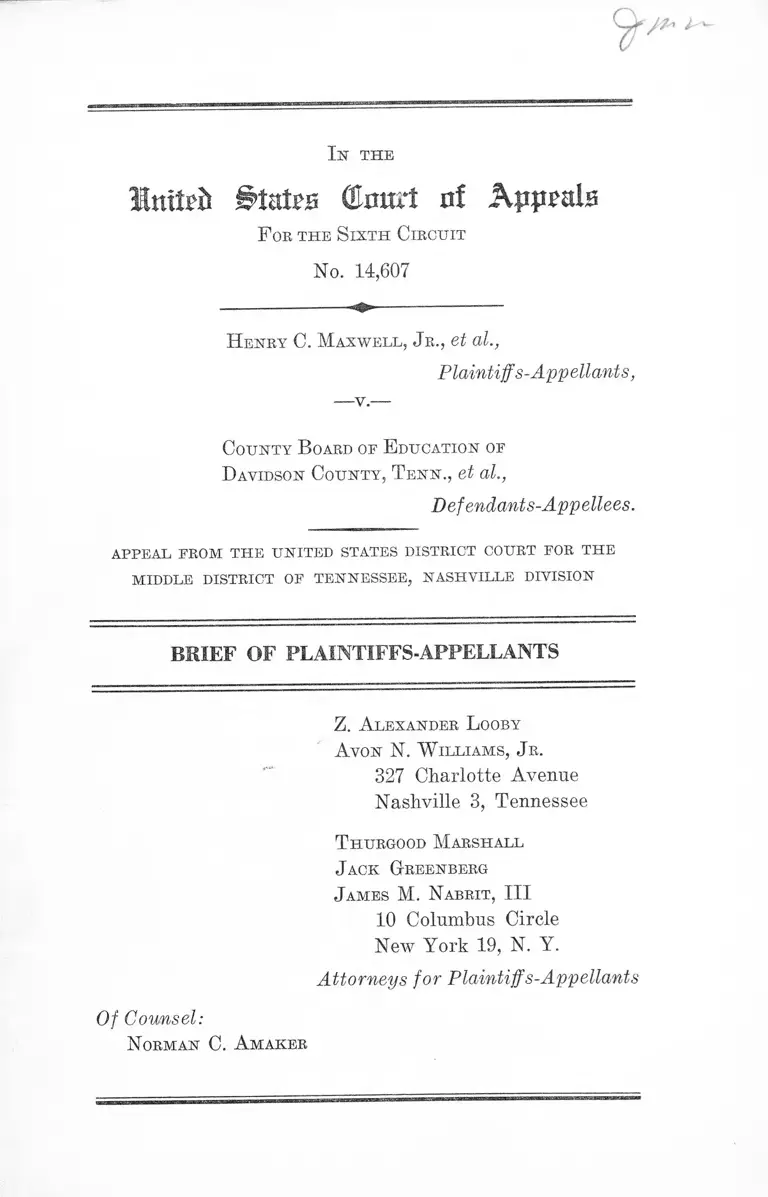

Maxwell v. Davidson County, TN Board of Education Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Maxwell v. Davidson County, TN Board of Education Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1961. b275ae3e-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b3af3bb6-9b11-4190-bd3b-60563255dbdc/maxwell-v-davidson-county-tn-board-of-education-brief-of-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

9 -

fp > l ' '

I s THE

IMtth Btntts (Emart n! Kppmls

F ob th e S ix t h C ibcuit

No. 14,607

H enry C. M axw ell , J r ., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

Cou nty B oard of E ducation of

D avidson Co u nty , T e n n ., et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

appeal from th e united states district court for the

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE, NASHVILLE DIVISION

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Z. A lexander L ooby

A von N. W illiam s , J r .

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

T hurgood M arshall

J ack G reenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Of Counsel:

N orman C. A m akbr

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of Questions Involved ... .. 1

Statement of F acts.................................... 2

Argument ............................................................. 9

Relief ................................................................. 23

T able oe Cases :

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249, 73 S. Ct. 1031, 97

L. ed. 1586 (1953) ........................ .................... .............. 21

Board of Education v. Groves, 261 F. 2d 527 (4th Cir.

1958) ........................ .............. ...... 15

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497, 74 S. Ct. 693, 98 L. ed.

884 (1954) .................................................................. .....11,18

Booker v. State of Tennessee Board of Education, 240

F. 2d 689 (6th Cir. 1957) ___________ _____ _______ ..15,16

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) ................ 18

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct.

686, 98 L. ed. 873 (1954) ..................................... ..... ...10,11

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct.

753, 99 L. ed. 1083 (1955) ______ ___ ____ 10,11,12,14, 21

Buchanan v. War ley, 245 U. S. 60, 38 S. Ct. 16, 62 L. ed.

149 (1918) ....... ................................................................. 14

Child Labor Tax Case, 259 U. S. 20, 42 S. Ct. 449, 66

L. ed. 817 (1922) ....................................... .................... . 22

Clemons v. Board of Education, 228 F. 2d 853 (6th Cir.

1956) ................................................. ........... ................... 15

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 78 S. Ct. 1401, 3 L. ed.

2d 5 (1958) ......................................................... 10,11,14, 21

IX

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S. D. Ala., 1949) ..... 22

Ethyl Gasoline Corp. v. United States, 309 U. S. 436,

60 S. Ct. 618, 84 L. ed. 852 (1940) ....... .......................... 22

Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3rd Cir. 1960) ............... 15

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81, 63 S. Ct.

1375, 87 L. ed. 1774 (1943) ................... ........................ 18

H. J. Heintz Co. v. N.L.R.B., 110 F. 2d 843 (6th Cir.

1940), aff’d, 311 U. S. 514................................................ 22

International Asso. of Machinists v. N.L.R.B., 311 U. S.

72, aff’g 110 F. 2d 29 (D. C. Cir. 1940) ...................... 22

Kelley v. Board of Education, 270 F. 2d 209 (6th Cir.

1959) 15,17

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214, 65 S. Ct.

193, 89 L. ed. 194 (1944)........................................ 18

Lucy v. Adams, 350 U. S. 1, 76 S. Ct. 33, 100 L. ed. 3

(1955) ............................................................................... 15

McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. R. Co., 235 U. S. 151,

35 S. Ct. 69, 59 L. ed. 169 (1914) .............................. 11,19

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, 59

S. Ct. 232, 83 L. ed. 208 (1938) ....... ................... ....... 11,19

Moore v. Board of Education, 252 F. 2d 291 (4th Cir.

1958), aff’g 152 F. Supp. 114 (D. Md. 1957), cert,

den. sub nom. Slade v. Board of Education, 357 U. S.

906 (1958) .................... - ....... - ........................................ 15

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449, 78 S. Ct. 1163,

2 L. ed. 2d 1488 (1958) .......................................

N.L.R.B. v. Colton, 105 F. 2d 179 (6th Cir. 1939)

PAGE

21

22

I l l

N.L.R.B. v. Link-Belt Co., 311 U. S. 584 ............. .......... . 22

N.L.R.B. v. Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock

Co., 308 U. S. 241.................... ...................................... 22

N.L.R.B. v. Pennsylvania Greyhound Lines, Inc., 303

U. S. 261........ .............. ........................................ ........... 22

N.L.R.B. v. Southern Bell Tel. & Tel. Co., 319 U. S. 50 22

N.L.R.B. v. Tappan Stove Co., 174 F. 2d 1007 (6th Cir.

1949) ..... .......... ............... ....... ................ - ....................... 22

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633 ...... .......... ............ . 19

Pettit v. Board of Education, 184 F. Supp. 452 (D. Md.

1960)... .......... ....... ................................... .... ................... - 15

Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328 IT. S. 395, 66 S. Ct.

1086, 90 L. ed. 1332 (1946) .......... ......... ..... ............ ..... 20

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 68 S. Ct. 836, 92 L. ed.

1161 (1948) ............................................... ............. 19,20,21

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631, 68 S. Ct. 299,

92 L. ed. 247 (1948) ..................... ................ ....... ......... 11

Sparrow v. Strong, 70 U. S. (3 Wall.) 97, 18 L. ed. 49

(1866) ...................... ............ - ................... ............. - ..... . 22

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 IJ. S. 303, 25 L. ed. 664

(1880) ................ ...... ......... ............... ................. ............. 20

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629, 70 S, Ct. 848, 94 L. ed.

1114 (1950) ..........................................................- ........ - 11

Texas & N. O. A. Co. v. Brotherhood of Rg. & S. S.

Clerks, 281 U. S. 548 ......... .......... ................................. . 22

Watts v. Indiana, 338 U. S. 49, 69 S. Ct. 1347, 93 L. ed.

1801 (1949) .......................... ............................................ 22

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U. S.

173, 65 S. Ct. 254, 89 L. ed. 160 (1944) ........ .......... . 22

PAGE

IV

Oth er A uthorities :

PAGE

“ Pomeroy’s Equity Jurisprudence” , 5th Ed., Symons,

1941 ........... ...... ............. ......... ......................................... 20

“ The Lawfulness of the Segregation Decisions” , Black,

69 Yale Law J. 421, 428 ................................................. 16

V

INDEX TO APPENDIX

Relevant Docket Entries ..........-.................................. la

Complaint ....................... —-.....-............................... la

Motion for Temporary Restraining Order ................. 26a

Motion for Preliminary Injunction ........................—- 27a

Order to Show Cause ...... 28a

Motion to Dismiss ........ 29a

Affidavit of J. E. Moss .......................... -...................... 31a

Exhibit “ A ” to Affidavit .......—-....... ................... 36a

Exhibit “ B” to Affidavit........................................ 37a

Affidavit of Frank White ............................................ 38a

Affidavit of Melvin B. Turner...................................... 40a

Motion to Strike Certain Portions of the Complaint.. 42a

Answer ..............—........................................................... 43a

Excerpts from Transcript of Hearing, September 26,

1960 ............................................................................... 52a

J. E. Moss ............................................................... 52a

Melvin B. Turner.................................................... 54a

J. E. Moss ............................................................... 55a

Order, October 7, 1960 .................................................. 61a

PAGE

VI

Report of the County Board of Education ............... 64a

Exhibit “ A ” to Report .......................................... 65a

Plan ........................................................................... 69a

Specification of Objections to Plan .......... ................ 72a

Excerpts from Transcript of Hearing, October 24,

1960 ...................... ....................................... ................ 77a

J. E. Moss ................................. ........... .................. 77a

Dr. Eugene Weinstein ......................... 94a

Annie P. D river.......................................................... 108a

Henry C. Maxwell .......................................... 110a

Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Judgment

November 23, 1960 ........................................................ 114a

Judgment ................................................................... 131a

Order, November 29,1960 ................................................ 134a

Motion for New Trial and for Appropriate Relief .. 136a

Motion of Plaintiffs for Further Relief ..................... 139a

Exhibit “ A ” to Plaintiffs’ Motion ......................... 142a

Supplemental Answer .................................... 146a

Excerpts from Transcript of Hearing, January 10,

1961 ...................................................... 149a

Joseph R. Garrett ............................... 149a

Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Judgment 171a

Judgment ......................................................... 175a

Notice of Appeal .................................. 177a

PAGE

I n THE

BUUb (Euurl of Appeals

F ob th e S ix t h Circuit

No. 14,607

H enry C. M axw ell , Jr., et al.,

Plaintiff s-Appellants,

— v .—

County B oard of E ducation of

D avidson Co u nty , T e n n ., et al,,

Defendants-Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE, NASHVILLE DIVISION

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Statement o f Questions Involved

I. Were appellant Negro children denied Fourteenth

Amendment rights by refusal of an injunction requiring

appellee board to admit them to white schools when the

court below approved a grade-a-year desegregation plan

barring appellants and other Negroes in grades above those

covered by the plan from an opportunity for desegrega

tion?

The Court below answered the question No.

Appellants contend it should be answered Yes.

2

II. Have appellants been deprived of rights protected

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States by a provision of the board’s desegregation

plan which expressly recognizes race as an absolute ground

for transfer between schools, and thus tends to perpetuate

racial segregation?

The Court below answered the question No.

Appellants contend it should be answered Yes.

Statement o f Facts

This case involves racial segregation in the public schools

of Davidson County, Tennessee, an area surrounding the

City of Nashville. Plaintiffs are Negro residents of David

son County; the adults are parents of minor plaintiffs,

12 children attending the County public schools. Appel

lants here are 4 families including 9 children.

September 9, 1960, plaintiffs filed this class action (Eule

23(a)(3), Federal Eules of Civil Procedure) in the Dis

trict Court for the Middle District of Tennessee, against

defendants-appellees, the County Board of Education and

County School Superintendent. The complaint (7a-25a)

generally alleged racially segregated operation of the

Davidson County schools and exclusion of several plain

tiffs from particular schools on a racial basis, claiming that

these practices violated the Fourteenth Amendment. Plain

tiffs sought injunctive and declaratory relief, asking that

defendants be restrained from “maintaining or operating

a compulsory racially segregated public school system” in

the County, and also “ from refusing to admit plaintiffs and

other persons similarly situated” to designated schools

(24a). The complaint also requested that the Court:

. . . enter a decree directing the defendants to present

a complete plan, . . . for the reorganization of the

3

entire school system . . . into a unitary, nonracial

school system which shall include a plan for the

assignment of children on a nonracial basis, the assign

ment of teachers, principals and school personnel on a

nonracial basis, the drawing of school zone lines on a

nonracial basis, the allotment of funds, the construction

of schools, the approval of budgets on a nonracial

basis, and the elimination of any other discriminations

in the operation of the school system or in the school

curriculum which are based solely upon race and color.

(24a-25a).

Defendants filed various pleadings setting forth objec

tions and defenses, including a motion to dismiss (29a)

and an answer (43a). The answer admitted that the county

schools were operated on a racially segregated basis (Com

plaint H8; Answer ff8), and acknowledged the exclusion of

some of the minor plaintiffs from designated schools on

the basis of race at the start of the 1960-61 school term

(Ans. j[10).

September 19, 1960, the Court issued a show cause order

(28a). At the hearing held September 26, 1960, the Board,

bv counsel, acknowledged its obligation to present a de

segregation plan. The Court received evidence relating to

the requests of six of the minor plaintiffs for temporary

injunctive relief to admit them to all white schools. These

six children were the Maxwell, Driver and Clark childien.

It was explained to the Court that no request for immediate

individual relief was made by the other six pupils who at

tended elementary grades served by all-Negro schools close

to their homes. The Superintendent of Schools acknowl

edged that the admission of these six children to the schools

requested would not cause any serious administrative prob

lems which would disrupt the schools (53a-54a); and he

identified the possibility of friction, bloodshed, or fights

4

as the principal reasons for opposing their admission

(56a-60a). It was clear that the six plaintiffs lived closer

to the white schools they sought to enter than the colored

school they attended (41a).

The Court withheld action on the request for injunctive

relief but did direct the defendants to submit a desegrega

tion plan by October 19,1960.

The Board submitted a plan (69a-71a) which provided

in part: (1) for the desegregation of one school grade each

year beginning September, 1961; (2) for zoning without

reference to race for each grade as it became desegregated;

(3) that each student entering the first grade would be per

mitted to attend school in the zone of his residence; (4) for

“ careful consideration” of applications for transfer for

“ good cause” of students from the school of their zone to

another school; (5) that valid conditions for requesting

transfer would be when a white or colored child would

otherwise be required to attend a school previously serving

students of the other race or to attend a school where the

majority of students were of a different race; (6) for a

plan of pupil registration each Spring.

Plaintiffs objected to the plan (72a-76a) because: (1) it

did not provide for desegregation “with all deliberate

speed” ; (2) it did not take into account the more than six

year period since the Brown case in which the Board had

failed to take any steps to comply with that ruling; (3) the

twelve year period proposed before desegregation would be

complete was not “ necessary in the public interest” nor

“ consistent with good faith compliance at the earliest prac

ticable date” with the Brown decision; (4) the defendants

had not sustained “ their burden of showing any substantial

problems related to public school administration” of the

types specified in Brown; (5) the plan substantially copied

the so-called “Nashville Plan” without regard for local

5

conditions in Davidson County and was “ a minimum plan

predicated on subjective and mental fears of the defendants

as to possible community hostility or friction among stu

dents” ; (6) it would forever deprive infant plaintiffs and

all other Negro children now enrolled in the public schools

of Davidson County of their rights to a racially unsegre

gated public education” ; (7) it ignored and failed to comply

with the Court’s statement from the bench on 26 Septem

ber 1960 to the effect that the individual plaintiffs had

been denied their constitutional rights and which suggested

that these rights be accorded voluntarily by defendant

rather than by court order; (8) it failed to take account of

recent annexation by the City of Nashville of a large area

of Davidson County as a result of which some of the public

schools of the County became a part of the partially de

segregated Nashville school system; (9) it prevented plain

tiffs from enrolling in schools of a technical or specialized

nature where enrollment is not based on location of resi

dence; (10) racial factors were “valid conditions” of trans

fer requests and such factors were designed to perpetuate

racial segregation; (11) the absence of any provision for

reorganization of the entire County school system “ into a

unitary, nonracial school system” contemplated “ continued

maintenance and operation by defendants of ‘Negro’ and

‘white’ schools substantially designated by race.”

Plaintiffs renewed their motions for injunctive relief to

be effective no later than January, 1961, and again prayed

for reorganization of the entire school system on a non

racial basis (75a-76a).

The Court held a 4-day hearing beginning October 24,

1960; excerpts from the testimony appear at 77a. et seq.

Superintendent Moss testified that the County system had

about 45,000 white pupils and 2400 Negro pupils; the

County maintains 7 Negro schools (77a). He further testi

fied that with complete desegregation about 1,000 Negro

6

pupils would be eligible to attend the white schools. It

was admitted that the six plaintiffs who sought admission

to white schools could be accommodated “as far as room is

concerned” (82a); and that desegregation could eliminate

some of the system’s transportation problems (83a). Mr.

Moss acknowledged that in recent years the Board had

built two Negro schools located for maximum use under

a segregated system (83a-84a); that pupils were allowed

to transfer during the school year for administrative rea

sons without any period of waiting (85a); that the transfer

provisions of the Board’s plan were identical to those in

the Nashville Plan, and that as the plan operated in Nash

ville and was intended to operate in Davidson County,

pupils were not required to go to the schools in their zones

and then seek transfers out but were assigned as before

unless they affirmatively sought transfers to the schools in

their zones (91a-92a).

Dr. Eugene Weinstein, Associate Professor of Sociology

at Vanderbilt University, testified as to a survey of the

attitudes of Negro parents in Nashville who had a choice

as to whether or not to send their children to desegregated

schools. He indicated that the most frequent factor influ

encing parents not to send their children to desegregated

schools under the stair-step plan with a transfer option pro

vision was an unwillingness to separate several children

in a family (97a). He further testified that experience in

Nashville indicated “mass paper transfers of Whites back

into what is historically the White school, of Negroes re

maining in what is historically the Negro school; and that

the transfer provisions tend to keep system ‘oriented’ to

ward a segregated system with token desegregation” (101a-

102a).

In its findings, the Court found with respect to the Max

well, Driver and Clark children, that “had these infant

7

plaintiffs been white children, they would have been ad

mitted or transferred to the said ‘white’ schools to which

they applied” (116a).

In its opinion of November 23, 1960 (114a, et seq.), the

Court approved the proposed plan with several exceptions.

The Court required the Board to desegregate grades 1

through 4 beginning in January 1961, in order that desegre

gation in the County would proceed on the same schedule as

in Nashville. The Court also required desegregation of sum

mer classes, and provided for specific notice by the defen

dants to parents of their zones of residence. Plaintiffs’

prayers for injunctive relief were denied, including the re

quest of several plaintiffs for immediate admission. The

Court said:

The legal rights of all plaintiffs are recognized and

declared but they are enforced in accordance with the

provisions of the plan with the above modifications.

Said plan is not a denial of the rights of the individual

plaintiffs, but is a postponement in enforcement of the

rights of some of the plaintiffs in the interest of the

school system itself and the efficient, harmonious, and

workable transition to a desegregated method of oper

ation. (131a.)

The Court reserved judgment on the question of segregated

teaching and personnel assignments.

On December 2, 1960, plaintiffs moved for a new trial

and for appropriate relief under Federal Rules 59 and 60,

again raising the question of individual relief for the Max

well and Clark children and for one member of the Driver

family. Plaintiffs maintained that the Board had made no

showing that justified a continued exclusion of these four

children and that their personal rights under the Four

teenth Amendment were violated (136a-138a).

8

Plaintiffs also moved for further relief (139a), object

ing to the defendants’ administration of the pupil transfer

provision and particularly to the notices given to parents.

The Court considered these motions and the matter of

teacher and personnel segregation on January 10, 1961.

At the hearing Mr. Joseph Garrett, a member of the School

Board staff, testified as to the operation of notification and

transfer procedures. The notices sent to parents required

them to indicate within three days whether they requested

permission for their children to remain at the schools the

children were then attending, or whether they sought admis

sion to be “ transferred” to the newly zoned school (142a-

145a; 149a-170a). There were 288 white children and 405

Negro children affected by the new zoning in grades one

through four (150a). In this group, which received no

tices, 51 pupils— all Negroes—requested permission to

“ transfer” to the newly zoned schools (165a).

On January 24, 1961, the Court filed an opinion and

judgment (171a, et seq.). It found the objections to the

notification procedure unjustified, denied the relief prayed

in the motion for further relief, and overruled and denied

the motion for a new trial an appropriate relief. With re

spect to the individual requests for relief, the Court said:

With respect to the request of the four individual

plaintiffs, Cleophus Driver, Deborah Ruth Clark,

Henry C. Maxwell, Jr., and Benjamin Grover Max

well, to be admitted to schools as exceptions to said

desegregation plan, the Court is of the opinion that to

grant such exceptions would be in effect to invite the

destruction of the very plan which the Court has held

is for the best interest of the school system of David

son County. It is not a plan which is designed to deny

the constitutional rights of anyone. It is a plan which

is designed to effect an orderly, harmonious, and effec-

9

five transition from a racially segregated system to a

racially nonsegregated system of schools, taking into

account the conditions existing in this particular lo

cality. And the Court cannot see how these individual

plaintiffs who brought this action are or would be en

titled to any different treatment from any other chil

dren who attend the schools of Davidson County and

are members of the class represented by the plain

tiffs. (173a.)

On the question of personnel segregation, the Court denied

relief but provided that plaintiffs could renew the request

at a later date after the plan had been put into operation.

The plaintiffs on February 20, 1961, appealed from the

judgments, entered November 23, 1960 and January 24,

1961.

ARGUMENT

I.

Were appellant Negro children denied Fourteenth

Amendment rights by refusal o f an injunction requiring

appellee board to admit them to white schools when the

court below approved a grade-a-year desegregation plan

barring appellants and other Negroes in grades above

those covered by the plan from an opportunity for de

segregation?

The Court below answered the question No.

Appellants contend it should be answered Yes.

On three occasions the court below considered and denied

requests of minor appellants Henry C. Maxwell, Jr., Ben

jamin G-. Maxwell, and Deborah Ruth Clark that defen

dants be required to admit them to certain schools from

10

which they had been excluded on a racial basis. At each

hearing it was undisputed that they would have been ad

mitted readily if they had been white; the court below so

found (115a-116a).

In explaining* its rulings the trial court stated in sub

stance that its denial of individual injunctive relief was

merely a “postponement and not a denial of relief to the

plaintiffs (131a); that to grant exceptions to the plan would

“ destroy the plan” (171a) or “ invite” its destruction

(173a); and that these plaintiffs were not entitled to any

different treatment than other members of the class repre

sented (173a). The decision did not rest upon and the record

does not support, any theory that these plaintiffs’ exclusion

was justified, temporarily or permanently by any adminis

trative obstacles to their individual admission. Eather,

without dispute, these children could and would have been

accommodated immediately in the white schools if they

were white (53a-55a; 82a, 86a). The only basis suggested

by defendants for excluding them were the Superinten

dent’s prediction of friction, fighting, violence and blood

shed (54a, 56a, 57a, 60a), based upon his reading about

what occurred in Little Rock (57a, 93a-94a), and an argu

ment that if these pupils were admitted others must have

the same privilege (60a).

Before considering the bases for the ruling below, it is

important to discuss the character of the rights involved

on this appeal. Appellants’ rights to freedom from compul

sory racial segregation stem from their fundamental rights

not to be denied the equal protection of the laws or to be

deprived of liberty without due process of law under the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 74

S. Ct. 686, 98 L. ed. 873 (1954), and 349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct.

753, 99 L. ed. 1083 (1955); Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1,

11

78 S. Ct. 1401, 3 L. ed. 2d 5 (1958). The Court said in

Cooper at 358 U. S. 1,19 :

The right of a student not to be segregated on racial

grounds in schools so maintained is indeed so funda

mental and pervasive that it is embraced in the concept

of due process of law. Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497,

74 S. Ct. 693, 98 L. ed. 884.

It must be reemphasized that the right involved is a

personal right, as was again stated in Brown, supra at 349

U. S. 300, where the Court said:

At stake is the personal interest of the plaintiffs in

admission to public schools as soon as practicable on

a nondiscriminatory basis.

Of course the personal and present nature of Fourteenth

Amendment rights had been established long before the

“ separate but equal” doctrine was repudiated by Brown.

See Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629, 635, 70 S. Ct. 848, 94

L. ed. 1114 (1950); Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S.

631, 633, 68 S. Ct. 299, 92 L. ed. 247 (1948); McCabe v.

Atchison, T. & 8. F. R. Co., 235 U. S. 151, 161-162, 35

S. Ct. 69, 59 L. ed. 169 (1914); Missouri ex rel. Gaines v.

Canada, 305 U. S. 337, 351, 59 S. Ct. 232, 83 L. ed. 208

(1938).

The second Brown opinion provided that courts could

allow delay, after a prompt start toward compliance, where

this was shown to be “ necessary in the public interest and

consistent with good faith compliance at the earliest prac

ticable date” . But nothing in Brown, or the subsequent

Cooper opinion, indicates that the “ personal interest of the

plaintiffs in admission to public schools as soon as prac

ticable on a nondiscriminatory basis” can be disregarded

completely in favor of a plan affording relief to other

Negro pupils, but allowing plaintiffs no opportunity ever

12

to escape segregated schools or enter the exclusive white

schools. Thus it is submitted that the action taken by the

Court below in denying relief to plaintiffs is in conflict with

the governing principles set forth in Brown.

None of the reasons set forth in the opinions of the trial

court for denying relief can disturb this conclusion. The

statement below that the enforcement of appellants rights

was merely “ postponed” and not denied was and must re

main extremely puzzling. Apparently it does not refer to

any possibility that appellants might at some indefinite

time in the future be granted admission as an exception to

the plan, for this possibility seems to be completely re

jected by the ruling that exceptions would “ destroy” the

plan. The possibility that the Court really meant but

neglected to say that it would consider granting exceptions

at a later unspecified time is dispelled by the colloquy

with counsel following the court’s oral ruling (which was

later embodied in the written findings and conclusions).1

1 See the following in the transcript of the hearing on “ Objec

tions to Plan” at pp. 518-519:

“Mr. Williams: And Your Honor is denying any relief to

these individual plaintiffs?

The Court: I am not denying it. The decree should spe

cifically include another provision, that the legal rights of all

plaintiffs are recognized and declared but that they are en

forced in accordance with the provisions of this plan with the

modifications that I have made.

As I pointed out, any gradual plan is going to involve a

postponement to some extent. You call it a denial, but (as

the Court of Appeals pointed out in the city case) it is not

a denial of their rights; it is a postponement of the enforce

ment of the rights of the plaintiffs in the interest of the

school system itself.

Mr. Williams: I would just like to inquire as to when their

rights to an education actually will ever be enforced, if Your

Honor please.

The Court: You understand what I have held.

Mr. Williams: Yes, sir.

The Court: Is there anything else from either party?

Mr. Williams: Plaintiffs respectfully except, if the Court

please.”

13

The further possibility that the word “ postponed” refers

to some opportunity that plaintiffs might have for desegre

gation in the normal course of events under the plan, is

plainly untenable. It is evident on the face of the plan

that appellants will never have an opportunity to attend

any but segregated all-Negro classes in all-Negro schools.

It is manifest that appellants will remain in segregated

classes, since appellants attend grades higher than those

affected at the start of the plan, and since both the appel

lants and the desegregation plan will move progressively

upward one grade each year—never meeting. The pos

sibility that appellants might in the future attend segre

gated classes in some school which had desegregated lower

grades, is so remote as to be unreal in the light of the racial

option transfer provision. Under this provision the all-

Negro schools will remain all-Negro. This we know from

experience (in both Nashville and Davidson County, 102a,

165a) and because a view of the realities of the community

concerned compels the conclusion that few if any white

pupils will elect to attend the all-Negro schools. Even if

this remote possibility did occur appellants would still be

excluded from schools they were entitled to attend on a

racial basis. Neither the court below nor the defendants

suggest this as a basis for curing the denial of relief to

appellants. Finally, since there was no showing of valid

administrative obtacles to the admission of these plaintiffs,

there was no basis for even a “postponement” of their

admission.

The conclusion of the court below that to allow excep

tions to the plan would “destroy” it is equally ambiguous

and confusing. If this is meant as an acceptance of defen

dants’ contentions that desegregation in higher grades

would cause friction and violence, and that this would de

stroy the plan, then plainly an impermissible consideration

was used. The irrelevance of disagreement with or hostility

14

to desegregation and the principle that constitutional rights

may not yield to violent opposition is firmly settled. Brown

v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 300; Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U. S. 1, 7, 16; Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 81,

38 S. Ct. 16, 20; 62 L. ed. 149 (1918). Of course, it may

be that the court merely meant that creating exceptions to

to the plan would destroy its uniformity, or that an excep

tion for these plaintiffs would require later exceptions for

others in such numbers as to cause administrative diffi

culties. Neither idea is very helpful in determining the

question as issue, i.e., whether the uniformity of the plan

must be “ destroyed” in order to protect appellants’ rights.

It is, of course, possible that other Negroes might request

exceptions if these were allowed. This possibility does not

alter the fact that there were actually only a small group

of persons before the court requesting this relief, and that

there was no indication that their admission would cause

any administrative difficulties in the school system. I f the

court found it necessary to formulate a rule for dealing

with the jjossibility of large numbers of future applicants

for exceptions, it is right at hand: the court can determine

on the basis of the circumstances before it, including the

number of applicants (if this is claimed to be relevant),

whether the admission of the applicants would present

valid administrative obstacles which necessitate further

delay in the public interest—the rule of the Brown ease. In

order to provide in advance against such a contingency the

court need simply require the defendants to include within

the plan a provision for equitable handling of applications

for exceptions. Among many possibilities, a simple first-

come first-served space available rule, would seem unexcep

tionable. In any event, it should be clear that speculation

as to the possibility of others asserting their rights and

seeking exceptions in the future does not afford a basis for

denying the constitutional rights of those presently before

15

the court. The decision below ignored the personal nature

of plaintiffs’ rights.

Finally, the opinion below suggests that allowing excep

tions for these plaintiffs is in effect an impermissible dis

crimination in their favor. This becomes ironic in the

extreme since the question involved is whether the court

must enforce personal constitutional rights. Actually, it

is rather usual in our system of justice to give legal pro

tection to those who assert their rights actively. Numerous

courts have dealt with the problem at hand and found dif

ferent bases for granting exceptions to gradual desegrega

tion plans, or for different treatment for pupils actively

requesting the right to attend desegregated schools. Evans

v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3rd Cir. 1960); Board of Educa

tion v. Groves, 261 F. 2d 527, 529 (4th Cir. 1958); Moore

v. Board of Education, 252 F. 2d 291 (4th Cir. 1958), aff’g

152 F. Supp. 114 (D. Md. 1957), cert. den. sub nom. Slade

v. Board of Education, 357 U. S. 906 (1958); Pettit v. Board

of Education, 184 F. Supp. 452 (D. Md. 1960); cf. Lucy v.

Adams, 350 U. S. 1, 76 S. Ct. 33,100 L. Ed. 3 (1955). Prior

opinions of this Court are not inconsistent. Kelley v. Board

of Education, 270 F. 2d 209 (6th Cir. 1959) did not discuss

this problem, and should not be regarded as ruling on it.

Justice (then Judge) Stewart concurring in Clemons v.

Board of Education, 228 F. 2d 853, 859-60 (6th Cir. 1956)

clearly regarded the problem of immediate admittance of

the plaintiffs and general desegregation of the school sys

tem as separate matters stating that the district court’s

decree should provide for “ immediate admittance to school

on a non-segregated basis” as well as “ for the end of all

racial segregation” in the schools. In Booker v. State of

Tennessee Board of Education, 240 F. 2d 689, 693 (6th

Cir. 1957), this Court disapproved a proposed plan because

it involved “ a system of admission to the college which

16

does not recognize the rights of these plaintiffs.” As stated

in the opinion at p. 694:

To deny entrance to these plaintiffs for five years, to

place them at the bottom of the list without regard to

the time of their application for entrance, seems to a

majority of the court a noncompliance with the declara

tion of the Supreme Court. Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, supra. (Emphasis supplied)

It is further submitted that plaintiffs should be granted

individual relief without any special showing of particular

individual injury caused by this denial of their constitu

tional rights. (See a discussion of this general problem in

Black, “ The Lawfulness of the Segregation Decisions” , 69

Yale Law J. 421, 428.) We need not and should not go

behind the Brown decision in search for particular injury

to these appellants caused by segregation. One serious mat

ter deserves comment however, for it appears in the trial

court’s findings. This is the finding, based on evidence

offered by defendants in another connection and for an

other purpose, which demonstrates the progressive nature

of the harm caused by segregation very eloquently:

“ f. Negro children in the higher grade levels who have

not previously attended desegregated schools have an

achievement level substantially below that of white

children, and such disproportion in achievement level

increases in direct proportion to the grade of the child

so that any complete desegregation, except upon a

graduated basis, would create additional difficulties

for the children of both races.” (126a-127a)

While these general trends are in no way related in the

record to the situations of the individual appellants, they

demonstrate a likelihood that further continuation of segre

gation will increase their disadvantaged status.

17

II.

Have appellants been deprived o f rights protected

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution o f

the United States by a provision o f the board’ s desegre

gation plan which expressly recognizes race as an ab

solute ground for transfer between schools, and thus

tends to perpetuate racial segregation?

The Court below answered the question No.

Appellants contend it should be answered Yes.

The plan approved by the trial court contains the fol

lowing provision to which appellants object:

“5. The following will be regarded as some of the valid

conditions for requesting transfer:

a. When a white student wonld otherwise be re

quired to attend a school previously serving-

colored students only.

b. When a colored student would otherwise be

required to attend a school previously serving

white students only.

c. When a student would otherwise be required to

attend a school where the majority of students

in that school, or in his or her grade, are of a

different race” (70a).

This provision of the plan is identical to one in the

Knoxville, Tennessee case now pending before this Court,

Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knoxville, Ten

nessee, et al., 6th Cir. No. 14,425. It is also the same as a

portion of the plan approved in Kelley v. Board of Educa

tion of Nashville, 270 F. 2d 209, 228-230 (6th Cir. 1959),

18

and a provision recently held invalid in Boson v. Rippy,

285 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960). As in Goss, supra, ap

pellants urge that the Court reconsider this transfer pro

vision in light of the conflicting Boson opinion and further

arguments herein.

On its face, the plan classifies schools on a racial basis

in terms of whether they were once all Negro or all white

or by reference to the race of the majority of the pupils

in the schools. Pupils also are classified racially in de

termining eligibility for transfers. Such racial classifica

tions must be viewed with grave suspicion for they are

presumptively arbitrary. Korematsu v. United States, 323

U. S. 214, 216, 65 S. Ct. 193, 89 L. ed. 194 (1944); Hira-

bayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81, 100, 63 S. Ct. 1375,

87 L. ed. 1774 (1943); Boson v. Rippy, supra. The Supreme

Court held in Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 IT. S. 497, 74 S. Ct.

693, 98 L. ed. 884 (1954) that racial classifications have

no proper place in public education and that “ segregation

is not reasonably related to any proper governmental

objective.”

Analysis of the plan in terms of the constitutional rights

of the individuals it touches reveals its discriminatory

nature clearly. Consider the individual Negro pupil who

resides in the zone of a school “ previously serving colored

students only”—the Negro living near the “ Negro” school:

he is compelled by the plan to remain in the “Negro”

school, and is denied the option (given to a white pupil

living in the same zone) to transfer out of his zone. The

white pupil living in the “Negro” school zone is granted

an option solely on the basis of his race. The same option

is denied the Negro pupil in that zone solely on the basis

of his race. This is a very evident racial discrimination.

We turn immediately to the correlative discrimination ef-

19

feetecl by the plan, for this is offered up as justification

for the discrimination just considered— the case of a white

pupil living in the zone of a “white” school. This white

pupil is denied a privilege, granted to Negroes in his zone,

of electing to attend a school outside his zone. Again the

plan is racially discriminatory by granting the Negro an

option not available to a white pupil in his zone.

Proponents of the plan will argue that these correlative

discriminations against white and Negroes “ balance out” ,

resulting in a non-discriminatory system. This is a specious

argument, for the symmetry of inequalities created by the

plan only can be thought to create a non-discriminatory

system if we ignore the traditional concept of the rights

of the individual and embrace a novel theory that the

rights of groups or races are at issue. To hold that Negroes

are equally treated because of the reciprocal racial dis

crimination against others ignores the personal nature of

Fourteenth Amendment rights.

In Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 68 S. Ct. 836, 92 L. ed.

1161, it was argued that a racial restrictive covenant en

forced judicially against a Negro was valid, since the

courts would enforce similar covenants against white per

sons. After observing that it knew of no case of such a

covenant against white persons, the Court said at 334

IT. S. 22:

“But there are more fundamental considerations. The

rights created by the first section of the Fourteenth

Amendment are, by its terms, guaranteed to the in

dividual. The rights established are personal rights

[Footnote citing McCabe, supra; Gaines, supra, and

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633]. It is, therefore,

no answer to these petitioners to say that the courts

may also be induced to deny white persons rights

20

of ownership and occupancy on grounds of race or

color. Equal protection of the laws is not achieved

through indiscriminate imposition of inequalities.”

Constitutional rights are personal and not group rights.

Confusion about this may he promoted by the fact that

racial discrimination is aimed at a group and encompasses

every individual group member, making it necessary to

remove the racial rule and thus benefit the whole group in

order to relieve the discrimination against the individual.

Such an approach to school segregation cases was clearly

intended by the Brown decision’s numerous references to

school systems. But there is nothing in this that is novel

and inconsistent with the theory of personal constitutional

rights. Of course it is within the power of equity courts

to grant complete relief even for those not before the

Court (Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328 U. S. 395, 66

S. Ct. 1086, 90 L. ed. 1332 (1946)); and it is an historic

practice of equity courts to avoid a multiplicity of suits

(“ Pomeroy’s Equity Jurisprudence” , 5th Ed., Symons,

1941, §§261, 261(g), 270, 273; Rule 23(a) (3), Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure). The Fourteenth Amendment was in

deed, “ primarily designed” to protect Negroes against

racial discrimination (Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 IT. S.

303, 307, 25 L. ed. 664 (1880), but the Amendment ac

complishes this by requiring that the states deal with

every individual in accordance with its restraints. Shelley

v. Kraemer, supra. In this case the appellants are denied

an option to attend schools outside their zones,1 a valued

privilege extended on a racially discriminatory basis to

others. The transfer provision denies equal protection

of the laws to appellants.

1 Among the appellants, the Davis and Taylor families happen

to be in this situation— see finding No. 5, 116a; see also 91a-92a.

21

Finally the transfer plan may he considered in terms of

its effect on the segregated pattern in the system as a

whole. Under the Brown and Cooper decisions the ade

quacy of the plan must be appraised with due regard for

the defendants’ affirmative obligation to “ devote every ef

fort toward initiating desegregation” (358 U. S. 1, 7),

and to develop “ arrangements pointed toward the earliest

practicable completion of desegregation” (ibid). The pres

ent program of continuing the assignment of students on

the basis of race to schools designated as “ white” and

“ colored,” (pupils actually go directly to the same schools

they always attended unless a “ transfer” is sought to

move to desegregated schools; 142a-145a; 149a-17Qa) ob

viously perpetuates discrimination in the system. By this

option system the school authorities establish a frame

work for parents to elect segregation and preserve it to

a large degree. But if defendants, state officers, are for

bidden to assign pupils on the basis of race by their own

choice, or in obedience to the state legislature, they should

not be allowed to do so in obedience to parents’ and pupils’

desires for racial segregation. Cf. Shelley v. Kraemer,

supra; Barrotvs v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249, 260, 73 S. Ct.

1031, 97 L. ed. 1586 (1953). The “ interplay of govern

mental and private action” , cf. N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama,

357 U. S. 449, 463, 78 S. Ct. 1163, 2 L. ed. 2d 1488 (1958),

works inexorably to preserve segregation.

A realistic appraisal of the plan compels the conclusion

that its natural and intended effect is to preserve segrega

tion. It is apparent to all concerned that few, if any,

white pupils will voluntarily elect to attend the segregated

“ Negro” schools in Davidson County and that these schools

will remain all-Negro. The courts are not required to

“ shut their eyes” and fail to see and understand matters

known to every informed citizen of the community. Cf.

Child Labor Tax Case, 259 U. S. 20, 37, 42 S. Ct. 449,

66 L. ed. 817 (1922); Sparrow v. Strong, 70 IT. S. (3 Wall.)

97, 104, 18 L. ed. 49 (1866); Watts v. Indiana, 338 U. S.

49, 52, 69 S. Ct. 1347, 93 L. ed. 1801 (1949); Davis v.

Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S. D. Ala., 1949). The courts

frequently use such knowledge as, for example, in the

realistic judicial appraisal of “ freedom of choice” in the

context of company dominated trade unions.2 * * * &

Appellants urge that the Court require the submission

of a plan that has some reasonable likelihood of suppress

ing racial discriminations and that is designed “ to preclude

their revival” . Cf. United States v. Crescent Amusement

Co., 323 U. S. 173, 188, 65 S. Ct. 254, 89 L. ed. 160 (1944);

Ethyl Gasoline Corp. v. United States, 309 U. S. 436, 461,

60 S. Ct. 618, 84 L. ed. 852 (1940).

One peripheral point should be mentioned in conclusion.

Supporters of the racial option provision urge an extreme

hypothetical case to justify the general rule established.

They summon up an image of a lone child unwillingly com

pelled to remain in a hostile school where all other pupils

are of a different race, and urge that the option is needed

to provide for such a case. The option rule covers so much

more ground that this is plainly untrue. Actually the option

is so broad as to include pupils in every school or class

that does not have an exactly equal number of pupils of

2 Cf. N.L.B.B. v. Tappan Stove Co., 174 F. 2d 1007 (6th Cir.

1949); N.L.B.B. v. Colton, 105 F. 2d 179 (6th Cir. 1939); H. J.

Heintz Co. v. N.L.B.B., 110 F. 2d 843, 847, 849 (6th Cir. 1940),

aff’d 311 U. S. 514, 522-523; International Asso. of Machinists,

311 U. S. 72, 76, aff’g 110 F. 2d 29, 36 (D. C. Cir. 1940); N.L.B.B.

v. Link-Belt Co., 311 U. S. 584; N.L.B.B. v. Southern Bell Tel.

& Tel. Co., 319 U. S. 50. And Cf. Texas & N.O.A. Co. v. Brother

hood of Bg. & S. S. Clerks, 281 U. S. 548, 559-560; N.L.B.B. v.

Pennsylvania Greyhound Lines, Inc., 303 U. S. 261; N.L.B.B. v.

Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Bock Co., 308 U. S. 241.

23

both, races (at any given moment). Indeed it covers every

school that was at any time in the past attended by pupils

of one race alone. The school board retains its usual powers

to regulate the transfer of pupils on nonracial grounds

based on the educational judgments of the responsible

authorities (see paragraph 4 of plan; 70a). Even if the

hypothetical case of the single white child in the “ Negro”

school were to occur, this would be no reason for a Court of

the United States to recognize race as grounds for govern

mental action. Such a case, however, is supposititious in

the extreme, for, for all that one knows, such a child might

validly transfer on nonracial grounds. It is submitted that

the racially discriminatory transfer option rule should be

held to violate the Fourteenth Amendment.

Relief

For the foregoing reasons appellants respectfully submit

that the judgment of the Court below should be reversed

and that the cause should be remanded with directions to

the trial court t o :

1. Enter an injunction restraining the appellees forth

with from further refusing to admit the appellants to

schools which they are qualified to attend on the basis of

their race or color; and

2. Enter an order directing appellees to formulate and

submit within a specified time period a new plan for the

desegregation of the County schools, which shall provide

for the abolition of pupil assignments and transfers based

24

on race or color, and the abolition of racial designations

for schools.

Appellants request that the Court grant such other and

further relief as may seem just and proper.

Of Counsel:

Respectfully submitted,

Z. A lexander L ooby

A von N. W illiam s , J r .

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

T hurgood M arshall

J ack G reenberg

J ames M . N abrit , III

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 1790

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Plaintiff's-Appellants

N orman C. A m aker