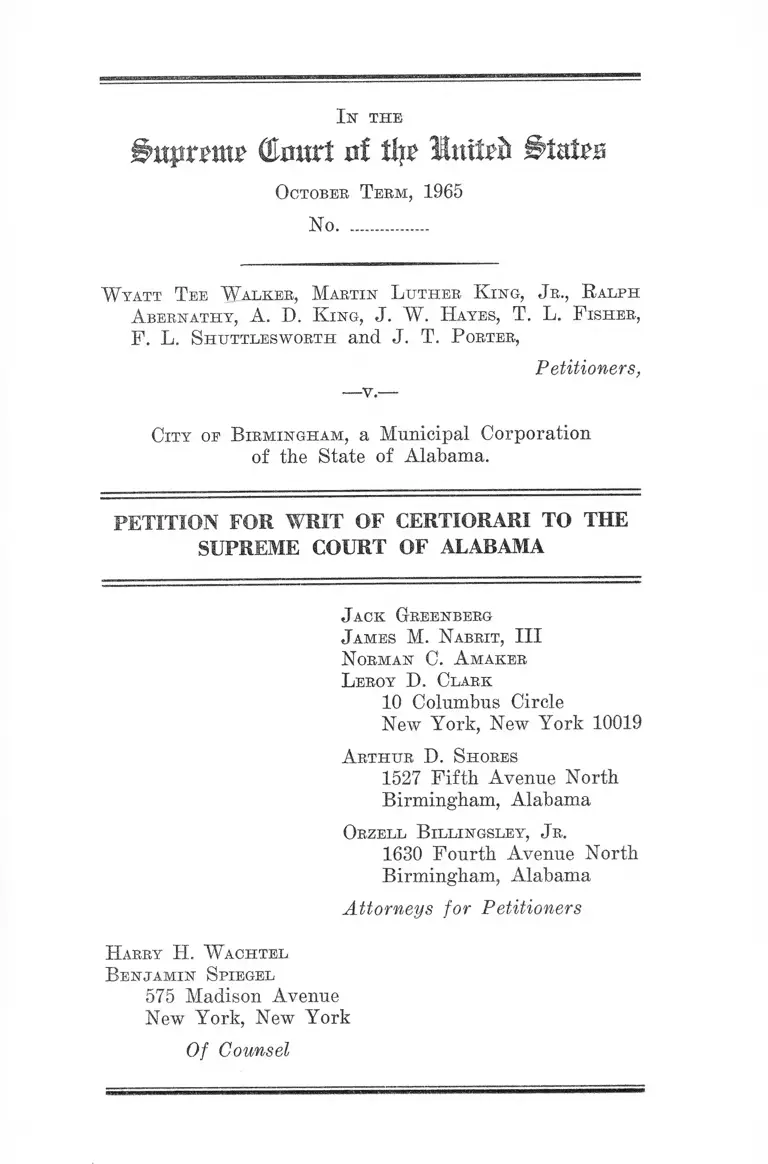

Walker v. City of Birmingham Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Walker v. City of Birmingham Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1965. ea998041-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b4996f91-9cff-4a9e-b216-607f3189c358/walker-v-city-of-birmingham-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

I n THE

dkmrt of tip linxk'h Hiatus

O ctober T erm , 1965

No..................

W yatt T ee W alker , M artin L u th er K in g , J r ., R alph

A bern ath y , A . D. K in g , J. W. H ayes, T. L . F ish e r ,

F. L . S h u ttlesw orth and J. T. P orter,

— v .—

Petitioners,

C ity of B ir m in g h a m , a Municipal Corporation

of the State of Alabama.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N orman C. A m aker

L eroy D . Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A r th u r D. S hores

1527 Fifth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

Orzell B illin gsley , J r .

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Petitioners

H arry H . W ach tel

B e n ja m in S piegel

575 Madison Avenue

New York, New York

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below .............................................. 1

Jurisdiction .......................................................................... 2

Questions Presented .......................................................... 2

Statement .............................................................................. 4

A. General Background ............................................. 4

B. Events Leading to the City of Birmingham’s

Prayer for Injunction .......................................... 7

C. The Injunction .............................................. 11

I). Continuation of Peaceful Protests Against

Segregation ....................................................... 12

E. Contempt Judgment: How the Federal Ques

tions Were Raised and Decided Below ............. 14

R easons foe Gran tin g th e W r i t :

I. Petitioners’ rights under the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment were infringed by their conviction

for contempt where the injunction they are

charged with disobeying is in violation of their

First and Fourteenth Amendment rights .......... . 19

A. The ex parte injunction of April 10, 1963,

and Section 1159 of the Birmingham City

Code violate petitioners’ First and Fourteenth

Amendment rights .............................................. 21

1. Vagueness of the Injunction’s Terms ....... 21

2. The Uneonstitutionality of §1159 on Its

Face and as Applied .................................... 25

3. Improper Exclusion of Evidence on the

Unconstitutional Application of §1159 .... 29

B. The conviction denied due process because

there was no evidence petitioners participated

in a forbidden “unlawful” parade or demon

stration .................................................................. 30

II. Assuming* arguendo that petitioners did disobey

the injunction, Alabama may not validly punish

them because the ex parte injunction was void

as an unconstitutional infringement of their

rights to free speech and assembly .......... ........ 32

III. Petitioners King, Abernathy, Walker and Shut-

tlesworth may not be punished for their Con

stitutionally Protected statements to the press

criticizing the injunction and Alabama officials .... 38

IV. The conviction of petitioners J. W. Hayes and

T. L. Fisher denied them due process because

there was no evidence that they had notice of or

knowledge of the terms of the injunction ........... 42

C onclusion .............................. 45

A p p e n d ix —

Circuit Court Opinion Dated April 26, 1963 ......... la

Opinion of Supreme Court of Alabama Dated

December 9, 1965 ................................................... 8a

Judgment of Supreme Court of Alabama Dated

December 9, 1965 ........................................ 30a

Denial of Rehearing Dated January 20, 1966 ....... 32a

i i

PAGE

Some Ordinances of City of Birmingham. Ala

bama, Requiring Segregation by Race ............... 33a

Statutes of State of Alabama Conferring Con

tempt Powers on Courts ....................................... 34a

Table or A uthorities

Cases:

Ashton v. Kentucky, ------ U.S. —— (May 16, 1966),

34 U.S.L. Week 4398 ...................................................... 24

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360 .................................. 24

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58 ...........24, 35

Barr v. City of Columbia, 378 U.S. 146 ....................... 30

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 ................................... 35

Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252 .............................40, 41

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296 ........................... 24

Carter v. Texas, 177 U.S. 442 .......................................... 30

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 129 — ....................-.... 30

Congress of Racial Equality v. Douglas, 318 F.2d 95

(5th Cir. 1963) ............................................ -................ 33

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 ........................-.......... -..... 35

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 ...... ........ 20, 22, 24,26, 28, 29

Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U.S. 569 .................... -....... 26

Craig v. Harney, 331 U.S. 367 ..... ......................... ........ 40, 41

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U.S. 278 .... 24

Davis v. Wechsler, 263 U.S. 22 ....... ..... ....... ................. 37

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 ........................... 24

Donovan v. Dallas, 377 U.S. 408 ............... ................... 33

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 ...........20, 22, 24

Ex parte Fisk, 113 U.S. 713 .........-............. -................. 36

Ex parte Rowland, 104 U.S. 604 .................................. 36

Ex parte Sawyer, 124 U.S. 200 ..................................... 36

Ill

PAGE

IV

Fields v. City of Fairfield, 375 U.S. 248 .......21, 30, 32, 33

Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U.S. 44 ...... ............... .22, 24

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U.S. 51 ...........................26, 35

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 ________ _____ 23, 30

Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64 ....................... ...40, 41

George v. Clemmons, 373 U.S. 241 ................... ........ 36

Gober v. Birmingham, 373 U.S. 374 _______ ________ 6, 22

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496 .................. .................... 26

Hamilton v. Alabama, 376 U.S. 650 ............................ 24, 35

Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 ......... ......................... 37

Henry v. Rock Hill, 376 U.S. 776 .............................. 22,24

Holt v. Virginia, 381 U.S. 131 ............. ............. ...... .... 40

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U.S. 61 ..... ....... ............. 24, 35, 37

Kunz v. New York, 340 U.S. 290 ....... ......... ...... ...... . 26

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U.S. 451 ....................... 42

Largent v. Texas, 318 U.S. 418 ............ .......................... 26

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267 ............. ............ 28

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U.S. 444 ............................ .... .... 26

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449 ........ ........... ...... 24, 33, 37

NAACP v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 288 _______ _______ ___ 37, 41

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415........ ......... ............ 24, 35, 36

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 ....... ............ .............. 35

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 __ __ _ 40

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268 ....... .... ................ 26

Pennekamp v. Florida, 328 U.S. 331 ................. ......... 40, 41

Primm v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala. App. 657, 177

So.2d 326 (1964) ................................. ................. ........ 27

PAGE

V

Re Green, 369 U.S. 689 .................................................... 36

Re Oliver, 333 U.S. 257 ..... .....................................34,36,37

Re Sawyer, 360 U.S. 622 ........ ..... ................................38,40

Saia v. New York, 334 U.S. 558 ................................... 26

Schneider v. State, 308 U.S. 147 ................................... 26

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 .................................. 24, 35

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 U.S. 87 ...............26, 30

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham,------ Ala. App.

------ , 180 So. 2d 114 (1965) ........... ............... 25,27,31,41

Shuttlesworth and Billups v. Alabama, 373 U.S. 262 .... 22

Smith v. California, 361 U.S. 147 ................................... 24

Staub v. Baxley, 355 U.S. 313 ..... ... .............................26, 27

Stevens v. Marks, 383 U.S. 234 .................................... 36, 37

Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S. 359 .......................24, 38

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U.S. 154 ................. ............... 30

Terminielio v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 ............................ ... 24

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U.S. 516 ........ .............. 24, 35, 36, 38

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U.S. 199 .......21, 30, 32, 42, 44

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 8 8 .................................. 24

United Gas, Coke and Chemical Workers v. Wisconsin

Employment Relations Bd., 340 U.S. 383 ............... 36

United States v. Chambers, 291 U.S. 217 ....................... 37

United States v. Shipp, 203 U.S. 563 ............................. 34

United States v. State of Alabama, 252 F. Supp. 95

(M.D. Ala. 1966) ....................... ............. .............. ........ 6

United States v. United Mine Workers, 330 U.S. 258

20, 32, 33, 34, 35,36

Williams v. North Carolina, 317 U.S. 287 ..................... 38

Wood v. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375 ................................40,41

Worden v. Searls, 121 U.S. 1 4 ........................................ 34

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U.S. 284 .................................... 37

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 ................................ 25, 27

PAGE

VI

Statutes :

Alabama Code (Recompiled 1958), Title 13, §§4, 5, 9 .... 4

Building Code of City of Birmingham (1944), §2002.1 .. 4, 6

General Code of City of Birmingham (1944), §369 ....4, 6,17

General Code of City of Birmingham (1944), §597 ....... 4, 6

General Code of City of Birmingham (1944), §1159..... 3, 8,

19, 20, 21, 25, 27,

29, 30, 31, 41,43

28 U.S.C. §1257(3) .............................................................. 2

Other Authorities:

Congress and the Nation 1945-1964: A Review of Gov

ernment and Politics in the Postwar Years (Congres

sional Quarterly Service, 1965) ................................... 5, 6

Note, Amsterdam, The Void-for-Vagueness Doctrine

in the Supreme Court, 109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 67 (1960) .. 23

1963 Report of the United States Commission on Civil

Rights (Government Printing Office, 1963) .............5,6,7

United States House of Representatives, Committee on

the Judiciary, 88th Congress, 1st Session, Hearings

on Civil Rights, Part II ...

PAGE

7

I n the

Olflurt it! % Imtpft #tat£0

O ctober T erm , 1965

No..................

W yatt T ee W alker , M artin L u th er K in g , J r ., R alph

A bernath y , A. D. K in g , J. W. H ayes, T. L . F ish er ,

F . L . S h u ttlesw orth and J. T. P orter,

Petitioners,

Cit y oe B ir m in g h a m , a Municipal Corporation

of the State of Alabama.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama entered

in the above entitled cause December 9, 1965, infra, p. 30a,

rehearing denied January 20, 1966, infra, p. 32a.

Citations to Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama is re

ported at ------ Ala. ------ , 181 So.2d 493 (1965), and is

printed in the Appendix hereto, infra, pp. 8a-29a. The

opinion of the Circuit Court for the Tenth Judicial Cir

cuit of Alabama (Jefferson County) is unreported, but is

printed in the Appendix hereto, infra, pp. la-7a.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama was

entered December 9, 1965, infra, p. 30a. Motion for re

hearing was denied by the Supreme Court of Alabama

January 20, 1966, infra, p. 32a. Petitioners’ time for filing

petition for writ of ceritorari was extended to and includ

ing June 19, 1966 by an order signed by Mr. Justice Black

on April 13, 1966.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

§1257(3), petitioners having asserted below and asserting

here deprivation of rights secured by the Constitution of

the United States.

Questions Presented

I. Whether petitioner’s convictions for contempt for

alleged disobedience of an ex parte injunction restraining

certain protest demonstrations against racial segregation

violate the First Amendment and the Due Process and

Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment

on the ground that:

A. The injunction was unconstitutional because,

1. The terms of the injunctive decree were imper

missibly vague;

2. The injunction enforced an ordinance punishing

parades without permits which is unconstitutional on

its face and as applied on due process and equal pro

tection grounds;

3. The trial court improperly excluded evidence

bearing on the unconstitutional administration of the

parade ordinance;

3

B. There was no evidence that petitioners violated

the terms of the injunction’s prohibition against “un

lawful” parades and demonstrations I

II. Whether the court below was correct in holding that

even if the injunction unconstitutionally restrained free

expression, petitioners could be held in contempt for fail

ure to obey it?

III. Whether petitioners M. L. King, Jr., Abernathy,

Walker and Shuttlesworth were denied due process by

being punished in part because of constitutionally pro

tected statements to the press criticizing the ex parte

injunction and Alabama officials?

IY. Whether petitioners Hayes and Fisher were denied

due process by conviction without any evidence that they

had notice of or knowledge of the terms of the injunction?

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. This case involves the First Amendment and Section

1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

2. This case also involves the following ordinance of the

City of Birmingham, a municipal corporation of the State

of Alabama:

General Code of City of Birmingham,

Alabama (1944), §1159

It shall be unlawful to organize or hold, or to assist

in organizing or holding, or to take part or participate

in, any parade or procession or other public demon

stration on the streets or other public ways of the

city, unless a permit therefor has been secured from

the commission.

4

To secure such permit, written application shall he

made to the commission, setting forth the probable

number of persons, vehicles and animals which will be

engaged in such parade, procession or other public

demonstration, the purpose for which it is to be held

or had, and the streets or other public ways over,

along or in which it is desired to have or hold such

parade, procession or other public demonstration. The

commission shall grant a written permit for such

parade, procession or other public demonstration, pre

scribing the streets or other public ways which may

be used therefor, unless in its judgment the public wel

fare, peace, safety, health, decency, good order, morals

or convenience require that it be refused. It shall be

unlawful to use for such purposes any other streets

or public ways than those set out in said permit.

The two preceding paragraphs, however, shall not

apply to funeral processions.

3. The following Alabama statutes and Birmingham mu

nicipal ordinances involved are set out in the Appendix,

infra, pp. 33a to 35a:

Code of Alabama (Recompiled 1958), Title 13, §§4, 5, 9;

General Code of City of Birmingham, Alabama (1944),

§§369, 597;

Building Code of City of Birmingham, Alabama (1944),

§2002.1

Statement

A. General Background

These cases involve judgments of contempt adjudicated

against petitioners by the Circuit Court of Birmingham,

5

Alabama, for peaceful protest demonstrations against

racial segregation on two occasions, contrary to an ex

parte injunction ordering them to refrain from “unlaw

ful” parades, and for allegedly speaking in a contumacious

manner about the court which issued the injunction. The

case involves, of course, certain discrete acts of petitioners.

But these acts have limited meaning unless seen in their

historical context. Petitioners, therefore, introduce this

Statement by reference to officially documented facts which

put the issue in perspective.

In early 1963, Birmingham. Negroes appealed to the

public conscience through peaceful protest demonstrations

in an effort to secure redress of their grievances, since

other avenues were severely limited. Only 11.7% of

Negroes of voting age were registered to vote in 1962

in Jefferson County (Birmingham), despite long-standing

suits against voting discrimination by the United States

and private individuals.1 This situation was reflected in

the fact that no Negroes were employed as city police

officers, tax officials, government lawyers, court officials,

officials in the public health or public works department

in the City of Birmingham, except in the performance

of maintenance, janitorial or similar duties (R. 188). A

“ self-proclaimed white supremacist, Eugene (“Bull” ) Con

nor,” was Commissioner of Public Safety, the head of

the police department and one of the three governing

commissioners of the City.2

11963 Report of the United States Commission on Civil Rights (Gov

ernment Printing Office, 1963), p. 32.

2 Congress and the Nation 1945-1961: A Review of Government and

Politics in the Postwar Years (Congressional Quarterly Service, 1965),

p. 1604.

6

Segregation of the white and Negro races was enforced

by law in virtually every aspect of public life in Birming

ham.8 Municipal ordinances provided for segregation in

restaurants, places of entertainment, and sanitation facili

ties.3 4 5 Gober v. Birmingham, 373 U.S. 374 (1963), decided

following events involved in the instant case, held that

enforcing the municipal segregation ordinances through

trespass convictions denied equal protection of the laws.

No Negroes attended schools with whites in Birmingham

or elsewhere in Alabama during the school year 1962-63.6

In June 1963, just after the Birmingham demonstrations,

at the University of Alabama (Tuscaloosa) Governor

George C. Wallace carried out his 1962 campaign pledge

“ to stand in the schoolhouse door” to prevent integration

of Alabama’s schools, in the face of a federal court order.6

But despite the fact that an appeal to conscience through

peaceful protests against legally enforced segregation was

3 Alabama had enacted sweeping racial segregation laws which were

applicable in Birmingham. In United States v. State of Alabama, 252

F. Snpp. 95, 101 (M.D. Ala. 1966), Circuit Judge Rives pointed out

in 1966 that “ there are still forty-four sections of the Alabama Code

dedicated to the maintenance of segregation.” The opinion recounts

many aspects of the official policy of segregation and cites the statutes

and eases.

4 Birmingham municipal ordinances provided, among other things, that

places for the serving of food (§369 General Code), places for the

playing of certain games (§597 General Code), and toilet facilities

(§2002-1 Building Code) must be segregated (R. 110). These ordinances

are printed in the Appendix hereto, infra, p. 33a.

5 1963 Report o f the United States Commission on Civil Rights, supra,

p. 65.

6 Congress and the Nation 1945-1964, supra, p. 1601.

7

an appropriate response to the situation, the United States

Civil Eights Commission concluded in its 1963 Report that:

The official policy in . . . Birmingham, throughout

the period covered by the Commission’s study, was

one of suppressing street demonstrations. While

police action in each arrest may not have been im

proper, the total pattern of official action, as in

dicated by the public statements of city officials, was

to maintain segregation and to suppress protests.

The police followed that policy and they were usually

supported by local prosecutors and courts.7

Referring to the Birmingham situation, President Ken

nedy in June 1963 submitted a broad civil rights program

to the Congress which became the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The President addressed the American people in a nation

wide television address and made “an appeal to conscience

—a request for their cooperation in meeting the growing-

moral crisis in American race relations.” 8

B. Events Leading to the City of Birmingham’s

Prayer for Injunction

Petitioners Wyatt Tee Walker, Martin Luther King, Jr.,

Ralph Abernathy, A. D. King, J. W. Hayes, T. L. Fisher,

F. L. Shuttlesworth and J. T. Porter are members and

7 1963 Report of the United States Commission on Civil Bights, supra,

p. 112.

8 United States House of Representatives, Committee on the Judiciary,

88th Congress, 1st Session, Hearings on Civil Bights, Part II, pp. 1446-

1447. In his message to the Congress, the President said:

“ The venerable code of equity law commands ‘for every wrong,

a remedy.’ But in too many communities, in too many parts of

the country, wrongs are inflicted on Negro citizens for which no

effective remedy at law is clearly and readily available. State and

local laws may even affirmatively seek to deny the rights to which

these citizens are fairly entitled—”

8

officers of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human

Eights and/or the Southern Christian Leadership Con

ference, which seek to eliminate racial segregation through

constitutionally protected activities such as free speech and

picketing, through the courts, and other legal means (R.

260, 361, 385). An Alabama Department of Public Safety

investigator assigned to “racial” problems testified that

the organizations’ “ teachings have been non-violent” (E.

276), and “ the general theme is non-violence in every pro

gram” (E. 277).

Objecting to legally enforced racial segregation in the

City of Birmingham described above, these organizations

began a program of peaceful protests in April 1963 which

were part of the series described above. Some protests

took the form of sit-ins in the face of the Birmingham

ordinance requiring segregation in eating* establishments.9

Other protests took different form. Officers of the or

ganizations, aware that city officials might view some of

these protests as “ parades” requiring city permits,10 on

several occasions attempted to secure permits. Mrs. Lola

9 On April 5, 1963, several Birmingham Negro citizens seated them

selves at the lunch counter in Lane’s Drug Store, a business establish

ment open to the general public; the waitress asked if she could help

them and each ordered a cup of coffee. Shortly thereafter the manager

appeared with a city police officer who arrested them for “ trespass after

warning” (R. 113-114). A similar incident occurred the same day, when

four Negro citizens of Birmingham sought service at the Tutwiler Hotel

Coffee Shop (R. 115-116).

On April 9, several Negro citizens entered the Bohemian Bakery, a

business establishment open to the general public, obtained food in the

cafeteria line and seated themselves. Shortly thereafter the store manager

appeared with some city policemen. One officer said, “What should we

charge them with?” ; another answmred, “ Trespass” ; and another said,

“ Give them disorderly conduct, too.” Each member of the group was

ordered to rise and was searched; they were arrested and taken to city

jail (R. 116-117).

10 See text of §1159, General Code of City of Birmingham, supra, pp.

3-4.

9

Hendricks, a member of the Alabama Christian Movement

for Human Rights, authorized by its president, Rev. Shut-

tleswortk, on April 3, 1963, went to the Police Department

and asked to see the person in charge of issuing permits,

and was directed to Police Commissioner Eugene (“Bull” )

Connor’s office in City Hall. When Commissioner Connor

received her, she said, “We came up to apply or see about

getting a permit for picketing, parading, demonstrating,”

and asked if he could issue the permit, or refer her to

other persons who would issue it. Commissioner Connor

replied, “No you will not get a permit in Birmingham,

Alabama to picket. I will picket you over to the city jail.”

He repeated that twice (R. 418-421).

On April 5, Rev. Shuttlesworth, President, and N. H.

Smith, Secretary, of the Alabama Christian Movement,

sent a telegram to Police Commissioner Connor at City

Hall, requesting “ a permit to picket peacefully against the

injustices of segregation and discrimination in the gen

eral area of Second, Third and Fourth Avenues on the

east and west sidewmlks of 19th Street on Friday and Sat

urday April Fifth and Sixth. We shall observe the normal

rules of picketing. Reply requested” (R. 412-416, 484).

Commissioner Connor replied that he could not grant such

permits since this was the responsibility of the entire City

Commission and said, “I insist that you and your people

do not start any picketing on the streets in Birmingham,

Alabama” (R. 352-355, 484).

Petitioners offered to prove below that the City Com

mission never issued permits for parades or marches; that

these were, in fact, issued by the City Clerk at the request

of the Traffic Department without authority of statute or

ordinance (R. 344-348, 354). The Court, however, ruled

that since the law required action by the Commission, it

was not relevant to show whether the Commission in fact

10

followed the statutory procedure and refused to hear the

proof (R. 348-350).

On April 6, at about 12:30 P.M., about 42 persons left

the Gaston Motel in Birmingham and walked two abreast

towards the City Hall to petition the city government for

redress of grievances. They were orderly and obeyed all

traffic signals. Police officers stopped them and inquired

whether they had a parade permit. Upon answering “No”,

they were arrested for “parading without a permit” and

taken to the city jail (R. 112-113). April 7, at about 4

P.M., a similar incident occurred (R. 111-112). April 10,

at about noon, about ten Negro citizens walked together

towards City Hall carrying picket signs, intending to picket

peacefully to protest the city’s segregation policy. The

Chief of Police stopped them before they reached City

Hall, asked whether they had a permit to picket; upon say

ing they did not, he arrested them (R. 118-119).

Petitioners offered evidence below on the question of

how the permit statute was applied, to show that it was

being applied discriminatorily against them. However,

Chief Inspector W. J. Haley of the Birmingham Police

Department, was not allowed to answer the question “Isn’t

what is customarily known as parades something with

bands and signs and— !” (R. 234), or the question “ Have

you in your twenty-odd years of experience, yourself, do

you know of your own knowledge of any other group of

people similarly situated being arrested for parading with

out a license!” (R. 232). Inspector Haley had seen school

children marching in two’s to the auditorium or to the

museum or to the City Hall, but did not believe this con

stituted a parade and did not challenge them for parading

without a permit (R. 234). He implied that what made

petitioners’ processions “ parades” was that the leaders

(clergymen) were dressed in robes (R. 234). Haley stated

11

that some parades were considered “legal” in Birmingham,

but petitioners were not permitted by the court to ascer

tain what types of parades were allowed (R. 233).

C. The Injunction

On April 10, the City of Birmingham filed an ex parte

bill for injunction against petitioners in the Circuit Court

for the Tenth Judicial Circuit of Alabama, Equity Divi

sion, Jefferson County (R. 65-82). The City alleged that

from April 3 through April 10, petitioners sponsored and

participated in “ sit-in” demonstrations, “ trespasses” or

“ invasions” into the lunch counters of business establish

ments where food is served to customers, street proces

sions with the intent to march on City Hall without a

permit, and picketing places of business (R. 70-72), and

that one man in a crowd “ attacked a police dog of the City

of Birmingham, a member of the Canine Corps” (R. 72).

The City alleged that “ the present acts and conduct of

the respondents [petitioners] hereinabove alleged, is a part

of a massive effort by respondents [petitioners] and those

allied or in sympathy with them to forcibly integrate all

business establishments, churches, and other institutions

of the City of Birmingham” (R. 73).11

The bill for injunction was presented to W. A. Jenkins,

Jr., Circuit Judge of the Tenth Judicial Circuit of Ala

bama, without notice to petitioners, at 9 :00 P.M., April 10

(R. 65-84, 120); a temporary injunction immediately is

sued enjoining petitioners from:

11 The City also alleged, as the basis for injunctive relief, that “ the

said actions and conduct aforesaid are calculated to cause and if allowed

to continue will likely cause injuries or loss of life to Police Officers of

the City of Birmingham and have caused and will likely to continue to

cause damage to property owned by the City of Birmingham in the

operation of its Police Department and will continue to be an undue

burden and strain upon said Police Department” (R. 73).

12

Engaging in, sponsoring, inciting or encouraging mass

street parades or mass processions or like demonstra

tions without a permit, trespass on private property

after being warned to leave the premises by the owner

or person in possession of said private property, con

gregating on the street or public places into mobs, and

unlawfully picketing business establishments or public

buildings in the City of Birmingham, Jefferson County,

State of Alabama or performing acts calculated to

cause breaches of the peace in the City of Birmingham,

Jefferson County, in the State of Alabama or from

conspiring to engage in unlawful street parades, un

lawful processions, unlawful demonstrations, unlawful

boycotts, unlawful trespasses, and unlawful picketing

or other like unlawful conduct or from violating the

ordinances of the City of Birmingham and the Stat

utes of the State of Alabama or from doing any acts

designed to consummate conspiracies to engage in said

unlawful acts of parading, demonstrating, boycotting,

trespassing and picketing or other unlawful acts, or

from engaging in acts and conduct customarily known

as “kneel-ins” in churches in violation of the wishes

and desires of said churches (R. 76-77).

D. Continuation of Peaceful Protests Against

Segregation

After the City of Birmingham obtained the injunction,

petitioners Martin Luther King, Jr., Shuttles worth, Ab

ernathy and Walker issued a public statement (in the

form of a press release) on April 11, saying in part:

In our struggle for freedom we have anchored our

faith and hope in the rightness of the Constitution and

the moral laws of the universe. . . . However we are

now confronted with recalcitrant forces in the Deep

13

South, that will use the courts to perpetuate the un

just and illegal system of racial separation. Alabama

has made clear its determination to defy the law of

the land. Most of its public officials . . , have openly

defied the desegregation decision of the Supreme

Court. We would feel morally and legal responsible

to obey the injunction if the courts of Alabama ap

plied equal justice to all of its citizens. . . . We cannot

in all good conscience obey such an injunction which

is an unjust, undemocratic and unconstitutional mis

use of the legal process. We do this not out of any

disrespect for the law but out of the highest respect

for the law. . . . Out of our great love for the Constitu

tion of the U.S. and our desire to purify the judicial

system of the state of Alabama, we risk this critical

move with an awareness of the possible consequences

involved (R. 305-307, 482-483).

On Good Friday (April 12) and Easter Sunday (April

14) some of the petitioners participated in peaceful protest

demonstrations against segregation. On both occasions they

notified city police in advance to aid them in the perform

ance of their duties (R. 231, 235, 269-271) and police ap

peared at the protests (R. 406-407). Police did not permit

automobiles containing white persons, nor any white pe

destrians, to enter the predominantly Negro residential

area where the protest demonstrations were to begin (R.

210, 225).

On both Good Friday and Easter Sunday some of the

petitioners and about 50 to 60 others left church after mid

day services, walking in orderly fashion two by two on

the sidewalk. They had informed city officials that they

intended to proceed to City Hall. They were joined by sev

14

eral hundred others who had been permitted by the police

to congregate near the church (R. 209-210, 219, 223, 231,

235, 262-263, 284-285). Those who came from church

walked in columns of two’s; those who joined them were

not in columns but walked abreast, children in front, older

people behind (R. 225). No band played, nor were there

any uniformed persons among the walkers (R. 330-331),

nor were there any placards (R. 230). They did not cross

against red lights or violate traffic regulations (R. 216).

Police described them as orderly, and said that at all times

they had the situation under control; and that law and

order were maintained (R. 216, 219, 238, 332, 357).

On both occasions persons in the walk from the churches

including petitioners, were arrested within a few blocks

of the church, and charged with parading without a permit

in violation of §1159.

E. Contempt Judgment: How the Federal Questions

Were Raised and Decided Below

On April 15, petitioners filed a “motion to dissolve in

junction and/or application for stay of execution pending

hearing,” in which they asserted that the injunction denied

them due process of law under the Fourteenth Amendment

because it was issued without notice to them, because it

was excessively vague, because it was a prior restraint on

free speech protected by the First Amendment, because it

was designed to enforce segregation, because it was based

upon a complaint which described only constitutionally pro

tected conduct, and because the ordinance upon which it

was based was excessively vague (R. 100-119). Petitioners

also filed a demurrer (R. 176-178), an answer (R. 178-180),

and an amended answer (R. 186-189) to the bill for in

15

junction in which they raised similar constitutional claims.

After petitioners filed their motion to dissolve the injunc

tion, the City of Birmingham filed a motion for an order

to show cause why petitioners should not be held in con

tempt for violating the ex parte temporary injunction (R.

119-144). The court ruled that even though petitioners had

filed their motion to dissolve first, it would consider the

City of Birmingham’s show cause order for contempt first

(R. 194-195).

In response to the City of Birmingham’s show cause

order for contempt, petitioners filed a “motion to discharge

and vacate order and rule to show cause” saying that they

had not violated the injunction because it prohibited en

gaging in or encouraging others to eng*age in “unlawful”

conduct specified therein, whereas the petitioners’ conduct

was lawful conduct protected by the First Amendment and

the due process and equal protection clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Petitioners also said that the original bill for injunction

upon which the temporary injunction was based did not

show that they had engaged in unlawful conduct but that

they had engaged in conduct protected by the First and

Fourteenth Amendments (R. 181-182).

In their answer to the show cause order, petitioners de

scribed the lawful conduct protected by the First and

Fourteenth Amendments in which they had engaged:

a) Walking two abreast in orderly manner on the pub

lic sidewalks of Birmingham observing all traffic regu

lations with prior notice having been given to city

officials in order to peacefully express their protest

against continuing racial discrimination in Birming

ham.

16

b) Peaceful picketing in small groups and in orderly

manner of publicly and privately owned facilities.

c) Requesting service in privately owned stores open

to the general public in exercise of their right to equal

protection of the laws and due process of law which

are denied by Section 369 of the 1944 General City

Code of Birmingham (R. 184-185).

At the contempt hearing petitioners offered evidence on

the issue of what constituted activity falling within the ban

on parading without a permit, to show that this rule was

applied discriminatorily against petitioners in violation

of their rights to equal protection under the Fourteenth

Amendment. The court excluded the evidence, saying “I

think the only question was did they or did they not have a

permit” (R. 232-234).

Petitioners also offered evidence that they requested a

“parade” permit which was denied arbitrarily, in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment. This was excluded on the

ground that they had not followed the statutory procedure

for obtaining permits (R. 420-421).

Petitioners offered to prove that the statutory procedure

was in fact never followed, and that it would be a denial

of equal protection of the laws secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment to require petitioners to follow it (R. 344-348,

354). The Court ruled this was not relevant, and refused

the offer (R. 348-350). The Court refused an offer of proof

that there were no published rules and regulations pre

scribing the manner in which permits are actually ob

tained (R. 350).

Petitioners offered to prove that parade permits were

freely given to white persons under similar circumstances

and for similar activities, which denied petitioners’ Four

17

teenth Amendment rights. The court refused this offer

(R. 344-355, 232-234).

Petitioners offered to prove that the purpose of their

activities was to protest against unconstitutional racial

discrimination by exercising the right of free speech pro

tected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments; this was

refused (R. 360).

After presentation of the City of Birmingham’s evidence

during the hearing on the show cause order, petitioners

filed a “motion to exclude testimony against all respon

dents [petitioners]” (R. 190-191) in which they asserted

that there was no evidence showing why they should be

punished for contempt based on “ the statements made pub

licly at press conferences and mass meetings on April 11,

1963,” since the evidence showed that they had “ engaged

only in activity protected by the First Amendment and

by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States.” Petitioners T.

L. Fisher and J. W. Hayes asserted that there was no evi

dence showing that they were served with copies of the

court’s injunctive order of April 10, 1963, prior to their

arrest and imprisonment for parading without a permit on

April 12 or April 14, 1963 (R. 191).

The court said that the basis of the show cause order,

charging contempt, was the issuance of the press release

containing allegedly derogatory statements about Alabama

courts and, particularly, the injunctive order of that court,

and petitioners’ participation in alleged parades in viola

tion of the permit ordinance (R. 475-476). In response to

petitioners’ claim that their acts were lawful because con

stitutionally protected by the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments, and that the order enjoining peaceful protests was

void because it enforced Section 369 of the 1944 Code of

Birmingham requiring segregation in eating facilities, the

18

Court said the parade ordinance “is not invalid upon its

face as a violation of the constitutional rights of free

speech as afforded to these defendants in the absence of

a showing of arbitrary and capricious action upon the part

of the Commission of the City of Birmingham in denying

the defendants a permit to conduct a parade” (R. 476-

478). The Court held petitioners in contempt (R. 478)

and sentenced them to 5 days in jail and $50 fines (R. 480).

In petition for certiorari to the Supreme Court of Ala

bama, petitioners made substantially the same claims as

below, asserting that the judgment of contempt denied

rights secured by the First and Fourteenth Amendments

in that the punishment constituted a prior restraint on

freedom of speech, association, and the right to petition

for redress of grievances; that the injunction was exces

sive and vague, contrary to the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, particularly in the context of an

order restraining First Amendment rights; and that the

City of Birmingham failed to produce evidence which

showed that petitioners did anything other than exercise

constitutional rights of free expression, and that, there

fore, the contempt decree was based on no evidence of

guilt, in violation of the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment (R. 24).

The Alabama Supreme Court held that because peti

tioners admittedly continued protest demonstrations after

the injunction issued, they violated the order against en

gaging in parades without permit (R. 512-514). The Court

said, “ Petitioners rest their case on the proposition that

Section 1159 of the General City Code of Birmingham,

which regulates street parades, is void because it violates

the First and Fourteenth Amendments of the Constitution

of the United States, and, therefore, the temporary in

junction is void as a prior restraint on the constitutionally

19

protected rights of freedom of speech and assembly” (R.

515). The Court held that “the circuit court had the duty

and authority, in the first instance, to determine the va

lidity of the ordinance, and, until the decision of the cir

cuit court is reversed for error by orderly review, either

by the circuit court or a higher court, the orders of the

circuit court based on its decision are to be respected and

disobedience of them is contempt of its lawful authority,

to be punished,” and therefore affirmed petitioners’ con

victions for contempt (R. 522).

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

Petitioners’ rights under the due process and equal

protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment were

infringed by their conviction for contempt where the

injunction they are charged with disobeying is in viola

tion of their First and Fourteenth Amendment rights.

Petitioners contend that suppressing their protests

against racial segregation violated constitutional guaran

tees. The ex parte injunctive order of April 10, 1963

(R. 76-77), the city ordinance prohibiting parades with

out permits which underlies the injunction (General City

Code, 1944, Section 1159, supra, pp. 3-4), and the judg

ment of contempt (R. 475-480), violated First and Four

teenth Amendment guarantees of free speech and assembly.

The case presents important issues of free assembly, speech

and petition for redress of grievances in the context of

the total racial segregation policy of Birmingham in 1963.

This Court has reviewed other cases involving similar ques

20

tions and has recognized the public importance of the is

sues.12

The case comes here three years after the events because

the Alabama Supreme Court kept it under advisement from

August 22, 1963 (R. 499), until December 9, 1965. But the

use of state court injunctive and criminal process to sup

press peaceable assembly continues to present public ques

tions of first importance.

The trial court rejected petitioners’ constitutional at

tack on the injunction and the parade permit ordinance on

the merits (R. 477-478), and held petitioners in contempt

for disobedience of an order enjoining “unlawful parades”

and parades without permits provided for in City Code

§1159. (The trial court also apparently found some peti

tioners in contempt for issuing a statement at a press

conference which was allegedly disrespectful and in defiance

of the court’s authority. See part III, infra.)

On certiorari the Alabama Supreme Court held that

petitioners might be punished for disobeying the injunction,

whether or not the injunction violated their constitutional

rights, relying upon its interpretation of United States v.

United MineworJcers, 330 U.S. 258 (20a-25a). With that

view of the law, the court found it unnecessary to discuss

the validity of the injunctive order and constitutional

objections pressed by petitioners. Nor did the court below

mention petitioners’ defense that their conduct did not

violate the injunction because the order prohibited “un

lawful parades” and their conduct was not “unlawful,”

but was constitutionally protected.

12 Between 1961 and 1965, this Court passed on more than 30 eases

involving sit-in demonstrations. During recent years the Court also

passed on numerous cases involving protest marches as in Edwards V.

South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229, and Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536.

21

In the discussion which follows, we first urge that the

injunctive order of April 10, 1963, and §1159 are both un

constitutional and violate petitioners’ constitutional rights

to free speech and assembly on various grounds including

Fourteenth Amendment vagueness and equal protection

claims. Second, we urge that there was no evidence of an

“unlawful” parade forbidden by the injunction, and hence

no evidence of guilt within the doctrine of Thompson v.

Louisville, 362 U.S. 199, and Fields v. City of Fairfield, 375

U.S. 248. Third, we argue that even assuming, arguendo,

that petitioners did disobey the injunction, the state may

not constitutionally punish disobedience of an ex parte in

junctive order which infringes constitutional rights to

free speech and assembly.

A. The ex parte injunction o f April 10, 1963, and

Section 1159 o f the Birm ingham City Code violate

petitioners’ First and Fourteenth Amendment rights.

1. Vagueness of the Injunction’s Terms.

The April 10, 1963, injunction undertook to end all Negro

protest against the segregationist regime of Birmingham.

The order was issued without notice or hearing on the

basis of the City’s complaint verified by Public Safety

Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, and affidavits of

several policemen describing certain demonstrations against

discrimination. In broad and sweeping language the order

undertook to prohibit, inter alia, parades without permits,

trespasses after warning, “unlawfully picketing business

establishments or public buildings,” “unlawful boycotts,”

and “performing acts calculated to cause breaches of the

peace in the City of Birmingham” (R. 76-77).

I f this case requires review of all the injunction’s pro

hibitions there should be no doubt of its invalidity. For

example, the anti sit-in demonstration provision directly

22

aided the City ordinance compelling restaurant segregation

which this Court referred to in invalidating convictions

in Gober v. Birmingham, 373 U.S. 374, and Shuttlesworth

and Billups v. Birmingham, 373 U.S. 262. The general

prohibition against “Acts calculated to cause breaches of

the peace” is plainly a vague and overbroad infringement

of free speech and assembly. Edwards v. South Carolina,

372 U.S. 229; Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U.S. 44; Henry

v. Rock Hill, 376 U.S. 776; and Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S.

536, 544-552.

But the trial court apparently based its contempt find

ing only on an alleged violation of the portions of the in

junction prohibiting certain petitioners13 “ from engaging

in, sponsoring, inciting, or encouraging mass street parades

or mass procession or like demonstrations without a per

mit” and from “ conspiring to engage in unlawful street

parades, unlawful processions, unlawful demonstrations . . .

or other like unlawful conduct or from violating the ordi

nances of the City of Birmingham and the Statutes of the

State of Alabama . . . ” . The trial court never stated pre

cisely what portion of the order it thought was violated,

but rests on the conclusion that petitioners conducted al

parade without a permit as well as upon alleged disrespect

ful remarks at a press conference. There was no apparent

reliance upon any theory that petitioners violated the

order by any means other than parading without a per

mit (R. 360):

The Court: The only chargn has been this particular

parade, the one on Easter Sunday and the one on

18 Petitioners J. W. Hays and T. L. Fisher were not named as respon

dents in the injunction suit, named in the injunction order, or served with

copies of the injunction prior to the alleged violation of the order. The

separate arguments addressed to this situation are set forth below at

pp. 42 to 44.

Good Friday, and on the question of the meeting at

which time some press release was issued. Am I cor

rect in that?

Mr. McBee: Essentially that is correct.

The Court: I don’t know of any other evidence or any

other occasions other than those, and I see no need

of putting on testimony to rebut something where

there has been no proof along that line.

The Alabama Supreme Court quotes this statement and

says that petitioners did parade or march without a permit

contrary to the order (17a-18a).

The order is vague and overbroad insofar as it merely

enjoins “unlawful” parades and demonstrations. A gen

eral prohibition against “unlawful” parades requires those

enjoined to determine at their peril the lawfulness of a

proposed parade by reference to the wThole body of the law,

including applicable constitutional provisions. Where the

only guideline is the Constitution those enjoined are left

to gauge the full range of legal and factual issues neces

sary to a decision of whether a particular parade is con

stitutionally protected. An injunction making the constitu

tional boundary the line of criminality is obnoxious to all

the objections which have led this Court to void statutes

which encroached overbroadly on constitutionally pro

tected conduct. First, because the constitutional boundary

is obscure and often presents a difficult question, the in

junction gives no fair notice, “no warning as to what may

fairly be deemed to be within its compass.” Mr. Justice

Harlan, concurring in Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157,

185, 207; see Note, Amsterdam, The Void-for-Vagueness

Doctrine in the Supreme Court, 109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 67, 76

(1960), and authorities cited in footnote 51. Second, such

a vague proscription is readily susceptible of harsh, im

24

proper and discriminatory enforcement. Cf. N.A.A.C.P. v.

Button, 371 U.S. 415, 433; Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S.

88, 97-98. Lastly, such an order effectively coerces the

citizen to surrender his right to engage in protected pro

test through fear of punishment for contempt, and thus

inhibits free expression. See Thornhill v. Alabama, 310

U.S. 88, 97-98; Smith v. California, 361 U.S. 147, 150-151;

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U.S. 278, 286-

288; Bantam Boohs, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58, 66-70;

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360, 378-379; Dombrowshi v.

Pfister, 380 U.S. 479, 494.

This general prohibition against “unlawful” parades

and demonstrations presents essentially the same question

presented by prosecutions under generalized conceptions

of breach of the peace in Edwards v. South Carolina, 372

U.S. 229; Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U.S. 44; Henry v.

Rock Hill, 376 U.S. 776; and Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S.

536, 544-552. In each case the Court made clear that free

speech and assembly may be regulated only by precise

and narrowly drawn rules. See also Cantwell v. Connecti

cut, 310 U.S. 296; Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1;

Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S. 359; Ashton v. Kentucky,

____ U.S.......... (May 16, 1966, 34 U.S. Law Week 4398).

And, of course, the fact that the vague proscription ema

nates from a sweeping judicial edict rather than from a

vague legislative enactment cannot save it, because the pro

tections of the Fourteenth Amendment apply with equal

force to the judiciary. N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415;

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U.S. 516; cf. Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 U.S. 1; Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U.S. 61; Hamilton v.

Alabama, 376 U.S. 650; N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U.S.

449, 462.

25

2. The Unconstitutionality of §1159 on Its Face and as

Applied.

The injunction’s prohibition against parades “without

permits” is equally invalid because the applicable permit

requirement is in Birmingham City Code §1159 which is

unconstitutional on its face, and as applied. Indeed, the

Alabama Court of Appeals has held §1159 unconstitutional

in a criminal proceeding arising from the same Good Fri

day walk involved in this case. See Shuttlesworth v. City

of Birmingham,.......Ala. App..........., 180 So.2d. 114 (1965),

(cert, granted by Ala. Sup. Ct., January 20, 1966). Judge

Cates wrote that the conviction was invalid on several dis

tinct grounds, viz., because §1159 imposed an invidious

prior restraint on free use of the streets; because it lacked

ascertainable standards for granting or denying permits;

because it was discriminatorily applied contrary to Yick

Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356; and because there was in

sufficient evidence that §1159 was violated by the Good

Friday walk on the sidewalks. The City’s appeal from that

decision is now pending in the Alabama Supreme Court,

but the invalidity of §1159 under a host of this Court’s

decisions is plain.

The ordinance plainly fails to provide meaningful and

constitutional standards for granting or denying permits

and commits the decision of the right to peaceful use of

the streets for protest to the uncontrolled discretion of

the licensing officers. Pursuant to §1159 the Birmingham

City Commission should grant a permit “unless in its judg

ment the public welfare, peace, safety, health, decency,

good order, morals or convenience require that it be re

fused.” The ordinance requires that the applicant state

“ the purpose for which it [any parade, procession or other

public demonstration on the streets] is to be held or had.”

Thus, by committing to the commissioners the right to

26

decide, in view of the purpose of a demonstration, whether

the “public welfare,” etc., will be served, the Commis

sioners are empowered to suppress any protest they dis

approve of. The law is unconstitutional on its face under

this Court’s decision in Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536,

553-558, and the precedents cited therein. As the Court

stated in Cox, supra, 379 U.S. at 557-558:

It is clearly unconstitutional to enable a public official

to determine which expressions of view will be per

mitted and which will not or to engage in invidious

discrimination among persons or groups either by use

of a statute providing a system of broad discretionary

licensing power or, as in this case, the equivalent of

such a system by selective enforcement of an extremely

broad prohibitory statute.

See also, Schneider v. State, 308 U.S. 147, 163-164; Lovell

v. Griffin, 303 U.S. 444, 447, 451; Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S.

496, 516; Largent v. Texas, 318 U.S. 418, 422; Saia v. New

York, 334 U.S. 558, 559-560; NiemotJco v. Maryland, 340

U.S. 268, 271-272; Kuns v. New York, 340 U.S. 290, 294;

and Staub v. Baxley, 355 U.S. 313, 322-325. Cf. Shuttles-

worth v. Birmingham, 382 U.S. 87, 90; Freedman v. Mary

land, 380 U.S. 51, 56.

Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U.S. 569, cited by the trial

court, is distinguishable from this case. For in Cox there

were no “licensing systems which vest in an adminis

trative official discretion to grant or withhold a permit

upon broad criteria unrelated to proper regulation of pub

lic places.” Kuns v. New York, 340 U.S. 290, 293-294.

And, of course, the Court has “ uniformly held that the

failure to apply for a license under an ordinance which on

its face violates the Constitution does not preclude review

27

in this Court of a judgment of conviction under such an

ordinance.” Staub v. Baxley, 355 U.S. 313, 319.

The Alabama Court of Appeals has held that §1159 was

discriminatorily applied in reversing the prosecution of pe

titioner Shuttlesworth for the Good Friday 1963 march.

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham,.......Ala. App...........,

180 So.2d 114, 136-139 (1965). After analyzing the record

in that case and in other prosecutions under the law (in

particular, Primm v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala. App, 657,

177 So.2d 326 (1964)), Judge Cates concluded that the

“ pattern of enforcement exhibits a discrimination within

the rule of Tick Wo v. Hopkins, supra” (180 So.2d at 139).

In this contempt proceeding, petitioners made repeated

efforts to prove their claim of discriminatory enforcement

in violation of the equal protection clause. (See infra,

pp. 29 to 30). The trial court refused to admit much

of the testimony. However, a sufficient showing was made

to establish a violation of the equal protection clause in the

administration of §1159.

Some parades were considered “legal” and allowed in

Birmingham, although the trial court would not allow peti

tioners to develop what type of parades were permitted

(ft. 233). Repeated efforts of civil rights demonstrators

to obtain permits were rebuffed, although the authorities

were advised of their plans by the demonstrators them

selves (R. 231, 235, 269, 271) and by police investigators

(R. 219-221). When representatives of Rev. Shuttlesworth

went to see the person in charge of issuing permits for pa

rading, picketing and demonstrating they were referred to

Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor. Mrs.

Lola Hendricks told Connor “We came up to apply or see

about getting a permit for picketing, parading, demon

strating” (R. 420), and “asked if he could issue the permit”

28

or refer her to “persons who would issue a permit.” Mr.

Connor replied by stating:

No, you will not get a permit in Birmingham, Alabama

to picket. I will picket you over to the City Jail

(R. 420).

This evidence is sufficient to invalidate the ordinance and

the convictions. Cf. Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267.

Two days later, Rev. Shuttlesworth sent a telegram to

Mr. Connor (R. 484), requesting a permit to picket (R.

484). Mr. Connor wired back that a permit “ cannot be

granted by me individually but is the responsibility of the

entire commission,” and then added: “I insist that you

and your people do not start any picketing on the streets

in Birmingham, Alabama” (R. 484).

Mr. Connor’s statement to Mrs. Hendricks plainly es

tablishes an arbitrary and capricious administration of the

permit law. The refusal to receive an application for a

permit or to furnish her with information other than the

statement that picketing would not be permitted plainly

shows the operation of uncontrolled and abused discre

tionary power. Mr. Connor did not even seek from Mrs.

Hendricks any information as to the time and place of

proposed demonstrations, the number of participants or

any information relevant to any permissible factors in de

ciding a permit request. Immediately when confronted

with a representative of the Alabama Christian Movement

for Human Rights, Connor rejected the request.

As Mr. Justice Black wrote concurring in Cox v. Loui

siana, supra, 379 U.S. at 580-581:

I believe that the First and Fourteenth Amendments

require that if the streets of a town are open to some

views, they must be open to all.

* # #

29

And to deny this appellant and his group use of the

streets because of their views against racial discrimi

nation, while allowing other groups to use the streets

to voice opinions on other subjects, also amounts, I

think, to an invidious discrimination forbidden by the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

See also, the concurring opinion of Mr. Justice Clark in

Cox, supra, 379 U.S. at 589. Under the regime of Eugene

“Bull” Connor the streets of Birmingham were “ open to

some views,” but not open to all. The ordinance as applied

denied equal protection.

3. Improper Exclusion of Evidence on the Unconstitutional

Application of %1159.

Petitioners’ various proffers of evidence which the trial

court refused to hear demonstrate even more conclusively

that the ordinance was not fair in its application. Indeed,

petitioners offered to prove that the procedure specified by

§1159 was never followed, that the city commission never

issued permits under §1159 and that this function cus

tomarily was performed by the City Clerk at the request

of the Traffic Department without any statutory authority

(R. 344-354). It was established that there were no pub

lished rules or regulations other than §1159 (R. 350). How

ever, the trial court would not permit witnesses to answer

whether the city commission had ever voted on issuance of

permits (R. 347).

If the Court should believe that the evidence is insuf

ficient to establish an unconstitutional administration of

the ordinance, petitioners are at the least entitled to an

opportunity to prove the facts at a new hearing. The trial

court’s conclusion that there was an “absence of a show

ing of arbitrary and capricious action upon the part of

30

the Commission of the City of Birmingham in denying the

defendants a permit to conduct a parade on the streets . . . ”

was patently erroneous in view of the refusal to hear evi

dence on the subject. The exclusion of such evidence was

in itself a denial of due process of law to petitioners. Cf.

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 129, 133; Carter v. Texas,

177 U.S. 442, 448-449.

B. The conviction denied due process because there

was no evidence petitioners participated in a for

bidden “ unlawful” parade or demonstration.

This Court has made it plain in Thompson v. Louisville,

362 U.S. 199, and in subsequent cases applying its rule, that

a conviction where there is no evidence of guilt denies due

process. See Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157; Fields v.

City of Fairfield, 375 U.S. 248; Taylor v. Louisiana, 370

U.S. 154; Barr v. City of Columbia, 378 U.S. 146; Shuttles-

worth v. Birmingham, 382 U.S. 87, 93-95. Fields v. Fair-

field, supra, makes clear that this applies as much to a con

tempt prosecution as to other criminal charges. In such

cases the Court has ascertained the elements of criminal

ity and examined the record to determine if there was any

evidence of guilt. Here petitioners were enjoined against

“unlawful” parades in violation of the Birmingham parade

ordinance. To sustain a conviction, the State was bound to

prove that petitioners knowingly participated in an “ unlaw

ful” parade.

There was no proof that the parades were unlawful. The

arguments set forth in Part IA, above, pp. 25 to 29,

demonstrate the invalidity of the permit requirement of

§1159 on its face and as applied, as well as the vagueness

of the injunction against “unlawful” parades and demon

strations. And, of course, there was no evidence, and there

could have been no evidence, that petitioners knew the

31

demonstrations were unlawful. There has never been any

suggestion that the parades were unlawful except by

reference to the permit requirement of section 1159. The

constitutional invalidity of that provision undermines any

possible claim that the petitioners knowingly violated the

injunction’s prohibition against “unlawful” parades.

Neither was there any evidence that petitioners partici

pated in any parade for which a permit was required under

§1159. The Alabama judicial construction of §1159 as ap

plied to the very same Good Friday events involved in

this case is that the mere presence of a group walking

together on the sidewalks, obeying traffic regulations and

not walking on the roadway does not require a permit.

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham,..... . Ala. App....... - ,

180 So.2d 114, 139 (1965) (pending on certiorari). Judge

Cates concluded that the proof “ fails to show a procession

which would require, under the terms of §1159, the getting

of a permit.”

The same conclusion follows with respect to petitioners

who participated in the Easter Sunday march. They, too,

were walking on the sidewalks, and obeyed traffic signals.

On both occasions police blocked off traffic and had large

numbers of officers present and in control of spectators

whom the police permitted to gather. And on both occasions

members of the crowd of spectators followed the people

who came out of the church. The conviction is based on

no evidence of guilt because there was no prohibited ‘ un

lawful” parade, and no parade in violation of the permit

requirement of §1159 as construed by the Alabama Court

of Appeals.

The Alabama Supreme Court relies upon a supposed

admission in petitioners’ brief in the court below (18a-

19a). The brief said only that after the injunction peti

32

tioners continued their participation in “protest demonstra

tion.” There was no admission that petitioners participated

in a prohibited “unlawful” parade or demonstration or that

they violated a valid permit requirement. To the contrary,

petitioners’ brief argued at length that their conduct was

constitutionally protected and that there was no evidence

of their guilt under the doctrine of Thompson v. Louisville,

362 U.S. 199.

I f the Court should determine that there was no evidence

that petitioners violated the injunction, it will be unneces

sary to decide whether a court may validly punish violation

of an unconstitutional ex parte injunction. Fields v. City

of Fairfield, 375 U.S. 248.

II.

Assuming arguendo that petitioners did disobey the

injunction, Alabama may not validly punish them be

cause the ex parte injunction was void as an unconstitu

tional infringement of their rights to free speech and

assembly.

The opinion of the Alabama Supreme Court holds that

United States v. United Mine Workers, 330 U.S. 258, per

mits punishment by criminal contempt for the violation

of an ex parte injunction without regard to the constitu

tionality of the injunctive decree. Indeed, the court below

(unlike the court in Mine Workers) did not even discuss

whether or not the injunctive order was valid.

The case thus presents the grave question, whether citi

zens may be jailed for disobeying an ex parte injunctive

order which violates their constitutionally protected rights

to free speech, peaceable assembly and petition for the

redress of grievances. This is a question of paramount

33

importance. Its decision may well determine whether the

First Amendment freedoms will have continued vitality.

This Court recognized the gravity of this question by

granting certiorari in a similar Alabama case and inviting

the United States to participate and argue the cause orally

as amicus curiae. Fields v. City of Fairfield, 375 U.S. 248.

In Fields, the court found it unnecessary to decide this

issue which had been thoroughly briefed and argued.14 15

More recently, in Donovan v. Dallas, 377 U.S. 408, 414, in

volving the power of states to deny access to the federal

courts, the Court expressly declined to pass on whether dis

obedience of an invalid order could be punished, because

the issue had not been previously considered by the state

court. We read the Donovan case as at least a partial con

firmation of our view, urged in detail below, that the ques

tion is not foreclosed by Mine Workers, supra.

First Amendment freedoms can be destroyed if citizens

may be punished for disobeying ex parte injunctive decrees

which violate the First Amendment. The proposition is so

plain that it requires no elaborate analysis to demonstrate

its validity. Plainly, some courts will use the injunctive

power to suppress free expression of unpopular ideas.16

14 Fields v. City of Fairfield, No. 30, Oct. Term, 1963, Brief for Appel

lants, pp. 21-36; Brief for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc. as amicus curiae urging reversal, passim; Brief for the United

States as amicus curiae urging reversal, pp. 11-13. The United States

pointed out in its brief (at pp. 12-13, n. 19) :

It is, of course, well settled that failure to apply for a permit

under a licensing statute does not bar a subsequent attack on its

constitutionality. Smith v. Cahoon, 283 U.S. 553; Lovell v. Griffin,

303 U.S. 444; Staub v. City of Baxley, 355 U.S. 313. By a parity

of reasoning, it may be argued that one should not be compelled to

apply for the dissolution of a plainly invalid judicial decree in order

to preserve the question of its constitutionality upon conviction for

disobeying it.

15 See for example N.A.A.G.P. v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449; id., 360 U.S.

240 ; id., 377 U.S. 288; Congress of Racial Equality v. Douglas, 318 F.2d

95 (5th Cir. 1963).

34

Plainly, the power to enforce unconstitutional law is the

power to govern unconstitutionally. We do not believe that

the power of courts to defend their dignity requires or

permits the power to destroy or “whittle away” the First

Amendment. Cf. Re Oliver, 333 U.S. 257, 278.

The Mine Workers’ decision should be distinguished,

limited to its non-constitutional context, or overruled. The

result in Mine Workers did not depend on the view that

void orders must be obeyed, because five members of the

Court held the injunction valid.16 There was no claim in

Mine Workers that the injunctive order was unconstitu

tional or affected free speech rights; the possible applica

tion of the rule against disobeying invalid orders to con

stitutional claims was discussed only by the dissenters

(330 U.S. at 352). The principal precedent relied on for

the Mine Workers rule (United States v. Shipp, 203 U.S.

563),17 was a case where the judicial order was plainly

valid, and where there was no tenable claim that the court

order violated the contemnor’s First Amendment or other

constitutional rights.

16 In United States v. United Mine Workers, 330 U.S. 258, the opinion

of the Court, by Chief Justice Yinson (joined by Justices Reed and

Burton) held the injunction valid and stated as an alternative ground

that disobedience of non-frivolous orders could be punished. Justices

Black and Douglas concurred, solely on the ground that the injunction

was valid without deciding whether violation of void orders might be

punished. Justices Jackson and Frankfurter held the order invalid but

agreed with C. J. Vinson and Justices Reed and Burton that invalid or

ders could be enforced by criminal contempt. Justices Murphy and

Rutledge dissented on the ground that the order was invalid and that

invalid orders might not be enforced by contempt.

Thus, the contempt judgment was affirmed by a 7-2 vote. Five justices

thought the order valid, four thought it invalid. Five thought invalid

orders might be enforced by contempt; two justices disagreed; and two

expressed no view.

17 Worden v. Searls, 121 U.S. 14, also cited in Mine Workers, was not

a criminal contempt case.

35

This Court has said that “ First Amendment freedoms

need breathing space to survive.” N.A.A.C.P. v. Button,

371 U.S. 415, 433. A “ system of prior restraints of ex

pression comes to this Court bearing a heavy presumption

against its constitutional validity,” Bantam Boohs, Inc. v.

Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58, 70. See Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S.

697; Thomas v. Collins, 323 U.S. 516; Freedman v. Mary

land, 380 U.S. 51. Ex parte injunctive orders restraining

free expression without any adversary contest of factual or

legal issues determinative of constitutional claims, impose

prior restraints totally devastating to the right of free ex

pression. They should be treated with the same suspicion

accorded to administrative prior restraints. Cf. Freedman

v. Maryland, 380 U.S. 51, 57-59. A rule that forbids chal

lenge of ex parte injunctions in contempt proceedings,

despite their unconstitutionality, creates a prior restraint

effectively immunized from challenge.

The undeniable effect of the rule stated by the court below