Memorandum Supporting Motion for Order Governing Expert Witnesses and Opposing Defendants' Proposed Order

Public Court Documents

April 1, 1992

8 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Memorandum Supporting Motion for Order Governing Expert Witnesses and Opposing Defendants' Proposed Order, 1992. 1c3529f0-a146-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b1d25817-459c-41fa-a539-fddb2675413f/memorandum-supporting-motion-for-order-governing-expert-witnesses-and-opposing-defendants-proposed-order. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

v p

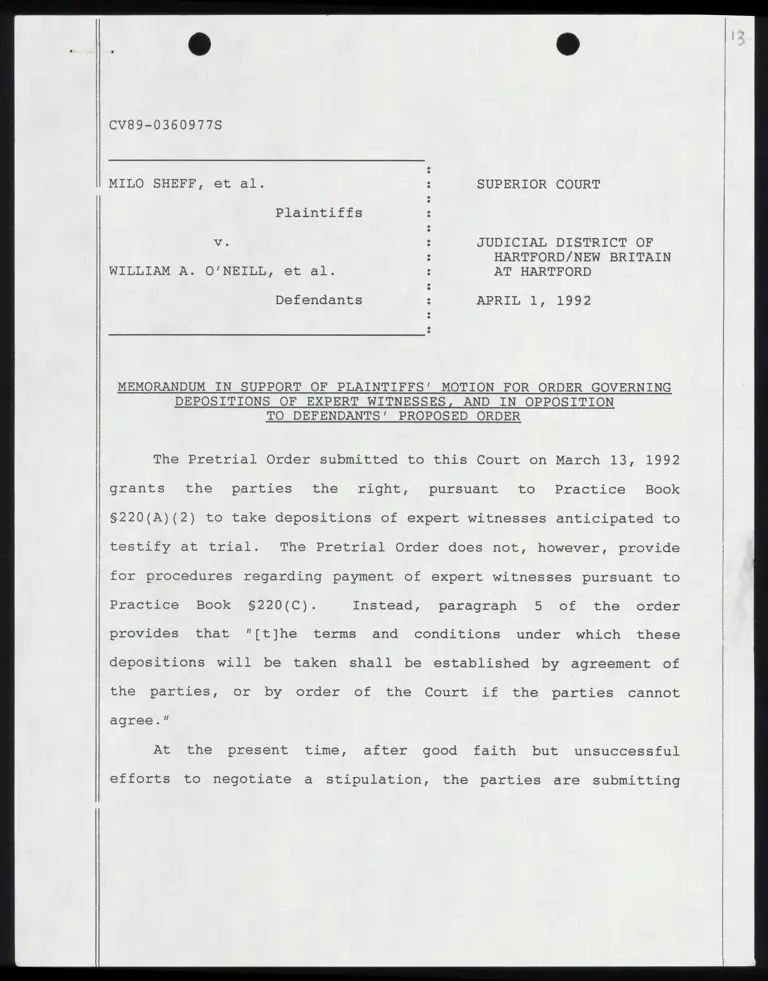

Cv89-0360977S

MILO SHEFF, et al. SUPERIOR COURT

Plaintiffs

Vv. JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF

HARTFORD/NEW BRITAIN

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, et al. AT HARTFORD

Defendants APRIL 1, 1992

[L

J

o

e

e

e

e

e

LL

J

LL

]

o

e

L

L

LL

]

[1

]

o

e

e

e

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR ORDER GOVERNING

DEPOSITIONS OF EXPERT WITNESSES, AND IN OPPOSITION

TO DEFENDANTS’ PROPOSED ORDER

The Pretrial Order submitted to this Court on March 13, 1992

grants the parties the right, pursuant to Practice Book

§220(A) (2) to take depositions of expert witnesses anticipated to

testify at trial. The Pretrial Order does not, however, provide

for procedures regarding payment of expert witnesses pursuant to

Practice Book §220(C). Instead, paragraph 5 of the order

provides that “[tlhe terms and conditions under which these

depositions will be taken shall be established by agreement of

the parties, or by order of the Court if the parties cannot

agree.”

At the present time, after good faith but unsuccessful

efforts to negotiate a stipulation, the parties are submitting

competing proposed orders governing payment of expert

depositions. The remaining areas of dispute include the

following points:

a. Defendants’ proposed order, submitted on March 19, 1992,

does not provide for contemporaneous payment of expert

witnesses on or close to the time of their depositions.

b. Defendants’ proposed order does not provide adequate

deposition preparation time for experts.

c. Defendants’ proposed order does not provide adequate

compensation for experts at their regular hourly rates.

The parties are in agreement on the principles that outside

expert witnesses must be paid for their deposition time, and that

Department of Education employees identified as experts are not

entitled to be paid. The parties have also reached agreement on

the procedure for location of depositions, and the procedure for

payment of expenses, if any. These areas of agreement are

reflected in paragraphs 1, 2, and 6 of plaintiffs’ and

defendants’ proposed orders. Plaintiffs will now address the

areas in dispute.

Practice Book §220(C) requires that “the court shall require

that the party seeking discovery pay the expert a reasonable fee

for time spent in responding to discovery” and that in addition,

the Court may require payment of “a fair portion of the fees and

expenses reasonably incurred...in obtaining facts and opinions

from the expert.” Plaintiffs have found little Connecticut

caselaw construing this provision. See, e.q., Falvey’'s Inc. v.

Republic Oil, Co., 3. CSCR 931, 933 (Superior Court .1988)

("reasonable fee” for expert deposition). However, the

Connecticut rule is based on identical language in Rule 26(b) (4),

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, and in construing the discovery

provisions of the Connecticut Practice book, Connecticut courts

generally look to federal caselaw interpreting similar provisions

under the Federal Rules. See Gotler wv. Aetna Life & Casualty

GO., 4 Conn. L. Rptr. 518, 519 (Superior Court, 1991). (“Rule 36

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure is helpful since our rule

Of practice is borrowed from it.”); Falvev’s, Inc. vv. Republic

Qil Co., supra. See, generally, Moller and Horton, Connecticut

Practice Annotated at 393-4, 397, 398 (1989), and cases cited

therein.

For the reasons set out below, under standards established

by federal caselaw, defendants’ proposed order does not provide

adequate compensation for plaintiffs’ experts, and should not be

adopted.

1. Plaintiffs are entitled to contemporaneous payment for

expert depositions

Defendants’ proposed order would pay plaintiffs’ experts

for their time long after their depositions have taken place, up

to three months after the conclusion of trial. Although

plaintiffs understand defendants’ desire to delay payment, there

is no legal basis for defendants’ position, and plaintiffs’

experts should be paid at or near the time of the deposition. In

fact, some cases have even required payment of expert deposition

fees and expenses prior to taking of the expert deposition. In

an analogous situation, in In re "Agent Orange” Product Liability

Lirigation, 105 PF.R.D. 577, 582 (EF.D.N.Y. 1983), the court

required payment of fees in advance, at the expert’s normal rate,

for attendance at the expert's deposition. Likewise, the court

in Wright v. Jeep Corp., 547 ¥.Supp. 871, 877 (E.D. Mich. 1982),

held that defendant was not entitled to the benefit of a vehicle

crash expert's research without advancing a reasonable fee.

2. Plaintiffs’ experts are entitled to payment for a

reasonable amount of preparation in advance of their

deposition.

Defendants’ proposed order provides compensation for

only 2 hours of preparation for each deposition. There is no

dispute between the parties regarding the obligation to pay for

deposition preparation time, see, e.g., American Steel Products

Corp. v. Penn Cent. COorp., 110 FP.R.D, 151, 153 (S.D.N.Y. 1986);

Carter-Walilasce, Inc. v. Hartz Mountain Industries, Inc., 553

P.Supp. 45,. 53 (S.D.N.¥. 1982); United States vv. Citv of Twin

Falls, Idaho, 806 F.2d 862, 873-879 (9th Cir. 1986). However,

defendants’ proposed 2-hour limit is unsupported by the caselaw,

which clearly requires payment of a “reasonable” fee. See Hurst

v. United States, 123 F.R.D. 319, 321 (D. S.D. 1988); Carter-

Wallace, Inc. v. Hartz Mountain Industries, supra. In a case

such as this, two hours is clearly not sufficient time to

adequately prepare for a complex deposition lasting a minimum of

3-8 hours.

3. Plaintiffs!’ experts are entitled to be compensated at

their reqular hourly rate

The most problematic aspect of defendants’ proposed

order is their attempt, in paragraph 3, to avoid payment of

plaintiffs’ experts at their regular hourly rate. Defendants’

proposal would limit payment to the hourly rate actually being

paid by the party engaging the expert, rather than the expert's

regular hourly or daily rate. This is inconsistent with Practice

Book §220 and with caselaw construing the identical language of

Federal Rule 26(b) (4).

There 1s no dispute that experts are entitled to

"reasonable fees” as set out in Practice Book §220. See, €.9.,

In re “Agent Orange” Product Liability Litigation, supra; Hurst,

supra. See also 8 Wright and Miller, Federal Practice and

Procedure, §2034. The only dispute in this case is as to what

fee is “reasonable.” In Goldwater v. Postmaster General of the

United Secates, 136 PFP.R.D. 337, 339-49 (D. Conn. 1991), the

federal court considered several factors. It looked at the area

of the witness's expertise, the education and training required

to provide the expert insight, the prevailing rates of other

comparably respected available experts, the nature, quality, and

complexity of discovery responses provided and the cost of living

in the particular geographic area. (In Goldwater, the expert's

fee was ultimate reduced from $450 per hour to $200 per hour.)

In the Proposed Order, plaintiffs propose that each

party submit the anticipated hourly rates for various experts in

advance, and if any party objects to a particular rate, the

proposed order sets out a procedure for such objection.

Furthermore, because most of the experts identified in Sheff are

in similar fields, plaintiffs do not anticipate wide variations

in hourly rates.

The purpose of the rule requiring payment for expert

depositions is “to avoid the unfairness of requiring one party to

provide expensive discovery for another party’s benefit without

reimbursement.” United States v. Citv of Twin Falls, Idaho, 806

F.2d 862, 879 (9th Cir. 1986), citing Moore's Federal Practice

126.66[5](2d ed. 1984). In the present case, it is possible that

plaintiffs might be paying varying rates to different experts.

It is also possible that, in some instances, the rate of payment

is determined on some basis other than hourly rate, or that

certain plaintiffs’ experts may be working at a rate less than

their regular hourly rate. In these circumstances, defendants’

proposal would make the calculation of hourly rates difficult, if

not impossible. As submitted, defendants’ proposal could also

force plaintiffs to bear the cost of defendants’ expert

discovery, in contravention of Practice Book §220. See 4 Moore's

Federal Practice §26.66({5]) fn. 5. ("There is no justification for

providing the discovering party with the information at the

opposing party's expense.”) For these reasons, it would be

improper to base the determination of an expert’s hourly rate for

a deposition on the amount received for other research and

testimony in the case.

Conclusion

For all of the foregoing reasons, plaintiffs’ proposed Order

Governing Depositions of Expert Witnesses should be entered by

the Court.

Respectfully Submitted,

ON THE BRIEF: y 24 TZ

Barbara O'Connell, Philip D. Tegeler

Law Student Intern Martha Stone

Connecticut Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

32 Grand Street

Hartford, CT 06106

Wesley W. Horton Ronald L. Ellis

Kimberly A. Knox Julius L. Chambers

Moller, Horton; & Rice Marianne Engelman Lado

90 Gillett Street NAACP Legal Defense &

Hartford, C7 06105 Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

John Brittain Wilfred Rodriguez

University of Connecticut Hispanic Advocacy Project

School of Law Neighborhood Legal Services

65 Elizabeth Street 1229 Albany Avenue

Hartford, C7 06105 Hartford, CT 06112

ERE

Helen Hershkoff Ruben Franco

John A. Powell Jenny Rivera

Adam S. Cohen Puerto Rican Legal Defense

American Civil Liberties and Education Fund

Union Foundation 99 Hudson Street

132 West 43rd Street New York, NY 10013

New York, NY 10036

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that one copy of the foregoing has been

mailed postage prepaid to John R. Whelan, Assistant Attorney

General, MacKenzie Hall, 110 Sherman Street, Hartford, CT 06105

5?

this / day of April, 1992

V/A aN

Philip D. Tegeler