Alexander v. Riga Reply Brief of Cross Appellants

Public Court Documents

August 16, 1999

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Alexander v. Riga Reply Brief of Cross Appellants, 1999. 3a687173-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b37de8dc-7f06-454b-9700-3c5134195884/alexander-v-riga-reply-brief-of-cross-appellants. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

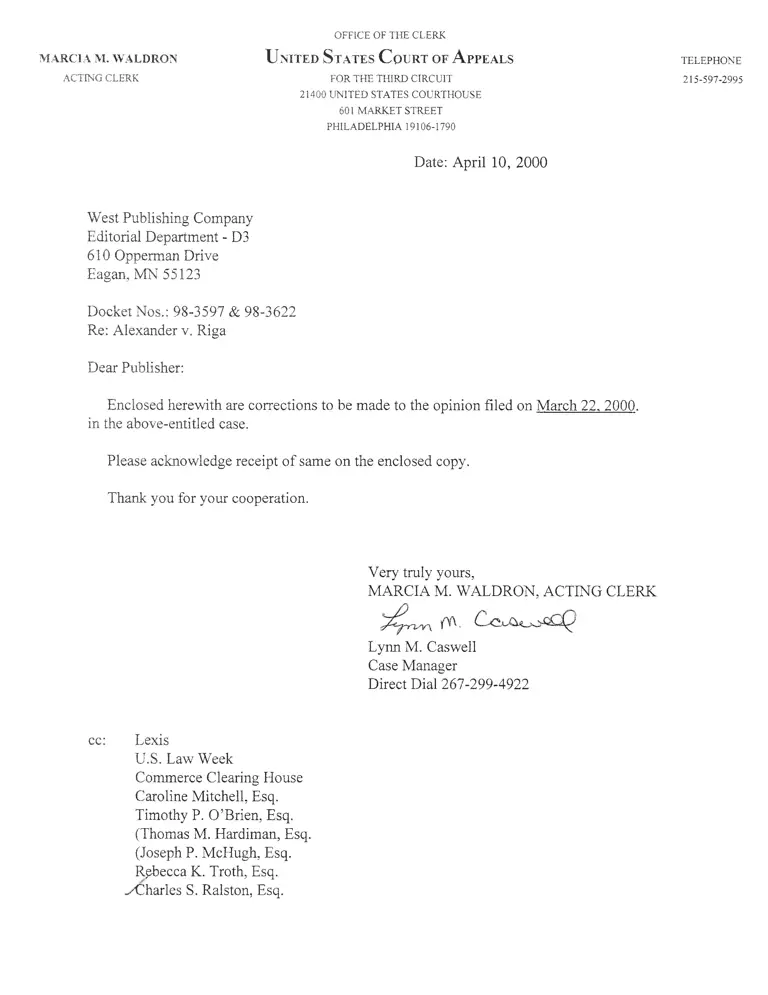

OFFICE OF THE CLERK

MARCIA M. WALDRON

ACTING CLERK

U n it e d S t a t e s C o u r t of A ppea ls

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

21400 UNITED STATES COURTHOUSE

TELEPHONE

215-597-2995

601 MARKET STREET

PHILADELPHIA 19106-1790

Date: April 10, 2000

West Publishing Company

Editorial Department - D3

610 Opperman Drive

Eagan, MN 55123

Docket Nos.: 98-3597 & 98-3622

Re: Alexander v. Riga

Dear Publisher:

Enclosed herewith are corrections to be made to the opinion filed on March 22. 2000.

in the above-entitled case.

Please acknowledge receipt of same on the enclosed copy.

Thank you for your cooperation.

cc: Lexis

U.S. Law Week

Commerce Clearing House

Caroline Mitchell, Esq.

Timothy P. O’Brien, Esq.

(Thomas M. Hardiman, Esq.

(Joseph P. McHugh, Esq.

Rpbecca K. Troth, Esq.

--/Charles S. Ralston, Esq.

Very truly yours,

MARCIA M. WALDRON, ACTING CLERK

Lynn M. Caswell

Case Manager

Direct Dial 267-299-4922

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

Nos. 98-3597 & 98-3622

Alexander v. Riga

The following modifications have been made to the Court's

O p i n i o n issued on March 22, 2000, to the above-entitled appeal

and will appear as part of the final version of the opinion:

Page 8, line 2 o f the cite after the indented quote: please change the year o f

Simmons to 1991 rather than 1996

Page 8, line 3 o f the last paragraph: delete the word “plain” after the word

“committed” and “error”

Line 12 o f same paragraph: delete “Id., see also Bowley V. Stotler, 751

F.2d 652 (3d Cir. 1985)” and insert: Simmons, 947 F.2d at 1078.

Page 11, line 5 o f the last paragraph: please change the year in the Tyus cite to

read “ 1996" rather than “ 1997"

Page 13, line 4 o f the first full paragraph: please insert 98" betw een “89" and

“(1st Cir. 1999).”

Page 15, line 4 o f the second lull paragraph: please delete “ , Bonjom o v. Kaiser

Aluminum & Chern., 752 F.2d 802, 814-15 (3d Cir. 1984), cert, denied, 477 U.S. 908

(1986).

Page 16, first paragraph after indented cite, line 2: please add “ ----- ” between

“statute” and Bennett v. Spear.

Line 3, o f same paragraph: please correct cite to read “ 154, 173" rather than

“54".

Line 4 o f last paragraph: please delete “See” before the cite to Kolstad v.

American Dental Association

Very truly yours,

7--

/s/ MARCIA M. WALDRON,

Acting Clerk

Dated: April 10, 2000

Nos. 98-3597; 98-3622

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

RONALD ALEXANDER; FAYE ALEXANDER; FAIR HOUSING

PARTNERSHIP OF GREATER PITTSBURGH, INC.

Appellants/Cross Appellees,

v.

JOSEPH RIGA; MARIA A. RIGA,

a/k/a CARLA AGNOTTI,

Appellees/Cross Appellants.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA

Civil Action No. 95-1239

REPLY BRIEF OF CROSS APPELLANTS

THOMAS M. HARDIMAN

JOSEPH P. MCHUGH

Titus & McConomy LLP

Twentieth Floor

Four Gateway Center

Pittsburgh, PA 15222

(412) 642-2000

Counsel for Appellees/Cross Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............................................................................... ii

I. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................... 1

II. ARGUM ENT.............................................................................................. 2

A. The Rigas Did Not Waive Their

Argument That FHP Lacks S tan d in g ........................................... 2

B. This Court Should Not Overrule Its

Recent Decision In Montgomery New spapers............................. 5

C. Evidence Of The Alexanders’ Poor

Credit Was Improperly Excluded .............................................. 11

D. The Trial Court Abused Its

Discretion In Excluding Evidence

Bearing On The Alexanders’ C redibility .................................. 13

III. CONCLUSION ........................................................................................ 15

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES: Page

Carter v. Hewitt, 617 F.2d 961 (3d Cir. 1980) ............................................. 15

Chauhan v. M. Alfieri Co., Inc.,

897 F.2d 123 (3d Cir. 1989) ......................................................................... 13

Fair Housing Council of Suburban Philadelphia v.

Montgomery Newspapers, 141 F.3d, 71

(3d Cir. 1998)................................................................................................ 1,5-11

Havens Realty Corp. v. Coleman, 455 U.S. 363 (1982) ................. .. 7

Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555 (1992) ..................................... 9

MacDonald v. General Motors Corp.,

110 F.3d 337 (6th Cir. 1997) ............................................................................ 4

Mardell v. Harleysville Life Ins. Co.,

65 F.3d 1072 (3d Cir. 1995) ......................................................................... 12

McKennon v. Nashville Banner Pub. Co.,

513 U.S. 352 (1995) ........................................................................................ 11

New York State Nat. Org. for Women v.

Terry, 159 F.3d 86 (2d Cir. 1998) .................................................................... 4

United States v. Atwell, 766 F.2d 416 (10th Cir. 1 9 8 5 ) ............................... 14

Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490 (1975) ............................................................ 6, 7

Williams v. Runyon, 130 F.3d 568 (3d Cir. 1 9 9 7 ) ........................................ 3-4

ii

CONSTITUTION: Page

Article 111........................................................................................................ 1, 6, 13

RULES:

Fed. R. Civ. P. 50 ............................................................................................. i_4

Fed. R. Evid. 403 ............................................................................................. 14-15

Fed. R. Evid. 4 0 4 (b ) ................................................................ 13

Fed. R. Evid. 608 .................................................................................. .. 2, 13-15

MISCELLANEOUS:

Adv. Comm. Note to Rule 403 .......................................................................... 15

m

I, INTRODUCTION

Cross-Appellee Fair Housing Partnership of Greater Pittsburgh, Inc.

("FHP") argues that Cross-Appellants Joseph and Maria Riga (the "Rigas")

waived their right to challenge FHP’s standing because they failed to raise the

issue in a motion under Rule 50 of the Rules of Civil Procedure and because

they judicially admitted that FHP had standing. Both contentions are incorrect.

The Rigas raised the issue of standing in their Rule 50 motion. Moreover,

whether they did so or not is irrelevant to their right to appeal the trial court’s

earlier denial of summary judgment on that issue. FHP also misconstrues the

concept of a judicial admission. Counsel for the Rigas made no explicit

admission of a factual matter. Rather, he gave a qualified answer to a

hypothetical question about a legal issue.

Without explicitly doing so, FHP asks this Court to overrule its recent

decision, based on Article III of the Constitution, stating that fair housing

organizations cannot manufacture standing for themselves by diverting their

resources to litigation. This Court’s reasoning in Fair Housing Council of

Suburban Philadelphia v. Montgomery Newspapers. 141 F.3d 71 (3d Cir.

1998), was correct in that case and applies with equal force in the instant case.

Finally, Cross-Appellees Ronald and Faye Alexander (the "Alexanders")

argue that the Trial Court properly excluded evidence of their bad credit and

properly prohibited cross-examination on matters bearing on their truthfulness.

The Alexanders mistakenly rely on the inapposite after-acquired evidence

doctrine pertinent in employment discrimination cases where an employer’s

motive is at issue. And they assert a concept of prejudice so broad as to

eviscerate Rule 608 of the Federal Rules of Evidence. The probative value far

outweighed any potential prejudice from questions which tended only to

demonstrate that the Alexanders were untruthful, not that they were evil people.

IL ARGUMENT

A. The Rigas Did Not Waive Their

Argument That FHP Lacks Standing.

FHP argues that the Rigas waived their right to appeal the Trial Court’s

denial of summary judgment against FHP for lack of standing. Reply Brief of

Appellants ("Reply Brief") at 22-23. FHP claims first that the Rigas failed to

raise the issue in their Rule 50 motion and second that the Rigas’ judicially

admitted standing when their counsel responded to a hypothetical question

posed by the trial court. IcL For the reasons that follow, both assertions are

incorrect.

The Rigas raised the issue of FHP’s standing in their Rule 50 motion,

both at the close of Plaintiffs’ case and at the close of all the evidence. The

2

Rigas’ counsel, Mr. Hardiman, explicitly stated as part of his Rule 50 argument

at the close of Plaintiffs’ case: "I want the record to be clear, under the

holdings of the Circuit, the Third Circuit, and not yet ruled on under the DC

Circuit cases, a fair housing corporation, non-profit, such as the Fair Housing

Partnership here, cannot confer standing upon itself by getting involved in a

lawsuit." A1165. At the close of all the evidence, the Rigas renewed their

motion: "Your Honor, the defendants filed a cross motion pursuant to Rule

50." A1169. Rather than having another colloquy in which the same

arguments were repeated, the trial court simply stated: "All right. For the

reasons I’ve already articulated, both motions are denied." A1169. Thus, the

arguments made at the close of the Plaintiffs case were renewed by the Rigas

and again rejected at the close of all evidence.

Moreover, whether the Rigas raised the standing issue in their Rule 50

motion is irrelevant to whether they may appeal the trial court s denial of their

standing argument in their summary judgment motion. FHP argues that

"[fjailure to raise sufficiency of FHP’s standing evidence by Rule 50 motion at

close of evidence constitutes waiver of the issue." Reply Brief at 23. In

support of this assertion FHP cites Williams v. Runyon, 130 F.3d 568 (3d Cir.

1997). Williams is inapposite, however. It does not stand for the proposition

3

that failure to raise an issue in a Rule 50 motion waives the right to appeal an

earlier denial of summary judgment on the same issue. This Court in Williams

simply noted that failure to raise an issue in a Rule 50 motion for directed

verdict (prior to submission of the case to the jury) waives the right to raise the

issue in a renewed Rule 50 motion for judgment after the trial (Le^, judgment

notwithstanding the verdict). Ich at 571-72. FHP has not cited any case or rule

which prohibits appeal of a summary judgment ruling based on failure to raise

an issue in a Rule 50 motion. Accordingly, the Rigas did not waive their right

to appeal the trial court’s denial of their Motion for Summary Judgment due to

FHP’s lack of standing.

Secondly, the Rigas did not judicially admit that FHP had standing.

Whether FHP had standing is a legal matter, not a factual one. Judicial

admissions "are statements of fact rather than legal arguments made to a court."

New York State Nat. Org. for Women v. Terry. 159 F.3d 86, 97 n.7 (2d Cir.

1998). Nor can a qualified answer to a hypothetical question constitute a

judicial admission. To qualify as a judicial admission "an attorney’s statements

must be deliberate, clear and unambiguous." MacDonald v. General Motors

Corp.. 110 F.3d 337, 340 (6th Cir. 1997). The court in MacDonald noted that

counsel’s statements "dealt with opinions and legal conclusions, and we are thus

4

reluctant to treat them as binding judicial admissions." kL Likewise in this

case, Mr. Hardiman was responding to a hypothetical question regarding a legal

conclusion. And he explicitly rejected any suggestion that FHP had standing

given the facts of this case. His response can in no way be deemed a binding

judicial admission. Therefore, the Court should reject FHP’s tenuous

argument.

B. This Court Should Not Overrule Its

Recent Decision In Montgomery Newspapers.

Just last year, this Court directly addressed the issue of a fair housing

organization’s standing and held that "the pursuit of litigation alone cannot

constitute an injury sufficient to establish standing under Article III." Fair

Housing Council of Suburban Philadelphia v. Montgomery Newspapers, 141

F.3d 71, 79 (3d Cir. 1998). FHP essentially asks this Court to reverse itself

and overrule Montgomery Newspapers by adopting a broad rule that "agencies

such as FHP have status to enforce Title VIII as ‘aggrieved persons.’" Reply

Brief at 28. In other words, a fair housing organization which becomes

involved in a housing discrimination lawsuit should automatically be deemed to

have standing. Why? Because Congress has placed such importance on the

private attorney general role of those organizations, particularly since " (tjhose

5

illegally denied housing are often ignorant and unsophisticated, and require

agency assistance." See Reply Brief at 24-26 and 28-29. Putting aside the

condescending paternalism of such an argument, the per se rule proposed by

FHP would be unconstitutional.

In its zeal to satisfy the prudential aspects of standing, FHP ignores the

constitutional requirements. As this Court discussed in Montgomery

Newspapers. "[t]he standing inquiry in most cases is two-tiered, involving ‘both

constitutional limitations on federal-court jurisdiction and prudential limitations

on its exercise." IcL at 74, quoting Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S, 490, 498 (1975).

FHP is correct that this Court in Montgomery Newspapers noted that prudential

standing requirements have been eliminated in cases arising under the Fair

Housing Act. IcL at 75. But that does not mean that this Court can therefore

adopt the per se rule proposed by FHP. Indeed, all it means is that FHP’s

argument, based as it is on prudential considerations, is irrelevant.

The real issue here is whether FHP satisfies the constitutional

requirements for standing. Article III of the Constitution requires at a

minimum that there be a case or controversy, which means that "in every case,

the plaintiff must be able to demonstrate: ‘[a]n "injury in fact" - an invasion of

a judicially cognizable interest which is (a) concrete and particularized and (b)

6

actual or imminent, not conjectural or hypothetical . . . . ’" IcL at 74, quoting

Warth, 422 U.S. at 560-61 (emphasis in original). As this Court itself

emphasized, there is no constitutional basis for standing unless in each

particular case there is injury in fact.

Thus, there can be no per se rule by which all fair housing organizations

automatically have the right to bring housing discrimination claims in federal

court. There must be an individualized determination of injury in fact ~ that

"‘as a result of the defendant’s action [plaintiff] has suffered a distinct and

palpable injury.’" IcL. at 75, quoting Havens Realty Corp .,v. Coleman, 455

U.S. 363, 372 (1982). In the specific context of fair housing organizations,

whether there has been distinct and palpable injury turns on whether the

organization’s ability to conduct its operations was perceptibly impaired,

whether there was a consequent drain on its resources. at 75.

Like FHP, the fair housing organization in Montgomery Newspapers

claimed that its resources had been diverted. The Fair Housing Council

("FHC") claimed that it had to divert funds to an education campaign to repair

damage caused by the advertisements. Id. at 76-77. This Court found that

FHC in responding to Montgomery Newspapers’ summary judgment motion

had offered no proof establishing any connection between the particular

7

advertisements and the need for implementation of the remedial education

campaign. Id, at 77. This Court noted that the injury "must result from the

particular discriminatory acts, not from the general conduct of multiple parties

over the course of years." Id, at 77, n.3.

FHP made precisely the same type of unsupported assertion in

responding to the Rigas’ summary judgment motion in this case, generically

claiming that it would have to engage in outreach to counteract the effect of

discrimination "such as" Mrs. Riga’s conduct. See Affidavit of Andrea Blinn

attached to FHP’s Brief in Opposition to the Rigas’ Summary Judgment

Motion. (A ll, Docket Entry 45). No evidence was offered of any steps

actually taken by FHP and no evidence was offered to demonstrate that even if

such steps had been taken, they would have been taken as a direct result of

Mrs. Riga’s particular discriminatory acts as opposed to the general conduct of

multiple parties in the Squirrel Hill area of Pittsburgh.

At trial, FHP offered some proof of outreach but never offered any proof

that it was a direct result of Mrs. Riga’s conduct. (A669, A673). And the

outreach described was quite general ("We went out and talked to persons in

surrounding communities . . . to educate them about the fair housing laws ) and

was so unrelated to Mrs. Riga’s conduct that FHP did not even include the cost

8

of the staff time in calculating the damages it sought. (A673). In any event,

evidence offered at trial has no bearing on whether FHP offered adequate

evidence to survive summary judgment at the time that motion was filed and

decided. Because the elements of standing are "an indispensable part of the

plaintiffs case, each element must be supported in the same way as any other

matter on which the plaintiff bears the burden of proof, i. e. with the manner

and degree of evidence required at the successive stages of the litigation."

Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife. 504 U.S. 555, 561 (1992), quoted in

Montgomery Newspapers. 141 F.3d at 76. In order to defeat the Rigas’

summary judgment motion "based on the issue of standing, the FH[P] was

required to submit ‘affidavits or other evidence showing through specific facts .

. . that . . . it [was] "directly" affected [by the alleged discrimination].’"

Montgomery Newspapers. 141 F.3d at 76, quoting Lujan, 504 U.S. at 562

(emphasis added by this Court). FHP failed to prove any such specific facts.

In Montgomery Newspapers. FHC also claimed its resources had been

diverted to investigate the advertisements. Ich at 78. This Court rejected such

a claim of injury, noting that the investigation was nothing more than a review

of newspapers which occurred every day as part of FHC’s normal operations.

Id. Likewise, in the instant case, FHP claims it was damaged because it

9

investigated the Rigas. This Court expressly held in Montgomery Newspapers

that "the pursuit of litigation alone cannot constitute an injury sufficient to

establish standing under Article III." Id ̂ at 80.

FHP offered no evidence in response to the summary judgment motion

indicating that the investigation was independent of the litigation or was

something which was not part of its normal operations. To the contrary, FHP

expressly stated that investigating complaints was one of a variety of methods

by which it "typically" carried out its mission. See Affidavit of Andrea Blinn

attached to FHP’s Brief in Opposition to the Rigas’ Summary Judgment

Motion. (A ll, Docket Entry 45). That FHP spent some time investigating the

Rigas rather than someone else is no different than the fact that FHC staff was

diverted from reading other advertisements because it spent time reading the

false advertisements.

It would be particularly inappropriate to find standing in this case where

any diversion of resources was completely unnecessary and self-inflicted. The

Alexanders had already established the availability of the apartment at issue

before FHP even began its tests to ascertain whether it was available. Thus,

FHP sought to manufacture standing for itself by investigating a question that

the Alexanders had already answered. And the investigation was solely for the

10

purpose of litigation. This is precisely the type of damage which this Court has

held does not confer standing. As with FHC in Montgomery Newspapers,

FHP’s claim to standing in this case "shrinks the Article III standing

requirement to a point where the requisite injury flows automatically from the

burdens associated with filing a lawsuit. Resort to this extreme position simply

is not necessary." JcL at 80. Therefore, the trial court erred when it denied the

Rigas’ Motion for Summary Judgment against FHP.1

C. Evidence Of The Alexanders’ Poor

Credit Was Improperly Excluded.

Relying on the inapposite after-acquired evidence doctrine, the

Alexanders argue that the trial court properly excluded evidence that the

Alexanders were not qualified for the apartment at issue. Reply Brief at 29.

As the Supreme Court case cited by the Alexanders demonstrates, the after-

acquired evidence doctrine typically applies in employment discrimination cases

where an employee has been terminated. See McKennon v, Nashville Banner

Pub. Co.. 513 U.S. 352 (1995). The doctrine addresses the extent to which an

employer can avoid liability for a discriminatory discharge by pointing to after-

1 It is important to note that this Court decided the Montgomery

Newspapers case several weeks after the trial court had ruled on the Rigas’

Motion for Summary Judgment.

11

acquired evidence of misconduct which would have justified firing the employee

had the employer known it. Such evidence does not bar an employee’s claim

(although it may limit the recovery) because at issue is the employer’s motive

for the discharge and information which the employer did not know can have

no bearing on the employer’s motive. See Mardell v. Harleysville Life Ins.

Co.. 65 F.3d 1072, 1073, n .l (3d Cir. 1995).

The after-acquired evidence doctrine has no bearing in this housing

discrimination case, however. The bad credit evidence was not offered to

justify any conduct by the Rigas. The Rigas did not offer the evidence to claim

that the Alexanders were denied access to the apartment for a non-

discriminatory reason. In such a case, the evidence might properly be barred

as irrelevant, since the Rigas did not know of the Alexanders’ credit history at

the time. Rather, the evidence was offered to rebut what the Rigas believe to

be an essential element of the Alexanders’ case - that the Alexanders were

qualified to rent the apartment at issue. Put differently, the bad credit evidence

was not offered to provide the Rigas with an affirmative defense (that what

Mrs. Riga did was acceptable). It was offered to rebut any evidence which the

Alexanders might have offered to meet their burden of proving that they were

qualified. For reasons articulated in their initial brief, the Rigas believe that the

12

Alexanders had the burden of proving that they were qualified for the apartment

and the trial court abused its discretion in excluding evidence proving the

opposite.2

D. The Trial Court Abused Its Discretion In Excluding

Evidence Bearing On The Alexanders’ Credibility.

Just as FHP ignored the troublesome issue of Article III standing

requirements, mistakenly focusing on prudential considerations, the Alexanders

ignore Rule 608 of the Federal Rules of Evidence, mistakenly focusing on Rule

404(b). The Rigas did not seek to offer evidence of "other crimes, wrongs or

acts" under Rule 404(b) nor did they seek to "put character in issue" using

"extrinsic documents" as the Alexanders assert. Reply Brief at 30. Rather,

they sought to question Mr. and Mrs. Alexander on cross-examination about

specific prior instances of dishonesty for the purpose of probing their character

for truthfulness or untruthfulness. Rule 608(b) plainly permits such inquiry.

The Alexanders argue only that such evidence was "extremely prejudicial

and not relevant." Reply Brief at 30. Evidence regarding credibility is always

2 The Alexanders argue that Chauhan v. Alfieri, 897 F.2d 123 (3d Cir.

1990) is inapposite. Reply Brief at 29. The Rigas do not cite Chauhan for any

factual similarities. Instead, the Rigas cite Chauhan because in that case this

Court noted that a plaintiff in a rental discrimination case must prove he is

qualified to rent the property at issue.

13

relevant and was particularly critical here, where Mrs. Riga asserted that the

Alexanders lied when they claimed to have visited the property at issue. The

real issue is whether the inquiry’s prejudicial impact so outweighed its probative

value as to require that it be excluded. But the Alexanders offer no analysis of

this issue, presumably because the only "prejudice" the Alexanders would have

suffered as a result of this inquiry would have been to expose their mendacious

propensities. Although this certainly would have damaged the Alexanders’

case, it would hardly be unfair.

Rule 608 is subject to the balancing requirements of Rule 403 of the

Rules of Evidence. See U.S. v. Atwell. 766 F.2d 416 (10th Cir. 1985). Rule

403 permits relevant evidence to be excluded "if its probative value is

substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice, confusion of the

issues, or misleading the jury, or by considerations of undue delay, waste of

time, or needless presentation of cumulative evidence." Fed. R. Evid. 403. It

is important to bear in mind that Rule 403:

does not offer protection against evidence that is

merely prejudicial, in the sense of being detrimental to

a party’s case. Rather, the rule only protects against

evidence that is unfairly prejudicial. Evidence is

unfairly prejudicial only if it has ‘an undue tendency to

14

suggest decision on an improper basis, commonly,

though not necessarily, an emotional one.’

Carter v. Hewitt. 617 F.2d 961, 972 (3d Cir. 1980) (emphasis in original),

quoting Advisory Committee’s Note, Fed. R. Evid. 403.

The proposed questioning concerned lies to potential employers and

providers of goods and services (see the Rigas’ opening brief at 45). It

concerned matters which were legitimately probative of the Alexanders’

truthfulness, yet without characterizing them as evil people. In other words,

there was no risk that a jury’s perception of the Alexanders would be unfairly

skewed. There was no prejudice unless that concept is defined as meaning that

a jury might conclude the Alexanders were lying. But such a definition would

eviscerate Rule 608. Given the central importance of credibility in this case,

the Rigas sought to question the Alexanders on matters whose probative value

far outweighed any prejudice. For these reasons, the trial court abused its

discretion when it excluded evidence that impugned the Alexanders’ credibility.

III. CONCLUSION

The District Court’s Order dated March 10, 1998 should be reversed and

remanded with directions to enter summary judgment in favor of the Rigas and

against Plaintiffs, together with costs. Alternatively, the District Court’s

15

Judgment and Order dated October 9, 1998 should be affirmed in all respects

with one exception: Plaintiffs should be required to pay the Rigas’ costs. If a

new trial is ordered, the District Court’s decision excluding the Rigas’ proffered

evidence regarding credit history and credibility should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Thbmas M. flardiman

Pa. I.D. #65252

Joseph P. McHugh

Pa. I.D. #77489

TITUS & MCCONOMY LLP

Firm #662

Twentieth Floor

Four Gateway Center

Pittsburgh, PA 15222

(412) 642-2000

DATED: August 16, 1999 Counsel for Cross-Appellants

16

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

The undersigned certifies that this Reply Brief is in compliance with the

type-volume limitations of Fed. R. App. P. 32. It is in non-proportional 14-

point font and contains 3309 words.

Joseph P. McHugh

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned, counsel for Appellees/Cross Appellants Joseph and

Maria Riga, certifies that he served a copy of the foregoing Reply Brief of

Cross Appellants this 16th day of August 1999 by First Class Mail, postage

prepaid, addressed to:

Counsel

Caroline Mitchell, Esquire

3700 Gulf Tower

707 Grant Street

Pittsburgh, PA 15219-1913

Timothy P. O’Brien, Esquire

1705 Allegheny Building

429 Forbes Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

Charles Stephen Ralston, Esquire

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

Rebecca K. Troth, Esquire

Department of Justice

P. O. Box 66078

Washington, D.C. 20035-6078

Parties Represented

Ronald and Faye Alexander

Fair Housing Partnership of

Greater Pittsburgh

Amicus Curiae NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

Amicus Curiae Department of

Justice