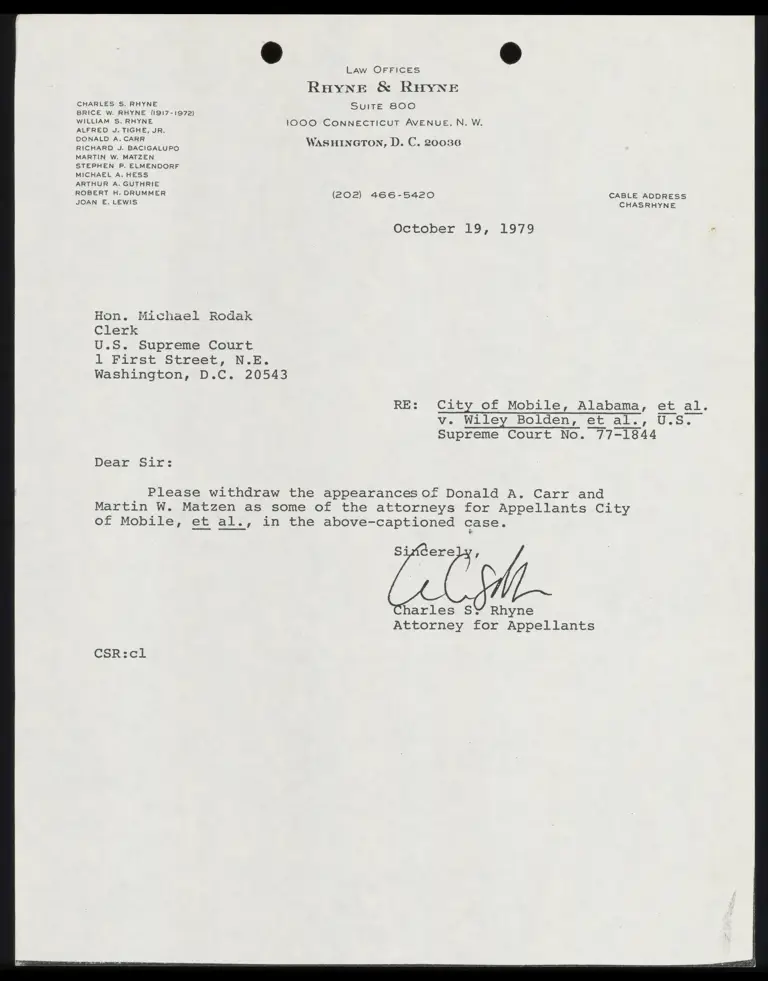

Correspondence from Rhyne to Clerk

Public Court Documents

October 19, 1979

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Correspondence from Rhyne to Clerk, 1979. 531076d2-cdcd-ef11-8ee9-6045bddb7cb0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b43b6091-6d94-418b-9ecc-0d509d81b3c3/correspondence-from-rhyne-to-clerk. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Law OFFICES

Rayne & REYNE

CHARLES S. RHYNE : SUITE 800

BRICE W. RHYNE (1917-1972)

WILLIAM S. RHYNE 1000 CoNNECTICUT AVENUE, N. W.

ALFRED J. TIGHE, JR.

DONALD A. CARR WasHiNGTON, D. C. 20036

RICHARD J. BACIGALUPO

MARTIN W. MATZEN

STEPHEN P. ELMENDORF

MICHAEL A. HESS

ARTHUR A. GUTHRIE

ROBERT H. DRUMMER (202) 466-5420 CABLE ADDRESS

JOAN E. LEWIS CHASRHYNE

October 19, 1979

U.S. Supreme Court

l First Street, N.E.

Washington, D.C. 20543

RE: City of Mobile, Alabama, et al.

Vv. Wiley Bolden, et al., U.S.

Supreme Court No. 77-1844

Dear Sir:

Please withdraw the appearances of Donald A. Carr and

Martin W. Matzen as some of the attorneys for Appellants City

of Mobile, et al., in the above-captioned case.

harles S¥ Rhyne

Attorney for Appellants

CSR:cl