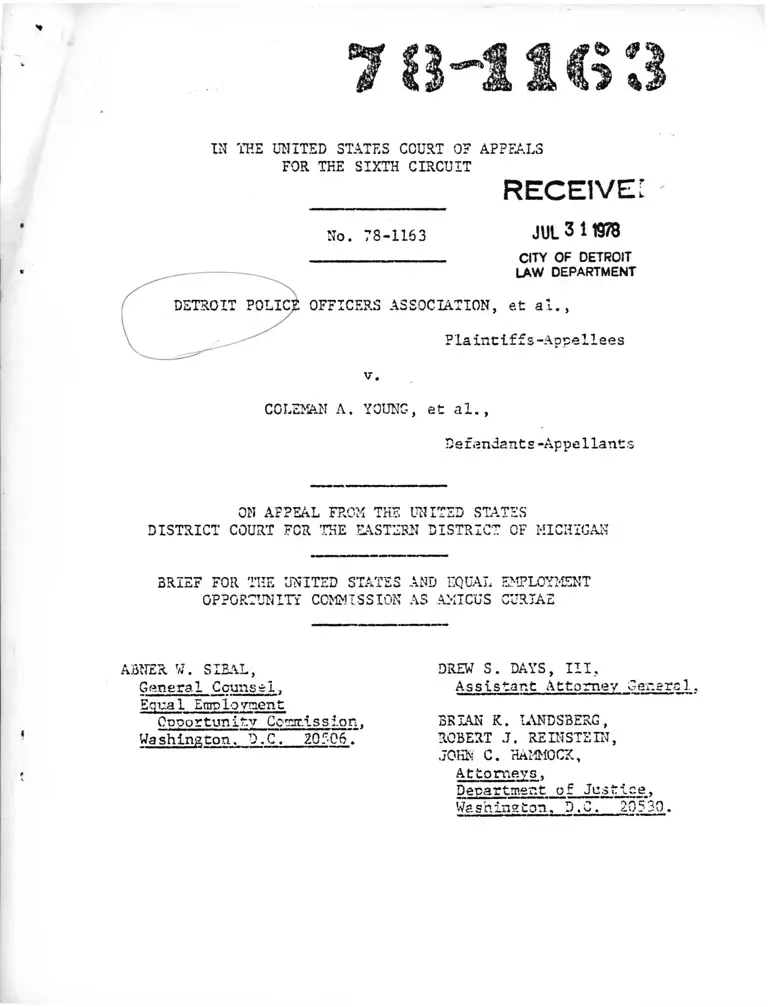

Detroit Police Officers Association v. Young Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

July 31, 1978

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Detroit Police Officers Association v. Young Brief Amicus Curiae, 1978. 494c60ba-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b1cedc62-893c-4f0f-9e3f-28eb993f3875/detroit-police-officers-association-v-young-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

*

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

receive:

Ho. 78-1163 JUL 3 1197B

_________________ CITY OF DETROIT

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES

DISTRICT COURT FCR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AND EQUAL

OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION AS AMICUS

EMPLOYMENT

CURIAE

ABNER W. SIBAL,

General Counsel.

Equal Employment

Opportunity Ccrrjr.ission.

Washington. D.C. 20506.

DREW S. DAYS, III,

Assistant Attorney General.

BRIAN K. LANDSBERG,

ROBERT J. REINSTEIN,

JOHN C. HAMMOCK,

Attorneys.

Department of Justic

Washington, D.C. 20 '-n|

fC

ij. j

*•»

TAELE OF CONTENTS

Interest of the United States and the

Eaual Employment Opportunity Commission ......... 1

Statement ....................................... 2

I. 1943-1967: The Exclusion of Blacks

from the Detroit Police Department

and the Effects of that Exclusion ...... 3

II. 1968-1974: The Police Department’s

Efforts to End Discrimination Against

Blacks in Hiring and Promotions and

to Remedy the Effects of Past Dis

crimination ........................... ^

A. The City's Self Analysis and

Affirmative Action in Hiring,

1968-1974 ......................... 11

3. The City's Self-Analysis and

Affirmative Action in Promo

tions, 1968-1974 .................. 17

1. Dipping ........................ 18

2. Service Rating ................ 19

3. Seniority ..................... 21

4. Written Promotion

Examination ................. 21

5. Oral Boards ................... 27

6. College education and veteran's

preference .................. 28

7. Rank Order .................... 29

8. Summary and results, 1968-

1974 ........................ 32

i

C. The Affirmative Action Pro

motions, 1974-1977 ....... ........ 33

Argument ............................ ............ 38

The Detroit Police Department's Voluntary

Affirmative Action Promotions Are Lawful

Under The Constitution And The Federal

Civil Rights Acts ........................ 38

I. The Federal Civil Rights Acts And

The Constitution Do Not Prohibit,

And Sometimes Require, The Use Of

Race-Conscious Practices To Eliminate

The Effects Of An Employer's Unlawful

Discrimination ....................... 38

II. The Detroit Police Department Practiced

Systematic and Unlawful Past Discrimina

tion Against Blacks In Hiring And

Promotions ...................... , 4 8

A. Past Discrimination in Hiring .... 49

B. Past Discrimination In

Promotions ....................... 56

C. The Prior Discrimination In

Hiring And Promotions Was

Unlawful ......................... 60

III. The Detroit Police Department May

Voluntarily Institute Affirmative

Action To Remedy The Effects Of

Its Past Exclusionary Policy ......... 64

IV. The Particular Race-Conscious Remedy

Adopted By the Detroit Police Depart

ment Did Not Violate The Legal Rights

Of Plaintiffs ..................... 73

A. A Promotion Ratio Is An Appropriate

Method of Remedying Past Discrimina

tion ............................. 73

3. A Promotion Ratio Is Appropriate

To Eliminate The Effects of Past

Discrimination Even If The Depart

ment's Recent Promotional Models

Have Been Validated .............. 75

ii

C. The Particular Promotion Ratio

(50 Percent) Is Appropriate,

But An Ultimate Goal Must Be

Set on Remand ....................

Conclusion ...................................... 90

CITATIONS

Cases:

Afro-American Patrolmen's League v. Duck,

503 F .2d 294 (6th Cir. 1974), affirming

366 F. Supp. 1095 (N.D. Ohio 1973) ........... . 53,57,60

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) ..................... 42,66

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S.

36 (1974) ..................................... 65

Arnold v. Ballard, 12 FEP Cases 1613

(6th Cir. 1976), vacated, 16 FEP Cases

396 (6th Cir. 1976) ....................... ••• 44,76

Associated GeneralContractors of Mass., Inc,

v. Altshuler, 490 F.2d 9 (1st Cir. 1973),

certiorari denied, 416 U.S. 957 (1974) ........ 69,88

Barnett v. International Harvester, 12 FEP

Cases 786 (W.D. Tenn. 1976) ............ -...... 65

Baumgartner v. United States, 322 U.S. 665

(1944) ......................................... 48

Bolden v. Pennsylvania State Police, 73 F.R.D.

370 (E.D. Pa. 1976) ........................... 87

Boston Chapter, NAACP v. Beecher, 504 F.2d

1017 (1st Cir. 1974), certiorari denied,

421 U.S. 910 (1975) ................. .......... 44

3rown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294

(1955) ................................. ....... 68

iii

Cases (continued):

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315

(8th Cir. 1971), certiorari

denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972) ................... 42,45,61,75

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482

(1977) .................................... 48,49,52

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725

(1st Cir. 1972), reversing 334

F. Supp. 930 (D. Mass. 1971) .................. 54

Causey v. Ford Motor Co., 516 F.2d 416

(5th Cir. 1975) ............................ . 48

Chmill v. City of Pittsburgh, 31 Pa. Cmwlth.

98, 375 A.2d 841 (1977) ....................... 66

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883) ........... 62

Crockett v. Green, 534 F.2d 715 (7th

Cir. 1976) .................................... 45

Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 566 F.2d

1334 (9th Cir. 1977), certiorari granted,

No. 77-1553, June 19, 1978 .................... 42,45,62

Dayton Board of Educ. v. Brinkman,

433 U.S. 406 (1977) ........................... 69

Detroit Firefighters Assfn v. City of

Detroit, 17 FEP Cases 186 (E.D.

Mich. 1976), vacated, 17 FEP Cases

190 (6th Cir. 1978) ...................... . 66

Detroit Police Officers Ass'n v. Young,

446 F. Supp. 979 (E.D. Mich. 1978) ............ Passim

Dobbins v. Local 212, I.B.E.W.,

292 F » Supp. 413 (S.D. Ohio 1978) ............ 77

Dothard v. Raw1inson, 433 U.S. 321 (1977) ...... . 54

iv

Cases (continued):

EEOC v. A.T. & T. Co., 556 F.2d 167

(3d Cir. 1977), certiorari denied,

Nos. 77-241-243, July 3, 1978 ....... .......... 44,74,75,87

EEOC v. Contour Chair Lounge, 17 FEP Cases

309 (E.D. Mo. 1978) .......................... . 65

Erie Human Relations Comm, v. Tullio,

493 F .2d 371 (3d Cir. 1974), affirming

357 F. Supp. 422 (W.D. Pa. 1973) .............. 54

Firefighters Institute for Racial Equality

v. City of St. Louis, 549 F.2d 506

(8th Cir. 1977), certiorari denied,

434 U.S. 819 (1977) ........................... 85,86

Franks v. 3owman Transp. Co., 424 U.S.

747 (1976) .................................... 42,46,69,75

Furnco Const. Co. v. Waters, No. 77-369

(U.S. June 29, 1978) ............... ........... 41,70

Germann v. Kipp, 429 F. Supp. 1323

(W.D. Mo. 1977), vacated, 17 FEP Cases

72 (8th Cir. 1978) ............................ 65

Green v. Countv School Board, 391 U.S. 430

(1968) ...................................... .. 41,67,71

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424

(1971) ....................................... . 39,62

Hazelwood School Dist. v. United States,

433 U.S. 299 (1977) .......................... . 49,51,52,61

Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1976) ......... 42

Hutchinson Commission v. Midland Credit

Management, Inc., 213 Kan. 399, 517 P.2d

158 (1973) ..... .............................. . 39,65

v

Cases (continued):

Int'l Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) ................... 49,51,56,69

Jackson v. Dukakis, 526 F.2d 64

(1st Cir. 1975), affirming 394

F. Supp. 162 (D. Mass. 1975) ......... ......... 53

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc.,

421 U.S. 454 (1975) ........................... 61

Johnson v. Ryder Truck Lines, 17 FEP Cases

571 (4th Cir. 1978) ........................... 62

Jones v. Alfred Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409

(1968) ........................................ 61,62

Kirkland v. Dept, of Correctional Services,

520 F .2d 420 (2d Cir. 1975), certiorari

denied, 429 U.S. 823 (1976) ................... 44,74,75,85

Lindsay v. City of Seattle, 86 Wash. 2d 698,

548 P.2d 320 (1976), certiorari denied,

429 U.S. 886 (1976) ......................... . 39,65

Long v. Ford Motor Co., 496 F.2d 500

(6th Cir. 1974) ...................... .. ....... 61

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145

(1965) ......................................... 41,76

McDaniel v. 5arresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971) ......... 41,69,71

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Trans. Co.,

427 U.S. 273 (1976) ........................... 40

McDonnell-Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S.

792 (1973) .................................... 41,70

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) ....... 68

Morgan v. Kerrigan, 509 F„2d 599 (1st

Ciro 1975) ........................... ......... 44

vi

Cases (continued):

Morrow v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir.

1974), certiorari denied, 419 U.S. 895

(1974) ....................................... 44,45

NAACP v. Allen. 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir.

1974) ......................................... 44

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) ......... 48

North Carolina Bd. of Educ. v. Swann,

402 U.S. 43 (1971) ............................ 46

Officers for Justice v. Civil Service Comm.,

371 F. Supp. 1328 (N.D. Cal. 1973) ............ 87

Fapermakers and Paperworkers, Local 189 v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir.

1969) , certiorari denied, 397 U.S. 919

(1970) ........................................ 74

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 535 F.2d

257 (4th Cir. 1976), certiorari denied,

429 U.S. 920 (1976) ............... ............ 44

Patterson v. Newspaper Deliverers* Union,

514 F .2d 767 (2d Cir. 1975), certiorari

denied, 427 U.S. 911 (1976) .................. 44,75,87

Pomoey v. General Motors Corp. 385 Mich.

537, 189 N.W. 2d 243 (1971) ................ .... 61

Porcelli v. Titus, 431 F.2d 1254 (3d Cir.

1970) , certiorari denied, 402 U.S.

944 (1971) .................................... 65,69

R,eeves v. Eaves, 411 F. Supp. 531 (N.D. Ga.

1976) 66

Reed v. Lucas, 11 FEP Cases 153 (E.D.

Mich. 1975) ........................ ........... 87

vii

Cases (continued):

Regents of the Univ. of Calif, v. Sakke,

No. 76-811 (U.S. June 28, 1978) ............... 45,46,47,74

Rios v. Steamfitters, Local 638. 501 F.2d

622 (2d Cir. 1974) .......................... . 44,88

Robinson v. Union Carbide Corn., 538 F.2d

652 (5th Cir. 1976) ........................... 58

Schaeffer v. Tannian, 394 F. Supp. 1128

(E.D. Mich. 1974) ............................. 29,34

Senter v . General Motors Corn., 532 F.2d

511 (6th Cir. 1976), certiorari denied,

429 U.S. 870 (1976) ... ......................... 49

Sims v. Sheet Metal Workers Local 65.

489 F.2d 1023 (6th Cir. 1973) ................. 44

Stamps V. Detroit Edison Co.. 365 F. Supp.

87 (E.D. Mich. 1973), affirmed sub nom.

ELCC v. Detroit Edison Co.. 515 F.2d 301

(6th Cir. 1975), vacated, 431 U.S. 951 (1977) .. Passim

Stewart v. General Motors Corp., 542 F.2d

445 (7th Cir. 1976), certiorari denied,

433 U.S. 919 (1977) ........................... 58

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of

Edue.. 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ...................... 41,42,46,68,69,71

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburg

v. Carev. 430 U.S. 144 (1977) ................. 69,71

United States v. Alleghenv-Ludlum Industries.

517 F .2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975), certiorari

denied, 425 U.S. 944 (1976) ................... 65

United States v. City of Chicago. 549 F.2d

415 (7th Cir. 1977), certiorari denied,

434 U.S. 875 (1977) ........................... 44,74

United States v. City of Chicago, 573 F.2d

416 (7th Cir. 1978) ........................... 85,86,87

vii i

Cases (continued):

United States v. Duke, 332 F.2d 759 (5th

Cir. 1964) .................................... 76

United States v. Elevator Constructors,

Local 5, 538 F.2d 1012 (3d Cir. 1976) ......... 44

United States v. I.B.E.W.. Local 38,

428 F .2d 144 (6th Cir. 1970),

certiorari denied, 400 U.S. 943 (1970) ........ 43,44,45

United States v. Ironworkers, Local 86,

443 F.2d 544 (9th Cir. 1971), certiorari

denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971) .................. . 45

United States v. Jefferson County Bd.

of Educ., 372 F .2d 836 (5th Cir.

1966) , opinion adopted by court,

380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir.

1967) , certiorari denied, 389 U.S.

840 (1967) ..................................... 42

United States v. Lathers, Local 46,

471 F .2d 408 (2d Cir. 1973),

certiorari denied, 412 U.S. 939

(1973) ......................................... 73

United States v. Local 1, Bricklayers,

5 E.P.D. Para. 8480 (W.D. Tenn. 1972-73),

affirmed, 497 F.2d 871 (6th Cir. 1974) ........ 77

United States v. Local 169, Carpenters,

457 F.2d 210 (7th Cir. 1972),

certiorari denied, 409 U.S. 851 (1972) ........ 45

United States v. Local 212, I.B.E.W.,

5 E.P.D. para. 8428 (S.D. Ohio 1972),

affirmed, 472 F.2d 634 (6th Cir. 1973) ........ 77

United States v. Local 212. I.B.E.W.,

472 F.2d 634 (6th Cir. 1973) .................. 43,77

ix

Cases (continued):

United States v. Masonry Contractors Ass'n,

Inc., 497 F.2d 871 (6th Cir. 1974) ............. 44,77 '

United States v. N.L. Industries. Inc.. 479 F.2d

354 (8th Cir. 1973) ............................ 45,66,74,87

United States v. Solomon, 563 F.2d 1121

(4th Cir. 1977) ................................ 61

United States v. United States Gypsum Co.,

333 U.S. 364 (1948) ............................ 49

United States v. United States Steel Corn.,

5 FEP Cases 1253 (N.D. Ala. 1973), affirmed;

520 F .2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1975), certiorari

denied, 429 U.S. 817 (1976) .................... 87

Vulcan Society v. New York Civil Service

Comm,, 360 F. Supp. 1265 (S.D. N.Y. 1973),

affirmed 490 F.2d 387 (2d Cir. 1973) ........... 85,86

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ......... 40,61

Waters v . Wisconsin Steel Works Co.,

427 F .2d 476 (7th Cir. 1970),

certiorari denied, 400 U.S. 911

(1970) .......................................... 61

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d

1159 (5th Cir. 1976), certiorari denied,

429 U.S. 861 (1976) ............................ 44,45,58,74

Weber v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical

Corp., 563 F.2d 216 (5th Cir.

1977) . 47,65,67

Young v. Int’l Telephone & Telegraph Co.,

438 F .2d 757 (3d Cir. 1971) .....................61

x

Constitution, statutes and regulations:

Constitution of the United States of America,

Fourteenth Amendment ..................... 39,42,61

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VI, 78 Stat.

252 et sec., 42 U.S.C. 20Q0d et seq. ..... 39,42,61

Section 602, 42 U.S.C. 2000d-l ........ 65

Section 604, 42 U.S.C. 2000d-3 ........ 61

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII, 78 Stat

253 et sec., 42 U.S.C. 2000e et seq. , ....Passim

Section 706(b), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(b) ... 65

Section 706(f)(1), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5

(f)(1) .............................. 1»65

42 U.S.C. 1931 ...............................Passim

42 U.S.C. 1983 ............................. 70,71

Michigan Civil Rights Act (1977),

Section 37.2101 et seq. ................63

Michigan Fair Employment Practices Act,

M.C.L.A. (1972):

Section 423.301 et: seq................. 61

Section 423.302(b) ................... 61

29 C.F.R. 1607.5(a) ........................85,86

45 C.F.R. 80.3(b)(6)(i) ....................46

45 C.F.R. 80.3(b)(6)(ii) ...................46

45 C.F.R. 80.5(i) ..........................46

Miscellaneous:

American Psychological Association,

STANDARDS FOR EDUCATIONAL AND

PSYCHOLOGICAL TESTS (1964) ............... 85,86

ENA Labor Relations Reporter, Fair

Employment Practices Maunel 455:

1091-1095 ................................ 63

xi

Miscellaneous (continued):

Edwards, THE POLICE ON THE URBAN FRONTIER

(1968) ........................ ........... 8,9,17

Edwards. Order & Civil Liberties: A

Complex Role for the Police, 64 Mich.

L. Rev. 47 (1965) ........................ 3,18

W. Harrison, THE DETROIT RACE RIOTS (1943) .. 4

Policy Statement on Affirmative Action

Programs for State and Local Govern

ment Agencies, 41 Fed. Reg. 38814

(1976) ................................... 66

President's Commission on Law Enforcement

and Administration of Justice, THE

CHALLENGE OF CRIME IN A FREE SOCIETY

(1967) ................................... 7,8

President's Commission on Law Enforcement

and Administration of Justice, TASK

FORCE REPORT: THE POLICE (1967) ......... 4,5,6,8

Proposed EEOC Guidelines on Remedial

And/or Affirmative Action, 42 Fed.

Reg. 64826 (1977) .......... •............. 47,66

REPORT OF THE NATIONAL ADVISORY COMMISSION

ON CIVIL DISORDERS (1968) ................ 4,7,8,9

R. Shogan & T. Craig, THE DETROIT RACE

RIOT (1964) .............................. 3,4

U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1940 CENSUS

OF POPULATION, Vol. II, Part 3 ........... 4

U.S. Civil Rights Commission, ADMINISTRATION

OF JUSTICE STAFF REPORT (1963) ........... 6,11

U.S. Civil RightsCommission, HEARINGS

BEFORE THE UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON

CIVIL RIGHTS, HEARINGS HELD IN DETROIT,

MIGHICAN DECEMBER 14, 15, 1960 ........... 18

xii

Miscellaneous (continued):

U.S. Dept, of Commerce, Bureau of the

Census, 1950 CENSUS OF POPULATION,

Vol. II, Part 22 ....................... .. 4

U.S. Dept, of Commerce, Bureau of the

Census, 1960 CENSUS OF POPULATION,

Vol. I, Part 24 .......................... 5

U.S. Dept, of Commerce, Bureau of the

Census, 1970 CENSUS OF POPULATION ........ 6

W. White 6c T. Marshall, WHAT CAUSED THE

DETROIT RIOT? (1943) .................... 4

xiii

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 78-1163

DETROIT POLICE OFFICERS ASSOCIATION, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees

v.

COLEMAN A. YOUNG, et al. ,

Defendants-Appellants

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES

DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AND EQUAL EMPLOYMENT

OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION AS AMICUS CURIAE

-1-

INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES

AND THE EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION

Federal enforcement of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 has been vested by Congress in the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and the Department of Justice.

The EEOC has the responsibility to investigate charges of

employment discrimination, to attempt voluntary conciliation

and, if necessary, to bring civil actions against private

employers under 42 U.S.C. (Supp. V) 2000e—5(f)(1). The

Attorney General has enforcement responsibility when the

employer is a state government, governmental agency, or

political subdivision. 42 U.S.C. (and Supp. V) 2000e-6. In

discharging these federal enforcement responsibilities, the

Government relies, in substantial part, on encouraging

employers to self-evaluate their employment practices and to

voluntarily adopt affirmative, corrective action to increase

the participation of minorities in jobs that were formerly

closed to them.

This case raises important questions concerning the

legality of voluntary affirmative action by a public employer

that sought to rectify the exclusionary effects of its past

racial discrimination. The resolution of these questions

may significantly impact on federal enforcement of Title VII.

The United States and Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

file this brief as amicus curiae in support of reversal of

the district court's decision.

-2-

S TATEM ENT_1 /

This lawsuit challenges a voluntary affirmative action

program instituted by the Detroit Police Department in 1974.

In order to remedy the effects of its own past discrimination

against blacks, the department decided to accelerate the pro

motions of qualified black police officers to the rank of

sergeant. When this affirmative action plan began in 1974,

only 61 of the department's 1185 sergeants (5.1 percent) were

black, although the City of Detroit was approximately 50 per

cent black and the department as a whole was 17.2 percent

black. 2/ Between 1974 and 1977, 160 whites and 152 blacks

were promoted to sergeant; this result was achieved by

departing from strict rank order on the eligibility lists so

that promotions of police officers would be roughly in a

ratio of one qualified black for each qualified white. 3/ By

the end of 1977, the sergeants' rank was 15.1 percent

black. 4/

The district court's opinion accurately describes the

procedures which were followed in promoting sergeants between

1/ This appeal is proceeding on a deferred appendix.

References are to the transcript ("Tr.", followed by the date

and page of testimony and identification of witness), Plain

tiffs' Exhibits ("PX"), Defendants' Exhibits ("DX"), and the

district court's opinion, reported at 446 F. Supp. 979 (E.D.

Mich. 1978).

2/ 446 F. Supp. at 994 n. 29, 995-996.

_3/ Id., 987-989.

4/ DX 264.

-3-

1974 and 1977. 5/ However, the opinion does not relate

accurately the historical facts and reasons which impelled

the police department to begin promoting on a race-conscious

basis. The district court disregarded almost entirely the

massive and largely undisputed evidence of past, systematic

discrimination against blacks in hiring and promotions; the

extensive self-analysis undertaken by the department over a

period of years; and the failure of less drastic remedies to

eliminate the continuing effects of the department's past

exclusionary policies. Because of the district court's

failure to address fully the evidence, and in light of the

size of this record, it is necessary to set forth the facts

at unusual length.

I. 1943-1967: The Exclusion Of Blacks From The

Detroit Police Department And The Effects of

_________ That Exclusion_____________________

In 1943, when the first Detroit race riot occurred, the

city's police department was virtually all white and

segregated. 6/ There was "open warfare between the Detroit

5/ 446 F. Supp. at 986-988.

6/ See generally Robert Shogan & Tom Craig, THE DETROIT

RACE RIOT (1964); Walter White & Thurgood Marshall, WHAT

CAUSED THE DETROIT RIOT? (1943). Writing in 1965, Judge

George Edwards reviewed the 1943 Detroit riot and subsequent

riots in other cities, and concluded that "hostility between

the Negro communities in our large cities and the police

departments is the major problem in law enforcement in this

decade. It has been a major cause of all recent race riots."

Edwards, Order and Civil Liberties: A Complex Role for the

Police, 64 Mich. L. Rev. 47, 54-55 (1965).

(continued)

-4-

Negroes and the Detroit Police Department." 7/ In the wake

of the 1943 riot, responsible observers emphasized the

necessity of integrating the Police Department. 8/ But this

did not occur. Over the next decade, the black population of

Detroit rose beyond 16 percent; 9/ between 1944 and 1953, the

Department hired 3,122 police officers— 3,005 whites and 117

blacks (3.7 percent). 10/ In 1953, the Department was only

2.4 percent black. 11/ The small number of black officers in

6/ (Continued)

According to former Commissioner Nichols, there was a

"minimal number" of blacks in the Detroit Police Department

in 1942. Tr. 8/10/77, 41. At the time of the 1943 riot, the

Department had only 4 3 black officers out of- a total complement of

3400, R. Shogan & T. Craig, supra at 42, 70. To control the riot,

the Police Department activated a "Negro auxiliary", a volunteer

group of some 200 untrained and unarmed black citizens. Id., at

72, 109.

7/ REPORT OF THE NATIONAL ADVISORY COMMISSION ON CIVIL

DISORDERS 48 (1968) (hereinafter cited as "KERNER COMMISSION

REPORT").

8/ See, e.g., Walter White & Thurgood Marshall, supra note

6 at 17"(We recommend that the number of Negro officers be

increased from 43 to 350; that there be immediate promotions

of Negro officers in uniform to positions of responsibility

* * * *"); Robert Shogan & Tom Craig, supra note 6 at 116; Walter R.

Harrison, THE DETROIT RACE RIOTS 11-12, 16 (1943).

9/ U. S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 1950

CENSUS OF POPULATION, Vol. II, part 22, Table 33 (reporting

that minorities constituted 16.4 percent of Detroit's

population in 1950). The Detroit SMSA (Wayne, Oakland and

Macomb Counties) was 12.0 percent minority in 1950. Ibid.

Ten years earlier, the City of Detroit was 9.2 percent black;

and the Detroit Metropolitan District was 7.4 percent black.

U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1940 CENSUS OF POPULATION, Vol.

II, Part 3 (Michigan), Tables 34 & A-45.

10/ DX 208, p. 5.

11/ The President's Commission on Law Enforcement and

Administration of Justice, TASK FORCE REPORT: THE POLICE 172

(1967) .

-5-

the Department were given segregated job assignments. 12/ And

the exclusion of blacks from the supervisory ranks was even

more severe; 0.7 percent of all officers at the rank of

sergeant or above were black. 13/

The same pattern continued for another decade. Between

1954 and 1962, the Department hired 1,663 white and 68 black

(3.9 percent) police officers. 14/ By the end of 1962, the

Department was only 3.5 percent black; the supervisory ranks

(sergeant and above) were only 1.1 percent black; 15/ while

the City of Detroit was over 29 percent black. 16/ A 1962

United States Civil Rights Commission study found that blacks

12/ As late as 1962, the Police Department admitted to the

U. S. Civil Rights Commission that assignments were made on a

racial basis. Id., at 174. Numerous witnesses who were on

the police force in the 1940's, 1950's and 1960's testified

that racial segregation in job assignments was a reality until

the early 1960's. See, e.g., Tr. 8/10/77, 55-58 (former Commis

sioner Nichols); 11/4/77, 23-29, 50-51 (Executive Deputy Chief

Bannon); 11/2/77, 9-14 (Chief Hart); 11/15/77, 7-19 (Officer

Baldwin; id., 40-46 (former Sgt. Stewart).

13/ There were 344 white and 3 black sergeants, 167 white

and 1 black lieutenant, and 42 whites and no black above the

rank of lieutenant in 1953. TASK FORCE REPORT: THE POLICE,

supra note 11 at 172.

14/ DX 208, p. 5.

15/ TASK FORCE REPORT: THE POLICE, supra note 11 at 172.

(There were 340 white and 5 black sergeants, 152 white and 1

black lieutenants, and 56 whites and no black above the rank

of lieutenant) .

16/ U. S. Dept, of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 1960

CENSUS OF POPULATION, Vol. I, Part 24, Table 21. The Detroit

SMSA was 14.9 percent black by 1960. Ibid.

-6-

were excluded from the Detroit Police Department because of

both intentional discrimination and the effect of the written

entrance examination.17/ Formal racial segregation in job

assignments continued until the early 1960's.18/

In February of 1967, the President's Commission on Law

Enforcement and Administration of Justice concluded that

minorities were grossly under-represented in the police

departments of most large cities and that discrimination

against minority applicants was prevalent, singling out

Detroit as a case in point.19/ The population of Detroit was

approaching 44 percent black,20/ but there were only 214

blacks on the 4,356 member police department (4.9 percent

black).21/ The President's Commission also found that

"[t]here is an even more marked disproportion of minority

group supervisory personnel than of minority group officers

generally throughout the police service" of major cities,_22/

and that "there is evidence that discrimination is practiced

against minority group officers, perhaps more in promotion

17/ U.S. Civil Rights Commission, ADMINISTRATION CF JUSTICE

STAFF REPORT ch. 11, 8-16 (1963), summarized in TASK FORCE

REPORT: THE POLICE, supra note 11 at 169.

18/ See note 12, supra.

19/ TASK FORCE REPORT: THE POLICE, supra note 11 at

167-171.

20/ U.S. Dept, of Commerce, Bureau of Census, 1970 CENSUS OF

POPULATION, Vol. I, Part 24, Table 23. The Detroit SMSA was

18.0 percent black in 1970. Ibid.

21/ DX 208, pp. 3, 5 (data for end of 1967).

22/ TASK FORCE REPORT: THE POLICE supra note 11 at 171.

-7-

than in recruitment."23/ The supervisory ranks of the

Detroit Police Department were then approximately 2.1 percent

black.24/

The President's Commission concluded that the exclusion

of minorities from police departments had created a crisis in

law enforcement. The relations between the police and

minority communities "is as serious as any problem the police

have today."25/ These relations could not be improved until

there is ”a sufficient number of minority-group officers at

all levels of activity and authority."26/

"Police departments in all communities

with a substantial minority population

must vigorously recruit minority group

officers. The very presence of a pre

dominantly white police force in a

Negro community can serve as a

dangerous irritant * * *. In

neighborhoods filled with people

suffering from a sense of injustice

and exclusion, many residents will

reach the conclusion that the

neighborhood is being policed not for

the purpose of maintaining law and

order but for the purpose of

maintaining the status quo.

23/ Id., at 172.

24/ KERNER COMMISSION REPORT, supra note 7 at 169 Table A

(data for October, 1967).

25/ The President's Commission on Law Enforcement and

Administration of Justice, THE CHALLENGE OF CRIME IN A FREE

SOCIETY 99 (February, 1967).

26/ Id., at 101.

I

"In order to gain the general

confidence and acceptance of a

community, personnel within a police

department should be representative of

the community as a whole. * * *"27/

The President's Commission set as a "high priority objective"

for all police departments "in communities with a substantial

minority population to recruit minority-group officers, and

to deploy and promote them fairly."28/ And in the area of

promotions, "more than nondiscrimination" was necessary "to

overcome the legacy of the past."29/ The Commission

advocated a number of race-conscious remedies to meet the

"urgent need for high-ranking minority officers," including

the deliberate "exercise of * * * discretion" to promote

minorities.30/ And finally, emphasizing the immediacy of the

problem, the Commission warned that "everyday police

encounters in [minority] neighborhoods can set off riots."31/

On the evening of July 22, 1967, "everyday police

encounters" in black areas of Detroit triggered the second

Detroit race riot.32/ During the next five days, 43 people

-8-

27/ TASK FORCE REPORT, supra note 11 at 167. See also G.

Edwards, THE POLICE ON THE URBAN FRONTIER 86 (1968).

28/ THE CHALLENGE OF CRIME IN A FREE SOCIETY, supra note 25

at 102. See also G. Edwards, supra note 27 at 40, 86.

29/ TASK FORCE REPORT, supra note 11 at 173.

30/ Ibid.

31/ THE CHALLENGE OF CRIME IN A FREE SOCIETY, supra note 25

at 99.

32/ KERNER COMMISSION REPORT, supra note 7 at 47-59.

-9-

were killed, hundreds were injured, thousands were arrested,

large portions of Detroit were devastated, and the army

occupied the city.33/ A principal cause of this and the

other riots during that summer was the hostility between the

police and the black community— a hostility caused in large

measure by the exclusion of blacks from all ranks of the

police.34/

II. 1968-1974: The Police Department's Efforts

to End Discrimination Against Blacks in Hiring

and Promotions and to Remedy the Effects of

____________Past Discrimination________________

The second Detroit race riot had a traumatic effect on

the City and its police force. There was extreme distrust

between the black community and an "essentially * * * white"

police department.35/ By the end of 1967, the department was

only 4.9 percent black.36/ At the supervisory ranks, blacks

accounted for only 2.6 percent of the sergeants (9 of 348),

1.3 percent of the lieutenants (2 of 158), and 1.6 percent of

the officers above the rank of lieutenant (1 of 63).31/ The

Mayor stated that it had finally become "obvious to me and to

33/ _Id_!_ at 60-61.

34/ Id. at 165-169. See also note 6 supra, and G. Edwards,

supra note 27 at 35 ("[T]he conflict between Negroes and the

police actually is a conflict between two of the most

segregated groups in American society.").

35/ Tr. 8/8/77, 68, 87 (Johannes Spreen, Police Commissioner

between 1968 and 1970).

36/ DX 208, pp. 3, 5 (214 blacks of 4,356).

37/ KERNER COMMISSION REPORT, supra note 7 at 169 Table A.

-10-

this entire community, that this proportion of Negro

policemen was clearly unacceptable."38/ The Department

understood that its "biggest problem to try to overcome" was

the polarization between itself and the black community39/

and that it was essential to rectify the under-representation

of blacks at all ranks.40/ The Police Department knew that

blacks had been "excluded" during all of the years until 1968

and that "there was some form of discrimination effectively

working during those years."41/The City then began to

undertake actions in both the hiring and promotion areas,

which span a six year period (1968-1974) and are recounted

below. The City's initial objective was to determine the

reasons why blacks were so grossly under-represented in the

department. It then implemented a series of steps to

eliminate existing racially discriminatory barriers and to

rectify the effects of past discrimination.

38/ PX 106, p. 17 (statement of Mayor Cavanagh).

39/ Tr. 8/8/77, 87 (former Commissioner Spreen).

40/ Id., 76, 89-91. Commissioner Spreen's objective was

that the Department should be racially reflective of the

City. ("I think any enlightened Chief of Police or

Commissioner would prefer that, if he could have that." Id.,

89-90). See also Tr. 8/9/77, 21-22 (former Commissioner

Nichols).

41/ Tr. 8/24/77, 22; 8/25/77, 63 (Commander Caretti,

director of recruiting). Johannes Spreen, who was Police

Commissioner in 1968, testified that "I made inquiry as to

what possibly could have been the cause [of so few blacks in

the department]. One of the causes was an exclusion policy

and I made certain that there was none when I was the

Commissioner." Tr. 8/8/77, 77. But cf. _id., 79.

-11-

A. The City's Self Analysis and Affirmative

Action in Hiring, 1968-1974__________

In May, 1968, Mayor Cavanagh announced the beginning of

an intensive campaign to recruit black applicants for the

Police Department.42/ The Mayor also appointed a Special

Task Force to determine why blacks were under-represented in

police hiring. The Task Force found initially that 47

percent of police applicants in 1967 were black, a figure

greater than the black proportion of Detroit's population, a

finding which "exploded” the "myth" that blacks "do not want,

nor are they willing, to join the Police Department."43/ The

Task Force also found that black applicants were disporpor-

tionately rejected: (1) at the preliminary application stage

for "'miscellaneous' reasons"; (2) at the written examination

stage; and (3) at the background investigation and oral inter

view stages "where subjective opinions are critical."44/

Mayor Cavanagh also appointed a committee of seven

prominent industrial psychologists and personnel selection

experts (the "Vickery Committee") to examine the present

selection standards and to make recommendations for the

development of non-discriminatory and valid standards.45/

42/ PX 106, p. 20. The recruitment efforts are fully

described in the district court opinion, 446 F. Supp. at

997-998.

43/ PX 106, p. 45.

44/ Ibid. Compare the 1962 U.S. Civil Rights Commission

staff study, supra note 17.

45/ PX 106, p. 3; Tr. 8/11/77 24, 36 (Commander Caretti, who

worked with the Vickery Committee).

-12-

The Vickery Committee found that many of the qualifications

at the preliminary screening stage were not relevant and

recommended changes.46/ It also found that the entry-level

test used up to that time (a three-hour IQ test) was "very

bias[ed]" against blacks,47/ and a validation study showed

that there was no relationship between scores on the test and

job performance.48/ The Vickery Committee recommended that

the 12-minute Wonderlic IQ test should be used as an interim

measure until a validated test could be obtained.49/ The

Committee knew that the Wonderlic test discriminated against

blacks and that there was a body of knowledge repudiating

this test as a predictor of job performance,50/ but it hoped

that as an interim measure the Wonderlic would have a lesser

adverse impact against blacks.51/ The changes recommended by

the Vickery Committee were instituted in 1968,52/ and the

46/ PX 106, pp. 3-6.

47/ Tr. 8/11/77, 24 (Caretti). Three times as many blacks

failed this test as whites (DX 294, pp. 14-15).

48/ PX 106, pp. 6-7. This result was not surprising. As

Caretti stated, "no one has been able to establish a relation

ship between IQ and [job] performance" (Tr. 8/11/77,46).

49/ Tr. 8/11/77, 24-25 (Caretti).

50/ Tr. 8/24/77, 25-28 (Caretti).

51/ Id., 28. Caretti explained that "it's important to

understand that the Vickery Committee did not want to come in

and move with a hatchet, so to speak, to try and correct and

change the system. They were cautious. * * * [T]here was no

opinion in the Vickery Committee that would support Wunder

lich [sic]. It was strictly an interim measure to try and

improve the process." Ibid.

52/ Tr. 8/18/77, 15 (Caretti); Tr. 8/8/77, 83 (Spreen).

-13-

applications of blacks were processed on an expedited

basis.53/ Between 1968 and 1970, the hiring rate of blacks

increased to 26% (408 out of 1575),54/ and the Police Depart

ment was 11.0% black by the end of 1970.55/ However, black

applicants were still being rejected at a highly dispropor

tionate rate, because about 50% of the applicants between

1968 and 1970 were black.56/ Blacks failed the entrance-

level IQ tests at a much greater rate than whites.57/ This

was also true of the medical examination and background

investigation.58/

In 1971, as a result of another recommendation from the

Vickery Committee, the "Chicago battery" test was

53/ Tr. 8/8/77, 125 (Spreen).

.54/ DX 208, p. 4.

55/ DX 208, pp. 3, 5 (568 blacks of 5158).

56/ Tr. 8/8/77, 81-84 (Spreen); 10/31/77, 27 (Sgt.

Broadnax). The Police Community Relations Project Committee

reported in 1970 that 47 percent of the applicants in 1969

were black (DX 294, p. 11). This committee included civic

and business leaders, a federal and a state judge, high

ranking police officers, and the president and vice-president

of Plaintiff-Appellee Detroit Police Officers Association

(^d., pp. 9-10). The committee stated: "The fact that 47 percent

of all police applicants in 1969 were black shatters the myth

that the black community is less interested in law

enforcement and destroys a conclusion, held by some, that

blacks are less interested in a police career." (Id., p.

11) .

57/ On the Wonderlic IQ test, used in 1968, only 30% of

black applicants passed, compared to 70-80% of white appli

cants. Tr. 8/24/77, 24-27 (Caretti); in 1969 and 1970,

approximately 40% of black applicants and approximately 80%

of white applicants passed the IQ tests (PX 190, p. 42).

58/ Tr. 8/24/77, 35-38 (Caretti).

-14-

ins tituted. 59/ This battery included both job-related and IQ

components, 60/ and was used until 1973. 61/ This reduced but

did not eliminate the disparity between the passing rates of

whites and blacks. 62/ The Police Department also critically

examined the background investigation and medical procedures

because blacks continued to be rejected at higher rates than

whites. 63/ The background investigators could choose whom

they wanted to investigate, 64/ sergeants could reject appli

cants on the recommendation of investigators even before the

investigation was completed, 65/ and the time for investigat

ing blacks was substantially longer than whites with similar

backgrounds. 66/ These practices were ended, and the racial

disparity in rejection rates was substantially reduced.67/

The major problem at the medical stage was that 80

59/ PX 190, p. 42; Tr. 8/11/77, 45 (Caretti).

60/ Tr. 10/27/77, 15-16 (Commander Ferrebee); Tr. 8/19/77, 4

Tcaretti).

61/ Tr. 8/19/77, 5 (Caretti).

62/ PX 190, p. 42 (between 1971 and 1973, passing rates on

"Chicago battery" were 59.2% for blacks and 82.5% for whites).

6_3/ Tr. 8/24/77, 35-38, 42-43 (Caretti); Tr. 10/13/77, 26-29 ,

6 8 (Broadnax) .

64/ Tr. 10/31/77, 35 (Broadnax); Tr. 10/26/77, 33 (Ferrebee).

65/ Tr. 10/26/77, 44-46 (Ferrebee).

66/ Id., 31-32, 98-100.

67/ Investigations were assigned on a "blind draw" basis_(Tr.

To/ 31/77, 35 (Broadnax); Tr. 10/26/77, 33 (Ferrebee)); rejections

could be made only by a lieutenant or commander (Tr. 10/26/77,

45-46 (Ferrebee)); irresponsible investigators were transferred

(id., 41); and the background investigation unit was integrated

(Id., 42) .

-15-

percent of psychiatric rejectees were black, and the

psychiatrist refused to give reasons or document the

rejections.68/ A new psychiatrist was appointed who docu

mented all rejections; the result was to reduce significantly

the rejection rate of blacks, and many black applicants who

had been rejected were reevaluated and accepted.69/

As a result of the above changes instituted successively

in 1971-1973, the hiring rate of blacks increased to about 30

percent.70/ In late 1973, the Police Department began using

an entrance test developed by John Furcon of the University

of Chicago, who had been retained by the Vickery Committee to

construct a validated test.71/ The City was satisfied that

this test was appropriately validated,72/ and black and white

68/ Id., 28-30.

69/ Id., 30-31; Tr. 10/31/77, 54 (Broadnax). Another

problem at the medical stage was that blacks who barely

passed the height and weight standards were reexamined, but

this was not required of whites (Tr. 10/26/77, 25

(Ferrebee)).

70/ DX 208, p. 4.

71/ Tr. 8/11/77, 43-45; 8/18/77, 28 (Caretti). The goal of

the Vickery Committee was "to develop a fair, equitable test

that would measure or predict job performance, and would also

reduce and, if at all possible, eliminate the cultural biasis

[sic] that were part of previous practices." Tr. 8/11/77, 36

(Caretti).

72/ Tr. 8/16/77, 12 (Caretti). The City's expert consult

ants on the Vickery Committee examined the empirical

validation data and concluded that the test was validated.

Id., 13-14. Furcon's test was differentially validated—

different passing scores are used for black and white appli

cants in order to predict the same probability of job per

formance by both groups. Tr. 8/11/77, 45; 8/17/77, 31-32;

8/24/77, 43-47 (Caretti). The minimum passing level was set

higher than the reading and writing abilities of incumbent

police officers. Tr. 8/25/77, 49-51 (Caretti).

-16-

applicants passed at about the same rate.73/ The result of

using this test, as well as the other changes in selection

described above, was that blacks and whites were hired in

equal numbers in 1974.74/

As a result of the City's affirmative action efforts in

hiring, black representation on the Police Department

increased from 4.9 percent at the end of 1967 to 17.2 percent

in 1974.75/ The City's ultimate goal since 1968 has been

that the department should ultimately be 50 percent black and

i

thereby reflect the City's population.76/ By the end of

1977, the department was 32 percent black.77/

73/ PX 190, p. 42.

74/ Tr. 10/26/77, 67-71 (Ferrebee); Tr. 8/25/77, 54

(Caretti).

75/ DX 208, p. 3 (data for June 13, 1974).

76/ This goal was held by Commissioner Spreen in 1968 (Tr.

878/77, 90-91) and was formally adopted as the City's policy

by Mayor Gribbs in 1971. Tr. 10/27/77, 25 (Ferrebee). Mayor

Young endorsed this policy both before and after his election

in 1973. Tr. 8/26/77, 17-19 (Chief Tannian).

77/ In 1974, the City also imposed a pre-application

residency requirement because there were enough qualified

applicants living in Detroit. PX 190, pp. 31-32. The effect

of this policy has been to reduce the percentage of white

applicants. Also, since 1968, black applicants have been

processed on an expedited basis "in response to the

conditions to try and correct the problems of the past." Tr.

8/25/77, 29 (Caretti); see also pp. 12-13, supra. Beginning

in late 1973, the City created two hiring lists by race and

exhausted the list of blacks before hiring whites, Tr.

10/27/77, 19-25 (Ferrebee), although there is no evidence of

the number of whites (if any) who were not hired because of

this procedure. In 1977, 60-70 percent of the applicants

were black, and 80 percent of those hired were black. Tr.

10/28/77, 37 (Ferrebee).

-17-

B. The City's Self-Analysis and Affirmative

Action in Promotions, 1968-1974______

As previously noted, the under-representation of blacks

historically has been even more severe at the supervisory

ranks (sergeant and above) than in the Police Department as a

whole. Thus, in 1953, when the Department was 2.4% black,

the supervisory ranks were 0.7% black (see, pp. 4-5, supra).

By the end of 1967, when the Department was 4.9% black, the

supervisory ranks were 2.1% black (see pp. 6-7, supra).

These disparities were caused by a policy of deliberate

exclusion. There was a widespread belief in the Department

that black officers would not enforce the law as diligently

against blacks as would white officers.78/ This* belief

resulted in the deliberate exclusion of blacks from the

investigative and specialized units.79/ The upward mobility

of blacks was limited to the detective operations, where they

would not be "leading white police officers in a command

function."80/

78/ Tr. 11/4/77, 26, 61-62 (Executive Deputy Chief Bannon).

Bannon, who is white, was first hired as a police officer in

1949 and at one time subscribed to that belief "[bjecause I

was socialized as every other police officer was." _Id_., 4-5,

62.

79/ Id., 61-62.

80/ Id., 27. Judge Edwards, who was Police Commissioner of

Detroit in 1962-1963, has stated: "The unwritten color lines

in police administration die hard. For example, as of 1962

no Negro police officer in Detroit had ever advanced to the

rank of uniformed lieutenant; there were many units in the

department where not a single Negro officer had ever served."

G.*Edwards, THE POLICE ON THE URBAN FRONTIER 87 (1968).

Judge Edwards promulgated a formal policy against

discrimination in promotions and assignments, see

(continued)

-18-

Following the 1967 race riot, the Department began to

examine and reform its promotional practices. As in the

hiring area, the Department's dual goals were to eliminate

existing discrimination in promotions and to remedy the

effects of past discrimination; and reforms were implemented

haltingly and in stages over a period of years.81/

1. "Dipping" Until 1968, promotions were made at the

discretion of the Commissioner. Rank-order eligibility lists

of candidates who passed the test were developed, with the

written examination score weighted 50 percent, service

ratings weighted 35 percent, seniority weighted 15 percent,

and a veterans' preference of 2 percent.82/ But Police

Commissioners followed a practice of "dipping"— i.e.,

promoting out of order for favoritism purposes, a

80/ (continued) Edwards, Order and Civil Liberties: A

Complex Role for the Police, 64 Mich. L. Rev. 47, 59-60

(1965). But vestiges of the exclusionary practice persisted

until the late 1960's because of resistance in some of the

bureaus and precincts. Tr. 11/4/77, 25-26, 50-51 (Bannon).

81/ However, unlike the hiring area, the Vickery Committee

did not examine the promotional process; and the Department's

corrective actions resulted from internal processes. Tr.

8/24/77, 57 (Caretti).

82/ DX 263 (weights for 1965). These weights varied over

the years. In 1960, the written examination counted 50

percent, service ratings 40 percent and seniority 10 percent.

HEARINGS BEFORE THE UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS,

HEARINGS HELD IN DETROIT, MICHIGAN DECEMBER 14, 15, 1960, p.

394 (statement of Police Commissioner Herbert Hart).

-19-

practice which was not ended until 1968.83/

2. Service Ratings. Until 1973, service ratings were

widely abused.84/ The ratings were dependent upon job

assignments,85/ and police officers in the specialized units

were given improperly high ratings.86/ As noted above (p.

17), there was a historical practice.of racial segregation in

job assignments and of excluding blacks from specialized

units.

Johannes Spreen, who was Police Commissioner between

1968 and 1970, wanted to eliminate service ratings as a

factor in promotions.87/ His successor, John Nichols, also

felt that the service rating system "was not being properly

administered."88/ In November, 1972, Nichols made "drastic

changes" in the service rating system by issuing detailed

guidelines "to insure that the program would be administered

83/ Tr. 8/8/77, 49-50, 110 (former Commissioner Spreen); Tr.

8/9/77, 14-15, 26 (former Commissioner Nichols). The record

does not show the number of people promoted out of order

because of this practice. According to Nichols, who had been

on the Police Department since 1942, the practice was

prevalent enough to be very bad for morale (Tr. 8/9/77, 26).

Caretti,who was assigned to the personnel section in

September, 1968 (Tr. 8/11/77, 6), testified that "dipping"

affected less than 2 percent of promotions (Tr. 8/19/77, 35).

But Spreen, who was Commissioner in 1968, denied that he ever

dipped on promotions (Tr. 8/8/77, 49-50), while acknowledging

that his predecessors had (_id. 110).

84/ Tr. 8/10/77, 59-60 (former Commssioner Nichols).

85/ Id., 63; Tr. 8/9/77, 28 (Nichols), Tr. 8/8/77, 100-101

(former Commissioner Spreen).

86/ Tr. 8/8/77, 100 (Spreen).

87/ Id., 100-102.

88/ Tr. 8/9/77, 28 (Nichols).

-20-

fair ly and equitably across the Department."89/ These

guidelines provided, for the first time, objective standards

for service ratings and warned against the improper influence

of bias.90/ An appeals panel was also established to review

complaints of allegedly improper service ratings.91/ The

appeals panel found that a number of black police officers

were given low service ratings because of racial

discrimination.92/

Following these reforms, the average service ratings of

black and white police officers of comparable seniority were

the same.93/ However, the weight of service ratings in the

promotion model has been halved— from 30 percent in 1970 to

15 percent in 1975.94/ There is nothing in the record to

explain why this reduction occurred after the service rating

system was made job related and nondiscriminatory.95/

89/ Id., 28, 30.

90/ PX 51; PX 43.

91/ Tr. 8/9/77, 38-39 (Nichols).

92/ Tr. 8/24/77, 15 (Commander Caretti, who was Chairman of

the Appeals Board). There was no case of a white police

officer who got a low rating because of racial

discrimination. Ibid.

93/ PX 191; Tr. 8/16/77, 50-57 (Caretti).

94/ DX 263.

95/ Plaintiffs' expert testified, and the district court

found, that the existing (i.e., post-1972) service rating

system is job related and non-discriminatory. Tr. 10/13/77,

17-19 (Dr. Wollack); 446 F. Supp. at 991-992.

-21-

3. Seniority. In 1965, seniority was weighted 15

percent on the promotional model.96/ The Police Department

determined that there is no value in seniority as a deter

minant of promotability and that seniority adversely affected

black police officers because of past hiring practices.97/

For these reasons, the weight of seniority in the promotion

model was reduced to 8 percent in 1970 and 6 percent in

1974.98/

4. Written Promotion Examination. Until 1969, the

written examinations for promotion to sergeant were

essentially IQ tests.99/ These tests were not related to a

sergeant's job performance.100/ This heavy emphasis on IQ

was a "barrier” to the promotional opportunity of black

police officers— "a cultural bias * * * that did effectively

impede the success of minorities in the system.”101/

In September, 1968 Richard Caretti, then a lieutenant,

was assigned to the personnel section to develop promotion

examinations.102/ Caretti had first become involved with the

96/ DX 263.

97/ Tr. 8/24/77, 86-87 (Caretti).

98/ Id., 88-89; DX 263.

99/ Tr. 8/16/77, 67-68; 8/24/77, 61-64, 81 (Caretti).

100/ Tr. 8/24/77, 63; 8/25/77, 75 (Caretti).

101/ Tr. 8/24/77, 81 (Caretti). See also id., 61-62.

Comparative pass/fail statistics by race on these tests were

not presented because such statistics were not recorded until

1973 and could not be developed retrospectively. Id., 71.

102/ Tr. 8/11/77, 6 (Caretti).

-22-

subject of personnel selection a year earlier when he

attended a General Motors institute.103/ Caretti is not a

psychologist, and his efforts in test construction "were the

results of counselling and guidance from psychologists."104/

Based upon the experience he had obtained working with

the Vickery Committee, Caretti realized that the promotion

examinations had to be changed in order that black officers

would have equal opportunity.105/ His goal was to eliminate

all IQ questions and to develop a test that would closely

relate to the content of the sergeant's job.106/ Caretti's

initial efforts were not fruitful. He first worked on the

1969 sergeant promotion test,'but he was allowed to change

only one part of the test (the job-related section) because

"I had just arrived on the scene and possibly the supervisor

had not gained the confidence in my ability to do the

job * * *."107/ In 1970, Caretti prepared a qualifying

examination for promotion from the rank of detective to

103/ Id., 5.

104/ Id., 9.

105/ Tr. 8/24/77, 61 (Caretti). The expert witnesses who

testified for the plaintiffs agreed that promotion tests

which measure IQ are inappropriate, Tr. 10/14/77, 51, 53-54

(Dr. Wollack), and that such tests present a substantial

possibility of racial bias, Tr. 10/12/77, 62-64 (Dr. Ebel).

106/ Id., 62-63; Tr. 8/16/77, 67-68 (Caretti).

107/ Tr. 8/24/77, 64; id., 56 (Caretti).

-23-

sergeant, but the detectives' union exerted sufficient

political power to induce the Police Department to promote

all detectives who took the examination.108/ The result was

that the detectives did not study for the examination but

"just simply went through the motions."109/ No one failed

this examination, and 158 detectives were automatically

promoted, in mass, regardless of qualifications.110/ When

John Nichols became Commissioner in 1970, the promotional

examination was in disrepute. "I had a concern for the

examination per se * * * because a great many people felt

that the entire examination process had been contaminated and

what [sic] direction I gave then [to] Lieutenant Caretti was

that I wanted an examination put together so nobody could say

the fix was on, that they were discriminated against and that

somebody had an advantage that somebody did not have * * *.

What we tried to do was to re-establish the integrity of the

system itself * * *."111/

Caretti attempted to achieve content validity on the

1973, 1974 and 1976 sergeant promotion examinations.112/

108/ Id., 66-67. See also Tr. 8/10/77, 97 (former

Commissioner Nichols).

109/ Tr. 8/24/77, 68 (Caretti).

110/ Id., 69-70; Tr. 8/10/77, 98-102 (Nichols).

111/ Tr. 8/10/77, 80-81 (Nichols).

112/ Tr. 8/16/77, 20, 40 (Caretti).

-24-

He defined content validity as follows:113/

"Certainly the knowledge, skills and

abilities to do the job should be

identified through a job analysis, and

then the content of the examination

should relate to that job analysis.

Essentially that's the way you go

about to obtain content validity is

[sic] in an examina

tion process."

There were two job analyses conducted, by John Furcon in 1973 and

by Andres Inn in 1975.114/ However, Caretti "didn't understand"

Furcon's job analysis "that well"; so for the 1973 and 1974 tests

he "didn't have the benefit of a professional job analysis" and

relied instead on his own experience.115/

Caretti was also restrained in using the job analyses because

of labor negotiations concerning the promotional model.116/ The

examinations are based upon a complex bibliography of reading

materials.117/ Caretti inherited this bibliography when he began

working on promotion examinations in 1969, and it remained

unchanged because of directions by his superiors.118/ Caretti's

discretion in constructing the examinations was limited to

selecting questions from the bibliography.119/ For this purpose,

113/ Id., 19.

114/ Id., 20-21.

115/ Id., 21-22. See also Tr. 8/17/77, 10; 8/18/77, 45-47

(Caretti).

116/ Tr. 3/16/77, 30 (Caretti).

117/ Tr. 8/11/77, 48 (Caretti).

118/ Tr. 8/18/77, 41-42, 47 (Caretti).

119/ Id., 47.

-25-

Caretti retained qualified outside consultants,120/ gave each a

portion of the bibliography, and instructed each to develop a

representative cross-section of multiple-choice questions, which

Caretti then reviewed.121/ Thus, the questions on the examination

tested knowledge of "book content" and, according to Caretti,

"there were sections that dealt with knowledge of the book that

would in many cases surface on the job but many in some other

cases wouldn't surface on the job."122/

As noted above, Caretti's objective was to make the 1973-1976

examinations content valid. However, Caretti refused to express

an opinion as to whether these examinations were in fact content

valid. "I can't say * * * the test is content valid."123/ "Well,

we never found them [the promotion examinations] to be job

related. We worked towards that goal."124/ "I cannot sit here

any say that we have a content valid examination process. I can

say that we worked in that direction and we tried to do the things

that would lead to that goal."125/ "How well we succeeded would be

120/ Id., 42-45, 49-50.

121/ Tr. 8/17/77, 14, 22; 8/24/77, 105-106 (Caretti). One

outside consultant, Dr. Reginald Wilson, described the process

which he followed in developing questions in his assigned area.

He read two textbooks and two study guides from the bibliography.

Then he selected a cross-section of questions that would test,

knowledge of the books and guides. He tried to make the questions

as fair and clear as possible. Tr. 11/17/77, 95-96 (Wilson).

122/ Tr. 8/17/77, 22 (Caretti).

123/ Tr. 8/16/77, 81 (Caretti).

124/ Id., 76.

125/ Id., 82.

-26-

extremely speculative."126/ Indeed, on eight occasions during his

testimony, 'Caretti was asked whether the examinations were content

valid; each time he candidly refused to express that opinion.127/

However, two expert witnesses (Drs. Wollack and Ebel) testified

for the plaintiffs that, in their opinion, the 1973 and 1974 promo

tion tests were content valid.128/ They did not perform a

validation study but relied primarily upon their review of the

tests and of Caretti's testimony on how the tests were

developed.129/ They did not review the 1976 promotion test and

refused to express an opinion as to whether that test was content

valid.130/ The district court found that the 1973, 1974 and 1976

promotion tests were content valid on the basis of "the testimony

of Caretti, Wollack and Ebel."131/

Despite the elimination of IQ questions 132/ and other

126/ Id., 29.

127/ See notes 123-126, supra, and Tr. 8/16/77, 73, 75, 86;

8/17/77, 18.

128/ Tr. 10/12/77, 16, 35, 63-67 (Dr. Ebel); Tr. 10/13/77, 22,

32-34; 10/14/77, 35 (Dr. Wollack).

129/ Tr. 10/12/77, 65-67 (Dr. Ebel); Tr. 10/13/77, 21-22 (Dr.

Wollack).

130/ Tr. 10/14/77, 35-37 (Dr. Wollack); Tr. 10/12/77, 36, 63 (Dr.

Ebel).

131/ 466 F. Supp. at 991.

132/ The 1973 promotion examination contained a 100 question sec

tion, counting for 12.5% of the total score, consisting of the

"Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal," which purports to mea

sure such abstract psychological traits as "inference," "recogni

tion of assumptions," "deduction," "interpretation," and "evalua

tion of arguments"; this section is an IQ test. PX 15. It was

eliminated from the 1974 and 1976 tests. PX 16, 17.

-27-

substantial improvements in the promotion examinations, blacks

failed the 1973, 1974 and 1976 tests at greater rates than

whites.133/ The weight of the written test in the promotional

model was increased from 60 percent in 1973 to 65 percent in 1974

and 1976.134/

5. Oral Boards. The department recognized that many capable

applicants for promotion were not good test takers but neverthe

less had good judgment and communications skills and would perform

excellently as sergeants.135/ To tap these "abilities and know

ledges that were not measured in any other aspect of the pro

motional model," the department instituted oral boards in

1974 136/ which were constructed by two outside experts.137/ The

members of each oral board were police command officers from out

side of Detroit,138/ who were trained in an orientation process so

that their ratings would be reliable and objective.139/ The

133/ The pass rates were 43% for whites and 28% for blacks on the

1973 test; 53% for whites and 39% for blacks on the 1974 test; 51%

for whites and 42% for blacks on the 1976 test. DX 198, 199, 200.

134/ PX 21, 22, 23.

135/ Tr. 8/16/77, 61-62 (Caretti); Tr. 9/6/77, 45; 9/19/77, 26-27

(former Commissioner Tannian); PX 36.

136/ Tr. 8/16/77, 61-62 (Caretti).

137/ Tr. 8/17/77, 54-59 (Caretti); 11/17/77, 97 (Dr. Wilson, one

of these experts).

138/ Id., 98 (this was done to reduce the potential for favori

tism or bias).

139/ Id., 98-99. Each oral board had three members, one of whom

was black. Id., 109; Tr. 8/17/77, 54 (Caretti). Each board mem

ber rated each applicant independently on the basis of a set

rating scale; and the ratings were then averaged. The interviews

were taped, and applicants could appeal to the experts; but there

was a minimal number of appeals. Tr. 11/17/77, 107-110 (Dr. Wilson).

-28-

applicants were tested on a cross-section of typical command

situations, and rated for their knowledge, judgment, logic,

intelligence, quickness of thought, ability to express themselves,

and sensitivity to human relations.140/ The oral boards are job

related and non-discriminatory.141/ On the average, black appli

cants were rated higher than whites on the oral boards.142/

However, the oral board rating was weighted only 10 percent in the

promotional model,143/ although the department believed that this

weight was too low.144/

6. College education and veterans1 preference. To be pro

moted to sergeant from the 1973 eligibility list, a police officer

had to have accumulated at least 15 quarter or 10 semester hours

of college credit; this requirement was raised to 30 quarter or 20

semester hours in 1974, and to 45 quarter or 30 semester hours in

1976.145/ The composite score was increased by one-half point for

each year of college up to two points, and a veterans' preference

of up to two points was also added.146/

140/ Id., 97-110.

141/ Ibid.; 446 F. Supp. at 992.

142/ Tr. 8/17/77, 72 (Caretti); 446 F. Supp. at 992.

143/ PX 22, 23.

144/ Tr. 8/17/77, 58 (Caretti). See also note 154, infra.

145/ PX 21, 22, 23. However, this requirement was waived for all

police officers with 12 1/2 years of seniority as of December 31,

1973. Ibid.

146/ Ibid.

-29-

7. Rank Order. Rank order on the promotion lists is deter

mined by weighting each applicant's scores on the various

components of the promotion model. The rank order scores

adversely affected blacks.147/ In 1973, 19 percent of the

applicants for promotion to sergeant were black;148/ if

rank order had been followed, only 10.6 percent of those

promoted would have been black.149/ In 1974, 27.7 percent

of the applicants were black;150/ rank order promotions

would have been 11.2 percent black.151/ In 1976, 30.9

percent of the applicants were black;152/ rank order pro

motions would have been 26.9 percent black.153/

The reason that rank order adversely affected blacks

is that the component of the promotion model on which

whites scored higher (the written test) was given a

147/ Tr. 8/17/77, 80 (Caretti).

148/ DX 200 (226 of 1191); see Tr. 8/24/77, 82 (Caretti).

The figures reported in this paragraph are for males only.

A number of women were promoted out of order to comply

with the decree in Schaeffer v. Tannian, infra note 168.

We limit these figures to men only because plaintiffs have

never challenged the out of order promotions of women.

150/ DX 199 (318 of 830); see Tr. 8/24/77, 83 (Caretti).

151/ DX 274 (14 of 125).

152/ DX 198 (300 of 971); see Tr. 8/24/77, 83 (Caretti).

153/ DX 274 (18 of 67).

-30-

maximum weight (60-65 percent), while the component on

which blacks scored higher (the oral boards) was given

a minimum weight (10 percent). There is no evidence in

the record which explains how the weights on the promo

tions model were chosen. Caretti inherited the promotion

model in 1969; he did not attempt to justify the weights

on the model but instead explained that his directions

from the City were to make no major changes in the model

because of union negotiations.154/ Nor. did any of the

plaintiffs' experts attempt to justify the component

weights and resulting composite rank-ordered scores.

Dr. Ebel did not even review these matters;155/ Dr. Wollack

had no opinion as to whether the weighted model was job-

related;!^/ and Mr. Guenther, a labor market expert, did

154/ Tr. 8/18/77, 46 (Caretti). Subsequently, in 1975

negotiations, the City proposed to eliminate the seniority

component and to weight the written examination 32 percent,

the oral board 32 percent, service ratings 20 percent,

college credit 14 percent, and veterans' preference 2 per

cent. Tr. 10/20/77, 12-14 (David Watroba, Vice-President

of D.P.O.A.). The union in turn proposed to increase the

seniority component, eliminate the oral board, and elimi

nate the college credit component. Id., 8. The negotia

tions reached an impasse. Id., 9.

155/ Tr. 19/12/77, 54, 71-72 (Dr. Ebel).

156/ "I have made some testimony with regard to the indi

vidual components of the model, but I really have no

opinion as to the method by which the various components

were put together so I really couldn't say whether it's

job related." Tr. 10/14/77, 60-61 (Dr. Wollack).

-31-

not testify on this issue at all.157/ However, plaintiff

D.P.O.A. did retain Dr. Andres Inn to examine the 1974:

promotion model.158/ Dr. Inn's validation study concludes

that the composite scores are based upon arbitrary weights,

that the department's scoring procedure was inappropriate,

that rank order did not measure relative qualifications

and that M[t]he rank order scores convey a false illusion

of overall superiority or inferiority."159/

Nevertheless, the district court stated that there

is "no written validation report regarding the 1973-1976

examination models. However, equally important to note

is the fact that Caretti, Wollack, Guenther and Ebel con

sistently testified that the promotional models for 1973-

1976, including each component part, were job related and

content valid"160/ Based upon this "testimony," the

district court found that rank order scores measured rela

tive qualifications for promotion.161/

157/ See Tr. 9/27/77; 9/28/77; 9/29/77 (Guenther).

158/ Tr. 10/20/77, 44 (Watroba).

159/ PX 298 (a).

160/ 446 F. Supp. at 993-994.

161/ Id., at 994.

-32-

8. Summary and results, 1968-1974. Between 1968 and

June, 1974, the.Police Department took substantial steps

which were designed to reduce or eliminate continuing

discrimination in the promotion process. The practice of

"dipping" was ended, the service ratings were made job-

related and non-discriminatory, the written test was re

formed, the weight of seniority was reduced, and the oral

boards were added. However, the department had taken no

race-conscious steps to remedy the effects of past discri

mination. Commissioners Spreen (1968-1970) and Nichols

(1970-1973) opposed promoting out of order from the eligi

bility lists, although they recognized the necessity of

having more blacks in the supervisory ranks.162/ There

was much less progress in integrating the supervisory ranks

than the entry-level police officer rank. By June of 1974,

the department as a whole was 17.2 percent black, but only

5.1 percent of the sergeants (61 of 1185) were black.163/

And the promotional model continued to have an adverse impact

against minorities. On May 9, 1974, thirty police officers

162/ Tr. 8/8/77, 76, 87-91, 111-113 (Spreen); Tr. 8/9/77,

18-22; 8/11/77, 48-50 (Nichols). Commissioner Spreen

expressed the dilemma thusly: "I think it's a hell of a

mess to try to rectify what ought to be done." Tr. 8/8/77,

96.

163/ DX 208, p. 3. The lieutenants' rank was 4.7 percent

black (11 of 230). Ibid.

-33-

were promoted to sergeant according to rank order from the

top of the eligibility list; 29 of those promoted were

white.164/ The department then determined that affirma

tive race-conscious steps were necessary to remedy the

exclusion of blacks at the supervisory ranks caused by

past discrimination.

D. The Affirmative Action Promotions, 1974-1977

On July 22, 1974, the Chief of Police, Phillip

Tannian, requested permission from the Board of Police

Commissioners to make promotions on an affirmative action

basis.165/ The Board was created by the Detroit City

Charter of July 1, 1974; and its five members had sole

authority to authorize promotions out of rank order from

the eligibility lists.166/ Tannian believed that he had

a legal and moral duty to take affirmative action to rec

tify the effects of past discrimination.167/ He believed

164/ 446 F. Supp. at 987.

165/ PX 240 (minutes of 7/22/74 meeting).

166/ PX 276, Section 7-1114 (City Charter).

167/ Tr. 8/26/77, 81; 8/30/77, 6; 9/12/77, 11-13 (Tannian).

The Corporation Counsel's Office advised the department

and the Board of Police Commissioners "that we had a duty

to move." Tr. 9/16/77, 20, 23, 33; 9/19/77, 28 (Tannian);

DX 44.

-34-

that the department could voluntarily take corrective action

without having to be sued and ordered to act by a court:168/

"[If] the [judicial branch] upon * * *

appropriate finding[s] * * * can order

certain actions, and those actions are

entirely proper and lawful, then it should

not be a requirement upon the executive

branch of government, where they analyze

the facts and find things to be dispro

portionate and not in compliance, [to]

stand around and wait for somebody to sue

them to have a court order to deal with."

Chief Tannian also was aware of the extreme hostility between

the black community and the depart

ment resulting from the department's exclusionary practices.169/

He believed that the law enforcement capabilities of the

department had been impaired by the exclusionary effects of

past discrimination, and that "a department which more accurately

reflects the pluralistic characteristics of our City will

be best equipped to carry out the primary responsibility of

168/ Tr. 9/16/77, 18 (Tannian). The department had in

fact been sued for sex discrimination. The district court

found that the department had historically discriminated

against women in hiring and promotion. Schaeffer v. Tannian,

394 F. Supp. 1128 (E.D. Mich. 1974). The court ordered the

department to hire one woman for each man, ibid., and to

promote 19 women preferentially to sergeant from the existing

eligibility list and to thereafter promote without regard

to sex. 10 FEP Cases 896 (E.D. Mich., order of June 7, 1974).

169/ Tr. 9/7/77, 86 (Tannian).

35