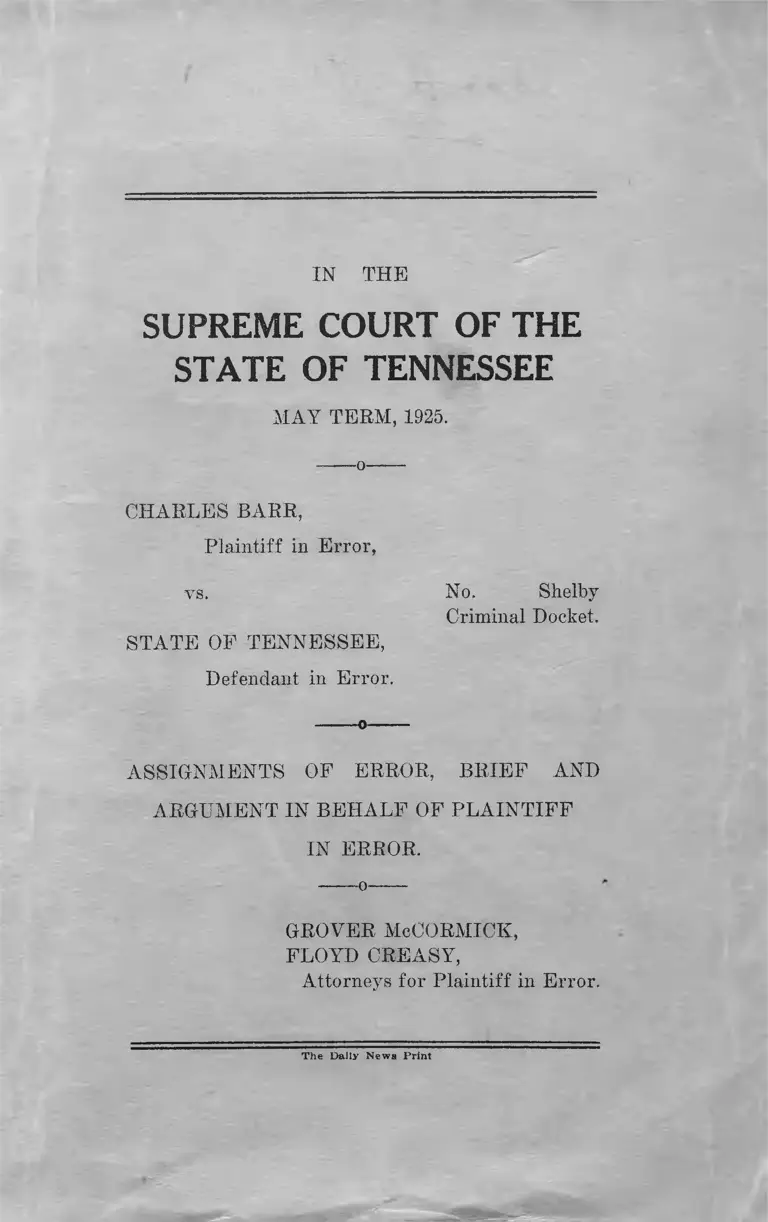

Barr v. Tennessee Assignments of Error, Brief and Argument in Behalf of Plaintiff in Error

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1925

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Barr v. Tennessee Assignments of Error, Brief and Argument in Behalf of Plaintiff in Error, 1925. 2d022784-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b47eac53-a281-4666-9a81-e7cd50fa48d5/barr-v-tennessee-assignments-of-error-brief-and-argument-in-behalf-of-plaintiff-in-error. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN T H E

SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OF TENNESSEEM A Y T E E M , 1925.----- 0----C H A R L E S B A R R ,Plaintiff in Error,vs.S T A T E OF T E N N E S S E E ,Defendant in Error.

-— ■— o-—A S S IG N M E N T S O F E R R O R , B R IE F AN D A R G U M E N T IN B E H A L F O F P L A IN T IF F IN ERR O R.------o------

g r o v e r McC o r m i c k ,F L O Y D C R E A S Y ,Attorneys for Plaintiff in Error.

No. Shelby Criminal Docket.

T he D ally N ew s Print

I N D E X . PageA SS IG N M E N T S O F E R R O R , B R IE F A N D A R G U M E N TIN B E H A L F OF T H E P L A IN T IF F IN E R R O R . . . . 3A SS IG N M E N T S OF E R R O R ................... 5B R IE F A N D A R G U M E N T ........................................................................ 9IN C O N C L U SIO N ............................................................................................. 144

IN T H ESUPREME COURT OF TENNESSEEM A Y TER M , 1925.------o------C H A R L E S B A R R ,Plaintiff in Error,vs. No. ShelbyCriminal Docket.ST A T E OF T E N N E S S E E ,Defendant in Error.------o------A S SIG N M E N T S OF E R R O R , B R IE F AND A R G U M E N T IN B E H A L F OF P L A IN T IF F IN ERR O R,----- o—-—M A Y IT P L E A S E T H E C O U R T :The facts of this case are briefly as follows:On the 25th day of Ju ly , 1924, the grand jury of Shelby County, Tennessee, returned an indictment in two counts against the plaintiff in error (who will be referred to hereafter as defendant) charging him with the offense of murder in the first degree upon the body of one W. 0. Spencer on the 23rd day of May, 1923.

4

In the first count of said indictment the defendant is charged with deliberate premeditated murder with malice and aforethought.In the second count of said indictment defendant is charged with murder while in the perpetration of a robbery.(Tr. 2-3).The killing is alleged to have occured on Highland Avenue, a public thoroughfare in Shelby County, running north and south, a few miles east of the City of Memphis, about three hundred yards south of where said thoroughfare crosses the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis Railroad tracks..(Tr. 34 and 36).The defendant was arraigned in Division 1 of the Criminal Court of Shelby County, Tennessee, on the 29th day of Ju ly , 1924. A plea of not guilty was entered of record and defendant was thereafter, to-wit, on the 14th day of October, 1924, put upon his trial before the Judge of Division 1 of the Criminal Court of said County and a jury.(Tr. 5 and 9).The jury returned a verdict on the 27th day of October, 1924, finding the defendant guilty of murder in the first degree, and fixing his punishment at death by electrocution. '' Defendant filed a written motion for a new trial within the time prescribed by law. On the 22nd day of November, 1924, defendant,

0

through his counsel of record argued his motion for a new trial which motion was by the Court overruled. A motion in arrest of judgment was then made by defendant upon the same grounds as those appearing in the written motion for a new trial. Said motion was likewise overruled by the Court. Defendant then and there excepted to the action of the Court, in overruling his motion for a new trial, and his motion in arrest of judgment, and prayed an appeal in the nature of a writ of error to this Honorable Court, which appeal was granted and perfected within the time prescribed by law.(Tr. 20 and 22).Defendant is now before this Honorable Court seeking a reversal of the judgment and sentence imposed against him by the Criminal Court of Shelby County, Tennessee.

A SSIG N M E N T S OF ERR O R.I.The Court erred in admitting as evidence before the jury the alleged statement or confession of defendant, over the objection and exception of defendant, before the State proved by competent and credible evidence, that said alleged statement or confession, was freely and voluntarily made, and in placing on defendant the burden of proving said alleged statement or confession to be involuntary.

6

IT.The Court erred in overruling defendant’s motion for a new trial on the sixth ground and reason contained therein which is in the following language:‘ ‘ The Court erred in allowing and admitting as evidence before the jury in this cause confessions, both oral and written, alleged to have been made by Charles Barr while in the custody of the police officers of the City of Memphis for the following reasons:1. Because, according to the testimony of the police officers and others testifying in behalf of the State on preliminary examination, upon the questions of admissibility of said statements, both oral and written, said statements were not given and made by Charles Barr freely and voluntarily, but were made and induced by threats of violence, promises of reward, promise of immunity and while, in a weakened, broken and groggy physical condition, and that said admissions were secured by said police officers by continued questioning of Charles Barr against his will and over his protest and by the breaking of his spirit.That these alleged admissions and confessions were not made freely and voluntarily by Charles Barr is further shown by evidence introduced on preliminary examination! in his own behalf, as well as the evdience introduced in behalf of the State.2. Because said alleged confessions, both oral and written were secured from the defendant, Charles Barr, by the police authorities of

the City of Memphis in violation of his rights inuring to him under the constitution of the State of Tennessee and under the constitution of the United States. He was denied by said police authorities the right of counsel. He was not informed that he had a right to be represented by counsel. He was not informed by said police authorities that he did not have to make a statement unless he voluntarily desired to do so. He was not informed by said police authorities of the crime he was charged with. He was not informed that any statement or confession made by him could and would be used against him in a trial of any offense with which he might be charged.3 That said alleged confession was secured from Charles Barr by the police officers of the City of Memphis by duress and by improper and illegal means in violation of his constitutional rights under the constitution of the United States and the constitution of the State of Tennessee.” II I .The Court erred in . overruling defendant’s motion for a new trial on the seventh ground and reason contained therein, which is in the following language:“ Defendant herein should be granted a new trial upon the further ground that over the defendant’s objection the Court allowed to be introduced before the jury at the hearing of this cause an unidentified ring alleged to have been taken from the finger of a certain Mrs. Ruth Mcllwain Tucker, who was murdered with

8

her escort, Mr. Duncan Waller, in Shelby County, Tennessee, near the little town of Ber- clair.This was highly prejudicial to the rights of the defendant in the trial of this cause, wherein he was charged with the murder of W. 0. Spencer and was error on the part of the Court in allowing said incompetent evidence to be presented to the jury trying the defendant.The defendant should be granted a new trial in this cause for the further reason that the Court erred in allowing the introduction of an alleged confession on the part of Charles Barr over the protest and objection of his counsel to the effect that he had murdered a certain Mrs. E.uth Mcllwain Tucker and Mr. Duncan Waller in Shleby County, Tennessee, near the village of Berclair in January, 1922, and testimony of other witnesses to certain alleged facts relative to the murder of said Mrs. Tucker and Mr. Waller.This evidence was clearly incompetent and highly prejudicial to the rights of this defendant because it was evidence given relative to another separate, distinct and substantive offense, or crime and had no connection or bearing on the charge for which Charley Barr, defendant herein, was being tried in this cause. In other words, it was incompetent. A ll of the evidence introduced over the protest and objection of defendant’s counsel relative to the murder of the said Ruth Mcllwain Tucker and Duncan Waller was incompetent in this case and the Court erred in allowing its introduction in this cause, and its presentation to the jury trying Charley Barr in this cause.

9

All evidence introduced by the State with . reference to the murder of Mrs. Tucker and Duncan Waller was in the nature of alleged confessions made by the defendant, Charles Barr, to the police authorities of the City of Memphis. These statements and alleged confessions were not made by Charles Barr voluntarily but were induced and secured from him at the same time and in the same manner that the police authorities secured from him the alleged confession of the murder of W. 0. Spencer. The said testimony was incompetent for this additional reason.”

I V .The Court erred in overruling defendant’s motion for a new trial, on the ground that the evidence introduced in this cause, preponderates in favor of the innocence of the accused and against his guilt, and that the verdict of the jury is not supported by competent and credible evidence.

B R IE F AND A R G U M E N T .The first two assignments of error go to the admissibility in evidence before the jury of defendant’s statement or confession and for convenience, will be treated as one general assignment of error.Before going fully into the facts, and at the outset, we desire to call the attention of the Court to just what transpired on the part of the State and

10

what testimony it introduced to show that this confession was given freely and voluntarily by Charley Barr. After the Court reads this testimony which will be quoted below, it will at once be driven to the opinion that the Court below promptly, and without allowing discussion, forced upon the defendant the burden of showing his statement or confession to have been involuntarily made to the officers. This was clearly an error on the part of the Court, as was held in the Williamson and Platt case.The following is what transpired :

R ECO R D P A C E 131-134.Q. “ Now, When Barr was brougt to the police station you say that was on the 17th, Thursday!A . Yes sir.Q. In the neighborhood of between 1 and 2 o ’clock in the afternoon?A . Yes sir.Q. I will ask you if you had a conversation with him at that time?A . I did.Q. A t that time did he make any statement to you with reference to either the pistol or the watch?A . He made a statement with reference to both.

11

Q. Who was present at the conversation?A. I would not be positive; possibly the arresting officers were all in there, but I don’t remember—I didn’t pay that much attention to it. He was in the room. There was some of them in there; I would not be positive.Q. Was the wife of Charles Barr, Luada Barr present?A . I think she vTas General; I would not say positively about that; I know she was brought in in the meantime.Q. What statement, if any, did he make to you with reference to the pistol and watch?MB. M cCO R M ICK : I object to that, may it plase the Court. Object to any statement made to Chief of Detectives until it is shown here nowr just the circumstances under which the statement was made, or any other statement.T H E C O U R T : Any statement he freely and voluntarily made.Q. This was Thursday afternoon between 1 and 2 o ’clock. I will ask you if the statement he made to you with reference to the watch or the pistol, was free and voluntarily?A . It was.Q. I will ask you if any promise of reward was made to him of any offer of immunity of any kind?A . There wras not.

Q. Was he threatened or abused in any way?A . He was not.Q. Ju st state what he said to you Inspector with reference to the watch and pistol?MR. M cC O R M IC K : May it please the Court, I object here. It has been stated all along in this lawsuit—T H E CO U R T : Ju st a moment, Mr. McCormick. Do you want to hold a preliminary examination in the presence of the jury?MR. M cCO R M ICK : I want to make this statement—T H E CO U R T : You have a right, Mr. McCormick to—MR. M cCO R M ICK : I make objection upon this ground. I want to state my ground for making my objection now and it will not be prejudicial to the rights of anybody. It might be necessary for the jury to go out—T H E C O U R T : I will send them out.Thereupon the jury was excused, and the following proceedings were had in the absence of the jury:MR. M cCO R M ICK : My objection—my grounds of the objection is this: That during this whole proceeding, and during the examination of the veniremen and the jury, it has been

13

stated here a written confession or written statement would he introduced. And it is perfectly obvious that a written statement on the part of this defendant is in existence and that the statement bearing upon this issue of Charley B arr’s connection with this matter, is in writing and it has been so admitted and I object to any oral statement alleged to have been made by Charley Barr, this defendant, to any police officer, except this written confession.T H E CO U R T: Overruled.MR. M cCO R M ICK : Note an exception.T H E C O U R T : I f you desire to hold a preliminary examination as to whether it was freely and voluntarily made without hope of reward, you may do so by him or any other witness you may wish or see fit.MR. C R E A S Y : May it please the Court, I want to add, as a further ground to the introduction at this time of any statement alleged to have been made by the defendant, that the state has not shown by any evidence that it was freely and voluntarily made.T H E C O U R T : He asked the Inspector and he said it was.MR. C R E A S Y : It is not evidence, but simply a conclusion of the inspector, that it was freely and voluntarily obtained. I want to ask that the circumstances surrounding the alleged taking of this confession, be made known to the Court so that the Court may be the judge

14

as to whether or not the confession was freely and voluntarily made.GEN . S H E A : That is the question I asked and he objected to it.MR. M cC O R M IC K : We might as well go through the whole routine now; and that applies to the confession that will evidently be produced later on. Might as well go through the whole routine right now.GEN . M cL A IN : The statement was made at different times.T H E CO U R T : Go through the whole examination and see whether it was freely made.MR. M cC O R M IC K : I think we can do that and get through with it at one time.T H E C O U R T : Go ahead you gentlemen.G E N . S H E A : The statement made the first day and the second day—they are separate transactions.T H E CO U R T : L et’s ’ go into all of them and save time, right now.MR. M cC O R M IC K : I think so,—oral, written and everything else.T H E C O U R T : Go ahead with your examination.G E N . S H E A : He said it was freely and voluntarily made.

15

T H E C O U R T : Now is the time to see whether it was freely and voluntarily made.GEN . S H E A : We pass him to you.T H E C O U R T : It is up to you gentlemen to go through with the examination as you see fit. It is now time for lunch and we will adjourn until 2 P. M .”Only one other witness was introduced in chief by the State to show that this was a voluntary statement. This witness was Judge Clifford Davis, presiding Judge of the City'Court at Memphis.A a matter of fact, Judge Davis knew nothing about how this confession was obtained or the means used, or the promises or threats made to secure it. It is admitted and testified to by all witnesses that Charley Earr made his oral confession about 8 o ’clock on Saturday night, Ju ly 19th. The writing up of the confessions and the securing of Charley B arr’s signature are of no significance, and was merely routine.Judge Davis did not get to the police station on this night until after 10 o ’clock, and therefore, he is out of this matter so far as knowledge of the manner in which this confession was secured is . concerned.We quote the testimony of Judge Davis, Record page 184, as follows:

in

“ Q. What time on Saturday night did you get down to the Police Station!A. Oh, I think—if I recall it, I left you on the corner of Monroe and Main, it was a little after 10. I came on ahead of you to the Police Station—you came on up to the police station— yes, I recall I came ahead of you.”So Judge Davis knows nothing of the matter and we dismiss him.These are the only two witnesses introduced by the State and by whom it is contended the State carried the burden of showing these confessions to have been voluntarily made by Charley Barr.As a matter of fact there is no evidence in this record that this confession was voluntarily made.The Court, held in the Williamson and Flatt case, decided hM opinion by his Honor, JusticeMcKinney, on page 10 of said opinion, as follows:“ Upon an analysis of the State’s evidence, we find no testimony tending to show that this confession was freely and voluntarily made, and the burden was upon the State to show this. The only evidence upon this question are the statements of the officers, Eagan and Patton, that the confession was made voluntarily, which is a mere conclusion, as they testified to no facts and circumstances as a basis for such conclusion.We submit, therefore, that the State introduced

V

17

no testimony to show that this confession was a voluntary one on the part of Charley Barr and the Court committed an egregious and a reversible error in placing the burden upon the defendant, Charley Barr, to show that this confession was not forced from him.Charley Barr testified that Chief Griffin struck him, beat him, and abused him, and also testified that a police officer by the name of Lee Quianthy was the official who constantly abused him and beat him worse than any other officer who ever had him in charge.Lee Quianthy did not even take the stand on the question as to whether or not this confession was a voluntary one, and he was not called on to deny that he struck, abused, beat and mistreated Charley Barr, as he testified that he did.This brings ns to a discussion of all the facts, so that the Court may determine whether said alleged confession or statement was properly admitted as evidence before the jury.It is conclusively shown by the evidence and undisputed by the defendant that on the 23rd day of May, 1923, at about 11:3Q P. M., W. (). Spencer was shot and killed on Highland Avenue in Shelby County, Tennessee.(Tr. 29).The corpus delecti was therefore conclusively

18

proven, but by evidence that established nothing as to who the guilty person or persons were. The State relied solely upon the alleged confession or statement of defendant, and circumstantial evidence, to fix guilt upon him.It is the insistence of the State of Tennessee that a short time prior to the arrest of defendant, Lou Ada Barr, defendant’s estranged wife, was arrested and carried to the Police Station of the City of Memphis and questioned regarding a certain wrist watch which she had pawned at a pawn shop in the City of Memphis; that Lou Ada Barr made a writ ten statement in which she said the watch was given to her by defendant. Lou Ada Barr was not introduced as a witness in this case.(Tr. 129-130).Defendant was then arrested upon this evidence or suspicion and brought to the Police Station of the City of Memphis on Ju ly 17, 1924, at about 1 o ’clock P. M. (Tr. 188)It was at that time that Inspector W. T. Griffin, Chief of Detectives of the Memphis Police Department, and his men started their work of securing from defendant a free, voluntary and deliberate statement or confession, which work lasted fifty- nine (59) hours. At the end of said time and in the dead of night defendant signed the statement or confession introduced in evidence before the Jury.Tr. 357-398)

19

What took place in the office of Inspector Grifffin during that ordeal is thus described by defendant on direct examination in the absence of the jury.Beginning on page 188 of the transcript:“ Q. Who arrested you, Charley, if you know ?.A . Four detectives, at least three, I do not remember their names.Q. Where did they take you IfA . To the Police Station.Q. What part of the Police Station did they take you!A . Up in the front part, brought me in the back and come up in the front.Q. In whose office did you go!A . Chief Griffin.Q. When Chief Griffin came, what did he say to you?A . He asked me had I ever given my wife a wrist watch.Q. What did you tell him?A . Told him yes sir.Q. What else did he ask you? ?A . Well, he asked me that—he stayed on that one thing; asked where did I get it a t ; and lots of other things about it.

20

Q. Had he at this time told you that you were being brought to the Police Station in connection with the murder of a man named Obe Spencer?A . No, sir.Q. What did you tell him about the wrist watch ?A . Told him I had gotten it from a man named Manuel Williams, a policy writer. I had seen him several times; I didn’t know him personally ; 1 didn’t know where he lived at.Q. What did he say when you told him you had gotten the watch from Manuel Williams!A . Said that he would take that under consideration and find Manuel W illiamsQ. Did he find Manuel Williams!A. No, sir.Q. What else did you tell him, if anything, about other articles you had gotten from Manuel Williams?A . He began to state so much, I began to tell him what I had got from him and when.Q. Did he come back and say anything more to you about Manuel Williams? ?A . He said that he could not find a negro by that name and that I was not telling him the truth.Q. How did Inspector Griffin treat you when he said you were not telling the truth.

21

A . Well, he didn’t do anything to me himself, but his men struck me over the head and said that they were going to have the truth out of me.Q. Did Chief Griffin ever hit you, Charley!A. Yes, sir.Q. How many times?A . I could not recall how many times he hit me; he hit me quite a number of times, but not then.Q. Did Chief Griffin strike you before you came over here to the Court House that day in what we call the habeas corpus trial before Judge Guthrie?A . Yes, sir.Q. You say his men struck you. Can you tell the Court—can you describe the men that struck you?A . Well, I know one of them; I don’t know his name, but when I see him; he is very interested in it, and he is—Q. Very what?A . Very interested in it; and was always with me at the time; kind of a red nose man; and another big one had on a light suit, larger than he is; I don’t know the name of that one; I did know their names but I done forgotten them.Q. What did they strike you with?

22

A . Well, they got a little club looking thing, I guess so long—a little holder strap on it; that is what he struck me with at fir.it- Then the other man had something like a hose pipe, looked like a rubber hose.Q. What did they say to you when striking you.A . Ju st said I was telling a lie, and that they were going to have the truth out of me; that I should not sit up in the office and tell a lie like that.Q. What lie did they say you told? ?A . They said I said I got that from a strange negro; and they knew where I gotten it from.Q. Where did they say you had gotten it?A . They said then my wife said I got it from Mr. Bailer.Q. What did you say to that? ?A . As they began to strike me I just went on and said like they said, yes.Q. In other words, when they struck you those number of times, and said your wife said you get the watch from Mr. Bailer you went on and said what they wanted you to say?A . Yes, sir; I thought that was best to tell that to save my head, and I went on with them.Q. When did they first accuse you—tell you in the Police Station you were being charged with having killed Mr. Obe Spencer?

23

A . Well, as near as I can get at it that was Friday morning.Q. Friday morning?A . Yes, sir.Q. What was the occasion—who told you?A . Chief Griffin told me.Q. You were arrested Thursday afternoon?A . Yes, sir.Q. And it was On Friday morning, and what did he tell you?A . Well, he said that—told me he knowed where I got the watch; he said a woman was killed and the watch was—a man was killed and the watch was snatched off the woman’s arm and I was the man that did it.Q. Had you ever heard of Mr. Obe Spencer in your life before that time?A . No sir.Q. How long did they talk to you on the first afternoon that you were in the Police Station—taken down there. How long did they talk to you, if you know?A . They talked to me until night.Q. Talked to you until night?A . Yes, sir.Q. Then where did they take you?

24

A . Well, they had asked me who was the negro Charley Hays—got him mixed up witli me somehow or other I think—they asked me who he was. I told them I didn’t know. They struck me then for saying that, because they said I did know. I told them I didn’t know.Q. Which one of them struck you!A . Either M r .----- one of the two I told youabout.Q. The big man with the red nose?A . Yes, sir; the man with the light suit— they were the ones there with me that evening. Chief Griffin was in and out.Q. What was there about this man Hayes?A. They said I knowed him; I said I did not; and they struck me and they said he used to work for Mr. Dick—W. H. Dick. I used to work for Mr. Dick there, and they found out through him that he was name Charley. Somehow or other they thought that I and him was friends and I did know him. I didn’t know him by that name. I knew him by the name of Eska May.Q. Charley Hays and Eska May is the same negro; is that right?A. Yes, sir.Q. How was his name brought up; who brought it up?A . They brought it u p ; asked me if I know Charley Hays.

25

Q. Did you see Charley Hays at any time— did they bring him down there?A . Yes, sir; they brought him down there that night.Q. What did they have to say when they brought him in?A. They said the negro said he didn’t know anything about it.Q. Well, had yon told them that you had bought this stuff from Charley Hays or Eska May—or whatever you call him?A . No, sir; not at that time.Q. How long did they talk to you on Thursday night?A. Well, they talked to me until----- theytalked to me and whipped me until they got me to say that I got the stuff from Charley Hays.Q. You did tell them you got the stuff from Charley Hays?A . Yes, sir; after they whipped me and beat me.Q. And then how long did they talk to you that night?A . I would say until about 7 o ’clock; it was getting dark.Q. That was in the afternoon; the morning or night from 7 o ’ ’clock on?A . Before they started to talk they went

26

out in an automobile out somewhere and hunted Charley Hays.Q. Did they talk to you ?A . Yes, sir.Q. Take you along? ?A . Yes, sir.Q. That was Thursday night?A . Thursday night.Q. Where did you go?A . Went out on Linden Avenue; some place that he worked out there—over there back of Bender’s Garage.Q. What did they say to you while driving around ?A . They were saying we are going to find the negro and get the truth out of you or him one or kill both of you.Q. Did you come back to the Police Station then?A . Yes, sir; came back to the Police Station.Q. Did they talk to you any more during Thursday night?A . Yes, sir; talked to me clean until they got him.Q. How much sleep did you get on Thursday night?

27

A . Well, I don’t know as I got any. They talked to me all the time that night until after they got him, and when they got him they put me in. I would say I was in about an hour or two hours may be, I don’t know exactly; but I didn’t go to sleep at that time. Well, after they got there with him then they brought me back out and brought me before him, and asked me did I get the watch from him; and I told them yes sir.Q. Why did you tell them yes sir?A . Because I was afraid they were going to beat me some more.Q. Now, on Friday, did they talk to you on Friday?A . Yes, sir; from the time they left me— from the time I told them I gotten it from him, they talked to me from then on until the next morning.Q. On Friday afternoon or night, where did you go or where did they take you ?A . Well, we went out on Highland Avenue.Q. Out on Highland Avenue?A . Yes, sir.Q. What did they tell you going out Highland Avenue; where did they tell you they were taking you to?A . Told me they were taking me out where the man was killed.Q. For what purpose?

28

A . I f I didn’t own up to it and say. I did it that they were going to tie me behind an automobile and let those people kill me. Said the newspaper reporters had gotten it out that they had the right man and the people were out there waiting, and that when I was going out there they were taking me out there to kill me.Q. What did they say to you?A . They said, well just say you did that and we will not take you out there.Q. What did you tell them then?A . I didn’t tell them I did it; I told them I -would talk to them when I had gotten back.Q. What, if anything, did they put on your neck ?A . They had a collar; said that it was the dead man’s collar and put it around my neck and asked me didn’t I feel the man choking me; I told them no sir, I didn’t feel anything.Q. Then what did they say?A . They said you are the man, at least the newspaper reporters got it out you are the man if you are not. They said if you tell us you did this we will protect you. I f you don’t tell us, those people out there are going to kill you.Q. Did you have the collar around your neck at the time?A . Yes, sir.Q. What did you tell them then?

29

A . I just stuck out to it I didn’t do it; told them I didn’t do it.Q. What did they promise you, if anything, if you said you did do it?A . They promised me that if I would tell them I did it they would come into court with me and enter a plea—it was pointed out to me where they had had men worse than I, and asked did I remember and I said yes, and they said they would come in with me to the court and I would have a chance to save my life, if I did not I didn’t have a chance to save my life.Q. Did you confess?A . No, sir; not then.Q. I mean when you got back to the Police Station ?A . Yes, sir.Q. You told them out on Highland Avenue if they would not take you out and let them kill you, but bring you back to the Police Station that you would tell them that you did it?A . Yes, sir.Q. And that you would tell them anything they wanted you to tell them?A . Yes, sir.Q. And you did that did you?A . Yes, sir.

30

Q. That was Friday night about 8 o ’clock!A . I would say 8 or 9 o ’clock—somewhere along there.Q. About 8 or 9 o ’clock?A . Yes, sir.Q. And that is when you told them that you did it?A . Yes, sir.Q. Now then, these written papers here, did you read those papers over before you signed them?A . No, sir.Q. Who gave them to you?A . Well, they were not give to me, they were laying on the table.Q. What was said?A . A black sheet of paper over them, and I was told by the Chief for me to sign it, just to sign my name to them; that it was just a statement from me—‘your wife has signed and Eska May has signed, and everybody else has signed, why don’t you want to sign?” That is all kept from Friday night until Saturday night—the signing, that was all; I just would not sign my name to them.Q. You would not sign your name to the papers?A . No, sir.

31

Q. During the entire time you were over there at the Police Station, Charley, how much sleep did you get or were you allowed to get?A . Well, I slept Friday night from about say 6 o ’clock until the time they taken me out on Highland; they said I slept an hour; it, seems like about 20 minutes. Saturday night and Sunday morning they said at, 1 :30.Q. You mean that is all the sleep you got?A . Yes, sir.Q. During the entire time?A . Yes, sir; and they brought me up there Thursday.Q. Yes.A . They put me in Thursday night; I don’t know how long they were talking to Eska May. Well, I didn’t go to sleep then. Well, they got me out at that time and kept me from then until Saturday and didn’t allow me to go back in the prison from Thursday night until Saturday night.Q. _ Do you mean they kept you in Chief G riffin ’s office from Thursday night on until Saturday at noon?A . Yes, sir.Q. With the exception of two hours on Friday night you slept.A . Well, I went out on Highland Friday night, too; except that and Friday in the day; we went over on Madison, 62 Madison.

32

Q. Did you or not sleep or try to sleep in the chair you were sitting in in Chief G riffin ’s office?A . Yes, sir! I tried to at times, and every time I would go to sleep would be somebody woke me up some way or other.Q. Did they or not keep a detective in your presence from the time you were arrested until you made this confession?A . Yes, sir.Q. They struck you when you tried to sleep ?A . Yes, sir.Q. How?A . Say for instance, just like I would be leaning over like that; they would take their fist and strike me and raise me up like that; may be a kind of punch of some kind or hit on the head.Q. Did they give you any water?A . Well, Saturday morning they gave me water.Q. Saturday morning?A . Yes, sir.Q. Did they give you anything to eat?A . No, sir.Q. They did not?A . No, sir.

33

Q. Was it Saturday when they gave you water to drink or after that day?A . Yes, sir.Q. When did they give you food on Saturday ?A . Didn’t give me any until Saturday night, after I had signed my name.Q. Is that when you say Mr. Quianthy got you the eggs and ham?A . Yes, sir.Q. Was that the first food you had had?A . The first food I had had since Thursday morning when I had eaten my breakfast.Q. What, if anything, did they tell you about allowing you to stay with your wife if you would confess and sign the papers?A . Well, they said they would allow me a good opportunity—better than ever allowed anybody else that had been in the Police Station—they would allow me to go up and stay with my wife and give me a good supper.A . Yes, sir; if I would sign those papers.A . Yes, sir; if I would hsign those papers.MR. M cCO R M ICK : Take the witness.”Defendant further testified on cross examination in the absence of the jury, with reference to what happened in the office of Inspector Griffin. Beginning on page 212 of the transcript.

Q. You can count pretty well, can’t you?A . Yes, sir.Q. How many times did they hit you with that black jack and that hose pipe?A . I could not tell you to save my life ; they hit me a many a time with it.Q. Hit you many a time with it?A . Yes, sir. I could not count them to save my life.Q. Where did they hit you?A . Over the head, the shoulders, my arm here was sore from hitting me over the shoulders.Q. Would they hit you over the head, too?A . You put your hand up—Q. Ju st answer what part of the head they hit you.A . One of the places I could tell about them hitting, because one of the places having a knot raised on it on the back of the head. My head was sore all over.Q. They hit you all over the head then?A . Yes, sir.Q They hit you so many times that you could not give us an estimate of it, is that correct ?A . No, sir, not to save my life.

35

Q. Y ou understand what I mean when I say estimate?A . Yes, sir.Q. You understand it?A . Yes, sir.Q. Charley, how many people were in the room when you made this last statement, this Saturday night?A . I could not tell you.Q. Was there a whole lot of people or not?A . I don’t know, sir; I was so sleepy and hungry and tired I really don’t know.Q. Do you remember Inspector Griffin asking you a question?A. The questions ?Q. Y e s; this gentleman right here, asking you questions that night?A . What you mean by questions—he asked me one thousand questions.T H E C O U R T : I want to ask a question. Can you read?A . Yes, sir.T H E C O U R T : Why did you sign up a statement? Did you read it?A . No, sir.T H E C O U R T : Did you know what was in ' them?

36

A . No, sir; I didn’t read any more, they said it was a statement I had made.T H E C O U R T : What statement did you make ?A . I told them I did.T H E CO U R T : Did what?A . K ill people.T H E CO U R T : You knew what you were signing then?A . No, sir; I didn’t know what I was signing of that sheet of paper over it. They said everything I said while I was up there; the sheet of paper come down to here—sheet of blank paper, right down to there, and said sign your name. That is the way it was.T H E C O U R T : That is all.MR. M cCO R M ICK : Come down, Charley.G-EN. S H E A : Let him get back there a minute.Q. Charley, this was about Ju ly 17, 18 and 19, was it not when you were at the station house there?A . Yes, sir.Q. Was the weather hot?A . Yes, sir; very hot.Q. It was very hot?

37

A . Yes, sir.Q- You were taken to Inspector G riffin ’s office; that is where you say you were questioned. That office is right along Adams Street is it not on the Adams Street entrance!A . Yes, sir; the first office.Q. It is on Adams Street; the entrance— front windows and you can look out on Adams Street?A . Yes, sir.Q. And there are windows on the other side where you can look out on the fire station is there not?A . Yes, sir.Q. The windows were open?A . Yes, sir.Q. And that is where you were beaten and struck?A . Yes, sir; right in that office.Q. Did you see all those firemen sitting out there?A . Well, when I was up there at night, when anything like that would arise I want to tell you they would pull the shades down.Q. Pull the shades down?A . Yes, sir.Q. What did they do in the day time?

38

A . Kept the door locked and kept everybody out.Defendant further testified before the jury in reference to his arrest as follows:Beginning on page 580 of the transcript:“ Q. Charley, when were you arrested?A. Ju ly 17 th, 1924.Q. What day of the week was that?A . Thursday.Q. What time of day were you arrested, and where?A. About some time between 12 o ’clock out at Mrs. Van Fossan’s house.Q. Who arrested you?A . Three detectives; I don’t just remember their names.Q. What did they say to you when they walked up to you?A . Well, I drove under the driveway and I noticed a little Ford car sitting out on the Parkway; I didn’t know the man in it. I came under the driveway as I usually do, and drove on into the garage and taken my bundles out of the car in one hand and there was a piece of paper laying in the driveway and I picked that up because I knew Mrs. Van Fossan would come and see it; and I always have to do things like that before she told me. As I picked the

39

paper up, there was some hedge comes up beside the driveway; and I stepped outside the hedge to throw the paper on a pile of trash out there where we burn it, and as I came out of the driveway I saw them coming in, and I didn’t pay any attention; just thought they were insurance men or something; I didn’t know what their business was. So I went out to throw this paper, and by the time I had gotten back to the hedge,—it may be possible I had gotten back to the hedge—they all three was running up and pulled out their pistols on me and said: ‘ Don’t run and throw up your hands.’ And I had the bundle in one hand, and threw up the one hand, and I told them I wasn’t going to run. So they brought me on back, I asked if I could put my bundle back and they said yes.Q. What did they say they wanted with you ?A . One said, I am an officer and I want you. I asked him what did he want. He said, ‘ The Chief wanted to talk with me.’ I asked him if he knowed what the Chief wanted. He said no, he did not. Well, by that time I guess the Ford drove in the driveway and they put me in it.Q. Did they go up to your room!A . No, sir; not then.Q. Not then!A . No, sir.Q. Did you go up to your room?

40

A . No, sir.Q. Where did yon go from there!A . Came on to the police station.Q. Do you know whether or not they got a pistol out of your room or not!A . Yes, they did.Q. When, if you know?A. Must have gotten it before I got there, because the room was open, and the cook was there and I understand that they had asked her a lot of questions concerning me; but I didn’t- know it at that time.Q. But they didn’t go up to your room and take you up to your room at that time?A . No, sir.Q. When you got to the Police Station did they have this pistol with them?A . Yes, sir; they had it but I didn’t see it.Q. Well, what did they say to you coming to town from Mr. Van Fossan’s home to the Police Station?A . They asked me if I was ever arrested before and where had I lived and who did I keep company with or run with, and had I ever owned an automobile and why did I leave my wife and why was I separated from her, and lots of other questions that they asked me.Q. Did they tell you that they were taking

41

you to the Police Station and charge y o u with the murder of Mr. Spencer or anybody else!A. No, sir; I didn’t know I was charged with murder.Q. When you got to the Police Station where were you taken?A. To Chief Griffin ’s office.”Defendant further testified on direct examination before the jury as follows:Beginning on page 586 of the transcript:“ Q. When did they show you, if at all— let’s see the watch— (inspection of watch by counsel for defendant) this particular watch?A. Friday morning.(Inspection of watch by the defendant.)Q. You say you did give your wife a wrist watch ?A . Yes, sir.Q. What else did you give your wife at the same time you gave her a watch?A . A ring._ Q- What else did you give her at the same time you gave her the wrist watch and ring, if anything?A . I didn’t give her anything at that particular time.Q. When was that?

42

A. Way back in March, 1923.Q. What kind of watch did you give your wife ?A . A t the time I gave it to her, I and her noticed it was a 15-jewel watch; it had that name written in the back of it.Q. A Swiss watch?A. Yes, sir.Q. Did yon give your wife this watch at all?A. No, sir.Q. Did they show you that watch at the time they swore out the warrant against you for killing Mr. Spencer?A . No, sir; they had not showed it to me until later.Q. Did or not they arrest your wife first?A . Yes, sir; they had.Q. Did you know it when they came out to arrest you?A . No, sir.Q. A t that time did you know that they had possession of this particular watch?A . No, sir.(Inspection of watch by the Court.)Q. Now, then, Charley, where did you get the pistol?

43

A. I bought the pistol from the same fellow.Q. And who was that?A . Manuel Williams.Q. And where!A . Out at Mr. Crump’s house.Q. Where did you buy the watch and ring!A . Bought them out there, and when I bought them it was in the winter time; and he come up in the servant’s room; it was cold that day, and I happened to—Q. When did you buy the pistol?A. Bought the pistol Ju ly , 1923.Q. Ju ly , 1923?A . Yes, sir.Q. Tell the jury what transaction—when you bought the pistol.A . Well, I was out there that dav working, and he come along and said—TH E COURT: Who came along?A . Manuel Williams. I know him because I had had some dealings with him. He said that he had a pretty good bargain for me if I could raise up some money. I asked him what it was. He showed me that little pistol. I asked him what he wanted for it. He would not state what he would take for it. I told him I didn’t have much money right then and showed

44

what I did have; and lie tried to get me to let him take that; but I said no, to tell what he wanted for it and he would not tel! me, and he asked me if he would come back Saturday would I have it for him. I said if he would tell what he would take for it I would. And finally hummed and hawed around until he said $12.00. I said: you tell me you want $12.00 for that little old pistol? I never did buy a pistol and I didn’t know the value of it before. He said yes, and I will trade you in a lot more things. I said all right. Saturday he came back with the pistol and several other things, and I bought it.Q. What were those several other things?A. Sold me a rug, two rings; and I think it was a hair brush and maybe something else; I don’t just remember the things—what they were now.Q, Did he come back on that Saturday night ?A. Yes, sir, he did.Q. And how much did you pay him for this stuff?A . $12.00.Q. And when was that?A . That was about the second Saturday in Ju ly ; I know it was about the 4th of July.Q. 1923?A . Yes, sir.

45

Q. Did von tell the police officers that you had gotten all of this stuff from this man?A . Yes, sir; told them just exactly how I obtained it and everything the best I could.Q. Wliat was the occasion of George Tons- tall—was he brought up to the police station?A. Well, on Friday morning they asked me -—had been asking me continually on this question, why was I and mv wife separated, and I tried as best I could to tell them; and she had told them some things. And so I just told them, well, one reason I left Lou Ada was because when Mr. Crump and them went away in the summer that I tried to get her to live out on their place with me and she would not do it; and the next week she goes out and starts to staying with George; and of course in that way she caused the separation. They wanted to know who George was and I told them who he was; and they goes out there and gets him and brings him up there and asked him what he knows about it.Q. Now, on Thursday how long did they talk to you about this—had they told you yet you were charged with the murder of anybody?A . On Thursday night?Q. Yes.A . No, sir.Q. When did they first tell you you were charged with murder?A . Friday morning.

46

Q. How long did they talk to you on Friday night?A. Well, I don’t remember. I know we went out on this automobile ride. They talked to me when we got back but I don’t know just how was that they talked to me Friday morning; long. All I remember about Thursday night when daylight came we were in Chief Griffin ’s office still talking; any time I lost that night I don’t remember; I don’t know.Q. Did you get any sleep on Thursday night?A . No, sir; I know I did not.Q. Did they strike you any Thursday morning or misuse you in any way?A. They were cursing me pretty near everything they would ask me, would say I was telling a lie about it and curse me; but I don’t think they hit me any Thursday night; I know that they did Friday morning.Q. What was the circumstances under which they struck you Friday morning?A . Well, when they told me that I was charged with shooting a young man and shooting a young lady I told them I didn’t do it and I didn’t know nothing concerning it. And they told me, well, they had a pistol and wanted to know whether I had seen the pistol before that time or not—that they had the pistol and watch, that the watch come off the young lady’s arm and the pistol was the same caliber that the people were killed with, and if I didn’t do

47

it, having- these things in my possession, I had to tell where I had gotten them from or else they would come to Court and send me to the electric chair without me opening my mouth, if 1 come up and say I gotten it from a strange negro. That was all I could tell, and so they questioned me around and for some cause I was struck that morning by Chief Griffin and another man, Mr. Thompson, T think.Q. Were they at that time trying to get you to confess to the fact that you killed Mr. Obe Spencer ?A . Had been trying all night; and I guess I would have did it if I had knowed what they wanted me to have said. I didn’t then know what they had me for.Q. Now—8 o’clock at daylight Friday morning, they were talking to you!A . Yes, sir.Q. Not for any time did they take you back to the cell?A . On Friday?Q. Friday morning?A . I don’t remember going back Friday morning.Q. You don’t remember going back Friday morning?A. I know I was there at daylight, and was there when Chief Griffin come, right in the same place.

48

Q. ’Did they talk to yon all the morning, or what part of the morning did they talk to you?A. Yes, sir; they talked to me all Friday morning.Q. Had they told you then that thej ̂ had sworn out a warrant or did they just inform you of the fact you had killed Mr. Obe Spencer?A . No, sir: didn’t tell me anything about a warrant and I didn’t know anything about it.Q. You didn’t know anything about that?A. No, sir.Q. What, if anything, did they say to you about confessing, coming through and telling you killed this man?A. Well, they said if you didn’t do it just say you did and we will protect you. They said we, as officers, we will protect you. Showed me some pictures upon the wall of fellows that had did worse things than I did they said, and said they come over and got life and have a chance to get out. And they cautioned me, where there was life there was hope. That was one of their particular words, telling me that they knew the Attorney General over here, and I think they said the Judge, and several others, and said if they come up with a plea for me they could not send me to the electric chair. All I had to do was to come clean and tell them about it, and they would help me out.Q. Were you taken down any time during

49

that day—that was Friday; Friday afternoon were you taken anywhere?A. Well, before that time—sometime in the morning, I was told that if anybody wanted to come to see me for me to say I didn’t want to see them. They said that the officers were willing to protect you. I f you go out and talk with people and people get to coming in here to see you, something is liable to happen to you, they are liable to kill you at any minute; and the papers have gotten out the report you are the man and if you talk to people, anybody is liable to come in here and kill you. They said ‘ you don’t even want to see your boss man. They said if anybody comes here to see you what are you going to tell them? I said I would see them.Q. Were you taken in a car that Friday afternoon?A. Yes, sir; taken over on Madison up in an office upstairs sometime.Q. You were brought back from Madison; where were you taken when you were brought back to the police station?A. I was brought back.Q. That was Friday afternoon?A. Yes, sir.Q. Where were you taken, if anywhere, that night?A . Well, that evening or that night I told them I was hungry and tired and sleepy; and

50

they made several remarks—You are not sleepier than we are, we were up just like you. They finally put me in my cell to get my supper on Friday night, and in a short time they come back and got me.Q. Did you get your supper that Friday night ?A. Well, no, sir: I didn’t get it; it was there, I think, but I didn’t get it; I was so sleepy and tired I just went in there and fell across the bunk in there and went to sleep.Q. Was that the first sleep you had had since you were arrested?A. That was the first I remember of.Q. Up to Friday night?A. Yes, sir.Q. How long were you in your cell at that time ?A. They told me I was in there an hour.Q. You went in and went to sleep?A. Yes, sir.Q. Did they wake you up and take you out of the cell?A . Yes, sir.Q. Where did they take you to?A . They went out Poplar Street to Highland and over Highland to Summer and back in town.

51

Q. Please tell the jury, Charley, what, if anything—how many officers were in the ear with you?A . It was full—a seven passenger car, and it was full. I think three on the back—two on the back with myself, and two up in those little seats and two on the front seat, I think—that is right.Q. Wliat kind of an automobile was it, if you know?A . I think it was a big car; I think it was a Packard.Q. A big Packard car?A . Yes, sir.Q. Please tell the jury, Charley, in your own way, what these officers did to you and what they said to you on that trip to Highland Avenue.A . Well, when they got started out they said to me that they were going to take me for an automobile ride. I said I was sleepy and tired. Would I like to go out in the fresh air? I told them yes, sir. So, by the time—I think they went straight out Adams to Manassas or Court Street, crossed over to Poplar, I don’t just remember; but any way by the time we got into Poplar Street, Chief Griffin was on the back seat with me; he kind of leaned over to me real close. I f I remember correctly he had his arm around my shoulder, and he got real close to me and said, “ Well, now, Charley, we are taking you out for a good nice drive to cool you off. He said: we want you to come clean and tell us

about, this thing. Tell us the truth; tell tis that you committed this crime and we will protect vou.’ 1 told him, well, Chief, 1 didn’t do it and I don’t know nothing about it; you don’t want me to say I did something I didn’t do, do you? He said ‘ no.’ So, as we went on out Poplar Street he continued to question me as to where I had gotten the watch from. By that time we got out I guess to the end of Poplar—not to the end, but where the car line ends, out in the woods where it is dark out there. He put a collar around my neck and told me that it was the dead man’s collar which I had killed. T told him no, sir. He said if I didn’t tell him about it they were going to take me out there and let those people kill me just as I killed that man, only they were going to tie me up to an automobile and drive by and let the people shoot me. T was very frightened at first, and I just begun crying and hollering and saying I didn’t do it, please, sir, don’t let them kill me. They said, well, come clean, then, about it. So by the time we got out to Highland he said to some of the men, don’t drive so fast, to the man that was driving,—don’t drive so fast, Charley is going to tell us about it now. He said just drive slowly; don’t drive so fast and he will tell us. I told him I would tell him anything he wanted to know, but I didn’t know that; he didn’t want me to sav something I didn’t know. So finally they gotten out there and stopped, and they— two of them got out, I think—three of them, got out immediately. They talked around there for a while—Q. Out at what place?A . This was out on Highland Avenue where the place where man got killed.

53

Q. All right,A. So finally they decided to come back to town and said if I would talk to them and tell them about it they would see no harm came to me. So finally they come on back.Q. What did you tell them when they told you to come through and tell them the truth?A . Well, I told them I didn’t know anything about it; finally they—I got so anything they asked me I would say yes, sir, to, but when they asked me did I do it, I would say no, sir, I did not. So he told one of the men—he is almost at the breaking point; just keep him right here in this chair; he will be all right by morning.Q. When was that, after you got back?A, After we got back to the police station.Q. Were you kept in the office of Chief Griffin all during Friday night after you got back?A. Yes, sir; I set right there in that chair.MR. M cCO R M ICK : Let me see the collar.GEN. M cLA IN : Don’t dislodge the bullet in it.Q. Does that look like the collar Chief Griffin put around you?GEN. M cLA IN : Don’t finger the bullet, that is going to be important now; catch it by the other end.Q. Does that look like the collar?

54

A . Yes, sir; that looks like the collar,Q. What did they say to you when Chief Griffin put that collar around your neck?A. He told me to come clean and tell him about it.Q. Tell him about what?A . About the murder of Mr. W. (). Spencer.Q. Did you or not tell the officers that you would confess to this crime?A. Yes, sir; I told them on the way coming- back from out on Highland Avenue that I would if they would see to it that nobody would kill me; and they made me all the promises in the world that they would see to it; and even went so far as to saĵ that they would not double cross me; that they could not do that—something to that effect—that they could not do that.Q. And did they talk to you Friday night?A . Yes, sir.Q. And on Saturday?A . Well, practically all day Saturday.Q. Were you in Chief Griffin ’s private office?A. Saturday?Q. Yes.A . Yes, sir.

55

Q. Did the same officers talk to yon all the time ?A . No, sir.Q. Different officers'?A . Yes, sir.Q. Did they talk to yon at different times— different officers'?A. Yes, sir. Just as the Chief would get through with me there would be somebody to take liis chair and sit right in front of me and talk to me.Q. Now, when did you tell them that you would confess and sign a written statement!A . Well, I told them that I would do anything when we got hack from Highland Avenue.Q. On Saturday night when did you tell the officers that you would do anything they wanted you to do and sign the statement?A . That was late Saturday night I know. 1 was very nearly gone. I could not hardly sit up that Saturday night.Q. Charley, were you allowed to get any sleep on Friday night?A . No, sir, not a wink.Q. Were you allowed to get any sleep or. Saturday?A . No, sir; not a wink.Q. And up until Saturday night at 11 or

56

12 o’clock, were you allowed to get any sleep?A . No, sir.Q. Tell us what, if anything, the officers would do when you would doze off or go to sleep in vour chair?A. Well, it was a large man stayed with me Friday night, and another small man and some police officers, and usually there was somebody sitting right in front of me and I would sometimes do that way and they would knock my hand out from under my chin like that, and if they caught me sleeping they would kick me on the leg and wake me up and somebody would pull my ears and raise my chin up or maybe take my head like that and push it up. Several times they pulled my ear. Said they thought a good cup of cold water would do me good. I said if you would give me a drink I would like to have it. They said no, they would not give me a drink until the Chief come, then they would give me some water.Q. That was on Friday night?A . He give me some water Saturday morning. # # * * #Q. State whether or not you were cursed by the officers?A . Yes, s ir; everything that could fall from the lips of a man. Even in the presence of my wife I was cursed and she was cursed— the lowest things that could fall from the lips of a man.

57

Q. Charley, did you kill Mr. Obe Spencer.A . No, sir, I did not.Q. Have you ever killed anybody?A . No, sir.Q. Have you ever robbed anybody?A . No, sir; always tried to work hard and make an honest living.Q. Did you kill Miss Ruth Mcllwain Tucker ?A . No, sir.Q. Did you kill Mr. Waller?A . No, sir.Q. What, if anything, was said to you by the officers before you signed these confessions in reference to feeding you?A . Told me I would not get a bite until they had cleared up this thing completely. They said I had made enough statements regarding it and I had to complete it before I would eat, sleep or drink; and if I would come clean and tell the thing through and through and say what they told me to say or answer their questions, that they would give me a nice place to sleep, some water and buy me a lunch out of their pocket. Several of them offered to buy me anything I wanted out of their own pockets, and the Chief tole me that he would do something that he never had did it before in his life and never did in the history of Memphis that he had known of, and that was to let me go up and sleep with my wife.

58

Q. Was that about the time you signed these papers that they wrote out there?A . I think it was.”# # # # *Defendant further testified on direct examination before the jury with reference to using Bert Stevens’ car, as follows:Beginning on page 602 of the transcript:“ Q. Do you know Bert Stevens?A . Yes, sir.Q. Was he working for Dr. Maury when you were working out there?A . Yes, sir.Q. What kind of an automobile did Burt Stevens have?A . An old model Ford touring car.Q. Did he have a self-starter on it ?A . No, sir.Q. Is there any peculiarity about Bert Stevens, any part of his body withered?A . Yes, s ir; he has a withered hand.Q. Can he crank a Ford automobile?A . No, sir.Q. Did you drive or keep his car—the old Ford automobile?

59

A . Yes, sir. I have did some work on it, and in my doing work on it I have kept it for a long period of time. One time I got a part of it down there and kept it a good while.Q. When was that automobile sold!A . Well, he traded it in for—if I remember correctly, on May 15th.Q. Of what year?A . 1923.Q. That old Ford automobile was tradedwhen ?A . May 15, 1923.Q. Who traded the automobile?A. Bert traded i t ; I was with him.Q. You were with him?A . Yes, sir.Q. And where?A . A t Price-Barwick on Union Avenue.Q. What kind of a car did you get then?A . He gotten one that he could drive himself; he gotten one with a starter on it.Q. Self-starter?A . Yes, sir.Q. After that did you use Bert Stevens’ automobile 1

60

A. No, sir; never did after that.Q. How do you remember that date?A . On that date—same date, my wife’s sister was buried and we went home with them arid come on from there over to Price-Bar- wick’s with Bert to get his car and told him what I thought about it being a pretty good trade. ’ ’The following other testimony was introduced in behalf of defendant on preliminary examination in the absence of the jury.Beginning on page 216 of the transcript, the testimony of Emmett Gowan:“ Q. What is your name?A . Emmett Gowan.Q. What is your occupation?A. Reporter for the Scimitar.Q. Did you have occasion to be over at the Police Station at Inspector G riffin ’s office the night that Charles Barr was supposed to have signed the confession.A . Yes, sir.Q. Can you state the condition of this boy Charles Barr at the time he signed that confession?A . I could not state his condition; I could state what his condition appeared to me to be.

61

Q. As -it appeared to you, his physical appearance.A . He seemed to be tired out; he could not talk very well.”Beginning on page 221 of the transcript, the testimony of Mr. C. L . Van Fossen:” Q. What are your initials, Mr. Van Fossen?A . C. L . Van Fossen.Q. Where do you live?A . 292 East Parkway, North.Q. Was Charley Barr in your employ at the time he was arrested?A . Yes, sir.Q. After his arrest did you make any visit or visits to the police station?A . Yes, I called the night he was arrested.Q. Who was with you?A. My wife.Q. Will you please tell what transpired at the police station on the occasion of your first visit ?A . I called to see Inspector Griffin and wanted to talk with Charley Barr because I believe that possibly he was innocent.GEN . M cL A IN : Ju st a minute. Just tell

62

what you did and not what you believed, or yoru opinion.Q. Ju st tell your conversation with Chief G riffin!A . I asked him if I could see Charley and talk with him. I had called over the phone and talked to one of the men, and we had this conversation over the phone, and I told him I wanted to talk to Charley with the idea of finding out or trying to help Inspector Griffin find out who was guilty.GEN . S H E A : Ju st a minute, if your Honor, please, I object to what he was trying to do or to the conversation he had.A. That was the conversation.Q. Proceed.A . I knew he was being held because a watch had been found that had been stolen from the lady that was shot. And I told Inspector Griffin that I might be able to get the information from Charley as to where this watch was gotten and that that would prove who wTas guilty, or help to prove it, but he wouldn’t let me see him.Q. Why did he say he would not let you see him?A. He said that outsiders talking with some one they were working on would interfere with his work.Q. Did you go to the police station the next morning?

63

A. I did.Q. What transpired then?A. I talked to him.Q. To wrhom?A. Inspector Griffin.Q. A ll right.A . And he wouldn’t let me see him. He said he had him almost to the breaking point, and he was afraid that my coming in would interfere.Q.point, That he had him almost at the breaking and he wouldn’t let you see him?A. No.Q. Told you you couldn’t see him?A. Yes.Q. Then where did you go!A . I tried to see Commissioner Allen. I knew him, and went to his office, or tried to locate him. I felt that he might be able to getme permission to see him, and I made it clear to Inspector that I didn’t want to help shield anyone that might be gnilty, that I really wanted to help them as much as possible, and that I wanted to help the boy if he was innocent, and I couldn’t see Commissioner Allen, and I started over to the office, and I knew Dave Puryear, and I thought I would go in and see him and see what he would suggest. I went by and saw him, and I told him they wouldn’t

64

let me see him, and Judge Puryear said that if he had an attorney an attorney could see him, so I asked him if he wouldn’t be my attorney and go ahead with it and arrange the matter so I could see him. We went over to the police station, Mr. Puryear with me, and we tried to see Charley over there.Q. Were you there with Judge Puryear when he made application to see Charley Barr ?A . Yes sir.Q. As his counsel?A . Yes sir.Q. Now what transpired?A . We saw Inspector Griffin go in the office. We didn’t get to talk with him, but we did ask another man, I believe it was his Secretary, and we asked to see Charley, and he went in and I presume asked Inspector Griffin if we could see him, but he came out and told us that we couldn’t.Q. Did the Secretary of Inspector Griffin tell Judge Puryear, the attorney for Charley Barr, that he couldn’t see him?A . Yes sir.Q. In your presence?A . Yes sir.Q. What did Judge Puryear do?A . He said that he would see him, that he would get a habeas corpus to see him.

65

Q. And the habeas corpus was sued out!A . Yes sir.Q. And Judge Puryear asked as Charley’s counsel to see him and was refused!A . Yes sir.Q. And he appeared as his counsel in Police Court when he was bound overtA. Yes sir, that is right.Q. You know that the—just a minute. On the occasion of the first visit, what time of the night or evening was it?A . It was after dinner, I presume about 8 or 8:30.Q. And what was the time that you went down the next morning!A . I don’t recall now. I would say somewhere around 10 o ’clock.Q. What time—you talked to them over the telephone. What did they tell you they were holding him for! What did they tell you on what charge?A . Mrs. Van Fossan telephoned. She had sent Charley out of the house to do some work. I was down town and when I got home she told me that they had arrested him, or that somebody come out and took him away. That was all she knew. I assumed that probably he was at the police station, and I asked them if they had him there, and they told me they had him there in connection with murder.

66

Q. With the Obe Spencer murder!A . Yes sir.Q. And that was the day of the arrest!A. That afternoon.Q. They told you they were holding him in connection with the Obe Spencer murder!A. That is right.Q. And it was the same night you went down at 8 o ’clock!A . Yes sir.”Beginning on Page 230 of the transcript, the testimony of Dr. N. K . Moody, as follows:“ Q. State your name to the Court!A . N. K . Moody.Q. What is your business!A . Physician.# # # # *Q. Since 1915, Doctor, I will ask you if you had occasion to be at the court house in Chief G riffin ’s—I mean at the police station in Chief G riffin ’s private office during the time that the defendant Charley Barr was being questioned ?A . Yes sir; I went by about 10 or 10:30 on Friday night, and stayed until about 9 o ’clock Saturday morning.

67

Q. About 10 or 10:30 Friday night!A . Yes sir.Q. That was the 18th of Ju ly !A . I guess it was. I don’t know.Q. And stayed until about 9 o ’clock on the next morning!A . Yes sir.Q. That would be the 19th, if that was the 18th!A . Yes sir.

O'. -V. " J/. •I',-w -r.~ w wQ. Now, what was the condition, the physical condition of Charley Barr at the time, doctor ?A . Well, his physical condition seemed to be a little sleepy—he did.Q. He seemed to be a little sleepy. Did he or not answer the questions in a monotone!A . Yes. He didn’t answer them. He just would mumble them.Q. Was that mumbling loud and very audible, or very low and indistinct?A . It varied. Sometimes it was and sometimes it was a little indistinct.Q. I will ask you "whether or not he seemed at that time to be groggy ?GEN . S H E A : Ju st a moment, if the Court please.

68

MR. C R E A S Y : I think that is a proper question. I asked him whether or not.GEN S H E A : Ju st a moment. I haven’t made my objection.MR. C R E A S Y : I beg your pardon.GEN . S H E A : I f the Court please, I would suggest that the counsel not lead the witness, but let the witness testify.T H E C O U R T : He asked whether he appeared to be groggy or not. I f he knows he may answer that question. Proceed.Q. Did he or not, doctor?A . Well, I didn’t make any test on him. Ju st from observation he probably might have been groggy.Q. From your observation of him did he look to be in that condition ?A . Well, I think so.Q. You think so?A . Yes sir.Q. You stayed there from about 10:30 that night until after 9 o ’clock the next morning. Did the examination or questioning of Barr by the officers continue throughout that time?A . More or less; yes sir.Q. Was he questioned all of that time by

69

the officers—by one officer, or did the officers work in relays?A . Not one continually, but several of the officers questioned him.Q. They worked in relays and one questioned him a while and then another officer questioned him for a while?A . Yes sir.

Q. You stated that lie appeared to be sleepy. I will ask you whether or not, doctor, during the course of this questioning he tried to sleep!A . Yes, he would almost go to sleep.Q. And, doctor, did he prop his head on his hand, in this position (indicating) with his elbow on his knee?A. I don’t remember. Several times when he didn’t answer questions they would get hold of his shoulder and ask him to talk, to answer the question. They wanted to find out whether he was guilty or innocent, or not.Q. That was when he was trying to sleep?A . Yes sir.Q. Did jrou notice this, doctor? Look at my position here. That he would prop his chin on his hand like this and try to sleep?A . I think so; yes sir.Q. And when he did that, doctor, I will ask

70

you whether or not an officer would knock that hand out from under his chin in order to wake him up?A . I don’t remember whether he did that, but they would ask him to—shake him and tell him to wake up and answer the question.Q. They would shake him and tell him to wake up and answer the question?A . Yes sir.Q. I want you to be positive about that, doctor. Did you or not at any time see any of the officers there that might knock his chin out from under him while he was trying to sleep?A . I really don’t know. Possibly they did.Q. Possibly they did. You couldn’t be positive about that doctor?(No answer)Q. In questioning this defendant did the officers call him names?A . Well, they—MR. M cC O R M IC K : Answer the question, doctor.A . I don’t remember exactly all about the conversation or anything that took place there.Q. That is very true.A . It is possible—might have been.T H E C O U R T : What do you mean by calling him names?

71

MR. M cC O R M IC K : Bad names, applying epithets to him.M E. C R E A S Y : They applied epithets to him, and if your Honor will permit me, I would like to call some of them, and ask the witness if those epithets weren’t applied to the defendant.T H E C O U R T : You weren’t there, were you? MR. C R E A S Y : No sir.T H E C O U R T : Well, you don’t know what was said. Ask the witness what was said, and if he knows he can state it.Q. I will ask you, doctor, whether or not, at any time during the course of this questioning they applied to this defendant vile names?A. They called him a murderer several times.Q. Did they call him a S. B .f A . I expect they did.Q. And they did that numerous times, did they, doctor?A . GEN . M cL A IN : Don’t lead the witness so much. He is an intelligent man. He is a doctor. He can answer your questions without leading him.T H E C O U R T : Do you know whether they did or not. That is what he wants to know.A . I don’t know what they called him and

I can’t state exactly at this time what they did call him.Q. But they did call him vile names?*A . They would talk to him and try to get him to tell them about this, and he wouldn’t answer, and then they would go on and call him a murderer and all of that, and tell him they knew he was a murderer and ask him to tell them about it.Q. In other words, when they called him a murderer, did they cuss him, too?A . Yes sir.Q. They did do that?A . (No answer),T H E C O U R T : He said “ Yes sir” nodded his head. Did they do that or not?GEN . M cL A IN : I f your Honor please, I want to make this objection. As I understand the rule, he has a right to direct the attention of the witness. He hasn’t got the right to make a suggestion. Mr. Creasy is asking the witness if such and such wasn’t done?T H E C O U R T : He has a right to do that.G E N . M cLA IN . But not his witness.T H E C O U R T : He has the right to direct attention of the witness.Q. Did they or not cuss him, doctor?

73

A . They probably did.T H E C O U R T : Answer yes or not.Q. Did they or not!A . Yes, I think they did.Q. Did you tell him that—did they or not tell him that it would be better for him if he confessed to it?A . They told him if he was guilty they wanted him to confess, and if he was not guilty they wanted him to tell where he had gotten this evidence they had so that they could free him,G-EN. M cL A IN : That is fair enough.MR. C R E A S Y : I am going to object to that now, your Honor.T H E C O U R T : I f you want to make an objection make it to the Court.. Don’t argue among yourselves.Q. Did they or not tell him that he committed the murder and it would be best for him to confess to it, did that occur?A . Yes sir, they said he committed the murder.Q. And that it would be best for him to confess to it, did that occur?A . Yes sir, they said he committed the murder.

74

Q. And that it would be best for him toconfess to it!GEN . Mel .A IN : I f your Honor please, I object to counsel leading the , witness. This is his witness. Don’t lead him.T H E C O U R T : You were there from when ?A. From 10:30 until 9 o’clock next morning.T H E CO U R T : Ju st tell what happened and what was said, as you remember it.A. There was quite a line of questioning to him. They questioned him and asked him about all of these things, and he would tell them about it, and then they would check that up and find it wasn’t so, and then he would say something else, and I don’t remember everything that was said.MR. C R E A S Y : I want to make this observation to the Court. It is perfectly apparent to the court that this witness is very reluctant in his testimony in telling what happened there. I don’t mean to try to evade the rule of evidence in examining him by leading any witness, but it is perfectly apparent to the Court that I have got to put in the mind of the witness the thing that I want to ask him about.T H E C O U R T : This is an intelligent witness, a physician and he was there from 10:30 until 9 o’clock the next morning. He ought to be able to tell what happened there and what was said.GEN . M cL A IN : Does he claim that this is a hostile witness?

75

MR. C R E A S Y : No, but a very reluctant witness.GEN . M cLA IN : I don’t see what right that gives you to lead him.

Q. I want to ask you, doctor, whether or not in the course of your question— I mean his questioning there he was told that he was a murderer and it would be better for him to confess to it?A . Yes sir.GEN. M cLA IN : I f your Honor please, 1 object to that, he has already answered that question?MR. M cCORM ICK: What was your answer, doctor?A . Yes, sir.GEN. M cLA IN : He has already answered it.Q. During the course of that questioning, did they or not tell him that it would be worse for him if he didn’t confess?GEN. M cLA IN : I f your Honor please, I object to that. I f that isn’t leading question, I never heard one.TH E COURT: Did—MR. C R E A S Y : That is not a leading question.TH E COURT: Did he make that statement or not?

76

A. They made the statement it would be a lot better if he would confess.Q. The last question was, did they or not tell him it would be a lot worse for him if he didn’t confess ?A . Possibly they did. It means about the same thing. # * # *Q. Now, then, did they tell him when he denied it, did they or not tell him when he denied it it would be worse for him if he didn’t confess?A. Possibly they did.”And on cross examination, beginning on page 245 of the record:’ 4 Q. As I understand from you, around 9 or 9:30 he appeared to be sleepy and tired. Did you say he was groggy then at all?A . He got a little groggy, Mr. McLain.Q. I am talking when you first went in there. Between 9 and 10 o’clock, was he a little groggy?A. He might have been then. I f he was he got more groggy.”And on re-direct examination, beginning on page 254 of the record:“ Q. One other question. When you left there on Saturday morning about 9 o’clock

77

were the officers at that time continuing their questioning?A . Yes, sir.Q. They were?A . Yes, sir.”Beginning on page 255 of the transcript, the testimony of Judge I). B. Puryear:“ Q. What is your name?A. D. B. Puryear.Q. Judge Puryear, you are a practicing attorney at the Memphis Bar?A. Yes.Q. And you have been for many years?A . 13 years.Q. And you were Judge of the First Division of the Criminal Court for how many years?A . Two and a half years—the thirteen includes the two and a half..Q Judge Puryear, were you at any time employed to represent Charles Barr as his counsel ?A . Yes. His employer, Mr. Van Fossan, came to see me one day, on the day that he was arrested, as I understand, and employed me to confer with him and to look after him in any way that I could as his counsel, telling me he was charged with a serious offense of some

78