Opening Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Working File

August 14, 1972

165 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Opening Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1972. 8c003ba0-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b2b143a5-8995-4b7d-be11-2fe3bcccab6f/opening-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

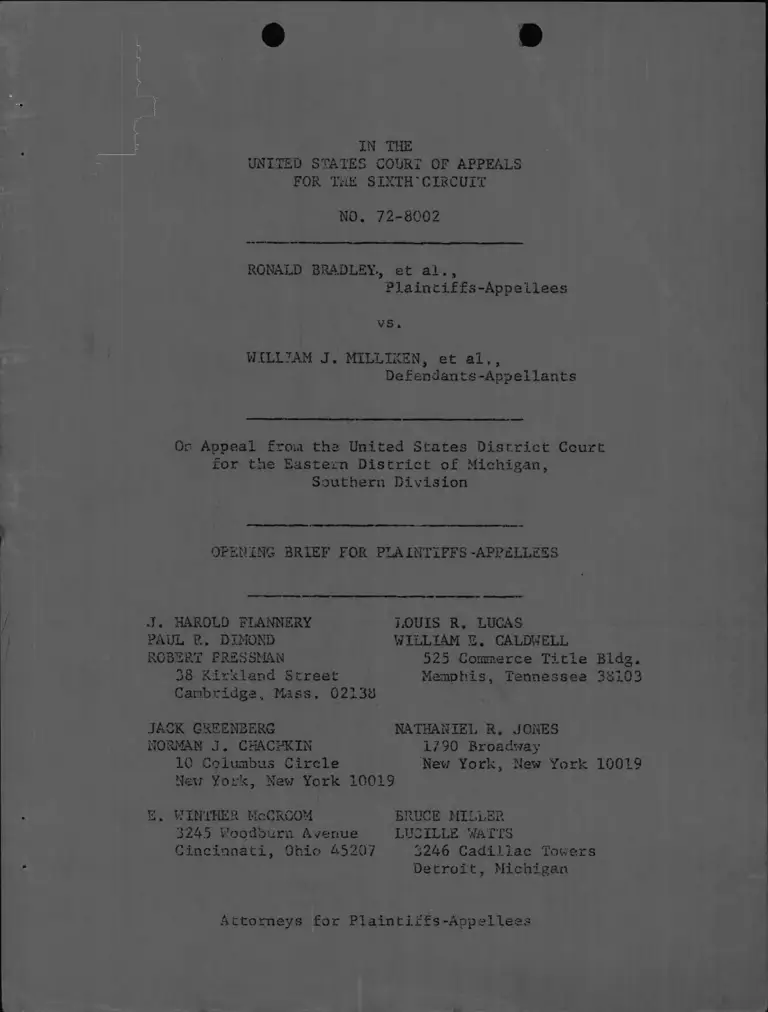

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH'CIRCUIT

■ NO. 72-8002

RONALD BRADLEY., et al.,

P3.ain t if fs-Appellees

vs.

WILLIAM J. MILL IREN, et al,,

Defendants-Appellants

On Appeal frou the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Michigan,

Southern Division

OPENING BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

J. HAROLD FLANNERY

PAUL E. DIMOKD

ROBERT FRES 8MAN

38 Kirkland Street

Cambridge., Mass. 02138

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACFKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, Haw York 100

'LOUIS R. LUCAS

WILLIAM S. CALDWELL

525 Commerce Title Bid

Memphis, Tennessee 381

NATHANIEL S. JONES

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

E. WINTHEK McCROOM BRUCE MILLER

3245 Woodburn Avenue LUCILLE WATTS

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207 3246 Cadillac Towers

De tro i t, Michigan

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

50 0

Table of Contents

Page

Table of authorities..........................

A Note on Record Citations ...................vi

Issues Presented ................ . . . . . . . 1

Statement of the C a s e ....................... 4

A. Introduction ........................ 4

B. Statement of Facts.....................8

1. The Violation -- State-Imposed

r ' Public Segregation . 8

2. Faculty Racial Identifiabi'lity . . 40

C. The R e m e d y .......................... 48

Argument.................. ....................62

I. The Violation...................62

II. The Remedy.......................81

III. State Responsibility ........... 101

IV. Section 803, Education Amendments

of 1972 . . . . 108

A. Ripeness.................... 109

B. Applicability.............. 110

C. Constitutionality .......... 121

Conclusion.............................. .. 126

-i-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Pages

Adkins v. School Bd, of Newport New,

148 T. Supp, 430 (E.D. Va., 1957) ...........

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ.

396 U.S. 19, 1218 (1963) ....................

Armstrong Paint & Varnish Works v. Nu-Enamel

Corn., 305 U.S. 315 (1968) ............... .

Attorney General v. Lowrey, 131 Mich.,

639 (1902) ...................................

Baker v, Cara*. 369 U.S. 186 (1962) .............. .

Barksdale v. Springfield School of Commissioners

348 E.2d. 261 (2d. Cir 1965) ............. .

Bivins v. Bifcb- County Bd. of Educ. 424

F. 2d, 97 v 5th Cir. 1970) ...................

Boddie v. Connecticutt, 91 S. Ct. ,

780 (1971) ..................................

Booker v. Special School Dist. No. 1, Minneapolis

F. Supp. (No. 4 71 Civil 382

D. Minn. May 24,'1972) ......................

Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Educ. F.2d. ,

No. 71-3028 (5th Cir. Feb. 23,”1972) . .77.77. ,

Bradley v. Milliken, 433 F.2d., 897 (6th Cir. 1970)

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond,

F, 2d, (C. A . 4, 1972) .... .7............

Brown v. Bd. of Education, 349 U.S, 294 (1955) ....

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bds. ,

396 U.S. 290 (1970) ....... ..................

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School

Dist., ___ F.2d, (No. 71-2397, 5th

Cir, August 2, 1972T ........................

?7r 9 8

us, es; /i/,

/oH,

/& $/

//£/

ers,

A/, lo,

/ooL

*7/

/?4>

5 % H U,

-n, 7s;/«,

Clemons v, Bd, of Educ. of Hillsboro, 228 F.2d,

853 (6th Cir. 1956) ........................

Cooper v, Aaron, 358 U,S. 1 (1958) .............

Davis v. Bd. of Commissioners, 402 U.S.

33 (1971) ........ .........................

Davis v. School Dirt, of Pontiac, 433 F.2d. 573

(6th Cir. 1971), cert, deviced, 402 U.S.

913 (1971) .................................

Deal v. Cincinnati Bd. of Educ., 419 F,2d. 1387

(6th Cir, 1969), 369 F.2d. 55 (6th Cir. 1966)

Dowell v, Bd, of Education of Oklahoma City ,

338 F. Supp. 1256 (W.D. Okla. 1972) ........

L,

Dunn v. Blumstein, U.S, , 31f'Ed. 2d.

274 (1972) ...7.7.7..... 7.7.7..............

Ex pqrte McCeBdie, 74 U.S. 506 (1869) ...........

Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908) ........... .

Forsyth County Bd, v. Scott, 404 U.S. 1221 (1971)

Franklin v. Quitman County Bd of Educ., 288

F. Supp. 509 (N.D. Miss. 1968) .............

Godwin v, Johnston County Bd, of Educ,, 301

F. Supp. 1339 (E.D. N.C. 1969) ..............

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) .....

Green v. New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) ....

Griffin v. Prince Edward Co. 377 U.S, 218 (1964)

Guev Heung Lee v, Johnson. 404 U.S. 1215 (1971) ,.

Hall v, St. Helena Parish School Bd. , 197

F. Supp. 649 (E.D. La. 1961) ...............

Haney Bd. of Sev**r<.Co., 410 F,2d. 920,

same, 429 1.2,1. 364 (8th Cir. 1970).........

Hunter v. City of Pittsburg, 207 U.S. 161 (1907) .

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) .........

.7/, 75,73,7^

■ H

9^,

<W //oo/

6.3 , . L &73, 7 7

.

.

• 9*,

. //7j

. ?os,

. e?

. 70, 97, /0*t

, 93, 77,97, 78,

. /OS,

-HI ~

/23,

Jackson v. Marvell School Dist, No. 22, 425 F.2d.

211 (8th Cir. 1970) ............ ............... 7 S

James v. Valtiessa, 402 U.S. 137 (1971) .......................... / £ */

Jenkins v. Twp. of Norris School Dist., 279 A.2d. 617

(N.J. Sup. Ct. , 1971) ....................................... <98,

Johnson v Jackson Parish School Bd. 423 F,2d. 1055

(5th Cir 1970) ................. ............................. 7 2 ,

Johnson v. San Francisco Unified Sep. School

Dist., 339 E. Supp. 1315 (N.D. Calif. , 1971) ............... 7 / ^ 7 5 ;

Jones v. Grand Ledge Public Schools, 349 Mich. 1

(1957) .... .................................. .............../ O*/>

Katzenbach v. Morgan 384 U.S. 641 (1966) ...... ............... /72,

Kelley v. Metro. County Bd., 436 F,2d. 856 (6th Cir. 1970) ........ /O ob,

Kelly v. Guinn, 456 F,2d, 100 (9th Cir, 1972) ..... ...............

ZOO C-y

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 396 U.S. 1215 (1969) ................

Kramer v. Union Free School Dist., 395 U.S. 621 (1969) ........... <?£’-?/,

Lee v, Macon County Bd. of Educ., 231 F. Sunp.

743 (M.D. Ala. 1963) ................ ........................<?(,, 98)

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Bd., 444 F,2d.

1400, 446 F, 2d. 911 (5th Cir. 1971) ......................... /OO^t

McDonald v Bd. of Elec. Comm., 394 U.S. 802 (1969) ............... /

McLauRjn v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637

(1950) ...................................................... 7*7.,

McNeese v. Bd. of Educ., 373 U.S. 668 (1968) ..................... 72 ,

Monroe v, Bd. of Comm . 391 U.S. 450 (1968) ....................... 2 3 )

North Carolina v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971) ........ .......... . 9 7 ,? B ,/3

Northcross v, Memphis Bd. of Educ,, 333 a

F. 2d. 661 (6th Cir, 1964) .................................... <>7,75,

Plaquenines Parish School Board v. United States

415 F.2d. 817 (5th Cir. 1969) ................................ M0/

IV

Reitman v, Mulkey, 387 U.S, 369 (1967)

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1969)

Reitman v, Mulkey, 387 U.S, 369 (1967) ..............................

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1969) ............................... ?By

School Dist. No. 1 v. School Dist. No. 2, 390

Mich. 678 (1959) ...............................................

School Dist No. 7 v, Bd. of Educ., No. 9585

Kent Cir . Ct........................... .........................

Shapiro V, Thompson, 397 U.S. 259 (1970) ............................ /67j /0(et

Shelton v. Tucker, 369 U.S. 979 (1960) ..............................

Sloan v. Tenth School Dist., 933 F.2d.

587 (6th Cir. 1970) .............................................

Smith v. North Carolina Bd. of Educ. , 999

F.2d. 6 (9th Cir 1971) .........................................

Smuck v. Hobson, 908 F.2d. 175 (D.C. Cir. 1969) ..................... “70,

Spangler v, Pasadena City Bd of Ed., 311 F. Supp.

" 501 (C.D, Calif., 1970) ........................................

Stout v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ,, F.2d,

7 0 , 1 /, 7 2 ,

73,7V, 7%

(No. 29886 5th Cir, 1971) ..................................... 97,

Stungis v. Allegan County, 393 Mich,, 209 (1955) .............. . /#Y,

Swann V. Charlotte Mecklenburg Bd, of Educ., 902 U.S. 1

(1971) ..... ..............•.................................... <

/Olt

Turner v. Warren Cor. Bd. of Educ., 313 F. Supp. 330

(E.D. N.C, 1970) .......................... .....................

United States v. Greenwood Mun, Sep. School Dist., 906

fa 74,

s;39

q 2., 100/oc

/ooc. , / '<, /;$

F .2d. 1086 (5th Cir. 1969) ..................................... n

United States v. Bd of School Comm, of Indianapolis, 332

F. Supp, 655 ( S.D. Ind. 1971) ......... ........................ ' 70 , iS jto O o .

United States v, Jefferson County Bd. of Educ.,

372 F,2d, 878 (5th Cir. 1966) .................................. i l l , /'T,

United States v. Klein, 80 U.S. 128 (1872) ........ ..................

United States v. School Dist. 151, 909 F.2d,

1125 (1968) ___................................................. 7 1, l Y j H l j

V

u.s.United States v. Scotland Neck Bd, of Educ. ,

_____, 406 W. 4817 ...................

United States v. State of Texas, 447 F.2d. (5th Cir. 1971) ..

United States v. Texas Educ, Agency, (Austin Independent

School Dist.), __ F.2d. ____ (5th Cir. Aug, 2, 1972,

No. 71 2508) same ,431 F.2d. 1313 (5th Cir. 1970) .....

Wayne County Jail Inmates v. Wayne County Bd.

of Commissioners, C.A. No. 173217, Wayne

County Cir, Ct. , July 28, 1972) ......... .............

G%7/,

-13,?!^

/ &i / (& __

7 ^ 7 *

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia

U.S. __ 40 L.W. 4806 (1972) .

Yakus v. United States 321 U.S. 414 (1944)

/2-6,

Constitution and Statutes

Michigan Constitution, Art. VIII, Sects,, 2,3

Education Amendments of 1972 ................

Michigan Compiled Laws, 340,1 ..............

t o 8

/*¥ ■

Authorities

3yThomas, School Finance and Educational

Opportunity In Michigan (Lansing 1968)

A Note on Record Citations

Throughout this Brief references to matters contained

in the joint printed appendix will be in the form "A.___"

(e.g., A.Ia99)

Since a leage portion of the record below consists of

large demonstrative exhibits (maps and overlays, etc.), as

well as some rather voluminous documentary exhibits, there

will, of necessity (and in some instances because of inad

vertent omission from the appendix), be some citation to

the original record, which will be in the following form:*

Transcript of the trial on the merits beginning April 6,

1971, by volume number and page--e.g., 35 Tr. 99. Exhibits

from the trial on the merits will be designated by the offering

party and exhibit number--e.g., P.X. 99 (plaintiffs), D.X. 99

(Detroit Board defendants), D.F.T.X. 99 (intervening defen

dant Detroit Federation of Teachers).

Transcript of the hearing on Detroit-only desegregation

plans beginning March 19, 1972, by volume number (Roman) and

page number--e.g., IV Tr. 99. Exhibits from this hearing will

be designated by C"~~e.g., P.C. 4 (plaintiffs), D.C. 4

(Detroit Board), etc.

*Also, some matters which plaintiffs requested to be

included in the joint appendix were omitted by defendants-

appellants.

-vih-

Transcript of the hearing on a metropolitan remedy

beginning March 28, 1972, by volume number (Roman), "M"

and page--e.g., IVM Tr. 999. Exhibits from this hearing

will also be designated by "Mn--e.g., P. M. 12, etc.

Citation to transcript of any other hearing will be

indicated by the date on which the hearing began and the

page number--e.g., 11/4/70 Tr. 99.

Pleadings and orders not contained in the appendix will

be referred to by title and date of filing .

Where appropriate, appendix citations will be supported

parenthetically with a designation of the matter referred to--

e.g., A. 999 (P. X. 13); this will be particularly true with

regard to the district court's various rulings, to which the

following abbreviations pertain:

"Mem. Op. " - Ruling on Issue of Segregation (Sept.

27, 1971).

"Prop. Op. " - Ruling on Propriety of Considering a

Metropolitan Remedy to Accomplish Desegre

gation of the Public Schools of the City

of Detroit (March 24, 1972).

"D-0 Op. " - Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law on

Detroit-only Plans of Desegregation (March 28,1972).

VW-

."Metro Op." - Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

in Support of Ruling on Desegregation

Area and Development of Plans (June 14, 1972).

"Metro Order"- Ruling on Desegregation Area and Order

for Development of Plan of Desegregation

(June 14, 1972).

To some extent in the Statement of Facts, the district

court's findings are quoted verbatim with supporting record

references contained in brackets.

i x

(

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO. 72-8002

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees

vs.

WILLIAM J. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Michigan,

Southern Division

OPENING BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

ISSUES PRESENTED

Defendants-appellants1 challenges to the district

court's orders present the following issues for resolution

by this Court:

1. Whether the district court's findings that segre

gation of black from white children in Detroit public

schools results, in substantial part, from racially

discriminatory acts and omissions by state and local

school authorities, are supported by substantial evi

dence.

2. Whether the district court erred in finding

that the remedy for the state-imposed segregation of

black students, if confined to Detroit proper in the

face of reasonable and more effective alternatives,

would be constitutionally inadequate to eradicate the

pattern of state-imposed segregation and its effects,

root and branch.

3. Whether the state's delegation of responsibility

for operation of the state system of public education to

various subordinate entities limits the equitable powers

and duties of a federal district court in fully remedying

unconstitutional, state-imposed school segregation.

Additionally, this Court, by Order of July 24, 1972,

has presented the following questions:

1. Does Section 803 of the Education Amendments of

1972, Pub. L. No. 92-318 apply to Metropolitan transporta

tion orders which have been or may be entered by the District

Court in this case?

-2-

2. If Section 803 does apply, is it constitutional?

3. What is the precise legal status under State

law of local school districts and boards of education

vis-a-vis the State of Michigan?

4. Whether the expenditures required by the District

Court to be made in this case at State expense are autho

rized by current Acts of the Legislature of Michigan now

in effect.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Introduction

Two years ago, almost to the day, this case began

as a challenge to the State of Michigan's then most

recent direct imposition of school segregation in Detroit.

Exercising the State's plenary power over schools, the

legislature had adopted Act 48, which manipulated school

attendance areas, mandated specific pupil assignment

policies, and substituted (through a boundary commission

appointed by defendant Milliken) racially segregated region

al sub-districts for integrated ones. Its immediate effect

was to nullify the first significant steps toward high

school desegregation taken by the Detroit Board on April 7,

1970. Fully implemented, as to its pupil assignment criteria,

the Act would have preserved and reinforced the pattern of

Detroit school segregation which, it was alleged, had been

brought about by the policies and practices of the State

acting both centrally and through its instrumentalities.

Portions of Act 4b were voided by this Court in

its ruling of October 13, 1970 (433 F.2d b97).

After additional, largely preliminary hearings and

appeals the parties undertook in the court below, begin

ning on April 6, 1971 and continuing for 41 trial days,

a painstaking inquiry into the factors and agencies

responsible for the patent racial identifiability of most

Detroit schools.

As to pupil assignment practices the court found, in

brief, that sustained and systematic state action at all

levels was responsible for school segregation within

Detroit, and that by equally effective practices the

Detroit system and its suburban neighbors had been rendered

racially identifiable in the practical and legal senses.

No single school authority act effected racial separation

as totally and efficiently as the pre-Brown laws of the

South, but a variety of administrative practices combined

effectively with several statutory policies to produce

substantially similar results. In addition, all was done

that needed to be done--including active participation in

housing discrimination and massive segregatory practices of

school construction and site location throughout the metro

politan area--in order to insure that the extreme residen

tial racial segregation which characterizes the Detroit

-5-

community would be reflected in its educational systems.

And where residential segregation--itself the product of

comprehensive public (including school authority) and

quasi-public racial discrimination--proved inadequate

to the task, as in racially changing neighborhoods, still

other supplements, such as the creation of optional

attendance areas, transfer policies, and manipulation of

school attendance zones, feeder patterns and grade struc

tures, were added.

Querying whether a constitutionally adequate plan of

desegregation could be limited to Detroit proper, the

court directed that metropolitan alternatives also be

developed for consideration. Based on the law and evidence

the court's view, which is now the primary controversy here,

was that the constitutional responsibility for remedying

illegal segregation rests ultimately with the State acting

centrally and through its instrumentalities, and moreover,

that the obligation is particularly direct and immediate

here in view of Lansing's sustained and effective partici

pation in the violation.

Widely ranging proposals were duly presented by the

1/

parties (save only the surburban intervenors ) and con-

17 The suburban intervenors, declining the court's(cont'd next page)

-6-

sidered below. As reflected in its opinions of March

24, March 2b, and June 14, 1972, the court below con

cluded, in essence, that Detroit-only desegregation

would be constitutionally defective as failing to dis

establish the racial identifiability of Detroit schools;

that considering the role and responsibility of the State,

and the geographical scope of the violation, there could

be no constitutional impediment to metropolitan school

desegregation; and that considerations of soundness and

practicability supported--indeed mandated--that approach.

Thereafter this Court stayed the non-planning aspects

of the district court's order of June 14 and July 11, 1972,

and by its orders of July 20 and 24 took jurisdiction of

2 /

this appeal on the merits.

In our view, the district court was correct in holding:

(1) That the public schools of Detroit are un

constitutionally racially segregated;

1 / (cont'd)

request for assistance in developing a metropolitan

remedy, offered instead to prove the undesirability of

school desegregation. The district court declined that gam

bit, essentially on the ground that remedies for official

school segregation are constitutionally mandated.

2/ The detailed procedural history of this litigation

is set forth in Appendix A, attached hereto.

-7-

(2) that practically as well as legally, providing

constitutional public education has been and

is the responsibility of the State of Michigan;

and that,

(3) a school desegregation plan limited to Detroit

proper would be constitutionally and educationally

inadequate.

It may be premature to characterize here the positions

of the other participants in this appeal. We deem it

significant however, that no challenge is made to the

educational practicability and soundness--the ultimate

rightness--of the metropolitan framework set forth in the

district court's opinion of June 14, 1972. Rather, we are

disputing here whether the remedial powers of the federal

courts are commensurate with the magnitude of constitutional

wrongs.

B. Statement of Facts

1. The Violation--State-Imposed Pupil Segregation

This case deals with a long history of state action

resulting in massive school segregation. In 1960-61, of

3/

251 Detroit regular public schools, 171 had student en

rollments 907> or more one race (71 black, 100 white); 65.87o

3 / By "regular" schools we refer to schools with

designated attendance areas.

-8-

of the 126,278 black students were assigned to the vir

tually all black schools. In 1970-71 (the school year in

progress when the trial on the merits began), of 282 Detroit

4/

regular public schools, 202 had student enrollments 907.

or more one race (133 black, 69 white); 74.97. of the

177.079 black students were assigned to these virtually all

black schools. In 1960-61, 126,278 (45.97.) of the 275,021

pupils in Detroit public schools were black; in 1970-71,

177.079 (63.87.) of the 277,578 pupils were black. (A. IXa333,345

(P.X. 128A-B),IXa357 (P.X. 129),IXa467 (P.X. 150),IXa469

(P.X. 152A),IVa72-73).

5/

In the metropolitan areas surrounding the Detroit pub

lic schools the pattern of segregation and containment was

6/

primarily expressed in this record by effective exclusion

of black children from a rapidly expanding set of new

schools: between 1950 and 1969 over 400,00 pupil spaces

4/ In addition, the Detroit Board operated 23 various

non-attendance-area schools enrolling 8,130 students (of

whom 5,386 were black) from throughout the district and the

metropolitan area in 1970-71. (P.X. 100J at p. 127). The

Board also had 4,146 students, of whom 1,798 were black,

enrolled in special adult programs. (P.X. 100J at p. 6).

5 / Hamtramck(28.7 7> black) and Highland Park (85.17, black)

are surrounded by the Detroit school district. (P.M. 13).

6 / There are also historic areas of black containment

which are located in Ecorse, River Rouge, Inkster, West

land, Old Carver School District (Ferndale and Oak Park),

(cont'd on next page)

-9-

were added in school districts now serving less than 2%

black student bodies. (A (P.M. 14, 15)). By 1970

these suburban areas assigned a student population of

625,746 pupils, 620,272 (99.13%) of whom were white, to

V

schools.

Corresponding the massive pupil segregation is the

clear racial pattern in the allocation of faculty to

schools: throughout the metropolitan area black teachers

are disproportionately assigned to schools with predomi

nantly black student bodies and white teachers are dispro

portionately assigned to schools with predominantly white

student bodies. (See pages 40 - 48, infra).

The facts disclose: two sets of schools, one virtually

all black, another virtually all white extending through

out the area surrounding the geographical limits of the

Detroit school district. Some 60 hearing days of trial

proof, 8,000 pages of transcript, hundreds of exhibits con

stituting thousands of pages of written material and over

100 maps and overlays demonstrate the action and inaction

£>/ (cont'd)

and Pontiac. As in Detroit, the black children in

these districts also remained substantially segregated in

1970-71. (See P.M. 13).

]_/ Exclusive of the school populations of the districts

named in notes 5 and 6, supra.

-10-

on the part of school authorities in coordinate step with

other governmental and private discrimination which had

the natural and foreseeable effect of segregating black

and white children in their respective schools. To under

stand how the present massive segregation of school

children came about is to examine, as the court did below,

the history of discriminatory state action which accom

plished the present condition.

We shall briefly attempt to summarize this history

as it is reflected in the record. At the outset, however,

two points must be kept in mind. First, although the proof

reaches back several decades it deals in great detail only

with the period from 1959 and 1960 to date, the only period

for which racial enrollment statistics and attendance zone

and school location maps and data were available. Second,

this case was filed by black and white school children and

their parents and the Detroit Branch of the NAACP to dis

establish the racial identity of Detroit public schools, to

substitute just schools for black and white schools. So-

called housing segregation proof was introduced by plain

tiffs solely to show exactly the interdependence of the

actions of various governmental authorities and those of

school authorities in creating and maintaining school segre-

-11-

8/

gation. The case was intended to be, and remains, a

narrow vehicle to disestablish the pattern of racial

identification of hundreds of Detroit public schools.

From its inception the case focused primarily on the

Detroit public schools, where over 150,000 black school

children are now assigned to schools identified as black

by state action. Yet, almost from the first day of the

trial on the merits, in explaining how these black schools

were created and maintained, the proof of the pattern of

state action effecting school segregation, both its scope

and causes, extended beyond the geographical limits of

Detroit. And in considering remedy, the practical reali

ties making impossible the substitution of just schools,

for the black schools and the white schools within the con

fines of the geographic limits of the Detroit school dis

Htrict, became evident.

8/ Proof of housing segregation, as is usually the case,

was introduced by plaintiffs for the precise purpose of

showing the role of school authorities. Otherwise, "housing

segregation" is the typical urban school area's first line

of defense to a charge of school segregation. (Compare note

27 , infra).

_y/ The proof of segregation resulting from state action

did extend throughout the metropolitan area. Although, as

the district courts notes, specific inquiry into each divi

sion of the State education system (and each suburban dis

trict) was not made, the State defendants, the chief State

school officer, the State Board of Education which is

(cont'd on next page)

-12-

At trial plaintiffs presented extensive evidence--

10/ 11/ 12/

demonstrative and documentary exhibits, and factual

13/

and expert testimony--establishing the fact that his

torically and at present black citizens have been pur

posefully contained in separate and distinct areas within

the inner City and largely excluded from the outer areas

of the City and from the Suburbs, and that the patterns

and practices persist. (P.X. 184, 2, 16A-D, 136A-C (cen-

9/ (cont'd)

charged with general supervision of public education,

the chief State legal officer and the State's chief execu

tive, were defendants throughout. Evidence was taken as to

the State's policy affecting Detroit as well as suburban

districts with respect to school construction, merger of

districts, pupil assignment across district boundaries for

the purpose of segregation, and disparity of bonding and

transportation funding as between the Detroit and suburban

districts.

10/ P.X. 16A-D (1940-70 census maps), 23 (public housing

map), 48 (racial covenant map) and 184 (tri-county 1970 cen

sus map) .

11/ P.X. 15, 17, 18A-B, 19, 21, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 29

31, 32, 37, 38, 56

122 and 123 •

12/ 1 Tr. 131

seq 2 Tr. 232 et

seq 5 Tr. 591 et

seq . ; 6 Tr. 630 et

seq .; 6 Tr. 686 et

11/ 1 Tr. 131

et seq. ; 6 Tr. 686

56A-B (A.IXa306 ) ,

et seq.; 2 Tr. 185

seq.; 3 Tr. 398 et

seq.; 5 Tr. 608 et

seq.; 6 Tr. 636 et

seq.; 7 Tr. 720 et

et seq.; 3 Tr. 322

et seq.; 7 Tr. 754

57, 58, 59, 60, 61A-B,

et seq.; 2 Tr. 200 et

seq.; 5 Tr. 522 et

seq.; 5 Tr. 617 et

seq.; 6 Tr. 665 et

seq.

et seq.; 4 Tr. 427

et seq.

-13-

sus maps), 48 (map of racial covenants); 1 Tr. 144 et

seq.; 5 Tr. 522 et seq. ; 6 Tr. 686 et seq.; 7 Tr. 720 et

seq. ; 7 Tr. 766 et seq. ; 5 Tr. 591 et seq.; 5 Tr. 608 et

seq. ; 5 Tr. 617 et seq. ; 6 Tr. 630 et seq.; 6 Tr. 636 et

seq. ; 6 Tr. 655 et seq. ) • The pervasive, long;-standing

residential segregation is the direct result of discrimi

natory action and inaction at all levels of government-

federal, state and local, including state and local school

authorities. This extensive proof stands unrebutted in

the record and uncontradicted by any defendant; it was

properly conceded by counsel for the Detroit Board to be

a "tale of horror... degradation and dehumanization." (5 Tr.

607 ; also see A. Ila 99; 4 Tr. 505; 6 Tr. 672, 680-81).

The defendant school authorities not only had full

14/

knowledge of this situation, they became active partners

14/ The Detroit Board's chief school planner and prin

cipal fact witness, Merle Henrickson, was employed by the

Detroit City Plan Commission (from 1943 until his employ

ment with the Board in 1959) and worked on the master plan

which, with modifications, is still in effect and included

generally existing and proposed school locations. (A.IVal09-13).

The Detroit Board acts jointly with city planning officials,

public housing authorities, park commission authorities and

federal agencies in the acquisition and sale of land and

location and construction of schools. (A.IXa405 (P.X. 147),

IXa475 (P.X. 148)lXa475 (P.X. 167); P.X. 19 at p. 37; A.IVall3-16

IIIa60“61). The State Board and the Michigan Civil Rights

Commission jointly directed, in 1966, that school authorities,

in their site location, construction and pupil assignment

policies, avoid incorporation of housing segregation into

(cont'd on next page)

-14-

• •

in the entire process. The Detroit Board, with the

sanction of the State Board and support of the State

bonding authority, actively accommodated the housing

discrimination and built upon and advantaged itself of

the segregated residential patterns to create, maintain,

magnify and perpetuate racial segregation in the public

schools. For example, as the major area of black con

tainment expanded to the west (after a decision by white

realtors to open the area to blacks) in a pattern of

neighborhood succession from Woodward Ave. to Livernois

Ave. to Greenfield (P.X. 2, 184, 16B-D, 136A-C; A.Ha21-22,71;3Tr.

364 - 70 ), school attendance boundaries were either

altered, made optional zones, or maintained in a general

north-south direction and, often, in an overcrowded con-

24-29

dition (see pages 16-18.infra). (P.X. 109A-Q, 110A-S,

137A-C).

Additionally, many schools were built for public housing

projects designated "black" or "white"; sometimes these

schools were located on the site of the public housing

14/ (cont'd)

the schools (A. IXa281 (P.X. 174)); and the

State Board, in 1970, re-emphasized this position in its

"School Plant Planning Handbook" (A. (P.X. 70)).

-15-

15,/

project. (A.IXa405 (P.X. 147), IXa437 (P.X. 148);

P.X. 19 at pp. 32, 37; P.X. 149; A.IIIal82 The schools

constructed to accommodate the housing projects which

were built for black occupancy remain virtually all

black, as do the housing projects. (P.X. 149).

Identifiably "white" schools were often constructed

and maintained on lands with covenant restrictions prohi

biting Negro use or occupancy (A.IXa493 (P.X. 172), P.X.

172A-Z); and in at least one instance, in 1954, a racial

covenant was continued pursuant to a special agreement

between the seller and the purchaser Detroit Board. (A.IXa495

(P.X. 172W)).

Just when racial discrimination in Detroit’s public

schools began is not known, but the record establishes its

existence throughout the 1950s and its continuation to the

time of trial.

As noted above, "/_d/uring the decade beginning in 1950

the Board created and maintained optional attendance zones

in neighborhoods undergoing racial transition /by permission

15/ Indicative of the Board's color consciousness is

the reference in the Superintendent's Minutes of November 2,

1953, to using a "colored church" to relieve overcrowding

caused by black housing projects. (A IXa422 (P.X. 147);

A. IIIal84“85).

-16-

and designation of the white real estate industry/ and

between high school attendance areas of opposite pre

dominant racial compositions. /A.IVa96-101, IIa261 62,

IIa267-314,Ila 11-14 _/. In 1959 there were 8 basic

optional attendance areas _/P.X. 109A (1959-60 overlay)/

16/ _

affecting 21 schools. j_P.X. 155A at p. 44; A . m a36,37

_/." (Mem. Op., A. Ia20 ). The certain "effect

of these optional zones was to allow white youngsters to

17/ _

escape identifiably 'black' schools /A. IIa311-14,

IIIa37, IVa97-101; A.IXa373 (P.X. 132); P.X. 109A-L, 78A-L

16/ "Optional attendance areas provided pupils living

within certain elementary a_reas a choi.ce of attendance at

one of two high schools. /A. IVa96_/. In addition there

was at least one optional area either created or existing

in 1960 between two junior high schools of opposite pre

dominant racial components. /_A.IIa311 -14,II178_/ . All of

the high school optional areas, except two, were in neigh

borhoods undergoing racial transition (from white to black)

during the 1950s. The two exceptions were: (1) the option

between Southwestern (61.67<> black in 1960) and Western (15.37,

black); (2) the option between Denby (0% black) and South

eastern (30.9% black). /AJXa333 (P.X. 128Aj>/. With the

exception of the Denby-Southeastern option (just noted) all

of the options were between high schools of opposite pre

dominant racial compositions. The Southwestern-Western and

Denby-Southeas tern optional ajreas are all white on the 1950,

1960 and 1970 census maps. /_P.X. 136A-C, 109A/. Both

Southwestern and Southeastern, however, had substantial

/black/ pupil populations, and the optjlon allowed whites to

escape integration /AJIa298-311 _/." (Mem. Op., A.ia201

17/ "There had also_been an optional zone (eliminated

between 1956 and 1959) / A. IVa75 _/ created /in the words of

Board counsel agreed to by Mr. Henrickson/ 'in an attempt.._.

to separate Jews and Gentiles within the system' /AJIIa219/,

the effect of which was that Jewish youngsters went to Mum-

(cont'd on next page)

-17-

136B, 136C/." (Mem. Op., A Ia202 ). "Although many of

18/

these optional areas had served their purpose by 1960

due to the fact that most of the areas had become predomi

nantly black _/P.X. 136B/, one optional area (Southwestern-

Western, affecting Wilson Junior High graduates) continued

until the _/1970-7JL/ school year (and /continues to effect/

11th and 12th grade white youngsters who elected to escape

from predominantly black Southwestern to predominantly white

19/ _

Western High School) /A IVa99-100;A.IXa73 (P.X. 132);

A.IXa384 (P.X. 1382/. Mr. Henrickson, the Board's general

fact witness, who was employed in 1959 to, inter alia,

eliminate optional areas, noted in 1967 that: 'In operation

Western appears to be still the school to which white stu

dents escape from predominantly Negro surrounding schools.'

/A.IVa77- 78;A. IXa398 (P.X. 13827." (Mem. Op., A.ia202 ).

Yet, the option continued in effect until the 1970-71

school year. "The effect of eliminating this optional area

17/ (cont'd)

_ ford High School and Gentile youngsters went to

Cooley /A. IVa74_/." (Mem. Op., A. Ia202 ). (See also

A. Xa31-32 ).

18/ Mr. Henrickson admitted, however, that even in 1959

some of the optional areas "can be said to have frustrated

integration and continued over the decade." (A.iVa96~97 )•

19/ The Board had eliminated the other optional areas

by 1965 (P.X. 109G). With regard to two such areas (Sherrill

and Winterhalter-McKerrow) the effect by 1960 was that black

(cont'd on next page)

-18-

(which affected only 10th graders for the 1970-71 school

year) was to decrease Southwestern from 86.77o black in

20/ _ _

1969 to 74.3% black in 1970 /A.IXa345 (P.X. 128B2/."

(Mem. Op., A.Ia202 ).

Working hand-in-hand with the optional zoning prac

tices for segregation results were the Board's transporta

tion practices. "The Board, in operation of its transpor

tation to relieve overcrowding policy, has admittedly bused

black pupils past or away from closer white schools with

available space to black schools. /_A.IVa86-88,91-93, 203-08,

214 18; IllalS-31, 145-46; Ila 318-29 J . This practice

has continued in several instances in recent years despite

the Board's avowed policy, adopted in 1967, to utilize

transportation to increase integration. _/A.Hal44-68,

19/ (cont'd)

students were electing to attend white high schools.

In both instances the Board initially proposed to eliminate

the optional area by including it (in the usual segregatory

manner) in the black high school zone. Both proposals

resulted in community opposition and one resulted in the

Sherrill School lawsuit. (A.lIIal47-48).

20/ The Board failed to present any valid, not to men

tion compelling, justification for its optional attendance

policy and practice. Dr. Foster, plaintiffs education ex

pert, found no valid administrative reasons for creation

or maintenance of any of the optional areas. (A.IIa 267-318).

The Board, through Mr. Henrickson, spent much time talking

about the relative capacities of the various high schools

involved in options. Even if there were capacity problems,

this is an insufficient administrative justification, fox;

(cont'd on next page)

-19-

IVa84 - 85, IIa23, IIIa25 - 30, Xa39 - 40/."

(Mem. Op., A.Ia202 ). Even when the Board, prior

to 1962, bused black pupils to white schools, it did so

under its "intact busing" (busing by grade, class and

teacher) practice which kept black youngsters segregated

21/

in the receiving schools. (8/28/70 Tr. 140-41; P.X.

3 at 62; A.IIIal8-20).

"With one exception (necessitated by the burning of

a white school), defendant Board has never bused white

20/ (cont'd)

it is clear that capacity problems are more easily

and predictably eliminated by establishment of firm atten

dance boundaries.

21/ The secretary of the Citizens' Association for

Better Schools presented one particularly demeaning exam

ple of "intact busing" to the EEO Committee in 1960: "the

fourth grade at the Thirkell School was bussed because of

the overcrowded condition of the school... These children

do not eat in the lunchroom at the same time that the

children in the White _/name of the receiving schooJL/ school

do. They are not integrated at all in the White school...

This is now the beginning of the third year for them and

for three years they have been a segregated part of this

school. Now the association has teachers telling them that,

in instances where white children in the school misbehave,

these children are told, 'Now, if you don't behave, we're

going to send you over there with those little colored kids

from Thirkell school.'" (P.X. 105 at pp. 465-66; App. B,

attached hereto, at pp. 4b-5b).

-20-

22/ _

children to predominantly black schools /A.IVa85,

IIa264_/." (Mem. Op., A. Ia202 ). And the Board has

persisted in refusing to bus white pupils to black

schools "despite the enormous amount of space avail

able in inner-city schools _/A.lVa232-36; P.X. 181.7 .

/In 1970-7// J_t/here were 22,961 vacant seats in schools

90% or more black /A.iXa372 (P.X. 131//." (Mem. Op.,

A. Ia202 ).

In 1962 the Detroit Board-appointed Citizens Advisory

Committee on Equal Educational Opportunities concluded:

Numerous public schools in Detroit are

presently segregated by race. The alle

gation that purposeful administrative

devices have at times been used to per

petuate segregation in some schools is

clearly substantiated. It is necessary

that the Board and its administration

intensify their recent efforts to desegre

gate the public schools.

22/ One of the most flagrant discriminatory uses of

busing occurred in the transportation, from 1955-1962,

of black junior high pupils from the black Jeffries public

housing project to black Hutchins Junior High in another

high school constellation, rather than allow them to walk

across the street to the majority white Jefferson Junior

High. Although Jefferson Junior High was at capacity, the

Board could have assigned white students from the Tilden

Elementary area in the northernmost part of the Jefferson

zone (and much closer to Hutchins than to the Jeffries

project) to Hutchins, thereby making available space for

the Jeffries project youngsters at Jefferson. (P.X. 109M;

A. IIa318-29; IVa87~88, 214-18).

-21-

• •

(P.X. 3 at p. 61, excerpts from which are.attached hereto

as Appendix C} p. 2c). This finding and recommendation

remained mere words on paper, however, for, as we shall

show, the practices continued virtually unabated.

As the more patently discriminatory techniques of

dual zoning and busing for segregation were beginning to

be eliminated, the Board adopted an open enrollment policy

which permitted any pupil to transfer to any school in the

system with available space. (8/27/70 Tr. 50-52; A.IIIa32-35,IVa

237-38;22Tr.2519-20)On September 18, 1964, Judge Kaess

entered "Interim Findings" in Sherrill School Parents

Committee, et al., v. The Board of Educ. of the School Dis-

23/

trict of the City of Detroit, C.A. No. 22092 (E.D. Mich.),

concluding, inter alia, that:

The present "Open School" program does

not appear to be achieving substantial

student integration in the Detroit

School system presently or within the

foreseeable future. Accordingly, the

23/ The Sherrill School lawsuit was filed as a result

of the discriminatory elimination of an optional zone (see

note 19, supra) and, although the complaint challenged the

alleged existence of a dual school system, the suit was

never prosecuted.

-22-

Board should commit itself to

devise and propose other methods of

speeding up the racial integration

of students. The goal should be

the achievement of substantial

student integration in all High

Schools and Junior High Schools

by the beginning of the February,

1965 term. 24/

(A. IXa303 (P.X. 6)). The Board, with one member dissenting,

expressed complete agreement with these findings on April

20, 1965. (P.X. 6A). Yet it was not until September,

1966, that the open enrollment policy was modified to re

quire that any transfer thereunder have a favorable effect

upon integration at the receiving school. (A.iva237 ; A.ixa395

(P.X. 138)). Although some black pupils had elected to go

to predominantly white schools, "the greater effect of the

policy to that date _/_September, 196_6/ had been to draw

white students away from inner city schools." (A.IXa397

(P.X. 138); A.IVa237-38). Even under the post-1966 policy

the favorable effect on integration has been negligible,

with some black students continuing to elect predominantly

24/ The record of junior and senior high segregation

from 1965 to date clearly indicates the continued and

obviously deliberate maintainance of segregation. Whether

the delay from 1965 to April 7, 1970 for the first small

beginning of desegregation was the result of fear of

community reprisal is not clear. In view of the violent

public and legislative reaction to the April 7 attempt to

begin desegregation this continued discrimination may be

explained, but is in no way constitutionally or morally justi

fied.

-23-

white schools, but almost no white students opting for

predominantly black schools. (A.IIIa90-91,239-40;IIa264).

The policy continues to focus on the receiving school and

permits white students to transfer from black schools to

schools which are less black. (A.IIa264, 20 Tr.2190-92).

Furthermore, pupil transfer requests for explicit racial

reasons have been and continue to be regularly granted.

(A.IIIa63-76, ; (P.X. 168); A.IVa72-78;

A. IXa387, IXa398 (P.X. 138)).

The Board has created and altered attendance zones,

grade structures and feeder school patterns in a manner

obviously designed to exclude blacks from white schools

and whites from black schools. (Mem. Op., A.Ia202-03;

A.IIa318-IIIal3,IIIa39-40 ). "The Board admits at least

one instance /Higginbotham/ where it purposefully and inten

tionally built and maintained a school and its attendance

zone to contain black students _/A.IVa248,IIIal45-49,IIa339-42V

(Mem. Op., A.Ia203 ). The segregation of the Higginbotham

school is an example directly linked to racial discrimina-

25/

tion in housing : the school's boundaries were built upon

25/ The Higginbotham community had been built up by

temporary war housing (P.X. 19, at p. 71), designated for

black occupancy, and extended beyond the City limits into

Oakland county and the old, almost all-black Carver School

District. (P.X. 184; A.Xa 8-9 ,Xa38 39 ). The small

(cont'd on next page)

-24-

actual physical barriers erected by neighboring whites

26/

intent on keeping blacks out.

Numerous examples of similar zoning and feeder pattern

gerrymandering were presented to the district court. The

27/

Center (administrative) District is a classical example. * 8

25/ (cont'd)

Carver school district lacked high school facilities.

The state defendants and the Detroit Board accommodated these

students by busing them past "white" schools to "black"

schools in the inner city. (A.IIal93~94; Xa8-9,38-39;

8 Tr. 885; P.X. 78A). These black students were refused by

suburban districts and were, therefore, for the purpose

of maintaining the segregation in the suburbs, bussed across

school district boundaries to segregated black schools in

Detroit. The Carver school district finally was split and

merged into the Ferndale School District and Oak Park School

District. (A. Xa8-9 ; P.X. 184 (census map); A.iXa556 (P.X.

185)). In these districts at the elementary level in the

1968-69 school year, the students from this still black

residential pocket (P.X. 184 (census map)) were assigned

to two virtually all black schools. (A.iXa556 (P.X. 185)).

26/ One witness who described the general pattern of

containment as being "just as effective a barrier as if a

wall were built in the community" (A.I Tr.163), then went

on to describe the Higginbotham area in the 8 Mile-Wyoming

area where a builder, who had title to property adjacent to

the black residences, "actually put up a cement wall, brick,

mortar and brick wall, which for years was a symbol in

/Detroit/ of the way in which the Negro was an undesired

neighbor." (A. I Tr. 163).

27/ An assistant superintendent, Charles Wells, testi

fied from the minutes of the EEO Committee (P.X. 105 at p.

478) with respect to a letter presented to the Committee

by the Citizens' Association for Better Schools (of which

Mr. Wells was a member) at an EEO meeting in 1960 attended

by Mr. Wells. After outlining the hopes and dreams of

equal educational opportunities of Detroit's black citizens,

particularly the hopes inspired by the favorable millage

vote in 1959, the Association stated:

(cont'd on next page)

-25-

A home owners association presented evidence of another

example to the EEO committee in 1960: the school zone

boundary changes in their area "were exact to the street,

to include the total Negro population to the east in the

27/ (cont'dj^ _

Their /black people/ first disillusionment

occurred only a few months, but yet a few weeks

after the passage of the millage-they were

rewarded with the creation of the present

Center District. In effect this District, with

a few minor exceptions, created a segregated

school system. It accomplished with a few

marks of the crayon on the map, the return of

the Negro child from the few instances of an

integrated school exposure, to the traditional

predominantly uniracial school system to

which he had formerly been accustomed in the

City of Detroit.../Protestations/ resulted

in only rationalizations concerning segre

gated housing patterns, and denials of any

attempts to segregate. When it was pointed

out that regardless of motivation, that segre

gation was the result of their boundary changes,

little compromise was effected, except in one

or two instances, where opposition leadership

was most vocal and aggressive.

(A.IIIal41-42) . These charges, joined in by Mr. Wells, were

supported with statistical data showing the disproportionate

size, inferior iacilities and unequal resources relegated

to the Center District. (See generally A.IIIal40-45) Jhe

Center District exemplified "a policy of containment of

minority groups within specified boundaries.jj (A.IIIal42-43) .

Its boundary line was described as "looking/ like the

coastline of the Eastern United States where the Negro popu

lation is on one side and the white population on the other."

(A.IIIal47 ).

-26-

reassignment to Central High School." (P.X. 105 at p.

425, Appendix B, attached hereto, at p. 3b). To the EEO

committee these boundary changes "appear/ed/ to be a

result of racial discrimination," a proposition with

which the representatives of the home owners association

agreed, "not only in their area but in other areas of

the city." (P.X. 105 at pp. 426-27, App. B at p. 3b).

As long ago as 1967 Mr. Henrickson pointed out to

the Board various obvious examples (e.g., Burton-Franklin

Area; Wilson-McMillan Junior High area) where boundary lines

separated white and black school zones which could easily

be integrated by simple boundary line revisions. (A.IVal04-09;

accord, A.IIa329-32; IIIa51-56).But. the Board declined to act,

although it had changed the Vandenburg-Vernor (A.IIa333-37),

Jackson Junior High(A.IIa345~47),Davidson-White (A.IIIal-4) ,

Parkman (A.IIIa4-7), Sampson(A. Illall-l^and other zone lines

and feeder patterns in a manner which has created and per

petuated racial segregation in the schools in the face of

equally feasible alternatives which would enhance integra

tion. (A.IIIa39 ). And the Board created and maintained

attendance areas such as Hally(A.11342-43) and Northwestern-

28/

Chadsey (A.IIIaS 11) in a patently segregatory manner.

28/ Defendants responded to these and similar examples

generally by pointing out alleged capacity problems and the

(cont'd on next page)

-27-

And even at the time of trial the Board planned on

removing the last predominantly white elementary school

(Ford) from the black Mackenzie high school feeder pattern,

the only justification being that the regional board

created by the state legislature (via Act 4b) so willed.

(A.IVa94 ). Even in two of the 8 minor changes (including

elimination of 3 optional areas) during the past decade

which the Board pointed to as improving integration, sub-

29/

sequent changes negated or modified the meager results.

28/ (cont'd)

desire to maintain "articulated" feeder patterns

which would keep the same students together as they pro

gressed from elementary to junior high, then from junior

high to senior high. These proffered justifications are

unconvincing, if for no other reason because of the incon

sistency of their application. For example, the Board

attempted to justify the removal of the white Parkman ele

mentary from the black Mackenzie High feeder pattern by

pointing out that the receiving white high school (Cody)

was much less overcrowded than Mackenzie. Yet, at the

same time Cooley (predominantely black) was similarly less

overcrowded than nearby white Redford, but the Board made

no change in the feeder patterns. (A.IV93-96). The arti

culated feeder pattern principle has not been, nor is it

now, a valid justification for maintaining or failing to

alleviate segregation. This principle was violated in

feeder patterns such as the Custer in 1959-61 (A.iVa209-ll)

and the Davison in 1969-1970(A - IVa211-14) , which had the

effect of creating and perpetuating segregation. And the

concept was wholly disregarded in the feeder patterns pro

posed in the April / plan. (A,IVa201 -03) .

29/ The two negative changes were the return of black

Custer to the black Central High feeder pattern (A.IVa209-ll,

IV213-14) and the return of black Davison from the white

(cont'd on next page)

-28-

(A.IVa208~13). "Throughout the last decade (and presently)

school attendance zones of opposite racial compositions

have been separated by north-south boundary lines, despite

the Board's awareness (since at least 1962) that drawing

boundary lines in an east-west direction would result in

30/ _

significant integration j_P.X. 105 at p. 450; A.Xa43-55;

11/4/70 Tr. 38; A.IXa201-03; A.IXa393 (P.X. 138); A.IIIa51-567."

(Mem. Op., A.Ia2C3 ). And although the Board was speci

fically aware, since at least 1967, of contiguous atten

dance zones which could be paired or altered to accomplish

integration, it failed to act (A.IVal05-09;A.IXa384 (P.X.

138)) until adoption of the April 7, 1970 Plan which was

promptly snuffed out by the Michigan Legislature.

The most invidious and lasting segregatory device, how

ever, has been defendant school authorities' school site

selection and construction practices which, coordinated

and interrelated as they were with housing segregation, have re

sulted in a brick and mortar dual school system. Between 1940 and

29/ (cont'd)

Osborn feeder pattern to the predominantly black

Pershing feeder pattern. (A.lVa211-14).

30/ With the exception of the April 7 plan, the Detroit

Board "has never made a feeder pattern or zoning change

which placed a predominantly white residential area_into a _

predominantly black school zone or feeder pattern j_k. _/. "

(Mem. Op., A. Ia203 ).

• •

195b the Board constructed 36 new elementary schools and

4 new high schools, and additions to 55 elementary schools,

1 junior high school and 3 high schools, for a total addi

tional capacity sufficient to house 69,000 students. (A.IVal09-10

P.X. 101 at p. 233). The new school construction during

this period was located largely in accordance with general

site designations set forth in the Detroit Master Plan of

1946, which was developed by the City Plan Commission in

conjunction with school authorities. (A.IVallO-l1,113-14,.

Most, if not all, of this construction was to accommodate

the out-migration of whites moving to all-white residential

areas in the northwest and northeast areas of the City.

No doubt, this construction had a corresponding magnet

effect, attracting even more whites (blacks not being

allowed to live in these areas) away from the inner city.

In 195b, the Board-appointed Citizens Advisory Commi

ttee on School Needs pointed up inadequacies in school plant

facilities, particularly the failure to build new schools

and upgrade deteriorating facilities in and near the areas

of black concentration. (P.X. 101). In 1959 the Board

designated a $90 million dollar building program; $30 million

came out of the millage package and the remaining $60 million

from the first bond issue the Board had ever placed before

the public. (A.Xa24-25 ). The 1959 building program was

-30

specified in a "priority list" of projects; this list

was transmitted by the school authorities to the City Plan

Commission which resulted in joint conferences between

these two agencies and other city agencies, such as the

Department of Parks and Recreation, for the purpose of

determining site locations (A.IVall4 ). Many of the pro

posed attendance areas were designated in iy59 and specific

site locations were thus determined within the confines

of the established attendance areas; by iy62 all atten

dance areas and site expansions were designated for the

school construction proposals on the 1959 priority list

and published in The Price of Excellence (P.X. Ilk). (A.IVa

226-27). Almost all of these attendance areas were drawn

in such a manner that the Board knew or should have known

that the schools, when constructed, would open as segre-

31/

gated schools.

The segregatory purpose and effect of the site selec

tion and construction practices, coupled with the attendant

31/ As previously noted, much of plaintiffs' proof

consisted of demonstrative presentation. For example, the

school site location and construction practices were demon

strated to the district court in part by comparing over

lays reflecting site locations and construction (P.X. 153,

153A-B) with the appropriate federal census data as reflected

on maps color-coded to the racial composition of the City's

population. (P.X. 136 A-C).

-31-

zoning practices, is demonstrated in considerable detail

in plaintiffs' proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions

of Law (at pp. 23-28) submitted to the court below and

which defendants have included in the printed appendix,

A. Ial70-77.

In addition to the 84 projects undertaken pursuant to

the 1959 Construction Program (see P.X. 75), the Board

has, during the last decade, undertaken additional con

struction with its normal millage authority (recently

increased to 5% to equalize Detroit's capital outlay autho

rity with that of the rest of the state). (See P.X. 77).

Defendants' Exhibit NN (A.IXa571 ) reflects that the Board

has completed construction of and additions to 91 schools

since 1959. According to defendants' own exhibit (NN), 48

of these schools were to serve areas which were over 807.

black in pupil population when the construction was autho

rized, all of which opened over 807. black and remain so; 14

schools were in are s over 807. white (by the Board's own

estimates) when authorized, opened over 807, white and have

remained so. Plaintiffs' Exhibit 70 shows the construction

of 63 new schools since 1960: 44 of these schools opened

over 807, black in student enrollment, and 9 opened less

than 207, black. This new school construction is depicted on

overlays (P.X. 153, 153A and 153B); when the overlays are

compared to the 1960 and 1970 census maps (P.X.

-32-

136B and 136C) and the percentage black when each school

opened (P.X. 70), it appears beyond peradventure that

the Board, with few exceptions, knowingly constructed a

dual school system (A.IIIa40-51,IVall6-18).

In 1966 the defendant State Board of Education and

the Michigan Civil Rights Commission issued a Joint Policy

Statement on Equality of Educational Opportunity (A.IXa281

(P.X. 174)), requiring that:

Local school boards must consider the factor of

racial balance along with other educational

considerations in making decisions about selec

tion of new school sites, expansion of present

facilities... Each of these situations presents

an opportunity for integration.

Defendant State Board's "School Plant Planning Handbook"

(A. (P.X. 70)) requires that:

Care in site location must be taken if a serious

transportation problem exists or if housing pat

terns in an area would result in a school largely

segregated on racial, ethnic, or socio-economic

lines.

Yet the Detroit Board has paid little, if any, heed to the

obvious truth of these statements and guidelines, and the

"State defendants have similarly failed to take any action

32/

to effectuate these policies." (Mem. Op., A.Ia204;A.IVall8-19).

32/ Since 1959 the Board, with the obvious knowledge

that small schools "defeat the intended objective of large

service areas with heterogeneous social and racial composi

tion" (A.IXa391 (P.X. 138); A. IVa257»38)'has constructed

at least 13 small primary schools with capacities of from

(cont'd on next page)

33-

Defendants' "Exhibit NN /A.IXa571_/ reflects construction

(new or additional) at 14 schools which opened for use in

1970-71; of these 14 schools, 11 opened over 90% black and

1 opened less than 107, black." (Mem. Op., A.ia204 )•

School construction costing $9,222,000 was scheduled to

open in 19/1 at Northwestern High School (99.97. black),

and new construction was similarly scheduled at Brooks

33/

Junior High (1.5% black) at a cost of $2,500,000. (A.

(P.X. 151)).

The segregated construction pattern within the Detroit

school system was significantly influenced by the State's

discriminatory scheme of allocating State funds for pupil

transportation. State aid for pupil transportation is

provided to bus all students who live over 1\ miles from

their assigned schools, but, by virtue of State law, simi-

32/ (cont'd) _ _

300 to 400 pupils _/A.IVa236-37./ •" (Mem. Op., A.Ia204).

This practice negated opportunities to integrate and furthered

the racially dual construction pattern. Construction of

such primary units usually adjacent to an existing segre

gated school mandates a small enough attendance boundary

to keep the boundary within the area of black residence and

therefore segregated. Obviously, a larger school requires

a larger attendance area making it more likely that black

and white students would be included in the school. In most

cases the small primary unit retained the boundary of the

already segregated elementary school.

33/ "The construction at Brooks Junior High plays a

dual segregatory role: not only is the construction segre

gated, it will result in a feeder pattern change which will

(cont'd on next page)

-34-

• •

larly situated students in Detroit and most other city

school districts (whose boundaries are coterminus with

those of their respective cities) in Michigan are denied

any portion of the State transportation fund ($29,000,000)

34/

for such regular pupil busing. (A. Ilia 93 95, 223).

The effect for Detroit and segregation was this: rather

than transport pupils to alleviate crowding problems,

whether in the short or long run, the Detroit Board was

economically encouraged to construct new classroom spaces;

their site choices, together with the State's negative

incentive, always having the effect, as shown above, of

compounding segregation. The Board's choice in the matter

resulted from its relatively favorable position with regard

to construction monies, which derive from bonding authority

but are limited by law to capital improvements, as com-

35/

pared to operating monies which are at a deficit in Detroit.

33/ (cont'd)

remove the last majority white school from the

already almost al^-black Mackenzie High School attendance

area. /A.IVa94 _/." (Mem. Op., A. Ia204 ).

34/ Some suburban districts, which would not be elibible

for state transportation money because of their status as

cities or villages, nevertheless receive it by virtue of a

"grandfather clause," i.e., they retain for this purpose

their status of some years ago. See, e.g., S.B. 1269, 1972

Reg. Sess., Sec. 71 (2) (a) (b).

35/ And this was so despite the fact that the State's

bonding capacity laws also discriminated against the Detroit

(cont'd on next page)

-35-

• •

(A.IVal29-30) . (Since the district was deprived of any

State busing funds, the transportation which was abso

lutely necessary was financed out of the operating budget).

(A.IIIa223-24) The converse of the foregoing--i. e., the

favorable treatment accorded many of the suburban school

districts surrounding Detroit--has worked hand-in-hand

with intra-Detroit discrimination practices to contain

black children in black schools within the City of Detroit

and, at the same time, provide white enclaves (with white

schools) in the outer parts of the Detroit metropolitan

area. And, of course, families desiring school transpor

tation for their children were induced to move to where it

would be provided; because of housing discrimination

white families were more mobile than black families. The

segregatory school construction practices, and their link

with housing discrimination, discussed above, knew no

political boundaries. The pattern is a continuous one,

uninterrupted by political subdivision boundary lines:

black schools were constructed and are maintained within

the center of Detroit, while white schools were constructed

35/ (cont'd)

district: all school districts in the State of

Michigan, save Detroit, have had a capital improvement bonding

authority of 57, of equalized valuation not requiring voter

approval; in Detroit alone the level was held to 270 until

1969 when the legislature increased it to 37,, and finally

to the state-wide level of 57, in 1970. (A. IVal32-34) .

-36-

and are maintained on the periphery of Detroit and

throughout the surrounding suburban communities. Between

iy50 and iy6y in the Detroit tri-county area, approximately

13,y00 "regular classrooms," capable of serving and

attracting over 400,000 pupils, were constructed, with the

approval of state authorities and with the help of the

discriminatorily favorable bonding authority accorded the

school districts in this area by the State (see note 35,

supra), in districts less than 2?0 black in pupil enroll

ment in iy/0-/l. (P.M. 14; P.M. 15). Obviously, white

families either within Detroit or moving into the area

were attracted to these schools (assured of their white

ness by the pervasive discrimination in housing) away

from blacker schools in Detroit and the blacker Detroit

36/

school district. (A,VIIa36~38 ). The attraction of white

36/ In building racially exclusive communities for the out

migration of whites, and the location of both newly forming

white family groups and white families moving into the Detroit

area, "white" schools were a necessary precondition to

"stable" and "desirable," i.e., white neighborhoods, in the

formerly stated view of the F.H.A. (P.X. 56b, iy36 F.H.A.

Manuel §§256, 265, 266):

"Of prime consideration to the Valuator is the

presence or lack of homogenity regarding types

of dwellings and classes of people living in

the neighborhood... Distances to the schools

should be related to the public or private

means of transportation available from the

(cont'd on next page)

-37-

• •

suburban schools to white families was certainly faci

litated by the discriminatory allocation of state

transportation aid to most (A Xal27-28,153-64 ) of these

suburban districts: whites seeking homes and schools

were assured that the State and its education agents

37/

would provide the means to get their children to school --

36/ (cont'd)

location to the school. The social class

of the parents of children at the school will

in many instances have a vital bearing... Thus...

if the children of people living in such an area

are compelled to attend school where the majority

or a good number of the pupils represent a far

lower level of society or an incompatible racial

element, the neighborhood under consideration

will prove far less stable and desirable than

if the condition did not exist. In such an

instance it might well be that for payment of

a fee, children of this area could attend

another sc .?ol with pupils of the same social

class."

The 1936 manual also reflects F.H.A.'s understanding that

white subdivision developments require white schools:

"if the children of people living in such area

are compelled to attend school where the majority

or a good number of the pupils represent a far

lower level of society or an incompatible racial

element, the neighborhood under consideration

will prove far less stable and desirable than if

the condition did not exist."

37/ In those suburban districts eligible for state

transportation aid, the percent of pupils bused in 1969-70

ranged from 427, to 52%. (A.Xal26-29 ).

-38-

as opposed to the setting in Detroit where publicly-financed

school busing was available only in emergency situations

and over-crowded schools.

Prior to 1962 the defendant State Board supervised

school site selection and construction throughout the state

and in the Detroit metropolitan area in p; rticular, where,

as seen above, construction and site selection practices

38/

served to create and compound school segregation. And

despite the State Board's policy statements in 1966 and

1970 recognizing site selection and construction practices

to be important factors determining whether integration

or segregation is the result (see page 33 , supra),

no action of any nature, insofar as the record reveals,

has ever been taken to implement or enforce these policies.

As the district court concluded (Metro. Op., A.Ia516 ):

The precise effect of this massive school

construction on the racial composition of

Detroit area public schools cannot be

measured. It is clear, however, that the

effect has been substantial. Unfortunately,

38/ The legislature removed those supervisory powers

in 1962 because the State Board had used them as a lever

to reduce the number of school districts in Michigan from

6,000 in 1945; in 19/1 there were 617 school districts in

the State. (A.IIIa99-100,104).

-39-

the State, despite its awareness of the

important impact of school construction

and announced policy to control it, acted

"in keeping generally, with the discrimina

tory practices which advanced or perpetuated

racial segregation in these schools." Rul

ing on Issue of Segregation at 14; See also

id., at 13.

The foregoing policies and practices have accomplished

the expected and forseeable result. In 1970-71, 74.9%. of

Detroit's black public school children were in State-identi

fied 90% black schools. (A.IXa357 (P.X. 129); A.IVa43-74).

Every school which was 90% or more black in 1960, and

which was still in use in 1970, remained 90% or more black.

(A.IXa467 (P.X. 150); A.IV72-73 ). As Deputy Superinten

dent Johnson acknowledged, "we still live with the results

of discriminatory practices." (A.IVa344~45).

2. Faculty Racial Identifiability

The record stands uncontroverted that there is a per

sisting racial pattern in the allocation of teachers to

schools: with few exceptions from 1960-61 to 1970-71,

despite recent good faith efforts by the Detroit School

Board to remedy the situation, disproportionate numbers of

white faculty generally are assigned to schools with predomi

nantly white student bodies and disproportionate numbers of

black faculty are generally assigned to schools with black

-40-

39/

student bodies. With some amelioration in recent years

within the city, the racial composition of faculty at

most schools remained roughly proportional to the racial

40/

compostion of the student population at these schools

39/The district court found tha : "The allegation that

the Board assigns black teachers to black schools is not

supported by the record" (Mem. Op., AIa206 ) (emphasis added)

"The Board did not segregate faculty by race, but rather-

attempted to fill vacancies with certified and qualified

teachers who would take offered assignments" (Mem. Op.,

A.Ia209 ) (emphasis added): "Substantial racial integration

of staff can be achieved, without disruption of seniority

and stable teaching relationships, by application of the

balanced staff concept of naturally occurring vacancies and

increases and reductions to teacher services." (Mem. Op.,

A.Ia209 ) (emphasis added) . Although plaintiffs believe that

the district court committed clear error in failing to find

a faculty segregation iolation on the following (in text),

largely uncontrovered proof (See, e.g., Davis v. School

Dist rict of Pontiac, 443 F. 2d 573 (6th Cir.), c.err. denied,

402 U.S. 913 (1971); Kelly v. Guinn, 456 F. 2d 100 (9th Cir.

1972); Booker v. Special School Dist. No.1, Minneapolis,

No. 4-71 Civil 382 (D. Minn. May 24, 1972)), we have chosen

not to perfect a cross appeal on this issue. Our reason is

that the error has been effectively rendered harmless