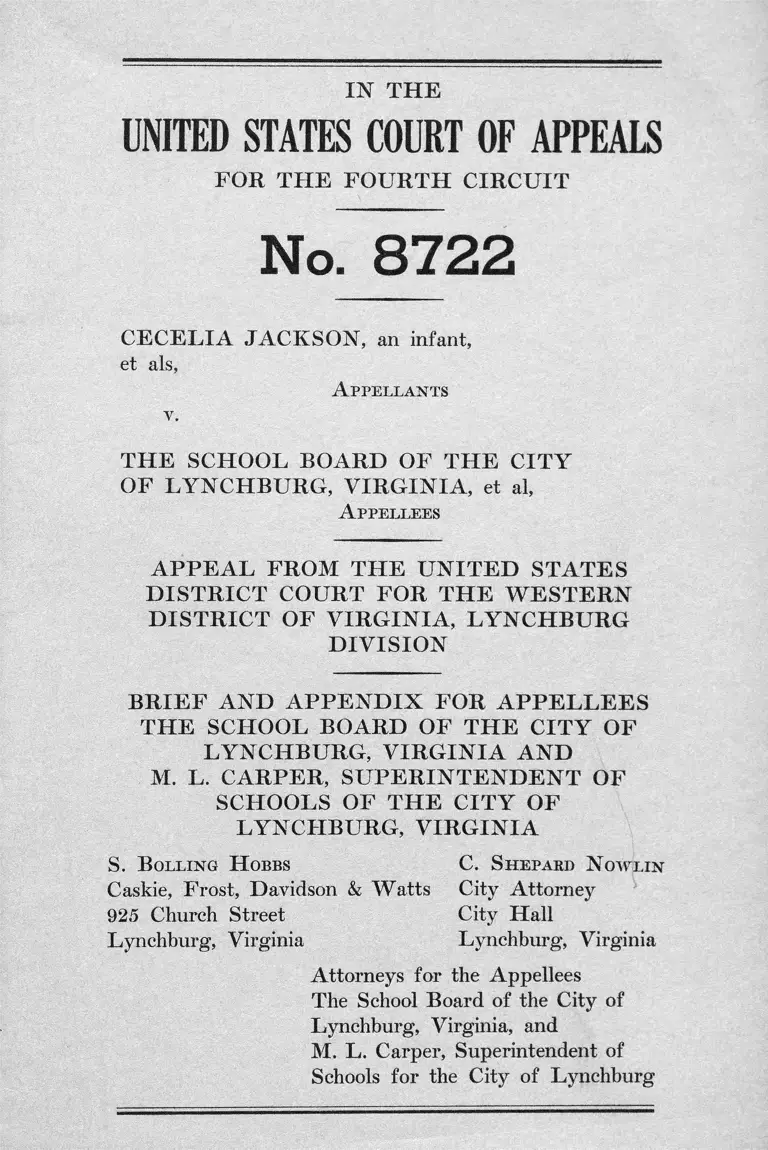

Jackson v. City of Lynchburg, VA School Board Brief and Appendix for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson v. City of Lynchburg, VA School Board Brief and Appendix for Appellees, 1962. 886af7e5-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b2650dbf-07bc-42b4-9d7d-46ed907b3825/jackson-v-city-of-lynchburg-va-school-board-brief-and-appendix-for-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I N T H E

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FO R T H E FO U R T H CIR C U IT

No. 8722

C E C EL IA JACKSON, an infant,

et als,

A ppella n ts

v .

T H E SCHOOL BOARD OF T H E CITY

OF LYNCH BURG, V IR G IN IA , et al,

A ppellees

A P P E A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES

D IST R IC T COURT FO R T H E W E ST E R N

D IS T R IC T OF V IR G IN IA , LY N CH BU RG

D IV ISIO N

B R IE F AND A P P E N D IX FO R A P P E L L E E S

T H E SCHOOL BOARD OF T H E CITY OF

LYNCHBURG, V IR G IN IA AND

M. L. CARPER, S U P E R IN T E N D E N T OF

SCHOOLS OF T H E C ITY OF

LYNCHBURG, V IR G IN IA

S. B o lling H obbs C. S h epa r d N o w l in

Caskie, Frost, Davidson & W atts City Attorney

925 Church Street City Hall

Lynchburg, Virginia Lynchburg, Virginia

Attorneys for the Appellees

The School Board of the City of

Lynchburg, Virginia, and

M. L. Carper, Superintendent of

Schools for the City of Lynchburg

1

IN D E X

P age

Statement of C ase_______________________________ 2

Question Involved_______________________________ 2

Statement of F a c ts______________________________ 2

Summary of Proceedings______________________ 2

The Desegregation P la n _______________________ 7

Local Situation and Facts in Support of P la n ___ 9

Argument

The Action of the District Court in approving

the School Board’s Plan of Gradual Desegregation

was Proper and Within the Guide Lines Pro

nounced by the Supreme C ourt----------------------------- 21

Conclusion ____________________________________35

11

C ITA TIO N S

Boson v. Rippy (5th Cir. 1960) 285 F. 2d 4 3 ___ 26,

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 74

S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873 (1954)_______ 21, 30,

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 75

S. Ct. 753, 99 L. Ed. 1083 (1955)_______ 2, 21,

Briggs v. Elliott (D. C. E. D., S. C., 1955) 132

F. Supp. 776 ________________________ 24, 29,

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 78 S. Ct. 1401, 3 L.

Ed. 2d. 5 (1958)_______________ 2, 23, 27, 31,

Dove v. Panham, 282 F. 2d. 256 ________________

Evans v. Ennis, (3rd Cir. 1960) 281 F. 2d. 385 _____

Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knox

ville (6th Cir. 1962) 301 F. 2d. 164_________ 26,

Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria, 278

F. 2d. 7 2 __________________________________

Jackson v. School Board of City of Lynchburg 201

F. Supp. 620 (W. D. Va. 1962)______________

Jackson v. School Board of City of Lynchburg,

203 F. Supp. 701 (W. D. Va. 1962)_________7,

Kelley v. Board of Education of the City of Nash

ville (6th Cir. 1959) 270 F. 2d. 209, cert. den.

361 U. S. 925 _______________________ 26, 29,

Mapp v. Board of Education of the City of Chatta

nooga, (D. C. E. D. Tenn., 1961) 5 Race Rel.

Rep. 1035 ______________________________ 26,

Robinson v. Evans (D. C. S. D., Tex., 1961) 6

Race Rel. Rep. 117_________________________

Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington

County (D. C. E. D., Va. 1956) 144 F. Supp.

239 ____________________________________24,

STA TU TES

29

32

34

30

34

. 5

.26

33

. 6

. 4

25

33

33

26

29

Code of Virginia, as amended

Sec. 22-232.1 - 22-232.17

Sec. 22-232.18 - 22-232.32 .

9

9

IN D E X TO A P P E N D IX

P age

Motion of Defendants to Approve Pupil School

Assignment Plan for the City of Lynchburg___ la

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1 7 a __________________________ 3a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1 7 b __________________________ 4a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1 7 c __________________________5a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1 7 d __________________________6a

Exerpts from hearing of March 15, 1962 ___________ 7a

Direct Examination of M. L. Carper

(for plaintiffs)________________________ 7a

District Court suggestions on modification

of p la n -------------------------- 8a

Virginia Pupil Placement A c t__________________ 10a

Ill

I N T H E

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOB T H E FO U R T H CIR C U IT

No. 8 7 2 2

C E C EL IA JACKSON, an infant,

et als,

A ppella n ts

v.

T H E SCHOOL BOARD OF T H E CITY

OF LYNCH BURG, V IR G IN IA , et al,

A ppellees

A P P E A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES

D IS T R IC T COURT FO R T H E W E ST E R N

D IS T R IC T OF V IR G IN IA , LY N CH BU RG

D IV ISIO N

B R IE F AND A P P E N D IX FOR A P P E L L E E S

T H E SCHOOL BOARD OF T H E CITY OF

LYNCHBURG, V IR G IN IA AND

M. L. CARPER, S U P E R IN T E N D E N T OF

SCHOOLS OF T H E CITY OF

LYNCHBURG, V IR G IN IA

2

STA TEM EN T OF CASE

This appeal was taken by the plaintiff s-appellants

from an order (Appellants’ App. p. 150a) of the United

States District Court for the Western District of Vir

ginia, Thomas J . Michie, Judge, entered on Api'il 18,

1962, approving a plan of desegregation of the public

school system of the City of Lynchburg, Virginia.

In compliance with an order (Appellants; App. p.

56a) of the Court below entered on January 25, 1962,

the defendant appellee School Board of the City of

Lynchburg submitted to the Court on February 24, 1962,

a plan (Appellants’ App. pp. 57a-59a) for admission of

pupils to the schools of the City without regard to race.

A t the suggestion of the District Judge at the hear

ing held on said plan on March 15, 1962 (App. 8a-9a)

paragraphs 4 and 5 of the plan submitted by the School

Board were slightly modified and it is from the order of

the District Court approving said plan as modified that

this appeal has been taken.

Q U ESTIO N INV OLV ED

Whether in approving the School Board’s plan of

desegregation as modified, the District Court committed

material error or acted improperly in exercising the

discretion vested in Federal District Courts under the

decisions of the Supreme Court in the cases of Brown v.

Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, and Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U. S. 1.

STA TEM EN T OF FACTS

Summary of Proceedings

Following denial by the Pupil Placement Board of

the State of Virginia of the applications of the four negro

infant plaintiffs, namely, Cardwell, Woodruff, Jackson

3

and Hughes, for transfer to E. C. Glass High School, a

previously all white high school, operated by the defend

ant-appellee School Board in the City of Lynchburg, Vir

ginia, this action was instituted on September 18, 1961,

by said infant plaintiffs-appellants by their parents and

guardians, and by said parents and guardians individually,

against the defendants-appellees, The School Board of

the City of Lynchburg, Virginia, M. L. Carper, Super

intendent of Schools of the City, The Pupil Placement

Board of the State of Virginia, and the individual mem

bers thereof, to require the defendants to grant the four

infant plaintiffs transfers to said E. C. Glass High School,

and for injunctive relief against the assignment and place

ment of pupils on the basis of race in the public school

system of the City of Lynchburg, and to require the de

fendants to submit to the Court a plan to achieve the

desegregation of the City schools.

Following a hearing on the merits at which evidence

was introduced (Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 17 a, 17 b, 17 c, 17 d,

App. 3a-6a and testimony of E. J . Oglesby, Transcript

of November 14, 1961, pp. 67-70), giving the results of

various standard I. Q., academic achievement and aptitude

tests, which indicated generally that the appellants Card-

well and Woodruff compared quite favorably in all re

spects with children in the class to which they were apply

ing at Glass High School, and which indicated that the

appellants Jackson and Hughes were, generally speaking,

below the median of the class to which they applied at

Glass High School, the Court below by order entered

November 15, 1961 (Appellants’ App. p. 35a) ordered

the appellants Cardwell and Woodruff admitted to the

ninth grade at the E. C. Glass High School at the be

ginning of the second semester on January 29, 1962,

denied the requested transfer of the appellants Jackson

and Hughes to said Glass High School, and took under

advisement the appellants’ prayer for further and more

general relief. With regard to the denial of transfer of

the appellants Jackson and Hughes, the Court, in its

order of November 15, 1961 (Appellants’ App. pp. 35a-

36a), stated:

“And the Court being of the opinion that it will be

in the best interests of the complainants Cecelia Karen

Jackson and Brenda Evora Hughes to remain in the

Dunbar High School in Lynchburg, Virginia, rather

than to be transferred to the E. C. Glass High School,

their prayer for assignment to the E. C. Glass High

School is hereby denied.”

No appeal from the Court’s order of November 15,

1961 was taken by the appellants or by the appellees-

school officials, but on November 27, 1961, the appellants,

Jackson and Hughes, who had been denied admission to

said Glass High School, filed a motion pursuant to Rule

59 (a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure to set

aside that portion of the Court’s order of November 15,

1961 which denied their request for admission to said

school, and to grant a new trial or rehearing on this issue.

Counsel for both the appellants and the appellees agreed

to submit this motion to the Court for decision without

the taking of further evidence and without further argu

ment except as set forth in the motion, and said motion

was overruled by the Court as set out in its opinion of

January 15, 1962 and reported at 201 F. Supp. 620

(W. D. Va. 1962) (Appellants’ App., pp. 87a-55a), the

Court stating in its said opinion:

“In the light of this evidence there can be no doubt

whatsoever but that if the four plaintiffs involved in

this case had been white children they would have been

assigned by the local authorities to Glass, irrespective

of distance involved and academic qualifications, and

they would never have been forced by the local au

thorities to submit themselves to the rigid distance and

academic placement rules of the Pupil Placement

Board. They have therefore been discriminated against

because of their race.

“I t would follow that if this were the only con

sideration involved all four of the children should now

5

be assigned to Glass. However, the welfare of the

child must also be taken into consideration by the

court. The court has examined with care all of the

exhibits in evidence with respect to these children,

including the results of the various aptitude tests and

the comparisons of the results thereof with results ob

tained at the same time in the same grades at Glass.

As a result the court has come to the conclusion that it

would not be in the best interest of two of the plaintiffs,

Cecelia Karen Jackson and Brendora Evora Hughes,

to be assigned to Glass. These reasons do not apply to

the other two plaintiffs, Owen Calvin Cardwell, Jr.

and Linda Darnell Woodruff, and the court, therefore,

has already entered an order requiring the school board

to enter them at Glass on January 29, 1962 which is

the first school day after the so-called ‘January break’

in the school year.

“Subsequent to the entry of the order aforesaid the

attorneys for the plaintiffs Cecelia Jackson and

Brenda Hughes and their parents and next friends

filed a ‘Motion for New Trial on Part of the Issues’,

in effect asking the court to reconsider its refusal to

assign those two children to Glass. Counsel for both

sides agreed to submit this motion to the court for

decision without the taking of further evidence and

without further argument except as set forth in the

motion. I have reconsidered the matter and am still of

the same opinion and therefore overrule the motion.

“I t is true that the cases appear to be in some con

fusion or even conflict as to the extent to which the

academic qualifications of applicants for transfer to

another school may properly be considered in these

desegregation cases and it has been stated that ‘An

individual cannot be deprived of the enjoyment of a

constitutional right, because some governmental organ

may believe that it is better for him and for others

that he not have this particular enjoyment.’ Dove v.

Parham, 282 F. 2d 256, 258.

6

“Nevertheless, in many cases academic qualifica

tions have been considered and placements based

thereon approved by the courts, at least in the initial

steps towards establishing a desegregated school

system. In Jones v. School Board of City of Alex

andria, 278 F. 2d 72, our Court of Appeals said

at p. 77:

‘The two criteria of residence and academic pre

paredness, applied to pupils seeking enrollment

and transfers, could be properly used as a plan to

bring about racial desegregation in accordance with

the Supreme Court’s directive.’

“The Court was there speaking of a plan to be

followed by the school board in making assignments

and transfers to bring about a desegregated school

system. But if they can be so used by a school board

they obviously can likewise be so used by a court

when called to pass upon the propriety of what a

school board of the Pupil Placement Board has done.

And it is the judgment of this court that it is not only

best for these two children but also for the achieve

ment of a successful and orderly desegregation of

Glass that these two children not be assigned to Glass

in its first year of highly limited desegregation.”

(Appellants’ App., pp. 45a-47a).

The appellants, Jackson and Hughes not having filed

notice of appeal within thirty days after the overruling of

their motion for a new trial, as contemplated by Rule

73(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, it is the

position of the defendant appellees that the District

Court’s order of January 15, 1962, denying transfer of

the appellants Jackson and Hughes to the Glass High

School, became final and that such denial is not in issue in

this appeal. If the Court should deem that it is a matter

to be considered in connection with this appeal, it is the

position of these appellees that such denial was proper,

7

as stated by Judge Michie in his above cited opinion, for

the orderly desegregation of the public school system of

the City of Lynchburg, Virginia, pursuant to the plan

approved by the District Court.

By way of further relief to the plaintiffs-appellants,

the Court below by order entered January 25, 1962 (Ap

pellants’ App. p. 56a) directed the appellee School Board

within thirty days thereafter to present a plan for ad

mission of pupils to the schools of the City without regard

to race, in accordance with the Court’s supporting opinion

of January 15, 1962 (Appellants’ App. pp. 37a-55a). On

February 24, 1962, the School Board filed with the Court

a plan of desegregation of the public schools of the City

of Lynchburg (Appellants’ App. pp. 57a-59a), to which

plan appellants filed objections on March 12, 1962 (Ap

pellants’ App. pp. 60a-64a). On motion of the defend-

ants-appellees School Board and Superintendent of

Schools (App. la-2a), for the approval of the plan and

after hearing evidence and argument on behalf of both

parties, on March 15, 1962 (Appellants’ App. pp. 65a-

135a) and after the plan had been modified at the sug

gestion of the District Court (App. 8a-9a), the Court

by order dated April 18, 1962 ( Appellants’ App. pp.

150a-151a), and in accordance with its supporting opinion

of April 10, 1962 reported at 203 F. Supp. 701 (W. D.

Va., 1962) (Appellants’ App. pp. 136a-149a) ap

proved the plan as modified and it was from the District

Court’s order of April 18, 1962 that this appeal was

taken.

T H E D E SE G R E G A TIO N PLA N

The plan of desegregation of the public schools of the

City of Lynchburg, Virginia, approved by the District

Court in its order of April 18, 1962 (Appellants’ App.

p. 150a), provides as follows:

“1. Commencing September 1, 1962, all classes in

Grade One shall operate on a desegregated basis, and

each September thereafter at least one additional grade

8

shall be desegregated until all grades have been de

segregated.

“2. In assigning pupils to the first grade and to other

grades as each of them is hereafter desegregated, the

Superintendent of Schools shall determine annually

the attendance areas for particular school buildings

based upon the location and capacity of the buildings,

the latest enrollment, shifts in population, and prac

tical attendance problems, but without reference to

race. One or more school buildings may be reserved,

in the discretion of the Superintendent, to provide

facilities within which to place pupils who are granted

transfers.

“3. Each pupil entering a desegregated grade will be

assigned, on or before April 15 preceding the school

year, to the school in the attendance area in which he

resides subject to rules and regulations promulgated

by the State Board of Education or as may be neces

sary in particular instances, provided only that the

race of the pupil concerned shall not be a consideration.

“4. Each pupil whose race is minority in his school

or class may transfer on request. The Superintendent

will determine the school to which such pupil is to be

transferred consistent with sound school administra

tion. There shall be no right to re-transfer during the

same school year *

“5. Nothing herein shall be construed to prevent the

assignment or transfer of a pupil at his request or at

the request of his parent or guardian for any reason

whatsoever.”*

*The words “during the same school year” were added to

Clause 4 and the words “for any reason whatsoever” were

added to Clause 5 of the desegregation, for clarification,

at the suggestion of Judge Michie of the District Court

(App. 8a-9a). The School Board of the City of Lynch

burg adopted the modifications suggested by Judge

Michie at a meeting held on April 10, 1962 and the

Court took notice of the modification in its order of

April 18, 1962, approving the plan, as modified.

LOCAL SIT U A TIO N AND FACTS IN

SU PPO R T OF PLA N

9

There are 11,750 pupils in the Lynchburg school sys

tem, approximately one-fourth of whom are negroes. The

school system has 23 elementary schools and 2 high schools.

Prior to the institution of these proceedings 17 of the

elementary schools were attended only by white pupils

and 5 of the elementary schools were attended only by

negro pupils. Dunbar High School, one of the two high

schools, was attended only by negro pupils and the other,

E. C. Glass High School, was attended only by white

pupils (Appellants’ App. p. 24a).

By virtue of the Pupil Placement Act the Virginia

Legislature has entrusted authority for the enrollment

and placement of pupils in the public schools of the

State of Virginia in the Pupil Placement Board, ap

pointed by the Governor, Code of Virginia, 1950, 1962

Supp. § 22-232.1 - 232.18 (App., 10a-16a), unless a

particular locality elects (by ordinance of its governing

body) to assume responsibility for the placement of pupils,

Code of Virginia, 1950, 1962 Supp. § 22-232.18 - 232.31

(App., pp. 16a-23a). The Lynchburg authorities not hav

ing elected to assume responsibility therefor (Transcript

of November 14, 1961, p. 88), the authority for the

placement and enrollment of pupils under State law at

the time of the advent of these proceedings was in the

defendant-appellee, Pupil Placement Board. Prior to the

entry of the order of the Court below on November 15,

1961 (Appellants’ App. p. 35a), no child had ever been

placed in a Lynchburg school whose pupils were of

another race. On April 21, 1961, one or more of the

infant plaintiffs-appedants mailed written applications for

transfer to the E. C. Glass High School to the School

Board (Transcript of testimony September 22, 1961, p.

61). These were apparently informal applications and on

or about June 29, 1961, formal applications on behalf of

the infant plaintiffs-appellants directed to the School

10

Board were made (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 11). These were

referred to the defendant-appelle Pupil Placement Board

for processing and said applications were finally denied by

the appellee Pupil Placement Board on August 28, 1961

(Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 5), after administrative appeal as pro

vided for by the Pupil Placement Act.

As far as the record in this case reveals, no applica

tions for transfers of negro pupils to previous all white

schools in the Lynchburg school system had ever been

received by the School Board or the Pupil Placement

Board prior to the applications of the infant plaintiffs-

appellants in April, 1961.

Following the receipt of the applications on April 21,

1961, the defendant-appellee School Board on its own

initiative directed its chairman to appoint a committee to

consider the advisability of adopting a voluntary plan of

desegregation (Appellants’ App. pp. 6.5a-66a). A four-

member committee was appointed which made a detailed

report to the School Board at its meeting on August 8,

1961, in which a majority of three members recommended

that the School Board adopt a plan of gradual desegrega

tion forthwith. (Appellants’ App. pp. 66a-68a). At the

direction of the School Board at its meeting on August 8,

1961, which was prior to the final denial by the Pupil Place

ment Board of the applications of the infant plaintiffs-

appellants for transfer to the E. C. Glass High School, a

special committee of the School Board was appointed to

consider and recommend a plan for the gradual desegrega

tion of the Lynchburg school system. This committee was

carrying out its work when the present court proceedings

were instituted on September 18, 1961. Thereafter the

committee withheld its report until the District Court’s

order of January 25, 1962, directing the School Board

to submit a plan of desegregation. (Appellants’ App. p.

71a).

The School Board, at a meeting on February 13, 1962,

adopted the plan recommended by its committee and which

11

was submitted to the District Court on February 24, 1962

(Appellants’ App. pp. 57a-59a).

On March 15, 1962, at the hearing held by the District

Court, on the appellees’ motion to approve the plan of

desegregation submitted by the School Board, the ap

pellees, as stated in the appellants’ brief at page 7, called

four witnesses in support of the plan:

B. C. Baldwin, Jr., a member of the School Board

and chairman of the two special School Board committees

above referred to; M. Lester Carper, Superintendent of

Schools of the City of Lynchburg; Herman Lee, Director

of Guidance and Testing for the Lynchburg schools; and

Duncan C. Kennedy, Chairman of the Lynchburg School

Board. The appellants recalled Superintendent Carper

as a witness.

The testimony of the witnesses is summarized at pages

7 through 11 of the appellants’ brief and is further sum

marized below.

TESTIM O N Y OF B. C. BA LD W IN , JR . (Ap

pellants’ App. pp. 65a-96a)

The School Board committees, of which Mr. Baldwin

was chairman, relative to the possible desegregation of

the Lynchburg school system, studied reports of desegre

gation of schools in Louisville, Baltimore, Norfolk and

other school systems (Appellants’ App. p. 66a), con

sulted with the Lynchburg-By-Racial Committee, and

conferred with various school authorities in Atlanta,

Georgia, Texas and Tennessee relative to desegregation

plans (Appellants’ App. p. 71a). Mr. Baldwin read into

evidence and was questioned concerning a report of the

School Board committee appointed to recommend a plan

of gradual desegregation, which was presented to the

School Board at its August, 1961, meeting, which report

states in part as follows:

“As a result of the rapid growth and expansion of

our city in recent years, many of our schools are over-

12

crowded. We are currently having to use six mobile

units as a measure of relief and it has been necessary to

adopt a policy denying the admission to our schools

of any county resident. During the current year, more

than 2100 pupils enrolled at E. C. Glass High School,

which school was designed for an enrollment of ap

proximately 1800. I t is estimated that by 1964-65

enrollment there will reach approximately 2800. Be

cause of this overcrowded condition and other factors,

recent studies and recommendations by the University

of Virginia Study Commission indicate an immediate

need for two additional junior high schools. The de-

segregation of all the high school grades at this time

and the admission of a substantial number of Negroes

will impose an excessive and intolerable burden on the

available facilities and personnel.” (Appellants’ App.

p. 74a)

Mr. Baldwin testified that the University of Virginia

Study Commission had been employed by the School

Board previous to his appointment to the School Board

(May, 1961), had recommended that two additional junior

high schools be built in the City, and that the Board was

considering the recommendations but no definite plans had

been made relative thereto (Appellants’ App. pp. 84a-

85a) ; that while Dunbar High School was approximately

eighty-five percent occupied, trailer units are used adja

cent to elementary schools to supplement class rooms and

that many cloak rooms and other rooms in schools not

designated for class rooms are used; that facilities generally

throughout the system are crowded; that the School

Board’s entire program (of construction) hinges largely

on the study being made by the University of Virginia

Study Commission Appellants’ App. p. 87a) ; that the

School Board does not operate bus transportation for

pupils and that children ride public busses; that finding

good teachers is a problem (Appellants’ App. pp. 87a-

88a).

13

TESTIM O N Y OF M. L E S T E R C A R PER (Ap

pellants’ App. pp. 97a-112a 128a-135a)

The principal points of Superintendent Carper’s testi

mony can best be pointed out by citing pertinent portions

of it:

Q. Will you state the problems which you antici

pate would arise from a desegregation of the school

system, either gradually or on the basis outlined by

the plan that has been presented? A. The one prob

lem that I can see and define most clearly is the

physical problem pertaining to building space. The

second which may well be a problem but not nearly

so well defined at the moment would be that matter

involving human relationships between people who are

uprooted and move in one direction, new associations,

etc., so I shall first discuss the building situation.

“Lynchburg is facing a rather critical building

problem at the moment. I have here the latest figures,

broken down by elementary schools, high schools, white

and negro, as now classified, as to their capacity and

the enrollment in those schools on the 26th day of

January, which was the latest report available from all

the principals’ offices.

“The capacity of the white elementary schools is

6,005. Presently we have 6,061 children entered. Now,

some of these schools are not filled completely to

capacity; some of them .‘ire overcapacited a hundred or

more pupils. I combined E. C. Glass and Robert E.

Lee, because at the present time we are committed to

the seven-five school organization, so the five years

in high school are in those two buildings. The capacity

at the present time is 2,550. The enrollment is 2,901.

In the negro elementary schools the capacity is 2,420.

The enrollment at the present time is 2,185. In Dunbar

High School the capacity is 840 and the enrollment is

773. The problem of buildings is further intensified by

14

the fact that many of the buildings are not located

where the people live. People are moving away from

the central section of town, for instance, to the out

skirts. The buildings in the center of the town are not

running at capacity and those on the outside are over-

capacited. That condition is a progressing condition.

“We make every effort to equalize, insofar as pos

sible, the pupil-teacher ratios within the schools and

between schools but, because of the mobility of people

and because of the dislocation of buildings, we can

never completely determine the total student body of

the school or the zone lines actually until mid-summer

or later, and even after we do that, doing the best we

can, not gerrymandering, Your Honor, but being

practical and setting up zone lines so we can eliminate

as many hazards as possible for the children to cross

to put them as close to the school as they can possibly

be to the one which they attend. Even at that, I can

remember that this last year we had individual con

ferences with better than a hundred parents, some of

whom wanted to transfer their children out of or into

a crowded school; some of whom we were requesting

to transfer their children because they were in a school

more crowded than the one to which they could go.

Then beyond that, we transported whole groups of

children from one school to another. As an illustration,

we have the seventh grade from Peakland going to

Garland Rodes.

“By the Court:

“Going permanently? A. Transferring for the

year. I t can be nothing permanent about it because of

the shift in population. As would be indicated right

now that the same transfers this next year will not

solve the problem which they solved this past year.

So, as long as we are running so near capacity in our

buildings, there will of necessity have to he a great

number of shifts from one school to another in order

to equalize loads.

15

“Now, as this relates to this particular problem,

I will indicate one situation. The members of the

School Board did not know that we had been working

up some information, just purely as information, but

we wanted to look at our problem to see what it might

be if we had the greatest amount possible of shifting.

Here is a school, for instance, Ruffner, with a capacity

of 255 and Armstrong with 340. Ruffner is now desig

nated a white school and Armstrong a negro school.

A large number of Negro youngsters pass Ruffner

going to Armstrong. In the first grade situation, all

of these youngsters would not go to Ruffner. As I

recall it, the figure was 61 children presently attend

ing Armstrong in the first grade. If they should go to

the school nearer them, there would be only eleven left

in Armstrong, and they would go into Ruffner,

Garland-Rodes and Peakland, each of which schools

are presently overcrowded, and you can see by divid

ing fifty more youngsters among the schools; over

crowded condition, would still be worse. In addition

to transferring the Seventh Grade and kindergarten

out of Peakland, we might have to get down to the

Sixth or Fifth or even further. We wanted to look at

the maximum displacement. Now, I give you that as

one particular instance.

“By Mr. Hobbs:

“Q. And that example involved only the first

grade? A. That example involved only the first grade;

yes, sir. I believe we found that there were more

Negro children passing Ruffner going to Armstrong

than the capacity of Ruffnei’, so you see, Your Plonor,

we have a sudden shift-when we have a sudden shift

like this, no one can say how the problem is going

to be worked out; we have to see the immensity of it

and see what can be done.

“Q. Mr. Carper, with regard to the physical

plants, can you review the construction that the city

16

has undertaken in the school system in the last few

years? A. I will attempt to do it. I don’t have the

figures here before me. The Chaii-man of the Board

is here, who has worked through that and he may

want to correct me.

“At the present time it’s been mentioned that the

Paul Monroe School is under construction. I know

of four new schools: Bedford Hills; Sheffield, two

white elementary schools: Dearington and Carl B.

Hutcherson, two Negro elementary schools, which I

would assume have been built within the last four or

five years.

“I would like to clear up one other situation if I

may. The question was raised about the school con

struction and the University of Virginia Survey. The

School Board employed the University of Virginia to

make certain surveys because the problems were so

intense, so much was involved, that it thought they

should secure the best judgment possible in future

planning in school house construction.

“I t had been thought for some little time that the

city was at the size, for instance, that it would be

appropriate to move from the seven-five organization

to the six-three organization, both with size and the

nature of the buildings now existing.

“The University of Virginia Committee has orally

given us the same opinion. Now the report has not yet

been submitted. We are expecting to receive that re

port on the 21st but the Junior High School construc

tion program would alleviate pressures both in the ele

mentary schools and high schools, inasmuch as they

would pull the Seventh Grade out of the elementary

and the Ninth Grade out of the high school, thereby

possibly eliminating any need for additional elemen

tary school construction for a few years to come.

“Q. Well, will you state whether the desegregating

of the schools is going to intensify the overcrowded

17

conditions? A. I t would seem, yes, that wherever they

desegregate, that is wherever additional children would

go into most any school in the city, it will overcrowd

that school and some other children" will have to come

out of it if we are going to maintain a reasonable

pupil-teacher ratio across the city. If there is any major

dislocation,—and I would say in a school of 255, fifteen

new pupils is a major dislocation.

“Q. Do you contemplate any other administrative

problems relative to the plan proposed by the School

Board? A. I concur in that plan simply because it will

give us one year of time to more nearly assess the

problems that are involved and probably would be

limited in scope to the point that we could handle the

problems that are involved. If we should become in

volved in a total situation, which would mean the dis

location of a fifth or more of our total student body,

somebody would probably become very aggravated

and some people hurt in the shifting process. The

problem is so big that we don’t have elbow room in

which to work, neither do we have the personnel to

work through all the problems, and there will be some

problems that will not be solved very satisfactorily.

“Q. What are your views on a gradual plan as

against a whole plan from an academic or scholastic

viewpoint of the pupils involved? A. Of course, the

pupil is the person most involved and most concerned,

and the pupil is my greatest concern. Any adjustment

for a child from one educational situation into another

one creates problems, of course, and require attention.

If you have a large number of children requiring

special attention, the time available is going to be

divided between all of those children in a much smaller

proportion than it would be if it were a smaller num

ber of children. I think also as we work out problems,

we gain experience; we leam how to handle things in

a routine fashion rather than create a way of handling

18

them. I believe that the one year in which we could

woi’k through a more localized or more confined situa

tion would give us sufficient experience to routinize

a number of things we wouldn’t have to put a great

deal of time on next year, and leave us with more time

to work with individual problems.

Q. So you think, as I gather, that you consider

this first year as an experimental proposition, to gain

experience. A. Right. We have no experience along

that line at all. I t will be a very experimental year;

yes, sir.” (Appellants’ App. pp. 98a-103a).

***• *•

Q. I f I understand, you said you endorsed the

plan of the city schools; you believe it is a workable

plan and one that the administration can live with?

A. I believe that, yes. The scope is such that we can

work out way through it. Certainly in connection with

the building situation, it is still going to be a problem

but I believe we can work ourselves out of that if we

do not involve too many people.

Now, in regard to the second problem, acceptance

of people generally to the whole idea, I have no way

of assessing that. I have no way of knowing what

problems will arise from it. (Appellants’ App. pp.

104a-105a)

Mr. Carper also testified as to the problems arising,

from the schools’ standpoint, from the mixing of large

groups of pupils of different abilities (Appellants’ App.

pp. 132a-134a), pointing out the probability of being

forced into a same type of ability grouping which at the

seventh and sixth grade levels would result in one such

group being predominantly negro and the other white

(Appellants’ App. p. 134a) ; and also pointing out that

dropouts (those leaving school) was greater among

whites than negroes.

19

TESTIM O N Y OF H ER M A N L E E (Appel

lants’ App. pp. 113a-131a)

Mr. Lee, Director of Guidance and Testing for the

Lynchburg schools, testified as to the wide disparity be

tween the academic achievement of negro and white pupils

in the Lynchburg schools; that it increases markedly in

the higher grades; that, as an example, in mathematics

in the ninth grade achievement, considering the national

norm at mid-point, the City white students had a median

of 64 percentile while the negro median was at 30 per

centile. (Appellants’ App. p. 116a). Although the ap

pellants objected to testimony of this nature, it is the

position of these appellees that such evidence is relevant

to the problems to be faced in formulating a plan for the

desegregation of a formerly segregated school system.

TESTIM O N Y OF DUNCAN C. K E N N ED Y

(Appellants’ App. pp. 122a-127a).

Mr. Kennedy, Chairman of the School Board, testified

that the School Board employed the University of Vir

ginia (Study Commission) in the fall of 1960 to make an

overall study of the Lynchburg school system, which was

expected to be completed within two years thereafter;

that while they had not made a final report, preliminary

reports indicate that they would recommend that the City

go from an elementary-high school system to a 6-3-3 sys

tem (6 grades of elementary school, 3 grades of junior

high school and 3 grades of high school) ; and that they

would recommend the building of two new junior high

schools; that after the School Board had formally adopted

such plan it would be necessary to acquire the land, pre

pare plans, and to receive allocations of fimds, and that the

earliest occupancy of such buildings would be September

of 1964.

Mr. Kennedy testified that in the eleven year period

since January, 1950, the City of Lynchburg had spent in

capital expenditures on sixteen school projects for the

City school system the sum of $9,353,000.

20

With regard to the School Board’s consideration of

the desegregation plan submitted to the Court, Mr.

Kennedy stated:

“Q. Now, Mr. Kennedy, with regard to the School

Board’s plan that has been presented to the Court.

Mr. Baldwin has reviewed in detail the facts leading

up to this. Was this the action of the School Board

as a whole, the adoption of this plan? A. Yes. I t

was with the approval of all the mem tiers of the

School Board with the exception of one, Mr. Hutcher

son, who dissented. I think the members of the School

Board discussed individually and with members of

Mr. Baldwin’s committee these facts so that they were

kept apprised of the progress during the committee’s

deliberation. The committee reports, both the majority

and minoi'ity, were mailed to the members of the School

Board prior to our February meeting and it was at

the February meeting that the School Board approved

the plan of the majority which had been presented to

them. I would say that with that one exception every

member of the School Board was in favor of this

particular plan.

“Q. Has the School Board over the past year dis

cussed problems that might arise from integration?

A. We have had very many discussions on that

question.

“Q. What is your personal view about the plan

presented? A. I didn’t vote on the plan because

normally the Chairman of the School Board does not

vote except in case of ties. I have worked close enough

with the committee and I endorse the plan. I think

it is the best plan I know of that could be adopted at

this time for the City of Lynchburg.

“Q. Has the School Board any policy about how

fast they might go with integration under the plan?

21

A. They have not. I think the School Board approved

the idea of having it flexible, as it is listed in the report,

and it is not a grade-a-year plan necessarily. I t is an

experimental plan and based upon the experience that

we gain in this next year on it, when the plan says we

will desegregate the first grade, the Board will then

determine, under the guidance of the Court, that what

we do is acceptable in working out the details of the

plan as approved. (Appellants’ App. pp. 124a-125a).

In summary, the evidence presented, clearly demon

strates the good faith of the school officials in adopting

and submitting a gradual plan of desegregation as op

posed to a more abrupt plan and in support thereof points

out the serious administrative and related problems that

will result from any plan that would require, particularly

in the initial stages, any more rapid desegregation then is

provided in the plan approved by the District Court.

A RG U M EN T

T H E ACTION OF T H E D IS T R IC T COURT

IN A PPR O V IN G T H E SCHOOL BOARD’S

PL A N OF GRADUAL D E SE G R E G A TIO N

W AS PR O PE R AND W IT H IN T H E G U ID E

L IN E S PRONOUNCED BY T H E SU PR EM E

COURT

Having held that racial discrimination in public edu

cation was unconstitutional in the case of Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873

(1954), the Supreme Court in its supplemental decision

in Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct.

753, 99 L. Ed. 1083 (1955) considered the manner in

which relief was to be accorded the numerous plaintiffs

involved in that particular litigation. In this connection,

Chief Justice Warren, in delivering the opinion of the

Court, stated, 349 U. S. at page 299:

22

“Full implementation of these constitutional prin

ciples may require solution of varied local school prob

lems. School authorities have the primary responsibility

for elucidating, assessing and solving these problems;

courts will have to consider whether the action of

school authorities constitutes good faith implementa

tion of the governing constitutional principles. Because

of their proximity to local conditions and the possible

need for further hearings, the courts which originally

heard these cases can best perform this judicial ap

praisal. Accordingly, we believe it appropriate to

remand the cases to those courts.

“In fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the

courts will be guided by equitable principles. Tradi

tionally, equity has been characterized by a practical

flexibility in shaping its remedies and by a facility for

adjusting and reconciling public and prvate needs.

These cases call for the exercise of these traditional

attributes of equity power. At stake is the personal

interest of the plaintiffs in admission to public schools

as soon as practicable on a non-discriminatory basis.

To effectuate this interest may call for elimination of

a variety of obstacles in making the transition to

school systems operated in accordance with the con

stitutional principles set forth in our May 17, 1954,

decision. Courts of equity may properly take into ac

count the public interest in the elimination of such

obstacles in a systematic and effective manner. But it

should go without saying that the vitality of these

constitutional principles cannot be allowed to yield

simply because of disagreement with them.

“While giving weight to these public and private

considerations, the courts will require that the defend

ants make a prompt and reasonable start toward full

compliance with our May 17, 1954, ruling. Once such

a start has been made, the courts may find that addi

tional time is necessary to carry out the ruling in an

23

effective manner. The burden rests upon the defend

ants to establish that such time is necessary in the

public interest and is consistent with good faith com

pliance at the earliest practicable date. To that end,

the courts may consider problems related to admin

istration, arising from the physical condition of the

school plant, the school transportation system, person

nel, revision of school districts and attendance areas

into compact units to achieve a system of determining

admission to the public schools on a nonracial basis,

and revision of local laws and regulations which may

be necessary in solving the foregoing problems. They

will also consider the adequacy of any plans the de

fendants may propose to meet these problems and to

effectuate a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory

school system. During this period of transition, the

courts will retain jurisdiction of these cases.”

The Supreme Court further amplified its guide lines

for the handling of school desegregation cases in its opinion

in the case of Copper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 78 S. Ct. 1401,

3 L. Ed. 2d, 5, stating at page 7 of the U. S. Reports:

“Of course, in many locations, obedience to the

duty of desegregation would require the immediate

general admission of Negro children, otherwise quali

fied as students for their appropriate classes, at partic

ular schools. On the other hand, a District Court,

after analysis of the relevant factors (which, of course,

excludes hostility to racial desegregation) , might con

clude that justification existed for not requiring the

present nonsegregated admission of all qualified Negro

children. In such circumstances, however, the courts

should scrutinize the program of the school authorities

to make sure that they had developed arrangements

pointed toward the earliest practicable completion of

desegregation, and had taken appropriate steps to put

their program into effective operation. I t was made

24

plain that delay in any guise in order to deny the

constitutional rights of Negro children could not be

countenanced, and that only a prompt start, diligently

and earnestly pursued, to eliminate racial segregation

from the public schools could constitute good faith

and compliance.”

The appellants on the basis of the first Brown case,

supra, assert in their brief that the appellees have been

under the positive direction of the Supreme Court since

1954 to initiate desegregation of the Lynchburg schools,

completely ignoring the fact that the Lynchburg school

authorities were not parties to said suit, and the many legal

obstacles placed in the path of local school boards by virtue

of various statutes enacted by the Legislature of Virginia,

from which the School Board’s powers to act in any

particular are derived.

In this connection also, it is pointed out that the record

in this case does not indicate that any request or applica

tion for transfer or assignment of a negro pupil to a

previously all white school in the Lynchburg school system

had ever been made prior to application of one or more

of the infant plaintiffs in April of 1961. As aptly stated

in a per curiam, opinion (generally attributed to Judge

Parker) of the three-Judge District Court in the case of

Briggs v. Elliott (D. C. E. D., S. C., 1955) 132 F. Supp.

776, the Supreme Court in the Brown case:

“* * * has not decided that the states must mix

persons of different races in the schools or must require

them to attend schools or must deprive them of the

right of choosing the schools they attend * * *: or

As stated by Judge Bryan in the case of Thompson v.

County School Board of Arlington County (D. C. E. D.,

Va., 1956), 144 F. Supp. 239, 240:

“I t must be remembered that the decisions of the

Supreme Court of the United States in Brown v.

25

Board of Education * * *, do not compel the mixing

of different races in the public schools, * * *. The order

of that Court is simply that no child shall be denied

admission to a school on the basis of race or color.”

Promptly after receipt of the infant appellants’ re

quest for transfer to E. C. Glass High School, and not

withstanding the fact that such transfers under Virginia

law were at that time being handled by the State Pupil

Placement Board, the local School Board, as hereinbefore

set out in the Statement of Facts, initiated action looking

towards the adoption of a voluntary plan of desegregation.

As stated by the District Judge in his opinion of

April 10, 1962, approving the plan in question, reported

in 203 F. Supp. 701:

“The good faith of the Board cannot be questioned.

Before this suit was instituted the School Board had

already appointed its own committee on desegregation

which had studied desegregation plans adopted else

where and had made good progress towards working

out a plan which would probably have been put into

effect this September even if there had been no litiga

tion. As far as I am advised Eynchburg is the only

community in the State of Virginia or, perhaps in the

entire territory of the Old Confederate States that has

voluntarily undertaken to plan for desegregation, all

of the others having awaited the start of litigation

against them before taking any steps of their own.

“And that the Lynchburg Board is still cooperat

ing is shown by their failure to appeal the order of

January 24th requiring them to file a plan of desegre

gation within 30 days. Most segregation orders are

appealed by the local board as a matter of course

and no one could have felt that an appeal in this

case would have been frivolous as there was a serious

question as to the right of the court to order the

Board to file a plan in view of the cases in this Circuit

26

arising from North Carolina mentioned in the opinion

of January 15, 1962, which seem to require the

exhaustion of legal remedies through the Pupil Place

ment Board by each child who might wish to go to an

integrated school.” (Appellants’ App. pp. 138a-139a).

In opposing the plan generally, on the basis that it

wdl require a longer period of time than is necessary to

bring about the desegregation of the Lynchburg school

system, appellants contend that the Lynchburg plan is a

“Twelve Year Plan” or a “Grade a Year Plan”. While

grade a year” plans of school desegregation have in

several cases not been approved by the courts, depending

on the particular factual circumstances, Evans v. Ennis,

(Del.) (3rd Cir. 1960), 281 F. 2d, 385, Goss v. Board of

Education of the City of Knoxville, Tennessee (6th Cir.

1962), 301 F. 2d, 164, such plans have also been approved

in a number of cases, Kelly v. Board of Education of the

City of Nashville (6th Cir. 1959), 270 F. 2d, 209, Cert,

den. 361 U. S. 925, Robinson v. Evans (Galveston)

D. C. S. D. Texas 1961, 6 Race Rel. Rep. 117, Mapp. v.

Board of Education of the City of C hattanooga,

D. C. E. D. Tenn., 1961, 5 Race Rel. Rep. 1035. See also

Boson v. Rippy, (5th Cir. 1960), 285 F. 2d. 43, which left

the matter up to the District Court.

While the Court below under the facts and circum

stances of this case might well have been justified in

approving a grade a year plan, the plan submitted to

and approved by the District Court is obviously not, and

is not intended by the appellees to be a grade a year plan.

By its express terms it provides:

“1. Commencing September 1, 1962 all classes in

Grade One shall operate on a desegregated basis, and

each September thereafter at least one additional grade

shall be desegregated until all grades have been de

segregated.”

27

The school officials testified that the first year of the

plan was to be a trial or experimental period to work out

problems and to gain experience in the handling of a

desegregated school system (Appellants’ App. p. 103a).

The District Court was clearly satisfied with the good faith

of the school authorities in moving ahead with the desegre

gation program as expeditiously as circumstances permit,

and very wisely agreed to a plan that would not limit or

commit the School Board to only one grade a year if the

problems encountered proved easier or more quickly solved

than anticipated. In any event, however, as the District

Court will retain jurisdiction of the case, if in the future

as the plan begins to operate, a showing is made to the

effect that more time is being taken than is necessary,

the District Court would have the power to see that the

plan of gradual desegregation is accelerated at a greater

rate than now provided. Aaron v. Cooper, 8tli Cir. 1957),

243 F. 2d. 361.

The appellants contend that no substantial adminis

trative problems have been shown to justify a gradual

plan of desegregation. To anyone cognizant with the prob

lems of school administration in Virginia and in most other

Southern States, common sense alone would indicate the

numerous administrative problems involved in the chang

ing of a school system, which has been historically segre

gated as to race since the beginning of a public school

system, into any form of integrated system. Regardless of

this, however, there is ample testimony by the school of

ficials in this case to show that any desegregation in the

higher grades at this time will greatly increase the already

serious overci-owding at the high school level, which will

continue until two new junior high schools contemplated

by the School Board can be built; that population shifts

have created problems in the overcrowding of certain

elementary schools which desegregation can only intensify;

that satisfactory academic adjustment between the negro

pupils and white pupils made necessary by a wide gap

between the median of the present academic achievement

28

and ability of the two races in the same grades, can be

made in a satisfactory manner only by dealing in small

numbers and in the lower grades. The evidence also indi

cates and there will undoubtedly be problems which will

require time to solve in teacher procurement, scheduling,

counseling, patron and public acceptance and dropouts

of pupils that will be created even by a gradual de-

segregation and that could become completely insurmount

able if the entire school system or a substantial portion

thereof should be desegregated at this time.*

*A repo rt of the Sub-Committee To Investigate Public School S tand

ards And The Conditions And Juvenile D elinquency In The D istric t

Of Columbia Of The Committee On The D istric t O f Columbia, House

Of Representatives E igh ty-Fourth Congress Second Session, United

S tates P rin ting Office 1957, while criticized in some circles as being

extrem e, nevertheless points up the numerous problem s th a t can

resu lt or partia lly resu lt from an abrupt change from a segregated to

an in tegrated school system, page 44:

“FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

H aving heretofore set out in considerable detail the various

phases of the D istric t of Columbia school operation and the problem

of juvenile delinquency as perta in ing to said schools, the subcommittee

a fte r a careful review of the established facts, concludes and finds th a t:

“ 1. The B oard of Education w ithout sufficient consideration of the

enormous problem, with scant preparation , and w ithout adequate study

or survey of known in tegrated school systems, too hastily ordered

the integration of the D istric t of Columbia schools.

“2. The forced in tegration of the schools in the D istric t of

Columbia grea tly accelerated an exodus of the white residents to the

suburban areas of V irginia and M aryland. The presen t exodus seri

ously threatens the educational, economic, cultural, religious and social

foundation of the D istrict. I f the exodus continues a t its presen t rate ,

the D istric t will become a predom inantly Negro community in the

not too d istan t future.

“3. The in tegration of the schools in the D istric t of Columbia has

focused attention upon the differences in ability to learn and edu

cational achievement between the average white and Negro students,

as reflected by the national standardized tests.

“4. The wide d isparity in m ental ability to learn and educational

achievement between the white and Negro students has created a most

difficult teaching situation in the in tegrated schools. So much of the

time of the teachers is being taken up in teaching the re ta rded students

tha t the capable students are not receiving the proper time and at-

29

The other principal objection of the appellants to the

desegregation plan approved by the District Court ap

pears to be Clause 5, reading:

“4. Each pupil whose race is minority in his school

or class may transfer on request. The Superintendent

will determine the school to which such pupil is to be

transferred consistent with sound school administra

tion. There shall be no right to re-transfer during the

same school year.”

The appellants apparently would like to eliminate all

freedom of choice relative to the plan. We believe, as did

the District Court, that this clause should be upheld under

the principles of freedom of choice expressed in Briggs v.

Elliott, supra, and by Judge Bryan in Thompson v. School

Board of Arlington County, supra. While this principle of

choice was completely ignored by the Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit in Boson v. Hippy, supra, which rejected

such a clause, the Sixth Circuit in the case of Kelly v.

Board of Education of the City of Nashville, supra,

expressly recognizing the principles expressed in Briggs

v. Elliott, supra, approved a similar clause in the Nash

ville plan. The reasoning of the Sixth Circuit in said

tention and are therefore failing to develop in accordance w ith their

educational ability.

“5. The m ajo rity of white principals and teachers faced the

challenge presented by integration with high morale, cooperation, and

determ ination. A t the outset many felt th a t in tegration was correct.

A fter 2 years of tria l, many of these same principals and teachers

testified th a t the in tegration of the schools has been of little or no

benefit to either race. The morale of some has been shattered, the ir

health has been im paired, and some have separated themselves from

the school system by resignation and early retirem ent. The replace

ment of these teachers presents a very serious problem to the D istric t

schools because white teacher applications have declined m aterially.

“6. D iscipline problem s and delinquency resu lting from the in te

gration of the schools have been appalling. I t was unexpected and

came as a g reat shock.

“W hile there were no new discipline problem s in the schools th a t

were not m aterially integrated , the unpreparedness for the turm oil

30

latter case, and which we deem to be legally sound, is set

out in the opinion of Judge McAllister in the following

language, 270 F. 2d at page 228:

“ (6) We come, then, to the transfer provision of

the plan, allowing the voluntary transfer of white and

Negro students, who would otherwise be required to

attend schools previously serving only members of the

other race; and allowing the voluntary transfer of any

student from a school where the majority of the stu

dents are of a different race. This provision does not

fall within the ban of the maintenance of segregated

public schools by cities where permitted — though not

required — by statute, such as was condemned by the

Supreme Court in Brown v. Education, 347 U. S. 483,

74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873. The district court, in the

instant case, considered that, in accordance with the

reasoning in Briggs v. Elliott, D. C. S. C., 132 F.

Supp. 776, 777, the transfer provisions did not violate

the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. In the Briggs case, it was declared, as we have

heretofore mentioned, that the Supreme Court has not

decided that the states must deprive persons of the

th a t ensued d isrupted the orderly adm inistration of the predom inantly

in tegrated schools.

“ This condition had a very pronounced effect in re ta rd ing the

educational progress of the students.

“A continuation of this situation will ultim ately destroy the ef

fectiveness of teaching in the in tegrated schools.

“7. T hat sex problems in the predom inantly in tegrated schools

have become a m atter of vital concern to the parents.

“One out of every four Negro children born in the D istric t of

Columbia is illegitimate.

“The number of cases of venereal disease among Negroes of school

age has been found to be astounding and tragic.

“The Negro has dem onstrated a sex attitude from the p rim ary to

high school grades th a t has g reatly alarm ed white paren ts and is a

contributing cause of the exodus of the white residents of the D istric t

of Columbia.

“The in tegrated schools have found it necessary to curtail greatly ,

and in many cases eliminate completely social activities form erly con

31

right of choosing what schools they attend, but that

all it has decided is that a state may not deny to any

person, on account of race, the right to attend any

school that it maintains. ‘This,’ said the court, as we

have previously quoted, on another aspect of this case,

‘under the decision of the Supreme Court, the state

may not do directly or indirectly; but if the schools

which it maintains are open to children of all races,

no violation of the Constitution is involved even though

the children of different races attend different schools.

* * * ‘Appellants say that the transfer plan is only a

scheme to evade the decisions of the Supreme Court.

In Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 17, 78 S. Ct. 1401,

1409, 3 L. Ed. 2d 5, it was said: ‘In short, the con

stitutional rights of children not to be discriminated

against in school admission on grounds of race or color

declared by this court in the Brown case, can neither

be nullified openly and directly by state legislators or

state executive or judicial officers, nor nullified in

directly by them through evasive schemes for segre

gation w h e t h e r a t t e m p t e d “ingeniously or in

genuously.” ’ There is no evidence before us that the

transfer plan is an evasive scheme for segregation. If

the child is free to attend an integrated school, and

his parents voluntarily choose a school where only one

race attends, he is not being deprived of his constitu

tional rights. I t is conceivable that the parent may

sidered a vital element in the education of students in the segregated

schools.

“8. The operation and maintenance of the D istric t schools have

been more adequately financed than the average school system. From

this standpoint they compare favorably w ith the outstanding school

systems in the N ation. The teachers’ salary scale is among the highest.

“The 2 years’ experience with the operation of the in tegrated

D istric t school system has conclusively shown th a t the cost of oper

ating the in tegrated schools will be substantially increased.

“Requests for additional funds by the school adm inistration and

the increased budget and capital outlay substantiate this finding.

“These demands are being made in the light of the fact th a t the

to ta l school population has not m aterially increased in the past 3 years.

32

have made the choice from a variety of reasons -—

concern that his child might otherwise not be treated

in a kindly way; personal fear of some kind of eco

nomic reprisal; or a feeling that the child’s life will be

more harmonious with members of his own race. In

common justice, the choice should be a free choice un

influenced by fear of injury, physical or economic, or

by anxieties on the part of a child or his parents. The

choice, provided in the plan of the Board, is, in law,

a free and voluntary choice. I t is the denial of the

right to attend a nonsegregated school that violates the

child’s constitutional rights. I t is the exclusion of chil

dren from such a school that ‘generates a feeling of

inferiority as to their status in the community that may

affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever

to be undone,’ as observed in Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 317 U. S. 483, 494, 74 S. Ct. 686, 691, 98 L.

Ed. 873. Such may be the tragic result, when children

realize that society is imposing a restriction upon them

because of their race or coloi\ The Supreme Court

remarked in the foregoing case that the effect of the

separation of students because of race was ‘well stated’

by the district court in the case, then on review, when

it declared:

“ ‘Segregation of white and colored children in

public schools has a detrimental effect upon the

colored children. The impact is greater when it has

the sanction of law; for the policy of separating

the races is usually interpreted as denoting the

“9. On the average, the Negro students, because of lim ited

achievements, are unable to compete scholastically w ith the more ad

vanced white students. This condition imposes upon the slower stu

dents a psychological barrier denoting inferiority , and m anifests itse lf

in social misbehavior.

“ 10. The committee concludes th a t the in tegrated school system

of the D istric t of Columbia is not a model to be copied by other

communities in the U nited States. On the contrary, it finds th a t the

in tegrated school system in the D istric t of Columbia cannot be copied

by those who seek an orderly and successful school operation.”

33

inferiority of the Negro group. A sense of in

feriority affects the motivation of the child to learn.

Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore,

has a tendency to (retard) the educational and

mental development of Negro children and to de

prive them of some of the benefits they would

receive in a racial (ly) integrated school system.’ ”

“Nevertheless, as stated in Brown v. Board of

Education, D. C., 139 F. Supp. 468, 469, 470, sub

sequent to the decision of the Supreme Court in the

prior Brown case:

“ ‘Desegregation does not mean that there must

be intermingling of the races in all school districts.

I t means only that they may not be prevented

from intermingling or going to school together

because of race or color.

I f it is a fact, as we understand it is, with

respect to Buchanan School that the district is in

habited by colored students, no violation of any

constitutional right results because they are com

pelled to attend the school in the district in which

they live.’

“ (7) While, in the instant case, the parent makes

the choice for the small child, that is the only reason

able method if such a choice may be made. We see no

deprivation of right, under the evidence before us.”

The Supreme Court denied certiorari in the Kelly

case, supra, 361 U. S. 924. The right of transfer of those

of a minority race in a particular school was also approved

in Mapp v. Board of Education of the City of Chatta

nooga, supra, and the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals reaf

firmed its ruling in the Kelly case, supra, in the recent case

of Goss v. Board of Education, supra (1962), recognizing

and pointing out, however, that such right of transfer

could not be used by the school authorities for the pur

pose of perpetuating segregation.

34

The appellants also object to the last sentence of

Clause 2 of the plan, which grants the School Superin

tendent the right to reserve one or more buildings to

provide facilities within which to place pupils who are

granted transfers. This provision is obviously one to meet

administrative problems in the event there are substantial

transfers and is certainly not invalid on its face. The ap

pellees recognize that this right cannot be used by the

school authorities for the purpose of perpetuating segre

gation.

The remaining objections of the appellants to the

desegregation plan approved by the District Court con

cern the desegregation of the kindergarten, the summer

school program, adult education programs and spelling

bees and other activities sponsored in the schools by out

side agencies (all of which are voluntary and not required

school programs). The appellants objections with regard

to these matters were all dealt with effectively and we

submit properly by the District Court in its opinion of

April 10, 1962, reported in 203 F. Supp. 701, and set

out in Appellants’ App. pp. 136a-149a, at page 147a. In

general these are matters that can be considered and

dealt with by the District Court from time to time as de

segregation progresses under the approved plan or persons

are denied participation in them.*

In both the second Brown case, supra, and Cooper v.

Aaron, supra, the Supreme Court recognized that the Dis

trict Court, because of its proximity to local conditions,

*Some of these m atters already appear to be moot in view of the fact

th a t on Ju ly 5, 1962, the School B oard of the City of Lynchburg

adopted a policy resolution reading as follows:

“W henever any contest is offered by an outside agency to any

grade or age group, all pupils in such grades or age groups in

the Lynchburg school system shall be eligible to p artic ipa te ,”

and on August 14, 1962, approved the recommendation of its instruc

tional committee to combine the electronics classes (adult education)

previously offered in the D unbar H igh School vocational departm ent

and the E. C. Glass H igh School vocational departm ent into a single

program to be held a t n ight a t the E. C. G lass H igh School.

35

can best perform the judicial appraisal needed to fit a

desegregation plan to the local conditions and problems

involved, and it is submitted that the plan formulated,

adopted and supported by the local School Board (which

has the primary responsibility, second Brown case, supra),

in fitting their requirements in the transition period, and

approved by the District Court in this case, and which

has already been put into effect is necessary in the public

interest and will result in the desegregation of the Lynch

burg school system at “the earliest practicable date.”

CONCLUSION

The action of the District Court is correct and the

judgment appealed from should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

S. B o llin g H obbs

C. S h epa rd N o w l in ,

Attorneys for the appellees

The School Board of the City

of Lynchburg, Virginia,

and M. L. Carper, Superintendent

of Schools for the City of Lynchburg

S. B o llin g H obbs

Caskie, Frost, Davidson & W atts

925 Church Street

Lynchburg, Virginia

C S h epa rd N o w lin

City Attorney

City Hall

Lynchburg, Virginia

la

A P P E N D IX

IN T H E U N IT E D STA TES D IST R IC T

COURT FO R T H E W E ST E R N

D IS T R IC T OF V IR G IN IA

LY N CH BU RG D IV ISIO N

C E C E L IA JACKSON, etc., et al,

P l a in t if f s

Civil Action

No. 534

v.

T H E SCHOOL BOARD OF T H E CITY

OF LYNCH BURG, et al,

D efen d a n ts

M OTION OF D E FE N D A N T S TO A PPRO V E

PU B LIC SCHOOL A SSIG N M EN T PL A N FOR

T H E C ITY OF LY N CH BU RG

Come now the School Board of the City of Lynch

burg, Virginia, and M. L. Carper, Superintendent of

Schools of the City of Lynchburg, Virginia, by counsel,

and move the Court to approve the plan of the School

Board of the City of Lynchburg, for the admission of

pupils to the schools of the City of Lynchburg filed in

this suit on February 24, 1962, and to continue this

case on the docket for such further orders as may from