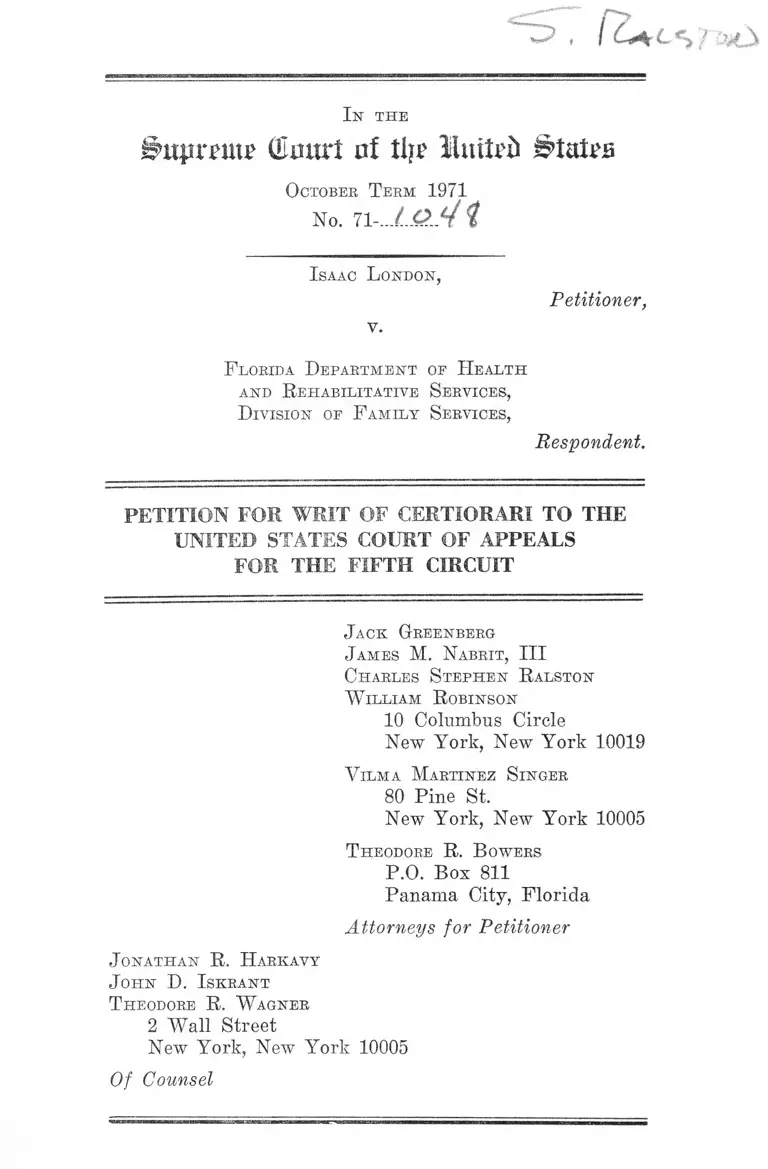

London v. Florida Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services, Division of Family Services Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. London v. Florida Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services, Division of Family Services Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1971. 56d75291-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b45a5693-4c9d-43cf-9f3a-dfa0b6b17faf/london-v-florida-department-of-health-and-rehabilitative-services-division-of-family-services-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

I

I n the

(Unurt uf tljp lluitPii States

O ctober T erm 1971

No. 71-...LQ..*/ {

I saac L ondon,

v.

Petitioner,

F lorida D epartm ent op H ealth

and R ehabilitative S ervices,

D ivision of F a m il y S ervices,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

J ack G reenberg

J ames M. N abrit , III

C harles S teph en R alston

W illiam R obinson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

V ilm a M artinez S inger

80 Pine St.

New York, New York 10005

T heodore R . B owers

P.O. Box 811

Panama City, Florida

Attorneys for Petitioner

J on ath an R. H arkavy

J ohn D . I skrant

T heodore R. W agner

2 Wall Street

New York, New York 10005

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion Below .................. 1

Jurisdiction .......................................................................... 2

Question Presented ................. 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 3

Statement ..... 3

Statement of Facts ........................... 4

A. Petitioner’s Employment History Prior to

the Transfer ........................................................ 4

B. The State’s Investigation of Complaints

Against Petitioner ............................................... 6

C. Events Following the Transfer of Petitioner 9

R easons eor Gran tin g th e "Writ—

The Decision Below Is in Conflict With This

Court’s Decision in Stromberg v. California, Since

Petitioner’s Discharge May Have Been Based on

Either an Unconstitutional or a Constitutional

Ground, and the State Failed to Show the Latter 14

Conclusion .......................................................................... 16

A ppendix—

Opinion of the Court of Appeals ......................... la

Order of the Court of Appeals Denying Petition

for Rehearing ........................................................ 7a

IX

PAGE

Memorandum Decision of the District Court ....... 8a

Final Judgment of District Court .... ........ ........... 21a

T able of Cases

Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177 (4th Cir. 1966) ..... ..14,15

Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 TJ.S. 563

(1968) .......... ..................... .......................... -...... ..2,13,14,16

16

.2,15

Street v. New York, 394 TJ.S. 576 (1969) -----

Stromberg v. California, 283 TJ.S. 359 (1931)

Wright v. Georgia, 373 TJ.S. 284 (1963) ..... 16

I n th e

0itpmtc (Enurt nt tlx? Inttzb States

O ctober T erm 1971

No. 71-...........

I saac L ondon,

v.

Petitioner,

F lorida D epartm ent of H ealth

and R ehabilitative S ervices,

D ivision of F am ily S ervices,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Opinion Relow

The decision of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit is reported at 448 F.2d 655 and is

reprinted infra pages la-6a. The memorandum decision

of the federal District Court for the Northern District

of Florida is reported at 313 F. Supp. 591 and it and

the final judgment of that court are reported infra pages

8a-21a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment and opinion of the Court of Appeals

was entered on September 15, 1971. A petition for re

hearing was timely filed and was denied on October 19,1971.

2

Mr. Justice Powell extended the time for filing the peti

tion for writ of certiorari herein to and including Feb

ruary 16, 1972 in an order dated January 11, 1972 (No.

A-708). The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pur

suant to 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Question Presented

The record demonstrates and the Court of Appeals held

that petitioner was transferred from Okaloosa County to

Escambia County in derogation of his First and Four

teenth Amendment rights. The Court of Appeals, how

ever, upheld the District Judge because “his conclusions

and findings involved credibility choices” and that listening

to the witnesses the trial court found “ sufficient emetics to

sanitize the Escambia atmosphere, that the decision to

dismiss London was based solely upon his work record,

and that this latter decision was supported by the evi

dence. We cannot demonstrate to the contrary.” Pursuant

to Rule 52a, the Court of Appeals affirmed the Trial Court.

In Escambia County, petitioner, despite nine years of ser

vice, was treated as a “ trial” employee because of his

unconstitutional transfer. He was under constant sur

veillance, his work was reviewed, and his performance

was not compared to other employees’ performance. It

cannot be known whether if he were viewed as a tenured

employee, he would have been discharged.

Since his discharge might have been based upon valid

grounds (not meeting the standard of tenured employees),

or unconstitutional grounds (not meeting the standard of

trial employees), he may have been fired in violation of

Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 IT.S. 563 (1968); or

he may not have been discharged in violation thereof.

Therefore, should not the judgment below be reversed

under Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S. 359 (1931)?

3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This matter involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States which pro

vides in pertinent part:

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall

abridge the privileges and immunities of citizens of

the United States; nor shall any State deprive any

person of life, liberty, or property, without due pro

cess of law; nor deny to any person within its juris

diction the equal protection of the laws.

This matter also involves the First Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States which provides in per

tinent part:

Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the free

dom of speech. . . .

Statement

This action was commenced in the United States Dis

trict Court for the Northern District of Florida pursuant

to 42 U.S.C. §1983, the claim being made that petitioner

was deprived of “ rights, privileges, [and] immunities

secured by the Constitution” of the United States. The

jurisdiction of the district court was invoked under 28

U.S.C. §1343(3). Petitioner alleged in his complaint that

he had been discharged from his employment as a social

worker under the jurisdiction of the predecessor of the

respondent, the Florida Department of Health and Reha

bilitative Services, Division of Family Services,1 because 1

1 The original state agency defendant was the Department of

Public Welfare of the State of Florida. During the course of the

litigation the name of that department was changed.

4

of Ms exercise of free speech and because of his race in

violation of the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the

Constitution of the United States. After a hearing the

United States District Court issued its memorandum de

cision, infra Appendix, pages 8a-20a, denying all relief

and entered a final judgment dismissing the complaint

Appendix, p. 21a. A timely appeal was taken to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

which affirmed the decision of the court below on Sep

tember 15, 1971. App. pp. la-6a. A petition for rehearing

in the Court of Appeals was denied without opinion on

October 19, 1971. App. p. 7a.2

Statement of Facts

Petitioner was employed by the State of Florida as a

social worker from June 15, 1956, until March 4, 1966.

The events at issue here involve his employment in Oka

loosa County beginning in 1956, the circumstances of his

transfer to Escambia County in August, 1965, and his

discharge from employment in March, 1966.

A. Petitioner’s Employment History

Prior to the Transfer.

When petitioner was hired in 1956, he was the first

black social worker to be employed by the state in Okaloosa

County. The record clearly indicates that petitioner was

a satisfactory employee throughout his tenure in Okaloosa

County.

In September 1960, his superiors first reprimanded peti

tioner for advocating views unpopular in the white com

2 The time for filing this petition for writ of certiorari was ex

tended by Mr. Justice Powell to and including February 16, 1972.

5

munity. A .3 57-58; Pre-trial Stipulation of Facts (here

inafter referred to as “ St.” ) No. 7. Petitioner had criticized

double sessions at one of the segregated public schools in

the area in which he lived. Petitioner spoke as a member

of the community and not as a state employee, but his

advocacy resulted in a complaint to the District Welfare

Board (hereinafter called the “Board” ) by the Superin

tendent of Schools, Mr. Bichburg. Following that com

plaint petitioner was “ counseled” by the Board that “it was

contrary to the Board’s and the Department’s policy for

social workers to become involved in controversial issues

affecting the community. . . .” 313 F. Supp. 591, 594 (App.,

infra, p. 10a). In addition to “counseling” petitioner the

Board required petitioner to sign a statement of understand

ing that the “ repetition of such incidents will not be

tolerated (we meant by this that we would not tolerate

his creating a disturbance at a public meeting or exhibit

ing negative attitudes to public officials, etc.).” A. 57-58;

St. No. 7.

Following this incident petitioner, who was regarded as a

spokesman for the Negro community due to his ability to

articulate community views, performed his work in a satis

factory manner. 313 F. Supp. at 594. A. 57; St. No. 6.

Against this background the following events precipitated

the personnel actions resulting in petitioner’s discharge.

In the Fall of 1964 Mr. Max Bruner, Superintendent of

Public Instruction in Okaloosa County, made a speech at

a PTA meeting at Escambia Farms School. A. 400. Peti

tioner was on a panel and asked questions of Mr. Bruner

who described these questions as follows: “ I remember

questions that were raised there where insinuations were

made that I had been a part of a system that had not

3 “A.” refers to the record appendix in the Court of Appeals.

6

done my duty toward adequately providing educational op

portunities for youngsters because of their race . . . .”

A. 402.

Then in the Spring of 1965 petitioner, whose two children

attended the local segregated public school, presided over

a PTA meeting in his capacity as vice-president of the

local PTA at that high school, the PTA president not being

at the meeting. At the meeting plaintiff asked some seri

ous and substantial questions of the guest speaker, Mr.

Bruner. These questions related to alleged discrim

inatory conditions in the Negro schools (apart from the

obvious fact that the schools were part of a dual school

system).4 As a result of Mr. London’s questions at these

tow PTA meetings, complaints were made against him

and the process of transferring him began. A. 59-60; St.

Nos. 15-17, 19-20.

B. The State’s Investigation of Complaints

Against Petitioner

Mr. Bruner, the man to whom plaintiff’s questions at

the 1965 PTA meeting were directed, initiated the state’s

surveillance of plaintiff’s official activities. However, in

stead of processing the complaint through the proper chan

4 The questions which “embarrassed” Superintendent Bruner

were as follows:

“ 1. Why the first and second grade students did not take their

text books home for study?

2. Why the supply of text books at Carver Hill School was

not adequate?

3. How could a Negro teacher be transferred to an all white

school ?

4. When was a Negro going to be employed in the office of

County Superintendent ?

5. Why wasn’t a secretary available to each teacher in the

school?”

A. 62; St. No. 28.

7

nels which, would have afforded plaintiff a fair defense to

the charges levied against him, Mr. Bruner complained

directly to state officials (including a representative of

the Governor’s office, Mr. James Lee, and a Florida

representative, Mr. James H. Wise) who, in the words of

the district court, “ . . . passed these complaints on to

officials of the Department, with either the suggestion or

demand that plaintiff be transferred out of Okaloosa

County.” 313 F. Supp. at 594, App., infra, p. 11a; A. 60,

St. No. 17.

[“ Sjeveral of the local county officials . . .” also com

plained about petitioner 313 F. Supp. at 594; App. infra,

p. 11a. The district court, however, while noting the ex

istence of such complaints, did not make any finding as to

the source and nature of the complaints except to note as

an aside that some of London’s superiors felt that the com

plaints “ . . . may have been the result of racial prejudice on

the part of those complaining. . . .” 313 F. Supp. at 595;

App. infra, p. 14a.

An investigation of these complaints was immediately

instituted under the direction of Mrs. Martha Horne, the

Director of Personnel of the State Department, even though

such personnel actions are usually handled by the local

Board. A. 60-61; St. Nos. 20-21. The investigation turned

up nothing more conclusive than statements of three or

four public officials in Okaloosa County that did not like

plaintiff’s attitude.5 There was no indication that peti

tioner’s work was unsatisfactory.

5 For example, it was alleged that plaintiff refused to remove

his hat while in a public building. It was later established that

plaintiff was not asked to do so nor did other men do so. In 1963

plaintiff complained about an over-assessment of real property

owned by one of plaintiff’s welfare clients. It was later found that

plaintiff’s complaint was just. Moreover, the tax assessor indicated

he had worked amicably with plaintiff in the two years after the

8

Even prior to this investigation, the state personnel

director had suggested to the local director that petitioner

be transferred, which suggestion was prompted to some

extent by political pressure (Defendant’s Ex. No. 28; A. 60,

61; St. Nos. 17, 23). And despite the failure of the inves

tigation to develop any specific detrimental information

against petitioner, the state department insisted on the

transfer.

Against this documented background of pressure from

state officials possessing both executive and legislative au

thority over the Department, the Board held a meeting in

May, 1965, where plaintiff expressed his views of the com

plaints about him. Then in June the Board met to consider

disposition of the matter. The record clearly indicates that

some members of the Board were not convinced that the

charges against plaintiff were justified, and that at least

some of the complaints against plaintiff were based on

racial prejudice.6 But because Mrs. Horne was adamant

in her belief that plaintiff had to be transferred, the Board

incident. _A. 62-64; St. 29-33. Other responses to Mrs. Horne’s

investigation indicated that the local sheriff thought plaintiff was

“arrogant” and that he might be a “civil rights worker.” A. 62;

St. No. 29. A local judge said that petitioner’s clients could get

what they wanted if they would “submit” to him. This charge was

not substantiated. A. 75-76; St. Nos. 65, 67.

6 The local director, Mrs. Beardon, sent the following letter to

the Vice Chairman of the District Welfare Board (A. 74-75; St.

No. 64) :

“Neither Mrs. Edna Adams, Colonel Bichardson nor I felt

that the charges against Mr. London were entirely justified,

although undoubtedly there is some truth involved. We be

lieve that some of the complaints from public officials were

definitely based on racial prejudice. However, how do you

prove this sort of thing?

It, was Colonel Bichardson’s thinking that with the Gover

nor’s office demanding that Mr. London be transferred and

our own State Personnel Director and State Welfare Director

making the same demands, there was little to be gained in

Mr. London’s behalf by refusing to make the transfer. Colonel

9

(composed of 17 people from Okaloosa and six other coun

ties) finally approved her recommendations for a transfer.

The Court of Appeals held that the District Court was in

error in concluding that the transfer was not tainted by

racial and free speech factors:

While we affirm the judgment below, we first wish to

make clear that we disassociate ourselves from the

reasoning of the trial judge which led him to the con

clusion that London’s transfer from Okaloosa County

was tainted with neither racial nor free speech over

tones. It is much too superficial to reason that even

though some of the complaints registered against plain

tiff were racially motivated, London’s rights were not

impaired since the Welfare Board was not so motivated.

Whatever the conscious motivations of the individual

members of the Board, its decision to transfer London

could remain discriminatory if founded upon testimony

or evidence which was tainted by racial prejudice.

448 F. 2d at 657; App. infra, p. 4a.

C. Events following the Transfer o f Petitioner

Petitioner appealed the transfer to the Florida Merit Sys

tem Council which heard his appeal August 13, 1965 and

rendered its decision upholding the transfer by order dated

Richardson felt the best strategy was to go ahead and recom

mend the transfer which would give Mr. London the oppor

tunity to appeal the matter to the Florida Merit System. I

now have a copy of the statement prepared by Mrs. Martha

Horne, State Personnel Director, which will constitute our

Department’s defense of the appeal. I do wish you could

come up here and read it. We still have no information as

to when the appeal will be heard but surely it will be some

time during July. There are so many factors involved in this

whole matter that it would take considerable time for me to

explain them to you. We are all of the opinion that much of

it involves a controversy between Mr. London and the princi

pal of the school where Mr. London’s wife is a teacher.”

10

August 27, 1965. Immediately following the decision of the

Council Mrs. Reardon received orders from her superiors

at the state level that the petitioner was to be placed “ on

trial” for six months or until March 1, 1966. A. 76; St. No.

70. On August 30, 1965, ten days before petitioner was to

begin work in Escambia, Mrs. Reardon wrote petitioner,

informing him that because of the controversy he had

generated in Okaloosa County, he was to be put “ on trial”

for six months at Escambia, despite petitioner’s nine year

tenure as an employee in the Department. A. 76; St. No. 71;

Plaintiffs Ex. No. 35. In this letter she also informed peti

tioner that if his work during that period was not entirely

satisfactory and if his relations with the community didn’t

also improve, he would be expected to resign. Petitioner

thus began work in Escambia on September 9, 1965, in a

vulnerable status generated solely by his unconstitutional

transfer.

Despite Mrs. Reardon’s plans, the District Welfare Board

concluded on September 14 that it would not be necessary

to place petitioner on trial status officially since it was

felt that he was under a duty to perform “without further

difficulties which might result in embarrassment to the

agency.” A. 78; St. Nos. 79-80; Def. Ex. 54. Despite this

lack of official action, Mrs. Reardon instructed petitioner’s

new supervisor in Escambia that he was to be treated in

the same manner as if he were on trial status. A. 78-79;

St. Nos. 82, 83, 84; Def. Ex. No. 56. The supervisor was

instructed to keep petitioner under close surveillance and

to “keep a running record of everything concerning Mr.

London’s performance.” Id.1 Thus whether petitioner was *

7 Mrs. Horne, the State Personnel Director, kept constant pres

sure on Mrs. Reardon to maintain surveillance on petitioner:

Q. Mrs. Reardon, you have testified that Mrs. Horne took

over the investigation of this case in chief and was constantly

on you about the investigation and et cetera?

A. In Okaloosa County; yes, sir.

11

on trial status officially or not, the effect was the same:

he was singled out and, unlike most other workers, his

habits and work product were scrupulously monitored. In

fact, the task of monitoring petitioner’s work was so ex

tensive the supervisor spent a good deal of her spare

time at nights scrutinizing his records, looking for errors.

A. 305-06. Petitioner was immediately informed by the

supervisor that his work was unsatisfactory. A. 78; St. No.

78.

As a result of this close monitoring of petitioner’s work,

the District Welfare Board officially placed him on trial

status for one month on November 16, 1965. A. 81; St. No.

90. The evaluation recommending this action cited poor

work production and excessive use of sick leave as factors

involved. Other reasons included playing a radio in the

office, remaining seated when visitors entered his office, and

other breaches of “courtesy.” Def. Ex. No. 63.

On December 14, the District Welfare Board noted im

provement in petitioner’s work and attendance. However,

Q. When Mr. London was transferred did Mrs. Horne con

tinue her pressure on district one?

A. We were required to report constantly on the happen

ings, the occurrences, the volume of work, the daily attendance

and non attendance, and that sort of thing.

Q. Were you required to report in detail all the activities

of Mr. London while he was there?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you file these reports with Mrs. Horne ?

A. Some were written and some were by telephone.

Q. How often did she phone you on this?

A. Frequently. Sometimes daily.

Q. Did you spend—strike that question—were you required

to spend time even off duty to prepare these reports that she

wanted to have on Mr. London?

A. I did in order to keep my daily job going. I had to do

a good bit of this work at home, on the weekends and at night,

and away from the office. . . . this affair did require an un

ending amount of time away from the office as well as in the

office.

(A. 523-524)

12

the Board felt that the previous month had not been a good

test period due to the holidays and an excessive amount of

desk rather than field work. Accordingly, petitioner’s trial

period was extended another month. A. 82; St. No. 95.

The Board did not meet in January, but on February 15,

1966, the Board requested petitioner’s resignation “ due to

your inefficiency, inability or unwillingness to perform the

duties of your position in a satisfactory manner, your

tardiness, and your excessive use of sick leave.” A. 83; St.

No. 103. Upon refusal to resign, petitioner was dismissed

in a letter dated March 3, effective March 4. A. 83; St. No.

104; Def. Ex. 126.

Petitioner immediately appealed his dismissal to the

Merit System Council. A. 84; St. No. 105. It was only after

the dismissal that Mrs. Jacks, from the State Welfare

Office, prepared an evaluation of petitioner’s case records

to justify his dismissal before the Council. She evaluated

22 of petitioner’s 155 cases. She reviewed no cases of other

workers in the unit and had no basis for objective compari

son. A. 479, 488.

It should be pointed out that at no time did petitioner

take more sick leave than he had legitimately accumulated

in accordance with Department regulations. A. 95-96; St.

No. 124. In fact, petitioner took less sick leave time than

several other social workers, none of whom were subjected

to disciplinary action. Ibid. It should also be noted that

petitioner’s work production during his service at Escam

bia was equal to and often greater than that of his fellow

workers. A. 96-98; St. No. 125.

The state Merit System Council upheld petitioner’s dis

charge, and this action followed. The district court, after

hearing the matter de novo, held against petitioner. With

regard to the transfer, the court held that it did not violate

13

petitioner’s First Amendment rights because he had no

right to government employ and the imposition of restric

tions on his free speech activities was reasonable. 313

F. Supp. at 596. With regard to the discharge of peti

tioner, the court, held that there was no proof that the

defendants had abused their discretion, that the dismissal

was not tainted by any racial prejudice that may have

existed in the first county, and that the dismissal wms based

on the petitioner’s work record. 313 F. Supp. at 596-97.

The Court of Appeals specifically held that the district

court had applied an erroneous rule of law with regard

to the transfer, noting’ the failure of the lower court to

cite Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 563 (1968).

Nevertheless, the appellate court refused to reverse, on

the ground that the trial court’s finding that the discharge

was not tainted by the constitutional violations in the first

county that led to the transfer was not clearly erroneous

within the meaning of Rule 52(a), Fed. R. Civ. Proc.,

448 F.2d 657-68.

A petition for rehearing was filed, urging that because

the district court decided the case on the basis of an

erroneous view of the law, the decision should be at least

vacated and remanded. The petition was denied, occa

sioning this petition for writ of certiorari.

14

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

The Decision Below Is in Conflict With This Court’s

Decision in Stromberg v. California, Since Petitioner’ s

Discharge May Have Been Based on Either an Uncon

stitutional or a Constitutional Ground, and the State

Failed to Show the Latter.

Petitioner was a dissident in Okaloosa County who spoke

out in defense of Fourteenth Amendment rights of Negro

school children and in order to secure a better education

for them. As such, he was a thorn in the side of politically

powerful opponents who sought to suppress him. While he

acted in a constitutional and legal manner in defense of

constitutional ends, he nevertheless was transferred from

Okaloosa County to Escambia County in violation of his

First and Fourteenth Amendment rights and the Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit so held.

Once in Escambia he was not treated as a tenured em

ployee of nine years standing, which he was, but as a trial

employee. As such he was subjected to surveillance and

comparisons never visited upon tenured employees. His

work was reviewed in isolation and not compared to the

work of others in his department as the Fourth Circuit

would have required in Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177

(4th Cir. 1966). Following this review, his work was held

to be not up to standard and he was discharged. We have

urged and the Court of Appeals found (solely as to Oka

loosa but not as to Escambia County) that in this sorry

persecution of an outspoken citizen, petitioner was exer

cising rights secured by this Court in Pickering v. Board

of Education, 391 U.S. 563 (1968).

The Fifth Circuit in agreeing with petitioner so far as

Okaloosa County was concerned, held that the trial judge

was nevertheless not clearly erroneous in coming to a con

15

trary conclusion with regard to Escambia County to which

petitioner had been transferred. The trial court believed

that there were no racial nor free speech grounds for the

firing in Escambia and the Court of Appeals held there was

enough evidence, so that this conclusion was not clearly

erroneous.

The fact is, however, that in Okaloosa petitioner was de

nied constitutional rights which led directly to his being

placed on trial status in Escambia. This was done by the

same state and local officials responsible for the unconsti

tutional transfer.* In such trial status he was subjected to

surveillance and evaluation, again by the same officials who

transferred him, which he would not have been subjected to

but for the Okaloosa experience. Moreover, his work was

not compared to the work of other employees, as the Fourth

Circuit would have required in Johnson v. Branch, supra.

Therefore, while it is possible that his work may have

been so bad in Escambia that he would have been fired no

matter who he was and whatever his background, it is also

true that but for his trial status his work would not have

been reviewed, and if reviewed he may have been compared

to others, and whether compared to others or not, his work

might have been held to be up to the standards of a tenured

employee. His discharge therefore may have been based

upon constitutional as readily as upon unconstitutional

grounds.

However, neither the District Court nor the Court of

Appeals recognized this to be the case. Therefore, they

failed to apply the rule established by this Court in Strom-

berg v. California, 283 H.S. 359 (1931); that is, when an

8 The two counties, Okaloosa and Escambia, were in the same

welfare district, with the same director, Mrs. Reardon. Mrs. Rear

don acted throughout pursuant to the orders of the state personnel

director, Mrs. Horne.

16

action may be based on two grounds, one constitutional

and one unconstitutional, it must be clear that only the

constitutional ground was used. See also, Street v. Neiv

York, 394 U.S. 576 (1969); Cf., Wright v. Georgia, 373 U.S.

284 (1963). Thus, the decisions below conflict with holdings

of this Court and present important issues relating to the

legal standards to be applied in cases raising questions

under Pickering.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the Petition for Writ of

Certiorari should be granted and the decision below re

versed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

J ames M . N abbit , III

C harles S teph en R alston

W illiam R obinson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

V ilm a M artinez S inger.

80 Pine St.

New York, New York 10005

T heodore R. B owers

P.O. Box 811

Panama City, Florida

Attorneys for Petitioner

J o nathan R . H arkavy

J ohn D . I skrant

T heodore R . W agner

2 Wall Street

New York, New York 10005

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

I n th e

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob th e F if t h C ircuit

No. 30180

Opinion of the Court of Appeals

I saac L ondon,

versus

Plaintiff-A ppellant,

F lorida D epartm ent of H ealth and R ehabilitative

S ervices, D ivision of F am ily S ervices,

Defendant-Appellee.

A PPE A L FRO M T H E U N IT E D STATES DISTRICT COURT

FROM T H E N O R T H E R N DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

(September 15, 1971)

Before W isdom , Circuit Judge, D avis,* Judge, and

G oldberg, Circuit Judge.

P er C uriam : I f we were not buckled by Fed. R. Civ. P.

52(a) and if the trial court were not shielded by that Rule’s

“clearly erroneous” fiat,* 1 we might very well reverse. While

* Honorable Oscar H. Davis, U. S. Court of Claims, sitting by

Designation.

1 See Horton v. United States Steel Corp., 5 Cir. 1961, 286 F.2d

710, 713 ( “District Court . . . fact findings ; . . come here well

armed with the buckler and shield of F.R.Civ.P. 52(a), 28 U.S.

C.A.” ).

la

2a

our diligent search through over a thousand pages of

record gives us an intimation that the trial court’s rulings

may have been wrong, our perquisition nevertheless leaves

us unconvinced that on the crucial issues the judge was

clearly erroneous. The probability of his error simply does

not reach the egregious stage required by United States v.

United States Gypsum Co., 1948, 333 U.S. 364, 395, 68 S.Ct.

525, 92 L.Ed. 746.2 Bound by that standard of review, we

affirm the judgment below.

Plaintiff, Isaac London, was employed by the State of

Florida as a social worker from June 15, 1956, until his

dismissal on March 4, 1966. All but a few months of this

employment period were spent in Okaloosa County, Florida,

where London was the only black social worker. In the

summer of 1965, plaintiff was transferred by the District

Welfare Board from Okaloosa County to Escambia County,

Florida. This transfer grew out of complaints registered

by numerous Okaloosa County public officials who felt that

plaintiff was so “belligerent,” “ antagonistic,” and “ rude”

that they could not work with him in his capacity as a social

worker. It is clear that at least a portion of these com

plaints were engendered by the activities of plaintiff on

behalf of various civil rights causes in the County.

While protesting his transfer, plaintiff reported for work

in Escambia County. After several months, and following

numerous warnings that his work was deficient, plaintiff

was permanently dismissed on March 4, 1966, “ [d]ue to . . .

[his] inefficiency, inability, or unwillingness to perform

Opinion of the Court of Appeals

2 In the Gypsum Company case the Supreme Court held that a

finding may be found clearly erroneous, within the meaning of

Rule 52(a), only when “the reviewing court on the entire evidence

is left with the definite and firm conviction that a mistake has

been committed.” 333 U.S. at 395.

3a

the duties of . . . [his] position in a satisfactory manner,

. . . [his] tardiness and excessive use of sick leave.”

Following a de novo hearing before an Appeals Council

in which his dismissal was upheld, plaintiff filed an action

in federal district court alleging that his transfer and sub

sequent dismissal were based upon racial discrimination

and political considerations in violation of his rights under

the First and Fourteenth Amendments. After lengthy pre

trial maneuverings, an essentially de novo hearing was

conducted by the trial court,3 and judgment was rendered

against the plaintiff.4

The district court first concluded that while racial prej

udice might have generated some of the complaints of

Okaloosa officials concerning London’s conduct and attitude,

the decision by the Board to transfer him was not motivated

by racial considerations. Bather, the court found that the

Board transferred plaintiff in good faith “ for his own effi

ciency and that of the Department.” 313 F. Supp. at 596.

Finding that London’s political activity and mannerisms

antagonized public officials and thereby interfered with the

proper performance of his job, the district court held that

the transfer did not violate plaintiff’ s First Amendment

rights. Secondly, the district court held that even if plain

tiff’s rights had been violated by the transfer, his subse

quent dismissal was based upon his poor work performance

in Escambia and was in no way tainted by the events occur

ring in Okaloosa. Since this termination did not violate

Opinion of the Court of Appeals

3 With regard to the proper procedure to be followed by a dis

trict court in reviewing a dismissal of a state employee, compare

Ferguson v. Thomas, 5 Cir. 1970, 430 F.2d 852, 858-59, with Fluker

v. Alabama State Bd. of Educ., 5 Cir. 1971, 441 F.2d 201, 208 &

n.15.

4 The district court’s opinion is reported at 313 F.Supp. 591.

4a

plaintiff’s constitutional rights, the court accordingly held

that London could not now demand that he he given re

instatement or hack pay.

While we affirm the judgment below, we first wish to make

clear that we disassociate ourselves from the reasoning of

the trial judge which led him to the conclusion that Lon

don’s transfer from Okaloosa County was tainted with

neither racial nor free speech overtones. It is much too

superficial to reason that even though some of the com

plaints registered against plaintiff were racially motivated,

London’s rights were not impaired since the Welfare Board

was not so motivated. Whatever the conscious motivations

of the individual members of the Board, its decision to

transfer London could remain discriminatory if founded

upon testimony or evidence which was tainted by racial

prejudice. Moreover, we cannot agree with the reasoning

of the district which seems to hold that since government

employment is a mere privilege granted by the state, public

employees are of a lesser breed when it comes to the pro

tection of their First Amendment rights. In Pickering v.

Board of Educ., 1968, 391 U.S. 563, 88 S. Ct. 1731, 20

L.Ed.2d 811, a case not cited by the court below, the Su

preme Court completely put to rest such outgrown shib

boleths to which even Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, not

a jurisprudential dovecote, once ascribed.5 Precursive as

he generally was, Justice Holmes simply did not anticipate

the First Amendment’s coalescent embrace of all citizens.

5 Justice Holmes saw a dichotomous absolutism in applying First

Amendment rights to government employees and private citizens,

as revealed in the following epigram while speaking for the Massa

chusetts Supreme Judicial Court:

“ The petitioner may have a constitutional right to talk politics,

but he has no constitutional right to be a policeman.” Mc-

Auliffe v. New Bedford, Mass., 1892, 29 N.E. 517.

Opinion of the Court of Appeals

5a

The district court was also in error in disregarding this

embrace. See generally Hobbs v. Thompson, 5 Cir. 1971,

—— F .2d------ [No. 30704, ] ; Fred v. Board of Public

Instruction, 5 Cirj 1969, 415 F.2d 851; Van Alstyne, The

Demise of the Bight-Privilege Distinction in Constitutional

Law, 81 Harv. L. Rev. 1439 (1968).

Having said this much, we nevertheless conclude that the

district court’s finding that no taint from Okaloosa carried

over to the dismissal proceedings in Escambia is not clearly

erroneous.6 I f we had been sitting as the trial court, we

would have been reminded that a page of history is more

significant than a volume of logic. But as an appellate

court, we cannot necessarily decree in the historian’s role.

It seems to us, perhaps because of a lack of naivety in these

matters, that the inequities visited upon London in Oka

loosa could not have been purged while he worked for a

few months in the neighboring county of Escambia. But

the trial judge, who is also sophisticated in these matters,

concluded otherwise; and his conclusions and findings in

volved credibility choices. Listening to the witnesses, he

found that there were sufficient emitics to sanitize the

Escambia atmosphere, that the decision to dismiss London

was based solely upon his work record, and that this latter

decision was supported by the evidence. We cannot demon

strate clearly to the contrary. See Fluker v. Alabama State

Bd. of Educ., supra; United States v. LeFlore County, 5

6 Since we affirm the district court’s conclusion that London’s

Escambia discharge was untainted, we must also affirm the court’s

denial of plaintiff’s requested relief—reinstatement and back pay.

Even though the Okaloosa transfer may have been unjustified,

plaintiff cannot be reinstated since his ultimate discharge from an

employment position he chose to accept is upheld. Nor is back pay

warranted, for the Okaloosa transfer, even if improper, did not

reduce or affect London’s salary.

Opinion of the Court of Appeals

6a

Opinion of the Court of Appeals

Cir. 1967, 371 F.2d 368; Chaney v. City of Galveston, 5 Cir.

1966, 368 F.2d 774. Therefore, in obedience and obeisance

to the mandate of Rule 52(a), we affirm the trial court’s

judgment.

A ffirm ed .

7a

Order of the Court of Appeals Denying

Petition for Rehearing

October 19, 1971

To A ll P arties L isted B elow

R e : No. 30180—London v. Fla. Dept, of Health

and Rehabilitative Serv., etc.

Gentlemen:

Yon are hereby advised that the Court has today entered

an order denying the Petition ( ) for Rehearing in the

above case. No opinion was rendered in connection there

with. See Rule 41, Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure

for issuance and stay of the mandate.

Very truly yours,

E dward W . W adsworth ,

Clerk

By / s / F rances W olff

Deputy Clerk

Memorandum Decision of the District Court

[dated May 12, 1970]

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

P ensacola D ivision

PCA 1764

I saac L ondon ,

vs.

Plaintiff,

F lorida D epartm ent oe H ealth and R ehabilitative

S ervices, D ivision oe F a m il y S ervices,

Defendant.

M em orandum D ecision

Involved here is a complaint of Plaintiff, I saac L ondon,

attacking his transfer and subsequent dismissal as a case

worker with the Department of Health and Rehabilitative

Services of the State of Florida. The case has been tried

before the Court without a jury. All evidence has been

taken, arguments of counsel for the respective parties

heard, and briefs filed by the parties considered.

Plaintiff brings suit under 42 U.S.C. Sections 1981 and

1983, alleging civil rights and First and Fourteenth Amend

ment violations. Initially, Plaintiff also sought to bring the

action as a class suit, but during the progress of the litiga

tion, that attempt of Plaintiff’s was abandoned and was

withdrawn, with no evidence proffered to justify such re

lief, and so such need not be considered by the Court.

9a

Plaintiff was employed by the Department as a case

worker from June 15, 1956, to March 4, 1966.

Under Florida law, determination respecting transfer or

dismissal of a case worker such as Plaintiff is made initially

by the District Welfare Board. A case worker dissatisfied

with this determination may appeal to the State Merit

System Council which, under the law, gives him, in effect,

a trial de novo, making its own findings and determination.

(Names o f these respective state agencies have, since this

suit commenced, been changed; the reference here is to the

names as they existed at the time of the events in question

and as they were referred to in arguments and briefs before

the Court. For brevity, the District Welfare Board is

referred to as Board, the State Merit System as Council,

and the overall State Welfare Department as Department.)

In the summer of 1965, Plaintiff was transferred, against

his desire, from. Okaloosa County, Florida, to Escambia

County, Florida, by the Board. Being dissatisfied, he ap

pealed to the Council, and it approved and directed the

transfer. Thereafter, he commenced working as a case

worker in Escambia County. He was, on March 4, 1966,

permanently dismissed as a case worker, by the Board.

Again, he took an appeal to the Council, and his dismissal

was sustained, with it also finding he should be dismissed,

and he was dismissed. Following that, this suit in this

'Court was brought.

Plaintiff charges that both his transfer and dismissal

were motivated by racial prejudice, that they were in viola

tion of his First Amendment right of freedom of speech,

association and assembly, and that the actions of the Board

and the Council in transferring and later dismissing him

were arbitrary, capricious and unreasonable.

Memorandum Decision of the District Court

10a

In addition, Plaintiff contends that, on his dismissal or

der, he was, by the Council, denied the right of discovery,

with such denial being a denial of the right adequately

to prepare a defense, in violation of the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

With reference to Plaintiff’s contentions of transfer be

cause of racial prejudice and in violation of First Amend

ment rights, the record shows he was the first Negro social

worker employed by the Defendant in Okaloosa County,

Florida. In September, 1960, he became the center of

controversy for the first time. From the record, he became

involved in a school affair involving double sessions at one

of the elementary schools that was then attended solely by

Negro children. His activities resulted in a complaint to

the Board from the County Superintendent of Public In

struction, and it conducted an investigation. As a result of

the incidents and the investigation that followed, Plaintiff

was counseled by his supervisors and advised by them that

it was contrary to the Board’s and the Department’s policy

for social workers to become involved in controversial is

sues affecting the community and that might impair the

effectiveness with which a social worker performed his

duties. Plaintiff signed a statement of understanding at

that time, that “ repetition of such incidents will not be

tolerated (we mean by this that we would not tolerate his

creating a disturbance at a public meeting or exhibit a

negative attitude toward public officials, and so forth . . . ” ,

and no other action was taken by the Board. From the rec

ord, it appears any controversy resulting from this inci

dent soon died down. Except for this minor incident, the

Department’s evaluation of his work from 1956 through

1964 indicates satisfactory performance by him, with his

working satisfactorily with fellow employees and county

officials with whom his work brought him in contact.

Memorandum Decision of the District Court

11a

In the spring of 1965, however, several of the local county

officials lodged complaint about Plaintiff with Mr. Lee, a

representative of the Governor’s office and a member of

the state legislature. Mr, Lee, in turn, passed these com

plaints on to officials of the Department, with either the

suggestion or demand that Plaintiff be transferred out of

Okaloosa County. An investigation of these complaints im

mediately resulted through the offices of Mrs. Reardon,

Director of the Board, and Mrs. Horne, State Personnel

Director.

Various Okaloosa County officials were interviewed con

cerning their objections to Mr. London. Each of them re

sponded to the inquiry, and each, in effect, advised he felt

the Plaintiff was belligerent, antagonistic and rude, and

that his attitude made it difficult for them to work with

him. Each of them also stated under oath that their opinion

regarding him was not motivated by racial prejudice. One

of them so interviewed was, himself, the Negro principal

of a high school; at least two of them who are white, in

evidence and testimony before this Court, indicated or

stated they have Negroes working in their offices, at least

at the present time.

Mrs. Horne interviewed Plaintiff personally in her office

in Jacksonville, and reached the personal conclusion that

if Plaintiff acted, in Okaloosa County, as he acted before

her, he would, indeed, be obnoxious to the local officials.

She particularly objected to what she felt was his attitude

that he could do no wrong, and that any criticism of him

was motivated by race or politics. On the basis of her

inquiries and interviews, she concluded Plaintiff’s effective

ness in Okaloosa County as a case worker was impaired,

that Escambia County was a larger county, and that he

might be able to work effectively in a new and larger county.

Memorandum Decision of the District Court

12 a

Additional investigation of the complaints concerning

Mr. London was conducted through Mrs. Reardon’s office.

Involved in this investigation were Mrs. Reardon, Mr.

Mahan (Plaintiff’s supervisor), and Miss Stokes, Okaloosa

County Supervisor of the employees of the Board. An

informal meeting was held in the latter part of May, 1965,

to permit Plaintiff an opportunity to give his view of the

controversy. Present at such meeting were Mrs. Reardon,

Mr. Mahan, Col. Richardson (the Board Chairman), one

member of the personnel committee, and the Plaintiff. Com

plete transcript of this meeting was not made, but a sum

mary of the meeting was preserved and is in the record

before the Court. Following that informal meeting, the

Board met, on June 15, 1965, to consider disposition of the

matter. The record indicates that while at least one or

more of the members of the Board, at that meeting, were

not completely convinced the charges against Plaintiff were

justified, Mrs. Horne was adamant in her belief he had

to be transferred in order to preserve the continued effec

tiveness of the Department’s work in Okaloosa County. It

also indicates the Board, by a fifteen-to-two vote, approved

Mrs. Horne’s recommendation that Plaintiff be transferred.

There is evidence in the record that one or more of those

involved, from the Board’s standpoint, felt that complaints

of county officials may have been based on racial prejudice,

but that proof was lacking* that such complaints were, in

fact, based on racial prejudice.

'Col. Richardson, Chairman of the Board at the time of

this incident, testified at the hearing before this Court, and

discussed circumstances surrounding the transfer. Appar

ently, he believed that the county officials were not com

pletely justified in their complaints against Plaintiff, but

Memorandum Decision of the District Court

13a

he also felt that Plaintiff had lost his effectiveness as a

social worker in Okaloosa County because of the feeling of

the people regarding him. He went so far as to say he

felt that the basis for transferring him might have been

not only to insure his future effectiveness as a case worker

in the Department, but for his personal protection. He

denied, however, that he was ever under any political pres

sure to transfer London.

On the appeal to the Council from the transfer, its opin

ion, rendered on August 22, 1965, contained the finding that

“Mr. London’s personal effectiveness as a social worker in

Okaloosa County has been materially impaired to the de

gree that his ability to carry out the primary duties and

responsibilities of a social worker in Okaloosa County has

been greatly diminished.”

The testimony and evidence before the Court fails to

establish by its greater weight, or preponderance, that

Plaintiff’s transfer resulted from racial prejudice. That

there may have been overtones of racial prejudice in the

complaints against him does not, of course, establish on

the part of those transferring him motivation of racial

prejudice, and no such motivation here appears. It seems

clear from the record that those of the Board, Department

and Council involved in his transfer were motivated solely

and simply by consideration of effectiveness and concern

for the effectiveness and efficiency of the Department’s

operations, and nothing else.

This Court recognizes the difficulty inherent in attempt

ing to prove subjective elements of racial prejudice or

motivation, but this Court finds no basis, in the evidence

and testimony before it, that the officials involved in the

transfer were so motivated. To the contrary, it seems clear

that some of them, at least, were concerned that the com

Memorandum Decision of the District Court

14a

plaints of Plaintiff’s effectiveness may have been the result

of racial prejudice on the part of those complaining, and

that, because they were concerned, they reached, almost

reluctantly, the conclusion that, for the efficiency and effec

tiveness of the system, as well as his own effectiveness, he

must be transferred. And the record does establish that

his actions engendered, properly or improperly, the com

plaints against him.

This Court finds and concludes that on the record before

it, Plaintiff has not carried the burden of proving the

Board, in transferring Plaintiff was motivated by racial

prejudice, and that such transfer was in violation of his

civil rights. In fact, and as evidence to the contrary, the

record indicates a Negro case worker was by the Board

hired to replace Plaintiff when he was transferred.

Let this decision be not misunderstood. There is distinct

impression, from the evidence, that both the county officials

making complaints and Plaintiff may have borne their race

like chips upon their shoulders. Such, if true, is less under

standable in public officials elected to serve and represent

all of the people of their county than it is in a public em

ployee the first of his race to be employed in his capacity

in his county. But it is to be condoned in neither. Because

of this Court’s holding the Board, Council and their em

ployees acted without regard for race, this Court need not,

and does not, give that facet of this case further considera

tion.

Plaintiff also charges transfer in violation of his First

Amendment rights of freedom of speech, assembly and

association. It is uncontradicted the complaints concern

ing Plaintiff arose both because of his manner and his

speech while engaged in activities unrelated to his work.

This Court finds and holds that, even though Plaintiff’s

Memorandum Decision of the District Court

15a

transfer resulted, in large part, from complaints respecting

such, his transfer did not violate his First Amendment

rights. Jensen v. Olson, 353 F.2d 825 (8 Cir. 1965), held that

“ The First Amendment guarantees free speech and assem

bly, but it does not guarantee Government employ. * * *

There is no basic right to Government employ, any more

than there is to employment by any other particular em

ployer.” Accord, Adler v. Board of Education of The City of

New York, 342 U.'S. 485 (1952). Plaintiff, as an employee,

had the duty to comply with the reasonable requirements

and regulations established by the Department. One of these

requirements was that employees not engage in community

controversies that might disrupt the effective perfor

mance of their duty. Such requirement is reasonable. Here,

from the record, the Board in good faith believed that

London’s conduct had adversely affected his effectiveness,

and impaired the work of the Board. Again, as stated in

Jenson v. Olson, supra, “When his speech is disruptive of

the proper functioning of the public’s business the privilege

of governmental employment may be withdrawn without it

being said that he was denied his freedom of speech.”

The record here presents a picture of public officials

concerned about activities of one of their employees and

complaints against him and in good faith concluding, for

his own efficiency and that of the Department, he must be

transferred. That they, or some of them, were concerned

about the possibility1 of racial overtones in the complaints

against him bolsters rather than detracts from the conclu

sion of good faith by them.

Memorandum Decision of the District Court

1 That possibility was present in connection with his Okaloosa

employment; on the record, complaints regarding his work in

Escambia County resulted in no wise from racial prejudice.

16a

Presented also is the picture of a public employee who

pursues, as he has the right to pursue, his constitutional

rights of freedom of speech, assembly, and association; but

does so without regard to its effect on his public employ

ment. He has no right of public employment; where, as

here, his exercise of his rights reduces and impairs his

effectiveness and that of his public employer, he is subject

to good faith transfer or dismissal.

Here, neither the Board nor the Council, on the appeal,

dismissed the Plaintiff from employment. Instead, they

transferred him, believing that he might be able to work

effectively and efficiently in another county. There is simply

no basis here for holding this transfer to be in violation of

his First Amendment rights.

Plaintiff also contends the transfer by the Board and the

Council was arbitrary, capricious and unreasonable. On

this aspect of the case, a court may not substitute its

judgment for that of the Board, or the Council. It is not

the Court’s function to review the wisdom or good judg

ment of these state officials in the exercise of their discre

tion in matters of employee transfer or removal. Johnson

v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177 (4 Cir. 1966). On the record before

the Court, it is concluded, and the Court finds, the action

of these state officials in accomplishing Plaintiff’s transfer

was based on substantial and sufficient evidence, and may

not be held to be arbitrary, capricious or unreasonable.

Moreover, even assuming, arguendo, his transfer was in

violation of his First and Fourteenth Amendment rights,

it would not follow he could now obtain the relief he seeks.

He did not have to accept the transfer; he could then have

refused it, and brought court action concerning it. Instead,

he chose, finally, to accept the transfer and to undertake

Memorandum Decision of the District Court

17a

the performance of Ms duties as case worker in Escambia

County. Having done so, he was required to perform prop

erly his employment in Escambia County. If he was prop

erly dismissed from that employment because of inefficiency

or other valid reasons, he may not now demand or be given

reinstatement and back pay on any charge that his initial

transfer violated any constitutional rights he may have had.

Going now to his employment in Escambia County fol

lowing his transfer, the record shows he was permanently

dismissed on March 4, 1966, by action taken by the Board

at its meeting on February 15, 1966. The reasons for such

dismissal were stated as follows: “Due to your inefficiency,

inability, or unwillingess to perform the duties of your

position in a satisfactory manner, your tardiness and ex

cessive use of sick leave . . . ”

Plaintiff appealed the dismissal to the Council and a trial

de novo on the issue of his dismissal was held. The Coun

cil, by order dated June 24, 1966, sustained the decision of

the Board in dismissing Plaintiff from his position.

The state officials here involved must be given wide dis

cretion in exercising their judgment in the dismissal of

employees, but the exercise of such power cannot be done

in an arbitrary and unreasonable manner, nor in such a

way as to infringe on the First Amendment rights of free

dom of expression and association, nor in a racially dis

criminatory manner. Johnson v. Branch, supra. I f none of

this is shown before this Court, the discretion vested in

the state officials regarding the dismissal should not be

disturbed by this Court; it cannot and should not substitute

its judgment for theirs. Johnson v. Branch, supra. The

transcript of the proceedings held before the Council May

27 and 28, 1966, and the written opinion and order of the

Memorandum Decision of the District Court

18a

Council relative to that hearing are before this Court, as

is the testimony and evidence taken at the trial before this

court. From the record, this court concludes and finds that

the findings of the Merit System Council were not arbi

trary or unreasonable and were based on substantial evi

dence sufficient to support its conclusions. [In addition,

this Court holds and finds there was not sufficient evidence

presented before the Council or before this Court to sub

stantiate Plaintiff’s allegation that he was dismissed be

cause of racial prejudice or in violation of his freedoms

of expression or association.2]

There remains one final contention of Plaintiff—that the

Council denied him a subpoena duces tecum requiring the

production of certain documents. In Plaintiff’s post-trial

brief this contention is not pursued, but it was presented in

the pleadings and was the subject of testimony at the trial.

The record is not entirely clear. As best this Court can

determine, Plaintiff, before employing an attorney, made

a request that certain documents be “ subpoenaed” . His

request was entirely overbroad. Presumably recognizing

this, his counsel thereafter by letter made a narrower re

quest, stating that he wished to “ subpoena” Plaintiff’s case

load at Unit 6, Pensacola, Florida, and at Unit 14, Crest-

view, Florida.

It also was overbroad—at the hearing the Council was

concerned only with the quality of Plaintiff’s work after he

2 There were no racial overtones in the charges before the Coun

cil at the dismissal hearing. Plaintiff, apparently recognizing such,

took the position racial prejudice from his Okaloosa County em

ployment followed him to Escambia County and, in effect, tainted

the dismissal charges. But the evidence fell far short of establish

ing such. The Council made its position clear—it was deciding the

dismissal charges on the quality and character of Plaintiff’s work

in Escambia County alone, and without any regard to his prior

employment in Okaloosa County.

Memorandum Decision of the District Court

19a

was transferred to Escambia County. Before it, at the hear

ing then were the files on only twenty-two of the Escambia

County cases on which Plaintiff had worked.

Counsel for Plaintiff testified before this Court Plaintiff

wanted the case load to review before hearing, with his

request denied because they were privileged. He did not

place before the Court any other evidence of denial, or

reason for denial. According to the sworn complaint, signed

by him and Plaintiff, the application of Plaintiff was not

denied on that ground. It is not clear, however, on the

record, whether the allegation in the sworn complaint refers

to the application by Plaintiff or the later application by

counsel. Moreover, Florida’s Administrative Act (Ch. 120,

Florida Statues) contains agency authority for subpoenaes

and discovery—had Plaintiff wanted them before trial, it

would appear effort should have been made through an

attempt by way of pre-trial subpoena duces tecum and

deposition.

Be that as it may, the request for the entire Escambia

County case load was overbroad and, respecting those por

tions of it not brought before the Council, may have been

privileged.

At the hearing, Plaintiff did complain he had not been

given opportunity to review the files being then con

sidered by the Council, but at no time did he ask for

recess, continuance, or adjournment to afford him oppor

tunity to review. To the contrary, he testified fully re

garding the files discussed before the Council—at one

time he stated “I know these records backwards and for

ward, these are mine.” The transcript of the hearing-

before the Council also indicates five files Plaintiff had

specifically requested were included in the twenty-two

brought to the hearing.

Memorandum Decision of the District Court

At the trial before this Court, Plaintiff’s testimony re

specting these files was taken after he had been given

opportunity to review them. Comparison of his testi

mony before this Court and before the Council reveals

striking similarity.

The record before this Court falls far short of estab

lishing that, before the Council, Plaintiff was deprived

of opportunity to test, explain or refute the testimony

before the Council, or that he was not given a full and

fair hearing. No due process or equal protection viola

tion is shown, and this contention of Plaintiff fails.

This decision incorporates both findings of fact and

conclusions of law. On the record before the Court, Plain

tiff has not carried his burden, and he must be denied

the requested relief, with this cause being dismissed at

Plaintiff’s cost. Judgment to that effect will be entered.

Dated this 12th day of May, 1970.

s / W inston E. A know

Winston E. Arnow

Chief Judge

Memorandum Decision of the District Court

21a

Final Judgment of District Court

[dated May 12, 1970]

F in a l J udgment

Pursuant to and in accordance with memorandum de

cision of this Court filed this day, it is

O rdered and adjudged :

1. Judgment should be and is hereby entered in favor

of Defendants and against Plaintiff.

2. The relief requested by Plaintiff is denied, and this

cause is hereby dismissed at Plaintiff’s cost.

D one and ordered this 12th day of May, 1970.

s / 'W in ston E. A rnow

Winston E. Arnow

Chief Judge

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. «€§►> 219