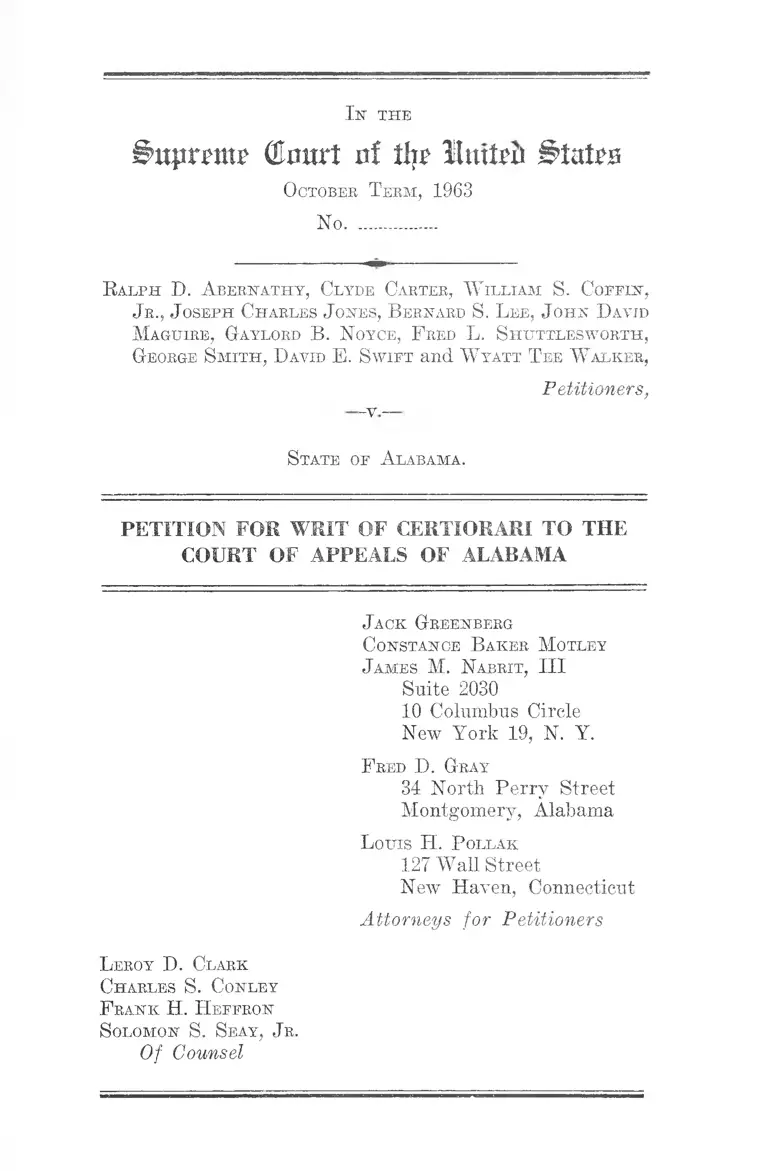

Abernathy v. Alabama Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals of Alabama

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Abernathy v. Alabama Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals of Alabama, 1963. 26e31aba-ab9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b1dd4af4-6e3c-48d7-aac8-dc232d7bf1ec/abernathy-v-alabama-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-court-of-appeals-of-alabama. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

Bvipvmt (Hmtrt of % Imfrii Btutm

October Term, 1963

No................

Ralph D. Abernathy, Clyde Carter, W illiam S. Coffin,

J r., J oseph Charles J ones, Bernard S. L ee, J ohn David

Maguire, Gaylord B. Noyce, F red L. Shuttlesworth,

George Smith , David E. Swift and W yatt T ee W alker,

-v -

Petitioners,

State of Alabama.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

COURT OF APPEALS OF ALABAMA

J ack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

F red D. Gray

34 North Perry Street

Montgomery, Alabama

L ouis H. P ollak

127 Wall Street

New Haven, Connecticut

Attorneys for Petitioners

Leroy D. Clark

Charles S. Conley

F rank H. H effron

Solomon S. Seay', J r.

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below........................................... 2

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 2

Questions Presented .................................... 3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved........ 5

Statement ........................................................................ 6

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

Below ........................... —-.............. -..................... ....... 15

Reasons for Granting the W rit........................ -........... 19

I. The Decision Below Affirms Criminal Convic

tions Based on No Evidence of Guilt................ - 19

II. The State Statutes, as Construed and Applied

to Convict Petitioners Are So Vague, Indefinite

and Uncertain as to Offend the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment ................ 25

III. The Arrests and Convictions of Petitioners on

Charges of Breach of the Peace and Unlawful

Assembly Constitute Enforcement by the State

of the Practice of Racial Segregation in Bus

Terminal Facilities Serving Interstate Com

merce, in Violation of the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Com

merce Clause of the Constitution, and 49 U. S. C.

§316 (d) ....... -....................................................... 29

11

PAGE

IV. The Decision Below Conflicts With Decisions of

This Court Securing the Fourteenth Amendment

Right to Freedom of Expression, Assembly and

Religion........... .............................................-....... 31

V. The Courts Below Deprived Petitioners of Due

Process and Violated the Supremacy Clause by

Refusing to Accept the Federal District Court

Finding That Petitioners Were Arrested to En

force Racial Segregation ................................... 34

Conclusion...................................................................... 36

Appendix :

Opinion of Court of Appeals in the Abernathy Case la

Order of Affirmance of the Court of Appeals in the

Abernathy Case.................................................... 14a

Order of Affirmance of the Court of Appeals in the

Carter Case ......................................................... 15a

Order of the Court of Appeals Denying Rehearing 16a

Order of the Supreme Court of Alabama Denying

Certiorari............................................................. 17a

T able of Cases

Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F. 2d 33 (8th Cir. 1958) ............... 21

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 41 ...............................— 30

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961) ...... 30

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531 (5th

Cir. 1960) .................................................................... 30

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454 .....................19, 29, 34

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60.................................. 21

Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495 .................................. 31

I l l

PAGE

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 ..............22, 26, 27, 32

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 IT. 8. 568 .......... ..... 33

Connally v. General Constr. Co., 269 U. S. 385 ............. 27

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 .............. ...........................21, 26

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 IT. S. 229 ..............22, 26, 32

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315................................. 33

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 IT. S. 157 ........ 20, 21, 23, 26, 31, 32

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 902, affirming, 142 F. Supp.

707 (M. D. Ala. 1956) ...................... ..........................19,30

Gitlow v. New York, 26S U, S. 652 ................................. 33

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 ................................... 27

Hoag v. New Jersey, 356 IT. S. 464 ............... ............ 35

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 IT. S. 451 ............ .............. 27

Lewis v. Greyhound Corp., 199 F. Supp. 210 (M. D. Ala.

1961) .................................................. ............. 6,16,29,34

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S. 191....... .................... ..... 31

Mitchell v. State, 130 So. 2d 198 (Ala. App. 1961) ........ 22

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 ................................19, 30

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 .................. .......... 31

Nesmith v. Alford, 318 F. 2d 110 (5th Cir. 1963) ..... . 21

Raley v. Ohio, 360 IT. S. 423 ........................................... 27

Rochin v. California, 342 IT. S. 165 ............................ 24

Sealfon v. United States, 332 U. S. 575 ........ ......... 34

Scull v. Virginia, 359 U. S. 344 .... .............................. 27

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ________ _________ 30

Sherman v. United States, 356 U. S. 369 __ ________ 24

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ___ ____ 28, 31, 33

IV

PAGE

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154 ........................ 20, 21, 23

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 . 31

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 ............. 28

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 ................. 20, 22, 23

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 ............................ 31

Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 ................. 30

United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 U. S. 81 .... 27

United States v. Oppenheimer, 242 U. S. 85 ................ 34

Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178 ..................... 27

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 .................. 21

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357 ........................ 33

Williams v. North Carolina, 317 U. S. 387 ________ 28

Wolfe v. North Carolina, 364 U. S. 177...... ................ 35

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 ________ ______ 22, 26

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 ............................ 30

Yates v. United States, 354 U. S. 298 ........ ................ 35

Statutes

28 United States Code §2283 ........................................... 7

49 United States Code §316 __________ ___..5,15,19, 30

49 Code of Federal Regulations §180(a) (1)-(10) ...... 19

Alabama Code, tit. 14, §119(1) (Supp. 1961) .......... 5,8,22

Alabama Code, tit. 14, §407 (1958) ..................... 5, 8, 23, 27

Alabama Code, tit. 15, §363 (1958) ............................ 8

Other Authorities

8 Am. Jur., Breach of the Peace, §3, p. 834 .............. 26

Restatement of Judgments, §68(1) .......................... ..... 34

I n t h e

^ujtrmp Qlourt of % Inttefr Btutiz

October Term, 1963

No................

Ralph D. Abernathy, Clyde Carter, W illiam S. Coffin,

J r., J oseph Charles J ones, Bernard S. L ee, J ohn David

Maguire, Gaylord B. N oyce, F red L. S huttlesworth,

George Sm ith , David E. Swift and W yatt T ee W alker,

Petitioners,

-v-

State of Alabama.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

COURT OF APPEALS OF ALABAMA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Court of Appeals of Alabama in the

cases of Ralph D. Abernathy v. State of Alabama; Clyde

Carter v. State of Alabama; William S. Coffin, Jr. v. State

of Alabama; Joseph Charles Jones v. State of Alabama;

Bernard S. Lee v. State of Alabama; John David Maguire

v. State of Alabama; Gaylord B. Noyce v. State of Alabama;

Fred L. Shuttlesworth v. State of Alabama; George Smith

v. State of Alabama; David E. Swift v. State of Alabama

and Wyatt Tee Walker v. State of Alabama, entered on

October 23, 1962. The Supreme Court of Alabama denied

certiorari on July 25, 1963.

2

Citations to Opinions B elow

The opinion of the Court of Appeals of Alabama in Aber

nathy v. Alabama (ft. A. 476)1 is reported at 155 So. 2d

586 and is set forth in the appendix attached hereto, infra,

p. la. The Court of Appeals rendered no opinion in the

other cases but affirmed the convictions on the authority of

the Abernathy case (It. Ca. 34; ft. Co. 36; B. J. 35; ft. L.

34; R. M. 35; B. N. 35; R. Sh. 34; B. Sm. 34; B. Sw. 35;

R. W. 34).

Jurisd iction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals of Alabama in

each of these cases was entered on October 23, 1962 (R. A.

475; R. Ca. 34; R. Co. 36; R. J. 35; R. L. 34; B. M. 35; B. N.

35; R. Sh. 34; R. Sm. 34; B. Sw. 35; R. W. 34). Rehearing

was denied on November 20, 1962 (R. A. 489; R. Ca. 35;

R. Co. 37; B. J. 36; B. L. 35; R. M. 36; R, N. 36; R, Sh. 35;

R. Sm. 35; R. Sw. 36; B. W. 35). The Supreme Court of

Alabama denied certiorari on July 25, 1963 (B. A. 496).2

The jurisdiction of this Court in each of these cases is

invoked pursuant to Title 28, United States Code, Section

1257(3), petitioners having asserted below and asserting

here, deprivation of rights, privileges and immunities

secured by the Constitution of the United States.

1 The record in the Abernathy case is cited herein as “R. A.”

followed by the page number. The Abernathy record contains

the trial transcript for each case. The other records are cited as

follows: (1) Carter—“R. Ca.” ; (2) Coffin—“R. Co.” ; (3) Jones—

“R. J .” ; (4) Lee—“R. L.” ; (5) Maguire—“R. M.” ; (6) Noyce—

“R. N.” ; (7) Shuttlesworth—“R. Sh.” ; (8) Smith—“R. Sm.” ;

(9) Swift—“R. Sw.” ; and (10) Walker—“R. W.”

2 In all cases except Abernathy, the order of the Supreme

Court of Alabama denying certiorari was not included in the cer

tified records as bound. However, the order in the Abernathy

record, p. 496, contains the captions of all eleven eases, and in

3

Questions Presented

In May of 1961, when Montgomery, Alabama, was under

the control of the Alabama National Guard, petitioners,

seven Negroes and four whites, were escorted by Guards

men to an interstate bus terminal, from which seven of

petitioners were planning to take a bus to Mississippi.

While awaiting the departure of the bus, petitioners, in

the presence of their Guard escort—an escort which in

cluded the senior guard officers controlling the city—crossed

the terminal waiting room and sat down at the terminal

lunch counter to get a snack. The Guard officers did not

tell any of petitioners not to sit down at the counter; nor

did they tell any of petitioners not to do so prior to escort

ing petitioners to the terminal. After petitioners were

seated at the lunch counter, the Sheriff of Montgomery

County, acting on a signal from a ranking Guard officer,

arrested petitioners for breach of the peace and unlawful

assembly.

Petitioners promptly sought a federal court injunction

to restrain the county solicitor from prosecuting them on

these charges. After taking extensive testimony, District

Judge Johnson denied the injunction on the ground that

28 U. S. C. §2283 prevented him from restraining a pend

ing state criminal prosecution; but in announcing his deci

sion, Judge Johnson said that the arrest of petitioners was

designed to perpetuate racial segregation.

At petitioners’ ensuing state court trial, ranking Guard

officers testified that, in view of the presence across the

each of the other bound records appears an unnumbered page with

the notation that the writ of certiorari was denied without opinion

(R. Ca. 35-36; R. Co. 37-38; R. J. 36-37; R. L. 35-36; R, M.

36-37; R. N. 36-37; R. Sh. 35-36; R. Sm. 35-36; R. Sw. 36-37;

R. W. 35-36). Submitted with the bound records in these ten cases

are certified copies of the Supreme Court of Alabama’s order deny

ing certiorari.

4

street from the terminal of a large, hostile white crowd,

petitioners’ action in seating themselves at the lunch coun

ter had been likely to provoke violence by the crowd.

Did the arrest and subsequent conviction of petitioners

deprive them of rights protected by:

1. the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

in that they were convicted on a record barren of any evi

dence of guilt;

2. the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

in that they were convicted under penal provisions which

were so indefinite and vague as to afford no ascertainable

standard of criminality;

3. the due process and equal protection clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

in that they were arrested and convicted to enforce racial

discrimination;

4. the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,

as that clause incorporates the First Amendment’s protec

tion of freedom of expression, assembly and religion;

5. Title 49, United States Code, Section 316(d), which

prohibits discrimination in terminal facilities of bus com

panies operating in interstate commerce;

6. the commerce clause of the Constitution, in that the

prosecution of petitioners constituted an unlawful burden

on commerce;

7. the due process clause of the Constitution in that

petitioners were, in effect, entrapped, in the sense that their

military guardians permitted them to sit down at a lunch

counter where they had federal and constitutional rights

to be served and then, without requesting petitioners to

withdraw from the lunch counter, arrested them for this

permitted exercise of their federal rights;

5

8. the supremacy clause of the Constitution in that the

courts of Alabama tried and convicted petitioners pursuant

to their arrest on charges which, a federal district court

had already determined, were intended to perpetuate racial

segregation?

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved

Each of these cases involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth

Amendment, Article I, Section 8 (commerce clause), and

Article VI (supremacy clause) of the Constitution of the

United States.

Each petitioner was convicted under Code of Alabama,

Title 14, Section 407 (1958):

If two or more persons meet together to commit a

breach of the peace, or to do any other unlawful act,

each of them shall, on conviction, be punished, at the

discretion of the jury, by fine or imprisonment in the

county jail, or hard labor for the county, for not more

than six months.

Every petitioner except Walker was also convicted under

Code of Alabama, Title 14, Section 119 (1) (Supp. 1961):

Any person who disturbs the peace of others by vio

lent, profane, indecent, offensive or boisterous con

duct or language or by conduct calculated to provoke

a breach of the peace, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor,

and upon conviction shall be fined not more than five

hundred dollars ($500.00) or be sentenced to hard

labor for the county for not more than twelve (12)

months, or both, in the discretion of the Court.

Each case also involves Title 49, United States Code,

Section 316 (d) :

6

. . . It shall be unlawful for any common carrier by

motor vehicle engaged in interstate or foreign com

merce to make, give, or cause any undue or unreason

able preference or advantage to any particular person,

port, gateway, locality, region, district, territory, or

description of traffic, in any respect whatsoever; or

to subject any particular person, port, gateway, local

ity, region, district, territory, or description of traffic

to any unjust discrimination or any undue or unrea

sonable prejudice or disadvantage in any respect what

soever :

Statem ent

Petitioners, seven Negro and four white men, were

arrested in the Trailways Bus Depot in Montgomery,

Alabama, on May 25, 1961, while participating in a “Free

dom Bide” to test racial restrictions on the use of bus

terminal facilities serving interstate commerce (R. A.

172-80). The arrests occurred shortly after some of

the petitioners sat together at the terminal’s segregated

lunch counter (R. A. 132, 180).

On the same day, May 25, 1961, a suit was filed in the

United States District Court for the Middle District of

Alabama seeking to enjoin the arrest of persons using inter

state transportation facilities in Montgomery on a deseg

regated basis. Petitioner Abernathy was an original plain

tiff in that action. The Attorney General of Alabama and

the Circuit Solicitor for the Fifteenth Judicial Circuit

(encompassing Montgomery) were defendants. Immedi

ately after their arrests, the other ten petitioners filed a

motion to intervene in the federal court action, which was

granted on May 26, 1961. Lewis v. Greyhound Corp., 199

F. Supp. 210, 213. A hearing was held in the district court

on September 5, 1961. After hearing the plaintiffs’ evi-

7

dence, including the testimony of the ranking officers who

arrested these eleven petitioners, Judge Johnson dismissed

the action as to the arrests of these petitioners on the

ground that 28 U. S. C. §2283 “precludes the granting of

such relief.” Judge Johnson did, however, state:

the court does not find or believe that the arrest [of

the eleven petitioners] against whom these criminal

proceedings are now pending was for any purpose other

than to enforce segregation. As a matter of fact, in

this posture of the case, the court is of the opinion

that the arrest of those individuals was for the purpose

of enforcing segregation in these facilities” (E. A. 9,

12-13; E. Ca. 8, 11; E. Co. 9, 12-13; R. J. 9, 12-13; E. L.

9, 12-13; E. M. 9, 12-13; R. N. 9, 12-13; E. Sh. 8, 11;

E. Sm. 8, 11; R. Sw. 9, 12-13; E. W. 8, 12).

The eleven petitioners were tried together on September

15, 1961, in the Court of Common Pleas of Montgomery

County on charges that each petitioner:

did disturb the peace of others by violent, profane, in

decent, offensive or boisterous conduct or language or

conduct calculated to provoke a breach of the peace in

that he did come to Montgomery, Alabama which was

subject to martial rule and did unlawfully and inten

tionally attempt to test segregation laws and custom

by seeking service at a public lunch counter with a

racially mixed group, during a period when it was

necessary for his own safety for him to be protected

by military and police personnel and when the said

lunch counter building was surrounded by a large num

ber of hostile citizens of Montgomery.

and

did meet with two or more persons to commit a breach

of the peace or to do an unlawful act, against the peace

and dignity of the State of Alabama (R. each case 1).

8

All eleven defendants were convicted of both breach of

the peace (Ala, Code, tit. 14, §119(1) (Supp. 1961)) and

unlawful assembly (Ala. Code, tit. 14, §407 (1958)). Walker

was sentenced to 90 days in jail, and the others were sen

tenced to 15 days in jail with fines of $100 and costs (R.

each case 2).

On appeal to the Circuit Court of Montgomery County,

petitioners were tried again.3 The eleven cases were con

solidated for trial, but a separate judgment was entered in

each case (R. A. 21; R. Ca. 20; R. Co. 21; R. J. 21; R. L. 20;

R. M. 21; R. N. 21; R. Sh. 20; R. Sm. 20; R. Sw. 21; R. W.

20). Each petitioner was convicted, fined one hundred dol

lars and sentenced to thirty days at hard labor (R, A. 38;

R. Ca. 21; R. Co. 22; R. J. 22; R. L. 21; R. M. 22; R. N. 22;

R. Sh. 21; R. Sm. 21; R. Sw. 22; R. W. 21),4 an increase in

jail sentence for each petitioner except Walker.

Appeal was taken to the Court of Appeals of Alabama.

Only the Abernathy record contained the transcript of

trial in the Circuit Court, but pursuant to stipulation (R.

A. 47; R. Ca. 30; R. Co. 32; R. J. 31; R. L. 30; R, M. 31;

R. N. 31; R. Sh. 30; R. Sm. 30; R, Sw. 31; R. W. 30) the

Court of Appeals considered the transcript a part of the

record in each of the other cases (R. A. 476-77). The

3 In the Circuit Court, where proceedings are begun by a Solic

itor’s complaint (Ala. Code, tit. 15, §363 (1958)), petitioner

Walker was charged only with unlawful assembly (Ala. Code, tit.

14, §407 (1958)) (R. W. 3-4) and arraigned on that charge alone

(R. A. 68). At the trial the Circuit Judge acknowledged that only

one charge was pending against Walker (R. A. 74; see also R. A.

227, 228).

4 Default in payment of the fine will result in an additional

thirty days in jail (R. A. 38; R. Ca. 21; R. Co. 22; R, J. 22;

R. L. 21; R. M. 22; R. N. 22; R, Sh. 21; R, Sm. 21; R, Sw. 22;

R, W. 21). Default in payment of court costs, wfhich also were

assessed, will result in an additional 133 days for petitioner Aber

nathy (R. A. 38-39), 80 days for the others (R. Ca. 21-22;

R. Co. 22-23; R. J. 22-23; R. L. 21-22; R. M. 22-23; R. N. 22-23;

R. Sh. 21-22; R. Sm. 21-22; R. Sw. 22-23; R. W. 21-22).

9

Court of Appeals affirmed each judgment of conviction,

and rehearing was denied. The Supreme Court of Alabama

denied certiorari.

In the Circuit Court the Solicitor’s Complaint, which con

stitutes the formal charge, alleged that each petitioner

(except Walker):

did disturb the peace of others in Montgomery, Ala

bama, at a time when said city and county were under

martial rule as a result of the outbreak of racial mob

action, by conduct calculated to provoke a breach of

the peace, in that he did wilfully and intentionally seek

or attempt to seek service at a public lunch counter

with a racially mixed group, at which time and place

the building housing said lunch counter was surrounded

by a large number of hostile citizens of Montgomery,

Alabama, and it was necessary for his own safety for

him to be protected by military and civil personnel

(R. A. 3-4; R. Ca. 3; R. Co. 3; R. J. 3; R. L. 3; R.

M. 3; R. N. 3; R. Sh. 3; R. Sm. 3; R, Sw. 3)

and that each petitioner:

did meet with two or more persons to commit a breach

of the peace or to do an unlawful act, in that he did

meet with two or more persons in Montgomery, Ala

bama, at a time when said city and county were under

martial rule as a result of the outbreak of racial mob

action, for the purpose of wilfully and intentionally

seeking or attempting to seek service at a public lunch

counter with a racially mixed group at which time and

place the building housing said lunch counter was sur

rounded by a large number of hostile citizens of Mont

gomery, Alabama, and it was necessary for his own

safety for him to be protected by military and police

personnel, against the peace and dignity of the State

10

of Alabama (R. A. 4; R. Ca. 3; R. Co. 3; R. J. 3;

R. L. 3; R. M. 3; R. N. 3; R. Sh. 3; R. Sm. 3; R, Sw.

3; R. W. 3-4).

The petitioners are four ministers (Coffin, Abernathy,

Walker and Shuttlesworth), three professors of religion

(Maguire, Noyce and Swift), three theology students (Car

ter, Jones and Lee), and a law student (Smith) (R. A.

172-178). Coffin, Maguire, Smith, Noyce and Swift

traveled from Connecticut to Atlanta, Georgia, where they

were joined by Carter and Jones, who had begun in North

Carolina (R. A. 176). On Wednesday, May 24, 1961, the

seven set off from Atlanta on a bus trip across the South

to determine the extent of segregation in interstate bus

terminal facilities and to protest against segregation (R.

A. 117, 175, 176). They arrived at the Greyhound terminal

in Montgomery late Wednesday afternoon and stayed the

night (R. A. 176).

Martial law had been declared in Montgomery on the

previous Sunday, May 21, 1961 (R. A. 127-28). At

the request of Gen. Henry Graham, Commander of the Ala

bama National Guard detachment in Montgomery (R. A.

135), the petitioners notified the military authorities

of their intention to depart from Montgomery on Thurs

day morning, and a number of military vehicles were sent

to Rev. Abernathy’s home, where the petitioners were

gathered. A heavily armed military convoy escorted the

seven interstate passengers along with Abernathy, Walker,

Shuttlesworth, and Lee to the rear of the Trailways terminal

(R. A. 83, 129-31, 178, 218). Across the street from the

front of the terminal was a crowd of three to five hundred

persons (R. A. 77, 122, 131) under the control of more

than one hundred National Guardsmen and several civilian

law enforcement officers (R. A. 121-23, 219).

11

Still under military escort, petitioners entered the white

waiting room from the rear of the segregated terminal

(R. A. 106-07, 123, 132, 180). In the terminal at the time

were thirty to fifty persons including the eleven petitioners

and twelve to twenty-five Guardsmen and local officers

(R. A. 77, 111, 121, 132, 220). xlfter the seven travelers

bought tickets to Jackson, Mississippi (R. A. 132, 180),

all of the petitioners except Walker, who was making a

telephone call (R. A. 123-24), proceeded toward the lunch

counter, where some of them sat down on the available

seats and ordered coffee (R. A. 132, 133, 180). They were

served by the counter man (R. A. 184) after the waitress

had moved aside (R. A. 133), but within a very short time

Sheriff M. S. Butler arrested all eleven men pursuant

to a signal given by Col. Poarch, Staff Judge Advocate of

the National Guard (R. A. 76, 84, 89, 127).

It is uncontested that petitioners conducted themselves

in an orderly fashion. They were continuously respectful

toward the authorities who had escorted them to the termi

nal and accompanied them inside (R. A. 98, 124, 141,

185). Having been taken into the white waiting room

by these authorities, they were unmolested while the

travelers bought tickets and Walker used the telephone.

They were not told to refrain from buying a cup of coffee,

and when they sat down, they were neither requested nor

ordered to leave (R. A. 96, 139-40, 186, 211). They were

abruptly arrested by the authorities who had brought them

to the depot.

While the petitioners were in the terminal, but before

they moved toward the lunch counter, two or three white

men were ejected from the terminal for pouring coffee on

the counter seats. Although Col. Poarch viewed the con

duct of these “white toughs” as calculated to provoke a

breach of the peace, they were not arrested (R. A. 84, 91,

102, 133, 139, 146).

12

Sheriff Butler, the officer who arrested petitioners, tes

tified that he heard an “outburst” from the crowd outside

when the petitioners sat down at the counter, and that peti

tioners’ conduct could have caused a riot (ft. A. 98, 102-03).°

Col. Poarch stated that the crowd outside was very tense

and hostile toward petitioners (ft. A. 131); that the “air

was electric with excitement and tension” (ft. A. 134);

that tension inside the terminal increased because the

waitresses left the counter area when the petitioners ap

proached (ft. A. 133). Col. Poarch said that he had no

time to assess the attitudes or actions of the crowd out

side (R. A. 146), but he ordered the arrests when peti

tioners sought service because “you can’t yell ‘Fire’ in

a crowded theater” (R. A. 141). “They were arrested be

cause of the danger of provoking a riot causing injury to

themselves and to all other persons involved including the

National Guardsmen” (R. A. 149). Gen. Graham testified

that violation of the custom of segregation at that time

could have inflamed the crowd outside (R. A. 211, 220-221).

Floyd Mann, Director of Public Safety, thought that peti

tioners’ conduct was calculated to cause disorder in the bus

station (R. A. 120).

The size of the crowd outside the terminal was variously

estimated at three hundred, several hundred, and four to

five hundred (R. A. 131, 122, 77). Uncontradicted tes

timony establishes that at least one hundred troops were

lined up across the street between the crowd and the termi

nal (R. A. 100, 121-23, 178, 219). Traffic on the street

in front of the terminal was blocked off (R. A. 131).

Motorcycle policemen were patrolling it, and thirty-

five men from the Department of Public Safety were on

5 The state presented testimony that the inside of the terminal

was visible through the front windows to the crowd across the

street from the terminal (R. A. 103). This was disputed (R. A.

183-84).

13

hand (R. A. 121-22). Throughout the record there is

no reference to any overt action or threat on the part

of any person or group outside the station. One prosecu

tion witness testified that no one in the crowd was arrested

(R. A. 122).

A considerable amount of testimony was admitted with

respect to events of the week previous to these arrests.

It was established that a group of Freedom Riders arriving

in Montgomery on Saturday, May 20, 1961 were greeted by

an angry crowd (R. A. 80). Fighting broke out between

whites and Negroes and between local persons and visit

ing newsmen. Several were hurt, including some of the

Riders (R. A. 113-114, 225). An hour after the crowd

was dispersed, fighting broke out again (R. A. 114).

On the following day, Sunday, May 21, an angry crowd,

predominantly white, gathered outside Rev. Abernathy’s

Negro church where an evening meeting was being con

ducted (R. A. 81, 82, 114-15, 118). Bricks and rocks were

thrown, and a car was found burning when the police ar

rived (R. A. 81, 115).

Following the Sunday riot, martial law was declared by

the Governor (R. A. 128). Fourteen hundred National

Guardsmen, armed and equipped, were brought in; the

City was patrolled by armed convoys, and sentry posts

were set up (R. A. 128). Mr. Mann testified that

“racial unrest” continued through the week (R. A. 125).

A moving line of cars encircled the Greyhound station

on Monday when a group of Freedom Riders was ex

pected, and National Guard reinforcements “encountered

some difficulty in clearing the situation up,” but the Riders

did not appear (R. A. 128). A Negro minister was shot

at an unspecified time during the week, but the sus

pected perpetrators were arrested the following day

(R. A. 117, 129). Crowds gathered at various times at

14

air, bus, and train terminals (R. A. 129). On Wednes

day the National Guard escorted two groups of Free

dom Riders from Montgomery to the Mississippi line

(R. A. 119, 142-143, 206). Col. Poarch testified that the

populace and authorities thought the crisis was over on

Wednesday when the second group was safely escorted

to Mississippi, only to have the seven out-of-state petition

ers arrive in Montgomery (R. A. 142-144). Col. Poarch

said he had heard that these petitioners had been met by

“hostile crowds of some two thousand who stoned the car in

which they were riding” from the station (R. A. 143). An

other prosecution witness, an observer on the scene, stated

that they were greeted by a crowd of 150 to 200, that there

were no demonstrations at the time, and no bricks or other

objects were thrown (R. A. 154).

Undisputed testimony established that one group of Free

dom Riders departing from the Trailways Bus Depot on

Wednesday had used the lunch counter on an integrated

basis and had remained in the terminal for thirty to forty-

five minutes. They were not arrested and no incident oc

curred although 250 to 350 people were crowded around the

terminal (R. A. 223), approximately the same number as

on Thursday when petitioners were arrested (R. A. 122).

Sheriff Butler, Col. Poarch and Gen. Graham were aware

on Thursday that the Trailways lunch counter had been

integrated without incident on the previous day (R. A. 95,

135, 206). Petitioner Coffin stated that the petitioners also

knew of this when they proceeded to the counter on Thurs

day (R. A. 177).

The Trailways Bus Depot in Montgomery is “in the busi

ness of providing accommodations for interstate pas

sengers” (R. A. 165). It is used by three bus companies

engaged in interstate commerce (R. A. 165) and its “facili

ties are an integral part of interstate commerce” (R. A.

15

167). The lunch counter portion of the terminal is leased

by the three carriers to a corporation which in turn leases

it to another corporation which operates the counter under

the supervision of an employee of one of the interstate car

riers (E. A. 49).6

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

and Decided Below

In the Circuit Court, petitioners filed identical motions

to quash the complaint. Invoking the provisions of the

Fourteenth Amendment, petitioners alleged deprivation

of freedom of expression, freedom of religion, freedom of

movement, and freedom of association; denial of due

process arising from prosecution on vague charges; and

denial of equal protection of the laws. The motions to quash

also claimed that petitioners were arrested in order to en

force segregation in facilities serving interstate commerce,

in violation of Title 49, United States Code, Section 316(d)

and the commerce clause (Article I, Section 8) of the Con

stitution as well as the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment (E. A. 6-8; E. Ca.

5-7; E, Co. 6-8; R. J. 6-8; E. L. 5-8; E. M. 6-8; R, N. 6-8;

E. Sh. 5-7; R. Sm. 5-7; E. Sw. 6-8; E. W. 5-8). The mo

tions were overruled (R. A. 21; E. Ca. 20; E. Co. 21; R.

J. 21; E. L. 20; R. M. 21; R. N. 21; E. Sh. 20; R. Sm.

20; R. Sw. 21; E. W. 20).

6 The parties stipulated (R. A. 47, 49) that:

. . . The lunch counter portion of the terminal is leased

by the aforesaid carriers to the Interstate Co., a Dela

ware Corporation, which in turn leases the lunch

counter portion of the terminal to Southern House,

Inc., which operates the lunch counter portion of the

terminal subject to the supervision with respect to the

manner of serving white and negro patrons of R. E.

McRae.

16

Petitioners also demurred to the complaint, again raising

all of the objections made in the motions to quash. The

demurrers alleged, in addition, that each statute under

which petitioners were charged was vague, indefinite and

uncertain, and as such was unconstitutional on its face and

as interpreted and applied (R. A. 14-20; R. Ca. 13-19; R.

Co. 13-20; R. J. 14-20; R. L. 13-19; R. M. 14-20; R. N. 14-

20; R. Sh. 13-19; R. Sm. 13-19; R. Sw. 14-20; R. W. 13-19).

The demurrers were overruled (R. A. 21; R. Ca. 20; R.

Co. 21; R. J. 21; R. L. 20; R. M. 21; R. N. 21; R. Sh. 20;

R. Sm. 20; R. Sw. 21; R. W. 20).

After presentation of the state’s case (R. A. 161), a

motion was made on behalf of each petitioner (R. A. 47,

48) to exclude the state’s evidence (R. A. 22). This mo

tion made again all objections raised in the motions to

quash and demurrers, and in addition alleged a denial

of federal due process because the record was devoid of

proof of each element of the offenses charged (R. A. 22-27).

Attached to the motion to exclude was a copy of the tran

script (R. A. 229-472), opinion (R. A. 27-36), and decree

(R. A. 36-37) in the case of John R. Lewis, et al. v. Grey

hound Corp., et al., 199 F. Supp. 210 (M. D. Ala. Nov. 1,

1961), in which the federal court enjoined further arrests

such as those of the petitioners and found that the peti

tioners’ arrests were designed to enforce segregation. The

Circuit Judge granted the State’s motion to strike the ex

hibits and overruled the petitioners’ motion to exclude the

evidence (R. A. 163-64). The motion to exclude was pre

sented again at the conclusion of the case, and denied (R. A.

227).

Following the judgment and sentence in the Circuit

Court, identical motions for new trial were filed, renewing

all objections raised in previous motions (R. A. 40-44;

R. Ca. 23-27; R. Co. 24-29; R. J. 24-28; R. L. 23-27; R.

17

M. 24-28; E. N. 24-28; R. Sh. 23-27; E. Sm. 23-27; E. Sw.

24-28; E. W. 23-27). The motions for new trial were over

ruled (E. A. 46; E. Ca. 29; E. Co. 31; E. J. 30; E. L. 29;

B, M. 30; E. N. 30; E. Sh. 29; E. Sm. 29; E. Sw. 30; E.

W. 29).

The Court of Appeals of Alabama, in an opinion de

livered in the Abernathy case, expressly decided several

issues adversely to the petitioners, holding:

that the statutes creating the offenses of unlawful as

sembly, Sec. 407, Title 14, and breach of the peace,

Sec. 119(1), Title 14, Code, supra, do not, either in

themselves or as construed and applied to this defen

dant, abridge the right of free speech and assembly

guaranteed by the First Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States, nor has he been denied the

equal protection of the law guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States . . . (E. A. 485; appendix, infra, p. 10a).

Every issue was met by the Court of Appeals’ declara

tion that “The motion to quash [,] the demurrer, and the

motion to exclude the evidence were properly overruled”

(E. A. 485; appendix, infra, p. 10a).

The Court of Appeals accepted the following definition

of unlawful assembly:

an assembly of [two] or more persons, who, with intent

to carry out any common purpose, assemble in such a

manner, or so conduct themselves when assembled, as

to cause persons in the neighborhood of such assembly

to fear on reasonable grounds that the persons so as

sembled would commit a breach of the peace or provoke

others to do so. 2 Wharton’s Criminal Law, Sec. 853,

18

p. 721; Shields v. State, 184 Wis. 448, 204 N. W. 486,

40 A. L. E. 945; Aron v. Wasau, 98 Wis. 592, 74 N. W.

354 (E. A. 485-86; appendix, pp. IQa-lla).

and this definition of breach of the peace :

In general terms a breach of the peace is a violation

of public order, a disturbance of the public tranquility,

by any act or conduct inciting to violence or tending

to provoke or excite others to break the peace. Shields

v. State, supra. 8 [Am.] Jur. Sec. 3, p. 834 (E. A.

486 ; appendix, infra, p. 11a).

It held that:

No specific intent to breach the peace is essential to

a conviction for a breach of the peace. State v. Cant

well, 126 Conn. 1, 8 A. 2d 533; Cantwell v. Connecticut,

310 U. S. 296, 60 S. Ct. 900, 84 L. ed. 1213; 128 A. L. E.

1352. Nor is it necessary to constitute the offense of a

breach of the peace that the proof show the peace has

actually been broken. People v. Kovalchuck, 68 N. T. S.

2d 165; People v. Ripke, 115 N. Y. S. 2d 590 (E. A.

486; appendix, infra, p. 11a).

Asserting that the lawfulness of an act may be deter

mined by the circumstances surrounding it, the Court of

Appeals concluded that “it could not conceivably be said

that [petitioner] did not have knowledge that his conduct

was calculated to incite a breach of the peace . . . Under

the facts and circumstances adduced we think the question

of whether the defendant’s conduct was reasonably cal

culated to provoke a breach of the peace was one for the

trier of fact” (E. A. 487; appendix, infra, p. 12a).

In each of the other cases, the Court of Appeals rendered

no opinion but affirmed the convictions on the authority of

19

the Abernathy case (R. Ca. 34; R. Co. 36; R. J. 35 ; R. L.

34; R. M. 35; R. N. 35; R. Sh. 34; R. Sm. 34; R. Sw. 35;

R. W. 34). In all eleven cases, the Supreme Court of .Ala

bama denied certiorari without opinion (R. A. 496).

Reasons for Granting the Writ

The decision below conflicts with applicable decisions of

this Court on important constitutional issues.

I

The Decision Below Affirms Criminal Convictions

Based on No Evidence of Guilt.

A. Breach of the Peace

Petitioners were convicted because, as the Solicitor’s

Complaint alleges, they “did wilfully and intentionally seek

or attempt to seek service at a public lunch counter with a

racially mixed group.” It is not disputed that petitioners

had every right to be in the bus terminal and to use the

lunch counter on a desegregated basis. See 49 U. S. C.

§316(d ); Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454; Gayle v. Broiv-

der, 352 U. S. 903; Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373.7 Nor is

there the slightest indication that any of the petitioners

lost that right by engaging in conduct or language that

could be characterized as violent, profane, indecent, offen

sive or boisterous.

Nonetheless, it is the state’s theory that petitioners

abused their rights by exercising them in the presence of

7 Following these arrests, in September, 1961, the Interstate

Commerce Commission issued regulations barring racial segrega

tion in all bus terminal facilities serving interstate commerce. 49

C. F. R. §180(a)(1)-(10).

20

hostile observers who presented a threat of violence. Even

this outlandish theory is unsupported by the record. The

evidence of threatened violence consists merely of testi

mony that a crowd was outside, that violence had occurred

within the previous week, that the air was electric with

excitement, that a few white toughs had poured coffee on

the counter seats, that an “outburst” was heard when peti

tioners sat down, and that military and civilian authorities

believed that arrests were necessary to preserve the peace.

No one testified as to the behavior of the crowd. Not a

single incident of violence or unruly conduct was cited.

There is no evidence that any person in the crowd even

said anything critical of the petitioners or toward incite

ment of others in the crowd. Moreover, there was solid,

undisputed evidence that over one hundred armed National

Guardsmen were present on the scene, that they were well

deployed to control the situation, and that order had been

maintained since the military authorities had assumed

control. It was also shown conclusively that under very

similar circumstances this lunch counter had been desegre

gated without incident on the day before, and that the

petitioners were not even asked by the authorities to re

frain from using the lunch counter.

Conviction on such a record violates due process of law

under the rule of Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199.

The testimony was too speculative and remote to constitute

any evidence of a probable disturbance that could not be

handled with ease by the authorities on the scene. As in

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, and Taylor v. Louisiana,

370 U. S. 154, the evidence established merely that petition

ers were peacefully exercising their lawful rights in vio

lation of a local custom of segregation. In the Taylor case

there was evidence that onlookers became restless and some

21

climbed on chairs, but that could not ground a conviction

for breach of the peace.

Assuming, however, that the state had amply proved its

contention that petitioners were playing with dynamite by

ordering a cup of coffee, these convictions still could not

stand. The issue of threatened violence by those who op

pose the constitutional rights of others is not properly in

the case. As this Court said last term in Wright v. Georgia,

373 U. S. 284, 293, “the possibility of disorder by others

cannot justify exclusion of persons from a place if they

otherwise have a constitutional right (founded upon the

Equal Protection Clause) to be present.” [Citing Taylor

v. Louisiana, supra, Garner v. Louisiana, supra, and

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60], Numerous other de

cisions of this Court and others squarely establish the prin

ciple that the wrongful conduct of one person or group

cannot be used as a pretext for denying the constitutional

rights of others. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, affirming,

257 F. 2d 33, 38-39 (8th Cir. 1958); Watson v. City of Mem

phis, 373 U. S. 526. As Judge Brown of the Fifth Circuit

wrote recently,

. . . liberty is at an end if a police officer may without

warrant arrest, not the persons threatening violence,

but those who are its likely victims merely because

the person arrested is engaging in conduct which,

though peaceful and legally and constitutionally pro

tected, is deemed offensive and provocative to settled

social customs and practices. TV hen that day comes

. . . the exercise of [First Amendment freedoms] must

then conform to what the conscientious policeman

regards the community’s threshold of intolerance to

be. Nesmith v. Alford, 318 F. 2d 110, 121 (1963).

Without basing petitioners’ guilt on the threat of wrong

ful action by others, the state has no case at all. Its evi-

22

dence shows only that petitioners peacefully sought service

at a lunch counter, and this falls far short of establishing

a breach of the peace.

The relevant portion of Alabama’s statute condemns

“any person who disturbs the peace of others . . . by con

duct calculated to provoke a breach of the peace.” Pre

vious constructions of the statute shed no light on its

meaning.8 A normal interpretation would limit its appli

cability to situations in which 1) the peace of others was

actually disturbed, and 2) the action of the accused was

in some way offensive or wrongful, even if not calcu

lated or intended to create a disturbance. Even the broad

interpretations often given to the term breach of the peace,

e.g. Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, Edwards v.

South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229, do not eliminate the neces

sity of some type of wrongful, offensive or incitatory con

duct.

Unless injury to the delicate sensibilities of those who

oppose integration can be considered an actual disturb

ance of the peace, this record lacks any evidence of this

essential element of the offense, and the rule of Thompson

v. Louisville clearly applies. Likewise, there is no evidence

of any wrongful conduct by petitioners. Here, as in Wright

v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284, 285, “The record is devoid of

evidence of any activity which a breach of the peace stat

ute might be thought to punish.”

8 The only Alabama case approaching a construction of the

1959 statute (Tit. 14, §119(1)) is Mitchell v. State, 130 So. 2d 198

(Ala. App. 1961), cert, denied, 130 So. 2d 204 (Ala. Sup. Ct.). In

that case a conviction was reversed because the complaint, which

alleged merely that the defendant engaged in “conduct calculated

to provoke a breach of the peace”, was held to be too vague. It was

further declared that the evidence, showing only that the defendant

walked in front of complainants with his hands in his pockets and

acted “strutty”, was insufficient to make out an offense, even if well

pleaded.

23

Thus, whether or not the “evidence” of threatened vio

lence is considered, this case is governed by Thompson v.

Louisville, supra, Garner v. Louisiana, supra, and Taylor

v. Louisiana, supra.

B. Unlawful Assem bly

Title 14, Section 407 makes it a crime when “two or more

persons meet together to commit a breach of the peace, or

to do any other unlawful act. . . . ” Clearly, there is no evi

dence in this record of a breach of the peace as that term

is normally understood. Nor is there any evidence what

ever of the commission of any other unlawful act. Thus,

the applicability of Thompson v. Louisville, supra, seems

undeniable.

Conceivably, the state could reason that, notwithstand

ing any normal or reasonable interpretation of “breach of

the peace”, petitioners’ convictions under the breach of

the peace statute conclusively establish that they committed

a breach of the peace while assembled. This, of course,

would give rise to the objection that the unlawful assembly

statute is unconstitutionally vague (see Section II, infra).9

Regardless of that, the argument in Section I-A above

demonstrates that there was no evidence of breach of the

peace, no matter how broadly the breach of the peace

statute is construed.

The convictions under both the breach of the peace and

the unlawful assembly laws share an additional infirmity

which is related to the no evidence claim—e.g. that the peti

tioners’ conduct, which is here attempted to be made crimi

nal, was induced by state officers. The action of the military

officials in escorting petitioners to the bus terminal and

9 Furthermore, as to petitioner Walker, he was not even

charged with breach of the peace.

24

then arresting them for being there and nsing the public

facilities was comparable to an entrapment. By escort

ing petitioners, permitting them access to the “white”

waiting room, and not warning them they should not use

the lunch room or behave in any particular way, the mili

tary authorities impliedly asserted that they had the

situation in hand and that petitioners could exercise their

rights without any restriction imposed because of the

presence of a crowd outside the terminal. Thus petitioners’

alleged “crime” was the product of the “creative activity”

of state officers in leading the petitioners to believe that

they could freely use the terminal facilities. Cf. Sherman

v. United States, 356 U. S. 369, 372. It “offends a sense

of justice,” cf. Rochin v. California, 342 U. S. 165, 173,

that state officers should be permitted to induce an act to

be done and then punish it as criminal. Whether the crimi

nal law rule as to entrapment need be made a due process

matter generally is not necessary to decide. It is sufficient

that here the state-induced activity is conceded to be an

activity that is generally lawful. The only claim of illegality

results from the alleged special circumstances pertaining

to the crowd outside the terminal, which were known to

the state authorities when they escorted petitioners to

the terminal and did not warn them that any such extraor

dinary limitations would be placed upon their actions.

25

II

The State Statutes, as Construed and Applied to Con

vict Petitioners, Are So Vague, Indefinite and Uncertain

as to Offend the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

A. Breach o f the Peace

Conviction of petitioners under the provisions of a stat

ute outlawing “conduct calculated to provoke a breach of

the peace” is blatantly unfair. As construed and applied to

petitioners, this vague statute violated due process of law.

It has been established that petitioners, under the protec

tion of state authorities, peacefully entered a bus terminal,

bought tickets to an out-of-state destination and ordered

coffee at the lunch counter. They had every reason to be

lieve that their actions would be protected (R. A. 186, 211).

They were not refused service (R. A. 184). They were not

asked to move away from the counter, nor were they wrnrned

that their actions were considered dangerous (R. A. 96,

139-140, 186, 211). Others had done precisely the same

thing on the day before without being arrested (R. A. 95,

135, 206, 223).

Under these circumstances, they were arrested under a

broad, general, and vague statute. The Court of Appeals

construed the statute to mean that no actual disturbance of

the peace was necessary; that no specific intent to breach

the peace was necessary; that violent, profane, indecent,

offensive, or boisterous conduct was immaterial (R. A. 486;

appendix, infra, p. 11a).

The court’s holding means that whenever a person or

group performs an innocent and lawful act in the presence

of others who might object to the doing of that act, they can

26

be convicted under this statute. It means that the exercise

of constitutional rights in Alabama is subject to the irra

tional and unlawful actions of others and to the unbridled

discretion of the arresting officer to determine whether po

tential lawbreakers present a threat of disorder which

justifies suppression of inherently innocent conduct.

Surely the statute never warned petitioners that such was

the case. No previous construction of Alabama courts gave

the statute such a broad interpretation.10 In this case the

Court of Appeals relied completely on out-of-state authori

ties for its construction of the statute (R. A. 486; appendix,

infra, p. 11a). Moreover, it misconstrued those authorities

by accepting the proposition that completely innocent acts

are punishable as breaches of the peace when such was

never intended to be the law despite broad definitions of

breach of the peace.11

It is clear that a hypothetical precise law providing “it

shall be unlawful for any person or group to violate ac

cepted customs of racial segregation at bus terminal lunch

counters when in the opinion of law enforcement officers on

the scene such violation would tend to excite unruly crowds

in the vicinity” could not (because of the equal protection

clause) reach petitioners’ conduct. Cf. Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U. S. 1. But even if this proposition were doubtful, it is

manifest that a vague statute cannot provide the basis for

such a criminal prosecution. Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S.

284; Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229; Garner v.

Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157,198 (concurring opinion); Cantwell

v. Connecticut, 310 XL S. 296.

10 See note 6, supra.

11 Citing- 8 Am. Jur., Breach of the Peace, §3, p. 834, the Court

of Appeals quoted broad language, but omitted to mention that in

the same paragraph that authority assumes that actionable conduct

must be “unjustifiable or unlawful” or “wicked.”

27

This Court has often held that criminal laws must define

crimes sought to be punished with sufficient particularity

to give fair notice as to what acts are forbidden. As was

held in Lametta v. New Jersey, 306 TJ. S. 451, 453, “no one

may be required at peril of life, liberty or property to spec

ulate as to the meaning of penal statutes. All are entitled

to be informed as to what crimes are forbidden.” See also,

United States v. L. Cohen Grocery, 255 U. S. 81, 89; Con-

nally v. General Const. Co., 269 U. S. 385; Raley v. Ohio, 360

U. S. 423. The statutory provision applied to convict peti

tioners in this case is so vague that it offends the basic

notions of fair play in the administration of criminal justice

that are embodied in the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment.

Moreover, the statute punished petitioners’ protest

against racial segregation practices and customs in the

community; for this reason the vagueness is even more

invidious. When freedom of expression is involved the

principle that penal laws may not be vague must, if any

thing, be enforced even more stringently. Cantwell v. Con

necticut, 310 U. S. 296, 308-311; Scull v. Virginia, 359 U. S.

344; Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178; Herndon v.

Lowry, 301 IT. S. 242, 261-264.

B. Unlawful Assem bly

The same reasoning and authorities apply to the con

victions for unlawful assembly. Title 14, Section 407 is

hopelessly vague, condemning as it does not only a meeting

of two or more persons “to commit a breach of the peace”,

but also a meeting to do “any other unlawful act.”

“Breach of the peace” normally refers to some type of

boisterous, violent or otherwise blameworthy conduct; but

there was no evidence of any such actions by petitioners.

No prior construction of this law by the Alabama courts

28

warned that the law applied to purely innocent activity

which might provoke others to unlawful acts of opposition,

and surely the text of the law gives no hint that it is sub

ject to such a construction. Thus, the law fails to pro

vide any standard of criminality to guide a judge or jury

in applying it, and is patently subject to capricious enforce

ment.

The second clause of the law punishing a meeting “to

commit any other unlawful act” might have almost limit

less applicability. But except for the breach of peace

charges, the record in this case indicates no contention by

the state that petitioners’ action was unlawful. It is evi

dent that this clause, like the others discussed above, fails

to provide any warning that a legally and constitutionally

protected activity—sitting in an integrated group at a bus

station lunch counter formerly reserved for whites only—

can be punished as unlawful.

Moreover, as petitioners were charged under the alter

native words of the statute, to this day they cannot know

whether the state claims that they met to commit a breach

of the peace or met to commit some other unlawful act.

If either of the statutory clauses is unconstitutionally

vague, the conviction under this law must be reversed for

it cannot be known which part was relied upon by the trial

or appellate courts, Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S.

359; Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516; Williams v. North

Carolina, 317 U. S. 387.

29

III

The Arrests and Convictions of Petitioners on Charges

of Breach of the Peace and Unlawful Assembly Consti

tute Enforcement by the State of the Practice of Racial

Segregation in Bus Terminal Facilities Serving Interstate

Commerce, in Violation of the Equal Protection Clause

of the. Fourteenth Amendment, the Commerce Clause of

the Constitution, and 49 U. S. C, §316(d ).

This is an uncomplicated case of state enforcement of

segregation. Unlike several trespass cases brought before

this Court, there is no problem of private property rights

or private judgment, for the lunch counter operator here

was under a statutory duty to serve petitioners, Boynton

v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454, and he acknowledged that duty

by serving them (R, A. 184). The arrests were ordered

and executed by agents of the state who made no pretense

of responding to private choice.

Petitioners contend that no amount of evidence could

justify the state’s action on the ground that innocent and

protected conduct could lead to violence by others (see

Section I, supra). However, that issue need not be faced,

because petitioners were arrested for the purpose of en

forcing segregation in the terminal facilities. Judge John

son so found in Lewis v. Greyhound Corp., 199 P. Snpp. 210

(M. D. Ala, 1961), supra p. 7, and the record here is clear.

A large force of military and civilian law enforcement

officers was posted both inside and outside the terminal

(R. A. 77, 111, 121-23, 132). The crowd outside was under

control (R. A. 121-23), and the persons who poured coffee

on the counter seats were swiftly apprehended (R. A. 133).

Col. Poarch testified that dispersing the crowd was not

considered (R. A. 135). It had been allowed to form al-

30

though petitioners gave the military command advance

notice of their departure plans (R. A. 129). G-en. Graham

admitted his anger at the actions of petitioners (R. A.

208), which could well explain his failure to warn them

of the peril they supposedly created by sitting down. No

effort was made to offer petitioners protection if they

would leave the terminal and delay their trip until a

quieter time.

The authorities of the State of Alabama chose none of

these alternatives, but summarily arrested the racially

integrated group that was violating its customs. This,

of course, was in direct contrast to the failure to arrest the

persons who poured coffee on the seats.

When a state enforces the practice of racial segregation

in facilities serving interstate commerce by its adminis

tration of the criminal law, it denies equal protection of

the laws. Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 41; Turner v.

Memphis, 369 U. S. 350; Gayle v. Browder, 352 TJ. S. 903,

affirming, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala. 1956); Baldwin v.

Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961) ; Boman v. Bir

mingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531 (5th Cir. 1960); cf.

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1; Yich Wo v. Hopkins, 118

U. S. 356.

This use of the state’s machinery also conflicts with the

statute forbidding discrimination in facilities operated by

interstate motor carriers, 49 TJ. S. C. §316(d ); Boynton v.

Virginia, 364 TJ. S. 454, and constitutes an unlawful burden

on commerce in violation of Article I, Section 8 of the Con

stitution, Morgan v. Virginia, 328 TJ. S. 373.

The reasoning in this Section is equally applicable to the

convictions for breach of the peace and for unlawful as

sembly.

31

IV

The Decision Below Conflicts With Decisions of This

Court Securing the Fourteenth Amendment Right to

Freedom of Expression, Assembly and Religion.

By taking seats at the lunch counter in the Trailways Bus

Depot, petitioners were exercising not only their right to

use interstate transportation facilities unfettered by racial

restrictions, but also the rights guaranteed by the First

Amendment. Freedom of expression is not limited to ver

bal utterances. It covers picketing, Thornhill v. Alabama,

310 U. S. 88; free distribution of handbills, Martin v. Struth-

ers, 319 U. S. 141; display of motion pictures, Burstyn v.

Wilson, 343 IT. S. 495; joining of associations, NAACP v.

Alabama, 357 IT. S. 449; the display of a flag or symbol,

Stromberg v. California, 283 IT. S. 359. More in point, Jus

tice Harlan recognized that sitting in at a segregated lunch

counter in a southern state is a non-verbal form of expres

sion protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. Garner v.

Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 185 (concurring opinion). Several

of the petitioners were ministers, professors of religion and

students of theology, and all considered racial segregation

as contrary to their religious beliefs.

Because the petitioners’ right to be in the terminal and

to use the lunch counter is unquestioned, no issue is pre

sented as to the propriety of engaging in public expression

in a place where one is not invited. Garner v. Louisiana,

368 U. S. 157, 185 (concurring opinion).

Petitioners had the right to express their views unless

their conduct was “likely to produce a clear and present

danger of a serious substantive evil that rises far above

public inconvenience, annoyance, or arrest.” Terminiello v.

Chicago, 337 U. S. 1, 4. “A state may not unduly suppress

32

free communication of views, religious or other, in the guise

of conserving desirable conditions,” Cantwell v. Connecti

cut, 310 U. S. 296, 308.

In the Cantwell case, where the defendant was expressing

unpopular views that angered his listeners to the point of

specific threats of violence, this Court reversed the convic

tion for common law breach of the peace. Justice Roberts

wrote, “We have a situation analogous to a conviction under

a statute sweeping in a great variety of conduct under a gen

eral and indefinite characterization, and leaving to the ex

ecutive and judicial branches too wide a discretion in its

application.” Id. at 308. Therefore, . . in the absence of

a statute narrowly drawn to define and punish specific con

duct as constituting a clear and present danger to a

substantial interest of the State, the petitioners’ communica

tion, considered in the light of the constitutional guaranties,

raised no such clear and present menace to public peace

and order as to render him liable to conviction of the com

mon law offense in question.” Id. at 311. See also, Garner

v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 185, 199-204 (Harlan, J ., con

curring).

In Edwards v. South Carolina, supra, a large crowd had

gathered to observe the marching of almost two hundred

Negro students protesting to the Legislature against racial

discrimination and segregation. The Court, through Jus

tice Stewart, relied heavily on the fact that “there was no

evidence to suggest that onlookers were anything but cour

teous and no evidence at all of any threatening remarks,

hostile gestures or offensive language on the part of any

member of the crowd.” 372 U. S. at 231. This record, of

course, is identical in these respects.

With respect to the actions of the demonstrators, in

Edwards a huge group of demonstrators were present.

33

They sang and chanted after refusing to disperse upon

command by the city officials who had allowed them to dem

onstrate unmolested for forty-five minutes. Here, petition

ers merely sat down at a lunch counter. The Court’s

reasoning in Edwards is applicable here:

“We did not review in this case criminal convictions re

sulting from the even-handed application of a precise

and finely drawn regulatory statute defining a legisla

tive judgment that certain specific conduct be limited

or proscribed. . . . These petitioners were convicted of

an offense so generalized as to be . . . ‘not susceptible of

an exact definition.’ And they were convicted upon

evidence which showed no more than that the opinions

which they were peaceably expressing were sufficiently

opposed to the views of the majority of the community

to attract a crowd and necessitate police protection.” 372

U. S. at 236-37.

This case is not to be compared with Chaplinsky v. New

Hampshire, 315 U. 8. 568, where the speaker used fighting

words, nor Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315, where the

evidence showed that the crowd was pushing, shoving, and

milling around and that the speaker passed the bounds of

argument or persuasion. This is a clear case of state inter

ference with First Amendment freedoms in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment. Gitlow v. New York, 268 U. 8. 652;

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357; Stromberg v. Cali

fornia, 283 TJ. S. 359.

The reasoning in this Section is equally applicable to the

convictions for breach of the peace and for unlawful

assembly.

34

V

The Courts Below Deprived Petitioners of Due Process

and Violated the Supremacy Clause by Refusing to Ac

cept the Federal District Court Finding That Petitioners

Were Arrested to Enforce Racial Segregation.

The trial court erroneously excluded appellants’ exhibit

which contained the findings in the Lewis case that the

arrests of appellants were solely to enforce segregation

(R. A. 9,12-13). If this character of the arrests were estab

lished in this case it would be a complete defense to the

state’s charges of disorderly conduct and unlawful as

sembly, Boynton v. Virginia, supra.

The federal district court rendered a determination

that petitioners, in the exact circumstances which form the

basis of the state’s prosecution, were in the exercise of

a federal right granted by statute, and that the arrests by

the state were unconstitutionally designed to enforce

segregation. To refuse to give conclusive effect to the

declaration of federal rights both statutory and constitu

tional by a competent federal court is to nullify those

rights in violation of the supremacy clause (Article VI)

of the United States Constitution.

This state court action violates the due process clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment. The Restatement of Judg

ments, Section 68(1) states, with regard to collateral

estoppel, that “ . . . where a question of fact essential to

the judgment is actually litigated and determined by a

valid and final judgment, the determination is conclusive

between the parties in a subsequent action on a different

cause of action.” The rule has been applied in criminal

cases, United States v. Oppenheimer, 242 U. S. 85; Sealfon

v. United States, 332 U. S. 575, and was designed to elimi-

35

nate harassment of defendants and the inconsistent results

of duplicatory litigation as in this case. The “doctrine of

collateral estoppel is not made inapplicable by the fact

that this is a criminal case, whereas the prior proceedings

were civil in character.” Yates v. United States, 354 U. S.

298, 335. For the court below to decline to apply a doc

trine grounded in consideration of basic fairness, deprives

the appellants of due process of law.

Wolfe v. North Carolina, 364 U. S. 177, presented a situa

tion paralleling that here. In that case, however, the court

did not reach the constitutional issue because the petitioners

had failed to present the issue to the state court on appeal.

Petitioners here have made the necessary proffer of the

federal proceedings and duly excepted to their being struck

from the evidence (R. A. 161-164). Hoag v. New Jersey,

356 U. S. 464, is also no bar to appellants’ claim of denial

of due process of law, for there the issues and parties were

not the same. Hoag and other defendants were acquitted in

their first trial of robbing three persons in a tavern. It

was held valid to try them a second time on a charge of

having robbed a fourth person, present in the tavern, who

had not been named in the first indictment. In the instant

case there was substantial identity of parties. The criminal

case was prosecuted in the name of the state by the Circuit

Solicitor who was a defendant in the federal court case

along with the State Attorney General. The issue of

whether the arrests were designed to enforce segregation

is common to both proceedings.

36

CONCLUSION

Review by this Court is particularly appropriate in a

case such as this where a federal court has once deferred

to the state courts despite a clear finding that the arrests

were to enforce segregation. This it is submitted is a com

pelling case for review, not only because the error below

is so manifest, but also because the entire federal system

is jeopardized if a state can successfully defeat the plain

rights of citizens under the Constitution by such a gross

distortion of its criminal laws.

It is respectfully submitted that the petition should be

granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

F red D. Gray

34 North Perry Street

Montgomery, Alabama

Louis H. P ollak

127 Wall Street

New Haven, Connecticut

Attorneys for Petitioners

L eroy D. Clark

Charles S. Conley

F rank H. H eeeron

Solomon S. Seay, J r.

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Opinion of Court of Appeals in the Abernathy Case

T he State oe Alabama—J udicial Department

THE ALABAMA COURT OF APPEALS

October Term, 1962-63

3 Div. 101

R alph D. Abernathy

State

APPEAL PROM MONTGOMERY CIRCUIT COURT

P rice, Presiding Judge:

The appellant and ten other persons were convicted in the

court of common pleas of Montgomery County. In the cir

cuit court, by agreement, the cases were considered as being

tried separately, but evidence was introduced only in the

Abernathy case and was considered as introduced in all the

cases. There was a separate judgment of conviction as to

each defendant.

On appeal to this court it is stipulated that the transcript

of the testimony be copied into the record in this case only,

and be considered a part of the record in each of the other

cases, without the necessity of copying it into the record

of each of said cases.

The statutes under which the defendant was charged pro

vide:

2a

Opinion of Court of Appeals in the Abernathy Case

“Title 14, Sec. 407: If two or more persons meet

together to commit a breach of the peace, or to do any

other unlawful act, each of them shall, on conviction,

be punished, at the discretion of the jury, by fine and

imprisonment in the county jail, or hard labor for the

county for not more than six months.”

“Title 14, Section 119(1): Any person who disturbs

the peace of others by violent, profane, indecent, offen

sive or boisterous conduct or language or by conduct

calculated to provoke a breach of the peace, shall be

guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction shall be

fined not more than five hundred ($500.00) or be sen

tenced to hard labor for the county for not more than

twelve (12) months, or both, in the discretion of the

court.”

The evidence shows the eleven appellants involved in

these appeals are four white men and seven Negroes. On

May 24, 1961, the City of Montgomery was under martial

law as the result of riots following the arrival at the Grey

hound Bus Station on Saturday, May 20th, of three groups

of so-called “Freedom Eiders.” A race riot occurred on

Sunday night in the vicinity of the church of which the

appellant Abernathy was the pastor, in which riot several

thousand persons participated. Some of these appellants,

including Abernathy, were at the church during the riot.

The racial situation in the city was extremely tense. Some

fourteen hundred national guardsmen were on duty. The

stores were being patrolled by armed convoys.

The first groups of Freedom Riders had been given a

police escort to the Mississippi state line on the morning of

the day this additional group, composed of seven of these