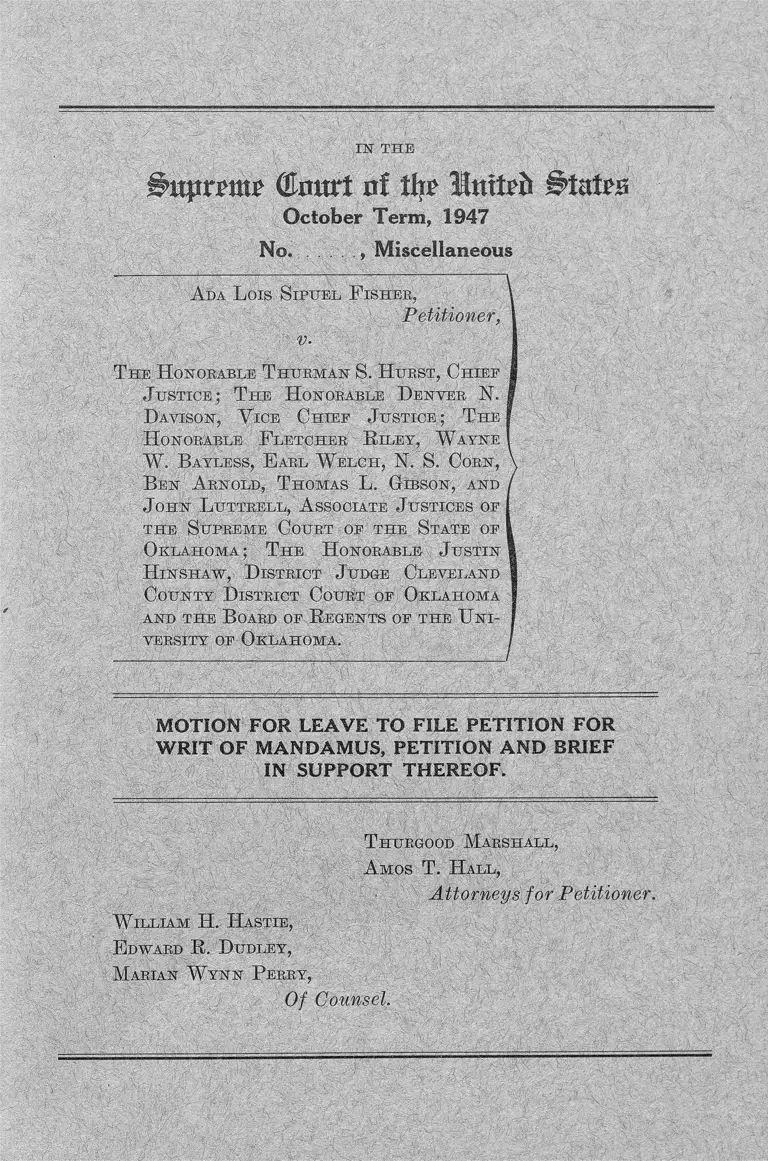

Fisher v. Hurst Motion for Leave to File Petition for Writ of Mandamus, Petition and Brief in Support Thereof

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1948

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Fisher v. Hurst Motion for Leave to File Petition for Writ of Mandamus, Petition and Brief in Support Thereof, 1948. c3aacdde-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b362eb69-81e2-48d9-af1a-2b18dd6053f2/fisher-v-hurst-motion-for-leave-to-file-petition-for-writ-of-mandamus-petition-and-brief-in-support-thereof. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN T H E

flkrurt of % Unite!* 0iateH

October Term, 1947

No. , Miscellaneous

A da L ois S ip u e l F is ii e u,

Petitioner,

T h e H o n o r able T h u r m a n S . H u r s t , C h ie f

J u s t i c e ; T h e H o n o r able D e n v e r N .

D a v is o n , V ic e C h ie f J u s t i c e ; T h e

H o n o r able F l e t c h e r R i l e y , W a y n e

W . B a y l e s s , E a r l W e l c h , N . S . C o r n ,

B e n A r n o ld , T h o m a s L. H ib s o n , a n d

J o h n L u t t r e l l , A sso ciate J u s t ic e s of

t h e S u p r e m e C o u r t of t h e S t a t e of

O k l a h o m a ; T h e H o n o r a b le J u s t in

H in s h a w , D is t r ic t J udge C l e v e l a n d

C o u n t y D is t r ic t C o u r t of O k l a h o m a

a n d t h e B oard of R e g e n t s of t h e U n i

v e r s it y of O k l a h o m a .

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE PETITION FOR

WRIT OF MANDAMUS, PETITION AND BRIEF

IN SUPPORT THEREOF.

T hurgood M a r s h a l l ,

A m o s T . H a l l ,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

W il l ia m H . H a s t ie ,

E dw ard R . D u d l e y ,

M a r ia n W y n n P e r r y ,

Of Counsel.

I N D E X

PAGE

Motion for Leave to File Petition for Writ of Mandamus 1

Brief in Support of Motion and Petition ____________ 13

Argument:

I—The Supreme Court of Oklahoma and the Dis

trict Court of Cleveland County have violated

the mandate of this Court ___________________ 14

II—Mandamus is the appropriate remedy in this

case _____________ 19

Mandamus Will Always Lie to Compel Obedi

ence to a Mandate of This Court_______ __ 19

Conclusion ___________________________________________ 21

Exhibit A _____________________ 23

Exhibit B ._________________________________ __-..... ...._ 28

Table of Cases Cited

Ex Parte Sibbald, 12 U. S. 488 ____________ ________ _ 20

Ex Parte Texas, 315 U. S. 8 _________________________ 20

Ex Parte Union Steamboat Co., 178 U. S. 317_________ 20

Federal Communications Commission v. Pottsville, 309

U. S. 134 _______________ 1_______________________ 20

In re Potts, 166 U. S. 263 __________________________ 20

In re Sanford Fork and Tool Co., 160 U. S. 247 ... _ 20

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 ______ 16

U. S. v. Fossatt, 21 How. 445 ____________________ _._..19, 20

11

Table o f Authorities Cited

PAGE

American Teachers Association, The Black and White

of Rejections for Military Service, August, 1944____ 17

Ballantine, The Place in Legal Education of Evening &

Correspondence Law Schools, 4 Am. Law School

Rev. 369 (1918) __________________________________ 16

Boyer, Smaller Law Schools: Factors Affecting Their

Methods and Objectives, 20 Oregon Law Rev. 281

(1941) ____________________________________________ 16

Klineberg, Negro Intelligence and Selective Migration,

New York, 1935 _____ 17

McCormick, The Place and Future of the State Uni

versity Law School, 24 N. C. L. Rev. 441__________ 17

Peterson & Lanier, “ Studies in the Comparative Abili

ties of Whites and Negroes,” Mental Measurement

Monograph _____________________ 1________________ 17

Simpson, The Function of a University Law School, 49

Harv. L. Rev. 1068 _______________ ____________ j_ 17

Stone, The Public Influence of the Bar, 48 Harv. L.

Rev. 1 ____________________________________________ 17

Townes, Organisation and Operation of a Law School,

2 Am. Law School Rev. 436 (1910) ________________ 16

1ST T H E

Supreme (tart of tlir MnlUh

October Term, 1947

No. , Miscellaneous

A da L ois S ip u e l F is h e r ,

Petitioner,

v-

T h e H o n o r able T h u r m a n S . H u r s t , C h ie f

J u s t i c e ; T h e H o n o r able D e n v e r N .

D a v is o n , V ic e C h ie f J u s t i c e ; T h e

H o n o r able F l e t c h e r R il e t , W a y n e

W. B a y l e s s , E ar l W e l c h , N. S. C o r n ,

B e n A r n o ld , T h o m a s L . G ib s o n , an d

J o h n L u t t r e l l , A sso cia t e J u s t ic e s of

t h e S u p r e m e C o u rt of t h e S t a t e of

O k l a h o m a ; T h e H o n o r a b le J u s t in

H in s h a w , D is t r ic t J udge C l e v e l a n d

C o u n t y D is t r ic t C ou rt of O k l a h o m a

a n d t h e B oard of R e g e n t s of t h e U n i

v e r s it y of O k l a h o m a .

Motion for Leave to File Petition for

Writ of Mandamus.

To the Honorable Fred M. Vinson, Chief Justice of the

United States and Associate Justices of the Supreme-

Court of the United States:

Petitioner, Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher, moves the Court for

leave to file the petition for a writ of mandamus hereto an

nexed; and further moves that an order and rule be entered

and issued directing the Honorable T h u r m a n S. H u r s t ,

Chief Justice; the Honorable D e n v e r N, D a v iso n , Vice

Chief Justice; and the Honorable F l e t c h e r R i l e y , W a y n e

W. B a y l e s s , E a r l W e l c h , N. S. C o r n , B e n A r n o ld , T h o m a s '

L. G-ib so n and J o h n L ttttrell, Associate Justices of the

Supreme Court of the State of Oklahoma; the Honorable

J u s t in H in s h a w , District Judge Cleveland County District

Court of Oklahoma, and the Board of Regents of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma, to show cause why a writ of mandamus

should not be issued against them in accordance with the

prayers of said petition and why your petitioner should not

have such other and further relief in the premises as may

he just and meet.

T hurgood M a r s h a l l ,

A m o s T . H a u l ,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

W il l ia m H . H a s t ie ,

E dw ard E . D u d l e y ,

M a r ia n W y n n P e r r y ,

Of Counsel.

January, 1948.

IN' THE

(Emirt of % Inttefc States

T h e H o n o rable T h u r m a n S . H u r s t , C h ie f

J u s t i c e ; T h e H o n o rable D e n v e r N.

D a v is o n , V ic e C h ie f J u s t i c e ; T h e

H o n o rable F l e t c h e r R i l e y , W a y n e

W . B a y l e s s , E a r l W e l c h , N. S . C o r n ,

B e n A r n o ld , T h o m a s L . G ib s o n , an d

J o h n L u t t r e l l , A sso ciate J u s t ic e s of

t h e S u p r e m e C o u r t o f t h e S t a t e of

O k l a h o m a ; T h e H o n o rable J u s t in

H in s h a w , D is t r ic t J ud ge C l e v e l a n d

C o u n t y D is t r ic t C ou rt of O k l a h o m a

a n d t h e B oard of R e g e n t s of t h e U n i

v e r s it y of O k l a h o m a .

To the Honorable the Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the

United States:

The petition of Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher respectfully

shows that:

I.

Petitioner, Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher, was petitioner in

the case of Ada Lois Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the Uni-

October Term, 1947

No. Miscellaneous

A d a L ois S ip u e l F is h e r ,

v-

Petitioner.

Petition for a Writ of Mandamus.

3

4

versify of Oklahoma, et al., No. 369-October Term-1947, on

writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court of the State of

Oklahoma. Petitioner is a citizen of the United States and

State of Oklahoma and is a resident of the State of Okla

homa. The Hon. T h u r m a n S. H u r s t , and the Hon. D e n v e r

N. D a v iso n are respectively the duly elected, qualified and

acting Chief Justice and Vice Chief Justice of the Supreme

Court of the State of Oklahoma; the Hon. F l e t c h e r R i l e y ,

W a y n e W . B a y l e s s , E a r l W e l c h , N. S. C o r n , B e n A r n o ld ,

T h o m a s L . G ib so n and J o h n L u t t r e l l are the duly elected,

qualified and acting Associate Justices of the Supreme

Court of the State of Oklahoma; the Hon. J u s t in H in s h a w

is the duly qualified District Judge of the Cleveland County

District Court of Oklahoma; the Board of Regents of the

University of Oklahoma is an administrative agency of the

State and exercises overall authority with reference to the

regulation of instruction and admission of students in the

University, a corporation organized as a part of the educa

tional system of the state and maintained by appropria

tions from the public funds of the State of Oklahoma.

II.

The purpose of this petition is to obtain from this Hon

orable Court, under authority of Section 262 of the Judicial

Code (28 U. S. C. 377) and Section 234 of the Judicial Code

(28 U. S. C. 342) a writ of mandamus in the nature of pro

cedendo to compel compliance with and to prevent the re

fusal to abide by the opinion and judgment of this Honor

able Court entered on January 12, 1948, on which mandate

was issued forthwith in No. 369-October Term, 1947, en

titled Ada Lois Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the Univer

sity of Oklahoma, et al. Petitioner herein was the peti

tioner in said case.

5

As appears from the record of this Honorable Court,

Case No. 369, October Term, 1947, entitled Ada Lois Sipuel

v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma, et al., was

argued before this Honorable Court on January 8,1948 and

was decided on January 12, 1948, in a Per Curiam opinion

which summarized the nature and history of the litigation

as follows:

“ On January 14, 1946, the petitioner, a Negro,

concededly qualified to receive the professional legal

education offered by the State, applied for admission

to the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma,

the only institution for legal education supported and

maintained by the taxpayers of the State of Okla

homa. Petitioner’s application for admission was

denied, solely because of her color.

Petitioner then made application for a writ of

mandamus in the District Court of Cleveland County,

Oklahoma. The writ of mandamus was refused, and

the Supreme Court of the State of Oklahoma affirmed

the judgment of the District Court. ____Okla._____,

180 P. 2d 135. We brought the case here for review.”

In these circumstances this Court in its aforesaid Per

Curiam opinion expressly stated and directed that the State

of Oklahoma must provide for the petitioner legal education

afforded by a state institution in conformity with the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment “ and pro

vide it as soon as it does for applicants of any other group.”

The cause was remanded and the mandate of this Court

was issued forthwith to the Supreme Court of Oklahoma

for proceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.

III.

6

The requirement of this Court that the State of Okla

homa act on behalf of petitioner as soon as it does for

applicants of any other group was in fact and plainly a

material part of the judgment of this Court. The case was

argued on January 8, 1948. During argument counsel for

respondents stated in open court that white students now

applying to enter the law school of the University of Okla

homa would be admitted on a day certain during this month

of January, 1948. This Court rendered its opinion four

days after argument and ordered that the mandate issue

forthwith. It was the plain intendment of this Court and

requirement of its decree that the State discharge its obli

gation to petitioner at a time not later than the opening of

the new law school term at the University of Oklahoma in

January, 1948.

. IV.

V.

The Law School of the University of Oklahoma is now

inviting white persons qualified to enter upon the study of

law to register for such instruction January 26, 1948, and

to begin the course of legal instruction at said University

on January 29, 1948.

VI.

Upon receipt of the mandate of this Honorable Court,

the Supreme Court of Oklahoma considered the effect to be

given to the said mandate, added the Oklahoma State

Regents for Higher Education as a party to the litigation,

on January 17, 1948, entered an order purporting to be con

sistent with the mandate of this Court and sent its mandate

7

to the District Court of Cleveland Comity, Oklahoma. The

petitioner had no opportunity to be heard in connection

with any of these proceedings. The order of the Supreme

Court of Oklahoma as issued January 17, 1948 provides:

‘ ‘ Said Board of Regents is hereby directed, under

the authority conferred upon it by the provisions of

Art. 13-A, Constitution of the State of Oklahoma, and

Title 70 0. S. 1941, Secs. 1976,1979, to afford to plain

tiff, and all others similarly situated, an opportunity

to commence the study of law at a state institution

as soon as citizens of other groups are afforded such

opportunity, in conformity with the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Federal

Constitution and with the provisions of the Consti

tution and statutes of this state requiring segregation

of the races in the schools of this state. Art. 13, Sec.

3, Constitution of Oklahoma; 70 0. S. 1941, Secs. 451-

457.”

The full text of the opinion of said Court is attached hereto

as “ Exhibit A ” and prayed to be read in full.

VII.

The aforesaid order of January 17, 1948, contains mu

tually contradictory provisions which prevent the execution

of a material part of the mandate of this Court. The afore

said order expressly limits petitioner opportunity to study

law by requiring that said study of law must be in con

formity with “ the provisions of the constitution and stat

utes of this state requiring segregation of the races in the

schools of this state. Art. 13, Sec. 3, Constitution of Okla

homa; 70 0. S. 1941, Secs. 451-457.” Among the sections

of the Oklahoma Statutes thus cited is Section 456 which

makes it a misdemeanor to teach white and colored students

in the same institution. The only state institution offering

8

a legal education now or at any time material to this liti

gation is the University of Oklahoma, an institution at

which white students only are now enrolled. The plain

intendment and the legal effect of the aforesaid order is to

make it a violation of the said order to admit petitioner

to the school of law of the University of Oklahoma, the only

state institution offering professional training in law.

VIII.

Counsel for the State of Oklahoma admitted in argument

of Case No. 369 before this Court on January 8, 1948 that

no steps had then been taken by the executive or adminis

trative officers of Oklahoma to organize or establish a sepa

rate school of law for Negroes. Petitioner asks that this

Court take judicial notice that the State of Oklahoma can

not by January 29, 1948 establish, organize and make avail

able to the petitioner a separate school of law which in

comparison to the law school of the University of Oklahoma

as that school is described in the Eecord of this litigation

(Record, Case No. 369, October Term, 1947, p. 23) would

afford the petitioner the equal protection of the law as re

quired by the mandate of this Court.

IX.

It follows that the Supreme Court of Oklahoma by its

own order, purportedly pursuant to the mandate of this

Court, has forbidden the only course of action which would

provide for the petitioner “ a legal education afforded by a

state institution . . . as soon as it does for applicants of any

other group ’ ’ as ordered by the mandate of this Court. Such

action of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma is a refusal to

abide by the clear mandate of this Court.

9

A mandate of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma incorpor

ating the order of the Court hereinbefore set forth was

issued forthwith to the District Court of Cleveland County,

Oklahoma. That court, in turn, purporting to carry out

the mandates of this Court and of the Supreme Court of

Oklahoma, on January 22, 1948 issued an order which is

inconsistent both with the mandate of this Court and the

mandate of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma and expressly

retained jurisdiction of the case. The said order of the

trial court is attached hereto as “ Exhibit B ” and prayed

to be read in full.

X.

XL

The aforesaid order of the trial court is inconsistent

with the order of this Court in that it designates the estab

lishment of a new and separate institution for the study of

law as an available method of complying with the duty of

the State in the premises and in that it designates as an

acceptable alternative the denial to white students and to

petitioner of the privilege of entering the School of Law of

the University of Oklahoma at the normal time of matricu

lation in January, 1948. The said order of the trial court

insofar as it provides even conditionally for the admission

of petitioner to the Law School of the University of

Oklahoma is inconsistent with so much of the mandate of

the Oklahoma Supreme Court as required that education be

provided for petitioner only in conformity with the con

stitutional and statutory requirements of Oklahoma regard

ing segregation.

10

Neither before nor since the issuance of the orders of

the state courts has petitioner been afforded the opportunity

which this Court directed the State of Oklahoma to provide

for her. The contradictory directions of the state courts

purporting to carry out the mandate of this Court have not

resulted in providing petitioner the relief to which she is

entitled under the mandate of this Court, but have created

such confusion and uncertainty with reference to the rights

of the petitioner and the duties of the agencies of the state

in connection therewith as to constitute a denial of the relief

ordered by this Court.

XII.

XIII.

Petitioner will suffer irreparable and inestimable dam

age by the judgments of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma

and the District Court of Cleveland County, Oklahoma, for

reasons set out above. The above-mentioned courts in re

fusing to abide by the mandate of this Court and in retain

ing jurisdiction of the case have left petitioner in the same

position in relation to the enforcement of her rights by the

Courts of Oklahoma as she was at the time the original

action was filed.

W herefore, the petitioner prays:

(1) That a writ of mandamus issue from the Court

directing the Honorable T h u r m a n S. H u r s t , Chief

Justice; The Honorable D e n v e r N. D a v iso n , Vice

Chief Justice; The Honorable F l e t c h e r R i l e y ,

W a y n e W. B a y l e s s , E a r l W e l c h , N. S. C o r n , B e n

11

A r n o l d , T h o m a s L . G ib s o n , an d J o h n L u t t r e l l ,

Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the

State of Oklahoma, to issue an order to the District

Court of Cleveland County, Oklahoma, requiring

that Court to issue the writ of mandamus as prayed

for in the original action, No. 369, October Term,

1947.

(2) That a writ of mandamus issue from this Court

directing the Honorable J u s t in H in s h a w , Judge of

the Cleveland County, Oklahoma, District Court, to

issue the writ of mandamus as prayed for in the

original action, No. 369, October Term, 1947.

(3) That a writ of mandamus issue from this Court

directing the Board of Regents of the University

of Oklahoma to admit petitioner forthwith as a reg

ular first year student of the School of Law of the

University of Oklahoma.

(4) That petitioner have such additional relief and

process as may be necessary and appropriate in the

premises.

Respectfully submitted,

T hurgood M a r s h a l l ,

A m o s T. H a l l ,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

W il l ia m H . H a s t ie ,

M a r ia n W y n n P e r r y ,

E dw ard R. D u d l e y ,

Of Counsel.

Bnpvmt (Enurt a! tit? Intted

O ctober Term, 1947

N o . ......... , M iscellaneous

A da L ois S ip u e l F is h e r ,

Petitioner,

v.

T h e H o n o r able T h u r m a n S . H u r s t , C h ie f

J u s t i c e ; T h e H o n o r able D e n v e r N .

D a v is o n , V ic e C h ie f J u s t ic e ; T h e

H o n o r able F l e t c h e r R il e y , W a y n e

W. B a y l e s s , E ar l W e l c h , N. S. C o r n ,

B e n A r n o ld , T h o m a s L . G ib s o n , an d

J o h n L u t t r e l l , A sso cia t e J u s t ic e s of

t h e S u p r e m e C o u rt of t h e S t a t e of

O k l a h o m a ; T h e H o n o r able J u s t in

H in s h a w , D is t r ic t J udge C l e v e l a n d

C o u n t y D is t r ic t C o u r t of O k l a h o m a

a n d t h e B oard of R e g e n t s of t h e U n i

v e r s it y of O k l a h o m a .

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF MOTION AND PETITION.

The history of the case and the nature of the action

taken by the Supreme Court o f Oklahoma and the District

Court of Cleveland County are set out in the petition for

a writ of mandamus and will not be repeated here.

In this brief we shall discuss, first, the respects in which

the action taken by the Supreme Court of Oklahoma and

the District Court o f Cleveland County are inconsistent

with the mandate of this Court and the resulting injury

to petitioner, and, second, the propriety of mandamus as

the remedy in this case.

13

14

L

The Supreme Court of Oklahoma and the District

Court of Cleveland County have violated the mandate

of this Court.

The action taken by the Supreme Court of Oklahoma

and the District Court have violated the mandate of this

Court in the following respects: (a) under the opinion and

mandate of this Court, the oidy act remaining to be done

by the Supreme Court of Oklahoma was the issuance of an

order to the District Court of Cleveland County directing it,

in turn, to issue the writ prayed for in the original peti

tion; (b) the opinion and mandate of this Court required

that the relief sought by petitioner be granted forthwith

without any reconsideration of the segregation statutes

previously relied on by the state; (c) the action taken by

the Supreme Court of Oklahoma and the District Court

denies petitioner a legal education now as required by the

mandate of this Court.

On January 14, 1946, this petitioner made application to

the University of Oklahoma for admission to the School

of Law. It was the only school maintained by the tax

payers of Oklahoma for the legal education of its citizens.

Petitioner’s qualifications were admitted and have never

been disputed. Her application was denied solely on the

grounds of her race and color, in violation of the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Federal Constitution.

Petitioner then applied to the District Court of Cleve

land County, Oklahoma, for a writ of mandamus compelling

the Board of Regents to admit her to the only law school

maintained by the state. That court denied her the writ

on the ground that such a writ would not issue since it

15

would compel these state officials to violate the segregation

statutes of that state which carried a criminal penalty for

non-compliance. The Supreme Court of Oklahoma affirmed

this denial of the writ on this same ground. This Court on

January 12, 1948, reversed the holding of the lower court

and issued its mandate “ forthwith.”

Under the mandate of this Court petitioner was entitled

to an order directing that she be admitted to the Univer

sity of Oklahoma Law School for the term commencing

January 29, 1948.

At the time of the decisions and orders of both the Su

preme Court of Oklahoma and the District Court of Cleve

land County there was only one institution maintained by

the State for the legal education of its citizens, in which

school white students were then eligible to enroll. The

Per Curiam opinion of this Court stated that petitioner’s

education must be furnished by the state as soon as it is

furnished to other students.

It is a fact heretofore admitted by the state in argu

ment before this Court, and alleged in the present petition

that entering white students are to begin their legal studies

at the University of Oklahoma on January 29, 1948.

To the time of filing this petition, three days before

the new term at the Oklahoma University Law School, how

ever, the petitioner has no assurance of a legal education

to be provided by the State of Oklahoma pursuant to the

clear mandate of this Court. She has not been admitted to

any school and there is no law school other than the Univer

sity of Oklahoma Law School maintained by the state.

While it is true that the District Court’s order purports

to recognize petitioner’s right to a legal education on the

same basis as white citizens, petitioner asserts that this

right has been paid lip service and conceded to her through

16

out the two years since she first applied for a legal educa

tion. The recognition of this right, in a decree frustrating

its exercise, leaves petitioner exactly where she was before

the decision of this Court. Any decree which does not

plainly and unequivocally direct her admission to the Uni

versity of Oklahoma must fail to achieve compliance with

the mandate of this Court.

In the light of the decision of this Court that the peti

tioner must receive her legal education at the same time

that it is offered to white students, the action of the State

Supreme Court in requiring that this be done within the

policy of segregation, when only one facility exists and

time is of the essence, constitutes a clear violation of the

mandate of this Court and of the ruling in Missouri ex rel.

Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337.

Petitioner asks this Court to take judicial notice of the

fact that it is completely impossible to set up, within a

period of one week, a law school which would offer adequate

facilities for the acquisition of the professional skills neces

sary for the practice of the law. Eminent authorities in

the field of legal education have demonstrated that there

are certain features of a law school which are necessary to

a proper legal education which can only be found in a full-

time, accredited law school.1 Some of these are: a full-time

faculty,2 a varied and inclusive curriculum,3 an adequate

library, well-equipped building and several classrooms,4 a

well-established, recognized law review and a moot court.5

1 See Boyer, Smaller Law Schools: Factors Affecting Their

Methods and Objectives, 20 Oregon Law Rev. 281 (1941).

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Townes, Organization and Operation of a Law School, 2 Am.

Law School Rev. 436 (1910) ; Ballantine, The Place in Legal Educa

tion of Evening & Correspondence Law Schools, 4 Am. Law School

Rev. 369 (1918).

5 See Boyer, Smaller Law Schools: Factors Affecting Their

Methods and Objectives, 20 Oregon Law Rev. 281 (1941).

17

Equally essential to a proper legal education in a demo

cratic society is the inter-change of ideas and attitudes

which can only be effected when the student-body is repre

sentative of all groups and peoples. Exclusion of any one

group on the basis of race, automatically imputes a badge

of inferiority to the excluded group—an inferiority which

has no basis in fact.6 The role of the lawyer, moreover, is

often that of a law-maker, a “ social mechanic” , and a

“ social inventor.” 7 A profession which produces future

legislators and social inventors to whom will fall the social

responsibilities of our society, can not do so on a segregated

basis.8 Quite aside from consideration of those factors

which are necessary for a proper legal education, it is evi

dent, on its face, that one student cannot constitute a law

school.

The core of the decision of the Oklahoma courts, prior

to the decision of this Court, was that the segregation

statutes of the State of Oklahoma were an effective bar to

petitioner’s right to attend the University of Oklahoma,

despite the Fourteenth Amendment. The present position

of the Oklahoma courts is to the same effect despite the

mandate of this Court. For example, the decision of the

Supreme Court of Oklahoma states:

‘ ‘ Said Board of Regents is hereby directed, under

the authority conferred upon it by the provisions of

Art. 13-A, Constitution of the State of Oklahoma,

and Title 70 O. S. 1941, Sees. 1976, 1979, to afford to

6 The Black and White of Rejections for Military Service, Ameri

can Teachers Association, August, 1944, page 29; Otto Klineberg,

Negro Intelligence and Selective Migration, New York, 1935;

J. Peterson & L. H. Lanier, “Studies in the Comparative Abilities of

Whites and Negroes,” Mental Measurement Monograph, 1929.

7 Simpson, The Function of a University Law School, 49 Harv.

L. Rev. 1068, 1072. See also McCormick, The Place and Future of

the State University Law School, 24 N. C. L. Rev. 441.

8 Simpson, op. cit. p. 1069. See also Stone, The Public Influence

of the Bar, 48 Harv. L. Rev. 1.

18

plaintiff, and all others similarly situated, an op

portunity to commence the study of law at a state

institution as soon as citizens of other groups are

afforded such opportunity, in conformity with the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the Federal Constitution and with the pro

visions of the Constitution and statutes of this stat,e

requiring segregation of the races in the schools of

this state. Art. 13, See. 3, Constitution of Okla

homa; 70 0. S. 1941, Secs. 451-457.” (Italics added.)

The order of the District Court of Cleveland County

states:

“ I t is , t h e r e f o r e , ordered, a d jud g ed a n d decreed

b y t h is C o u r t that unless and until the separate

school of law for negroes, which the Supreme Court

of Oklahoma in effect directed the Oklahoma State

Regents for Higher Education to establish . . . is

established and ready to function at the designated

time applicants of any other group may hereafter

apply for admission to the first year class of the

School of Law of the University of Oklahoma, . . .

the defendants, Board of Regents of the University

of Oklahoma, et al., be and the same are hereby

ordered and directed to either:

(1) enroll plaintiff . . . , or

(2) not enroll any applicant of any group in said

class until said separate school is established

and ready to function.”

It is therefore clear that the action of the Supreme Court

of Oklahoma and the District Court of Cleveland County

violates the mandate of this Court and leaves the petitioner

in relation to the enforcement of her rights by the Oklahoma

courts in the same position she was in when she originally

applied to those courts in 1946.

19

II.

Mandamus Is the appropriate rem edy in this case.

The authority of this Court to issue a writ of mandamus

is derived from Section 262 of the Judicial Code (36 Stat.

1162, 28 U. S. C. 377), which provides that the federal courts

“ shall have power to issue all writs not specifically pro

vided for by statute, which may be necessary for the exer

cise of their respective jurisdictions, and agreeable to the

usage and principles of law. ’ ’

Mandamus is the appropriate remedy in this case for

the reason that: (1) the writ will always lie to compel

obedience to a mandate of an appellate court; (2) review

on appeal is not an adequate remedy because of the delay

and injury to petitioner attendant upon that procedure.

Mandamus W ill A lw ays Lie to Compel Obedience

to a M andate o f This Court.

The right of this Court to issue writs of mandamus in

aid of its appellate jurisdiction has been recognized in a

long, unbroken line of decisions. In 1859 Mr. Chief Justice

T a n e y , in the case of United States v. Fossatt, 21 How. 445,

stated: “ But when a case is sent to the court below by

a mandate from this court, no appeal will lie from any order

or decision of the court until it has passed its final decree in

the case. And if the court does not proceed to execute the

mandate, or disobeys and mistakes its meaning, the party

aggrieved may, by motion for a mandamus, at any time,

bring the errors or omissions of the inferior court before

this court for correction.”

The reasons for this rule are clear. Once a case has

been decided by this Court and has been remanded to the

lower court, the lower court is bound by the mandate of this

20

Court as the law of the ease and must carry it into execu

tion pursuant to said mandate. The lower court cannot

vary it or examine it for any purpose other than execution

or give any other or further relief, or review it even for

apparent error, upon any matter decided on appeal, or

intermeddle with it, further than to settle so much as has

been remanded.9

Where, as here, both the State Supreme Court and the

District Court, while purporting to follow the mandate of

this Court, have in fact refused to abide by the mandate of

this Court, the very existence of government by law is

threatened and a writ of mandamus should issue from this

Court.

But for the decision of this Court, its mandate and the

authority of this Court to issue mandamus, petitioner’s

federally protected rights are no nearer realization than

at the time she first applied for relief in the Cleveland

County District Court. The courts and the administrative

agencies of the State of Oklahoma continue effectively to

deprive petitioner of her federally protected rights in open

defiance of the Constitution of the United States and the

mandate of this Court. Petitioner is left remediless with

out the affirmative enforcement of her rights by this Court

through the issuance of the writ of mandamus as prayed

for in her petition.

9 Ex Parte Texas, 315 U. S. 8 ; Fed. Communications Commis

sion v. Pottsville, 309 U. S. 134; Ex Parte Union Steamboat Co.,

178 U. S. 317; In re Potts, 166 U. S. 263; In re Sandford Fork and

Tool Co., 160 U. S. 247; Ex Parte Sibbald, 12 U. S. 488; U. S. v.

Fossatt, 21 How. 445.

Conclusion.

W h e r e fo r e , i t is r e s p e c tfu lly su b m itte d th a t th e p e t i

tio n f o r w r it o f m an d a m u s be iss u e d a s p r a y e d f o r an d th a t

th e p e t it io n e r be g iv e n w h a te v e r fu r th e r r e lie f is m e e t an d

p ro p e r .

T httrgood M a r s h a l l ,

A m o s T . H a l l ,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

W il l ia m H . H a s t ie ,

M a r ia n W y n n P e r r y ,

E dw ard E . D u d l e y ,

Of Counsel.

January, 1948.

Exhibit A.

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF OKLAHOMA

A da L ois S ip u e l , \

Plaintiff in Error, I

vs. I

B oard op R e g e n t s of t h e U n iv e r s it y of \ No. 32756

O k l a h o m a , G eorge L . C ro ss, M a u r ic e I

H. M e r r il l , G eorge W a d s a c k , and I

R o y G it t in g e r , |

Defendants in Error. J

S y l l a b u s

1. The decision of the Supreme Court of the United

States upon an issue of law involving a right guaranteed

a person by the Constitution of the United States is bind

ing upon the State of Oklahoma. Upon a reversal and re

mand of a cause or proceeding involving such right, this

court, when ordered and directed so to do, will proceed not

inconsistent with the opinion of the Supreme Court of the

United States.

2. It is the State’s policy, established by Constitution

and statutes, to segregate white and negro races for pur

pose of education at institutions of higher learning.

3. It is the duty of the Supreme Court of the State of

Oklahoma to maintain State’s policy of segregating white

and negro races for purpose of education so long as it does

not conflict with Federal Constitution.

24

4. It is the duty of the Oklahoma State Regents for

Higher Education to afford citizens of the negro race op

portunity for education in conformity with the equal pro

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal

Constitution and with the provisions of the Constitution

and statutes of this state requiring segregation of the races

in the schools of the state. Art. 13, Sec. 3, Constitution of

Oklahoma; 70 0. S. 1941 Secs. 451 et seq.

A p p e a l F b o m D is t r ic t C o u r t op C l e v e l a n d C o u n t y

O k l a h o m a

Hon. B e n T. W il l ia m s , Judge

Regents of Higher Education of the State of Oklahoma

ordered and directed to proceed according to law.

Mandate directed to issue forthwith. Trial Court or

dered and directed to proceed not inconsistent with the

opinion of the Supreme Court of the United States and this

opinion.

A m o s T. H a l l , Tulsa, Oklahoma

T h urgood M a r s h a l l an d

R o ber t C . C a r te r of New York, N. Y. For P la in t i f f in

Error.

F r a n k l in H. W il l ia m s of New York, N. Y. of Counsel

M a c Q. W il l ia m s o n , Attorney General

F red H a n s e n , Asst. Attorney General

M a u r ic e H. M e r r il l and J o h n B. C h e a d l e , both of Nor

man, Oklahoma. For Defendants in Error.

25

Per Curiam:

On April 29, 1947, this court affirmed the District Court

of Cleveland County, Oklahoma, denying a writ of man

damus sought by Ada Lois Sipuel, a negro, in a proceeding

by which she sought to compel her enrollment and admis

sion as a student in the Law School of the University of

Oklahoma.

The Supreme Court of the United States reversed the

judgment of this court by its opinion which follows:

in THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Monday, January 12, 1948

No. 369— October Term, 1947

“ A da L ois S ip u e l ,

Petitioner,

v .

B oard of R e g e n t s of t h e U n iv e r s it y

of O k l a h o m a , et al.,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme

Court of the State of Oklahoma

“ Per Curiam

“ On January 14, 1946, the petitioner, a Negro, con-

cededly qualified to receive the professional legal education

offered by the State, applied for admission to the School

of Law of the University of Oklahoma, the only institution

for legal education supported and maintained by the tax

payers of the State of Oklahoma. Petitioner’s application

for admission was denied solely because of her color.

26

“ Petitioner tlien made application for a writ of man

damus in the District Court of Cleveland County, Oklahoma.

The writ was refused, and the Supreme Court of the State

of Oklahoma affirmed the judgment of the District Court.

______ Okla. ______ , 180 P. 2d 135. We brought the case

here for review.

“ The petitioner is entitled to secure legal education

afforded by a state institution. To this time, it has been

denied her although during the same period many white

applicants have been afforded legal education by the State.

The State must provide it for her in conformity with the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and

provide it as soon as it does for applicants of any other

group. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337

(1938).

“ The judgment of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma is

reversed and the cause is remanded to that court for pro

ceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.

“ The mandate shall issue forthwith.”

The Supreme Court of the United States in the Gaines

case, citing many of its former opinions, reaffirmed the

Constitutions and laws of states creating separate schools,

saying:

“ In answering petitioner’s contention that this

discrimination constituted a denial of his constitu

tional right, the state court has fully recognized the

obligation of the state to provide negroes with advan

tages for higher education substantially equal to the

advantages offered to white students. The state has

sought to fulfill that obligation by furnishing equal

facilities in separate schools, a method the validity

of which has been sustained by our decisions.”

27

That court has not since held to the contrary.

The Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education is

the only authority empowered by Constitution and statutes,

on behalf of the State of Oklahoma, to provide legal edu

cation in a state institution for petitioner as soon as appli

cants of any other group of persons of this state may be

enrolled and admitted to secure legal education in a state

institution.

On January 15, 1948, the said Board filed in this court

its motion seeking to be made a party and requesting us to

define its powers and duties and direct it in the premises.

Accordingly, on January 16, 1948, the said Board of Re

gents, by order of this court, was made a party to the pro

ceedings.

Said Board of Regents is hereby directed, under the

authority conferred upon it by the provisions of Art. 13-A,

Constitution of the State of Oklahoma, and Title 70 0. S.

1941, Secs. 1976, 1979, to afford to plaintiff, and all others

similarly situated, an opportunity to commence the study

of law at a state institution as soon as citizens of other

groups are afforded such opportunity, in conformity with

the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

of the Federal Constitution and with the provisions of the

Constitution and statutes of this state requiring segregation

of the races in the schools of this state. Art. 13, Sec. 3,

Constitution of Oklahoma; 70 0. S. 1941, Secs. 451-457.

Reversed with directions to the trial court to take such

proceedings as may be necessary to fully carry out the

opinion of the Supreme Court of the United States and this

opinion. The mandate is ordered to issue forthwith.

Reversed.

H u r s t , C. J., D a v iso n , V. C. J., R il e y , B a y l e s s , W e l c h ,

G ib s o n , A r n o ld , L u t t r e l l , JJ. co n cu r.

28

Exhibit B.

IN THE

DISTRICT COURT OF CLEVELAND COUNTY,

S t a t e op O k l a h o m a .

A da L o is S ip u e l , \

Plaintiff, 1

vs. I

B oakd op R e g e n t s op t h e U n iv e r s it y op \ ]^0 - 44^07

O k l a h o m a , G eorge L. C ro ss, M a u r ic e [

H. M e r r il l , G eorge W ad sac k , a n d \

R o y G it t in g e r , I

Defendants. I

J o u r n a l E n t r y

N ow on this, th e ____day of January, 1948, the above-

entitled cause came on to be heard by this court on the

January 17,1948 opinion and mandate of the Supreme Court

of the State of Oklahoma herein, reversing the decision

rendered by this court at the trial of said cause and direct

ing it

“ to take such proceedings as may be necessary to

fully carry out the opinion of the Supreme Court of

the United States and this opinion.”

From an examination of said opinion and mandate, this

court finds:

1. That the material part of the opinion of the Supreme

Court of the United States, above referred to (said opinion

29

being quoted in full in the instant opinion of the Supreme

Court of Oklahoma), is as follows:

“ The petitioner is entitled to secure legal education

afforded by a state institution. To this time, it has

been denied her although during the same period

many white applicants have been afforded legal edu

cation by the State. The State must provide it for

her in conformity with the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment and provide it as soon

as it does for applicants of any other group. Missouri

ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 IT. S. 337 (1938).

“ The judgment of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma

is reversed and the cause is remanded to that court

for proceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.”

2. That the Supreme Court of Oklahoma found in its

instant opinion that in the opinion of the Supreme Court

of the United States in the Gaines case, supra (which case

is cited with approval by the Supreme Court of the United

States in its instant opinion), said court reaffirmed the

constitutional validity of state laws providing for the edu

cation of the negro and white races,

“ by furnishing equal facilities in separate schools, a

method the validity of which has been sustained by

our decisions.”

3. That the Supreme Court of Oklahoma, after in effect

stating that the Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Edu

cation were the only authority empowered by law to estab

lish such a separate school, directed said regents

“ to afford to plaintiff, and all others similarly situ

ated, an opportunity to commence the study of law

at a state institution as soon as citizens of other

groups are afforded such opportunity, in conformity

with the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Federal Constitution and with the

provisions of the Constitution and statutes of this

30

state requiring segregation of the races in the schools

of this state.”

4. That the Supreme Court of Oklahoma did not direct

this court as to what judgment should be rendered thereby

other than to state, as aforesaid, that this court’s judgment

at the trial, of this case was reversed, and that this court

should

“ take such proceedings as may be necessary to fully

carry out the opinion of the Supreme Court of the

United States and this opinion.”

5. That in the original opinion of the Supreme Court of

the State of Oklahoma herein (180 Pae. (2d) 135), decided

June 24, 1947, said court quoted the following language

from the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States

in the Gaines case:

“ We are of the opinion that the ruling [of the Su

preme Court of Missouri] was error, and that peti

tioner was entitled to be admitted to the law school

of the State University in the absence of other and

proper provision for his legal training within the

State.” ,

and held:

“ The reasoning and spirit of that decision [the

Gaines decision] of course is applicable here, that is,

that the state must provide either a proper legal

training for petitioner in the state, or admit peti

tioner to the University Law School.”

6. That the Supreme Court of Oklahoma, however, took

the position in its said original opinion that the State of

Oklahoma was not obligated to provide the plaintiff, Ada

Lois Sipuel (now Mrs. Warren W. Fisher), such “ legal

training” until she had applied to the Oklahoma State

Regents for Higher Education for legal training at a sep

31

arate state institution or ‘ 4substantial notice” had been

given said regents as to there being at least some “ patron

age” for such an institution.

7. That the above position of the Supreme Court of

Oklahoma as to the necessity of such an application or

notice was in effect rejected by the Supreme Court of the

United States in its instant opinion, wherein it is stated

that plaintiff is entitled “ to secure legal education afforded

by a state institution, ’ ’ and that the state must provide such

education for her

“ in conformity with the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment and provide it as soon

as it does for applicants of any other group.”

I t is , th e r e f o r e , ordered, ad ju dg ed a s d decreed b y t h is

C o u rt that unless and until the separate school of law for

negroes, which the Supreme Court of Oklahoma in effect

directed the Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education

to establish

“ with advantages for education substantially equal

to the advantages afforded to white students, ’ ’

is established and ready to function at the designated time

applicants of any other group may hereafter apply for ad

mission to the first-year class of the School of Law of the

University of Oklahoma, and if the plaintiff herein makes

timely and proper application to enroll in said class, the

defendants, Board of Regents of the University of Okla

homa, et ah, be, and the same are hereby ordered and di

rected to either:

(1) enroll plaintiff, if she is otherwise qualified, in the

first-year class of the School of Law of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma, in which school she will be

entitled to remain on the same scholastic basis as

32

other students thereof until such a separate law

school for negroes is established and ready to func

tion, or

(2) not enroll any applicant of any group in said class

until said separate school is established and ready

to function.

I t is f u r t h e r ordered , adju dged an d decreed that if such

a separate law school is so established and ready to function,

the defendants, Board of Regents of the University of Okla

homa, et ah, be, and the same are hereby ordered and di

rected to not enroll plaintiff in the first-year class of the

School of Law of the University of Oklahoma.

The cost of this case is taxed to defendants.

This court retains jurisdiction of this cause to hear and

determine any question which may arise concerning the

application of and performance of the duties prescribed by

this order.

/ s / J u s t in H in s h a w

Judge

L awyers P ress, I nc., 165 William St., N. Y. C. 7; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300