Uzzell v. Friday Brief for Additional Defendants-Appellees

Public Court Documents

November 10, 1978

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Uzzell v. Friday Brief for Additional Defendants-Appellees, 1978. e9c344f8-c79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b39029e5-ca2b-4a06-803b-605324cdae6b/uzzell-v-friday-brief-for-additional-defendants-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

' :

VV

\"

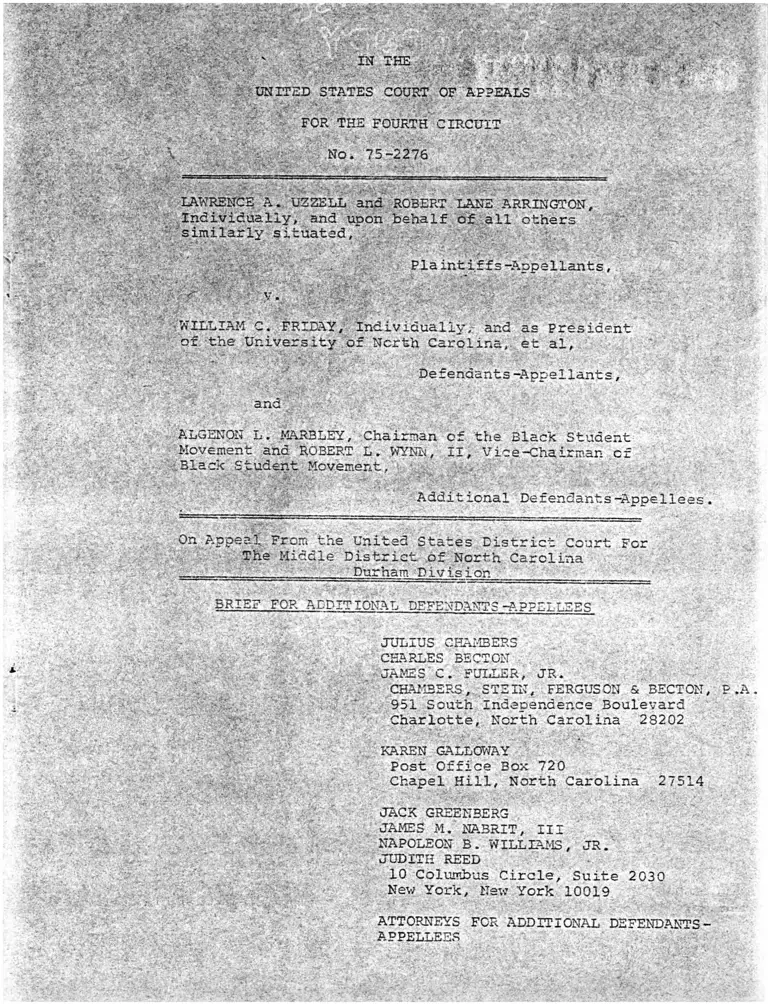

. IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS m

«r ' \

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 75-2276

LAWRENCE A. UZZELL and ROBERT LANE ARRINGTON,

Individually, and upon behalf of all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

■ WILLIAM C. FRIDAY, Individually,- and as President

of the University of North Carolina,, et al,

Defendants-Appellants,

and

ALGENON L. MAR3LEY, Chairman of the Black Student

Movement and ROBERT L. WYNN, II, Vice-Chairman cf Black Student Movement, .v_,\

Additional Defendants-Appellees

On Appeal' From the United States District Court For

The Middle District of North Carolina

.. . ' Durham Division__________ _____

BRIEF FOR ADDITIONAL DEFENDANTS -A.PPT~7T.F.F.q

JULIUS CHAMBERS

CHARLES BECTON

JAMES C. FULLER, JR.

CHAMBERS, STEIN, FERGUSON & BECTON,

951 South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

'KAREN GALLOWAY

Post Office Box 720

Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27514

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M . NA3RIT, III

NAPOLEON B. WILLIAMS, JR.'

JUDITH REED

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

ATTORNEYS FOR ADDITIONAL DEFENDANTS - APPELLEES

P .A.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Challenged University Provisions ................... viii

Statement of Issues Presented

I. Whether the Prior Racial Discrimination

Against Blacks at the University of

North Carolina Constitutes A Justifica-

i tion for the University's Remedial, Race-

Conscious Policies Concerning the Student

Honor Court and the Campus Governing Council?

II. Whether the Attempt of the University of North

Carolina to Bring Itself Into Compliance with

Title VI and Orders of HEW Permits the Univer

sity to Use the Race-Conscious Remedial Measures

Challenged Here?

III. Whether the Interests of the University in

Fostering Diversity and in Providing A Fair

Trial for Its Students Constitute Sufficiently

Compelling Governmental Interests Justifying the University's Use of Remedial, Race-Conscious

Measures?

IV. Whether this Action Should Be Remanded to the

District Court for Further Fact-Finding?

V. Whether this Court Should Dismiss this Action

Because of Plaintiffs' Lack of Standing and

the Lack of Injury Caused to Others by the

University's Policies Challenged in this Action?

Statement Of The Case ............................... 1

Statement Of Facts .................................. 3

ARGUMENT

I. THE JUDGMENT OF THE DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

DEFENDANTS SHOULD BE AFFIRMED ................. 7

l

II.

A. The Criteria Established by the

United States Supreme Court in

Regents of the University of

California v. Bakke Govern the

Disposition of This Action ................

B. The Prior History of the University

of North Carolina and of the State

of North Carolina in Discriminating

Against Black Students and Inhabi

tants Constitutes a Necessary and

Sufficient Condition For the Insti

tution of the University's Race- Conscious Remedial Programs ...............

C. The-University's Programs Insuring

Adequate Representation of Different

Racial Groups on the Campus Governing

Council and the Student Honor Court

Are Constitutionally Permissible As

Means For Insuring Diversity ...............

AS AN ALTERNATIVE WAY OF DECIDING THE

COMPLEX AND PERPLEXING ISSUES RAISED

IN THIS CASE, THE COURT SHOULD REMAND

THE ACTION TO THE DISTRICT COURT FOR

FURTHER FACT FINDING AND DEVELOPMENT

OF THE RECORD ...............................

A. Defendants Are Entitled to Have the

District Court Weigh the Evidence

of Prior Racial Discrimination By the

State of North Carolina and the Uni

versity of Northat Carolina at Chapel Hill ......................................

B. A Remand is Appropriate for the Taking of

Evidence On the Extent to Which the Uni

versity's Programs Respecting the Composi

tion of the Campus Governing Council and

the Student Honor Court Furthers the University's Interest in Diversity ...........

C. Defendants Are Entitled Under Bakke to

Present Additional Evidence Concerning Other

Interests Which the University Has for Insti

tuting and Maintaining Its Race-Conscious

Programs ..................................

Page

10

24

42

46

46

48

49

- l i

Page

III. THE STANDARDS OF ELEMENTAL DUE PROCESS RE

QUIRE A REMAND OF THIS ACTION IN ORDER TO

ALLOW DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES THE OPPORTUNITY

OF A TRIAL ON THE MERITS ................... 51

IV. THIS ACTION SHOULD BE DISMISSED BECAUSE OF

THE LACK OF INJURY TO PLAINTIFFS AND OTHERS.. 53

CONCLUSION .......................................... 57

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

- iii -

Table of Cases

Cases Pages

Adams v. Richardson,

356 F. Supp. 92 (D.C.D.C. 1973),Modified, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973) ... 26,27,28,29,47

Alex v. Allen,

409 F. Supp. 379 (W.D.Pa. 1976) ......... 33

Armstrong v. Board of Education of City

of Birmingham, 323 F.2d 333 (5th Cir. 1963).. 33

Associated General Contractors of

Massachusetts, Inc. v. Altschuler,

490 F. 2d 9 (1st Cir. 1973) ............. 41

Bakke v. Regents of the University of

California, 18 Cal. 3d 34, 132 Cal.

Reptr. 680, 553 P.2d 1152 (1976), rev'd.

sub nom. Regents of the University of

California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. ____,

98 S.Ct. 2733, 57 L.Ed. 2d. 750 (1978) ..... 14

Borden's Farm Products Co. v. Baldwin,

293 U.S. 543 (1934) ........................ 52

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Bridgeport

Civil Service Commission, 482 F.2d 133

(2nd Cir. 1973).............................. 41

Broussard v. Patton, 446 F.2d 816 (D.C.D.C.

1975) ...................................... 29

Carter v. Gallagher,

452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971),

Modified on rehearing en banc,

452 F. 2d 327 (8th Cir. 1971)................ 41

Chastleton Corp. v. Sinclair,

264 U.S. 543 (1924)......................... 52

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania

v. Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3d Cir.

1971), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 954 (1971) .... 41

Craig v. Boren,

429 U.S. 190 (1976) ........................ 52

iv

Crane v. Sun Insurance Office, Ltd.

375 F. 2d 670 (4th Cir. 1962) ............. 51

Dabney v. Cunningham,

317 F. Supp. 57 (E.D. Va. 1970) ......... 51

Doe v. Bolton,

410 U.S. 179 (1973) ..................... 55

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City

Public Schools, 244 F. Supp. 971

(W.D. Okla. 1965), aff'd. in part.

Board of Education of Oklahoma City

Public Schools Independant District

No. 89 v. Dowell,

375 F.2d 158 (10th cir.1967), cert.

denied, 387 U.S. 931 (1967) ........... 33

Frasier v. Board of Trustees of the University

of North Carolina, 134 F. Supp. 589(M.D.N.C. 1955)........................... 25,29,30,46,47

Granader v. Public Bank,

417 F.2d 75 (6th cir. 1969), cert.

denied, 397 U.S. 1065 (1970) ............. 29

Griswold v. Conn cticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) 55

Lambert v. Conrad,

308 F. 2d 571 (9th cir. 1971) ............ 29

Lau v. Nichols

414 U.S. 563 (1974) ....................... 55

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co.,

427 U.S. 273 (1976) .....................

McKissick v. Carmichael,187 F. Supp. 949 (4th Cir. 1950) ....... 47

Nader v. Allegheny Airlines, Inc.,

512 F . 2d 527 (D .C .D .C . 1975) ............... 29

Nashville; Chattanooga & St. Louis Ry. Co. v.

Walters, 294 U.S. 405 (1935) .............. 52

Paul v. Dade County,419 F.2d 10 (5th Cir. 1969), cert denied,

397 U.S. 1065 (1970) ...................... 29

v

Planned Parenthood of central Missouri

v. Danforth, 423 U.S. 52 (1976) ......... 52

Polk v. Glover,

305 U.S. 5 (1938) ....................... 52

Regents of University of California v.

Bakke, 438 U.S. ____, 98 S.Ct. 2733,57 L .Ed. 2d, 750 (1978)................... passim

Schlesinger v. Reservists Committee to

Stop The War, 418 U.S. 208 (1974)........ 19

Soglin v. Kaufmann,

295 F. Supp. 978 (W.D. Wis. 1968) aff'd,418 F. 2d 163 (7th Cir. 1969 ) ........ 40

Swain v. Alabama,

308 U.S. 221 (1965) ..................... 21,22

Swann v. Charlotte - Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ........... 30,47

Sweatt v. Painter,

339 U.S. 629 (1950) ..................... 48

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance

CO., 409 U.S. 205 (1972)................. 55

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey,

430 U.S. 144 (1977) ..................... 41,55

United States v. City of Jackson,

318 F.2d 7 (5th Cir. 1963), rehearing

denied, 320 F.2d 870 (5th Cir. 1963.).... 39

United States v. Griffin,

525 F. 2d 710 (1st cir. 1975)............. 32

United States v. Grimes,

299 F. Supp. 289 (N.D. Ga. 1964)......... 32

Uzzell v. Friday, 401 F.Supp 775 (M.D.N.C.

1975), aff'd in part, rev'd. in part,

547 F.2d 801 (4th Cir. 1977)aff'd on rehearing, 558 F.2d 727 (1977) ........ 1,2

Warth v. Seldin,

422 U.S. 490 (1975) .................... 19,53,54,55

vi

Weaver v. Palmer Bros, Co.

270 U.S. 402 (1976).......................... 52

Weber v. Aetna Casualty & Surety Co.

406 U.S. 164 (1972) .......................... 18

Wheeler v. Durham Board of Education,

326 F. 2d 759 (4th Cir. 1964).................. 30'

- V i l -

CHALLENGED UNIVERSITY PROVISIONS

University of North Carolina Student Constitution, Art. I §1.A-D

ARTICLE I . LEGISLATURE

§ 1. CAMPUS GOVERNING COUNCIL

A. Supreme legislative power in the Student Body is

vested in a Campus Governing Council (hereinafter

referred to as "Council.")

B. COMPOSITION. The Council shall be composed of 20

elected Councillors, the President of the Student

Body as a voting ex-officio member, and not to

exceed four appointed Councillors if necessary to

comply with Section l.D. of this A.rticle.

C. ELECTION. The elected members of the Council shall

be chosen during the election in the Spring Semester,

to serve one year, and until their successors are

elected.

D. MINORITY REPRESENTATION. To ensure there be a pro

tective representation of minority races and both

sexes on the Council, at all times there shall be at least two Councillors of a minority race within the

Student Body (if any), two male Councillors, and two

female Councillors. If at any time the requirements

of this section are not fulfilled, the President of

the Student Body, with the consent of the Council,

shall make the number of appointments necessary to

ensure compliance with this section, PROVIDED that

any such appointment shall take effect unless re

jected by the Council within 10 days of submission.

All appointed Councillors shall have the same rights,

privileges, and duties of elected Councillors and

shall serve for the remainder of the term of the

Council. No appointments made necessary by the

results of a Spring Election shall be submitted to

other than the Council newly elected.

viii

The Instrument of Judicial Governance For the University of

North Carolina at Chapel Hill, IV, E.2.e.(2):

IV. E. 2. e. 2) If requested by the defendant, provision

made for racial or sexual representation (but

not both) on the trial court, as follows:

a) At least four of the seven members of the

trial could shall be of the same sex as

the defendant;

b) When a defendant is not a member of the

majority race, at least four of the seven

members of the trial court shall not be of

the majority race;

c) When a defendant is a member of the majority

race, at least four of the seven members of

the trial court shall be of the majority race.

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED

I. Whether the Prior Racial Discrimination Against Blacks

at the University of North Carolina Constitutes A

Justification for the University's Remedial, Race-

Conscious Policies Concerning the Student Honor Court

and the Campus Governing Council?

II. Whether the Attempt of the University of North Carolina

to Bring Itself Into Compliance with Title VI and Orders

of HEW Permits the University to Use the Race-Conscious

Remedial Measures Challenged Here?

II. Whether the Interests of the University in Fostering

Diversity and in Providing A Fair Trial for Its Students

Constitute Sufficiently Compelling Governmental Interests

Justifying the University's Use of Remedial, Race-Conscious

Measures?

TV. Whether this Action Should Be Remanded to the District Court

for Further Fact-Finding?

V. Whether this Court Should Dismiss this Action'Because of

Plaintiffs' Lack of Standing and the Lack of Injury Caused

to Others by the University's Policies Challenged in this

Act ion?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case is before this Court on remand from the United

States Supreme Court. The Supreme Court vacated this Court's

previous judgment and remanded the case to this Court for further

consideration in light of Regents of University of California v.

Bakke_, 438 U.S. ____, 98 S.Ct. 2733, 57 L.Ed.2d 750 (1978)

(hereinafter cited as "Bakke").

Plaintiffs commenced this action on June 15, 1974, in the

United States District Court for the Middle District of North

Carolina. Asserting three claims for relief, plaintiffs sought

declaratory and injunctive relief against defendants with re

spect to three practices of the University of North Carolina

alleged to violate the Fourteenth Amendment, the Civil Rights

Act of 1871, 42 U.S.C. §1983, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

Title VI, 42 U.S.C. §2000d. The plaintiffs sought class certi

fication of this action. On defendants' motion to dismiss, or

in the alternative for summary judgment, the district court

awarded judgment for defendants. Uzzell v. Friday. 401 F.Supp.

775 (M.D.N.C. 1975). On appeal by the plaintiffs, this Court

affirmed summary judgment in favor of the defendants as to

plaintiffs' first claim; however this Court reversed the judg

ment below on plaintiffs' second and third claims and awarded

judment with respect to those claims to the plaintiffs. Uzzell

v. Friday. 547 F.2d 801 (4th Cir. 1977). Judgment was awarded

as to the named plaintiffs only.

1

Upon timely petition for rehearing this Court, sitting

in banc, affirmed, with certain modifications not relevant here

its previous decision. Three judges dissented. Uzzell v.

Friday. 558 F.2d 727 (1977).

Defendants on January 24, 1977, timely petitioned the

United States Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari to review

the judgment of the court. The petition was granted and on

July 3, 1978, the Supreme Court issued a writ vacating the judg

ment of this Court and remanding the case to this Court for

further consideration in light of 3akke, supra.

Following the remand, plaintiffs, by motion dated July 14,

1978, moved this Court to expedite briefing and oral argument

in this case. Defendants filed a response opposing the motion

and further moved to have the case remanded to the district

Court or to be dismissed. This Court thereupon set this case

for oral argument on November 16, 1978, directing the parties

to submit briefs by November 13, 1978.

2

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The plaintiffs are two white males who were in attendance

at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (hereinafter

the "University") at the time of filing their complaint. They

seek in this action to challenge the validity of certain practices

authorized by the University. The first claim for relief, now

mooted, concerned the validity of the University's funding of the

Black Student Movement, a campus group whose constitution alleged

ly restricted membership of the group to black students. During

the pendency of the action, the group's constitution was amended

to open its membership to students of all races. Accordingly,

judgment was entered by the district court, and affirmed on appeal,

dismissing plaintiffs' cause of action regarding this group.

Plaintiffs, in their second claim, challenged a specific

regulation of the University, set forth in the university of

North Carolina Student Constitution, Article I §1.A-D, which pro

vides for racial and sexual representation on the Campus Govern

ing Council (CGC), the student legislative body. Pursuant to

that regulation, the President of the student body, with the

consent of the Campus Governing Council, is directed to make

appointments to the Council to insure that one third of the Council

is composed of black students and one third is composed of female

3

students. This mandate, however, is effective only if elections

fail to produce the above mentioned result Plaintiffs challenge

the validity of these regulations, claiming that they discrimin

ate against plaintiffs on account of their race.

Plaintiffs' third claim for relief concerns the validity

of provisions of the University's Instrument of Judicial Govern

ance For the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, IV,

E.2e(2), which allows for racial and sexual representation on

the Student Honor Court, the judicial arm of the Student govern

ment. The Student Honor Court tries cases involving student dis

ciplinary actions. The Instrument of Judicial Governance states

that a defendant appearing before this student court may request

that four of the seven judges be members of his or her own race

or sex, if such representation is not already part of the Court.

Plaintiffs also claim that this Instrument discriminates against

them because of their race.

The brief record developed thus far discloses some of the

reasons for the institution of these provisions. One stated

purpose of the first provision is to ensure that, in a student

body that is overwhelmingly white and male, minorities and females

will be represented on the Campus Governing Council thus, making

certain that the legislative body will be representative of the

4

various "diverse groups on campus" (Epps. Aff.) Another purpose

to be established in the record is to bring the University into

compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. §2000d and the Fourteenth Amendment. This

provision'was approved in September 1972 as part of a student

referendum. The second provision, relating to the Honor Court,

was effectuated by vote of the student body in "response to a

perception, particularly among minority students, that the Student

Courts were not providing fair adjudications to all students."

(Stallings Aff., para. 2). This provision must also be regarded

as part of the University's efforts to comply with Title VI of

the Civil Rights Act and the Fourteenth Aemendment.

Plaintiffs have never sought to be judges of the Honor Court;

nor have they been in the position of being an accused before that

Court. Moreover, plaintiffs have never sought membership on the

Campus Governing Council. Since the effective date of the Univer

sity's provision concerning the Council, the President has had

occasion to exercise his powers under those provisions.

With respect to both the Council and the Honor Court, the

additional defendants in this action maintain that the University's

1/ All references to affidavits are to those sworn affidavits

submitted to the District Court on the defendants' motion

for summary judgment. These affidavits also appear in the

Appendix for Appellants previously submitted to this court.

1/

5

provisions are not unlawful, that the University has compelling

reasons to institute such provisions, and that the provisions

are justified by the prior racial discrimination engaged in by

this University and the State of North Carolina against black

students.

6

ARGUMENT

I. THE JUDGMENT OF THE DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

DEFENDANTS SHOULD BE AFFIRMED

This case raises issues that are important in determ

ining the permissible latitude which universities are to

have in remedying adverse racial consequences arising

from a period during which rigid laws and rules prescrib

ing racial segregation governed the conditions of academic

life at universities within the State of North Carolina

and governed the nature of social and political relations

between inhabitants of the State. Moreover, this case

involves the important question of the efficacy which judi

cial and administrative findings of past racial discrimination

by the University of North Carolina and by the State of North

Carolina will have in the implementation of the Supreme

Court's decision in Regents of the University of California

v. Bakke, ___ U.S. ___, 57 L.Ed.2d 750 (1978). Within this

context, resolution of the issues to be decided in this

case will serve to delimit the extent to which admitted

acts and practices of past discrimination against blacks

by the University of North Carolina, as confirmed by judicial

and administrative findings, constitute an adequate basis

upon which the institution of race-conscious remedial measures

7

can constitutionally be founded. Additionally, decision

here will determine to what degree a university's recog

nized interest in obtaining diversity amongst its students

extends to the racial composition of student organizations,

such as the Campus Governing Council and the Honor Court, whose

makeup'and role may otherwise frustrate the realization

of the university's purpose in seeking a diversity of its

student body.

Of course, there are other issues in this case, such

as standing, justiciability, and procedural due process,

which were raised either in the district court or in this

Court. Those issues have not been abandoned. The additional

defendants adhere to the positions on these issues which

they, the State of North Carolina, Judges Winter and Butzner,

and Chief Judge Haynsworth, dissenting, took in this Court's

earlier consideration of this case. in particular, the

additional defendants object to plaintiffs' lack of standing

and to this Court's granting of summary judgment before the

defendants had had an opportunity to present evidence in

justification of the race-conscious remedial programs

attacked here. However, in view of the Supreme Court's

decision to vacate this Court's earlier judgment in this

action and to remand the case for further consideration in

8

light of Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,

supra, the additional defendants have decided, without in

any way relinquishing these earlier defenses and objections,

to focus primarily in this brief on the issues presented

by Bakke, supra, which the Supreme Court has ordered this

Court to consider. This Court, however, retains its plen

ary power to correct its earlier decision and to award

judgment to the defendant based upon both the Supreme Court's

decision in Bakke and the reasoning of the district court

below. The additional defendants strongly urge that the

Court adopt this cause of action. Irrespective, however,

of whether this Court adopts the reasoning of the district

judge below, the judgment of the district court should be

affirmed on the basis of the opinion in Regents of the

University of California v. Bakke, supra.

9

A. The Criteria Established By the United

States Supreme Court in Regents of the

University of California v. Bakke

Govern the Disposition of This Action.

The basic facts in Regents of the University of California

v. Bakke, 438 U.S. ___, 57 L.Ed.2d 750 (1978), can be simply

stated. The University of California Medical School at Davis,

as part of an alleged remedial affirmative action admissions

program,set aside sixteen places in its incoming freshman

class for minority applicants for admission. Minority appli

cants were, under this program, applicants who were black,

Indian, Asian, or Mexican-American. In filling these sixteen

seats, the admissions committee at the Davis' Medical School

assessed the qualifications of minority applicants only in

relationship to the qualifications of other minorities. Allan

Bakke, a white applicant, was denied admission to the Medical

School. Alleging that his denial was based upon his race

and that but for his race, he would have been admitted to

one of the sixteen seats reserved for minority applicants,

Allan Bakke brought suit to compel his admission to the

Medical School. The State of California conceded that it

could not demonstrate that Allen Bakke would not have been

admitted in the absence of the reservation of the sixteen

seats to minority aspirants. Based in part upon this con

cession, the Supreme Court of California held that the

10

admissions program in effect at the Davis Medical School

was in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment's equal pro

tection clause and ordered Allan Bakke admitted. Review

was sought by the State in the United States Supreme Court.

In the Supreme Court of the United States, Justices

Powell, Stevens, Stewart, Rehnquist, and Chief Justice

Burger agreed that Allan Bakke should be admitted to the

Medical School. Their reasons, however, as expressed in

Justice Powell's opinion and in Justice Stevens' opinion,

in which the other three Justices joined, were different.

The latter group of four Justices — Stevens, Burger, Rehnquist

and Stewart — based their holding squarely upon Title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended. They concluded

that Title VI of the Civil Rights Act prohibited, by the

"plain language of the statute," 57 L.Ed.2d 848, the specific

special admissions program operated by the University of

California Medical School at Davis inasmuch as that program

"excluded Bakke from participation in its program of medical

education because of his race," at 5 7 L.Ed.2d 848. In

reaching this determination, those Justices did not construe

the facts of the case as presenting the general question of

whether the use of race was a permissible factor in making

admissions decision. Indeed, they stated categorically that

It is therefore perfectly clear that

the question whether race can ever be used

11

as a factor in an admissions decision

is not an issue in this case, and

that discussion of that issue is inap

propriate, at 57 L.Ed.2d 847.

In view of this posture of the Justices joining the

Stevens' opinion, that opinion offers little guidance on

questions such as are raised here concerning the use of

race-conscious remedial programs by universities engaged

in the process of dismantling a dual school system.

Moreover, Justice Stevens' opinion offers no guidance

whatsoever on the validity of race-conscious remedial

programs under the Fourteenth Amendment. By holding that

a private right of action exists under Title VI and that

the scope of Title VI is broader than the scope of the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,

Justice Stevens was able to decide the issue in Bakke

while obviating the necessity of passing upon the consti

tutional issues. Since five other Justices, including

Justice Powell, held in Bakke that the scope of Title VI

was co-extensive with the scope of the equal protection

clause, the Justices joining in the Stevens' opinion,

being overruled on this point by five Justices, will have

to reach the constitutional questions in future cases

under Title VI concerning race-conscious programs. The

Stevens' opinion in Bakke is, for cases involving the val

idity of race-conscious remedial measures— such as those

presented in the instant case-— of no consequence in com

plying with the Supreme Court's decision in Bakke.

Guidance must instead be sought from the other opinions

rendered in the case.

The opinion by Justice Brennan, in which Justices

White, Marshall, and Blackmun concurred, and the opinion

by Justice Powell, are the critical opinions in the

Supreme Court with respect to the general question of the

validity of race-conscious remedial programs. The

Brennan opinion and the Powell opinion, both based upon

the scope and efficacy of the equal protection clause as

applied to governmental action, hold that the use of

racial classifications and race-conscious programs is not

invalid under either the Fourteenth Amendment or Title VI

of the Civil Rights Act. Both opinions, in fact, set out

criteria by which the validity of such classifications

and programs are to be measured. Since three other

Justices Marshall, white and Blackmun — concurred in

Justice Brennan's opinion, the decision in Bakke holds,

as a minimum, that racial classifications and race—conscious

programs are not per se unlawful. It is precisely this

aspect of the Supreme Court's holding in Bakke that un

doubtedly led it to vacate this Court's earlier judgment

13

which, as a practical matter, had erroneously concluded

that the race-conscious programs adopted by the University

of North Carolina for its Campus Governing Council and

Honor Court were per se constitutionally impermissible.

Indeed, this Court had, in disapproving the University's

programs, cited the decision of the Supreme Court of

California in Bakke v. Regents of the University of California,

18 Cal.3d 34, 132 Cal. Rptr. 680, 553 P.2d 1152 (1976) and

the decision of the Supreme Court in McDonald v. Sante Fe

Trail Transportation Co., 427 U.S. 273 (1976). To the

extent that either case had held racial classifications were

per se unlawful, they must be considered as having been

overruled by the Supreme Court in its Bakke decision.

In moving beyond this narrow area of concurrence between

the Powell opinion and the Brennan opinion in Bakke for

the purpose of ascertaining the nature and scope of race

conscious programs and classifications which are held

constitutional under Bakke, some attention must be given,

in order to facilitate a clear presentation of the signifi

cance of the Bakke decision, to the differences of views

between Justices Brennan and Powell.

The Brennan opinion and the Powell opinion concur in

the overall judgment that racial classifications are not

per se unlawful either under Title VI of the Civil Rights

14

Act or under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Moreover, both Justices, as well as the three

Justices joining in the Brennan opinion, agree that remed

ial race-conscious programs may be constitutional and

that their validity is determined by the scope and nature

of the governmental interests advanced in their support.

Justices Powell and Brennan did not agree, however, on

the formulation to be used in expressing the criteria by

which the legitimacy of the interests, and therefore the

legitimacy of race-conscious programs, was to be determined.

Justice Powell held that a racial classification

made by a government is justifiable if the government

demonstrates that

its purpose or interest is constitution

ally permissible and substantial, and

that its use of the classification is

'necessary... to the accomplishment' of

its purpose or the safeguarding of its

interest. at 57 L.Ea.2d 781.

However, Justice Powell also allowed that racial prefer

ences could be justified where

a legislative or administrative body

charged with the responsibility made

determinations of past discrimination

by the...(persons) affected, and

fashioned remedies deemed appropriate

to rectify the discrimination. at

57 L.Ed.2d 778.

15

Justice Powell's analysis seems to treat these two justi

fications as separate and distinct rather than overlapping.

Whether they are distinct or not need not be determined

here. It is sufficient for present purposes to note that,

under Justice Powell's analysis, a government's use of race

conscious measures can be justified either by the existence

of substantial, constitutionally permissible purposes

underlying use of the measures or by the existence of

findings of discrimination made by appropriate governmental

agencies that are plainly adapted to the need to institute

the measures. Since it was not seriously contended in

Bakke, supra, that the Medical School there had ever dis

criminated against any of the minorities favored by its

admission plan, Justice Powell was required to evaluate

the legitimacy of the Davis' admissions program by determ

ining the substantiality, necessity and constitutional

permissibility of the interests which the University ad

vances in support of its admissions program. The particular

interests which he found to be constitutionally permissible

and substantial will be discussed,to the extent that they

are related to the issues raised here on remand, in

subsequent portions of the brief.

Like Justice Powell, justice Brennan also found that

16

race-conscious, remedial admissions programs could be

justified as a result of specific governmental findings

of past, or continuing, discrimination. He seemed to

have conceived this justification, however, as being

merely a specific instance which satisfied a more overall

standard which he believed had been made applicable by

the Supreme Court's previous cases in this area. That

standard was that racial classification "must serve im

portant governmental objectives and must be substantially

related to achievement of those objectives." Bakke, supra,

at 57 L.Ed.2d 814.

The two formulations obviously differ in phraseology.

Perhaps, they even differ in ultimate meaning and signifi

cance. Nevertheless, the two formulations are closely

akin to one another. Both, for example, require a careful

scrutiny of interests purported to be the basis for the

adoption of programs and policies that are based upon

race. Moreover, the underlying purpose behind each

standard is the same. Justice Brennan expressed that pur

pose, in his Bakke opinion, in the following words

While a classification is not per se

invalid because it divides classes on

the basis of an immutable characteristic

...it is nevertheless true that such

divisions are contrary to our deep belief

17

that "legal burdens should bear some

relationship to individual responsi

bility or wrongdoing." at 57 L.Ed.2d

815 (quoting Weber v. Aetna Cas. &

Surety Co., 406 U.S. 164, 175 (1972)).

Thus, the legal disability imposed upon persons innocent of

any wrongdoing is one of the basic reasons for invoking

a close scrutiny of racial classifications. This is

Justice Powell's view also. In his discussion of the ap

plicable standard of review for racial classifications,

he stated

When a classification denies an

individual opportunities or benefits

solely because of his race or ethnic

background, it must be regarded as

suspect." at 57 L.Ed.2d 781.

Thus, for a majority of the Court in Bakke, the degree of

harm caused to innocent persons is a determinant of the

level of scrutiny required to be exercised for racial class

ifications .

It is in this context, as well as with respect to

the defendant's argument that plaintiffs lack standing to

seek the relief they demand, that the absence of any

specific injury to the plaintiffs, caused by the University's

use of a race-conscious, remedial program must be assessed.

The lack of any specific injury to these plaintiffs is

demonstrable. At the time the defendants moved in the

18

district court to dismiss the action or, in the alterna

tive, to grant defendants summary judgment, the original

defendants alleged both that plaintiffs lacked standing

because of the absence of a specific injury and that the

complaint, because of the same lack of harm, failed to

show an actual controversy between the parties such as

required by Article III, §2, of the United States Constitution

and by policy considerations concerning the proper use of

the federal judicial power. See Warth v, Seldin, 422 U.S.

490, 498-501 (1975); Schlesinger v. Reservists Committee

To Stop The War, 418 U.S. 208 (1974). The plaintiffs did

not, in response to this motion of the defendants, allege

and establish the existence of an individualized injury

occurring to either of them by virtue of the University's

race-conscious programs. Nor could any such allegation or

showing have been made.

With respect to the Student Honor Court and the

University's Instrument of Student Jucidial Governance of

1974 which provides that an accused has the right, upon

his or her trial, to demand that four of the seven judges

on the trial bench of the Honor Court be of the same race

or sex of the accused, plaintiffs did not claim that they

19

had presented their candidacies for judgeship on the

Honor Court only to be rebuffed on account of their race.

Nor did the plaintiffs allege that either of them had been

in the position of an accused and that their interests or

rights had been denied them by consequence of the Instrument

of Student Judicial Governance of 1974. Moreover, the

plaintiffs did not offer any evidence tending to show, or

indicate, that blacks, by virtue of the 1974 Instrument of

Student Judicial Governance, had been able to obtain a"juster

justicd' than whites had been able to obtain or that whites

had been denied justice as a result of the implementation

of the Instrument. Similarly, these plaintiffs did not

allege and demonstrate that the provisions of the Student

Constitution requiring the presence of "at least two

Councillors of a minority race...two male Councillors and

two female Councillors" had been used to infringe upon

particular interests of theirs.

The significance of the absence of a particularized

injury, in the context of the Supreme Court's decision in

Bakke, can perhaps best be appreciated by realizing that

the concessions made in Bakke by the University that it

could not be shown that Allan Bakke would not have been

admitted to the Davis' Medical School in the absence of

20

the special admissions program setting aside sixteen

seats for minority applicants, triggered the Court's

rather strict standard of review. Bakke, supra, at 57

L.Ed. 777-781. With respect to a lesser standard of re

view, based upon the reasonableness of the racial classi

fication, the provisions governing composition of the

Honor Court are far less intrusive upon plaintiffs' in

terests, if any, than was true in Alabama of the impact

upon black criminal defendants of the prosecutor's use of

peremptory challenges to exclude blacks from serving on

petit juries. Yet, the prosecutorial practice was upheld

in Swain v. Alabama as a necessary result to be endured

"(i)n the quest for an impartial and qualified jury." at

380 U.S. 221 (1965). The purpose of•the 1974 Instrument was to

insure to blacks an impartial adjudication which they might

otherwise never have received. In the supporting papers

of defendant's motion to dismiss or to grant summary judg

ment, the affidavit of Joseph Henry Stallings, past President

of the Student Body of the University of North Carolina at

Chapel Hill and a past Editor-In-Chief of the North Carolina

Law Review, attests that the provision relating to the

Honor Court, which was introduced by him, was passed by

the Student Legislature for the reason that it was perceived

- 21 -

that the "Student Courts were not providing fair adjudi

cations to all students," especially minority students.

His affidavit further states that the provision permitting

accused students to have members of their race on the

Student Court "would create a greater perception of fairness

in the operations of the Student Courts." Plaintiffs did

not seriously or effectively controvert this showing.

To he sure, the rule allowing peremptory challenges in

Swain v. Alabama, supra, was held reasonable under circum

stances in which the prosecutor could challenge jurors for

reasons other than that they were black. This is not how

ever a sufficient distinction to invalidate a finding of

reasonableness under the Swain v. Alabama, supra, rule

since here too there were other reasons for varying the

composition of the Honor Court, such as sexual representa

tion. Moreover, it must be assumed, in the absence of

allegations to the contrary, that the racial and sexual

composition of the judges on the Honor Court was, during

the transitional time following the University's elimina

tion of racial and sex barriers against blacks and women,

the only significant obstacles to overcome in the operation

of the Honor Court and its "quest for an impartial and

qualified" group of judges. The University ought not to

be penalized, in the absence of any concrete harm to

22

individuals, for taking such limited, reasonable steps

to secure justice when those were the only steps required

to be taken. The same considerations governing the valid

ity of the racial restrictions placed upon the Honor Court

apply with equal force to the rules respecting the racial

composition of the Campus Governing Council since they

were imposed for similar reasons.

In addition to justifying the University'r race

conscious programs under a standard of reasonableness,

which is a lesser standard than that required by Justice

Powell and Brennan when racial classifications impact

upon specific interests of otherwise innocent individuals,

the University1s remedial programs can also be justified

by virtue of the prior discrimination against blacks en

gaged in by the University as well as by the compelling

and important interests referred to by Justices Powell and

Brennan in their opinions in Bakke.

23

B. The Prior History of the University

of North Carolina and of the State

of North Carolina in Discriminating

Against Black Students and Inhabitants

Constitutes a Necessary and Sufficient

Condition For The Institution of the

University's Race-Conscious Remedial

Programs.________________________

In his Bakke opinion, Justice Powell noted, 57 L.Ed.2d at 782,

We have never approved a classifica

tion that aids persons perceived as

members of relatively victimized groups

at the expense of other innocent individ

uals in the absence of judicial, legis

lative, or administrative finding of

constitutional or statutory violations.

Although Justice Powell's granting in Bakke of constitu

tional sanction to admissions plans like that of Harvard Col

lege — in which race is one of the competitive factors

to which a university or college can give consideration —

necessarily implies that the decision in Bakke is a case

in which a racial classification at the expense of inno

cent persons was approved by the Supreme Court in the

absence of governmental findings of racial discrimination,

it is unnecessary here to determine the right of the

University to adopt the measures challenged here without

such findings since both the University and the State which

24

supervises it have practiced extensive racial discrimina

tion against blacks. Moreover, this is a case in which

there are judicial, legislative, and administrative find

ings of discrimination by the State and the University

of North Carolina.

A judicial finding of past racial discrimination was

made against the University of North Carolina in Frasier

v. Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina,

134 F. Supp 589 (M.D. N.C. 1955). The three-judge

district court in Frasier, supra, found that the University

had unconstitutionally discriminated against three black

applicants in connection with their attempts to enroll in

the undergraduate school of the University. The district

court's finding was based upon a resolution of the Board

of Trustees of the University which stated that

The State of North Carolina having

spent millions of dollars in providing

adequate and equal educational facili

ties in the undergraduate departments

of its institutions of higher learning

for all races, it is hereby declared to

be the policy of the Board of Trustees

of the Consolidated University of North

Carolina that applications of Negroes

to the undergraduate schools of the three

branches of the Consolidated University

be not accepted. at 134 F. Supp. 590.

This finding of past racial discrimination satisfies the

- 25

requirement of a governmental finding insisted upon by

Justice Powell and certainly permitted by Justice Brennan

and the three Justices joining in his opinion in Bakke.

The three-judge court also noted in footnote 1 of their

opinion that

Segregation of the races in the public

schools of the state, provided for child

ren between the ages of 6 and 21 years,

is directed by Article IV, Section 2 of

the State Constitution; but the defendants

contend that this provision does not apply

to the University, we need not pass on

this contention because, as we have said,

the Board of Trustees acted under the

authority conferred upon them by the

Constitution and laws of the State when

they excluded Negroes from the under

graduate schools of the University. at

134 F. Supp. 591, n. 1.

Thus, judicial findings exist with respect to discrimina

tion by both the State of North Carolina and the University

of North Carolina.

Additional judicial findings of racial discrimination

by the University of North Carolina and the State of North

Carolina were made in Adams v. Richardson, 356 F. Supp. 92

(D.C. D.C. 1973), modified, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C.Cir. 1973).

In Adams v. Richardson, supra, the district court first

found that the United States Department of HEW had concluded

North Carolina was operating a racially segregated system

26

of higher education in violation of Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000d et seq. Pursuant

to 42 U.S.C. §2000d-2, agency action by HEW, under

42 U.S.C. 2000d, is subject to judicial review in accord

ance with the provisions of the Administrative Procedure

Act, 5 U.S.C. §§701-706. Agency action by HEW with re

spect to a finding of racial segregation by the University

of North Carolina is taken in full recognition of the

right of the State of North Carolina to present opposing

evidence and otherwise enjoy the procedural rights to

which parties affected by agency action are entitled. See 5

U.S.C. §706 (2) (D) , (E) , and (F) . Thus, the finding of

racial segregation made by HEW and referred to in Adams v.

Richardson, supra, satisfies the requisites of due process

and are thus well within the scope of governmental findings

referred to by Justice Powell in his Bakke opinion.

In Adams v, Richardson, supra, the district court also

noted that HEW, prior to February, 1970, requested North

Carolina, by letter, to submit a desegregation plan within

120 days or less, and that North Carolina had failed, for a

period of three to four years, to submit such a desegrega

tion plan. In ordering HEW to commence enforcement action

against North Carolina the district court implicitly found

- 27

that there was sufficient substance to HEW's finding that

the University of North Carolina was maintaining racial

segregation to warrant its order directing HEW to enforce

the provisions of Title VI, §2000d against the State of

North Carolina. Although the Court of Appeals for the

District of Columbia Circuit modified the district court's

order so as to permit HEW to request North Carolina, and

other delinquent states, to file desegregation plans for

higher education within 120 days rather than requiring HEW

to commence enforcement action, that court did not, in its

review of the record, find that there was insufficient

evidence in support of HEW's finding of racial segregation

by the University of North Carolina to warrant directing

HEW to require the submission of desegregation plans by

the University. These judicial findings constitute an ad

equate basis for the University's institution of remedial

programs respecting the composition of the Campus Governing

Council and the Student Honor Court.

The HEW findings of 1970, referred to in Adams v.

Richardson, supra, as well as HEW findings of racial segre

gation and discrimination by the University of North

Carolina, dated May 21, 1977, attached as an Appendix herein,

constitute additional governmental findings of past racial

28

discrimination. Judicial notice of the 1970 HEW findings,

referred to in Adams v. Richardson, supra, can be taken

by this Court since the records in the Adams case are

related to the issues upon appeal here. See Paul v. Dade County,

419 F.2d 10, 11 (5th Cir. 1969); certiorari denied, 397

U.S. 1065 (1970); Granader v. Public Bank. 417 F.2d 75, 82

(6th Cir. 1969), certiorari denied. 397 U.S. 1065 (1970);

Lambert v. Conrad. 308 F.2d 571 (9th Cir. 1971). Judicial

notice of the 1975 and 1977 HEW findings, which are imple

mentations of the Court of Appeals order in Adams v.

Richardson, supra, can be taken on the basis that they are

official orders, proceedings, and acts. See Nader v.

Allegheny Airlines. Inc., 512 F.2d 527, 544 (D.C.CLr. 1975);

Broussard v, Patton. 466 F.2d 816, 820 (9th Cir, 1972),

certiorari denied. 410 U. S. 942, rehearing denied, 411

U. S. 923 (1973) .

The former provisions of Article IX, Section 2 of the

North Carolina State Constitution, referred to in footnote

1 of the district court's opinion in Frasier v. Board of

Trustees, supra, constitute, for purposes of Justice

Powell's opinion in Bakke, a governmental finding, as well

as an admission,of a constitutional and legislative purpose

by the State of North Carolina to discriminate against

29

blacks in the field of education. That constitutional

provision, whose application to higher education in the

State was an issue which the court in Frasier v. Board

of Trustees of the University of North Carolina, supra,

avoided deciding, was made, by its terms, applicable to

students between the ages of 6 and 21 years of age. The age

of twenty-one is the normal age at which graduation from

college occurs. Thus, there is extensive proof of past

racial discrimination against black students by the State

of North Carolina and the University of North Carolina.

As a result of the University's prior racial dis

crimination against blacks, which was part of a massive

and pervasive scheme throughout the State of North

Carolina to deny blacks equal education opportunities,

see Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U. S. 1 (1971); Wheeler v. Durham Board of Education,

326 F.2d 759 (4th Cir. 1964), the institution of special

provisions to insure that blacks, during the transition

from a dual system of education to a unitary system,have

adequate representation on the legislative and judicial

bodies governing the conduct and activities of students

on campus was reasonable and permissible. Indeed, it was

mandatory if necessary to insure an academic environment

30

free of the effects of racial prejudice. Certainly, the

affidavit of Joseph Stallings confirmed that the need to

eliminate the perception that the Honor Court was not

fair to black students was the basis for the provision

allowing an accused before that court to insist that four

out of the seven judges be members of his, or her race.

In extending that privilege to all persons accused, ir

respective of the race ‘of the accused, the student legislature

provided guarantees, that it felt were necessary under the circum

stances, which were least intrusive upon the rights of persons

of whatever race. Thus, the Instrument of 1974 was clearly

reasonable and not excessive. Similarly, Richard Epps,

President of the student body at the University during 197 2-

73, stated in his affidavit that the provision for "minimum

racial and sexual representation" reflected the need to have

a Campus Governing Council that "would be broadly representa

tive of diverse groups on campus." Obviously, a history of

past racial discrimination and segregation at the University

of North Carolina could reasonably be expected, by virtue

of the strong feelings of that part of the student popula

tion harboring racial prejudice engendered as a result of

de jure laws requiring segregation of the races, to create

31

an environment in which blacks might be excluded from the

Campus Governing Council or an environment in which black

defendants before the Honor Court might be exposed to

discriminatory treatment. The possibility of such treat

ment is not unlikely given the extensive nature of the

racial discrimination which occurred at all levels in

North Carolina.

• This Court can take judicial notice of the pervading

nature of the racial segregation which previously existed

in North Carolina. See United States v. Grimes. 299 F. Supp.

289, 294, fn. 3 (N.D. Ga. 1964). Moreover, just as the First

Circuit has taken judicial notice of the fact that enforced

busing in the South Boston public schools received great

publicity and created widespread racial resentment amongst

many citizens, United States v. Griffin, 525 F.2d 710, 711

(1st Cir. 1975), this Court can take judicial notice that

some measure of racial animosity among students may exist as

a result of segregated conditions previously mandated by the

laws of the State of North Carolina. Moreover, this Court

can also judicially notice the substantial probability that

racial friction among students may occur in the throes of

the University's efforts to dismantle a dual system of higher

32

education and convert to a unitary system. See, for

example, Armstrong v. Board of Education of City of

Birmingham, 323 F.2d 333, 361 (5th Cir. 1963), where

judicial notice was taken of the existence of law-abid

ing citizens in Alabama as well as of the existence of

violence and disorder there. See also Dowell v. School

Board of Oklahoma City Public Schools. 244 F. Supp. 971,

975 (W.D. Okla. 1965), affirmed in part, Board of Education

Oklahoma City Public Schools Independent District No.

89 v. Dowell, 375 F.2d 158 (1967), certiorari denied 387

U. S. 931 (1967), where judicial notice was taken of

resistance in all-white communities to blacks who sought

to obtain housing in the communities, and Alex v. Allen,

409 F. Supp. 379, 388 (W.D. Pa. 1976) .

That the possibility of racial friction among students

and with members of the staff of the University is sub

stantial is confirmed by the University's pointed refusal

to provide HEW, pursuant to request, with information re

garding such problems. For example, on pages 15-16 of

the 1975 HEW report, submitted to the Governor of North

Carolina, HEW says that the University's

-33

Semi-Annual Report did not contain the

promised summary of The University's

experience with regard to racial discrim

ination in the area of student access to

facilities and services. When queried

...about this failure... (the University)

...offered no explanation for the omission.

Instead,...(it) summarized the experience

by explaining that The University was

relying on complaints to identify prob

lems in this area and that there had been

no complaints during the reporting period.

HEW concluded, on page 16 of their report, that the University's

"explanation was not sufficient to indicate that The

University acted during the reporting period to fulfill

the promise made in the Plan." In an earlier part of the

HEW report, appearing also on page 15, HEW noted that each

Chancellor of each constituent institution of the University

will be asked to designate a responsible officer to inves

tigate and report on instances of racial discrimination

within the institution.

These considerations are more than adequate to demon

strate that the University, taking reasonable steps to bring

itself within compliance of Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 and acting generally to effect a transition

to a unitary public system of higher education within the

State of North Carolina, employed remedial measures, with

respect to the racial composition of the Campus Governing

Council and the Honor Court, that were precisely tailored

34

to reflect its legitimate interests and that were the

least restrictive means infringing upon the interests of

other persons. Such actions satisfy constitutional re

quirements .

In particular, the remedial, race—conscious measures

adopted by the University satisfy Justice Powell's alterna

tive requirement in Bakke that such measures be based upon

governmental findings of discrimination by the University,

or by society, against the racial group preferred by the

race-conscious program (of course, with respect to the Honor

Court there is no particular racial group preferred by the

1974 Instrument). Judicial findings, such as referred to

herein, of a de jure system of racial segregation created

and maintained by the State of North Carolina are sufficient

findings of societal discrimination to provide constitutional

support for the validity of the University's rules govern

ing the composition of the Campus Governing Council and the

Student Honor Court. These programs obviously satisfy

Justice Brennan's requirement that they "must serve im

portant governmental objectives and must be substantially

related to achievement of those objectives." 57 L.Ed.2d

814.

Moreover, the constitutional right of the University to

impose the rules, challenged here, prescribing the composition

35

As a final point, this Court should note that neither

Justice Powell's opinion in Bakke nor that of Justice Brennan

opposed the use of goals or quotas, stated in racial terms,

when it was justified hy the scope of the prior discrimination.

Bakke, supra, 57 L.Ed.2d at 769-70 and at 57 L.Ed.2d 826-27.

Powell approved, in Bakke, at 57 L.Ed.2d 778-80, quotas- used in

cases such as Bridgeport Guardians, Inc, v. Bridgeport Civil

Service Commission, 482 F.2d 133 (2d Cir. 1973); Carter v.

Gallagher. 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971), modified on rehearing

en banc. 452 F.2d 327 (8th Cir.), certiorari denied, 406 U. S.

950 (1972); Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v.

Secretary of Labor. 442 F.2d 159 (3rd Cir.), certiorari denied,

404 U.S. 954 (1971), Associated General Contractors of

Massachusetts, Inc, v. Altschuler, 490 F.2d 9 (1st Cir. 1973),

certiorari denied, 416 U.S. 957 (1974), and United Jewish

Organizations v. Carey. 430 U.S. 144 (1977). Moreover, these

were cases in which remedial quotas or goals, or ceilings, based

upon race, were used on behalf of persons who had not been the

victims of discrimination.

In short, the University's race-conscious programs assailed

here are substantial, constitutionally permissible and of a

nature which the University can reasonably believe may be

necessary in order to bring it into compliance with the Title VI

and the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

41

C. The University's Programs Insuring

Adequate Representation of Different

Racial Groups on the Campus Governing

Council and the Student Honor Court

Are Constitutionally Permissible As

Means for Insuring Diversity.

In his opinion in Bakke, Justice Powell recognized that

a University has a substantial, constitutionally permissible

interest in the attainment of a diverse student body. Indeed,

as he noted,

the "nation's future depends upon leaders

trained through wide exposure to the ideas

and mores of students as diverse as this

Nation of many peoples." at 57 L. Ed.2d

750.

Diversity thus constituted a substantial contribution to

academic freedom. Since academic freedom was a "special

concern of the First Amendment," Bakke, 57 L. Ed.2d at 785,

Justice Powell concluded that a university's goal in seeking

diversity within its student body was a constitutionally per

missible purpose. As such, he further concluded, the interest

in diversity is a compelling interest justifying race-conscious

programs that permit race to be considered merely as a "plus"

factor in the competition for admission to a university.

In Bakke, the Supreme Court was concerned with a univer

sity's interest in diversity only insofar as it involved

admissions criteria. Hence, the Supreme Court, in Bakke, never

explicitly considered the issue of whether a university's in

42

terest in diversity extended to the racial composition of

student organizations. Obviously, however, a university con

sists of its own sub-organizations as well as student organi

zations. Thus, a university's interest in diversity must, of

necessity extend also to its student organizations. Certainly,

it is impossible to disentangle a university's general interest

in diversity with respect to the composition of its student

body from a more specific interest of the university in diver

sity within the membership and governing councils of student

groups. Obviously, the one impacts upon the other. Accordingly,

it must be concluded that a university has a constitutionally

permissible interest in obtaining racial diversity on the

governing councils of its various student organizations. To

hold otherwise would be to strip Justice Powell's opinion in

Bakke of all meaning and significance. In the instant context,

it is readily apparent that the University has an interest in

diversity of the composition of the governing elements in its

officially sanctioned student organizations. Moreover, the

University has acted to further its interests in diversity.

Of course, the particular type of diversity being pro

moted by the University's race-conscious programs must not be

unreasonable or not tailored to reflect its specific interests

in securing diversity. Moreover, the University's race-conscious

programs would also be vulnerable to challenge if it were shown

43

that they were not, as a practical matter, effective ways of

securing the desired diversity. These avenues of attack,

however, are foreclosed by the nature of the facts in the

instant case as they have been developed in the record.

The importance of the Honor Court lies in its mandate to

do justice. That is its raison d'etre. Secondary to that but

still of paramount importance, the Honor Court is the type of

institution which must be perceived to be doing justice. That

is a critical purpose. It is to this latter purpose that the

affidavit of Joseph Stallings was addressed. In an atmosphere

in which there are significant differences in culture between

racial groups on a campus, it is clearly permissible, especial

ly if it is likely that these differences will impinge upon

an accused's right to a fair trial or will affect the capacity

of the University to insure representation of all groups, for

the University to take steps which it believes are reasonably

necessary to secure justice and fair representation of all.

If diversity of representation on the Honor Court is an effect

ive means of eliminating a differential impact which might lead

to a miscarriage of justice, then rules requiring that diversity

cannot be prohibited.

Moreover, if the absence of such diversity impinges upon

the University's capacity to attract minority students to its

predominantly white campuses at a time when it is under orders

44

from HEW to eliminate its dual educational system for blacks

and whites, then the University has an additional legitimate

purpose for trying to achieve diversity. Lawful attempts to

comply with valid governmental mandates by federal agencies

charged by Congress with the responsibility for enforcing

Title VI can hardly be disallowed. The University's effort

to obtain diversity falls within this category.

45

II. AS AN ALTERNATIVE WAY OF DECIDING THE COMPLEX AND

PERPLEXING ISSUES RAISED IN THIS CASE, THE COURT

SHOULD REMAND THE ACTION TO THE DISTRICT COURT FOR

FURTHER FACT FINDING AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE RECORD.

A. Defendants Are Entitled to Have the District Court

Weigh the Evidence of Prior Racial Discrimination

By the State of North Carolina and the University

of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The opinions by Justice Powell and Brennan demonstrate

that racial classifications are not per se forbidden by statutory

or constitutional law. Justice Powell specifically notes that a

State has a "legitimate and substantial interest in ameliorating,

or eliminating where feasible, the disabling effects of identified

discrimination." Bakke, supra, at 57 L.Ed.2d 782. Justice Brennan's

opinion is to the same effect at 57 L.Ed.2d 816-822. Thus, if the

defendants can show that the use of race in the challenged provisions

is necessary to alleviate the effects of present and prior discri

mination against minorities, they are entitled to prevail. Since,

defendants are entitled under Bakke to make such a showing, they are

entitled to a remand to permit the district court to take evidence

relating to present and prior racial discrimination against blacks

caused by the University. Unlike the University of California at

Davis, whose medical school opened in 1968, the University of North

Carolina has been in continuous,existence ever since the year 1795.

During most of this time, it functioned within a system of de_ jure

discrimination. Moreover, it had itself an official policy of dis

crimination. See Fraiser v. Board of Trustees of the University

of North Carolina, supra.

46

Both Justices Brennan and Powell dis-cuss, in Bakkef the

school desegregation cases in the Supreme Court as authority for

the position that racial classifications are valid where they are

"designed as remedies for the vindication of constitutional entitle

ment." 57 L.Ed.2d at 777-78, and 816-17. One of the very first

cases so cited, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education.

402 U.S. 1 (1971), involved the elementary and secondary school

system of two North Carolina communities. Justice Powell notes

that these cases are "judicial determination^] of constitutional

violation." Id_. at 778. In light of the mandate of the Supreme

Court to consider this case in light of the decision in Bakke, the

district court must be afforded an initial opportunity to take evi

dence on the existence of such judicial determinations of discrimi-

J ._ /nation by the University.

As proof of the existence of racial discrimination at the

University of North Carolina, the additional defendants intend to

introduce into evidence findings made by HEW since 1970. These

findings satisfy Justice Powell's requirement in Bakke that "a

governmental body must have the authority and capability to es

tablish, in the record, that the classification is responsive to

identified discrimination", at 57 L.Ed.2d 783. The findings, of

HEW, included here in an Appendix, show that the University has

discriminated in the past against blacks.

1 / See McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F.2d 949 (4th Cir. 1950),

Frasier v. Bd. of Trustees, 134 F.Supp. 589 (M.D.N.C. 1955).

For more recent, ongoing litigation involving the school

system of the State of North Carolina, see Adams v. Richardson,

480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973).

47

A remand for trial below is necessary to give the district

court an opportunity to examine such evidence.

B. A Remand Is Appropriate for the Taking of Evidence

On the Extent to Which the University's Programs

Respecting the Composition of the Campus Governing

Council and the Student Honor Court Furthers the

University's Interest in Diversity.

During the trial on the merits in Bakke. the Medical School

attempted to justify its remedial use of race in its admissions pro

gram by alleging that its program served the interest of attaining a

diverse student body. Justice Powell found that this purpose was

"clearly a constitutionally permissible goal," 57 L.Ed.2d at 781.

Because of the summary nature of this court's earlier disposition

of this action, the defendants have not been afforded an opportunity

to demonstrate the manner in which the challenged provisions contri

bute to diversity with the University.

Recognition by the Supreme Court of the importance of di

versity in an academic setting is long standing. In Sweatt v .

Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950), which was quoted in Bakke, 57 L.Ed.2d

at 786, the Supreme Court emphasized that a law school's effective

ness at training future lawyers was a function of the extent to which

it interacted with persons who had an impact upon the law and its

development. Sweatt v. Painter, supra, 339 U.S. at 634. Not only

was the importance of diversity in an educational setting acknowledged

generally by Justice Powell in his Bakke opinion, .it was also speci

fically noted that the interest in diversity, though powerful at

a qraduate school level, holds an even greater sway at the under-

1 /

graduate level. Bakke, 57 L.Ed.2d at 786.

2_/ The President of Princeton University has recognized that the valuable interaction that takes place where the student body

is diverse occurs in a variety of ways. "For many, however,

- 48 -

In the record developed below, the Stallings Affidavit,

paragraph 2, indicates that the reason for establishing the pro

vision for racial representation on the Honor Court; was to eliminate

a common, damaging perception of injustice committed by that court

in its adjudications. It can be shown that such perceptions, if not

reversed, can frustrate the University's efforts to create diversity.

The Epps Affidavit states that one of the reasons behind

the Campus Governing Council provision is to ensure that the diverse

groups on campus will be represented in the student body that makes

rules governing the affairs of students. Thus, the interest behind

this provision, as is true of the interest behind the provision con

cerning the Honor Courts is one recognized as being constitutionally

permissible by Justice Powell in Bakke.

If this Court orders a remand of the action to the district

court for further fact finding, then the defendants will be able to

demonstrate the extent to which the provisions regarding the Honor

Court and the Campus Governing Council further the permissible and

substantial interest of the University in maintaining a diverse

student body.

C. Defendants Are Entitled Under Bakke to Present

Additional Evidence Concerning Other Interests

Which the University Has For Instituting and

Maintaining Its Race-Conscious Programs.

Besides its interest in remedying the effects of past dis

crimination by the University and furthering diversity, the University

has other compelling legitimate interests in maintaining its race-con-

2/ Continued

the unplanned, casual encounters ... in class affairs or student

government can be subtle and yet powerful sources of improved

understanding and personal growth." Quoted in Bakke, 57 L.Ed.2d at 785, n.48 [emphasis added].

49

scious programs. For example, the University has an interest in

bringing itself into compliance with the HEW orders and findings.

See Appendix attached hereto. Additionally, the University has

an interest of insuring that students tried before the Honor Court

are able to obtain justice before a panel of impartial judges.

With respect to these interests and others, defendants deserve an

opportunity to present evidence to the district court. Upon re

mand, defendants can also present evidence to show that the extent

of the University's race-conscious programs is commensurate with

the scope of the University's legitimate interests. These con

siderations warrant a remand of the action to the district court.

50

III. THE STANDARDS OF ELEMENTAL DUE PROCESS REQUIRE A REMAND

OF THIS ACTION IN ORDER TO ALLOW DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES

THE OPPORTUNITY OF A TRIAL ON THE MERITS

Courts must use their power to grant summary judgment

sparingly so "that the appellee is not deprived of a trial of

a genuine issue of material fact underlying his claim or defense."6

Pt.2 Moore's Federal Practice K56.27 [2] at 56-1562. This was precisely

the vice with this Court's judgment vacated by the Supreme Court.

By moving for summary judgment on the grounds of mootness, plaintiffs'

lack of standing, and lack of justiciability, defendants did not

thereby concede that there were no triable issues of facts with

respect to those matters on which plaintiffs were required to prevail.

Crane v. Sun Insurance Office, Ltd.. 375 F.2d 670 (4th Cir. 1962).

Despite the fact that the district court did not reach the merits

but decided the action on grounds of mootness, justiciability, and

lack of concrete injury to the plaintiffs, this Court decided the

case on the merits adversely to defendants.

In light of the issues raised previously by the defendants