Garner v. Louisiana Motion for Leave to File Brief and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Garner v. Louisiana Motion for Leave to File Brief and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1961. 8ee1e3d3-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b2d35e23-8052-4868-9537-0f1d3a90bafd/garner-v-louisiana-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

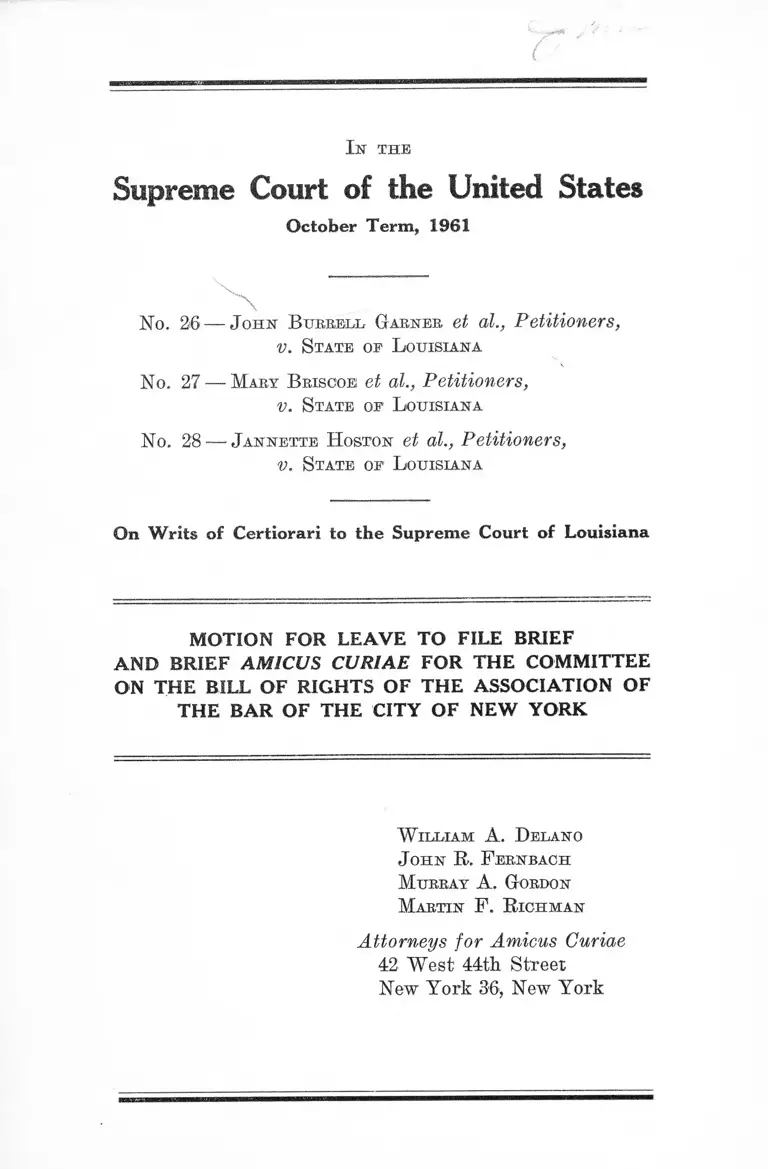

I n t h e

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1961

No. 2 6 — J ohn Burrell Garner et al., Petitioners,

v. State of L ouisiana

No. 27 — Mary B riscoe et al., Petitioners,

v. State of L ouisiana

No. 28-— J annette H oston et al., Petitioners,

v, State of L ouisiana

On Writs of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Louisiana

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF

AND BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE FOR THE COMMITTEE

ON THE BILL OF RIGHTS OF THE ASSOCIATION OF

THE BAR OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK

W illiam A. Delano

J ohn R. F ernbach

Murray A. Gordon

Martin F . B ichman

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

42 West 44th Street

New York 36, New York

I n t h e

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1961

No. 26 — J ohn B urrell Garner et al., Petitioners,

v. State oe Louisiana

No. 27 — Mary B riscoe et al., Petitioners,

v. State of Louisiana

No. 28 — J annette H oston et al., Petitioners,

v. State of L ouisiana

On Writs of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Louisiana

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

FOR THE COMMITTEE ON THE BILL OF RIGHTS OF

THE ASSOCIATION OF THE BAR OF THE

CITY OF NEW YORK

To the Chief Justice and the Associate Justices of the

Supreme Court of the United States:

This motion of the Committee on the Bill of Rights of

The Association of the Bar of the City of New York for

leave to file the annexed brief amicus curiae is made pur

suant to Rule 42, consent to the filing of a brief having

been withheld by respondent.

2

The Association of the Bar of the City of New York,

presently comprised of more than 7,000 lawyers admitted

to practice in the State of New York, has since its organi

zation in 1871 been active in expressing and implementing

considered views on local, state and national matters affect

ing the law and the legal profession. These functions of

the Association are generally performed through a com

mittee responsible for the relevant subject-matter, acting

by means of resolutions, reports, testimony before legisla

tive committees and, on occasions when issues of paramount

importance and special interest to the Bar are involved, as

here, by participation as amicus curiae in pending litiga

tion. The Association’s Committee on the Bill of Rights

is charged by the By-Laws of the Association with responsi

bility for matters relating to those provisions of the United

States Constitution “ which are directed at protecting the

individual against oppression by government.”

The grant of certiorari by the Court in these cases

emphasizes the fact that they evoke questions of national

significance considerably beyond the usual implications of

local prosecutions of individuals for “ disturbing the

peace.” Directly involved here is the question whether a

State denies the equal protection of the laws, within the

purview of the Fourteenth Amendment, by the arrest and

conviction of persons (in these cases, Negroes) for peace

ably seeking service of food on a non-discriminatory basis

in commercial establishments open to the public. Although

other questions and arguments are being advanced by

petitioners, the Committee on the Bill of Rights believes

—and has limited the annexed brief amicus curiae accord

ingly—that the decision of the Court should meet squarely

the issue presented here of State enforcement of racial

discrimination in such commercial establishments. If it

does not do so, the present uncertainty as to the applicable

law will continue to invite testing by persons on both sides

of the issue, with resulting harm to the communities in

volved and to the Nation.

3

This Committee also considers that these cases raise

fundamental questions concerning the judicial power and

function. Courts traditionally are empowered to act where

conflicts extend to an area of cognizable property rights.

However, Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948), estab

lishes that no organ of the State, and more particularly its

judiciary, may serve as the instrument of constitutionally

prohibited racial discrimination. An underlying issue here

is whether the holding in Shelley should be departed from

in these cases because they arise in a context of potential

community tension. This committee of lawyers particu

larly concerned with effectuation of the protections of the

Constitution for individual freedom has a concrete interest

as amicus curiae in cases which thus appear likely at least

to illumine, and perhaps to define, a vital aspect of the

scope of the judicial function and power within the limita

tions of the Constitution.

W herefore, i t is respectfully prayed th a t this motion

for leave to file the annexed brief amicus curiae be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

W illiam A. Delano

J ohn R. F ernbach

Murray A. Gordon

Martin F . R ichman

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

I N D E X

Interest of Amicus Curiae .......................................... 1

Question Presented ..................................................... 2

Statement ...................................................................... 3

Summary of Argument................................................ 7

Argument ...................................................................... 8

I ........................................................................... 9

I I ........................................................................... 13

H I ................................................................... 17

Conclusion.... ................... 20

PAGE

CITATIONS

Cases

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (5th. Cir. 1961) ...... 13,16

Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 U. S. 877 (1955) ................. 11

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 (1953) ...................10,11

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531 (5th

Cir. 1960) ........................................................ 12,15,18

Boman v. Morgan, 4 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1027 (1ST. D.

Ala. 1959) .......................... .................................... 16

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454 (1960) .................16,18

Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U. S. 622 (1951) ................. 18

[ i ]

[ i i ]

Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala, 1956) ..11,15

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) .... 11

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917) ...................101, 12

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 (1961) ...........................................................9', 10,17

California Inter-Insurance Bureau v. Maloney, 341

U. S. 105 (1951) .................................................... 14

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 (1883) ...................... 10,13

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) ............................ 19

Flemming v. South Car. Elec. & Gas Co., 239 F. 2d

277 (4th Gir. 1956) ................................................ 15

Freeman v. Retail Clerks Union, 45 Lab. Bel. Ref.

Man. 2334 (Wash. Super. Ct. 1959) ..................... 14

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 (1956) ..........11,12,15', 16

Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 (1955) ..................... 11

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24 (1948) ............................ 10

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 (1946) ..........10,11,12,13

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 (1946) ................... 19

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 (1958) ................... 10

People v. Barisi, 193 Mise. 934, 86 N. Y. S. 2d 277

(Magis. Ct. 1948) .................................................. 14

San Diego Bldg. Trades Council v. Garmon, 359 IT. S.

236 (1959) .............................................................. 20

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) ........7, 9,10,11,12,

13,14,15, 20

State v. Williams, 44 Lab. Bel. Ref. Man. 2357 (Balti

more Crim. Ct. 1959)

PAGE

14

[ i i i 3

Takahashi v. Fish and Game Comm’n, 334 U. S. 410

(1948) .................................................................... 10

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 (1940) ................. 20

United States v. Parke, Davis & Go., 362 U. S. 29

(1960) .................................................................... 14

Statutes

42 U. S. C. §1982 ........................................................... 10

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27 .......................... 10

La. Rev. Stat. §14:103 (1950) ....................................... 3, 8

La. Rev. Stat. §§14:103, 14:103.1 (Supp. 1960) .......... 3

NT. C. Gen. Stats. §14-134 (1953) ................................... 9

Miscellaneous

Pollitt, “ Dime Store Demonstrations: Events and

Legal Problems of First Sixty Days,” 1960 Duke

L. J. 315 ................................................................ 9,14

Sehwelb, ‘ ‘ The Sit-In Demonstration: Criminal Tres

pass or Constitutional Right?” 36 N. Y. U. L.

Rev. 779 (1961) ..................................................... 19

New York Times, April 23, 1960, p. 21, col. 1 ............. 14

New York Times, June 6, 1960, p. 1, col. 2; June 24,

I960, p. 1, col. 6; July 25,1960, p. 1, col. 8; August

11, 1960, p. 14, col. 5; October 18, 1960, p. 47, col.

5; January 22, 1961, p. 72, col. 8; May 7, 1961,

§4, p. 10, col. 1 .......................................................

PAGE

19

I n t h e

Supreme Court ©f the United States

October Term, 1961

---------- a— ♦ — ------ ------

No. 26 — J ohn B urrell Garner et al., Petitioners,

v. State of Louisiana.

No. 27 — Mart Briscoe et al., Petitioners,

v. State of L ouisiana

No. 28 — .!annktte H oston et al., Petitioners,

v. State of L ouisiana

On Writs of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Louisiana

---------- » — ---------

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

FOR THE COMMITTEE ON THE BILL OF RIGHTS OF

THE ASSOCIATION OF THE BAR OF THE

CITY OF NEW YORK

Interest of Amicus Curiae

The interest of the Committee on the Bill of Rights of

The Association of the Bar of the City of New York as

amicus curiae and the reasons for submitting this brief

are set forth in the annexed Motion for Leave to File Brief.

2

Question Presented

This brief is addressed to the question whether a State

denies the equal protection of the laws by arresting and

convicting for disturbing the peace Negroes who peaceably

seek service by remaining seated at a lunch counter located

in a commercial establishment open to the public.

Statement

These cases have been brought here on writs of cer

tiorari to review convictions in a court of the State of

Louisiana of persons who were arrested for disturbing the

peace when they remained seated at public lunch counters

located in commercial establishments after being refused

food service because they were Negroes. These are the

first cases to bring before the Court the issue of State

enforcement of racial discrimination in the context of what

have come to be known as “ sit-ins.” A statement of the

facts relied on in the argument submitted in this brief of

amicus curiae is presented here for the convenience of the

Court, without intending to duplicate the statements of the

facts of the individual cases set forth in the briefs of the

parties.

In Garner, No. 26, the two petitioners are Negro men,

college students in Baton Rouge, Louisiana (R. 8). They

entered Sitman’s Drug Store in downtown Baton Rouge

on March 29, 1960, and sat down at the lunch counter

(R. 30). The owner told them they could not be served, but

one of them replied that they wanted coffee and both re

mained seated at the counter (R. 30). The policeman on

the beat was in the store at the time and he, apparently

without complaint from anyone else, called superior officers

from headquarters (R. 31, 34-35). The latter advised peti

tioners that they were violating the “ disturbing the peace”

3

law,* 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 and requested them to leave (R. 35). Petitioners

refused, and were arrested (R. 35-37).

The store owner testified that Negroes are served at the

counters in the drug store section of his establishment—he

said they “ are very good customers” (R. 32)—-but that he

does not “ have the facilities” for serving Negroes at the

lunch counter in the adjoining coffee shop section (R. 31-

32). One of the petitioners told the police officer he had

purchased an umbrella in the store (R. 35). When peti

tioners entered, at the noon hour, there were white cus

tomers seated at the counter, but the owner could not recall

how many (R. 33). No customers complained to him, he

did not speak to the police officers, and no one else com

plained to them (R. 33, 34-35).

1. The police captain in his testimony referred to “Act 103“

(R. 35). At the time of the events in question here, La. Rev. Stat.

§14:103 (1950) provided:

“Disturbing the peace is the doing of any of the following

in such a manner as would foreseeably disturb or alarm the

public:

(1) Engaging in a fistic encounter; or

(2) Using of any unnecessarily loud, offensive, or insulting

language; or

(3) Appearing in an intoxicated condition; or

(4) Engaging in any act in a violent and tumultuous man

ner by three or more persons; or

(5) Holding of an unlawful assembly; or

(6) Interruption of any lawful assembly of people; or

(7) Commission of any other act in such a manner as to

unreasonably disturb or alarm the public.

Whoever commits the crime of disturbing the peace shall

be fined not more than one hundred dollars, or imprisoned for

not more than ninety days, or both.”

Subsequently, the statutory definition of disturbing the peace was

expanded to deal more specifically with, inter alia, conduct like that

involved in the “sit-ins.” See La. Rev. Stat. §§14:103, 14:103.1

(Supp. 1960).

4

Tile police captain testified that he arrested petitioners

because he believed they were disturbing the peace “ by their

mere presence” at the lunch counter (E. 35-36). Thus, he

testified (E. 35):

“ A. Well, the only thing that I can say is, the law

says that this place was reserved for white people

and only white people can sit there and that was the

reason they were arrested.”

The trial court’s oral finding of guilt was based on the

fact that petitioners (E. 37)

“ were seated at the lunch counter in a bay where food

was served and they were not served while there, and

officers were called and after the officers arrived they

informed these two accused that they would have to

leave, and they refused to leave.”

Petitioners were each sentenced to 30 days in the parish

jail and to pay a fine of $100 or serve an additional 90 days

in jail (E. 41).

The petitioners in Briscoe, No. 27, five men and two wo

men, also Negro* college students in Baton Eouge (E. 8),

entered the Greyhound Bus Station in Baton Eouge on

March 29, 1960, took seats at the lunch counter, and started

ordering (E. 30). A waitress told them they would have

to go “ to the other side” to be served (E. 30-31). The po

lice were called, either by a bus driver or a woman em

ployee (E. 33, 34, 38). The police asked petitioners to get

up and leave (E. 35). They remained seated without speak

ing, but when placed under arrest went along peacefully

with the officers (E. 35-36).

The Bus Station has another eating place for colored

people (E. 32-34). The waitress testified that over the

counter at which she refused to serve petitioners was a sign

reading “ Eefuse service to anyone,” and that her under

5

standing of instructions from her superior was to refuse to

serve Negroes (R. 32-33). Petitioners did nothing other

than give their orders and continue to sit at the counter

(R. 32-33, 35, 37), and the only reason the waitress refused

to serve them was that they were Negroes (R. 31-32).

There were no* other people waiting to be served while

petitioners were sitting at the counter (R. 34).

The police captain stated that petitioners were arrested

for disturbing the peace by the “ fact that their presence

was there in the section reserved for white people” (R. 36).

Thus, he testified (R. 38):

“ Q. You requested them to move then because they

were colored, is that right, sitting in those seats?

“ A. We requested them to move because they were

disturbing the peace.

“ Q. In what way were they disturbing the peace?

“ A. By the mere presence of their being there.”

The trial court’s finding of guilt was similar to that in

the Garner case, which was tried on the same day (R. 38-

39). All the petitioners here received the same sentence

as those in Garner—30 days in jail and a fine of $100 or an

additional 90 days (R. 43-44).

Petitioners in Eoston, No. 28, are other Negro college

students in Baton Rouge (R. 7), five men and two women.

They entered the S. H. Kress and Company store in Baton

Rouge about two o’clock on March 28, I960 and sat down

at seats at various places along the lunch counter

(R. 29, 30). The manager told a waitress to advise them

that they would be served at another counter, across the

store, reserved for colored people (R. 29). Petitioners

continued to sit, and the manager called the police (R. 30).

The police officers asked petitioners to leave; one of them

said she wanted a glass of iced tea, but the Chief of Police

6

told her “ they were disturbing the peace and violating the

law by sitting there’’ (R. 36). When petitioners did not

move to get up, they were placed under arrest (R. 36).

The manager testified that “ it isn’t customary for the

two races to sit together and eat together” at the lunch

counter in the Kress store (R. 30, 34), but that it is custom

ary for white and colored persons to shop together else

where in the store (R. 31-32). There were Negroes in the

store at the time of this incident (R. 37). The manager

stated that petitioners were not served at the lunch counter

because it was “ not customary” to serve Negroes there,

and that petitioners did not do anything other than sit at the

counter which he would consider disturbing the peace

(R, 33).

The police captain also testified that petitioners did

nothing other than sit at these counter seats that he con

sidered disturbing the peace (R. 37). He arrested petition

ers on instructions of the Chief of Police, who had accom

panied him to the store (R. 36).

The finding of guilt by the trial court was similar to

that in the two preceding cases, with which this one was

tried (R. 38-39). The court noted that petitioners “ remain

ed seated at the counter which by custom had been reserved

for white people” until arrested (R. 391)- The jail sen

tences and fines of these petitioners were the same as in the

other two cases (R. 43-44).

Convictions in the three cases were sustained by the

Supreme Court of Lousiana in memorandum orders refus

ing writs with a statement that the rulings of law by the

trial court “ are not erroneous” (Garner R. 53, Briscoe R.

56, Boston R. 55-56).

7

Summary of Argument

Equal opportunity to purchase food in a place open to

the public is protected by the Fourteeenth Amendment

against infringement by State action based on race or

color. State courts may not, by civil or criminal sanctions,

enforce discriminations originating- in private conduct.

Here the arrests and convictions brought “ the full co

ercive power of government” (Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U. S. 1, 19 (1948)) to bear in support of discriminatory

refusals to serve petitioners at public lunch counters, for

it is clear in the records of these cases that petitioners were

arrested solely because they were Negroes peacefully at

tempting to be served.

The extent to which privately-owned property is af

fected by rights in others depends upon the extent to which

the owner has opened the property for use by the public.

Thus, State sanctions against the exercise of constitutional

rights on privately-owned property open to the public and

State-enforced segregation in privately-owned local trans

portation facilities have been held unconstitutional. In the

present cases, statutes of general applicability have been

applied to provide effective State participation in the en

forcement of racial discriminations by store proprietors.

The Fourteenth Amendment requires that peaceful ac

tivities by Negroes seeking equal treatment in normal

economic transactions in the circumstances presented here

be immune from coercive sanctions interposed by the police

or courts of a State. These cases involve nothing more.

Reversal of the convictions will leave the private parties

to the dispute over segregation at the lunch counters to

work out a resolution of their differences by lawful means

of persuasion and pressure, while affirmance would result

in continued reliance upon police and court action to per

petuate discrimination in places open to the public.

8

ARGUMENT

It is a denial of the equal protection of the laws

for a State to arrest and convict for disturbing the

peace Negroes who peaceably seek service by remain

ing seated at a lunch counter located in a commer

cial establishment open to the public.

Petitioners in each of these cases, Negro college stu

dents in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, were arrested when,

seeking to be served food at public lunch counters located

in stores and a bus terminal in that city, they remained

seated at the lunch counters after being refused service

on the sole ground that they were Negroes. Although no

disturbance in fact occurred, petitioners were convicted

and sentenced to jail for “ disturbing the peace,” defined

by La. Rev. Stat. §14:103(7) (1950) as any act committed

“ in such a manner as to unreasonably disturb or alarm

the public” (full text supra p. 3, note 1). For the reasons

stated in the annexed Motion for Leave to File Brief, the

Committee on the Bill of Rights of The Association of the

Bar of the City of New York submits this brief as amicus

curiae in support of the position that arrest and convic

tion of petitioners in these circumstances constituted

State action enforcing discrimination based on race or

color in the opportunity to purchase food at a place open

to the public, and as such deprived petitioners of the

equal protection of the laws in contravention of the Four

teenth Amendment.2

2. Believing that the issue of State enforcement of racial dis

crimination in the circumstances presented in these cases is of na

tionwide public importance (see annexed Motion for Leave to File

Brief), and that it is, moreover, in the context of the records of

these cases the narrowest issue squarely presented, amicus curiae

has limited this brief to discussion of that issue. This limitation is

9

I

It lias been established that equal opportunity to pur

chase food in a place open to the public is a substantial

personal and property right protected by the Fourteenth

Amendment against infringement by State action based

on race or color. Burton v. Wilmington Parking Author

ity, 365 U. S. 715 (1961). Not only the opinion of the

Court but each of the individual opinions in Burton is

premised on this principle. See 365 U. S. at 721-22, 726-

27, 727, 729. Indeed, the proposition “ cannot be doubted,”

as the Court earlier said in relation to equal opportunity

to purchase and occupy residential property. Thus, in

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 10-11 (1948), the Court

said:

“ It cannot be doubted that among the civil rights

intended to be protected from discriminatory state

action by the Fourteenth Amendment are the rights

to acquire, enjoy, own and dispose of property. Equal

ity in the enjoyment of property rights was regarded

by the framers of that Amendment as an essential

pre-condition to the realization of other basic civil

not intended to express any opinion as to other questions or argu

ments presented by the parties in their respective briefs.

There have been numerous convictions since February 1960 in

various State courts on facts generally similar to those of the present

cases. See, e.g., Petition for Certiorari, Garner, p. 28; Pollitt, “Dime

Store Demonstrations: Events and Legal Problems of First Sixty

Days,” 1960 Duke L. J. 315. A number of petitions for certiorari

have already been filed or may be expected to be filed this Term.

Disposition of the present cases in favor of petitioners on the issue

dealt with in this brief will govern at least Avent v. North Carolina,

No. 85, and Fox v. North Carolina, No. 86, pending on petitions for

writs of certiorari. Examination of the records in those cases re

veals no significant distinction from the cases presently before the

Court. In the North Carolina cases the arrests and convictions

were under a criminal trespass provision, N. C. Gen. Stats. §14-134

(1953), rather than for disturbing the peace, but the position taken

in this brief would apply to use of any criminal law sanction in

similar circumstances.

10

rights and liberties which the Amendment was in

tended to guarantee.”8

For as long as “ State action” has been the touchstone

of applicability of the Fourteenth Amendment, it has been

accepted that discriminations originating with private con

duct in which the State participates, or which are author

ized or enforced by acts of the State, become subject

thereby to the prohibition of the Amendment. See Civil

Rights Cases, 109 IT. S. 3, 11, 17, 24 (1883); Shelley v.

Kraemer, supra; Barrows v. Jackson, 346 IT. S. 249 (1953);

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, supra; cf. Marsh

v. Alabama, 326 IT. S. 501, 509 (1946); NAACP v. Alabama,

357 IT. S. 449, 463 (1958).

Eecognizing that courts have frequently been the organs

of the State called upon to enforce discriminations originat

ing in private conduct, this Court has held that State courts

may not do so, either by civil or criminal sanctions. Thus,

in Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, judicial enforcement by 3

3. The intention of the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment

that Negroes have equal opportunities to exercise basic economic

rights, free of discriminatory restrictions or prohibitions imposed or

enforced by State action, was spelled out in Section 1 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27, the drafting and enactment of which

occurred contemporaneously with the drafting and approval of the

Fourteenth Amendment by the 39th Congress. The statute, whose

text and history were set out in Shelley in support of the passage

quoted supra, provides (as now codified in 42 U. S. C. §1982) :

“All citizens of the United States shall have the same right,

in every State and Territory, as is enjoyed by white citizens

thereof to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real

and personal property.”

The Court has held that the Amendment and this statute protect the

same rights. Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24, 30-33 (1948) ; Shelley

v. Kraemer, supra; Buchanan v. Worley, 245 U. S. 60, 75-79 (1917).

Moreover, it is apparent that the word “right” was used in the

statute in a broad sense to proscribe all State action denying equality

of legal privileges on account of race. Cf. Takahashi v. Fish and

Game Comm’n, 334 U. S. 410, 419-20 (1948).

11

injunction of a restrictive covenant against occupancy of

residential property by non-whites was held to violate the

Fourteenth Amendment. Thereafter, Barrows v. Jackson,

346 U. S. 249 (1953), held that such a covenant could not

be given indirect judicial enforcement by an action for

damages against a white owner who sold property in breach

of the restrictive covenant. In Gayle v. Browder, 352 IT. S.

903 (1956), the Court nullified State and local criminal

sanctions for the enforcement of segregation on privately-

owned local buses.4 A similar principle was applied earlier

in Marsh v. Alabama, 326 IT. S. 501 (1946), which invali

dated application of a general criminal trespass law to

persons exercising a constitutional right (there, distribu

tion of religious literature) on the property of a privately-

owned “ company town” in opposition to the edict of the

landowner.

The doctrine of these cases is most familiarly identified

with Shelley v. Kraemer. The Court there stated that the

protection of the Fourteenth Amendment is invoked when

private discriminatory acts are carried out by “ the active

intervention of the state courts, supported by the full

panoply of state power,” and when the State has “ made

available to [private] individuals the full coercive power

of government” to enforce such discrimination (334 U. S.

at 19). In the present cases, the arrests of petitioners by

local police officers, as well as their subsequent convictions

for “ disturbing the peace”—-all avowedly based solely on

4. The per curiam opinion of this Court, affirming Browder v.

Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala. 1956), merely cited Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) ; Baltimore v. Dawson,

350 U. S. 877 (1955); and Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 (1955),

each of which had dealt with racial discrimination in facilities owned

and operated by governmental entities. The local buses in Gayle

were owned and operated by a business corporation. Thus the

Gayle decision is direct authority that a State may not utilize its

criminal-law sanctions to enforce discrimination in privately-owned

facilities used by the public, as it could not with respect to govern

mental facilities used by the public. See also infra pp. 15-16.

12

their peaceful attempts to he served at public lunch counters

(Garner E. 35-36, Briscoe E. 35-38, Boston E. 37; see supra

pp. 4, 5, 6)—-brought to bear in support of the discrimi

natory refusals to serve them “ the full coercive power of

government. ’ ’

The participation of the State is emphasized in these

cases by the fact that, although in two of them the police

were called by the manager or an employee, it appears that

in each case the arrests were made on the initiative of the

police, without direct request by the person in charge of

the lunch counter (Garner E. 31, 34-37, Briscoe E. 33, 34-38,

Boston E. 30, 36). In any event, the individual in charge

had no right to seek the support of the police to enforce

racial discrimination in these public places. As the Court

said in Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, 334 U. S. at 22:

‘‘ The Constitution confers upon no individual the right

to demand action by the State which results in the

denial of equal protection of the laws to other indi

viduals.”

Petitioners peaceably sought service by remaining seat

ed at these lunch counters, located in stores open to the

public and where white persons would be served who sat

down in the same fashion (Garner E. 32, Briscoe E. 31-32,

Boston E. 30). Their arrests and convictions under these

circumstances provided support for the private owners’

segregation rules through State action of the most direct

sort, combining the coercive force of the police with the

ultimate sanction of the judicial arm of the State.5

5. It is, of course, immaterial to the issue of Fourteenth Amend

ment violation whether the police or the courts act under a statute

expressing the aim of enforcing discrimination in privately-owned fa

cilities (Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917) ; Gayle v. Brow

der, 352 U. S. 903 (1956)), or act to enforce such discrimination

under a statute of general applicability (Boman v. Birmingham

Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531 (5th Cir. 1960); cf. Marsh v. Alabama,

13

i l

Application of the principles outlined above to these

cases is not precluded by the fact that the discriminatory

conduct being enforced by the State is that of the proprie

tors of privately-owned commercial establishments. The

Court has recognized that the extent to which a property

owner is affected by rights in others depends upon the ex

tent to which he himself, “ for his advantage, opens up

his property for use by the public in general.” Marsh v.

Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, 506 (1946). There the Court

stated:

“ Ownership does not always mean absolute dominion.

The more an owner, for his advantage, opens up his

property for use by the public in general, the more

do his rights become circumscribed by the statutory

and constitutional rights of those who use it.”6

Marsh decided that sidewalks in the business block of

a “ company town” were as open for free-speech purposes

as those of municipalities. Subsequently, lower courts have

made analogous rulings rejecting trespass charges in

criminal and civil cases involving picketing on the side

walks of privately-owned shopping centers. E.g., State v.

326 U. S. 501 (1946)), or, indeed, act to enforce such discrimination

without relying on statutory authority {Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U. S. 1, 14-18 (1948); Baldzvin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750, 756-60

(5th Cir. 1961)). For “State action of every kind * * * which

denies * * * the equal protection of the laws” is proscribed by the

Amendment. Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 11 (1883) (Emphasis

added).

6. The Court reiterated this theme in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U. S. 1, 22 (1948) :

“And it would appear beyond question that the power of the

State to create and enforce property interests must be exercised

within the boundaries defined by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Cf. Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 (1946).”

14

Williams, 44 Lab. Eel. Eef. Man. 2357, 2360-62 (Baltimore

Grim. Ct. 1959); Freeman v. Retail Clerks Union, 45 Lab.

Eel. Eef. Man. 2334, 2342 (Wash. Super. Ct. 1959). In one

such case, a court in Baleigh, North Carolina, relying on

Marsh, dismissed trespass charges against Negroes who

were protesting segregated lunch counters in the stores of

a shopping center by demonstrating on its privately-owned

sidewalks. See New York Times, April 23, 1960, p. 21, col.

1; Pollitt, supra note 2, at 350 n.206. Similarly, picketing

within New York’s Pennsylvania Station, directed against

a news stand located in a public concourse there, has been

held, partly on the authority of Marsh, to be immune from

prosecution as disorderly conduct (under a definition simi

lar to that of disturbing the peace in the statute involved

here). People v. Barisi, 193 Misc. 934, 86 N. Y. S. 2d 277

(Magis. Ct. 1948).

Each of the cases described dealt with a privately-

owned sidewalk or concourse maintained by the owner for

access by the public to places of business. Here it is such

places of business, open to traffic and trade by the public,

that are in question. The stores and bus terminal involved

here, like the locations dealt with in Marsh and the cases

following it, have been opened up by the proprietors for

use by the public (Garner E. 32, Briscoe E. 32-34, Hoston

B, 31-32, 37; see supra pp. 3, 4, 6). State enforcement

of racial discrimination therein by criminal sanctions is

therefore offensive to the prohibition of the Fourteenth

Amendment.7

7. No special challenge to the traditional right or power of a

merchant to select his customers individually is presented by these

cases. Enforcement of that principle has never been absolute. Like

any economic power or property right, it is bounded by limitations

drawn from superior legal sources, including the Constitution. See

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 22 (1948), supra note 6; cf., e.g.,

United States v. Parke, Davis & Co., 362 U. S. 29 (1960) ; Cali

fornia Inter-Insurance Bureau v. Maloney, 341 U. S. 105 (1951).

15

In similar factual circumstances involving segregation

on privately-owned local buses, governmental enforcement

of segregated-seating rules originating with the private

owner has been held to violate the Fourteenth Amendment.

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 (1956), see supra note 4;

Flemming v. South Car. Elec. £ Gas Co., 239 F. 2d 277

(4th Cir. 1956); Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F.

2d 531 (5th Cir. 1960).

In a decision affirmed by this Court, a three-judge Dis

trict Court said, citing Shelley v. Kraemer, that enforce

ment of the bus company’s rules by the police and courts

raises the difference, “ a constitutional difference, between

voluntary adherence to custom and the perpetuation and

enforcement of that custom by law.” Browder v. Gayle,

142 F. Supp. 707, 715 (M. D. Ala. 1956), affirmed, Gayle v.

Browder, supra. A ruling to the same effect was made

by the Fifth Circuit in the Boman case, supra, which quoted

the District Judge’s comment that “ the police officers were

without legal right to direct where they [Negroes who re

fused to move to the rear of a bus, or to leave it when the

driver took it to the barn upon their refusal] should sit

because of their color. The seating arrangement was a

matter between the Negroes and the Transit Company.”8

8._ 280 F. 2d at 533 n.l. The entire discussion of this point by

District Judge Grooms is illuminating in relation to the facts of the

present cases. As quoted by the Court of Appeals, ibid., it reads:

“A charge of ‘a breach of the peace’ is one of broad import

and may cover many kinds of misconduct. However, the Court

is of the opinion that the mere refusal to obey a request to move

from the front to the rear of a bus, unaccompanied by other

acts constituting a breach of the peace, is not a breach of the

peace. In as far as the defendants, other than the Transit Com

pany, are concerned, plaintiffs were in the exercise of rights

secured to them by law.

“Under the undisputed evidence, plaintiffs acted in a peace

ful manner at all times and were in peaceful possession of the

seats which they had taken on boarding the bus. Such being

16

Each of the has cases just discussed held that police

and court enforcement of the private owner’s rule of seg

regated seating in local buses is unconstitutional, without

reference to the affirmative statutory requirement of non

discrimination that exists with respect to facilities of in

terstate travel. Of., e.g., Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454

(1960). Similarly, the Fifth Circuit has recently held to

be unconstitutional discriminatory police action regard

ing use of the “ white” waiting room in a railroad station

by Negroes other than interstate travelers. In Baldwin

v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961), injunctive relief

was granted against a local police practice of checking

Negroes found in the “ white” waiting room to see if

they held interstate tickets. The Court of Appeals ruled

that, since Gayle v. Browder, supra, “ it is too late now

to question the absolute right of Negroes engaged in in

trastate commerce to be free from discrimination by po

lice officers on the basis of race” (287 F. 2d at 758-59)

(Emphasis added).* 9

the case, the police officers were without legal right to direct

where they should sit because of their color. The seating ar

rangement was a matter between the Negroes and the Transit

Company. It is evident that the arrests at the barn were based

on the refusal of the plaintiffs to comply with the request to

move since those who did move, though equally involved except

as to compliance, were not arrested.

“Under the facts in this case, the officers violated the civil

rights of the plaintiffs in arresting and imprisoning them. Ordi

nance 1487-F, and their ‘willful’ refusal to move when directed

to do so, did not authorize or justify their conduct.”

The full opinion of the District Judge is reported sub nom. Boman

v. Morgan, 4 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1027 (N. D. Ala. 1959).

9. This part of the Fifth Circuit’s decision was based upon evi

dence that such discriminatory police action had in fact occurred,

independent of a State Public Service Commission rule requiring

segregated waiting rooms, which was invalidated elsewhere in the

opinon (compare 287 F. 2d at 756-60 with id. at 753-56).

17

It is clear in the records of all of the present cases

that petitioners were arrested solely because they were

Negroes seeking to he served at these public lunch counters.

(Garner R. 35-36, Briscoe R. 35-38, Boston R. 37; see

supra pp. 4, 5, 6). The trial court’s oral findings of

guilt were explicitly placed on that basis (Garner R. 37,

Briscoe R. 38-39, Boston R. 39), and were sustained by

the Supreme Court of Louisiana in memorandum orders

(see supra p. 6). Thus, the highest court of the State

has, in effect, construed a criminal statute of general ap

plicability “ as authorizing discriminatory classification

based exclusively on color” by the proprietors of these

stores. Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365

U. S. 715, 727 (1961) (opinion of Stewart, J . ) ; id. at 729

(opinion of Harlan, J., joined by Whittaker, J . ) ; cf. id. at

727 (opinion of Frankfurter, J.).

The proprietors’ discriminatory rules were given

forceful effect by the totality of police and judicial actions

in these cases. Though the element of governmental prop

erty which the majority of the Court found controlling in

Burton is not involved here, the significant effect of the

State enforcement actions in these cases “ indicates that

degree of state participation and involvement in discrim

inatory action which it wus the design of the Fourteenth

Amendment to condemn.” Id. at 724 (opinion of the

Court).

I l l

The traditional considerations for limiting constitu

tional adjudication to the facts of actual cases before the

Court are compelling in the sensitive area of race rela

tions, and particularly so where the claim to freedom

from State-enforced racial discrimination is opposed by a

claim to freedom in the management of private property.

The judicial precedents discussed in this brief indicate that

18

the resolution of such conflicting claims may vary with the

circumstances. Thus the decision of the Court in the pres

ent cases need not he taken as having decided issues not

presented in those cases on their own facts. It seems ap

propriate, therefore, to note in summary form some mat

ters not involved in the facts of the present cases:

(1) The issue of affirmative remedies against dis

criminatory acts does not arise in these criminal

cases. The question here is simply whether peaceful

activities by Negroes seeking equal treatment in

normal economic transactions are immune from crim

inal sanctions interposed against them by the police

or courts of a State or local government.

(2) Decision here need not establish the extent to

which privately-owned property may be used for pur

poses not intended by the owner, for in the cases now

before the Court petitioners merely attempted to use

the lunch counter facilities of these stores in the man

ner in which they were intended to be used—by sit

ting down at the counter and ordering food or bev

erages.10

(3) Nor do these cases present for decision any

issue as to discriminatory exclusion from places af

fected with a countervailing right of privacy on the

part of the property owner, such as a private home.

Cf. Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U. S. 622, 641-45 (1951).

10. That petitioners’ motives may have included a desire to

protest or demonstrate against the discriminatory practices in ques

tion is immaterial, for their convictions had to be, and were, based

on their overt actions, and the form petitioners’ protest or demon

stration took was merely seeking service in the normal manner.

The convictions cannot be sustained upon petitioners’ refusals to

leave the premises upon orders of the police. Such refusals cannot

be deemed criminal in circumstances in which the police had no

right, under the Constitution, to demand that petitioners leave the

premises. Cf., e.g., Boynton v, Virginia, 364 U. ,S. 454 (1960) ;

id. at 464-65 (dissenting opinion) ; Boman v. Birmingham Transit

Co., 280 F. 2d 531 (5th Cir. 1960), supra p. 15 and note 8.

19

Only commercial facilities open to traffic and trade by

the public are involved in the present cases.

(4) The use of force by a store proprietor as an

alternative to police action in seeking to remove Ne

groes seeking service is not involved. There is nothing

in the records of these cases to indicate that forceful

removal was even contemplated.11

(5) Nor is there any showing here that petitioners’

conduct did, or in the absence of action by the poliee

would, provoke violence or disorder by persons other

than the proprietor.12 In any event, that others may

respond with disorder to peaceable activities in pur

suit of equal treatment should not permit State or

local authorities to stave off possible disorder by sanc

tions against the persons peacefully seeking such treat

ment. Cf. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 16 (1958).

All that these cases involve is the question whether

Negroes shall be free of “ the full coercive power of gov

11. Therefore, it is not necessary here to consider whether con

stitutional complusions may affect causes of action and defenses in

cases involving such forceful removal. As to that, see Schwelb,

“The Sit-In Demonstration: Criminal Trespass or Constitutional

Right?” 36 N. Y. U. L. Rev. 779, 800-08 (1961).

12. The incidents of violence against the “Freedom Riders”

earlier this year cannot reasonably be deemed a pragmatic argument

against recognition here of the right to be free of State-enforced

segregation in the new context of lunch counters. Those isolated

incidents of violence did not occur in response to any ruling marking

a new advance against discrimination, but on the occasion of a highly-

publicized exercise of a right long established. See, e.g., Morgan v

Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 (1946).

There is evidence that in many Southern communities peaceful

resolution of the struggle sparked by the “sit-ins,” with elimination

or reduction of discrimination at the lunch counters, has occurred.

See, e.g., New York Times, June 6, 1960, p. 1, col. 2; June 24, 1960,

p. 1, col. 6; July 25, 1960, p. 1, col. 8; August 11, 1960, p. 14, col.

5; October 18, 1960, p. 47, col. 5; January 22, 1961, p. 72, col. 8;

May 7, 1961, §4, p. 10, col. 1.

20

ernment” (Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 19 (1948))

against their efforts to seek equality of service in the pur

chase of food in commercial establishments. The effect of

a decision reversing these convictions will be to leave the

private parties to the dispute over segregation at these

lunch counters—the merchants and Negro residents of the

community—to work out a resolution by lawful means of

persuasion and pressure. This is the necessary result of

the Fourteenth Amendment’s bar to State enforcement of

discrimination, as in other instances where the Court has

ruled that judicial sanctions may not be interposed in

economic or social struggles between contending forces of

private interests. Cf. Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88

(1940); San Diego Bldg. Trades Council v. Garmon, 359

TJ. S. 236 (1959).'

On the other hand, affirmance of the decision below

would offer little inducement to the merchants to work

toward a peaceful resolution of the dispute raised by the

claim of Negro residents of the community for equal treat

ment. Instead, police and court action would continue to

be relied upon to perpetuate discriminatory practices in

places open to the public. Such action the Fourteenth

Amendment forbids the States to take.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgments below

should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

W illiam A. Delano

J ohn R. F ernbach

Murray A. Gordon

Martin F . R iohman

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

307 BAR PRESS INC., 84 LAFAYETTE ST., NEW YORK 13 — W A S - 3432

( 8939)