Bradley v. Milliken Sixth Circuit Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

October 13, 1970

24 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Bradley v. Milliken Sixth Circuit Court Opinion, 1970. ad9f2974-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b2cfe82f-1084-46ad-969a-71f90750a84f/bradley-v-milliken-sixth-circuit-court-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

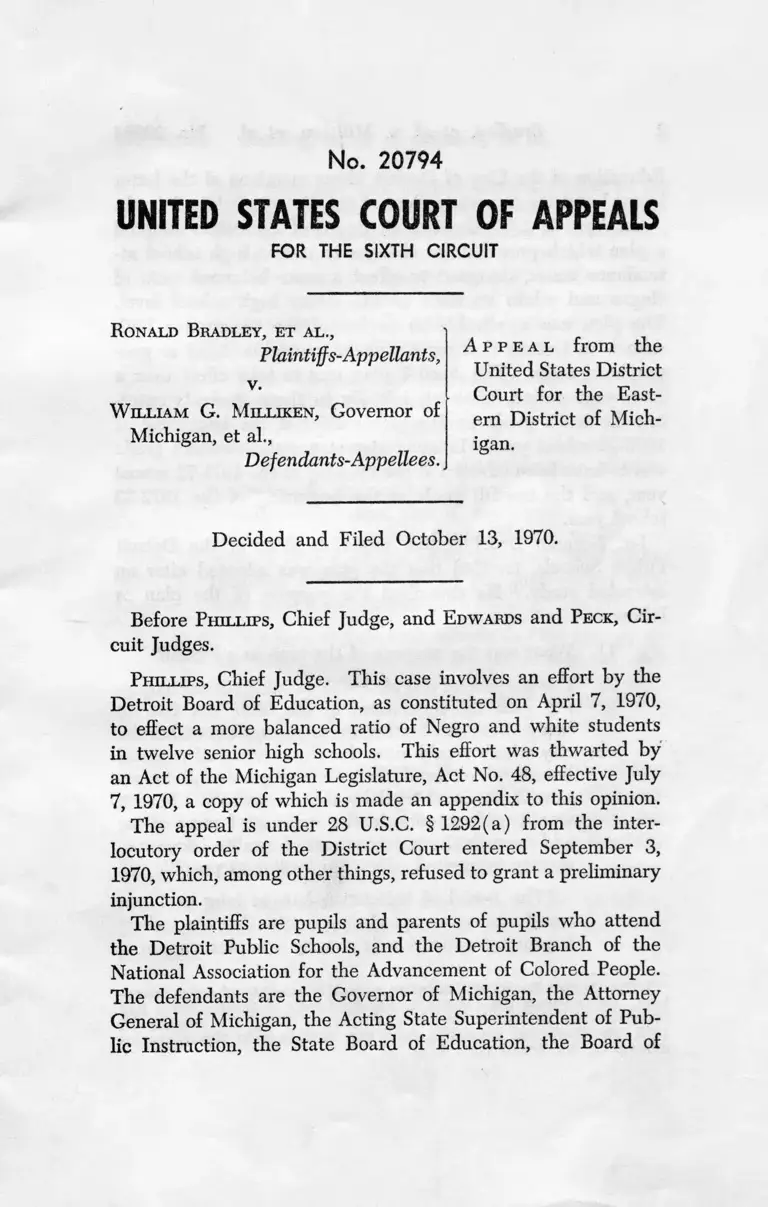

No. 20794

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Ronald Bradley, et a l .,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

W illiam G. Milliken, Governor of

Michigan, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Decided and Filed October 13, 1970.

Before Phillips, Chief Judge, and E dwards and Peck, Cir

cuit Judges.

Phillips, Chief Judge. This case involves an effort by the

Detroit Board of Education, as constituted on April 7, 1970,

to effect a more balanced ratio of Negro and white students

in twelve senior high schools. This effort was thwarted by

an Act of the Michigan Legislature, Act No. 48, effective July

7, 1970, a copy of which is made an appendix to this opinion.

The appeal is under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a) from the inter

locutory order of the District Court entered September 3,

1970, which, among other things, refused to grant a preliminary

injunction.

The plaintiffs are pupils and parents of pupils who attend

the Detroit Public Schools, and the Detroit Branch of the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

The defendants are the Governor of Michigan, the Attorney

General of Michigan, the Acting State Superintendent of Pub

lic Instruction, the State Board of Education, the Board of

A p p e a l from the

United States District

Court for the East

ern District of Mich

igan.

2 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. No. 20794

Education of the City of Detroit, three members of the latter

board,1 and the Superintendent of the Detroit Public Schools.

On April 7, 1970, the Detroit Board of Education adopted

a plan which provided for changes in twelve high school at

tendance zones, designed to effect a more balanced ratio of

Negro and white students at the senior high school level.

The plan was applicable to twelve of the twenty-one high

schools in Detroit that serve particular neighborhood or geo

graphical areas. The April 7 plan was to take effect over a

three-year period, applying initially to those students enter

ing the tenth grade in September 1970 at the beginning of

1970-71 school year. In successive stages the eleventh grade

was to have been affected at the opening of the 1971-72 school

year, and the twelfth grade at the beginning of the 1972-73

school year.

Dr. Norman Drachler, the Superintendent of the Detroit

Public Schools, testified that the plan was adopted after an

extended study. He described the purpose of the plan as

follows:

“Q What was the purpose of the plan as adopted?

“A The purpose of the plan was, in addition to comply

ing with the regulations of the State Act 244, to

bring about a decentralized school system within the

city which would allow for the election of regional

boards which would bring about greater participa

tion at the local level by the community. That it

would undoubtedly, in the opinion of most of us,

add towards the improvement of quality education,

quality integrated education insofar as possible.

“The Board of Education has, as long as I can

recall, always accepted the premise that the task of

improving education is a very complex one in a

1 The Detroit Board of Education normally consists of seven mem

bers. At the time the complaint was filed four of the members had

been recalled in an election held August 4, 1970. On August 31,

1970, the Governor appointed four new members to the vacancies

created by the recall vote.

No. 20794 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. 3

large city, but they have consistently held to the

premise that wherever possible, wherever reason

ably we can bring about integration in the process

of developing our educational program, that this

would enhance the opportunity of all children, black

and white, both in terms of their educational

achievement as well as their potential as responsi

ble citizens in a democracy.

“So in this plan the Board saw an opportunity, the

majority, that we could at the high school level

in some twelve high schools bring about over a

three-year period a certain amount of integration

although it involved only the movement of some

ten to twelve thousand children over the three-year

period, nevertheless, that is, the transfer of 12,000

children in three years — nevertheless these children

were in twelve schools which involved about 35,000

students, which is over 50 per cent of our total

high school enrollment.

“We have certain high schools that are already in

tegrated. Thus, we saw this as a step not only

toward achieving a goal of the decentralization

act but also the broader goal which the Board has

always had of quality integrated education.”

The Board of Education adopted the plan by a vote of four

to two, with one member absent because of illness. This sev

enth member, who is represented to have favored the plan but

was unable to vote, has since died and his vacancy has been

filled.

At the time the April 7 plan was adopted, Dr. Drachler,

the Superintendent of Public Schools, issued the following

statement:

“As an educator I support the proposed plan because

I believe that it is educationally, morally and according to

our attorney legally sound. Most of the research and

4 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. No. 20794

scholarship , both by blacks and whites that I respect,

supports the view that integration, racial, religious and

economic, has a positive effect on the learning of all

children in a pluralistic society. As a student of Ameri

can educational history I recognize that the above goal

has been the dream of our nation for over a century.

Local, state and national polls assert that the majority

of our people concur with the desirability of integration

and believe that eventually it will be a reality in our

nation.

“Let us, therefore, have a plan for self renewal of

our schools and our community rather than drift in the

climate of uncertainty, fear and frustration. I recog

nize that our primary objective as teachers is quality

education but to repeat, the majority of accepted research

and scholarship asserts that quality education in a hetero

geneous society such as ours can not be attained to its

fullest measure without integration. It is essential for

white and black, for poor and rich.

“This plan directly affects only our high school stu

dents. Without it each constellation will continue a

growing pattern of segregated racial or economic en

claves and be concerned only with the educational wel

fare of its own immediate area. This proposal, however,

encourages a broader community concern for educational

improvement and assures greater interest and support for

quality education for tens of thousands of children

wherever they attend school.

“Since as a people we concur with the necessity for

eliminating religious, racial and economic barriers, let

us, therefore, begin with a plan, however limited it is, let

us begin where we are and move forward.

“America has been willing to deprive itself of bil

lions of dollars to travel 250,000 miles in space to reach

the moon, I am confident Detroiters will be willing to

accept the idea of traveling one or two additional miles

to school for the sake of a better education for our young

people and for a better future for our city.”

The plan was approved by the Michigan Association for

Supervision and Curriculum Development by the following

resolution:

“Whereas racial integration is legally, morally and sci

entifically right, and Whereas, the President of the United

States has stated that ‘quality is what education is all

about’ desegregation is vital to that quality, and, Where

as, the Board of Education of the Detroit Public Schools

has approved a plan for high school students which effec

tively increases racial integration, therefore, Be It Re

solved, that the Michigan Association for Supervision

and Curriculum Development recognizes, endorses and

vigorously supports this long needed and forward step for

the future of America.”

The plan was endorsed by other national and local agencies

and organizations, including the United States Office of Edu

cation, the defendant Michigan State Board of Education and

the Michigan Civil Rights Commission.

Following adoption of the plan on April 7, 1970, Detroit

School officials began to prepare procedures to carry it into

effect at the beginning of the 1970-71 school year.

The Michigan Legislature enacted, and on July 7, 1970, the

Governor of Michigan signed into law, Act No. 48, Public

Acts of 1970.

Section 12 of this Act is as follows:

“Sec. 12. The implementation of any attendance pro

visions for the 1970-71 school year determined by any first

class school district board shall be delayed pending the

date of commencement of functions by the first class

school district boards established under the provisions

of this amendatory act but such provision shall not impair

the right of any such board to determine and implement

prior to such date such changes in attendance provisions

as are mandated by practical necessity. In reviewing,

confirming, establishing or modifying attendance pro

visions the first class school district boards established

No. 20794 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. 5

6 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. No. 20794

under the provisions of this amendatory act shall have

a policy of open enrollment and shall enable students

to attend a school of preference but providing priority

acceptance, insofar as practicable, in cases of insufficient

school capacity, to those students residing nearest the

school and to those students desiring to attend the school

for participation in vocationally oriented courses or other

specialized curriculum.”

By its terms this statute applies only to “first class school

districts.” The Detroit School system is the only “first class

school district” in Michigan. Although on its face the statute

is a general Act, it is applicable only to one local school

system in the State.2

Following enactment of Act 48, the Superintendent of De

troit City Schools requested an opinion from the attorney for

the Board of Education as to the effect of this statute. This

opinion, dated July 28, 1970, contains the following language

with respect to § 12:

“The answer to this question is found in Section 12 of

Act 48. Section 12 says:

‘The implementation of any attendance provisions

for the 1970-71 school year determined by any first

class school district board shall be delayed pending

the date of commencement of functions by the first

class school district boards established under the

provisions of this amendatory act * # V

“This quoted portion of Section 12 obviously, albeit in

directly, addresses itself to the action taken by the Board

on April 7, 1970, with respect to establishing new high

2 Since the statute is local in application, it is conceded by all

parties that its constitutionality can be determined by a one-judge

District Court and by this Court on appeal, and that it is not

necessary to convene a three-judge District Court under 28 U.S.C.

§ 2281. Moody v. Flowers, 387 U.S. 97; Griffin v. County School

Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218, 227; Rorick et al. v.

Board of Comm’rs of Everglades Drainage Dist. et al., 307 U.S. 208,

212.

school attendance areas. In our opinion, the effect of

this provision is to rescind — for at least one year —

the attempt made by the Board of Education on April

7, 1970, to achieve integration in its high schools. While

Act 48 itself purports only to delay implementation until

January 1, 1971, it is well known that no implementation

begun even on January 1, 1971, could be placed into op

eration earlier than the beginning of the Fall semester in

September, 1971. For these reasons we deem it un

necessary to recommend that the Board’s action on Ap

ril 7, 1970, establishing high school attendance areas be

rescinded.”

Further, a movement was initiated by certain Detroit

voters to recall the four members of the Detroit School Board

who had voted in favor of the April 7, 1970, plan. The re

call movement was resolved at the August 4, 1970, election,

which resulted in the recall and removal from office of the

four board members who voted in favor of the April 7 plan.

As stated in footnote 1, these four positions were vacant at

the time the complaint was filed and on August 31, 1970,

were filled by appointment by the Governor.

In accordance with the opinion of the attorney for the Board

of Education quoted above, Detroit school officials did not

put the April 7 plan into effect for the 1970-71 school year

beginning in September 1970. The Superintendent of City

Schools testified that he instructed regional superintendents

that “we had to go back to the plan of April 6.” The princi

pals of the affected high schools sent out letters or otherwise

notified students that regardless of any previous instructions

to the contrary, they should attend the high school they would

have attended prior to April 7. It is undisputed that, obedi

ent to the mandate of § 12 of Act 48, the plan adopted by

the Board of Education on April 7 has been suspended, or

at least deferred to a time beyond January 1, 1971. The high

schools in question have reverted to the attendance zones

which were in effect prior to the April 7 action of the Board.

No. 20794 Bradley, et a t v. Milliken, et a t 7

8

The tenth grade students who would have attended a high

school with an improved racial balance as determined by

the Board of Education on April 7 have been deprived of that

opportunity from the beginning of the 1970-71 school year

until the time of the rendering of this opinion.

On August 18, 1970, plaintiffs filed their complaint in the

present case as a class action, attacking the constitutionality

of § 12 of Act 48. Among other things the complaint prayed

for a preliminary injunction requiring defendants to put into

effect the plan adopted by the Detroit Board of Education on

April 7 and restraining defendants from giving any force or

effect to § 12 of Act 48 insofar as it would inhibit immediate

implementation of the Board’s plan of April 7.

District Judge Stephen J. Roth advanced the case and sched

uled a prompt hearing. Evidentiary hearings were conducted

by Judge Roth for three days on August 27-28, and Septem

ber 1, 1970. The testimony at these hearings comprises three

typewritten volumes. On September 3, 1970, Judge Roth re

leased a written opinion denying the application for a pre

liminary injunction and granting a motion to dismiss the Gov

ernor and Attorney General of Michigan as parties defendant.

The District Court did not pass upon the issue of the consti

tutionality of § 12 of Act 48.

The case was advanced on the docket of the District

Court for hearing on its merits beginning November 2, 1970.

The trial is scheduled to start on that date. Two weeks have

been ailoted by the District Court for this trial.

On September 3, the same day the decision of the District

Court was announced, defendants filed a notice of appeal and

a motion in this Court for injunction pending appeal. Oral

arguments on this motion were heard in Nashville, Tennessee,

by the Chief Judge of the Circuit September 8, 1970, pur

suant to Rule 8, Fed. R. App. P.3 The Detroit public schools

3 Rule 8 provides: “The motion . . . normally will be considered

by a panel or division of the court, but in exceptional cases where

such procedure would be impracticable due to the requirements of

time, the application may be made to and considered by a single

judge of the court.” s

Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. No. 20794

opened for the 1970-71 school term on September 8, the day

of the hearing before the Chief Judge in Nashville.

The Chief Judge entered an order denying the application for

injunction pending appeal and advanced the appeal for hearing

on its merits before this Court in Cincinnati, Ohio, on October

2, 1970, at 2 p.m. This opinion is rendered after considera

tion of the briefs and oral arguments of the parties and the

record and transcript of the evidence and proceedings in the

District Court.

Three questions will be disposed of at the present stage of

the proceeding:

(1 ) The issue of the constitutionality of § 12 of Act 48

(Appendix hereto);

(2 ) Whether the District Judge abused his discretion in

denying the application for a preliminary injunction;

(3 ) Whether the District Court erred in dismissing the

Governor and Attorney General as parties defendant.

1) The Michigan Statute

We first consider the issue of the constitutionality of the

statute.

As previously stated, the plan adopted by the Detroit Board

of Education was designed to provide a better balance between

students of the Negro and white races in twelve high schools.

If this plan had come into existence under a judgment of

the United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Michigan, there could be no question that § 12 of Act 48

would be void. The Legislature of a State cannot annul the

judgments nor determine the jurisdiction of the Courts of the

United States. United States v. Peters, 9 U.S. 115 (1809).

In the present case the April 7 plan came into being, not

as the result of a judgment of a District Court, out by the

voluntary action of the Detroit Board of Education in its effoit

further to implement the mandate of the Supreme Court in

Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483, 349 U.S. 294, and

No. 20794 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. 9

10 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. No. 20794

succeeding cases, such as Alexander v. Board o f Education,

396 U.S. 19, and Green v. County School Board o f Kent Coun

ty, 391 U.S. 430. The implementation of the April 7 plan was

thwarted by State action in the form of the Act of the Legis

lature of Michigan.

In numerous decisions the Supreme Court and other federal

courts have held that State action in any form, whether by

statute, act of the executive department of a State or local

government, or otherwise, will not be permitted to impede,

delay or frustrate proceedings to protect the rights guaranteed

to members of all races under the Fourteenth Amendment.

See:

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385, holding that the re

peal by referendum of the fair housing ordinance previously

adopted by the City Council of Akron, Ohio, “discriminates

against minorities, and constitutes a real, substantial, and invidi

ous denial of the equal protection of the laws.” 393 U.S. at 393.

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369, holding invalid a pro

vision of the Constitution of California, adopted by state-wide

referendum, which nullified previously enacted statutes regu

lating racial discrimination in housing and authorized “racial

discrimination in the housing market.” 387 U.S. at 381.

Griffin v. County Board o f Education o f Prince Edw ard

County, 377 U.S. 218, and cases cited therein, invalidating

the “massive resistence” legislation enacted by the Virginia

Legislature designed to prevent or delay school integration, and

requiring reopening of public schools of Prince Edwards

County.

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 9, nullifying a 1956 amendment

to the Constitution of Arkansas which commanded the Arkan

sas legislature to oppose “in every constitutional manner the

unconstitutional desegregation decisions” of the Supreme

Court, and various State statutes enacted for that purpose.

Kelley v. Board o f Education o f the City o f Nashville,

270 F.2d 209 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 361 U.S. 924, holding

a Tennessee statute authorizing separate segregated schools

No. 20794 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. 11

on a voluntary basis to be “patently and manifestly unconstitu

tional on its face.” 270 F.2d at 231.

L ee, et al. v. Nyquist, Commissioner o f Education o f the

State o f New York, (W.D. N.Y.) — F.Supp. — (three-judge

court, Sept. 29, 1970), which held invalid under the equal pro

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment § 3201(2) of the

New York Education Law, which “prohibits State education

officials and appointed school boards from assigning students,

or establishing, reorganizing or maintaining school districts,

school zones or attendance units for the purpose of achieving

racial equality in attendance.” ---- F.Supp. — .4

Keyes v. School District Number One, Denver, Colorado,

313 F.Supp. 61, 303 F.Supp. 279, and 303 F.Supp. 289 (D.

Colo.), 396 U.S. 1215, involving a school desegregation plan

adopted by a school board and an effort to rescind this plan

made by the same Board after changes in membership fol

lowing a school board election.

Holm es v. Leadbetter, 294 F.Supp. 991 (E.D. Mich.) en

joining a proposed referendum to submit an open housing

ordinance to voters of Detroit.

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 188 F.Supp. 916

(E.D . La.), aff’d, 365 U.S. 569, holding invalid twenty-five

measures adopted by the Louisiana Legislature in an effort to

circumvent partial desegregation of New Orleans public

schools.

Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F.Supp. 944 (E.D. Ark.), affd,

sub nom Faubus, Governor v. Aaron, 361 U.S. 197, holding

unconstitutional two Arkansas statutes authorizing the Gov

ernor to close schools and to call for school district elections

on the question of whether schools in such districts be inte

grated, and withholding State school funds from districts in

which schools have been closed because of integration.

The foregoing are a few cases selected from the many de

4 The case of North Carolina State Board of Education v. Swann,

involving the validity of the North Carolina anti-busmg law, is now-

pending before the Supreme Court of the United States. U.S.L.W. 3U6.

12 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. No. 20794

cisions holding that State action cannot be interposed to de

lay, obstruct or nullify steps lawfully taken for the purpose

of protecting rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

Defendants assert that § 12 is a valid exercise of legisla

tive power. It is true that, as a general rule, a State legisla

ture has plenary power over the arms and instrumentalities

of State government, including local boards of education. This

power cannot be exercised, however, so as to deprive indi

viduals of constitutionally protected rights. Gomillion v. Light-

foot, 364 U.S. 339, distinguishing Trenton v. New Jersey, 262

U.S. 182, Hunter v. Pittsburgh, 207 U.S. 161, and related cases.

Mr. Justice Frankfurter, speaking for the Court in Gomillion,

said:

“When a State exercises power wholly within the do

main of state interest, it is insulated from federal judicial

review. But such insulation is not carried over when

state power is used as an instrument for circumventing

a federally protected right. This principle has had many

applications. It has long been recognized in cases which

have prohibited a State from exploiting a power ac

knowledged to be absolute in an isolated context to jus

tify the imposition of an unconstitutional condition/ What

the Court has said in those cases is equally applicable

here, viz., that ‘Acts generally lawful may become un

lawful when done to accomplish an unlawful end, United

States v. Reading Co., 226 U. S. 324, 357, and a consti

tutional power cannot be used by way of condition to

attain an unconstitutional result/ W estern Union T ele

graph Co. v. Foster, 247 U. S. 105, 114.” 364 U.S. at 347.

Defendants rely upon the decision of this Court in D eal v.

Cincinnati Board o f Education, 369 F.2d 55, cert, denied,

389 U.S. 847, 419 F.2d 1387 (6th Cir.). D eal is distinguish

able on its facts from the present case. In D eal this Court

held that the school board of a long-established unitary non-

racial school system had no constitutional obligation to bus

No. 20794 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. 13

white and Negro children away from districts of their resi

dences in order that racial complexion be balanced in each

of the many public schools in the City. In the present case

the Detroit Board of Education in the exercise of its discre

tion took affirmative steps on its own initiative to effect an

improved racial balance in twelve senior high schools. This

action was thwarted, or at least delayed, by an act of the

State Legislature. No comparable situation was presented in

Deal.

Defendants defend the constitutionality of the second sen

tence of §12 of Act 44 on the ground that the word “shall,”

which appears twice in that sentence, was intended to mean

“may,” and that the sentence is not mandatory. We reject

this interpretation of the sentence. We find nothing in the

Act to indicate any intention on the part of the Legislature

to leave the application of this sentence to the discretion

of local school officials. We are cited to nothing in the leg

islative history to support such an interpretation. The word

“shall” is ordinarily “the language of command.” Anderson v.

Yungkau, 329 U.S. 482, 485; Escoe v. Zerbst, 295 U.S. 490,

493. We interpret the word “shall” in the second sentence of

§ 12 as meaning precisely what the Michigan legislature said.

We conclude that this sentence was enacted with the intention

that it be mandatory.

We hold § 12 of Act 48 to be unconstitutional and of no

effect as violative of the Fourteenth Amendment. By this

ruling on the invalidity of § 12, we express no opinion at the

present stage of the case as to the merits of the plan adopted

by the School Board on April 7, 1970, or as to whether it

was the constitutional obligation of the School Board to adopt

all or any part of that plan.

2) Denial of Preliminary Injunction

Although holding that § 12 of Act 48 is unconstitutional,

we cannot say that the District Judge abused his discretion

in refusing to grant a preliminary injunction upon the basis

of the evidence introduced during the three days of hear-

ings.

The granting or denial of a preliminary injunction pending

final hearing on the merits is within the sound judicial discre

tion of the District Court. On appeal, the action of the

District Court denying a preliminary injunction will not be

disturbed unless contrary to some rule of equity or result of

improvident exercise of judicial discretion. Nashville 1-40

Steering Com m ittee v. Ellington, 387 F.2d 179 (6th Cir.), cert,

denied, 390 U.S. 921.

The complaint in the present case seeks relief going be

yond the scope of the plan of April 7, 1970, and Act 48,

such as the assignment of teachers, principals and other school

personnel to each school in accordance with the ratio of

white and Negro personnel throughout the Detroit school

system, and an injunction against all future construction of

public school buildings pending Court approval. As previously

stated, the District Judge not only conducted an expeditious

hearing on the application for a preliminary injunction, but

has advanced the case on his docket to November 2, 1970,

and allotted two weeks for the trial.

We conclude that the issues presented in this case, in

volving the public school system of a large city, can best

be determined only after a full evidentiary hearing.

In the trial of the case on its merits, the District Judge is di

rected to give no effect to § 12 of Act 48, because of its uncon

stitutionality.

3) The Governor and Attorney General as parties defendant

Defendants appeal from the order of the District Court dis

missing the Governor and Attorney General of Michigan as

parties defendant. We hold that the Governor and Attorney

General are proper parties, at least at the present stage of

the proceeding. Compare: Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U.S.

378, 393; Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123, 157, 161; Arneson v.

14 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. No. 20794

No. 20794 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. 15

Denny, 25 F.2d 993 (W.D. W ash.); Jam es v. Almond, 170 F.

Supp. 331, 341-42 (E.D. Va.), appeal dismissed, 359 U.S. 1006;

Bevins v. Prindable, 39 F.Supp. 708, 710 (E.D . 111.), aff’d,

314 U.S. 573.

That part of the order of the District Court dismissing

the Governor and Attorney General of Michigan as parties de

fendant is reversed.

Affirmed in part, reversed in part and remanded to the

District Court for further proceedings not inconsistent with

this opinion.

16 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. No. 20794

A P P E N D I X

TEXT OF ACT 48 - PUBLIC ACT OF 1970

Approved by the Governor — July 7, 1970

State of Michigan — 75th Legislature — Regular Session of 1970

An Act to amend the title and sections 4, 5, 6 and 7 of Act

No. 244 of the Public Acts of 1969, entitled “An act to re

quire first class school districts to be divided into regional

districts and to provide for local district school boards and

to define their powers and duties and the powers and duties

of the first class district board,” being sections 388.174, 388.175,

388.176 and 388.177 of the Compiled Laws of 1948; to add

sections la , 2a, 3a and 8 to 13; and to repeal certain acts and

parts of acts.

The People of the State of Michigan enact:

Section 1. The title and sections 4, 5, 6 and 7 of Act No.

244 of the Public Acts of 1969, being sections 388.174, 388.-

175, 388.176 and 388.177 of the Compiled Laws of 1948, are

amended and sections la , 2a, 3a and 8 to 13 are added to

read as follows:

TITLE

An act to require first class school districts to be divided

into regions and to provide for regional boards and to define

their powers and duties and the powers and duties of the

first class district board.

Sec. la. On or after January 1, 1971, in any first class

school district with more than 100,000 student membership,

the board membership of the board of education shall be

composed of 8 members determined and elected as provided

in section 2a plus 5 members determined and elected as pro

vided in section 3a.

No. 20794 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. 17

Sec. 2a. Immediately following the effective date of this

1970 amendatory act or any date on which a school district

becomes a first class school district, 8 regions shall be described

in each such first class school district by resolution concurred

in by three-fourths of the members elected and serving in each

House of the legislature and such regions so described shall

be established as regions if and when approved by the super

intendent of public instruction. If a concurrent resolution

shall not be approved by three-fourths of such members

within 7 days of the effective date of this amendatory act

or within 30 days of any date on which a school district

becomes a first class school district a first class district boundary

commission consisting of 3 members appointed by the gov

ernor shall determine the boundary lines of such regions

within 21 days thereafter if in 1970 or within 30 days there

after if in any later year. The members of the commission

shall receive a compensation of $100.00 per diem per member

from the funds appropriated to the department of education.

The boundary lines of such regions shall be redetermined by

the respective boards of such first class school districts fol

lowing each federal decennial census but in no event later

than April 15 of the first odd numbered year in which regional

board members are to be elected following the federal decenni

al census. In the event of the failure of such respective boards

of such first class school districts to redetermine such regional

boundary lines by such April 15, the state board of education

shall convene within 10 days to make such redetermination

and such redetermination of the state board of education shall

be the regional boundary lines until the redetermination is

made following the next succeeding federal decennial census

as provided in this section. Regions shall be as compact, con

tiguous and nearly equal in population as practicable.

Within each region, there shall be a regional board con

sisting of 5 members. The members shall be nominated

and elected by the registered and qualified electors of each

district as is provided by law for the nomination and election

18 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. No. 20794

of first class school board members except that signatures

required on nominating petitions shall be not less than 500

nor more than 1,000. Any candidate properly filed for any

educational position in any first class school district as of the

effective date of this act shall be considered as a qualified

candidate under sections 2a and 3a for the 1970 election pro

vided such candidate makes a request, designation and selec

tion to the election officer empowered by law to accept nom

inating petitions for such office. No person shall be elected

who is not a resident of the region from which he is elected.

The members shall be elected in the general election to be

held in November, 1970 and November of 1973 and every 2

years thereafter commencing in 1975.

In the year 1970 regional board members shall be elected

in the November general election and candidates for such

offices shall not be subject to the primary election. In 1970

a person may qualify as a candidate for the election for regional

board member by filing the required number of signatures

on or prior to 4 p.m., August 18, 1970. In 1970 signatures

of registered electors of the first class district shall be valid

without regard to the place of residence of such registered

elector. In any year the candidate for regional board mem

ber receiving the highest number of votes in each region in

the November general election shall be chairman of the regional

board and a member of the board of education of his first

class school district during his term of office. In case a

vacancy occurs for any reason in the combined position of

chairman of the regional board and member of the first class

school district board of education, the regional board mem

ber who received the next highest number of votes in the

preceding general election shall assume such combined po

sition. The number of members of each regional board shall

be maintained at 5 and vacancies shall be filled from among

residents of the region by the remaining board members of

such region by a majority vote of those serving. No vacan

cies shall be filled later than 60 days prior to a primary elec

No. 20794 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. 19

tion at which regional board members are to be nominated.

The 5 regional board members elected in each region shall

commence their terms of office on January 1 following the

election and the members shall serve until their successors are

elected and qualified.

Sec. 3a. Effective January 1, 1971 there shall be 5 members

on the boards of first class school districts elected at large.

Members of such boards shall be nominated and elected at

the primary and general elections of 1972 and 1974 for 3-

year terms commencing on January 1 of the subsequent odd

number year, 2 each to be elected in 1972 and 1974. In

the year 1970 1 board member shall be elected in the Novem

ber general election for a 3-year term commencing January

1, 1971 and candidates shall not be subject to the primary

election. In 1970 a person may qualify as a candadate for

the election for first class school district board member by

filing nominating petitions containing not less than 500 nor

more than 1,000 valid signatures on or before 4 p.m., August

18,1970. Commencing in 1973 and in all subsequent odd num

bered years, a number of board members equivalent to the

number of members whose terms expire on December 31

of such year will be nominated and elected at the primary

and general election. Such members so elected shall serve

2-year terms commencing on January 1 of the subsequent even

numbered year. To accomplish the provisions of this amenda

tory act the terms of office of any first class district board

members whose terms expire prior to December 31, 1971

shall expire December 31, 1970; the terms of office of such

board members whose terms expire between January 1, 1972

and December 31, 1973 shall expire December 31, 1972 and

the terms of office of such board members whose terms ex

pire between January 1, 1974 and December 31, 1975 shall

expire December 31, 1974.

In any year in which one or more board members of a

first class district are commencing a term of office on January

1 the board of such first class district shall redetermine its

20 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. No. 20794

selection of officers during the month of January of such year.

Petitions to recall any member or members of the board of

education of a first class school district filed and pending

before this act becomes effective, or becomes operative in

a school district that hereafter becomes a first class school

district, may be withdrawn by the person or organization filing

or sponsoring such recall petitions within 10 days after this

act becomes effective or 20 days after the act becomes op

erative in any school district that hereafter becomes a first

class school district. Board members of first class school

districts who are recalled in accordance with law may be

candidates for the same office at the next election for such

office at which the recalled member is otherwise eligible. In

the case of any school district that hereafter becomes a first

class school district, the term of office of each of the board

members then serving in such school district shall expire on

the next succeeding December 31 of an odd numbered year,

provided however that if the school district becomes a first

class school district later than April 1 of an odd numbered year,

the term of office of each of its board members shall expire

on December 31 of the next succeeding odd numbered year

later than the year in which the district became a first class

school district. For any district becoming a first class district

5 school board members shall be elected in the general election

of the odd numbered year in which such terms of office ex

pire and the 5 school board members so elected shall com

mence 2-year terms on January 1 of the even numbered year

following such general election.

In case a vacancy occurs for any reason on the first class

district board such vacancy shall be filled by majority vote

of all persons serving as regional board and first class district

board members at a meeting called by the president of the first

class district board for such purpose. No vacancies shall

be filled later than 60 days prior to a primary election at

which first class district board members are to be nominated.

Vacancies which shall occur prior to the effective date of

No. 20794 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. 21

this act or have occurred in 1970, shall be filled for a term

ending December 31, 1972 in the same manner as provided

in this section for the election of board members at large in

the year 1970 and such positions shall then be filled in the

primary and general election of 1972 for a 3 year term. In

1970 the candidate receiving the highest number of votes

shall be elected for the 3 year term and the candidates re

ceiving the next highest number of votes shall be elected for

2 year terms to fill vacancies.

Sec. 4. A candidate for a regional board must be 21 years

of age at the time of filing and must reside in the region in

which he becomes a candidate. If his legal residence is moved

from the region during his term of office, it shall constitute

a vacating of office.

Sec. 5. The first class school district board shall retain

all the powers and duties now possessed by a first class school

district except for those given to a regional board under

tile provisions of this act and such other functions as are dele

gated to the regional boards by the first class school district

board.

Sec. 6. Effective upon the commencement of its term of

office, the regional board, subject to guidelines established

by the first class district board, shall have the power to:

(1 ) Employ a superintendent for the schools in the region

from a list or lists of candidates submitted by the first class

district board and to discharge any such regional superin

tendent.

(2 ) Employ and discharge, assign and promote all teach

ers and other employees of the region and schools therein

subject to review by the first class school district board, which

may overrule, modify or affirm the action of the regional

board.

(3 ) Determine the curriculum, use of educational facilities

and establishment of educational and testing programs in

the region and schools therein.

22 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et a t No. 20794

(4 ) Determine the budget for the region and schools

therein based upon the allocation of funds received from the

first class school district board.

Sec. 7. The rights of retirement, tenure, seniority and of

any other benefits of any employee transferred to a region or

schools therein from the first class district or transferred be

tween regions shall not be abrogated, diminished or impaired.

Sec. 8. The first class school district board shall perform

the following functions for the regions and schools therein:

(1 ) Central purchasing.

(2 ) Payroll.

(3 ) Contract negotiations for all employees, subject to the

provisions of Act No. 336 of the Public Acts of 1947, as amend

ed, being sections 423.201 to 423.216 of the Compiled Laws of

1948, and subject to any bargaining certification and to the

provisions of any collective bargaining agreement pertaining to

affected employees.

(4 ) Property Management and Maintenance

(5 ) Bonding

(6) Special education programs.

(7 ) Allocation of funds for capital outlay and operations

for each region and schools therein.

(8 ) Establish or modify guidelines for the implementation

of the provisions of section 6. Such guidelines shall include

but not be limited to the determination and specification

of each regional board’s jurisdiction and may provide for

regional board’s jurisdiction over schools not geographically

located within their respective regions.

Sec. 9. Facilities and accomodations provided by the first

class school district board for regional boards shall be selected

with due consideration for accessibility, economy and utiliza

tion of existing facilities. Employees assigned by the first

class school district board to regional boards at the time of

commencement of their functions shall be drawn, to the extent

feasible, from persons employed at such time by the first class

school district.

No. 20794 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. 23

Sec. 10. Regional board members shall be paid a per diem

allowance of $20.00 for each meeting of their board attended

and first class district board members shall be paid a per

diem allowance of $30.00 for each meeting of their board

attended, but in neither case shall such payments be for meet

ings in excess of 52 meetings per annum. The chairman of

each regional board shall be paid for up to 52 regional board

meetings attended and up to 52 first class district board meet

ings attended.

Sec. 11. First class school districts with 100,000 student

membership or more shall have the same rights for initiative

petition and referendum now granted by law to second and

third class districts.

Sec. 12. The implementation of any attendance provisions

for the 1970-71 school year determined by any first class school

district board shall be delayed pending the date of com

mencement of functions by the first class school district boards

established under the provisions of this amendatory act but

such provision shall not impair the right of any such board

to determine and implement prior to such date such changes

in attendance provisions as are mandated by practical necessity.

In reviewing, confirming, establishing or modifying attendance

provisions the first class school district boards established under

the provisions of this amendatory act shall have a policy of

open enrollment and shall enable students to attend a school

of preference but providing priority acceptance, insofar as

practicable, in cases of insufficient school capacity, to those

students residing nearest the school and to those students

desiring to attend the school for participation in vocationally

oriented courses or other specialized curriculum.

Sec. 13. If any portion of this act or the application there

of to any person or circumstance shall be found to be in

valid by a court, such validity shall not affect the remaining

portions or applications of this act which can be given effect

without the invalid portion or application, and to this end

this act is declared to be severable.

24 Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. No. 20794

Section 2. Sections 1, 2 and 3 of Act No. 244 of the Public

Acts of 1969, being sections 388.171, 388.172 and 388.173 of the

Compiled Laws of 1948, are repealed.

This act is ordered to take immediate effect.