly factual

determinations. For example, if a school system contends that

a school facility is irreparably deteriorated and structurally

unsound or otherwise clearly unusable for educational purposes,

c_f. Hanev v. County Bd, of Educ.. 429 F.2d 364 (8th Cir. 1970),

then the existence of that condition vel non may foreclose any'

further inquiry into possible racial motivation, and a lower

court finding that the condition exists might properly be

reviewed in accordance with F.R.C.P. 52. In this case, no such

contentions were made by the Board (cf. 285a), and the district

court's "findings" are all qualified, relative statements (see 606a-611a) . -------- ---

-17-

defendant has carried its burden in this par

ticular. Haney v. Sevier County Board of •

Education, 429 F.2d 364 (8th Cir. 1970).

[612a]

represents a legal determination fully reviewable by this

Court, rather than a factual finding as to which plaintiffs19/

bear some extra special burden of persuasion on appeal.

B. Racial Discrimination in the Desegregation Process

The district court correctly recognized (612a) that

because the Board of Commissioners had not sought to close the

South Jackson School until confronted with the necessity of

desegregating its system, the burden of demonstrating that

the move was grounded upon non-racial factors was upon the

school board (612a). This'is appropriate, because — absent

some dramatic testimonial recantation of the kind which occurs

far more frequently on the television screen than in the

courtroom — a finding that the actions of an official body

were motivated by race rests upon inferences drawn by the

20/

trier of fact from a multitude of circumstances and events.

Thus we do not ask this Court on this appeal, as it has

apparently been asked in other cases, to depart from its traditional role ws a reviewing tribunal because of the nature

of the litigation and the special responsibilities which argu

ably were imposed upon all federal courts by Supreme Court

decisions such as Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396

U.S. 19 (1969). See Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, supra,

482 F.2d, at 1047.

20/ Indeed, the difficulty of determining the motivation of

an agency of government, see Palmer v. Thompson, 403 U.S. 217

(1971), is one of the primary justifications for application of

the burden-shifting principle. See Keyes v. School Dist. No.

1, Denver, 413 U.S. 189, 261-62 (1973) (Rehnquist, J., dissent

ing) .

-18-

For example, this Court approved such a finding in a case in

■which the plaintiffs bore the burden of proof:

Although, as the District Court stated, each

decision considered alone might not compel

the conclusion that the Board of Education

intended to foster segregation, taken together,

they support the conclusion that a purposeful

pattern of racial discrimination has existed in the Pontiac school system for at least 15 years.

Davis v. School Dist. of Pontiac, 443 F.2d 573, 476 (6th Cir.),

cert, denied, 404 U.S. 913 (1971), cited with approval in

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 413 U.S. 189, 210 (1973).

The notion retains importance even where the burden rests

upon the school authorities. See Keyes, supra. For where

school orficials must establish that their decisions were not

based on impermissible racial considerations, it follows that

they ought to be able to show a consistency of decision-making

unrelated to race; and further, that ostensibly neutral prin

ciples which coincide with racially differentiating factors

when applied to a particular system, do not serve to meet the

school authorities' burden of proof. See generally, Mims v.

Duval County School Bd., 447 F.2d 1330 (5th Cir. 1971). Thus,

a proposal to close black schools because of their physical

condition, when the school system also seeks to maintain white

schools in worse condition, could hardly meet the school board's

burden of proof, no matter what the condition of the black

schools was. Likewise, a school system's request to close a

black school despite its patent inability to house the students

in other facilities, would clearly indicate a racial purpose.

-19-

E.q-/ Quarles v. Oxford Municipal Separate School Dist., Civ.

No. WC6962-K (N.D. Miss., Jan. 7, 1970) (oral opinion). Or

where school authorities are themselves responsible, through

discrimination, for the very conditions by which they seek to

justify the closing of black schools, such conditions hardly

constitute "non-racial" factors. E,g,, McFerren v. County Bd.

of Educ. of Fayette County, Civ. No. C-65-136 (W.D. Tenn., Aug.

21 /4, 16, 1973).

Proposals to close black schools which coincide with

implementation of constitutionally required desegregation,

then, place the burden on school authorities to demonstrate

that racial considerations did not result in the decision to

cease operation of these facilities. If that burden is not met,

then such closings are presumptively discriminatory and imper-

22/missible. Haney v. County Bd. of Educ., supra. And the

21/ . ~— f ^Occasionally, school authorities seek to justify the

extinction of black schools on outright racial grounds which

they relate to the success of any desegregation program: i.e.,

that white students will flee the system rather than attend

formerly black facilities. E_.f[. > Bell v. West Point Municipal

Separate School Dist.. 446 F.2d 1362 (5th Cir.‘ 1971) . Where that is the sole reason offered for closing a school, it is

clearly unacceptable. Bell, supra. However, where it is claimed

to be one factor among others, it often masquerades as a legit

imate concern for achieving the most effective desegregation.

Cf. United States v. Scotland Neck City Bd. of Educ., 407 U.S.

484^ (19/2). In such a situation, the courts must weigh the claim to determine whether it reflects sincere effort or

Pptense and the persuasiveness of the other rationales for the school closing is determinative.

2/// Similar buiden—shifting and presumption principles have been

applied to teacher terminations during the desegregation process See McFerren v. County Bd. of Educ.. 455 F.2d 199 (6th Cir.)

cert, denied, 407 U.S. 934 (1972); Ilill v. Franklin County Bd.

o_f—Educ. , 390 F. 2d 583 (6th Cir. 1968);- Rolfe v. Countv Bd. of Educ., 391 F.2d 77 (6th Cir. 1968). -------------

-20-

presumption cannot be met by identifying characteristics of

black schools which, if they require discontinuance of the

black facilities, would also mandate closing white schools

which are no different, or by listing deficiencies which exist

only because of conscious policies carried out in the past by

the school authorities. (See 292a). We now examine the record

in this case in light of these principles.

C. Adequate Non-Raclal Justification For Closing The South

Jackson Elementary School Was Not Shown By Defendants

On April 9, 1973, while the issue of what additional

elementary school desegregation was constitutionally required

lay before the district court, the Board of Commissioners first

sought permission to close the South Jackson Elementary School,

which had always been a black school (e,g., 174a). The appli

cation, filed in response to a memorandum submitted by amicus

curiae United States of America urging new initiatives to

desegregate the elementary schools, listed the following reasons

1. The South Jackson School is in the urban

renewal area and the school property has been

acquired by the Jackson Housing Authority in

furtherance of its urban renewal project.

2. Student enrollment at the South Jackson

School has been declining for the past five

years. This has been due principally because

of the removal of families from the urban

renewal area. 3

3. The South Jackson School building is antiquated, being the oldest building now being

used as a public school in the City of Jackson.

The building is no longer adequate from an

educational standpoint.

-21-

4. It is not economically sound to continue

to operate the South Jackson School.

(190a). The obligation of the district court was to evaluate

these grounds in the light of the evidence developed at the

hearing, to determine whether they were the real reasons for

closing the facility or merely a screen to mask racial motiva

tions. We review accordingly not merely the district court's

ultimate conclusions, but also the evidence in the record whi

supports or contradicts those conclusions.

The district court's opinion contains a lengthy discursive

section relating in part to the Board's proposal to close

South Jackson (602a-6l2a). The court summarizes its conclusions,

however, as follows (611a-6l2a):

Because (1) it is a comparatively inferior

facility due to its age and state of repair,

(2) it is located in the midst of a designated

and rapidly changing urban renewed 1 commercial

area with little nearby present residential

potential, (3) the steady decline in attendance

of elementary school children there makes it

impractical and unduly burdensome for its

continued operation, and (4) there is no

prospect of racial mixture in the school through

changes in neighborhood residential patterns, the Court approves the requested closure of

South Jackson Elementary School . . . [subject

to mandatory assignment changes required by the Court, see Argument II, infra).

We respectfully submit that none of these factors, singly or

in conjunction, establishes (in the context of the entire record)

that the Board's proposal is not racially motivated; and for

that reason, the district court should have required the

continued use of the South Jackson facility.

-22-

1. condition of the facility. Plaintiffs do not suggest

that white children must be assigned to ramshackle, deteriorat

ing, structurally unsound, formerly black schools for the sake

of some abstract principle. See, e.g., Carr v. Montgomery

County Bd. of Educ., 429 F.2d 382 (5th Cir. 1970); Chambers v.

Iredell County Bd. of Educ., 423 F.2d 613 (4th Cir. 1970).

Black students should never have been required to attend such

schools either, but racism often kept them there. See, e.g.,

Pitts v. Board of Trustees of DeWitt, 84 F. Supp. 975 (E.D. Ark.

1949) , Brown v. Board of Educ. of Dewitt, 263 F. Supp. 734

(E.D. Ark. 1966); United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ.,

372 F.2d 836, 891-92 (1966), aff'd en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th

Cir.), cert., denied sub nom. Caddo parish School Bd. v. United

States, 389 U.S. 840 (1967); United States v. Wilcox County

Bd. of Educ., 454 F.2d 1144, 1145 (5th Cir. 1972).

The question which must be answered when a school board

seeks to close a black facility during the desegregation'process,

and advances justifications related to physical condition, is

whether the building is in fact beyond salvageable use for

educational purposes, or whether the defects noticed only when

white student occupancy is contemplated are more presumed than

real. Cf. McFerren v. County Bd. of Educ., supra, 455 F.2d 199;

Sparks v. Griffin, 460 F.2d 433 (5th Cir. 1972); Jackson v.

Wheatley School Dist., 430 F.2d 1359 (8th Cir. 1970). As Dr.

Stolee put it in his testimony [discussing another ground

offered by the Board]: "As long as the school stays all black,

we are willing to do it, but then, as soon as it appears that

-23-

we are going to have to desegregate the school, then, and at

that point, [we have these other concerns]" (289a-290a).

The South Jackson Elementary School is not, as the Board

stated in its written submission (190a), "the oldest building

now being used as a public school in the City of Jackson,"

although it is the oldest elementary facility (200a). it is

instructive to consider the fact that the original (white)

Jackson High School, although built eight years earlier (173a),

is still in use as the west campus of the system's consolidated

high school (241a-242a). The difference in present physical

condition of the two plants is directly traceable to the

discriminatory practices of the defendants: the white school

had several additions over the years, including $250,000.00

worth of renovations in the last two years (242a) but according

to the Superintendent, there were no improvements to South

Jackson during the 21 years it served as the only secondary

school for black students, or thereafter (257a). To offer its

relative standing in relation to other schools operated by the

Board as a justification for closing it, then, is to offer only

the past discrimination as a reason for working a new discrimi

nation.

The building is in eminently useable shape. The Board

has made no contention of structural weakness which would pose

a safety hazard, as Dr. Stolee noted (285a). He found the

building adequate, although in need of regular maintenance

(284a-286a, 291a). The Superintendent testified that the South

-24-

Jackson plant could be improved with renovation just as Jackson

High had been (242a) and agreed that its facilities were

entirely adequate (e.g., 253a-256a; 431a-433a). The 1970 Title

XV Center study, although it contained the comments of the

Superintendent noted by the district court (604a), did not

suggest that the school ought to be closed. And while the

Superintendent testified in 1969 that there was capacity to

absorb South Jackson's students in other elementary schools

(see 611a), the Board never voiced the proposal until desegre

gation at the elementary level was imminent.

in summary, we believe that a fair reading of the evidence

shows that the South Jackson facility is sound and useable,

and that any relative disrepair is readily curable and related

to defendants' past discrimination— and cannot therefore

support a proposal to close the school. McForren, supra (W.D.

Tenn., Aug. 4, 16, 1973).

2. Location of the school. The district court noted that

the South Jackson School is presently located in a commercial

area without immediately surrounding residential development.

This is the result of an urban renewal program carried out by

the City of Jackson, which has substituted commercial usage

of cleared property for an area of former black residences23/

within the South Jackson zone (499a—502a). The character of

23/ sinCe the Board of Commissioners serves as both the school

board for the system and as the general governing body of the

city, supervising the urban renewal program (257a) and passing

upon zoning classifications (442a), here again the defendants

have by conscious design brought about conditions by which the

closure of the school is sought to be justified.

-25-

L

the immediate neighborhood which presently abuts the South

Jackson property is not detrimental to an educational atmosphere,

however. The school is not hemmed in by industrial or commer

cial establishments, but lies within an area of new public

buildings: a law enforcement building, fire station and

civic center (213a, 516a). There was flat disagreement between

the Superintendent and the City Planning Director, on the one

hand, and plaintiffs' witness Dr. Michael Stolee, on the other,

about the appropriateness of this setting for an elementary24/

school, but. little elaboration. However, the South Jackson

school zone was larger than the urban renewal area and still

contains many residences, including a housing project (208a,

243a-246a, 266a-267a, 283a-284a). The students in these resi

dences happen to be black; although South Jackson has always

been the school closest to the most commercial part of the City

of Jackson, the commercial character did not move the city to

close it prior to the time when desegregation was likely.to

25/

occur (437a).

W ~ Dr. Stolee found it a considerable improvement (279a-280a);

Superintendent Standley dismissed it as "one of the worst

locations in town" (441a) and the City Planning Director also

did not favor it because he wanted "neighborhood schools" (516a,

519a).

25/ The Superintendent said he had known since the formal approval

of the uarban renewal project that South Jackson Elementary School would eventually be closed (215a; see also, 211a), and the Board

claimed at the hearings that elimination of the facility had

always been a part of the urban renewal program, which neverthe

less received the affirmative vote of black Jackson residents

(e.g., 459a). We do not agree that such a fact, even if clearly

established, would have eliminated the constitutional question;

but in any event, it is clear from the record that the ballot for

the urban renewal program did not contain a diagram or description of the project sufficient to indicate the proposed discontinuance

of the school (507a) and the small diagram on the newspaper notice

did not indicate the fate of any existing buildings (520a).

-26-

We submit tbat the showing with respect to the location

of the school falls so far short of that in, for example, Mims

v. Duval County School Bd., 329 F. Supp. 123, 132 (M.D. Fla.),26/

aff»d 447 F.2d 1330 (5th Cir. 1971), “ that this is no proper

ground upon which to close this black school and to require only

black students in the system to be transported outside their

27/

neighborhoods.

3. Declining enrollment and uneconomical operation. It

was not disputed at the hearings that over the past several years,

2 8/

the enrollment at South Jackson Elementary School had declined.

The Superintendent, contended that reduced enrollment made the.

facility so expensive to operate because of fixed costs (e»g• ,

201a) that it would be more economical to the system to close it.

He pointed out, for example, that the low daily attendance dis

qualified the school from receiving State supplementary aid

26/ indeed. the urban renewal program has removed the conditions

which the district court in the Mims case held justified the

closing of black schools when the school system desegregated.

27/ We do not endorse "neighborhood schools" nor resist "busing"

to bring about desegregation, nor do the vast majority of black

citizens in this Nation. We do recognize that pupil transportation is widely regarded as an inconvenience, and that feelings

and affections can be bound up with local schools. If these

are to be interrupted, or if children and their parents are to

be inconvenienced in the name of desegregation, then blacks ought

not bear the sole, or the disproportionate share, of those burdens.

28/ The major cause of the enrollment decline was, of course,

the clearance of large residential areas for urban renewal (200a),

although the school also lost students as the result of imple

menting a Title IV Center-recommended zone line change in 1971

(53a, 204a) and through majority-to-minority transfers (see

282a-283a).

-27-

toward a principal's salary (218a). The district court

apparently accepted these assertions as sufficient evidence of

a non-racial justification for closing the facility (611a).

This is a perfect example of the district court's failure

to evaluate the stated reasons for the closing to determine

whether they did, in fact, represent non-racial judgments. A

reduction in enrollment at South Jackson of some size was

educationally advantageous; although it once housed over five

hundred black school children (174a), a smaller attendance

allowed the school system to make, more efficient use of its

moderately sized classrooms (247a-248a). Superintendent

Standley agreed that the total number of students coming from

the South Jackson zone as it existed in 1972-73 was important2 9/

only if assignments were limited to contiguous zoning: if

elementary students were to be transported to the facility, the

declining residential use of the immediate neighborhood was

not important (441a; see also, 519a).

Likewise, the conditions which purportedly resulted in a

disproportionately expensive cost of operation at South Jackson

were common to other elementary schools in the system: several

other facilities had low enrollments which barred State salary

supplements for their principals (251a, 392a-396a); other

/ 11: has been apparent since 1970 that such assignment

constraints make complete desegregation of the system impos

sible. See p. 5 supra.

-28-

schools had vacant spaces and were similarly "uneconomical"

30/to operate (252a-253a, 397a). These conditions had existed

for some time, but the school system had not complained of them

prior to the time when desegregation of elementary schools

became imminent (396a). As Dr. Stolee put it:

Well, as far as the State not paying ADA for

a full-time principal, I have to lump a number

of these things together with my first, and

I think is my — and my first, I think, is

almost an overriding thought on this, and that

is that the statements that I read, the

statement I read on item four, page four, of

the document referred.to is one that once

again we see in many, many communities, that

is that for years, and years, and years, we find it economically feasible to operate a

smaller school to, in this case, pay a full

time principal, while the proportion of of

(sic] state aid for that principal might be lesser than some other school to have a custo

dian. As long as the school stays all black, we are willing to do it, but then, as soon as

it appears that we are going to have to

desegregate the school, then, and at that, point,

it becomes economically unfeasible.

(289a-290a) (emphasis supplied). The Superintendent admitted

that no educational considerations compelled the closing of

South Jackson (black) rather than West Jackson (white) (251a).

The claimed diseconomies of scale at South Jackson, then,

were no different in nature or degree from those found in other,

white, elementary schools in the system, and they do not amount

2Q7 vacant spaces in the system in the past had not caused the

closure of facilities. For example, there were many vacant

spaces throughout the district in 1969-70 when the new Andrew

Jackson Elementary School was opened; yet the Board had chosen

to relieve overcrowding at Highland Park by this new construction

rather than by reassigning white students to existing vacancies

in black schools (246a-249a).

-29-

to objective, non-racial grounds for the Board's proposal to

close the South Jackson facility. Cf. Davis v. School Dist.

of Pontiac, supra. This is all the more so since the conditions

were willingly tolerated by school officials until desegregation

of South Jackson was likely to be required by the district

court. Cf. Jackson v. Wheatley School Dist., supra.

4. Segregated neighborhood. The final concern listed by

the district court was the unlikeliness that the South Jackson

school zone would become residentially integrated (611a-612a).

As noted in the discussion of the preceding ground, this is

relevant only on the assumption that "neighborhood school zones"

will continue. The identical argument for closing a black school

was rejected in Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ., supra,

311 F. Supp., at 517:

Defendants' plan at the time of trial for deseg

regation of the junior high schools would, if

implemented, impose burdens on black students

to a greater extent than on white students.

Defendants plan to close Washington Junior High

School, principally because, "It is impossible

without a great deal of bussing to create any

kind of integration at that particular school."

This is a non sequitur, as closing Washington

would require transportation of all the students

normally assigned to that school. . . . What

defendants oppose is transporting white pupils

to school in a black neighborhood.

The same is true in this case, where the closing of South

Jackson has resulted in the transportation of black students

only (c_f. 259a-262a) . The rationale proposed by the district

court would be equally applicable to Andrew Jackson or Highland

-30-

(

Park (white) Elementary Schools, neither of which can be sub

stantially desegregated without transportation; it clearly

does not constitute a non—racial ground for selection of the

black facility for closing.

5. Other factors. The district court's opinion makes

mention of several other factors it considered in approving the

proposal to close the South Jackson School, although these are

not repeated in its summary holding; they bear brief mention

here.

Snippets of past testimony about South Jackson, to which

the district court refers (604a, 606a, 611a), for example,

hardly support a finding that the 1973 move to close the school

was based on non-racial grounds. Rather, they indicate the

consistent willingness of the Board to bear the "burdens" or

"diseconomies" associated with the school so long as it remained

segregated.

The district court's statement that "[t]he closing is part

of a long range plan to eliminate this oldest operating school

which is not directly related to racial motivation but rather

the intent, largely unfulfilled, to upgrade slum housing

occupied for the most part by blacks" (609a-610a), is simply

the court's own construction; for not even the Superintendent

attempted to fit the South Jackson closing into some long-range

scheme designed to benefit Jackson's black population!

-31-

A more accurate reflection of the district court's real

concern is its statement, describing Dr. Stolee's plan for

grouping South Jackson, Highland Park and Washington-Douglass

Schools, that "[t]his assumes that the whites would voluntarily

comply with bussing arrangement fsic] and attend this school,

an assumption not borne out by past experience . . . " (610a).

Not only is the court's supposition totally dehors the record,

since no one was ever transported to achieve desegregation in

the Jackson system prior to the order appealed, from., but it

represents precisely the speculative apprehension of white

flight which was rejected in. this very case in 1968 and 1970.

6. Unequal burden. The Board of Commissioners' plan for

reassignment of the former South Jackson pupils admittedly

placed the burden of desegregating Jackson's elementary schools

entirely upon black students (259a-262a) (Superintendent

Standley). This disproportionate sharing of inconvenience and

disruption was not mitigated by the alterations mandated by the

district court (618a-619a). Under the decree, black children

become the only Jackson students transported outside their

residential areas, rather than the only Jackson students who

must walk long distances outside their residential areas.

The district court gave lip service to the principle that

the burdens of desegregation must be equally shared by the black

and white communities (623a-624a); but it erred by equating

the contiguous reassignment of white students with the arbitrary

closure of a sound and useable black school and the reassignment

-32-

of the black children who would attend that school to schools

in white neighborhoods. See Brice v. Landis, 314 F. Supp. 974

(N.D. Cal. 1969).

7. Summary. We submit that the "objective and non-racial

grounds" offered by the Board of Commissioners to justify the

closing of the South Jackson School are shown on this record

either to relate directly to past discriminatory actions of the

school authorities or to apply with equal force to white facili

ties which defendants propose to maintain. Under these circum

stances, the district court erred as a matter of law in holding

that the Board of Commissioners met its burden of proof to

31/justify the closing of the school.

31/— The error is not cured by the vague and precatory direction

in the district court's order requiring that . '

The defendants will study the need and feasibility

of construction of a new elementary school in the

southwest area of Jackson to serve the general

South Jackson and West Jackson Elementary School

sections as a priority before the construction of

new schools or substantial elementary facilities in the system in the future.

(633a). if the direction is prompted by the court's recognition

that the closing of South Jackson is indeed discriminatory,

then the remedy is insufficient, especially since the West Jackson School is still in a white neighborhood (450a). If the

district court contemplates subsequent closing of the West

Jackson School to "balance the burdens," then it has merely

compounded the legal error. Disabilities imposed upon whites

and blacks because of race still violate the equal protection

clause although each may suffer "equally." Loving v. Virginia,

380 U.S. 1 (1967); McLauoh]in v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964).

-33-

II-.

Whatever The Fate Of South Jackson Elementary- School, The Case Must Be Returned To The District

Court To Complete The Process Of Desegregating

Jackson's Elementary Schools

Whether this Court holds that the South Jackson Elementary

School should continue in use or not, it must return this

case to the district court with instructions to complete the

desegregation process. For, while the case is not as shocking

as it was when black and white high schools existed across the

street from each other, it is yet remarkable that the best

efforts of the parties and the district court have not been

sufficient to eliminate all-black schools from this small

district.

We refer the Court again to the table at p. 14, supra,

indicating the results of the desegregation plans before the

district court, and actually implemented during the current

school year. The district court rejected the Board's plan

on the ground that

[It] does not sufficiently meet the requirement

of fulfilling its affirmative duty to eliminate

discriminatory effects of the past. [616a] 32/

Yet the only difference between the Board's plan and the court's

plan is the increase in the number of black students attending

Andrew Jackson Elementary School. The all-black identity of

2̂l7 The district court earlier noted that "[t]he Board's plan

would leave two of the eight elementary schools racially identi-.

fiable by very large majorities of white in one school and black

students in the other" (613a).

-34-

the Lincoln School— the outstanding vestige of segregation—

remained.

The district court also rejected the plan offered by

plaintiffs and developed by Dr. Stolee, not only because it

proposed the use of the South Jackson facility (616a) but also

because

two of the schools would continue to operate at

material undercapacity, and would involve trans

porting a large proportion of students attending

these two schools from other areas. . . . Exten

sive, multi-school bussing also involves other serious financial and administrative difficulties

the solutions to which have not been presented in

the several hearings herein. [613a-614a]

Yet, again, the district court's own plan requires the busing

of nearly 230 students to two different schools, although it

does not achieve as much desegregation as would the plaintiffs'

plan.

It is perhaps tempting to attribute the wisdom of Solomon

to the district court merely because it "cut the baby in half"

(by requiring more than the Board proposed but less than the

plaintiffs sought). However, that is not the standard by which

the adequacy of desegregation decrees are measured. Swann

directs district courts and school boards to "make every effort

to achieve the greatest possible degree of actual desegregation

. . . ." 402 U.S., at 26. The district court overlooked this

prescription, which appears in the sentence immediately following

that which it quoted in its opinion (614a): "It should be clear

that the existence of some small number of one-race or virtually

-35-

one-race schools within a district is not in and of itself ttie

mark of a system that still practices segregation by law."

Limiting our concern for the moment to the all black

34/ . _ ,Lincoln School~ it is quite clear in this Circuit that even

one such all-black facility may be too many. The language of

Newburg Area Council, Inc, v. Board of Educ_. , 6th Cir. No.

73-1403 (Dec. 28, 1973), is so apposite that we quote relevant

portions at some length:

The district court held that the existence of

an all black school, Newburg, in the Jefferson County School District was not unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court stated in Swann v. Charlotte

Mecklenburg School District, 402 U.S. 1/26 (1 9 7 D f that the "existence of some small number

of virtually one race schools within a district

is not in and of itself the mark of a system

that still practices segregation."

As this Court noted in Northcross v. Board of

Education of Memphis City Schools, 466 F.2d 890,

893 (6th Cir. 1972), this language in Swann xs "obviously designed to insure that tolerances

are allowed for practical problems of desegre

gation where an otherwise effective plan for

dismantlement of the school system has been ̂

adopted." The Jefferson County School Distract

thus has three elementary schools that either

are or are rapidly becoming "racially identifi

able." As stated, Newburg School, a pre-Brown

black school, is racially identifiable, while

Price and C an[eJ Run Schools are rapidly becoming

racially identifiable as black schools. The

33/ At least one Court of Appeals has suggested that the sentence

quoted by the district court reflects upon the proof necessary to establish a violation, while the following sentence articulates

the remedial standard. See Kelley v. Guinn, 456 F.2d 100, 109 10

(9th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 413 919 (1973)

34/ Swann further cautioned against "substantially dispropor

tlonate "'“schools, and we submit that Andrew Jackson, Highland Park, and Washington-Douglass are properly considered m this

category. Such a classification does not mean that a racial balance must be attained. Medley v. School Bd. of Danville, ‘*82

F.2d 1061 (4th Cir.

21, 1974).

t in e a . in eux^y v . ^1973), cert, denied, 42 U.S.L.W. 3423 (Jan.

-36-

duty of the school district is to "eliminate

from the public schools all vestiges of state-

imposed segregation." Swann, supra, 402 U.S.

at 15.

Until the dual system is eliminated "root and

branch," Green v. County School Board of New

Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), the school

district has not conformed to the constitutional

standard set forth by Brown nearly 19 years ago.

. . . All vestiges of state-imposed segregation

have not been eliminated so long as Newburg remains an all black school. Where a school

district has not yet fully converted to a unitary

system, the validity of its actions must be

judged according to whether they hinder or further

the process of school desegregation. The School

Board is required to take affirmative action not only to eliminate the effects of the past but

also to bar future discrimination. Green, supra,

391 U.S. 438 n. 4; Robinson v. Shelby County Board of Education, 442 F.2d 2 55, 2 58 (6th c"ir.

1971). Since the Jefferson County Board has not

eliminated all vestiges of state-imposed segre

gation from the system, it had the affirmative

responsibility to see that no other school in

addition to Newburg would become a racially

identifiable black school. It could not be

"neutral" with respect to student assignments at

Price or Cane Run. It was required to insure

that neither school would become racially identi

fiable. [slip op. at pp. 3-5] 35/

In this case, the district court's retention of Lincoln as

an all-black school was not responsive to specific "practical

problems of desegregation where an otherwise effective plan

for dismantlement of the school system has been adopted,"

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 466 F.2d, at 893. The

35/

and

Seeeast-

resulted

note 34 supra. And see 308a (black Jackson, together with construction

in migration of whites to northwest

schools in south of Andrew Jackson, ); 136a-138a, 143a,

171a.

-37-

plan drawn by Dr. Stolee provided a practical and feasible

method for desegregating both Lincoln and Andrew Jackson

Schools, by pairing and exchanging a total of 453 students

between the facilities (529a). The distance, of 4.9 miles,

took thirteen minutes (314a); the plan ordered into effect by

the district court buses children a similar distance (183a)

but leaves Lincoln all-black, and Andrew Jackson disproportion

ately white in the context of the system-wide ratio.

The factors mentioned by

setting out its "plan" (617a)

justify the results achieved.

the district court just prior to

are all legally insufficient to

The court states:

. . . [W]e have prescribed a plan involving

a minimum of transportation and some elementary

school zone or district changes which this Court

believes will meet constitutional requirements

with the least disruptive effects. This plan

has been fashioned in recognition of the fact,

among others alluded to, that the defendants

in making the progress heretofore noted have

not totally defaulted in their duty to submit an acceptable plan, and because it has never

before operated a bus system as v/as the case in

Swann, supra, and to some degree in Davis,

supra (both in Mobile and in Pontiac), and

because substantial progress has already here

tofore been made.

It is doubtless desirable that desegregation plans involve the

minimum of pupil transportation necessary, e.q., Cisneros v.

Corpus Christi Independent. School Dist., 467 F.2d 142 (5th Cir.

1972), cert. denied, 413 U.S. 920, 922 (1973); Kelley v. Metro

politan County Bd. of Educ., 463 F.2d 732 (6th Cir.), cert.

denied, 409 U.S. 1001 (1972). But the plans must be sufficient

to disestablish all vestiges of the dual system. Kelley, supra

-38-

Newburg Area Council, supra; Northcross, supra. The district

court's personal preference in this case for "a minimum of

transportation" is inexplicable in light of the failure of its