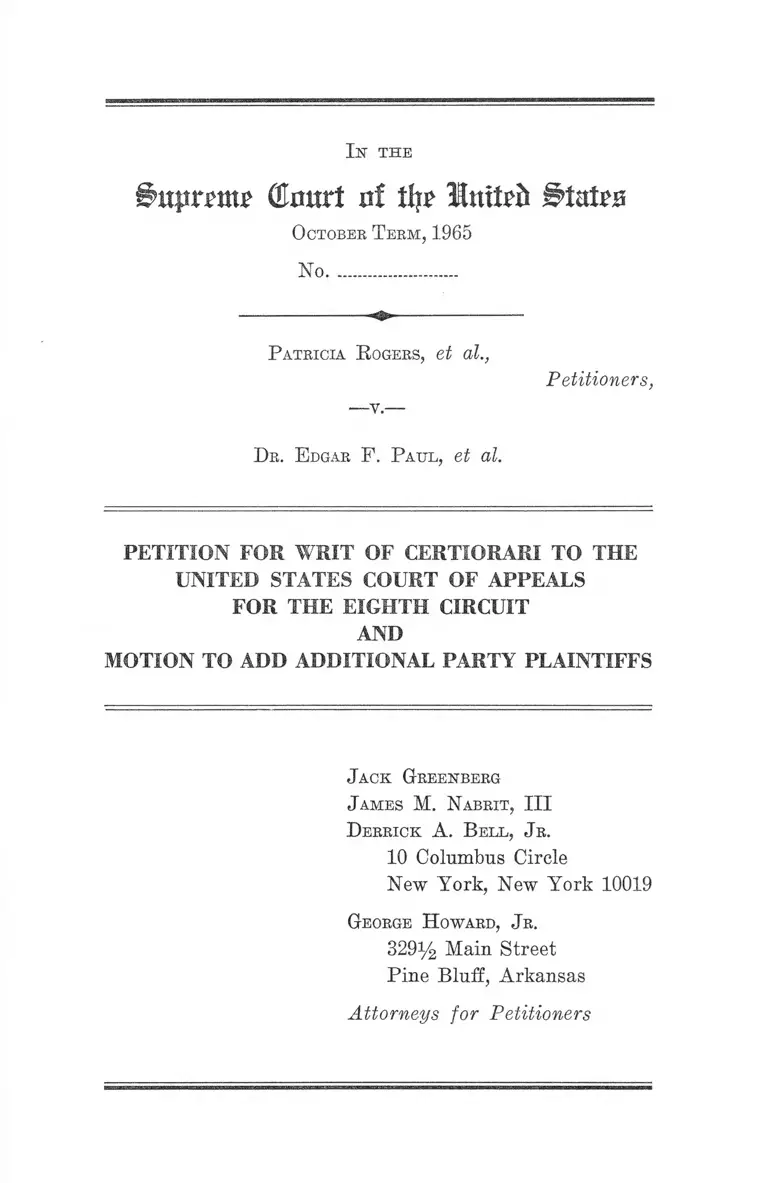

Rogers v Paul Petition for Writ of Certiorari and Motion to Add Party Plaintiffs

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1965

96 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rogers v Paul Petition for Writ of Certiorari and Motion to Add Party Plaintiffs, 1965. e9127fd5-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b394211a-4cd5-4e26-9c36-6f30ec40fe3f/rogers-v-paul-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-and-motion-to-add-party-plaintiffs. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the

§H|ir£itt£ GImtrt of % Imtefc

October T erm, 1965

No........................

P atricia R ogers, et al.,

—v.—

Petitioners,

D r. E dgar F. P aul, et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

AND

MOTION TO ADD ADDITIONAL PARTY PLAINTIFFS

Jack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Derrick A. B ell, Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

George H oward, Jr.

329^ Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

I. P etition eoe W rit oe Certiorari................................. 1

Citations to Opinions Below............................................ 1

Jurisdiction ....................................................................... 2

Questions Presented ........................................................ 2

Constitutional Provision Involved................................. 2

Statement of the Case .................................................... 3

PAGE

Reasons for Granting the Writ ..................................... 11

1. The Fort Smith Plan Unreasonably Delays

Pupil Desegregation and Condemns Negro

Children to Attend Inferior Schools .............. 12

A. The Court of Appeals has approved a pace

of desegregation in conflict with standards

established by this Court and the other cir

cuits ................................................................. 12

B. In view of the grossly inferior education it

provides, the Lincoln School should have

been desegregated immediately ................. 17

C. The lower court’s decision frustrates en

forcement of school desegregation as re

quired by the Civil Rights Act of 1964....... 21

2. Petitioners’ Constitutional Right to a Desegre

gated Education Includes, of Necessity, In

struction by Teachers Assigned Without Re

gard to Race ....................................................... 24

Conclusion 33

11

PAGE

II. Motion foe L eave to A dd Pabty P laintiffs ....... 35

A ppendix

Opinion of Angnst 19, 1964 ................................... la

Judgment Filed August 19, 1964 ............................. 28a

Opinion of May 7, 1965 ........................................ 29a

Judgment Filed May 7, 1965 ................................... 49a

T able of Cases

Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F. 2d 33 (8th Cir. 1958) ........... 15

Acree v. County Board of Education of Richmond

County, Georgia, ------ F. 2d ------ (5th Cir., No.

22,723, June 30, 1965) .................................................. 19

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d

862 (5th Cir. 1962) ...................................................... 26

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31 .......................... ....24, 28

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516 ............................. 28

Bivins v. Bd. of Public Eductaion and Orphanage for

Bibb County, Ga., 342 F. 2d 229 (5th Cir. 1955) .... 31

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County v. Brax

ton, 326 F. 2d 616 (5th Cir. 1964) ............................. 26, 30

Bowditch v. Buncombe County Board of Education,

345 F. 2d 329 (4th Cir. 1965) ..................................... 31

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, Va., 345 F. 2d

310 (4th Cir. 1965) ....................................................... 31

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, Va.,

No. 415 (Oct. Term, 1965) .......................................... 12

Ill

Brewer v. Hoxie School District, 238 F. 2d 91 (8th

Cir. 1956) .............. .................. ................ .......... ........ 16

Brooks v. School District of Moberly, Mo., 267 F. 2d

733 (8th Cir. 1959) .......................... ............................. 28

Browder v. Gayle, 352 IT. S. 903 ......... ................ ...... 24

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 IT. S. 483 .......2, 3,18,19,

21, 24, 30, 32

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 .......3, 4, 9,13,

24, 25

Bryan v. Austin, 148 F. Supp. 563 (E. D. S. C. 1957) 29

Buckner v. County School Board of Greene County,

332 F. 2d 452 (4th Cir. 1964) .............................. . 20

Calhoun v. Latimer, 321 F. 2d 302 (5th Cir. 1963) ....... 31

Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 LT. S. 263 ......................... 12,14, 25

Christmas v. Board of Education of Harford County,

Md., 231 F. Supp. 331 (D. C. Md. 1964) ................"... 30

Colorado Anti Discrimination Commission v. Conti

nental Air Lines, 372 U. S. 714 ................................. 24

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IT. S. 1 ................... .............13,15,16

Corbin v. County School Board of Pulaski County, 177

F. 2d 924 (4th Cir. 1949) ......... ......... ..................... 20

Crisp v. County School Board of Pulaski County, Va.

(W. D. Va., 1960, C. A. No. 1052) 5 Pace Eel. L.

Eep. 721 ........ ............................................................... 20

Dawson v. Baltimore City, 350 U. S. 877 ........................ 24

Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960) ...... 15

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 219 F. Supp.

427 (W. D. Okla. 1963) ............................ ........ ......... 30

Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3rd Cir. 1960) ........... 12

PAGE

Gaines v. Dougherty County Board of Education, 329

F. 2d 823 (5th Cir. 1964) ..........................................

Gebhart v. Belton, 91 A. 2d 137 (Del, 1952) ..............

Gilliam v. School Board of the City of Hopewell, Ya.,

No. 416 (Oct. Term, 1965) ............................................

Gilliam v. School Board of the City of Hopewell, Va.,

345 F. 2d 325 (4th Cir. 1965) .....................................

Goins v. County School Board of Grayson County, 186

F. Supp. 753 (W. D. Va., 1960) .............................

Goode v. Board of Education of Summers County, 8

Eace Eel. L. Eep. 1485 (S. D. W. Va. 1963) ..........

Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, 301 F. 2d

164 (6th Cir. 1962) ........................................... ......13,

Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, 305 F. 2d

523 (6th Cir. 1962) ....................................................

Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knoxville,

373 H. S. 683 .................................... .................. 5, 9,12,

Griffin v. Board of Supervisors, 339 F. 2d 486 (4th

Cir. 1964) .......................... ................................ ...........

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 339 F. 2d 486 (4th Cir. 1964) .........................

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 U. S. 218 ....................................... 12,14,

Griffith v. Board of Education of Yancey County, Civ.

No. 1881 (W. D. N. C.) 186 F. Supp. 511 (W. D.

N. C. 1960) ...................................................................

Henry v. Coahoma County, Miss. Board of Education,

8 Eace Eel. L. Eep. 1480 (N. D. Miss. 1963) ..........

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 ......................

Jackson v. School Board of City of Lynchburg, Va.,

321 F. 2d 230 (4th Cir. 1963) ......................... 12,26,

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 H. S. 61 .................................

19

19

12

31

20

29

19

20

14

31

26

24

20

29

24

31

24

V

Kemp v. Beasley, Civ. No. 4-65-C-8 (E. D. Ark.) .... 22

Lockett v. Board of Education of Muscogee County

Sell. Dist. Ga., 342 F. 2d 225 (5th Cir. 1965) ....... 31

Mapp v. Board of Education of Chattanooga, 319 F. 2d

571 (6th Cir. 1963) ....................................................26,SI

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 IT. S. 637 ..25, 32

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 ....19, 20

Mullaney v. Anderson, 342 U. S. 415 ............................. 36

Northcross v. Board of Education of City of Memphis,

333 F. 2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964) ............... ......... .13,26,31

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961) ....... 15

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 IT. S. 244 ................ 24

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 IT. S. 537 ................................. 18

Potts v. Flax, 313 F. 2d 284 (5th Cir. 1963) .................. 28

Price v. Denison Independent School District,------ F.

2d ------(5th Cir. No. 21632, July 2, 1965) .......... 13,15,16,

21, 23, 31

PAGE

School Board of Warren County v. Kilby, 259 F. 2d

497 (4th Cir. 1958) .......................................... ............. 20

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479 ............................. ....... 28

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate Sehool Dis

trict, ------F. 2 d ------- (5th Cir. No. 22527, June 22,

1965) ................................................................ -............ 23

Sipuel v. Oklahoma Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631 .... 19

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 IT. S. 629 ...................................... 19

Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 ...................... 24

United States v. Board of Education of Greene County,

Mississippi, 332 F. 2d 40 (5th Cir. 1964) .................... 28

VI

United States v. Bossier Parish. School Board, —— F,

2d —— (5th Cir. No. 22863, Aug. 17, 1965) ............ . 23

United States v. City of Bessemer Board of Education,

------F. 2d-------(5th Cir. No. 22862, Aug. 17, 1965) .... 23

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

------F. 2d------- - (5th Cir. No. 22864, Aug. 17,1965) .... 23

United States v. Parke, Davis & Co., 365 U. S. 125....... 3

United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight Assoc., 166

U. S. 290 ........................................................................ 3

Valley v. Rapides Parish School Board,------F. 2d —-—

(5th Cir. No. 22832, Aug. 19,1965) ............................. 23

Walker v. County School Board of Floyd County, Va.

(W. D. Va., 1960, C. A. No. 1012), 5 Race Rel. L.

Rep. 714 ......................................................................... 20

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 .............. .......9,14

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education,------F.

2d ------(4th Cir., No. 9630, June 1, 1965) .................... 31

Yarbrough v. Hulbert West Memphis Sch. District

No. 4, Civ. No. 1048 (W. D. Ark.) ............................. 22

Statutes

28 U. S. C. §1254(1) ......................................................... 2

42 U. S. C. A. §2000d (Civil Rights Act of 1964) ....11, 21, 23

PAGE

45A C. F. R. §80(c) (December 4, 1964) ........................ 22

Other A uthorities

Conant, James B., The American High School Today,

McG-raw Hill, New York (1959) ................................. 18

V ll

General Statement of Policies Under Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 Respecting Desegregation

of Elementary and Secondary Schools, HEW, Office

of Education, April 1964 (H. E. W. Guidelines)..21, 22, 28

Lamanna, Richard A., “ The Negro Teacher and De

PAGE

segregation,” Sociological Inquiry, Vol. 35, No. 1,

Winter 1965 ........................................................... ....... 30

N. T. Times, Aug. 29, 1965, p. 52; Aug. 31, 1965, pp.

1, 42 .............. .................................................................. 23

Southern Education Reporting Service, “ Statistical

Summary of School Segregation-Desegregation in

the Southern and Border States,” 14th Rev., Nov.

1964 ............................................................... 29

Southern School News, May 1965 .............................. . 21

1960 Census of Population, Vol. I, “ Characteristics of

the Population,” Part I, U. S. Summary.................. 30

In the

(Emtrt ®f Mnxtvh

October Teem, 1965

No........................

P atricia R ogers, et al.,

Petitioners,

Dr. E dgar F. Paul, et al.

I

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

AND

MOTION TO ADD ADDITIONAL PARTY PLAINTIFFS

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Cir

cuit entered in the above-entitled cause on May 7, 1965, and

that this Court grant petitioners’ motion to add additional

party plaintiffs.

Citations to Opinions Below

The opinion of the District Court (R. 43), printed in the

Appendix hereto, infra, p. la, is reported in 232 F. Supp.

833. The opinion of the Court of Appeals (R. 44), printed

in the Appendix hereto, infra, p. 29a, is reported in 345

F. 2d 117.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

May 7, 1965 (p. 49a, infra). Mr. Justice White, on July

30, 1965, extended the time for filing the petition for cer

tiorari until September 4, 1965. The jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C., Section 1254(1).

Questions Presented

The following questions are now posed for resolution by

this Court:

1. Whether the Board’s grade-a-year desegregation plan

can be sustained under Brown v. Board of Education, in

the absence of valid administrative problems justifying

delay of complete desegregation until 1968, where such

delay condemns petitioners and all other Negro pupils now

in high school to complete their public school education in

a segregated school, clearly inferior to high schools to which

all white pupils are assigned?

2. Whether petitioners have standing to seek and should

be afforded relief now requiring the school board to cease

assignment of teachers on the basis of race?

Constitutional Provision Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the Constitution of the United States.

3

Statement o f the Case

Petitioner, Mrs. Corine Rogers, filed this action to de

segregate the public schools in Fort Smith, Arkansas, in

September 1963 (R. 1), after unsuccessfully attempting to

obtain transfer of her two minor daughters, Patricia and

Janice, from the Negro Lincoln High School to the white

Northside High School (R. 7).1

Negro parents whose children now constitute less than

ten percent (R. 65) of the 14,000 students (R, 57) pres

ently attending the system’s 30 schools (R. 54) began

efforts to desegregate the Fort Smith schools in 1954 im

mediately after this Court’s decision in Brown v. Board

of Education (R. 75). The Board promised citizens that

they would study the matter (R. 76). The following year,

after the second Brown decision, the local N A A CP again

petitioned the Board for a meeting to discuss school deseg

regation, and as a result, several meetings were held (R. 76).

In September 1957, the Board placed into effect a grade-

a-year desegregation plan adopted the year before (R. 12),

providing for the enrollment of first grade children each

year without regard to race or color. Thus, Negro children

entering the first grade in the Fall of 1957 were permitted

to enroll in a white school, but only if they resided in the

attendance area or zone served by the white school (R. 49). *

* Janice Rogers graduated from the Lincoln School after this

suit was filed (R. 110). Patricia Rogers, however, is enrolled in the

twelfth grade at the Lincoln School, and a motion filed with this

petition, p. 35, infra, seeks to add as minor petitioners in this

case, Vera Moore and Karen Jones, both of whom are now enrolled

np Lincoln High School. Thus, this ease presents issues uncom

plicated by problems of mootness. Moreover, the questions pre

sented are of general public importance. See United States v

Parke, Davis <& Co., 365 U. S. 125; United States v. Trans-Missouri

Freight Assoc., 166 U. S. 290, 308-10.

4

"Where assignment would place the child in a school where

the majority of pupils were of another race, a provision of

the plan permitted transfer to a school where a majority

of the pupils were of the child’s race (E. 22).

By June 1963, when petitioner, Mrs. Eogers, requested

transfer for her daughters (E. 7), both were in high school

and the Board’s plan had reached only grade six. The

transfer applications were denied (E. 12), leading to this

action for injunctive relief: to require their immediate

admission to the Northside School, and to require the

immediate desegregation of the school system, including

assignment of pupils and faculty on a nonracial basis and

the elimination of racial considerations from budgets and

all other school programs (E. 2, 8-10).

During the first seven years of the plan’s operation, only

121 Negroes and 110 white first grade pupils resided in

attendance areas enabling them to enter school on a de

segregated basis (E. 24-29, 51-52). Eighty-five Negro and

all 110 white pupils chose to attend segregated schools

(E. 29). No desegregated assignments were permitted above

the grades reached by the plan, even though Negroes have

made requests for such assignments (E. 78-79). The plan,

moreover, fails to indicate how Negro pupils residing in

white attendance areas but enrolled in Negro schools for

grade one could later be assigned to white schools. As a

result, only about 37 Negroes were attending three white

schools under this plan as of the end of the 1963-64 school

year, and no white children were enrolled in the system’s

four Negro schools (E. 28-29, 50).

In the Answer, the Board referred to its 1957 plan, argu

ing its validity under Brown v. Board of Education, 349

U. S. 294 (E. 13), its efficiency in permitting desegregation

5

while promoting “harmonious and peaceful relationships

between all pupils and patrons” of the School District

(E. 14), and its necessity for solving “ administrative prob

lems of various natures” peculiar to the remaining segre

gated grades (R. 14-15).

Following a pre-trial conference in June 1964 at which

the Board was ordered to prepare a revised desegregation,

plan eliminating the racial minority transfer provisions

(R. 30), the Board in July 1964, filed a plan which main

tained the grade-a-year pace (R. 31-35).2

During the 1964-65 school year, some 197 seventh and

eighth grade pupils at the Negro Lincoln School were as

signed to white junior high schools (R. 39) under the

revised plan. Lincoln High School will serve only grades

10, 11, 12 beginning with the 1965-66 school year by which

time grade-a-year desegregation would be in its ninth year

(R. 39-40, 56). Petitioners objected to the Board’s plan

contending: (a) desegregation was not proceeding with all

deliberate speed, (b) the plan would not benefit Patricia

Rogers, then in the eleventh grade, (c) retention of the

minority transfer provision is unconstitutional, (d) the

2 On June 13, 1964, following the Supreme Court’s decision in

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683, the Board amended its

Answer, summarizing the transfers granted under the minority

racial transfer feature of their plan, and offering to eliminate this

provision (R. 24-29). However, the revised plan provided a one

year extension of the minority transfer plan at the elementary

school level as to white pupils who otherwise would have been

assigned to one of three Negro elementary schools (R. 53-58). The

Board defended the extension by asserting that assigning 55 white

pupils to the Howard Elementary School with 530 Negro pupils,

22 white pupils to Dunbar Elementary School with 60 Negro

pupils, and 30 white pupils to Washington Elementary School

with 70 Negro pupils would result in “an intense psychological

impact” on the white pupils (R. 36-37, 59-63), would adversely

affect the good racial relationships in the community, and would

cause many white children to enter private schools.

6

Lincoln attendance area will be based solely on race, and

(e) no provision is made for desegregation of teaching

personnel (E. 41-42).

At the hearing in Angnst 1964, the Board offered tes

timony in support of its revised plan, emphasizing that

for the 1964-65 school year some 300 Negro pupils would

be assigned to white schools (R. 64), but refused to ex

plain exactly what administrative problems would prevent

immediate desegregation of grades 9-12, and particularly

what problems justified the Board’s denial of applications

for transfer filed by minor plaintiffs and a few other Negro

high school students (E. 78-79).

Having ascertained from the Board Superintendent that

only three Negroes had applied for transfer from the Lin

coln High School, and since the Record was silent as to

why such transfers had been denied, petitioners’ attorney

asked the Superintendent:

“ Q. So at most, roughly you would have three

Negroes who would desire to transfer from the Negro

high school to the white high school. Is that correct?

A. That is all that has asked to as I remember.

“Q. I would like for you to tell this Court now how

three Negroes could disrupt or destroy your educa

tional system. A. Judge, do I have to try to elabo

rate on that?

The Court: No, I think that is a question for the

Court. You have covered it. If you desire you can

elaborate some on it, yes.

“A. Your Honor, I prefer not to try to discuss it any

further than I have.

The Court: All right.

7

“ Q. Then you refuse to answer the question? A.

You haven’t asked a question. You have asked an

opinion.

“ Q. You have been giving opinions here all morning.

The attorneys asked you. A. I have already given

you that opinion.

“ Q. And you refuse to answer the question?

The Court: I am going to hold that he has suffi

ciently answered it.”

Minor petitioner Patricia Rogers was not at all reticent

in explaining why she wanted a transfer to the Northside

High School.

“Q. I would like for you to tell His Honor in your

own words just why you would like to attend the

Northside High School. A. I would like to attend be

cause today Negroes are competing not only against

Negroes for job opportunities but also against whites,

and I think with the integrated education I will have

a lot better opportunity for these jobs than I Avould

just going to a Negro high school.”

In addition to desiring a desegregated education, minor

petitioner Patricia Rogers informed the Board that she

would like to study journalism, music and German. None

of these courses are available at Lincoln (R. 112-13). All

are offered at the two white high schools (R. 122). The

Superintendent testified that petitioner’s course requests

were no basis for transfer because white students cannot

transfer from one high school to the other to obtain wanted

courses (R. 99, 100); but a review of the catalogue shows

that most basic courses are offered at both white schools.3

3 Southside High School is teaching only grades nine through

eleven during the 1964-65 school year (R. 39), explaining why

some Northside courses were not offered during that year.

8

In fact, the two white high schools are far larger and

offer a wider and more varied choice of subjects than are

provided Negroes at Lincoln High School (Pltfs’ Exhs.

2, 3, R. 122-24). There are less than 200 Negroes at Lin

coln’s Senior High (R. 107), while Northside has 2,300

and Southside has 1,000 (R. 96). White high school stu

dents are provided with a 25 page printed “ Course Cata

logue” listing 142 courses in 12 subject matter areas and

detailed information on grading, testing, college require

ments, suggested programs and school policies and regu

lations (Pltfs’ Exh. 2, R. 122). Negro students at Lincoln

get a “ Teachers and Students Handbook,” consisting of

one mimeographed page listing approximately 35 courses

in three divisions (Pltfs’ Exh. 3, R. 124).

While the Board maintains that it has desegregated

grades one through eight under its plan, Negroes are at

tending only five of 27 white schools (R. 25-28, 126). All

schools are still listed for administrative purposes as

“White” and “ Negro” (Pltfs’ Exh. 8, R. 126). As atten

dance areas are now drawn, it appears that such official

designation by race will remain substantially accurate in

fact in the future, particularly at the elementary school

level (R. 25-29).

In addition, the Board has taken no steps to integrate

Negro and white teachers, although all teachers have met

together for several years (R. 76). The Board objected

to allegations of teacher segregation (R. 11, 84), contend

ing petitioners lack standing to raise the teacher issue.

The district court agreed, sustained objection (R. 85, 117),

to petitioners’ efforts to require assignment of teachers

on a nonracial basis, and approved the Board’s Revised

Plan as submitted, Rogers v. Paul, 232 F. Supp. 833 (W. D.

9

Ark. 1964). Reviewing the plan in light of school decisions

by the Supreme Court and various federal courts of ap

peal, the trial court concluded without further elaboration

that the plan met the standards of the cases cited. Thus,

while referring to the decision in Goss v. Board of Edu

cation, 373 U. S. 683, as the basis for its order of June 18,

1964, invalidating the minority transfer provision in the

Board’s plan, the lower court concluded from the number

of pupils utilizing the provision: “ It seems clear that the

great majority of pupils, white and Negro, do not desire

to attend an integrated school.” 232 F. Supp. at 838. The

court indicated no other reason for its approval of the

extension of the provision for use by white elementary

school children during the 1964-65 school year.

In dismissing petitioners’ argument that the Board plan

does not meet current standards for good faith and all

deliberate speed, the court referred to those portions of

Brown v. Board of Education, permitting time to solve

administrative problems, but interpreted the Court’s sub

sequent statements in Watson v. City of Memphis, 373

IJ. S. 526, as relevant only to desegregation in recreational

facilities, 232 F. Supp. at 841. Because the court deemed

the Board’s desegregation efforts “diligent” and the plan

“ eminently successful and satisfactory,” petitioners’ mo

tion for counsel fees (R. 119) was denied. The court then

retained jurisdiction as to the teacher issue “ if presented

by proper parties,” and dismissed the complaint. 232 F.

Supp. at 844. The court entered judgment based on the

above opinion on August 19, 1964 (R. 44), and petitioners

filed notice of appeal on the same date (R. 45).

The Eighth Circuit affirmed the district court on May 7,

1965 (345 F. 2d 117), agreeing that the plan is satisfactory

as to speed and completeness, and the Board’s refusal to

10

immediately complete desegregation was justified by its

fear such action “would needlessly thwart the good faith

efforts of the Board to accomplish de jure desegregation

in a peaceful and orderly manner.” 345 F. 2d at 122.

The Eighth Circuit reviewed several cases from four

circuits condemning grade-a-year desegregation plans, and

distinguished them on the basis that they involved areas

where school boards had failed to act in good faith. Unlike

areas where there was hard core opposition to integration,

the Court found that the transition in Fort Smith was

smooth, without incident, and that the record presented

impressive evidence that “ . . . both races are satisfied

with the revised plan.” 345 F. 2d at 123.

The Court found that the record provided no basis for

ordering the immediate admission of petitioner Patricia

Rogers to the Northside High School because both the

Negro and white schools are accredited and courses are

provided at each school upon request of at least six stu

dents if a teacher can be found to teach it. Cases where

individual petitioners were permitted to transfer to de

segregated schools in order to obtain courses not other

wise available to them were distinguished as arising in

districts where geographical school zoning had not been

adopted. Since Patricia Rogers lives within three blocks

of the Lincoln High School, the Court found that a transfer

would constitute discriminatory action in her favor and

would weaken the school system.

In regard to teacher desegregation, the Eighth Circuit

interpreted the district court’s action, not as requiring a

teacher to raise the question, but as requiring that it be

raised by a pupil then eligible to attend a desegregated

school.

11

Reason for Granting the Writ

The approval by the courts below of a grade-a-year de

segregation plan despite the absence of valid administra

tive problems justifying delay of complete desegregation

for four more years, and the inability of petitioners and

other Negro high school students to obtain an education

in the Negro high school equal (in respects other than

segregation per se) to that provided for white high school

students, presents the question of this Court’s “ all de

liberate speed” standard today.

The Fort Smith plan has condemned both original minor

plaintiffs to complete their public school education in an

inferior segregated school. Two additional Negro high

school students, Yera Moore in the 10th grade and Karen

Jones in the 11th grade, seek to join as petitioners in this

Court, but because the Board’s grade-a-year plan extends

only to grade nine during the 1965-66 school year, these

petitioners too will be denied the benefits of a high quality

desegregated education, as will all other Negro pupils now

in grades ten, eleven and twelve.

At a time when other courts of appeal are constricting

the time in which Southern school boards must extend the

desegregation process to all grades, the Eighth Circuit, by

approving the Fort Smith plan, unduly prolongs the ex

istence of a small, segregated and educationally inefficient

Negro high school, and ironically, shackles petitioners and

their class with a slower desegregation pace than would

have been required by the United States Department of

Health, Education and Welfare for Board compliance with

the 1964 Civil Rights Act if judicial relief to desegregate

the schools had not been sought.

12

The Department considers itself bound by court-approved

plans. Moreover, to the extent that the Department fol

lows the lead of the court, the Eighth Circuit has set a

standard calculated to encourage slowness not speed. And

apart from the effect on H. E. W. standards, this decision

of course will be important for those districts that choose

to forego federal funds. Only the courts can desegregate

them.

This case also presents the issue of faculty desegrega

tion, and whether a school board may delay it until pupil

desegregation is completed or teachers themselves intervene

seeking assignment on a non-racial basis.

Similar issues are presented in petitions for writs of

certiorari filed in Bradley v. The School Board of the City

of Richmond, Va., No. 415 (Oct. Term, 1965), and Gilliam

v. School Board of the City of Hopewell, Va-, No. 416 (Oct.

Term, 1965).

1.

The Fort Smith Plan Unreasonably Delays Pupil De

segregation and Condemns Negro Children to Attend

Inferior Schools.

A. The Court of Appeals has approved a paee of desegregation

in conflict with standards established by this Court and

the other circuits.

In several significant respects as set forth in the follow

ing paragraphs, the decision below conflicts with decisions

of this Court in Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U. S. 263; Griffin

v. School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U. S. 218;

Goss v. Board of Education of City of Knoxville, 373 U. S.

683, and with the Third Circuit in Evans v. Ennis, 281

F. 2d 385 (3d Cir. 1960), the Fourth Circuit in Jackson v.

School Board of the City of Lynchburg, 321 F. 2d 230

(4th Cir. 1963), the Fifth Circuit in Price v. Denison Inde

pendent School District, ------ F. 2d ------ (5th Cir. No.

21632, July 2, 1965), and the Sixth Circuit in Goss v. Board

of Education of City of Knoxville, 301 F. 2d 164 (6th Cir.

1962) and Northcross v. Board of Education of City of

Memphis, 333 F. 2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964).

The basic error in the lower court decision is traceable

to an interpretation of this Court’s “all deliberate speed”

standard placing emphasis on accommodation to opposition

rather than whether change took place as speedily as bona

fide administrative considerations would permit. The court

of appeals approved the district court finding that the

Board’s plan had not upset the “ . . . exceptionally har

monious and cooperating relationship between the races

in Fort Smith, Arkansas” (345 F. 2d at 122). The Court

found that unlike areas such as Prince Edward County,

Virginia, where integration efforts met with hard core

opposition,

In Fort Smith the transition was smooth and without

incident. There was no manifestation of bad feeling or

violent opposition. The lack of any evidence to indicate

any serious objection to the plan of desegregation is

impressive. So far as this record is concerned, both

races are satisfied with the revised plan. It has been

accepted by the majority of pupils and parents as the

best method of complying in good faith with the law

(345 F. 2d at 123).

This Court’s decisions, of course, leave no doubt that re

gardless of community opposition, compliance is required

“at the earliest practicable date” . Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 349 U. S. 294; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1. Beview-

ing the intransigence of Prince Edward County, this Court

14

nevertheless concluded: “ The time for mere ‘deliberate

speed’ has run out, . . . ” Griffin v. School Board of Prince

Edward County, 377 U. S. 218, 234. And as for the main

tenance of existing and commendable good-will between the

races, this Court observed in Watson v. City of Memphis,

373 U. S. 526, 537, that such conditions “ can best be pre

served and extended by the observance and protection, not

the denial, of the basic constitutional rights here asserted.”

But despite these decisions and the more stringent limita

tions on delay imposed in Goss v. Board of Education, 373

U. S. 683, and Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U. S. 263, the court

below, based on testimony that white pupils would suffer

“an intense psychological impact” (R. 37) if required to at

tend Negro schools, approved both the grade-a-year pace

and an extension of a minority transfer provision similar

to one invalidated in Goss v. Board of Education, supra. In

the Superintendent’s view:

Anything of this nature, that is as big a shock as this

would be, in my opinion, to the children, and their par

ents, the discussions that would take place on the

phones, would affect the whole community. It would

affect the working relationship, in my opinion, of the

staff, the School Board, the patrons, and would only

result in difficulty for the smooth operation of the

whole school system, not just the schools involved” (R.

63).4

The Superintendent testified that the Board was grap

pling with problems related to : “ school population growth

and inadequacy of buildings and other facilities” , “mass

shifting within the District of school population from the

4 But compare with Record at 71-73, 113.

15

older sections of Fort Smith to new suburban areas”, a

huge building program; and “ the transition of all schools

into a 6-3-3 system (E. 53-58). The Eighth Circuit con

sidered this testimony as evidence that such administrative

problems precluded acceleration of the plan’s grade-a-year

speed. But there was no testimony as to how these factors

related to the time required for school desegregation, or

more specifically, how they would complicate or prevent

immediate desegregation of the Fort Smith high schools

(see E, 56-57).

The lower court’s second basic error is in the misplaced

importance and distorted effect given to findings concerning

the Board’s good faith progress under the plan. It need

hardly be repeated that school officials may not assert good

faith as a legal excuse for delay. Cooper v. Aaron, supra, at

15. Only recently the Fifth Circuit in requiring rapid ac

celeration of a grade-a-year plan initiated prior to the filing

of a law suit, observed that a school board’s good faith de

sire to do what the law requires is significant:

But in the final analysis it has limited bearing on the

substantive rights accorded and specifically the speed

of the plan. The rights of Negro children come from

the Constitution, not the attitude, good or bad, of school

administrators. Price v. Denison Independent School

District, — F. 2 d ------ (5th Cir. No. 21632, July 2,

1965).

The Eighth Circuit had seemed to adopt a similar view

in Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d 256, 261 (8th Cir. 1960) where

good faith was measured objectively by “ required action”

not “ state of mind.” Accord, Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d

798, 804 (8th Cir. 1961). And it was the Eighth Circuit

which seven years ago stood firm in the face of determined

resistance by state and local governments to desegregation

efforts in Little Eock. Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F. 2d 33, 40

16

(8th Cir. 1958), affd. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1. See also

Brewer v. Hoxie School District No. 46, 238 F. 2d 91 (8th

Cir. 1956).

Clearly, the Eighth Circuit’s departure from standards

set by this Court and followed by the other courts of appeal

which have rejected grade-a-year plans may not be con

cealed by the claim that such cases involve “ . . . situations

where the school boards had either failed to act in good

faith or after inordinate delays had proposed a plan which

was too slow and unduly protracted the process of desegre

gation” 345 F. 2d at 122. For example, the Fifth Circuit in

the Price case supra, accelerated a grade-a-year plan pro

duced in good faith and without inordinate delay. On the

other hand, here the Board’s plan was initiated in 1957, but

its rate of progress until, at least, this suit was filed could

accurately be described as “ slow and unduly protracted.”

As indicated above, no specific reasons were provided why

three years will be required to desegregate the one Negro

high school, Lincoln, with only about 200 students in grades

ten to twelve (R. 107). Nor was there an explanation why

school budgets and records continue to be maintained on a

racial basis (R. 126), or indeed why the Board refuses, short

of a suit by a teacher, to desegregate its teacher hiring and

assignment procedures (R. i l , 84). But whatever the rea

sons, the Eighth Circuit’s position, clearly contrary to the

decisions of this Court and the other courts of appeal, per

petuates the denial of constitutional rights to petitioner and

her class resulting in sacrifices far more severe than en

visioned as necessary in the “all deliberate speed” standard.

17

B. In view of the grossly inferior education it provides, the

Lincoln School should have been desegregated immediately.

The Eighth Circuit stands alone in its willingness to delay

desegregation when such delay condemns petitioner and all

other Negro high school students to attend the undeniably

inferior Lincoln High School. The court below points to

Lincoln’s accredited status as proof of equality without

mentioning that such accreditation is based on a separate

philosophy designed to meet opportunities that may be

available to Negro graduates (R. 89-90). Accreditation how

ever, connotes merely that the school meets the minimum

standards of the accrediting agency, and cannot obscure

the fact that the Lincoln School’s curriculum is woefully

lacking when compared to that provided students attend

ing the white high schools.

Petitioner Patricia Eogers’ expressed belief that an

integrated education would better prepare her for job op

portunities (K. 112) carries more than sociological and

psychological implications when applied to Fort Smith’s

high school facilities. Patricia Rogers specifically supple

mented her desire for a desegregated education, by re

questing instruction in journalism, music, and German (R.

112), none of which are available at Lincoln High (R. 124).

White students attending Northside High School can enroll

in Journalism I, II, III, and IV, as well as 10 different

English courses (4 are offered at Lincoln). In music, white

students are offered Music Theory, three band and four

choral classes while Negroes may take “Band” or “ Glee

Club” in lieu of physical education. Four years of German

are available at Northside as well as four years of Latin,

French and Spanish. Negroes are offered two years of

French.

18

Beyond the subjects in which Patricia Rogers was spe

cifically interested, a plethora of courses designed to pre

pare students for meaningful participation in today’s world

are offered in the white high schools. The courses, illustra

tively listed in a 25 page printed handbook, include and

range from family living, driver education, library science,

mechanical and architectural drawing, trade printing, metal

work, home management, accounting, office machines to col

lege preparatory chemistry, physics, algebra and mathe

matics. These are but a few of the more than 140 courses

offered in the white high schools in twelve subject matter

areas. Negro students at Lincoln High School are offered

none of these courses, and must select in their one page

mimeographed “handbook” from about 35 course offerings

in three subject matter areas.5

Based solely on a summary comparison of the offerings

at the two high school systems, it is obvious that sound

scholastic and constitutional basis exist under Brown v.

Board of Education, supra, and probably even the rejected

“ separate but equal” standard of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163

5 The lower court’s quotation of figures shows that per pupil

costs for Negro high school pupils are higher than those for white

students. This points up the difficulty of maintaining a first class

high school with only 200 students, far below the number experts

consider feasible for an efficient and effective high school. Thus,

Dr. James B. Conant has written:

The enrollment of many American public high schools is

too small to allow a diversified curriculum except at exor

bitant expenses. . . . The prevalence of such high schools—

those with graduating classes of less than one hundred stu

dents— constitutes one of the serious obstacles to good secondary

education throughout most of the United States. I believe

such schools are not in a position to provide a satisfactory

education for any group of their students—the academically

talented, the vocationally oriented, or the slow reader. The

instructional program is neither sufficiently broad nor suffi

ciently challenging. A small high school cannot by its very

19

U. S. 537 for requiring the immediate desegregation of

grades ten thorugh twelve at the Lincoln School.

Indeed, even prior to the decision in Brown v. Board of

Education, this Court in Missouri ex. rel. Gaines v. Canada,

305 U. S. 337; Sipuel v. Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631, and Sweatt

v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629, held that disparity in educational

facilities required immediate desegregation. Moreover, at

the elementary and high school level, the Supreme Court of

Delaware in Gebhart v. Belton, 91 A. 2d 137 (Del. 1952),

held that measurable disparity in facilities requires im

mediate integration.6

Following Brown, a number of federal courts have re

quired immediate school desegregation on a finding of in

equality of facilities. Recently, the Fifth Circuit acting on

a motion for an injunction pending appeal, required the

immediate admission of a Negro student to summer sessions

at a white school in order to obtain Algebra courses not

available at the Negro school. Relief was granted notwith

standing that the appellant was not eligible to attend a de

segregated grade. Acree v. County Board of Education of

Richmond County, Georgia,------F. 2 d ------- (5th Cir., No.

22,723, June 30, 1965). See also, Gaines v. Dougherty

County Board of Education, 329 F. 2d 823 (5th Cir. 1964).

The Sixth Circuit in approving a stair-step school de

segregation plan has denied specific relief to named plain

tiffs who were not eligible for transfer under the plan, Goss

nature offer a comprehensive curriculum. Furthermore, such

a school uses uneconomically the time and efforts of admin

istrators, teachers, and specialists, the shortage of whom is a

serious national problem. Conant, James B., The American

High School Today, pp. 37, 77, McGraw-Hill, New York

(1959).

6 Affirmed sub nom., Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483.

20

y. Board of Education of Knoxville, 301 F. 2d 164, 168 (6th

Cir. 1962), but granted relief where a Negro student sought

a commercial art course not available in Negro schools.

Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, 305 F. 2d 523

(6th Cir. 1962).

For similar reasons, courts in the Fourth Circuit both

prior and after Brown have required the immediate de

segregation of public schools where Negro pupils were

required to leave the school district to attend school, Buch

ner v. County School Board of Greene County, 332 F. 2d

452 (4th Cir. 1964); Goins v. County School Board of Gray

son County, 186 F. Supp. 753 (W. D. Va., 1960), stay denied

282 F. 2d 343 (4th Cir. 1960); School Board of Warren

County v. Kilby, 259 F. 2d 497 (4th Cir. 1958); Corbin v.

County School Board of Pulaski County, 177 F. 2d 924, 927

(4th Cir. 1949); Griffith v. Board of Education of Yancey

County, 186 F. Supp. 511 (W. D. N. (1, 1960); Walker v.

County School Board of Floyd County, Va. (W. D. Va.,

1960, C. A. No. 1012), 5 Race Eel. L. Rep. 714; Crisp v.

County School Board of Pulaski County, Va. (W. 1). Va.,

1960, No. 1052), 5 Race Eel. L. Rep. 721.

Thus, even assuming the presence of valid factors miti

gating against the immediate desegregation of grades ten

through twelve, it appears that only the Eighth Circuit

would refuse Negro students the right to immediate ad

mission to white schools to obtain courses not available at

Lincoln High. Petitioners’ right to such admission is in no

way diminished by the Superintendent’s offer to provide

any course at any high school “ if there are as many as six

students that want the course and we can find a teacher to

teach it” (R. 89).7 As this Court indicated in Missouri ex

7 While teacher segregation will be discussed below, its continued

presence in the Fort Smith system adversely affects the likelihood

21

rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, 351, constitutional

rights cannot be made to depend upon the number of per

sons who may be discriminated against.

C. The lower court’s decision frustrates enforcement of school

desegregation as required by the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 represents a Congressional

effort to implement this Court’s decision in the Brown

case, by forbidding in Title VI of its provisions the dis

bursement of federal funds to facilities (including schools)

which discriminate on the basis of race or color.8 Acting

pursuant to the authority of Title VI, the United States

Department of Health, Education and Welfare (H. E. W.)

and its Office of Education has prepared standards for

school boards seeking to desegregate their systems.9 Under

the standards contained in its “ General Policy Statement,”

school boards making the transition from biracial to de

segregated systems must as a minimum for the 1965-66

school year, take several affirmative steps including desegre

gation of all grades if possible, but no less than four grades,

including “ the first and last high school grades,” desegre

gate all grades by the 1967-68 school year, permit any pupil

assigned to a segregated school to transfer, irrespective of

whether the grade he is attending has been desegregated,

“ . . . to take a course of study for which he is qualified and

that the superintendent will be able to fulfill his offer at the Lincoln

High School.

8 42 U. S. C. §2000d.

9 General Statement of Policies Under Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 Respecting Desegregation of Elementary and Secondary

Schools, HEW, Office of Education, April 1964. The document,

hereinafter cited as “H. E. W. Guidelines” is reprinted in the ap

pendix to Price v. Denison Independent School District,------ P. 2d

------ (5th Cir. No. 21632, July 2, 1965), and in Southern School

News, May 1965, pp. 8-9.

22

which is not available in the school he is attending;”

(H. E. W. Guidelines, V, E 1, 4).10 11

Unfortunately for petitioners and their class, the regula

tions under which Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

are administered,11 and the H. E. W. Guidelines based on

these regulations, supra, provide that school boards are

eligible for financial assistance if they are subject to a final

court order of desegregation. As presently interpreted,

this provision applies even though the court order provides

for more limited desegregation than the H. E. W. Guide

lines. Thus, approval by the court below of the Board’s

grade-a-year plan, enables the Board to continue receiving

federal funds and places petitioners in a position worse

than if this suit had not been filed.12 The order of the court

below was accepted as the Fort Smith plan by the Office

of Education on July 19, 1965.

Precisely to avoid such paradoxical results, the Fifth

Circuit, recognizing the United States Office of Education as

better qualified and “ the more appropriate federal body to

10 As of August 24, 1965, the Office of Education reported that

they have accepted desegregation plans from 113 Arkansas school

boards, 68 of which provide for desegregation in all 12 grades in

the Fall of 1965. Ten school boards will desegregate all 12 grades

by the Fall of 1966 and 35 will complete desegregation in 1967.

An additional 80 Arkansas Boards have submitted plans which are

pending approval in the Office of Education.

11 45A C. F. R. §80 (c) (December 4, 1964).

12 Unhappily, petitioners are not alone. District courts in the

Eighth Circuit have recently approved desegregation plans in El

Dorado, Arkansas, Kemp v. Beasley, Civ. No. 4-65-C-8 (E. D. Ark.),

and West Memphis, Arkansas, Yarbrough v. Hulbert-West Mem

phis Sch. District No. 4 Civ. No. 1048 (W. D. Ark.), both of which

plans limit desegregation to two grades in 1965 and in a variety of

other respects, fall short of meeting the minimum standards con

tained in the H. E. W. Guidelines. The Office of Education reports

that both court orders have been accepted, assuring the continued

flow of federal funds to these school districts.

weigh administrative difficulties inherent in school de

segregation plans,” rejected a grade-a-year plan in Single-

ton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,------F.

2d------ (5th Cir., No. 22527, June 22, 1965), and by injunc

tion pending appeal ordered the district court to conform

the plan to the minimum standards fixed by the United

States Office of Education. This policy, the court said, was

intended to prevent school boards from using federal courts

as a means of circumventing requirements for financial

aid.13 “If judicial standards are lower,” predicted the Fifth

Circuit in Singleton, supra, “ recalcitrant school boards in

effect will receive a premium for recalcitrance; the more the

intransigence, the bigger the bonus.”

The restricting effect the lower court’s decision has had

on school desegregation thus not only denies petitioners’

constitutional rights, but also creates standards which

handicap uniform enforcement of Title VI of the 1964 Civil

Rights Act. It now appears that many Boards will waive all

federal aid rather than comply with the Civil Rights Act

(see N. T. Times, Aug. 29, 1965, p. 52, Aug. 31, 1965, pp.

1, 42). The lower court’s decision encourages such recalci

trant systems to maintain segregation until suits are filed

and the more lenient judicial standards are invoked.

13 The Fifth Circuit has followed its decision in the Singleton

case in Price v. Denison Independent School District, supra, and by-

injunction pending appeal in United States v. Jefferson County

Board of Education,------ F. 2 d ------- (5th Cir. No. 22864, Aug. 17,

1965); United States v. City of Bessemer Board of Education,------

F. 2d ------ (5th Cir. No. 22862, Aug. 17, 1965) ; United States v.

Bossier Parish School Board,------ F. 2 d -------- (5th Cir. No. 22863,

Aug. 17, 1965); and Valley v. Rapides Parish School Board,------

F. 2d ------ (5th Cir. No. 22832, Aug. 19,1965).

24

2.

Petitioners’ Constitutional Right to a Desegregated

Education Includes, o l Necessity, Instruction by

Teachers Assigned Without Regard to Race.

During the decade since Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U. S. 483, 349 U. S. 294, the principles established in

those cases have been interpreted to prohibit all racial

discrimination by states.14 Petitioners submit it is time to

direct immediate implementation of their right to attend

schools where teachers and other faculty personnel are as

signed on a non-racial basis. Such relief is closely linked

to the requirement under Brown v. Board of Education, 349

U. S. 294, to have the district courts supervise the effectua

tion of “ a racially nondiscriminatory school system” (349

U. S. at 301, emphasis added). The Court in deciding the

second Brown case, supra, pointed to administrative prob

lems related to “ the physical condition of the school plant,

the school transportation system, personnel, revision of

school districts and attendance areas into compact units

to achieve a system of determining admission to the public

schools on a nonracial basis, and revision of local laws and

regulations . . . ” , as matters to be considered in apprais

ing the time necessary for good faith compliance (emphasis

added). We believe that the Court plainly regarded the

14 Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U. S.

218 (schools) ; Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 (restaurant) ;

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61 (courtroom) ; Colorado Anti-

Discrimination Commission v. Continental Air Lines, 372 U. S.

714, 721 (employment) ; Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 (air

port restaurant) ; Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31 (transporta

tion) ; Browder v. Gayle, 352 U. S. 903 (buses); Holmes v. Atlanta,

350 U. S. 879 (municipal golf courses); Dawson v. Baltimore City,

350 U. S. 877 (municipal beaches).

25

task as one of ending all discrimination in school systems,

including “personnel” as well as discrimination in the trans

portation system, attendance districts or the other factors

mentioned. The delay countenanced by the “ deliberate

speed” doctrine was predicated on the assumption that

dual school systems would be reorganized.

The brief of the United States, as amicus curiae, in

Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U. S. 263, argued in this Court

that:

Obviously, a public school system cannot be truly non-

discriminatory if the school board assigns school per

sonnel on the basis of race. Full desegregation can

never be achieved if certain schools continue to have

all-Negro faculties while others have all-white faculties.

Schools will continue to be known as “white schools”

or “Negro schools” depending on the racial composi

tion of their faculties. It follows that the school au

thorities must take steps to eliminate segregation of

personnel as well as pupils. (Brief of the United States,

pp. 39-40.)

The judgment in Calhoun was vacated without discussion

of this issue, but in addition to the statements in Brown

quoted above, this Court earlier had condemned state-

imposed racial restrictions which produced inequalities in

the training of a teacher. McLaurin v. Oklahoma State

Regents, 339 U. S. 637. There, the Court found that racial

restrictions would impair and inhibit the learning of a

student seeking a graduate degree in education, and that

the adverse affect on his education, would in turn be re

flected in the education and development of those he taught

339 U. S. at 641. What is obviously true of the graduate

26

student in education cannot be less so when applied to

students at the elementary and high school level.

The lower court’s ruling that petitioners lack standing

to question the Board’s policy of assigning teaching per

sonnel on a segregated basis as effectively preserves the

traditional characterization of Fort Smith’s schools as

“white” or “ colored” , as racial signs over the doors. The

ruling, moreover, is contrary to rulings on the standing

issue in the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Circuits,15 each of

which courts has read the attack on teacher segregation:

“ . . . as a claim that continued assigning of teaching

personnel on a racial basis impairs the students’ right

to an education free from any consideration of race.”

Mapp v. Board of Education of Chattanooga, 319 F.

2d at 576.

The record, moreover, simply does not support the

Eighth Circuit’s conclusion (345 F. 2d at 125) that the

district court refused to consider teacher desegregation

because petitioners were not attending grades being de

segregated.

The Board moved to strike petitioners’ allegations re

garding teacher segregation from the complaint (R. 6),

contending such facts “ . . . are insihficient to state a claim

upon which plaintiffs are entitled to or can be granted any

relief . . . ” (R. 11). And at the hearing, when peti

15 Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, 339

F. 2d 486 (4th Cir. 1964); Jackson v. School Board of City of

Lynchburg, 321 F. 2d 230 (4th Cir. 1963); Board of Public In

struction of Duval County v. Braxton, 326 F. 2d 616, 620 (5th Cir.

1964) ; Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862, 869

(5th Cir. 1962); Northeross v. Board of Education of City of Mem

phis, 333 F. 2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964); Mapp v. Board of Education

of Chattanooga, 319 F. 2d 571 (6th Cir. 1963).

27

tioners’ attorney attempted to question the Superintendent

with reference to desegregation of teachers and adminis

trative personnel, the Board’s attorney objected, stating:

“ . . . we do not conceive that to be an issue before the

Court in this case. No teachers are parties.” (R. 84). (Em

phasis added.)

The district court sustained objection, and during a

subsequent colloquy with counsel explained that jurisdic

tion would be retained so that if there was “ a bona

fide effort on the part of interested parties, particularly

the teachers for assignment, . . . then they could simply

intervene here . . . ” (R. 118). Plaintiffs’ counsel sought

clarification as to whether it was the court’s position that

petitioners lacked sufficient interest to raise the question

of faculty desegregation, and the court responded, “ That

is, in effect, the ruling of the Court . . . ” (R. 118). Thus,

the district court’s opinion accurately summarizes its posi

tion :

u . . . the court sustained an objection to the introduc

tion of evidence by plaintiffs on the question of assign

ment of teachers, but in order to avoid a multiplicity

of suits, the Court will retain jurisdiction of the case

in order that the question may be raised if any proper

party desires to intervene.” 232 Fed. Supp. at 843.

(Emphasis added.)

Clearly, the district court contemplated that parties

not then before the Court must “ intervene” to question

teacher segregation, which language refutes the Eighth

Circuit’s interpretation that petitioners may raise the

teacher desegregation issue when they become eligible to

enter desegregated grades. Even if its reading of the dis

trict court’s intention had been accurate, however, such a

view would place unjustified restrictions on the right to re

lief of petitioners who seek for themselves, and all other

Negro pupils in the system, not just desegregated assign

ments, but a desegregated school system. See Bailey v.

Patterson, 369 U. S. 31, 33. Potts v. Flax, 313 F. 2d 284,

288-89 (5th Cir. 1963).

Approval of the Board’s plan by the court below with

out requiring teacher desegregation further disadvantages

petitioners for having sought relief in the courts. School

systems required to desegregate in accordance with the

standards contained in the H. E. W. guidelines, must take

positive steps to eliminate faculty as well as pupil segrega

tion.16

Obviously, the Fort Smith system cannot be desegregated

as long as the faculty at each school is assigned on the

basis of race. Just as obviously, the careers of Negro

teachers in the South, particularly in Arkansas, are too

tenuous to reasonably expect their participation in school

desegregation suits.17

16 The H. B. W. Guidelines provide in Par. V B :

1. Faculty and staff desegregation. All desegregation plans

shall provide for the desegregation of faculty and staff in ac

cordance with the following requirements:

a. Initial assignments. The race, color, or national origin

of pupils shall not be a factor in the assignment to a par

ticular school or class within a school of teachers, admin

istrators or other employees who serve pupils.

b. Segregation resulting from prior discriminatory as

signments. Steps shall also be taken toward the elimina

tion of segregation of teaching and staff personnel in the

school resulting from prior assignments based on race,

color, or national origin (see also, Y. B. 4 (b ) ).

17 Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479; Bates v. Little Bock, 361

U. S. 516; United States v. Board of Education of Greene County,

332 P. 2d 40 (5th Cir. 1964) ■ Brooks v. School District of Moberly,

29

The number of Negro teachers in Fort Smith schools is

not large. Their assignment on a nonracial basis along

with white teachers in the system will hardly constitute a

major administrative problem, and may substantially re

lieve the “ intense psychological impact” the Board fears

will result from assigning white children to Negro schools

(R. 36-37, 59-63). Indeed, it is significant that the Board’s

fear of psychological trauma was voiced only when white

pupils were to be assigned to school with all Negro faculties.

The significance of the decisions on teacher desegrega

tion and their effects on society should not be ignored. In

1964-65 Arkansas public schools employed 13,205 white

teachers and 3,545 Negro teachers.18 Complete teacher

segregation is maintained, except in Little Rock where,

in the fall of 1964, a Negro was named Supervisor of

Elementary Education. A similar situation exists in most

southern states. It is estimated that there are 419,199

white teachers and 116,028 Negro teachers in 11 southern

states, six border states (excluding Maryland) and the

District of Columbia.19 There was no faculty desegregation

in Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and South

Carolina. One North Carolina district, two Florida dis

tricts, and seven Tennessee districts had some faculty de

segregation.20

Mo., 267 F. 2d 733 (8th Cir. 1959) ; Henry v. Coahoma County,

Miss. Board of Education, 8 Race Eel. L. Rep. 1480 (N. D. Miss.

1963); Goode v. Board of Education of Summers County, 8 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 1485 (S. D. W. Ya. 1963) ; Bryan v. Austin, 148 F.

Supp. 563, 567 (E. D. S. C. 1957), judgment vacated 354 U. S. 933.

18 Southern Education Reporting Service, “ Statistical Summary

of School Segregation-Desegregation in the Southern and Border

States” , 14th Rev., Nov. 1964, p. 8.

19 Id. at p. 2.

20 Id. at pp. 2,15, 39, 50.

30

Within the Negro community, Negro teachers generally

are recognized as having a leadership role with a com

paratively high economic position21 but their potential

as leaders in efforts to promote desegregation of public

facilities and schools is limited.22 Continued faculty segre

gation, posing the danger of discharge of Negro teachers

as Negro pupils go to white schools where no Negro teachers

are assigned threatens potentially disastrous soeial con

sequences for one of the most important social and eco

nomic groups in Negro communities in the South.

Increasingly, district courts are reaching the conclusion

that faculty desegregation is not only necessary to effec

tuate the mandate of Brown, but that delaying the process

until pupil desegregation is complete increases to the point

of impossibility the difficulty of completely disestablishing

segregation in the system.23 But the courts of appeal, while

apparently willing to affirm district court orders requiring

faculty desegregation,24 have hesitated to require immedi

ate implementation of perhaps the most vital part of the

school desegregation process, and in case after case, sus

21 According to the 1960 census the median income for the non

white family was $3,662, but the median for the non-white family

whose head was employed as an elementary or secondary teacher

was $6,409 (1960 Census of Population, Vol. I, “ Characteristics of

the Population,” Part I, U. S. Summary, Table 230, pp. 1-611).

22 Lamanna, Richard A., “ The Negro Teacher and Desegregation” ,

Sociological Inquiry, Yol. 35, No. 1, Winter 1965.

23 See Christmas v. Board of Education of Harford County, 231

P. Supp. 331 (D. Md. 1964); Howell v. School Board of Oklahoma

City, 219 P. Supp. 427 (N. D. Okla. 1963) ; Board of Public In

struction of Duval County v. Braxton, 326 F. 2d 616, 620 (5th Cir.

1964).

24 Board of Public Instruction of Duval County v. Braxton,

supra.

31

tain lower court rulings delaying teacher integration.25 Its

construction of the district court’s ruling on teachers aside,

the Eighth Circuit’s decision here has the same effect as

the rulings in the other courts of appeal, i.e., the delay of

teacher desegregation until pupil desegregation is sub

stantially complete.

Such delay has been criticized in a dissent to the Fourth

Circuit’s ruling postponing consideration of the teacher

segregation issue in Bradley v. School Board of Richmond,

Va., 345 F. 2d 310, 324 (4th Cir. 1965) by Judges Sobeloff

and Bell in terms appropriate to this case:

The composition of the faculty as well as the com

position of its student body determines the character

of a school. Indeed, as long as there is a strict separa

tion of the races in faculties, schools will remain

“white” and “Negro” making student desegregation

more difficult. . . . The question of faculty desegrega

tion was squarely raised in the District Court and

should be heard. It should not remain in limbo indefi

nitely. After a hearing there is a limited discretion

as to when and how to enforce the plaintiffs’ rights in

respect to this, as there is in respect to other issues, * V.

25 Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education,------ P. 2d —-—

(4th Cir. No. 9630, June 1, 1965) • Gilliam v. School Board of City

of Hopewell, 345 P. 2d 325 (4th Cir. 1965) ; Bradley v. School

Board of Richmond, Va., 345 P. 2d 310 (4th Cir. 1965); Bowditch

V. Buncombe County Board of Ed., 345 F. 2d 329, 332, 333 (4th

Cir. 1965) ■ Griffin v. Board of Supervisors, 339 P. 2d 486, 493

(4th Cir. 1964) ; Jackson v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg,

321 P. 2d 230, 233 (4th Cir. 1963); Price v. Denison Independent

School District,------ P. 2 d ------- (5th Cir. No. 21632, July 2, 1965);

Lockett v. Board of Education of Muscogee County Sch. Dist., Ga.,

342 P. 2d 225, 229 (5th Cir. 1965) ; Bivins v. Board of Public Edu

cation and Orphanage for Bibb County, Ga., 342 P. 2d 229, 232

(5th Cir. 1965) ; Calhoun v, Latimer, 321 P. 2d 302, 311 (5th Cir.

1963); Northcross v. Board of Education of City of Memphis, 333

P. 2d 661, 666-67 (6th Cir. 1964) ; Mapp v. Board of Education of

Chattanooga, 319 F. 2d 571 (6th Cir. 1963).

since administrative considerations are involved; but

the matter should be inquired into promptly. There

is no legal reason why desegregation of faculties and

student bodies may not proceed simultaneously.

The views expressed by Judges Sobeloff and Bell, peti

tioners submit, are constitutionally and practically cor

rect. A policy of assigning teachers to schools on the basis

of the race of the pupils is plainly invidious even without

regard to its effect on what schools various pupils attend.

Pupils admitted to public schools are entitled to be treated

alike without racial differentiations in those schools. Mc-

Laurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, supra. The student’s

relationship with teachers is central to the educational ex

perience in public schools. When a state decrees that those

Negro pupils in all-Negro schools be taught only by Negro

teachers and that those Negro pupils in schools with white

children be taught only by white teachers, it significantly

perpetuates the segregation of Negro Americans in their

educational experience. This is contrary to the egalitarian

principle of the Fourteenth Amendment and the teaching

of Brown that segregated education is “ inherently unequal.”

The issues presented by the grade-a-year plan and the

faculty segregation issue merge into a common problem

of vital importance to the implementation of the Brown

decision, and deserve review by this Court.

33

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for the foregoing reasons it is respectfully

submitted that the petition for certiorari should be

granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greekberg

James M. Nabrit, III

D errick A. B ell, Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

George H oward, Jr.

3291/2 Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

Attorneys for Petitioners

3S

II

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO ADD PARTY PLAINTIFFS

Petitioners, pursuant to the provisions of Rule 21, Fed

eral Rules of Civil Procedure, move the Court for leave

to add as party plaintiffs in the subject case Vera Moore,

minor, by her mother and next friend, Mrs. Ellsworth Win-

ton, and Karen Jones, minor, by her mother and next

friend, Mrs. Beatrice C. McCain, and in support of said

motion show the Court:

1. Each of the parties who join in this motion to be

added as plaintiffs in this case are Negroes and are resi

dents of Fort Smith, Arkansas. Vera Moore is eligible to

enter the 10th grade in the Fort Smith public schools and

has been assigned to the Negro Lincoln High School. Karen

Jones is eligible to enter the 11th grade in the Fort Smith

public schools and has been assigned to the Lincoln High

School.

2. This action was filed in September 1963 to desegre

gate the public schools in Fort Smith, Arkansas, by Mrs.

Corine Rogers on behalf of her two minor daughters, Janice

and Patricia Rogers, both of whom were then assigned to

the Lincoln High School. The suit sought relief for both

the named plaintiffs and for all other persons similarly

situated. The parties seeking to be added as plaintiffs are

members of the class upon whose behalf relief was sought

in the subject case.

3. The proposed minor party plaintiffs in this action

could have been original proper party plaintiffs, having

been enrolled in the Fort Smith public schools and suffer

36

ing from the racial segregation existing in the school sys

tem at the time this action was filed.

4. Moreover, the parties seeking to be added as party

plaintiffs seek relief requiring the complete desegregation

of the Fort Smith schools and their immediate admission

to the white Nortliside High School for all the reasons

originally stated by petitioners.

5. During the period since this suit was filed, one of the

original minor plaintiffs, Janice Rogers, has graduated

from the Lincoln High School and is thus no longer en

rolled in the Fort Smith public school system. The other

minor plaintiff, Patricia Rogers, will enter the 12th grade

at the Lincoln High School in September 1965, and may

graduate before all the relief sought in the complaint can

be obtained and the issues raised by this litigation finally

settled.

6. Petitioners, thus seek to add additional party plain

tiffs so as to insure complete and effective disposition of

all issues raised in this case and avoid any possibility that

the class will not be adequately represented.

7. Granting petitioners’ motion will make members of

the represented class real parties in interest, and will not

result in embarrassment or unfair handicap to the defen

dants. Mullaney v. Anderson, 342 U. S. 415.

37

"Wherefore, for all the foregoing reasons, petitioners

move the Court for leave to add as party plaintiffs in the

subject case Yera Moore, minor, by her mother and

next friend, Mrs. Ellsworth Winton, and Karen Jones,