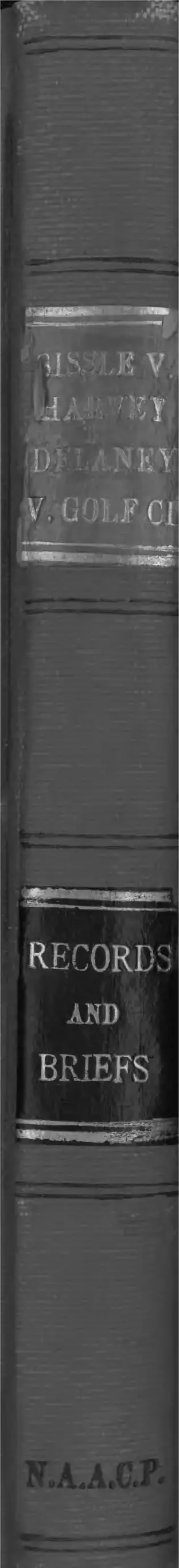

Sissle v. Harvey, Inc.; Delaney v. Golf Club Records and Briefs

Public Court Documents

June 29, 1936 - June 2, 1942

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sissle v. Harvey, Inc.; Delaney v. Golf Club Records and Briefs, 1936. 35fd6178-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b478fb8a-4860-403e-8ba1-4da2e66f39e9/sissle-v-harvey-inc-delaney-v-golf-club-records-and-briefs. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

RECORDS

AND

BRIEFS

In the Supreme Court of Ohio

A ppeajl F rom:

T h e Court of A ppeals of Cuyahoga County.

ELLEN SISSLE,

Plaintiff and Appellant,

vs.

HARVEY, INC.,

Defendant and Appellee.

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFF AND APPELLANT

In Support of Motion to Certify, and Opinions.

Chester K. Gillespie and

N orman L. M cG hee,

501 Erie Building, Cleveland, Ohio,

Attorneys for Appellant.

George F. Q u in n ,

National City Bldg., Cleveland, Ohio,

Attorney for Defendant and Appellee.

Th e Ga te s L egal P u b l is h in g Co., Cl e v e l a n d , O.

No.

In the Supreme Court of Ohio

A ppeal F rom

T he Court of A ppeals of C uyahoga C ounty .

ELLEN SISSLE,

Plaintiff and Appellant,

vs.

HARVEY, INC.,

Defendant and Appellee.

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFF AND APPELLANT

In Support of Motion to Certify, and Opinions.

Chester K. G illespie and

N orman L. M cG hee,

501 Erie Building, Cleveland, Ohio,

Attorneys for Appellant.

George F . Qu in n ,

National City Bldg., Cleveland, Ohio,

Attorney for Defendant and Appellee.

INDEX.

Facts ................................................................................ 1

Assignments of Error..................................................... 3

Argument of the Law............................. 3

Conclusion ...................................................................... 12

Appendices:

I. Opinion of Court of Appeals............................. 15

II. Opinion of Municipal Court of Cleveland. . . . 20

Authorities Cited.

Anderson v. State, 30 C. D., 510................................... 10

Brown vs. Bell Co., 146 Iowa, page 89....................... 11

Burks vs. Bosso, 180 New York, 341......................... 8

Darius v. Apostolos, Colorado Supreme Court, 190

Pac., 510, decided December 1, 1919....................... 7

Fowler v. Benner, 23 O. D., 59..................................... 4

Gillock v. The People, 171 111., 307............................. 7

Guy v. Tri-State Amusement Co., 7 O. A., 509.......... 10

Johnson v. Humphrey, etc. Co., 14 C. D., 135.............. 10

McNicoll v. Ives, 4 Ohio Dec., 76................................. 9

McReynolds v. The People, 230 111., 623..................... 7

Morris v. Williams, 39 O. S., 554............................. 9

Puritan Lunch Co. v. Forman, 45 C. C. R., at page 531 10

State v. Williams, 35 Mo. App., 541.......................... 6

United States Cement Co. v. Cooper, 172 Ind., 599 7

Woodworth v. The State, 26 Ohio St., 196................. 5

Youngstown Park & Falls Raihvay Company vs.

Tokus, etc., 4 Ohio App., 281............................... 1, 11

27 Minn., 460 and 462.................................................... 4

172 Mo., 523 and 524.................................................. 4

36 Vt., 645, 648 .............................................................. 4

Bouvier’s Laiv Dictionary, Volume 3, page 2763. . . . 3

1 Corpus Juris, 518...................................................... 4

Greenleaf’s Evidence, Section 1 2 8 ............................ 4

1 Sutherland Statutory Construction (2 ed.), Section

437 ........................................................................... 7

Ohio Jurisprudence, Volume 7, pages 489 and 490. . 11

General Code of Ohio, Section 12940.......................... 3,9

No

In the Supreme Court of Ohio

A ppeal F kom

T he Couet oe A ppeals of Cuyahoga Co u nty .

ELLEN SISSLE,

Plaintiff and Appellant,

YS.

HARVEY, INC.,

Defendant and Appellee.

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF

PLAINTIFF AND APPELLANT.

The parties will be referred to as they appeared in

the Municipal Court of the City of Cleveland, wherein

this appellant was plaintiff and this appellee was defend

ant.

FACTS.

This cause comes into this Court on a motion for an

order requiring the Court of Appeals of Cuyahoga

County to certify its record to this Court for review. The

basis for the motion is that the case is one of general and

great public interest, and is in direct conflict with

Youngstown Park & Falls Railway Company vs. Tokus,

etc., 4 Ohio App., 281.

2

Ellen Sissle, appellant herein, says that on June 29,

1936, in cause No. 15,405, in the Court of Appeals of

Cuyahoga County, in which this appellant was appellee

and this appellee was appellant, a judgment was ren

dered in favor of Harvey, Inc., this appellee, reversing a

judgment theretofore entered in this cause in the Mu

nicipal Court of the City of Cleveland, in favor of the ap

pellant herein, Ellen Sissle, in the sum of one hundred

($100.00) dollars, and costs.

On and prior to February 18, 1935, the appellee here

in owned and operated a women’s wearing apparel shop

in the Terminal Tower Building, Cleveland, Ohio, cater

ing to the public in general. On the said February 18,

1935, this appellee refused to sell the appellant, because

she was colored and of African descent, some ladies’

underwear.

The facts in this case are not in controversy here

in.

The Cuyahoga County Court of Appeals made the

following entry:

“ Judgment reversed as contrary to law in that

this retail store is not a place of public accommoda

tion or amusement. Exceptions. Final judgment for

plaintiff in error. Exceptions. Judge Levine dis

sents.”

This Court will find in the appendix hereof a written

decision by Judge Drucker of the Municipal Court of

Cleveland overruling a demurrer which v7as filed by this

appellee, and the decision by Judges Terrell and

Lieghley of the Cuyahoga County Court of Appeals.

Judge Levine did not write a dissenting opinion.

ASSIGNMENTS OF ERROR.

(1) Said judgment by the Court of Appeals is

erroneous and against the just rights of this

appellant.

(2) The Court of Appeals erred in not sustaining

the judgment of the Municipal Court of Cleve

land.

(3) The Court of Appeals erred in not entering a

judgment for this appellant.

(4) The judgment of the Court of Appeals is con

trary to law.

ARGUMENT OF THE LAW.

There is only one question to be determined by this

Court and that is whether or not this retail store, or

women’s wearing apparel shop, is a place of public ac

commodation within the meaning of Section 12940 of

the General Code of Ohio. This section, so far as per

tinent, reads as follows:

‘ ‘ D enial oe P rivileges, at I nns and O ther P laces by

R eason of C olor,

Whoever, being the proprietor or his employee,

keeper or manager of an inn, restaurant, eating

house, barber-shop, public conveyance by land or

water, theatre or other place of public accommoda

tion and amusement, denies to a citizen, except for

reasons applicable alike to all citizens and regard

less of color or race, the full enjoyment of the ac

commodations, advantages, facilities or privileges

thereof, or, being a person who aides or incites the

denial thereof, * *

The Court’s attention is directed to the following

definitions:

“ Bouvier’s Law Dictionary, Volume 3, page 2763:

P ublic . The whole body politic or all the citi

zens of the state. A distinction has been made be

4

tween the terms public and general. The former

term is applied strictly to that which concerns all

the citizens and every member of the state. When

the public interest and its rights conflict with those

of an individual, the latter must yield. ’ ’

In Fowler v. Benner, 23 0. D., 59, it was held that a

place of public accommodation means a place where the

wants and desires of those who frequent it may be sup

plied for consideration. Accommodation is defined in

Webster’s as being whatever supplies a want or affords

ease, refreshment or convenience; or anything furnished

which is desired or needful. See 1 Corpus Juris, 518.

Webster’s Dictionary, also, defines “ place” as a

particular space or room.

Certainly there can be no difficulty in regarding this

women’s wearing apparel shop as a “ place.”

Webster’s Dictionary defines “ public” as an adjec

tive, depends for its meaning upon the subject to which

it is applied. Open to all the people, shared in or to be

shared in or participated in by the people at large; not

limited or restricted to any particular class of the com

munity. See 172 Mo., 523 and 524.

In 27 Minn., 460 and 462, the word public is said to

have two proper meanings; a thing may be said to be

public when owned by the public and also when its uses

are public. In 36 Vt., 645, 648, the term is said to sig

nify that which is open to general or common use. Green-

leaf’s Evidence, Section 128 points out that it is some

times used as synonymous with general, meaning that

which concerns a large number of persons.

We have said that there is conflict between the deci

sion of the Cuyahoga County Court of Appeals and that

rendered in 4 Ohio App., heretofore referred to, and,

5

for that reason we are setting forth said decision some

what at length, which reads in part as follows :

“ It is claimed on the part of the plaintiff com

pany that a public dancing pavilion is not included

within the terms of the statute. It will be noticed

that after naming inns, restaurants, eating houses,

barber-shops, conveyances by land or water and

theatres, it then reads ‘ or other place of public ac

commodation and amusement, ’ and it is claimed that

dancing pavilions are not included within the term,

‘ other place of public accommodation and amuse

ment. ’

It is urged that this is a penal statute and should

be strictly construed; that the maxim ejusdem

generis should be applied in the construction of this

statute; that where certain persons, objects or things

are named and followed by general terms, the gen

eral terms should be construed to apply to objects,

persons or things of similar or like kind.

This is a well-recognized rule of statutory con

struction which is intended to aid the court in deter

mining the true meaning of a statute, but it should

not be used to limit or abridge the well-defined mean

ing of the legislature gathered from the ordinary

meaning of the words used in the statute, keeping in

mind the object that the legislature had in its enact

ment.

In the case of Woodworth v. The State, 26 Ohio

St., 196, the supreme court of this state construed a

similar expression in a statute reading as follows:

‘ That if any person shall abuse any judge or

justice of the peace, resist or abuse any sheriff,

constable or other officer, in the execution of his

office, the person so offending, etc.’

In the opinion, pages 197 and 198, Mcllvaine, J.,

uses the following language in reference to this

rule of construction:

6

‘Now, it must be remarked that the rule of

construction referred to above, can be used only as

an aid in ascertaining the legislative intent, and

not for the purpose of confining the operation of a

statute within limits narrower than those intended

by the lawmaker. It affords a mere suggestion to

the judicial mind that, where it clearly appears

that the lawmaker was thinking of a particular

class of persons or objects, his words of more

general description may not have been intended

to embrace those not within the class. The sugges

tion is one of common sense. Other rules of con

struction are, however, equally potent, especially

the primary rule, which suggests that the intent of

the legislature is to be found in the ordinary mean

ing of the words of the statute. Another well-

established principle is, that even the rule re

quiring the strict construction of a penal statute,

as against the prisoner, is not violated by giving

every word of the statute its full meaning, unless

restrained by the context. ’

We find that this case has been cited by the

courts of many other states and the principle there

laid down followed.

The court of appeals of Missouri, in the case of

State v. Williams, 35 Mo. App., 541, refer to this

rule as follows:

‘ The rule for the construction of statutes,

“ that where the particular words of a statute are

followed by general,—as if, after the enumeration

of classes of persons or things, it is added, ‘ and

all others, ’—the general wTords will be restricted in

meaning to objects of the like kind with those

specified,” will not be applied where the applica

tion of the rule would be in the face of the evident

meaning of the legislature, the object of the rule

being not to defeat but to carry out the legislative

intent; and so, where the expression in a statute

7

is special or particular, but the reason is general,

the expression should be deemed general; and an

interpretation must never be accepted that will

defeat its own purpose, if it will admit of any

other reasonable construction.’

We especially call attention to this case on ac

count of the many citations contained in the opinion

construing the ruling.

We also cite on this subject 1 Sutherland Statu

tory Construction (2 ed.), Section 437; Gillock v.

The People, 171 111., 307; McReynolds v. The People,

230 111., 623; United States Cement Co. v. Cooper, 172

Inch, 599.

Turning now to the statute under ivhich this ac

tion was brought, and looking at the evident intent

of the legislators, from the language of the statute

itself we find that they were evidently intending to

give every citizen equal rights in public places to

which they were accustomed to go, either for accom

modation or amusement. The legislature did not

have in mind specially certain places which they

name and others of a similar or like kind, but the

object they had in view was the citizen. They in

tended that there should be no discrimination on ac

count of color or race to citizens who might apply at

public places for either accommodation or amuse

ment.

While the maxim insisted upon is a rule of statu

tory construction which a court in construing this

statute should consider, yet we think that it should

not be permitted to override the clear intention of

the lawmakers as evidenced from the plain reading

of the statute itself, and we think that a public danc

ing pavilion comes under the provisions of this stat

ute, included in ‘ other place of accommodation and

am.usement.’ ”

Following this same line of thought, the Court’s at

tention is directed to Darius v. Apostolos, Colorado Su

preme Court, 190 Pac., 510, decided December 1, 1919:

8

“ A bootblaoking stand is a place of public ac

commodation within the meaning of a statute, im

posing a penalty for refusal of accommodations of

inns, restaurants, eating houses, barber-shops, pub

lic conveyances, theatres, and all other places of

public accommodation and amusement.

The rule of ejusdem generis does not apply

where there is a diversity in character of the things

specifically enumerated in the statute.

The legal presumption is that words and

phrases in a statute are used in their usual sense

unless the intent clearly appears to use them in a

more restricted or different sense.

No constitutional rights of one operating a

bootblacking stand are infringed by a statute for

bidding him under penalty to refuse service to any

person applying therefor.

The Colorado Civil Rights Statute, Section 1,

chapter 61, Laws of 1895, page 139, provides that

all persons shall be entitled to the equal enjoyment

of the accommodations, advantages, facilities and

privileges of inns, restaurants, eating houses, bar

ber-shops, public conveyances on land or water, the

atres, and all other places of public accommodation

and amusement, etc.”

The Cuyahoga County Court of Appeals relied a

great deal upon Burks vs. Bosso, 180 New York, 341.

The Colorado Supreme Court in the case quoted above

had the following to say with regard to this New York

case:

“ The decision in the New York case was as as

serted by defendant, but we are of the opinion that

it is based upon false reasoning.”

It is, of course, well settled in Ohio, that the primary

aids to a proper construction of a statute are its object

and the ordinary meaning of the words used. The rule

9

is well settled in Morris v. Williams, 39 0. S., 554, where

the court refused to limit the general wording of the

statute and said:

“ It is a familiar rule in the construction of stat

utes, that the language, where clear and compre

hensive, is not to be limited in view of the partic

ular instances which may be supposed to have led to

its adoption, but the act should be held to embrace

all cases fairly coming within its terms if they are

also within its reason and spirit. Goshin v. Purcell,

11 0. 8. 641, 649.”

In McNicoll v. Ives, 4 Ohio Dec., 76, at 78, the court

said:

“ And it is now the well settled rule in the con

struction of statutes in Ohio that words are to re

ceive their ordinary and natural import, and that

' the act should be held to embrace all cases coming

fairly within its terms.”

Thus it appears by Ohio authority that the rule of

construction under consideration does not exist for the

purpose of confining the operation of a statute within

limits narrower than those intended by the lawmaker and

that this act should be so construed as to embrace all

cases coming fairly within its terms.

Section 12940 of the General Code of Ohio was orig

inally enacted in 1894, and the preamble is as follows:

“ Whereas it is essential to just government that

we recognize and protect all men as equal before the

law; and that a democratic form, of government

should mete out equal and exact justice to all, of

ivhatever nativity, race, color or persuasion, reli

gious or political; and it being an appropriate object

of legislation to enact great fundamental principles

into law, therefore, * * *.”

10

The Court’s attention is further directed to Puritan

Lunch Co. v. Forman, 45 C. C. R., at page 531:

“ Such discriminations are 'peculiarly galling to

their victims. They carry with them a sense of

ignominy because they are an injustice which the sub

ject of it can neither resent nor remedy, and they

publish him to the world as one who, ■without fault on

his part, is to he gibbeted at the cross roads of public

scorn and contumely. The height of this unmerited

social outlawry, ivas reached when the Supreme Court

of the United States declared judicially that the os

tracised race could not be citizens and were regarded

when our constitution was framed as having no

rights which a white man was bound to respect.

To correct this judgment of barbarism teas the

purpose of what is generally known as civil rights

legislation, of which the statute being considered is

a part.’”

At page 535:

“ The race over which the shield of the statute

extends its protection, is not an inferior race; it

is a belated race—made late in the race for success

by the systematic and legalized robbery for two hun

dred and forty years of that which alone makes a

man ennobled—his right to labor and eat the bread

which in the sweat of his own face he has earned.

There is sufficient history behind it—and indeed

in its presence—to admonish the courts why and how

it became necessary and commended its prohibition

to the lawmaking power, and to administer it in the

light of that history. Its purpose was to contradict

the pitiless affront to a being created in the image

of a common and impartial maker.”

Please see, also, Johnson v. Humphrey, etc. Co., 14 C. D.,

135; Guy v. Tri-State Amusement Co., 7 0. A., 509; and

Anderson v. State, 30 C. D., 510.

11

Volume 7, pages 489 and 490, of Ohio Jurisprudence

concurs with us when we say the decision rendered by

the Cuyahoga County Court of Appeals in this case is in

conflict with the Youngstown case, supra,—

“ The phrases public places and public accommo

dation are, however, to. be limited by the specific

designations which precede it. A business to fall

within the prohibition must be of the same general

character and kind as the places specifically desig

nated ; it must be a place of public character. How

ever there is authority to the contrary, it being held

that the general rule of construction of a penal

statute, where certain persons or objects are named

and followed by general terms that the general terms

are construed to apply to persons or objects of a

kind similar to those specified, does not apply to the

Civil Rights Statute, where the meaning of the legis

lature is plain.”

and then the author refers you to Youngstown etc. v.

Tokus, supra.

Our Cuyahoga County Court of Appeals referred in

its decision to Brown vs. Bell Co., 146 Iowa, page 89.

A careful reading by this Court of said case, we are sure,

will convince it that it is not clearly in point.

The Court held a coffee merchant who rented floor

space from an association conducting a pure food show

from which he advertised coffee by serving the same to

prospective patrons without charge and for purely ad

vertising purposes, but had no interest whatever in the

pure food show or the admission fees charged therefor,

could rightfully refuse to serve persons of a particular

class although they paid the admission fee to the pure

food show; and he was not, therefore, liable under the

Civil Rights Statute for refusing to serve a colored per

son with coffee.

12

We doubt very seriously whether or not a person

could be held to have violated Section 12940 of the Gen

eral Code of Ohio when he is giving merchandise or any

thing else away. We repeat that we believe that this

Court will agree with us when we say that the Iowa case

is not a case in point.

The Illinois case cited was decided in 1895 and dealt

with a drug store. Said case is not in point either.

CONCLUSION.

We believe that opportunity is here afforded for the

Supreme Court of Ohio to definitely set at rest the con

ditions as regards the applicability of our Civil Eights

Statutes and of the intent of the legislative body when

these statutes were enacted.

We have set forth herein the various legal tech

nicalities which have been used by some courts in at

tempting to thwart the legislative intent, embodied in the

preamble and history of the Act, as well as the Act itself.

These various technicalities are boiled down to three sig

nificant contentions:

(1) That the Act is of a penal nature and, therefore,

should be strictly construed.

(2) That the doctrine of ejusdem generis should

apply by reason of a presumed similarity of a

type of places specifically mentioned in the Act.

(3) That the Act applies to places of public owner

ship rather than those relating to private owner

ship.

It is generally conceded that, notwithstanding the

doctrine of ejusdem generis or the rule for strict con

struction of penal statutes, the legislative intent sur

rounding a given enactment of law shall govern the in

terpretation and application of the Act. This being true,

13

in. the face of the declared purpose of the Act as set forth

in the preamble contained herein, it is but logical to con

clude that neither the doctrine of strict construction, be

cause of the penal nature of the Act, nor the doctrine of

ejusdem. generis may be used as a rule of construction

of this Act.

Attempting to classify the enumerated types of

places into the nature of their ownership, that is public

or private, is of no force. The statute definitely includes

both privately and publicly owned businesses.

The New York case, supra, was based on the penal

nature of the statute, and we have already noted herein

that the penal nature of the Ohio statute has no bearing

on this case. The Colorado decision, supra, was based

on the dissimilarity of the places named in the Act, and

sustains our position.

We definitely contend that the Civil Rights Stat

utes of Ohio were enacted primarily and distinctly for

the purpose of assuring equal privileges in all types of

places of public accommodation or amusement, and that

no place offering a service to the public or tendering

merchandise for sale or hire can be regarded as exclu

sive from the prohibitory provisions of this Act.

Law is like any other human institution and cannot

successfully resist progress when crystallized public

sentiment demands it. We feel that public sentiment has

been crystallized in Ohio and does demand a more pro

gressive interpretation of the Act than given it by the

Cuyahoga County Court of Appeals.

The law is designed for man’s use and not for his

enslavement. The legal pattern found adequate for yes

terday should not be invoked where it no longer fits the

needs of today.

14

Courts nowadays should be more concerned with

substantial justice than the mere hair-breadth interpreta

tions of laws.

If this decision is permitted to stand, every Negro

in Ohio will be at the mercy of unscrupulous vendors.

During the hearing of this case in the Cuyahoga

County Court of Appeals, everyone admitted, including

the judges of that court, that said court’s decision means

that a corner grocery store could refuse to sell a loaf of

bread to a Negro because he was a Negro; that any de

partment store could refuse to sell a Negro a suit of

clothes; and that no retail store and no drug store in

Ohio would be required to serve Negroes.

As we have tried to indicate hereinbefore, such an

interpretation of the statute, when one contemplates its

history, the preamble, and crystallized public sentiment,

is perfectly stupid.

W herefore, we believe that this Court should grant

this motion, seeking an order directing said Court of

Appeals to certify its record to this Court.

Respectfully submitted,

C hester K. G illespie and

N orman L . M oG hee ,

Attorneys for Plaintiff and

Appellant.

15

APPENDIX I.

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS.

S tate of O h io , E ig h th D istrict,

Cuyahoga C o u nty .

No. 15,405.

H arvey, I n c .,

Plaintiff in Error,

vs.

E llen S issle,

Defendant in Error.

OPINION.

June 29th, 1936.

(E rror to the M u n icipal Court of Cleveland ,)

L ieghley , P.J.

The plaintiff Ellen Sissle recovered a judgment

against the defendant, Harvey, Inc., for the sum of One

Hundred Dollars based upon a claim that she was re

fused service in a store of the defendant in violation of

Section 12,940 General Code. This section, so far as per

tinent, reads as follows:

‘ ‘ D enial of P rivileges at I nns and O th er P laces

by R eason of C olor. Whoever, being the proprietor

or his employee, keeper or manager of an inn, res

taurant, eating house, barber-shop, public convey

ance by land or water, theatre or other place of pub

lic accommodation and amusement, denies to a citi

zen, except for reasons applicable alike to all citizens

and regardless of color or race, the full enjoyment of

16

the accommodations, advantages, facilities or privi

leges thereof, or, being a person who aides or incites

the denial thereof, * # *”

This case was presented to us for review on error.

The plaintiff claims that this retail store maintained

by defendant to sell apparel for women is comprehended

within this Act. The defendant denies it. This is the

issue upon which the case must be determined.

The question is whether or not the general language

contained in the Act ‘ ‘ or other place of public accommo

dation and amusement” is limited in its application to

the particular words or particular activities theretofore

mentioned and specified in the Act. It should be noted

that these specific words relate principally to places

maintained for lodging or providing food or public con

veyance or theatres. Of course, any business by what

ever name of which any specific or particular word or

phrase used in the Act is definitive is controlled thereby.

There is no specific mention in the Act of retail stores

or the professions or any of the many other occupations

and trades in which the citizens of the State engage that

are unlike and dissimilar to those specified.

It has long been a rule of statutory construction in

this State that whenever general words follow particular

words, the application of the general wTords must be lim

ited to things of the same kind and character as those

specified. The only exception to this rule is any instance

in which its application results in an apparent limit or

defeat of the legislative intent evidenced by the language

and apparent purpose of the Act itself.

If the legislative intent was general and all-inclusive

as claimed by counsel for plaintiff, it would have been a

very simple matter to have used general language only.

17

The fact that particular words and phrases were em

ployed and these particular activities thereby empha

sized rebuts any contention that the intent was general

and all-comprehensive. This Court would be legislating

to construe the general words following the particular

in the manner urged and would be doing so in defiance

of the well and long established rule of statutory con

struction.

If the legislative intent was an all-embracing Act,

then that body engaged in a tautological performance in

writing Section 25 into the Liquor Control Act in 1933.

(Section 6064-25 G. C.) Likewise, when it wrote Section

9401 and Section 12954 General Code into the Statutes

relating to any company engaged in the insurance busi

ness imposing punishment for any discrimination.

For cases dealing with this subject of construction

in Ohio reference is made to Volume XI, Page’s Com

plete Ohio Digest, (last edition) page 642.

Also the following section under the title “ Civil

Rights” in Volume VII, Ohio Jurisprudence, page 494,

Section 26:

“ R etail S tobes.—Retail stores are private busi

nesses, not intended to be included within the Civil

Rights statute. A drug store is not included within

the statute, although it has a soda fountain business,

which is merely an adjunct to the drug business. ’ ’

The general law relating to this rule is stated and

summarized in Vol. V, Ruling Case Law, page 586 in the

following language:

“ And so where the law enumerates certain places

such as inns, eating houses, theaters, and public con

veyances, and concludes with a general clause cov

ering ‘ all other places of public accommodation and

amusement,’ entitling all persons to the full and

18

■equal accommodations therein, it is clearly estab

lished as a rule of construction that if, after enumer

ating certain places of business on which a duty is

imposed or for which a license is required, the same

statute then employs some general term to embrace

other cases, no other cases will be included in the

general term except those of the same general char

acter or kind as those specifically enumerated.”

It will be noted that this text is supported by emi

nent authority. Included within the cases listed in the

foot notes are:

Cecil vs. Green, 161 111. 265;

Burke vs. Bosso, 180 N. Y. 341;

Brown vs. Bell Co., 146 la. 89.

It is doubtful if any reported case of any court of

well recognized standing and authority can be found any

where in conflict with those hereinbefore cited or referred

to supporting this rule that compels our conclusion.

Counsel for plaintiff emphasizes the language of the

opinion in the case of Youngstown Railway Company vs.

Tokus, 4 Ohio App. page 276. The holding in this case

is that a dancing pavilion is within the statute. We

agree therewith as such a place as was involved is clearly

a public place of amusement. Much that the court said

in its opinion is obiter. It cites cases dealing with public

places. It cites none wherein a business that is at least

to some extent a private business involving to some ex

tent the constitutional right of private contract is con

sidered and decision rendered in respect thereto. This

decision involving a dance pavilion does not conflict with

the holding in the case at bar involving a retail store.

In olden times we were taught that the right of

private contract was a constitutional guaranty. If a

farmer had grain or cattle to sell or a manufacturer had

19

machinery to sell or a merchant had merchandise to sell,

we were told that he could sell it whenever, to whomso

ever and upon whatever terms he chose. He could re

fuse to sell to a German, Irishman, Negro, Jew or any

other person for any or no reason. It is now said that

this former concept must be modified to the extent that

anyone who offers the market price for his wares may

enforce the sale. Before this modification of the right

of private contract becomes organic law, it should at

least receive express legislative declaration.

The majority of this Court are of the firm conclu

sion that these general words relate only to places of

similar character and kind to those specifically men

tioned. Retail stores are private businesses not with

in the provisions of the Civil Rights Statute as now

framed. Whatever our private ideas may be in the

matter, this rule of statutory construction in force in

Ohio and other states compels us to hold that this judg

ment is contrary to law.

The remedy of the plaintiff and all others who are

unfortunately in her position and claim to have similar

grievances lies with the legislature through an amend

ment to this statute.

The judgment is reversed as contrary to law and

final judgment entered for plaintiff in error.

T eebell, J ., concurs in the judgm ent.

L evine , J., dissents.

Counsel for Plaintiff in Error:

M esses. Q u in n , H obning & L a P orte.

Counsel for Defendant in Error:

Chester K . G illespie , E sq.

20

APPENDIX II.

No. 752,837.

IN THE MUNICIPAL COURT OF CLEVELAND.

S ta te of Oh io , C uyahoga C o u n ty , s s .

E l l e n S is s l e ,

Plaintiff,

vs.

H a rvey , I n c .,

Defendant.

OPINION.

D r u c k er , J. :

This is an action for damages brought by the plain

tiff, a colored person, to subject the defendant to the

statutory liability imposed by Sec. 12941, G. C. The peti

tion avers in substance that the plaintiff, a citizen, was

denied the full enjoyment of the accommodations, ad

vantages, facilities or privileges of the Women’s Ap

parel Shop, owned and operated by the defendant, for

reasons not applicable alike to all citizens and regardless

of color or race but on account of her color, and in viola

tion of Sees. 12940 and 12941 of the General Code.

The defendant interposes a demurrer to the peti

tion on the ground that it does not state facts sufficient

to constitute a cause of action. The question for deci

sion on this demurrer is whether the defendant’s shop

and place for the retail sale of women’s apparel is a

place of “ public accommodation” within the meaning of

G. C. 12940.

21

It is urged on the part of the defendant that a wom

en’s apparel shop is not a place of public accommoda

tion within the meaning of the statute. The statute, how*-

ever, naming inns, restaurants, eating houses, barber

shops, conveyances by land or water, and theaters, then

reads: “ or other place of public accommodation and

amusement” ; and it is claimed that defendant’s shop

does not come within the term “ other place of public ac

commodation and amusement. ” It is also urged that this

is a penal statute and should be strictly construed; that

the maxim ejusdem generis should be applied in the con

struction of this statute; that where certain persons, ob

jects or things are named and followed by general terms,

the general terms should be construed to apply only to

objects, persons or things of similar or like kind. The

plaintiff, on the other hand, contends that this rule of

statutory construction is not exclusive and should not be

employed to defeat the clear intent of the legislature in

enacting this statute.

It is, of course, well settled in Ohio, that the primary

aids to a proper construction of a statute are its object

and the ordinary meaning of the words used. The rule is

well settled in Morris v. Williams, 39 0. S. 554, where

the court refused to limit the general wording of the

statute and said:

“ It is a familiar rule in the construction of stat

utes, that the language, where clear and compre

hensive, is not to be limited in view of the particular

instances which may be supposed to have led to its

adoption, but the act should be held to embrace all

cases fairly coming within its terms if they are also

within its reason and spirit. Goshin v. Purcell, 11

0. S. 641, 649.”

In McNicoll v. Ives, 4 Ohio Dec. 76, at 78, the court

said:

22

“ And it is now the well settled rule in the con

struction of statutes in Ohio that words are to re

ceive their ordinary and natural import, and that the

act should be held to embrace all cases coming fairly

within its terms.”

The court cited among a number of other Ohio cases that

of Morris v. Williams, supra. In both the Morris case

and McNicoll case the rule of construction now urged by

this defendant was insisted upon.

A statutory expression similar to that in the instant

case was construed by the Supreme Court in Woodworth

v. State, 26 0. S. 196. The statute read as follows:

“ That if any person shall abuse any judge or

justice of the peace; resist or abuse any sheriff, con

stable, or other officer, in the execution of his office,

the person so offending,” etc.

Mcllvaine, J., used very pertinent language in that case

in reference to this rule of construction:

“ Now, it must be remarked that the rule of con

struction referred to above, can be used only as an

aid in ascertaining the legislative intent, and not for

the purpose of confining the operation of a statute

within limits narrower than those intended by the

lawmaker. It affords a mere suggestion to the

judicial mind that, where it clearly appears that the

lawmaker was thinking of a particular class of per

sons or objects, his words of more general descrip

tion may not have been intended to embrace those

not within the class. The suggestion is one of com

mon sense. Other rules of construction are, how

ever, equally potent, especially the primary rule,

which suggests that the intent of the legislature is to

be found in the ordinary meaning of the words of the

statute. Another well-established principle is, that

even the rule requiring the strict construction of a

penal statute, as against the prisoner, is not violated

by giving every word of the statute its full meaning,

unless restrained by the context.”

Thus it appears by Ohio authority that the rule of

construction under consideration does not exist for the

purpose of confining the operation of a statute within

limits narrower than those intended by the lawmaker

and that this act should be so construed as to embrace

all cases coming fairly within its terms.

In Youngstown Ry. Co. v. Tokus, 4 Ohio App. 276, a

public dance pavilion was held to be a place of public

amusement within the meaning of the statute under con

sideration. The defendant in that case urged the same

rule of construction as is urged in this case and the court,

after endorsing the quotation from the opinion of Judge

Mcllvaine, supra, said, at page 281:

“ Turning now to the statute under which this

action was brought, and looking at the evident intent

of the legislators, from the language of the statute

itself we find that they were evidently intending to

give every citizen equal rights in public places to

which they were accustomed to go, either for ac

commodation or amusement. The legislature did

not have in mind specially certain places which they

name and others of a similar or like kind, but the

object they had in view was the citizen. They in

tended that there should be no discrimination on ac

count of color or race to citizens who might apply at

public places for either accommodation or amuse

ment.

While the maxim insisted upon is a rule of

statutory construction which a court in construing

this statute should consider, yet we think that it

should not be permitted to override the clear inten

tion of the lawmakers as evidenced from the plain

reading of the statute itself, and we think that a pub

lic dancing pavilion comes under the provisions of

24

this statute, included in ‘ other place of accommoda

tion and amusement.’ ”

This statute is commonly called the Civil Rights Act,

and was originally enacted in 1894. We may find enlight

enment as to its object both in the preamble to the orig

inal enactment and the judicial expressions of Ohio courts

pertaining thereto. The preamble as found in the Re

vised Statutes, 4426-1-2, is as follows:

“ Whereas it is essential to just government that

we recognize and protect all men as equal before the

law; and that a democratic form of government

should mete out equal and exact justice to all, of

whatever nativity, race, color or persuasion, reli

gious or political; and it being an appropriate object

of legislation to enact great fundamental principles

into law, therefore, * # *”

and some of the pertinent expressions found in the cases

are as follows:

“ It will be noticed that the legislature declares

the purpose of these statutes by the preamble to be,

to enact a great fundamental principle into law * * *

It was without doubt the intention of the legislature

to enact into positive law what has come to be rec

ognized as justice, that the colored man shall not be

refused equal privileges with other people in these

public places * *

Johnson v. Humphrey, etc. Co. (1902), 14 C. D.

135.

‘ ‘ The statute in question does not prevent the pro

prietor of any place of public accommodation from

refusing to serve any person, who, by reason of his

disorderly conduct and habits, is objectionable to

him or his patrons; but in the exercise of such right

of refusal he must not discriminate against a man

solely on account of his race and color. We must

treat all citizens irrespective of color, race, precisely

25

alike * * *. The statute in question is based upon

the Fourteenth Amendment * * #. The inhibition

contained in the Fourteenth Amendment was in

tended to secure to a recently emancipated race all

the civil rights that the dominant race theretofore

had enjoyed.”

Fowler v. Benner (1912), 23 0. D. 59.

“ Turning now to the statute under which this

action is brought, and looking at the evident intent of

the legislators, from the language of the statute

itself we find that they were evidently intending to

give every citizen equal rights in public places to

which they were accustomed to go * * * the object

they had in view was the citizen. They intended that

there should be no discrimination on account of race

or color to citizens who might apply at public places

for either accommodation or amusement.”

Youngstown, etc. By. Co. v. Tokus, supra.

‘ ‘ Said sections were passed by our legislature not

for an imaginary, but a real purpose.”

Guy v. Tri-State Amusement Co., (1917), 7 0. A.

509.

“ Its policy and purpose are well known and the

courts have consistently administered it in the spirit

of its adoption and intent, which was to prevent dis

crimination in public enjoyments and privileges,

based on favoritism of race, color or other adven

titious differences among those entitled to be

served. ’ ’

Anderson v. State, (1918), 30 C. D. 510.

“ It is enough that this is the very thing which

the statute we are administering denounces and for

bids. There is sufficient history behind it—and in

deed in its presence—to admonish the courts why

and how it became necessary and commended its pro-

26

hibition to tbe law-making power, and to administer

it in the light of that history. Its purpose was to

contradict the pitiless affront to a being created in

the image of a common and impartial maker * * *.

It is not for the courts to argue for the wisdom of

the law they are sworn to administer in its integ

rity. But there is reason for reminding litigants

that the spirit of law should be observed in courts,

when elsewhere there is a general disposition to ig

nore and condemn it.”

Puritan Lunch Co. v. Forman, 35 C. D. 526.

In Young v. Pratt (1919), 11 Ohio App. 346, our own

Court of Appeals said that Sec. 12941, G. C. is “ unambig

uous.” The history and purpose of the statute are also

discussed in 7 Ohio Juris. 463, et seq., and especially at

page 469.

In Fowler v. Benner, supra, it was held that a place

of public accommodation means a place where the wants

and desires of those who frequent it may be supplied for

consideration. This Court believes that definition to be

sound and applicable to the instant case. Certainly there

is no difference in regarding the defendant’s store as a

place. It is equally clear that as a place offering wom

en’s apparel for sale it is within the meaning of the

statute. Accommodation is defined in Webster’s as being

whatever supplies a want or affords ease, refreshment or

convenience; or anything furnished which is desired or

needful. See 1 Corpus Juris 518.

The question remains whether defendant’s place of

business is a public place. On the allegations of the

petition admitted for the purposes of this demurrer, we

think there can be no serious question but that it is a

public place, open to all the people whose needs it may

satisfy for a consideration. In other words that it is no

27

different from any other place of business which offers

its wares to the general public, who is able or willing

to pay the price therefor.

Having in mind the declared object of the statute

and the spirit in which it has been consistently construed

by the courts of Ohio, we are of the opinion that the peti

tion states a cause of action.

In view of the wealth of Ohio authority on the sub

ject, we do not feel constrained to regard the citations

from other jurisdictions which are necessarily based upon

the particular statute in those jurisdictions. The case

of Denwell v. Foerster, 12 Nisi Prius (N. S.) 329, a case

decided by the Common Pleas Court of Franklin County,

has been cited to us. It was there held that a soda foun

tain was not within the meaning of the statute. The rea

soning employed in that case does not commend itself

to this Court.

Our attention has also been called to the case of

Keller v. Koerbes, 61 0. S. 388, where the Supreme Court

held that a place where intoxicating liquors was sold at

retail was not a place of public accommodation or amuse

ment. It is sufficient to say in connection with that case

that the court felt compelled to reach the conclusion it

did by reason of the then express state legislative policy

against the existence of such places at all. There is no

such counter-policy to be considered in this case. On

the contrary, the whole legislative policy of Ohio with

respect to discrimination against the citizens on the basis

of race or color is consistent with the conclusion the

court has reached in this case. Therefore, the demurrer

should be overruled.

L e w is D r u c k e r ,

Judge.

May 18, 1935.

.

■

;

-

■

'

-

'

’

.

’

'

.

■

■

-

.

ass

No. 26,162.

In the Supreme Court of Ohio

A ppe a l F rom

T h e C ourt op A ppe a l s of C uyahoga C o u n ty .

ELLEN SISSLE,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

VS.

HARVEY, INC.,

Defendant-Appellee.

BRIEF OF DEFENDANT-APPELLEE

OPPOSING MOTION TO CERTIFY.

Q u in n , H o rn in g & L aP o r te ,

900 National City Bank Building,

Cleveland, Ohio,

Attorneys for Defendant-Appellee.

T h e G a t e s L e g a l P u b l is h in g Co., Cl e v e l a n d , O h io

.

V \

:

B - v : ■ ■,>. ■ .;■'

;\ T -" - -"C , :VV • I?: :4v"'-/■.:-■■■'> • H ^g

’

S 'f - W 'v f S '

J r Jr J,

-

: -M^V

■ " ■ '4 .- 3 ^ : '

■

f f 0 * S 5

■f-s-:-'

;

>; --' ̂ r.-■:,. • ->,.\< '■ ' ~'

•,: ;f tfej

yX-Vi

IjJ

■

|f|!

Sfe

'- ' 7 ;.Vi“ >■ 4

■

- - .\ • "> \ - ■ ;^V! .

, . S ' ’? \ X < I

INDEX.

History of Case.............................................................. 1

Facts ................................................................................ 3

Civil Eights Statutes..................................................... 3

Grounds of Motion to Certify..................................... 5

Argument on the Law................................................. 5

Conclusion ...................................................................... 10

Appendix:

Court of Appeals Opinion. . .................................. 12

Authorities Cited.

Cecil vs. Green, 161 111. 264; 43 N. E. 1105.............. 9

Dartmouth College Case, 4 Wheat. 666...................... 7

Davis vs. Theatre, 17 C. C. (N. S.) 495..................... 4

Demvell vs. Forester, et al., 12 0. N. P. (N. S.) 329 7

Fargo vs. Meyers, 4 0, C. 275..................................... 4

■Goff vs. Savage, 122 Wash. 194; 210 Pac. 374.......... 8

Ohio General Code:

Section 12940 ........................................................ 3,6

Section 12941 ........................................................ 3

Ohio Jurisprudence, Vol. 7, Par. 2, Page 468.............. 7

Ohio Jurisprudence, Volume 7, Par. 26, Page 494. . . . 8

1 Thompson Corporation, Par. 22............................... 7

Throckmorton’s Edition of the Ohio General Code

Table of Contents................................................... 3

Youngstown Park & Falls Railway Company vs.

Tokus, etc., 4 Ohio Appeals 281..................... 2, 5,10

No. 26,162.

In the Supreme Court of Ohio

A p p e a l F rom

T he C o u rt op A ppe a l s op C uyahoga C o u n ty .

ELLEN SISSLE,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

vs.

HARVEY, INC.,

Defendant-Appellee.

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF DEFENDANT-APPELLEE.

The parties will he referred to as they appeared in

the Municipal Court of the City of Cleveland, wherein

Appellant was Plaintiff and Appellee was Defendant.

HISTORY OF CASE.

This case originated in the Municipal Court of Cleve

land, Appellant filed suit against Appellee for damages

alleging a violation of the Civil Eights Statute (Ohio

General Code Section 12940) in that Appellee, while op

erating a “ Women’s Wearing Apparel Shop” refused to

wait upon or serve Appellant. Appellee filed a Demurrer

to said Petition, which was overruled by Judge Lewis

Drucker, who wrote the Opinion cited on page 20 of Ap

pellant’s Brief.

The Appellee, excepting to said ruling, filed its An

swer and the case, in due course, came on for trial before

Judge Oscar Bell of said Municipal Court, a jury having

Italics and bold face emphasis throughout are ours.

2

been waived and resulted in a judgment being rendered

in favor of Appellant against Appellee in the sum of One

Hundred Dollars ($100.00) and the costs.

From said judgment Appellee appealed to the Court

of Appeals of Cuyahoga County and said Court reversed

the finding of the lower Court and entered a final judg

ment in favor of Appellee. It is by reason of such re

versal and final judgment that the case is now in this

Court on a Motion to Certify.

It was urged by Appellant in the Court of Appeals

that the decision of said Court in the case at bar was in

direct conflict with the decision in the case of Youngs

town Park and Falls Railway Company vs. ToJcus, etc.,

4 Ohio Appeals 281, and this alleged conflict is again

urged in Appellant’s Brief, although the Court of Ap

peals of Cuyahoga County in a clear and concise opinion

(See Appendix, page 12) distinguished the cases and

pointed out the absurdity of contending that a conflict

could exist between said cases, when the subject matter

of each was entirely different, namely, “ a public dance

hall” and “ a Women’s Wearing Apparel Shop.” How

ever, Appellant, being consistent as well as persistent,

reiterates this so-called conflict.

THE FACTS.

Insofar as this Motion to Certify is concerned the

facts may, to some extent, be conceded, namely, that the

Appellant was colored and of African descent and that

the Appellee owned and operated a retail store known as

a “ Women’s Wearing Apparel Shop” in the Terminal

Tower Building in Cleveland, Ohio.

CIVIL EIGHTS STATUTES.

Ohio General Code— Section 12940. Denial of

privileges at inns and other places by reason of

color. Whoever, being the proprietor or his employe,

keeper or manager of an inn, restaurant, eating-

house, barber-shop, public conveyance by land or

water, theatre or other place of public accommoda

tion and amusement, denies to a citizen, except for

reasons applicable alike to all citizens and regard

less of color or race, the full enjoyment of the accom

modations, advantages, facilities or privileges there

of, or, being a person who aides or incites the denial

thereof, shall be fined not less than fifty dollars nor

more than five hundred dollars or imprisoned not less

than thirty days nor more than ninety days, or both.

Ohio General Code— Section 12941. Further

penalty. Whoever violates the next preceding sec

tion shall also pay not less than fifty dollars nor more

than five hundred dollars to the person aggrieved

thereby to be recovered in any court of competent

jurisdiction in the county where such offense was

committed.

We will first consider the nature, character and con

tent of said Statutes as they exist on the Statute books

of this State.

The sections alleged in plaintiff’s petition, as the

foundation of this case, namely, General Code 12940 and

12941, are found in the following subdivision of the Ohio

General Code. (We are quoting verbatim from the Table

of Contents of the Throckmorton Edition of the Code):

“ Part Fourth: Penal

Title I Felonies and Misdemeanors

* * * #. . *

Chapter 10. Violations of Personal Eights 12940 to

12956-2.”

3

4

From the above, we find that when these sections

were enacted by the Legislature, they were intended to

be and are penal statutes.. This is apparent from the

Title and classification under which they are carried and

the further fact that one who violates said sections is

amenable to both a fine and imprisonment. The Courts

of this State, in addition to those of other states, have,

without exception, definitely held these Statutes to be

penal. We call attention to the following language used

by our own Court, to w it:

“ The Civil Rights Law imposing a forfeit of

$100.00 (now $500.00) and also a fine or imprison

ment on any person who violates it, is highly penal

and to be strictly construed * * # etc.”

Fargo vs. Meyers, 4 C. C. 275.

As further proof of the fact that said Statutes are

penal, we find that one who acts as an “ aider or abet

tor” is subject to prosecution the same as the principal

and if this is the law and the cases so hold, then un

questionably the Statute must be penal or there could

be no “ aiders or abettors.”

We cite the following case in support of the above

contention:

“ Aiding or inciting a denial of civil rights under

General Code 12940, is a distinct and separate offense

and one guilty of it is punishable, notwithstanding

he whom he aided or incited has been convicted of

the concomitant offense.”

Davis vs. Theatre, 17 C. C. (N. S.) 495.

Therefore, by reason of the interpretation placed on

said sections by our Courts, as well as the wording of

the Sections themselves, it is apparent that said Sec

tions are penal in fact as in form..

5

The courts universally hold that the Statute being a

penal Statute and in its very nature criminal must be

strictly construed. In the case of Schultz vs. Cambridge,

38 0. S. 659, the Court said “ where the act is made pun

ishable by fine and imprisonment, the words in which

the offense is defined and punishment prescribed must

be strictly construed whether they are found in the stat

ute, or in the ordinance or by-law. Any general words

following particular or specific words, must, ordinarily,

be confined to things of the same kind as those specified. ’ ’

GROUNDS OF MOTION TO CERTIFY.

After a careful study of Appellant’s Brief, we find

but two points raised for consideration of this Court:

First. That the decision rendered by the Court

of Appeals of Cuyahoga County in the case at bar,

is in direct conflict with the Youngstown Park and

Falls Railway Company vs. Tokus, etc., 4 Ohio Ap

peals 281.

Second. That this retail store or “ Women’s

Wearing Apparel Shop,” owned and operated by

Appellee, is a place of public accommodation within

the meaning of Section 12940 of the General Code

of Ohio.

ARGUMENT ON THE LAW.

We will discuss the above mentioned grounds in the

order named.

Appellant contends that there is a direct conflict be

tween the decision in the case at bar and the Youngstown

Railway Company vs. Tokus {supra), we fail to see either

a conflict or the slightest similarity between said cases.

In the Tokus case the Court held that a “ public danc

ing pavilion” is within the meaning of the term, “ or

other place of public accommodation and amusement ’ ’ as

6

used in Section 12940. In the case at bar the Court held

that “ this retail store” was not within the meaning of

said Statute. Surely nothing could be more dissimilar

than the operation of a “ public dance pavilion” and the

operation of “ a retail store.” We readily concur with

the Court’s finding in the Tokus case that a public dance

pavilion comes fairly and squarely within the exact lan

guage of the Civil Rights Statute since it is essentially

and actually a place of public amusement.

But to attempt, as Appellant does, to stretch said

decision to embrace a retail store is quite beyond any

legal comprehension.

We feel that the reasoning and conclusion, as set

forth in the Court of Appeals’ Opinion, distinguishes

these cases better than any effort on our part to amplify

said Court’s Opinion. Accordingly, we respectfully re

fer this Court to said Opinion as set forth in toto in the

Appendix hereto on page 12.

The second contention of Appellant is that “ this

retail store” is a place of public accommodation within

the meaning of Section 12940 of the General Code of

Ohio.

The business of defendant as alleged in plaintiff’s

Petition and as established by the evidence at the trial

was the operation, by the defendant, a private corpora

tion, of a “ Women’s Wearing Apparel Shop.” Clearly,

therefore, if defendant comes within the purview of the

above quoted section, it must be in the classification “ or

other place of public accommodation ”

The defendant in this case is a “ Private Corpora

tion,” which is defined by Bouvier as “ Private Corpo

rations are those which are created wholly or in part, for

purpose of private emolument. ’ ’

7

In the oft quoted Dartmouth College case (4 Wheat.

666), we find the following language used by the illustri

ous Mr. Justice Storey:

“ Another division of corporation is into private

and public. * * # Strictly speaking public corpora

tions are such only as are founded by the govern

ment for public purposes.”

We find that Judge Thompson in his learned work

(1 Thompson Corporation, Par. 22) considers that a

more practical conception would be to divide the corpo

rations into three classes: public-municipal corporations

to promote the public interests; corporations technically

private but of quasi public character, such as railroads,

inns, hotels, etc.; and corporations strictly private.

From the above, we urge that defendant herein did

not operate a place of “ public accommodation” which

would be a railroad, inn, hotel or such an establishment

as partook of the nature of a quasi public corporation,

defendant operated a private corporation for profit.

We find the following statement of the law in Vol.

7 of Ohio Jurisprudence, Par. 2, page 468:

“ A provision protecting the immunity of a per

son from discrimination because of his race or color

by the proprietor of a privately owned business, is

depriving the proprietor of the right to contract with

whomever he pleases.”

The outstanding authority in Ohio, which is to the

same effect, is the case of Denwell vs. Forester, et al.,

12 O. N. P. (N. S.) 329, wherein the Court held an action

for damages will not lie under the civil rights statute

for refusal to serve a colored man a glass of soda from

a soda fountain. The Court on page 322 pointed out the

reason for its holding and said:

8

“ The conclusion is that a soda fountain is not

within the meaning of this statute, and that the pro

prietor of such a place has the absolute right to de

cline to sell to white, black, German, Irish, Catholic

or Protestant or any class of persons which he may

choose to decline to serve, without giving rise to

any right of action.”

In the State of Washington, the Court in interpret

ing a similar statute said:

‘ ‘ Such a statute does not preclude the proprietor

of a drug store from refusing to sell a soft drink at

his soda fountain to a negro; the sale of soda water

not being a matter of ‘ public accommodation.’ ”

Goff vs. Savage, 210 Pac. 374; 122 Wash. 194.

We, therefore, urge that the sale of “ Women’s

Wearing Apparel” is not and cannot be construed as a

matter of “ public accommodation.”

We desire to quote a few words from that well rec

ognized authority Ohio Jurisprudence in Volume 7, Par.

26, page 494:

“ Retail stores are private businesses, not intend

ed to be included within the Civil Rights Statute.”

We further urge that the defendant in this case was

engaged in conducting a private business, organized as

a private corporation for the sole purpose of making a

profit. Defendant’s business was in no sense a “ public

accommodation” but purely a private venture in which

the public had no rights or interest and therefore, de

fendant had a perfect legal right to conduct its busi

ness in such a manner as it saw fit and owed no duty to

the public either for accommodation or service.

In conclusion we submit the defendant, who admit

tedly by plaintiff’s Amended Petition operated not an

inn, restaurant, eating house, barber shop, public con-

9

veyance by land or water, theatre or other place of pub

lic accommodation and amusement but on the contrary

a private business of selling WOMEN’S WEARING AP

PAREL, therefore defendant, even without invoking the

strict rule of interpretation required in the case of penal

statutes, could not be found to be operating a place with

in the terms defined in General Code 12940 and there

fore, could not legally be found guilty of violating said

section.

The case of Cecil vs. Green, 161 111. 265; 43 N. E.

1105, cited in Court of Appeals’ Opinion is not only a

case cited as an authority in every work dealing* with

the interpretation of the Civil Rights Statutes, but also

is a clear and comprehensive statement of the law per

taining to the liability created by said Statute and dis

tinguishing those amenable to the penalty therein pro

vided, we feel that our Brief would be incomplete with

out a quotation from said authority:

“ It is a clearly established rule of construction

that after an enumeration of certain places of busi

ness on which a duty is imposed, or a license re

quired, and the same statute then employs some gen

eral terms to embrace other cases, no other cases

will be included within the general term except those

of the same character or kind as specifically enumer

ated.”

‘ ‘ The personal liberty of an individual in his busi

ness transactions and his freedom from restrictions,

is a question of the utmost moment; and no con

struction can be adopted by which an individual

right of action will be included, as controlled within

a legislative enactment, unless clearly expressed in

such enactment, and certainly included within the

constitutional limitation on the power of the legis

lature. Nothing in this provision requires a physi

cian to attend a patient, a lawyer to accept a re-

10

tainer, a merchant to sell goods, a farmer to employ-

labor, unless of bis own volition, regardless of any

reason, whether expressed or not. The g-eneral pro

vision does not include the business of defendant

(drug store) nor is it included within the terms

specifically made. ’ ’

CONCLUSION.

In conclusion, we urge that the Youngstown Park

and Falls Railway Company vs. Tokus, 4 0. A. page 276,

was a case involving a public dance pavilion and as such

is clearly a place of public amusement and therefore,

comes squarely within the exact language of the Civil

Rights Statute. All the authorities cited in the Tokus

case {supra) as well as all of those contained in Ap

pellant’s Brief, deal with places of either public accom

modation or amusement. There is not a case cited cover

ing a private business establishment.

Nor, has Appellant even attempted to answer the old

and well established theory of law, pointed out in the

Court of Appeals’ Opinion, namely, the right given by

our Constitution to all persons engaged in a private busi

ness or enterprise to contract with whomsoever he

chooses on whatsoever terms he may make.

It is also our firm conviction that the general terms

used by the legislature in the Civil Rights Statute, relate

only to places of similar character and kind to those

specifically mentioned. Retail stores are neither men

tioned specifically nor can they be brought within the

provisions of said statutes as they now exist.

In our opinion the strongest argument that can be

advanced to show that the legislature when they enacted

the Civil Rights Statute did not intend it to be all em

bracing, is found in the fact that after the original Civil

Rights Statutes were enacted, the legislature found it

11

necessary to broaden the scope of said statutes by en

acting Section 6064-25 of the Ohio General Code under

the Liquor Control Act and likewise Section 9401 and

Section 12954 of the Ohio General Code, relating to com

panies engaged in the insurance business, imposing a

punishment for any one engaging in said business for any

discrimination. Clearly as pointed out in the Court of

Appeals’ Opinion, the enactment of these latter Stat

utes would be a mere tautological performance, if, as

Appellant contends, the original Statute was all embrac

ing.

We, therefore, respectfully submit that Appellant’s

Motion to Certify should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

Q u in n , H o rning & L aP o r te ,

Attorneys for Defendant-Appellee.

12

APPENDIX.

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS.

S tate of O h io , E ig h t h D is t r ic t ,

C uyahoga C o u n ty .

N o. 15,405.

HARVEY, INC.,

Plaintiff in Error,

vs.

ELLEN SISSLE,

Defendant in Error.

OPINION.

June 29th, 1936.

( E rror to t h e M u n ic ip a l C o u rt of Clev ela n d .)

L ie g h l e y , P.J.

The plaintiff Ellen Sissle recovered a judgment

against the defendant, Harvey, Inc., for the sum of One

Hundred Dollars based upon a claim that she was re

fused service in a store of the defendant in violation

of Section 12,940 General Code. This section, so far

as pertinent, reads as follows:

‘ ‘ D en ia l of P r iv il e g e s at I n n s and O t h e r P la ces

b y R eason of C olor. Whoever, being the proprietor

or his employee, keeper or manager of an inn, restau

rant, eating house, barber-shop, public conveyance

by land or water, theatre or other place of public

accommodation and amusement, denies to a citizen,

except for reasons applicable alike to all citizens and

regardless of color or race, the full enjoyment of the

accommodations, advantages, facilities or privileges

thereof, or, being a person who aides or incites the

denial thereof, * * *”

13

This ease was presented to us for review on error.

The plaintiff claims that this retail store maintained by

defendant to sell apparel for women is comprehended

within this Act. The defendant denies it. This is the is

sue upon which the case must be determined.

The question is whether or not the general language

contained in the Act “ or other place of public accom

modation and amusement” is limited in its application

to the particular words or particular activities thereto

fore mentioned and specified in the Act. It should be

noted that these specific words relate principally to

places maintained for lodging or providing food or pub

lic conveyance or theatres. Of course, any business by

whatever name of which any specific or particular word

or phrase used in the Act is definitive is controlled there

by. There is no specific mention in the Act of retail

stores or the professions or any of the many other occu

pations and trades in which the citizens of the State en

gage that are unlike and dissimilar to those specified.

It has long been a rule of statutory construction in

this State that whenever general words follow partic

ular words, the application of the general words must

be limited to things of the same kind and character as

those specified. The only exception to this rule is any

instance in which its application results in an apparent

limit or defeat of the legislative intent evidenced by the

language and apparent purpose of the Act itself.

If the legislative intent was general and all-inclusive

as claimed by counsel for plaintiff, it would have been a

very simple matter to have used general language only.

The fact that particular words and phrases were em

ployed and these particular activities thereby emphasized

rebuts any contention that the intent was general and

all-comprehensive. This Court would be legislating to

14

construe the general words following the particular in

the manner urged and would he doing so in defiance of

the well and long established rule of statutory construc

tion.

If the legislative intent was an all-embracing Act,

then that body engaged in a tautological performance in

writing Section 25 into the Liquor Control Act in 1933.

(Section 6064-25 G. C.) Likewise, when it wrote Sec

tion 9401 and Section 12954 General Code into the Stat

utes relating to any company engaged in the insurance

business imposing punishment for any discrimination.

For cases dealing with this subject of construction

in Ohio reference is made to Volume XI, Page’s Com

plete Ohio Digest, (last edition) page 642.

Also the following section under the title “ Civil

Rights” in Volume VII, Ohio Jurisprudence, pag*e 494,

Section 26:

“ R e ta il S to bes .— Retail stores are private busi

nesses, not intended to be included within the Civil

Rights Statute. A drug store is not included with

in the statute, although it has a soda fountain busi

ness, which is merely an adjunct to the drug busi

ness.”

The general law relating to this rule is stated and

summarized in Vol. V, Ruling Case Law, page 586, in

the following language:

“ And so where the law enumerates certain places

such as inns, eating houses, theatres, and public con

veyances, and concludes with a general clause cover

ing ‘ all other places of public accommodation and

amusement,’ entitling all persons to the full and

equal accommodations therein, it is clearly estab

lished as a rule of construction that if, after enumer

ating certain places of business on which a duty is

imposed or for which a license is required, the same

15

statute then employs some general term to embrace

other cases, no other cases will be included in the

general term except those of the same general char