Detroit Housing Commission v. Lewis Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Detroit Housing Commission v. Lewis Brief for Appellees, 1954. 4b2e50b4-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b4656011-29b3-4f67-94a9-d41213931f73/detroit-housing-commission-v-lewis-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

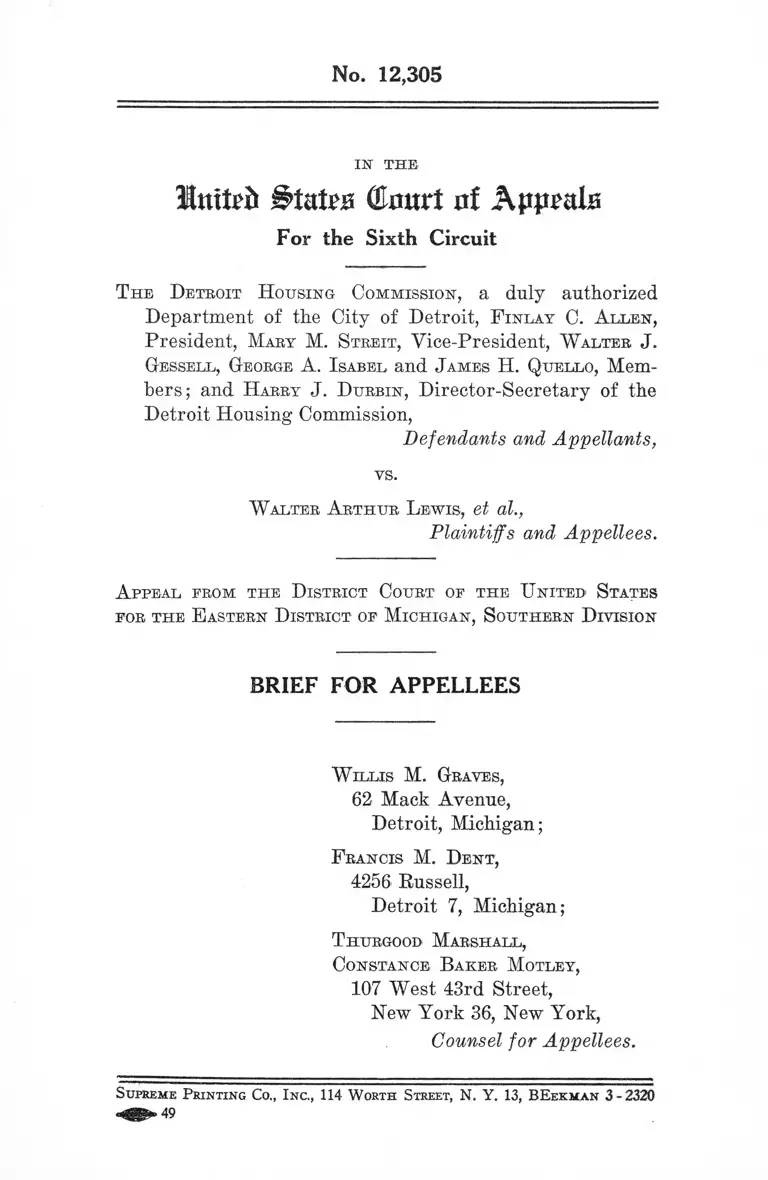

No. 12,305

IN THE

Inited ^ ta te ( to r t rtf Appeals

For the Sixth Circuit

T he Detroit H ousing Commission, a duly authorized

Department of the City of Detroit, F inlay C. A llen,

President, Mary M. Stkeit, Vice-President, W alter J.

Gessell, George A. I sabel and J ames H. Quello, Mem

bers; and Harry J, Durbin, Director-Secretary of the

Detroit Housing Commission,

Defendants and Appellants,

vs.

W alter A rthur L ewis, et al.,

Plaintiffs and Appellees.

A ppeal prom the D istrict Court of the U niter States

for the E astern D istrict of Michigan, Southern D ivision

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

W illis M. Graves,

62 Mack Avenue,

Detroit, Michigan;

F rancis M. Dent,

4256 Bussell,

Detroit 7, Michigan;

T hurgood Marshall,

Constance Baker Motley,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York 36, New York,

Counsel for Appellees.

Supreme Printing Co., Inc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BEekman 3 - 2320

< ^*> 49

Counter Statement of Questions Involved

I. I)o the policy and practices of the Detroit Housing

Commission in leasing units in public housing violate

rights secured to the plaintiffs and members of their class

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States and Title 42, United States Code, Section

1982 (formerly Title 8, United States Code, Section 42) ?

District court answered Yes.

Appellees contend answer should be Yes.

II. Does the final judgment and permanent injunction

order of the district court require defendants to integrate

forthwith every public housing unit?

District court did not answer this question directly

because not raised by appellants below, but the

record shows that district court’s answer would

be No.

Appellees contend answer should be No.

III. Is the action of the United States Supreme Court

in the School Segregation Cases applicable to the instant

case?

District court answered No.

Appellees contend answer should be No.

ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Statement of Questions Involved................................. 1

Statement of F a cts ........................................................... 1

Argument ........................................................ 2

I. Do the policy and practices of the Detroit Hous

ing Commission in leasing units in public hous

ing violate rights secured to the plaintiffs and

members of their class by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States and Title 42, United States Code, Sec

tion 1982, (formerly Title 8, United States

Code, Section 42) .............................................. 2

II. Does the final judgment and permanent injunc

tion order of the district court require defend

ants to integrate forthwith every public hous

ing unit ................................................................ 8

III. Is the action of the United States Supreme

Court in the School Segregation Cases ap

plicable to the instant ca se .................................. 11

Conclusion....................... ................................................. 18

Table of Cases

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 (1953) ..................... 3

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917) ..................... 3, 6

City of Birmingham v. Monk, 185 2d 859 (1951) cert.

den., 341 U. S. 940 (1951) ........................................... 3

City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704 (1930) . . . . 3

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668 (1927)................... . 3

Jones v. City of Hamtramck, 121 F. Supp. 123 (1954) . . 3

IV

PAGE

San Francisco Housing Authority v. Banks, San Fran

cisco Superior Court No. 420534 (Oct. 1, 1942), 120

A. C. A. 1 (1953), 41 A. C. Minutes 2 (1953) cert,

den.------U. S .-------98 L. ed.------ - (1954) ................. 4

Seawell v. McWhithey, 2 N. J. Super. 255, 63 Atl. 2d

542 (1949) rev. on other grds. 2 N. J. 563, 67 Atl. 2d

309 (1949) ....................................................... ............ 4

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 IT. S. 1 (1948).......................... 3, 7

Taylor v. Leonard, No. C1836-52 Superior Court of

N. J., Union County, Chancery Division (1954) . . 4

Vann v. Toledo Metropolitan Housing Authority, 113

F. Supp. 210 (1953) ..................................................... 3; 6

Woodbridge v. Housing Authority of Evansville No.

618 U. S. D. C., S. D. Ind. (Findings of Fact and Con

clusions of Law filed July 6, 1953) ......................... 3

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) ................. 6

Statutes Involved

Title 42, United States Code, Section 1982 (formerly

Title 8, United States Code, Section 42) ............. 2, 3, 4, 7

“ All citizens of the United States shall have the

same right, in every State and Territory, as is en

joyed by White citizens thereof to inherit, purchase,

lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal prop

erty” (R. S. § 1978).

IN THE

Mnxttb States Cimrt of Appeals

For the Sixth Circuit

No. 12,305

T he Detroit H ousing Commission, a duly authorized

Department of the City of Detroit, F inlay C. A llen,

President, Mary M. Streit, Vice-President, W alter J.

Gessell, George A. Isabel and J ames H. Quello, Mem

bers; and Harry J. D urbin, Director-Secretary of the

Detroit Housing Commission,

Defendants and Appellants,

vs.

W alter A rthur L ewis, et al.,

Plaintiffs and Appellees.

A ppeal from the D istrict Court of the United States

for the E astern D istrict of Michigan, Southern D ivision

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

Counter Statement of Facts

The facts on which the appellees rely are those stipu

lated and agreed to by the parties in this cause and appear

ing on pages 52a to 59a of Appendix to Appellants’ Brief.

2

ARGUMENT

I. Do the policy and practices o f the Detroit Hous

ing Commission In leasing units in public housing

violate rights secured to the plaintiffs and members

of their class by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution o f the United States and Title 42, United

States Code, § 1982.1

District Court answered Yes.

Appellees contend answer should be Yes.

A. Facts stipulated and agreed to by the parties which

support lower court’s conclusion that “ the regulation,

policy, custom, usage, conduct and practice of the defend

ants in refusing to lease to plaintiffs, and other eligible

Negro applicants similarly situated, certain units of public

housing under their administration, control and manage

ment, in accordance with a strict policy of racial segrega

tion, is a violation of the Constitution and laws of the

United States particularly the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States and Title 8, Sections

41 and 42 of the United States Code” (A. 95a) are as fol

lows :

“ 29. The defendants presently maintain and

enforce a policy in public housing which operates

as follows:

(1) Certain projects were designated prior to

their erection for white occupancy or for Negro

occupancy.

(2) No eligible Negro family is admitted to a

vacancy in a project presently limited to white occu

pancy and no white family is admitted to a vacancy

in a project presently limited to Negro occupancy”

(A. 57a).

1 Formerly Title 8, United States Code, Section 42.

3

List of authorities supporting lower court’s preceding

conclusion:

Buchanan v. Worley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917);

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668 (1927);

City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704 (1930);

City of Birmingham v. Monk, 185 F. 2d 859 (1951)

cert. den. 341 U. S. 940 (1951).

In the preceding cases the legislative arm of the state

was prohibited from imposing racial restrictions on the

right to occupy real property—the holding in these cases

being that such restrictions violated rights secured by the

due process and equal protection clauses of the 14th Amend

ment to the Federal Constitution and Title 8, United States

Code, Section 42 (Title 42, United States Code, Sectiorc

1982).

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948);

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 (1953).

In the preceding cases the judicial arm of the state was

prohibited from giving effect to privately imposed racial

restrictions on the right to occupy real property—the hold

ing being that judicial intervention in such cases was barred

by the prohibitions of the 14th Amendment to the Federal

Constitution and Title 8, United States Code, Section 42

(Title 42, United States Code, Section 1982).

Vann v. Toledo Metropolitan Housing Authority,

113 F. Supp. 310 (1953);

Woodbridge v. Housing Authority of Evansville,

No. 618 U. S. D. C. S. D. Ind. (Findings of Fact

and Conclusions of Law filed July 6, 1953);

Jones v. City of Hamtramck, 121 F. Supp. 123

(1954).

4

San Francisco Housing Authority v. Banks, San

Francisco Superior Court No. 420534 (Oct. 1,

1952), 120 A. C. A. 1 (1953), 41 A. C. Minutes 2

(1953) cert. den. ------U. S .------- 98 L. ed. -------

(1954) ;

Seawell v. McWhitley, 2 N. J. Super. 255, 63 Atl.

2d 542 (1949) rev. on other grds. 2 N. J. 563, 67

Atl. 2d 309 (1949);

Taylor v. Leonard, No. cl836-52 Superior Court

of N. J., Union County, Chancery Division

(1954).

In the preceding cases the administrative arm of the

state, i.e. local public housing authorities, was enjoined

from imposing racial restrictions on the right to occupy

certain public housing units—the holding being that such

restrictions, resulting from the enforcement of a policy of

racial segregation in public housing, violated rights secured

plaintiffs by the due process and equal protection clauses

of the 14th Amendment and Title 8, United States Code,

Section 42 (Title 42, United States Code, Section 1982).

B. Facts stipulated and agreed to by the parties which

support the lower court’s conclusion that “ the resolution

of the Detroit Housing Commission adopted September 26,

1952, has not in fact ended the discrimination against the

plaintiffs and the members of their class, and that such dis

crimination on the basis of race and color in housing facili

ties under the auspices of public funds, local or federal, is

in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States and Title 8, Sections 41 and 42 of

the United States Code” (A. 952) are as follows:

“ 24. As of May 31, 1950, just before the orig

inal complaint in this action was filed, the eligible

pool of certified applicants for public housing was:

White families 1,838

Negro families 4,942

5

“ As of April 1954 or as of the present, the eligible

pool of certified applicants for public housing is :

White families 383

Negro families 7,709” (A. 56a)

“ 25. Since the original complaint in this action

was filed vacancies have occurred in public housing

projects limited to white occupancy and vacancies

have occurred in public housing projects limited to

Negro occupancy as follows:

White projects 4,417

Negro projects 865” (A. 56a)

“ 26. Based on the last official report, April-May

1954, of the Detroit Housing Commission, there are

the following vacancies:

White propects 51

Negro projects 3” (A. 56a)

“ 29. The defendants presently maintain and en

force a policy in public housing projects which oper

ates as follows:

# * #

(3) The application blanks which must be filled

out by prospective tenants request information con

cerning the applicant’s race and request the appli

cant to indicate whether he or she desires to live

either in the ‘ east’ o r ‘west’.

(4) Separate lists of eligible Negro and white

families are maintained” (A. 57a)

“ 34. White families with a lesser preferential

status than some of the plaintiffs, and some of the

members of the class on behalf of which plaintiffs

sue, have been admitted to public housing units to

which, but for race, some of the plaintiffs and some

of the members of their class would have been ad

mitted” (A. 59a)

6

List of authorities supporting lower court’s preceding

conclusion:

Vann v. Toledo Metropolitan Housing Authority,

supra;

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886).

In the latter case the city ordinance, as is the resolution

of September 26, 1952, was fair on its face, but it was ad

ministered in such a way as to discriminate against Chinese.

In the instant case, the stipulated facts cited above show

that the resolution is administered by the Detroit Housing

Commission and the other defendants in such a way as to

discriminate against qualified Negro applicants.

C. Facts stipulated and agreed to by the parties which

support the conclusion of the lower court that “ in public

housing the doctrine of ‘ separate but equal’ has no place,

separate housing facilities are inherently unequal. There

fore, this .court holds that the plaintiffs and others similarly

situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by

reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the

equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment” are the same as those cited above in support

of the lower court’s second conclusion set out under sub

division B above.

List of authorities in support of lower court’s preced

ing conclusion:

Buchanan v. Warley, supra.

In the Buchanan case the United States Supreme Court

said at page 81:

“ As we have seen, this court has held laws valid

which separated the races on the basis of equal

accommodations in public conveyances, and courts of

high authority have held enactments lawful which

i

7

provide for separation in the public schools of white

. and colored pupils where equal privileges are given.

But, in view of the rights secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution, such legis

lation must have its limitations, and cannot be sus

tained where the exercise of authority exceeds the

restraints of the Constitution.”

Shelley v. Kraemer, supra.

In the Shelley case the United States Supreme Court

said at page 22:

“ The rights created by the first section of the

Fourteenth Amendment are, by its terms, guaran

teed to the individual. The rights established are

personal rights. It is, therefore, no answer to these

petitioners to say that the courts may also be induced

to deny white persons rights of ownership and occu

pancy on grounds of race or color. Equal protection

of the laws is not achieved through indiscriminate

imposition of inequalities.”

The conclusions of the lower court, that the policy and

practices of the Detroit Housing Commission and the other

defendants violate rights secured to the plaintiffs and the

members of their class by the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Federal Constitution and Title 8 U. S. C. Section 42,

being supported by the facts in this case and by the authori

ties, such be affirmed by this court.

8

II. Does the final judgment and permanent injunc

tion order of the district court require defendants to

integrate forthwith every public housing unit.

District Court did not answer this question directly

because not raised by appellants below, but

record shows district court’s answer would be

No.

Appellees contend answer should be No.

A . Terms of the Order

The injunction order provides as follows:

# * *

“ Now, therefore, it is ordered that the defend

ants and each of them, their agents, employees, rep

resentatives and successors be, and they hereby are,

forever enjoined from:

1. Denying the plaintiffs, and members of the

class which the plaintiffs represent, the right to lease

any unit in any public housing project solely because

of the race and color of the plaintiffs and members

of the class which plaintiffs represent.

2. Maintaining separate lists of eligible Negro

and white applicants for public housing.

3. Maintaining racially segregated public hous

ing projects.”

* # *

There is no provision of this final judgment and per

manent injunction order which requires defendants to in

tegrate every public housing unit forthwith. In other

words, the order, by its own terms, does not provide for the

integrating of every unit of public housing forthwith. The

defendants have, therefore, appealed to this court urging

as a ground for such appeal a provision of the final judg

ment order which does not in fact exist.

9

Defendants in their brief do not urge a reversal of the

decision of the court below on the ground that its ultimate

conclusion of law that segregation in public housing is un

constitutional is erroneous. The defendants in this appeal

claim that since their present policy and practice with

respect to assignment of eligible families to low rent pub

lic housing units is in accordance with the constitutional

mandate, the lower court should have allowed defendants

time within which to integrate or should have awaited the

decision of the United States Supreme Court in the School

Segregation Cases presently pending before it.

If the order by its terms had provided that the defend

ants integrate forthwith every unit of public housing, it

may be that defendants would need time within which to

devise orderly procedures to meet the terms of such an

order. But since, by the terms of the order, there is no

provision for the immediate integration of every public

housing unit, then clearly the need for time within which

to devise orderly procedures to effect immediate integra

tion does not exist.

B. The Effect of the Order

The effect of the district court’s order is not to compel

defendants to integrate forthwith every public housing

unit.

The effect of the first provision of the order is to enjoin

defendants from denying the plaintiffs and members of

their class the right to lease any unit in any public housing

project solely because of the race and color of the plaintiffs

and their class. The effect of this is simply to make avail

able to the next eligible applicant on the list the next avail

able unit in any of the public housing projects in the City

of Detroit. It does not require the defendants to move any

white families from their present units. It does not require,

defendants to move any Negro families from their present

10

units in order to effect integration. It simply requires that

if the plaintiffs, and members of their class, are otherwise

eligible that vacancies in white projects not be denied them

solely because they are Negroes..

The second provision of the order enjoins the defend

ants from maintaining separate lists of eligible Negro and

white applicants for public housing. This provision of the

order does not have the effect of requiring the defendants

to move white families from units in which they presently

reside, neither does it require defendants to move Negro

families from units in which they presently reside. It

simply requires defendants to maintain one list and that is

a list of applicants eligible for public housing, rather than

two lists—one of eligible white applicants and one of eli

gible Negro applicants.

The maintenance of separate lists is obviously the

method by which racial discrimination is effected with

respect to the selection of applicants for the next available

unit in a racially restricted public housing project.

The effect of the third provision of the order is to

enjoin defendants from continuing to restrict certain

projects as public housing projects available for occupancy

by eligible white families only or available for occupancy

by eligible Negro families only. The effect of this provi

sion is not to require the defendants to move white families

presently residing in public housing units or to move Negro

families presently residing in public housing units. The

effect of this provision is simply to make available to

eligible Negro families vacancies which occur in projects

presently limited to white occupancy and to make available

to eligible white families vacancies which may occur in

projects presently limited to Negro occupancy.

The Fourteenth Amendment does not permit the de

fendants to operate some of their public housing projects

11

on a racially integrated basis and some of their public-

housing projects on a racially segregated basis. The Four

teenth Amendment does not permit the defendants to make

available to the plaintiffs and members of their class units

in public housing built in the future, but deny to plaintiffs

and members of their class vacancies which occur in public

housing projects built in the past.

There were, as of the time of entry of the final judg

ment and permanent injunction order, 51 vacancies in

white projects and 3 vacancies in Negro projects. The 51

vacancies existing in projects limited to white occupancy

were denied plaintiffs and members of their class solely

because of race and color. The effect of the third provision

of the injunction order is to make these 51 vacancies in

white projects available to plaintiffs and members of their

class.

III. Is the action of the United States Supreme

Court in the School Segregation Cases applicable to the

instant case.

District Court answered No.

Appellees contend answer should be No.

The defendants in their brief, page 11, urged that this

court modify the final judgment and permanent injunction

order of the district court so that it be determined that

the policy and practices of the defendants are not in viola

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment, and that defendants

have such additional time within wdiich to complete integra

tion as appears necessary, with due regard for the public

safety and welfare. In support of this latter request on

the part of defendants, defendants urge upon this court

that the United States Supreme Court in the School Segre

gation Cases presently pending before it has not yet issued

final decrees determining how its ruling, that school segre

gation is unconstitutional, shall be enforced.

12

A. Reasons for Postponement of Decrees in

School Cases

The United States Supreme Court postponed final

orders in the School Segregation Cases for the following

reasons:

(1) Its decision in those cases is of wide applicability,

i.e., its decision affects mandatory segregation statutes in

17 southern states and the District of Columbia.

(2) There are a great variety of local conditions in

those 17 southern states and the District of Columbia which

must be taken into consideration in formulating decrees.

(3) Formulation of decrees in those cases presents

“ problems of considerable complexity.”

(4) Upon the reargument of those cases in December

1953 “ * * * the consideration of appropriate relief was

necessarily subordinate to the primary question—the con

stitutionality of segregation in public education.” The

court, therefore, did not get the assistance of counsel in

those cases with respect to formulating its decrees.

For the foregoing reasons, the United States Supreme

Court postponed the formulation of final decrees in the

School Segregation Cases.

B. Reasons for Postponement Non-Existent Here

In the instant case, the district court was not faced with

a decision of wide applicability. There is no state, includ

ing Michigan, as far as counsel for the appellees have been

able to determine, in which there are compulsory segrega

tion laws with respect to public housing. The district court

was not faced with the problem of declaring a statute of

statewide applicability in Michigan, and in many other

states, unconstitutional. It was dealing with the admin

istrative policy and practices of a single administrative

agency which affect a single community.

13

C. Simplicity of the Instant Case Drawn by Analogy

Because the decision was not of wide applicability and

need not comprehend a great variety of local conditions,

the formulation of a decree in the instant case by the dis

trict court did not present problems of considerable com

plexity. As the district court saw it—the problem of the

instant case was analogous to the problem of colored people

and white people going up to a ticket window to buy a

ticket for a train—the train having only so many seats.

The defendants say, in effect, to the colored people: You

stand in the background until all the seats available on

that particular train have been sold to white people (A.

78a). Or, in other words, as the lower court said (A. 79a)

with respect to a municipal activity which actually exists

in the City of Detroit: If they, meaning the defendants or

the City of Detroit, have two lines lining up for buses on

the street corner, the effect of the segregation policy is to

say—let the people standing in the white line get on the

bus first. The bus becomes filled with white people and

then drives away leaving the colored people standing there.

The stipulation of facts shows that since this suit was

filed in June 1950, 4,417 vacancies occurred in white proj

ects and only 865 occurred in Negro projects. This means

that white low income families eligible for public housing

had approximately 3,600 more opportunities to get housing

than the Negro families. As a result of this the number of

Negro families eligible for public housing increased from

4,942 in May 1950 to 7,709 in April 1954. Whereas, the

number of white families decreased from 1,838 in May

1950 to 383 in April 1954. From these facts and by refer

ence to the preceding analogies, the court concluded that

the Negroes were simply treated unequally “ because they

are not given their regular turn in getting into these proj

ects” (A. 79a).

Therefore, the problem before the district court was

not a complex one at all. As the district court saw it the

14

problem before it could be resolved by simply giving tbe

Negro applicants their regular turn in getting into these

projects. The court’s conclusion was:

“ The Court: I think that they are entitled to

have their applications processed and either ap

proved or disapproved strictly in the order of their

application” (A. 81a).

It is, therefore, clear that the district court had no inten

tion of requiring the defendants to integrate forthwith

every public housing unit, which as defendants suggest

would require moving white and Negro families around to

create some sought of checkerboard pattern. The district

court simply said: Treat Negroes the same as whites are

treated and when the Negro’s turn comes give to the Negro

applicant the next available unit, if he is the next in line

(A. 81a).

The situation in the instant case is, therefore, unlike

the complex problem of school desegregation in the cases

presently pending before the United States Supreme Court.

D. Time A lready A llow ed

The district court took into consideration the fact that

there might be some resistence in the City of Detroit on

the part of some of the people to the admission of Negroes

to previously all white projects. In view of this, the dis

trict court permitted four years to elapse between the filing

of the suit and the entry of its final order. The court said,

at page 65 of the Appendix to Appellants’ Brief:

“ Now, with reference to the long period of time this

case has been pending, I appreciate some of the things

that Mr. Ingalls mentioned. I never anticipated it

to be such a serious problem in Detroit. I am in

clined to think that 'counsel for the defendants are

under-estimating the progress that we have made in

15

Detroit in good race relationship in recent years.

Now, going along a little bit further with the matter,

shortly after one of the preliminary hearings in this

matter, the defendants rescinded the resolution that

I have referred to heretofore; shortly thereafter

they opened a bi-racial occupancy in one of the newer

developments. Just viewing it from the highway,

as I do every day, it looks like a pretty good develop

ment. No trouble (12) has come out of that.

In private housing, colored people have been per

mitted to move into territories that, as our general

residential standards go in this community, are rela

tively high, and no difficulties have arisen there.

I appreciate that adopting the Declaration of In

dependence did not immediately erase all of the preju

dice and bigotry that seems to be one of the crosses

that the American people have to bear.

I agree that we should proceed cautiously. I had

hoped from the beginning that my home city would

eliminate segregation, not because some court

ordered the officials to do so, but because they wanted

to do it because it was the right thing to do. And, of

course, I know that all of us would have been happy

if they had accomplished this result without com

pulsion by the Federal Government.

I think, however, there comes a time when patience

ceases to be a virtue. I think that we have reached

that place right now, so we are going ahead with this

case.”

The district court, therefore, considered the necessity

for time in which to bring about a change in the racial poli

cies of the defendants and in fact allowed them 4 years in

which to do so. As the district court pointed out and as

counsel for defendants agreed, the district court had made

it clear from the very first day in which counsel for plain

16

tiffs and defendants appeared in the district court, that

the district court was of the opinion that the law was with

the plaintiffs and against the defendants. The record shows

(A. 82a) the following discussion between the lower court

and counsel for defendants:

“ The Court: I can understand Mr. Ingall’s posi

tion. I guess I told you where I stood in this case

about four years ago.

‘ ‘ Mr. Ingalls: I beg your pardon ?

‘ ‘ The Court: I think you found out where I stood

in this case about four years ago.

“ Mr. Ingalls: I found that out the first day we

were in here, your honor.

“ The Court: So that did not come as a shock

today.

Mr. Ingalls: No.”

In Buchanan v. Warley, supra, justification for the city

ordinance requiring residential racial segregation was

sought on several grounds. One ground was that the state

had the power to pass such an ordinance in the exercise of

the police power “ to promote the public peace by prevent

ing racial conflict” .

In response to this argument the Court said, at pages

74-75:

“ The authority of the state to pass laws in the

exercise of the police power, having for their object

the promotion of the public health, safety, and wel

fare, is very broad, as has been affirmed in numerous

and recent decisions of this 'court. * * * But it is

equally well established that the police power, broad

as it is, cannot justify the passage of a law or ordi

nance which runs counter to the limitations of the

Federal Constitution; # * #

17

“ True it is that dominion over property spring

ing from ownership is not absolute and unqualified.

The disposition and use of property may be con

trolled, in the exercise of the public health, con

venience, or welfare. * * * Many illustrations might

be given from the decisions of this court and other

courts, of this principle, but these cases do not touch

the one at bar.

“ The concrete question here is: May the occu

pancy, and, necessarily, the purchase and sale of

property of which occupancy is an incident, be in

hibited by the states, or by one of its municipalities,

solely because of the color of the proposed occupant

of the premises?”

* * #

“ That there exists a serious difficult problem

arising from a feeling of race hostility which the law

is powerless to control, and to which it must give a

measure of 'consideration, may be freely admitted.

But the solution cannot be promoted by depriving

citizens of their constitutional rights” (at pp. 80-81).

The district court continually urged counsel for the de

fendants to voluntarily change the racial segregation policy

and gave them 4 years in which to do so. When it became

clear to the district court that the defendants were not pro

ceeding in good faith, it was then, and only then, that the

district court issued its injunction.

18

CONCLUSON

It is respectfully submitted by counsel for appellees

that the district court’s final judgment and permanent

injunction order be affirmed.

W il l is M. G raves ,

62 Mack Avenue,

Detroit, Michigan;

F rancis M. Dent,

4256 Russell,

Detroit 7, Michigan;

T hurgood Marshall,

Constance Baker Motley,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York 36, New York,

Counsel for Appellees.