Roemer v Chisom Brief of Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 21, 1988

25 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Roemer v Chisom Brief of Amici Curiae, 1988. 66ce67cf-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b34efcfe-506b-4c1a-930f-354911e8fd2f/roemer-v-chisom-brief-of-amici-curiae. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

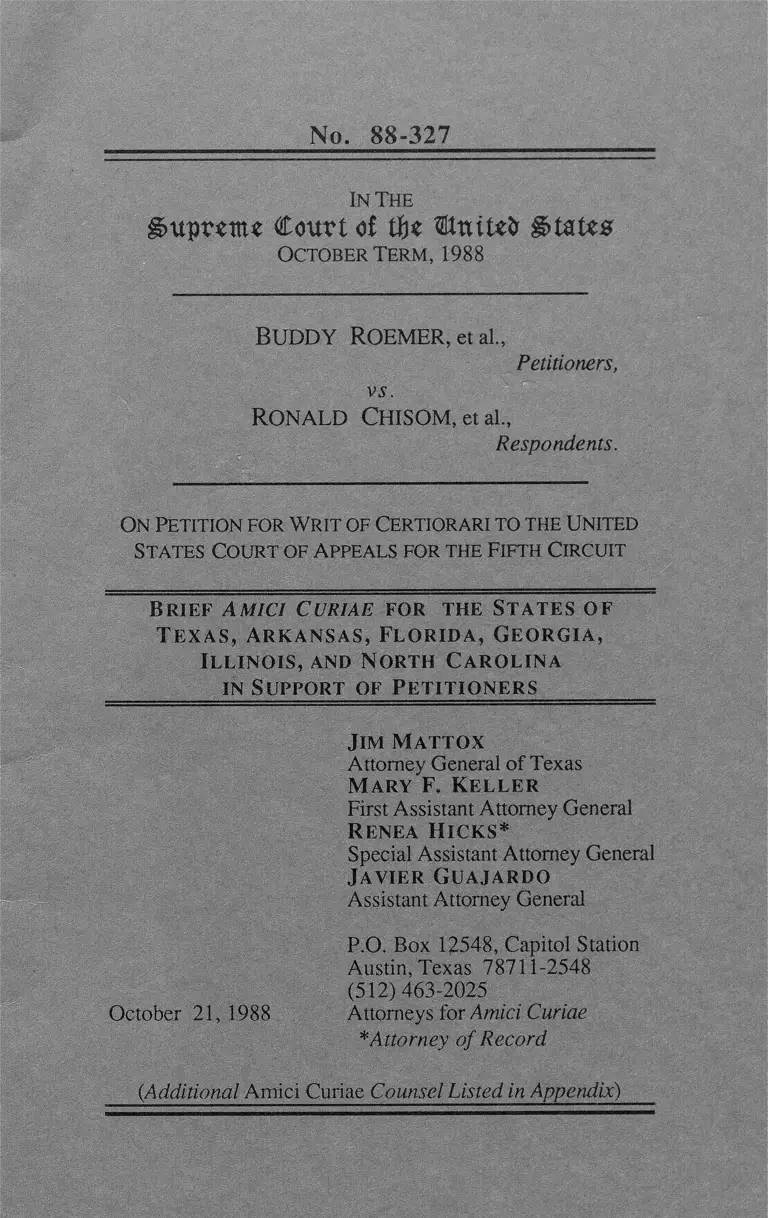

No. 88-327

In The

&upr«m« Court ot tfce flttnufr states

October term, 1988

BUDDY ROEMER, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Respondents.

ON PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

B R IE F A M IC I CURIAE FOR TH E S T A T E S O F

Texas, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia,

Illinois, and North Carolina

in Support of Petitioners

Jim Mattox

Attorney General of Texas

Mary F. Keller

First Assistant Attorney General

Renea Hicks*

Special Assistant Attorney General

Javier Guajardo

Assistant Attorney General

P.O. Box 12548, Capitol Station

Austin, Texas 78711-2548

(512) 463-2025

October 21,1988 Attorneys for Amici Curiae

* Attorney of Record

(.Additional Amici Curiae Counsel Listed in Appendix)

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE........................... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT........................... 2

ARGUMENT............................................................. 4

I . The 1982 Amendment to the Voting

Rights Act................................................... 4

II. The Shortcomings of the Chisom

Court's Analysis........................................ 6

A. The Plain Language......................... . .7

1. The Plain Meaning Rule................7

2. The Clear Statement Rule............11

3. The Statutory Amendment

Rule......................... ......... ......... 11

B . The Legislative History..................... 12

C. Senator Hatch's Comment.............. 14

D. Section 5 and Section 2 ........... 15

E . The Attorney General's Role.............16

III. Significant Protections Remain................17

CONCLUSION........................... 18

APPENDIX.............................................................A-l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

American Tobacco Co. v. Patterson,

456 U.S. 63 (1982)........................ ..12

Atascadero State Hospital v. Scanlon,

473 U.S. 234 (1 9 8 5 ) ........................ .......1 1

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms v.

Federal Labor Relations Authority,

464 U.S. 89 (1983)................ .16

Burns v. Alcala, 420 U.S. U.S. 575 (1975)....... 9

Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056

(5th Cir. .......................passim

Chisom v. Roemer, 853 F,2d 1186

(5th Cir. 1988).......................... . . . . . . . .2

Chrysler Corp. v. Brown, 441 U.S. 281

(1979) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1 4

City o f Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55

(1980) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .....................4 ,1 3 ,1 7

Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407 (1977)............ ..10

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986)........ .10

Forrester v. White, 108 S.Ct. 538 (1 9 8 8 ).......... 8

Haith v. Martin, 618 F.Supp. 410

(E.D.N.C. 1985), affd mem.,

106 S.Ct. 3268 (1986)................. ...13,15,17

Hatten v. Rains, 854 F.2d 687

(5th Cir. 1 9 8 8 ) .... . . . . . . . . . . . . . ....... 8

Holshouser v. Scott, 335 F.Supp. 928

(M.D.N.C. 1971), affd

409 U.S. 807 (1972) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Holtzman v. Schlesinger, 414 U.S. 1304

(1 9 7 3 ) .... . . . . . . . . . . . . ............... .....1 4

INS v. Cardoza Fonseca, 107 S.Ct. 1207

(1 9 8 7 ) .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ............ .7,9

Lake County v. Rollins, 130 U.S. 662

(1 8 8 9 ) .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ....... 1

Lane County v. Oregon, 7 Wall, 71 (1869)......... 1

Michigan v. Long, 463 U.S. 1032 (1983).......... 2

ii

Mitchum v. Foster, 407 U.S. 225 (1972)............ 11

Perrin v. United States, 444 U.S. 37 (1979)........ 7

Quern v. Jordan, 440 U.S. 332 (1979).................. 13

Regan v. Wald, 468 U.S. 222 (1984)...................15

Rodriguez v. United States, 107 S.Ct. 1391

(1987)................................................................. 10

Russello v. United States, 464 U.S. 16

(1983)....................................................... ......11

Securities Industry Ass'n v. Board of Governors

of the Federal Reserve System,

468 U.S. 137 (1984)................................ 16

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301

(1966).............................................................4,17

Thornburg v. Gingles, 106 S.Ct. 2752

(1986)................................................................5,6

Trainor v. Hernandez, 431 U.S. 434 (1977).......... 2

United States v. Board of Commissioners of

Sheffield, 435 U.S. 110 (1978).......................17

United States v. Dickerson, 310 U.S. 544

(1940)........................................................... ....11

United States v. Locke, 471 U.S. 84

(1985)................................................................. 14

Watt v. Alaska, 451 U.S. 259 (1981)......................7

Wells v. Edwards, 347 F.Supp. 453

(M.D. La. 1972), affd mem.,

409 U.S. 1095 (1973)........................................9

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973)......passim

Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971)................. 2

Statutes:

15 U.S.C. § 38 1 ....................................................... 8

29 U.S.C. § 152....................................................... 8

39 U.S.C. § 3005.................................................. 8

42 U.S.C. § 1973(a)..................................................5

42 U.S.C. § 1973(b)................................................ 5

45 U.S.C. § 151 ........................................................ 8

46 U.S.C. § 1244............................ 8

I l l

IV

Miscellaneous:

BLACK'S LAW DICTIONARY

(abridged 5th ed. 1983)............... 7

R. DICKERSON, THE INTERPRETATION AND

Application of Statutes (1975)............ 7

S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess., ...................9, 13

SUBCOMM. ON THE CONSTITUTION OF THE

Senate Comm, on the Judiciary, 97th

Cong., 2d sess., Report on the voting

rights act .. . . . . . . . ...... ..........13

Sup. Ct . r . 3 6 .4 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ............... ..........1

INTEREST OF AM ICI CURIAE

The Attorneys General of the amici curiae States of

Texas, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, and North

Carolina, see Appendix, sponsor this brief, pursuant to

Supreme Court Rule 36.4, to bring to the attention of the

Court an issue of significant and potentially disruptive

impact on state judiciaries.

In Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056, 1064 (5th Cir.

1988) ("Chisom”), the decision from which Louisiana

petitions for a writ of certiorari, the Fifth Circuit held that

section 2 of the Voting Rights Act "does apply to state

judicial elections." The Chisom decision casts a cloud of

uncertainty over the forty-two states that have either judicial

elections or judicial retention election systems. See

Louisiana's Petition For A Writ of Certiorari, at 10-11.

Already, at least six section 2 suits have been filed

challenging the judiciaries of Alabama, Georgia, Illinois,

Mississippi, and Texas. The Illinois suit encompasses 201

state judges, Louisiana's Petition, at 8-9, and a Texas suit,

206 judges.

Only a definitive statement from this Court determining

whether the Chisom principle is correct can remove the cloud

of uncertainty and permit the states to order their affairs

under clearly discernible governing legal principles. To

remove all doubt, the Court should grant certiorari and

decide whether the principle enunciated by the Chisom court

is correct. If the Court does not act, however, premature

remedies pursuant to Chisom could unnecessarily disrupt the

forums where the majority of this Nation's lawsuits are tried:

elected state trial courts.

Quick action also is necessary to maintain the delicate

balance in this important area of state-federal relations. State

governments, in our constitutional scheme, act as

independent political communities with the authority to make

important decisions of self-governance. See, e.g., Lane

County v. Oregon, 7 Wall. 71, 76 (1869). Perhaps no

incidents of state self-governance are more central to

concerns of federalism than the preservation of the integrity

2

of state law and the protection of the institutional autonomy

of state judiciaries. See, e.g., Michigan v. Long, 463 U.S.

1032 (1983); Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971). As

the Court has noted, "in a Union where both the States and

the Federal Government are sovereign entities, there are

basic concerns of federalism which counsel against

interference by federal courts, through injunctions or

otherwise, with legitimate state functions, p a rticu la rly

w ith the opera tion of s ta te courts." Trainor v.

Hernandez, 431 U.S. 434, 441 (1977) (emphasis added).

Indeed, the recent Fifth Circuit decision in Chisom v.

Roemer, 853 F.2d 1186, 1188-89 (5th Cir. 1988) ("Chisom

II"), illustrates the urgent need for this Court's action and

guidance. The Fifth Circuit in Chisom II vacated the district

court's preliminary injunction enjoining the election of a

justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court partly on the basis

that "the Supreme Court has yet to speak on the critical issue

whether section 2 of the Voting Rights Act applies to judicial

elections!,]" and because it did not want to unnecessarily

intrude upon an important area of state-federal relations such

as a "state's judicial process."

The issue presented here could fundamentally alter

state courts, a bedrock institution in our society of laws. A

decision now by the Court clarifying the reach of section 2 is

necessary to prevent undue interference with the operation of

state courts and to provide guidance to federal courts

struggling or soon to be struggling with Chisom-generated

questions.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The Chisom holding that judicial elections are

covered by section 2 of the Voting Rights Act sets in motion

events that soon will cascade into an avalanche of litigation

seeking to change the way state judiciaries are elected. The

litigation will be complex and time-consuming. It could

result in court-ordered reconfiguration of several states'

judicial systems and implementation of the novel concept of

electing judges from single member districts.

3

States need to know now from the Court whether

their current judicial election systems are going to be

measured by a results test in a vote dilution claim under the

Voting Rights Act. Only then will the states be able to

assess their election systems in the clear light of the law and

determine with some degree of certainty the proper response

to anticipated, threatened, or actual litigation. Some may

choose to reconfigure without a lawsuit or trial, while others

may choose to litigate the issue. All states, though, at least

will know the ultimate evidentiary standards and what proof

must be offered.

While there admittedly is no conflict in the circuits on

the Chisorn principle, the issue is too important and the state

judiciary too critical an institution for the Court to await

further judicial developments before settling the question. It

is a straightforward issue of statutory construction,

ultimately hinging on the meaning of a single word,

"representatives."

The Fifth Circuit's analysis was too facile to

definitively settle the question analytically, transgressing

elementary principles of statutory construction in reaching its

conclusion. The plain, commonly understood meaning of

"representatives" cannot be said to include judges. If

Congress had meant to take the major step of subjecting a

major state institution to new federal standards (as the Fifth

Circuit has now decided Congress did) surely there would

have been at least a modicum of debate on the matter. There

was none at all. Plain language aside, this Congressional

silence suggests that the thunderous step really was not taken

and, therefore, that the Fifth Circuit was wrong.

Before state judiciaries are subjected to major

alterations, before attorney fees mount, and before lengthy

trials begin, the states urge the Court to settle the controlling

legal principle and tell them the basic standard by which they

are to be judged.

4

ARGUM ENT

I . The 1982 A m endm ent to the Voting R ights

Act

Congress under the aegis of the Fifteenth Amendment

enacted the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (”1965 Act"), to

"banish the blight of racial discrimination in voting." South

Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 308 (1966). The

heart of the 1965 Act consisted of specific remedies to break

down the most commonly erected barriers that perpetuated

voting discrimination. Id. at 315-16 (discussing the impact

of sections 3, 4, 5, 6 ,1,9 , 12 and 13). Congress, tracking

the Fifteenth Amendment, enacted a general precatory

provision, section 2, which "broadly prohibited) the use of

voting rules to abridge exercise of the franchise on racial

grounds." Id. at 316.1

In City o f Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 60-61, 65

(1980) ("Bolden") the Court reasoned that section 2 of the

1965 Act "no more than elaborates upon . . . the Fifteenth

Amendment, and the sparse legislative history of section 2

makes clear that it was intended to have an effect no different

from that of the Fifteenth Amendment itself." It then held

that section 2 prohibits only intentional acts of discrimination

which deny or abridge the freedom to vote.

In response to Bolden, Congress amended section 2,

dividing it into two subsections. In subsection (a), it added

As originally enacted, section 2 of the 1965 Act provided that:

No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or

standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or

applied by any State or political subdivision to deny

or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States

to vote on account of race or color.

Voting Rights Act of 1965, Pub. L. No. 89-110, § 2, 79 Stat. 437

(codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 1973(a) (1982)).

5

a "results" test to the original section 2 language,2 and it

added new language as subsection (b), which states in

pertinent part:

(b) A violation of subsection (a) is

established if, based on the totality of

circumstances, it is shown that the political

processes leading to nomination or election in

the State or political subdivision are not

equally open to participation by members of a

class of citizens protected by subsection (a)

of this section in that its members have less

opportunity than other members of the

electorate to participate in the political process

and to elect representatives of their choice.

42 U.S.C. § 1973(b) (1982) (emphasis added).

Thus, through a clause in subsection (a) and the

introductory clause in subsection (b), Congress reinstituted a

"results test" similar to the one applied in White v. Regester,

412 U.S. 755 (1973) ("White"). Although the results test

removes the necessity of proving intent to establish a section

2 violation, its inclusion did not come without political

compromise. See Thornburg v. Gingles, 106 S.Ct. 2752,

2764 (1986) ("Gingles") (at-large elections are not per se

violations of section 2; vote dilution and lack of proportional

representation alone do not violate section 2; and the results

test does not assume the existence of racial bloc voting,

which must be proved).

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting

or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or

applied by any State or political subdivision in a

manner which results in a denial or abridgement of

the right of any citizen of the United States to vote

on account of race or color, or in contravention of the

guarantees set forth in section 4(f)(2), as provided in

subsection (b).

42 U.S.C. § 1973(a) (1982).

6

Congress, in the middle of subsection (b), attempted

to ensure that protected members of the electorate are able to

effectively participate in the political process, by electing

representatives of their choice. Inclusion of the modifying

phrase "representatives of their choice" is also the result of

compromise. Congress accepted the context in which

representatives was used by White (multi-member

legislative districts for the Texas House of Representatives)

and limited "representatives" to mean legislators. See infra

at pp. 9-10.

Section 2 is the culmination of the give-and-take of the

political process. Recognizing this, Congress admonished

the courts, when construing and applying it, to take "a

'functional' view of the political process, and to conduct a

searching and practical evaluation of reality." Gingies, 106

S.Ct. at 2775 (citations omitted). The reality here is that

judges are not representatives.

Determination of whether certiorari should be granted

turns solely on interpretation of the meaning of

"representatives" in the 1982 Act: Did Congress intend to

include elected state judges in the term "representatives?"

The answer is found in the interplay between the addition of

a results test and adoption of the limiting language from

White .

I I . The Shortcom ings of the Chisom C ourt's

A nalysis

The Chisom court, in concluding that section 2(b)

reaches elected state judges, employed a four-part analysis —

a plain language analysis, a legislative history analysis, a

comparative analysis of section 5 of the Voting Rights Act

with section 2, and an analysis which relied upon the

Attorney General's interpretation of section 2. At each

analytical juncture, the Chisom court took the wrong turn.

7

A . The Plain Language

Without much adornment, the Chisom court simply

observed that the " ' "plain meaning of [the language in

section 2] reaches all elections, including judicial elections"

and that the pre-existing coverage of section 2 was not

limited by the 1982 congressional amendments.' " Chisom,

839 F.2d at 1064 (brackets added by the court). Employing

ordinary tools of statutory analysis suggest a different

conclusion.

1 . The Plain Meaning Rule

"The starting point in every case involving construction

of a statute is the language itself." Watt v. Alaska, 451 U.S.

259, 265 (1981). If the words of a statute in their ordinary

and common usage "convey a definite meaning, which

involves no absurdity, . . . then that meaning . . . must be

accepted" as the expression of Congress' legislative

purpose. Lake County v. Rollins, 130 U.S. 662, 670

(1889). See INS v. Cardoza Fonseca, 107 S.Ct. 1207,

1213 (1987) ("Cardoza”) (legislative purpose is expressed

by the ordinary meaning of the words used); Perrin v.

United States, 444 U.S. 37, 42 (1979) ("[Ujnless otherwise

defined, words will be interpreted as taking their ordinary,

contemporary, common meaning.").

Reference to the lexicon is one way to establish plain

meaning. See R. DICKERSON, THE INTERPRETATION AND

A p p l ic a t io n o f S t a t u t e s , 231 (1975) ("D i c k e r s o n ”).

The lexicon contrasts, rather than equates, representatives

and judges. A representative is "a person chosen by the

people to represent their several interests in a legislative

body," but a judge is a person "who presides in some

court." BLACK'S LAW DICTIONARY 676 & 435 (abridged

5th ed. 1983). Individuals elected to the legislative branch

represent the people whereas individuals elected to the

judicial branch serve the people. Holshouser v. Scott, 335

F.Supp. 928 (M.D.N.C. 1971), aff'd, 409 U.S. 807

8

(1972). Congress itself, im plicitly recognizing the

representative-servant distinction, has never defined

representative to include a judge,3 but, consistent with

common parlance, has defined representative as a legislator.

See 46 U.S.C. § 1244 (representative is synonymous with

a member of Congress which includes delegates to the

House of Representatives from the District of Columbia,

Guam, and the Virgin Islands). In an unguarded moment,

the Fifth Circuit recently recognized, consistent with

common parlance, that judges are not representatives. See

Hatten v. Rains, 854 F.2d 687, 696 (5th Cir. 1988)

("Hatten") ("Judges, even if elected, do not serve a primarily

representative function."); Id. at 696 (Garwood, J., joined

by Jolly, J., specially concurring) (”[J]udges are not

representatives."). Such unguarded statements, of course,

speak volumes about the plain meaning of "representatives."

The difference between representatives and judges

perhaps explains why Congress did not apply the results test

of section 2 to elected judges. Representatives work as a

body in which every protected class should have

representation. The legitimacy of the work of a

representative body depends on its inclusiveness. Judges,

however, work alone to administer the law given them by

the representative branch. See Forrester v. White, 108 S.Ct.

538, 544 (1988) ("The decided cases, however, suggest an

intelligible distinction between judicial acts and the

administrative, legislative, or executive functions that judges

may on occasion be assigned by law to perform."). The

legitimacy of a judge's work comes from election by the

community as a whole and could be seriously undermined if

the judge were elected from a single constituency.

A second way to establish plain meaning is to review

the historical and cultural context of the language.

3 See, e.g„ 15 U.S.C. § 381 (representative is not an independent

contractor); 29 U.S.C. § 152 (representative means a person or labor

union); 39 U.S.C. § 3005 (representative means an agent or

representative acting as an individual); 45 U.S.C. § 151 (representative

means a person or labor union).

9

D IC K E R SO N at 1 0 5 -1 1 . Our national history treats a

representative differently than a judge. The distinction

between the representative and judicial branches — a

fundamental principle of both federal and state constitutional

law, typically expressed in the separation of powers doctrine

— is a permanent cornerstone of our national jurisprudential

ethos.

Wells v. Edwards, 347 F.Supp. 453, 454 (M.D. La.

1972), affd mem., 409 U.S. 1095 (1973) ("Wells”), which

held "that the concept of one-man, one-vote apportionment

does not apply" to the judiciary, distinguished legislators

from judges by focusing on the different governmental

functions performed by each.

M anifestly , judges . . . are not

representatives in the same sense as are

legislators or the executive. Their function is

to administer the law, not to espouse the

cause of a particular constituency.

Judges do not represent people they serve

people.

347 F.Supp. at 455. Congress' amendment of section 2 and

use of "representatives" was against this backdrop of

historical understanding.4

The term representative has an even more specific

historical context. Congress purposely borrowed section

2(b)'s language containing the term representative from

White v. Regester. See S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d

Sess. 32, reprinted in 1982 U.S. CODE CONG. & ADMIN.

NEWS 177, 210 ("In each case the courts looked to

4 The linguistic difference between representatives and judges is so

great that the two terms can neither be considered identical nor does one

include the other. Cf. Cardoza, 107 S.Ct. at 1213 ("The linguistic

difference between the words 'well founded fear' and 'clear probability'

may be as striking as that between a subjective and an objective frame

of reference . . ."). Cf. Burns v. Alcala, 420 U.S. 575, 580-81 (1975)

(dependent child does not include an unborn child because Congress used

the word child to refer to an individual already bom).

10

determine whether, in the words of both White [citation

omitted] and the present committee amendment of section 2,

the 'political processes' were 'equally open' and whether the

members of the minority group had the same 'opportunity'

as others in the electorate to 'participate in the political

processes and to elect representatives of their choice.' "),

(”S. Rep. 417").

In delineating the burden a plaintiff must sustain in

order to prove that a multi-member district invidiously

eliminates or minimizes the voting strength of protected

racial groups specifically, White referred to the legislative

branch:

The plaintiffs' burden is to [show] . . . "that

its members had less opportunity than did

other residents in the district to participate in

the political processes an d to elect

legislators of th e ir choice."

W hite, 412 U.S. at 766. Congress' transmutation of

White's "legislators" into section 2(b)'s "representatives" is

merely recognition that the two terms are synonymous and

used interchangeably. See Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S.

109, 123 (1986); Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407, 416

(1977).

Finally, any question about the plain-meaning of

statutory language is conclusively settled where Congress

knowingly borrows language that carries an established

judicial interpretation. See Rodriguez v. U.S,, 107 S.Ct.

1391, 1393 (1987) {"Rodriguez") (”[I]n passing the CCCA,

Congress acted — as it is presumed to act — with full

awareness of the well established judicial interpretation

. . .") (citations omitted). Congress' use of representatives,

with the understanding that they are legislators as defined by

White, directly supports the position that the plain meaning

of representatives excludes judges.

11

2 . The C lear Statem ent Rule

The clear statement doctrine, a second, equally

powerful rule of construction, also governs the reading of

section 2. This Court requires Congress, when passing

legislation that "alter[s] the relationship between the States

and the Nation,” to expressly state its intention in

unmistakable language in the statute itself. Mitchum v.

Foster, 407 U.S. 225, 242 (1972); see Atascadero State

Hospital v. Scanlon, 473 U.S. 234, 243 (1985) (Eleventh

Amendment context). A state’s sovereign interest in

maintaining the integrity of its judicial system by selecting

the method in which its judges will be chosen imposes on

Congress the obligation to expressly and clearly state in

unmistakable statutory language any intention to disrupt or

regulate a state's choice.

Congress failed to express a clearly conceived intent in

unmistakable language to alter the relationship between the

states and the federal government and disrupt the states’

choice in how their judges are chosen.

3 . The S tatu tory Am endm ent Rule

Analysis of the structure of the language of subsection

(b) also confirms that representatives do not include judges.

Different terminology in the amendment of an act "indicates

[congressional] intent to change the object of the legislation."

United States v. Dickerson, 310 U.S. 544, 561 (1940). Cf.

Russello v. United States, 464 U.S. 16, 23 (1983)

(" 'Where Congress includes particular language in one

section of a statute but omits it in another section of the same

Act, it is generally presumed that Congress acts intentionally

and purposely in the disparate inclusion or exclusion.' ").

Congress' addition of a "results test" (making it easier

for plaintiffs to prove a section 2 violation) along with the

addition of "representatives" from White (which specifically

referred to legislators) strongly indicates a change in the

12

manner in which section 2 operates to alleviate voting

discrimination.

The Chisom court failed to grasp that, as Congress

expanded the act to include a results test, it restricted the

class of officeholders to whom such a test would apply.

Ignoring the warning of Rodriguez, 107 S.Ct. at 1393, the

Chisom court erroneously "and most impermissibly relied on

its understanding of the broad purposes" of section 2

(safeguarding the voting rights of protected classes) to reach

its conclusion that section 2 applies to state judges.

Concurrently, other legislative considerations were at work,

ultim ately finding their em bodim ent in the term

"representatives." Thus, the Chisom court's reliance on

Congress' purpose in enacting section 2 in support of its

plain language analysis is not persuasive, especially in light

of section 2's language and its legislative history. See

Rodriguez, 107 S.Ct. at 1393 (omissions and brackets by

the Court) ("Where, as here, 'the language of a provision

. . . is sufficiently clear in its context and not at odds with

the legislative history,. . .' [there is no occasion] to examine

the additional considerations of 'policy' . . . that may have

influenced the lawmakers in their formulation of the

statute.").

B . The Legislative H istory

Once the plain-meaning of the language of a statute

settles the question of legislative intent, legislative history is

reviewed "to determine only whether there is 'clearly

expressed legislative intention' contrary to that language

which would require [a court] to question the strong

presumption that Congress expresses its intent through the

language it chooses." Cardoza, supra, 107 S.Ct. at 1213

n.12. The plain-meaning presumption is so strong that

"going behind the plain language of a statute in search of a

possibly contrary congressional intent is 'a step to be taken

cautiously' even under the best circumstances." American

Tobacco Co. v. Patterson, 456 U.S. 63, 75 (1982).

13

A review of the legislative history concerning the 1982

Act reveals four salient points, each of which casts doubt on

any congressional intent to apply section 2 to judges.

The 1982 Act was passed in response to Bolden,

which concerned elected policy makers who sit as a body.

The 1982 Act incorporated the standards and language of

White, including the definition of a representative as a

legislator. See supra pp. 9-10.

Section 5, which this Court has held to cover judicial

elections, see Haith, infra, at p. 15, and section 2 are

entirely different sections with entirely different purposes.^

Indeed, the distinctions become critical in light of the fact

that section 5 does not use the lim iting term

"representatives."

And finally, a review of the legislative history reveals

that, the overwhelming bulk of the discussion involving the

impact of section 2 never focused on whether the judiciary

was to be included in the amendment. Whether the judicially

untested idea that judges were to be covered by section 2

was a matter never seriously debated. Certainly, if Congress

intended such a major intrusion into previously untouched

state matters, "there would have been lengthy debate on this

point." Quern v. Jordan, 440 U.S. 332, 343 (1979). There

was no debate at all.

Nothing in the legislative history overcomes the plain

language presumption. When the plain language of an act

settles a question of statutory construction, as the plain

language of section 2 does here, and when "nothing in the

legislative history remotely suggests a congressional intent

contrary to Congress' chosen words, . . . any further steps

5 The subcommittee on the Constitution of the Senate Committee

on the Judiciary, after substantial debate on the differences between

section 2 and section 5, concluded that the omission from section 2 of

language used in section 5 was "conspicuous and telling." The

subcommittee, moreover, noted "the fact that Congress chose not to

utilize language in section 2 that it expressly used in sections 4 and 5

(i.e., ’effects') to be far more persuasive of original congressional intent

. . . SUBCOMM. ON THE CONSTITUTION OF THE SENATE COMM.

ON THE JUDICIARY, 97TH CONG., 2D SESS., REPORT ON THE VOTING

RIGHTS ACT 22 ,23 (Comm. Print 1982).

14

take the courts out of the realm of interpretation and place

them in the domain of legislation." United States v. Locke,

471 U.S. 84, 96 (1985). The court below, in interpreting

section 2 to encompass judicial elections, stepped into the

realm of legislation.

C . Senator H atch 's Com m ent

Senator Orrin Hatch, a leading opponent of the Act,

commented in the Senate Report that a political subdivision

"encompasses all governmental units, including city and

county councils, school boards, judicial districts, utility

districts, as well as state legislatures." Chisom, 839 F.2d at

1062 (citing S.Rep. 417) (emphasis by the court). The

Chisom court over-exerts itself and treats Senator Hatch's

comments as "persuasive evidence of congressional

understanding and belief that section 2 applies to the

judiciary." 839 F.2d at 1062. Giving such weight to so

fine-grained a reading of the statement of one Senate

opponent of a bill is outside even the expansive boundaries

of statutory interpretation.

If Senator Hatch's comment was sincere, he

misunderstood the words of the statute. Congress in

subsection (b) employed "political subdivision" in the

following manner: "The extent to which members of a

protected class have been elected to office in the state or

political subdivision is one circumstance which may be

considered . . . " Political subdivision directly modifies

"state," has no relation to "representatives," and relates to the

totality of circumstances in the newly enacted "results test."

Senator Hatch's comment should be given little or no

weight for two additional reasons. "The remarks of a single

legislator, even the sponsor, are not controlling in analyzing

legislative history," Chrysler Corp. v. Brown, 441 U.S.

281, 311 (1979), and "speeches by opponents of legislation

are entitled to relatively little weight in determining the

meaning of the Act in question." Holtzman v. Schlesinger,

414 U.S. 1304, 1312 (1973).

15

This Court has warned that the colloquies of witnesses

and even individual Congressman should seldom overcome

the plain-meaning of the language in a statute. Regan v.

Wald, 468 U.S. 222 (1984). Indeed, to allow the "clear

statutory language to be materially altered by such

colloquies, which often take place before the bill has

achieved its final form, would open the door to the

inadvertent, or perhaps even planned, undermining of the

language actually voted on by Congress and signed into law

by the President." Id. at 237. Giving weight to Senator

Hatch's comment undermines the enacted and signed

language of section 2.

D . Section 5 and Section 2

The Chisom court also mistakenly relies on Haith v.

Martin, 618 F.Supp. 410 (E.D. N.C. 1985), a ffd mem.,

106 S.Ct. 3268 (1986) {"Haith"). Haith held that the

preclearance requirement of section 5 of the Voting Rights

Act applies to judicial election systems. The Chisom court

misapplies Haith to support the proposition "that if section 5

applies to the judiciary, section 2 must also apply to the

judiciary." 839 F.2d at 1064. The Chisom court relied on

the "virtually identical" language defining the scope of

section 2 and section 5 to reach its conclusion. 839 F.2d at

1064. Section 5, however, reads:

No voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting, or standard, practice, or procedure

shall be imposed or applied by any State or

political subdivision to deny or abridge the

right of any citizen of the United States to

vote on account of race or color . . . .

The Chisom court's comparison fails. Section 5 does

not specifically, or even tacitly, condition its applicability to

election systems pertaining to representatives, as does

section 2. Section 5 offers no support for the Chisom

court's section 2 analysis.

16

E . The A ttorney G eneral's Role

The Chisom court also inappropriately relies on the

Attorney General's amicus curiae brief (in which he argued

that the plain meaning of section 2 reaches judicial elections)

as "persuasive evidence of the original congressional

understanding of the Act." 839 F.2d at 1064.

In doing so, the Fifth Circuit misreads United States v.

Board o f Commissioners o f Sheffield, 435 U.S. 110 (1978)

{"Sheffield"), thereby according the Attorney General

deference to which he is not entitled. In Sheffield, the Court

held that "in light of the extensive role . . . Attorney General

Katzenbach played in drafting the statute[,]" and his "key

role in the formulation of the [1965 Voting Rights] Act,"

great deference should be given to his interpretation of the

Act. Id. at 131-32. Attorney General Katzenbach was

instrumental in attaining passage of the Act and wholly

supportive of the purpose of the Act. Attorney General

Meese, and his Justice Department, however, did not play

any role in drafting the 1982 Act. Thus, there is no reason

to accord the Attorney General’s view special deference

here.

M oreover, "[a] review ing court 'm ust reject

administrative constructions of [a] statute . . . that are

inconsistent with the statutory mandate or that frustrate the

policy that Congress sought to implement.' " Securities

Industry Ass'n v. Board o f Governors o f the Federal

Reserve System, 468 U.S. 137, 143 (1984). Cf. Bureau of

Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms v. Federal Labor Relations

Authority, 464 U.S. 89, 97 (1983) ("[Djeference owed to an

expert tribunal cannot be allowed to slip into judicial inertia

which results in the unauthorized assumption by an agency

of major policy decisions made by Congress."). The

Chisom court's deference to the Attorney General's

construction was inappropriate because the Justice

Department did not play the role contemplated by Sheffield

and because the Attorney General's construction frustrates

Congress' intent.

17

I I I . S ignificant P ro tections Rem ain

Rejection of the Chisom court's holding would not

leave minority voters unprotected in their exercise of the

franchise, the fear of which may have silently crept into the

Fifth Circuit's analysis.

First, and most obviously, Congress could react to a

rejection by this Court of the Chisom holding just as surely

and quickly as it did to this Court's Bolden decision. Given

the earlier discussion about the need for Congress clearly to

express its legislative intent to intrude into traditional state

functions (such as judicial districting), see p. 11, supra,

Congress should have an opportunity to debate this

heretofore undebated issue. Such restraint seems a sound

jurisprudential response to the problem being brought to the

Court's attention.

Second, both the Constitution and the Voting Rights

Act continue to offer significant protections to minority

voters in connection with judicial elections. The Fifteenth

Amendment still prohibits intentional acts of official racial

discrimination against those seeking to exercise their

franchise in judicial elections. See Bolden. In the Chisom

case itself, for instance, proof of intentional discriminatory

acts in the establishment of the at large judicial district being

challenged still may succeed, notwithstanding this Court's

rejection of the application of the results test to such judicial

elections. The Voting Rights Act itself, as canvassed and

found constitutionally valid in Katzenbach, contains a host

of major protections for those seeking to exercise their

franchise when electing judges. These protections include

ballot access and, as held in Haith, supra, preclearance of

various electoral changes involving judicial elections.

The availability of these protections highlights the

extreme narrowness of the legal issue raised by Chisom. It

does not involve a constitutional issue; reversing the Fifth

Circuit would not permit intentional vote dilution in judicial

races; and minority voters would still be entitled to a host of

statutorily based ballot access protections. Whether

18

Congress in 1982 permitted the application of the results test

to minority vote dilution claims in judicial elections is the

only legal issue confronting the Court. It is a question in

need of a final answer.

C O N C LU SIO N

The Court need not await further developments and

possible conflicts in the inferior federal courts. The issue is

too straightforward to require it and too important to permit

it. Instead, the Court should issue the requested writ of

certiorari to settle this crucial issue.

Respectfully submitted,

Jim Mattox

Attorney General of Texas

Mary F. Keller

First Assistant Attorney General

Rene a Hicks*

Special Assistant Attorney General

Javier Guajardo

Assistant Attorney General

P.O. Box 12548, Capitol Station

Austin, Texas 78711-2548

(512) 463-2025

October 21,1988 Attorneys for Amici Curiae

* Attorney of Record

(Additional Counsel Listed in Appendix)

A-l

A PPEN D IX

ADDITIONAL COUNSEL FOR AMICI CURIAE

State of Arkansas

John Steven Clark

Attorney General of Arkansas

200 Tower Building

4th and Center Streets

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

(501) 682-2007

State of Florida

Robert A. Butterworth

Attorney General of Florida

The Capitol

Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1050

(904) 487-1963

State of Georgia

Michael J. Bowers

Attorney General of Georgia

132 State Judicial Building

Atlanta, Georgia 30334

(404) 656-4585

State of Illinois

Neil F. Hartigan

Attorney General of Illinois

100 West Randolph Street

Chicago, Illinois 60601

(312)917-2503

State of North Carolina

Lacy H. Thornburg

Attorney General of North Carolina

Department of Justice

P. O. Box 629

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

(919) 733-3377