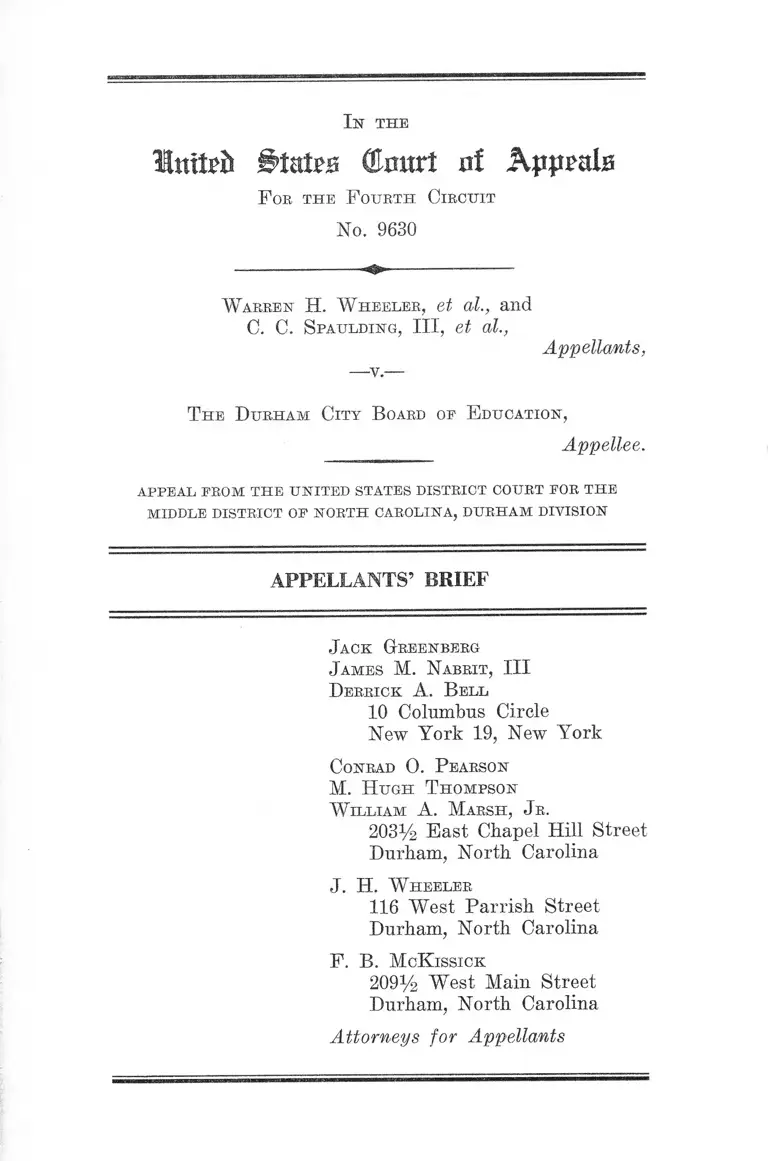

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education Appellants' Brief, 1964. 0d3be5fe-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b353256f-ffca-4dea-8c65-8250594abfb3/wheeler-v-durham-city-board-of-education-appellants-brief. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

UnlUb S>UU% (Erntrt nf ApjjpeIb

F ob th e F ourth C ircu it

No. 9630

W arren H . W h eeler , et al., and

C. C. S p a u l d i n g , III, et al.,

Appellants,

-v -

T h e D u rh a m C ity B oard of E ducation ,

Appellee.

APPEAL PROM TH E UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA, DURHAM DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

D errick A. B ell

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Conrad 0 . P earson

M . H u g h T hom pson

W illiam A. M arsh , Jr.

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

J. H. W heeler

116 West Parrish Street

Durham, North Carolina

F. B. M cK issick

209% West Main Street

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 1

Questions Involved....... ....................................................... 6

Statement of Facts ............................................................ 7

A r g u m e n t .............................................................................. 15

PAGE

I. The School Board Should Be Ordered to Re-

vise Its Racial Attendance Area Maps to Estab

lish a Non-racial Method for Initially Placing

Pupils ........................................................................ 15

II. The School Board’s Policy of Placing Teachers

on a Racial Basis in a Segregated Pattern

Violates Appellants’ Rights to Attend a Non-

discriminatory School System............................... 20

III. The Court Below Erred in Failing to Prohibit

the Planning of New School Facilities So As

to Promote Segregation ....................................... 24

C o n c l u s io n ............................................................................ 26

T able of Cases

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, Va., 321

F. 2d 494 (4th Cir. 1963) .............................................. 18

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County v. Brax

ton, 326 F. 2d 616 (5th Cir. 1964), cert, denied, 377

U. S. 924 (1964) .......................................................21, 23, 25

n

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, Va.,

317 F. 2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963) ....................................... 18

Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington County,

Va., 324 F. 2d 303 (4th Cir. 1963) ...............................17, 22

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 ....... 22, 23, 25

Buckner v. County School Board of Greene County,

Va., 332 F. 2d 452 (4th Cir. 1964) .............................18,19

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491

(5th Cir. 1962) ................................................................ 20

Calhoun v. Latimer, 321 F. 2d 302 (5th Cir. 1962), judg

ment vacated 377 U. S. 263 .......................................... 23

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ...........................................18, 24

Dillard v. School Board of City of Charlottesville,

308 F. 2d 920 (4th Cir. 1962) ....................................... 23

Dowell v. School Board of the Oklahoma City Public

Schools, 219 F. Supp. 427 (W. D. Okla. 1963) ........... 22

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, Dade County,

Fla., 272 F. 2d 763 (5th Cir. 1959) ............................. 20

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683 ...............18, 20, 23

Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, 304 F. 2d

118 (4th Cir. 1962) ........................................................ 18, 20

Jackson v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg,

321 F. 2d 230 (4th Cir. 1963)............ '.............................. 22

Jones v. School Board of Alexandria, Virginia, 278

F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) .................................................. 19

Manning v. Board of Public Instruction, 7 Race Rel. L.

Rep. 681 (S. D. Fla. 1962) ............................................. . 22

PAGE

Northcross v. Board of Education of City of Memphis,

302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962)..... .....................................

I l l

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of Mem

PAGE

phis, 333 F. 2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964) ........................... 21-22

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961) ....... 20

Taylor v. Board of Education of New Rochelle, 294 F

2d 36 (2nd Cir. 1961) ..... ................................................

Tillman v. Board of Public Instruction, 7 Race Rel. L

Rep. 687 (S. D. Fla. 1962) ............................................

Vick v. County Board of Education, 205 F. Supp.

436 (W. D. Tenn. 1962) .............................................. 25

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 196 F.

Supp. 71 ............................................................................ 2

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 309 F. 2d

630 (4th Cir. 1962) .......................................................... 2

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 326 F. 2d

759 (4th Cir. 1964) .........................................................3,17

17

22

Httiteir ©mart nf Kppmhz

F ob th e F ourth C ircuit

No. 9630

In t h e

W arren H . W h eeler , et al., and

C. C. S paulding , III, et al.,

-v.

Appellants,

T he D u rh a m C ity B oard oe E ducation ,

Appellee.

a p p e a l p r o m t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s d i s t r i c t c o u r t e o r t h e

MIDDLE DISTRICT OE NORTH CAROLINA, DURHAM DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Statement o f th e Case

This is the third time this case involving desegregation

of the public schools of Durham North Carolina has been

before this Court. This appeal is by the plaintiffs, Negro

school children and parents, from the District Court’s or

der of August 3, 1964, with respect to the school board’s

proposed plan for desegregation. The District Court in

part disapproved the proposed plan sustaining certain of

plaintiffs objections thereto, and ordered desegregation to

proceed in accord with the court’s own plan, but declined to

grant certain relief requested by the plaintiffs (113a).

2

Summary of Prior Proceedings

These consolidated actions were commenced in the Mid

dle District of North Carolina in 1960. On July 20, 1961,

the District Court filed an opinion (Wheeler v. Durham

City Board of Education, 196 F. Supp. 71) finding that the

Board operated a dual system of attendance areas based

on race, but refused to consider the case as a class action

and entered no injunction, although directing the board to

reconsider the school placements of certain plantiffs who

were found to have exhausted all administrative remedies.

Subsequently, in April 1962, the district court denied all

relief and dismissed the case, holding that plaintiffs were

not entitled to a general desegregation order for the school

system. This opinion is reported at 210 F. Supp. 839.

Plaintiffs appealed and this Court reversed, October 12,

1962, in Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 309

F. 2d 630. This Court’s opinion condemned the continued

use of dual attendance zones for initial assignments and

the discriminatory procedures for ruling on transfer appli

cations (309 F. 2d at 632-633).

The Court noted that it was not necessary to discuss “ the

instances, abundantly appearing in the record, of unfair

ness and arbitrariness in the procedures imposed upon ap

plicants for transfers to free themselves from the initial

racial assignments” (309 F. 2d at 633). On remand, pur

suant to this Court’s directions, the District Court entered

an order on January 2, 1963 which required that the named

plaintiffs be granted transfers as requested, contained an

injunction against certain discriminatory assignment prac

tices, and provided that the order remain in effect until a

satisfactory desegregation plan was presented and ap

proved.

In April 1963, the board proposed a desegregation plan;

plaintiffs objected to it on numerous grounds; and after a

hearing the trial court rejected the plan and ordered that

3

the school board grant pupils free transfers to desegre

gated schools upon request in grades 1-9 in September

1963. High school assignments remained as before during

the 1963-64 term, and the board was directed to present a

new plan for complete desegregation. The defendant

school board appealed this order, entered July 24, 1963. On

January 27, 1964 this Court affirmed the order as “ an ap

propriate interim decree.” Wheeler v. Durham City Board

of Education, 326 F. 2d 759, 760.

Proceedings Leading to This Appeal

The Durham City Board of Education filed a new plan

for desegregation on or about April 28, 1964 (la-8a) and

plaintiffs filed objections to it (9a-12a). The plan contains

lengthy and detailed provisions for the assignment of pu

pils. We have paraphrased and summarized some of the

basic features of the plan which provide for assignment of

pupils on the following basis:

(a) First grade pupils will be initially assigned in ac

cord with an attendance area map adopted by the Board.

They may obtain transfers out of their attendance areas

by applying within 15 days. Such transfers “ shall be

granted in the order received until the maximum capacity

per class room shall have been attained” (2a-3a).

(b) Other elementary pupils will be assigned to the

school which they are now attending (3a).

(c) Pupils assigned to an elementary or junior high

school outside their attendance areas may request to attend

the school in their areas, by applying for reassignment

during a 15-day period. Bequests shall be granted until

capacity is reached (3a-4a).

(d) Pupils completing elementary school shall be as

signed to junior high school in accord with a new attend

ance area map (4a).

4

(e) Pupils completing junior high school shall be as

signed to high schools under a feeder system by which

graduates of Brogden, Carr and Holton are assigned to

Durham High School and graduates of Whitted and Shep

ard are assigned to Hillside High School (4a-5a).

(f) Junior high school pupils were assigned to the

schools previously attended, except that Whitted pupils liv

ing in the area of the new Shepard school were assigned to

Shepard (5a).

(g) High School pupils were assigned to the school pre

viously attended (5a).

(h) Reassignment requests may be made within 15 days

after notification of initial assignment. Requests shall be

granted in the order received until class capacity is reached

(5a-6a).

Plaintiffs objected to the plan as inadequate and incom

plete on several grounds. Some of the objections were

that:

(a) The attendance area maps for initial assignments in

elementary and junior high schools were drawn on a racial

basis to segregate the races in the schools (9 a );

(b) the feeder system by which graduates of the all

Negro junior high schools are assigned to an all Negro high

school continues segregation (10a);

(c) the plan made no provision for placing teachers in

the schools on a nonracial basis to eleminate the segregated

pattern of such assignments (11a); and

(d) the plan made no provision for planning the size

and location of new schools without regard to race or for

revising existing plans prepared as a part of the segregated

system (11a).

5

The Court held a full evidentiary hearing on July 9,

1964. The parties filed suggested Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law and the Court heard oral arguments.

On August 3, 1964, the Court entered an order stating in

part (114a):

That the plan for desegregating the Durham City

Schools, including the amendment thereto, is disap

proved for the reason that the court is of the opinion

that the school zone boundaries, with respect to ele

mentary and junior high schools, in some instances

have been drawn along racial residential lines, rather

than along natural boundaries or the perimeters of

compact areas surrounding the particular schools.

The Court then ordered that desegregation proceed on

the following basis (114a-116a) :

(a) All pupils are to be initially assigned in accordance

with the school board’s plan.

(b) All pupils are to be notified of their free choice to

attend any school in the system. In the event of overcrowd

ing, the school board can, with the approval of the Court,

assign a child to the “ next nearest predominantly white

school” rather than to the school requested.

The order was to remain in effect unless some other plan

was presented to and approved by the Court. It provides

that if no other plan is approved by the end of the 1964-65

school term, or future terms, initial assignments are to

again be made in accordance with the school board’s plan

and pupils are to be given the same transfer rights (116a-

117a).

The Court refused to grant plaintiffs’ request with re

spect to teacher desegregation saying that consideration of

the request “ is deferred until after the close of the 1964-65

6

school term” (117a-118a). The board was directed to make

an administrative study of the problems involved and plain

tiffs were given leave to make another application for this

relief and directed to express themselves on the adminis

trative and legal problems involved including “ the standing

of the minor plaintiffs to question the policy employed by

the defendant Board” (id.).

The order denied injunctive relief with respect to the

size and location of new schools on the ground that “ these

are considerations for the defendant Board, and are rele

vant to this litigation only to the extent they have a bear

ing upon the good faith of the defendant in eliminating

discriminatory practices in the operation of the Durham

City School System” (118a).1

Plaintiffs filed Notice of Appeal on August 27, 1964.

Questions Involved

1. Whether, where the trial court finds that school chil

dren’s initial assignments are being made on the basis of

attendance area maps drawn on a racial basis, a desegrega

tion plan which allows the pupils thus placed relatively

free transfers to other schools is constitutionally adequate,

or whether plaintiffs were entitled to an order requiring

a revision of the racial attendance area maps to establish a

non-racial method for initially placing pupils in schools.

2. Whether the trial court erred in refusing to enjoin

the school board’s practice of assigning school personnel

on a racially segregated basis in a school segregation case,

1 An addendum to the order stated that more detailed findings

were not made because of the time element but invited Counsel to

request additional findings within five days. Plaintiffs’ counsel

wrote to the Court within this period making such a request, but

no additional findings have been filed.

7

where the plaintiffs have sought such relief for over four

years and the school authorities have no plans for changing

the practice and have continued to place large numbers of

new teachers on a segregated basis each year.

3. Whether the trial court erred by refusing to enjoin the

school board from planning the size and location of new

school facilities on a racial basis so as to promote segrega

tion, and refusing to order the board to plan new facilities

so as to promote desegregation, where the board has con

structed schools on a racial basis in the recent past, con

tinues to use racial attendance areas, and is now planning

a large construction program.

Statement o f Facts

The Durham public school system has about 15,400 pu

pils, including roughly 7,000 Negroes (88a). During the

1963-64 school year these pupils attended 19 elementary

schools, of which eight were all Negro schools,2 two were

all-white,3 and nine were predominantly white but attended

by a few Negroes.4 There were four junior high schools;

2 The all-Negro elementary schools are Burton, Crest Street,

Bast End, Fayetteville Street, Lyon Park, Pearson, Spaulding

and Walltown (27a).

3 The all-white elementary schools are Olub Boulevard and

Lakewood (26a; 28a).

4 The predominantly white elementary schools, and their 1963-64

enrollments were (26a; 28a) :

School Whites Negroes

Edgemont ___________ _ ________ 312 9

Fuller ______________ ________ 71 40

Holloway Street __________________ 407 37

Moorehead ___________ ___________ 323 51

North Durham ___________________ 294 16

E. K. Powe ______________ ________ 477 1

Y. E. Smith ____________ ________ 547 4

George Watts _________ ________ 391 8

8

one all-Negro school and three predominantly white schools

with a few Negro pupils.5 A new school with an all-Negro

enrollment, called Shepard Junior High, was scheduled

to be opened in September 1964. The two high schools

were Durham High (with 1,662 while pupils and 22 Ne

groes) and Hillside High (1,301 Negroes and no whites)

(26a-28a).

The district court found that the school zone boundaries

for elementary and junior high schools “ in some instances

have been drawn along racial residential lines, rather than

along natural boundaries or the perimeters of compact

areas surrounding the particular schools” 6 (114a). Among

the evidence on this matter were a number of maps, and

plastic map overlays, showing the location of the schools,

and the school attendance boundaries, as well as the Negro

residential areas in the city.7 There was also statistical

information indicating the number of Negro and white

pupils residing in the various areas. The overall pattern

was that the areas of the 14 predominantly white or all-

white schools had 7,944 white pupil residents and 455 Negro

pupil residents. The eleven all-Negro schools (including

the new Shepard School) had 7,316 Negro pupil residents

and 130 white pupil residents (of whom 54 were in one

school zone—East End).

5 The Junior High Schools and enrollments were (26a; 28a) :

School Whites Negroes

Brogden __________________________ 560 23

Carr _____________________________ 802 83

Holton ___________________________ 531 15

Whitted _______________________ 0 1,293

6 Note that the high schools have no attendance areas as such,

but as they received pupils from designated junior high schools

they do in effect have areas which are a combination of the junior

high areas. See Plaintiffs’ Exhibit D-l-64 (56a-57a).

7 Plaintiffs’ Exhibits C-64, C-l-64, C-2-64, C-3-64, D-64, D-l-64

and D-2-64. See stipulations at 37a-42a. See also 52a-57a.

9

The following facts illustrate the evidence indicated by

the exhibits and testimony on the school areas for each

level in the school system:

Elementary Schools

Four all-Negro elementary schools (Crest Street, Fay

etteville Street, Pearson and Spaulding) have no white

pupils living within the attendance area (31a). The Bur

ton and Walltown areas have two white pupils in each

zone; Lyon Park has 17; and East End has 54 (31a). Each

Negro elementary school in Durham serves substantially

the same Negro population as it served before desegrega

tion.

(a) The Crest Street School was built about eight or

nine years ago to replace a previously all-Negro school on

the site. Before desegregation it served the Negroes in the

neighborhood immediately adjacent to it. Now it serves

substantially the same population (76a-77a).

(b) The Walltown school was built in 1948 to serve the

Negroes living in the area adjacent to it (77a). Under the

new school zones only two white pupils reside in the area

(31a). The present attendance area embraces all the Ne

groes in the neighborhood near the Walltown School ex

cept those Negroes living on the west side of Sedgefield

Street which forms the western boundary of the area (Ex

hibit C-64).

(c) The Lyon Park School, built in 1928, served the

Negroes in the area adjacent to it prior to desegregation

(77a). The present attendance area includes about 514

Negro pupils and 17 white pupils and includes the entire

Negro neighborhood adjacent to Lyon Park School (Plain

tiffs’ Exhibit C-64).

(d) The East End School, built in 1928 and partially

rebuilt in 1963, has always been a Negro school serving the

10

Negro population in the area that surrounds the school

(78a-79a)„ The new East End area has 54 white pupils

and 724 Negro pupils (31a). The present East End attend

ance area embraces almost all of the Negroes residing in

the area around it, except about sixty Negro pupils in the

Holloway School area and seventy in the North Durham

area (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit C-64; 31a).

The eastern boundary of the East End attendance area

follows an erratic line, including several turns, and runs

very close to the Holloway School. East End is an over

crowded school surrounded by under-utilized white schools.

The estimated initial assignments for the East End School

for September 1964 total 836 pupils (54 white, 782 Negro)

and the capacity of the school is 720 pupils (32a-35a). The

estimated numbers of pupils initially assigned for Septem

ber 1964 at the North Durham, Holloway and Edgemont

Schools, which border on the East End attendance area,

are all less than capacity of those schools (id.). Holloway

Street School has a capacity of 510 with 426 pupils (398

white and 28 Negro) initially assigned for September 1964

(id.). North Durham has a capacity of 390 pupils with 312

pupils (294 white and 18 Negro) initially assigned (id).

Edgemont has a capacity of 450 with 363 pupils (353 white

and 10 Negro) initially assigned (id.). (The nearby Puller

School, previously attended by some of the pupils in this

neighborhood, will be used only for administrative pur

poses in the future.)

(e) Both the Spaulding and Pearson School areas em

brace entirely Negro residential blocks and no white pupils

reside in these areas (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit C-64; 31a). How

ever, large areas of both the Spaulding and W. G. Pearson

zones are closer to the predominantly white Moorehead

School than they are to the Spaulding and Pearson Schools,

and portions of the Moorehead School area, populated by

11

white families, are substantially closer to Spaulding than

to Moorehead (id.). The line separating the Spaulding area

from the Moorehead area follows the street which divides

the Negro and white neighborhoods (id.). The same is true

with respect to the eastern boundary of the Fayetteville

Street attendance area which includes all the Negro resi

dential areas but does not include any white pupils within

its boundaries (id.). The superintendent testified that the

boundaries between all-Negro Spaulding and Pearson Ele

mentary Schools has been changed “ just about every year”

(Tr. 98).

The northeastern boundary of the W. G. Pearson and

Burton Schools follows the Seaboard railroad tracks which

separates the Negro and white neighborhoods (except for

a small group of Negroes living on both sides of the tracks

in the area between the white Smith and Burton Schools).

The Seaboard railroad tracks cut across and divide parts

of the attendance areas for two predominantly white

schools, George Watts and Southside. Similarly, other rail

road tracks and main arteries cut across elementary school

zones- in the city. That is, pupils on both sides of such

arteries attend the same school. Other examples are the

Club Boulevard area, divided by a major highway; the

North Durham area, divided by two railroad lines going in

different directions; and the East End and Edgemont

areas, divided by railroad lines.

The Superintendent of Schools testified, when questioned

by the court with respect to the boundaries between the

Spaulding and Moorehead schools:

Well, it wasn’t a matter of getting them to the closest

school, entirely, Your Honor. It ’s a matter of chang

ing these lines as little as possible from year to year

back through the years. I think this has been true

12

many years ago, that you change the lines as little as

possible in order that the child might continue his edu

cation in the same school he was in (Tr. 96).

Under further questioning by the court as to whether or

not “ this system honestly eliminated color consideration

from the entire Durham School system,” the superin

tendent replied, “ I don’t know the answer to that” (98a).

Junior High Schools

The junior high school attendance areas adopted for the

all-Negro Whitted Junior High School and the new Shep

ard Junior High School scheduled to open in September 1964,

include almost all of the Negro junior high school pupils

in the city (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit C-64). The Whitted area

includes 1,085 Negro pupils and 28 white pupils (31a).

The Shepard area includes 580 Negro pupils and no white

pupils (id.). The other three areas include small numbers

of Negro pupils: Brogden 14, Carr 59, and Holton 38 (id.).

Generally, these junior high school lines follow the divid

ing lines between the Negro and white neighborhoods ex

cept that small portions of the Negro neighborhoods are

zoned into the Carr and Holton Schools (Plaintiffs’ Ex

hibit D-64).

High Schools

The proposed feeder system for high school assignments

would result in the initial assignment of all graduates of

the two all-Negro junior high schools, Whitted and Shep

ard, to the all-Negro high school, Hillside High School.

The graduates of the other three junior high schools which

are predominantly white, would be assigned to the pre

dominantly white Durham High School. White pupils in

the Holton school area will travel across the Whitted

13

School area to reach Durham High School (Plaintiffs’ Ex

hibit D-l-64).

All teachers and other professional personnel in the ten

schools with all-Negro student bodies are Negroes and all

such personnel in the other fifteen schools are white (29a).

No white pupils have attended any of the schools with

Negro teachers. The school authorities have no plans for

ending teacher segregation (105a). During the past five

years, from 81 to 111 new teaching personnel were em

ployed in the public schools each year (30a). The School

Board has continued to assign Negro teachers to the

Negro schools and white teachers to the schools attended

by white pupils under the pattern that existed before

there was any desegregation.

At the time of trial no faculty had been assigned to

the Shepard Junior High School which was scheduled to

open in September 1964. About 567 Negro pupils and no

white pupils were initially assigned to this school (34a).

The proposed desegregation plan does not include any

statement with respect to locating new schools and addi

tions to schools in such a way as to promote desegregation

or indicate any change of the past practices of locating

schools and planning their size on a racial basis. The su

perintendent said that had not been discussed (73a). The

superintendent acknowledged that the size and location of a

school were factors which determined the area it would

serve (ibid.).

The voters of the community recently approved a $3.5

million bond issue for school construction and renovations

(67a). The superintendent testified that only one new

school site had been selected and that none of the proposed

new schools or additions had been formally approved.

The superintendent mentioned, and an exhibit (Plaintiffs’

14

Exhibit E-64) explained, a number of specific construction

projects which are being considered (67a-72a).

The School Board has taken action to close the Fuller

School which had 40 Negro and 71 white pupils during

the 1963-64 term (26a; 28a) and has reassigned almost all

of the Negro pupils who attended this school during the

past year to the all-Negro East End School. The Board

planned to open a new junior high school, Shepard, which

it has located in the heart of an all-Negro neighborhood

and to which it has assigned 567 Negro and no white pupils

for September 1964 (34a-35a). The school’s capacity is

510 pupils and the superintendent indicated he was already

considering enlarging the school (32a; 70a).

15

A R G U M E N T

I.

The School Board Should Be Ordered to Revise Its

Racial Attendance Area Maps to Establish a Non-racial

Method fo r Initially Placing Pupils.

The trial, court found, with ample support in the record,

that the initial placement of pupils in the school system,

including children entering school for the first time and

those being promoted from one level to another, was made

on the basis of attendance area maps drawn on racial lines.

The lines effectively separate the Negro and white resi

dential neighborhoods without regard for more natural

boundaries and the capacity of school buildings. The zones

were drawn in many cases to encompass the same Negro

neighborhoods served by the all-Negro schools before there

was any desegregation in the school system. All this

abundantly appears from the evidence which has been de

scribed in the statement of facts above.

The principal issue here is what must be done to rectify

this situation. The trial court, while stating its disapproval

of the proposed plan, ordered a plan which modified the

school board’s proposal only slightly. The court’s order

allows initial assignments to be made during the current

year, and future years, on the basis of the school board’s

plan and maps. The court’s modification was to slightly

liberalize the transfer rules and procedures. The school

board proposed to grant all transfer requests so long as

there was no overcrowding as determined by a particular

set of standards. The court adopted this same principle,

16

but altered the time limits for applications and provided

a more general statement concerning overcrowding with an

opportunity for the parties to apply to the court for ap

proval of alternate arrangements in the event overcrowd

ing prevented all transfers from being freely granted.

Appellants’ position is that the continuation of initial as

signments on a racial basis promotes continued segregation,

and that this cannot be justified by the fact that transfers

are, or may be, relatively freely available. Appellants

have no objection to a system of initial placements based

on fair and non-racial attendance areas coupled with a

free transfer policy.

There is ample precedent to sustain the proposition that

school assignments based upon race should be enjoined.

Indeed, in this very case, on the first appeal, when this

Court condemned the practice of separate dual racial

school zones for Negroes and whites, it stated that:

It is an unconstitutional administration of the North

Carolina Pupil Enrollment Act to assign pupils to

schools according to racial factors (309 F. 2d at 633).

This Court ordered an injunction “ against the continuance

of the board’s discriminatory practices” (Id.). We submit

that pupils are just as much assigned “ according to racial

factors” when they are placed under racially gerry

mandered school zones as they are when placed under

separate maps for whites and Negroes. Actually paragraph

3 of the order entered in this case on January 2, 1963

(which remains in effect as pointed out in the addendum

to the order of August 3, 1964) explicitly condemns “ any

method of determining the placement of pupils in schools

on the basis of racial considerations”, and might be thought

to settle the matter if the trial court had not now approved

17

the continued use of zones found by the court to be “ drawn

along racial residential lines” .8

In Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington County,

Va., 324 F. 2d 303, 308 (4th Cir. 1963) this Court held that

the “ transition from segregation to desegregation is not

yet finished” where school zones originally established

to maintain segregation were largely unchanged. Cf. Tay

lor v. Board of Education of New Rochelle, 294 F. 2d 36

(2nd Cir. 1961), where the court condemned gerrymander

ing of school zone lines. The illegality of the continued

racial feeder system for assigning all graduates of the Negro

8 The full text of the order of January 2, 1963 is set out at pages

24-27 of the appendix to Appellants’ Brief on the last appeal to

this Court. Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 326 F. 2d

759 (4th Cir. 1964; No. 9184). Paragraph No. 3 of that order pro

vides as follows:

3. It is further Ordered that the defendants, their agents,

servants and employees are restrained and enjoined from any

and all acts that regulate or affect the assignment of pupils

to any public schools under their supervision, management

or control on the basis of race or color. The defendants are

specifically restrained and enjoined from (a) using any meth

od of determining the placement of pupils in schools on the

basis of racial considerations when pupils first enter the

school system, when pupils are promoted from elementary

school to junior high school, or from junior high school to

high school, or when pupils change their residences from one

part of the area served by the school system to another part

of the school system’s area; (b) using any separate racial

attendance area maps or zones or their equivalent in determin

ing the placement of pupils in schools; (c) from requiring

any applicants for transfers to submit to any futile, burden

some, or discriminatory administrative procedures in order to

obtain such transfers, including (but not limited to) the use

of any criteria or standards for determining such requests

which are not generally and uniformly used in assigning all

pupils, and the requirement of administrative hearings or

other procedures not uniformly applied in assigning pupils;

and (d) using any standards relating to residence, academic

achievement, overcrowding or otherwise in determining such

transfer requests which are not used in determining initial

assignments of all pupils.

18

junior high schools to the all-Negro high school, and all

graduates of the predominantly white junior high schools

to the predominantly white high school, is equally obvious

in the light of such precedents as Green v. School Board of

City of Roanoke, 304 F. 2d 118, 120, 123 (4th Cir. 1962),

and Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, Va.,

317 F. 2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963).

This Court has emphatically pointed out that it is the

duty of school boards to take steps to eliminate the system

of segregation created by the states. Bell v. School Board of

Powhatan County, Va., 321 F. 2d 494, 499 (4th Cir. 1963);

Buckner v. County School Board of Greene County, Va.,

332 F. 2d 452, 454 (4th Cir. 1964); cf. Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U. S. 1, 7.

In Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683, 688, the

Supreme Court, in condemning racial transfer procedures,

made plain its assumption that initial placements based on

race violated the Constitution, stating:

The recognition of race as an absolute criterion for

granting transfers which operate only in the direction

of schools in which the transferee’s race is in the ma

jority is no less unconstitutional than its use for origi

nal admission or subsequent assignment to public

schools. (Emphasis added.)

Indeed this court’s recent decision pertaining to initial

racial assignments made by dual school zones in the Buck

ner case, supra, obviously applies with equal force to initial

racial assignments made by gerrymandered zones. As

stated in Buckner, supra at 454:

By initially assigning Negro pupils to segregated

schools and then permitting them, only upon applica

tion to the Pupil Placement Board, to transfer out of

19

these segregated schools, the School Board has in. effect

formulated a plan which will require each and every

Negro student individually to take the initiative in

seeking desegregation. Naturally, as we have noted in

Jones v. School Board of Alexandria, Virginia, 278 F.

2d 72, 77 (4th Cir. 1960), because of the existing racial

pattern, in most cases “ it will be the Negro children,

primarily, who seek transfers.”

And later the court said:

If, as alleged in the complaint, students were ini

tially being assigned to schools in a racially discrimina

tory manner, “ the School Board is actively engaged in

perpetuating segregation” (332 F. 2d at 455).

The Buchner case reasoning is precisely in point. Obvi

ously, the Durham Board does encourage segregation by

using gerrymandered school zones with the result that the

vast majority of students of both races are initially as

signed to schools on a basis which substantially perpetuates

the segregated pattern. This system places all the weight

of the governmental action on the side of the segregated

pattern and leaves it to individual Negro students to at

tempt to desegregate the school system one-bv-one. And, of

course, the zoning pattern which places only a small handful

of white children in the zones of the traditional all-Negro

schools, virtually insures that these children will, because

they are in a tiny minority, be encouraged by that circum

stance to transfer out of their zones to predominantly

white schools in other neighborhoods. This has in fact

occurred in every such case.

The invalidity of the system is clear from the settled

precedents. Appellants’ argument does not rest on the

theory that the board is required to assign pupils so as

20

to achieve any particular racial proportions in the popula

tion of any school. The argument made is that the school

board does have an obligation to promote the elimina

tion of the segregated system that it has created by in

stituting a truly non-racial assignment system. And this

argument is supported by a multitude of precedents con

demning racial methods of assigning pupils. See, for ex

ample, Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961);

Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke, 304 F. 2d

118 (4th Cir. 1962); Northcross v. Board of Education of

City of Memphis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962); Bush v.

Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491 (5th Cir. 1962);

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683.

II.

The School Board’s Policy of Placing Teachers oil a

Racial Basis in a Segregated Pattern Violates Appel

lants’ Rights to Attend a Nondiscriminatory School

System.

Segregation of teachers in public schools was and is an

integral part of the segregated public school systems

created by law. This proposition, which is surely self evi

dent to anyone even slightly familiar with segregated

school systems, is illustrated in a small, almost incidental,

manner by Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, Dade

County, Fla., 272 F. 2d 763 (5tli Cir. 1959). In that case the

school board, disclaiming discrimination, denied that one

of its publications listing schools as “ Negro” and “ White”

referred to pupils saying it meant only the personnel.

With manifest understatement, Judge Rives wrote that:

“ The distinction is not very meaningful so long as the

schools having all Negro teachers also have all Negro

pupils, and no other schools have any Negro teachers or

pupils” (272 F. 2d at 766).

21

The Durham school system continues the policy of the

segregation era by assigning only Negro teachers to work

in the all-Negro schools and only white teachers to work

in the schools attended by white pupils. The Board ad

mittedly has no plans to change this practice, although

the complaints filed in these consolidated cases in 1960 de

manded an end to teacher segregation, and plaintiffs re

iterated their protests about teacher segregation in 1963

and 1964 in objecting to two proposed desegregation plans

which made no mention of the subject.

The North Carolina State Department of Public In

struction allots the number of teaching positions for the

Durham system on a racial basis, and the Durham authori

ties who determine the actual hiring and placement of

teachers do this on a racial basis (62a-63a). The record

indicates the substantial numbers of new teaching em

ployees who have been hired during the past five years

(30a), and all have been placed in schools on a segregated

basis (29a). 455 new teachers were hired between 1959 and

1963 (30a). There were a total of 640 teachers in the sys

tem (29a). Thus, the pattern of segregation which pre

vails is largely the product of the continuing practice

of assigning new employees to schools on a racial basis.

The trial court apparently rested its refusal to rule

upon the matter of teacher desegregation on doubts as to

the standing of pupils to litigate this issue, since its order

asked that this issue be briefed again if the plaintiffs de

mand was renewed in 1965 (117a-118a). We submit that

both the Fifth and Sixth Circuits have quite correctly

held that teacher segregation is an aspect of a segregated

school system which can be corrected upon the complaint

of pupils and parents. Board of Public Instruction of

Duval County v. Braxton, 326 F. 2d 616, 620 (5th Cir.

1964), cert, denied, 377 IT. S. 924 (1964); Northcross v.

22

Board of Education of the City of Memphis, 333 F. 2d 661

(6th Cir. 1964).9

Furthermore, this Court has held that a complaint

broadly seeking a transition to a racially nondiscrimina-

tory school system was sufficient to bring before the court

the issue of faculty desegregation. Jackson y. School

Board of the City of Lynchburg, 321 F. 2d 230 (4th Cir.

1963). This was, at the least, an implied ruling that teacher

desegregation issues were properly a part of such cases,

for unless this was so the ruling would have been a mere

academic exercise.10

Certainly, there was nothing in the evidence to indicate

that the school board had any administrative problems in

connection with teacher desegregation which justified a

postponement under the principles of Brown v. Board of

Education, 349 U. 8. 294. The school board has never for

mally considered the matter. The trial court’s order can

not be supported by an assumption that a postponement

was within equitable discretion absent any showing of

justification for delay. This is particularly the case where

litigation has been as prolonged as it has in Durham, and

where segregation results not merely from inertia but also

from the continuing policy of the board in placing large

numbers of new teachers each year. Even an order directed

only at nondiscrimination in placing new employees would

soon substantially change the pattern, given the large

teacher turnover in Durham.

9 District court opinions to the same effect are: Dowell v. School

Board of the Oklahoma City Public Schools, 219 F. Supp. 427

(W. D. Okla. 1963) ; Tillman v. Board of Public Instruction, 7 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 687 (S. D. Fla. 1962) ; and see Manning v. Board of

Public Instruction, 7 Race Rel. L. Rep. 681 (S. D. Fla. 1962).

10 Note also that, in Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington

County, Va., 324 F. 2d 303, 306 (4th Cir. 1963) the court took occa

sion to commend the board for its announcement of nondiserim-

inatory personnel policies, urged by the board as evidence of its

completion of the transition period.

While the trial court did direct the school authorities to

study the matter during the present school year, the Court

did not direct the board to prepare a plan for teacher de

segregation as was done in the Braxton case, supra. Appel

lants are aware that several courts have approved post

ponement of the teacher desegregation issue. See, for

example, Calhoun v. Latimer, 321 F. 2d 302, 311 (5th Cir.

1962), judgment vacated 377 IT. S. 263. But appellants

urge that postponement of constitutional rights in this

matter as in others must be justified by appropriate equi

table considerations, and that the Board seeking any delay

bears the burden of justifying it. Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 349 U. S. 294.

Finally, it should be mentioned that the matter of teacher

desegregation has an important bearing upon the desegre

gation of pupils in the schools. This is patent in a school

system where pupils have a degree of choice with respect

to which school they will attend. Obviously, parents regard

a school’s teaching staff as important in appraising the

desirability of a school. In a practical view of a school

system which has long been segregated, and is just begin

ning desegregation, it is obvious that the existence of all-

white and all-Negro faculties will encourage many parents

to choose schools on the basis of the race of the teachers,

and will thus foster continued segregation of pupils. There

is no reason to believe that this is not at least as important

a factor influencing choices as the race of pupils’ classmates,

which was exploited by transfer plans like those condemned

in Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683, and Dillard

v. School Board of City of Charlottesville, 308 F. 2d 920

(4th Cir. 1962). Indeed, the mere fact that the school au

thorities think the matter of a teacher’s race important

enough to require a uniform segregationist practice, un

doubtedly influences parents to place some value on it.

23

24

This flies in the face of the basic constitutional requirement

that public school systems work to eliminate segregation.

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 7.

III.

The Court Below Erred in Failing to Prohibit the

Planning of New School Facilities So As to Promote

Segregation.

It is elementary that one of the principal factors nor

mally influencing the pupils who will attend a given school

is the size and location of the school with reference to

the pupils’ residences (73a). It is commonplace for schools

to be constructed in order to serve a particular area. This

matter is important even in the context of a free choice

system, for obviously school accessibility will influence

choice. In the present case the Superintendent testified that

the matter of locating schools in order to promote de

segregation had not been discussed (73a). But this school

board has long constructed schools on a racial basis to

serve the Negro populations in particular areas. This was

acknowledged in the case of such elementary schools as

Crest Street, Walltown and Lyon Park (76a-77a), and is

obvious enough in the case of the Shepard Junior High

School which opened for the first time in 1964 as an all-

Negro school. The board is now beginning a 3y2 million

dollar expansion, but its plans have not been finalized. This

is a perfect opportunity for planning to promote either

segregation or desegregation.

Actually, this issue is no different from that involved in

drawing school zone lines on a racial basis, except that a

segregated or desegregated result can even more effectively

be achieved by the location of schools than it can by draw

ing zone lines. Zones can readily be changed, but once

schools are constructed they cannot be moved.

25

Since this school board has for years engaged in a series

of sophisticated segregationist schemes, amply revealed

in the record of the first appeal in this case, one would be

exceedingly credulous to accept their unsupported asser

tions that they have no plan to build schools so as to pro

mote segregation. But their vague and general disclaimer

of segregationist intentions is coupled in this case with the

school board’s present practice of using gerrymandered

school zone lines adopted only this year.

This is surely an appropriate matter for considera

tion by the courts. The importance of such matters to

school desegregation is demonstrated by the reference in

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, to “ problems

arising from the physical condition of the school plant” (at

300-301). The Fifth Circuit recently approved a District

Court order, attacked by a school board, which required

among other things that a desegregation plan must pro

vide that construction programs not be designed to per

petuate, maintain and support segregation. Board of Pub

lic Instruction of Duval County v. Braxton, 326 F. 2d 616,

620 (5th Cir. 1964). Cf. Vick v. County Board of Educa

tion, 205 F. Supp. 436, 441 (W. D. Tenn. 1962) (financing

and budgeting not to be based on race or color). Plaintiffs

submit that such an order should appropriately go one

step further and direct the school authorities to take all

reasonable steps available to them in the preparation of

their plans for locating new schools (consistent with the

other demands of school planning, such as availability of

funds, size of sites, etc.) to promote the desegregation of

the system. This is the only manner in which the school

board can undo some of the long term effects of the years

of planning schools’ sizes and locations on a segregated

basis.

The court might appropriately direct the school board

to report to it the precise nature of its plans for new con

26

struction as they are developed, presenting a statement of

the probable effect of such construction on the desegrega

tion process, as evidenced by such matters as the probable

areas to be served by the schools. But, certainly, even a

general admonition to the school board to perform its plan

ning in light of the general principles indicated would be

vastly preferable to the ruling of the court below indicat

ing that this matter was not relevant to the litigation.

CONCLUSION

W herefore, f o r all the fo re g o in g reasons, appellants

resp ectfu lly subm it that the ju dgm en t below should be

reversed .

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

J ames M. N abrit , III

D errick A. B ell , J r .

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Conrad 0 . P earson

M . H u gh T hom pson

W illiam A. M arsh , Jr.

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

P . B . M cK issick

209% West Main Street

Durham, North Carolina

J . H . W heeler

116 West Parrish Street

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for Appellants

38