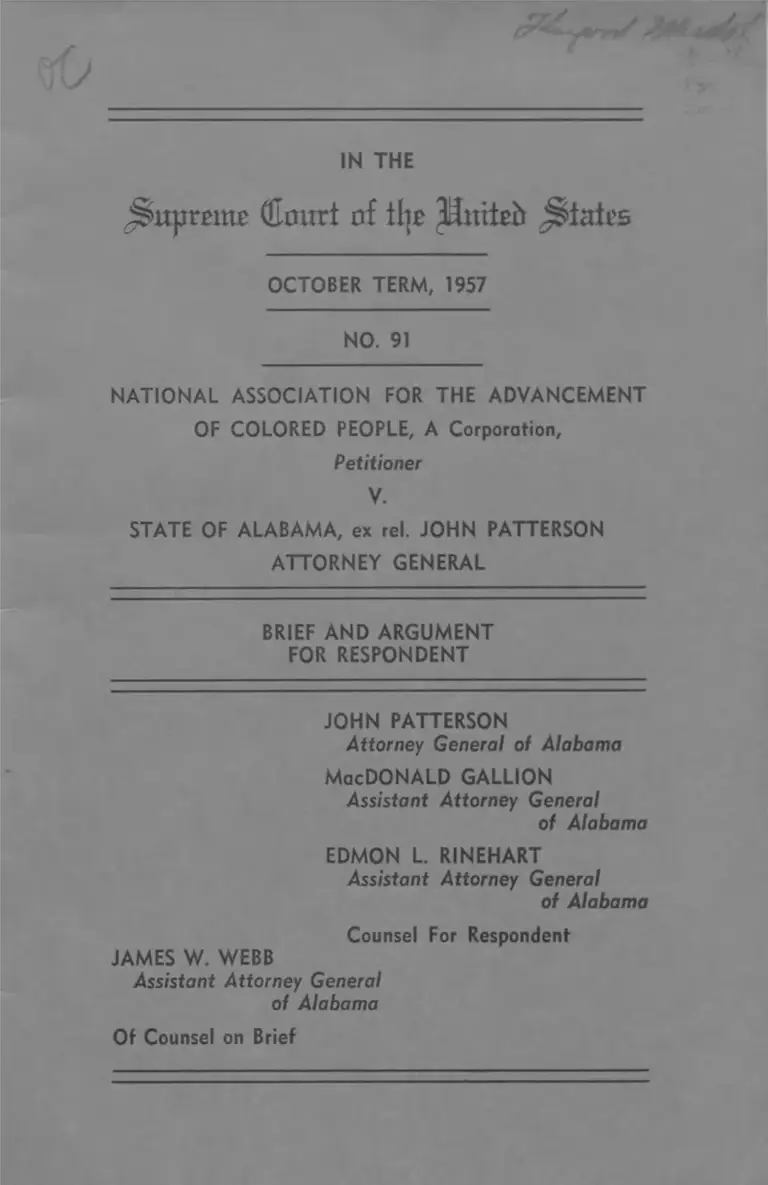

NAACP v. Alabama Brief and Argument for Respondent

Public Court Documents

October 18, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. Alabama Brief and Argument for Respondent, 1957. 29d5222e-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b2b216c8-c5a9-4515-8f2c-7e8ad06cfdee/naacp-v-alabama-brief-and-argument-for-respondent. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

f , . I

IN THE

jSupmtte (Court of tljr ffimizb jiia te

OCTOBER TERM, 1957

NO. 91

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT

OF COLORED PEOPLE, A Corporation,

Petitioner

V.

STATE OF ALABAMA, ex rel. JOHN PATTERSON

ATTORNEY GENERAL

BRIEF AND ARGUMENT

FOR RESPONDENT

JOHN PATTERSON

Attorney General of Alabama

MacDONALD GALLION

Assistant Attorney General

of Alabama

EDMON L. RINEHART

Assistant Attorney General

of Alabama

Counsel For Respondent

JAMES W. WEBB

Assistant Attorney General

of Alabama

Of Counsel on Brief

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Opinion Below ................................................................. 1

Jurisdiction 1

Questions Presented ................................................... X

Statement o f the Case ............................................... 2

Summary of Argument ..................................... 8

Argument

I. The judgment below, based upon State

procedure, left no Federal question

to be reviewed by this Court.......................13

II. The equity proceeding for injunction

and ouster was a reasonable and well

recognized exercise o f the State’s

police power ................................................... 1 9

III. The order to produce the corporation’s

records including names of members

and solicitors did not deprive either

the corporation or its members o f the

liberty guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment ...................................................25

Conclusion ........................................................... 3 1

TABLE OF CASES CITED

Page

Adamson v. California, 332 U. S. 46 11, 25

Application of Catalonian Nationalist Club

(1920) 112 Misc. 207, 184 N. Y. S. 132.................. 20

Davids v. Sillcox (1948) 297 N. Y. 355,

81 N. E. 2d 353 ...........................................................30

Doherty v. Moreschi et al (1946) 59 N. Y.

S. 2d 542 ........................................................................21

ii

Ex parte Baker (1898) 118 Ala. 185, 23 So. 996 9, 17

Ex parte Dickens (1909) 162 Ala. 272, 50 So. 218 8, 13

Ex parte Hart (1941) 240 Ala. 642, 200 So. 783 8, 15

Ex parte Monroe County Bank (1950) 254

Ala. 515, 49 So. 2d 161 9, 17

Ex parte Morris (1949) 252 Ala. 551,

42 So. 2d 17 .................................................... 8, 14, 15

Ex parte National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People, 91 So. 2d 214,

91 So. 2d 220, 91 So. 2d 221 ...................... 1, 7, 8, 10

Ex parte Sellers (1948) 250 Ala. 87,

33 So. 2d 349 .......................................................... 14,15

Goodall-Brown and Co. v. Ray (1910) 168 Ala.

350, 53 So. 137 ........................................................... 17

Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organizations,

307 U. S. 496, 514 11, 26

Hale v. Henkel, 201 U. S. 43 20, 25

Hammond Packing Company v. Arkansas,

212 U. S. 322 ........................................................... 9, 17

Henderson v. Henderson (1952) 329 Mass. 257,

107 N. E. 2d 773 ........................................................ 17

Herb v. Pitcairn, 324 U. S. 117 ............................. 8, 13

Ill

In re General Von Steuben Bund (1936)

159 Misc. 231, 287, N. Y. S. 527 ............................

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v.

Vogt, Inc. 354 U. S. 284 .................................... 10,

Jacoby v. Goetter Weil (1883) 74 Ala. 427 9,

Joint Anti-Fascist Committee v. McGrath,

341 U. S. 123, at 183 and 184 11, 12, 26, 28,

Knights of the Ku Klux Klan v. Commonwealth

(1924) 138 Va. 500, 122 S. E. 122 .......................

New York ex rel. Bryant v. Zimmerman,

278 U. S. 63 ...................................................16, 21,

Pacific Typesetting Co. v. International Typo

graphical Union (1923) 125 Wash.

273, 216 P. 358 .........................................................

People ex rel. Miller v. Tool (1905) 35 Colo. 225,

86 P. 224 ................................................................ 10,

People v. Jewish Consumptive Relief Society,

(1949) 196 Misc. 579, 92 N. Y. S. 2d 157 9, 16,

Pierce v. Grand Army of the Republic (1945)

220 Minn. 552, 20 N. W. 2d 489 .............................

Pierce v. Society o f Sisters, 268 U. S. 510 .........12,

Powe v. United States (C. C. A. 5) (1940) 109

Fed. 2d 147, cert, denied 309 U. S. 679 12,

Profile Cotton Mills v. Calhoun Water Co.,

(1914) 189 Ala. 181, 66 So. 50 .............9,

Rogers v. United States, 340 U. S. 367 ...................

State ex rel. Griffith v. Knights o f the Ku Klux

Klan (1925) 117 Kan. 564, 232 P. 254,

cert, denied 273 U. S. 664 ............... 9, 10, 16, 21,

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234 .12, 26,

Tileston v. Ullman, 318 U. S. 44 ...............................

20

21

17

29

21

30

21

23

20

10

28

29

16

25

23

27

26

IV

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542 12, 29

United States v. Josephson (C. C. A. 2.) (1947)

165 Fed. 2d 82, cert, denied 333 U. S. 838.............26

United States v. Rumely, 345 U. S. 41 12, 26, 28

United States v. White, 322 U. S. 694 11, 20, 25

United States v. United Mine Workers of

America, 330 U. S. 258 10

Watkins v. United States................................. 12, 26, 27

Wilkinson v. McCall (1945) 247 Ala. 225,

23 So. 2d 577 ...............................................................17

W olf v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25 11, 25

STATUTES

Title 7, Section 1061, Code of Alabama 1940 16

Title 10, Sections 192, 193 and 194,

Code of Alabama 1940 2, 3, 23

Title 10, Sections 194 and 195,

Code o f Alabama 1940 ..............................................23

New York Civil Rights Law, Section 53 ..................30

New York General Corporations Laws,

Sections 210, 211 and 219 ....................................... 20

New York Membership Corporation Law,

Section 10 ..................................................................... 20

New York Membership Corporation Law,

Section 2 6 ...................................................................... 30

United States Code:

Title 28, Section 1257 (3) ....................................... 1

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Constitution of Alabama 1901 Section 232 ......... 3, 23

Constitution of the United States, Amendment X 19

Federal Rule o f Civil Procedure, 37 (b ) 9, 17

IN THE

Supreme Olcmri of tl]t Pmtrfr jSiafcs

OCTOBER TERM, 1957

NO. 91

BRIEF AND ARGUMENT FOR RESPONDENT

OPINION OF THE COURT BELOW

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama

is reported in 91 So. 2d, at page 214.

JURISDICTION

The petitioner’s application for a writ of certiorari

from the Supreme Court of the United States to re

view the judgment o f the Supreme Court of Alabama,

rendered December 6, 1956, under the provisions of

Title 28, Section 1257(3), United States Code, Judici

ary and Judicial Procedure, has been granted. The

judgment of the Supreme Court o f Alabama was not

dependent upon a decision of any federal question.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I.

Has the petitioner, a foreign membership cor

poration, having neglected to avail itself o f the proper

remedy in the Alabama courts, and having chosen to

remain in contempt, standing to obtain review in this

2

Court of the orders and decisions of the Alabama

courts?

H .

Did the totality of the State’s action in seeking

an injunction and ouster of petitioner, a foreign cor

poration, and the procedure used to obtain evidence

upon the issues o f that action, exceed the powers re

served to the State by the Tenth Amendment?

m .

Did the State o f Alabama violate the rights o f the

petitioner, a foreign corporation, and of its members,

guaranteed by the implementation of the First Amend

ment by the Fourteenth Amendment, in demanding

the records and membership lists of petitioner?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Upon June 1, 1956, the State of Alabama, on the

relation of John Patterson, its Attorney General, filed

a bill in equity, against the petitioner, National Asso

ciation for the Advancement of Colored People, a

Corporation, in the Fifteenth Judicial Circuit, Mont

gomery County, Alabama. The gravamen of the bill

was that the corporation conducted extensive intra

state activities in pursuance of its corporate purpose in

Alabama without having filed with the Secretary of

State a certified copy o f its articles o f incorporation

and an instrument in writing, under the seal o f the

corporation, designating a place of business and an

authorized agent residing in Alabama, as required by

Title 10, Sections 192, 193 and 194, Code o f Alabama

1940, thus doing business in Alabama in violation o f

3

Section 232 of the Constitution of Alabama 1901, and

Title 10, Section 194, Code of Alabama 1940. (R pp.

1, 2, and 3).

The bill o f complaint alleged irreparable harm to

the property and civil rights o f the residents and citi

zens o f Alabama, for which criminal prosecutions and

civil actions at law afforded no adequate relief. A

temporary injunction and restraining order was re

quested, preventing the respondent below and its

agents from further conducting its intrastate business

within Alabama, from maintaining any offices and

organizing further chapters within the State. A per

manent injunction, in accordance with the prayer for

temporary injunction, was also prayed for. Finally,

an order o f ouster forbidding the corporation from

organizing or controlling any chapters of the National

Association for the Advancement o f Colored People

in Alabama, and exercising any of its corporate func

tions within the State, was requested. (R. p. 2).

On June 1, 1956, the Circuit Court of Montgom

ery County, Alabama, entered a decree for a tempo

rary restraining order and injunction, as prayed for

and further enjoined until further order of the court

petitioner from filing any application, paper or docu

ment for the purpose o f qualifying to do business in

Alabama. Service was had upon the corporation, at its

offices in Birmingham, Alabama. (R. pp. 18, 19, 20)

On July 2, 1956, petitioner filed a motion to dis

solve the temporary restraining order and demurrers

to the bill of complaint which were set for hearing on

July 17. On July 5th the State filed a motion to re

quire petitioner to produce certain records, letters and

4

papers alleging that the examination o f the papers was

essential to its preparation for trial. (R. p. 3)

The State’s motion was set for hearing on July 9,

1956. At the hearing, at which petitioner raised gen

erally but not explicitly both State and Federal con

stitutional objections, (R. p. 6) the court issued an

order requiring production o f the following items re

quested in the State’s motion:

“ 1. Copies of all charters o f branches or

chapters o f the National Association for the

Advancement o f Colored People in the State

o f Alabama.

“ 2. All lists, documents, books and papers

showing the names, addresses and dues paid

of all present members in the State of Ala

bama o f the National Association for the

Advancement o f Colored People, Inc.

“ 4. All lists, documents, books and papers

showing the names, addresses and official

position in respondent corporation of all per

sons in the State o f Alabama authorized to

solicit memberships in and contributions to

the National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People, Inc.

“ 5. All files, letters, copies of letters, tele

grams and other correspondence, dated or oc

curring within the last twelve months next

preceding the date o f filing the petition for

injunction, pertaining to or between the Na

tional Association for the Advancement o f

Colored People, Inc., and persons, corpor

5

ations, associations, groups, chapters and

partnerships within the State of Alabama.

“ 6. All deeds, bills o f sale and any written

evidence o f ownership of real or personal

property by the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, Inc., in the

State of Alabama.

“ 7. All cancelled checks, bank statements,

books, payrolls, and copies of leases and

agreements, dated or occurring within the

last twelve months next preceding the date

o f filing the petition for injunction, pertain

ing to transactions between the National As

sociation for the Advancement of Colored

People, Inc., and persons, chapters, groups,

associations, corporations and partnerships

in the State of Alabama.

“ 8. All papers, books, letters, copies of let

ters, documents, agreements, correspondence

and other memoranda pertaining to or be

tween the National Association for the A d

vancement of Colored People, Inc., and Au-

therine Lucy, Autherine Lucy Foster, and

Polly Myers Hudson.

“ 11. All lists, books and papers showing

the names and addresses of all officers,

agents, servants and employees in the State

of Alabama of the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People, Inc.

“ 14. All papers, books, letters, copies of let

ters, files, documents, agreements, corres-

6

pondence and other memoranda pertaining

to or between the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People, Inc.,

and Aurelia S. Browder, Susie McDonald,

Claudette Colvin, Q. P. Colvin, Mary Louise

Smith and Frank Smith, or their attorneys,

Fred D. Gray and Charles D. Langford.”

(R. pp. 20, 21 and 22)

The court then extended the time to produce un

til July 24th, and simultaneously postponed the hear

ing on petitioner’s demurrers and motion to dissolve

the temporary injunction to July 25. (R. p. 6)

On July 23, petitioner filed an answer on the

merits, denying certain intrastate activities constitut

ing doing business in Alabama. In addition, though

denying the applicability of the Alabama statutes, pe

titioner averred that it had procured the necessary

forms for the registration of a foreign corporation

supplied by the office of the Secretary of State of the

State o f Alabama, and filled them in as required.

Petitioner attached them to its answer and offered

to file same if the court would dissolve the order

barring petitioner from registering. At the same time

petitioner filed a motion to set aside the order to pro

duce which motion was set down for hearing on July

25th. (R. pp. 6 and 7)

On July 25, 1956, the court heard oral testimony,

and argument of counsel, the Attorney General testi

fying that if the petitioner would agree that it was

doing business in the State o f Alabama, and agree as

to the nature o f that business, the material sought by

motion would not be needed. (R. p. 7) The Court

overruled the motion to set aside and ordered the pro

7

duction o f the items stated in its previous order. Pe

titioner refused to comply with the court’s order, upon

which the court adjudged petitioner in contempt, as

sessed a fine of $10,000.00 against it for the contempt

with the further provision that unless the petitioner

complied with the order to produce within five days

the fine would be increased to $100,000.00 The Court

also decreed that if the petitioner complied with the

order, it would entertain a motion to remit the fine.

The petitioner’s motion to dissolve the temporaiy in

junction was not heard in view of its contempt in

refusing to obey the order to produce. (R. pp. 7-11)

Upon July 30, 1956, petitioner filed, with the trial

court, a motion to set aside or stay execution of the

contempt decree pending review by the Supreme

Court of Alabama. Petitioner also tendered miscel

laneous documents which it alleged to be substantial

compliance. At all times the corporation refused to

produce the names and addresses o f its members. This

motion was denied and petitioner then filed a motion

in the Supreme Court o f Alabama, requesting stay of

execution o f the judgment below pending review by

the appellate court. This motion or application was

also denied.1 On the same day the Circuit Court en

tered an order adjudging petitioner in further con

tempt, increasing the fine to $100,000.00, in view of

its continued refusal to obey the order to produce. (R.

pp. 11-15)

On August 8, petitioner filed a purported peti

tion for writ o f certiorari in the Supreme Court of

Alabama. After oral argument on August 13, 1956,

1. 91 So. 2d 220.

8

the Supreme Court o f Alabama, denied the writ on

the grounds o f insufficiency.2

Thereafter on August 20, 1956, petitioner filed

a second petition for writ o f certiorari.3 Upon Decem

ber 6, 1956, the Supreme Court of Alabama denied

the writ requested in this petition.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

1. The United States Supreme Court does not

review state court judgments based upon an adequate

and independent nonfederal ground. Herb v. Pitcairn,

324 U. S. 117. The nonfederal basis of the judgment

o f the Supreme Court of Alabama is real and not il

lusory. Though Ex parte Dickens, 162 Ala. 272, 50

So. 218, holds certiorari the proper method to review

contempt, the established law of Alabama is that

mandamus is the proper method by which to review

an order to produce. Ex parte Hart, 240 Ala. 642, 200

So. 783. Petitioner could have raised all constitutional

questions in mandamus proceedings but elected or

neglected to take such action though it had adequate

time, fifteen days, before being required to produce

the records. Ex parte Morris, 252 Ala. 551, 42 So.

2d 17, is o f no avail to petitioner because in that case

the writ o f certiorari to review a contempt citation for

failure to produce records was also denied. In both

Ex parte Morris and the case at bar the Alabama Su

2. 91 So. 2d 221.

3. The grounds alleged by the petitioner in both the

first and second petitions for certiorari appear at

Record pages 16 and 17.

9

preme Court considered questions o f constitutional law

for the future guidance of lower courts but not as the

basis o f its decision.

2. The procedure to obtain the records was in

keeping with established Alabama law. Ex parte Mon

roe County Bank, 254 Ala. 515, 49 So. 2d 161; and

Ex parte Baker, 118 Ala. 185, 23 So. 996. The re

quested records were relevant both to issues raised

by the motion to dissolve the injunction and those

raised by the answer. The documents required could

have been used to prepare affidavits on the motion

to dissolve, as well as in presenting the case on the

merits. Profile Cotton Mills v. Calhoun Water Co.,

189 Ala. 181, 66 So. 50. The nature and extent o f the

corporation’s business within Alabama was the heart

of the matter because upon it depended the jurisdic

tion of the court and the type and severity of sanc

tions, if any, to be imposed upon petitioner. State ex

rel. Griffith v. Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, 117 Kan.

564, 232 P. 254, cert, denied 273 U. S. 664; and People

v. Jewish Consumptive Relief Society, 196 Misc. 579,

92 N. Y. S. 2d 157.

3. The procedure of precluding from further

proceeding with a case a party, which has refused to

produce evidence necessary to determination of the

issues therein, is neither novel, unfair or unconstitu

tional. Federal Rule o f Civil Procedure 3 7 (b ) ; Ham

mond Packing Co. v. Arkansas, 212 U. S. 322. Nor

is it unusual for a party in contempt to be prevented

from further proceeding on the merits. Jacoby v.

Goetter Weil Co. 74 Ala. 427.

4. Thus, it can be seen that the petitioner’s own

disregard for Alabama procedure placed it in the po

10

sition where it could not test the validity o f the order

to produce but could either comply or stand in

contempt.

5. The size of the fine was not excessive. United

States v. United Mine Workers of America, 330 U. S.

258; and Ex parte National Association for the Ad

vancement of Colored People, 91 So. 2d 214.

1. The police power is one of those reserved to

the states by the Tenth Amendment. That amendment

is o f equal dignity to the rest o f the Constitution in

cluding amendments preceding and following it. A

corporation, being an artificial entity, is subject to the

restraints o f the police power more than a natural

person and has fewer rights. It has no right of pri

vacy or privilege against self-incrimination. Corpora

tions and membership associations are subject to the

laws of a state within which they would operate

whether that be of their domicile or not. International

Brotherhood of Teamsters, Local 695 A. F. L. v. Vogt,

Inc., 354 U. S. 284; Pierce v. Grand Army of the Re

public, 220 Minn. 552, 20 N. W . 2d 489; and State Ex

rel. Griffith v. Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, 117 Kan.

564, 232 P. 254, cert, denied 273 U. S. 664.

2. It is a legitimate exercise of a state’s police

power and proper for its attorney general to proceed

in equity to enforce laws enacted to protect its people

even though the acts enjoined also be crimes. State

Ex rel. Griffith v. Knights of the Ku Klux Klan; and

People Ex rel. Miller v. Tool, 35 Colo. 225, 86 P. 224.

3. There is no reason why a membership cor

11

poration devoted to propaganda, promotional activi

ties, even good works, and the furthering o f the inter

ests o f its members or o f particluar groups should be

exempt from the registration statutes o f the states and

the penalties for violating them. Such a corporation

can commit the same torts as commercial ventures, the

same crimes. In these days of mass media, complex

and subtle methods of influencing public opinion the

state and its people have a real interest in knowing

the identity of those who would pool their powers as

individuals in corporate form to achieve their ends.

Those who act as a corporation must expect to be

treated as a corporation.

m.

1. Corporations, associations, and similar or

ganized groups concededly have a right of freedom

o f speech and press. They do not have a right of

privacy or secrecy, Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Com

mittee v. McGrath, 341 U. S. 123, at pages 183 and

184; nor privilege against self-incrimination, United

States v. White, 322 U. S. 694. They are not entitled

to the privileges and immunities o f natural persons nor,

any more than a natural person, may they assert an-

others rights. Hague v. Committee for Industrial Or

ganization, 307 U. S. 496, at page 514.

2. The Fourteenth Amendment does not incor

porate the first eight amendments. Adamson v. Cali

fornia, 332 U. S. 46; and W olf v. Colorado, 338 U. S.

25.

3. Four cases are the basis o f petitioner’s claim

that its freedom of speech and press and those o f its

members was unconstitutionally abridged. O f these

12

three, Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178; Sweezy

v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234; and United States

v. Rumely, 345 U. S. 41, deal with the assertion by a

natural person of the right to remain silent concerning

his political associations, or subscribers to his publi

cations, or the subject matter o f his speeches, when

questioned by an investigative committee. The W at

kins and Sweezy cases hold essentially that a person

cannot be held in contempt for failure to answer ques

tions which are not relevant to a well defined line of

inquiry. The vagueness of the standard by which the

person interrogated must judge his right not to answer

makes a contempt conviction a denial of due process.

The Rumely case was not decided on constitutional

grounds. Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v.

McGrath, has no majority opinion and at most can

be construed as holding that an ex parte Attorney

General’s listing of an organization as ‘ ‘subversive”

injures its reputation without granting the hearing

which due process requires. It will be seen that in

̂ all these cases it was action by the sovereign upon the

individual, not the danger of pressure by private per

sons upon members o f an organization, which was held

v to be a violation of constitutional rights.

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510, holds

merely that a statute compelling all children to attend

public schools deprives without due process private

organizations o f the property right to be in the edu

cation business.

Petitioner has justified its refusal to produce its

records on the mere speculation of injury by private

persons to its members. Private action is not state

action. United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542; and

Powe v. United States, 109 Fed. 2d 147, (C. C. A. 5),

cert, denied United States v. Powe, 309 U. S. 679.

13

ARGUMENT

I.

THE JUDGMENT BELOW, BASED UPON STATE

PROCEDURE, LEFT NO FEDERAL QUESTION

TO BE REVIEWED BY THIS COURT

1. The United States Supreme Court will not

review a state court judgment based upon an adequate

and independent nonfederal ground. The reason for

this rule is obvious. It lies in the division of power

between the state and Federal judicial systems. The

power of the Supreme Court over state judgments is

to correct them only to the extent that they adjudge

Federal rights and not to pass upon state court opin

ions concerning Federal questions which are not neces

sary to the decisions. Herb v. Pitcairn, 324 U. S. 117.

Therefore, before this Court will review a state

court case it must determine either that the decision

of the state court was based upon a federal ground or

that any nonfederal ground for the decision was in

adequate by itself to support the state court judgment.

The petitioner attempts to show that the non

federal ground for the decision o f the Supreme Court

of Alabama is illusory. It contends that the Alabama

Court departed from a long standing State procedure

permitting review of contempt proceedings by cer

tiorari. That opinion reveals the error o f this conten

tion by citing Ex parte Dickens, 162 Ala. 272, 50 So.

218. Respondent does not concede, as petitioner states

upon page 2 o f its brief, that, because certiorari is the

proper method of reviewing a contempt citation, the

holding in the case at bar that mandamus was the

14

proper remedy to review an order to produce was in

any way a departure from established State procedure.

Rather, by mandamus the aggrieved party can obtain

review without the danger of a contempt citation. The

petitioner chose another course though it had ample

time in which to have filed mandamus proceedings

prior to July 25, 1956. The petitioner elected to test

this order by refusal to obey thus subjecting itself to

contempt proceedings. The Supreme Court of Ala

bama reviewed those contempt proceedings with a

view to determine whether the trial court had juris

diction of the person and subject matter, whether the

proceedings were valid and regular on their face, and

whether the lower court had exceeded its authority.

Petitioner, in the jurisdictional statement of its

brief on the merits, touches lightly on this facet of the

Alabama decision, but in its petition for certiorari re

lies upon Ex parte Morris, 252 Ala. 551, 42 So. 2d 17,

Ex parte Sellers, 250 Ala. 87, 33 So. 2d 349, and simi

lar cases, to show that the Supreme Court o f Alabama

used the device of State procedure to preclude review

of its decision. Those cases cited by the petitioner fail

wholly to support that contention. For example, in

Ex parte Morris, the Alabama Supreme Court did not

grant the writ of certiorari and then affirm the case

but rather in the first instance denied the writ. After

deciding that Morris’ petition showed a direct con

tempt committed in the presence of the court, that

due process was afforded the petitioner, and that no

error appeared on the face o f the record, the court

denied the writ o f certiorari, but deemed it advisable

that the opinion further exposit the views of the court

for future guidance upon problems of this nature. The

attention of this Court is called to the parallel in the

opinion delivered by the Supreme Court of Alabama

15

in this case. The court therein denied the writ of cer

tiorari on essentially the same grounds as in Ex parte

Morris, but in order that the parties might understand

its views on the subject, wrote to the merits o f the

petitioner’s constitutional objections. Thus, expres

sions of opinion on constitutional matters were not

necessary to the decision and are not before this Court.

The only thing before this Court is the adequacy of

the nonfederal grounds of the decision. The Supreme

Court of Alabama clearly stated and demonstrated by

ample authority that mandamus is the correct and the

only procedure to review an order to produce records.4

Such cases as Ex parte Sellers, are not in point, as

these cases either deal with a direct contempt or the

refusal to obey a court order not reviewable by

mandamus.

2. At pages 37 and 38 of the petitioner’s brief,

it argues that the procedure followed in the trial court

was calculatedly designed to place it in a position

where it could not obtain a hearing on its motion to

dissolve the temporary injunction and ultimately on

the merits of the case. Analysis o f the order o f events

rebuts this argument. The motion to produce was

granted on notice and hearing. Between July 9 and

July 24, there was ample time to have contested the

order to produce by mandamus, or to obey.

The records and documents were relevant to proof

of the nature and methods of petitioner’s business in

Alabama. It was proof necessary to determine whether

the temporary injunction should remain in effect and

whether or not a permanent injunction and ultimately

an order of ouster should be granted.

4. Ex parte Hart, 240 Ala. 642, 200 So 783.

16

It is true that, if objected to, oral testimony is not

admissible on a motion to dissolve a temporary injunc

tion, but affidavits are permitted. Profile Cotton Mills

v. Calhoun Water Co., 189 Ala. 181, 66 So. 50; and

Title 7, Section 1061, Code of Alabama 1940. The

names and addresses of petitioner’s members were

needed for the State’s preparation of affidavits in op

position to the motion to dissolve. In this connection,

it should be remembered that the petitioner’s answer,

while admitting some of the State’s allegations, denied

that it had solicited members for either the local chap

ters or the parent corporation or that it had organized

local chapters within the State (R. p. 7). The Attorney

General testified that the records would not be required

if petitioner would admit that it was doing business

within Alabama and disclose the nature and extent

thereof." To this offer the petitioner did not agree.

Since the petitioner had filed an answer and sub

mitted to the jurisdiction o f the court, a trial on the

merits could have followed immediately, whether or

not the temporary injunction was dissolved. Thus, the

State needed to examine the corporation’s records in

the aid of its preparation for trial. It is nowhere the

rule that a party may not examine documents to be

used in preparation o f a case until such time as trial

on the merits has commenced in court. The Federal 5

5. Solicitation o f funds or membership within a state

is doing business so as to subject a corporation to

state regulation and restraint. People v. Jewish

Consumptive Relief Society, 196 Misc. 579, 92 N.

Y. S. 2d 157; State ex rel. Griffith v. Knights of

the Ku Klux Klan, 117 Kan. 564, 232 Pac. 254,

cert. den. 273 U. S. 664; and New York ex rel

Bryant v. Zimmerman, 278 U. S. 63.

17

Rules o f Civil Procedure contain far reaching discov

ery procedures. Numerous states, such as New Jersey,

have followed the lead o f the Federal courts. And

the penalties for refusing discovery can be severe. For

example, Federal Rule o f Civil Procedure 37(b) au

thorizes default judgment against a party contuma

ciously refusing to disclose documents necessary and

relevant to the issues of a cause. As far back as Ham

mond Packing Co. v. Arkansas, 212 U. S. 322, it was

held that when a defendant corporation disobeyed an

order to secure the attendance of its officers, agents,

directors and emploees as witnesses and refused pro

duction of books, papers and documents in their pos

session, it was not a denial of due process to permit

the rendering of a default judgment against it. What

some states have prescribed by statute, Alabama per

mits as a matter o f common law.0 This rule of denying

a party in contempt the right to proceed further with

a trial pending its purging itself o f contempt, even

when the flouted order was interlocutory, is recognized

in other states. Henderson v. Henderson, 329 Mass.

257, 107 N. E. 2d 773.

Lest the action o f the Alabama Supreme Court

be lightly disregarded as a device to frustrate review

by the United States Supreme Court, we reiterate that

the corporation had fifteen days in which to have filed

a petition for writ o f mandamus to obtain review of 6

6. Ex parte Monroe County Bank, 254 Ala. 515, 49

So. 2d 161; Ex parte Baker, 118 Ala. 185, 23 So.

996; Goodall-Brown and Co., et al. v. Ray, 168 Ala.

350, 53 So. 137; Wilkinson v. McCall, 247 Ala.

225, 23 So. 2d 577; and Jacoby v. Goetter Weil

Co., 74 Ala. 427.

18

the trial court’s order to produce before being called

upon to disclose its records. During this time petition

er’s sole action was to file an answer which carefully

avoided describing the character and extent o f its ac

tivities in Alabama. Yet this answer, together with

certain affidavits purporting to show that its members,

if known, were subject to pressure by private citizens

of Alabama, was offered as the excuse for its refusal

to produce its corporate records. It was not until its

attorneys had said that those records would not be

produced and the corporation was held in contempt

that the petitioner attempted to obtain from the ap

pellate courts of Alabama review of the order making

it produce its records.

As this Court has so often stated, it is constitu

tionally barred from reviewing a State court judgment

resting on a nonfederal ground. The sovereignty of

State’s government, so fundamental to our constitu

tional system requires that this Court confine its re

view to those cases which inescapably present a fed

eral question. Can it be said after reading the careful

analysis o f the applicable Alabama law contained in

the opinion o f the Supreme Court o f Alabama in this

case and the record on appeal, that the decision of a

federal question was necessary to the conclusion to

deny the writ? Rather, the petitioner’s own inatten

tion to and deliberate disregard of established pro

cedures, similar to those recognized in other jurisdic

tions, placed the petitioner in its present dilemma.

19

II.

THE EQUITY PROCEEDING FOR INJUNCTION

AND OUSTER W AS A REASONABLE AND

WELL RECOGNIZED EXERCISE OF

THE STATE’S POLICE POWER.

1. “ The powers not delegated to the United

States by the Constitution nor prohibited

by it to the states, are reserved to the

states respectively, or to the people.”

Thus, reads the Tenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion o f the United States. Without it that Constitu

tion, the authority by which all branches o f the Federal

government act, would not exist. It is a provision of

equal dignity to all other portions o f that Constitu

tion, including those amendments which precede it in

order or were adopted thereafter. It is true that in

its history judicial interpretation has restricted the sov

ereign power of the states, but the police power has

never been questioned as one of these reserved rights

of the states without which they would cease to be

sovereign entities. What are the limitations on this

police power? That is what this Court must decide if

it leaps the initial hurdle o f deciding that the decision

o f the Supreme Court of Alabama in this case was

necessarily based upon a Federal ground. In analyz

ing the extent o f the police power o f the several states

in the context of this case it is helpful to examine what

states other than Alabama have done to control the

activities of domestic and foreign corporations within

their borders.

That a corporation is an artificial entity subject

to restraint by the sovereign which grants it life or

20

which permits it to function within the sovereign’s

boundaries is axiomatic. That a corporation does not

have all the rights of a natural person, because o f its

artificial character, is also basic law. Hale v. Henkel,

201 U. S. 43; and United States v. White, 322 U. S. 694.

The petitioner herein would have this Court be

lieve that, because it is a membership corporation

which engages in propaganda and political activities

and seeks to promote the interests of its members, it

is entitled to wear a cloak of not only immunity but

invisibility nullifying the constitutional power o f the

states to inquire into, regulate, and curtail its activities.

It makes this claim in the face o f the statutory and

case law of the state of its origin.7

W e need not go beyond the New York General

Corporation Law, Sections 210, 211 and 219, to see

that a foreign corporation, which either does unlicensed

business within New York or exceeds the powers which

New York permits it to exercise within its borders, is

subject to injunction and ouster.8 Labor unions, which

7. The New York Membership Corporation Law, Sec

tion 10, empowers Justices of the State Supreme

Court to pass upon the purpose of membership

corporations and disapprove them if they offend

either New York public policy or the individual

Justice’s opinion as to desirability of purpose.

Application of Catalonian Nationalist Club, 112

Misc. 207, 184 N. Y. S. 132; In re. General Von

Steuben Bund, 159 Misc. 231, 287 N. Y. S. 527.

8. People v. Jewish Consumptive Relief Society,

196 Misc. 579, 92 N. Y. S. 2d. 157.

21

are certainly entitled to as much consideration as this

corporation, are also subject to state restraint.9

However, even more strikingly in point with the

case at bar, are three cases sustaining the power o f the

state to regulate another membership corporation

whose charter also contains statements o f worthy aims

and ends, namely, The Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

The cases are, State ex rel. Griffith v. Knights of the

Ku Klux Klan, 117 Kan. 564, 232 P. 254, cert, denied,

273 U. S. 664; Knights of the Ku Klux Klan v. Com

monwealth, 138 Va. 500, 122 S. E. 122; and New York

ex rel. Bryant v. Zimmerman, 278 U. S. 63. The peti

tioner would have it that these cases may be explained

on the basis o f judicial notice that the Klan is an or

ganization based upon bigotry and committed to vio

lence. Similarly, this Court is asked to take judicial

notice o f the noble character and purpose of petitioner

based upon publications, periodicals and news reports

whose accuracy, impartiality and reliability are not

subject to the tests usually reserved for evidence ad

mitted in court. If such judicial notice is permitted, an

appellate record loses its value and briefs on appeal

become a battle o f magazine and newspaper opinion.

To return from this digression to the more fun

damental issues in this case, the striking similarity of

9. Doherty v. Mareschi, et ah,

59 N. Y. S. 2d 542;

International Brotherhood of Teamsters

v. Vogt, Inc.

354 U. S. 284;

Pacific Typesetting Co. v. International

Typographical Union,

125 Wash. 273, 216 P. 358.

22

Kansas’ successful action against the Ku Klux Klan

to that which Alabama commenced againt this recal

citrant corporation, which would set itself above the

law, is immediately evident. The Supreme Court of

Kansas outlined, on the basis o f a Commissioner’s re

port, the activities o f the Klan in Kansas. It sustained

the ouster o f the Klan, even though it was a member

ship corporation, while expressly accepting the com

missioner’s finding that the evidence was insufficient

to show that the Klan engaged in violence and intimi

dation. The Supreme Court o f the United States denied

certiorari. Thus, despite the somewhat ambiguous con

clusion to be drawn from denial o f certiorari by the

United States Supreme Court there is no ambiguity

about the assertion of the right o f Kansas to regulate

and oust nonprofit membership corporations doing

business within its borders. It is submitted that this

case alone is sufficiently authority upon which to sus

tain the initial proceedings in Alabama.

2. Petitioner makes a somewhat halfhearted at

tack on the validity o f the action for injunction and

ouster upon the grounds that equity will not enjoin

violation o f statutes for which there is a criminal pen

alty. W e do not quarrel with the general rule that

equity will not aid in enforcement of a penalty nor

the rule that equity will not act where there is an ade

quate remedy at law. But do those rules apply in this

case? The fact is that this is not an action to enforce

a penalty but rather to forbid the doing of an act which

is also a crime. This last equity most certainly will do,

as in the case of the enjoining o f gambling houses and

liquor nuisances even though both gambling and pos

session of illegal liquors are crimes. In the case at

bar, the State had no adequate remedy at law since

each act o f solicitation o f membership constituted a

23

separate violation of Title 10, Sections 194 and 195,

Code of Alabama 1940. The multiplicity o f criminal

actions necessary to enforce these statutes against such

an organization, its officers and agents is self-evident.

The interest o f Alabama in protecting its citizens

from an abuse o f their personal and property rights

is found in the declaration o f the State policy o f Title

10, Sections 192 and 193, Code of Alabama 1940, and

the Constitution of Alabama 1901, Section 232. The

Griffith case sustained the power o f Kansas in a simi

lar action to protect the similar rights of the people

o f Kansas. The power to protect by injunctive pro

cess was also sustained in People Ex rel. Miller v. Tool,

35 Colo. 225, 86 P. 224.

3. The reason why a corporation is subject to

this regulation is that an artificial body, created by the

State, is naturally limited by the rules set by its crea

tor. Those who would unite in coporate form and en

joy its benefits must also accept its disadvantages. If

they would act through a corporation, they must be

prepared to be treated as a corporation. Now how is

a membership corporation, devoted ostensibly to good

works, political activity, and propaganda, but financed

by membership subscriptions and solicited contribu

tions, so different from the ordinary commercial cor

poration that it should be free from regulation, free

from the restraints which the sovereign can ordinarily

impose?

It can libel and slander, it can make and break

contracts. By its agents it can commit torts or crimes,

just as can the most crassly commercial venture. If

it does these things, who is to be served, where is he

to be found?

24

If petitioner should be free of regulation and re

straint, why should not trade associations, manufac

turers associations, advertising firms, all those who

deal in public relations, be free of examination into

their affairs on the theory that their primary function

is to inform the public, to influence opinion and the

resulting action, and in many cases, to persuade legis

latures to specific ends and the public to particular

political action? In these days of subliminal adver

tising and other subtle and indirect ways o f obtaining

the desired but not readily apparent ends of various

groups, the right of the sovereign to know and the

people to know who are these idea peddlers is fully

as great as the right to trade in those ideas. In fact,

the very right to dissent which the State must not de

stroy, which is so fundamental to our free society, can

be destroyed by the unrestrained action o f organiza

tions who, because they claim noble aims and lofty

purposes, also claim a constitutional right to secrecy

and privacy. Yet the very power of these groups to

act in concert in corporate or membership form is

granted by the sovereign who most certainly must

have the right to see that this power is neither abused

nor misused.

25

m .

THE ORDER TO PRODUCE THE CORPORATION’S

RECORDS INCLUDING NAMES OF MEMBERS

AND SOLICITORS DID NOT DEPRIVE

EITHER THE CORPORATION OR ITS

MEMBERS OF THE LIBERTY GUAR

ANTEED BY THE FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENT.

In analyzing why the liberties o f neither the cor

poration nor its members have been abridged, we shall

discuss, first the constitutional rights o f the corpo

ration, second the fact that the corporation may not as

sert the rights o f its members, and third the constitu

tional rights o f those members.

1. At the outset it should be clearly understood

what rights and liberties a corporation has, and which

it does not have, guaranteed by the Fourteeth Amend

ment. W e concede that a corporation has the First

Amendment rights o f freedom o f speech and freedom

of the press. W e do not concede that a corporation

has a privilege against self-incrimination, or freedom

from a reasonable search or seizure to require produc

tion o f corporate records. Hale v. Henkel, 201 U. S.

43; United States v. White, 322 U. S. 694; and Rogers

v. United States, 340 U. S. 367. Nor does the Four

teenth Amendment incorporate the first eight amend

ments to the United States Constitution. It is only

when the state intrusion is so shocking that it amounts

to a denial o f due process that state action is held to

be unconstitutional. Adamson v. California, 332 U. S.

46, and W olf v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25. In this con

nection the rights of natural persons are o f more con

cern to this Court than those o f corporations.

26

Thus, we come to the rights of a corporation which

are secured by the Fourteenth Amendment. Conced-

edly, they include freedom of speech and freedom of

press. They do not include freedom of association, a

right of privacy, or the right to assert the privilege of

others, including members. This Court has held that

natural persons alone are entitled to the privileges and

immunities o f Section I of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization, 307

U. S. 496. But not even natural persons can invoke

the constitutional rights of others. Tileston v. Ullman,

318 U. S. 44; and United States v. Josephson, (C. C.

A. 2 ), 165 Fed. 2d 82, 89, cert, denied 333 U. S. 838.

2. The cases which petitioner claims support the

contention that it may assert the rights o f its members

or at least may refuse to disclose the names o f its mem

bers because o f possible ill effects upon its operations

are four. United States v. Rumely, 345 U. S. 41; Joint

Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341 U. S.

123; Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234; and

Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178. By a parlay

o f these four decisions petitioner attempts to justify

a rule that a corporation may conceal the identity of

its members if those members, once identified would

tend to fall away from membership with a resulting

loss of the corporate strength. As was pointed out on

pages 14 and 15 o f respondent’s brief in opposition

to the petition for writ of certiorari, this, when studied,

is a somewhat involuted concept. Yet it has a decep

tive simplicity similar to Decartes’ famous dictum “ I

think, therefore I am.” It has the same metaphysical

quality o f requiring an act o f faith as the basis for the

syllogism. Their reasoning seems to be: W e are an

organization o f individuals; our individual members

have certain constitutional rights, therefore we the

27

organization have those constitutional rights since we

are the mere sum of all our members. This reasoning

overlooks the nature of a corporation, which is some

thing more than the mere sum of its individual mem

bers. Rather, it is an artificial entity through which

the members act and which, because it permits them

to shield themselves from certain personal liabilities,

is subject to more restraints than a natural person.

It can be seen that Watkins and Sweezy were both

asserting individual personal rights of freedom of

speech and association. As we interpret the majority

opinion in both cases it held that the two men were

denied due process when compelled to answer ques

tions concerning their associations and political con

nections in the absence o f a showing that the questions

were related to a well defined line of inquiry in which

the sovereign had a substantial interest. Certainly, the

Watkins case, is based upon the fact that the questions

were so discursive, the directive o f Congress and the

investigating body’s interpretation thereof so broad

that Watkins had no way of telling what he might

properly decline to answer and what he could not re

fuse. Thus, his prosecution was a denial of due pro

cess because no clear standard of conduct was estab

lished by which he could judge the legality o f his ac

tions. With Sweezy, the question was similar and the

majority opinion seems to hold that the Attorney Gen

eral’s questions were not related to matters entrusted

to his investigation by the legislature. Thus, the in

vasion o f Sweezy’s personal rights was not warranted

and contempt based thereon was a denial o f due pro

cess. In both cases, even though they sustained the

right not to give information, the rights asserted were

personal to individual citizens as contrasted with

corporations.

28

Rumley’s case involved the assertion of the right

not to give certain information concerning persons who

subscribed to his publications. No majority opinion

sustained his refusal upon constitutional grounds.

While Mr. Justice Black’s concurring opinion dealt

with freedom of the press and his thought was that

the official harassment o f people who bought Rumley’s

tracts might injure Rumley’s business, to that extent

abridging his exercise of freedom of spech and free

dom of the press, it is clear that the opinion is con

cerned with the possibility of harassment o f the press

by public officials under the guise o f obtaining

information.

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath,

341 U. S. 123, has no majority opinion. The Justices

agreed that the Committee had some standing to sue

because the act o f the Attorney General, in declaring

the organization subsersive, injured its reputation

naturally causing it to lose membership. It was char

acterizing it as subversive without a hearing which con

stituted denial o f due process. It is true, that Mr. Jus

tice Jackson expressed the thought that the organiza

tions could assert the rights of their members. He also

said, at pages 183 and 184, that corporations, organ

ized groups or associations which solicit funds or

memberships had no right of privacy or secrecy. The

fact that members were held up to scorn and obloquy

did not entitle them to secrecy. This can only be taken

as meaning that memberships cannot be kept secret.

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510, cited

by petitioner for the proposition that a corporation

may assert constitutional rights of others including

their rights to free association, deals with none of

these. It holds simply that an Oregon statute com-

29

pelling all children to attend public schools deprived,

without due process of law, private organizations of

their property rights to conduct schools. The action

o f the Oregon Legislature directly interfered with

that property right.

3. At this point a very important distinction

must be made between all these decisions and the case

at bar. It is true that an Alabama court has ordered

this corporation to reveal the names of its members

and solicitors. But the interference, if any, with the

rights of the corporation and its members are at best

a matter of conjecture. And, in no event, consists of

more than exposing of the members to public criti

cism and possible economic and social pressure by

private individuals. Neither the privileges and im-

munties of the First Amendment nor the rights created

by the Fourteenth Amendment are protected against

individual as contrasted with state action. United

States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542; and Powe v. United

States, (C. C. A. 5) 109 Fed. 2d. 147, cert, denied

United States v. Powe, 309 U. S. 679. Mr. Justice

Jackson recognized the distinction in Joint Anti-Fascist

Refugee Committee vs. McGrath, 341 U. S. 123, when

he placed his decision that the rights of members were

abridged, upon the basis that ex parte listing o f an

organization as subversive without a hearing resulting

in an automatic dismissal o f government employees

who were members therein deprived these employees

of their livelihood wthout due process.

4. The petitioner, at page 40 of its brief, at

tempts to show that it was denied due process by

quoting two excerpts from a speech made by the

learned trial judge almost a full year after the pro

ceedings before him in the case at bar. It argues that

30

because he was opposed to integration, organizations

committed to integration of the races could not receive

a fair hearing before him. Likewise, might the Daily

Worker, an organ of the Communist party, argue that

no Federal or state judge could sit upon a case in

volving that publication, because all such judges must

take an oath to uphold the Constitution o f the United

States; a priori committing themselves as foes of Com

munism. Such argument, and petitioner uses it to be

labor all officials o f Alabama in building up a picture

of calculated denial o f its rights, could be used to de

velop a sort o f Parkinson’s law that the more unpopu

lar an organization is, the greater is its freedom from

control and examination by the sovereign. New York,

the petitioner’s State of origin, recognizes no such rule.

The New York Civil Rights Law, Section 53, compels

membership corporations which require an oath as

prerequisite or conditions of membership, with certain

exceptions, to file a roster o f their membership and

list o f their officers for each year. The constitution

ality o f this statute was upheld by the United States

Supreme Court in New York ex rel Bryant V . Zim

merman, 278 U. S. 63.10 It is difficult to see why Ala

bama may not obtain, by judicial order, evidence rele

vant to issues in a proceeding to enforce its corpora

tion laws, similar to that which New York may consti

tutionally extract from corporations by virtue o f a

statute.

10. New York also permits visitorial rights by the

Supreme Court over membership corporation by

statute: New York Membership Corporation Law,

Section 26; and compels production o f records

by mandamus as a matter o f common law. Davids

v. Sillcox, 297 N. Y. 355, 81 N. E. 2d 353.

31

CONCLUSION

The petitioner neglected to avail itself o f the es

tablished procedure o f petition for writ o f mandamus

to review the trial court’s order to produce. Therefore,

the judgment of the Alabama Supreme Court was not

based on any Federal ground and leaves nothing for

this Court to review.

The action of the State o f Alabama to enjoin and

oust petitioner, a foreign corporation, which had vio

lated the Alabama corporation laws, was a well recog

nized exercise o f the police power of the State re

served to it by the Tenth Amendment.

No constitutional rights o f either the corporation

or its members were abridged by the commencement

of an action for injunction and ouster and the require

ment that the corporation produce records relevant to

the issues in that action.

It is respectfully submitted that the writ o f cert

iorari heretofore issued by this Court should be re

called or in the alternative the decision o f the Ala

bama Supreme Court should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

JOHN PATTERSON

Attorney General o f Alabama

MacDONALD GALLION

Assistant Attorney General of Alabama

EDMON L. RINEHART

Assistant Attorney General o f Alabama

Counsel For Respondent

JAMES W. WEBB

Assistant Attorney General o f Alabama

Of Counsel On Brief

32

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, Edmon L. Rinehart, one of the attorneys for the

respondent, The State of Alabama, and a member of

the Bar o f the Supreme Court of the United States,

hereby certify that on the J O ..............day o f October

1957, I served copies of the foregoing brief in opposi

tion on Arthur D. Shores, 1630 Fourth Avenue, North,

Birmingham, Alabama, by placing a copy in a duly

addressed envelope, with first class postage prepaid,

in the United States Post Office at Montgomery, Ala

bama, and on Thurgood Marshall, 107 West 43rd

Street, New York, New York, by placing two copies

in a duly addressed envelope, with Air Mail postage

prepaid, in the United States Post Office at Mont

gomery, Alabama.

I further certify that this brief in opposition is pre

sented in good faith and not for delay.

EDMON L. RINEHART

Assistant Attorney General of

Alabama

Judicial Building

Montgomery, Alabama

a ...... —<r-

o

V-