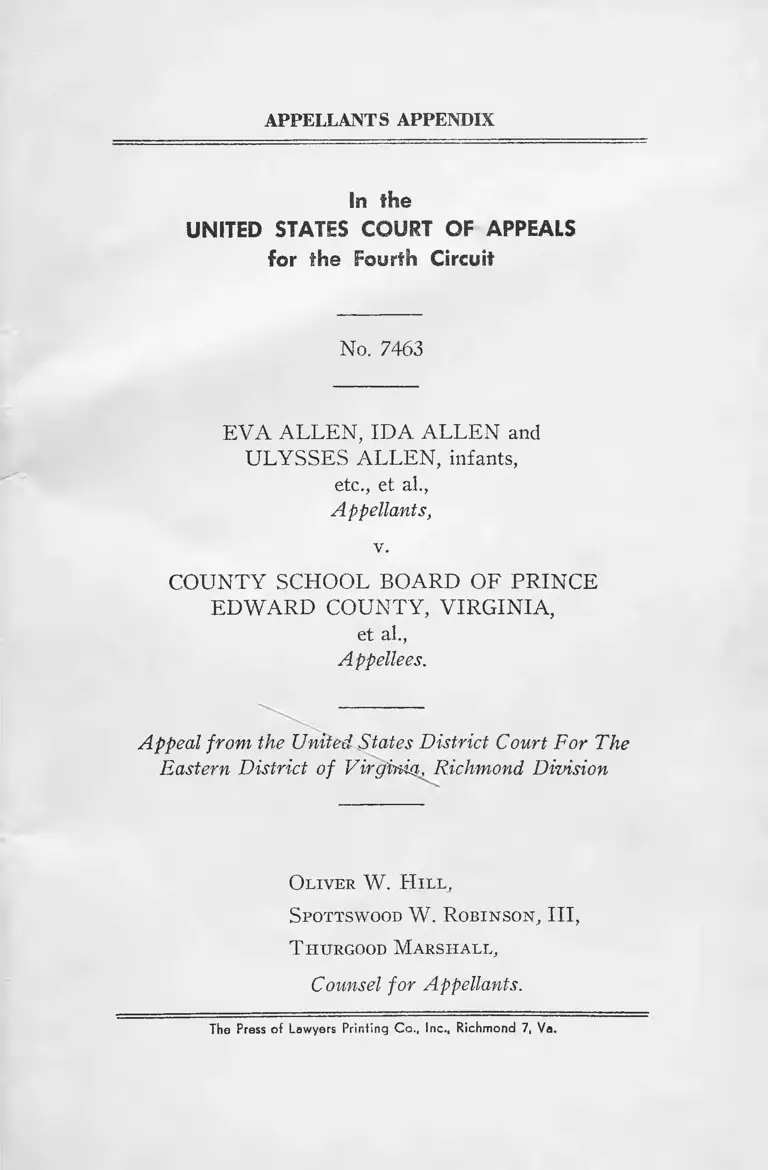

Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward County Appellants Appendix

Public Court Documents

January 23, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward County Appellants Appendix, 1957. f5b0ed8b-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b3441a96-d727-471b-98a0-85c0f3b2c757/allen-v-county-school-board-of-prince-edward-county-appellants-appendix. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

APPELLANTS APPENDIX

In the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 7463

EVA ALLEN, IDA ALLEN and

ULYSSES ALLEN, infants,

etc., et al.,

Appellants,

v.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE

EDWARD COUNTY, VIRGINIA,

et al.,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court For The

Eastern District of Viryinieh Richmond Division

O l iv e r W. H il l ,

S po x tsw o o d W. R o b in s o n , III,

T h u r g o o d M a r s h a l l ,

Counsel for Appellants.

The Press of Lawyers Printing Co., Inc., Richmond 7, Va.

INDEX

Page

Mandate .......................................................................... 2

Motion for Hearing on Formulation of Decree and

Judgment...................... 1

Intervenors’ Complaint in Intervention ......................... 5

Petition of Defendants........................................... 10

Order on Mandate ........................................-............... 14

Motion for Further Relief ............................................. 15

Answer to Motion for Further Relief................ 24

Supplemental Answer and Motion to Dismiss Motion

for Further Relief ....... 28

Opinion ........ 29

Order .............................................................................. 48

In the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 7463

EVA ALLEN, IDA ALLEN and

ULYSSES ALLEN, infants,

etc., et al.,

Appellants,

v.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE

EDWARD COUNTY, VIRGINIA,

et al.,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court For The

Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Division

APPELLANTS APPENDIX

MOTION FOR HEARING ON FORMULATION OF

DECREE AND JUDGMENT

[R. p. 6]

Plaintiffs in the above entitled case respectfully move

the Court to set this case for an early hearing for the

[ 2 ]

purpose of formulating and entering a decree in conformity

with the decisions of the Supreme Court of the United

States heretofore rendered in this action.

MANDATE

[R. pp. 2-5]

United States of America, ss

The President of the United States of America,

To the Honorable The Judges of the United States District

Court For the Eastern District of Virginia

G r e e t in g

Whereas, lately in the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Virginia, before you, or some of

you, in a cause between Dorothy E. Davis, Bertha M.

Davis, and Inez D. Davis, etc., et al., Plaintiffs, and County

School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, et ah,

Defendants, Civil Action, No. 1333, wherein the judgment

of the said District Court, entered in said cause on the

7th day of March, A. D. 1952, is in the following words,

viz:

“This cause came on to be heard upon the complaint,

the answer of the original defendants, as well as the

answer of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the inter

vening defendant, and upon the evidence, oral and

documentary, adduced by all parties, and was argued

by counsel.

Upon consideration whereof, the Court, for the

reasons set forth in its written opinion filed herein,

hereby

1. (a) Denies the prayer of the complaint that the

Court declare the provisions of section 140, Constitu

tion of Virginia of 1902, as amended, and section 22-

221, Code of Virginia of 1950, as amended, as invalid

and in conflict with the statutes or Constitution of

the United States; and

(b) Adjudges and Declares that the buildings,

facilities, curricula and means of transportation fur

nished for the education of the Negro high school

students in Prince Edward County, Virginia, are not

substantially equal to [fo il 103] those provided for

the white high school students in said county; and

hereby

2. Adjudges, Orders and Decrees that the defend

ants, their officers, agents, servants, employees and

attorneys, and all persons in active concert or partici

pation with them be, and they are hereby, forthwith and

perpetually enjoined and restrained from continuing

to provide, or maintaining, curricula and means of

transportation for the white high school students in

said county without providing and maintaining substan

tially equal curricula and means of transportation to

the Negro high school students of said county; and it

is further

3. Adjudged, Ordered and Decreed that the said

defendants proceed with all reasonable diligence and

dispatch to remove the unequality existing as aforesaid

in said buildings and facilities, by building, furnishing

and providing a high school building and facilities for

Negro students, in accordance with the program men

tioned in said opinion and in the testimony on behalf

of the defendants herein, or otherwise; and it is also

[ 4 ]

4. Ordered that the plaintiffs recover their costs of

the defendants.

Nothing further remaining to be done in this cause,

it is stricken from the docket.

Armistead M. Dobie, United States Circuit Judge,

Sterling Hutcheson, United States District Judge;

Albert V. Bryan, United States District Judge.”

as by the inspection of the transcript of the record of the

said District Court, which was brought into the

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES by

virtue of an appeal, agreeably to the act of Congress, in

such case made and provided, fully and at large appears.

And whereas, in the present term of October, in the

year of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and fifty-

four, the said cause came on to be heard before the said

SUPREME COURT, on the said transcript of record,

and was argued by counsel;

On consideration whereof, It is ordered and adjudged by

this Court that the judgment of the said District Court,

in this cause be, and the same is hereby, reversed with

costs; and that the said plaintiffs, Dorothy E. Davis, et ah,

recover from the said defendants two thousand nine hun

dred seventy-five dollars and nineteen cents ($2,975.19)

for their costs herein expended.

AND IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that this cause

be, and the same is hereby, remanded to the said District

Court to take such proceedings and enter such orders and

decrees consistent with the opinions of this Court as are

necessary and proper to admit to public schools on a racially

nondiscriminatory basis with all deliberate speed the parties

to this case.

May 31, 1955.

You, therefore, are hereby commanded that such pro

ceedings be had in said cause, in conformity with the

opinions and judgment of this Court, as according to right

and justice, and the laws of the United States, ought to

he had, the said appeal notwithstanding.

Witness the Honorable EARL WARREN, Chief Justice

of the United states, the twenty-seventh day of June, in

the year of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and fifty-

five.

H a r o ld B. W il l e y ,

Clerk of the Supreme Court of the

United States

By Hugh W. Barr,

Deputy

INTER VENTERS’ COMPLAINT IN

INTERVENTION

[R. pp. 13-16]

[Caption Omitted]

CIVIL ACTION

NO. 1333

DOROTHY E. DAVIS, BERTHA M. DAVIS and

INEZ D. DAVIS, infants, by John Davis, their father

and next friend, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE EDWARD

COUNTY, VIRGINIA, et al.,

Defendants,

EVA ALLEN, IDA ALLEN and ULYSSES ALLEN,

infants, by Hal Edward Allen, their father

and next friend,

MARILYN L. DUPUY, IRENE DUPUY and

EDWARD F. DUPUY, infants, by Charlie

Dupuy, their father and next friend,

JOHN A. EARLEY, LAWRENCE A. EARLEY, and

JOE L. EARLEY, infants, by Susie Earley, their

mother and next friend,

MAXINE MORGAN and DELORES MORGAN,

infants by Thomas Hall, their guardian and next

friend,

SAMUEL S. HALL, LEON O. HALL and ROSETTA

C. HALL, infants, by Harry S. Hall, their father

and next friend,

CHARLES HICKS and ROY HICKS, infants, by C. W.

Hicks, their father and next friend,

FRANKLIN R. HICKS and RUBY M. HICKS, infants,

by Sarah Elizabeth Hicks, their mother and

next friend,

LORNELL SHEPPERSON, an infant, by P. H.

Shepperson, her father and next friend,

m

HAROLD BAGLEY and MCDARNOLD BAGLEY,

infants, by P. H. Shepperson, their guardian and

next friend,

JAMES SCOTT, an infant, by Otis Scott, his father and

next friend,

ROBERT THOMPSON, an infant, by W. Howard

Thompson, his, father and next friend,

EVA I. WILLIAMS and ALICE M. WILLIAMS,

infants, by Frank Williams, their father and

next friend,

Interveners.

INTERVENERS’ COMPLAINT IN

INTERVENTION

The above-named interveners, for their complaint in

intervention, adopt all of the allegations of the complaint

herein, and, in addition thereto, allege as follows:

1. Interveners are among those generally classified as

Negroes, are citizens of the United States and of the Com

monwealth of Virginia, and are residents of and domiciled

in the County of Prince Edward, Virginia. They are with

in the statutory age limits of eligibility to attend the public

secondary schools of said County and possess all qualifica

tions and satisfy all requirements for admission thereto.

They are children or wards, who had not completed the

public elementary schools when this action was filed, of

adults who are parties-plaintiff in this action.

2. Defendants, and each of them, and their agents and

employees, maintain and operate separate public secondary

schools for Negro and white children, respectively, and deny

[ 8 ]

interveners and all other Negro children, because of their

race or color, admission to and education in any public

secondary school operated for white children, and compel

interveners and all other Negro children, because of their

race or color, to attend a public secondary school set apart

and operated exclusively for Negro children, in the en

forcement and execution of Article IX, Section 140, of

the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and

Title 22, Chapter 12, Article 1, Section 22-221 of the Code

of Virginia of 1950, and/or pursuant to a policy, practice,

custom and usage of segregating, on the basis of race or

color, all children attending the public secondary schools

of said County.

3. The aforesaid action of defendants, and each of them,

denies interveners, and each of them, their liberty with

out due process of law and the equal protection of the

laws secured by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Con

stitution of the United States, Section 1.

4. Notwithstanding that the discriminations aforesaid

have been of long standing, and have been the subject

of complaint to defendants and their predecessors in office

upon numerous occasions in the past, and notwithstanding

that plaintiffs, in their own behalf and in behalf of all

other persons, citizens and residents of the County of Prince

Edward, Virginia, similarly situated, have heretofore

formally requested and demanded that defendants, and each

of them, cease and desist therefrom, defendants, and each

of them, refuse to act favorably upon said requests or

demands, and will continue to refuse to admit them to, or

enroll or educate any of them in, the public secondary

schools maintained and operated in said County without

regard to their race or color.

5. Defendants, and each of them, will continue to pursue,

and to enforce and execute against interveners., and all

other Negro children similarly situated residing in the

County of Prince Edward, Virginia, the laws and/or the

policies, practices, customs and usages specified in para

graph 2 hereof, and will continue to deny them admission,

enrollment and education to and in any public secondary

school established, maintained and operated for children

residing in said County who are not Negroes, unless re

strained and enjoined by this Court from so doing.

6. Interveners, and those similarly situated and affected,

are suffering irreparable injury and are threatened with

irreparable injury in the future by reason of the policies,

practices, customs and usages and the actions of defend

ants herein complained of. They have no plain, adequate

or complete remedy to redress the wrongs and illegal acts

herein complained of other than this complaint for an in

junction. Any other remedy to which interveners and those

similarly situated could be remitted would be attended by

such uncertainties and delays as to deny substantial relief,

would involve a multiplicity of suits, and would cause fur

ther irreparable injury and occasion damage, vexation and

inconvenience.

WHEREFORE, interveners respectfully pray that, upon

the filing of this complaint, as may appear proper and

convenient, this Court advance this action on the docket

and order a speedy hearing of this action according to

law, and that upon such hearing:

1. This Court grant to interveners all of the relief

prayed for in the original complaint herein.

2. This Court allow interveners their costs herein, and

grant such further, other, additional or alternative relief

[ 10 ]

as may appear to be equitable and just in the premises.

PETITION OF DEFENDANTS

[R. pp. 19-22]

The defendants in this cause, by counsel, respectfully

show the Court:

(1) On August 30, 1954, following the decision of the

Supreme Court of the United States on May 17, 1954,

the Governor of Virginia appointed a Commission on Public

Education to consider a course of future action in the light

of the Supreme Court’s decision. The Commission consists

of 32 members of the General Assembly of Virginia. It

has met from time to time on numerous occasions since

its appoinment and has announced that it is in the process

of formulating a legislative program to be presented to

the General Assembly of Virginia to govern the future

operation of the public schools in the State of Virginia.

The Commission has not yet announced the legislation it

will propose, but is continuing with its work with as much

expedition as the magnitude and complexity of the problems

confronting it will permit. The facts as to the action of

the Commission appear from the affidavit of Dowell J.

Howard and from a copy of the Commission’s interim re

port of June 10, 1955, which are attached hereto as Exhibit

1. The conclusion of the Commission is as follows:

“In the circumstances it is the recommendation of

this Commission that Your Excellency and the State

Board of Education declare that it is the policy of

[ 1 1 ]

the State to continue schools throughou the school year

1955-1956 as presently operated. Further, it is the

judgment of this Commission that an adjustment, at

this time, to a school system not based on race would

not be practicable or feasible from an adminstrative

standpoint or otherwise.

“Your Commission will continue its work and sub

mit a further report at its conclusion. The report will

contain specific bills for enactment by the General As

sembly. For the foregoing reasons, it is the view of

the Commission that an extra session of the General

Assembly should not be called at this time.”

(2) Thereafter on June 23, 1955, the Governor of

Virginia and the State Board of Education met together to

consider the problems raised by the decision of the Supreme

Court in this case of May 31, 1955. After the meeting

a joint statement was issued which is appended to Exhibit

1 to the effect that the State Board of Education and local

political subdivisions cannot initiate a plan consistent with

the ruling of the Supreme Court until the General Assembly

has enacted appropriate legislation to be recommended by

the Commission on Public Education. Accordingly, the

Governor and the State Board of Education adopted as

a State policy that the local school authorities to the extent

possible should open and operate the public schools through

out the session 1955-1956 on the same basis as they have

heretofore been operated.

(3) The determination by the State Board of Educa

tion that immediate integration of the races in the public

schools during the session 1955-1956 is impossible is amply

supported by the facts. The Supreme Court of the United

States has recognized that problems relating to administra

tion, physical condition of school plants, the transportation

of pupils, personnel, revision of school districts and at

tendance areas will require time for adjustment. Even if

no further legislation were required and if immediate in

tegration were possible in Virginia, the necessary adjust

ments could not be accomplished in time for the operation

of integrated schools during the session 1955-1956. But

there is also the necessity for revision of State statutes,

and the General Assembly of Virginia cannot act with the

speed of a private individual. Accordingly, it is factually

impossible to operate racially integrated schools during the

session 1955-1956, and the only way in which schools can

be operated during that session is on the basis on which

they have heretofore been operated.

In regard to the facts alleged in the preceding para

graphs, attention is invited to Exhibit 1 filed herewith.

(4) The difficulties faced by the State of Virginia as

a whole are met with particular intensity in Prince Edward

County. The facts as to the operation of schools in Prince

Edward County during the session 1955-1956 and as to

the events that have occurred there since this case was

last before this Court are detailed in the affidavit of Thomas

J. Mcllwaine, attached hereto as Exhibit 2, and the affi

davit of B. Calvin Bass, attached hereto as Exhibit 3. A

review of those affidavits will make it clear to the Court

that the schools of Prince Edward County cannot be op

erated on an integrated basis during the session 1955-1956.

(5) The State of Virginia is proceeding with all de

liberate speed to accommodate the administration of its

public school system to the new conditions resulting from

the decision of the Supreme Court in this case. The method

of operation of the schools in Prince Edward County cannot

be changed until appropriate action has been taken on the

State level to accomplish necessary legislative changes and

to establish a new pattern for public school operation. If

the Court should direct that the high schools in Prince

Edward County be operated during the session 1955-1956

otherwise than in the manner in which they have heretofore

been operated, the school authorities of Prince Edward

County will have no alternative other than to close the

schools in the County during the session 1955-1956 to the

lasting detriment of the school children of both races.

Accordingly, the defendants petition the Court that it

enter an order that

i will permit the operation of the high schools in Prince

Edward County, Virginia, during the session 1955-1956

as heretofore operated pending the further order of this

Court; and

ii will require the defendants to report to this Court

not later than August 1, 1956, the steps that they have

taken to adjust to the decision of the Supreme Court of

the United States in this case; and

in will continue this case on the docket of the Court

pending the filing of such report.

The defendants are prepared to present testimony in

support of the allegations of fact contained in this petition.

[Exhibits Omitted]

[ 1 4 ]

ORDER ON MANDATE

[R. pp. 44-46]

This cause came on to be heard upon the papers and

orders heretofore filed, upon the mandate of the Supreme

Court of the United States received on June 28, 1955,

upon the motions of the plaintiffs for the formulation and

entry of a decree on the said mandate, and upon the petition

of the defendants, as well as the drafts of the decrees

proposed by each side, and was argued by counsel.

Upon consideration whereof the Court is of the opinion

that the said mandate requires it to, and accordingly it

does hereby,

ADJUDGE, ORDER, DECLARE and DECREE:

1. That the decree entered by this Court on the 7th day

of March, 1952, be, and it is hereby, vacated and set aside

to the extent that it denies the prayer of the complaint

herein for a declaration that section 140, Constitution of

Virginia of 1902, as amended, and section 22-221, Code

of Virginia of 1950, as amended, insofar as they direct

that white and colored persons shall not be taught in the

same school, are unenforceable because invalid as in con

flict with the statutes or Constitution of the United States;

2. That insofar as they direct that white and colored

persons, solely on account of their race or color, shall not

be taught in the same schools, neither said section 140,

Constitution of Virginia of 1902, as amended, nor said

section 22-221, Code of Virginia of 1950, as amended,

shall be enforced by the defendants, because the provisions

of said sections are in violation of the clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

1. 15]

forbidding any State to deny to any person within its juris

diction the equal protection of the laws;

3. That the defendants be, and they are hereby, re

strained and enjoined from refusing on account of race

or color to admit to any school under their supervision

any child qualified to enter such school, from and after

such time as the defendants may have made the necessary

arrangements for admission of children to such school on

a nondiscriminatory basis with all deliberate speed as re

quired by the decision of the Supreme Court in this cause;

but the Court finds that it would not be practicable, because

of the adjustment and rearrangement required for the pur

pose, to place the Public School System of Prince Edward

County, Virginia, upon a nondiscriminatory basis before

the commencement of the regular school term in September

1955, as requested by the plaintiffs, and the Court is of

the opinion that the refusal of the Court to require such

adjustment and rearrangement to be made in time for the

said September 1955 school term is not inconsistent with

the public interest or with the decision of the Supreme

Court;

4. That jurisdiction of this cause be retained for further

consideration and action from time to time, if the neces

sity shall occur, in respect to any issue pertinent to, or

arising from, the said injunction.

MOTION FOR FURTHER RELIEF

[R. pp. 47-53]

Plaintiffs move the Court to grant them further neces-

[16]

sary and proper relief and, in support thereof, state:

1. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court of the United

States rendered an opinion in this action and its companion

cases wherein it declared

“. . . that in the field of public education the doctrine

of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educa

tional facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we

hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated

for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason

of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal

protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment.”

2. On May 31, 1955, the Supreme Court of the United

States rendered another opinion in this action and its com

panion cases wherein it declared that

“All provisions of federal, state, or local law re

quiring or permitting such discrimination must yield

to this principle . . .

“. . . the viatlity of these constitutional principles

cannot be allowed to yield simply because of disagree

ment with them.

“While giving weight to these public and private

considerations, the courts will require that the defend

ants make a prompt and reasonable start toward full

compliance with our May 17, 1954, ruling. Once such

a start has been made, the courts may find that addi

tional time is necessary to carry out the ruling in an

effective manner. The burden rests upon the defend

ants to establish that such time is necessary in the

[17]

public interest and is consistent with good faith com

pliance at the earliest practicable date. To that end,

the courts may consider problems related to admini

stration, arising from the physical condition of the

school plant, the school transportation system, per

sonnel, revision of school districts and attendance areas

into compact units to achieve a system of determining

admission to the public schools on a nonracial basis,

and revision of local laws and regulations which may,

be necessary in solving the foregoing problems. They

will also consider the adequacy of any plans the de

fendants may propose to meet these problems and to

effectuate a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory

school system. During this period of transition, the

courts will retain jurisdiction of these cases.

“The judgments below, except that in the Delaware

case, are accordingly reversed and remanded to the

district courts to take such proceedings and enter such

orders and decrees consistent with this opinion as are

necessary and proper to admit to public schools on a

racially non-discriminatory basis with all deliberate

speed the parties to these cases.”

3. On July 18, 1955, this Court entered a decree in this

action which, among other things, adjudged, ordered, de

clared and decreed

“2. That insofar as they direct that white and

colored persons, solely on account of their race or color,

shall not be taught in the same schools, neither said

section 140, Constitution of Virginia of 1902, as

amended, nor said section 22-221, Code of Virginia

of 1950, as amended, shall be enforced by the defend-

[ 18]

ants, because the provisions of said section are in

violation of the clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States forbidding

any State to deny to any person within its jurisdic

tion the equal protection of the laws;

“3. That the defendants be, and they are hereby,

restrained and enjoined from refusing on account of

race or color to admit to any school under their super

vision any child qualified to enter such school, from and

after such time as the defendants may have made the

necessary arrangements for admission of children to

such school on a non-discriminatory basis with all de

liberate speed as required by the decision of the Su

preme Court in this cause; but the Court finds that

it would not be practicable, because of the adjustment

and rearrangement required for the purpose, to place

the Public School System of Prince Edward County,

Virginia, upon a nondiscriminatory basis before the

commencement of the regular school term in September

1955, as requested by the plaintiffs, and the Court is

of the opinion that the refusal of the Court to require

such adjustment and rearrangement to be made in time

for the said September 1955 school term is not incon

sistent with the public interest or with the decision

of the Supreme Court;

“A. That jurisdiction of this cause be retained for

further consideration and action from time to time,

if the necessity shall occur, in respect to any issue

pertinent to, or arising from the said injunction.”

4. Plaintiffs are informed and believe, and therefore al

lege on information and belief, that neither defendant

County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia,

L 19]

nor defendant T. J. Mcllwaine, Division Superintendent

of Schools of Prince Edward County, Virginia, has made

a reasonable start toward compliance with the decisions of

the Supreme Court of the United States or the injunction

of this Court, nor has either made or started making any

arrangements for the admission of plaintiffs to the public

secondary schools of Prince Edward County, Virginia, on

a racially nondiscriminatory basis.

5. Plaintiffs are informed and believe, and therefore al

lege on information and belief, that defendants County

School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, and T.

J. Mcllwaine, Division Superintendent of Schools of Prince

Edward County, Virginia, are awaiting formulation by

defendant Commonwealth of Virginia of policy and plans

to be pursued in the public schools of Virginia with refer

ence to the aforesaid decisions and do not propose to take

any action to effectuate a transition to a racially nondis

criminatory school system unless and until defendant Com

monwealth of Virginia formulates policy and plans there

for.

6. Plaintiffs are informed and believe, and therefore al

lege on information and belief, that defendant Common

wealth of Virginia has not made or started making any

arrangements for the admission of plaintiffs to the public

secondary schools of Prince Edward County, Virginia, on

a racially nondiscriminatory basis, and that it has not taken

any substantial action toward formulation of policy and

plans to be pursued in the public schools of Virginia with

reference to the decisions aforesaid except as follows:

(a) On or about November 11, 1955, the Virginia Com

mission on Public Education, a 32-member all-white legis

lative commission appointed by the Governor of Virginia

[ 2 0 ]

to examine the effect of the aforesaid decisions and to make

such recommendations as it deemed proper, submitted to

the Governor of Virginia its report, a copy of which is

attached hereto as Exhibit A. In this report the Commis

sion was highly critical of the decision of May 17, 1954, of

the "Supreme Court of the United States in this action

and its companion cases and stated:

“This Commission believes that separate facilities

in our public schools are in the best interest of both

races, educationally and otherwise, and that compul

sory integration should be resisted by all proper means

in our power.”

Among other things, the Commission recommended that

a special session of the General Assembly of Virginia be

called for the purpose of initiating a constitutional con

vention to amend Section 141 of the Constitution of

Virginia to permit the appropriation of public funds for

expenditure in furtherance of elementary, secondary, col

legiate and graduate education of Virginia students in

nonsectarian public and private schools and institutions of

learning in addition to those owned or exclusively controlled

by the state or some political subdivision thereof, and that,

upon such amendment being adopted, legislation be enacted

conferring a broad discretion on local school authorities

to make pupil assignments, and permitting tuition grants

from public funds to parents and guardians who might

object to having their children attend nonsegregated schools.

(b) On December 3, 1955, the General Assembly of

Virginia, in special session, enacted a bill, a copy of which

is attached hereto as Exhibit B, submitting to the qualified

electors of Virginia the question whether there should be

[ 21]

a convention to revise and amend Section 141 of the Con

stitution of Virginia.

(c) On January 9, 1956, the electors of Virginia voted

to have a convention to revise and amend Section 141 of

the Constitution of Virginia.

(d) On January 19, 1956, the General Assembly of Vir

ginia, in regular session, enacted a bill, a copy of which

is attached hereto as Exhibit C, providing for the election

of delegates to such constitutional convention, the issuance

of a writ for the same, the convening of such delegates, the

organization and functioning of such convention, and ap

propriating funds to defray the expenses of the same.

(e) On February 1, 1956, the General Assembly of Vir

ginia, in regular session, adopted a resolution, a copy of

which is attached hereto as Exhibit D, characterizing said

decision of May 17, 1954, “a deliberate, palpable, and dan

gerous attempt by the court itself to usurp the amendatory

power that lies solely with not fewer than three-fourths

of the States,” and asserting that a “question of contested

power” exists between the aforesaid decision and this

resolution, and appealing to other states of the United

States to join Virginia “in taking appropriate steps, pur

suant to Article V of the Constitution, by which an amend

ment, designed to settle the issue of contested power here

asserted, may be proposed to all the States,” and declaring

“that until the question here asserted by the State of Vir

ginia be settled by clear Constitutional amendment, we

pledge our firm intention to take all appropriate measures

honorably, legally and constitutionally available to us, to

resist this illegal encroachment upon our sovereign

powers, . . .”

[22]

(f) On March 7, 1956, in the aforesaid constitutional

convention ordained a revision and amendment of Section

141 of the Constitution of Virginia permitting the appro

priation of public funds for expenditure in furtherance of

elementary, secondary, collegiate and graduate education of

Virginia students public and nonsectarian private schools

and institutions of learning in addition to those owned or

exclusively controlled by the State or some political sub

division thereof, a copy of which ordinance is attached here

to as Exhibit E.

(g) On March 10, 1956, the General Assembly of Vir

ginia, in regular session, adopted a resolution, a copy of

which is attached hereto as Exhibit F, declaring that “it

is the public policy of Virginia that no athletic team of

any public free school should engage in any athletic contest

of any nature within the State of Virginia with another

team on which persons of the white and colored race are

members, nor should any such school schedule or permit

any member of its student body to engage in any athletic

contest within the State of Virginia with a person of the

white and colored race while such student is a member of

such student body.”

7. By their failure to effectuate a transition to a racially

nondiscriminatory school system, defendants continue, and

will continue, to deny plaintiffs, and other Negro children

of public school age similarly situated, the equal protection

of the laws secured by the Fourteenth Amendment of the

Constitution of the United States.

8. Plaintiffs are informed and believe, and therefore al

lege on information and belief, that no additional time

is necessary to carry out the rulings aforesaid in an effective

[ 23]

manner, or is necessary in the public interest, or is con

sistent with good faith compliance at the earliest practicable

date.

9. Plaintiffs are informed and believe, and therefore

allege on information and belief, that defendants continue

to operate the public schools of Prince Edward County,

Virginia, on the same racially separate basis that obtained

prior to the aforesaid decisions and will indefinitely continue

to do so unless specifically ordered (a) to make an im

mediate start toward desegregation and (b) to complete

this desegregation within a prescribed period of time.

Wherefore, plaintiffs respectfully pray that upon the

filing of this motion, as may appear proper and convenient

to the Court, this motion be advanced on the docket and

a speedy hearing hereof be ordered according to law, and

that upon such hearing

(a) This Court enter a decree ordering and directing

defendants, and each of them, their successors in office,

and their agents and employees, to make a prompt and

reasonable start toward compliance with the ruling of the

Supreme Court of the United States of May 17, 1954, and

permanently restraining and enjoining defendants, and each

of them, their successors in office, and their agents and

employees, from using race as a basis of determining ad

mission, assignment or attendance in any public secondary

school in Prince Edward County, Virginia, so that at a

time no later than the school term commencing in Septem

ber, 1956, plaintiffs, and all other Negro children of public

school age similarly situated, will be attending schools on

a basis not involving race, and ordering defendants, and

each of them, and their successors in office, to file with

this Court interim reports showing the plans and steps they

L24]

are making to change the existing method of determining

the public schools pupils attend so that as of September,

1956, race will no longer be used as a criterion for public

school attendance.

(b) That this Court allow plaintiffs their costs herein.

(c) That this Court retain jurisdiction of this cause for

further consideration and action from time to time, if the

necessity shall occur, in respect to any issue pertinent to,

or arising from, any injunction issued against defendants.

[Exhibits Omitted]

ANSWER TO MOTION FOR FURTHER RELIEF

[R. pp. 73-77]

The Defendants, in answer to the Motion for Further

Relief filed by the Plaintiffs herein, say:

1. The Defendants, County School Board of Prince

Edward County and T. J. Mcllwaine, admit that they are

awaiting the formulation by the Commonwealth of Vir

ginia of plans and policies to be followed in rearranging

its school laws in the light of the decisions of the Supreme

Court of the United States and assert that they are re

quired to do so under valid laws of the Commonwealth.

2. The Defendants assert that the Commonwealth has

made great strides toward the rearrangement of its school

laws. The details of the steps taken are outlined below:

(a) Promptly after the decision of this Court on July

18, 1955, it became apparent to the Governor that certain

[25]

provisions of Section 141 of the Constitution of Virginia

might inhibit certain legislation deemed desirable in con

nection with the solution of these problems. Accordingly,

a judicial interpretation of this section was required. Action

was promptly instituted in the Supreme Court of Appeals

of Virginia. On November 7, 1955, that Court decided

that the State could not pay money to private educational

institutions for tuition purposes. Almond v. Day, 197 Va.

419.

(b) Promptly after this decision, the Commission on

Public Education on November 11, 1955, presented its re

port to the Governor. A copy of this report is filed herewith

as Exhibit A. This report recommended that an amendment

of Section 141 of the Constitution of Virginia be proposed.

(c) On November 14, 1955, the Governor of Virginia

summoned the General Assembly of Virginia to meet in

special session on November 30, 1955, to consider the rec

ommendation of the Commission on Public Education.

(d) On November 30, 1955, the General Assembly met

in special session. It adopted an act, approved by the

Governor on December 3, 1955, authorizing an election to

determine whether a constitutional convention should be

called to consider the amendment of Section 141 of the

Constitution of Virginia.

(e) On January 9, 1956, the question so propounded

was presented to the voters. The State Board of Elections

certified to the Governor on January 16, 1956, that the

electorate had voted in favor of such constitutional con

vention by a vote of 304,154 in favor and 146,164 against.

(f) The General Assembly of Virginia met in regular

[ 2 6 ]

session on January 11, 1956. In obedience to the mandate

of the electorate, a bill was promptly introduced to provide

for the election of delegates to a constitutional convention

and its. meeting. This bill was enacted by the General As

sembly and approved by the Governor on January 19, 1956.

(g) Delegates to the Constitutional Convention were

elected by the people in their respective districts on February

21, 1956. This election was promptly canvassed.

(h) The Constitutional Convention met on March 5,

1956. After deliberation, it promulgated Section 141 of

the Constitution in amended form on March 7, 1956.

(i) The General Assembly adjourned at the conclusion

of its regular session of 60 days duration on March 10,

1956, 3 days after the promulgation of the Constitutional

amendment.

(j) Section 22-122 requires the Division Superintend

ent of Schools, with the advice of the School Board, to

present to the Board of Supervisors a budget for the en

suing school session on or before April 1 of each year.

This budget is a part of the general County budget which

must be acted on during the month of May. It is apparent,

therefore, that no action taken by the General Assembly

after the adjournment of the Constitutional Convention

could have been effective for the session 1956-57.

(k) The Governor of Virginia has stated publicly that

he proposes to call the General Assembly in special session

within 90 days after June 6, 1956, to consider and take

action on these problems. The statutes enacted at this ses

sion will be effective for the session 1957-58.

[ 2 7 ]

3. Accordingly, the Defendants assert that the Common

wealth has taken every reasonable step to proceed as

rapidly as possible toward a reasonable solution of the prob

lems raised by the decisions in this case.

4. The Defendants assert that any requirement by this

Court that the high schools be no longer operated for the

session 1956-57 on the basis on which they have been op

erated in the past would result in the closing of such schools,

increased racial tension and possible violence, to the lasting

detriment of the citizens of Prince Edward County, whether

they be children or adults, white or Negro. In support

of this allegation, the Defendants present the affidavits of

the persons listed below filed herewith as exhibits lettered

as indicated opposite their names below:

Name of Affiant Exhibit Letter

Lester E. Andrews A

B. Calvin Bass B

James T. Clark C

Carter 0 . Lowance D

Thomas J. Mcllwaine E

Vernon C. Womack F

THE DEFENDANTS, therefore, request that the

Motion for Further Relief filed by the Plaintiffs be denied.

[Exhibits Omitted]

[ 2 8 ]

SUPPLEMENTAL ANSWER AND MOTION TO

DISMISS MOTION FOR FURTHER RELIEF

[R. pp. 100-101]

The Defendants respectfully move the Court to dismiss

the Motion for Further Relief filed by the Plaintiffs herein

on the following grounds:

L On September 29, 1956, the Governor of Virginia

approved Chapter 70 of the Acts of Assembly of Virginia

for the Extra Session of 1956. This act, to become effective

on December 28, 1956, provides a comprehensive program

for the assignment of students to various schools, including

provisions for administrative appeals with judicial review.

A copy of this act appears on page 47 of the pamphlet

attached hereto as Exhibit A, the pamphlet containing all

of the statutes relating to the public schools enacted at such

Extra Session. This act will be in effect before the opening

of the next term of the public schools of Prince Edward

County. The act provides effective administrative proce

dures for the plaintiffs by which they can obtain the relief

that they seek in this case to the extent that they are entitled

to relief. The plaintiffs should not be permitted to seek

relief now in this court until all administrative remedies

provided by the act have been exhausted.

2. The order entered herein on July 18, 1955, was a

final order and adequate remedies are available to the plain

tiffs for the enforcement of that order. Accordingly, further

relief in the form of an amendment of or supplement to

that order should not be awarded to the plaintiffs.

[Exhibit Omitted]

[ 29]

OPINION

[R. pp. 104-136]

This case originated in the Richmond Division upon the

filing of a complaint on May 21, 1951. The declared object

of the complaint was, in substance, to obtain a declaratory

judgment holding that segregation of pupils in the public

schools in the county by races constituted discrimination

in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States. There were also allegations

concerning the inequality of school facilities, which last

constituted a somewhat unimportant part of the contro

versy.

The case was heard February 25-29, 1952, by a three-

judge court, which had been convened in accordance with

the provisions of the statute. The opinion of that Court

was filed on March 7, 1952, and is reported in 103 Fed.

Supp. 337. An appeal was allowed on May 5, 1952, and

on May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court handed down its

opinion, reversing the findings and conclusions of this

Court, the case having been consolidated with four other

cases then pending before it. See Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 347 U S ., 483. At the suggestion of the Court the

case was further argued as to specific questions hereafter

more fully discussed, and the Court filed its second opinion

on May 31, 1955. 349 US., 294. The mandate having

been received by this Court on June 28, 1955, the case was

called for further proceedings and on July 18, 1955, the

three-judge court entered an order directing compliance

with the terms of the mandate, but finding that it was

not practicable to effect a change in the operation of the

public schools of the county during the session beginning

September 1955.

[ 3 0 ]

On April 23, 1956, plaintiffs filed a motion seeking an

order fixing a time limit within which compliance with

the order should be had, to which answer of the defendants

was filed on June 29, 1956. On July 9, 1956, the three-

judge court was reconvened and, pursuant to order pre

viously entered, heard argument on the sole question of

whether it should continue to function or if the case should

be returned to the resident District Judge in whose division

suit was instituted. On July 19, 1956, the Court announced

its unanimous decision that since the constitutional question

involved had been determined, the three-judge court should

no longer function and the matter should be heard by the

resident District Judge. On October 17, 1956, defendants

filed a motion seeking the dismissal of the case upon the

ground that the General Assembly of Virginia in extra

session 1956 had provided the plaintiffs an adequate remedy

at law in the courts of the Commonwealth.

The respective motions were argued on November 14,

1956, and the case is now before me as the resident Dis

trict Judge for disposition of the motions upon the plead-

ings and certain exhibits which have been filed pertaining

to the motions.

I am mindful that other District Courts have dealt with

similar cases but in each case the Court was dealing with

the record before it and with the problems of the partic

ular locality affected by its order. Consequently, those de

cisions afford little, if any, aid in dealing with this case.

The questions raised by the supplemental answer and

motion to dismiss the motion for further relief filed by the

defendants on October 17, 1956, and the arguments there-

[3 1]

on, may be stated as follows:

(a) Should the three-judge District Court be re

convened ?

(b) Are certain statutes passed by the General As

sembly of Virginia in extra session 1956 constitu

tional ?; and

(c) Should plaintiffs be required to exhaust ad

ministrative remedies provided by the state statutes?

I shall first consider the questions presented in the last

mentioned motion in the order stated.

From an examination of the applicable statute (Title

28, Section 2281, United States Code), and upon consid

eration of its purpose I reach the conclusion that in the

present state of the record in this case it is not appro

priate to request the convening of a three-judge court. There

is no application before me for an order to restrain or

enjoin the action of any officer of the state in the enforce

ment or execution of any state statute or order such as

contemplated by the Act of Congress.

In the present state of the record of this particular case

I do not consider the constitutionality of the state statutes

referred to or the relief there provided proper subjects of

inquiry. They were the subject of argument at the hearing

on November 14, 1956, and I shall dispose of the questions

so raised without extended discussion.

The situation before me was aptly summed up by Judge

Parker in Carson v. Warlick, decided November 14, 1956,

in which he used the following language:

[ 3 2 ]

“It is argued that the Pupil Enrollment Act is un

constitutional; but we can not hold that that statute

is unconstitutional upon its face and the question as

to whether it has been unconstitutionally applied is not

before us, as the administrative remedy which it pro

vides has not been invoked.”

And further:

“It is to be presumed that these (the officials of

the schools and the school boards) will obey the law,

observe the standard prescribed by the legislature, and

avoid the discrimination on account of race which the

Constitution forbids. Not until they have been applied

to and have failed to give relief should the courts be

asked to interfere in school administration. As said

by the Supreme Court in Brown, et al v. Board of

Education, et al, 349 U.S., 294, 299:

“ ‘School authorities have the primary responsibility

for elucidating, assessing and solving these problems ;

courts will have to consider whether the action of

school authorities constitutes good faith implementa

tion of the governing constitutional principles.’ ”

The opinion in The School Board of the City of Charlottes

ville, et al v. Doris Mane Allen, et al, and County School

Board of Arlington County, Virginia, et al v. Clarissa S.

Thompson, et al (4th Cir.) decided December 31, 1956,

contains language pertinent here. The Court again speaking

through Chief Judge Parker, in referring to administrative

remedies provided under Section 22-27 of the Code of Vir

ginia, and after pointing out that the pupil placement law

recently enacted by the General Assembly of Virginia had

not become effective when the cases were heard (although

[ 33 ]

it was effective at the time that opinion was rendered, as

is the situation here) said:

“* * *. Reliance is placed upon our decision in

Carson v. Warlick, 4 Cir. F. 2d. . In that

case, however, an adequate administrative remedy had

been prescribed by statute, the plaintiffs there had failed

to pursue the remedy as outlined in the decision of

the Supreme Court of the State and there was nothing

upon which a court could say that if they had followed

such remedy their rights under the Constitution would

have been denied them.'” (Emphasis supplied)

See also Hood v. Board of Trustees, etc., 232 Fed. (2d),

626 (4th Cir.), and Robinson v. Board of Education, etc.,

143 Fed. Supp., 4 8I (District of Maryland).

The quoted language appears in point in so far as the

constitutional question is concerned. While the statutes in

volved are not identical, the principle announced is appli

cable.

Turning to the proposal that the plaintiffs be required to

exhaust the administrative remedies provided by the state

statutes, I am again confronted by the record before me.

Being of opinion I am not in a position to pass upon the

constitutionality of the statutes setting up the administra

tive remedy, it is my thought that I should not undertake

to require the plaintiffs to seek any particular remedy.

They are free to do so and thereby test the constitutionality

of the statutes should they desire. However, that is a right,

not an obligation. In the meantime, this is a matter of

school administration in which I should not interfere.

[ 3 4 ]

It follows that the motion of the defendants, to dismiss

the motion for further relief should not be granted at this

time. However, I incline to the view that instead of being

dismissed it should be retained on the docket of the Court

for final disposition at a later time should further pro

ceedings develop an issue properly determinable in this case.

In undertaking to approach a solution to the trouble

some problems involved in this case which are presented

by the record and properly before me for determination,

including the motion for further relief filed by the plain

tiffs, it is to be borne in mind that the Supreme Court has

decided only one legal principle which is concisely stated

in the syllabus appearing in 347 U S., 483, as follows:

“Segregation of white and Negro children in the

public schools of a state solely on the basis of race,

pursuant to state laws permitting or requiring such

segregation, denies to negro children the equal pro

tection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment * *

A study of the opinions of May 17, 1954, and May 31,

1955, reveals no other principle of law to serve as precedent

or landmark in undertaking to apply the law to the facts,

although certain well-recognized equitable principles are

mentioned. For a clearer understanding of the question here

presented, some discussion of those opinions at this point

may be helpful.

In the 1954 opinion, which will be referred to as the

First Brown Case, at page 495, the Court, after stating

that “because of the wide applicability of this decision, and

because of the great variety of local conditions, the formu-

[ 35]

lation of decrees in these cases presents problems of con

siderable complexity”, requested counsel to present further

argument on questions which may be briefly summarized

as follows: Whether a decree would necessarily follow pro

viding that negro- children should forthwith be admitted

to schools of their choice, or whether the Court should

permit an effective gradual adjustment to be brought about

to a system not based on color distinctions; whether the

Supreme Court should formulate detailed decrees in the

cases; if so, what specific issues should be reached there

by ; if the appointment of a special master to hear evidence

with a view of recommending specific terms for the decrees

would be desirable; and finally, whether that Court should

remand the cases to the courts of first instance with direc

tions to frame decrees, and if that policy were followed,

what general directions should the decrees of the Supreme

Court include and what procedures should the courts of

first instance follow in arriving at the specific terms of

more detailed decrees. For full text of the questions pro

pounded and argued see 345 U.S., 972.

Following elaborate argument upon these questions, in

which the Attorneys General of the affected states and the

Solicitor General of the United States presented their views,

the Court filed its opinion on May 31, 1955, which will

be referred to as the Second Brown Case. With knowledge

of what was considered by the Court, as revealed by the

questions, the language of the opinion in the Second Brown

Case takes on added significance, both with respect to what

was not said as well as to what was said. Certain portions

of that opinion follow:

“Full implementation of these constitutional prin

ciples may require solution of varied local school

[ 3 6 ]

problems. School authorities have the primary re

sponsibility for elucidating, assessing, and solving these

problems; courts will have to consider whether the

action of school authorities constitutes good faith im

plementation of the governing constitutional principles.

Because of their proximity to local conditions and the

possible need for further hearings, the courts which

originally heard these cases can best perform this

judicial appraisal. Accordingly, we believe it appro

priate to remand the cases to those courts.”

The Court then proceeded to announce the following

principles which should receive attention of the District

Courts:

“In fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the

courts will be guided by equitable principles. Tradi

tionally, equity has been characterized by a practical

flexibility in shaping its remedies and by a facility

for adjusting and reconciling public and private needs.

These cases call for the exercise of these traditional

attributes of equity power. At stake is the personal

interest of the plaintiffs in admission to public schools

as soon as practicable on a nondiscriminatory basis.

To effectuate this interest may call for elimination of

a variety of obstacles in making the transition to school

systems operated in accordance with the constitutional

principles set forth in our May 17, 1954, decision.

Courts of equity may properly take into account the

public interest in the elimination of such obstacles in

a systematic and effective manner. But it should go

without saying that the vitality of these constitutional

[37]

principles cannot be allowed to yield simply because

of disagreement with them.”

From the foregoing it is clear that the law must be

enforced but the Court is acutely conscious of the variety

of problems of a local nature constituting factors to be

considered in the enforcement. Further emphasis upon this

point is found on page 298, where the Court said:

“Because these cases arose under different local con

ditions and their disposition will involve a variety of

local problems, we requested further argument on the

question of relief.”

Bearing in mind that the only legal issue in this case

pertains to a right guaranteed by the Constitution, this

language coupled with the action of the Court, takes on

significance which can hardly be over emphasized. It is

elementary law that one deprived of a right guaranteed by

the Constitution ordinarily is afforded immediate relief.

Notwithstanding this fundamental principle, the Supreme

Court in this case has seen fit to specifically declare that

while the plaintiffs are entitled to the exercise of a con

stitutional right, in view of the grave and perplexing prob

lems involved, the exercise of that right must be deferred.

With that declaration the Court used equally forceful lan

guage indicating that it realizes that conditions vary in

different localities. Consequently, instead of simply declar

ing the right and entering a mandate accordingly, it has

seen fit in the exercise of its equity powers to not only

defer until a later date the time when the right may be

exercised, but to clearly indicate that the time of exercising

such right may vary with conditions. A realization of the

effect of this action on the part of the Court is of supreme

importance to an understanding of the course to be pursued

by the Courts of first instance. At the risk of being rep

etitious, I again recall that: Before laying down those

principles, the Court considered and rejected the suggestion

that negro children should be forthwith admitted to schools

of their choice; rejected the suggestion that it formulate

detailed decrees; rejected the suggestion that a special

master be appointed by it to hear evidence with a view

to recommending specific terms for such decrees and

adopted the proposal that the Court in the exercise of

equity powers direct an effective gradual adjustment under

the order of the Courts of first instance. Further, the Court

considered and rejected the suggestion that a specified rule

of procedure be established for the District Courts but placed

upon those Courts the responsibility of considering, weigh

ing and being guided by conditions found to prevail in

each of the several communities to be affected by their

decrees.

In the absence of precedent, in undertaking* to follow

the mandate of the Supreme Court, the District Courts

are confronted with the necessity of following an uncharted

course in applying the sole legal principle announced in

the First Brown Case. One idea which emerges clearly is

that procedural rules adopted in one locality may be al

together inapplicable to conditions in another.

Boiled down to its essence, in the Second Brown Case

the Court after pointing out that the local school author

ities have the primary responsibility of finding a solution

to the varied local problems, proceeded to observe that the

District Courts are to consider whether the actions of the

local authorities are in good faith; and that by reason of

1 3 9]

their proximity to local conditions those Courts can best

appraise the conduct of the local authorities. It is then

pointed out that in so appraising, the Courts should be

guided by the traditionally flexible principles of equity for

adjusting and reconciling public and private needs. To be

considered is the personal interest of the plaintiffs, as well

as the public interest in the elimination of obstacles in a

systematic and effective manner. During this period the

Courts should retain jurisdiction of the cases. The Court

has here clearly and in unmistakable terms placed upon

the District Judges the responsibility of weighing the

various factors which prevail in the respective localities

affected. There is here a recognition of the obvious fact

that in one locality in which conditions permit, a change

may be effected almost immediately. In other localities a

specified period appropriate in each case may be feasible

and a definite time limit fixed accordingly. In yet other

communities a greater time for compliance may be found

necessary. It is clear that the Court anticipated the appli

cation of a test of expediency in such cases so that an

orderly change may be accomplished without causing a

sudden disruption of the way of life of the multitude of

people affected.

While the Supreme Court made no reference to yet an

other interest, there is one of a semi-public nature. This

involves the teachers of the county, both white and colored,

and their families, dependent upon them for support.

The conflicting rights and interests of racial and national

groups in this country is nothing new. It is not confined to

the negro race but numerous illustrations might be used.

A striking illustration is found in the situation of persons

of Oriental origin who have come to this country. It is

[ 4 0 ]

worthy of passing note to recall that the opinion appearing

in the official reports immediately preceding the First Brown

Case involves the rights of persons of Mexican descent.

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S., 475. It must be borne in

mind that these conflicts and the cases arising therefrom

are the result of customs, traditions, manners and emotions

which have existed for generations. In this particular case

the customs to be changed have been not only generally

accepted but repeatedly and expressly declared the law of

the land since 1896.1 While lawyers may have been con

scious of the evolution of the law during this period and

prepared to anticipate the possibility of a change, the

average layman affected may not be charged with such

prescience. Patience, time and a sympathetic approach are

imperative to accomplish a change of conditions in an

orderly and peaceful manner and with a minimum of fric

tion.

In seeking a solution it is necessary to know and to

understand the background upon which the factual situation

is cast. In this connection it is necessary to examine briefly

the present conditions in Prince Edward County, Virginia,

historically and as revealed by the record in this case.2

Prince Edward County being inland from the easily navi

gable tidal reaches of the streams watering that region,

was not settled until the first half of the 18th century,

after the power of the Indians had been broken. At that

time the pattern of life in the Colony had become established

and the early residents carried with them the manners and

1 Plessy V. Ferguson, 163 U.S., S37; Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S., 78

2 See “History of Prince Edward County, Virginia”—H erbert Clarence

Bradshaw—1955

[ 4 1 ]

customs prevailing in the more populous regions of Vir

ginia. By 1783 the population consisted of 1,552 white and

1,468 colored residents. The 1950 census showed a popu

lation of 15,396, with the white and colored races approxi

mately equal in number. During the intervening years the

relations between the races have been harmonious, with

a minimum of friction and tension as compared with some

regions. During several decades prior to the War Between

the States the processes of orderly and gradual adjustment

which were becoming increasingly evident were interrupted

by being involved in the political issues confronting the

growing nation, with particular reference to regional dif

ferences and the clash of economic rivalries of various

sections. Unfortunately this resulted in accentuating racial

tension and hostility which became somewhat acute at times.

While these conditions were common to the southeastern

and southern parts of the country, it was felt less in Prince

Edward and the surrounding area than in many other sec

tions.

In the days following 1861-65 the entire section was

poverty stricken. For the rank and file of both races there

was a struggle for existence and education was of secondary

importance. It is true that in this situation with the local

government controlled by members of the white race and

with severely limited means, there was inequality in the

division, but members of the negro race were not excluded

from sharing, although to a lesser extent. This was due

in part to an understandable, if erroneous, feeling that those

upon whom the greater tax burden fell should receive the

greater benefit. During the second quarter of the present

century the economy of the section most seriously concerned

has shown a marked improvement. Due to that improve-

[ 42]

ment, corresponding advantages have resulted in housing,

education and knowledge on the part of both races. Marked

improvement in racial relationship resulted although many

firmly fixed ancient customs and manners remain. With

an improvement in the economic condition of the county

and the resulting- increase in available financial resources,

an awareness of public sentiment, the mandatory require

ments of the Virginia constitution and statutes upon the

subject, coupled with suits brought in Federal Courts in

other localities, the responsible authorities of Prince Ed

ward County made plans for the erection of new school

buildings exclusively for negroes, which are now concededly

equal if not superior to those occupied by the white pupils.

Before these plans could be completed, this suit was filed.

Since the decision in the Brown case these plans have been

completed. The defendants, who are the Superintendent and

members of the School Board, and aŝ such charged with

the “primary responsibility for elucidating, assessing and

solving” their problems, have proceeded with the operation

of the schools in the county in accordance with the practice

which has prevailed. They have prepared and submitted

to the Board of Supervisors of the county annual budgets

for the operation of the schools. In this connection it is

to be borne in mind that the defendants have no authority

under the law to levy or assess taxes nor to raise funds

except in a limited manner by borrowing under certain con

ditions not pertinent here. Responsibility for providing local

funds for the operation of schools rests upon the Board of

Supervisors who are not defendants before this Court. The

School Board consists of members appointed by the school

trustee electoral board, the members of which in turn are

appointed by the local state court. The members of the

Board of Supervisors are elected by the people. Buttressed

by popular demand of the people of the county since the

decision in the First Brown Case, evidence in part by

a petition signed by more than 4,000 residents, the Board

of Supervisors has declined to allocate funds for the opera

tion of schools on an annual basis. Instead it appropriates

the necessary operating expenses on a monthly basis, with

a publically declared intention of discontinuing such ap

propriation if schools in the county are mixed racially at

this time. In this connection attention is invited to the

statutes recently enacted by the Virginia General Assem

bly under which the funds provided by the state may be

withheld. Pending final interpretation of those statutes time

valuable in the educational opportunities of the children in

volved might be irretrievably lost. Affidavits filed in this

case and in no way controverted or mentioned, by counsel

for the plaintiffs, declare racial relations in the county to

be more strained than at any time during the present gen

eration.

In this state- of facts I am called upon to fix a time

when the defendants should be required to comply with

the terms of the injunction issued by the three-judge court

in obedience to the mandate of the Supreme Court. To

do this I am to “adjust and reconcile public and private

needs”, by weighing and considering the personal interests

of the plaintiffs as well as the interest of the public, in

the elimination of obstacles in order that there may be

a systematic, orderly and effective transition of the school

system in accordance with the constitutional principles

announced in the Brown case.

I believe the problems to be capable of solution but they

will require patience, time and a sympathetic understanding.

[44]

They can not be solved by zealous advocates, by an

emotional approach, nor by those with selfish interests to

advance. The law has been announced by the Supreme Court

and must be observed but the solution must be discovered

by those affected under the guidance of sensible leader

ship. These facts should be self evident to all responsible

people.

The children of both races, constituting an entire genera

tion of this county, are the persons to be affected by what

ever action may be taken and it follows that theirs is the

real interest at stake, although closely connected with that

of their parents and guardians.

Should the public schools of the county be closed for

any reason, approximately three thousand children, includ

ing those of an age at which they are peculiarly impression

able, will be released from attendance. An interrupted

education of one year or even six months at that age places

a serious handicap upon the child which the average one

may not overcome. Among those of the older group there

are some for whom it will mean the end of an education.

Should the schools be resumed after an interruption, those

among the younger group will be retarded in acquiring

an education as compared with their contemporaries in other

communities. With the release from discipline brought about

by compulsory attendance at school, problems concerning

juvenile conduct will be intensified with resulting injury

to both children and the community and a resulting in

crease of racial tension with members of each race blaming

the other for the lack of schools. In this connection it is

to be remembered that the police protection of rural com

munities is different from that afforded in more populous

areas. The salaries paid teachers in the state are not such

[ 45 ]

as to enable them to accumulate a fund sufficient to support

themselves and their families over a protracted period of

unemployment. Loss of employment would be a serious con

sequence to many teachers of both races who are established

in the community. Tentative and substantial plans have

been made for continuation by private means of the edu

cation of white children of the county. There is no such

provision for negro children. These considerations all in

volve the public and private interests of the community as

distinguished from the quandary of the members of the

School Board.

The admonition of the Supreme Court that the personal

interests of the plaintiffs in admission to public schools

as soon as practicable on a nondiscriminatory basis is a

consideration of which I am mindful. In response to a ques

tion from the bench, counsel for the plaintiffs stated that

so far as he knew none of the original plaintiffs are now

attending the schools. However, additional named plaintiffs

have intervened and it is to be recalled that this is a class

action. Should the plaintiffs be deprived of education or

suffer an interruption in their education they will be handi

capped. Concededly, their opportunities in so far as physical

equipment and curriculum are concerned, are equal if not

superior to those available to children of the white race.

It has been held by the Court that segregation of white

and colored children in public schools has a detrimental

psychological effect upon the colored children. That is pri