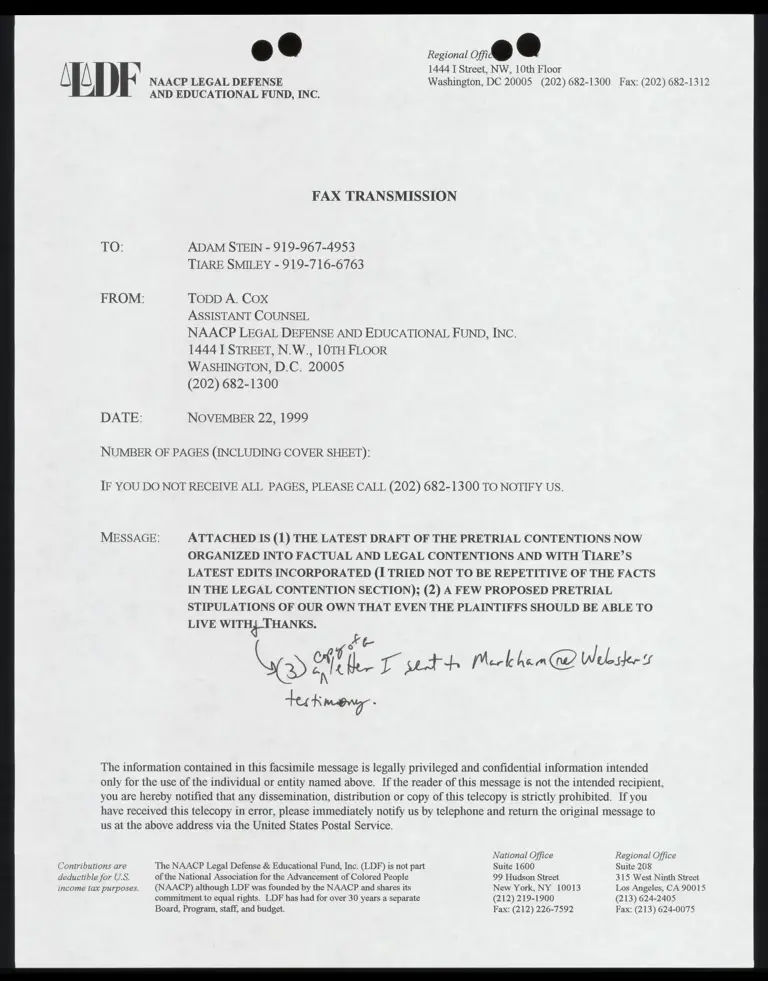

Fax to Stein and Smiley RE: Draft of pretrial contentions; proposed pretrial stipulations and letter to Markham re: Webster’s testimony

Correspondence

November 22, 1999

18 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Fax to Stein and Smiley RE: Draft of pretrial contentions; proposed pretrial stipulations and letter to Markham re: Webster’s testimony, 1999. f7855f05-e00e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b46c675b-6c2a-470a-bbed-fe4d0de7f853/fax-to-stein-and-smiley-re-draft-of-pretrial-contentions-proposed-pretrial-stipulations-and-letter-to-markham-re-webster-s-testimony. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

® a Regional 0 ®

A A 1444 1 Street, NW, 10th Floor

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE Washington, DC 20005 (202) 682-1300 Fax: (202) 682-1312

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

FAX TRANSMISSION

ADAM STEIN - 919-967-4953

TIARE SMILEY - 919-716-6763

ToDD A. COX

ASSISTANT COUNSEL

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

1444 1 STREET, N.W., 10TH FLOOR

WASHINGTON, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

DATE: NOVEMBER 22, 1999

NUMBER OF PAGES (INCLUDING COVER SHEET):

IF YOU DO NOT RECEIVE ALL PAGES, PLEASE CALL (202) 682-1300 TO NOTIFY US.

MESSAGE: ~~ ATTACHED IS (1) THE LATEST DRAFT OF THE PRETRIAL CONTENTIONS NOW

ORGANIZED INTO FACTUAL AND LEGAL CONTENTIONS AND WITH TIARE’S

LATEST EDITS INCORPORATED (I TRIED NOT TO BE REPETITIVE OF THE FACTS

IN THE LEGAL CONTENTION SECTION); (2) A FEW PROPOSED PRETRIAL

STIPULATIONS OF OUR OWN THAT EVEN THE PLAINTIFFS SHOULD BE ABLE TO

LIVE WITH{ THANKS.

&t

_ Af. 7 sed Merb heme) Welder «

The information contained in this facsimile message is legally privileged and confidential information intended

only for the use of the individual or entity named above. If the reader of this message is not the intended recipient,

you are hereby notified that any dissemination, distribution or copy of this telecopy is strictly prohibited. If you

have received this telecopy in error, please immediately notify us by telephone and return the original message to

us at the above address via the United States Postal Service.

National Office Regional Office

Contributions are The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) is not part Suite 1600 Suite 208

deductible for U.S. of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People 99 Hudson Street 315 West Ninth Street

income tax purposes. (NAACP) although LDF was founded by the NAACP and shares its New York, NY 10013 Los Angeles, CA 90015

commitment to equal rights. LDF has had for over 30 years a separate (212) 219-1900 (213) 624-2405

Board, Program, staff, and budget. Fax: (212) 226-7592 Fax: (213) 624-0075

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

Civil Action No. 4:96-CV-104

MARTIN CROMARTIE, ef al.

Plaintiffs,

Vv.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR, et al., PRE-TRIAL ORDER

Defendants,

and

ALFRED SMALLWOOD, et al.

Defendant-Intervenors.

N

a

r

N

w

N

u

N

w

N

a

N

u

N

a

N

o

N

w

N

a

N

a

N

a

N

a

N

a

N

a

N

a

Defendant and Defendant-Intervenors Factual Contentions

L Defendant and Defendant-intervenors contend that Plaintiff James Ronald Linville

resides in Congressional District 5 of the 1997 Plan.

2. Defendant and Defendant-intervenors contend that race was not the predominant

factor in the creation of Congressional District 1 or Congressional District 12 of the 1997

Reapportionment Plan and that the General Assembly did not subordinate traditional

redistricting criteria to racial considerations in creating Congressional District 1 or

Congressional District 12 of the 1997 Plan.

3. Defendant and Defendant-intervenors contend that the North Carolina General

Assembly had two primary redistricting goals in 1997. The first was to remedy

constitutional defects found by the Supreme Court in the 1992 Plan, including the

predominance of racial considerations underlying the shape and location of District 12.

The General Assembly accomplished this goal by utilizing a variety of different

redistricting techniques, including: 1) avoiding any division of precincts and of counties to

the extent possible; 2) avoiding use of narrow corridors to connect concentrations of

minority voters; 3) striving for geographical compactness without use of artificial devices

such as double cross-overs or point contiguity; 4) pursuing functional compactness by

grouping together citizens with similar interests and needs; and 5) seeking to create

districts that provide easy communication among voters and their representatives. The

second, but equally important, goal was to preserve the even (six Republican and six

Democratic members) partisan balance in North Carolina’s then-existing congressional

delegation. With the State House of Representatives controlled by Republicans and the

State Senate controlled by Democrats, preserving the same partisan balance in the

congressional delegation was essential to ensure that the General Assembly would be able

to agree on a remedial plan. The General Assembly felt, as a matter of policy, that the

legislature, rather than the federal district court, had a constitutional duty to perform the

necessary balancing of various interests to devise a new redistricting plan.

4. Defendants and Defendant-intervenors contend that the General Assembly

succeeded in reaching its stated redistricting goals.

While the 1992 Plan divided 80 precincts and 44 counties, the 1997 Plan

only divides two precincts and 22 counties.

b. District 1 in the 1992 Plan divided 25 precincts while District 1 in the 1997

Plan does not divide any precincts. District 1 joins citizens together in the mostly

rural, economically depressed counties in the northern and central Coastal Plain.

C. District 12 in the 1997 Plan is significantly more compact geographically

than it was in the 1992 Plan. The new District 12 contains parts of six counties,

rather than ten, and it does not have any areas of only “point contiguity” and does

not contain any “cross-overs” or “double-cross-overs” as it did in the 1992 Plan.

In the 1992 plan, District 12°s boundaries divided 48 precincts, while District 12 in

the 1997 Plan divides only one. The boundaries of the new District 12 were

determined by partisan considerations and a desire to have an essentially urban,

Democratic district in the Piedmont region. District 12’s African-American total

population was reduced from the original 56.63 percent in the 1992 Plan to 46.67

percent and the voting-age population was reduced from the original 53.34 percent

in the 1992 plan to 43.36 percent.

d. Defendant and Defendant-intervenors contend that Districts 1 and 12 each

encompass a distinct community of interest. District 1 is a distinctly rural district

whose residents are largely poor. The economy of the region in which the district

is located is depressed and relies heavily on agriculture and logging and districts

residents are employed largely in agricultural businesses. The concerns of the

residents of District 1 are those of a rural population, including, unemployment and

economic development in an environment in which limited job opportunities are

available. However, District 12 is a largely urban district and the residents share

common economic interests in areas, including manufacturing, research, banking

and higher education. The residents are largely employed in blue collar, suburban,

and urban employment, rather than in agricultural businesses. The interests of the

residents of District 12 are those of a largely urban populous, including mass

transportation, urban crime problems, unemployment, and housing and economic

development concerns.

5 Defendants and Defendant-intervenors contend that the configuration of District

12 reflects a strong correlation between the racial composition of the precincts and party

preference and the General Assembly’s goal of creating a partisan Democratic District 12.

6. Defendant and Defendant-intervenors contend that during the 1997 redistricting,

the North Carolina General Assembly was concerned that, when creating District 1 in the

1997 Plan, the Civil Rights Division might deny Section 5 preclearance if the General

Assembly failed to create a majority-minority district in the general area comprising

District 1. Prior to negotiating the 1997 Plan, the State House and State Senate each

independently proposed plans which included a geographically compact majority African-

American district in the northeastern and central Coastal Plan. Further, it was important

to the General Assembly that the 1997 Plan provide fair and equitable electoral

opportunities to all citizens of North Carolina. Consequently, members of the General

Assembly were concerned that failure to create a district in northeastern portion of the

state that provided African-American voters an equal opportunity to elect candidates of

choice would elicit significant opposition in the African-American community and its

advocates in the General Assembly which most likely would result in a denial of Section 5

preclearance.

7 Defendants and Defendant-intervenors contend that the State of North Carolina

had a compelling justification in creating Congressional District 1 in order to comply with

the strictures of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973.

a. Defendants and Defendant-intervenors contend that while the General

Assembly’s primary goals in enacting the 1997 Plan were to correct the prior

constitutional violation found by the Supreme Court in Shaw v. Hunt and to

preserve the congressional delegation’s partisan balance, the State was also under

an obligation to fulfill these objectives without diluting minority voting strength.

b. Defendants and Defendant-intervenors contend that there is a strong basis

in evidence for the North Carolina General Assembly to have believed in 1997, that

the three Gingles preconditions and the factors set forth in the Senate Report

accompanying Section 2, S. Rep. No. 97-417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982), at 28-

29, reprinted in 1982 U.S.C.C.A.N 177, 207, required to establish a Voting Rights

Act Section 2 claim exist in North Carolina:

1. Defendants and Defendant-intervenors contend, that the African-

American population in the area encompassed by Congressional District 1 is

sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute a majority in a

congressional district.

2. Defendants and defendant-intervenors contend, and plaintiffs have

stipulated and agreed for purposes of this trial, that the African-American

population is politically cohesive.

3. Defendants and defendant-intervenors contend, and plaintiffs have

stipulated and agreed for purposes of this trial, that the white majority votes

sufficiently as a bloc to enable it usually to defeat the minority’s preferred

candidate.

C. Defendants and defendant-intervenors contend, and plaintiffs have

stipulated and agreed for purposes of this trial, that African-Americans in North

Carolina for many decades were victims of racial discrimination and a substantial

majority of African-American citizens in North Carolina are still at a disadvantage

in comparison to white citizens with respect to income, housing, education and

health; furthermore, through the 1990 elections, some appeals have been made to

North Carolina voters on the basis of race.

d. Defendants and Defendant-intervenors contend that there is a strong basis

in evidence for the State Legislature of North Carolina to have determined in 1997

that it had a compelling interest in complying with the Voting Rights Act and in

ensuring that, under the totality of the circumstances, racially polarized voting

patterns and the lingering effects of the State’s past discrimination did not exclude

the State’s African-American citizens from equal access to the political process.

10. Defendants and Defendant-intervenors contend that Congressional District 1 is

narrowly tailored to meet a compelling justification. District 1 is narrowly tailored to

remedy the potential Section 2 violation in the northeastern portion of the State of North

Carolina. The African-American population in the area encompassed by District 1 is large

and geographically compact. District 1 is located in the northern and central Coastal Plain

where a high degree of racially polarized voting persists and the African-American

population is politically cohesive. Moreover, the North Carolina General Assembly did

not subordinate traditional redistricting criteria in creating District 1. District 1 is

contiguous and geographically compact, encompassing 10 whole counties and whole

precincts from portions of 10 other rural and economically disadvantaged counties with a

distinct community of interest. The 1997 Plan substantially encompasses the

configurations of District 1 initially proposed by the State House and State Senate, and the

modifications negotiated between the legislative chambers were not based on racial

considerations.

Defendant and Defendant-Intervenors Legal Contentions

}, Defendant and Defendant-intervenors contend that Plaintiffs are barred from litigating

the constitutionality of Congressional Districts 1 and 12 in this case. Under the doctrine of

claim preclusion, “a final judgment on the merits of an action precludes the parties or their

privies from relitigating issues that were or could have been raised in that action.” Federated

Dep’ t Stores Inc. v. Moitie, 452 U.S. 394, 398, 101 S. Ct. 2424, 2428, 69 L. Ed. 2d 103.

108 (1981). E.g., Allen v MCurry, 449 U.S. 90, 94, 101 S. Ct. 411, 414, 66 L. Ed. 2d 308.

313 (1980). All Plaintiffs in this case are bound by the decision by the district court in Shaw

v. Hunt holding that the 1997 Plan cured the constitutional defect found by the Supreme

Court in District 12 as urged by the Shaw plaintiffs. That decision is binding on Plaintiffs

Martin Cromartie and Chandler Muse, because they were plaintiffs in Shaw at the time of that

judgment and they had a full and fair opportunity to litigate their claims concerning District

1 and 12 in Shaw. Because they chose not to do so, they are barred from their attempt to

pursue the claim in this litigation. The remaining plaintiffs are equally barred from challenging

District 1 on the grounds that the Shaw plaintiffs were their “virtual representatives.” See

Ahng v. Alisteel, Inc., 96 F.3d 1033, 1037 (7th Cir. 1996); Chase Manhattan Bank, N.A. v.

Celotex Corp., 56 F.3d 343, 345-46 (2d Cir. 1995); Gonzalez v. Banco Cent. Corp., 27 F.3d

751, 761 (1stCir. 1994); Nordhorn v. Ladish Co., 9 F3d 1402, 1405 (9th Cir. 1993); Royal

Ins. Co. of Am. v. Quinn-L Capitol Corp., 960 F.2d 1286, 1297 (5th Cir. 1992); Jaffree v.

Wallace, 837 F.2d 1461, 1467-68 (11th Cir. 1988). Similarly, the adverse judgment in Shaw

holding District 12 constitutional is attributable to all the plaintiffs in this case and bars them

from litigating the constitutionality of District 12.

2. Defendant and Defendant-intervenors contend that Plaintiff James Ronald Linville

does not have standing to challenge the constitutionality of District 12. In this case, Plaintiffs

only have standing where he or she can establish that he or she was personally injured as a

result of residing in the challenged district or because he or she was otherwise personally

subjected to a racial classification. See United States v. Hays, 515 U.S. 737, 744-745 (1995).

Plaintiff James Ronald Linville is registered voter residing in District 5 of the 1997 Plan and

has not alleged that he has been injured as a result of having personally been denied equal

treatment on the grounds of race. He, therefore, has no standing to challenge the

constitutionality of District 12.

3 Defendant and Defendant-intervenors contend that plaintiffs have the burden of

proving that they have standing to pursue their claim and that race was the predominant factor

in the creation of the 1997 Plan. See Shaw, 517 U.S. at 905 (“The plaintiff bears the burden

of proving the race-based motive. . . .”) (citation omitted). See also Miller, 515 U.S. at 916.

4. Defendants and Defendant-intervenors contend that the North Carolina General

Assembly is entitled to a great deal of deference in creating a redistricting designed to remedy

the constitutional infirmities found by the Supreme Court and a presumption that it acted in

good faith during the redistricting process. Indeed, “[s]tates must have discretion to exercise

the political judgment necessary to balance competing interests” and “the good faith of state

legislature must be presumed.” Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. at 915. See also, e.g., Lawyer

v. Department of Justice, 521 U.S. ___ 117 S. Ct. at 2192-3 (1997), aff’g Scott v. United

States, 920 F. Supp. 1248, 1255 (M.D. Fla. 1996); Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. at 899 n.9;

Upham v. Seamon, 456 U.S. 37, 42 (1982); White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. at 794-95 (1973).

5 Defendant and Defendant-intervenors contend that federal law imposed a series of

obligations on the General Assembly in enacting the 1997 congressional redistricting plan.

First, one-person, one vote principles established by the Supreme Court in Baker v. Carr, 369

U.S. 186 (1962) and its progeny required the General Assembly to have a congressional

redistricting plan in which population was distributed equally among the congressional

districts in the plan. Second, the Voting Rights Act required the General Assembly to avoid

diluting the voting strength of minority citizens during the redistricting process. Third, the

Supreme Court decision in Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993), and its progeny required that

the General Assembly develop a plan in which race did not predominate and subordinate

traditional redistricting criteria.

6. Defendant and Defendant-intervenors contend that in order for the Court to apply

strict scrutiny in its evaluation of the 1997 Plan, it must find that “race for its own sake, and

not other districting principles, was the legislature’s dominant and controlling rationale in

drawing its district lines,” Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. at 952, quoting Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S.

at 913, and “that other, legitimate districting principles were ‘subordinated’ to race.” Bush,

517 U.S. at 958. See generally id. at 259-68. The North Carolina General Assembly was

permitted to conduct the 1997 redistricting “with consciousness of race.” Bush, 517 U.S. at

1051. See also, Bush, 517 U.S. at 993. (O’Connor, J., concurring) (States may intentionally

create majority-minority districts and may otherwise take race into consideration, without

coming under strict scrutiny) (emphasis in original); United States v. Hays, 515 U.S. 737, 745

(1995) (“We recognized in Shaw. . that the ‘legislature always is aware of race when it draws

district lines, just as it is aware of age, economic status, religious and political persuasion, and

a variety of other demographic factors. That sort of race consciousness does not lead

2% inevitably to impermissible race discrimination’) (citation omitted) (emphasis in original).

7 Defendants and Defendant-intervenors contend that, while the configuration of

District 12 reflects a strong correlation between the racial composition of the precincts and

party preference and the General Assembly’s goal of creating a partisan Democratic District

12, this fact does not make the 1997 constitutionally suspect. The General Assembly may

create a plurality strong partisan Democratic district “even if it so happens that the most loyal

Democrats happen to be black Democrats and even if the State were conscious of that fact.”

Hunt v. Cromartie, 119 S. Ct. 1545, 1547, 143 L. Ed. 2d 731, 741 (1999) (emphasis in the

original) (citing Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952, 968 (1996); Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. at 905;

Miller, 515 U.S. at 916; Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. at 646). Indeed,

Evidence that blacks constitute even a supermajority in one congressional

district while amounting to less than a plurality in a neighboring district will

not, by itself, suffice to prove that a jurisdiction was motivated by race in

drawing its district lines when the evidence also shows a high correlation

10

between race and party preference.

Hunt at 119 S. Ct. at 1547, 143 L. Ed. 2d at 741.

0, Defendants and Defendant-intervenors contend that the State of North Carolina had

a compelling justification in creating Congressional District 1 in order to comply with the

strictures of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973. Compliance with Section

2 of the Voting Rights Act can be a compelling state interest, King v. State Bd. of Elections,

979 F. Supp. 619, 621-22 (N.D. Ill. 1997), summ. aff., ___ U.S. __, 118 S. Ct. 877 (1998)

(4494 (per curiam) check subsequent cite, provided the State has a ““strong basis in evidence’ for

finding that the threshold conditions for Section 2 liability” exist. Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. at

978. See also Shaw, 517 U.S. at 914 (“§ 2 could be a compelling interest” justifying even a

plan drawn predominantly on a racial basis); Bush, 517 U.S. at 990 (O’Connor, J.,

concurring) (nothing in Shaw or its progeny should be interpreted as calling into question the

continued importance of complying with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act); id. at 992

(concluding that States have a compelling interest in complying with Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act “as [the Supreme] Court has interpreted it”); King v. State Board of Elections,

US. ___, 118 8. Ct. 877 (1998) (per curiam) (summarily affirming district court ruling

upholding the constitutionality of Illinois’ Fourth Congressional District found to be narrowly

tailored to a compelling justification of complying with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act);

DeWitt v. Wilson, 856 F. Supp. 1409, 1413-14 (E.D. Cal. 1994) (intentional creation of

majority-minority districts does not violate Constitution when redistricting plan “evidences

ajudicious and proper balancing of the many factors appropriate to redistricting, one of which

was the consideration of the application of the Voting Rights Act’s objective of assuring that

11

minority voters are not denied the chance to effectively influence the political process”), aff'd,

515 U.S. 1170 (1995); Clark v. Calhoun County, 88 F.3d 1393, 1405 (5th Cir. 1996)

(Higginbotham, J.) (a race-conscious Section 2 remedial plan is acceptable if it is narrowly

(444 22

tailored and it “substantially addresses’ the violation and “does not deviate substantially

from a hypothetical court-drawn § 2 district for predominantly racial reasons”) (citations

omitted).

10. Defendants and Defendant-intervenors contend that there is a strong basis in evidence

for the North Carolina General Assembly to have believed in 1997, that the three

preconditions established by the Supreme Court in Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986)

and the factors set forth in the Senate Report accompanying Section 2, S. Rep. No. 97-417,

97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982), at 28-29, reprinted in 1982 U.S.C.C.A.N 177, 207, required

to establish a Voting Rights Act Section 2 claim exist in North Carolina.

11. Defendants and Defendant-intervenors contend that Congressional District 1 is

narrowly tailored to remedy the potential Section 2 violation in the northeastern portion of

the State of North Carolina. In order to be narrowly tailored to remedy a potential Section

2 violation, the location of the remedial district must substantially correspond to the location

of the potential violation. See Shaw, 517 U.S. at 915-16 (“[w]here, as here, we assume

avoidance of § 2 liability to be a compelling state interest, we think that the racial

classification would have to realize that goal; the legislative action must, at a minimum,

remedy the anticipated violation or achieve compliance to be narrowly tailored”) (footnote

omitted); King, 979 F. Supp. at 623-27 (finding Fourth District narrowly tailored because it

“remedie[d] the anticipated violation and achieves 2 compliance, and that its consideration

12

of race (reflected by its noncompactness and irregularity) is no more than reasonably

necessary to fulfill its remedial purpose.”).

Defendant and Defendant-Intervenors Proposed Stipulations:

| Over 25 percent of North Carolina’s population (1.6 million persons) and almost 25

percent of the State’s geography were assigned to new congressional districts as a result of the

1997 redistricting.

2. 41.6% of the geographic area assigned to District 12 in the 1992 Plan remained assigned

to District 12 in the 1997 Plan.

3. 180,984 people assigned to District 1 in the 1992 Plan and 174,471 people assigned to

District 12 in the 1992 Plan were assigned to other congressional districts in the 1997 Plan.

4. While the 1992 Plan divided 80 precincts, the 1997 Plan divides two precincts.

5, While the 1992 Plan divided 44 counties, the 1997 Plan divides 22 counties.

6. District 1 in the 1992 Plan divided 25 precincts while District 1 in the 1997 Plan does not

divide any precincts.

7 While District 12 in the 1992 Plan contained parts of 10 counties, District 12 in the 1997

Plan contains parts of 6 counties.

8. District 1 of the 1997 Plan is contiguous.

9, District 12 of the 1997 Plan is contiguous.

10. The 1997 Plan does not utilize “point contiguity,” “cross-overs,” or “double-cross-overs”

to maintain contiguity.

11. District 12’s African-American total population was reduced from the original 56.63

percent in the 1992 Plan to 46.67 percent in the 1997 Plan.

12. District 12's voting-age population was reduced from the original 53.34 percent in the

1992 plan to 43.36 percent in the 1997 Plan.

13: The dispersion compactness score of District 12 more than doubled from .045 in the 1992

Plan to 0.109 in the 1997 Plan.

14. In the 1997 Plan, the average district in North Carolina increased its level of dispersion

compactness by 39.1%. The increase in the level of District 12's dispersion compactness score

was the largest of all congressional districts at 142.2%.

15. As measured by their dispersion and perimeter scores, the levels of compactness for North

Carolina’s twelve congressional districts increased in the 1997 Plan as compared to the 1992 Plan.

16. On average, 76.4 percent of the geographic area in each of North Carolina’s twelve

congressional districts in the 1992 Plan was preserved in the 1997 Plan, ranging from a high of

96.7 percent for District 11 to a low of 41.6 percent for District 12.

A A Regional Office

1444 Eye Street, N.W., 10th Floor

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND Washington, D.C. 20005

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. 202-682-1300 202-682-1312 Fax

November 22, 1999

Via Telefacsimile

Douglas E. Markham

Everett & Everett

Suite 300

301 W. Main Street

P.O. Box 586

Durham, North Carolina 27609-0629

Re: Pretrial Order

Dear Doug:

Given your position and plans regarding deposition designations and consistent with the

spirit of the Court’s Order, we will offer Dr. Gerald Webster’s affidavits and expert reports as

exhibits and designate portions of his deposition as evidence for trial.

Sincerely,

eA /

Todd A. Cox

Assistant Counsel

\Dn £ Lty

Tiare B. Smiley

Special Deputy Attorney General

Adam Stein

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDP) is not a part of the National ~~ National Office Regional Office

Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) although LDF was founded ~~ 99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600 315 West 9th Street, Suite 208

by the NAACP and shares its commitment to equal rights. LDF has had, since 1957, a separate New York, NY 10013-2897 Los Angeles, CA 90015

board, program, staff, office and budget. Contributions are deductible for US. income tax purposes. ~~ 212-965-2200 212-226-7592 Fax 213-624-2405 213-624-0075 Fax

NATIONAL OFFICERS

Julius L. Chambers

Martin D. Payson

Co-Chairs

Daniel L. Rabinowitz

Roger W. Wilkins

Co-Vice Chairs

Elaine R. Jones

President and

Director-Counsel

James M. Nabrit, III

Secretary

Eleanor S. Applewhaite

Treasurer

Theodore M. Shaw

Associate Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

Director of Litigation

Edward H. Gordon

Director of Finance

and Administration

Patricia A.M. Grayson

Director of Development

Billye Suber Aaron

Gerald S. Adolph

Clarence Avant

Mario L. Baeza

Mary Frances Berry

Theodore L. Cross

Kenneth C. Edelin

Toni G. Fay

Willie E. Gary

Anthony G. Amsterdam

William H. Brown, III

Yvonne Brathwaite Burke

William K. Coblentz

William T. Coleman, Jr.

Charles T. Duncan

Nannette B. Gibson

Alice M. Beasley

Anita Lyons Bond

Patricia S. Bransford

Talbot D’Alemberte

Allison S. Davis

Ossie Davis

Peter J. DeLuca

Adrian W. DeWind

Anthony Downs

Robert F. Drinan

Marian Wright Edelman

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Gordon G. Greiner

Quincy Jones

Vernon E. Jordan, Jr.

David E. Kendall

Caroline Kennedy

Tonya Lewis Lee

William M. Lewis, Jr.

David S. Lindau

John D. Maguire

SENIOR DIRECTORS

Jack Greenberg

Louis Harris

Eliot Hubbard, III

Anna Faith Jones

Jetta N. Jones

Robert H. Preiskel

DIRECTORS EMERITUS

Christopher F. Edley

Clarence Finley

Norman C. Francis

Marvin E. Frankel

Ronald T. Gault

Lucy Durr Hackney

Patricia L. Irvin

Herman Johnson

Harry Kahn

Nicholas DeB. Katzenbach

George E. Marshall, Jr.

Paul Moore, Jr.

Cecilia S. Marshall

C. Carl Randolph

Judith T. Sapers

William H. Scheide

Dean E. Smith

John W. Walker

George Wallerstein

Karen Hastie Williams

Hon. Andrew Young

Robert O. Preyer

Norman Redlich

Charles B. Renfrew

Frederick A.O. Schwarz, Jr.

Jay Topkis

James Vorenberg

M. Moran Weston

Glendora Mcllwain Putnam

Henry T. Reath

Jacob Sheinkman

George C. Simkins

Wayman F. Smith III

Michael I. Sovern

Bonnie Kayatta Steingart

Chuck Stone

Cyrus Vance

Paula Weinstein

E. Thomas Williams, Jr.

October1998