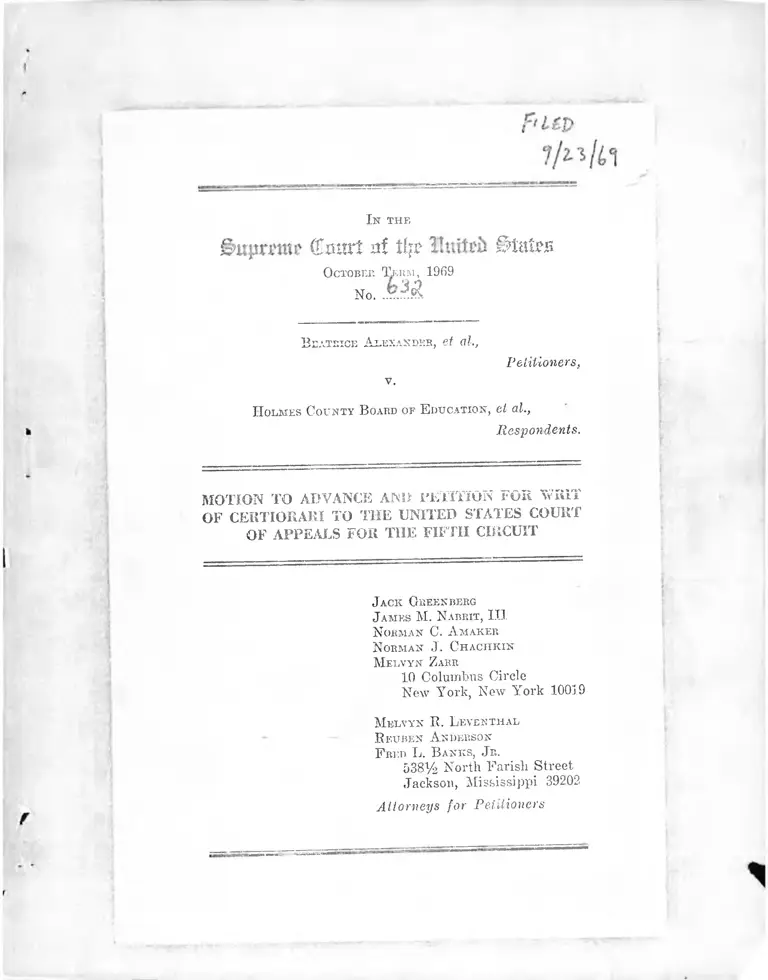

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education Motion to Advance and Petition for Writ of Certiorari; Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Company Brief for the United States Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

September 23, 1969 - September 23, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education Motion to Advance and Petition for Writ of Certiorari; Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Company Brief for the United States Amicus Curiae, 1969. e2b0ed8b-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b449b66d-58ba-45c0-80b4-692b4bfdd5de/alexander-v-holmes-county-board-of-education-motion-to-advance-and-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-alexander-v-gardner-denver-company-brief-for-the-united-states-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

(flcurt at tî r State#u

October Term , 1969

No. r .M .

B eatexce Alexander, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

H olmes County B oard of E ducation, el al.,

Respondents.

MOTION TO ADVANCE AND PETITION FOR WRIT

OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT

OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N orman C. A makek

N orman J. Chachkin

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Melvyn R. Leventhal

R euben A nderson

F red Ij. B anks, J r.

538y2 North Parish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

TAGS

Motion to A dvance.................................................................. 1

P etition F or W rit of Certiorari:

Opinions Below ....................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ............................................................... 2

Question Presented.................................................... 2

Constitutional Provision Involved ......................... 2

Statement .................................................................. 2

Reasons for Granting the Writ

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Review and

Reverse the Court of Appeals’ Delay of

Desegregation Because the Time for Delay

Has Run O ut....................................................... 11

Conclusion ................................................................. 19

A ppendix A—

Opinion of the District Court Approving Freedom

of Choice Plans ....................................................... la

Order of the District Court dated May 16, 1969 .... 20a

Order of the District Court dated May 16, 1969 .... 21a

Order of the District Court dated May 29, 1969 .... 22a

A ppendix B—

Letter Directive of the Court of Appeals of June

25, 1969 ................................................ 24a

Opinion of the Court of Appeals of July 3, 1969 .... 28a

{

I■ ji

A

. j

-

i\,£S

Modification of Order of the Court of Appeals of

July 25, 1969 ............................................................. 38a

A ppendix C—

Letter of August 11, 1969 Transmitting Desegre

gation Plans From United States Office of Edu

cation to the District C ourt..................................... 40a

Attachment A Annexed to Letter of August

11, 1969 ............................................................... 45a

Attachment B Annexed to Letter of July 11,

1969 ...................................................................... 51a

Letter of August 19, 1969 From the Secretary of

the Department of Health, Education and Wel

fare to the Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals .... 53a

Order of the Court of Appeals of August 20, 1969 .. 55a

A ppendix D—

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law of the

District Court Entered August 26, 1969 ................ 56a

A ppendix E—

Order of the Court of Appeals of August 28, 1969 .. 71a

A ppendix F—

Opinion in Chambers of Mr. Justice Black of

September 5, 1969 .................................................. 79a

— T able of Cases

Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181 (5th Cir. 196S) ...... 5, 7,13

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....3,10,11

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) ....3,11,16

PAGE

iii

Coffey v. State Educational Finance Commission, 29G

F. Supp. 1389 (S.D. Miss., 1969) ................................. 6

Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

328 F.2d 408 (5th Cir. 1964) ........................................ 12

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) ................................................... 3, 4,7

Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) .................. 12

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, No. 26450 (5th

Cir., May 28, 1969) ....................................................... 7

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969) ............................. 13

Jackson Municipal Separate School District v. Evers,

357 F.2d 653 (5th Cir. 1966) ....................................... 5

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938) 18

Price v. Denison Independent School District Board of

Education, 348 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1965) ..................11,16

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965) (injunction pend

ing appeal) ; 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966) ..............12,13

United States v. Barnett, 330 F.2d 369 (5th Cir. 1963) .... 11

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

District, 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969) ...................... 13

United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate School

District, 410 F.2d 626 (5tli Cir. 1969) ......................... 13

A

i

il

iv

PAGE

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F.2d 836 (5tli Cir. 1966), affirmed en banc 380

F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied 389 U.S. 840

(1967) ............................................................................ 13

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

5th Cir., No. 27444, June 26, 1969 ............................... 18

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963) ...................... 11

S tatutes

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) ...........................................................• 2

28 U.S.C. §1343(3) .......................................................... 2

42 U.S.C. §1981 ................................................................ 2

42 U.S.C. §1983 ................................................................ 2

Title VI, Civil Rights Act of 1964 ................................ 12,13

Other A uthorities

United States Commission on Civil Rights, Federal

Enforcement of School Desegregation, (September

11, 1969) ...................................................................... 13, 14

&upn>»tr ffiourt 0! % lltiilrit gtaiw;

October T erm, 1969

No.............

B eatrice A lexander, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

H olmes County B oard or E ducation, et al.,

Respondents.

MOTION TO ADVANCE

Petitioners, by their undersigned counsel, move the Court

to advance consideration and disposition of this case, and

m support thereof would show that this case presents an

issue of national importance requiring prompt resolution

by this Court, for the reasons stated in the annexed petition

for writ of certiorari.

W herefore, petitioners pray that the Court: 1 ) consider

this motion in vacation; 2) shorten the time for filing re

spondents’ response to 15 days; 3) consider the petition

during the conference week of October 6, 1969, or as soon

thereafter as possible; and 4) grant certiorari and sum

marily reverse the judgment below or set an expedited brief-

2

ing schedule a

argument.

a

■ .

l ad^ance the case on the calendar for

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N orman C. A maker

N orman J . Chachkin

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Melvyn R. Leventhal

R euben A nderson

F red L. B anks, J r.

538y2 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

Attorneys for Petitioners

• - .. .

I n t h e

&npmn? (Hmtrt of % lutted §>M?b

October T erm, 1969

No.............

B eatrice A lexander, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

H olmes County B oard of E ducation, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit entered August 28, 1969, amending its order

of July 3, 1969, as modified July 25, 1969.

Opinions Below

The order of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit of which review is sought is unreported and is

set forth in Appendix E. Earlier opinions of the Court of

Appeals and of the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Mississippi are unreported and are set

forth in Appendices A through D.

2

1

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit was entered August 28, 1969 (Appendix

E, p. 71a,infra).

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. $1254(1) to review the Court of Appeals’ order de

laying the implementation of school desegregation plans in

14 school districts in Mississippi.

Question Presented

Did the Court of Appeals err in granting 14 Mississippi

school districts an indefinite delay in implementing school

desegregation plans based upon generalized representations

by the United States Department of Health, Education and

Welfare that delay was necessary for preparation of the

communities?

Constitutional Provision Involved

This case involves the Equal Protection Clause of Sec

tion 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States.

Statement

These cases1 test how much longer Negro schoolchildren

in 14 substantially segregated school districts in Mississippi

1 These cases were filed in the United States District Court for

the Southern District of Mississippi between the years 1963 and

1967. Jurisdiction was predicated upon 28 U.S.C. §1343(3) and

42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1983 and the Due Process and Equal 1 rotection

Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. Plaintiffs in school deseg

regation cases in Mississippi often sue several school boards located

within the same geographical area under one civil action number;

3

will have to wait to exercise their right to a desegregated

education decreed by this Court more than 15 years ago in

Brown v. Board of Education,2

For 10 years after Brown v. Board of Education, the

public schools of Mississippi remained totally segregated.

Thereafter, the school boards involved in this litigation

adopted freedom of choice plans indistinguishable from that

condemned last year by this Court in Green v. County

School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968).

These freedom of choice plans did not work to disestablish

the dual school system. Indeed, the token results achieved

the nine cases brought here by this petition involve fourteen sepa

rate school districts.

First, there are three eases wherein suit was brought by Negro

schoolchildren against six separate school districts: Harris v. Yazoo

County Board of Education, Yazoo City Board of Education and

Holly Bluff Line Consolidated School District; Alexander v. Holmes

County Board of Education; Killingsworth v. The Enterprise Con

solidated School District and Quitman Consolidated School District.

Second, there are four cases wherein suit was brought by Negro

schoolchildren against six school districts and the United States

subsequently intervened: Hudson and United States v. Leake

County School Board; Blackwell and United States v. Issequena

County Board of Education and Anguilla Line Consolidated School

District; Anderson and United States v. Canton Municipal Sepa

rate School District and Madison County School District; Barn-

liardt and United States v. Meridian Separate School District.

Third, there are two eases which were filed by the United States

wherein Negro schoolchildren subsequently intervened: United

States and George Williams v. Wilkinson County Board of Educa

tion; United States and George Magee, Jr. v. North Pike County

Consolidated School District.

This petition formally embraces only school desegregation suits

involving private plaintiffs. But the disposition of this petition

will govern an additional 16 suits involving 19 school districts

against whom the United States is the sole plaintiff in companion

cases below.

4

by these plans were even less than the results held insuf

ficient in Green.3

In July, 1968, petitioners moved the district court to re

quire each respondent school board to adopt a new desegre

gation plan which “promises realistically to work, and

promises realistically to work now” (Green, supra, 391 U.S.

at 439 (1968) (emphasis Court’s)). The district court re

fused to schedule an early hearing on petitioners’ motions,

thus allowing the defective freedom of choice plans to be

employed during the 1968-69 school year. Accordingly, peti

tioners moved the Court of Appeals for summary reversal

of the district court’s refusal to grant relief for the 1968-69

school year. The Court of Appeals denied summary re-

. 3 The extent of student desegregation in the school districts at bar is shown

in the following table .-

District Percentage of Negroes

■in All-Negro Schools

Percentage of Negroes

in Predominan tly

White Schools

Anguilla

Canton

Enterprise

Holly Bluff

Holmes Count)’

Leake County

Madison County

Meridian

North Pike County

Quitman

Sharkey-Issaquena

Wilkinson County

Yazoo

Yazoo County

1968-69* 1969-70** 1968-69

(Projected)

94.4% 96.1% 5.6%

99.5% 99.9% 0.5%

84% 16%

98.9%

95.5%

97.1 % 95.7% 2.9%

99.1% 99.1% 0.9%

91.4% 84.8% 8.6%

99.2% 99.7% 0.8%

96.1%

94.6% 93.6% 5.4%

98.1% 97.3% 1.9%

91.2%

93.3%

1969-70**

(Projected)

3.9%

0 .1%

1.1%

4.5%

4.3%

0.9%

15.2%

0.3%

3.9%

6.4%

2.7%

8.8%

6.7 %

* These figures are based upon the school districts’ reports to the district

court. _

** The projections are based for the most part upon the freedom of choice

forms completed during the Spring of 1969, as compiled by the United

States and submitted to the Court of Appeals.

5

versa], but ordered the district court to

no later than November 4, 1969. Adams

F.2d 181 (5th Cir. 19GS). Upon remand,

consolidated these school desegregation

the Negro plaintiffs with those brought by

and conducted hearings cn banc during

cember, 1968.4

conduct hearings

v. Mathews, 403

the district court

cases brought by

the United States

October and De-

At the October hearings, the respondent school boards

presented lengthy testimony to the effect that achieve

ment test results justified the continued use of free choice

assignments and the concomitant token integration of white

schools and perpetuation of all-Negro schools.5 Indeed, the

cases were consolidated principally to permit the school

boards to join in this “expert” testimony. The respondent

school boards also resisted any alteration of the free choice

plans on the ground that more than token integration would

be followed by withdrawal of white children from the public

schools and the proliferation of private schools.0

4 The consolidated cases proceeded under the caption United

States v Hinds County Board of Education and Alexander v

Holmes County Board of Education. They embraced 19 districts

against whom the United States was the sole plaintiff, plus the 14

districts at bar. See note 1, supra.

6 This position was urged by Mississippi school districts and

white parent intervenors m 19G4 to retain totally segregated

schools. Voluminous expert testimony was presented'and the dis

trict court entered findings of fact supporting the proposition that

begroes were innately inferior; but the district court felt bound

by Court of Appeals rulings to deny defendants’ request that

Brown v. Board of Education be overruled. The defendants ap

pealed and the Court of Appeals ordered an end to such efforts

to justify segregation. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

tricts v. Evers; Biloxi Municipal Separate School District v Mason-

i Q C°unty Schoal Board v- Hudson, 357 F.2d G53 (5th Cir

f W w IaSl ? aSe Clted’ IIudson> is the same case before the Court m this petition.

‘ Mississippi’s first effort to retain segregated schools through

tuition grant legislation was held unconstitutional on the ground

that the legislation s purpose and effect was to perpetuate segrega-

6

Isine months after the Court of Appeals’ admonition to

the district court to treat the cases “as entitled to the high

est priority” (403 F.2d at 188), the district court, on May 13,

1969, approved freedom of choice plans for all the respon

dent school districts.7

On June 7, 1969, the United States filed alternative mo

tions for summary reversal or expedited consideration of

the cases. On June 25, 1969, the Court of Appeals entered

a letter directive expediting consideration of the cases.

See Appendix B, p. 24a, infra.

On July 3, 1969, the Court of Appeals reversed the dis

trict. court and directed it to require from the school boards

plans of desegregation other than freedom of choice. See

Appendix B, pp. 28a-37a, infra, The Court found:

(a) that not a single white child attended a Negro

school in any of the districts;

(b) that the percentage of Negro children attending

white schools ranged from zero to 16 per cent;

ticm. Coffcy v State Educational Finance Commission, 296 F

SupP- 1389 (S.D. Miss., 1969) (3-judge court).

The Mississippi legislature recently enacted a new tuition grant

program, m the nature of student loans, to enable white students

to attend private schools (House Bill No. 67). Also passed by the

House of Representatives (under consideration by the Senate) is

a lull which would grant up to $500. in credits toward Mississippi

income taxes for all payments or donations to schools, “public or

private.

7 The opinion and orders of the district court are set forth in

Appendix A. The order in Alexander v. Holmes County Board of

Education is set forth at p. 20a, infra and is representative of the

orders entered in eight of these nine cases. The ninth order en

tered in Killingsworth v. Enterprise Consolidated School District

is set forth at p. 21a, infra. It differed from the others in that it

dismissed the petitioners’ motion on the ground, later held er

roneous by the Court of Appeals, that the petitioners had not ex

plicitly authorized their attorney to file the motion.

7

(c) that token faculty integration continued in foi’ce;

and,

(d) that school activities continued substantially seg

regated.

Quoting Adams v. Mathews, supra, the Court held that “as

a matter of law, the existing plan fails to meet consti

tutional standards as established in Green” (Appendix B,

p. 32a, infra). The Court of Appeals directed that the re

spondent school boards be required to collaborate with

the United States Office of Education in formulating new

desegregation plans effective for the 1969-70 school year8

(Appendix B, pp. 35a-36a, infra). A precise timetable for

the submission and implementation of the plans was estab

lished to protect petitioners’ right to relief effective for the

1969-70 school year (Appendix B, pp. 36a-37a, infra). The

Court directed that the mandate be issued forthwith (Ap

pendix B, p. 37a, infra).9

On August 11, 1969, the deadline established for submis

sion of the new desegregation plans, the Office of Education

submitted terminal plans of desegregation for the 33 school

districts to the district court. Thirty of the 33 plans pro

vided for implemenation of pairing and/or zoning plans of

desegregation to be effective with the commencement of the

1969-70 school year.10 In his transmittal letter of August

11 (See Appendix C, pp. 40a-52a), Dr. Gregory Anrig,

Director of the Equal Educational Opportunities Division

8 This had been consistent practice following Hall v. St. Helena

Parish School Board, No. 2G450 (5th Cir., May 28, 1969).

9 On July 25, 1969, the Court of Appeals modified its order in

respects not important here (Appendix B, p. 38a, infra).

10 The exceptions were for Hinds County, Holmes County and

Meridian, in which it was asserted that problems peculiar to tlio.se

districts required postponing full implementation until the be

ginning of the 1970-71 school year.

T'Wi''

8

of tlie Office of Education—the educational expert responsi

ble f01 the final review of the plans—stated to the district

court (Appendix C, p. 44a, infra) :

I believe that each of the enclosed plans is educationally

and administratively sound, both in terms of substance

and in terms of timing. In the cases of Hinds County,

Holmes County and Meridian, the plans that we recom

mend provide for full implementation with the begin

ning of the 1970-71 school year. The principal reasons

for this delay are construction, and the numbers of

pupils and schools involved. In all other cases, the

plans that we have prepared and that we recommend

to the Court provide for complete disestablishment of

the dual school system at the beginning of the 1969-70

school year.

On August 19, 1969, the Secretary of the Department of

Health, Education and Welfare sent a letter to the Chief

Judge of the Court of Appeals and the judges of the district

court requesting that the plans submitted by the Office of

Education be withdrawn and that the 1969-70 deadline for

implemenation of plans be rescinded (Appendix C, pp. 53a-

54a, infra). The Secretary did not dispute Dr. Anrig’s view

that the plans were “educationally and administratively

sound.” Instead, the Secretary noted that he had reviewed

these plans “as the Cabinet officer of our Government

charged with the ultimate responsibility for the education

of the people of our Nation” (Appendix C, p. 52a, infra).

He continued (Appendix C, p. 54a, infra):

In this same capacity, and bearing in mind the great

trust reposed in me, together with the ultimate re

sponsibility for the education of the people of our

Nation, I am gravely concerned that the time allowed

9

for the development of these terminal plans has been

much too short for the educators of the Office of

Education to develop terminal plans which can be im

plemented this year. The administrative and logistical

difficulties which must he encountered and met in the

terribly short space of time remaining must surely in

my judgment produce chaos, confusion, and a catas

trophic educational setback to the 135,700 children,

black and white alike, who must look to the 222 schools

of these 33 Mississippi districts for their only available

educational opportunity.

Idle Secretary requested that the Office of Education and

the respondent school boards be given until December 1,

1969 to formulate new plans for desegregation, with imple

mentation of those plans to be left to an unspecified future

time (Appendix C, p. 52a, infra).

The next day, August 20, 1969, the Court of Appeals en

tered an order acknowledging receipt of (he Secretary’s

letter (Appendix C, p. 55a, infra). The next day, the De

partment of Justice filed a motion in the Court of Appeals

requesting modification of the Court’s order of July 3, 1969,

based upon the Secretary’s letter, and petitioners filed their

opposition thereto. The next day, the Court of Appeals

orally granted leave to the district court “to receive, con

sider and hear the Government’s motion for extension of

time until December 1, 1969” (see order of the Court of

Appeals of August 28, 1969, Appendix E, p. 75a, infra).

On August 25, 1969, the district court held a hearing on the

Government’s request.

At the hearing, the Government presented two witnesses

employed by the Office of Education, who testified that the

desegregation plans were educationally sound, but that im

plementation of them should be delayed due to adminis-

10

trative difficulties, generally stated, in implementing the

plans’ provisions—difficulties which the school boards had

made no attempt to solve in the fifteen years since Brown.

In opposition, petitioners presented the testimony of an

expert witness who testified that there were no sound edu

cational reasons for delay and that the reasons given by the

Government’s witnesses were generalities unrelated to a

single specific situation in any of the school districts in

volved.

The next day, the district court entered its findings of

fact and conclusions of law (see Appendix D, pp. 56a-70a,

infra), which, together with the transcript of the hearing,

were transmitted to the Court of Appeals. Two days later,

on August 28, 1969, the Court of Appeals entered an order

granting the government’s request for delay (see Appendix

10, pp. 71a-78a, infra).

On August 30, 1969, petitioners applied to Mr. Justice

Black for an order vacating the Court of Appeals’ suspen

sion of its July 3rd order. On September 5, 1969, Mr. Jus

tice Black denied the application, but stated that his

disposition did not “comport with my ideas of what ought

to be done in this case when it comes before the entire Court.

I hope these applicants will present the issue to the full

Court at the earliest possible opportunity” (Appendix F,

p. 83a, infra).

11

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

Certiorari Should Re Granted to Review and Reverse

the Court of Appeals’ Delay of Desegregation Because

the Time for Delay Has Run Out.

These cases test whether Negro schoolchildren in 14 sub

stantially segregated school districts in Mississippi a r e -

15 years after Brown v. Board of Education—at last "en

titled to have their constitutional rights vindicated now

without postponement for any reason” (Opinion in Cham

bers of Mr. Justice Black, Appendix F, p. 81a, infra).

When, 14 years ago, this Court declared (hat segregated

schools would be disestablished not immediately but only

“with all deliberate speed,” it made a unique departure from

the principle that “ [t]he basic guarantees of our Consti

tution are warrants for the here and now” (Watson v.

Memphis, 373 U.S. 526, 533 (1963)).n But it did so upon

the explicit condition that school boards establish “that such

time is necessary in the public interest and is consistent

with good faith compliance at the earliest practicable date”

(Brown II, 349 U.S. at 300). This Court could hardly have

envisioned the extent to which that narrowly circumscribed

period of grace would be exploited by local school boards

and state officials. In Mississippi, a school generation of

youngsters passed through the segregated system while

school boards showed not the slightest interest in “good

faith compliance at the earliest practicable date.”

Although Mississippi state officials initially experimented

with open defiance, see United States v. Barnett, 330 F.2d

11 “ [Pjrobably for the one and only time in American constitu

tional history, a citizen—indeed a large group of citizens—was

compelled to postpone the day of effective enjoyment of a consti-

tutional right” (Price v. Denison Independent School District

Board of Education, 348 F.2d 1010, 1013 (5th Cir. 1965).

12

369 (5tli Cir. 1963), they soon learned to rely upon less

obvious—and sometimes ingenious—devices for delay.

A pupil placement law was passed, which established a

labyrinth of administrative procedures to ensnare those

hvegro students hardy enough to attempt to desegregate

white schools. For a season that worked. The first public

school desegregation suits brought in federal court in Mis

sissippi were dismissed for failure to exhaust administra

tive remedies under the Pupil Placement Law. So it was

that while this Court, in 1964, was holding that “the time

for mere ‘deliberate speed’ has run out” (Griffin v. School

Board, 377 U.S. 218, 234 (1964), not a single child in Missis

sippi attended an integrated school.

That year, the Court of Appeals reversed the district

court’s dismissal of the first school desegregation suits.

Evers v. Jackson Municipal. Separate School District, 328

F.2d 40S (5th Cir. 1964). Upon remand, the school boards

and white intervenors delayed the trials with voluminous

testimony as to the innate inferiority of Negroes as a ra

tional basis for continued segregation. The district court,

after further delay, entered findings of fact supporting the

defendants’ theories of racial superiority, but held that it

was compelled by the Court of Appeals to require a grade-

a-year plan—thus seeking to insure that the time for “de

liberate speed” would run until 1976. That decision was

overturned in Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965) (injunction

pending appeal); 355 F.2d 865 (5tli Cir. 1966).

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 promised a new era in

school desegregation, through a “national effort, bringing

together Congress, the executive, and the judiciary [which]

' "VT

13

may be able to make meaningful the right of Negro chil

dren to equal educational opportunities.” 12

̂Under Title VI of the Act, the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare fixed minimum standards to be

used in determining the qualifications for schools applying

for federal financial aid. This administrative enforcement

by II.E.W. produced a dramatic increase in the level of

desegregation in the South. See United States Commission

on Civil Rights, Federal Enforcement of School Desegrega

tion, p. 31 (September 11, 1969). The courts accorded

‘‘great weight” to those minimum standards and estab

lished a close correlation . . . between the judiciary’s

standards in enforcing the national policy requiring de

segregation of public schools and the executive depart

ment’s standards in administering this policy” (Singleton,

supra, 348 F.2d at 731).

By 1969, the united action of the courts and the executive

in advancing toward their common objective of school

desegregation nourished hopes that the end of the deseg

regation process was in sight. To be sure, progress under

Mississippi’s freedom of choice plans continued to be

minimal. See note 3, supra. But following this Court’s

decision in Green, numerous decisions of the Court of

Appeals set the constitutional deadline for compliance at

the 1969-70 school year. See Adams v. Mathews, supra;

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

District, 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969); Henry v. Clarksdale

Municipal Separate School District, 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir.

1969); United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate

School District, 410 F.2d 626 (5th Cir. 1969). And the

executive also directed its efforts toward full compliance

States v• Jeffcrson County Board of Education, 372

f .2 d 836, 847 (5th Cir. 1966), affirmed cn banc 380 F 2d 385 (5th

Cir. 1967), cert, denied 389 U.S. 840 (1967) (Emphasis Court’s)

u

during the 1969-70 school year. As late as July 3, 1969

in a joint statement by the Attorney General and the

Secretary of the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare, the executive announced that “the ‘terminal date’

must be the 1969-70 school year.” Only a narrowly circum

scribed exception was to be permitted:

Additional time will be allowed only where those

requesting it sustain the heavy factual burden of prov

ing that compliance with the 1969-70 time schedule

cannot be achieved; where additional time is allowed,

it will be the minimum shown to be necessary.13

In this context of a united judicial and executive front

against the crumbling barriers of school desegregation

the Court of Appeals entered its orders of July 3rd and

2oth enforcing the 1969-70 “terminal date.” See Appendix

B, inf ra.

Then, on August 19, 1969, there occurred “a major re

treat m the struggle to achieve meaningful school deseg

regation” (Statement of the United States Commission

on Civil Rights, p. 2, September 11, 1969). ILE.W. essayed

an initiative for delay, based upon nothing more than a

generalized reference to “administrative and logistical

i lcultics and speculation that enforcement of the 1969-70

“terminal date” would result in “chaos [and! confusion”

(Letter of August 19, 1969 from the Secretary of the

Department of Health, Education and Welfare to the

Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals, Appendix C, p. 54a ,

infra). The delay requested called for a new deadline of

December 1, 1969 for the school districts to formulate

plans, with implementation to he accomplished at some

unspecified f uture time.

s.tatement is stei forth in Federal Enforcement of School Desegregation, supra, Appendix C. I t

25

In support of this initiative for delay, no attempt was

made to meet the ‘‘heavy factual burden” which had earlier

been demanded of school boards seeking delay. Without

particularized reference to the conditions in individual

school districts, a blanket assessment was made that more

time was needed in the 33 school districts. No effort was

made to show that the delay sought was “the minimum

shown to be necessary” for each of the districts.

The Court of Appeals’ order of August 28, 1969 accepted

H.E.W.’s new open-ended timetable. It did so without

explanation or elaboration, indicating it felt it had no

choice but to acquiesce, (see Appendix E, infra).

The Solicitor General recognized that IIEW’s action

and the Court of Appeals’ acquiescence meant that yet

another segregated school year would probably pass into

history. He characterized this as “a tragedy and a default”

(Memorandum for the United States, p. 5). But nothin-

he said, could be done.

Petitioners disagree. This initiative for delay, based

upon nothing more than undifferentiated apprehension that

further “preparation of the community” 14 is required, can

and should be corrected, for it raises a threat to school

desegregation of profound national importance, for two

reasons.

First, if the ingenuity of the federal government is to

be applied to the task of fashioning excuses for delay, it

can hardly fail to inspire local school boards to do the

same. Administrative enforcement under Title VI will be

crippled as recalcitrant school boards press for further

relaxation of enforcement and those boards that reluctantly

did comply begin to feel they acted in haste. Dissident

segregationist groups will feel good reason to redouble

u Memorandum for the United States, p. 4.

16

their pressures on school officials who kept their pledge

to the Constitution in the face of opposition.

Second, judicial enforcement will be undermined if the

federal courts are deprived of the kind of effective assist

ance upon which they had rightly come to rely. As Chief

Judge Brown observed in Price, supra, executive coopera

tion had taken the federal judge out of the role of school

administrator a role “for which he was not equipped”

(348 F.2d at 1013). In this context, then, it is perhaps not

surprising that the court below acquiesced in H.E.W.’s

request for delay, without comment or explanation. It was

in no position to analyze whether the delay requested for

each of the 33 school districts was “the minimum shown

to he necessary.” Only if it had held that there was no

longei a transition period’ during which federal courts

would continue to supervise the passage of the Southern

schools from dual to unitary systems” (Opinion in Cham

bers of Mr. Justice Black, Appendix F, p. 81a, infra), could

it have freed itself from the difficult, if not impossible, posi

tion into which it was thrust. But the court below may

have felt as did Mr. Justice Black, that this decision must

come from this Court.

In Bi own II, this Court held that school boards which

made a “prompt and reasonable start toward full com

pliance” might be granted “additional time” to solve

administrative problems (349 U.S. at 300). The problems

this Court foresaw concerned (349 U.S. at 300-01):

(1) “Physical condition of the school plant” ;

(2) “School transportation system” ;

(3) “Personnel” ; and,

(4) “Revision of school districts and attendance

areas into compact units to achieve a system

of determining admission to the public schools

on a nonracial basis.”

17

After 15 years, plans calling for the revision of school

districts and attendance areas into compact units to achieve

a unitary system were finally submitted. But the other

problems had not yet been solved by the school districts

at bar, found the district court. It found a present need

for (Appendix U, p. 65a, infra) :

(1) “Building renovations, including the adjusting

of laboratories and like facilities” ;

(2) “Bus routes [to] be redrawn” ; and,

(3) “Faculty and student preparation, including

various meetings and discussions of the prob

lems to be presented and the solutions therefor.”

Petitioners do not doubt that in some districts there re

main obstacles to the “workable, smooth desegregation

which is desired” (Ibid). But why? “There can be little

doubt where the basic fault lies in this matter. The reason

why the plans are so difficult to formulate and to implement

is largely because the local school boards involved in this

case have generally done nothing but resist; they have

continuously failed and refused to develop plans for the

effective desegregation of their schools, so as to eliminate

the long-established dual school system.” (Memorandum

for the United States, p. 4).

More delay might make for smoother desegregation. But

experience does not favor that prediction. Delays in the

past have served to embolden the recalcitrant, discourage

voluntary compliance and nourish new schemes for evasion.

Fifteen years of history teach us that every possibility for

delay, however circumscribed, will be treated as an invita

tion for ready ingenuity to exploit. Moreover, as any school

administrator will testify, there will always be adminis

trative problems in the operation of a school district. The

i« - -Mi- stJ . ,

1R

constitutional goal is not tlie smoothest possible desegrega

tion; it is the realization of personal and present rights’6

against which, at this late date, administrative convenience

amounts to nothing 1C

But petitioners see no need to indulge in speculation when

a sharper answer is called for: Ihese school districts have

had 15 years to eliminate barriers to desegregation and that

is enough. If the desegregation process is ever to be suc

cessfully concluded, this Court must act. The question is one

of constitutional rights and that is a question which under

our system can only be finally resolved by this Court. This

Court should grant review and hold, with Mr. Justice Black,

“that there is no longer the slightest excuse, reason, or

justification for further postponement of the time when

every public school system in the United States will be a

unitary one” (Opinion in Chambers of Mr. Justice Black,

Appendix P, p. 81a, infra).

16 Missouri cx rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 II.S. 337, 351-2 (1938).

10 The Court of Appeals has held in this and other cases that

interruption of the school year will be no bar to implementation of

desegregation plans. See Appendix B, p. 37a, infra; United States

v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 5tli Cir., No. 27444,

June 26, 1969.

19

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing

certiorari should he

reversed.

reasons, the petition for writ of

granted and the judgment below

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N orman C. A maker

N orman J. Chachkin

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Melvyn R. L kventhal

R euben A nderson

F red L. B anks, J r.

538V2 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

Attorneys for Petitioners

■ t

%

«■ -w; ■ i. U w j •/ >;i

.’jf-

#

i f.'.W-

T <4̂

.

1

/ !

A P P E N D I C E S

*

ii'

Hiy:

•

c

t ■*

APPENDIX A

Opinion of lhe District Court Approving

freedom of Choice Plans

[Caption omitted]

These twenty-five school cases involving thirty-three

school systems are before the Court on motions of the

plaintiffs to update the Jefferson decree in all of these

cases to comport with the requirements of Green} The

Jefferson decree is sometimes referred to as the model

decree for the establishment of a unitary school system

as such plan was designed and approved by the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit en banc.2

The right of these movants under existing circumstances

to institute and maintain this proceeding is challenged in

limine. The challenge questions the right of these plain

tiffs to institute this proceeding for supplemental relief

in these cases where no child or parent admittedly has

complained of any discriminatory treatment by the school.

In some of these cases, a final judgment was entered and

it is contended that such judgments cannot be reopened

for the purpose of enlarging and expanding the relief

granted in the original judgment. Under Civil Rule 65(d),

an injunction must be specific to be enforced. But no addi

tional relief is sought. These plaintiffs seek not to expand

or enlarge upon the relief previously granted, but simply

seek to require these schools to adopt and apply a plan

1 Charles C. Green, et al. v. County School Board of New Kent

County, Virginia, et al., 391 U.S. 430, 88 St.Ct. 1689.

2 United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education. (5

C.A.) (1966) 372 F.2d 836, affirmed on rehearing en banc 380

F.2d 385, certiorari denied.

la

2a

Opinion of the District Court Approving

Freedom of Choice Plans

which will accomplish the purpose enjoined by the model

decree. There is no merit in either of these motions for

the reason indicated; and for the further reason that the

Supreme Court of the United States has enjoined upon the

United States District Courts the duty to keep these school

cases open, and to supervise them to the end that ulti

mately the principles in Brown (and allied school cases)3

are made to effectively operate so that no child in any

public school is in any manner denied any equal protection

right by any school. Those motions of the defendants to

dismiss these motions for that reason will be denied.

The Enterprise and Quitman schools in Civil Action No.

1302(E), supra, move the Court to dismiss the motion in

that case because of the lack of authority of the attorney

to have filed it. The Court heard testimony on this question

and finds as a fact that the attorney who filed such motion

never represented the plaintiffs in that case and that he

had no express or implied power or authority to have filed

such motion here. The facts and circumstances thereasto

will be set forth in detail in the accompanying footnote.4

3 Charles C. Green, et al. v. County School Board of New Kent

County, Virginia, et al., 391 U.S. 430, 88 S.Ct. 1689; Arthur Lee

Raney, et al. v. Board of Education of Gould School District 391

U.S. 443, 88 S.Ct. 1697; Brenda. K. Monroe, et al. v. Board of

Commissioners of City of Jackson, Tennessee, 391 U S 450 88

S.Ct. 1700.

4 This matter is before the Court on motion of the defendants

to dismiss the motion of the attorney for supplemental relief. The

facts show and the Court finds: That the attorney who filed the

motion for supplemental relief was not one of the attorneys who

initially instituted the suit; that original local counsel resigned

as attorney and withdrew from the ease with approval of° the

Court; that present counsel seeking such relief graduated from

law school two or three years ago and that he does not know any

of the plaintiffs and was never requested by any plaintiff (parent

or child of this school) to seek any supplemental relief; that no

3a

Opinion of the District Court Approving

Freedom of Choice Plans

b“ ineSd!n Said CiVil Acti0n N°-

s t a t i l t i l r l l^ d o ^ o V p r f ^ f , 03568 WhCn judged by their

ment or measure up to the 9117 impressive accomplish-

in the d isesta^ lL hm ent^f^vT ^^s^ ige^of^11̂8 ®re.en

under the o!d sys,em. Most of^he sc h lls

t^\;::::snz \z iopT ? rhoois ciea,'iy iticn-

in these eases u„mis t a C y I w T h a T C

has been made ia desegregating ,hcse scJ ols, eJep U n a

y f™' » b incumbent upon the plaintiff! i,!

these eases to show a lack of substantial progress f a rf

the disestablishment of a dual school °

lishment of a unitary schoo! system o/bot'h'raees/ l t £ £

m its progress toward complying with ® by either school

model decree and the Court th is finds m l re3uirenients of the

mony and reasonable inferences de l,,Shu f!C'h nnd,sPutcd testi-

who signed the motion in this case f o r c i r 0 m 1<; fbat counsel

express or implied authority fro J L “pp/ e?™jtal relief had no

child from either school to L so ° r parent’ or

either school appeared at the hearing inr]Parent °r chiId from

any parent, or any child from e i t h l r t b T f n° rePresentative of

during the two weeks while these sehon appeared at the trial

to testify that anybody col neeted with beinS heard

authorized present counsel to seek ,!?],'either,of said schools had

the Court finds that present coimse/ ( l “Ppleme? tal relief> a»d

power or authority (express or irn n h W l^ ^ j0’!? had no snch

motion to dismiss his application for . n an,d ct lat defendants’

thorized will be granted S “ 5 « being unau-

non-resident counsel who never a n n e a l ?mtAally 3nstituted by

counsel who withdrew from the case m W ♦ Ahe,case> and local

only Reuben V. Anderson a voum- f i t ,the heannS> so that

attorney for this motion ’and sou-ht bx aWyGr’ appearod as

establish his right to do so hut »n+' 1 ̂ b?s own testimony to

or justification therefor. ’ tlrey W!thoilt factual support

'

4a

Opinion of the District Court Approving

Freedom of Choice Plans

upon devolves upon the defendants to explain or overcome

such showing by the plaintiffs. The rule is that the burden

o proof a ways rests upon the plaintiff (or movant) who

must establish proof of his claim. When the plaintiff makes

out a pnma facie case, then the burden of evidence devolves

upon the defendant to explain, or justify the facts and

circumstances surrounding his position, but the burden of

proof never shifts from the plaintiff.

There are many variable conditions which exist in these

twenty-five defendants cases that require some special and

separate consideration and treatment. In some of these

schools such as the Noxubee County School District, Civil

Action Jvo. 13t2(E), there are from three to four colored

students to each white student in these schools. A forced

mixing of those schools by a mathematical formula of in

discriminate mixing would result in the creation of all

.°F ° schools. All of these schools complain of the pro

vision m the model decree which denies the school authori

ties the right to persuade parents and children to transfer

o schools of the opposite race.6 The facts in this case show

that all of these schools have very faithfully obeyed that

injunction of the Court. No school board member or teacher

or representative of any school has tried to influence any

child or any parent to send any child to any school pre

dominantly of the opposite race. But it is the oft repeated

aw m this Circuit that the school board (and nobody else)

has the nondelegable duty to adopt a plan which will con-

Is: l■r ,

I

\

i

;

l ’

■■'frttKt «fyg, ivy***' nx**?-' •

5a

Opinion of the District Court Approving

Freedom of Choice Plans

form to all of the requirements of the model decree and

to see that such plan works. Every school official who tes

tified in every one of these cases before the Court testified

convincingly before this Court that this provision of this

model decree had interfered with a fair and just and proper

operation of the freedom of choice plan in these schools.

Yet, like Prometheus (chained to a rock) these schools are

ordered by the Court to shoulder this very positive and im

portant duty of desegregating these schools while the Court

denies them the right to counsel with and persuade parents

to let their children enter a school predominantly of the

opposite race. This Circuit has steadfastly refused to mod

ify that provision in the model decree in any manner, or

to any extent and considers such provision as an impor

tant matter of policy to be changed only by the United

States Court of Appeals for this Circuit sitting en banc.

This Court is unable to assay the degree to which such

provision in the injunction of this Court has contributed

to the failure of these schools to accomplish more impres

sive results than are revealed by the bare figure statistics

as to mixing of the races in these schools. Certainly, these

statistics cannot be ignored or disregarded and are well

calculated to have an impressive effect upon any trier of

facts in search of some means for determining whether

or not the freedom of choice plan has worked. But there is

nothing in Green, or its two companion cases, to indicate

that statistics alone are to determine whether or not a plan

works. Otherwise, a mathematical formula would have been

prescribed by the Court and sound judicial discretion of

this Court would have been discarded. But, instead, Green

said: “We do not hold that ‘freedom of choice’ can have

no place in such a plan.” * * * “Although the general ex-

6a

Opinion of the District Court Approving

Freedom of Choice Plans

perience under ‘freedom of choice’ to date has been such

as to indicate its ineffectiveness as a tool of desegregation,

there may well be instances in which it can serve as an

effective device. Where it offers real promise of aiding a

desegregation program to effectuate conversion of a state-

imposed dual system to a unitary, non-racial system there

might be no objection to allowing such a device to prove

itself in operation.” The facts and circumstances in prac

tically all of these cases (with a very few exceptions) show

this Court to its entire satisfaction that these schools, oper

ating under the freedom of choice plan, have operated in

the very best of good faith with the Court in an honest

effort to comply with and conform to all of the requirements

of the model decree. In these cases so much progress has

been made in the attitude and cooperation of the parents,

children and teachers that they are entitled to much credit

and commendation of the Court as good citizens who wish

to comply with all of the requirements of the law, and to

lay aside any inbied and ingrained former adverse opin

ions about the operation of a unitary school system.

This Court has long entertained and often expressed the

view' that the freedom of choice plan would not vmrk effec

tively, so long as mere lip service v'as paid the plan by

the school authorities, when the facts and circumstances

would disclose that actually the parent and the child in

some of these schools v'ould not in truth and in fact be a

free agent as to the school to be attended by the colored

child. But a very careful examination of the witnesses

and analysis of their testimony in these cases revealed to

the Court not one instance where any colored parent, or

colored child did not do exactly what they wanted to do

in deciding as to the school which the colored child would

7a

Opinion of the District Court Approving

Freedom of Choice Plans

attend. There are many reasons (and very important rea

sons) why colored children have not sought to attend

formerly all-white schools. The primary reason is that the

vast majority of all schools attended by colored children

qualify for the government subsidiary as “target schools.”

ihey are provided by the government with free lunches

and even improved facilities and working tools in their

shops, because the majority of the parents in such schools

are m low income brackets. A disruption of those benefits

would be disastrous to those children who would be obliged

to leave school and lose all educational advantages now

available to them there. It is such facts and circumstances

which have caused the courts to wisely observe, time and

again, that there is no easy and quick and ready-made cure

for the past ills of state enforced segregation. The problem

and its cure must yield to the facts and circumstances in

each particular school case. The cure must not result in a

destruction of the wholesome objective of the plan. I t is a

sorry and very strange principle of constitutional law

which would foster by its application a catastrophic de

struction of the right sought to be protected and enjoyed.

Well trained colored teachers in active service in for

merly colored schools and in formerly white schools in this

district have appeared before this Court and convincingly

testified under oath as a matter of fact that freedom of

choice was actually working in their schools; that perfect

harmony and understanding existed in the school and that

no danger to the school system lurked in the implementa

tion of the freedom of choice plan, but that any kind of

forced mixing of the races against the wishes of the in

volved parents and children (colored and white) would re

sult m an absolute and complete destruction of the school

1

8a

Opinion of the District Court Approving

Freedom- of Choice Plans

and its system. That is likewise a fair analysis and char

acterization of the uncontradicted testimony of experienced

expert witnesses who have spent their lives in school ser

vice in many other states. This testimony does not show

that desegregation is unpopular with some parents and

some children, but does positively show that any rushed

and random forced mixing applied for the sake of imme

diate mathematical statistics would literally destroy the

school system for both races. In many instances where the

ratio of colored people to white people is very high, the

result would be not to create just schools, but to create

predominantly colored schools, readily identifiable as such

in every instance. The same corresponding result would

° ,°7 m areas where the white population is very dense

and few Negroes live.

Surely, the policy and practice burden of these schools

is not on the parents and children to provide a unitary

school system, but is squarely upon the shoulder of these

school boards. But what can a school board member do

who is enjoined under penalty of contempt by the Jefferson

decree not to try to persuade, or dissuade any child, or

any parent as to the school which the child will attend?

That Jefferson decree has not been amended and sugges

tion as to amendment of the particular section has been

rejected. These board members have thus been deprived

of the valuable right and opportunity to properly discharge

and perform this duty so heavily resting upon them alone.

Outsiders may converse with parents and children as to

the school to be attended, where such others have no duty

or responsibility in the connection, but school board mem

bers cannot do so. The paid agitators and transients and

meddlers simply have not produced impressive results

■i

I'"'

■.... ,..**-...

f ;

I-

j

9a, _.- |

Opinion of the District Court Approving

Freedom of Choice Flans

which are statistically favorable to the school board, which

has been mandated by the Court to perform its duty, but

not allowed by the Court to discharge its responsibility in

that connection. The Court finds from such circumstances

and conditions that the mathematical statistics as to the

working progress of the freedom of choice plan for this

reason alone is unfair, unjust, unrealistic and misleading.

The plan has not failed. The Court just has not allowed it

to work.

There is nothing in Green which condemns the freedom

of choice plan as it is working in the designated schools

in this district. The Court has simply not afforded these

schools a fair and just opportunity to try to improve the

figure statistics of the plan at work. That opportunity

should not be denied or withheld.6

The Natchez schools, appearing as Civil Action No. 1120

(W), have demonstrated outstanding progress with the

freedom of choice plan. These schools accommodate approx

imately 10,400 children, 55% of whom are Negro and 45%

of whom are white. There are 40 Negro teachers in the

predominantly white schools and 53 white teachers in the

predominantly Negro schools. There are 456 Negro chil

dren in the predominantly white schools. There are 40

white and 70 Negro children in the vocational schools. A

6 One of the authors of the majority opinion in the Jefferson

school case (Judge Thornberry) speaking for a panel composed

of Judge Brown and District Judge Taylor, in United States v.

Greenwood Municipal Separate School District, (5 C.A.) 406 F.2d

1086 held: “If it develops that no children in the school district

are being denied equal protection of the laws, then no relief will

be granted. This was the position taken by the Court below and

by another district court which considered the same question.

See United States v. Junction City School District, W.D., Arkansas

1966, 253 F.Stipp. 766. We agree.” -

10a

Opinion of the District Court Approving

Freedom of Choice Flans

b T l h ° V he SCh°01 b0ard> A11 decisions of the school

board have been unanimous. It is the view of the Court

m this case that these schools have shown satisfactory and

acceptable progress under all of the facts and circumstances

n comp ying with all of the requirements of the model

eciee. n this case, as in all of these cases, the bare figure

statistics are misleading and tell only part of the story

There would appear to be no occasion or necessity for any

updating of the model decree to meet the requirements of

f Z Z ^ thiS CaSG haVG Sim^ showntha any child in this school district has been denied equal

protection of the law in any instance. The defendants in

this case have satisfied the Court that the freedom of

choice plan has worked in that system and the plaintiffs

have not shown the contrary by the greater weight of the

credible evidence (including statistics). That ends our in

quiry here, as set forth in footnote 6. The plaintiffs mo-

tron to update the decree in this particular case for the

additional reason stated in this case will be denied.

As to the other cases, the plaintiffs have not shown by

. 6 ^ ea te r weight of the more convincing evidence that the

freedom of choice plan as to the other schools has not

worked and that there is no probable prospect of such plan

working. The plan has not been afforded an opportunity

and chance to work, and it simply cannot be honestly said

that the plan has not worked. It cannot be said from the

evidence m this case that the plan will not work if given

a chance to do so. The Court, therefore, finds as a fact

and holds as a matter of law that the movants in these

cases have failed to prove that such freedom of choice plan

should be discarded as not workable, and that the schools

should be required to adopt another plan which would work

11a

W v n o n o , « . « * * * C n r t ^

Freedom of Choice Plans

~ r L T ^ i“t ' c cree-

ciaI discretion in making thaYdet “ itS sound J " *

not clearly erroneous on this record ™So f“’ *"d b surel3

troll is Committed to the son a • ,*• . sofar as such ques-

Court even though d i s l e e d ^ » '

no appellate court can pass -i l ' ^ “ appe,late court,

«on which is addressed to t l T ”* °n that Ques-

lafe court, as was said in Platt v A/ C°Urt aild not an aPPel-

ufacturing Co., 376 US HO 'ru ^ S°ta Uinin3 & Man-

“ T h e D i s t r i c t C o u r P s use\ f \ ® f L ^ * W* S b e l d "

not empower the Court of Arm l Ppropnate factor did

Tim function of the Court t,° °rder U“ transfers,

determine the a « * was to

application to the trial iud,„ „„ d”d „then 'eave their

these plaintiffs to update the re„ “ Tile »»«<>■# of

to conform with Green as to the wo'!,‘"g ‘"T ^ -th re e cases

choice plan to desegregate tho ,? "!°r “ llg of the freedom of

will be denied. The status of t h ^ ^ 7 -°f ̂ SCh°°1S

xs another-matter later to be discussed “ SCb°°ls

» S ™ ™ ^ £ " u ™ Z l i o n nCiP': w m “ d“ reed

equal protection rights accrues I o'"” v ^ 4 dcniaI of his

education in public unitary school I f ™ T affo,'ded aa

segregation in public schools ? tem- State enforced

uud harrier «,e e n ^ m en t o / t T " ^ “ “ °bsta' la

universally decreed by the courts at th™ , ri*W’ * is

vestige and influence of such state onf ' T *hat every

■oust be completely eradicated Go “ ^ Se*re«a«on

public schools, that a unitary ! ° “0. Stale s»PI>orted

the dual system of schools ^so that shali replace

operate s c h o o ls ^ t r d t t ^ X

WC-"*.

12a

1

; ‘3

apinwn of the District Court Approving

Freedom of Choice Plans

Most of the schools involved in these cases before the Court

have accepted and adopted such principles in good f a i i

ance S Z r * * • “ » ^

statistics which t Z lChcnit8s°f ^ 7 ^ But the

^ a thereto, d o ^ I S r ^ " ^

and do 7 1 , S° Stalislics al»"e a™ misleading,id do not truly and convincingly reflect the facts and cir

cams anccs as they actually exist. Surely, a schoo board

■s no responsible and is not accountable ior a con pleW,

voluntary choice of a Negro child who wishes to attend the

so 100 which IS attended predominantly bv Negroes- vet

such a choice wou.d be reflected in these statistic! as a' }£

school 1* u C 100 b0ald t0 disehare® its duty, when the

child o r t t ! 'S 7 °ined " 0t ‘° pe,'saad® or dissuade the d oi the parent m such decision. It simply may not be

onestly said under such circumstances that the freedom of

c mice p an has not worked in such a ease! The vast maior

l °f C°lored cllildren s^ p ly do not wish to attend a school

which is predominantly white, and white children simPTy

grV a idT h / ° attGnd ? SCh°01 Which is Predominantly Ne

Z ’ a7 lngramed and inbl’ed influence and character

tlC °f ** !’aces not be changed by any pseudo teachers'

or sociologists m judicial robes. If forced mixing is the

timate goal in these cases, then extreme care must be ex

eicised by more knowledgeable and more experienced men

than mere judges of trial and appellate courts to avoid a

complete disruption of our entire educational svstem in this

i-stnct. It is easy for a judge in an ivory tower, aloof and

afar from the actual working circumstances and conditions

m these schools, to rationalize and unilaterally decree the

13a

Opinion of the District Court Approving

Freedom of Choice Plans

answer to problems with which he is not familiar and with

out regard to and consideration for the completely insur

mountable barriers to the suggested course of solution.

This Court certainly does not possess any of the training,

01 skill, or experience or facilities necessary to operate any

kind of schools; and unhesitatingly admits to its utter in

competence to exercise, or exert any helpful power or au

thority in that area. These school boards are thus

confronted with many very serious and perplexing school

problems which will command the very highest skill of their

expertise in discharging and performing in accordance with

the requirements of law. The responsibility is strictly theirs

to carry out the mandate of this Court under penalty of

sanctions. If the HEW has any competent and experienced

administrative people who could completely divest them

selves of all political ambitions and influence, it is possible

that they could lie of some help to these boards in devising

and administering plans for the complete desegregation of

these schools without injury to the educational objective.

But plans heretofore have not been meaningful or helpful

in criticisms thereof before this Court, and have resulted in

nothing but a waste of time. Nobody needs any more guide

lines or plans any longer to be completely informed of the

duty of these school boards. It is unmistakably clear now

that this duty does not rest on the parent or on the child

to make these plans work, but such duty rests squarely and

alone upon the shoulders of these school board members.

I t is their duty under the injunction heretofore issued by

this Court to see that the existing freedom of choice plan

for the desegregation of these public schools works now,

or will work in the immediate future. If and when it be

comes apparent to the Court that a plan is working to the

w~’ ....

i,

i:

l

3

f

14a

Opinion of the District Court Approving

Freedom of Choice Plans

degree that no parent or child of either race can convince

the Court that some child is being denied the equal protec

tion of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Federal Constitution by the policy and operating practices

of a publicly supported school, then the plan in operation

must be said to be working and any additional relief re

quested should be denied. Those are exactly the facts and

circumstances established before this Court without any

dispute, or contradiction in the evidence in this record on

that question. The rule in this Circuit under such facts and

circumstances is that further relief should be denied. That

is the rule of this Circuit as declared in United States v.

Greenwood Municipal Separate School District, supra,

where it is said: “If it develops that no children in the

school district are being denied equal protection of the

laws, then no relief will be granted. This was the position

taken by the Court below and by another district court

which considered the same question. See United States v

Junction City School District, W.D., Arkansas, 19GG, 253

F.Supp. 766. We agree.”

Now as to the faculty. Very little progress has been made

by any of these other schools in desegregating the faculties.

That is a monumental job as the evidence in this record

shows for several reasons. Teachers are not well paid in

this district, and the schools are simply not in a position to

crack any whip over their heads. Actually, the facts show

that there is such a scarcity of available teachers in this

distiict that many of the Schools have been unable to com

plete their present faculty requirements. The evidence in

this record does not show one single instance where there

has been any discrimination on the part of any school au

thority in hiring teachers. In many of these schools, the

“v , r f "'f'

15a

Opinion of the District Court Approving

Freedom of Choice Plans

teachers are married and simply teach schools as sort of

an avocation without regard to the adequacy of the salary,

because they live in the town where the school is situated

and they are not dependent for their livelihood on such

salary. Several of these schools are obliged to compete

with the United States Government where their schools

are operated on Indian reservations financed by the Govern

ment. Such teachers are paid much more attractive salaries

than the neighboring adjoining state schools can afford to

pay from their limited budgets. These teachers who thus

contract with these school boards insist upon designating in

the contract the school at which they will teach at such re

duced salary. Now, it is very unrealistically suggested that

the school board should disregard such provision in their

contract, and should stand upon the suggestion or legal

advice (as dicta in this Circuit) that such teachers be as

signed without regard to terms of the contract, and use

such court advice as a defense, if sued upon such contract,

or breach thereof. Surely, a teacher has a vested right to

teach where he or she pleases, and the teacher owes no duty

to the contrary to anybody. It is certainly not difficult to

foresee the calamitous result which would follow the pur

suit of such a suggestion in the state court trial, and the

result which would accrue to the school. That simply is not

the answer to the problem, and no panacea is offered here,

but these schools surely do have a very positive duty to

uproot and remove every vestige of the former segregated

policies which were for so long state enforced in tins area.

This Circuit has frequently expressed its impatience, and

at times with some petulance, at the schools’ lack of prog

ress in complying with the literal requirements of the

Jefferson decree. United States v. Board of Education of

16a

Opinion of the District Court Approving

1 > eeclorn of Choice Plans

the City of Bessemer, (5 C.A.) 396 F.2d 44 imposes upon

se aool boards the positive duty to desegregate faculties,

with the sanction of discharge, if a teacher refuses an as

signment m furtherance of an order of the board. Target

dates must be set for the ultimate accomplishment of such

result of complete integration of the faculty by the school

year 1970-1971 says this Circuit. Cf: United States v.

Greenwood Municipal Separate School District 406 F 2d

1086, 3093-4. '

Montgomery County Board of Education v. Adam Carr

r., (o C.A.) 400 F.2d 1 holds: That good faith in a court of

equity in this sensitive area of desegregation is an import

ant element; that there must be target dates for the ac

complishment of faculty desegregation; that there can be

no mixing by any numerical or racial percentage ratio of

faculty which would enlarge upon the requirements of the

model decree; that there shall be no hard and fast rule as

to exact percentages, but only approximations of such ratios

that must remain flexible. [Certiorari granted and set for

argument on April 21 and April 28 calendars in United

States Supreme Court.]

In sum, and by way of recap of the finding of facts by the

Court as to all remaining schools before the Court in this

record, the Court expressly finds from the uncontradicted

undisputed credible evidence offered before it in this case

that :

(1) The freedom of choice plan in all of these cases is

universally acclaimed by both races in all schools as being

most desirable, most workable and acceptable by everybody.

Nobody testified to anything to the contrary or to anything

better. Every witness who testified on both sides testified

substantially to the same effect. There is no substantial dis-

17a

Opinion of the District Court Approving

Freedom of Choice Plans

pute or contradiction of such fact, to be found anywhere in

this record as to any school. The movants had no witnesses

of their own, but used only teachers or officials of these

schools as their witnesses.

(2) The target schools are accomplishing a very effective

and wholesome purpose and these schools should not be

disturbed or disrupted in their service under federal law

to these underprivileged children who could not otherwise

afford to attend any school.

(3) Extracurricula activities are being engaged in on a

gradual and cautious basis in this particular delicate area

winch can easily result in a destruction of the entire pro

gram for both races by any precipitous action of a court in

the exercise of its equity jurisdiction even in the very best

of good faith.

(4) No parent and no child in any school has complained

to anybody of any discriminatory treatment accorded any

child, or of any alleged failure of the freedom of choice plan

to operate effectively as to anybody in any one of these

schools before the Court; and no parent and no child in any

school before the Court appeared here to testify in support

of any one of the plaintiffs’ motions to show any necessity

oi propiiety for updating the model decree.

(a) No school in the district has attained the figure de

gree of mixing of the races among the students to equal that

condemned in Green as being unsatisfactory, but it cannot

be said as a matter of fact that the freedom of choice plan

has failed in these school sprimarily because the board (and

all teachers and officials) have been enjoined and are still

enjoined not to try to persuade any child or any parent to

mix with the opposite race so as to make such freedom of

18a

Opinion of the District Court Approving

Freedom of Choice Plans