North Carolina v. Alford Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. North Carolina v. Alford Brief Amici Curiae, 1969. c5d714ba-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b2e23753-0bd8-41b5-887d-61c25f66b279/north-carolina-v-alford-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

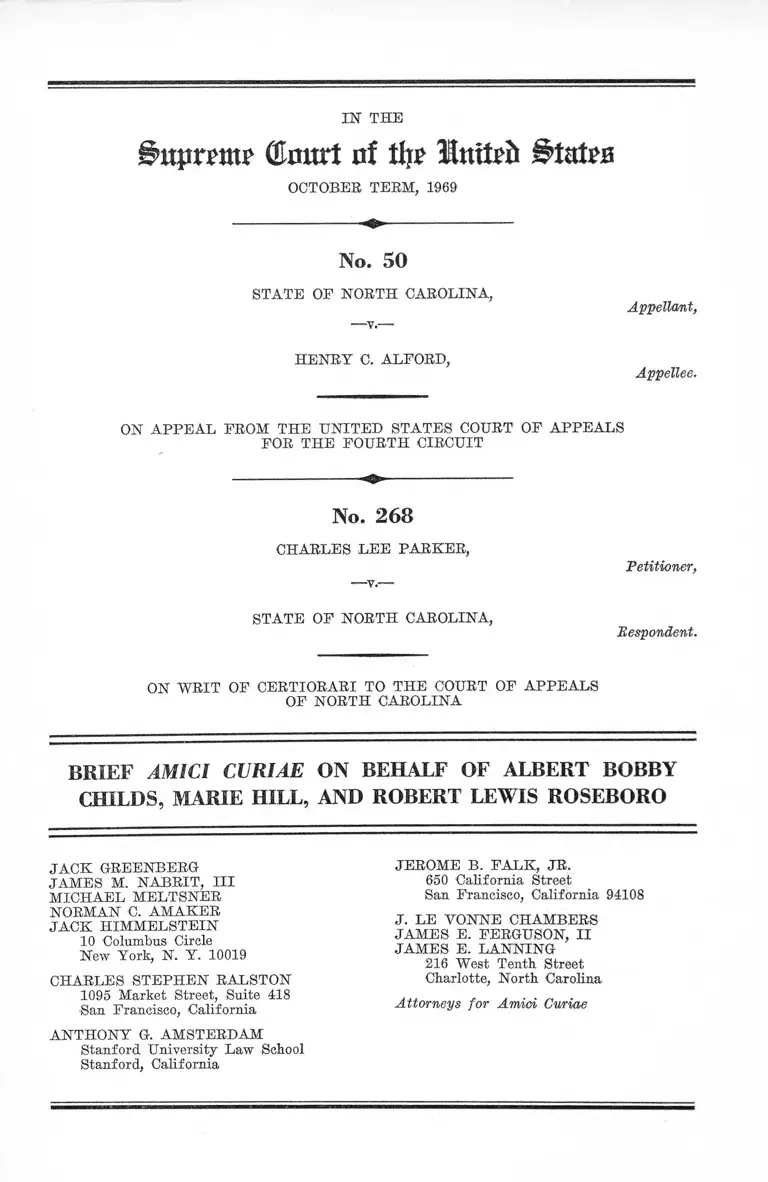

IN THE

(tort at tl)? Mmteb States

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

No. 50

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA,

Appellant,

---y.---

HENRY C. ALFORD,

Appellee.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 268

CHARLES LEE PARKER,

— v.—

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE COURT OF APPEALS

OF NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE ON BEHALF OF ALBERT BOBBY

CHILDS, MARIE HILL, AND ROBERT LEWIS ROSEBORO

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

MICHAEL MELTSNER

NORMAN C. AMAKER

JACK HIMMELSTEIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

1095 Market Street, Suite 418

■San Francisco, California

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California

JEROME B. FALK, JR.

650 California Street

San Francisco, California 94108

J. LE YONNE CHAMBERS

JAMES E. FERGUSON, II

JAMES E. LANNING

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

Attorneys for Amici Gu/riae

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of Interest o f the Amici ............................. 2

Statement ............................................................................. 4

Summary of Argument .................................................... 6

A rgum ent

I. A Statutory Scheme Which Subjects to the Risk

of the Death Penalty Only Those Defendants Who

Elect to Stand Trial on the Issue of Guilt, and

Which Forbids the Imposition of Death Upon

Those Defendants Who Waive Their Constitu

tional Rights to Deny and Contest Guilt, Is Uncon

stitutional ..................................................................... 8

II. A Guilty Plea, the Making of Which Was Substan

tially Motivated by the Threat of Imposition of

the Death Penalty, Is Involuntary and Cannot

Stand ........................................................................... 22

Introduction .......................................................... 22

A. The Threat of the Death Penalty May De

prive a Guilty Plea of Its Voluntary Char

acter ................................................................. 23

B. Standards for Determining the Validity

of a Potentially Death Penalty-Induced

Guilty Plea ...................................................... 26

11

T able of Cases

page

Bloom v. Illinois, 391 U. S. 194 (1968) .......................... 17

Boykin v. Alabama,------ U. S . ------- , 23 L. Ed. 2d 274

(1969) .............................................................7,16,23,24,27

Brookhart v. Janis, 384 U. S. 1 (1966) ........................ 23

Bullock v. Harpole, 102 So. 2d 687 (1958) ............... 15

Carpenter y. Wainwright, 372 F. 2d 940 (5tb Cir.

1967) .............................................................. ................ 24,26

Childs v. North Carolina, 0. T. 1969, No. 25 Misc..... ..2, 4, 8

Conley v. Cox, 138 F. 2d 786 (8th Cir. 1943) ............... 25

De Stefano v. Woods, 392 U. S. 631 (1968) ................... 17

Davis v. North Carolina, 384 U. S. 737 (1966) ............... 29

Dillon v. United States, 307 F. 2d 445 (9th Cir. 1962) 25

Doran v. Wilson, 369 F. 2d 505 (9th Cir. 1966) ..... 24

Douglas v. Alabama, 380 IT. S. 415 (1965) .................. 23

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U. S. 145 (1968) ..................... 17

Ellis v. Boles, 251 F. Supp. 1021 (N. D. W. Va. 1966) 25

Euziere v. United States, 249 F. 2d 293 (10th Cir. 1957) 25

Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391 (1963) .................................. 19

Forcella and Funicello v. New Jersey, O. T. 1969, No.

18 Misc.........................................................................4, .10, 30

G-arrity v. New Jersey, 385 U. S. 493 (1967) ................ 24

Halliday v. United States, 394 U. S. 831 (1969) (per

curiam) .... ..................... ...... ............................................ 27

Hamilton v. Alabama, 368 U. S. 52 (1961) ....... ............. 19

I l l

Johnson v. New Jersey, 384 U. S. 719 (1966) ............... 29

Johnson v. Wilson, 371 F. 2d 911 (9th Cir. 1965) ....... 25

Kercheval v. United States, 274 U. S. 220 (1927) ....... 23

Lynch v. Overholser, 369 U. S. 705 (1962) ................... 13

McCarthy v. United States, 394 U. S. 459 (1969) ....... 16

Machibroda v. United States, 368 U. S. 487 (1962) .... 25

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U. S. 436 (1966) ......... ...... ...... 28

Murphy v. Wainwright, 372 F. 2d 942 (5th Cir. 1967) 24

North Carolina v. Pearce,------U. S. —-—, 23 L, Ed. 2d

65 (1969) ....................................................................4,19,20

O’Connor v. Ohio, 385 U. S. 92 (1966) ........................... 23

Pope v. United States, 392 U. S. 651 (1968) ........ ...4, 5,18

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45 (1932) ....................... 19

Singer v. United States, 380 U. S. 24 (1965) ............... 13

Smith y . United States, 321 F. 2d 954 (9th Cir. 1963) 25

Smith v. Wainwright, 373 F. 2d 506 (5th Cir. 1967) ..24, 26

State v. Atkinson, ------ N. C. ------ , 167 S. E. 2d 241

(1969) .........................................................................3,4,6,22

State v. Childs, 269 N. C. 307, 152 S. E. 2d 453 (1967) 2

State v. Forcella, 52 N. J. 263, 245 A. 2d 181 (1968) ....10,11,

13,14

State v. Harper, 162 S. E. 2d 712 (1968) ................. 14

State v. Hill, No. 2, Fall Term, 1969 ............................ 2

State v. Peele, 274 N. C. 106, 161 S. E. 2d 568

(1968) ................................................................... 5,10,11

PAGE

IV

PAGE

State v. Roseboro, N o .------ , Fall Term, 1969 ............... 2

State v. Spenee, 274 N. C. 536, 164 S. E. 2d 593 (1968) 5

Stein v. New York, 346 TJ. S. 156 (1952) ....................... 19

Teller v. United States, 263 F. 2d 871 (6th Cir. 1959) 25

United States v. Cox, 342 F. 2d 167 (5th Cir. 1965) .... 13

United States v. Glass, 317 F. 2d 200 (4th Cir. 1963) .. 25

United States v. Jackson, 390 U. S. 570 (1968) ....2, 3, 5, 6,

10,13,14,18,

19, 20, 26, 29

United States v. Tateo, 214 F. Supp. 560 (S. D. N. Y.

1963) ..................................................................... 25

United States ex rel. Elksnis v. Gilligan, 256 F. Supp.

244 (S. D. N. Y. 1966) .................................................... 25

United States ex rel. Ross v. McMann, 409 F. 2d 1016

(2nd Cir. 1969) (en banc) ........................................ 24,26

United States ex rel. Collins v. Maroney, 382 F. 2d 547

(3rd Cir. 1967) .......................... 24

United States ex rel. Cuevas v. Bundle, 258 F. Supp.

647 (E. D. Pa. 1966) .................................................. 25,26

"Walker v. Johnston, 312 U. S. 275 (1941) ..................... 25

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375 (1955) ................... 19

Workman v. United States, 337 F. 2d 226 (1st Cir.

1964) ................................................................................. 25

S tate S tatutes

La. Code of Crim. Proe. Art. 557 .................................. 15

Miss. Code §2217 ............................................................... 15

Miss. Code §2536 ............................................................... 15

Y

Neb. Eev. Stat. §28-417...................................................... 15

N. C. Gen. Stat. §15-162.1 ................................................8,15

N. C. Session Laws, 1969, Ch. 117 ................................ 22

N. H. Eev. Stat. Ann. §585:4 .......................................... 15

N. H. Eev. Stat. Ann. §585:5 ............................................ 15

N. J. S. A. §2A :113-3 ........................................................ 15

N. J. S. A. §2A:113-4..................................................... . 15

N. Y. Code of Crim. Proc. §3321 .................................... 15

Eev. Code of Wash., Title 9, §9.52.010............................ 15

S. C. Code §17-553.4 (1967) (Cum. Supp.) ................... 15

Vernon’s Ann. Code of Crim. Proc. of Texas, Art. 1.14,

as amended, Tex. Act 1967, p. 1733, ch. 659, §1, effec

tive August 28, 1967 ...................................................... 15

Wyo. Stat. §7-195 ................................................................ 15

O th er A uth ority

PAGE

Note, 54 Cornell L. Eev. 448 (1969) 19

I n t h e

(Errurt of tlj? Inttefc

O ctober T erm , 1969

No. 50

S tate of N orth Carolina,

— v.—

Appellant,

H en ry C. A lford,

Appellee.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 268

Charles L ee P arker,

— v .—

Petitioner,

S tate of N orth Carolina,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE COURT OF APPEALS

OF NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE ON BEHALF OF

ALBERT BOBBY CHILDS, MARIE HILL,

AND ROBERT LEWIS ROSEBORO

2

Statement of Interest of the Amici

Amici Albert Bobby Childs,1 Marie Hill,2 and Robert

Lewis Roseboro3 are North Carolina prisoners under sen

tences of death. When charged with a capital crime, each

was given by North Carolina statutory practice the choice

of pleading guilty, thereby assuring a sentence of life im

prisonment, or of risking the death penalty after jury trial

npon a plea of not guilty. Each pleaded not guilty and,

upon conviction, was sentenced to die.

1 Albert Bobby Childs is a 46 year old Negro man. Charged

with the crimes of rape and burglary, he pleaded not guilty, was

convicted and sentenced to death by a jury in the Superior Court

of Buncombe County in November, 1965. His conviction and sen

tences of death were affirmed on appeal, State v. Childs, 269 N. C.

307, 152 S. E. 2d 453 (1967). In June, 1967, he filed a petition

for a post-conviction hearing in the Superior Court. He raised an

issue under United States v. Jackson, infra, which the Superior

Court resolved by ruling that Jackson was inapplicable and that

his death sentence was constitutional. The Court of Appeals of

North Carolina refused to review the Superior Court on certiorari

and Childs thereafter filed a petition for certiorari in this Court

which is now pending. Childs v. North Carolina, 0. T. 1969, No.

25 Misc.

2 Marie Hill is a 17 year old Negro girl. Charged with the crime

of murder, she pleaded not guilty, was convicted and sentenced

to death by a jury in the Superior Court of Edgecombe County

in December, 1968. She now has an appeal pending in the Supreme

Court of North Carolina wherein she urges that her death sentence

is void as a penalty on the exercise of her constitutional rights.

State v. Hill, No. 2, Pall Term, 1969.

3 Robert Lewis Roseboro is a 16 year old Negro boy. Charged

with the crime of murder, he pleaded not guilty, was convicted

and sentenced to death by a jury in the Superior Court of Cleve

land County in May, 1969. In his pending appeal in the Supreme

Court of North Carolina, he urges the unconstitutionality of his

sentence of death on grounds identical to those asserted by Marie

Hill. State v. Roseboro, No. ______ Pall Term, 1969.

3

Each is now challenging the death sentence imposed upon

him as a penalty attached to the exercise of his constitu

tional rights to plead not guilty and to be tried by a jury,

invoking United States v. Jackson, 390 U. S. 570 (1968).

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Cir

cuit has vindicated this constitutional contention in Alford

v. North Carolina, No. 50, by holding that the capital pun

ishment provisions of North Carolina law are indeed un

constitutional by force of Jackson. The State bases its

appeal to this Court upon the proposition—not necessary

to decision of the case below or here, but nevertheless

strongly urged in North Carolina’s jurisdictional state

ment and brief—that the Fourth Circuit erred in this con

stitutional decision, which would have the effect that amici s

death sentences could not be carried out.4 Amici, therefore,

4 Amici’s position is that the death sentences imposed upon them,

under a procedure that taxed their constitutional rights to defend

with the penalty of death, are unconstitutional. In that regard,

they urge that the Supreme Court of North Carolina was plainly

wrong when it held in State v. Atkinson, ------ N. C. - , 167

S. B. 2d 241 (1969) that the effect of a declaration of the uncon

stitutionality of the North Carolina capital statutory scheme under

Jackson would be to eliminate the provision whereby capital de

fendants could save their lives by pleading guilty, rather than to

invalidate death sentences imposed upon defendants who entered

not guilty pleas. This is so because, by whatever state-law “sepa

rability” doctrines North Carolina seeks to correct the constitu

tional vice of its statutory scheme for the future, no notion of

“ separability” can change the unconstitutional choices offered by

that scheme in the past. Guilty pleas at the time amici were re

quired to plead were lawful and were regularly being accepted by

the courts of North Carolina. There was then no legal impedi

ment to amici’s proffering guilty pleas which, upon acceptance by

the court, would have assured them immunity from the death

penalty. Nothing which the State of North Carolina may announce

ex post facto can effect in any way this statutory pattern that

confronted amici when on trial for their lives. No ruling now can

unwrite the statutes that then confronted them, disestablish the

options unconstitutionally presented for their choice, unmake the

4

have a life-or-death interest in the appeal, since any deci

sion that would reverse the Fourth Circuit by holding

Jackson inapplicable in North Carolina would thereby de

stroy the promise of life which Alford has held out to them.

Statement

These two cases present a common question for decision:

in what circumstances a guilty plea to a capital charge

must be set aside on the ground that it is “ involuntary,”

improperly coerced by the threat of the death penalty if

the defendant elects to plead not guilty and is convicted.

In North Carolina v. Alford, No. 50, the Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit found as a fact that the defendant’s

choice they made, or diminish the significance of that choice. All

that any court can do at this point in time is to relieve persons

condemned under this scheme from the unconstitutional conse

quence of the unconstitutional procedure under which they were

sentenced to death—that is, the death sentence. See the petition

for writ of certiorari in Forcella and Funicello v. New Jersey,

0. T. 1969, No. 18 Misc., pp. 35-37.

We add that it seems plain to us, contra the reasoning in State

v. Atkinson, supra, that amici have standing to claim the benefits

of Jackson. A plainer instance of standing, indeed, could hardly

be imagined: amici are challenging sentences of death imposed

upon them under an unconstitutional statute as penalties for the

exercise of constitutional rights. That they resisted the pressure

of threatened death and exercised their constitutional rights at

the jeopardy of their lives is hardly a ground for denying them

standing to complain when their lives are taken in consequence.

See State v. Atkinson, supra, 167 S. B. 2d, at 259-260. If this

proposition was at all debatable prior to this Court’s decision in

North Carolina v. Pearce, ------ U. S. -----, 23 L. Ed. 2d 656

(1969), it is no longer. See Pope v. United States, 392 U. S. 651

(1968) (per curiam) ; Petition for Writ of Certiorari in Childs

v. North Carolina, 0. T. 1969, No. 25 Misc., pp. 23-25; Petition

for Writ of Certiorari in Forcella and Funicello v. New Jersey,

supra, pp. 29-35.

5

plea was involuntary, the undisputed evidence showing that

“he pleaded guilty . . . to avoid possible imposition of the

death penalty,” 405 F. 2d 340, 348 (4th Cir. 1968). In

Parker v. North Carolina, No. 268, the Court of Appeals

of North Carolina affirmed the denial of a petition for post-

conviction relief which contended that the defendant had

been coerced into pleading guilty by the threat of the death

penalty.

The defendants5 in each of these cases rely heavily on

United States v. Jackson, 390 U. S. 570 (1968), and Pope

v. United States, 392 U. S. 651 (1968) (per curiam), in

which this Court invalidated the death penalty provisions

of the Federal Kidnaping Act and the Federal Bank Bob

bery Act respectively. Those statutes were invalidated be

cause, by allowing a defendant who pleaded guilty (or

waived jury trial) to escape the risk of the death penalty,

they “needlessly encourage [d ]” (390 U. S., at 583) waiver

of the constitutional rights to plead not guilty and have a

jury trial. The Court of Appeals in Alford began its con

stitutional analysis with a determination that North Caro

lina’s death penalty statutes—which like the federal stat

utes in Jackson allowed avoidance of any risk of the death

penalty by a plea of guilty—were unconstitutional. North

Carolina has vigorously challenged that conclusion in this

Court. Its position that Jackson does not invalidate the

North Carolina capital sentencing scheme has been sus

tained not only by the State’s Court of Appeals in Parker,

but also by the North Carolina Supreme Court in State v.

Peele, 274 N. C. 106, 161 S. E. 2d 568 (1968); State v.

5 We use the term “ defendant” throughout to refer to the defen

dant in the original criminal proceeding—the appellee in Alford

and the petitioner in Parker.

6

Spence, 274 N. C. 536, 164 S. E. 2d 593 (1968); State v.

Atkinson,------ N. C. --------, 167 S. E. 2d 241 (1969).

It bears noting that the constitutionality of the North

Carolina death penalty statutes is not necessarily involved

here; the ultimate question presented is simply whether

the guilty pleas of Alford and Parker were “ voluntary.”

A plea may obviously be involuntary even though the statu

tory setting in which it was entered is constitutional; con

versely, it is perfectly possible that a defendant might, for

reasons having nothing to do with a desire to avoid the

death penalty, enter a voluntary plea in a jurisdiction in

which the death penalty statutes suffer from a Jackson-

like infirmity. However, the fact is that the North Caro

lina statutes are unconstitutional under Jackson, and that

circumstance plays a critical part in our analysis of these

cases. For that reason—and because amici’s lives may

literally depend upon the recognition that the death penalty

statutes of North Carolina are unconstitutional—we dis

cuss the constitutionality of those statutes in Part I. In

Part II, we consider the specific question presented in these

cases—namely, whether the defendant who has pleaded

guilty in a capital case may have that plea set aside if it

can be shown that the plea was motivated by fear that the

death penalty would be imposed if he stood trial.

Summary o f Argument

The death penalty provisions of North Carolina law are

unconstitutional under United States v. Jackson, 390 U. S.

570 (1968), because only a defendant who pleads not guilty

may be sentenced to die. Such a scheme needlessly en

courages guilty pleas and penalizes those choosing to ex-

7

ereise their constitutional rights to deny and contest guilt.

This conclusion is not disturbed because defendants do not

have an absolute right to plead guilty under North Caro

lina practice for neither did defendants under the federal

procedure invalidated in Jackson. No more pertinent is

the fact that in North Carolina—unlike the federal pro

cedure before the Court in Jackson—a defendant cannot

also avoid the death penalty by waiving jury trial on a

plea of not guilty. Jackson condemned undue pressures

upon Fifth as well as Sixth Amendment rights; and a

statutory scheme which informs a defendant that to es

cape all risk of death he must plead guilty, thereby waiv

ing both his right to defend and his incidental right to

jury trial, is more, not less, obnoxious to the Constitution

than the practice that Jackson invalidated.

The Constitution requires that a guilty plea must be

“voluntary” to be valid. Under this principle, certain kinds

of pressures and inducements to plead guilty are deemed

so inherently coercive as to be impermissible as a matter

of law. The threat of execution, suspended if a guilty plea

is interposed, is such an inducement. Where by statute the

state offers those entering a plea of guilty immunity from

the death penalty, pleas entered under the statute are sus

pect and must be set aside unless (1) it affirmatively ap

pears from the record of the original proceedings that the

plea was motivated by permissible considerations (Boykin

v. Alabama,------ U. S .------- , 23 L. Ed. 2d 274 (1969)); or,

alternatively, (2) the plea is determined to have been mo

tivated by considerations other than threat of the death

penalty at a proper evidentiary hearing at which the bur

den of proof is imposed upon the State.

8

A R G U M E N T

I.

A Statutory Scheme Which Subjects to the Risk o f

the Death Penalty Only Those Defendants W ho Elect to

Stand Trial on the Issue o f Guilt, and Which Forbids

the Imposition o f Death Upon Those Defendants Who

Waive Their Constitutional Rights to Deny and Contest

Guilt, Is Unconstitutional.

A complete description of the North Carolina statutory

scheme at issue here is set out in the petition for a writ

of certiorari filed in Childs v. North Carolina, 0. T. 1969,

No. 25 Misc., at pp. 16-17. It will suffice to say that in

North Carolina, a defendant who pleads not guilty to a

capital charge may be sentenced to death in the discretion

of the jury upon conviction. In contrast, the defendant

who waives the right to trial and pleads guilty—with the

approval of the court and prosecution—wholly avoids the

death penalty, and the punishment is automatically fixed

at life imprisonment. N. C. Gen. Stat. §15-162.1.

As in Jackson, defendants may thus avoid the death

penalty in a capital case by waiving the constitutional

right to deny and contest guilt—and with it all of the

constitutionally guaranteed procedural protections sub

sumed within the right to trial. In Jackson, this Court

was confronted with a comparable legislative scheme, un

der which the defendant could avoid the legislatively au

thorized death penalty by waiving either or both of two

constitutional rights: (1) the Fifth Amendment right not

to plead guilty, to deny and contest guilt; and (2) the Sixth

Amendment right to a trial by jury. This scheme was held

unconstitutional:

9

“ The inevitable effect of any such provision is, of

course, to discourage assertion of the Fifth Amend

ment right not to plead guilty and to deter exercise

of the Sixth Amendment right to demand a jury trial.

If the provision had no other purpose or effect than to

chill the assertion of constitutional rights by penalizing

those who choose to exercise them, then it would be

patently unconstitutional. But, as the Government

notes, limiting the death penalty to cases where the

jury recommends its imposition does have another

objective: It avoids the more drastic alternative of

mandatory capital punishment in every ease. In this

sense, the selective death penalty procedure established

by the Federal Kidnaping Act may be viewed as

ameliorating the severity of the more extreme punish

ment that Congress might have wished to provide.

“ The Government suggests that, because the Act

thus operates ‘to mitigate the severity of punishment,’

it is irrelevant that it ‘may have the incidental effect

of inducing defendants not to contest in full measure.’

We cannot agree. Whatever might be said of Con

gress’ objectives, they cannot be pursued by means

that needlessly chill the exercise of basic constitu

tional rights. . . . The question is not whether the

chilling effect is ‘incidental’ rather than intentional;

the question is whether that effect is unnecessary and

therefore excessive. In this case the answer to that

question is clear. . . . Whatever the power of Congress

to impose a death penalty for violation of the Federal

Kidnaping Act, Congress cannot impose such a pen

alty in a manner that needlessly penalizes the asser

tion of a constitutional right. See Griffin v. California,

380 U. S. 609.” {Id. at 581-83.)

10

There may be identified four arguments which have been

advanced in various quarters by those seeking to dis

tinguish and avoid United States v. Jackson as respects

death penalty provisions like North Carolina’s.6 The

fountainhead of these arguments is the opinion of the

New Jersey Supreme Court in State v. Forcella, 52 N. J.

263, 245 A. 2d 181 (1968), whose extremely restrictive

interpretation of Jackson is presently pending for review

here on a petition for certiorari sub nom. Forcella and

Funicello v. New Jersey, 0. T. 1969, No. 18 Mise.

(1) It is argued that the challenged provisions are

“primarily for the benefit of a defendant” (State v. Peele,

274 N. C. 106, 161 S. E. 2d 568, 572 (1968); see also Brief

for Appellant, North Carolina v. Alford, No. 50, at p. 8),

and are designed to operate “ to the benefit of defendants

as a group. The purpose is humane, and so is its overall

impact.” State v. Forcella, 52 N. J. 263, 280, 245 A. 2d 181,

190 (1968).

(2) Defendants in North Carolina do not have an abso

lute right to plead not guilty and thereby avoid the pos

sible imposition of the death penalty. As in New Jersey,

a plea that would escape the death penalty may be ac

cepted only by leave of the prosecution and the court. This,

the New Jersey Supreme Court thought, distinguishes

state practice from the federal where (again, as that court

viewed it) a capital defendant “has a ‘right,’ in a realistic

sense, to plead guilty.” Id. 52 N. J., at 279. See also State

v. Peele, supra, 161 S. E. 2d, at 572 (“ The State, acting

through its solicitor, may refuse to accept the plea, or the

judge may decline to approve it.” ).

6 See note 9, infra.

11

(3) The New Jersey Supreme Court also argued that,

because under the New Jersey-North Carolina procedure,

a waiver only of the right to a jury trial (by pleading not

guilty and submitting to court trial) is not possible, the

Sixth Amendment is not burdened by the death penalty.

Only the Fifth Amendment right not to plead guilty and

to deny and contest guilt is taxed with the risk of a death

sentence. State v. Forcella, supra, 52 N. J., at 271-275.

Although recognizing that this Court’s opinion in Jackson

plainly referred to an infringement of both the Fifth and

Sixth Amendments, the New Jersey Supreme Court con

cluded that “ the two propositions were . . . intertwined,

thus suggesting that not all members of the majority were

ready to say that a statute which did no more than limit

the penalty upon acceptance of a guilty plea must violate

the Fifth Amendment.” Id., 52 N. J. at 272. Jackson is

thus reducible, the court said, to a determination that “ the

federal statute obviously ran afoul of the Sixth Amend

ment.” Id., 52 N. J., at 272.

(4) The North Carolina Supreme Court’s opinion in

State v. Peele, supra, urges that under the Federal Kid

naping Act, “ the law fixes imprisonment in the peniten

tiary, but provides that the jury may impose the death

penalty.” 161 S. E. 2d, at 572. This is supposedly to be

construed with the North Carolina statute which, as the

court viewed it, “provides that the death penalty shall be

ordered unless the jury, at the time it renders its verdict

of guilty . . . fixes the punishment at life imprisonment.”

Id.

We turn to an examination of each of these four argu

ments against the application of Jackson.

12

(1) The Benevolent Intent of the Legislature. It is not

necessary to question the conclusion of the North Carolina

Supreme Court that the statutory scheme which permits

a defendant to avoid the death penalty by pleading guilty

was conceived for the benefit of defendants generally. Nor

do we doubt the statement of the New Jersey Supreme

Court that the similar provisions of that State’s law were

intended as a humane procedural device. But this Court’s

analysis in Jackson began with a recognition that the

same might be said of the procedure imposed by the Fed

eral Kidnaping Act, whose sentencing provisions “ may

be viewed as ameliorating the severity of the more extreme

punishment that Congress might have wished to provide.”

390 U. S. at 582. The Court’s rejection of the legislative

motive as a basis for upholding these procedures was

nonetheless unequivocal:

“Whatever might be said of Congress’ objectives, they

cannot be pursued by means that needlessly chill the

exercise of basic constitutional rights. Cf. United

States v. Robel, 389 U. S. 258; Shelton v. Tucker, 364

U. S. 479, 488-89. The question is not whether the

chilling effect is ‘incidental’ rather than intentional;

the question is whether that effect is unnecessary and

therefore excessive. In this case, the answer to that

question is clear. The Congress can of course mitigate

the severity of capital punishment. The goal of limit

ing the death penalty to cases in which a jury recom

mends it is an entirely legitimate one. But that goal

can be achieved without penalizing these defendants

who plead not guilty and demand jury trial. . . .

Congress cannot impose such a penalty in a manner

13

that needlessly penalizes the assertion of a constitu

tional right. See Griffin v. California, 380 U. S. 609.”

(Id., at 582-83.)

Jackson, then, squarely holds that the humanitarian mo

tives of the legislature do not save a statutory scheme

which operates to penalize “ defendants who plead not guilty

and demand jury trial.” Id.

(2) The Plea of Guilty Can Only Be Made With the

Consent of the Court.

The North Carolina and New Jersey practice, in theory

at least,7 confers upon the trial judge the power to

reject the defendant’s plea, thus forcing him to stand trial

for his life. This, it is said, distinguishes those statutory

procedures from the federal practice condemned in Jack-

son. That conclusion supposes what is not in fact the case,

for under federal practice it is clear that the consent of the

trial judge (and, for that matter, the prosecutor) is re

quired for either a guilty plea or a jury waiver in a Kid

naping Act case. See United States v. Jackson, supra, at

584; Singer v. United States, 380 U. S. 24 (1965); Lynch

v. Overholser, 369 U. S. 705, 719 (1962); see also United

States v. Cox, 342 F. 2d 167, 190-193 (5th Cir. 1965) (Wis

dom, J., concurring).

The point, of course, is that the judge’s power to reject

the defendant’s life-assuring plea and its incidental waiver

7 The opinion of Justice Jacobs and Hall, dissenting in State

v. Forcella, supra, 52 N. J. at 294, tells us what the majority of

the court in that case neither affirms nor denies—namely, that

the theoretical power of New Jersey trial judges to reject a

proffered non vult plea is “seldom exercised where the prosecutor

has recommended its acceptance.”

14

of federal rights is simply irrelevant. Even if North Caro

lina and New Jersey trial judges may and occasionally do

reject the plea, the defendant is still encouraged to attempt

or offer to plead guilty on the hope that his plea will be

accepted and his salvation thus secured. On the one hand,

“ the defendant convicted by a jury automatically incurs

a risk that the same jury will recommend the death pen

alty . . . ” ( United States v. Jackson, 390 U. S. at 573, n.

6 ); on the other, he “ completely escapes the threat of capi

tal punishment unless the trial judge makes an affirmative

decision” (id.) to subject him to it by rejecting his offer

to plead guilty. As Jackson makes unmistakably clear,

this differential risk of capital punishment is unconstitu

tional.

(3) The Waiver of Jury Trial Alone Does Not Avoid the

Possible Imposition of the Death Penalty. In North Caro

lina and New Jersey, the defendant who pleads not guilty

to a capital crime cannot avoid the possible imposition of

the death penalty by waiving his right to a jury trial, as

could a defendant pleading not guilty under the Federal

Kidnaping Act. The New Jersey Supreme Court thought

this enough to distinguish Jackson even though North

Carolina and New Jersey defendants could avoid any pos

sibility of the death penalty—as could federal defendants

under the Kidnaping Act—by entering a plea of guilty.

State v. Forcella, supra, at 269-270. This narrow view of

Jackson has not, to our knowledge, found acceptance in any

other court. It is inconsistent with the decision of the

South Carolina Supreme Court in State v. Harper, 162

S. E. 2d 712 (1968),8 and, of course, with that of the Fourth

8 The South Carolina Supreme Court found that the statutory

provisions challenged in Harper allowed a defendant to escape the

15

Circuit in Alford. I f the distinction taken by the New

Jersey Court prevails, it will deprive Jackson of all mean

ing with respect to the capital sentencing practices of

the states.9 But it cannot prevail without distortion of the

principles discussed in Jackson and of the constitutional

values on which that decision rests.

To begin with, the premise of the New Jersey Supreme

Court that only the Fifth Amendment right to deny and

contest guilt, and not the Sixth Amendment right to jury

trial, is involved is simply incorrect. By pleading guilty—•

the only method in North Carolina and New Jersey by

risk of the death penalty by pleading guilty with the approval of

the trial court. On a not guilty plea, a jury might impose capital

punishment. The question of waiver of jury trial on the plea of

not guilty was not involved. This scheme, the Court held, was

condemned by Jackson; and it resolved the constitutional dilemma

by voiding the provision which excluded the death penalty on a

guilty plea. Harper arose, as did Jackson, on a pretrial motion;

thus, the South Carolina court was not required to decide the

implications of its holding for condemned men who, like amici,

pleaded not guilty and were sentenced to death during the period

when they might still have escaped that sentence by a guilty plea.

9 Our research has disclosed no States in which the defendant

may avoid the death penalty by waiving his right to a jury trial

and accepting court trial on a not guilty plea. There are to our

knowledge seven states in which a capital defendant may avoid

the death penalty by pleading guilty: they are (1) Louisiana

(La. Code of Grim. Proc. Art. 557); (2) Mississippi (Miss. Code

§§2217, 2536; see Bullock v. Harpole, 102 So. 2d 687 (1958));

(3) New Jersey (N. J. S. A. §§2A:113-3, 113-4); (4) New York

(N. Y. Code of Grim. Proc. §3321) ; (5) North Carolina (N. C.

Gen. Stat. §15-162.1) ; (6) South Carolina (S. C. Code §17-553.4

(1967) Cum. Supp.); and (7) Wyoming (Wyo. Stat. §7-195)

(kidnaping). See also N. H. Rev. Stat. Ann. §§585.4, 585.5.

We are unsure of the law in the states of Nebraska, see Neb. Rev.

Stat. §28-417 (kidnaping) ; Washington, see Rev. Code of Wash.,

Title 9, §9.52.010 (kidnaping) ; and Texas, see Vernon’s Ann.

Code of Crim. Proc. of Texas, Art. 1.14, as amended, Tex. Acts

1967, p. 1733, ch. 659, §1, effective August 28, 1967.

16

which the defendant can avoid all risk of the death penalty

—the defendant waives all procedural protections which the

Constitution affords defendants in a criminal trial (.Mc

Carthy v. United States, 394 U. S. 459 (1969)), among

them the right to trial by jury. This point was recently

emphasized by the Court in Boykin v. Alabama, —— U. S.

------ , 23 L. Ed. 2d 274, 279 (1969):

“ Several federal constitutional rights are involved

in a waiver that takes place when a plea of guilty is

entered in a state criminal trial. First is the privilege

against compulsory self-incrimination guaranteed by

the Fifth Amendment and applicable to the States by

reason of the Fourteenth. Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U. S.

1. Second is the right to trial by jury. Duncan v.

Louisiana, 391 U. S. 145. Third, is the right to confront

one’s accusers. Pointer v. Texas, 380 U. S. 400.’’

Second, the North Carolina and New Jersey procedures

are, if anything, more destructive of constitutional rights

than that condemned in Jackson. For the federal defen

dant could avoid the death penalty by waiving only his

Sixth Amendment right to jury trial. He might thereby

save his life and yet have some trial—before a judge—at

which he could exercise his Fifth Amendment right to

contest guilt. North Carolina and New Jersej" offer no

such middle ground; their price for avoiding the death

penalty is a waiver of the right to deny and contest guilt,

and thus of all procedural protections (including jury

trial) subsumed within that right.

But even if it could be said that the right to jury trial

is not infringed when the whole of the right to deny and

contest guilt is impaired, we submit that there is no basis

for concluding that the rule of Jackson does not apply

17

whenever a State encourages a waiver of the Fifth Amend

ment right not to plead guilty by taxing a not guilty plea

with the risk of a death sentence. The Court’s careful

opinion in Jackson relies upon the Fifth Amendment

equally with the Sixth Amendment, and the very logic of

the Jackson decision forbids any distinction between Sixth

and Fifth Amendment rights in a fashion which disparages

the latter. Palpably, any holding that a procedure which

permits avoidance of the death penalty by waiver of the

right not to plead guilty is constitutional, although a com

parable procedure involving only waiver of the right to

jury trial is not, would misconceive the relative importance

of the two federal constitutional rights involved in Jackson.

The right not to plead guilty, and the correlative right

to a hearing at which guilt may be contested, is of the

very essence of due process of law. Whatever view one

may hold of the Fourteenth Amendment, and of the de

gree to which it makes applicable to the States the various

substantive provisions of the Bill of Rights, there has never

been any doubt that an opportunity to a hearing at which

to contest guilt is a constitutional essential.

In contrast, it was not until last year that this Court

finally declared that the right to a trial by jury in a crim

inal case was among those rights deemed so essential to

civilized jurisprudence that it must be made applicable to

the States through the Fourteenth Amendment. Duncan v.

Louisiana, 391 U. S. 145 (1968); Bloom v. Illinois, 391 U. S.

194 (1968). But the Court also held that the rule of these

cases would not be retroactively applied (De Stefano v.

Woods, 392 U. S. 631 (1968)), a ruling which emphasized

that, however desirable the right to jury trial, in general,

a fair adjudication of guilt could occur without a jury.

18

Quoting from Duncan in Be Stefano, the Court said: “We

would not assert, however, that every criminal trial—or

any particular trial—held before a judge alone is unfair

or that a defendant may never be as fairly treated by a

judge as he would be by a jury.” 392 TJ. S. at 633-634.

One can therefore fairly conclude only that the suggested

distinction of Jackson reflects either a convoluted appre

ciation of the relative importance of the rights given by

the Fifth and Sixth Amendments or a perverse unwilling

ness to comply with an unwelcome decision of this Court.

As the dissenting judges in Forcella wrote: “ In the field of

federal constitutional law, the decisions of the United

States Supreme Court are of course binding upon all state

courts. Our clear responsibility is to apply those decisions

with due regard for their tenor, principles and goals in

analogous situations with the aim of determining a matter

as we conscientiously believe that Court would if the case

were before it.” Id., 52 N. J. 294-295.10

10 The New Jersey Supreme Court, in rejecting Forcella’s con

tentions, allowed that a contrary ruling would of necessity result

in the invalidation of “plea bargaining.” Id. 52 N. J., at 275-276.

The argument, while manifestly uncompelling, is at least familiar;

the Government’s submission in Jackson included the identical

point. Brief for the United States, United States v. Jackson, 0. T.

1967, No. 85, pp. 6-7. The argument, we think, is obviously one

which manifests disagreement with the Jackson holding, not dis

tinction of it.

In any event, the issue of the constitutionality of plea bargain

ing in general is no more presented here than in Jackson or in

Pope v. United States, 392 U. S. 651 (1968). We therefore see

no need to labor the obvious point that a procedure which assures

a life sentence to the defendant who waives his rights and pleads

guilty, while it threatens with death the defendant who dares to

exercise those rights, is an entirely different animal from the

time-honored practice of plea bargaining in non-capital cases.

Whatever the reach of the evolving doctrine forbidding the impo

sition of a penalty on the exercise of constitutionally guaranteed

rights, surely that doctrine forbids what North Carolina and New

19

The controlling point is simply that, with regard to both

the Fifth and Sixth Amendments, the North Carolina and

New Jersey practices are functionally identical to the fed

eral procedure which this Court held violative of the Con

stitution in United States v. Jackson. Each “needlessly

encourages” (390 U. S., at 583) pleas by subjecting the

accused who seeks to have his guilt determined by jury-

trial to an “ increased hazard” {id., at 572) of capital pun

ishment. Each “ discourage[s],” “ deter[s]” and “ chill[s]”

exercise of the interdependent rights not to plead guilty

and to be tried by a jury. Id. at 581. And each thereby

“needlessly penalizes the assertion of a constitutional

right” {id., at 583).

This conclusion follows a fortiori from the recent decision

in North Carolina v. Pearce,------ - U. S . ------ , 23 L. Ed. 2d

656 (1969). There the Court dealt with the problem of in

creased sentences following a successful appeal and un

successful retrial. The Court, acknowledging that it had

Jersey have done here. We are not on the penumbra of the un

constitutional condition-penalty doctrine where it might be said

that the penalty is relatively insubstantial and further that com

pelling interests of the State justify its imposition. Here the

defendant is called upon to bargain his life as a condition to exer

cising his constitutional rights. As Mr. Justice Frankfurter once

stated for the Court: “ The difference between capital and non

capital offenses is the basis of differentiation in law in diverse

ways in which the distinction becomes relevant.” Williams v.

Georgia, 349 U. S. 375, 391 (1955). For varying exemplifications

of the principle, see, e.g., Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45 (1932) ;

Stein v. New York, 346 U. S. 156, 196 (1952) ; Hamilton v. Ala

bama, 368 U. S. 52 (1961) ; Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391, 439-40

(1963). Jackson does not require the wholesale invalidation of

plea bargaining. It does, however, compel a recognition that the

forfeiture of life is a penalty which may not be imposed on the

exercise of the fundamental constitutional right to deny and con

test guilt on a capital charge. See Note, 54 Cornell L. Rev. 448,

452 (1969).

20

“ never held that the States are required to establish

avenues of appellate review,” held that once established,

those avenues must be kept open and free of unreasoned

distinctions. The Court continued:

“Where . . . the original conviction has been set aside

because of a constitutional error, the imposition of

such a punishment, ‘penalizing those who choose to

exercise’ constitutional rights, ‘would be patently un

constitutional.’ United States v. Jackson, 390 U. S.

570, 581. And the very threat inherent in the existence

of such punitive policy would, with respect to those

still in prison, serve to ‘chill the exercise of basic con

stitutional rights.’ Id., at 582. See also Griffin v. Cali

fornia, 380 U. S. 690; cf. Johnson v. Avery, 393 U. S.

483. But even if the first conviction has been set aside

for nonconstitutional error, the imposition of a pen

alty upon the defendant for having successfully pur

sued a statutory right of appeal or collateral remedy

would be no less a violation of due process of law.”

{Id., at 4605.)11

In these cases, the right to deny and contest guilt—in con

trast to the right of appeal—is specifically guaranteed by

the United States Constitution. To subject a defendant to

11 Amici, unlike the defendants in the present eases, did not

yield to the pressures to waive their right to trial. Bach exercised

that right and each has been sentenced to death—a sentence which

might have been avoided at the cost of waiver of their federal

rights. The question presented in their cases is whether by sub

jecting them to the death penalty, the state is “ ‘penalizing those

who choose to exercise’ constitutional rights, [which] ‘would be

patently unconstitutional.’ ” North Carolina v. Pearce, supra,

quoting from United States v. Jackson, supra, at 581. That ques

tion is not presented here and we do not now consider it; it is

treated extensively in the petitions for certiorari in Forcella (see

pp. 19-38) and in Childs (see pp. 16-25).

21

a greater penalty because he has exercised that right is

the more flagrantly unconstitutional.

(4) The Statute Specifies the Death Penalty Unless the

Jury Affirmatively Recommends a Lesser Sentence.

In some states, North Carolina among them, the perti

nent statute specifies that the penalty for a capital offense

shall be death unless the jury affirmatively recommends a

life sentence. The North Carolina Supreme Court thought

that that form distinguished such procedures from the fed

eral one invalidated in Jackson, where the applicable stat

ute provided for imprisonment unless the jury voted for

the death penalty.

The North Carolina Supreme Court offered no explana

tion as to how this might possibly have any bearing on the

applicability of Jackson’s condemnation of a procedure

which unduly encourages the waiver of the constitutional

right to deny and contest guilt, and we can think of none.

The distinction, we suggest, is entirely semantic.12 Con

gress in the Kidnaping Act established a selective process

of making individuating judgments by which juries had

the option between imposing a death sentence or a sentence

of life or less. This is exactly the same option given North

Carolina juries by the North Carolina Legislature; and the

latter is as unconstitutional as the former. That conclu

sion does not depend on the phrasing of the jury’s role in

12 If the differences in statutory language were in fact of any

consequence, then one would expect that a greater percentage of

North Carolina defendants electing to stand trial would be given

death sentences than federal capital defendants. The pressure,

then, to waive the right to deny and contest guilt and seek the

safe harbor of a guilty plea would be greater in North Carolina

than in a pre-Jackson Federal Kidnaping Act ease, and the uncon

stitutionality of North Carolina’s procedures would be a fortiori.

22

deciding upon the sentence. Quite the contrary, it follows

from the proposition that—however that role may be char

acterized—any defendant may avoid being subjected to the

jury’s death-sentencing option—but only at the cost of

waiving his constitutional rights.

II.

A Guilty Plea, the Making o f Which Was Substantially

Motivated by the Threat o f Imposition o f the Death

Penalty, Is Involuntary and Cannot Stand.

Introduction

Having concluded that the North Carolina death penalty

statutes are unconstitutional,13 we are nevertheless impelled

to acknowledge, as did the Court of Appeals in Alford,

that the presence of an unconstitutional sentencing system

such as North Carolina’s does not, of itself, resolve these

cases. As the Court of Appeals said in Alford, “a defen

dant who has pleaded guilty when charged with a capital

offense in North Carolina is not necessarily entitled to

post-conviction relief as a matter of law.” 405 F. 2d, at

347. The court recognized that this Court refrained in

Jackson from holding that every plea of guilty to a Federal

13 It should be noted that, effective March 25, 1969, the N. C.

Legislature resolved the Jackson problem in its statutory scheme

by repealing the provision permitting a guilty plea to a capital

offense and fixing the penalty upon such a plea at life imprison

ment. N. C. Session Laws, 1969, Ch. 117. See State v. Atkinson,

------N. C .------- , 167 S. E. 2d 241, 258-259 (1969). This resolution

in futnro, of course, can have no effect on the capital sentencing

provisions in force at the time of these defendants’— and of amici’s

—prosecutions, or on their constitutional posture. See note 4,

supra.

23

Kidnaping Act charge was involuntary.14 The question of

the validity of such guilty pleas is, we submit, one of fact;

it cannot be resolved other than by a full and fair eviden

tiary hearing, at which a sensitive and probing analysis

of the motivations of the plea is made within the frame

work of the applicable presumptions and rules assigning

the burden of proof.

We turn now to the issues controlling the pleas chal

lenged in the cases at bar. In subpart A of this section, we

discuss the settled requirement that a guilty plea must be

knowing and “voluntary,” and the application of that princi

ple to a case in which the threat of the death penalty has

played a role in eliciting such a plea. In subpart B, we

offer a suggested approach for testing guilty pleas made

in cases such as these to determine whether the threat of

the death penalty has deprived the plea of its voluntary

quality.

A. The Threat of the Death Penalty May Deprive a Guilty

Plea of Its Voluntary Character.

This Court has long been concerned (see, e.g., Kercheval

v. United States, 274 U. S. 220 (1927)) to insure that guilty

pleas be not made involuntarily. The question of voluntari

ness of a plea is a federal one (Boykin v. Alabama, ------ -

IJ. S . ------ , 23 L. Ed. 2d 274 (1969), as is any question of

the waiver of federally secured rights. E.g., Douglas v. Ala

bama, 380 U. S. 415 (1965); Brookhart v. Janis, 384 U. S.

1, 4 (1966); O’Connor v. Ohio, 385 U. S. 92 (1966). Special

14 “ [T]he fact that the Federal Kidnaping Act tends to discour

age defendants from insisting upon their innocence and demand

ing trial by jury hardly implies that every defendant who enters a

guilty plea to a charge under the Act does so involuntarily.” 390

U. S., at 583.

24

caution regarding the guilty plea is entirely fitting, for a

guilty plea constitutes a waiver of all constitutionally se

cured procedural guarantees (see pp. 15-16, supra) ; thus

this Court recently observed that a guilty plea “ demands

utmost solicitude of which courts are capable” (Boykin v.

Alabama, supra, at 280) to ensure that the waiver is truly

voluntary.

The cases prohibiting involuntary pleas do not confine

themselves to coercion by physical force or threats of vio

lence; the inducement deemed so great to vitiate a plea

“ can be ‘mental as well as physical;’ ‘the blood of the

accused is not the only hallmark of an unconstitutional in

quisition.’ Blackburn v. Alabama, 361 U. S. 199. . . . Subtle

pressures (Leyra v. Denno, 347 U. S. 556; Haynes v. Wash-

ington, 373 U. S. 503) may be as telling as coarse and

vulgar ones.” Garrity v. New Jersey, 385 U. S. 493, 496

(1967).

Some pressures are deemed too great to permit their in

trusion into the process by which the defendant determines

whether to exercise his constitutional right to deny and

contest guilt or to enter a plea of guilty. The prospect of

an apparently unavoidable deprivation of constitutional

rights at trial, for example, may be sufficient to destroy the

voluntariness of the plea, as where a defendant pleads guilty

in the face of a trial wherein he is threatened by an un

constitutionally obtained confession. E.g., United States

ex rel. Ross v. McMann, 409 F. 2d 1016 (2nd Cir. 1969)

(en banc); United States ex rel. Collins v. Maroney, 382

F. 2d 547 (3rd Cir. 1967); Smith v. Wainwright, 373 F. 2d

506 (5th Cir. 1967); Carpenter v. Wainwright, 372 F. 2d

940 (5th Cir. 1967); Murphy v. Wainwright, 372 F. 2d 942

(5th Cir. 1967); Doran v. Wilson, 369 F. 2d 505 (9th Cir.

25

1966); Ellis v. Boles, 251 F. Supp. 1021 (N. D. W. Va.

1966); United States ex rel. Cuevas v. Bundle, 258 F. Supp.

647 (E. D. Pa. 1966). Misrepresentations by the prosecutor

(for example, as to his ability to insure the defendant a

particular sentence) are another example of circumstances

which will warrant setting aside a plea of guilty. E.g.,

Machibroda v. United States, 368 U. S. 487 (1962); Walker

v. Johnston, 312 IT. S. 275 (1941); Dillon v. United States,

307 F. 2d 445, 449 (9th Cir. 1962); Teller v. United States,

263 F. 2d 871 (6th Cir. 1959). The same is true of unkept

judicial promises of leniency. E.g., Smith v. United States,

321 F. 2d 954 (9th Cir. 1963); United States ex rel. Elksnis

v. Gilligan, 256 F. Supp. 244 (S. D. N. Y. 1966) (Weinfeld,

J .) ; cf. Workman v. United States, 337 F. 2d 226 (1st Cir.

1964).

Equally impermissible are prosecutorial threats to prose

cute the spouse or a close friend of the defendant unless

he pleads guilty. Johnson v. Wilson, 371 F. 2d 911 (9th

Cir. 1965); United States v. Glass, 317 F. 2d 200 (4th Cir.

1963); Conley v. Cox, 138 F. 2d 786 (8th Cir. 1943); cf.

Teller v. United States, supra. Indeed, statements of the

trial judge to the effect that if the defendant elects to stand

trial and is convicted, he will be given the maximum sen

tence have been found to invalidate a guilty plea as a mat

ter of law. Euziere v. United States, 249 F. 2d 293 (10th

Cir. 1957); United States v. Tateo, 214 F. Supp. 560 (S. D.

N. Y. 1963).

Of course guilty pleas, properly interposed, are an essen

tial ingredient of the efficient administration of justice.

What these cases teach, however, is that certain kinds of

inducements are too pressureful, too insensitive of the right

of defendants to elect freely whether or not to stand trial.

26

Those inducements, for that reason, do not pass constitu

tional muster. It is in this context that the role of the death

penalty must be assessed.

Much of the analysis has already been performed by this

Court in United States v. Jackson, supra. This Court there

found that statutes such as North Carolina’s “needlessly

encourage” (390 U. S., at 583) guilty pleas and, as we show

in Part I, supra, are unconstitutional. Identification of the

potentially coercive force of the death penalty in Jackson

was in accordance with an increasing recognition that the

risks of standing trial are “made particularly perilous in

the context of [a] . . . charge with a possible death penalty.”

United States ex rel. Ross v. McMann, 409 F. 2d 1016 (2d

Cir. 1969) (en banc). Accord: Smith v. Wainwright, 373

P. 2d 506, 507 (5th Cir. 1967) (“ He was told that if he

pleaded not guilty, the confession would place him in danger

of the electric chair” ) ; Carpenter v. Wainwright, 372 F. 2d

942 (5th Cir. 1967); United States ex rel. Cuevas v. Rundle,

258 F. Supp. 647 (E. D. Pa. 1966).

It bears emphasis that the constitutionality of a fairly

administered system of plea bargaining is not implicated

by a recognition of the coercive quality of the threatened

imposition of the death penalty. See note 10, supra. All

that need be determined here is that no defendant may be

compelled to gamble with his life to secure his constitutional

right to a trial; the state may not use the death penalty as

the basis for inducing guilty pleas.

B. Standards for Determining the Validity of a Potentially

Death Penalty-Induced Guilty Plea=

We begin from the premise that in each of these cases

the plea was entered within the framework of a statutory

system of differential sentencing in capital cases which is

unconstitutional. See Part I, supra. The suspicion is in-

27

evitable, and entirely fitting, that the decision of each de

fendant to enter a plea of guilty was motivated by a desire

to take advantage of the differential sentencing scheme

enacted by the North Carolina Legislature and thereby

avoid the death penalty. Each of these pleas, then, is con

stitutionally suspect. See Part 11(A), supra.

Boykin v. Alabama, —— U. S. ------ , 23 L. Ed. 2d 274

(1969) compels the setting aside of any such plea where

the record lacks “ an affirmative showing that [the plea]

was intelligent and voluntary.” Id., at 279. These cases

are undeniably stronger ones for insisting upon such a

requirement than was Boykin, in which (as the dissenters

pointed out, see id. at 281) there was no specific allegation

that Boykin’s plea was involuntary and, certainly, no de

fects in the statutory framework within which the plea was

entered that might raise a presumption (or even suspicion)

that his plea was other than voluntary. Yet the Court in

sisted that any guilty plea, constituting as it does a waiver

of all constitutionally secured procedural safeguards (see

pp. 15-16, supra), be supported by an affirmative showing

on the record that the plea was knowing and voluntary.16

16 We do not overlook that this Court has not yet determined

whether Boykin is to be given retroactive application. However

that question may be resolved (and presumably Halliday v. United

States, 394 U. S. 831 (1969) (per curiam) suggests that the

outcome may well be that it will not be retroactively applied),

these pleas should not be allowed to stand. Unlike the Boykin

and Halliday cases, there was here, as we have said, an uncon

stitutional statutory scheme within which the pleas in each of

these cases were entered, as a result of which each is presump

tively bad. These circumstances focus our concern as to the con

stitutionality of these pleas of guilty far more narrowly than is

the case as to guilty pleas generally, entered in a less coercive

framework. While the Court in Halliday could thus conclude that

the other remedies available to the relatively rare defendant whose

guilty plea may be invalid offered sufficient protection, the same

cannot be said in states such as North Carolina where guilty pleas

in capital eases are presumptively involuntary because of the coer

cive force of the differential sentencing system.

2 8

In neither of these cases16 does it affirmatively appear from

the record that the plea was other than impelled by a desire

to avoid the death penalty, and for that reason neither plea

should be allowed to stand.

At the least, a defendant who has entered a plea within

a statutory framework such as North Carolina’s is entitled

to an evidentiary hearing at which the voluntariness of his

plea is determined. Conceivably, it might be shown at such

a hearing that the plea was the product of wholly proper

considerations. It will not do, however, simply to allow the

defendant the opportunity to demand such a hearing and

impose upon him the customary burden of proof imposed

upon one seeking to set aside a conviction. Here the burden

must be shifted, for the plea was entered in suspicious

circumstances that render it presumptively bad. The like

lihood that it was motivated by improper pressures is so

great that the burden of showing that it was not must

fasten upon the State. Cf. Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U. S.

436 (1966). This approach recognizes the constitutional

values implicit in Boykin, while leaving it open to the State

to show that, notwithstanding the inevitable suspicion that

the plea was the improper product of the unconstitutional

differential sentencing system, it was in fact motivated by

different, and permissible, considerations. 16

16 In Alford, the record in the original state proceedings lends

affirmative support to the contrary proposition, and of course that

conclusion is fully supported by the collateral proceedings culmi

nating in the determination of the Court of Appeals that the “in

centive supplied to petitioner to plead guilty by the North Carolina

statutory scheme was the primary motivating force to effect tender

of the plea, especially since throughout the proceedings the peti

tioner has protested his innocence.” 405 F. 2d, at 349. In Parker,

there is nothing in the record of the proceedings at which he en

tered his plea which indicates that the plea was motivated by any

thing other than a desire to avoid the death penalty.

29

Application of these principles to the facts of the present

cases leaves no doubt as to the outcome. Alford must be

affirmed, the court below having affirmatively found after a

plenary hearing that the plea was motivated “ primar

ily” to avoid the death penalty and that the defendant had

throughout insisted upon his innocence. The record amply

supports this factual finding, and no reason appears for

this Court to disturb it on appeal. In Parker, it does not

appear that the courts of North Carolina considered the

defendant’s claim that his plea was improperly induced by

the state’s unconstitutional sentencing system in the light

of the proper standards for trial of that issue suggested

here. To the contrary, the North Carolina Court of Ap

peals seems simply to have concluded that the plea was

voluntary because the North Carolina statute was not un

constitutional under United States v. Jackson, supra, a con

clusion which is plainly unsupportable. Thus, the Parker

case should be vacated and remanded for reconsideration,

in light of this Court’s determination that the North Caro

lina statutes provide an unconstitutional inducement to

plead guilty, for an evidentiary hearing at which the State

will be required to demonstrate affirmatively the voluntari

ness of the plea under the appropriate federal constitu

tional standards, or see it set aside.17

17 Such a holding would not necessarily imply retroactivity of

United States v. Jackson. Compare note 15, supra. This Court

would he resting its decision upon the long-settled law of the Con

stitution that an involuntary guilty plea is invalid. In testing the

validity of the defendants’ pleas, it would be drawing upon the

insights and reasoning processes of Jackson, not the legal rule of

that case, in the same fashion that the Court has applied retroac

tively the insights of Miranda, see Davis v. North Carolina, 384

U. S. 737 (1966), albeit not its rule, see Johnson v. New Jersey,

384 U. S. 719 (1966).

We do not develop this retroactivity question here because—-

whatever view be taken of the retroactivity of Jackson in guilty-

plea cases such as those of the defendants in the cases at bar—

entirely different considerations control the matter of Jackson’s

30

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G-reenberg

J ames M . N abrit, III

M ichael M eltsner

N orman A maker

J ack H im m elstein

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Charles S teph en R alston

1095 Market Street

San Francisco, California 94108

A n t h o n y Gf. A msterdam

Stanford University School of Law

Stanford, California 94305

J erome B. F al k , J r .

650 California St., Rm. 2920

San Francisco, California 94102

J. L e V onne Chambers

J ames E. F erguson, II

J ames E. L an n in g

216 West Tenth Street

■Charlotte, North Carolina

application to persons situated like amici, complaining of death

sentences which would penalize them for their exercise of con

stitutional rights. See Petition for Writ of Certiorari in Forcella

and Funicelio v. New Jersey, supra, at 36-37; see also note 4,

supra.

RECORD PRESS, INC., 95 MORTON ST., NEW YORK, N. Y. 10014, (212) 243-5775