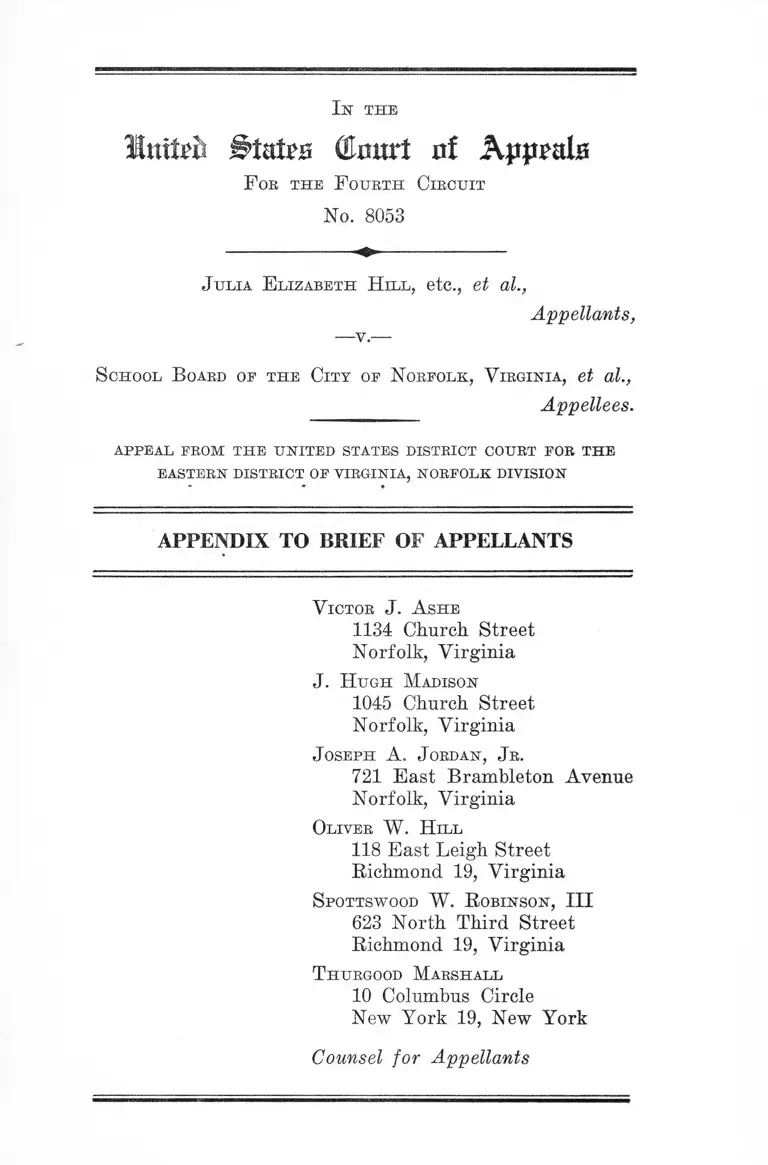

Hill v. City of Norfolk, VA School Board Appendix to Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1959

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hill v. City of Norfolk, VA School Board Appendix to Brief of Appellants, 1959. 10d56e36-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b4400f57-44a1-4daf-91a3-b4da23e6eb07/hill-v-city-of-norfolk-va-school-board-appendix-to-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

Itttteb (Emort of Kppmlz

F or t h e F ourth C ircu it

No. 8053

J ulia E liza beth H il l , etc., et al.,

—v.-

Appellants,

S chool B oard of t h e C ity op N orfolk , V irg in ia , et al.,

Appellees.

appeal from t h e u n it e d states district court for t h e

EASTERN DISTRICT OP VIRGINIA, NORFOLK DIVISION

APPENDIX TO BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

V ictor J . A sh e

1134 Church Street

Norfolk, Virginia

J . H ugh M adison

1045 Church Street

Norfolk, Virginia

J o seph A . J ordan, J r .

721 East Brambleton Avenue

Norfolk, Virginia

Oliver W . H ill

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

S pottswood W . R obinson , I I I

623 North Third Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

T hurgood M arshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Counsel for Appellants

PAGE

I. Opinions and Orders ......................................... 2a

Memorandum, Filed September 8, 1959 ...... 2a

Order, Filed September 8, 1959 ..................... 14a

Memorandum, Filed May 8, 1959 ................. 17a

Memorandum, Filed September 18, 1958 ...... 28a

II. Excerpts from Reporter’s Transcript of Trial

Proceedings Had on August 27-28, 1959 .......... 36a

Stipulation ........................... .......................... 37a

J . J . Brewbaker ........... ...................... ...... . 42a

E. L. Lamberth ............................................... 63a

III. Excerpts from Reporter’s Transcript of Trial

Proceedings Had on August 18-22, 1958 ........... 110a

J . J . Brewbaker ............................................ 110a

Thomas H. Henderson __ _______ __ ____ 121a

IV. Amended Procedures Relating to the Assign

ment of Pupils to Public Schools of the City of

Norfolk, Filed March 6, 1959 ............................. 143a

INDEX TO APPENDIX

A P P E N D I X

I n t h e

lutttb Bintts (Emtrt nt Kppmlz

F or t h e F ourth C ircuit

No. 8053

J ulia E lizabeth H ill , etc., et al.,

Appellants,

v.

S chool B oard op t h e C ity op N orfolk,

V irg in ia , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT POE THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OP VIRGINIA, NORFOLK DIVISION

Civil Action File No. 2214

L eola P earl B eck ett , et al.,

vs.

T h e S chool B oard of th e City op N orfolk, V a., et al.,

2a

I n* t h e

■201-

Im t^ Emtvxct (to rt

F oe t h e E astern D istrict oe V irginia

Norfolk Division

Civil Action No. 2214

L eola P earl B ec k ett , etc., et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

T h e S chool B oard of t h e City op N orfolk,

V irg in ia , et al.,

Defendants.

Memorandum— Filed Septem ber 8 , 1959

The prior proceedings in this litigation are fully doc

umented in Beckett v. The School Board of the City of

Norfolk, 148 F. Supp. 430, aff. sub nom. School Board of

the City of Norfolk v. Beckett (School Board of the City

of Newport News v. Atkins), 4 Cir., 246 F. (2d) 325, cert,

den. sub nom. School Board of City of Newport News, Vir

ginia, et al v. Atkins, et al, 355 U. S. 855, 78 S. Ct. 83,

2 L. Ed. (2d) 63; School Board of City of Norfolk, 260 F.

(2d) 18; Beckett v. The School Board of the City of

Norfolk (unreported opinion of May 8, 1959). See also,

the related cases of James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331

(three-judge court); James v. Duckworth, 170 F. Supp.

342, aff. sub nom. Duckworth v. James, 4 Cir., 267 F. (2d)

224; Beckett v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 2 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 337 (otherwise unreported); Beckett v. School

Board of City of Norfolk, 3 Race Rel. L. Rep. 942-964

3a

(otherwise unreported); Harrison v. Day, 200 Va. 439,

106 S. E. (2d) 636; Adkinson v. The School Board of City

of Newport News (unreported opinion of May 12, 1959).

On August 13, 1959, the School Board and its Division

Superintendent filed two reports herein, not in response

to any order, but apparently by reason of a conflict occa

sioned by action of the Pupil Placement Board, a state

agency established under the provisions of Sec. 22-232.l et

seq., of the Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended. The two re

ports may generally be characterized as (1) relating to

action taken on applications of certain Negro children for

admission into public schools of the City of Norfolk previ

ously attended solely or predominantly by children of the

white race for the school year beginning September 8, 1959,

and (2) relating to action taken with respect to children who

are affected by the construction of Bosemont Elementary

School and Coronado Elementary School in areas which

are predominantly occupied by members of the Negro race.

Upon the filing of said reports the Court convened counsel

for a pre-trial conference and, having been verbally advised

- 202-

in advance of the filing of said reports that a conflict

had arisen by reason of the action of the Placement Board

in declining to follow the recommendation of the School

Board in assigning at least two Negro children to

schools attended solely or predominantly by white children,

the Court invited, but did not command, the attendance

of counsel for the Placement Board at said pre-trial con

ference.

The pre-trial conference was held on August 14, 1959,

attended by counsel for the plaintiffs and the School Board.

Counsel for the Placement Board could not attend due

Memorandum—Filed September 8, 1959

4a

to other engagements. The plaintiffs verbally moved the

Court to add the Placement Board and its individual mem

bers as parties defendant to this action, and further asked

leave to file amended and/or supplemental pleadings here

in. In light of the Court’s ruling in Adkinson v. The School

Board of the City of Newport News, Civil Action No. 642,

Newport News Division, holding the Pupil Placement Act

constitutional on its face, it was apparent to the Court

and counsel for the School Board that the Placement Board

and its individual members were “conditionally necessary”

parties to the action. An order was entered on August 14,

1959, adding the additional parties defendant; reference to

said order being hereby made.

Within the time prescribed by said order, the plaintiffs

filed certain motions for further relief, together with a

motion requesting leave to file a complaint in intervention.

The Placement Board and its members appeared specially

and moved to abate the proceedings until such time as these

defendants were enabled to prepare their defense and an

swer the appropriate pleadings. The School Board and its

Division Superintendent likewise filed pleadings in re

sponse to plaintiffs’ motions, but it is unnecessary to dis

cuss these matters.

At the hearing held on August 27-28, 1959, the Court,

without objection of any party, granted the plaintiffs’

motion to file a complaint in intervention. Counsel for

the Placement Board contended that his clients were not

yet parties to the litigation, but Rule 21, Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure, clearly grants such authority where it

is said:

“Parties may be dropped or added by order of the court

on motion of any party or of its own initiative at any

stage of the action and on such terms as are just. Any

Memorandum—Filed, September 8, 1959

5a

claim against a party may be severed and proceeded

with, separately.”

To delay the hearing beyond August 27-28 would, in effect,

deprive the plaintiffs of an opportunity to secure the relief

sought as the public schools are scheduled to open on

September 8, 1959, and, with Labor Day weekend inter-

—203—

veiling, it would be impossible to schedule a later hearing

prior to the opening of the school term. However, as this

Court said in Adkimson and District Judge Bryan so aptly

stated in Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington

County, 166 F. Supp. 529, the impact of any decree would

be upon the School Board in charge of the schools as the

local Board and its employees actually admit or reject

the students.

To afford the Placement Board and its members of an op

portunity to answer the pleadings and prepare a defense,

the Court directed the additional parties defendant to file

an answer or other appropriate pleading within twenty

days from August 27, 1959. At the same time the Court

announced that no action taken at the August 27-28 hear

ings would result in any order directing or prohibiting

the Placement Board and its members from doing any act

with respect to said plaintiffs, other than to file the re

sponsive pleading as aforesaid. By reason of the com

mencement of the school term on September 8, 1959, the

Court further stated that it would hear the evidence, in

cluding the testimony of the individual members of the

Placement Board who appeared in court in response to

the order of August 14, 1959, to determine whether the

Negro children seeking relief were entitled to physical ad

mission into certain public schools of the City of Norfolk

Memorandum—Filed September 8, 1959

6a

as of September 8, 1959, on a temporary basis, subject to

further action of this Court in ascertaining whether said

children should be assigned or enrolled therein after hear

ing from the Placement Board subsequent to the filing of

a responsive pleading.

With one exception, the decision of the Court as to the

temporary admission or denial of the plaintiffs’ requests

was announced from the bench following the conclusion of

the evidence and argument of counsel. The Court having

reserved the right to make more formal findings of fact

and conclusions of law, this memorandum follows.

Patricia Amelia Turner and Reginald A. Young

These two Negro children attended predominantly white

schools during the previous school term, February-June,

1959. They satisfactorily completed their work in these

schools. If they were white children, they would admittedly

be assigned and enrolled in Norview High School and

Maury High School respectively, for the school year be

ginning September 8, 1959. They reside within the school

district which would ordinarily suggest that they are en

titled to attend the schools to which the School Board has

recommended they be assigned.

—204—

Initially, the School Board did not request any action of

the Placement Board by way of assignment or enrollment

into the schools attended predominantly by white children;

it being the view of the School Board that action with

respect to these children was a routine promotion. In this

action, the School Board was in error. Sec. 22-232.7 of the

Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended. These children grad

uated from one school to another within the school divi

Memorandum— Filed\ September 8, 1959

7a

sion, and hence are subject to the legal and constitutional

actions of the Placement Board.

By letter dated July 21, 1959, the School Board advised

the Placement Board of the so-called routine promotion of

these two children into schools attended predominantly by

white children. The Placement Board immediately re

quested the School Board to forward applications for en

rollment pursuant to §22-232.7. The School Board com

plied.1 At the hearing of August 27-28 the Placement

Board advised that it had taken no action on these ap

plications, but suggested that it would act during the fol

lowing week. On August 28, the Court directed the School

Board to physically admit, on a temporary basis subject

to the further order of this Court, the aforesaid Patricia

Anzella Turner and Reginald A. Young to Norview High

School and Maury High School respectively.

By letter dated September 3, 1959, addressed to the

Division Superintendent of Schools, the Placement Board

advised that the two Negro children had been assigned to

Booker T. Washington School, a school heretofore at

tended solely by Negro children. In explanation of this

action the Placement Board said :

“This action is consistent with its policy that it will

not place a Negro child in a white school or a pre

dominantly white school, or a white child in a Negro

school or a predominantly Negro school, unless or

until an appeal is made to the Board and a hearing

held. Such a hearing would provide the Board with

an opportunity to ascertain the true facts and cir

cumstances surrounding each particular case and

Memorandum—Filed September 8, 1959

1 The evidence does not reveal whether the School Board forwarded ap

plications for all so-called routine promotions. Apparently it did not.

8a

thereby enable it, in the exercise of quasi-judicial func

tions, to take that action which, in the opinion of the

Board, would be to the best interest of each individ

ual child.”

—205—

The policy declared by this letter does not appear in the

statute; nor has it heretofore been placed in written form.

It came to light during the interrogation of a member

(Randolph) and the other two members (White and Far

ley) concurred therein. Both White and Farley stated or

strongly suggested that they could never vote to assign

a Negro child, irrespective of the child’s qualifications and

geographical location of the child’s home, into a school

attended solely or predominantly by children of the white

race, as it was their view that such action would not be in

the best interest of the child.

Issues pertaining to the constitutionality by way of ap

plication of the action and policy of the Placement Board

are reserved for further hearing, but it is sufficient to

state that a prima facie showing of unconstitutional appli

cation of the Pupil Placement Act has been established to

justify the action in physically admitting these children

on a temporary basis to schools other than as designated

by the Placement Board.

Moreover, the delay in acting upon these two applica

tions has deprived the parents of these children of an ef

fective right to protest the Board’s action under §22-232.8.

The cumbersome procedure set forth in the Act, when con

sidered in light of the Board’s recently announced policy,

would result in no action being taken for an approximate

period of sixty days. In the interim, without intervention

by the Court, the children would be required to attend

the school to which they were assigned by the Placement

Memorandum—Filed September 8, 1959

9a

Board. As lias so frequently been said, the administra

tive remedy must be adequate, not futile.

Daphne Perminter and Anita Mayer

These Negro children were recommended by the School

Board for assignment and enrollment into Suburban Park

Elementary School and Maury High School respectively.

The Placement Board, without considering the aptitude

tests and interviews so capably conducted by the School

Board, assigned the children to schools attended solely by

Negro children, apparently in accordance with its pre

viously unannounced policy as indicated by its letter of

September 3, 1959. True, the parents of these children did

not seek the administrative review by way of protest as

provided by §22-232.8, but the evidence disclosed that

neither the Placement Board nor the School Board had

advised the parents of the action taken by the Placement

Board. The fifteen day period for making any written

protest had expired before the court hearing. The Place-

—206—

ment Board conceded that it never notified the parents of

the action taken, and had never requested the School Board

to so notify them, although the Placement Board had as

sumed that the School Board would take such action.2

Upon a review of the tests and interviews, together with

a consideration of the location of the children’s homes, the

Court directed that these two children be physically ad

mitted, on a temporary basis subject to further order of

the Court, to the schools as recommended by the School

Board.

2 Apparently the Placement Board has now decided to notify the parents

in all instances where its action is contrary to the recommendation of the

School Board, as a copy of the letter of September 3, 1959, was sent to the

parents.

Memorandum—Filed September 8, 1959

10a

Gloria Scott and Bobby J. Neville

These children, having previously attended schools which

have heretofore been attended only by children of the

Negro race, now seek admission into Blair Junior High

School and Norview Junior High School respectively. They

were required to take tests and be subjected to interviews

by the School Board. They graduated from one school to

another within the school division. They reside within a

school district which would suggest their attendance at

Blair and Norview if they were white children.

By its opinion of May 8, 1959, this Court approved the

requirement of tests and interviews, if equally applied to

children of the same class and race. Blair and Norview

are already racially mixed. The Court said:

“It is assumed that, with respect to the schools already

racially mixed, the ‘unusual circumstances’ would exist,

and that applicants (both white and Negro) applying

for transfer to, or initial enrollment in, such racially

mixed school will be required to submit to tests and

interviews.”

The School Board incorrectly, but not deliberately, inter

preted this language as excluding the necessity of giving

tests and interviews to children of the white race gradu

ating from one school to another within the school division.

In commenting upon the language of the United States

—207-

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in Hamm v.

County School Board of Arlington County, 4 Cir., 264 F.

(2d) 945, this Court said in its opinion of May 8, 1959:

“It does suggest, however, that there should be equality

of treatment as to children seeking admissions to par

ticular schools under particular conditions.”

Memorandum—Filed September 8, 1959

11a

It is apparent that the School Board has unconstitu

tionally applied its standards, procedure, and criteria in

requiring these two Negro children to take tests and sub

mit to interviews, whereas white children similarly situated

were excused from compliance. The School Board argues

that graduation is “in the stream”, but this is a “racial

stream” so condemned by the decisions of courts of last

resort.

The unconstitutional application compels temporary ac

tion by the Court as the tests and interviews must be dis

regarded. Actually one of these children is on the border

line scholastically in any event, whereas the other child

is probably not presently equipped to maintain the work.

The children have been admitted to the schools of their

choice on a temporary basis and, in order to make an

appropriate recommendation to the Placement Board at a

later date, it is suggested that a study be made of these

two children for a period of 60 to 90 days and, predicated

upon their accomplishments (or lack of same) after said

period, the School Board shall make an appropriate recom

mendation to the Placement Board as to assignment or

enrollment, which said recommendation shall be made with

out regard to the tests and interviews heretofore given.

If aptitude tests are to be hereafter given to these two

children, they shall be likewise given to all children in the

particular grade in which the Negro child is in attendance.

Mary Rose Foxworth

This Negro child has applied for admission into Subur

ban Park Elementary School, one heretofore attended only

by white children but racially mixed on a temporary basis

by reason of the action aforesaid as to Daphne Perminter.

At the request of all counsel, the evidence as to this child

was heard in chambers. Prom the statements there made,

Memorandum—Filed September 8, 1959

12a

it appears that the child fulfills every requirement for ad

mission to Suburban Park. The action of the School Board

in declining to recommend her assignment is not legally

sufficient and involves circumstances over which the child

had no control. The child will be admitted on a temporary

basis, subject to the further order of the Court, and the

School Board will, at the expiration of sixty to ninety days,

make an appropriate recommendation to the Placement

Board predicated solely upon the child’s accomplishments

(or lack of same) during said period.

—208—

The Remaining Children

The applications of all other Negro children are denied

for reasons more adequately stated in the Court’s opinion

of May 8, 1959. They are either deficient in their school

work or in their tests as constitutionally administered.

They fall within the classification that, for the time being

at least, reasonable tests and standards must be estab

lished to regulate the procedures to be followed in an or

derly transition period. There is no challenge made as to

the honesty and integrity of the School Board in admin

istering these tests. The decision of the School Board is

essentially one of judgment and should not be arbitrarily

disregarded. It is argued that (1) there are white children

in the same grade who do not maintain the same required

standards and (2) white children residing within school

districts in which Negroes are the predominant race are

not required to attend the school attended solely or pre

dominantly by Negroes. These facts do not per se prove

discrimination. They are among the problems which the

Supreme Court said in Brown must be elucidated, assessed,

and solved in good faith implementation of governing con

stitutional principles. Had the Supreme Court intended

Memorandum—Filed September 8, 1959

13a

to confine its ruling to a geographical determination of

each case, it would have said so. Of course, white children

living within an area which is predominantly Negro have

a perfect right to be considered for admission into a pre

dominantly Negro school, but this does not suggest that

they must attend such school. Nor is the School Board

compelled to admit children into a grade, merely because

other children already in attendance at that grade may be

of equal or lower mentality.

The Rosemont and Coronado Schools

In predominantly Negro areas, the School Board is now

constructing two elementary schools which will be attended

this school year solely by Negroes in the absence of a re

quest for a white child to attend. The contention is made

that this action defeats the spirit of the Brown decision.

To the contrary, the evidence establishes that other schools

are also being constructed in areas occupied predominantly

by white children, which schools are substantially the same

as the Rosemont and Coronado schools. Undeniably, the

construction of these schools will result in decreased at

tendance at schools already affected by the mixing of

races, but to hold in line with plaintiffs’ contention would

result in a serious impediment to the School Board and

local governing body in erecting schools when and where

—209-

necessary. The Negro children living within the normal

Rosemont and Coronado school districts should attend

these schools or otherwise provide for their education.

W alter E. H offman

United States District Judge

Norfolk, Virginia

September 8,1959

Memorandum-Filed. September 8, 1959

14a

I k t h e

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F oe t h e E astern D istrict oe V irginia

Norfolk Division

Civil Action No. 2214

-210-

Order——Filed September 8, 1959

[ same t it l e ]

Upon consideration of the proceeding herein on August

27-28, 1959, and for reasons stated in a memorandum this

day filed, which said memorandum is adopted by the Court

in lieu of specific findings of facts and conclusions of law,

it is

Ordered :

(1) That plaintiffs’ complaint for intervention be, and

the same hereby is, filed as of August 27, 1959;

(2) That the responsive pleadings of The School Board

of the City of Norfolk, Virginia, and J. J. Brewbaker,

Division Superintendent of Schools be, and the same here

by are, filed as of August 27,1959;

(3) That the motion of the defendants, Pupil Placement

Board and its individual members, to abate these proceed

ings is sustained in part and denied in part, and said de

fendants shall file their responsive pleadings herein within

twenty (20) days from August 27,1959;

(4) That the following Negro children shall be physi

cally admitted to the public schools set forth herein on

15a

Order—Filed September 8, 1959

September 8, 1959, on a temporary basis subject to further

order of this Court:

Name of Child Admitting School

Patricia Anzella Turner

Reginald A. Young

Daphne Perminter

Anita Mayer

Gloria Scott

Bobby J. Neville

Mary Rose Foxworth

Norview High School

Maury High School

Suburban Park Elementary School

Maury High School

Blair Junior High School

Norview Junior High School

Suburban Park Elementary School

With respect to the children whose last names are Turner,

Young, Perminter and Mayer, the School Board of the City

of Norfolk is not required to report further to the Pupil

Placement Board. With respect to the children whose last

names are Scott, Neville and Foxworth, the School Board

of the City of Norfolk shall make such study and there

after render such report and recommendation to the Pupil

Placement Board as may be suggested by the memorandum

filed herein, unless otherwise ordered by the Court.

As to each of said children so physically admitted on a

—211-

temporary basis, subject to the further order of this Court,

they shall be accorded all of the rights and privileges and

charged with all of the duties and responsibilities accorded

to, or imposed upon, white children in the grade and class

to which they may be directed to attend, pending the fur

ther order of this Court.

(5) The following children are denied the right to attend

the following public schools for the school year commenc

ing September 8,1959:

16a

Order—Filed September 8, 1959

Name of child

Dorothy Elaine Tally

Calvin Edward Winston

James Alfred Tatem

Gladys Lynell Tatem

Rosa Lee Tatem

William Henry Neville

Wilhelmina Scott

Marian Scott

Julia Elizabeth Hill

Phyllis Delores Russell

Charlene L. Butts

Minnie Alice Green

Melvin G. Green, Jr.

Cloraten Harris

Rosa Mae Harris

Glenda Gale Brothers

Sharon Venita Smith

Edward H. Smith, III

Requested School Denied

Granby High

Suburban Park

Suburban Park

Suburban Park

Suburban Park

Norview High

Maury

Maury

Maury

Norview Elementary

Norview Elementary

Norview Elementary

Norview Elementary

Norview Elementary

Norview Elementary

Norview Elementary

Norview Elementary

Norview Elementary

To which action of the Court, the parties adversely af

fected except.

W alter E. H offman

United States District Judge

Norfolk, Virginia

September 8,1959

17a

I n th e

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F oe t h e E astern D istrict oe V irginia

Norfolk Division

—149—

Memorandum— Filed May 8, 1959

[ same t it l e ]

This case is again before the Court following the opinion

of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit filed on October 2, 1958. The School Board of the

City of Norfolk, et al v. Beckett, 4 Cir., 260 F. (2d) 18. As

to the admission of 17 Negro children into previously all-

white schools, the action of the School Board in granting

the applications and the procedure adopted by the Court

was affirmed. As to the 134 Negro applicants denied ad

mission by the Board, the case was remanded for further

action as this Court had reserved for further consideration

certain questions with respect to the validity of the stand

ards, criteria and procedures promulgated by the Board

and applied to the rejected applicants.

There are, therefore, three remaining questions.

I

Following the assignment of the 17 Negro children to

schools previously attended only by white children, the six

schools to which these 17 children were assigned were

closed by operation of certain laws previously enacted by

the General Assembly of Virginia. Plaintiffs thereupon

filed a supplemental complaint alleging the unconstitution

ality of such statutes and requesting an injunction to pro-

18a

Mbit their enforcement. A district court of three judges

as provided by §2284 of Title 28, U. S. C. A., was desig

nated, process was issued, various motions were filed, and

the defendants answered the supplemental complaint.

Since the designation of the three-judge court, the cases

of Harrison v. Day, 200 Va. 439, 106 S. E. (2d) 636, and

James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331, have been decided.

The highest court of Virginia held that several of the laws

were in violation of the State Constitution. A three-judge

court in James v. Almond, supra, ruled that certain statutes

were unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States. The Attorney

General of Virginia has stated that a suggestion of “moot

ness” will be filed with the United States Supreme Court

- 1 5 0 -

in James v. Almond as the controverted laws have now

been repealed. A petition for rehearing has been denied

in Harrison v. Day.

The three-judge court designated herein is no longer

necessary subject to the concurrence of the other members

of that court, an order will be entered dissolving the three-

judge court to the end that further proceedings wall be

conducted without regard to the supplemental complaint

and the motions and answer in response thereto. The plain

tiffs will recover of said defendants their costs incident

to the supplemental proceedings.

II

In this Court’s memorandum filed on September 18, 1958,

there were eight Negro children (included among the 134

applications remanded to this Court by the Circuit Court

of Appeals) whose applications were rejected by the Board

due to the pending construction of a new school known as

Memorandum—Filed May 8, 1959

19a

Rosemont Elementary School scheduled for occupancy by

September 1, 1959. Reference is also made to the Court’s

remarks to the School Board under date of August 25,

1958. The rejections were predicated upon the theory of

“too frequent transfers” as the evidence suggests that if

the Rosemont School is ready for occupancy, these eight

Negro children would ordinarily be assigned to Rosemont

in September, 1959.

The Court upheld the Board’s action in denying these

requests for transfer to Norview Elementary School, and

nothing further could be added to the comments previously

made. The City Attorney of the City of Norfolk has again

assured the Court that the Rosemont School will be ready

for occupancy as of the first day of the regular school

term in September, 1959. The applications of the eight

Negro children will remain pending without the necessity

of further action by said plaintiffs, unless said plaintiffs

file a supplemental request for assignment elsewhere, and

if the Rosemont School is not ready for occupancy on the

assured date, the Board shall comply with its duty to assign

said children to Norview Elementary School in the absence

of any good cause indicating that other action should be

taken; said good cause to the contrary to be reported to

the Court prior to August 15, 1959. If the Rosemont School

is ready for occupancy, the Board may make such appro

priate assignment as it deems best in compliance with the

law.

I l l

The third and final question concerns the validity of the

standards, criteria and procedures promulgated by the

Board pursuant to a resolution adopted July 17, 1958.

—151—

The resolution was amended on September 5, 1958, and

Memorandum—Filed May 8, 1959

20a

counsel agree that the decision of this Court will be under

the assumption that the amended resolution was in effect.

Of the remaining 126 applicants, approximately 63 failed

or refused to take the scholastic achievement test, or other

wise failed or refused to submit to personal interviews,

in accordance with the procedures adopted by the Board.

Approximately 34 applicants failed or refused to file written

objections to the action of the Board, as required by the

Court’s order fixing a deadline for objections to be filed.

'One applicant was rejected for geographical reasons, he

being already assigned to a school nearer to his home

than the school to wdiieh he was seeking a transfer. The

remaining 28 applicants were rejected as their scholastic

achievements and abilities did not justify the transfers

and enrollments sought.

While there are some differences of opinion as to the

scholastic achievement necessary to consider the appropri

ateness of a transfer or initial enrollment, the action of

the Board on this point is not the subject of attack. All

concede that it is proper to subject children to reasonable

achievement tests before authorizing a transfer. Implicit

in the testimony of plaintiffs’ expert educator is the thought

that, for the time being at least, reasonable tests and stand

ards must be established during the transition period.

Such action is for the benefit of both races as well as the

children. This is not to say that the attendance of Negro

children in schools attended predominantly by children of

the opposite race should forever be confined to such Negro

children who have superior intelligence. As stated by the

Supreme Court in Brown, “additional time [may be] nec

essary to carry out the ruling in an effective manner.”

Before proceeding to a consideration of the constitution

ality of the standards, criteria and procedures adopted by

Memorandum—Filed May 8, 1959

21a

the Board, it should be noted that, following a closure

period from September through January, the six affected

schools of Norfolk were reopened on February 2, 1959,

with the 17 Negro children in attendance. To the ever

lasting credit of the School Board, the teachers, the chil

dren of both races, and the administrative authorities of

the City of Norfolk and State of Virginia, it can truthfully

be said that there has been no violence and administrative

problems have been at a minimum. The attitude of the

Board, following receipt of the Court’s remarks of August

25, 1958, has been one of cooperation with a sincere effort

—152—

to comply with the law and, at the same time, to maintain

public education so essential to this community. The per

sonnel of the Board may be changed in the future, but

this Court will have no difficulty in ascertaining when there

exists a deliberate scheme to violate the law in problems

confronting the Board and the Court under the Brown

decision. We must, however, deal with the present and

not the future.

The plaintiffs contend that the standards, criteria and

procedures as amended by the resolution of September 5,

1958, are unconstitutional on their face for the reason that

the tests and interviews are, and will be, required in all

“unusual circumstances,” and that a Negro child applying

for admission into a school attended solely by white chil

dren or into any school wherein the races are or will be

mixed constitutes an “unusual circumstance.” Counsel con

cede that if the tests and interviews are required of all

children seeking initial enrollment or transfer into a school

without regard to “unusual circumstances,” the procedure

would be constitutional on its face.

Memorandum—Filed May 8, 1959

22a

Undoubtedly these standards, criteria and procedures

may be unconstitutionally applied, but the intent of this

ruling is to limit the same within the narrow scope of its

constitutionality without regard to its application. The

application of such standards, criteria and procedures will

remain essentially with the Board, subject to scrutiny by

the Court upon request of the aggrieved child. Much will

depend upon the Board itself—a cooperative Board has

no reason to doubt the action of any court—a Board which

is adamant and refuses to recognize the Brown decision

will have continuous troubles.

The United States Supreme Court has never suggested

that mass mixing of races is required in the public schools.

The underlying ruling is that no child shall be denied ad

mission to a public school on the sole basis of race or color.

Indeed, the Supreme Court recognized that a variety of

local problems would arise when it said:

“Full implementation of these constitutional principles

may require solution of varied local school problems.

School authorities have the primary responsibility for

elucidating, assessing, and solving these problems;

courts will have to consider whether the action of

school authorities constitutes good faith implementa

tion of the governing constitutional principles. Be

cause of their proximity to local conditions and the

possible need for further hearings, the courts which

—153—

originally heard these cases can best perform this

judicial appraisal.

“ . . . Traditionally, equity has been characterized by

a practical flexibility in shaping its remedies and by a

facility for adjusting and reconciling public and pri

Memorandum—Filed May 8, 1959

23a

vate needs. These cases call for the exercise of these

traditional attributes of equity power. At stake is the

personal interest of the plaintiffs in admission to

public schools as soon as practicable on a nondis-

criminatory basis. To effectuate this interest may call

for elimination of a variety of obstacles in making the

transition to school systems operated in accordance

with the constitutional principles set forth in our May

17, 1954, decision. Courts of equity may properly take

into account the public interest in the elimination of

such obstacles in a systematic and effective manner . . .

“ . . . To that end, the courts may consider problems

related to administration, arising from the physical

condition of the school plant, the school transportation

system, personnel, revision of school districts and at

tendance areas into compact units to achieve a system

of determining admission to the public schools on a

nonracial basis, and revision of local laws and regu

lations which may be necessary in solving the fore

going problems. They will also consider the adequacy

of any plans the defendants may propose to meet

these problems and to effectuate a transition to a

racially nondiscriminatory school system.”

By reason of the Virginia school-closing laws, now de

clared unconstitutional and recently repealed, the Board

has been powerless to submit any plan to meet the prob

lems created by the Brown decision. Whatever the label

may be, the resolution of July 17, 1958, as amended, is

nothing more than a plan. It is submitted to the Court

without the force of law—it is the Board’s view that this

plan will, for the time being, constitute an orderly transi

tion to a racially nondiscriminatory school system. It is

Memorandum,—Filed May 8, 1959

24a

subject to change in the future and the case remains within

the jurisdiction of the Court. If it becomes apparent that

the Board is repeatedly applying the standards, criteria,

and procedures in an unconstitutional manner for the pur

pose of preventing an orderly transition, the Court may

permit the plaintiffs and subsequent applicants to disre

gard these requirements.

The Board has, for many years, required tests and inter

views in “unusual circumstances”. They have been re

quired of children of all races and colors and will con

tinue to be so required. The only reason the Board now

desires to adopt written procedures limiting the tests and

interviews to “unusual circumstances” is to avoid the ex

pense and trouble of testing children seeking routine trans

fers or initial enrollment where there are no complications

as to scholastic ability, geographical areas, etc. The Board’s

- 1 5 4 -

counsel candidly states that, as to all applications giving

rise to the mixing of races in public schools, the circum

stances will be deemed “unusual” for an indefinite period

of time. It is assumed that, with respect to the schools al

ready racially mixed, the “unusual circumstance” would

exist, and that applicants (both white and Negro) ap

plying for transfer to, or initial enrollment in, such racially

mixed school will be required to submit to tests and inter

views.

It cannot be successfully contended that the standards,

criteria and procedures are unconstitutional on their face.

The case of Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Educa

tion, 162 F. Supp. 372, affirmed on limited grounds, 358

U. S, 101 is authority for the proposition that the Board

here may impose standards and criteria which may be

vague and indefinite. Merely because all applicants for

Memorandum—Filed May 8, 1959

25a

admission to schools which will result in the mixing of

races will be, for the time being, classified as resulting

in an “unusual circumstance” affords no basis for saying

that the applicant is being denied a constitutional right.

We are here dealing not with the individual right, but with

the resulting condition brought about by the granting of

that right. The constitutional right lies in the denial of

admission because of race-—not in the prerequisites lead

ing up to such denial. Again, however, the procedures

adopted must be reasonable and not so burdensome as to

be tantamount to a denial of the constitutional right. In

the instant proceeding that question is not before the

Court; the sole contention being that both white and Negro

children seeking admission or transfer into schools wherein

the races will be mixed constitutes an unconstitutional act

in that it is discriminatory on its face.

Certainly since August, 1958, and during 1959, it cannot,

be said that the action of the Board is the equivalent of an

evasive scheme to perpetuate segregation. Proof of this

statement lies in the fact that 17 Negro children were ad

mitted under the standards, criteria and procedure so

established.

It is presumed that the standards, criteria and proce

dures will be administered fairly by a competent School

Board upon whom the primary responsibility rests. The

end result of this holding is merely to say that to classify

schools attended by children of both races as an “unusual

circumstance” is not on its face an unconstitutional act.

—155—

If the standards, criteria and procedures should be applied

in such a manner as to deprive an applicant of his con

stitutional right to attend the school of his choice without

regard to race, all other factors being such as to entitle him

Memorandum—Filed May 8, 1959

26a

to enter such school, the Court’s duty would then be plain

and the standards, criteria and procedures would be de

clared unconstitutional in their application. Likewise, the

standards, criteria and procedures must be equally applied

to all applicants seeking enrollment in or transfer to a

school already attended by children of both races, but, as

noted, this falls within the category of the application of

the procedures promulgated by the Board.

This conclusion is not reached without consideration of

the recent decision of Hamm v. County School Board of

Arlington County, 4 Cir., ----- F. (2d) ----- (March 19,

1959), in which the court remanded for further proceed

ings the cases of 26 Negro children whose applications for

admission were rejected by the Board with this action be

ing approved by the district judge. A portion of the opinion

is as follows:

“We find evidence in the record that their applications

for transfer were subject to tests that were not ap

plied to the applications of white students asking trans

fers.”

It will be noted that the court does not specifically state

that such action is discriminatory per se. It is not said

that the requirement of tests and interviews pursuant to a

plan or resolution is unconstitutional on its face. It does

suggest, however, that there should be equality of treat

ment as to children seeking admissions to particular schools

under particular conditions. The Arlington case was re

ferred back to the trial court for more appropriate con

sideration prior to the opening of the 1959-60 school year.

It is true that, in the instant case, no white children were

applicants for admission to a school previously attended

only by Negro children. Thus, under the plan presented

Memorandum-—Filed May 8, 1959

27a

it became unnecessary to subject any white children to

tests or interviews as the “condition” was not an “unusual

circumstance”. Moreover, the Negro children did not tile

individual applications for admission to specific schools

until after the close of the normal school year in June,

1958. It would have been an impossible task to require

tests and interviews of all children once the school closed

for the summer season. However, as noted, the Board’s

standards, criteria and procedures were promulgated to

—156-

meet a “condition” and not to unduly restrict an individual

right.

Holding that the action of the Board in denying the ap

plications of 134 Negro children for admission to certain

public schools previously attended only by white children

was not arbitrary, capricious or illegal, that the standards,

criteria and procedures are not unconstitutional on their

face, the Board’s determination is A pproved.

W alter E. H offman

United States District Judge

Memorandum—Filed May 8, 1959

Norfolk, Virginia

May 8,1959

28a

I n t h e

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or t h e E a s t e r n D is t r ic t o f V ir g in ia

Norfolk Division

[ s a m e t it l e ]

—97-

Memorandum-—Filed September 18, 1958

In lieu of specific findings of fact and conclusions of law,

this memorandum is prepared in final determination of

matters pending herein, save and except questions involv

ing the validity of the assignment plan promulgated by the

School Board of the City of Norfolk requiring all children

applying for initial enrollment or transfer into a public

school formerly attended solely by students of the opposite

race to submit to certain achievement tests and personal

interviews.1 Action upon this latter question is deferred

pending receipt of a brief from defendants and possible fur

ther argument.

It is unnecessary to relate the history of these proceed

ings to and including August 29, 1958, as the same is fully

documented. See Beckett v. School Board of the City of

Norfolk, 148 F. Supp. 430, 2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 46, holding

the Pupil Placement Act unconstitutional on its face upon

consideration of defendants’ motion to dismiss, and 2 Race

1 White children seeking initial enrollment in, or transfer to, a pre

viously all-Negro school would likewise be required to submit to such tests and

interviews. Of course, as the resolution is now drawn, if any public school

in the City of Norfolk is ever attended by a child of the opposite race, the

resolution of the School Board would no longer be applicable as to that school,

and tests and interviews would no longer be necessary where the school has

already been integrated.

29a

Eel. L. Rep. 337 (otherwise unreported) determining the

merits of the case. The orders entered by this Court, in

cluding the ruling upon the constitutionality of the Pupil

Placement Act, were appealed to the United States Court

of Appeals and affirmed by the latter court, 246 F. (2d) 325.

Certiorari was denied by the United States Supreme Court,

355 U. S. 855.

Following the action by the School Board in denying the

applications of 151 Negro children for enrollment in, or

- 9 8 -

transfer to, certain schools formerly occupied solely by

white children, the Court, after hearing evidence and argu

ment of counsel, convened the members of the School Board

in open court and made certain remarks. Counsel for the

respective parties agreed that it would be appropriate for

the Court to advise the School Board members as to the

applicable law, but counsel were not required to agree to

the correctness of the legal conclusions as stated by the

Court—in fact, counsel neither requested advance infor

mation as to the Court’s remarks, nor were they advised

of same.

The Court’s remarks to the School Board members on

August 25, 1958, are attached hereto and incorporated

herein by reference.

In compliance with the direction of the Court, the School

Board submitted and filed a report on August 29, 1958, a

copy of which is attached and incorporated herein by refer

ence ; the effect of which was to deny the applications of 134

Negro children, and further stating that 17 Negro children

“will be assigned to and enrolled in the grades and schools

set opposite their names for the school year 1958-’59.” Con

temporaneous with the filing of said report, the School

Board filed a motion to defer, until September, 1959, the

enrollment of the 17 Negro children under the assignments

Memorandum—Filed September 18, 1958

30a

set forth in the report of August 29, 1958. By order entered

on September 2, 1958, the latter motion was denied; the

Court reserving, however, the right to reconsider its action

following the argument and determination of the case of

Aaron v. Cooper, then pending before the United States

Supreme Court on petition for certiorari to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. On Septem

ber 12, 1958, the United States Supreme Court affirmed the

action of the Eighth Circuit, which latter court had reversed

the decision of .District Judge Lemley from the Eastern

District of Arkansas. There is no longer any legal or justifi

able reason further to consider defendants’ request for a

one year deferment. As long ago as February 12, 1957, the

Superintendent of Schools testified that, in his opinion, but

for the enactment of certain laws by the General Assembly

of Virginia, the City of Norfolk by a process of gradual

desegregation could achieve good faith implementation and

compliance with the Supreme Court decision without any

insurmountable difficulties. More than eighteen months

later, immediately following their first step toward good

faith compliance and implementation, a delay of an addi

tional year is requested. It is urged that time is required to

—99—

“educate the adults” as to the problem presented but defen

dants concede that they are presently powerless to embark

upon such an educational program frowned upon by state

authorities. Moreover, under state law, the affected schools

must be closed by action of the Governor. To grant a delay

of one year would only postpone this eventuality. Regret

table though it may be, conditions have not improved in

Virginia since the second decision in Brown v. Board of

Education rendered on May 31, 1955. In all probability the

people of Virginia will ultimately be required to choose

Memorandum—Filed September 18, 1958

31a

between two alternatives, namely, a complete abolition of

the public school system throughout the entire State of

Virginia, or acceptance in some form and to some extent of

the law of the land as interpreted by the United States

Supreme Court.

By an order of the Circuit Court of the City of Norfolk,

Virginia, entered on August 18, 1958, by two Justices of the

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, the defendants were

enjoined by the state court from assigning or enrolling any

children in the public schools of the City of Norfolk. On

September 12, 1958, the defendants filed a petition in this

Court, together with a motion for temporary injunction,

to prevent the state court plaintiffs from interfering fur

ther, directly or indirectly, with the final order of this Court

heretofore entered on February 26, 1957. An order to show

cause was likewise issued against the state court plaintiffs

and their attorney. These matters were heard on Septem

ber 17, 1958, and this Court entered an injunction on Sep

tember 18, 1958, a copy of said injunction and findings of

facts and conclusions of law being attached hereto and

incorporated herein by reference. Presumably the School

Board will now proceed to make the assignments of the 17

Negro children in accordance with its report of August 29,

1958.

The School Board took and filed certain exceptions to the

remarks of the Court submitted to the Board on August 25,

1958. These exceptions must be overruled. At no time

did this Court tell the Board that it was required to admit

any particular child; nor has the Court assigned any child

to any school. Admittedly the Board was faced with a

difficult alternative—one being to comply with the law—

the other being to subject itself and its members to a pos

sible citation for contempt. The Board elected to comply

Memorandum— Filed September 18, 1958

32a

with the law as interpreted by this Court in light of other

decisions. The “racial tension” and “isolated child” factors,

as referred to in the Court’s remarks of August 25, 1958,

are the only general headings under which the Board ad

mitted any Negro children into previously all-white schools.

Racial tension as a defense has been effectively disposed of

by the decision in Aaron v. Cooper. If the theory of the

— 100—

“isolated child” constitutes just cause for denying the ad

mission of a Negro child, compliance with the law of the

land as interpreted by the Supreme Court would never be

possible in the southern states. Moreover, the so-called

“token integration” has been approved by district and ap

pellate courts sitting in other southern states.

Aside from the validity of the Board’s resolution estab

lishing the criteria and procedure with respect to tests and

interviews, the plaintiffs and intervenors make only one

serious attack upon the correctness of the Court’s remarks

to the Board on August 25, 1958. This involves the subject

of “Too Frequent Transfers” heretofore discussed in the

remarks aforesaid. With some variations in mileage not

deemed pertinent, the following individual applications of

Negro children were considered and rejected by the Board,

which action is now approved by the Court. In stating the

distances to the various schools, references to Oakwood

indicate a previously all-Negro school ; to Norview a pre

viously all-white school; and to Rosemont, the new school

which will be completed by September, 1959, and to which

school the Board has stated that each Negro applicant

would be transferred, not because of race or color, at the

commencement of the 1959-’60 school year. The following

facts are found:

Memorandum—Filed September 18, 1958

33a

Memorandum—Filed September 18, 1958

Application of Melvin G. Green, Jr.:

Distance from home to Oakwood 1.4 miles

Distance from home to Norview .3 “

Distance from home to Rosemont .3 “

Application of Glenda Brothers:

Distance from home to Oakwood

Distance from home to Norview

Distance from home to Rosemont

1.8 miles

1.1 “

1.1 “

Applications of Clorateen and Rosa Mae Harris:

Distance from home to Oakwood 1.3 miles

Distance from home to Norview .5 “

Distance from home to Rosemont one short block

Application of Charlene Butts:

Distance from home to Oakwood .7 mile

Distance from home to Norview .7 “

Distance from home to Rosemont .4 “

Applications of Slier on and Edward JI. Smith:

Distance from home to Oakwood 1.3 miles

Distance from home to Norview .7 “

Distance from home to Rosemont .6 “

The Board considered, in line with the Court’s remarks,

the newT unit area for the Rosemont school, as well as trans

portation facilities and dangers encountered in crossing

highways. These questions are essentially for the Board to

determine and this Court cannot say that the Board’s action

— 101—

is arbitrary, capricious, or discriminatory.

Plaintiffs argue that the Court was in error in holding

that, in the exercise of sound discretion and where proof

convincingly establishes that the second transfer must here

34a

after be made to Rosemont, the constitutional right of the

child could be deferred for the one year period under these

peculiar circumstances. Plaintiffs cite a line of pre-Brown

decisions relating to the “separate but equal” doctrine,

including Carter v. School Board of Arlington County, 4

Cir., 182 F. (2d) 531; McKissick v. Carmichael, 4 Cir., 187

F. (2d) 949; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339

U. S. 637; and Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629. The theme

of these cases is that the constitutional right is personal

and present. Plaintiffs overlook, however, the Brown deci

sion which requires in the public schools (as contrasted

with state-supported institutions of higher learning) a

balancing of the public and private needs, and further pro

vides that “once such a [prompt and reasonable] start has

been made, the courts may find that additional time is neces

sary to carry out the ruling in an effective manner.” Can

didly, plaintiffs’ counsel are unable to explain the constitu

tional deferment of rights established by recent public

school decisions approving plans calling for “stair-step”

desegregation such as Slade v. Board of Education of Har

ford County, 4 Cir., 252 F. (2d) 291, cert. den. 357 U. S. 906.

In the latter case the plan provided for gradual desegrega

tion of public schools. Certainly the constitutional right of

the child was personal and present but, in balancing the

public and private needs, the courts gave a stamp of ap

proval to the deferment of these rights which, in effect,

totally deprived certain children of such rights as they

would undoubtedly have completed the public schools before

their rights could be asserted in some instances. The situ

ation may be entirely different where no public school is

available such as in the recent Warren County school case

from Virginia decided by District Judge Paul in which a

stay was denied by Chief Judge Sobeloff. In the case

Memorandum—Filed September 18, 1958

35a

at bar there is, at most, a deferment of such rights for a

period of one year, at the end of which the children may

again make application. Bearing in mind that the Board

is better able to determine the adverse effect of “too fre

quent” transfers, it cannot be said that the Board acted

arbitrarily, capriciously, or even without wisdom.

An order will be entered in accordance with this memo-

— 102—

randum, which, together with the references attached and

incorporated herein, is adopted by the Court as its findings

of fact and conclusions of law.

Memorandum—Filed September 18, 1958

United States District Judge

Norfolk, Virginia

September 18, 1958

36a

I n th e

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or t h e E astern D istrict op V irginia

Norfolk Division

Excerpts from Reporter’s Transcript of Trial

Proceedings Had on August 27-28, 1959

[ s a m e t it l e ]

T rial P roceedings

Norfolk, Virginia

August 27, 28, 1959

B e f o r e :

H onorable W alter E. H o pfm an ,

United States District Judge.

— 2—

A p p e a r a n c e s :

S pottswood R obinson , Esq.

Oliver H il l , Esq.

V ictor A s h e , E sq .

J oseph J. J ordan, Esq.

J. H ugo M adison, Esq.

Attorneys for the Plaintiffs.

A lbertis S. H arrison , Esq.

W illia m D. M cI lw a in e , Esq.

L eonard H. D avis, Esq.

L eig h D. W illia m s , Esq.

W. R. C. C ocke, Esq.

Attorneys for the Defendants.

A. B. S cott, Esq.

Attorney for The Pupil Placement Board.

Stipulation

—40—

The Court: Gentlemen, we have had a nice fifty-

minute recess. I assume that you probably have

been working to the end that you may be able to

shorten the testimony; is that correct!

Mr. Hill: That is correct, sir.

The Court: All right. You may proceed then,

Mr. Hill.

Mr. Hill: We have decided to let Mr. Davis make

the initial statement as to what we—

The Court: He is the official stipulator, if I re

member correctly.

Mr. H ill: Stipulator, yes, sir.

Mr. Davis: If your Honor please, as is obvious, I

got elected again. If your Honor please, we have

followed very much the same procedure that was in

voked in the hearing of these cases last year in these

respects: We have available, as exhibits for the

Court—counsel for the plaintiffs have a copy, we

have a copy, and any witnesses will also have a copy

from which they can testify—the test records, the

records of the interviews and the summary sheets

as to each of the children who applied for admis

sion, transfer or initial enrollment for the ’59-’60

school year; and as I recall it, there are, I believe,

fifteen of those children who are contesting the ac

tion that was taken by the School Board in its

recommendations. I say we have those test records

—41—

for all who applied for ’59. I should have said we

have the test records for all of those fifteen because,

as I understand it, we are not interested at this time

38a

in any of those who did not file their objections by

Wednesday of last week, I believe it was.

In addition to those fifteen, there are two children

who were admitted to previously all white schools

for the ’58-’59 session who graduated from the schools

to which they were admitted and whom the School

Board promoted to higher schools, which are now

either all white or predominantly all white. I think

predominantly all white. That makes seventeen.

Then there were eight other children who are in the

contesting group; those eight being the eight who

were denied admission to Nor view Elementary

School for the ’58-’59 session on the ground of too

frequent transfer.

If the Court would think it in order, we would

like to divide this into two phases; first, the phase

dealing with the seventeen and let the evidence be

introduced pertaining to those, and then later on

take up the eight children. I believe it will make for

less confusion.

With regard to those seventeen, if the Court also

feels it is in order, possibly the Court would like to

introduce these papers either as Court exhibits or

—42—

would like for us to do it right now and get those

into the record. As I recall it last year, the Court

introduced those as Court exhibits.

The Court: I believe that is correct. We will

follow the same procedure, then.

Mr. Davis: All right, sir. Would you like for

me to name these children as I pass these up I

The Court: I think it would be satisfactory to

say Court Exhibit No. 1 and the name of the child.

Stipulation

39a

Mr. Davis: Court Exhibit No. 1, Daphne Della

Perminter; Court Exhibit No. 2, Anita D. Mayer;

Court Exhibit No. 3, Eosa Lee Tatem; Court Ex

hibit No. 4, Gladys Lynell Tatem; Court Exhibit No.

5, James Alford Tatem; Court Exhibit No. 6, Cal

vin Edward Winston.

If your Honor please, some of these papers have

numbers on them. I would ask you to disregard

them. They do not mean anything for this purpose.

Court Exhibit No. 7, Julia Elizabeth Hill; Court

Exhibit No. 8, Marian Scott; Court Exhibit No. 9,

Gloria Scott; Court Exhibit No. 10, Wilhelmina

Scott; Court Exhibit No. 11, William Henry Neville;

Court Exhibit No. 12, Bobby J. Neville; Court Ex

hibit No. 13, Dorothy Elaine Tally; Court Exhibit

No. 14, Phyllis Delores Bussell.

With the Court’s permission, we would like to

reserve Court Exhibit No. 15. Now—

—43—

The Court: You may just submit that to the Clerk

and let the Clerk make a notation of it, if you care to,

and mark it as a Court exhibit.

Mr. Davis: All right, sir.

(The above described documents were marked

and received in evidence as Court Exhibit Nos.

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15,

respectively.)

Mr. Davis: We do not have any such test papers,

or interview papers or summary sheets as to Pa

tricia A. Turner and Beginald Young. They were

the two who were admitted last year and who went

up on routine promotions. There was no occasion

Stipulation

40a

to test them or have any interviews with them. With

reference to the categories, there are two into which

—correction—I started to say eleven—two into which

twelve of these children fall; category No. 1, geo

graphical boundaries, and the child who falls within

that category is Phyllis Delores Russell. Category

No. 2 is scholastic achievement, too low. If your

Honor please, I am not sure that is exactly the ter

minology that was used last year, but it means the

same thing. It was felt that the scholastic achieve

ment of these children was too low to justify recom

mending that they be transferred or enrolled. The

—4 4 -

eleven children who fall within that category are

Rosa Lee Tatem, Gladys Lynell Tatem, James Al

ford Tatem, Calvin Edward Winston, Julia Eliza

beth Hill, Marian Scott, Gloria Scott, Wilhelmina

Scott, William Henry Neville, Bobby J. Neville and

Dorothy Elaine Talley.

That concludes, I believe, the stipulation or infor

mation with regard to the seventeen children in this

particular phase of the case.

Have I stated it correctly, gentlemen ?

Mr. Robinson: Yes.

Mr. Hill: Except we also stipulated—

Mr. Davis: Yes, yes. Now, if your Honor please,

we would also like for the record to show, if it is

permissible with the Court, that counsel for all par

ties wish the evidence that has been taken before to

be considered insofar as it may be relevant to the

matters which we are considering today.

Am I correct, gentlemen?

Stipulation

41a

The Court: What evidence do you speak of now,

the evidence taken last year ?

Mr. Davis: Yes.

The Court: At the hearings of last year?

Mr. Davis: Yes, sir.

The Court: Such as the testimony of Mr. Brew-

baker, Mr. Lamberth and Dr. Henderson—

—45—

Mr. Davis: Yes, sir.

The Court: —and Mr. Schweitzer? I believe that

is, in substance, most of them.

Mr. Davis: That is correct. We will put on addi

tional evidence, but there was considerable evidence

taken last time with reference to qualifications of

witnesses and these various tests that were used

and how they were considered, and so forth, and in

sofar as that evidence is relevant, we thought it

would save time not to have to review all of that

again now.

Gentlemen, was there anything else ?

Mr. Hill: Except that you mentioned that there

were two categories. You only put in one. You are

not going to put the others in until we get to it; is

that the idea? Either way.

Mr. Davis: We do not have any such papers as

these in connection with those eight.

Mr. Hill: Okay.

The Court: There is one other case that counsel

have conferred with the Court about and I do not

think there is any need to discuss it.

Mr. Hill: No, sir.

Mr. Davis: None. May we call, then, please, Mr.

J. J. Brewbaker?

Stipulation

42a

J. J. Brewbaker—for Defendants—Direct

—46—

J. J. B rew baker, ca lled a s a w itn ess by a n d on b eh a lf

of th e d e fen d an ts , h a v in g been d u ly sw o rn , te s tif ied as

follows:

Direct Examination by Mr. Davis:

# * # # #

Q. Are you familiar, Mr. Brewbaker, with those assign

ment standards, criteria and procedures? A. I am familiar

with those.

Q. Directing your attention to the fifteen children who

—47—

applied for transfers to or initial enrollment in the public

schools of the city for the ’59-’60 school year, which fifteen

children are among the seventeen that I named just a

moment ago, were those procedures applied to those chil

dren? A. They were, Mr. Davis.

Q. Did the applications of those children involve un

usual circumstances ? A. They did.

# * # # #

—52—

# * # *

The Court: May I ask Mr. Brewbaker a question

at this point ?

Mr. Davis: Yes, sir.

-5 5 —

* * # # #

Q. What I am driving at is, if I were on the Placement

Board, for the life of me I could not determine, unless it

was called to my attention, whether the child was white or

colored or to what school the child was going to. The Place

ment Board certainly has no individual or any personal

43a

association with Gwendolyn Smith, I do not believe? A.

The Placement Board, though, knows which of our schools

are for colored children and which are for white children,

and when—

Q. Well, schools are not for colored and white. A. Well,

they know which schools are occupied by colored children,

generally speaking—which are predominantly occupied, or

otherwise.

# # # * #

—57—

Cross Examination by Mr. Robinson:

Q. Mr. Brewbaker, I believe I am correct in my under

standing that Julia Elizabeth Hill, Marian Scott and Wil-

helmina Scott applied for a transfer to Maury High School,

did they not? Julia Elizabeth Hill, Marian Scott and Wil-

helmina Scott? A. That’s correct, Mr. Bobinson.

Q. Isn’t it also a fact that one or more Negro students

attended Maury High School for the school session 1958-’59?

A. Yes, we had one there.

Q. All right, sir. Now, Gloria Scott made application for

a transfer to Blair Junior High School, correct? A. That’s

right.

Q. And for the 1958-’59 school session you had one or

more Negro students enrolled there? A. We had two.

Q. William Henry Neville made application for transfer

to Norview High School, correct? A. That’s right.

Q. How many Negro students did you have attending

that school during the last school session? A. We had

seven.

—58—

Q. Bobby J. Neville made application for a transfer to

Norview Junior High School. Did you have any Negro

J. J. Brewbaker—for Defendants—Cross

44a

students in attendance during the last school session at

that school? A. We had five.

Q. Dorothy Elaine Tally made application for transfer

to Granby High School; isn’t that correct? A. That’s cor

rect.

Q. Did you have any Negro students attending that

school during the last school session? A. We had one.

Q. Now, as I understand, Mr. Brewbaker, in the cases

of all of the—one, two, three, four, five—seven students

that I mentioned, when their applications for transfer were

received you submitted them to tests and you called their

parents down for interviews in connection with those ap

plications; isn’t that so? A. That’s correct.

Q. You had white children who were seeking transfer

to Maury High School, to Blair Junior High School, to Nor-

view High, Norview Junior High and Granby High School

for the 1959-’60 school session? A. We did.

Q. Did you have any white children making application

to any of those schools ? A. I ’m sure we did.

—59—

Q. Are you in a position to say that you had white chil

dren who were seeking transfer to all of those schools for

the coming school session? A. I wouldn’t say from actual

knowledge, but I ’m reasonably sure we did.

Q. How about white initial enrollees in those schools,

are you in a position to say whether you had white chil

dren making application for initial enrollment in any or

all of those schools for the 1959-’60 school session? A. I

am sure we have had.

Q. All right. Did you submit any tests or require any

interviews with reference to any white child who was seek

ing initial enrollment in or transfer to any one of these

J . J. Brewbaker—for Defendants—Cross

45a

schools that I have mentioned? A. We have been giving

tests and interviews.

Q. Did you give those tests and interviews to all of the

white children seeking admission or initial enrollment in

those schools? A. I am under the impression we did, Mr.

Robinson.

Q. Could you verify your impression one way or the

other, Mr. Brewbaker, not now, but before this hearing

concludes? A. I think Mr. Lamberth could, because he

had the general administration of that.

Q. We will ask Mr. Lamberth. Now, Mr. Brewbaker,

—60—

did you administer any tests or interviews for purposes of