Plaintiffs' Memo in Opposition to Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment with Certificate of Service

Public Court Documents

September 20, 1991

28 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Memo in Opposition to Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment with Certificate of Service, 1991. 5c45ee63-a246-f011-8779-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b4b028f6-f482-42d6-8a98-b5276e44cda1/plaintiffs-memo-in-opposition-to-defendants-motion-for-summary-judgment-with-certificate-of-service. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

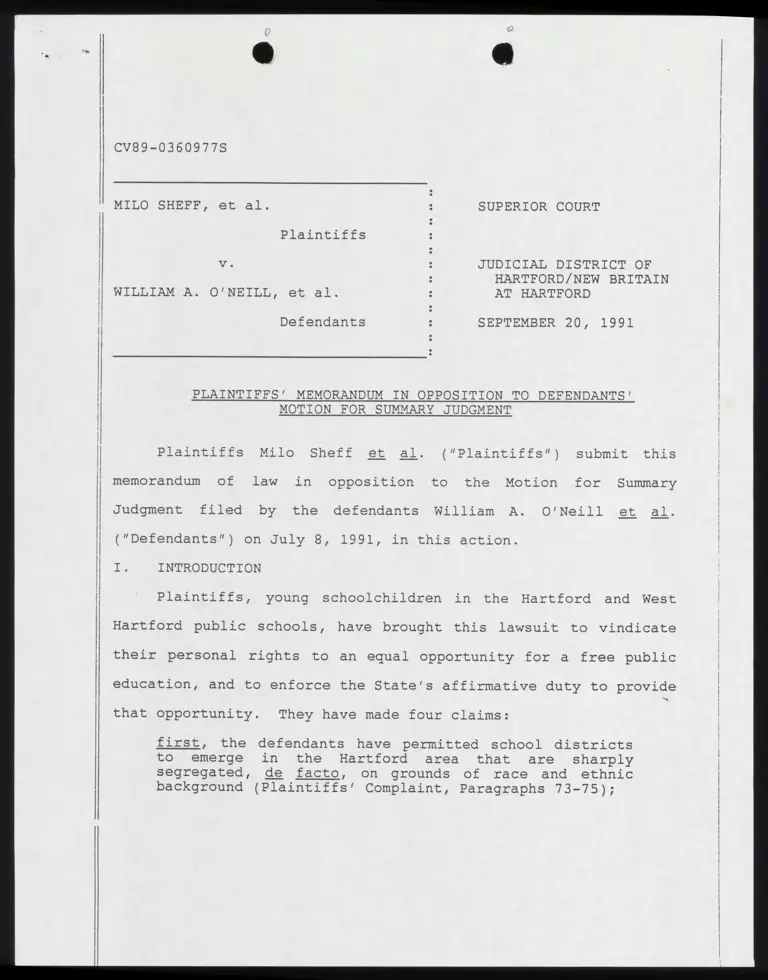

Cv89-0360977sS

MILO SHEFF, et al. : SUPERIOR COURT

Plaintiffs

¥. : JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF

2 HARTFORD/NEW BRITAIN

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, et al. : AT HARTFORD

Defendants : SEPTEMBER 20, 1991

PLAINTIFFS' MEMORANDUM IN OPPOSITION TO DEFENDANTS’

MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

Plaintiffs Milo Sheff et al. (7Plaintiffs”) submit this

memorandum of law in opposition to the Motion for Summary

Judgment filed by the defendants William A. O'Neill et al.

(“Defendants”) on July 8, 1991, in this action.

I INTRODUCTION

Plaintiffs, young schoolchildren in the Hartford and West

Hartford public schools, have brought this lawsuit to vindicate

their personal rights to an equal opportunity for a free public

education, and to enforce the State's affirmative duty to provide

that opportunity. They have made four claims:

first, the defendants have permitted school districts

to emerge in the Hartford area that are sharply

segregated, de facto, on grounds of race and ethnic

background (Plaintiffs’ Complaint, Paragraphs 73-75);

second, although the defendants recognize that racial

and economic segregation has serious adverse

educational effects, denying equal educational

opportunity, they have permitted it to continue

(Plaintiffs’ Complaint, Paragraphs 76-78);

third, the segregation that has arisen by race, by ethnicity

and by economic status places Hartford schoolchildren at a

severe educational disadvantage, denies them an education

equal to that afforded to suburban schoolchildren, and fails

to provide a majority with even a “minimally adequate

education” (Plaintiffs’ Complaint, Paragraphs 79-80); and

fourth, under Connecticut’s education statutes, the

defendants are obliged to correct these problems, and their

failure to have done so violates the schoolchildren’s rights

(Plaintiffs’ Complaint, Paragraphs 81-82).

The remedy plaintiffs seek is a declaration by this Court

that the present circumstances violate the Connecticut

Constitution, and an injunction enjoining the defendants from

failing to provide equal educational opportunity.

In the defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment they claim

that (1) the conditions are not the result of state action, (2)

the state has satisfied its affirmative obligation and (3) the

controversy is not justiciable. To a large extent this motion is

simply the defendants’ latest effort to rehash their previous

arguments set forth in their Motion to Strike.

Issues (1) and (3) were explicitly raised in the defendants’

Motion to Strike, which this Court denied on May 18, 1990. Issue

(1), which concerns the construction that should be given to the

three state constitutional provisions in question, Article First,

$81 and 20, and Article Fighth, §l1, was discussed in detail at

pages 11-14 of this Court’s Memorandum of Decision on the

Defendants’ Motion to Strike. This Court indicated that a

conclusive disposition of this issue prior to trial would not be

appropriate. Likewise, the issue of justiciability was discussed

in detail at pages 5-11 of the Court's decision, with the same

result. These rulings being the law of the case, "a judge should

hesitate to change” the ruling unless there is “some new or

overriding circumstance.” Carothers vy, Capozziello, 215 Conn.

82, 107, 574 A.2d 1268 (May 22, 1990). The defendants point to

no new or overriding circumstance to justify reexamination of

these issues before trial. Indeed, in their 90-page brief, there

is not one case cited that has been decided since May 18, 1990.

The test for summary judgment is a strict one. Practice

Book §384 provides that summary judgment “shall be rendered

forthwith if the pleadings, affidavits and any other proof

submitted show that there is no genuine issue as to any material

fact and that the moving party is entitled to judgment as a

matter of law.” Lees v. Middlesex Ins. Co., 219 Conn. 644, 650,

A.2d (1991). The defendants must show the absence of

any genuine issue as to all material facts, which under

applicable principles of substantive law, entitle them to

judgment as a matter of law. To satisfy their burden, the

movants must make a showing that it is quite clear what the truth

is, and that excludes any real doubt as to the existence of a

- 4

genuine issue of material fact. Fogarty v. Rashaw, 193 Conn.

442, 445, 476 A.2d 582 (1984) (emphasis added). Fogarty is

directly applicable in this case. There the court held that

summary judgment was improper and did not even consider the

opposition papers because the papers filed by the moving party

were insufficient as a matter of law. Similarly, the papers

filed by the defendants herein fail to satisfy the minimum

threshold for the grant of summary judgment.

II. FACT 1 IS IRRELEVANT TO THE CLAIMS BEFORE THIS COURT

Defendants cavalierly assert the existence of three facts

that they claim are undisputed by plaintiffs. Closer scrutiny of

each of these, however, belies defendants’ conclusions in this

regard. Indeed, plaintiffs take serious issue with each “fact”

as stated by defendants. For purposes of defendants’ Motion,

however, it is neither timely nor appropriate for this Court to

resolve the factual dispute. The mere existence of even one

genuine issue of material fact is enough to defeat defendants’

Motion for Summary Judgment. Moreover, as the discussion below

demonstrates, even if there were no factual dispute, defendants

are not entitled to judgment as a matter of law.

Defendants’ “Fact 1”, set out at pages 6-9 of their brief,

is that they have not affirmatively assigned children to the

Hartford public schools based on their race, national origin or

socioeconomic status. This statement is neither relevant to

plaintiffs’ case nor accurate.

A. Intent

As plaintiffs have repeatedly maintained and as the

defendants specifically acknowledge in their motion,l it is the

present condition of racial segregation in the region’s schools

that violates the Connecticut Constitution as a matter of law,

and the harms that flow from the present condition of racial and

economic segregation that in fact deprive Hartford area school

children of their right to equality of educational opportunity.

The intent of the defendants is therefore immaterial.

Even if Fact 1 were considered material, that would

merely put the burden on the plaintiffs to provide evidence to

rebut that fact. The purpose of a summary judgment motion is to

determine whether there exists an issue of fact, not to try that

fact, Spencer v. Good Earth Restaurant Corporation, 164 Conn.

1844 197, 319 A.2d 403 (1972). See Conference Center Ltd. v.

TRC, 189 Conn. 212, 217, 228, "45% .A.2d 857 (1983) (issues

"necessarily fact bound require a full trial and preclude summary

judgment”); Batick v. Seymour, 186 Conn. 632, 645-46, 443 A.2d

471 (1982) ("genuine issue over the defendant’s intentions”).

N “[Tlhis is a case where the plaintiffs charge ‘de facto’, not

‘de jure’, segregation.” Memorandum in Support of Defendants’

Motion for Summary Judgment ("Def. Br."”) at 7.

B. State Action

Defendants have claimed that the requisite “state

action” is not present here, because, as they argue, the state

has taken no affirmative steps to cause segregation. As

plaintiffs have tried to impress upon the Court, the state's

argument has no basis in law. The state controls public

education, and the state has an affirmative duty to guarantee

equal educational opportunity. The extensive involvement of the

state satisfies every standard of state action of which

plaintiffs are aware.

The defendants misunderstand the concept of state action

as 1t applies to this case. While there is ample evidence of

state actions that caused the problems in the present case, proof

of such state action is not a necessary element for liability.

In Horton I, there was no finding that the state created the wide

variations in property tax revenues available to the various

towns. Yet, the Supreme Court found that the State bore the

affirmative responsibility, in providing a free public edubation;

to mitigate those private economic differences.

Even the case the defendants most heavily rely on,

Savage v. Aronson, recognizes “the burden imposed on the state by

our decision in Horton to insure approximate equality in the

public educational opportunities offered to the children through-

out the state;....” 214 Conn. 256, 286-87 (1990) (emphasis added).

Savage was a housing case. The 30-page opinion primari-

ly concerns procedural issues, the proper construction of state

housing statutes, and due process of law (pp. 257-284). The

Horton issue appears at the very end and the Supreme Court

disposes of it quickly on the ground that Horton does not

"guarantee that children are entitled to receive their education

at any particular school or that the state must provide housing

accommodations for them and their families close to the schools

they are presently attending.” 214 Conn. at 287. The plaintiffs

make no such claims in the present case. Savage does nothing to

advance the defendants’ cause; it reaffirms the vitality of

Horton.

As ‘this Court noted in ‘its decision on the Motion to

Strike (p. 12), the defendants are resurrecting Justice

Loiselle's. dissent in Horton v. Meskill, 172 Conn. 615, 658, 3756

A.2d 359 (1977)(Horton 1), that the constitution requires only

that education be free. The majority in Horton rejected this

interpretation of the Constitution, holding that public education

is "a fundamental right,” that “pupils in the public schools are

entitled to equal enjoyment of that right,” and that ‘any

infringement of that right must be strictly scrutinized;” 172

Conn. at 645, 646, 649. The court unanimously reaffirmed its

holding in Horton v. Meslkill, A9% Conn. 24, 35, 486 A.2d 1099

(1985) (Horton III) and restated this position in Savage v.

Aronson, 214 Conn. 258, 286, 571 A.2d 696 (1930).

As in their Motion to Strike, the defendants once again

strain to isolate constitutional provisions that, as Horton I and

Horton III held, must be read together. The State -- under

Article Eighth, $1, read in conjunction with Article First, $51

and 20 -- is "required to assure to all students in Connecticut's

free public elementary and secondary schools '‘a substantially

equal educational opportunity.’” Horton III, 195 Conn. at 35.

C. Affirmative Acts

Nonetheless, if defendants persist in this line of

argument, plaintiffs are prepared to show that defendants have

taken numerous actions that have “caused” or “contributed to”

segregation, and that defendants are responsible for existing

school boundaries that exacerbate segregation.

While defendants in the technical sense may not have

checked the race or ethnic status of any particular child before

assignment of that child to a particular school within Hartford,

the defendants by their “affirmative acts” certainly have

“confined” and perpetuated the confinement of Hartford children

in racially segregated schools.

It 1s clear from Defendants’ own documents that they

also had knowledge of the growing racial isolation within

Hartford city schools, and yet took no corrective action. As

early as 1909, the year in which the State changed its policy and

mandated student assignment coterminous with town district lines,

there was established a pattern of black migration and racially

identifiable housing within the city.

In 1969, the General Assembly officially recognized this

"growing racial isolation” (Report of the Governor's Commission

on Quality and Integrated Education, Dec. 1990, p. 1) in some of

its cities, including Hartford, and passed the Racial Imbalance

Law in an attempt to correct racial imbalances within a single

district. The Act has become an empty promise in Hartford,

however, since its breadth was limited to intradistrict

segregation and it took the State ten years to pass racial

imbalance regulations.

As outlined in Plaintiffs’ Amended Responses to

Defendants’ First Set of Interrogatories (attached to defendants’

brief as Exhibit 1), nos. 1l, 2, 3, 4, there are numerous other

"affirmative actions” by the State that have perpetuated the

segregation of Hartford's school system, including the state

requirement that school-age children attend public school within

the school district where they reside, p. 8, the perpetuation of

a massive program of new school construction and school additions

or renovations in Hartford and the surrounding communities with

direct knowledge of the increasing segregation in Hartford area

schools, p. 9, the establishment and maintenance of an unequal

and unconstitutional system of educational financing, p. 16, and

the contribution to racial and economic segregation in housing,

P. 18.

These actions stand in contrast to other compelling

circumstances where the State has passed appropriate legislation

to allow students to cross district lines. ee C.G.S. §10-39 et

seg. (Regional school districts); C.G.S. §10-76d(d) (special

education); and C.G.S. §10-95 et seg. (vocational education).

Indeed, the Governor's Commission Report even suggests that

traditional school registration policies of local school

districts should be changed to allow attendance at schools

nearest a parent or guardian's place of employment (Report, p.

5 Yo

III. WHAT THE DEFENDANTS CHARACTERIZE AS FACT 2 IS AN ATTEMPT TO

AVOID THEIR GOVERNMENTAL ROLE TO EFFECTIVELY ADDRESS

UNCONSTITUTIONAL SITUATIONS

Defendants assert, as an “undisputed fact,” that "there is

not now, and never has been, a distinct affirmative act, step, or

plan, which, if implemented, would have ‘sufficiently’ addressed

the conditions about which the plaintiffs complain.”

The defendants do not seem to understand that they, not the

plaintiffs, have a duty under the Constitution. The gravamen of

the plaintiffs’ claims is that the present condition is

unconstitutional and the defendants have a duty to change the

condition; plaintiffs are not complaining about what did or did

not happen in the past. There certainly was no suggestion in

Horton I or III that Barnaby Horton had a duty to prove what the

defendants could have done to solve the school finance problem

before he brought his lawsuit.

The defendants’ real complaint may be that the plaintiffs

have set forth no plan to solve the problem in the future. But

that has to do with remedy, not liability. The plaintiffs will

be prepared to discuss the remedy when the Court wishes to do so,

but a motion for summary judgment is surely not the appropriate

time.

In any event, the defendants’ assertions are untrue. The

history of racial segregation in Hartford's schools and the

failure of its students to achieve minimally adequate education

have been documented in task force report after task force report

since 1965. Generated as an essential part of these reports are

recommendations to remedy the problems which, for the most part,

have been largely ignored. ee Plaintiffs’ Amended Response No.

5 to Defendants’ First Set of Interrogatories, attached to

defendants’ brief as Exhibit 1. For example, in 1965, the

Committee of Greater Hartford School Superintendents put forth a

Proposal to Establish a Metropolitan Effort Toward Regional

Opportunity (METRO). The Legislative Commission on Human Rights

and. Opportunities in 1968 issued a Plan for the Creation and

Funding of Educational Parks. The Hartford Board of Education in

1970 issued a report entitled “Recommended Revision in School

Building Program.”

In 1988, the defendants themselves issued a “Report on

Racial/Ethnic Equity and Desegregation in Public Schools,” which

recommended, inter alia, that the state,”through administrative

and legislative means, endorse the concept of ‘collective

responsibility’ for desegregating the public schools of

Connecticut” (p. 11); "make available substantial financial

incentives to school districts that plan and implement voluntary

interdistrict programs” (p. 18); and “undertake broad-based

planning with other agencies concerned with housing,

transportation and other factors that contribute to segregation”

(D+ 1319), None of these recommendations have been fully

implemented. A year later, defendants reinforced the earlier

recommendations in a report titled “Quality and Integrated

Education: Options for : Connecticut,” which included such

recommendations as a challenge program that would serve as a

corporate component of the Interdistrict Cooperative Grant (p.

35); enhancement of Project Concern (p. 36); refinement of summer

school grant program (p. 36); development of magnet schools (p.

39): advancement of school construction options (p. 39) and

better recruitment of minority teachers. (p. 40). Again, in the

two years since its issuance, the recommendations have not come

to fruition.

13a

Most recently, although the Report of the Governor's

Commission Report on Quality and Integrated Education, issued in

December 1990, made many recommendations, (pp. 12-31), there has

been virtually no agency or legislative response to these in the

seven months since their issuance. Indeed, the legislature has

flagrantly ignored some of the recommendations, including one to

"increase funding to $2 million’ for interdistrict grants? and

one to expand the Summer School Grant Program. 3 Report, pp. 15,

There have been no regional efforts as described on page 12 nor

has there been establishment of any Interdistrict Transfers Grant

program as recommended on page 14. The State has failed to fund

any significant expansion of Project Concern and has failed to

fund any efforts to “reverse” the program in order for suburban

students to attend school in Hartford. See Affidavit of John

Allison, Executive Director of Capitol Region Education Council,

attached hereto as Exhibit A, 94, p. 2. Only a few interdistrict

programs funded by the state even apply to Hartford and all were

funded at a level less than requested. Id. Other grant

applications to address the racial and economic isolation, such

as the Saturday Academy, Center for Regional Educational Policy

and Action, Program to Advance Quality Integrated Education and

2 The legislative response fell approximately $500,000 short of

this recommendation. See Affidavit of John Allison, €8.

3 The legislature failed to allocate any monies for this

program. See Affidavit of John Allison, 418.

Performance-Based Consequence-Driven Schools all went unfunded.

Id. Recommendations to “provide, through the appropriate health

department staff, preventive health-care programs at all schools

where there is a significant percentage of low-income students;”

and to “provide at least one year of preschool for all at-risk

students,” Report, p. 20, have fallen on deaf ears.

IV. THE ITEMS LISTED IN FACT 3 ARE INSUFFICIENT TO MEET THE

DEFENDANTS’ BURDEN TO PROVIDE AN EQUAL EDUCATIONAL

OPPORTUNITY FOR ALL STUDENTS.

Lastly, defendants claim that plaintiffs do not dispute the

fact that “the General Assembly has adopted and the defendants

have implemented legislation designed to address the conditions

about which the plaintiffs complain.” Plaintiffs make no such

concessions.

In light of the admitted fact that the Hartford public

schools are about 90% minority and that the surrounding public

schools, except for Bloomfield and Windsor, average about 90%

non-minority (see defendants’ answer to 133 of the Complaint),

the defendants’ 29-page list of “facts” supports plaintiffs’

position that the defendants have made a wholly inadequate

attempt to address a monumental violation of constitutional

rights. The list on its face provides no basis to enter a

summary judgment.

A. Not A Funding Case

The defendants repeatedly forget that this is not a

funding case. The fact that the state may have directed and

continues to direct extra dollars into the Hartford system may

have been a plausible defense if this case was a repeat of Horton

v., Meslkill. But the funding formula for urban schools is not

what 1s directly at issue here. It is the racial, ethnic and

economic segregation which has caused the unequal educational

opportunities that are at the heart of plaintiffs’ case. Even if

some of the statements are material on finance issues, they fail

to address all of the material issues. The statements, for

example, do not address the detrimental effects of the racial and

socioeconomic segregation in the schools of the Hartford area.

See Affidavit of Hernan LaFontaine, former Superintendent of

Schools, Hartford, attached hereto as Exhibit B.

Moreover, the defendants’ evidence is silent on the

issue of causation, for even if every factual statement made by

the defendants is true, there remains a factual question about

what results have been or will be accomplished.

in Lomangino v. LaChance Farms, Inc., 17 Conn. App. 436,

553 A.2d 197 (1989), the court reversed a summary judgment for

the defendant because the defendant did not eliminate factual

questions concerning the issue of proximate cause. Quoting four

Supreme Court cases, the Appellate Court noted that “proximate

cause is ordinarily a question. of fact.” 17 Conn. App. at 440.

Finally, as presented below, an analysis of these

“facts” demonstrates that there is no conceivable basis for

summary judgment.

B. Failure to Address Hartford's Special Needs

The present financial commitment by the State to

Hartford has no significant impact on the educational advantages

that the children in the Hartford system enjoy. While it is true

that Hartford receives a larger share of funding as compared to

its suburban counterparts, Hartford's students start school with

a number of burdens unlike those of any surrounding community.

For instance, Hartford does receive substantial funds in special

education, but no school system in the surrounding towns has a

school population with such numbers of special education

students. Similarly, while the State funds Hartford's bilingual

programs, there is only one other system in the region that has

had a sufficient number of limited English proficient students to

warrant state funding for bilingual education. See Affidavit of

Catherine Kennelly, Director of Financial Management, Hartford

Public Schools, attached hereto as Exhibit C.

A careful analysis of Defendants’ Exhibit 4 provides

further evidence as to the ways in which this Exhibit either is

misleading or grossly overstates the impact on the Hartford

- 17

school system. ee Affidavit of Catherine Kennelly, attached

hereto. For instance, while there appears to be a slight

increase in the amount of money the state has given to Hartford

pursuant. to the Priority School District Grant and Drop-ocut

Prevention Grant, these figures on their face do not take into

account inflation as well as contracted salary increases. As a

result, there is actually a net decrease in terms of staff

avallability. Id. at p. 2. As to the amount of state aid as 2

percentage of the overall budget, “there was a 3.24 percentage

point increase in Hartford while a 2.76 percentage point increase

in the suburbs. Therefore, the relative level of state funding

has remained approximately equal, even though Hartford's system

has grown substantially and at a much faster rate than the

suburban communities.” Id. at p.s2. As to the EERA funding,

some suburban communities received larger increases than Hartford

on a percentage basis. Id. at p. 3.

Furthermore, plaintiffs will present evidence that the

educational resources currently provided through the combined

efforts of the State are insufficient to meet the needs of

Hartford schoolchildren and unequal as compared with educational

resources available to students in suburban towns. As set out in

the attached affidavits of Hernan LaFontaine and Catherine

Kennelly, the high concentration of poor and at-risk students in

the Hartford district creates additional demands on the Hartford

system. These demands are not met by current funding and, in

attempting to address these demands, educational resources are

diverted from regular education. More importantly, as set out in

Mr. LaFontaine'’s affidavit, and to be further discussed by

plaintiffs’ other expert witnesses, while increased targeting of

financial resources in the future would help to remedy part of

the educational harm alleged by plaintiffs, there would still

remain serious harms. Even 1f the programs set out in the

defendants’ brief were funded at an adequate level, they would

only address part of the problem.

C. Benefit To Places Other Than Hartford

The State's efforts in other regions of Connecticut that

are the beneficiaries of many of the interdistrict desegregation

grants are irrelevant for the purposes of this lawsuit. The

plaintiffs challenge Hartford's racial, ethnic and economic

isolation, and the fact that the state may be funding an

interdistrict cooperative program in Fairfield, New Haven, or

Middlesex Counties is immaterial. See Affidavit of John Allison,

attached hereto as Exhibit A, €5. (Only seven of the thirty-four

interdistrict programs listed by defendants apply to Hartford

school system.)

D. Failure To Address Racial Segregation.

Legislative efforts to address the specific problem of

racial isolation by the Connecticut legislature have been dismal

at best. It took the legislature over ten years to pass racial

imbalance regulations at a time when it was too little, too late.

The interdistrict programs that have been funded, such as Project

Concern, are minimal in comparison with the need, and touch only

a small fraction of students within the Hartford system. See

Affidavit of John Allison, attached hereto as Exhibit A. See

also Governor's Commission Report, p. 15 (“Because of limited

funding, however, only 27 programs [statewide] were awarded

grants, and they received only 63 percent of the amount

requested. State funding limits forced cutbacks in many of these

programs, some of which were in their third year of funding and

had student waiting lists.”) Several of those that have been

started within the past few years, such as the Hartford/West

Hartford Montessori program and the Friday Academy have been

discontinued or have seen their funding cut or eliminated. See

Affidavit of John Allison, attached hereto as Exhibit A.

In addition, focusing only on the past ten years, many

bills have been unsuccessfully introduced in the legislature to

address the problem. (See attached Exhibit D.) They have ranged

from SB-235 "An Act Concerning Funding for Local Desegregation

Efforts” (1991), to HB-5448 “An Act Concerning Racial Segregation

in Public Schools” (1989), to HB-5378 “An Act Concerning Funding

for Local Desegregation Efforts (1988), to HB-5755 "An Act

Concerning Interdistrict Cooperative Efforts to Remedy Racial

Imbalance” (1981). All have died either in Committee or on the

floor.

The State's position, as a factual (and legal) matter,

that the legislature has taken appropriate legislative steps

flies in the face of these failed efforts.

V. THE DEFENDANTS’ ARGUMENT ON NON-JUSTICIABILITY IS NOT

SUPPORTED BY JUDICIAL AUTHORITY

Although the defendants present a lengthy catalog of state

programs, the thrust of their brief seems to be the question of

justiciability. What the defendants are really saying is that

the unconstitutional school situation in the Hartford area

presents a difficult societal problem and the courts should stay

out of it.

The problem with this philosophy is the lack of judicial

authority to support it. Rather the courts have a special power

and obligation to see that all children in the state receive an

equal opportunity to a free public education.

This Court has already discussed the subject af

justiciabllity in its 1990 ruling. At page 8, this Court stated:

The fact that the legislative branch is given plenary

authority over a particular governmental function does

not insulate it from judicial review to determine

whether it has chosen "a constitutionally permissible

means of implementing that power.” Immigration &

Naturalization Service v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919, 940-41

(1383). “"[Tlhe legality of claims and conduct is a

traditional subject for judicial determination”, and

such adjudication may not be avoided on the ground of

nonjusticiability unless the particular function has

been assigned "wholly and indivisibly” to another

department of government. Baker yv, Carr, 369 U.S. at

245-46 (Douglas, J. concurring).

In light of Horton I and III, the defendants cannot possibly

claim that guaranteeing an equal opportunity to a free public

education has been assigned ‘wholly and indivisibly to’ the

Legislature.

Article Eighth, §1, states that “the general assembly should

implement this principle [free public schools] by appropriate

legislation.” The word "appropriate” signifies that legislative

discretion must be properly exercised; the qualifier plainly

contemplates judicial oversight of the appropriateness of

legislative action. This reading is fully supported, once again,

by Horton I. There, the Connecticut Supreme Court employs this

precise constitutional phrase as a basis for striking down

Connecticut's former system of school finance:

[Tlhe...legislation enacted by the General Assembly to

discharge the state's constitutional duty to educate

its children...without regards to the disparity in the

financial ability of the ‘towns to finance an

educational program and with no significant equalizing

state ‘support, "is not “'aporopriate legislation’

(Article Eighth, §1) to implement the requirement that

the state provide a substantially equal educational

opportunity to its youth in its free public elementary

and secondary schools.

172 Conn. at 649 (emphasis added). Under no coherent theory of

justiciability could the courts of Connecticut have jurisdiction

to review the General Assembly's judgments on school finance, yet

be disempowered as a matter of djurisdiction from reviewing the

legislature’s Article Eighth, $1, duties on another ground.

Either §1 vests exclusive, unreviewable authority in the

legislature, or it does not. As Horton I demonstrates, the

Supreme Court has already authoritatively answered that question.

In one respect the present case ‘is a stronger one for

justicliability than Horton. While Horton relies on the

construction of Article Pirst, $§1 and 20,-and Article Eighth,

§1, the present case, in addition to the same reliance, relies

independently on the history and language of Article First, §20.

The Supreme Court recently stated:

We have also, however, determined in some instances

that the protections afforded to the citizens of this

state by our own constitution go beyond those provided

by the federal constitution, as that document has been

interpreted by the United States Supreme Court.

State v., Marsala, 216 Conn. 150, 160, 579 A.2d 58 (1990). Accord

Horton I, at 641-42: State v., Barton, 219 Conn. 529, 54s,

A.2d (1991). Indeed, in talking about “the full panoply of

rights” that Connecticut citizens "have come to expect as their

due,” Barton cites Horton I.

Article First, §20 states that “no person shall be denied

the equal protection of the law nor be subjected to segregation

or discrimination in the exercise of his civil or political

rights because of...race....”

"It cannot be presumed that any clause in the Constitution

is intended toc be without effect;....” Marburv wv. Madison, 1

Cranch:138, 174. (1803), "Unless there is some clear reason for

not doing so, effect must be given to every part of and each word

in the constitution.” Stare v. Lamme, 216 Conn. 172, 177,579

A.2d 484 (1990).

In Lamme, the Supreme Court examined the text and history of

Article First, §8, to determine if more rights should be given to

Connecticut citizens than under the United States Constitution.

If we analyze the text of Article First, §20 carefully, we see

that segregation and discrimination are treated as in addition to

equal protection of the law, and that segregation is treated as

in addition to discrimination.

The plaintiffs claim that the right to a minimally adequate

education is one of their civil rights. This includes the right

to.-be free from a segregated school system. As Brown v. Board of

Education itself stated 35 years ago, separate schools are

inherently unequal. 347 U.S. 483, 495 (1954). Article First,

§20, was added to the Connecticut Constitution in 1965. In 1965,

the framers knew about Brown and knew about prohibited

discrimination, but they also prohibited segregation.

The term “segregation” in §20 was specifically debated at

the 1965 Constitutional Convention. Not only was it debated, but

the word was actually deleted in Committee, and reinserted on the

floor of the Convention after debate on its reinclusion. See

"Journal of the Constitutional Convention” at 174. See also pp.

691-632 ("We have spent a lot of time on this particular

provision... .”).

The debate demonstrates that the purpose of including the

term “segregation” was “so that it [§20] would not be interpreted

as an exclusion or limit rights” (p. 691) and to provide as broad

and as expansive rights to equal protection as possible. See

remarks of Mrs. Woodhouse (p. 691)(Constitution should

“unequivocally oppose the philosophy and the practice of

segregation’), Mr. PEddy (p. 691), Mr. Kennelly (p. 63%2)(egqual

protection clause "all inclusive” and “the very strongest human

rights principle that this convention can put forth to the people

of Comnecticut’y, and Mrs. Griswold (p. 693). In his closing

remarks, former Chief Justice Baldwin described §20 as “something

entirely new in. Connecticut’ -(p. 1192). The debate also

expressly acknowledges that the new section, including the

prohibition against “segregation”, would apply to “rights of

freedom in education.” (Page 694).

The term “segregation” was commonly used in 1965, as it o

today, to describe the actual separation of racial groups,

without regard to cause. Thus, in the influential Coleman Report

in 1966, segregation is described as a demographic phenomenon:

The great majority of American children attend schools

that are largely segregated -- that is, where almost

all of their fellow students are of the same racial

background as they are.

James Coleman et l., Equality of Educational Opportunitv at 3.

Furthermore, at the time the Connecticut Constitution was

adopted, the United States Supreme Court had not yet incorporated

an intent requirement into the Equal Protection Clause and the

lower courts were divided as to whether municipalities could be

held liable for purely de facto school segregation. Against this

background, if the framers had sought to limit the meaning of the

term segregation to “intentional” or “de jure” actions, they

certainly would have done so explicitly. Section 20 is an

appropriate and independent basis for the plaintiffs’ claims.

The only case the defendants seriously rely on for their

justiciability argument is Pellegrino v. O'Neill, 193 Conn. 670,

480 A.2d 476 (11984). As this Court noted, Pellegrino is a

plurality opinion, with a strong dissent by the current chief

justice.

Pellegrino involves a claim under Article First, §10, that

civil trials were being unconstitutionally delayed by the failure

of the Legislature to provide a sufficient number of judges to

handle the backlog of cases. The plurality in Pellegrino were

understandably reluctant to “augment their numbers by writs of

mandamus,” 193 Conn. at 678, because to do so, they reasoned,

would be “to enhance [their] own constitutional authority by

trespassing upon an area clearly reserved as the prerogative of a

coordinate branch of government.” Sd. No similar danger of

institutional self-aggrandizement exists in this case.

Furthermore, Horton I was reaffirmed after Pellegrino in Horton

III, which does not even mention Pellegrino. Pellegrino is

inapplicable to plaintiffs’ right to an equal opportunity for a

free public education.

Chief Justice Peters, the author of Horton III in 1985,

stated one year later:

Third, courts must respond to. changes in our moral

environment, to greater sensitivity to the rights of

minorities and women and children and the aged and the

handicapped and students and teachers -- the list,

thank goodness, keeps growing.... That litigation

increasingly turns to .state law, and state

constitutions, as federal courts retreat from the

commitments of the Warren Supreme Court.

Not all litigation, however, permits deference or

allows invocation of the passive virtues. In the face

of uncertainty, courts must resolve some questions,

regrettably, because courts are not the best, but the

only available decision-makers.... When litigants have

exhausted other channels, however, when the political

process is unresponsive, and when other situations in

society have, in effect, thrown in the sponge, it is

courts that must respond to our society's self-

fulfilling prophecy that for every problem, there ought

to be a law.

Peters, “Coping with Uncertainty in the Law,” 19 Conn.L.Rev. i

3,:..6+:{1986). See also Peters, “Common Law Antecedents of

Constitutional Law in Connecticut,” 53 Albany L.Rev. 259 (1989).

We are told that "the Court stands at the crossroads in this

case.” (Defendants’ br. p. 5). What the defendants see is just

a mirage. The crossroads still lie ahead -- at the end of a

trial on the merits. The motion for summary judgment should be

denied.

Li ftusz—

Lr Horton

iL A. Knox

Moller, Horton, & Fineberg

90 Gillett Street

Hartford, CT 06105

A : il Ra

Y ida 0 Dvn

Respectfully Submitted,

A mn Ell.

Martha Stone

Connecticut Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

32 Grand Street

Ron Ellis

Julius L. Chambers

Marianne Engelman Lado

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

Chit Totals

iversity of Connecticut

School of Law

65 Elizabeth Street

Hartford, CT 06105

Le. teva).

Helen Hershkoff

John A. Powell

Adam Cohen

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

Philip D. Tegeler

Connecticut Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

32 Grand Street

Hartford, CT 06106

Wille dd (oligo,

Wilfred Rodriguez U ~~

Hispanic Advocacy Project

Neighborhood Legal Services

1229 Albany Avenue

Hartford, C7 06112

inn Kcr,

Jerny Rivera

Ruben Franco

Puerto Rican Legal Defense

and Education Fund

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

CERTIFICATE OF SFRVICE

This is to certify that one copy of the foregoing has been

mailed postage prepaid to John R. Whelan and Diane W. Whitney,

Assistant Attorney Generals, MacKenzie Hall, 110 Sherman Street, Bartford, CT 06105 this 20Dyay of September, 1991

[tee MY

Wesley W. GE ioe