McKinnie v. Tennessee Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McKinnie v. Tennessee Reply Brief, 1965. 40e48dae-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b3eacc48-7597-4a37-aea8-9720917dc22e/mckinnie-v-tennessee-reply-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I

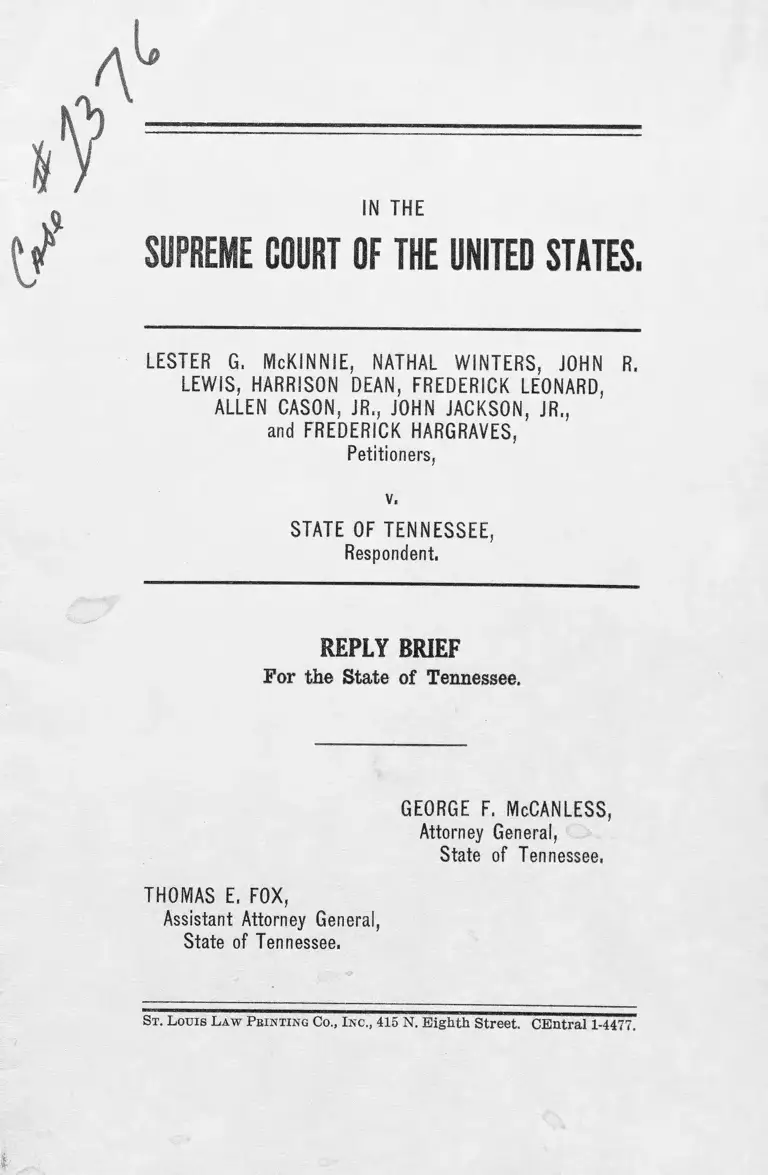

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

LESTER G. McKINNIE, NATHAL WINTERS, JOHN R.

LEWIS, HARRISON DEAN, FREDERICK LEONARD,

ALLEN CASON, JR., JOHN JACKSON, JR.,

and FREDERICK HARGRAVES,

Petitioners,

v.

STATE OF TENNESSEE,

Respondent,

REPLY BRIEF

For the State of Tennessee.

GEORGE F. McCANLESS,

Attorney General,

State of Tennessee,

THOMAS E. FOX,

Assistant Attorney General,

State of Tennessee,

St. Louis Law F einting Co., Inc., 415 N. Eighth Street. CEntral 1-4477.

INDEX.

Page

Opinion below ............................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ...................................................................... 2

Questions presented ........................................................ 2

Statement of the evidence ............................................. 3

Argument .................... 5

Cases Cited.

American Tobacco Co. v. United States, 328 U. S. 780,

808, 66 S. Ct, 1125, 1139, 90 L. Ed. 1575, 1594 ......... 9

Arthur Hamm, Jr. v. City of Eock Hill, and Frank

James Lupper et al. v. State of Arkansas, 33 U. S. L.

Week 4079, December 15, 1964 ................................... 5,7

Elizabethton v. Carter County, 204 Tenn. 452, 321

S. W. 2d 822 ................................................................. 13

Feiner v. People of State of New York, 340 U. S. 315,

71 S. Ct. 303, 95 L. Ed. 295 ......................................... 5, 6

Frazier v. Elmore, 180 Tenn. 232, 173 S. W. 2d 563 . . . 13

Garner v. State of Louisiana, 368 IT. S. 157, 82 S. Ct.

248, 7 L. Ed. 2d 207 .................................................. 10-11

Goldfinger v. Feintuch, 11 N. E. 2d 910, annotated 116

A. L. K. 477 ................................................................. 11

Green et al. v. United States, 19 F. 2d 850, 855 ......... 15

Hormel v. Guy T. Helvering, 312 U. S. 551, 61 S. Ct.

719, 85 L. Ed. 1037 .................................................... 13

Ingram v. United States, 360 U. S. 672, 679-680, 79

S. Ct. 1314, 1320, 3 L. Ed. 2d 1503, 1509 .................. 10

Kennedy v. State of Tennessee, 186 Tenn. 310, 210

S. W. 2d 132 15

Lombard v. State of Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267, 83 S. Ct.

1122, 10 L. Ed. 2d 339 ................................................. 12

Palmer v. Hoffman, 318 U. S. 109, 119-120, 63 S. Ct.

477, 483, 87 L. Ed. 645, 653 ..................................... 14

Peterson v. City of Greeneville, 373 U. S. 244, 83 S. Ct.

1119, 10 L. Ed. 2d 323 ................................................ 12

Senn v. Tile Layers Union, 301 U. S. 468, 57 S. Ct.

857, 81 L. Ed. 1229 ..................................................... 11

Thiel v. Southern Pac. Co., 328 U. S. 217, 66 S. Ct.

984, 90 L. Ed. 481........................................................... 16

Statutes Cited.

Sec. 39-1101, Tennessee Code Annotated .................1, 2,13

Sec. 62-710, Tennessee Code Annotated .................3,11,14

Sec. 62-177, Tennessee Code Annotated ...................... 13

Title II, Sec. 207 (b), Civil Rights Act of 1964 ......... 8

ii

Miscellaneous Cited.

IT. S. L. Week 4084, December 15, 1964 8

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

LESTER G. McKINNIE, NATHAL WINTERS, JOHN R.

LEWIS, HARRISON DEAN, FREDERICK LEONARD,

ALLEN CASON, JR., JOHN JACKSON, JR.,

and FREDERICK HARGRAVES,

Petitioners,

v.

STATE OF TENNESSEE,

Respondent.

REPLY BRIEF

For the State of Tennessee.

May It P lease the Court :

OPINION BELOW.

The petitioners in this cause were convicted for a con

spiracy to injure the business of the B & W Cafeteria,

Nashville, Tennessee, by blocking the entrance to the

restaurant in violation of Section 39-1101, Tennessee Code

Annotated, which provides, inter alia, that the crime of

conspiracy may be committed by two or more persons

conspiring to commit an act injurious to trade or com

merce for a violation of Section 62-711, Tennessee Code

Annotated, which provides that any person found guilty

of turbulent or riotous conduct about a restaurant and

other places of public accommodation may be punished

by a fine of not less than $100.00 nor more than $500.00.

A violation of Section 39-1101, Tennessee Code Annotated,

constitutes a misdemeanor and is punishable by a fine of

not more than $1000.00 and confinement in the county

jail or workhouse for not more than one year. The

punishment for the petitioners in this case was fixed at

ninety days in the workhouse and a fine of $50.00.

The conviction was affirmed by the Supreme Court of

Tennessee, and is reported as set out in petitioners’ brief,

. . . . Tenn., ___ , 379 S. W. 2d 214, Petition to Rehear,

. . . . Tenn., . . . . , 379 S. W. 2d 221.

JURISDICTION.

Counsel for the Respondent, State of Tennessee, admits

the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court to review the

opinion of the Supreme Court of Tennessee under the

writ of certiorari granted October 12, 1964.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED.

Counsel for the petitioners insist in their petition for

writ of certiorari that the case requires the determination

of six questions of law but in their brief they list seven

questions to be determined. Counsel for the Respondent

states the substance of these two sets of questions for de

termination as follows:

(1) Whether or not the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in

validated the State statutes under which the petitioners

were convicted (Question 3, Brief and 1 and 2, Petition).

(2) Whether or not the evidence preponderates against

the conviction for unlawful conspiracy and in favor of

the innocence of the accused (Question 4, Brief and Ques

tion 3, Petition).

(3) Whether or not the Supreme Court of Tennessee

sustained petitioners’ conviction upon a basis not liti

gated in the trial court (Question 5, Brief and Question

4, Petition). b

(4) Whether or not the trial judge’s erroneous instruc

tion to the jury that they return a verdict of guilty if

they found petitioners violated Section 62-710, Tennessee

Code Annotated, which authorizes the owners of restau

rants and other places of public accommodation to ex

clude any person for any reason they desire materially

affected the verdict of the jury (Question 5, Brief and

Question 5, Petition).

(5) Whether or not the petitioners were tried before a

fair and impartial jury in view of the fact that some on

voir dire stated that owners of places of public accom

modation should be allowed to exclude Negroes if they

wished (Question 7, Brief and Question 6, Petition).

STATEMENT OF THE EVIDENCE.

In addition to the statement of the evidence contained

in the petition and brief in support thereof, counsel for

the Respondent insists that the following statement of evi

dence also be considered (All page references are to the

printed copy of the transcript).

The petitioners appeared at the entrance of the B & W

Cafeteria, Sixth Avenue, Nashville, Tennessee, about 12:00

p. m., Sunday, October 21, 1962 (Tr. 88-89) at a time when

the entrance was crowded because of people arriving for

lunch after being dismissed from church (Tr. 269-270).

After being informed by Otis Williams, who was employed

by the cafeteria as a doorman that the cafeteria did not

serve colored people and that they could not enter, the

petitioners insisted, “ We are coming in and going to eat

when we git in” (Tr. 270-272).

Petitioners were asked to move along and not to make

any trouble for the restaurant, but they remained in the

vestibule area, approximately 4 feet by 4 feet. The door

man testified that the vestibule was 6 feet by 6 feet four

inches (Tr. 270-271). Only a few people managed to

squeeze through the vestibule (Tr. 91). The City Police

men were called and they escorted the petitioners away

from the entrance (Tr. 92), after they refused to leave

otherwise (Tr. 248-249).

One of the State’s witnesses described the situation as

follows:

“ Well, it was still blocked and people inside

couldn’t get out. And you could see the crowd out

side—wasn’t coming in. And it just seemed like an

awfully long time till the—under the circumstances—•

it wasn’t too long—while that state of confusion ex

isted. And the police came and then they—it was a

question of what to do then. I was talking to some

of the policemen, and I was a lawyer, and they

thought I knew everything and could solve the situa

tion, and I must admit that I didn’t know what to do

myself” (Tr. 188).

This same witness testified that after the vestibule of

the restaurant was cleared, the crowd inside the restaurant

went out and the crowd outside the restaurant entered (Tr.

191-192).

— 4 —

ARGUMENT.

I.

This Honorable Court in Arthur Hamm, Jr. v. City of

Rock Hill, and Frank James Lupper et al. v. State of

Arkansas, 33 U. S. L. Week 4079, December 15, 1964, said :

“ We hold that the convictions must be vacated

and the prosecutions dismissed. The Civil Rights

Act of 1964 forbids discrimination in places of public

accommodation and removes peaceful attempts to be

served on an equal basis from the category of pun

ishable activities. Although the conduct in the pres

ent cases occurred prior to enactment of the Act,

the still pending convictions are abated by its pas

sage.”

If the attempts made by the petitioners in this ease

to obtain service in the B & W Cafeteria on equal basis

Avith all other persons can be characterized as peaceful

attempts, of course, these convictions must be abated.

Counsel for the Respondent insists that the attempts

made by the petitioners in this case to obtain ser\7ice

at the restaurant in question Avere not peaceful attempts.

The indictment alleges in effect that the petitioners con

spired to block by use of physical force the entrance to

the cafeteria in question and prevent patrons inside from

leaving and those outside from entering the cafeteria

(Tr. 4-5). The trial jury found the protest of the peti- \

tioners not to have been made in a peaceful manner. J

This Avas also the conclusion of the trial judge and'the

Supreme Court of Teunesee as evidenced by their ap

proval of the jury verdict.

This Honorable Court in Feiner v. People of State of

New York, 340 TJ. S. 315, 71 S. Ct. 303, 95 L. Ed. 295,

found very similar conduct not to be peaceful as indi

cated by the following excerpt taken from 340 U. S. 320,

71 S. Ct. 306, 95 L. Ed. 300:

“ The language of Cantwell v. State of Connecticut,

1940, 310 U. S. 296, 60 S. Ct. 900, 84 L. Ed. 1213, is

appropriate here. ‘ The offense known as breach of

the peace embraces a great variety of conduct de

stroying or menacing public order and tranquility.

It includes not only violent acts but acts and words

likely to produce violence in others. No one would

have the hardihood to suggest that the principle

of freedom of speech sanctions incitement to riot

or that religious liberty connotes the privilege to

exhort others to physical attack upon those belong

ing to another sect. When clear and present danger

of riot, disorder, interference with traffic upon the

public streets, or other immediate threat to public

safety, peace, or order, appears, the power of the

State to prevent or punish is obvious.’ 310 IT. S. at

page 308, 60 S. Ct. at page 905. The findings of the

New York courts as to the condition of the crowd

and the refusal of petitioner to obey the police re

quests, supported as they are by the record of this

case, are persuasive that the conviction of petitioner

for violation of public peace, order and authority

does not exceed the bounds of proper state police

action. This Court respects, as it must, the interest

of the community in maintaining peace and order

on its streets. Schneider v. State of New Jersey,

Town of Irvington, 1939, 308 IT. S. 147, 160, 60 S. Ct.

146, 150, 84 L. Ed. 155; Kovacs v. Cooper, 1949, 336

IT. S. 77, 82, 69 S. Ct. 448, 451, 93 L. Ed. 513. We

cannot say that the preservation of that interest here

encroaches on the constitutional rights of this peti

tioner.”

— 6 —

It must be remembered, as I know that this Honorable

Court will remember, that it is the conduct of the peti

tioners in question here rather than the conduct of the

owner of the cafeteria involved, and the suggestion in

argument of counsel for the petitioners to the effect that

if the conduct of the restaurant owner was made unlawful,

if not before, by the enactment of the Federal Civil Eights

Act of 1964, the petitioners’ conviction should be reversed

or abated without regard to whether or not they sought

to obtain rights to which they were entitled by unlawful

means or acts contrary to constitutional penal statutes of

this State, should be disregarded. It is noted in the ma

jority opinion of Arthur Hamm, Jr., and Frank James

Lupper, supra, that the legislative history of the Civil

Eights Act indicates that the Act would be a defense to

criminal trespass, breach of the peace, and similar prosecu

tions, citing Senator Humphrey in the Congressional Eec-

ord, May 1, 1964, pages 9162-9163 (IT. S. L. Week 4080,

December 15, 1964). After noting the legislative history

of the Act, it was said that the Act prohibits the applica

tion of State laws in a manner that would deprive per

sons of rights granted under the Act. The case does not

hold that it was the intent of the Act for individuals or

groups of individuals to take the law in their own hands

when rights to which they were entitled were denied. As

a matter of fact, one of the significant secondary purposes

of the Act was to remove conflicts resulting from the de

nial of civil rights to people because of race or color from

the streets into the courtrooms.

Mr. Justice Black in his dissenting opinion had this to

say on the subject:

‘ ‘ I do not understand from what the Court says that

it interprets those provisions of the Civil Eights Act

which give a right to be served without discrimina

tion in an establishment which the Act covers as also

authorizing persons who are unlawfully refused serv

ice a ‘ right’ to take the law into their own hands by

sitting down and occupying the premises for as long

as they choose to stay. I think one of the chief pur

— 8

poses of the 1964 Civil Rights Act was to take such

disputes out of the streets and restaurants and into

the courts, which Congress has granted power to pro

vide an adequate and orderly judicial remedy.”

U. S. L. Week 4084, December 15, 1964.

Title II, Section 207 (b), Civil Rights Act of 1964, is as

follows:

“ The remedies provided in this title shall be the

exclusive means of enforcing the rights based on this

title, but nothing in this title shall preclude any in

dividual or any State or local agency from asserting

any right based on any other Federal or State law

not inconsistent with this title, including any statute

or ordinance requiring nondiscrimination in public es

tablishments or accommodations, or from pursuing

any remedy, civil or criminal, which may be available

for the vindication or enforcement of such right.”

Thus, it appears that in order for a person to obtain

his rights declared by the Civil Rights Act that he is

limited in his remedies to those provided for in the Act.

It certainly does not make these rights dependent upon

a particular individual or a group of individuals’ superior

physical strength or the superiority of weapons available

to him or them as the case may be, and it is submitted

that the petitioners would not wish their rights to be

dependent upon such factors.

II.

It is insisted by counsel for the petitioners that there

is no evidence in the record to support the conviction for

conspiracy. This insistence as understood by counsel for

the Respondent is predicated upon the theories that (1)

petitioners may have been found guilty of seeking service

in a “white only” cafeteria or for obstructing the entrance

to the cafeteria, the first of which was held to be uncon

stitutional by the State Supreme Court and it might be

that the jury based their conclusion of guilt upon the

former since it cannot be determined from their verdict

which of the two acts their findings were bottomed; (2)

there was no evidence the petitioners were disorderly,

that violence was threatened or occurred; (3) there was

no evidence of an agreement among the petitioners to ob

struct the entrance to the cafeteria; and (4) the conduct

of the petitioners in this case was not constitutionally

different from their protesting the denial of their rights

by sitting quietly on a lunch stool inside the restaurant.

A conspiracy as defined by the Supreme Court of Ten

nessee in the case in question and other eases is not ma

terially different from the definition adopted by other

jurisdictions. In order to constitute a conspiracy, there

must be an agreement between two or more persons to do

an unlawful act or a lawful act in an unlawful manner,

coupled with an overt act in furtherance of the agreement.

In the case of American Tobacco Co, v. United States,

328 U. S. 780, 808, 66 S. Ct. 1125, 1139, 90 L. Ed. 1575,

1594, the following language was used regarding a con

spiracy:

“It is not the form of the combination or the par

ticular means used but the result to be achieved that

the statute condemns. It is not of importance whether

the means used to accomplish the unlawful objective

are in themselves lawful or unlawful. Acts done to

give effect to the conspiracy may be in themselves

wholly innocent acts. Yet, if they are part, of the

sum of the acts which are relied upon to effecuate

the conspiracy which the statute forbids, they come

within its prohibition. No formal agreement is neces

sary to constitute an unlawful conspiracy. Often

crimes are a matter of inference deduced from the

acts of the person accused and done in pursuance of

a criminal purpose.”

— 9 —

10 —

Also pertinent is the following excerpt from Ingram v.

United States, 360 IT. S. 672, 679-680, 79 S. Ct, 1314, 1320,

3 L. Ed, 2d 1503, 1509:

“ A conspiracy, to be sure, may have multiple ob

jectives, United States v. Rabinowich, 238 U. S. 78,

86, 35 S. Ct. 682, 684, 59 L. Ed. 1211, and if one of

its objectives, even a minor one, be the evasion of

federal taxes, the offense is made out, though the

primary objective may be concealment of another

crime. ’ ’

The foregoing excerpts considered with the circum

stances recited above in this case appear to be an ade

quate reply to the first and third contentions made that

a conspiracy was not proven. The second contention to j

the effect that there was no evidence of violence, disorder, I

etc., was answered in the reply to the first assignment of 1

error.

The fourth contention to the effect that the conduct of.

the petitioners in this case is identical in principle to

their sitting quietly on a lunch stool inside the restaurant

for the. purpose of protesting a denial of their rights

raises perhaps the ultimate issue in this case. The State

submits there is a big difference between the two types

of acts. For these eight petitioners to sit quietly in the

restaurant and refuse to remove themselves therefrom

after being informed they would not be served, would not

materially obstruct the management’s effort to carry on

the business, whereas their blocking the entrance to the

building to the extent it was blocked tended to paralyze

the operation of the restaurant except for a few customers

who were willing to push their way through the petition

ers’ blockade. As stated above, the petitioners’ conduct

was not peaceful.

The inference to be drawn from the case of Garner v.

State of Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 82 S. Ct. 248, 7 L. Ed.

11 —

2d 207, is that if the petitioners in that case had been

disturbing the peace, their conduct would have been un

lawful. Peaceful protesting in a case of this type is very

analogous to peaceful picketing. Peaceful picketing has

been defined in Goldfinger v. Feintuch, 11 N. E. 2d 910,

annotated 116 A. L. It. 477, and Senn v. Tile Layers Union,

301 IT. S. 468, 57 S. Ct, 857, 81 L. Ed. 1229. It does not

include any form of physical obstruction or interference

with business.

III.

The indictment recited that the B & W Cafeteria was

operating a restaurant not open to Negroes by authority

of Section 62-710, Tennessee Code Annotated. When the

case was decided bv the Tennessee Supreme Court, it was

found unnecessary to determine the validity of this section

of the Code and assumed for the purpose of the appeal

that it was unconstitutional. Now it is insisted that this

amounts to affirming the conviction on a basis not liti

gated in the trial court. Counsel for the Respondent, State

of Tennessee, insists that the Tennessee Supreme Court

only found it unnecessary to determine the validity of

Section 62-710, Tennessee Code Annotated. This is a prac

tice that is almost universal. In Garner v. State of Louisi

ana, supra, it was found by this Honorable Court that

there was no necessity for determining the constitution

ality of the Louisiana statute involved because the facts

did not bring the case within the purview of the statute.

The recitation in the indictment relative to the policy of

the cafeteria, while perhaps not necessary in the indict

ment, did serve to help show that the petitioners knew

they would not be admitted into the cafeteria when they

arrived, and is another circumstance tending to show their

prior agreement either formal or tacit to commit the

conspiracy.

At any rate, the Tennessee Supreme Court found that

the conduct of the petitioners under the circumstances

was unlawful without regard to whether or not the policy

of the cafeteria could legally be supported. On this sub

ject, the Tennessee Supreme Court said in its opinion

(Tr. 324), comparing the circumstances with those in the

cases of Peterson v. City of Greeneville, 373 II. S. 244, 83

S. Ct. 1119, 10 L. Ed. 2d 323; and Lombard v. State of

Louisiana, 373 IT. S. 267, 83 S. Ct. 1122, 10 L. Ed. 2d 339:

“ These two cases are distinguishable from the

instant case. The trespass complained of in the Peter

son and Lombard cases was the act of.sitting on a

stool at a lunch counter. This is basically an inno

cent and unoffensive act. It was only unlawful, in

the eyes~of the city and state concerned, because of a

city ordinance in the Peterson ease and an executive

directive in the Lombard case, both of which required

segregation of the races in public facilities. But

absent the governmental mandate and the color of the

defendants’ skin in those two cases, and the act is

basically unoffensive and innocent. This is not so in

the instant case. Stripped of any question of race and

discrimination, the act complained of is still unlawful.

In the instant case, if these eight defendants had been

white boys, their acts would still have been unlawful.

We cannot escape from the fact that these eight de

fendants were blocking the entrance to the doorway

of the B & W Cafeteria. Regardless of who they were

and why they were blocking the doorway, their con

duct is still basically unlawful” (Tr. 324).

Because of the foregoing, it is insisted that the Su

preme Court of Tennessee did not consider a matter not

litigated at the trial level but even if such had been the

case, there are many instances where cases are decided by

appellate courts on issues not discussed or determined at

the trial level. Elizabethton v. Carter County, 204 Term.

452, 321 S. W. 2d 822; and Frazier v. Elmore, 180 Tenn.

232, 173 S. W. 2d 563. See also Hormel v. Guy T. Helver

ing, 312 U. S. 551, 61 S. Ct. 719, 85 L. Ed. 1037, to the

effect that the rule should not be applied where an injus

tice might be caused.

IV.

The trial judge, after reading the indictment to the

jury setting out that the petitioners were charged with

a conspiracy to commit acts injurious to the trade of the

B & W Cafeteria in violation of Sections 39-1101 and 62-711,

Tennessee Code Annotated, made reference to a violation

of Section 62-710, Tennessee Code Annotated, along with

the first two mentioned in the indictment even though the

latter was a civil statute relative to the conduct of the

business by the owner and a section of the Code which

could not have been violated by the petitioners.

The Supreme Court of Tennessee in its opinion said:

“ A careful reading of the indictment and the whole

charge shows that the only purpose in referring to this

statute was to indicate that this restaurant was being

operated for white people only by authority of this

section. There were no questions raised following the

charge about the propriety of reading it and we do

not see how the reference to a civil statute such as

this, although error, could affect the jury’s verdict,

since there was ample evidence to convict the defend

ants of the offense defined in the other sections of

the code charged” Tr. 321.

The trial judge on each of the three occasions in his

charge when he referred to the civil section of the Code

(Section 62-710, Tennessee Code Annotated), in conjunc

tion with the two criminal sections of the Code indicated

that the three sections prohibited acts injurious to the

business of the restaurant. The error was, therefore, in

14 —

the nature of a typographical or clerical error as obvious

to the jury as to counsel for the petitioners. The only

thing confusing about the instruction was the use of the

number of the Code section, Section 62-710, along with

the number of the two sections of the Code defining the

offense, a. circumstance overcome by the accompanying

statement of the essential elements of the offense in each

instance.

I No objection was made by counsel for the petitioners

/ to this part of the instruction. Because of the nature of

the error as revealed by the circumstances cited above,

counsel for the Respondent insists that the following rule

laid down by this Honorable Court in Palmer v. Hoffman,

.318 U. S. 109, 119-120, 63 S. Ct. 477, 483, 87 L. Ed. 645,

653, is applicable:

“ Under these facts a general exception is not suf

ficient. In fairness to the trial court and to the par

ties, objections to a charge must be sufficiently spe

cific to bring into focus the precise nature of the

alleged error. Where a party might have obtained

the correct charge by speeificially calling the atten

tion of the trial court to the error and where part of

the charge was correct, he may not through a general

exception obtain a new trial. See Lincoln v. Claflin,

7 Wall. (U. S.) 132, 139, 19 L. ed. 106, 109; Beaver v.

Taylor, 93 IT. S. 46, 54, 55, 23 L. ed 797, 798; Mobile &

M. R. Co. v. Jurey, 111 U. S. 584, 596, 28 L. ed. 527,

431, 202 U. S. 600, 611, 50 L. ed. 1162, 1168, 26 S. Ct.

709; Norfolk & W. R. Co. v. Earnest, 229 U. S. 114,

122, 57 L. ed. 1096, 1101, 33 S. Ct. 654, Ann. Cas. 1914C

172; Pennsylvania R. Co. v. Minds, 250 U. S. 368, 375,

63 L. ed. 1039, 1041, 30 S. Ct. 531.”

Y .

Complaint is made that the petitioners were tried before

a jury of white persons who “ admitted a firm and life-

long practice, custom, philosophy, and belief in racial seg

regation” which rendered them disqualified to sit on the

case. The record shows that those who were accepted

stated that they could disregard their attitude on social

questions and perform their duties as jurors on the basis

of the evidence and the law (Tr. 32-39, 44-46, 67-68, 74-80,

and 81-86).

The first reply to this insistence is that the matter

\ of whether or not the owner of the B & W Cafeteria could

1 constitutionally keep it segregated was not an issue before

the jury. It was not made that by the indictment nor the

instruction of the trial judge. It was alleged in the in

dictment as previously stated in this brief to help show

the existence of the conspiracy. So, it was never shown

that the jurors had formed an opinion on the issue to be

tried and consequently, there is no factual basis for this

contention.

But on the other hand since the jurors testified they

could determine the guilt or innocence of the petitioners

fairly on the law and the evidence rather than precon

ceived opinions, they were qualified. Kennedy v. State of

Tennessee, 186 Tenn. 310, 210 S. W. 2d 132. See also the

following excerpt from Green et al. v. United States, 19

F. 2d 850, 855:

“ Error is assigned to the denial of the defendants’

challenge of certain of the jurors for actual bias.

While it was shown that they had heard about the

case, and some of them had formed an opinion as to

the guilt or innocence of the defendants, all admitted

in substance that it was not a fixed opinion, that

it could be disregarded, and that they would endeavor

to render a verdict according to the evidence, under

the instructions of the court. We think there was

no error. Section 331, Washington Compiled Statutes

(Remington), provides: ‘Although it should appear

that the juror challenged has formed or expressed an

opinion upon what he may have heard or read, such

opinion shall not of itself be sufficient to sustain the

challenge, but the court must be satisfied, from all

the circumstances, that the juror cannot disregard

such opinion and try the issue impartially.’ We are

not convinced that there was abuse of discretion in

denying the challenge. Spies v. Illinois, 123 U. S. 131,

8 S. Ct. 22, 31 L. Ed 80.”

The rule of Thiel v.. Southern Pac. Co., 328 U. S. 217,

66 S. Ct. 984, 90 L. Ed. 481, and two other cases cited

by counsel for the petitioners to the effect that in both

criminal and civil proceedings litigants are entitled to

an impartial jury drawn from a cross-section of the

community, is not shown to be violated in this case.

It is not even insisted that all the members of the jury

expressed an opinion that restaurant owners had a right

to exclude any person, including Negroes, from their

place of business. It is not shown that they were preju

dicial at all. The most that is shown is that these jurors

were mistaken about the law, or what the law ought to

be, which is not unusual among people generally or even

among lawyers.

In view of the foregoing, counsel for the Respondent,

State of Tennessee, earnestly insists that the judgment

of the Supreme Court, State of Tennessee, in this case

be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

GEORGE F. McCANLESS,

Attorney General,

State of Tennessee,

By THOMAS E. POX,

Assistant Attorney General,

State of Tennessee.

— 16 —

I certify that I forwarded a copy of this Reply Brief

for the State of Tennessee to the Honorable Jack Green

berg and the Honorable James M. Nabrit, III, Attorneys

at Law, 10 Columbus Circle, New York, New York 10019,

and to the Honorable Avon N. Williams and the Honor

able Z. Alexander Looby, Attorneys at Law, McClellan-

Looby Building, Charlotte at Fourth, Nashville, Ten

nessee, on this the . . . . day of ........................ , 1965.

Thomas E. Fox,

Assistant Attorney General,

State of Tennessee.

— 17 —