Tucker v. Tobacco Workers International Union, AFL-CIO, CLC, Local 183 Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Tucker v. Tobacco Workers International Union, AFL-CIO, CLC, Local 183 Brief for Appellants, 1973. b1d3f1fc-c69a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b346efc7-2d3d-4049-a9f9-824b7a6d95f7/tucker-v-tobacco-workers-international-union-afl-cio-clc-local-183-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I

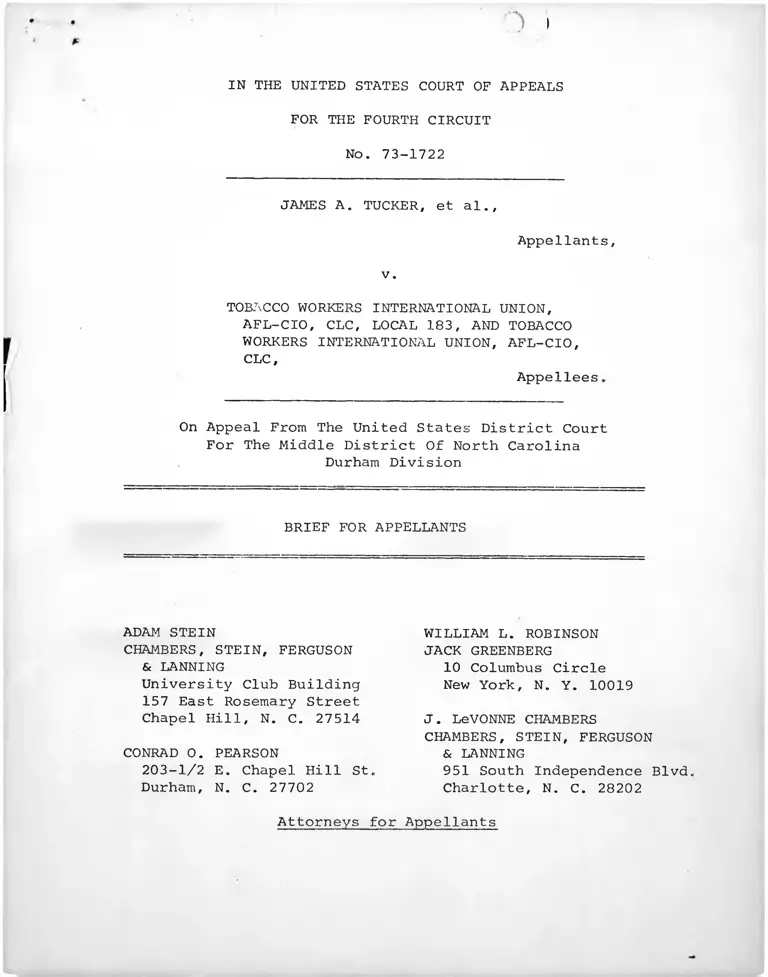

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 73-1722

JAMES A. TUCKER, et al..

Appellants,

V.

TOBJvCCO WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UNION,

AFL-CIO, CLC, LOCAL 183, AND TOBACCO

WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UNION, AFL-CIO,

CLC,

Appellees

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Middle District Of North Carolina

Durham Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

ADAM STEIN

CHAMBERS, STEIN, FERGUSON

& BANNING

University Club Building

157 East Rosemary Street

Chapel Hill, N. C. 27514

CONRAD 0. PEARSON

203-1/2 E. Chapel Hill St,

Durham, N. C. 27702

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

JACK GREENBERG

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS

CHAMBERS, STEIN, FERGUSON

& BANNING

951 South Independence Blvd.

Charlotte, N. C. 28202

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Question Presented ................................

Statement Of The Case .............................

Statement of Facts ................................

ARGUMENT:

I. Title VII Of The Civil Rights Act Of 1964

And Section 1 Of The Civil Rights Act Of

1866 Each Confer Federal jurisdiction For An

Action Challenging Racial Discrimination

In Election Practices Of Merged Black And

White Local Unions ........................ .

A. The Gravamen Of Plaintiffs' Complaint,

Racial Discrimination Manifest In An Adverse

candidate Eligibility Ruling, Was Ignored By

The District Judge ......................

B. Racial Discrimination Manifested In

Union Election Practices Is Prohibited

By Section 703(c) Of The Civil Rights Act

Of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(c) .........

II.

C. The Racial Discrimination Alleged In

This Case States a Cause of Action Under

Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866,

42 U.S.C. § 1981 .............. ..........

The District Court Erred In Dismissing This

Case In Which Facts Were Alleged And Admitted

Constituting A Prima Facie Violation Of The

Civil Rights Acts Of 1866 and 1964 On The

Ground That Title IV Of The Labor Relations

And Disclosure Act of 1959 Imposes an Exclu

sive Remedy For Challenging Union Elections,.

A. The Language and Legislative History

of the LMRDA Demonstrate That Congress

Did Not Intend That The Act Deal with the

Evil of Racial Discrimination in Union

Activities...............................

1

2

5

10

10

15

21

25

26

PAGE

B. Judicial Decisions Applying Title

IV of the LMRDA Have Not Precluded

Private Actions Challenging Racially

Discriminatory Union Election Practices ... 31

C. The Decision Below Stands Alone Holding

That A Non-Title VII Remedy for Racial

Discrimination is Exclusive Rather Than

Alternative .............................. 36

Conclusion .......................................... 47

Appendix ........................................... 49

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Page

Bales V. Union Camp Corp., 5 EPD § 8052

(S.D. Ga. 1972).................................... 40

Bowe V. Colgate Palmolive Co., 415 F.2d

711 (7th Cir. 1969)................................ 42

Boys Markets Inc. v. Retail Clerks Union,

398 U.S. 235 (1970)................................ 43

Broadnax v. Burlington Industries Incorporated,

C.A. No. C-160-G-71 (M.D. N.C. 1971)................ 22

Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers v.

Louisville & N.R. Co., 373 U.S. 33 (1963).......... 37 I

Brotherhood of Trainmen v. Howard, 343 U.S.768 (1952) 37

Brown V. Gaston City Dyeing Machine Co., 467

F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972).......................... 22, 46

Calhoun v. Harvey, 379 U.S. 134 ( 1 9 6 4 ) .............. 31, 45

Chicago Fed. of Musicians, Local 10 v.

American Fed. of Musicians, 2 EPD § 10, 212

(N.D. 111. 1964) 17

Choates v. Caterpillar Truck Co., 402 F.2d 357 !

(7th Cir. 1968) 21 '

Dewey v. Reynolds Metals Co., 429 F.2d 324 (6th Cir.

1970)............................................... 42, 43

Dobbins v. Local 212, 1 BEW, 292 F. Supp. 413 i

(S.D. Ohio 1968) 23 i’

i

English v. Seaboard Coast Line RR Co., 4 EPD

§ 7645 (S.D. Ga. 1972) ............................ I7

Dent V. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co., 406 F.2d

399 (5th Cir. 1969) ............................... 21

Garner v. Teamsters Union, 346 U. S. 485 (1953) . . . . 40

Glover v. St. Louis-San Francisco R.R. Co., 393

U.S. 324 (1969) . . ............................ 31

Griffin v. Pacific Mari .me Ass'n, 5 EPD § 8598,

No. 72-2117 (9';h Cir. Apr. 25, 1973) .............. 42, 43

X X X

Pa^e

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ........

Hicks V. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 310 F. Supp. 536

(E.D. La. 1970) ..................................

Howard v. St. Louis-San Francisco R. Co., 361F.2d 905 (8th Cir. 1966), cert, denied, 385 U.S.

986 (1966) ........................................

Hutchins v. U.S. Industries, 428 F.2d 303

(5th Cir. 1970) ....................................

International Association of Machinists v.

Gonzales, 356 U.S. 617 (1958) ......................

Jamison v. Olga Coal Co., 335 F. Supp. 454

(S-D. W. Va. 1971) ................................

Johnson v. Seaboard Airline RR Co., 405 F.2d

645 (4th Cir. 1968) ................................

Jones V. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) . . .

King v. Georgia Power Co., 295 F. Supp. 943

(N.D. Ga. 1968) ....................................

Local 12, United Rubber Works v. NLRB, 368

F.2d 12 (5th Cir. 1966) ............................

Local 53, International Ass'n of Heat and Frost

I and A. Wkrs v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th

Cir. 1969) ........................................

Long V. Georgia Kraft Co., 445 F.2d 331 (5th

Cir. 1972) .........................................

Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc., 5 EPD

§ 8605 (D.C. Cir. 1973) ............................

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, ___ U.S. ___,

L.Ed.2d 668 (1973) ................................

NLRB V. Tanner Motor Livery, Ltd., 349 F.2d

(9th Cir. 1965) ..................................

Newman v. Avco, 451 F.2d 742 (6th Cir. 1971) ........

Norman v. Missouri Pacific RR Co., 414 F.2d

73 (8th Cir. 1969) . . .............................

Oubichon v. North America,Rockwell corp., ___ F.2d ___^

No. 71-1540 (9th Cir. July 10, 1973) ..............

iv ^

34

17

37

42

23

22

I

I

2 1 , 2 2 , 52

43 ,

40

i

18 1

I

17

42 t1/

2 0 , 2 1 , 41

41

43

1 1 , 3 7 , 38 ,

44

42

Page

Parks V. International Brotherhood of ElectricalWorkers, 314 F.2d 886 (4th Cir. 1963), cert, denied,

372 U.S. 976 (1963).................................... 23

Peters v. Missouri-Pacific RR Co., ___ F.2d ___, 5

EPD § 8550 (5th Cir. 1973) 39

Quarles v. Phillips, 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D.

Va. 1968)............................................ 12

Rios V. Reynolds Metals Co., 467 F.2d 54 (5th

Cir. 1972) ........................................... 42

Robinson v. Lorillard, 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir.

1971) 12, 13, 35,

40, 44

Rock V. Norfolk and western Ry Co., C.A. No. 258-

69-N (E.D. Va. 1972), aff'd, 473 F.2d 1344 (4th

Cir. 1973), cert, denied, ___ U.S. ___ (1973)........ 17, 39

Rosenfield v. Southern Pacific, 293 F. Supp. 1219

(C.D. Cal. 1968), aff'd, 444 F.2d 1219 (9th Cir.

1971) .................................................43

Russell V. American Tobacco Co., No. C-2-G-68,

M.D. N.C. Greensboro Div., 5 EPD § 8447,

(M.D. N.C. 1973)...................................... 12, 13

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097

(5th Cir. 1970) 22, 46

Saunders v. Shoemann, 80 LRRM 2903 (Ohio Ct. App. 1972) . 33

Scott V. Young, 421 F.2d 143 (4th Cir. 1970)............ 22

Shultz V. Local 1291, International Longshoremen,

338 F. Supp. 1204 (E.D. Pa. 1972), aff'd 461

F.2d 1262 (3rd Cir. 1972) .......................... 19, 20, 32,

33, 34, 36

Spann v. Kay Wood, 446 F.2d 120 (6th Cir. 1971) . . . . 43

Steele v. Louisville & N.R. Co., 323 U.S. 192

(1944) 37, 40

Taylor v. Armco Steel corp., 429 F.2d 498

(5th Cir. 1970) ..................................... 41

Tippett V. Liggett & Myers Tobacco Company, 316

F. Supp. 292 (M.D. N.C. 1 9 7 0 ) ...................... 40

V

Page

Trbovitch v. United Mine Workers, 404 U.S- 528

(1972) .......................................... .

United States v. Chesapeake and Ohio Ry Co., 4

EPD § 7637 (E.D. Va. 1971), vacated in part and

remanded, 471 F.2d 582 (4th Cir. 1972) ............

United States v. International Longshoremen, 460F.2d 497 (4th Cir. 1972) ..........................

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451

F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971) ..........................

United States v. Local 86, International Ass'n of

Bridge, S.O. and R. Ironworkers, 316 F. Supp. 202

(W.D. Wash. 1970), affd 443 F.2d 544 (9th Cir.

1971) . ..........................................

United States v. Sheet Metal Wkrs Ass'n,

Local 36 (8th Cir. 1969) ........................

Vaca V. Sipes, 386 U.S. 171 (1967) ................

Voutsis V. Union Carbide Corp., 452 F.2d 889 (2nd Cir.

1971) ............................................

Washington v. Baugh Construction Co., 313 F. Supp.

598 (W.D. Wash. 1969) ............................

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel works, 427 F.2d 476 (7th

Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 911 (1970) . . .

Western Addition Community Organization v. NLRB ___

F.2d ___, No. 71-1656 (D.C. Cir., June 29, 1973) . .

Whitfield V. United Steelworkers of America, 263

F.2d 546 (5th Cir. 1959), cert, denied 360 U.S.

902 (1959)........................ ................

Wirtz V. Hotel Employees Union, 391 U.S. 492 (1968)

Wirtz V. Local 153, G.B.B.A., 389 U.S. 463 (1968) . .

31, 32

16, 39

18

38, 39

19 I

19

40

42

23

23, 146i

24, 41

i

41

31

26, 27, 28,

31, 45

Young v. International Telephone and Telegraph

Co., 438 F.2d 757 (3rd Cir. 1971) ........ 22, 46

VI

Statutes

Page

Civil Rights Act of 1866, Section 1, 42 U.S.C. §§1981,

1982 ................................................. 1-4, 21, 22,

51-52

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII, 42 U.S.C. §§

2000e, 2000e-2(c), 2000e-2(d), 20003-4 .............. 1-4, 15-16,

18-19, 30, 32-

33, 46,50

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, 42

U.S.C. § 2 0 0 0 e ..................................... 49-50

Labor Management Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. 1 4 1 ........ 52

Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of

1959, 29 U.S.C. §§401, 411, 481-483, 523 ........ 1-4, 10, 19-20,

25-27, 29, 31,

33

National Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. §§151,

157, 185 ........................................... 23, 39, 40-41,

46, 52

Railway Labor Act, 45 U.S.C. § 151 .................. 37-38, 46, 52

Other Authorities

Aaron, The Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure

Act of 1959, 73 Harv. L.Rev. 851 ( 1 9 6 0 ) .......... 29

110 Cong. Rec. 13650 ( 1 9 6 9 ) ................ .. 46

Cox, Internal Affairs of Labor Unions under the

Labor Reform Act of 1959, 58 Mich. L.Rev.

819 (1960) ......................................... 28

EEOC, Legislative History of Title VII and XI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 (1964).................... 15

Griffin, The Landrum-Griffin Act: 12 Years of Experience

in Protecting Employee Rights, 5 Ga. L.Rev. 622 (1971). 30, 34

House Judiciary Comm. Report, No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1964) ......................................... 15

H.R. Rep. No. 741, 86th Cong., 1st Sess. (1959)........ 27

2 A Moore's Federal Practice (2d Edition 1972) ........ 11

vii

Page

2 NLRB, Legislative History of the Labor-Management

Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959 ( 1 9 5 9 ) ........ 29

Note, The Election Labyrinth: An Inquiry into

Title IV of the LMRDA, 43 N.Y.U. L.Rev. 336 (1968) . . 35

Rauh, LMRDA-Enforce It or Repeal It, 6 Ga. L.Rev.

643 (1971) ......................................... 35

S. Rep. NO. 187, 86th Cong., 1st Sess. (1959)........ 27

Sub-Committee on Labor of the Senate Committee

on Labor and Public Welfare, 92nd Cong., 2d

Sess., Legislative History of the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Act of 1972 (Comm. Print 1972) . . . 50

5 Wright and Miller, Federal Practice and

Procedure: Civil (1st Edition 1969) .............. 11

V l l l

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 73-1722

JAMES A. TUCKER, et al. ,

Appellants,

V.

TOBACCO WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UNION

AFL-CIO, CLC, LOCAL 183, AND TOBACCO

WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UNION, AFL-CIO,

CLC,

Appellees,

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Middle District Of North Carolina

Durham Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the district court erred in dismissing this action

in which facts were alleged and admitted constituting a prima

facie case of racially discriminatory union election practices

in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section

1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 on the ground, that Title iv of

the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959 imposes

an exclusive remedy for challenging union elections?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case of racial discrimination in union election prac

tices comes here on appeal from a pre-trial order of dismissal

of the United States District Court for the Middle District of

North Carolina, Durham Division, entered April 19, 1973. The

appeal involves the important issue as to whether Title iv of the

Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959, 29 U.S.C.

§§ 401 e_t seg. , precludes private enforcement of the prohibition

against discrimination in union election practices under Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e e_t seg. ,

and Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981^

This Court has jurisdiction of the appeal under 28 U.S.C. § 1291.

On January 20, 1972, plaintiff-appellant James A. Tucker

executed a charge of racial discrimination against defendants

Local 183, Tobacco Workers International Union, AFL-CIO, CLC and

Tobacco Workers International Union, AFL-CIO, CLC for filing with

I

Ithe Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in behalf of himself

and other black union members. The charge was received by the

EEOC on January 31, 1972. (A. 32-34). Tucker charged that the

local and international unions had allowed an ineligible white

I

employee to be nominated and elected to serve as the representative

from a historically black work area at the American Tobacco Com

pany in Durham, North Carolina on the union Shop Committee.

On May 8, 1972, Tucker and one hundred other black employees

of American Tobacco Company filed their complaint in federal

district court in their own behalf and as a class action. Plain

tiffs alleged that defendant unions' election practices discrimi

nated against black members and employees of American Tobacco

- 2 -

Company in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000 e_t seq. , and Section 1 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. §1981. Plaintiffs prayed for temporary and

permanent injunctions (A. 3-13). Defendants answered on June 22,

1972 interposing several defenses. (A. 14-20).

On August 4, 1972, Tucker received a letter from the EEOC

advising him that the Commission had been unable to obtain volun

tary compliance and authorizing him to file suit (A. 35). Plain

tiffs then, on August 11, 1972, moved to amend their complaint to

allege the necessary jurisdictional prequisites for bringing an

action under Title VII (A. 27-31). The district court granted

the motion with the consent of the defendants on October 11,

1972 (A. 36) .

Also, on August 11, 1972 plaintiffs moved for preliminary

injunction (A. 27-29). On October 24, 1972, defendants responded

to the motion and further moved the district court to dismiss the

action in its entirety (A. 37-41). Defendants argued that the

Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act deprived the court

of jurisdiction (A. 42-53). Plaintiffs responded,arguing that

Title VII and § 1981 conferred jurisdiction on the court to

adjudicate racially discriminatory union election practices (A.

54-59). On January 12, 1973, plaintiffs moved for leave to file

a second amendment to the complaint praying for monetary relief

in behalf of the plaintiff Tucker for the money he would have

earned as Shop Committeeman during 1972 (A. 68-69). The motion

was granted with the consent of the defendants (A. 70—72). On

February 9, 1973, defendants answered the second amendment

- 3 -

(A. 73-74).

On January 11, 1973, plaintiffs filed interrogatories to

defendants (A. 60-67), which defendants answered on March 13,

1972 (A. 76-83).

Oral argument on defendants' motion to dismiss was heard

by the court on April 2, 1973. The Memorandum Order of April 9,

1973 stated that the motion should be allowed and instructed,

defendants' counsel to present a proposed order setting forth

proposed findings of fact and conclusionsof law. On April 19,

1973, the district court entered the Order of Dismissal. The

primary finding of fact is that the controversy is a dispute over

an internal union election. No mention is made of the racial

discrimination alleged by the plaintiffs (A. 85-86). The

court concluded that the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure

Act is an exclusive administrative remedy for internal union election

Idisputes (A. 86-88).

Plaintiffs filed their notice of appeal on May 10, 1973 (A.

89-90). Plaintiffs here seek reversal of the district court's

judgment that the Labor-Management Reporting and. Disclosure Act

precludes consideration on the merits of actions brought under

Title VII and Section 1981 charging racial discrimination in

union election practices.

- 4 -

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The Tobacco Workers International Union, AFL-CIO, CLC

[hereinafter "International Union"] is an international union with

principal offices and headquarters in Washington, D.C. The

International Union operates in North Carolina through its several

local unions (A. 6, 15). One of these local unions is Local 183,

Tobacco Workers International Union, AFL-CIO, CLC [hereinafter

"Local 183"], located in Durham, North Carolina, all of whose

members are, or have been, employees of the American Tobacco

Company in Durham (A. 6, 15). Local 183 has approximately 1200

members of whom approximately 200 to 300 are black (A. 6, 15, 25).

Local 183 operates pursuant to the Constitution of the Inter

national Union and its own bylaws. For many years, Local 183 has

had a collective bargaining agreement establishing terms and

conditions of employment with the American Tobacco Company (A.

6, 15).

Before 1964, Local 183 was historically an all white local

representing workers in traditionally white jobs and departments

at American Tobacco Company in Durham (A. 7, 15, 77). Local 204,

Tobacco Workers International Union, AFL-CIO, CLC [hereinafter

"Local 204"] was the much smaller black counterpart of Local 183

representing workers in traditionally black jobs and departments

(A. 7, 15, 76). Local 183 had no black members as of 1963 (A. 7,

15, 77). Prior to at least March, 1964, American Tobacco Company

had a policy of limiting black employees to employment in certain

job categories (A. 77).

- 5 -

In 1964, the International Union urged Local 183 and Local

204 to merge so that the American Tobacco Company, a government

contractor, would not be in violation of Executive Order 10925 by

engaging in collective bargaining with racially identifiable local

unions (A. 7, 15, 77). The Defense Supply Agency and represen

tatives from the President's Committee on Equal Employment Oppor

tunity also urged the merger of the local unions so that the American

Tobacco Company would be able to continue to do business with

the United States (A. 77).

Subsequently, representatives of the two local unions met to

negotiate terms of merger. One of the hey matters of negotiation

was representation on the shop Committee which had and still has

the responsibility of handling all grievances arising under the

collective bargaining agreement and negotiating with the Company

for new collective bargaining agreements (A. 7, 15). Local 204

representatives proposed that Local 183's Shop Committee be in

creased from 8 to 13 members with the 5 new positions to be filled

by former members of Local 204 which would have been black persons

(A. 7, 15). Following negotiation on this matter, it was agreed

that the Shop Committee be increased from 8 to 11 members.

Eleven departments or work areas were designated for the purpose

of electing members to the Shop Committee; 8 departments or work

areas were those formerly represented by Local 183 and tradition

ally staffed by white workers and 3 were those formerly repre

sented by Local 183 and traditionally staffed by black workers

(A. 7, 15). The traditionally black departments or work areas

were designated "Area 1," "Area 2," and "Area 3." The election

- 6 -

procedure of the Local has always provided that candidates

actually working in a department or work area were eligible to run,

although the local membership at large could nominate candidates

and choose among them at the time of election (A. 9, 15, 66-67).

The merger agreement was ratified by the members of Local 204

on January 10, 1964 and by the members of Local 183 on January 14,

1964, becoming effective on January 31, 1964 (A. 7, 15). The

merger provision dealing with representation on the Shop Committee

was subsequently made a part of the Local 183 Bylaws as provided

for in the agreement (A. 8, 15, 26, 66).

James A, Tucker, a black member, was president of Local 204

at the time of merger. In each of the succeeding seven elections

after the merger in January, 1964, Tucker was nominated and

elected as the representative on the Shop Committee for Area 3

until the election held in December 3, 1971 (A. 8, 15, 62-63,

78). At the time of the merger, more than 50 persons worked in

Area 3 of whom 1 was white; at the time of the December, 1971

election, more than 50 persons worked in Area 3 of whom 3 were

white (A. 9, 16, 80).

In October, 1971, Tucker was r; nominated. Elbert Vaughn, a

white member, was also nominated.

Immediate objections were raised to Vaughn's eligibility to

be a candidate for representative from Area 3 by Tucker and other

black members on the ground that Vaughn did not in fact work in

Area 3 as required by the merger agreement and by bylaws.

Vaughn has been a member of the local and international since

- 7 -

1946 (A. 78) and has been an employee of T^erican Tobacco since

at least that time (A. 79). He has held various offices of the

local union over the years (A. 78). He was a trustee at the time

of merger (A. 78). He served as Shop Committeeman for six years

before merger from 1957 to 1963. He served as Shop Committeeman

for five years after merger from 1964 to 1969. On each of these

occasions he was the representative on the shop Committee from the

area designated as American Suppliers, and now known as the Leaf

Division, one of the eight original "white" departments. During

all of these years he held the same job which is classified as

Vacuum Operator and Maintenance. He was, of course, initially

assigned to that job at a time when American Tobacco made

job assignments on a racial basis (A. 78, 79).

In October of 1971 when Vaughn was nominated to be the

representative from Area 3, he was still holding exactly the same

job - Vacuum Operator and Maintenance - which he had held when he

served on thf Shop Committee for the six years before and for the

five years after merger as the representative of the American

Suppliers division or, as it is now known, the Leaf Division

(A. 79). The defendants have nowhere in this case shown, alleged,

or even suggested why Vaughn had been considered to be a repre

sentative of American Suppliers for many years and then suddenly

to be eligible to represent Area 3 despite the fact that his

job with T^erican Tobacco remained the same.

The objections to Vaughn's candidacy were referred by the

President of Local 183, Rudolph Hobby, to the International Union.

After an investigation by an International Union Vice-President,

- 8 -

the International Union President, Rene Rondou, determined that

1/Vaughn was eligible (A. 8-9, 15, 79).

On December 3, 1971, the election was held. Elbert Vaughn

received 252 votes and James Tucker 207 votes among the member

ship at large of Local 183 (A. 9, 16). On January 1, 1972,

Elbert Vaughn assumed office as representative for Area 3 on the

Shop Committee for the year 1972 (A. 9, 16).

This suit was filed on May 8, 1972 by one hundred black

employees of American Tobacco Company who are affected by the

collective agreement administered by the unions and the

I

Company. Ninety of the 200-300 black members of Local 183 arej

plaintiffs in this action as are twenty-five of the 50-60 persons

who work in Area 3. They claim that the defendants have engaged

in racial discrimination by permitting Elbert Vaughn to be nomi

nated and elected and to serve as Shop Committeeman from Area 3.

~ The defendants claimed (A. 44) and the court found (A. 87)

that the plaintiffs failed to exhaust internal union remedies.

The only remedy adverted to by the defendants was the inter

national's national convention held in September, 1972 (A. 44).

The convention was nearly a year after the nomination dispute,

nine months after the election and four months after this suit had

been filed.

- 9 -

Argument

I.

Title VII Of The Civil Rights Act Of 1964

And Section 1 Of The Civil Rights Act Of

1866 Each Confer Federal Jurisdiction For An

Action Challenging Racial Discrimination

In Election Practices Of Merged Black And

White Local Unions.

In this part of the brief we show that plaintiffs have

alleged and defendants have admitted facts sufficient to state

claims for relief under the Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and 1964, put

ting aside for the moment consideration of Title IV of the

Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA) which the

district court thought to be dispositive of the case. In Part

II we show that the LMRDA does not preclude consideration of

plaintiffs' action.

A. The gravamen of plaintiffs' complaint, racial discrim

ination manifest in an adverse candidate eligibility

ruling, was ignored by the District Judge.

The district judge decided as a matter of law that the

court lacked jurisdiction to consider the merits of the contro

versy (A. 86-88). The court concluded that the dispute is

governed by sections 402 and 403 of the Labor-Management Reporting

and Disclosure Act of 1959 (hereafter, LMRDA), 29 U.S.C. §§ 482,

483 thus requiring that plaintiffs exhaust available union remedies

concerning their grievance and complain to the Secretary of Labor

who then investigates, seeks voluntary compliance and determines

if probable cause exists for him — not th«.> plaintiffs — to

- 10 -

bring a civil action against the union. The factual basis

of the decision is the court's characterization of the contro

versy as simply "a dispute over an internal union election,"

without any mention of plaintiffs' allegations of racial dis

crimination.

The gravamen of the complaint by the one hundred black

employees of American Tobacco Company is that the local and

international union, their bargaining representatives, permitted

an ineligible white man, Elbert Vaughn, to be nominated and

elected over the black candidate, James Tucker, as the

representative of one of the three historically black work

areas on the eleven-member union shop committee which processes

grievances, administers the collective agreement and negotiates

new agreements. The plaintiffs said in the district court

that these actions by their unions constituted racial discrimina

tion.

If an action for racial discrimination is maintainable,

these allegations are sufficient standing alone to withstand

a motion to dismiss. See, Norman v. Missouri Pacific RR. Co.,

414 F.2d 73 (8th Cir. 1969); 5 Wright and Miller, Federal Practice

and Procedure; Civil §§ 1349, 1350 (1st Edition 1969); 2A

Moore's Federal Practice, § 12.08 (2d Edition 1972).

In addition to the verified allegations supporting

plaintiffs' claims of discrimination, there were a whole battery

of facts which had been admitted by the defendants at the time

the case was dismissed:

- 11 -

(1) There is a historical background of racial

segregation and discrimination by the employer

and union:

(a) The defendants have admitted that at

least until 1964, American Tobacco limited

black employees to employment in certain job

categories. (Defendants' Answers to Inter-

27rogatories, A. 77)

(b) Defendants have admitted that until

January, 1954 there were racially segregated,

dual local unions at American Tobacco in Durham.

(Answers to Interrogatories; A. 76-77). There

were no blacks in Local 183 until after merger

(A. 77).^

(2) A crucial issue in the negotiations leading to

the merger agreement of the black and white locals

was the number of additional positions on the shop

committee. The black local had asked for five and

received three representatives from the work areas

it had previously represented.

American Tobacco's discriminatory policies were consistent

with those of the industry, Quarles v. Phillip Morris, 279

F. Supp. 505, 509-14 (E.D. Va. 1958); Robinson v. Lorillard, 444

F.2d 791, 794 (4th Cir. 1971), and with its neighboring Reidsville

facility. See Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, Russell v.

American Tobacco Co. No. C-2-G-68, M.D.N.C. Greensboro Div. ,

5 EPD § 8447 (M.D.N.C. 1973).

^ The discriminat ry practices of the international and local

is also consistent with findings of discrimination by this

international, Robinson v. Lorillard, supra; Russell v. American

- 12 -

)

(3) Merger was pushed by federal agencies and

the international union in order to keep American

Tobacco from losing federal contracts (A. 77).

(4) The black plaintiff, James Tucker, who was

the president of the black local at the time of

merger had served as representative for the nearly

all-black area continuously from merger to the time

of the disputed election.

(5) Elbert Vaughn, the white candidate for Area 3

in 1971 had previously served before and after merger

from 1957 to 1969, with the exception of 1964, as

the representative for the American Suppliers, or as

it is now called, the Leaf Division, one of the

historically white work areas which had been repre

sented by the white local on the shop committee.

(Defendants' Answers to Interrogatories, A. 79.)

(6) At the time Vaughn's eligibility to serve as

the representative from Area 3 was challenged in

the local and international unions, Vaughn had

exactly the same job, Vacuiam Operator and Maintenance,

^ (Continued)

Tobacco, supra, and by sister locals, Robinson v. Lorillard,

supra; Russell v. American Tobacco, supra.

- 13 -

which he had held during the 11 years he

represented the Leaf Division. (Defendants'

Answers to Interrogatories, A. 79.)

(7) Once the eligibility issue was decided

against to Tucker and the other black Area

3 and American Tobacco Workers, the local union's

election procedures permitted the discrimination

of which plaintiffs complaint. Although blacks

constitute all but 3 of the 50 or 60 workers in

Area 3 (A. 9; 80), they represent only somewhere

between 200 and 300 of the 1200 or so members of

the local (A. 6; 80). Representatives to the

shop committee must be assigned to the work area

they represent, but they may be nominated by any

member of the local and are elected at large.

(A. 9; 80).

There is no mention or consideration given by the court

below to these undisputed facts bearing upon plaintiffs' claim of

discrimination. They are entirely ignored.

- 14 -

I

B . Racial Discrimination Manifested In Union Election

Practices is Prohibited By Section 703(c) Of The

Civil Rights Act Of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2QQ0e-2(c).

Section 703(c) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-2 (c) states:

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for

a labor organization -

(1) to exclude or to expel from its membership,

or otherwise to discriminate against, any individual

because of his race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin;

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify its member

ship or applicants for membership, or to classify or

fail or refuse to refer for employment any individual,

in any way which would deprive or tend to deprive any

individual of employment opportunities, or would limit

such employment opportunities or otherwise adversely

affect his status as an employee or as an applicant

for employment, because of such individual's race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin; or

(3) to cause or attempt to cause an employer to

discriminate against an individual in violation of this

section. 4/

The comprehensive scope of the prohibition is consistent

with the broad purpose of Title VII, "to eliminate, through the

utilization of formal and informal remedial procedures, dis

crimination in employment based on race, color, religion, or

national origin." House Judiciary Comm. Report, No. 914, 88th

Cong., 1st Sess. ___ (1954) in EEOC, Legislative History of Title

VII and XI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 2026 (1964). The

discrimination provision remained essentially unchanged from

the report of a bill by the House Judiciary Committee through the

adoption of the Dirksen-Mansfield substitute by the Senate and

the House with the exception of a House floor amendment that

"sex" be added as one of the forbidden bases of discrimination.

Id. at 1005 (1954). Congress thereby indicated that the in

ternal affairs of unions were to be regulated in the interest

of eliminating discrimination just as earlier labor relations

legislation had on behalf of other desirable social ends.

- 15 -

Section 703 (c) (1) is specifically addressed to dis

criminatory exclusion from merabersliip in a labor organization,

an evil which previous labor relations legislation had avoided

addressing. See, infra at 37-44. Nevertheless, Section 703 (c) (1)

also makes it illegal for a union "otherwise to discriminate,"

an omnibus provision, spelled out, in part, in Sections 703(c)

(2) and 703(d), designed to ensure that the full rights of

membership in a labor organization will not be impaired in

any way. The broad terms employed in these sections evidence

the Congressional purpose of prohibiting all forms of racial

discrimination in union affairs and activities. We would

certainly think that the discrimination detailed in the previous

subsection (lA) is prohibited by section 703 (c) (1).

We know of no case exactly like this one where black union

members invoked Title VII complaining of discriminatory practices

by a union which denied the election of a black member. However,

the courts have consistently recognized that regulating leadership

arrangements and union elections is necessary to insure that the

merger of segregated unions under the auspices of Title VII is

effectively accomplished. In United States v. Chesapeake and

Ohio Ry Co., 4 Employment Practices Decisions [hereafter, EPD]

§ 7637 (E.D. Va- 1971), vacated in part and remanded on other

grounds, 471 F.2d 582 (4th Cir. 1972) the order of the court to

remedy the effects of past union practice of maintaining segregated

locals included provisions requiring consolidation of leadership.

- 16 -

allocating various local and committee offices within five

years and reporting of election results to the court to insure

minority group members adequate representation at all levels

of leadership. Similar provisions are included in the Amended

Decree at 8-12 in Rock v. Norfolk and Western Ry. Co., C.A.

No. 258-69-N (E.D. Va. 1972), aff'd, 473 F.2d 1344 (4th Cir.

1973) . Comparable arrangements for Negro participation in

the leadership of the merged union were ordered in Hicks v.

Crown Zellerbach Corp., 310 F. Supp. 536 (E.D. La. 1970) and

Chicago Fed, of Musicians, Local 10 v. American Fed, of Musicians,

2 EPD § 10,212 (N.D. 111. 1964). In English v. Seaboard Coast

Line RR Co., 4 EPD § 7645 (S.D. Ga. 1972) the order requiring

two segregated union locals to merge included provisions that

offices in the consolidated local be allocated between the

present holders of such offices in the segregated locals. ,In |

Long V. Georgia Kraft Co., 445 F.2d 331 (5th Cir. 1972) the Court

held that the use of protective transitional measures was

unnecessary where Negroes had already achieved a leadership' role

I

in the consolidated union. The importance of access to leadership

positions for minority members of merged unions is unquestioned.

The facts of this case are similar to those just cited and

discussed. Here there also was a federal requirement for the

merger of segregated locals. Negotiations between the locals

resulted in some measure of representation in union affairs by

_ 17

blacks. The arrangements agreed to lacked many of the protections

for blacks which are present in the decisions mentioned above.

For example, at the time of merger, the agreement would have

allowed someone outside of Area 3 to nominate the single white

assigned to Area 3 and to be elected as the Area 3 representa

tive by the predominantly white local. But what was done here

was something very different. A white outsider was imposed

upon the nearly all-black department as its representative.

Absent the merger agreement,plaintiffs have stated a claim of

discrimination. The violation of the merger agreement fully

Ibrings into play the necessity for affording blacks

protection in intra-union affairs as articulated in the Title

IVII merger cases.

Furthermore, courts have intruded into the internal affairs

of unions under authority conferred by Title VII in a variety

I jof other instances. In United States v. International

Longshoremen, 460 F.2d 497 (4th Cir. 1972), this Court ruled

that maintenance of segregated union locals is a per se

i/

violation of Section 703 (c) (2) of the Act and approved as v/ell the

abolition of the system of separate hiring halls. Alternating

the referrals of members for employment and hiring by racial

classification was deemed appropriate relief for racially

discriminatory union practices in Local 53, International Ass'n

of Heat and Frost I and A Wkrs v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir.

1969). A union-run referral program, neutral on its face, that

- 18 -

would have present and future discriminatory effect was

deemed an unlawful employment practice in United States v.

Sheet Metal Wkrs Int. Ass'n Local 36 (8th Cir. 1969). A

virtually all-white union and its apprenticeship committee were

charged with the affirmative duty to effectively inform

potential Negro applicants about membership, work referral and

apprenticeship training matters in United States v. Local 86,

International Ass'n of Bridge, S. O. and R. Ironworkers, 316

F. Supp. 202 (W.D. Wash. 1970), aff'd. 443 F.2d 544 (9th Cir.

1971) . No less are these plaintiffs entitled to consideration!

on the merits under Title VII.

The only case we have found which deals with discrimination

in union elections with regard to Title VII is Shultz v. Local

1291, International Longshoremen, 338 F. Supp. 1204 (E.D. Pa.

1972) , aff'd ■461 F.2d 1262 (3rd Cir. 1972), a case relied upon^

by the defendants below. Local 1291 was a case brought by the

Secretary of Labor under Title IV of the LMRDA, not by private

parties or the Government under Title VII of the Civil Rights

t

Act of 1964. The court agreed with the Secretary's contention

that racial allocations of union officers violated the

"reasonable qualification" provision of Section 401 of the LMRDA

(29 U.S.C. § 481) and also violated Title VII, 338 F. Supp.

at 1207-08. There was no evidence that the racial allocation

of officers was a necessary remedy for prior segregation. ^

^ Here there is no racial allocation of officers in the merger

agreement involved in this case. The agreement simply affords

- 19

Lq ca1 1291 thus stands firmly for the proposition

that racial discrimination in union election practices is

prohibited by Title VII.

In part II of our brief we show that the fact that some

6 /

instances of racial discrimination are also forbidden by

LMRDA does not in any way interfere with plaintiffs' right

to invoke their Title VII remedies.

In conclusion, therefore, it is clear that plaintiffs

have made sufficient allegations to support their Title VII

claim. u

Indeed, the undisputed facts already

5/ (Continued) |

blacks a reasonable chance for representation on the Shop

Committee by requiring that representatives be identified with the

areas they represent in the context of a work situation, where

there is considerable racial segregation. The merger cases

discussed above make clear, however, that in some situations

racial allocations are necessary to remedy unlawful segregation.

6/ The basis for the Secretary of Labor's complaint in Local

1291 was that a by-law provision desegregating certain offices

as white and black was not a "reasonable qualification" under

Section 401 of LMRDA. Whether plaintiffs' complaint in this

case would or could be found by the Secretary to come within

the "reasonable qualification" provision or some other provi

sion which would in turn cause him to bring suit is not certain.

_7_/ It is also clear that they have satisfied all of the juris

dictional requirements for bringing the action which are:

(1) that they have filed a charge with the EEOC, (2) that they

have received an appropriate notice from the EEOC advising them

of their right to initiate an action in an appropriate federal

district court, and (3) that an action was initiated in a

federal district court within thirty days of receipt of the

notice. McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, ___ U.S. ___,36 L.Ed.2d

_ 20 -

_8V

established constitute a prima facie case of unlawful racial

discrimination under Title VII. See, McDonnell Douglas Corp.

V. Green, supra. These facts, if unexplained, entitle plain

tiffs to relief.

C. The Racial Discrimination Alleged in This Case States

a Cause of Action under Section 1 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

Black persons have a right independent of Title VII or

other statutes prohibiting discrimination because of race in

employment to seek relief from racially discriminatory employ

ment practices of employers and unions under Section 1 of the

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981. Section 1981

states:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the

United States shall have the same right in

every State and Territory to make and enforce

contracts, to sue, be parties, given evidence,

and to the full and equal benefit of all laws

proceedings for the purpose of persons and

property as is enjoyed by white citizens. ...

In Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968), the

Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of a parallel pro

vision of Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1982,

7/ (Continued)

668, 675-76 (1973); Johnson v. Seaboard Airline RR Co., 405

F.2d 645 (4th Cir. 1968); Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry.

Co., 406 F.2d 399 (5th Cir. 1969); Choates v. Caterpillar

Truck Co., 402 F.2d 357 (7th Cir. 1968). Plaintiffs have sat

isfied these jurisdictional prerequisites. (A. 27-36)

_§/ pp. 11-14, supra.

_ 21 _

which guarantees all citizens the same right as is enjoyed by

white citizens in real and personal property transactions as

a valid exercise of Congress' power to enact legislation to

enforce the Thirteenth Amendment.

In Scott V. Young, 421 F .2d 143 (4th Cir. 1970), this

Court, in a case involving the discriminatory availability of

contractual opportunity in a recreational facility, stated,

after reviewing Jones, that "the provision invoked in this

case, § 1981, the sister to § 1982, must be construed in a

similar broad fashion." Id. at 145. Subsequently, the court

has approved the award of back pay to a Negro worker subject

to discriminatory employment practices under section 1981.

Brown v. Gaston City Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir.

1972). In Jamison v. Olga Coal Co., 335 F. Supp. 454 (S.D.

W. Va. 1971), the court ruled that plaintiffs have stated a

cause of action under § 1981 by alleging racial discrimination

in promotion and job opportunities by employer and unions. See

also, Broadnax v. Burlington Industries Incorporated, C.A.

No. C-160-G-71 (M.D. N.C. 1971). The rulings of other circuits

are also to the effect that § 1981 embraces private discrimina

tion in employment. See e.g..Yovmg v. international Telephone and

Telegraph Co., 438 F.2d 757 (3rd Cir. 1971); Sanders v. Dobbs

Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097 (5th Cir. 1970).

- 22 -

The Seventh Circuit has had occasion to address the issue

of whether discriminatory union practices, as opposed to

employer discrimination, is also covered by Section 1981.

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works, 427 F.2d 476 (7th Cir. 1970),

cert. denied, 400 U.S. 911 (1970). After a careful reexamina

tion of the legislative history and Supreme Court authority

the Court concluded that § 1981 applies to employment discrim

ination and also to discriminatory union activity because a

member's relationship to his union is essentially contractual:

Racial discrimination in employment by unions

as well as by employers is barred by Section

1981. The relationship between an employee

and a union is essentially one of contract.

Accordingly, in the performance of its func

tions as agent for the employees a union cannot

discriminate against some of its members on the

basis of race. Washington v. Baugh Construction

Co., 313 F. Supp. 598 (W.D. Wash. 1969); Dobbins

V. Local 212, IBEW, 292 F. Supp. 413 (S.D. Ohio

1968). Id. at 483.

The Waters characterization of the member/union relation

ship as contractual is consistent with decisions construing

Section 301 of the National Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S.C.I

i

§ 185. Parks v. International Brotherhood of Electrica1 Workers,

314 F.2d 886, 914-16 (4th Cir. 1963), cert. denied, 372 U.S.

976 (1963), and is consistent with the prevailing law in the

states. See, International Association of Machinists v.

Gonzales, 356 U.S. 617 (1958).

_ 23 _

There are several § 1981 contractual bases for plain

tiffs’ claim. First, the plaintiffs allege that the defendants

violated its own by-laws by letting Vaughn be nominated and

elected to the Shop Committee and that this by-law violation

was done with a discriminatory purpose and had a discrimina

tory effect. Secondly, the plaintiffs assert that these

actions violate the 1964 merger agreement between the black

and white locals. Third, the discrimination affects the

black employees' employment relationship with the employer

Iby interfering with their rights to representation. See, j

Western Addition Community Organization v. N.L.R.B., ____

F.2d ____, No. 71-1656 (D.C. Cir., June 29, 1973). The

plaintiffs have clearly stated a claim under § 1981.

- 24 -

II,

The District Court Erred in Dismissing This

Case in Which Facts Were Alleged and Admitted

Constituting a Prima Facie Violation of the

Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and 1964 on the

Ground That Title IV of the Labor Relations

and Disclosure Act of 1959 Imposes an Exclu

sive Remedy for Challenging Union Elections.

We have previously shown that admitted facts in this case

constitute violations of both Title VII and the Civil Rights

Act of 1866. These claims were apparently thought by the

district court to be irrelevant since they were ignored. The

decision must be read, therefore, as holding that even if a I

case of racial discrimination were established, dismissal is

I

required on the ground that Title IV of LMRDA requires resort

to the Secretary of Labor who may, if he chooses, bring suit.

We show in this part of the brief that there is nothing ̂

in the statute, its legislative history, or in the decisions !

construing it to support the conclusion that private actions

challenging union election practices under the Civil Rights

!

Acts are somehow barred by the LMRDA. And finally, we show

that other labor statutes which have their own remedies have

not been held to bar Title VII claims when their prohibitions

overlap Title VII.

- 25 -

A. The Language and Legislative History of the LMRDA

Demonstrate That Congress Did Not Intend That the

Act Deal with the Evil of Racial Discrimination in

Union Activities.

The district judge, after quoting from the provisions of

Section 482 setting forth the procedures for invoking LMRDA

protections which admittedly were not pursued in this case,

quoted and relied upon Section 483, 29 U.S.C. § 482:

The remedy provided by this subchapter for

challenging an election already conducted

shall be exclusive.

The court did not refer to Section 603 of the Act, 29 U.S.C.

§ 523, which specifically preserves all other federal rights

and remedies of union members,

[E]xcept as explicitly provided to the con- '

trary, nothing in this chapter shall take

away any right or bar any remedy to which

members of a labor organization are entitled

under such other Federal law or law of any State. I!

Nor did the court mention the fact that the LMRDA does not

address the matter of racial discrimination.

The Supreme Court has counseled against slavish reliahce

I

on one or another provision, phrase or word of the LMRDA:

We have cautioned against a literal reading of

congressional labor legislation; such legisla

tion is often the product of conflict and

compromise between strongly held and opposite

views, and its proper construction frequently

requires consideration of its wording against

the background of its legislative history and in

light of the general objectives Congress sought

to achieve. ... The LMRDA is no exception.

26 -

. _9/Wirtz V, Local 153, G.B.B.A., 389 U.S. 463, 468 (1968).

It is significant that the evil of racial discrimination

in employment practices is not even alluded to in the Congres

sional declaration of findings, purposes and policy at section

2 of the Act, 29 U.S.C. 401. The Senate and House Reports

indicate that Congress was specifically concerned with foster

ing union democracy against such perils as unfairly entrenched

leadership, corruption and racketeering. S. Rep. No. 187,

86th Cong., 1st Sess. 2-36 (1959); H.R. Rep. No. 741, 86th I

ICong., 1st Sess. 6-27 (1959). I

The absence of prohibitions against racial discrimination

was intentional. Congress was not ready in 1959 to address

that issue. There were at least two unsuccessful efforts to

amend section 101(a), 29 U.S.C. §411, the equal rights provi-

ision of the union bill of rights section for just this purpose.

The Minority Supplementary Views in the House Report states

that;

9/ The Supreme Court elaborated its discussion in n. 6:

Archibald Cox, who actively participated in

shaping much of the LMRDA, has remarked:

The legislation contains more than its share of

problems for judicial interpretation because

much of the bill was written on the floor of

the Senate or House of Representatives and

because many sections contain calculated ambi

guities or political compromises essential to

- 2 7 -

This legislation has a bill of rights without

any guarantee of civil rights. As it first came

to us from the other body,, it did include some

mention, but woefully inadequate, of equal rights.

This was struck out in committee upon the motion

of two members. We, therefore, believe that if

there is to be a bill of rights in this legisla

tion it must most assuredly include a guarantee

of equal rights— the right of every working man to

join a union and not to be segregated within that

union because of race, creed, color, or national

origin.

Id. at 101. Representative Powell, one of the co-signers of

the Minority Supplementary Views, carried the struggle to

amend the equal rights provision to the floor by proposing

the following amendment:

Except that no labor organization shall dis

criminate unfairly in its representation of all

employees in the negotiation and administration

of collective bargaining agreements, or refuse

membership, segregate or expel any person on the

grounds of race, religion, color, sex, or national

origin.

In answer to this specific amendment. Representative Landrum,

a principal sponsor of the House bill, replied:

9/ (Continued)

secure a majority. Consequently, in resolving

them the courts would be well advised to seek

out the underlying rationale without placing

great emphasis upon close construction of the

words. Cox, Internal Affairs of Labor Unions

under the Labor Reform Act of 1959, 58 Mich.

L. Rev. 819, 852 (1960).

- 28 -

)

I would direct your attention to a careful

reading of section 101 (a) of the amendment which

I have proposed, which says this: "Every member

of a labor organization shall have equal rights

within that organization," and then it enumerates

the things: to nominate candidates and to vote

in elections or referendums. We do not seek in

this legislation, in no way, no shape, no guise,

to tell the labor unions of this country who they

shall admit to their unions. No part of this

legislation attempts to do that. ... This law is

designed only to say that, if he is a member of

a union, he shall have equal rights.

Representative Griffin, the other principal sponsor of the

House bill, agreed:

The labor reform legislation before the House

at this time is directed at the regulation of the

internal affairs of unions. It does not touch or

deal in any way with the admission to, or retention

of, membership in a union. There is a proviso in

the Taft-Hartley Act which union leaders and the

union members want preserved. I refer to a proviso

in section 8(b) which reserves to unions the right

to prescribe rules and regulations for the admis

sion and retention of membership . ... The subject

of the [Powell] amendment is outside the scope of

the legislation and the hearings that were held on

labor reform legislation. Under the circumstances,

I urgently plead with the House riot to jeopardize

this legislation by adopting an amendment which is

so obviously designed for the purpose of killing

the bill.

10/The Powell amendment was defeated 215-160.

10/ 2 NLRB, Legislative History of the Labor-Management Report

ing and Disclosure Act of 1959, 1648-51 (1959); see, Aaron, The

Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959, 73 Harv.

L. Rev. 851, 860-61 (1960). The Senate accepted the House

version of the bill on this point.

- 29 -

This legislative history thus indicates that the exclu

sive LMRDA procedures of Title IV for challenging union

elections were not designed for claims of racial discrimina

tion and surely not for such claims involving the merger

agreement of two segregated unions by which a forme ly all-

white local admitted black members under governmental pressure.

It was not until the enactment of Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000eejt seq. that racial

discrimination in union practices was, in fact, sought to be

remedied. The felt necessity for subsequent legislation that

deals specifically with racial discrimination itself argues

against attributing to Congress the purpose in the LMRDA of

foreclosing a private action authorized by Title VII chal-

11/lenging discriminatory union electoral practices.

11 / In a recent post-enactment statement. Senator Griffin

commented:

That the right to join a union was not included

in the list of rights protected by Landrum-Griffin

was an understandable fact of political life at

the time of enactment, but the fact that some

unions continue to exclude minorities from the job

market despite subsequent enactment of equal

employment legislation is neither understandable

nor tolerable.

Griffin, The Landrum-Griffin Act: 12 Years of Experience in

Protecting Employee Rights, 5 Ga. L. Rev. 622, 624-25 (1971)

- 30 -

B. Judicial Decisions Applying Title IV of the LMRDA

Have Not Precluded Private Actions Challenging

Racially Discriminatory Union Election Practices.

Existing Supreme Court interpretations of the purpose of

Title IV provisions requiring an exclusive administrative

remedy are consistent with allowing private actions challeng

ing racial discrimination in union election practices. These

interpretations include (1) encouraging union democratic

processes by requiring, in the first instance, exhaustion of

union remedies, (2) reliance on the expertise of the Secre

tary of Labor by conferring on the Secretary the sole discre

tion to initiate judicial enforcement, and (3) reliance on

the Secretary of Labor to screen and centralize Title IV com

plaints. Calhoun v. Harvey, 379 U.S. 134, 140-41 (1964);

Wirtz V. Local 153, G.B.B.A., 389 U.S. 463, 470-71 (1968);

Wirtz V. Hotel Employees Union, 391 U.S. 492, 496-99 (1968);

Trbovitch v. United Mine Workers, 404 U.S. 528, 532-35 (1972),

As to encouraging union democracy, the Supreme Court has made

it clear that exhaustion is not required where the procedures

are controlled by the very individuals from whose discrimina

tory action the plaintiffs seek relief. Glover v. St. Louis-

12/

San Francisco R.R. Co., 393 U.S. 324 (1969). As to the

\2j The defendants’ claim of lack of such exhaustion by the

plaintiffs falls squarely within the Glover rule.

- 31 -

expertise of the Secretary of Labor, Congress has subsequently

specifically provided for the EEOC, not the Secretary of Labor,

to investigage and seek conciliation of racial discrimination

in employer and union employment practices. Failing voluntary

compliance. Title VII allows private actions. 42 U.S.C.

§§ 2000e-4 ^ seq. The establishment of the EEOC and procedures

for private actions under Title VII are also Congressionally

mandated accommodations with the screening and centralizing

function of the Secretary of Labor. Moreover, the Supreme

Court in Trbovitch read the purpose of the exclusive remedy

provisions of Title IV of the LMRDA narrowly, where there was

an absence of on-point legislatory history, to allow individual

complainants to intervene in Title IV actions initiated by the

Secretary.

Most Title IV cases decided by the courts concern the

election abuses contemplated by Congress. In the court below

defendants cited only one Title IV case concerning racial dis

crimination. Shultz V. Local 1291, International Longshoremen,

338 F. Supp. 1204 (E.D. Pa. 1972), aff'd, 461 F.2d 1262 (3rd

- 32 -

13/Cir. 1972), supra. Research reveals that Local 1291 is, in

fact, the only such case to arise. Local 1291 concerned whether

the racial allocation of union offices was within the "reasonable

qualification" provision of section 401 of the LMRDA. 29 U.S.C.

§ 481. Unlike the present private action brought under Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 1 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1866, Local 1291 was an action brought by the

Secretary of Labor under Title IV of the LMRDA. The case is

an instance of the Secretary seeking sanction for widening the

scope of his Title iv jurisdiction, but it is hardly precedent

for the proposition that the Secretary has exclusive jurisdiction

over such matters. The court stated explicitly:

It also appears that Rule 3(c)(3) [requiring

racial allocation of offices] amounts to an

unlawful employment practice within the meaning

of 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(c).

Id. at 1207. The court then, as a necessary part of the process

of decision, read into the Title iv of the LMRDA "reasonable

qualification" language what Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 prohibits:

13/ Another case cited by defendants in their Brief in Support

of Motion to Dismiss at A. 47-48, Saunders v. Shoemann, 80 LRRM

2903 (Ohio Ct. App. 1972), is, in fact, inapposite since it is

not a case in which racial discrimination was alleged or at

issue nor was it a federal court decision.

- 33 -

The Supreme Court, in speaking of [Title VII] but

with respect to unlawful employment practices by

employers, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2 (a), stated: "Dis

criminatory preference for any group, minority or

majority, is precisely and only what Congress has

proscribed. What is required by Congress is the

removal of artificial, arbitrary, and unnecessary

barriers to employment when the barriers operate

invidiously to discriminate on the basis of racial

or other impermissible classification. ... If an

employment practice which operates to exclude

Negroes cannot be shown to be related to the job

performance, the practice is prohibited." (Empha

added) [Emphasis added by judge] Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 ... We cannot consider as

reasonable for purposes of the Labor-Managem.ent

Reporting and Disclosure Act what would be con

sidered an unlawful employment practice under the

Civil Rights Act of 1954. I

Id. at 1207-08. The lesson of Local 1291 is that concur-

M /rent jurisdiction exists in some cases for raising the issue

of racial discrimination in union elections under Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Title IV of the LMRDA.

It is noteworthy that in LI4RDA cases Congress left the |I '

remedy of violations to the discretion of the Secretary of

15/

Labor. Title VII violations, on the other hand, were

14/ It is not clear that every case of racial discrimination,

or even this one, can be dealt with under Title IV. See fn. 15

supra.

15/ Critical evaluations of the non-reviewability of the

Secretary of Labor's discretion in determining whether a

Title IV action should be brought against a recalcitrant

union are not uncommon. See, e.g., Griffin, The Landrum-

Griffin Act: 12 Years of Experience in Protecting Employee

Rights, 5 Ga. L. Rev. 622, 625, 636-40 (1971); Note, The

- 34 -

determined by Congress to be of such importance so as to

allow aggrieved persons to seek judicial relief even where

the administrative agency found no cause for complaint.

Robinson v. Lorillard, supra.

The decision of the district judge that this action

should be dismissed for failure to resort to the purported

exclusive administrative remedy of Title IV of the LMRDA is

not within the purpose of the Act nor is it supported by any

prior decision. The decision below stands alone. LMRDA is

not a civil rights statute. At most, in some cases, some

claims of racial discrimination may be cognizable. However,

as we show in the following sub-part, other labor statutes

also now reach racial claims. But they have never been read

to preclude Civil Rights Act actions.

15/ (Continued)

Election Labyrinth: An Inquiry into Title IV of the LMRDA,

43 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 336, 359-86 (1968); Note, Election Remedies

Under the LMRDA, 78 Harv. L. Rev. 1617, 1623-34 (1968); see

also, Rauh, LMRDA— Enforce It or Repeal It, 6 Ga. L. Rev. 643

(1971) (failure of the Secretary to enforce LMRDA with respect

to United Mine Workers Union).

- 35 -

c. The Decision Below Stands Alone Holding That A Non-

Title VII Remedy for Racial Discrimination is

Exclusive Rather Than Alternative.

Although we know of no other Title VII case— and only

1 ^

one LMRDA case— involving racial discrimination in union

election practices, the courts have been presented with a

variety of cases where other remedies were available for

aggrieved minority workers in addition to Title VI. The

courts have rejected defendants' contentions that those other

remedies were exclusive and should be pursued before or

instead of Title VII. The plain message of those cases,

which are discussed below, is that Title VII is the principal

federal remedy for employment discrimination and that it is

always available despite the existence of any other remedy.

The district court decision stands alone in holding that black

plaintiffs having chosen to pursue their claims through

the EEOC and then into federal court under Title VII and

§ 1981 may not do so because of the existence of. another

possible federal remedy. We also show that post-enactment Title VII

legislative history makes clear the congressional intent to pre

serve all federal remedies against racial discrimination. And

16/ Shultz V. Local 1291, supra.

- 36 -

finally we show that the remedy to which the court below

would remit the plaintiffs is considerably less adequate

than that provided by Title VII and § 1981.

In a fashion similar to the LMRDA, the Railway Labor

Act (RLA) , 45 U.S.C. § 151 ejt seg. . provides exclusive

administrative remedies foj: unsettled grievances and craft

disputes in the National Adjustment Board, Brotherhood of

Locomotive Engineers v. Louisville & N.R. Co., 373 U.S. 33,

38 (1963), and in the National Mediation Board, Brotherhood of

Trainmen v. Howard. 343 U.S. 768 (1952), respectively.

Moreover, RLA law existed prior to Title VII making craft

classifications illegal if they were discriminatory. Steele

V. Louisville & N.R. Co., 323 U.S. 192 (1944) . However, such claims

had to be presented to the National Mediation Board before

resorting to the courts. Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen

V. Howard, 343 U.S. 768, 774-775; Howard v. St. Louis-

San Francisco Railway Company, 361 F.2d 905 (8th Cir. 1966),

cert, denied, 385 U.S. 986 (1966).

The Eighth Circuit was recently called upon to determine

whether black railroad employees were, after the enactment of

Title VII, still required to submit their claims of

discrimination to the Adjustment and Mediation Boards, which

the court had required in the Howard case. Norman v. Missouri

- 37 -

Pacific Railroad, 414 F.2d 73 (8th Cir. 1969). In Norman,

the district court had ruled "that only the National Mediation

Board under the Railway Labor Act had jurisdiction over the

matters alleged in the complaint and that Title VII of the

1964 Civil Rights Act did not revise or change existing law

relating to the Railway Labor Act." at 76. The Court

of Appeals concluded that the district court was wrong and

that Title VII was a new and expansive grant of rights not

to be limited by prior legislation.

"Surely Congress in the enactment of

Title VII had in mind the granting of a

new and enlarged basis for elimination of

racial and other discriminations in employ

ment. Title VII clearly is not a codification

of existing law but is an enactment of a

broad principle prohibiting discrimination

against any individual 'with respect to his

compensation, terms, conditions or privileges

of employment, because of...race, color,

religion, sex or national origin.'"

Id. at 83.

The Fifth Circuit has also rejected arguments advanced

by railroads and unions that cross-craft relief cannot be

required by a court in a Title VII case because Congress

had left matters of craft and class to the Railway Mediation

Board and the National Adjustment Board. United States v.

Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971).

The court noted that prior to Title VII "federal courts __

- 38 -

)

had the power to protect employees against invidious dis

crimination" under both the Railway Labor Act and National

Labor Relations Act. Id. at 454-455. The court then

observed:

"Supplementing the earlier enactments.

Title VII has expanded the scope of

judicial inquiry and augmented the power

of remedial relief in cases involving

discriminatory employment practices based

upon race, color, religion, sej^ or

national origin." j[d. at 455.— '

Thus, Title VII is in no way displaced as to the railroad

industry by the provisions of the RLA which also afford

"exclusive" remedies against racial discrimination. Title ^

VII was enacted as the principal weapon in the federal

arsenal to combat employment discrimination. Other remedies

remain in tact, but Title VII is always available.

The NLRA cases mentioned by the court in Jacksonville 1Terminal are also instructive on this point. For some ! '

30 years unions have had a duty of fair representation under

17/ See also. United States v. Chesapeake & Ohio Railway

Co., 471 F.2d 582 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, ____U.S.

_____ (1973), and Rock v. Norfolk and Western Ry.

Co., 473 F.2d 1344 (4th Cir. 1973), cert, denied, _____

U.S. ______ (1973), where this Court required cross-craft

relief notwithstanding the RLA. And see, Peters v. Missouri-

Pacific RR Co. , ____ F.2d ____ , 5 EPD § 8550 (5th Cir. 1973),

vAiere the court rejected the claim that the RLA duty to bargain

in good faith is a defense in a Title VII case.

' - 39 -

the National Labor Relations Act making it a violation of

that act to discriminate in its representation of its

members on the basis of race. Steele v. Louisville &

17/

Nashville R. Co.. 323 U.S. 192 (1944). Such dis

crimination is also, of course, a violation of Title VII.

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., supra. No court has ever held

that since NLRA remedies pre-date Title VII, they must be

pursued. See, Bales v. Union Camp Corp., 5 EPD § 8052

(S.D. Ga. 1972). Indeed even where an action was brought

i

unsuccessfully challenging a seniority system as racially

I

discriminatory in violation of the duty of fair representation.

17/ The violation of the duty of fair representation is an

unfair labor practice which may be pursued to the NLRB.

Local 12, United Rubber Works v. NLRB, 368 F.2d 12 (5th Cir.

1966) . However, such a complaint may be taken directly to '

court without resort to the NLRB, Vaca v. Sipes, 386 U.S.

171 (1967), notwithstanding the general rule that the labor

l>oard has exclusive jurisdiction over unfair labor practice

cases. Garner v. Tearasters Union, 346 U.S. 485 (1953).

This is so because the Board is thought to have no greater

expertise in such cases than the courts. Interestingly,,

Judge Gordon recently recognized this principle in refusing

to defer to the NLRB in a case involving Title VII and fair

representation claims against this international and a sister

local. Tippett v. Liggett & Myers Tobacco Company, 316 F.Supp,

292 (M.D.N.C. 1970). Certainly the same principles apply

here. The Secretary of Labor has no greater expertise than

the courts to hear claims under Title VII and § 1981. And

he clearly has less expertise than the EEOC.

- 40 -

V?hitfield v. United Steelworkers of America, 26 3 F-. 2d 546

(5th Cir. 1959) (per Wisdom, J.), cert, denied, 360 U.S.

902, a later case, brought under Title VII, attacking the

same seniority system was successfully ■ pursued. Taylor

V. Armco Steel Corp., 429 F.2d 498 (5th Cir. 1970) (per

Wisdom, J.).

Similarly, it is an unfair labor practice under the NLRA

to discharge an employee for concerted activity protesting

racially discriminatory practices by an employer because

}

tsuch activity is protected by Section 7 of NLRA.. NLRB

i

V. Tanner Motor Livery, Ltd., 349 F.2d 1, 4 (9th Cir. 1965);

Western Addition Community Organization v. NLRB, p. 24, supra

Significantly, this sort of concerted activity is treated

differently and given more protection under the NLRA

Ithan other sorts of concerted activity even where it is j

I I

disruptive of normal collective bargaining activities. '

Western Addition Community Organization v. NLRB, supra.

Such discharges are also remedial under Title VII. j

McDonnell-Douqlas Corp. v. Green, supra. When cases

arise under the NLRA, the courts give the act a construction

consistent with Title VII protections. But again, even

- 41 -