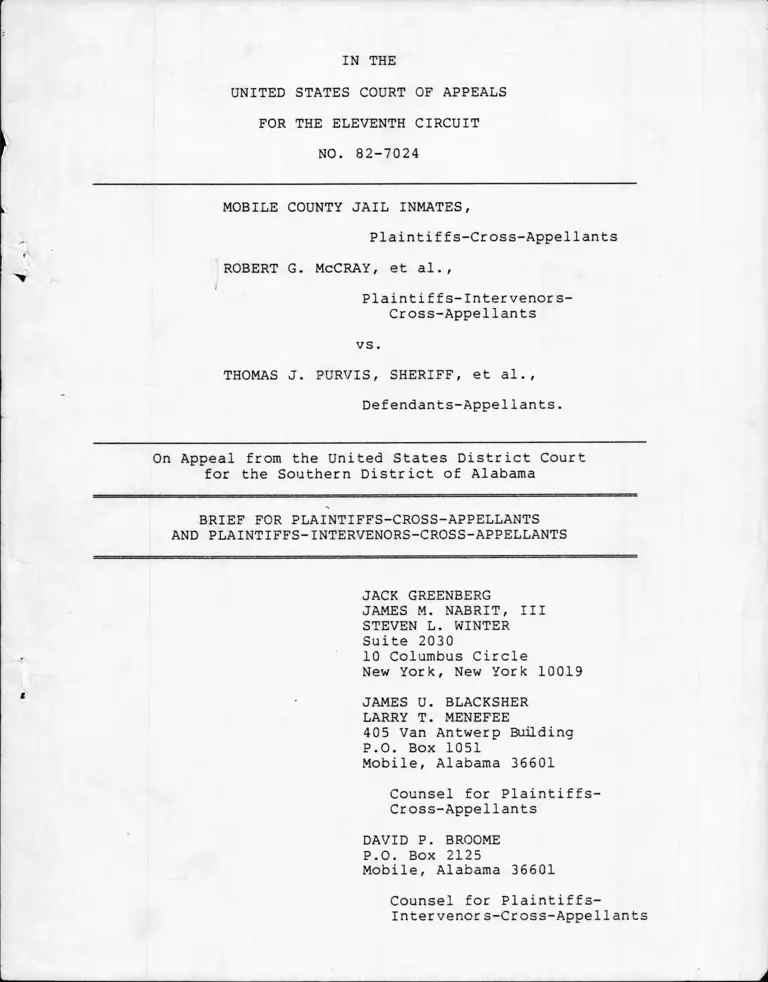

Mobile County Jail Inmates v. Purvis Brief for Plaintiffs-Cross-Appellants and Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Cross-Appellants

Public Court Documents

May 19, 1982

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mobile County Jail Inmates v. Purvis Brief for Plaintiffs-Cross-Appellants and Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Cross-Appellants, 1982. 2d61cf11-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b49c2518-75ae-4289-91a1-69041bcc2a92/mobile-county-jail-inmates-v-purvis-brief-for-plaintiffs-cross-appellants-and-plaintiffs-intervenors-cross-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

NO. 82-7024

MOBILE COUNTY JAIL INMATES,

Plaintiffs-Cross-Appellants

ROBERT G. McCRAY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-

Cross-Appellants

v s .

THOMAS J. PURVIS, SHERIFF, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Alabama

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-CROSS-APPELLANTS

AND PLAINTIFFS-INTERVENORS-CROSS-APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

STEVEN L. WINTER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JAMES U. BLACKSHER

LARRY T. MENEFEE

405 Van Antwerp Building

P.O. Box 1051

Mobile, Alabama 36601

Counsel for Plaintiffs-

Cross-Appellants

DAVID P. BROOME

P.O. Box 2125

Mobile, Alabama 36601

Counsel for Plaintiffs-

Intervenors-Cross-Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PARTIES

The undersigned certifies that the following have an

interest in this appeal:

Britt Mose Lovett, Jr., Robert G. McCray, Ollie

McKinnis, Jr., Leon G. Allen, and the inmates of

the Mobile County Jail.

J. U. Blacksher, Larry T. Menefee, Gregory Stein,

Blacksher, Menefee and Stein, P.A.

David P. Broome, Gallalee, Denniston & Cherniak.

W. Clint Brown.

Steven L. Winter, NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

Stanley A. Bass, Queens Legal Services.

Thomas J. Purvis, Sheriff.

Dan Wiley, John Archer, and Douglas Wicks, Mobile

County Commissioners.

Joseph S. Hopper, Robert G. Britton, Forrest James,

State of Alabama.

Steven L. WinterCounsel for Plaintiffs-Cross-

Appellants

STATEMENT REGARDING PREFERENCE

This case is not entitled to preference.

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Cross-Appellants respectfully submit that this case

requires oral argument. It presents questions critical to

the effective implementation of the Civil Rights Attorneys'

Fees Awards Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. § 1988 ("the Act"). The

outcome of this appeal will affect not just the parties

listed above but, indirectly, every future civil rights

litigant who cannot afford counsel.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Statement of Issues .................................... 1

Statement of the Case .................................. 2

A. The Proceedings Below ........................ 2

B. Conditions at the Mobile County Jail ....... 6

C. The Fees Hearing ............................. 6%

Summary of Argument .................. 18

Statement of Jurisdiction ............................. 20

Argument ............................................... 20

I. This Court Must Review the Lower Court's

Subjective Application of the Johnson

Factors and Provide a Uniform and Objective

Method for Their Application of the Basic

Policy of the Fees Act Is Not to Be

Subverted ..................................... 20

II. In Setting Hourly Rates, the Lower Court Misapplied the Johnson Factors— Including

Those Relating to Contingency, Undesir

ability, and Length of Professional

Relationship— Resulting in Fees Below Market

Rates for Traditional, Non-Contingent, Civil

Litigation .................................... 23

A. Application of the Johnson Factors

in the Manner Congress Intended

Would nave Resulted in Substan

tially Higher Fees ....................... 23

B. The Hourly Rates Awarded Do Not Reflect

Defendants' Evidence Regarding Non-

Contingent Rates When Adjusted by the

Length of Professional Relationship

Factor .................................. 25

C. The District Court Misapplied the

Contingency Factor in Failing to

Properly Evaluate the Contingent

Nature of this Litigation and in

Failing to Award Rates that Reflect

the Economic Effects of the Contingent

Nature of Counsel's Compensation ........ 27

-i-

Page

D. The Lower Court Erred in Not Applying

the Undesirability Factor to Increase

the Award ...........................

E. A Proper but Conservative Application

of the Johnson Factors Would Result

in Fees which Approximate those

Requested by Counsel and which Exceeded

those Awarded in this Case ...........

III. The Court Below Erred in Compensating LDF Counsel At Mobile Rates and Not

Looking at the Value of Their Special

Services in the Market in which They

Work ................................

IV. The Court's Wholesale, Percentage

Reductions in Counsel's Hours and

Expenses Were Unwarranted; to the

Extent that Any Deductions Should

Have Been Made, tne Court's Were

Clearly Excessive and Arbitrary ..

V. The Court Erred in Not Holding the

Defendants Jointly and Severally

Liable ...........................

41

43

44

48

53

Conclusion .......................................... . . 54

Appendix A

Letter From Hon. Robert P. Aguilar, United

States District Judge for the Norther District

of California (May 3, 1982)

-li-

TABLE OF CASES

Aamco Automatic Transmission, Inc. v. Taylor, 82

F.R.D. 405 (E.D. Pa. 1979) ................. 32

Adams v. Mathis, 458 F. Supp. 302 (M.D. Ala.

1978) 3

Allen v. Terminal Transportation Co., Inc., 486

F. Supp. 1195 (N.D, Ga. 1980) .............. 53

Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Society,

421 U.S. 240 (1975) 31

Bell v. Wolfish, 441 U.S. 520 '(1979) 27,29

Benton v. Rushen, No. C-80-3130 RPA (N.D. Cal.

Dec. 30, 1981) 42

Bernard v. Gulf Oil Co., 619 F.2d 459 (5th Cir.

1980) 45

Black Gold, Ltd., v. Rockwool Industries, Inc.,

1982-1 Trade Cases If64,4 61 (D. Colo.

1981) 24,32

Blum v. Stenson, No. 81-7385 (2d Cir. Oct. 19, 1981),

aff'g 512 F. Supp. 680 (S.D.N.Y. 1980) 25

Bolden v. City of Mobile, Civ. Action No. 75-297-P

(S.D. Ala. June 14, 1977) 15

* Bradford v. Blum, 507 F. Supp. 526 (S.D.N.Y.

1981) 47,48

Burger v. CPC International Inc., 76 F.R.D. 183

(S.D.N.Y. 1977) 31

Carter v. Shop Rite Foods, Inc., 503 F. Supp. 680

(N.D. Tex. 1980) 25

Charol v. Andes, 88 F.R.D. 265 (E.D. Pa.

1980) 24

* Chrapliwy v. Uniroyal, Inc., 670 F.2d 760 (7th

Cir. 1982) 46

Copper Liquor, Inc. v. Adolph Coors Co., 624 F.2d

575 (5th Cir. 1980) 20,22

* Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d 880 (D.C. Cir.

1980) .......................................

* Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 8 E.P.D. 1(9444

(C.D. Cal. 1974) 24,44

Cases Page

Cases Page

Davis v. Fletcher, 598 F.2d 469 (5th Cir.

1979) 22

Dorfman v. First Boston Corp., 70 F.R.D. 366 (E.D.

Pa. 1976) 31

Fain v. Caddo Parish Police Jury, 564 F.2d 707

(5th Cir. 1977) 22

Fairly v. Patterson, 493 F.2d 598 (5th Cir.

1974) 40

Foster v. Boise-Cascade, Inc., 577 F.2d 335 (5th

Cir. 1978) 23,46

Gates v. Collier, 616 F.2d 1268 (5th Cir.

1980) 34

Gibbs v. Town of Frisco City, 626 F.2d 1218 (5th

Cir. 1980) 49

Haines v. Kerner, 405 U.S. 948 (1972) 45

Harris v. City of Fort Myers, 624 F.2d 1321 (5th

Cir. 1980) 31

Hendrick v. Hercules, 658 F.2d 1088 (5th Cir.

1981) 5,22

Hew Corp. v. Tandy Corp., 480 F. Supp. 758 (D.

Mass. 1979) ■................................. 24,40

Holt v. Sarver, 442 F.2d 304 (8th Cir. 1971) 45

Inmates of the Suffolk County Jail v. Eisenstadt,

360 F. Supp. 767 (D. Mass. 1972), aff'd,

494 F.2d 1196 (1st Cir. 1974), cert, denied,

419 U.S. 977 (1974) ....................... 29

In re Ampicillin Antitrust Litigation, 81 F.R.D.

395 (D.D.C. 1978) 24,32

In re Coordinated Pretrial Proceedings in

Antibrotic Antitrust Actions, 410 F. Supp.

680 (D. Minn. 1975) ....................... 24

In re Gas Meters Antitrust Litigation, 500 F.

Supp. 956 (E.D. Pa. 1980) 24

In re Gypsum Cases, 386 F. Supp. 959 (C.D. Cal.

1974) 24

In re THC Financial Corp. Litigation, 86 F.R.D.

72 (D. Hawaii (1980) 24

Cases Page

Jezrian v. Csapo, 483 F. Supp. 383 (S.D.N.Y.

1979) ....................................... 24

* Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 488

F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974) ................... passim

Johnson v. University College of the Univ. of

Ala., No. 81-7860 (11th Cir.) (pending) ....... 15

* Jones v. Armstrong Cork Co., 630 F.2d 324 (5th

Cir. 1980) 5,45

* Jones v. Diamond, 636 F.2d 1364 (5th Cir.

1981) ...................................... 5,22,29,30,38

Jones v. Federated Dept. Stores, Inc., 527' F.

Supp. 912 (S.D. Ohio 1981) 30,41,52

Jones v. Wittenberg, 330 F. Supp. 707 (N.D. Ohio

1971), aff'd sub nom. Jones v. Metzger,

456 F. 2d 854 (6th Cir. 1972) ............... 29,45

Jordan v. Wolke, 615 F.2d 749 (7th Cir.

1980) 27

Keith v. Volpe, 501 F. Supp. 403 (C.D. Cal.

1980) 25

Knighton v. Watkins, 616 F.2d 795 (5th Cir.

1980) 42,44

Knutson v. Darby Review, Inc., 479 F. Supp. 1263

(N.D. Cal. 1979) 32

Lamphere v. Brown Univ., 610 F.2d 46 (1st Cir.

1979) 25

* Lindy Bros. Builders, Inc. v. American Radiator, 21,22,24,

Etc., 540 F. 2d 102 (3rd Cir. 1976) 28,30,32,41

Lockheed Minority Solidarity Coalition v. Lockheed

Missiles & Space Co., Inc., 406 F. Supp. 828

(N.D. Cal. 1976) 32

Manhart v. City of Los Angeles, 652 F.2d 904 (9th

Cir. 1981) 25,30

Matter of First Colonial Corp. of America, 544

F. 2d 1291 (5th Cir. 1977) 21

McPherson v. School District #186, 465 F. Supp.

749 (S.D. 111. 1978) 48

Cases Page

Miller v. Carson, 563 F.2d 741 (5th Cir.

1977) 29,54

* Morrow v. Finch, 642 F.2d 823 (5th Cir.1981) 34,53

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) 45

Neely v. City of Granada, 624 F.2d 547 (5th Cir.

1980) 22

* Northcross v. Board of Education, 611 F.2d 624

(6th Cir. 1979) ........................ passim

Northeastern Tex. Co. v. A.T.T., 497 F. Supp.

230 (D. Conn. 1980) 24

Parker v. Califano, 561 F.2d 320 (D.C. Cir.

1977) aff'g Parker v. Mathews, 411 F. Supp.

1059 (D.D.C. 1976) 25

Parker v. Lewis, 670 F.2d 249 (D.C. Cir.

1981) 32,54

Ramos v. Lamm, F. Supp. , Civ. Action

No. 77-K-1093 (D. Colo. March 17, 1982) .... 8,47

Rhem v. Malcolm, 371 F. Supp. 594 (S.D.N.Y.),

subsequent opinion, 377 F. Supp. 495

(S.D.N.Y.), aff'd, 507 F.2d 333 (2d Cir.

1974) 29

* Richardson v. Restaurant Marketing Assoc., 527

F. Supp. 690 (N.D. Cal. 1981) 25,34,35

Schwegman Bros. v. Calvert Distillers Corp., 342

U.S. 384 (1951) 38

Selzer v. Berkowitz, 477 F. Supp. 688 (E.D.N.Y.

1979) 52

* Stanford Daily v. Zurcher, 64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D. 21,24,34

Cal. 1974) 37,38,40,44

Stewart v. Rhodes, 656 F.2d 1216 (6th Cir.

1981) ....................................... 46

* Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Ed., 66

F.R.D. 483 (W.D.N.C. 1975) 40,43

Tasby v. Estes, 651 F.2d 287 (5th Cir.

1981) .......................... 5,52

Cases Page

Taylor v. Jones, 495 F. Supp. 1285 (E.D. Ark.

1980) ....................................... 30

Taylor v. Sterrett, 344 F. Supp. 411 (N.D. Tex.

1972), aff'd, 499 F.2d 367 (5th Cir.

1974) 29

Taylor v. Sterret, 600 F.2d 1135 (5th Cir.

1979) 29

Thompson v. Cleland, Civ. Action No. 74-C-3719

(N.D. 111. 1979) ........................... 25

United States v. Terminal Transport Co., Inc.,

653 F.2d 1016 (5th Cir. 1981), aff'g Allen

v. Terminal Transport Co., Inc., 485 F. Supp.

1195 (N.D. Ga. 1988) 5,54

Vecchione v. Wohlgemuth, 480 F. Supp. 776 (E.D.

Pa. 1979) 32

Vulcan Society v. Fire Department of White Plains,

533 F. Supp. 1054 (S.D.N.Y. 1982) 25,30

* Watkins v. Mobile Housing Board, 632 F.2d 565 (5th

Cir. 1980) .............................. 40,49

Wells v. Hutchinson, 499 F. Supp. 174 (E.D. Tex.

1980) 25

Williams v. Boorstin, 20 F.E.P. Cases 1539 (D.D.C.

1979) 41

Wolf v. Frank, 555 F.2d 1213 (5th Cir.

1977) 24

OTHER AUTHORITIES

ABA Code of Professional Responsibility,

Canon 5 ..................................... 52

Berger, Court Awarded Attorney's Fees: What is

"Reas nable?" 126 U. Pa. L. Rev. 281

(1977) 22

* H. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. at 9

(1976) ......................................

122 Cong. Rec. S. 17052 (daily ed. Sept. 29,

1976) 39

Larson, Federal Court Awards of Attorney's Fees

(1981) ................................... 22

Cases Page

S. Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. at 4,

6 (1976) .................................... 21,24

Turner, When Prisoners Sue: A Study of Prisoner

Section 1983 Suits in the Federal Courts,

92 Harv. L. Rev. 610, 617-18 (1979) ........

STATUTORY AUTHORITIES

The Civil Rights Attorneys' Fees Awards Act, 42

U.S.C. §1988

In anyactionor proceeding to enforce a

provision of sections 1981, 1982, 1983,

1985, and 1986 of this title, title IX

of Public Law 92-318, or title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, the court, in

its discretion, may allow the prevailing

party, other than the United States, a

reasonable attorney's fee as part of the

costs...................................

40,44

27,42

passim

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

NO. 82-7024

MOBILE COUNTY JAIL INMATES,

Plaintiffs-Cross-Appellants

ROBERT McCRAY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-

Cross-Appellants

v s .

THOMAS J. PURVIS, SHERIFF, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Alabama

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-CROSS-APPELLANTS

AND PLAINTIFFS-INTERVENORS-CROSS-APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF ISSUES

1. Is there a need for additional guidance in the applica

tion of the Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express factors to enable

the lower courts to, in a uniform and objective manner, arrive at

fees adequate to attract competent counsel as Congress intended?

2. Did the district court misapply the Johnson factors —

including those pertaining to contingency, undesirability and

length of professional relationship — and instead interpose its

own subjective notion of a proper fee, resulting in rates inade

quate to achieve the congressional purpose?

3. Did the court err in awarding local rates to counsel

with special expertise not available locally?

4. Were the court's wholesale, percentage reductions in

counsel's hours and expenses unwarranted, arbitrary, and

excess ive?

5. Did the court err in not holding all the defendants

jointly and severally liable?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. The Proceedings Below

This case originated in 1973 when two community groups

approached local counsel, Mr. Blacksher, and asked him to bring

suit on behalf of their relatives in the Mobile County Jail

*/("MCJ") challenging the conditions of confinement. Tr. 189-90.~

Blacksher accepted the representation without fee, and without

the apparent ability to recover a contingent fee. Tr. 190. He

began by asking the NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.,

("LDF") in New York to provide institutional support in the form

of expertise and expenses. Tr. 190-91. LDF agreed to do so, and

provided background material to enable Blacksher to begin prepa

ration of the case. R. 940, 1011. During 1973 and 1974, just

over 50 hours were spent preparing the suit, including interviews

jV References to the transcript of the hearing on counsel fees

are designated by Tr. References to matters contained in the

Record Excerpts required by Eleventh Circuit Rule 22(a) and

to other documents contained only in the record on appeal are indicated by R.

2

with inmates and former inmates and research regarding the date

of construction, capacity and conditions of the MCJ. _id. ; Tr.

1 90.

On November 21, 1974, Britt Mose Lovett, Jr., filed a pro se

action under 42 U.S.C. §1983 challenging the medical care and

other treatment he received at the MCJ. R. 1. He wrote to

Blacksher, whose partner had been appointed to handle Lovett's

criminal defense, and asked him to represent him. Tr. 191. An

agreement was signed retaining Blacksher's firm and other lawyers

such as LDF, that they might associate. Tr. 208-09. An amended

complaint alleging unconstitutional conditions at the MCJ

and naming the sheriff, the county commissioners, and the

state as defendants was filed on January 27, 1975; it bore

the names of the Blacksher firm and LDF. R. 52. The motion to

certify the class of all pre-trial detainees incarcerated in

the MCJ was granted on May 6, 1975. R. 111-12.

Upon oral motion of all the parties, the court transferred

this case in late 1975 to the Middle District of Alabama for

consolidation with a statewide case pending before Judge

Johnson. R. 136. During the year it was in Montgomery, the

case was handled primarily by lawyers from the Department of

Justice. Tr. 193. Plaintiffs' lawyers spent only 61.6 hours

during that time; almost half of that was spent taking deposi

tions to prepare the case for trial. R. 942, 952, 991-92, 1012.

The case returned after Judge Johnson decided not to certify the

statewide class. See Adams v. Mathis, 458 F. Supp. 302, 304 n. 1

(M.D. Ala. 1978).

3

On return, Blacksher asked the court to bring in the United

States, who had the case ready to go to trial, so their work

would not be lost. Tr. 193. This did not occur. The plaintiffs

prepared the case anew, engaging new experts and updating discov

ery. ^d. at 193-94. Actual trial preparation did not begin

until 1978 when a new LDF lawyer joined the case. See Docket

Entries 52-59; R. 942, 992, 998.

In 1980, plaintiffs in McCray v. Sullivan intervened.

Docket Entry 97.—^ The McCray class consists of state —

i.e., convicted — inmates backed-up in the MCJ. They were

represented by David P. Broome, the fourth or fifth attorney

appointed by Judge Hand to represent the class. _Tr. 227.

Broome sought intervention in order to eliminate duplication,

since Blacksher and LDF already had the experts and legal

expertise necessary to try the case. Tr. 229.

Subsequent settlement efforts failed. See R. 945, 1000.

Trial took eleven days and included the testimony of an expert

penologist, medical doctor, psychiatrist, and sanitarian (former

ly with the United States Public Health Service), a professor of

sociology from the University of South Alabama, numerous lay wit

nesses including inmates and their families, as well as the

presentation of over 75 exhibits containing hundreds of documents.

R. 1149. The court ruled for the plaintiffs, finding extensive

] _ / An earlier attempt to intervene made by the county's female

prisoners housed'at the city jail was rejected. Docket Entry

62. Three individual cases against the MCJ were consolidated

"for the purpose of adjudicating in one action all the claims

seeking declaratory and injunctive relief from conditions at

the Mobile County Jail." R. 763.

4

constitutional deficiencies in the operation of and conditions

at the MCJ. R. 875-916. None of the defendants appealed from

the ruling on the merits.

A two day hearing on counsel fees was held. Tr. 1. The

court ruled for the plaintiffs, awarding $79,372.75 in fees and

$20,906.91 in costs, R. 1168, about half what plaintiffs requested.

R. 1150. Because it found that the majority of the problems

in the jail stemmed from the overcrowding caused by the state,

the court apportioned the award between the state (2/3) and the2/

county (1/3). R. 1151-52. The county paid its portion of

the award, R. 1205; the state appealed and filed a motion for a

stay. R. 1180-83. Plaintiffs filed the instant cross-appeal.

R. 1185. Although the court expressed sympathy with the plain

tiffs' position that the state's appeal was frivolous in light of

3/

recent Fifth Circuit precedent, it stayed only the

disputed portion of the award, requiring the state to pay the

rest. R. 1214.

2/ Although the sheriff was also a party to the litigation

in his official capacity, the court did not enter a judgment

against him because all of the expenses of the sheriff's

department and the jail are borne directly by the county.

3/ The state appealed the award of fees to LDF as associated

counsel — but see Tasby v. Estes, 651 F.2d 287, 289-90 (5th

Cir. 1981); the award of expert witness fees as part of fees and

costs - but see Jones v. Diamond, 636 F.2d 1364, 1382 (5th

Cir. 1981) (en banc); hourly rates of $70 and $75 — but see

Hendrick v. Hercules, 658 F.2d 1188 (5th Cir. 1981) (approving

$120/hr.); the court's findings with regard to the expertise

of LDF counsel — but see Jones v. Armstrong Cork Co., 630

F.2d 324, 325 (5th Cir. 1980); and the apportionment based

on the court's factual findings — but see United States v.

Terminal Transport Co., Inc., 653 F2d 1016 (5th Cir. 1981).

5

B. Conditions at the Mobile County Jail

A review of the underlying facts, as found by the district

court, is helpful to an understanding of the issues presented

on the instant fee appeal. The court found extensive constitu

tional violations in the areas of physical facilities, security,

fire safety, personal hygiene, food service, general psychologi

cal aspects of confinement, visiting, medical and psychiatric

care, discipline, recreation, mail practices, and the rights of

Muslim inmates. The court's findings, included in the Record

Excerpts, indicate the complex and sophisticated nature of the

proof adduced by the plaintiffs. For example, the court made

findings regarding minimum lighting levels in foot-candles, R.

768, the physiological dangers caused by the poor lighting and

ventilation, R. 768-70, and the psychopathogenic effects of the

cell conditions, R. 783-84. The plaintiffs succeeded in

proving constitutional deficiencies in the provision of medical

care, despite the fact that the MCJ had improved staffing in

recent years, R. 794, and the medical program had been approved

by the AMA. R. 797-98.

C. The Fees Hearing

Extensive affidavits and supplemental affidavits were filed

by all plaintiffs' counsel itemizing all time and expenses.

B* 937—63, 986—1018, 1065—68, 1130—41, 1143—45. All three of

plaintiffs' lead counsel -- Blacksher, Winter, and Broome —

testified and were extensively cross-examined. Tr. 189-226,

133—64, and 226—52. In addition, plaintiffs presented practi

tioners in Mobile, Tr. 33-35, and 55-74, an expert on economics

6

and statistics, Tr. 121, an expert in jail and prison litiga

tion, Tr. 77-79, and the attorney representing the defendant

sheriff, Tr. 252-60, to establish reasonable rates of compensation.

The defendants called two witnesses to establish hourly rates, Tr.

164 & 176, and one to detail the county's financial difficulties.

Tr. 260. Except for these two issues, plaintiffs' proof was

essentially undisputed.

To facilitate review, the facts adduced at the fees

hearing and the conclusions reached by the district court

will be set out according to the factors enumerated in Johnson

v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974).

1- Time and labor required: The affidavits of plaintiffs'

counsel established that 1347.75 hours were spent in this

litigation. The bulk of this time was spent by three lawyers:

Blacksher (480), Winter (483), and Broome (188.05). R. 1155.

Although plaintiffs were represented by nine lawyers over the

eight years of the litigation, five of these expended 22 hours

or less ' each. Id.

The state was represented by counsel from the Attorney

General's office (McAlpine) and private counsel representing the

Board of Corrections (Barnes). The county was represented by

private counsel who, until January 1981, was paid a yearly salary

(Wood) and out-of-town counsel (Rinehart) paid hourly. The

sheriff was also represented by private counsel paid hourly

(Stout). Defendants' counsel billed their clients for 1593.89

hours, almost 250 hours more than expended by plaint iffs,-^Even

_4/ The breakdown by attorney was: McAlpine (10), Barnes

(182.75), Curtis (80) (Curtis is Barnes' law partner), R. 1038, Rinehart (791.14), R. 1072, Wood (142, from 1/81), R. 1069 Stout (388), Tr. 269.

7

this figure is deflated, since one of the county's principal

lawyers, Wood, was on salary for six of the six and one half

years of the litigation and only began keeping hours in January

1981. Tr. 269.

Plaintiffs' expert on jail and prison litigation, Ralph

Knowles, testified that the time spent by the plaintiffs

was reasonable in light of the size and complexity of the

case. Tr. 84. He testified that in a similar case against

a single state prison, his office spent 5874.3 hours for a 5

1/2 week trial. Tr. 85. This is approximately 210 hours

per trial day, compared with the 122.5 hours per trial day

in this case. Knowles also testified that in reviewing the

time sheets he saw no claim that, "in any stretch of my

imagination," could be considered unnecessary duplication.

Tr. 86-87. In his opinion: "No responsible lawyer would

handle this case by himself...." Id.

Defendants objected to the fact that two plaintiffs' >

6/lawyers attended the deposition of plaintiffs' experts.

5/ Knowles has been "involved in the most significant prison

litigation to have occured in this country." Ramos v. Lamm,

____ F. Supp. ____, Civ. Action No. 77-K-1093, Slip Op. at

30 (D. Colo. March 17, 1982); Tr. 78-79. He was in private

practice in Tuscaloosa between 1970 and March 1978 when he

left for Washington D.C. to become the Associate Director of

the National Prison Project of the ACLU. Tr. 77-78. In

January 1981, he returned to private practice in Tuscaloosa.

As Judge Kane noted in Ramos: "A general conclusion regard

ing his excellent ability and integrity is not sufficient.

I must point out that during the entire time I have been

connected with the profession of law as a student, practitioner

and judge I have never observed a lawyer who was more

talented or accomplished in the art of cross-examination."Id.

6/ At all other depositions, only Winter appeared for the

plaintiffs.

8

Knowles testified that, in his experience both in private

practice in Tuscaloosa and in prison litigation nationally,

it was common for both plaintiffs and defendants to have two

lawyers at such depositions. Tr. 100-01. In fact, defendants

in this case had three lawyers, one for the sheriff and two

for the county, at all the expert depositions. R. 1137.

The experts' depositions were handled by the LDF lawyer

(as was their testimony at trial). Blacksher was present to

consult on strategy, keep abreast of the case, and to familiarize

himself with the critical witnesses and the complexities of

the case. Tr. 135, 148-50, 194-96. See also Knowles Test.,

Tr. 101-02. Indeed, counsel scrupulously avoided duplication,

as Blacksher testified:

[W]e tried to allocate our time as economically as

possible. That was as much from a selfish standpoint

as anything else.... I want to say that in my

professional opinion, it would have been negligence

for me, as a co-counsel, not to be present at the

deposition of my expert witnesses or their expert

witnesses. I am not talking about>the deposition

of guards where we carefully made sure that only

one of us was present.

Whether I get paid for it or not, if confronted

with the situation, I would have to do it as class

representative. I think Mr. Wood probably agrees

with me, because in every case that we took one of

those depositions, he had his out of town counsel

with him, too....

Tr. 195-96. All three plaintiffs' lawyers met to delegate

tasks to avoid duplication. For example, Broome's main role

was to prepare inmate witnesses; he did no work on the briefs

or depositions in this case. Tr. 230. All the briefs were

written by LDF counsel, as the judge knew from the signatures

and certificates of service.

-9-

At the request of the court, Tr. 161, counsel prepared

a supplemental affidavit detailing all hearings, depositions,7/

and conferences at which multiple counsel were present.

It shows only 14.5 hours for the contested expert depositions

and 63.7 hours of multiple attendance, excluding trial,

during the entire case. R. 1137-38. Defendants put on no

evidence on these points.

Although the court opined that the hours seemed "quite

reasonable" in light of its "own experience in handling this

case," T. 270, it made several wholesale deductions for

alleged duplication. It found but did not identify duplication

because of the inequality of knowledge and expertise between

the LDF lawyer and local counsel. It also noted excessive

travel by the LDF lawyer to be present at depositions where

the court felt a single lawyer sufficed. It reduced Blacksher's

8/

and Winter's out of court time by 15%. it particularly

relied upon the testimony, see Tr. 166, that personal injury

lawyers who litigate for a percentage of the award do not

increase the percentage if they associate another lawyer as

1 _ / The court's request was only for multiple attendance at

depositions and meetings with the experts. Tr. 161-62.

Counsel listed all multiple attendance during his involvement

in the case. There were an additional 12 hours when two

other lawyers attended depositions during the Montgomery

phase of the case. R. 942, 952, 991-992, 1012. All told this

accounts for only 5.6% of all time expended.

J3/ The 15% reduction was in addition to and after other

specific reductions. R. 1157. These other reductions are not being challenged on appeal.

10

R. 1157 58. It also noteda specialist.

mistakenly — that Mr. Knowles might have handled the case more

cheaply from Tuscaloosa. Jtd. at 1157 n.9.

The court also reduced Broome's time by 40% on the

grounds that he was able to take advantage of the work done

by the "Blacksher/Winter team." Id. at 1159. It identified

no unnecessary items of work.

2-3. Novelty and difficulty of the questions and skill

required; The court held that: "With the expertise of the

LDF attorney the law was ... no more difficult than other

rights litigation." R. 1159. The court noted that

the case was factually complex. Id. at 1160. This reflects

the testimony. As Ralph Knowles put it:

I think that jail and prison litigation, as

it has evolved in the last ten or fifteen years,

has become very complex litigation. It requires

knowledge of many different facets of what goes on in jails and prisons.

v,

> The totality concept requires that you do

that, as the Court knows, having heard the testimony.

You get into areas ranging from fire safety and

epidemiology to effects of crowding, violence,

security, and construction problems — a multitude

of complex areas that involve the special expertise

in the use of expert witnesses.... I think there have been bad rulings in cases in this country

that are in the journals now, which were the result

of not having fire power and, the expertise to

appropriately present the facts to'the Judge.

2/

Tr. 80-81.

4« Preclusion of other employment: The court found

that no stigma attached to plaintiffs' counsel and that there

9/ The testimony was that in personal injury cases the

usual fee is between 25 and 40% of the recovery. Tr. 58,

166. These fees, however, often result in an effective hourly rate as high as $200/hr. Tr. 58.

were no conflicts of interest as a result of involvement in

this case. It noted that, whenever an attorney undertakes

litigation, he precludes some other employment. R. 1160.

Broome, appointed counsel for the McCray class, is

engaged in a traditional private civil practice consisting

of business, real estate, personal injury, and insurance

work. Tr. 227-28. His involvement in this case precluded

him from working on matters of existing fee paying clients.

Tr. 238. Blacksher spent time on this case before the passage

of the Act despite competing involvement in Title VII

and other fee paying cases. Tr. 193. Winter's requested

rate was lower than available in New York for corporate law

practice, Tr. 155-56; the rate awarded was lower than what

he received by way of settlement for non-contingent, on

going compliance work in a similar case in Georgia. Tr. 119.

5-6. Customary fee and whether the fee is fixed or

contingent: The bulk of the testimony centered on hourly

rates and the effects of contingency and inflation. Plaintiffs

requested hourly rates of $65 for Broome, $75 for the members

of the Blacksher firm, $95 for Blacksher and Winter, and $125

10/

and $130 for two senior LDF attorneys. They asked that

10/ These attorneys, Joel Berger and Stan Bass, had thirteen

and eighteen years of experience in prison and jail litigation.

R. 1008-09, 1013-14. Each has argued several of the most impor

tant and seminal cases in the field of jail and prison litigation

before the Supreme Court and the courts of appeals. _Id. The

total time billed in this suit was about 20 hours each.

The court disallowed Berger's hours and compensated Bass at

$70/hour. Only the amount of the award to Bass is challenged on

this appeal.

12

these rates be increased by 50% to reflect the contingent

nature of the litigation, the complexity of the factual

11/presentation, and the results obtained.

Defendants' lawyers who received hourly rates were paid

as follows: Rinehart - $50/hour for all time including travel,

R. 1073; Barnes - $50/hour until January 1981, $60 thereafter,

R. 1038. Stout - $50/hour uatil 1977, $60 thereafter. Tr. 259.

Defendants' witnesses testified that reasonable hourly rates

would be $50-60/hour, Tr. 180 (Campbell), and $60-65/hour. Tr.

170 (Engel). In large part, this reflected their own rates for

defending civil rights cases for large governmental clients, as

the court found. R. 1163. Engel, for example, gets a $1500 per

month retainer and $50/hour for defending the county personnel

board whom he has represented since 1957. Tr. 164-169.

When he defended the University of South Alabama in a case

in 1977-78, however, he charged them $70/hour. Tr. 173-74.

Campbell bills the school board at $50, "but," he admitted,

"I am probably low." Tr. 180.

Plaintiffs' testimony was that fees for non-contingent

federal litigation in Mobile ranged from $55-100, depending

on the experience of the lawyer. Tr. 35 (Thurber). A lawyer

-of Blacksher's quality and experience would charge between

$85-100 for non-contingent work. Tr. 37. Cunningham,

whom the state's counsel characterized as coming from the

most prominent firm in Mobile, testified that a reasonable

V \ _ / The plaintiffs did not request that the 50% multiplier

by applied to the non-contingent work on the fee application.

-13-

rate for Blacksher for non-contingent work is "at least a

$100 an hour." Tr. 62. Knowles testified that his partner

was receiving $90 for non-contingent compliance work in an

Alabama jail case and that he had received $60/hour for work

done in 1977. Tr. 99, 87-88. Plaintiffs' economics expert ex

plained that, due to inflation, it would take eighty-eight 1981

1 2/dollars to equal Knowles sixty 1977 dollars. Tr. 126-27.—

The court excluded plaintiffs' evidence with regard to

customary rates for New York counsel, for prison litigation

nationally, and for LDF as awarded by other courts. Tr. 88-

89, 138. Plaintiffs made a proffer, indicating that the

amounts requested (hourly rates plus 50%) were reasonable in

light of rates in New York and Washington and court awards

in other cases. Plaintiffs also proffered that market rates

in New York for Winter's time were $105-115. Tr. 118-19.

With regard to the contingency, plaintiffs' witnesses

agreed that the requested bonus was reasonable. Tr. 43-44,

60. Defendants' witnesses admitted that their lower fees

were based on monthly or quarterly billings so they bore

little or no loss due to delay in payment. Tr. 172, 185. In

fact, the school board lawyer increases his billing from

quarterly to monthly in a big case. Tr. 185.

12/ Plaintiffs adduced evidence on the effects of

inflation on the value of money not collected for over eight

years. For example, to get 1981 dollars with the same purchasing

power, a $50/hour fee for work done in 1973 would have to be

multiplied by 2.03, Tr. 126, or $ 101.50/hour.

-14-

Finally, plaintiffs also established that lawyers normally

charge a higher fee when recovery is contingent on success.

As Cunningham explained:

[I]n an awful lot of contingent fee cases, there

is an excellent chance you are going to prevail.

What you're dealing with is the risk of not prevailing.

Tr. 66.

In assessing the customary fees, the court looked to

other awards in Alabama. Tr. 88; R. 1162-63.— ̂ it held

that the case was not truly contingent: "Certainly there was

some risk of losing, but jail conditions cases in which

plaintiffs are totally unsuccessful are exceedingly rare."

R. 1160—61. Finally, the court held that the case was not

contingent as to Blacksher because LDF covered expenses.

Id. at 1161.

8. The results obtained: This was a totality of con

ditions case. The plaintiffs prevailed on virtually every

issue. R. 761 et seq., 1161.

9* Experience, reputation and ability of attorneys:

The court recognized the abilities of plaintiffs' principal

attorneys. R. 1161-62. Of Blacksher, the court had previously

noted his "special competence in pretrial, trial and legal

analysis in civil rights litigation." Bolden v. City of

MobiLe, Civ. Action No. 75-297-P, Slip Op. at 5 (S.D. Ala. June

14, 1977). The court noted that the LDF attorney, "though in

V 3 / Currently, there are four consolidated cases before this court challenging the practice in Alabama district

courts of limiting fees in §1988 cases to $60/hour despite the

higher rates that in fact prevail in private practice. See,

9 -9•' Johnson v. University Colleqe of the Univ. of Ala.. No.81-78607 ------ ------------------ — —

-15-

practice only about four years has accumulated considerable

expertise in the area of prison litigation." R. 1162.

The court described the custom in Mobile of charging

less for the work of attorneys in practice less than five

years. _Id_. The testimony, however, did not support this

hard and fast rule. Tr. 237.

10. Undesirability of the case; The court observed

that younger members of the bar readily accept civil rights

cases. It excluded this factor from consideration in the fee

calculation. R. 1162. It made no findings about the relative

desirability of jail cases.

The evidence established the undesirability of jail work.

As stated by plaintiffs' counsel:

[J]ail litigation ... is perhaps the most unpleasant and it is complex and extremely protracted. It

has many spin-off effects. Once you are known as

the attorney for the jail conditions, it causes

many additional late-night phone calls and additional

calls to the office to solve all of the inmates'

personal problems, making it very difficult and, in a sense, unpleasant litigation.

Tr. 13-14. Broome, for whom this was the first jail case,

Tr. 245, put it simply: "[I]t is a very depressing type of

litigation.... You have to spend time in that facility

interviewing the inmates and getting in the cell with them...."

14/Tr. 239.—

14/ The physical state of the cells was abhorrent. See

R. 767-70, 779-80. Moreover, this case involved some personal risk.

Counsel were the only free world people who had ever entered

the MCJ cells. As the district court found: "Because they

fear the inmates, the guards do not enter the cells unless the

inmates have been removed." R. 771.

-16-

Even defendants' witnesses admitted that this case was

undesirable in 1974 when counsel accepted representation.

Tr. 181, 171. Although they thought the Act now made

these cases desirable, the record makes clear that — with

the exception of Blacksher and LDF, who have dedicated

themselves to vindicating the civil rights of the unrepre-IV

sented — virtually every lawyer involved in jail

litigation in Mobile was appointed. Tr. 12, 41, 226, &

227.

11• Nature and length of the professional relationship:

Defendants' evidence established that a long term relation

ship with a client results in lower fees because of the substan

tial amount of repeat business it provides. For example, Engel

testified that he charges the county personnel board, which

provides 25% of his practice, $50/hour while the University of

JJV LDF's corporate charter provides that it was formed to

assist blacks in securing their constitutional rights by the

prosecution of lawsuits. The trial court noted that Blacksher

and his firm are well known for their civil rights practice.

R. 1162. Yet even Blacksher testified about his reluctance to take this case.

I want to say from the beginning of this case

to the end, I have never sought out this work. I

took it as a great responsibility to represent this

class of inmates. I felt personally offended by

the conditions that they lived in and I felt like

they were entitled to a good job, but I was also

up to my ears in other business that I was, frankly,

more involved in....

Tr. 193. As recognized by the Sixth Circuit: "The entire

purpose of the statutes was to ensure that the representation

of important national concerns would not depend upon the

charitable instincts of a few generous attorneys." Northcross

v . Board of Ed., 611 F.2d 624, 638 (6th Cir. 1979).

-17-

South Alabama pays him $70. Tr. 169, 173, 174. The school

board's lawyer charges it $50/hour. Tr. 185. In representing

a corporate client which provides three or four matters a year,

however, the same lawyer gets $75/hour on a non-contingent

basis. Tr. 187.

The court found that plaintiffs' counsel did not have a

long standing professional relationship with the client.

R. 1161. This was not a factor in determining the rates

awarded in this case. R. 1164.

12. Awards in similar cases: The parties submitted

examples of such awards nationwide. R. 1162. The court,

however, restricted itself to Alabama cases. Id.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The court below misapplied the Johnson v. Georgia Highway

Express factors. While sanctioned by case law and specifi

cally incorporated by the legislative history of §1988,

the Johnson factors alone are not sufficient to ensure the

uniform and objective determinations necessary to achieve

the purposes of the Act. This was recognized by the Congress

in citing specific cases as correct applications and weight

ings of the Johnson factors. It is also reflected in the

increasing volume of counsel fee awards cases presented to

this court.

Although the court below discussed the Johnson factors,

it essentially applied its own subjective notion of appropriate

hourly rates. An objective but conservative application of

the contingency, undesirability, and length of professional

relationship factors based on the evidence provided by the

parties would yield hourly rates substantially in excess of

those awarded.

The court below also erred in excluding evidence of

national and New York rates for out-of-town counsel. The

evidence clearly established that expertise not available

in the local community was necessary for the preparation and

trial of this case. The court's own findings establish

that out-of-town counsel had that expertise and that it

contributed to the presentation of this case. Nevertheless,

the court compensated him at Mobile rates which neither

reflect that expertise nor account for his higher costs. If

the complexity and specialized nature of a case require the

assistance of an out-of-town specialist, the Act requires that

he be compensated at rates that reflect the prevailing

market for his services. Otherwise, the congressional

purpose to attract competent counsel cannot be achieved.

The court arbitrarily made wholesale percentage deduct

ions in the hours and expenses of counsel. In light of

undisputed evidence, the reasons identified by the court do

not justify any reductions. Even if they did, the amounts

deducted exceed the specified items by 300%. This is just

another example of how, within the framework of the Johnson

factors, the court first reached subjective determinations

regarding the proper amount of counsel fees and then applied

ex post facto reasoning in justification.

Although the court's apportionment of the award was

sound, it erred in not holding the defendants jointly and

severally liable. The purpose of the Act is not to punish

defendants relative to their liability but to compensate

plaintiffs for their fees and expenses. Prevailing plaintiffs

should be able to recover their fees without additional delays;

defendants should be responsible to either arrange or litigate

contribution. Civil rights plaintiffs, no less than tort

victims, are entitled to prompt compensation.

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

The court has jurisdiction over this case pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §1291. Jurisdiction in the district court was premised

on 28 U.S.C. §1343(3) & (4). The substance of the litigation

was governed by 42 U.S.C. §§1983 & 1988.

ARGUMENT

I. THIS COURT MUST REVIEW THE LOWER COURT'S SUBJECTIVE AP

PLICATION OF THE JOHNSON FACTORS AND PROVIDE A UNIFORM

AND OBJECTIVE METHOD FOR THEIR APPLICATION IF THE BASIC

_______ POLICY OF THE FEES ACT IS NOT TO BE SUBVERTED______

The well worn standard for the review of fee awards is

the "abuse of discretion" standard. Copper Liquor, Inc, v

-20-

Adolph Coors Co., 624 F.2d 575, 581 (5th Cir. 1980).

Unhappily, this formulation does not advance

the analysis; it merely restates the problem,

for one must understand what one means by

"discretion."

Lindy Bros. Builders, Inc, v. American Radiator, Etc.,

540 F.2d 102, 115 (3rd Cir. 1 976) (en banc) (Lindy II).

When Congress provided that a court should, "in its

discretion," award "a reasonable attorney's fee," 42 U.S.C.

§1988, it did not intend that the important policies it was

seeking to effectuate be left to the subjective determina

tions of hundreds of individual federal judges. Rather, it

made clear that awards should be made under the same standards

as the fee provisions of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the

statutes providing for fees for other types of equally complex

federal litigation such as antitrust. S. Rep. No. 94-1011,

94th Cong., 2d Sess. at 4, 6 (1976). To this end, it noted the

Johnson factors, but provided specific examples of their proper

application, _id. at 6, citing Stanford Daily v. Zurcher, 64

F.R.D. 680 (N.D.Cal. 1974), and other cases. These cases

were approved as having "resulted in fees which are adequate

to attract competent counsel, but which do not produce wind

falls to attorneys." S. Rep., supra, at 6. See also H.

Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong., 2nd Sess. at 9 (1976).

Experience shows that Congress was right. It is not

enough to require the lower courts to discuss the Johnson

factors. See Matter of First Colonial Corp. of America, 544

-21-

F.2d 1291, 1300 (5th Cir. 1977); Fain v. Caddo Parish Police

Jury, 564 F.2d 707, 709 (5th Cir. 1977). Courts have continued

to "parrot" the Johnson factors without meaningful explication.

See Davis v. Fletcher, 598 F.2d 469, 470-71 (5th Cir. 1979).

As a result, this court continues to be presented with widely

divergent awards based on recitations of the Johnson factors.

Compare Hendrick v. Hercules, 658 F.2d 1088 ( 5th Cir. 1981)($ 120/hr.

for Birmingham, Ala.), with Neely v. City of Granada, 624 F.2d

547 (5th Cir. 1980)($35 and $45/hr. for Jackson, Miss.).

Other circuits and numerous commentators have recognized

the problems with the unguided use of the Johnson factors.

E. R. Larson, FEDERAL COURT AWARDS OF ATTORNEY'S FEES 133-34

(1981); Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d 880, 890 (D.C.Cir.

1 980)(en banc); Northcross v. Board of Education, 611 F. 2d

624, 642 (6th Cir. 1979); Berger, Court Awarded Attorneys'

Fees: What is ''Reasonable?1' 126 U.Pa.L.Rev. 281 , 286-87

(1977). This court has begun to respond, giving guidance to

the lower courts in the application and weighting of the

Johnson factors with its refinements in Copper Liquor,

supra, 624 F.2d at 587 & n. 15, and Jones v. Diamond, 636

F. 2d 1 364, 1 382 (5th Cir. 1981)(en banc) . However, these

guidelines still fail to "lead to consistent results, or, in

many cases, to reasonable fees." Northcross, supra, 611 F.2d

at 642. For example, the court below purported to follow the

"lodestar" method advanced by Copper Liquor, supra. Yet it

still undercompensated counsel, in part by application of the

"subjective factors," ic[. , 624 F.2d at 583 n. 15, inherent in

the pure Johnson approach.

-22-

Particularly where the legislative history is so explicit,

a court abuses the discretion that Congress consigned to it

when it fails to follow the proper standards. See Lindy

II, supra; Davis, supra. This is precisely the issue here.

The lower court misapplied the proper standards, supplanting

them with its own subjective determinations. This continuing

problem is subverting the basic purpose of the Act.

Will competent and successful trial attorneys

accept employment in a complex ... case if this

is the standard by which fee awards are to be

computed?

Foster v. Boise-Cascade, Inc., 577 F.2d 335, 337-38 (5th

Cir. 1978)(Vance, C.J., dissenting).

II. IN SETTING HOURLY RATES, THE LOWER COURT MISAPPLIED THE

JOHNSON FACTORS— INCLUDING THOSE RELATING TO CONTINGENCY,

UNDESIRABILITY, AND LENGTH OF PROFESSIONAL RELATIONSHIP—

RESULTING IN FEES BELOW MARKET RATES FOR TRADITIONAL,

__________ NON-CONTINGENT, CIVIL LITIGATION______________

A. Application of the Johnson Factors in the Manner

Congress Intended Would Have Resulted in Substan-

tially Higher Fees_____________________

The purpose of the act is to attract counsel to civil

rights litigation so that the important congressional policies

behind the civil rights statutes will be vindicated. S. Rep.,

supra, at 2, 6; H. Rep. supra, at 3, 9. This is accomplished

by awarding fees that approximate "the fair market value of the

attorney's services." Northcross, supra, 611 F.2d at 638.

Accord, Copeland, supra, 641 F.2d at 894.

-23-

Plaintiffs requested hourly rates of $65 to $95.

These were in line with — indeed, a bit below — market rates

for the various attorneys. They requested that the court

adjust that amount by the application of a 50% multiplier to

account for the contingent, factually complex and undesirable

nature of the case and the results obtained.

This was the very approach applied in both Stanford

Daily, supra, 64 F.R.D. at 688, and Davis v. County of Los

Angeles, 8 E.P.D. 1(9444 at 5048 (C.D. Cal. 1 974), two of the

cases adopted by Congress as a proper application of the

Johnson factors. S. Rep., supra, at 6. This approach was

being applied in many antitrust cases, see, e. g. , Lindy II,

supra; In re Coordinated Pretrail Proceedings in Antibiotic

Antitrust Actions, 410 F. Supp. 680 (D. Minn. 1975) (enhancement

factors of 2.0 and 2.5); In re Gypsum Cases, 386 F. Supp. 959

(C.D. Cal. 1974) (multiplier of 3), which Congress also cited

as paradigmatic of how fees should be awarded under §1988. S.

Rep., supra, at 6. It has been followed in a host of antitrust” ^

16/ See, e .g. , Wolf v. Frank, 555 F.2d 1213 (5th Cir. 1 977)

(33%); Black Gold, Ltd, v. Rockwool Industries, Inc., 1982-1

Trade Cas. 1164,461 (D. Colo. 1981) (multiplier of 1.25). In re

Gas Meters Antitrust Litigation, 500 F.Supp. 956 (E.D.Pa.

1980); Charol v. Andes, 88 F.R.D. 265 (E.D.Pa. 1980) (1.5);

Northeastern Tex. Co. v. A.T.T., 497 F.Supp. 230 (D.Conn. 1980)

(30%); In re THC Financial Corp. Litigation, 86 F.R.D. 721 (D.HawaTI 1980) (1.4 and 1.5); Jezrian v. Csapo, 483 F.Supp.

383 (S.D.N.Y. 1979) (2.0 and 1.5); Hew Corp. v. Tandy Corp.,

480 F.Supp. 758 (D.Mass. 1979) (1.25 multiplier despite $58,400

retainer); In re Ampicillin Antitrust Litigation, 81 F.R.D. 395

(D.D.C. 1978)( 1 .5 multiplier in addition to inflation adjustment).

-24-

and civil rights cases since the passage of the Act.

The court awarded no multiplier and set hourly rates of

1 8/$60, $70 and $75. it indicated that the increase of

these rates over the $50-60/hour urged by defendants reflected

the slight risk involved in prevailing, an inflation factor,

and awards in other cases. R. 1163. As we show below, these

hourly rates do not even reflect rates for non-contingent

litigation in Mobile, let alone any adjustment for contingency

and inflation. As we further show below, the application of the

Johnson factors in an objective manner would yield rates

substantially the same as the hourly rates plus multiplier

approach intended by Congress and urged on the court below.

B. The Hourly Rates Awarded Do Not Reflect Defendants'

Evidence Regarding Non-Contingent Rates When Adjust-

ed By the Length of Professional Relationship Factor

The defendants' witnesses and lawyers established that

their rates were $50-60/hour. In all these cases, the clients

1V See, e.g. , Blum v. Stenson, No. 81-7385. (2d Cir. Oct. 19,1981), aff'g 512 F. Supp. 680 (S.D.N.Y. 1981) (50% adjust

ment); Manhart v. City of Los Angeles, 652 F.2d 904 (9th Cir.

1981) (1.32 multiplier); Northcross, supra, 611 F.2d at 638 (10%

despite only slight contingency); Lamphere v. Brown Univ., 610

F. 2d 46 , 47 (1st Cir. 1 979) ( 10%); Parker v. Califano, 561 F.2d

320 (D.C. Cir. 1 977), aff' g Parker v. Mathews, 411 F. Supp.1059 (D.D.C. 1976) (25%); Vulcan Society v. Fire Department of

the City of White Plains, 533 F. Supp. 1055 (S.D.N.Y. 1982)

("modest" 50%; case neither novel nor undesirable); Richardson

v. Restaurant Marketing Assoc., 527 F.Supp. 690 (N.D. Cal.

1981) (multiplier of 2); Carter v. Shop Rite Foods, Inc., 503

F. Supp. 680 (N.D. Tex. 1980) (33% and 11% above $90/hr. for

two different stages of the litigation); Keith v. Volpe, 501 F.

Supp. 403 (C.D. Cal. 1980) (3.5); Wells v. Hutchinson, 499 F.

Supp. 174 (E.D.Tex. 1980) (2); Thompson v. Cleland, Civ. Action

No. 74-C-3719 (N.D.111. 1979) (multiplier of 2; rates of $55-86/hr.).

18/ Since more than 80% of counsel's time was out of court,

the extra $5/hour for in court time is de minimis. It amounts

to about $300 each to Blacksher and Winter, about $215 for Broome. With deductions of time, the effective hourly rates

were $65, 60 and 46.

-25-

were large governmental organizations which provided a

significant percentage of the attorney's practice, typically

25%. Thus, these rates reflect a discount to a large client

that provides a stable and secure, repeat source of business.

Defendants' witnesses testified that their fees were higher

when they represented other clients. The school board

lawyer charges $75/hour for a corporate client that provides

three or four matters a year. Tr. 187. Engel charged the

University of South Alabama $70/hour to defend them in

1977-78. Tr. 174.

Plaintiffs' counsel have no prospect of repeat business

from Mr. Lovett. Nor do they desire or expect to support a

practice on work coming to them from other class members.

They will not even have the prospect of plaintiffs providing

the three or four fee paying matters a year that the school

board lawyer expects from his corporate client. If the Johnson

length of professional relationship factor means anything,

it must mean that, in fixing an appropriate hourly rate, a

district court must take into account the different way the

market handles fees for steady clients and fees for "one-shot"

representations. Counsel cannot be awarded "contingent" rates

that barely equal what they can obtain in the marketplace on a

non-contigent basis from a one time client and still be expected

to be attracted to civil rights litigation as Congress intended.

Accordingly, the base non-contingent rates for the type of

representation plaintiffs' counsel undertook are the $70 and

$75 rates charged non-repeat paying clients in Mobile.

-26-

C. The District Court Misapplied the Contingency Factor

in Failing to Properly Evaluate the Contingent Nature

of this Litigation and in Failing to Award Rates that

Reflect the Economic Effects of the Contingent Nature

of Counsel's Compensation______________

In applying the Johnson contigency factor, the

court made three errors. First, it did not properly assess the

real contingencies facing counsel when they accepted repre

sentation in this case. Second, it did not assess the economic

effects of the delay in payment inherent in contingent fees.

Third, it misunderstood the reasons why Congress determined

that the contingency factor warranted an increase in awards and

thus failed to accommodate those concerns.

1 . The court erred in assessing the contingent risks of

this litigation; The court held that the fee was not truly

contingent because the likelihood of not prevailing in jail

cases is slight. R. 1159-61. The court erred on several

counts.

First, it is simply not true that jail cases are all "sure

winners." _Id̂. It ought not to take expert testimony — which

plaintiffs offered, Tr. 80-81 — to establish that jail cases

are lost. This court can review the reports itself. See, e.g .,

Bell v. Wolfish, 441 U.S. 520 (1979); Jordan v. Wolke, 615 F.2d

749 (7th Cir. 1980). A recent empirical study of prisoner

cases nationally found that 68% were dismissed before the

defendants even filed a response, only 4.2% made it to trial.

Turner, When Prisoners Sue: A Study of Prisoner Section

1983 Suits in the Federal Courts, 92 Harv. L. Rev. 610, 617-18

(1979). In a 664 case sample, injunctions were granted in

three cases and nominal damages awarded in two others. Id. at

-27-

624. As one judge wrote:

Although there are now provisions for award of

attorney's fees to successful §1983 litigants,

attorneys are generally unwilling to take such cases

in view of the unlikelihood of prevailing on the merits.

Id. at 651 n. 195 (Letter to the author from Chief Judge

1 9/Edward S. Northrup, D.Md., Nov. 1 4, 1977).—

Second, the judge engaged in impermissible hindsight in

assessing the chances of success. It is fundamentally unfair to

judge the chances of success after plaintiffs have presented

their case, marshalled the facts, briefed the law, and convinced

the judge. Nor can the chances of success be judged in

light of subsequent developments in the case law: "[T]he

district court should appraise the professional burden undertaken

— that is, the probability or likelihood of success, viewed at

the time of filing suit." Lindy II, supra, 540 F.2d at 117

(emphasis added). Accord, Northcross, supra, 611 F.2d at

638-39.

Jail condition cases may now look like easy pickings.

"However, that situation did not prevail ... when most of the

services at issue were performed." Northcross, supra, 611 F.2d

at 639 (school desegregation litigation). At the start of this

case, and at every relevant point thereafter, counsel could

only have viewed their chances of success as unsure. When

19/ The author of the article spoke or corresponded with

other district court judges who expressed similar sentiments.

As another judge wrote: "The lack of assured compensation is

the primary factor inhibiting the appointment of counsel." Id.,

Letter to the author from Chief Judge Thomas J. MacBride,

E.D.Cal., Dec. 22, 1977.

-28-

Blacksher first undertook the representation in 1973, the case

law was slim. Only one of the first few jail cases had been

affirmed by a court of appeals. See Jones v. Wittenberg, 330

F. Supp. 707 (N.D. Ohio 1971), aff'd sub nom. Jones v. Metzger,

456 F.2d 854 (6th Cir. 1972); Taylor v. Sterrett, 344 F.Supp.

411 (N.D.Tex. 1 972), aff'd, 499 F.2d 367 (5th Cir. 1 974) ;

Inmates of the Suffolk County Jail v. Eisenstadt, 360 F.Supp.

767 (D.Mass. 1972), aff'd, 494 F.2d 1196 (1st Cir. 1974), cert,

denied, 419 LJ.S. 977 (1974); Rhem v. Malcolm, 371 F. Supp. 594

(S.D.N.Y.), subsequent opinion, 377 F. Supp. 495 (S.D.N.Y.),

af_fj_d, 507 F. 2d 333 (2d Cir. 1 974). When the amended

complaint was filed in early 1975, only the Taylor decision,

which rested in large part on state law, had come down in this

circuit; this court's opinion in Miller v. Carson, 563 F.2d 741

(5th Cir. 1977), was still more than a year away. In 1979, when

the bulk of trial preparation was done, and in 1980, when

preparation was completed and the trial was held, the latest

developments in jail litigation were Bell v. Wolfish, 441 CJ.S.

520 (1979), and the panel opinions in Jones v. Diamond, 594

F.2d 997 (5th Cir. 1979), and Taylor v. Sterrett, 600 F.2d 1135

(5th Cir. 1979)(dismissing case). Wolfish significantly raised

plaintiffs' burden of proof, dispensing with the "least restric

tive means" test and requiring proof of conditions that "amount

to punishment." 441 U.S. at 535. See Tr. 108-09. Jones had

sanctioned crowding in cell areas providing as little as 15,

20/ It should be noted that LDF lawyers were involved in all of

these cases but Rhem. Rhem, which was not an LDF case, was handled by Joel Berger, now an LDF lawyer.

-29-

11, and 6.8 square feet per inmate, see Brief of the NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., as Amicus Curiae

before the Fifth Circuit sitting en banc in Jones v. Diamond,

No. 78-1289 at 13, crowding more severe than that then existing

at the MCJ. Even when this court reversed, 636 F.2d 1364,

counsel for defendants noted in letters to the district

court that Jones was not dispositive of the issues in this

case.

The court also overlooked the contingencies caused by

the factual complexity of this case and the tenacious opposi

tion of the defendants. Complexity increases the risk: A case

that should be won based on the law may not succeed if the

court cannot be brought to perceive the intricate relationships

between the facts. Accordingly, courts have adjusted awards to

reflect the contingencies due to complexity. Manhart v. City

of Los Angeles, 652 F. 2d 904, 908 (9th Cir. 1981); Lindy II,

supra, 540 F.2d at 117; Vulcan Society, supra, 533 F.Supp. at

1065 (issues not novel, undesireable or risky, but factually

complex: "modest" 50% adjustment applied); Jones v. Federated

Dept. Stores, Inc., 527 F. Supp. 912, 916-17 (S.D. Ohio 1981);

Taylor v. Jones, 495 F. Supp. 1285, 1297 (E.D. Ark. 1980)

(20%). Here, the testimony and the ultimate findings of

the district court establish the complex nature of jail litiga

tion. Tr. 80-81; R. 761 et seq. The Wolfish standard has only

increased the complexity of the burden.

The tenacity of the defense also increases counsel's

risk of not prevailing. Vulcan Society, supra, 533 F. Supp. at

1065; Jones, supra, 527 F. Supp. at 917; Taylor, supra, 495

-30-

F. Supp. at 1285; Burger v. CPC International Inc., 76 F.R.D.

183, 189 (S.D.N.Y. 1977) (securities); Dorfman v. First

Boston Corp., 70 F.R.D. 366, 375 (E.D. Pa. 1976) (securities;

50% adjustment for vigorous opposition). Where, as here, "the

facts are strongly disputed," Northcross, supra, 611 F.2d at

638, counsel's risk of not prevailing is increased.

Yet another contingency stood between counsel and compen-

sat ion.

[Tjhis case was not simply contingent in the usual

sense, i.e., dependent on winning the merits. At

the time plaintiffs' counsel undertook this assignment, ... there was no statute providing for

attorneys' fees even if they prevail.... This was thus doubly contingent....

Harris v. City of Fort Myers, 624 F.2d 1321, 1325-26 (5th

Cir. 1980). Less than four months after the amended

complaint was filed, the Court's opinion in Alyeska Pipeline

Service Co. v. Wilderness Society, 421 U.S. 240 (1975), made

clear that there was no basis for an award of fees unless

plaintiffs could show that "the defendants litigated in bad

faith." Harris, supra, 624 F.2d at 1326. Thus, as stressed in

Harris, the court below

would have been more than justified in granting

a "multiplier" or "incentive" award above the

fixed hours claimed in light of the contingen

cy nature of the case. [Emphasis added] .

Id. But, as we show below, the court failed to even compens

ate for the effects of delay in payment, let alone the risk

of nonpayment.

2. The court erred in failing to assess the economic

effects of the delay in payment: The market asks more when

-31-

fees are contingent for two reasons. First, there is a

premium because the entire fee is at risk. Second, risk

aside, the delay in payment until successful completion of

the case means that the lawyer is losing the value of the

use of the money. Thus:

The delay in receipt of payment for services

rendered is an additional factor that may be in

corporated into a contigency adjustment. The

hourly rates used in the "lodestar" represent the

prevailing rate for clients who typically pay their

bills promptly. Court-awarded fees normally are re

ceived long after the legal services are rendered.

That delay can present cash-flow problems for the

attorneys. In any event, payment today for services

rendered long in the past deprives the eventual

recipient of the value of the use of the money in the

meantime, which use, particularly in an inflation

ary era, is valuable. A percentage adjustment to

reflect the delay in receipt of payment therefore

may be appropriate.

Copeland, supra, 641 F.2d at 893, citing Lindy II, supra,

540 F.2d at 117; Black Gold, Ltd, v. Rockwool Industries,

Inc. , 1 982-1 Trade as 1(64,461 (D. Colo. 1 981) ( 1 .25); Vecchione

v v. Wohlgemuth, 480 F. Supp. 776, 795 (E.D. Pa. 1979) (10%

adjustment); Knutson v. Darby Review, Inc. 479 F. Supp. 1263,

1277 (N.D. Cal. 1979) (15% for delay alone); Aamco Automatic

Transmissions, Inc, v. Taylor, 82 F.R.D. 405, 415 (E.D.Pa. 1979);

Lockheed Minority Solidarity Coalition v. Lockheed Missiles

& Space Co. , Inc.., 406 F. Supp. 828, 834-35 (N.D.Cal. 1 976) (20%).

£ * 21/Cf. Parker v. Lewis, 670 F.2d 249, 250 (D.C.Cir. 1981).—

21/ Adjusting the award to reflect the economic effects of delay

accomplishes another important purpose of the Act. Since

counsel for the defendants are being paid promptly, they bear

no economic risk by prolonging the litigation. Plaintiffs'

counsel, on the other hand, are not being paid and are advancing often considerable expenses. An adjustment for delay helps

deter the defendants from taking advantage of plaintiffs'

"tremendous disadvantage ... in terms of finances and resources." Northcross, supra, 611 F.2d at 634. Accord, Jones, supra, 527 F. Supp. at 917.

-32-

This case involved work done as early as 1973. The

district court was asked to accomodate for inflation by

applying the inflation adjustment factors derived from the

Consumer Price Indices of the relevant years. Tr. 119-32.

It was asked to accomodate for the other aspects of contin

gency by use of a 50% adjustment. The court said that it

compensated for the effects of inflation by awarding current

rather than historical rates, R. 1155, 1164, citing In re

Ampicillin Antitrust Litigation, 81 F.R.D. 395, 402 (D.D.C.

1978). But see id. at 405 (1.5 multiplier in addition to

inflation adjustment). The hourly rates, however, were the same

as defendants' witnesses were charging for non-contingent work

in 1977-78. Thus, in reality, the rates awarded accounted

neither for contingency nor inflation. The court did not even

consider whether counsel should be compensated for the lost

value of the use of the money.

If the Act is to succeed — attracting competent counsel

to civil rights litigation — then lawyers must be compensated

at rates that reflect what they could earn elsewhere in the

legal marketplace. Copeland, supra, 641 F.2d at 894; Northcross,

supra, 611 F.2d at 638. Counsel could have undertaken non

contingent commercial work and had payment when their time was

expended. Their payment now is eroded by inflation and the

lost value of the use of the money.

The market quantifies the economic value of the use of

money (or delay in payment) by the payment of interest. This

court has recognized this in the fee context and awarded

-33-

interest not only on the judgment, Gates v. Collier, 616 F.2d

1268 (5th Cir. 1980), but from the time the hours were actually

expended. Morrow v. Finch, 642 F.2d 823, 826 (5th Cir.

1981). In an inflationary era, the market interest rate quan

tifies the value of the use of the money above the eroding

effects of inflation. Thus, application of the average prime

rate for the relevant years to the historical rates for non

contingent litigation would provide an objective method of

assessing the economic effects of the contingent nature of the

fees. See Richardson v. Restaurant Marketing Assoc., 527 F. Supp.

690, 698 (N.D.Cal. 1981)(augmentation of back pay award in

22/Title VII case based on average prime rates).—

Application of this objective measure of the economic

effects of contingent payment to the most conservative hourly

, 23/ .rates indicates how much the district court erred in

compensating counsel. The sheriff's lawyer was getting $50/hour

until 1977, and $60 thereafter. Tr. 259. Taking this as a

measure of non-contingent rates charged large repeat clients in

22/ In Richardson, the court also discussed the effects of

delay and inflation on the award of attorneys' fees. Follow

ing the Stanford Daily approach sanctioned by the legisla

tive history, it applied a multiplier of 2 to accomodate for

the contingent nature of success, the quality of representa

tion, and the delay in payment. It increased the multiplier

to 2.25 to accommodate for inflation. 527 F. Supp. at 702.

23/ The testimony established 1981 non-contingent rates of

$85—100/hour. The calculations in this section are based on

defendants' evidence of $70 and 75/hour fees for "one-shot" representation.

-34-

. .. 24/Mobile, and increasing it by $10 for non-contingent

"one-shot" representation (based on defendants' witness's

$70/hour defense in 1977, Tr. 174, see Section B., supra), we

have base rates for local counsel of $60 from 1975 and $70 from

1977. Extrapolating back, we could construct rates for 1973 and

1974 of $50. Adjusting these by the average yearly prime

25/ 26/rates which are set out in the margin, would

provide the rates set out in Table 1. These rates, averaging

24/ The county's Montgomery lawyer received $50/hr. during

the entire course of the litigation, R. 1073, the school

board lawyer received $45 until 1976 and $50 thereafter, Tr.

180, and the state's lawyer received $40 until April 1979 and $50 thereafter. R. 1038.

25/ The Richardson court used a 90% of prime figure. 527

F.Supp. at 698. This was based on the IRS adjusted prime

rate figures which are based on 90% of the prime rate on

September 15. Ld. The IRS, however, has recently changed to

a 100% of prime figure. 1 982 Federal Tax Guide (CCH) 1I6919A.

26/ In Richardson, supra, the court obtained average prime

cate figures for 1975-1980 from the Federal Reserve Bank.

527 F.Supp. at 698. They were as follows:

1 975........ 7.86% 1978........9.06%

1976 ....... 6.84% 1979.......12.67%

1977 ....... 6.83% 1980...... 1 5.27%

Id. The figures for 1973, 1974, and 1981 were:

1973........ 8.03% 1981 18.87%

1 974.......10.81%

These figures come from the Economic Report of the President,

Annual Report of the Council of Economic Advisors at 310

(U.S. G.P.O., Wash., D.C. 1982), House Doc. No. 97-123, 97th Cong. 2d Sess.

-35-

at about $111 per hour, are the minimum necessary to

compensate counsel for the delay in payment; they do not

reflect any risk, special ability, preclusion of other employ

ment or any other Johnson factor.

TABLE 1

Historical Multiplier Based2g/

On Prime Rate —

EquivalentYear Rate Value Rate

1973 $50 2.448 $122.40/hr.

1974 $50 2.266 1 13.30/hr.

1975 $60 2.045 122.74/hr.

1976 $60 1.896 1 13.76/hr.

1977 $70 1.775 124.25/hr.

1978 $70 1.661 116.27/hr.

1979 $70 1.523 106.61/hr.

1980 $70 1 . 352 94.64/hr.

1981 $70 2 9/1.17 3— 82.11/hr.

Average rate $1 10.68/hr.

27/ The prime rate is granted only to a bank's most credit

worthy customers, those with almost no risk of non-payment.

Riskier obligations demand higher rates. Thus the prime rate establishes a minimum measure of the degree by which fees

owed but not paid should be increased. Application of the prime

rate to the hourly rates charged to clients who pay regardless

of result would undercompensate an attorney who brings a civil