Brief in Response to Petition for Writ of Certiorari Including Objections

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1969

157 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. Brief in Response to Petition for Writ of Certiorari Including Objections, 1969. dfb1f81d-cf67-f011-bec2-6045bdd81421. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b4b298d9-bb70-4dc4-8f7a-12de597b7ff4/brief-in-response-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-including-objections. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

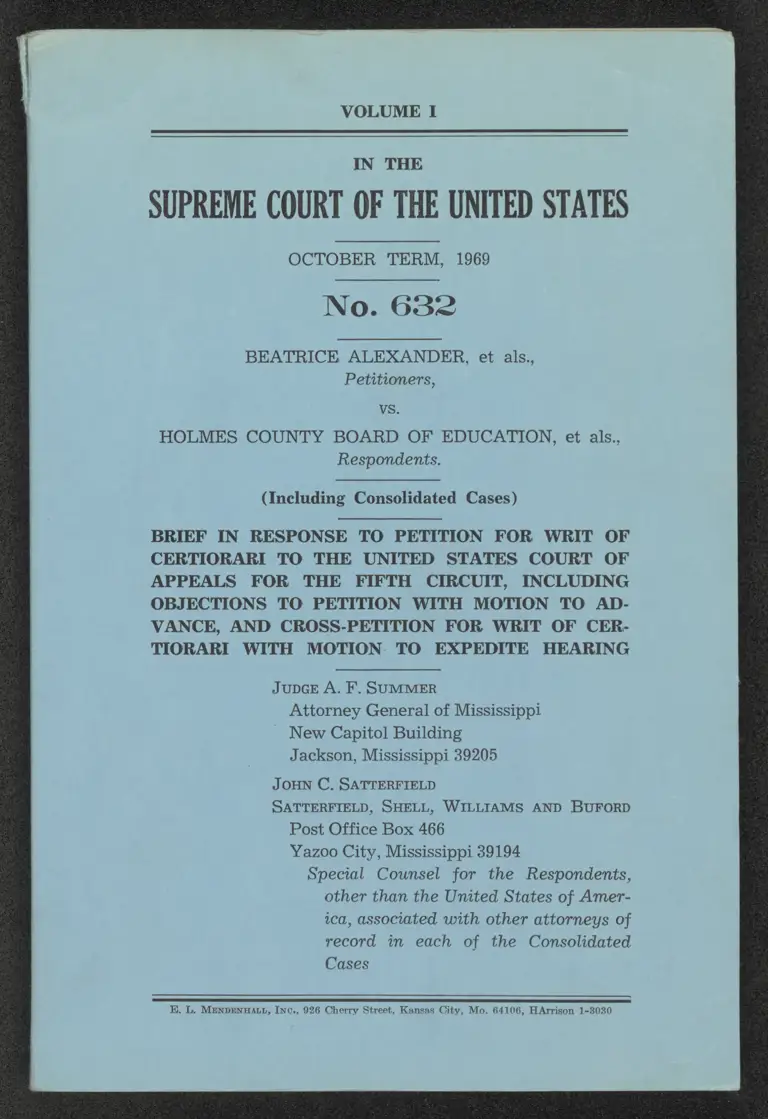

VOLUME 1

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

No. 632

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, et als,

Petitioners,

VS.

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et als.,

Respondents.

(Including Consolidated Cases)

BRIEF IN RESPONSE TO PETITION FOR WRIT OF

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT, INCLUDING

OBJECTIONS TO PETITION WITH MOTION TO AD-

VANCE, AND CROSS-PETITION FOR WRIT OF CER-

TIORARI WITH MOTION TO EXPEDITE HEARING

JUDGE A. F. SUMMER

Attorney General of Mississippi

New Capitol Building

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

JOHN C. SATTERFIELD

SATTERFIELD, SHELL, WILLIAMS AND BUFORD

Post Office Box 466

Yazoo City, Mississippi 39194

Special Counsel for the Respondents,

other than the United States of Amer-

ica, associated with other attorneys of

record in each of the Consolidated

Cases

E. L. MENDENHALL, INC., 926 Cherry Street, Kansas City, Mo. 64106, HArrison 1-3030

INDEX

Objection to Motion to Advance and to the Peti-

tion for Writ of Cerliorar] ..... cnn ccstocensttinns

II. Response to Petition for Writ of Certiorari ..............

111.

1.

2.

3.

Preliminary Statement... i... 0.

Question Stated by Movants and Petitioners ....

Question Actually Presented by Motion and Pe-

RE ONY io Corea e ct mrciass curcanae ehsssnias mista sod R as dbsnmsgaias insane

. The Divergent Plans of Desegregation Filed by

HEW and the School Districts Have Not Been

Considered or Approved by Either the District

Courtorthe Court of Appeals ol. lini...

« DIHOMENE OF FOCUS .ccoecce mii ssermsinscriztssinsatosresieraes

. The Order Entered by the Court of Appeals on

August 28th Is Based upon a Finding of Fact,

Supported by the Record, Made by Both the

District Court and Court of Appeals, and Should

Not Be Disturbed i ..........ccosiomiesmissnict-oeinesocee

. Vacating the Amendment of August 28th Will

Accomplish No Appreciable Expedition of Ac-

tion in These School Suits and Would Be Detri-

mental to the Interest of All Students ................

. The Petition for Writ of Certiorari Being Di-

rected to the Amendment of a Judgment, the

Same Should Be Dismissed or, in the Alterna-

tive, Granted As Being Applicable to the Entire

JUAZMENE . LL... lcimenmitunsiosmvsonioneerh alte etesobins ens dnrstas

Cross=Petition for Writ of Certiorarl i......coo it

1

2.

Judgment and Opinion Below...............................

Jurisdiction ......:: SE Le A LIOR RL

14

16

17

23

26

IT

90

1

ov

r

i

to

INDEX

Reservation ol Bighis «oot anne

. Questions Presented for Review .........oooeeeeeo..

. Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved

: Preliminary Statement i ionic iiiadenss

ttement OF Taets ea

Argument Amplifying the Reasons Relied Upon

for Allowance of the Cross-Petition for Writ of

TT ar Ln ee EE ee eg

(1) The school districts have followed their

Constitutional duty as announced and as

changed from year to year by the Supreme

Court and the Court of Appeals of the

Firth Circuit. The districts are now char-

acterized as “reluctant” and “recalcitrant”

because total compulsory integration re-

moving or substantially diminishing racial

imbalance has not been already achieved

“after. 15 YEars? .....cioiinimmn

(2) A freedom of choice plan is the proper ve-

hicle to set up and maintain schools con-

forming to all Constitutional guarantees and

when such plan and the school system are

administered fairly and without discrim-

ination, all vestiges of a dual discriminatory

racial school system are eradicated ...............

(3) The construction by the Court of Appeals

of the Fifth Circuit of the application of

Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to

public schools, announced in Hinds County

and other cases, conflicts with decisions of

IS Coutts ee

(4) The Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit is

in direct conflict with the other Circuits.

Jefferson I and Jefferson II (as gradually

expanded and varied by sixteen panels)

now require compulsory integration in the

student bodies and faculties of all schools,

leading to the ultimate end of racial balance

36

36

47

65

72

INDEX III

(5). Best of {8018 imi ennoisiimsimidinnssnitnestisntsiate 84

Exhibit A—Petition for Rehearing in Banc and for Stay

of Proceedings in the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Mississippi, or, in the

Alternative, for Recall of Mandate of This Court ........ le

Exhibit B—Portions of Testimony in the United States

of America v.. Hinds County School Board: ............... 21e

Exhibit C—DMotion in the Court of Appeals, Letter from

Robert H. Pinch, and Amended Order........ccoceeneoniss 35e

Exhibit D—Motion by the Defendants in the Above

Styled Consolidated Cases Joining in the Motion

Therein Filed by the Attorney General of the United

States in Behalf of Secretary Robert H. Finch of the

Department of Health, Education and Welfare and

the United Siotes Of AMETICH. ..... tcoimimmsidiiiietuiosesiibisumedus 40e

Cases and Other Authorities

Acree v. Richmond County, 399. F.24 11. (1968) ......... 74

Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181 (5th Cir. 1968) ...........

We hn LLIN Se we a 15,53,57,69,70,71,73,75,%8, 79

Armstrong v. Bd. of Ed. of the City of Birmingham,

303 Bod 47 (1864)... 43

Augustus v. Bd. of Public Instruction of Escambia

Cty Fla. 300 F.2d 332 (1902)... 41

Avery v. Wichita Falls Ind. Sch. Dist., (1956) 241

B2d 230. a ENT GH 66

Bell v.. Gary," {7th Cir. 1963), 324 F.2d 209, Cert,

denied, IT UBL020 Li i 74

Berenyi v. District Director, 87 S.Ct. 666, 385 U.S. 630,

LT LEBA24 088 (1967) rt 25

Boykins v. Fairfield, 399 F.2d 11 (1968) wooo 74

Iv INDEX

Broussard .v.. Houston. Ind. School. District, 395 F.24

817 Een 51,52, 65, 74

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 75 S.Ct.

755.80 LET 1085 CUO) «crn

a 16, 25, 26, 39, 40, 41, 46, 47, 56, 65, 66, 81

Brown (II) v. Bd. of Ed., 347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. 686,

08 EA: 00 8 .viuncsrineszass ssssomreassssssmssior hentnssngssbusasssst 47-48, 65, 66

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Bd., et als., 303 F.2d

AQ C1962) io di.ochivisess cobiotosnvh toni tosiiertiieluianeid dota 41-42

Calhoun, et als. v. Latimer, et als., 321 F.2d 302 (1963) 42

Carry. Monigomery Cty., 23 1L,.¥d.24 263 ............ 56, 67, 68, 69

Case Co. v. Borak, 84 S.Ct. 1554, 377 U.S. 426, 12 L.Ed.

rr 0 ETAT LL TEI COTE G0 SRT be OC SE NES lt ENOL 25

Clark v. Bd. of Ed. of Little Rock School District, 369

F.2d 661 (1966), Rehearing denied, 374 F.2d 569

A RE RA Bl En RL SE 60, 61, 74, 82

Cooper v. Aaron, 3583 US, 1 (1958) ........... 26, 48, 60, 65, 66

Cumberland Tel. & Tel. Co. v. Louisiana Public Serv.

Com., 67 L.Ed. 217. (1922) 26

Davis v. Bd. of School Commissioners of Mobile Cty.,

B04 TO BOB coeesrirrrssroisviiotsmmsssorims tines turns vse dinasstscassts 45

Deal v. Cincinnati, 369 F.2d 35 (6th Cir. 1966) ....74, 77,78

Downs v. Bd. of Education of Kansas City, 336 F.2d

988 (1964), cert. denied, 380 U.S. 914, 85 S.Ct. 939,

13 1.Ed.24.800 (1963) ....... iio iesissiniinioeres 74, 80-81

Duval v. Braxton, 402 F.2d 900 (1963) ........cccererrnes 43, 57, 73

East Baton Rouge Parish School Bd. v. Davis, 287 F.2d

2 tL TET os LIED DE I hi 41

Gaines v. Daugherty Cty. Bd. of Ed., et als., 329 F.2d

823 (1964) 334 F.9% G38 (1064) .........cvesicuncsiierr 43

Goss v. Bd. of Ed. of Knoxville, Tenn., 406 F.2d 1183

HE Ml NO dE 48, 56, 57, 60, 61, 65, 66, 74, 76, 77, 18

INDEX Vv

Graves v. Walton Cty., 403 F.2d 139 (1963) ............ 57,711,173

Great Atlantic '& Pacific Tea Co. v. .Supermarket

Equipment Corp., 71 S.Ct. 127, 340 U.S. 147, 95 L.Ed.

162 (1950) pon.iotci otitis. cusionesdtiatdiorthe srt chon vipritursspon inns 29

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968)

Ahr eeidins 25, 26, 47, 48, 49, 50, 56, 57, 65, 67, 69, 74, 75, 17

Holly, 5%. Helen, 287 BaZa 3705. ati. bcsnenseseiien 73,75, 79

Hampton v. Choctaw County (Not yet reported) 70,74, 78

Kellogg, et als. v. Hicks, et als., 52 S.Ct. 450, 283 U.S.

502 70- Ted, 903 (193 reer teresnss 25

Louisiana State Bd. of Ed., et als. v. Allen, et als., 287

£2432... inn Re PR fa. BO MOR Rin 41

Louisiana State Bd. of Ed., et als. v. Angel, et als., 287

F.2d Beans tng { 5 RX 41

Lacy: V. Adoms; 134 F.SUPP.O23D .cocetibuitiiioiitsossaain aries 26

Mapp v. Bd. of Ed. of Chattanooga, Tenn., 373 F.2d 75

ShuhLixab a csugsshpeaas gash AEE SAN ta nE SetRaRAAI ATOR OPEN SE Ress STR RSs 74, 81

Meredith v. Fair, Q. JuE3.20.44 ......cocnmeeesecnssissisissescorvsenessds 25

Monroe v. Bd. of Com. of City of Jackson, Tenn., 380

F.20..955.. (1087). ...oressessescessessescessessotsavssesrsimmttmastitmnct is

Soon eriss ess eran 37, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 57, 58, 60, 65, 67, 69, 74, 75

Plessy .v. Ferguson, 163 1U.8.- 537,616 8.C1.i'1138,°41

L.Ed. 200 (1896)s ...... oi sunumses iE ogstssthossstnsds-—tanesatsutssnlic-sascn 41

Raney v. Gould, 391 U.S. 443, 20 LEd.2d 727 cover...

47,48, 49, 50, 57, 65, 67, 69, 74, 15

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Sep. School District, 348

F.2d. 729. (1908) -cocismisssicimisicuiisiinsiitotintasintistuitssetinmmmnt tis 44d

Springfield School Committee v. Barksdale, 348 F.2d

SOT oneonsessecinsacnnrnsiunnssisersasnmmsemsarssmchs iii vatisdds dodo} cums Pees 74

As re 66

VI INDEX

U. S. Alkali Export Assn. v. U. S., 325 U.S. 196, 89 L.Ed.

BUTI L PU RL SE iE eal De Ee 26

U. S.. A. v. Baldwin Cty., Nol yet reported... 74

U. S.A. v. Bd. of Bd Pollc County, 395 F.2d 66 ............... 70

U.S. A. v. Cook Gonpt, 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir., 1968)

A ee a a ET EE on 74, 719

U. S. A.v. Greenwood, 406 T.24 1086 (1969) ............... 57,73

U.S: A.v. Indionola, 410 P.24 626 (1969) .................... 73.95

U.S. A. v. Jefferson (1), 372 B.24.836 ....o titi

a 31, 54, 58, 65, 66, 70, 72,73, 74

U.S. A. v. Jefferson (11), 330 F.24 335 .......... 31, 38, 39, 46, 51,

i oaeca Lows fire siupssieseua 54, 57, 58, 61, 65,066,467, 63,72, 73, 74,15

U.S. A. v. Jefferson (111), (1969) Not yet reported ...... 5

U.S. A. v. Jefferson (IV), (1969) Not yet reported ....71, 74

Civil Righic Act of1964 Title VI... 0 eli. 62

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Subchapter IV—Public Educa-

T1311 Dordt LE AR CHE 0 geht Le LHe kL RL 32

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Subchapter V—Federally As-

SISted PrOSTamNS oro enhienis ish bsiihntisis. dian dutoh Seseat dd har 33

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Subchapter VI—Equal Em-

Ployment Opportunities .........-.l ein Sn nL 33

Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, Rule 11 _....._.... 7

Pub.L. 88-352, Title 4, Secs. 401(b), 407 (a), 410 ........ 83-84

ER UD SR I 84

RL ID el A RR i LL ee 84

Supreme Court BUle-d2.0r o.oo bis msikii tome: sinetisl 6

Supreme-Court-Bule-20 ne ann 3,4,95,30

Supreme Court Bulle de i 6, 28

Supreme Court Bulle 21.4 ............ccicsoemmcssmiamioseassrascssscnsensons 8,11

Supreme Court Rule 24.2... oe oecereeesemeraeevnans aimns 3

US.Ci: Title 38, Seca d28d: (1) in.oiiin.isiitinisisismmisiiiiinm 30

USC. Title 42 See, 2000c(h) recon irrareiaboneaseisens: 83

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

No. 632

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, et als.,

Petitioners, :

VS.

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et als.,

Respondents.

JOAN ANDERSON, et als.

Petitioners,

VS.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA and CANTON

MUNICIPAL SCHOOL. DISTRICT, et .als., and

MADISON COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, et als.,

Respondents.

ROY LEE HARRIS, et als.,

Petitioners,

VS.

YAZOO COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et

als, YAZ700 CITY MUNICIPAL. SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT, et als., HOLLY BLUFF LINE

CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL. DISTRICT, et als,

Respondents.

JOHN BARNHARDT, et als,

Petitioners,

VS.

MERIDIAN SEPARATE SCHOOL DISTRICT, et als.,

Respondents.

DIAN HUDSON, et als.,

Petitioners,

VS.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA and LEAKE

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, et als.,

Respondents.

JEREMIAH BLACKWELL, JR. et als.

Petitioners,

VS.

ISSAQUENA COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et als.,

Respondents.

CHARLES KILLINGSWORTH, et als.,

Petitioners,

VS.

ENTERPRISE CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL DIS-

TRICT and QUITMAN CONSOLIDATED

SCHOOL DISTRICT,

Respondents.

GEORGE MAGEE, JR.,

Petitioner,

VS.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA and NORTH

PIKE COUNTY CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL

DISTRICT, et als.,

Respondents.

GEORGE WILLIAMS, et als.,

Petitioners,

VS.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA and WILKINSON

COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, el als.

Respondents.

BRIEF IN RESPONSE TO PETITION FOR WRIT OF

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT, INCLUDING

OBJECTIONS TO PETITION WITH MOTION TO AD-

VANCE, AND CROSS-PETITION FOR WRIT OF CER-

TIORARI WITH MOTION TO EXPEDITE HEARING

I

OBJECTION TO MOTION TO ADVANCE AND TO THE

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

In accordance with the provisions of Supreme Court

Rule 24.2 these Respondents object to the Petition for the

Issuance of a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and the Motion to Advance

filed in this cause for the following reasons:

1. These cases are still pending before the Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit upon Petition for Rehearing

En Banc. Supreme Court Rule 20 is as follows:

4

20. Certiorari to a court of appeals before judg-

ment. A writ of certiorari to review a case pending

in a court of appeals, before judgment is given in such

court, will be granted only upon a showing that the

case is of such imperative public importance as to jus-

tify the deviation from normal appellate processes and

to require immediate settlement in this court. See

United States v. Bankers Trust Co., 294 U.S. 240; Rail-

road Retirement Board v. Alton R. Co., 295 U.S. 330;

Rickert Rice Mills v. Fontenot, 297 U.S. 110; Carter v

Carter Cool Co., 203.1U.8,.238: Ex porte Quirin, 317

U.S. 1; United States v. United Mine Workers, 330 U.S.

258; Youngstown Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579.

There is now pending before the Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit a Petition for Rehearing En Banc filed by

all of these respondents and the other defendants in

twenty-five consolidated cases which involve thirty-three

school districts.! Pertinent extracts from the Petition for

1. The consolidated cases are captioned and numbered

in the United States District Court for the Southern District of

Mississippi as United States v. Hinds County School Board, et als.,

No. 4075; Buford A. Lee and United States, et als., v. Milton Evans,

No. 2034; United States v. Kemper County School Board, et als.,

No. 1373; United States (and George Magee, Jr.) v. North Pike

County Consolidated School District, et als., No. 3807; United States

Vv. Natchez Special Municipal Separate School District, et als., No.

No. 1120; United States v. Marion County School District, et als.,

No. 2178; Joan Anderson and United States, et als. v. The Canton

Municipal School District and The Madison County School Dis-

trict, et als., No. 3700; United States v. South Pike County Con-

solidated School District, et als., No. 3984; Beatrice Alexander, et

als. v. Holmes County Board of Education, et als., No. 3779; Roy

Lee Harris, et als. v. The Yazoo County Board of Education, Yazoo

City Municipal Separate School District and Holly Bluff Line Con-

solidated School District, et als., No. 1209; John Barnhardt, et als.

Vv. Meridian Separate School District, et als., No. 1300; United

States v. Neshoba County School District, et als., No. 1396; United

States v. Noxubee County School District, et als., No. 1372; United

States v. Lauderdale County School District, et als., No. 1367; Dian

Hudson and United States, et als. v. Leake County School Board,

et als., No. 3382; United States v. Columbia Municipal Separate

School District, et als., No. 2199; United States v. Amite County

School District, et als., No. 3983; United States v. Covington County

School District, et als., No. 2148; United States v. Lawrence County

School District, et als., No. 2216; Jeremiah Blackwell, Jr., et als.

v. Issaquena County Board of Education, et als., No. 1096; United

States (and George Williams) v. Wilkinson County School Dis-

9)

Rehearing En Banc are attached hereto as Exhibit A and

made a part hereof. A final judgment has not been en-

tered thereon by the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

2. The movants and petitioners have wholly failed to

make “a showing that the case is of such imperative public

importance as to justify the deviation from normal appel-

late processes and to require immediate settlement in this

court”. The recitations of the petition and the matters re-

cited in this response demonstrate that the original Peti-

tion for Writ of Certiorari as filed is attempted to be lim-

ited solely to the timetable set up by the Court of Appeals

in its judgment of July 3, 1969, as amended, which orig-

inally required certain action to be taken on or before Sep-

tember 1. The August 28, 1969 amendment of the judgment

changed the timetable upon motion of the Attorney Gen-

eral of the United States acting in behalf of the United

States and of the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare. The Petition for Writ of Certiorari as filed at-

tempts to exclude consideration of the merits of these

cases. The change in a timetable fixed in these nine cases

here clearly does not come within Rule 20. Sixteen cases

are not affected. The hundreds of other school districts

within the Fifth Circuit are not affected. The thousands

of school districts throughout the United States are not af-

trict, et als., No. 1160; Charles Killingsworth, et als. v. The Enter-

prise Consolidated School District and Quitman Consolidated School

District, No. 1302; United States v. Lincoln County School District,

et als., No. 4294; United States v. Philadelphia Municipal Separate

School District, et als., No. 1368; United States v. Franklin County

School District, et als., No. 4256. The seven cases filed originally

by private plaintiffs are numbered in the Court of Appeals as

Cause No. 28030. The remaining nineteen cases, including the

North Pike and Wilkinson County cases in which private plain-

tiffs were permitted to intervene, are numbered in the Court of

Appeals as Cause No. 28042. None of the defendants and appel-

lees in the suits consolidated in the Court of Appeals under Cause

No. 28042 are respondents to the Petition for Writ of Certiorari

other than the defendants and appellees in the cases of United

States and George Williams v. Wilkinson County School District

and United States and George Magee, Jr. Vv. North Pike County

Consolidated School School District.

6

fected. Even these districts are affected only tempo-

rarily. No finding on the merits is included in the amend-

ment of August 28, 1969. Yet the reasons advanced for the

granting of the writ are based upon evidence alleged to have

been introduced in the District Court contained in the Dis-

trict Court record transmitted to the Court of Appeals upon

the appellate hearing of July 3, 1969.

3. The movants and petitioners have failed to file the

record as required by Supreme Court Rules 12 and 21.

It is required by Rule 21 that the petitioners file:

. . . a transcript of the record in the case, including the

proceedings in the Court whose judgment or decree is

sought to be reviewed, which shall be certified by the

clerk of the appropriate court or courts below. The en-

tire record in the court to which certiorari is addressed

shall be filed unless the parties agree that certified

parts may be omitted as unnecessary for the deter-

mination of the Petition or the Writ, if it is granted.

The pleadings, briefs and other documents filed in

the Court of Appeals and its judgment and orders form

only a small part of the record in that Court. The appellate

record in these cases consists of the original record in the

District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi filed

with the appellate court when the appeals were heard on

July 3, 1969. This included a transcript of the hearings

beginning October 7, 1968, and extending into December,

1968, together with all pleadings filed by the parties and

other matters of record in the District Court in these con-

solidated cases. This transcript, together with the plead-

ings, plans of desegregation, reports, orders and other pro-

ceedings, became part of the record of the Court of Appeals

upon the appeal heard July 3, 1969. The record was there-

after returned to the District Court for use related to the

supplemental proceedings. The transcript of the hearing

of August 21 and August 22, 1969, held by the District Court

7

by direction of the Court of Appeals, as well as the plans

of desegregation filed by HEW and those filed by the

school districts, the objections filed to such plans and addi-

tional reports filed in the District Court are also a part of

the appellate record. All of these records are available to

the petitioners under Rule 11 of the Federal Rules of Appel-

late Procedure:

If the record or any part thereof is required in the

district court for use there pending the appeal, the dis-

trict court may make an order to that effect, and the

clerk of the district court shall retain the record or

parts thereof subject to the request of the court of ap-

peals, and shall transmit a copy of the order and of the

docket entries together with such parts of the original

record as the district court shall allow and copies of

such parts as the parties may designate.

The movants and petitioners have made no motion in

the Court of Appeals for an order that the original record

in the District Court be transmitted to the Court of Ap-

peals and by it to this Court. Hence, the said motion and

petition are not sustainable under the rules of this Court.

4. The movants and petitioners have failed to repro-

duce and make available to the Court copies of necessary

pertinent portions of the original record in these cases. The

only “appendices” attached to the Motion and Petition

consist of opinions, orders and directives of the United

States Court of Appeals and the United States District

Court, together with copies of two letters. The appendix

does not even include a copy of the Motion filed by the De-

partment of Justice in its own behalf and in behalf of the

Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare. The amend-

ment complained of was granted upon this motion.

The letter dated August 19 appearing on pages 53a and

54a of the appendix was an exhibit to such motion. The

only other portion of the record reproduced and attached

8

by the movants and petitioners is a letter dated August 11,

1969, appearing on pages 40a through 50a of petitioners’ ap-

pendix. This is one of the thirty exhibits (Tr. page 244)

introduced at the hearing held by the United States Dis-

trict Court on August 21 and August 22 (at the request

and direction of the Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit).

This letter was introduced at page 123 of the transcript.

Such transcript has not been filed with the Petition for

Writ of Certiorari. However, these respondents and

cross-petitioners have filed with the Clerk of this Court

under Rule 21.4 a certified copy of the transcript taken on

August 21 and August 22, 1969, upon the hearing of the mo-

tion by the Attorney General of the United States. Perti-

nent extracts therefrom are attached hereto as Exhibit B

for the information of the Court.

11.

RESPONSE TO PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

1. Preliminary Statement

We are amazed at the lack of knowledge of the evi-

dence displayed in the Petition for Writ of Certiorari here-

in filed. The writer of this brief has participated in judi-

cial proceedings in state and federal courts in many states

over a period of forty years and has never observed recita-

tions in any petition which were such a complete departure

from the facts appearing in the record.

2. Question Stated by Movants and Petitioners

In the Petition for Writ of Certiorari the petitioners

state the “Questions Presented” as follows (numbers in-

serted by us for convenient reference):

Did the Court of Appeals err in (1) granting fourteen

Mississippi school districts (2) an indefinite delay

(3) in implementing school desegregation plans (4)

Rn». cs = ses

9

based upon generalized representations by the United

States Department of Health, Education and Welfare

that delay was necessary (5) for preparation of the

communities?

Each phrase underlined by us is a clear misconstruc-

tion of the evidence and proceedings contained in this rec-

ord. We call the Court’s attention to the following phrases:

(1) “Granting fourteen Mississippi school districts”.

To the contrary the motion was made by the Department

of Justice in behalf of the United States and of the Secre-

tary of Health, Education and Welfare, a copy of such mo-

tion being attached hereto as Exhibit C. Additional time

was granted to the Office of Education of the Department

of Health, Education and Welfare (acting in conjunction

with the school districts) to “develop and present to the

District Court on or before December 1, 1969, acceptable

plans of desegregation”. This was done upon motion filed

by the Attorney General in behalf of the United States and

as attorney for the Secretary of Health, Education and Wel-

fare. The new timetable was not initiated by any of the

defendants. It was stipulated of record by the attorneys

for the private plaintiffs as follows (Exhibit B hereto, pp.

21e-22e):

BY MR. SATTERFIELD: May I further inquire

of counsel for the individual Plaintiffs, by the filing

of this objection as entitled, as I understand, it is in-

tended at least to be applicable to all cases in which

they are individual plaintiffs. Does counsel file this

objection recognizing that the motion made by the De-

partment of Justice on behalf of the Secretary and of

the United States, does apply to those seven cases

with a possibility of the addition of two more?

BY MR. AMAKER: Well, we recognize that, yes.

As stated in Note 1 of the Petition, the private plain-

tiffs filed seven suits and were permitted, at the August

21, 1969, hearing, to intervene in two additional cases.

10

The Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare was

directed by the Court to file on August 11, 1969, plans of

desegregation in all of the twenty-five consolidated cases.

The Secretary did file original plans in each case. See

testimony of Mr. Jordan, pertinent portions of which are

included in Exhibit B hereto. The school districts also

filed differing plans on August 11, 1969. Agreement not

having been reached largely due to press of time, the school

districts also filed objection to the HEW plans on August

21, 1969.

It being impossible to resolve the differences before

the timetable deadline of September 1, 1969, either by ne-

gotiation or by hearings affecting the thirty-three districts,

the Attorney General of the United States filed his mo-

tion. The school boards simply joined in the motion made

in behalf of the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare.

A copy of such joinder is attached hereto as Exhibit D. It

was stipulated by individual plaintiffs that the motion filed

by the Attorney General of the United States was appli-

cable to these nine cases.

(2) “An indefinite delay”. There was nothing in-

definite about the delay granted. The change in the time-

table requested by the Secretary of Health, Education and

Welfare was granted to permit it (in conjunction with the

school districts) to develop and present to the District Court

on or before December 1, 1969, acceptable plans of desegre-

gation. The next step required was approval by the Dis-

trict Court unless objections were filed within fifteen days.

The District Court was then required to hold a hearing

within fifteen days after objections were filed to enter

findings of fact and conclusions of law in each case. In

addition, October 1, 1969, was set as the limit for the filing

of a program developed by the Office of Education and the

boards “to prepare its faculty and staff for conversion from

1

the dual to the unitary system”. In general, this schedule

has been met and programs have been filed approved by

both HEW and the several school districts. The schedule

also included the following requirement (Petition page

78a):

It is a condition of this extension of time that the

plan as submitted and the plan as finally approved

shall require significant action toward disestablish-

ment of the dual school systems during the school year

September 1969-June 1970.

(3) “Based upon generalized representations by the

United States Department of Health, Education and Wel-

fare”. We have filed with the Clerk of this Court under

Supreme Court Rule 21.4 a transcript of the entire testi-

mony taken August 21 and 22, 1969, at the hearing held at

the direction of the Court of Appeals. The testimony of

Mr. Jordan, head of the Atlanta Regional Office of the

Department of Education, was particularly specific and de-

tailed as hereinafter discussed. It pointed out the reasons

why it had not been possible for HEW to develop full, com-

plete and satisfactory plans nor to prepare for the imple-

mentation thereof.

(4) “That delay was necessary for preparation of the

communities”. This is contrary to the facts. This time was

granted for the reasons advanced by Mr. Finch, Secretary

of Health, Education and Welfare, in his letter to Honor-

able John Brown, Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals of

the Fifth Circuit. Such letter (Petitioners’ Appendix, pp.

53a and 54a) was attached as an exhibit to the Motion by

the Attorney General of the United States and made a part

thereof by reference (Exhibit C hereto). Mr. Finch’s state-

ments thus became allegations of the motion upon which

the Court of Appeals based its action:

On Thursday of last week, I received the terminal

plans as developed and filed by the experts from the

12

Office of Education. I have personally reviewed each

of these plans. This review was conducted in my ca-

pacity as Secretary of the Department of Health, Ed-

ucation and Welfare and as the Cabinet officer of our

government charged with the ultimate responsibility

for the education of the people of our Nation.

In this same capacity, and bearing in mind the

great trust reposed in me, together with the ultimate

responsibility for the education of the people of our

Nation, I am gravely concerned that the time allowed

for the development of these terminal plans has been

much too short for the educators of the Office of Ed-

ucation to develop terminal plans which can be imple-

mented this year. The administrative and logistical

difficulties which must be encountered and met in the

terribly short space of time remaining must surely in

my judgment, produce chaos, confusion and a catas-

trophic educational setback to the 135,700 children,

black and white alike, who must look to the 222 schools

of these 33 Mississippi districts for their only available

educational opportunity.

I request the Court to consider with me the short-

ness of time involved and the administrative difficul-

ties which lie ahead and permit additional time during

which experts of the Office of Education may go into

each district and develop meaningful studies in depth

and recommend terminal plans to be submitted to the

Court not later than December 1, 1969.

The motion was not for the purpose of preparing com-

munities for acceptance of plans. It was to allow time for

the development of terminal plans based upon meaningful

studies in depth. It was to give the Secretary of Health,

Education and Welfare sufficient time, after proper studies

and in collaboration with the school districts, to recom-

mend terminal plans to be submitted to the Court not later

than December 1, 1969. The “preparation of the commu-

nities” is only incidental to the implementation of sound

and proper plans.

i mmm oS —

13

Honorable John Leonard, Assistant Attorney General

of the United States, Civil Rights Division, stated the posi-

tion of the United States and the Secretary of Health,

Education and Welfare as follows (Exhibit B hereto, pp.

22e-23e):

I think it is also safe to say that most of the school

boards did cooperate in that at least information was

provided and the educators were received by the col-

leagues in the district and were able to draw and pull

together the information necessary to provide some

kind of a plan.

I think, however, that it became obvious to the Sec-

retary of Health, Education and Welfare that as the

time pressure was building here both with respect to the

field work that needed to be done, the investigation by

his people, out in the field, in the districts, that it soon

became apparent to him that in order to have, in fact,

an orderly movement from a dual to a unitary system,

in order to accomplish in fact what we believe the Su-

preme Court seeks, that is a plan that works, one that

is going to accomplish the objectives, both with re-

spect to the development of the plans and with respect

to the implementation of those plans, that the time

was simply too short.

Now, I would be less than candid if I didn’t say

that the Government was somewhat embarrassed by

this because we gave the Fifth Circuit some assurance

that there was time but we are lawyers, not educators,

and it is the educational judgment it seems to me, that’s

important here. These are the men who are trained

to educate our children. They are the ones that have

to make the administrative and the educational deci-

sions that go with bringing about not just a unitary

system but a plan for education in the framework of

elimination of racial discrimination that’s going to,

in fact, result in quality education.

Mr. Jesse J. Jordan, Senior Program Officer of the

United States Office of Education, Atlanta, Georgia (who

14

was in charge of development of all the plans of desegre-

gation for HEW for the thirty-three districts included in

the twenty-five consolidated cases), testified (Exhibit B

hereto, p. 30e):

Q. Back to the plans Mr. Jordan, with respect to

the time frame in which they were developed. Do

you have an opinion as to whether or not that time

frame had any effect on the validity of the plans

themselves?

A. 1 think probably the plans themselves were

sound; however, my personal belief in developing

plans of this nature, it is necessary to do a number of

curriculum studies which time did not allow for. Cur-

ricular was not examined at all, finance, no financial

studies were made, no social or economic study was

made to determine the needs of any given district, and

if these studies were made, you probably will come up

with a superior plan than just a purely segregated plan.

You would come up with a plan for educational change

for which the desegregated is a part. . . .

3. Question Actually Presented by Motion and Petition

Shall this Court reverse the finding of fact and law

by the Court of Appeals affirming the findings of the Dis-

trict Court that the Secretary of Health, Education and Wel-

fare, the United States and the local school boards required

and should be granted sufficient time to develop reasonable

and satisfactory plans of desegregation within a definite

time schedule?

The nine captioned cases are pending in the United

States District Court for the Southern District of Missis-

sippi. All were included in the twenty-five cases consoli-

dated in the District Court for the original hearing and

later consolidated upon appeal by the Court of Appeals of

the Fifth Circuit under Docket Nos. 28030 and 28042. These

cases generally are referred to as U.S.A. v. Hinds County

15

Board et als. Originally, the captioned cases were con-

solidated with thirty-five other cases from various district

courts and heard by the Court of Appeals upon motion to

set aside District Court docket entries. They were cap-

tioned Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181 (5th Cir. 1968).

All twenty-five of the consolidated cases were included

in the judgment and opinion of the Court of Appeals dated

July 3, 1969 (Petitioners’ Appendix B, p. 28a), as amended

by order dated July 25, 1969 (Petitioners’ Appendix B, p.

38a), the Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law by the

District Court dated August 26, 1969 (Petitioners’ Appen-

dix D, p. 56a), and also order adopted by the Court of Ap-

peals of the Fifth Circuit on August 28, 1969, amending the

judgment of July 3, 1969 (Petitioners’ Appendix D, p. 71a).

The judgment and mandate of the Court of Appeals

dated July 3, as amended on July 25, reversed the action of

the District Court which had found that the plans adopted

by each school board under Jefferson-type decrees were

operating in conformity with the teachings of Green,

Monroe and Raney. The judgment and mandate did not

approve any plan but set up a time schedule ending Sep-

tember 1, 1969, for formulation, submission and approval of

such plans. The mandate required a hearing on such plans

by the District Court and the adoption of a plan conform-

ing to Constitutional standards, all to be accomplished on

or before September 1, 1969.

As set out in the “Findings of Fact and Conclusions of

Law by the District Court” (Petitioners’ Appendix D, p.

56a), the Attorney General on behalf of the United States

and the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, in-

troduced evidence demonstrating that it was impossible for

the original schedule to be met. The Findings of Fact by

the District Court were affirmed by the Court of Appeals.

16

4. The Divergent Plans of Desegregation Filed by HEW

and the School Districts Have Not Been Considered

or Approved by Either the District Court or the

Court of Appeals

No new plan of desegregation for any one of the dis-

tricts involved in the twenty-five consolidated cases has

been considered by either the District Court or the Court

of Appeals. The Secretary of Health, Education and Wel-

fare filed in the Court of Appeals a formal motion (Ex-

hibit C hereto, p. 35e) with his letter attached (sup-

ported by the evidence in this proceeding). He requested

time to develop and present to the District Court on or be-

fore December 1, 1969, acceptable plans of desegregation.

The defendant districts filed proposed plans on or about

August 11, 1969, reserving all of their rights under the pend-

ing Motion for Rehearing En Banc, their rights to file Peti-

tion for Writ of Certiorari, and other procedural rights.

They alleged in their joinder in the motion of the Attor-

ney General that it was “impossible to work out a plan

satisfactory to either the Court, the defendants or the plain-

tiff” in the time allowed (Exhibit D hereto, p. 43e).

No hearing has been had by either the District Court

or the Court of Appeals upon the merits of any plan of

desegregation. Hence, if the Motion and Petition are

granted, the new plans to be filed by the Secretary of

Health, Education and Welfare after full and complete in-

vestigation, study in depth, and consultation with the school

districts, will not be before the Court; the original plans

filed by the Secretary have not been considered by either

the District Court or the Court of Appeals. The plans filed

by the school districts have not been considered by the

District Court or the Court of Appeals. There is nothing

to be put into effect in these school districts under the teach-

ings of Brown, Green, Monroe and Raney.

17

If the Motion and Petition are granted, it would sim-

ply reinstate an impossible time schedule, deny the Secre-

tary of Health, Education and Welfare and the Department

of Justice an opportunity to carry out the procedures out-

lined in the motion and evidence presented by them and

deny the school districts both a hearing by the District

Court and the opportunity to collaborate with HEW in de-

veloping terminal plans.

5. Statement of Facts

A. The Court of Appeals proceeded in these cases

with all possible dispatch. All districts have been operat-

ing under model Jefferson decrees and were in compliance

with such decrees. After the decision in Green, plaintiffs

filed motions in the District Court for supplemental re-

lief, seeking the formulation and implementation of de-

segregation plans other than freedom-of-choice. The Dis-

trict Court found that these school districts were in com-

pliance with Green and denied these motions by order

entered on or about May 16, 1969 (Appendix D to Petition,

pp. la-22a). After notices of appeal and preliminary

steps the following transpired:

(1) On June 23, 1969, the United States of America

filed Motion for Summary Reversal and Motion

to Consolidate Appeals.

(2) On June 23, 1969, the Clerk of the Court of Appeals

mailed a letter stating the motion of the United

States of America would be presented on July

3, together with any response filed prior to that

date by opposing counsel.

(3) On June 25, 1969, the Court of Appeals issued a

directive to counsel of record (Appendix B to

Petition, p. 24a) that the Court would hear

oral argument on these cases “on motion for sum-

mary reversal and the merits in all of the cases”.

(4)

18

(All emphasis in this response is ours unless

otherwise indicated.) This directed that the argu-

ment would be held in New Orleans beginning at

9:30 A.M. July 2, 1969, and any memoranda or

responses must be filed with the Clerk by noon,

July 1, 1969. The letter further recited the Court

had taken notice of the District Court’s order with

respect to the record; but, since appeal was being

expedited on the original record, the United States

Attorney should make arrangements with the Dis-

trict Clerk to transmit to the Clerk of the Court

of Appeals the entire record of the District Court

so that the same would be available to the Court

if needed during the argument and summation.

It was further stated that the Court recognized

that “this is a huge record involving a large num-

ber of parties and matters of great public interest

and importance”. This letter was received by

counsel on June 25 and June 26.

The directive of the Court of Appeals contained

the following finding by the Court (Appendix B

to the Petition, p. 26a):

6. The Court’s general approach will be to

accept the fact findings of the District Court

and to determine what, if any, legal relief is

now required based thereon. To the extent that

appellants, private or government, assert that

any one or more specific fact findings (as dis-

tinguished from mixed questions of law and

fact) are clearly erroneous, the appellants con-

cerned shall xerox copies of pertinent excerpts

of the transcript of the evidence for use by

the Judges (4 copies) which may be made

available during argument.

No party filed xerox copies of pertinent excerpts

from the record asserting that any findings of fact

of the District Court were erroneous.

19

(5) On July 2, 1969, oral argument was presented and

was concluded before the Court adjourned for

lunch.

(6) On July 3, 1969, the judgment of the Court of Ap-

peals was entered. It was amended, ex mero

motu, July 25, 1969.

B. The schedule provided in the Appeals Court Order

of July 3 (as amended July 25)required immediate ac-

tion, without time for study by HEW or collaboration

with the school districts.

The Appeals Court Order of July 3 (later amended

on July 25) provided (Appendix B to Petition, pp. 28a

and 38a):

(1) The District Court should forthwith request that

educators from HEW collaborate with the defend-

ant school boards in the preparation of plans to

disestablish the dual school systems in question

(the District Court so ordered on July 5, 1969).

(2) Each board and HEW should present to the Dis-

trict Court before August 11 an acceptable plan of

desegregation for each district.

(3) If an agreed plan was submitted by a board and

HEW on August 11, the plan would be approved

unless within seven days a party filed objections

grounded on Constitutional standards.

(4) If no agreement was reached, HEW should file

its plan by August 11 and the parties would have

ten days within which to file objections or sug-

gested amendments. The District Court would

hold a hearing and enter a plan by August 31 which

conformed to Constitutional standards.

|

|

20

(5) A plan for each school district was required to be

entered not later than September 1, 1969, to be

effective for the beginning of the 1969-70 school

year.

On July 15, pursuant to this expedited plan of action,

educators employed by HEW met at Mobile, Alabama, to

plan their collaboration with the thirty-three districts em-

braced in the orders of the Court of Appeals and the Dis-

trict Court (Exhibit B, pp. 27e-28e).

C. The timetable fixed by the Court of Appeals

(upon recommendation of the Department of Justice)

when placed in operation was found by HEW to be im-

possible of effective execution.

Jessie J. Jordan is an experienced educator who be-

lieves a unitary school system is superior to a dual school

system. He is Senior Program Officer for Title Four in

the United States Office of Education in the Atlanta region

and coordinated the overall effort of planning for the thirty-

three Mississippi school districts and reviewed all of the

plans. (Exhibit B hereto, pp. 25e-26e).

Between July 16 and July 23 these teams made their

first trip into Mississippi. Mr. Jordan testified that on

this first trip “. . . the teams gathered statistical informa-

tion on enrollment, certain building information, pupil lo-

cation maps where available, school location maps, visita-

tion of schools and tried to get a general feeling and input

from the school system.” (Exhibit B, p. 28e).

On July 23, all teams returned to Atlanta and worked

on “. .. trying to put together some tentative recommenda-

tion for the school system.” (Exhibit B, p. 28e).

Between July 29 and extending through August 1,

the teams made a second trip into Mississippi. Mr. Jordan

21

said: “On this trip the teams met with the school systems

the second time to present some of their recommendations

and to try to get input from the school systems.” (Ex-

hibit B, p. 28e).

From August 2 through August 6, all teams were in

Atlanta formalizing the plans upon which they were work-

ing. Mr. Jordan testified:

After they had been formalized, duplicated and so

forth, a third trip was made into Mississippi from

the 7th through the 9th at which time the plans were

formally presented to the superintendent or the board

or whoever the superintendent wished present.

On August 11 such HEW plans were filed with the

Court. Mr. Jordan further testified:

The teams were working on a very tight schedule

and each team had to, depending on the size of the

school system, had from two to six districts to cover

which meant, I believe, I'm not absolutely positive

of this, but I would say that the average time in a

school district on the first visit was a day and a half.

The average on the second visit, maybe a half a day.

Because of the lack of time to confer and collaborate,

none of the thirty-three defendant districts reached an

agreement with HEW.,

On August 11 each defendant district also filed a

separate plan with the District Court.

Prior to August 19, Mr. Jordan reported voluntarily

and on his own initiative by telephone to his superior,

Dr. Anrig, that in his expert judgment more time was re-

quired for development and implementation of plans for

desegregation in the subject school districts.

22

On or before August 21, the districts filed objections

to the plans of HEW and attached affidavits containing

testimony supporting their own plans and criticizing the

plans of HEW. No objections to the school district plans

were thus filed by the plaintiff or invervenors.

On August 26, after the hearings held August 21

and 22, the District Court filed its Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law and recommended that the Court

of Appeals grant the relief sought by the United States

of America (Appendix to the Petition, p. 56a).

On August 28 the Court of Appeals affirmed the

Finding of Fact and Conclusions of Law of the District

Court, after considering the record of the August 21st

hearing and in light of the full record in these cases. It

sustained the motion of the United States of America and

amended its previous judgment as herein above set forth

(Petitioners’ Appendix, p. 71a).

In addition to Findings of Fact based upon the testi-

mony of Mr. Jordan, the District Court found as follows

upon the testimony of Mr. Howard O. Sullins, another

witness for the United States and Program Officer for the

United States Office of Education in Atlanta (Petitioners’

Appendix D, pages 67a-68a):

The witness was of the opinion and the Court finds,

‘that in order to formulate and implement successful

and effective desegregation plans, the additional time

requested will be required. This witness suggested ad-

ditional programs which should be undertaken to ef-

fect a smooth, workable conversion to a completely

unitary school system, such as a workshop for teachers

and pupils to discuss potential problems of desegre-

gation and their solution, as was done in other dis-

tricts in which this witness worked, including some

in South Carolina. These committees of students

and teachers must meet with experts to obtain more

nae ET _s

23

knowledge on how to solve problems that will arise.

The witness stated that all defendant school districts

with which he dealt cooperated fully with his team

but that his team was mot authorized to negotiate

any differences with the school boards. The first time

that the defendant school districts saw the HEW plan

in written form was on August 7, 1969, at which time

there could be no more collaboration from HEW'’s

standpoint, that is, there could be no further change

in the HEW plan which was filed subsequently in

this Court in all these school district cases.

Even if the motion of the Government for addi-

tional time had not been filed in this case with all

due deference, it is extremely doubtful if this Court

could have physically complied with the mandate of

the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir-

cuit, because of the devastating effect of super Hurri-

cane Camille, which this Court does not have to take

judicial notice of, because it has personal and actual

knowledge thereof. This deadly, gigantic ‘“hurricane-

tornado” struck not only the Mississippi Gulf Coast

where the undersigned Judges reside, but also caused

great damages to many other parts of the State of

Mississippi, including many of the areas in which the

defendant school districts are located.

We embody in this Response by reference the detailed

refutation of erroneous and unfounded statements in the

original Petition which we set forth in the Cross-Petition

for Writ of Certiorari.

6. The Order Entered by the Court of Appeals on

August 28th Is Based upon a Finding of Fact, Sup-

ported by the Record, Made by Both the District

Court and Court of Appeals, and Should Not Be

Disturbed

As set out above, the amendment of August 28 permits

the consideration by the District Court of new plans de-

veloped by HEW and the school districts during the period

24

from August 31 to December 31st. At the same time, the

Court required: (1) a program of faculty orientation for

conversion from a dual to a unitary system to be adopted

by October 1; (2) further study for better plans and more

efficient implementation; (3) additional joint study by

HEW and local boards looking toward improvement of and

agreed plans of desegregation; and (4) a condition that

plans submitted and approved call for significant actions

to disestablish the dual school system during the Septem-

ber 1969-June 1970 school year.

Upon the evidence, including the testimony of experts

presented by the United States, the District Court found

(Petitioners’ Appendix, p. 69a):

In view of all of the above, this Court finds and con-

cludes that it has jurisdiction to consider this motion

and make findings of fact thereon and suggestions and

recommendations to the appropriate panel of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in

these cases. This Court is further of the opinion and

finds, as a matter of fact and of law, that the motion

filed by the Government, joined in by the defendant

school districts, is meritorious and should be granted

for the foregoing reasons and for the further reasons

that the granting of the requests made by the Govern-

ment will, in truth and in fact, probably result in a

smooth, workable conversion of the defendant school

districts from a dual to a unitary system, with the elim-

ination of the many problems of chaos and confusion

referred to by the Secretary of HEW in his letter.

It is therefore the recommendation of this Court that

the appropriate panel of the Court of Appeals grant

the amended motion filed by the Government in all of

these cases, and then adopt and enter the proposed

“New Amended Order” as revised in this hearing,

which was filed by the United States and attached to

its Amended Motion filed here and in the Court of Ap-

peals.

25

The Court of Appeals reached a similar factual con-

clusion as follows (Petitioners’ Appendix, p. 76a):

Following this the Court has received and considered

the findings of fact, conclusions of law and recom-

mendations of the District Court, the record of the

hearings, and the briefs and arguments of counsel, pro

and con. On the basis of the matter set forth herein,

the Court amends its order further as follows: [Here

follows the amendment of August 28.]

The present petition seeks to vacate the August 28th

amendment of the judgment, even though the District

Court and the Court of Appeals have found as a fact that

action upon the time schedule previously fixed would

produce chaos, confusion and a catastrophic educational

setback to the 135,700 children, black and white alike, who

must look to the 222 schools of these 33 Mississippi districts

for their only available educational opportunity. We re-

spectfully submit that this is not required by Brown v.

Board of Education, 1055, 349 11.8. 204, 75 S.Ct. 753, 99

L.Ed. 1083, by Green v. County School Board, 1968, 391

U.S. 430.

The Supreme Court has consistently declined to take

such action. The Linseed King, 1932, 52 S.Ct. 450, 285 U.S.

502, 76 L.Bd. 903; J. 1. Case Co. v. Borak, 1964, 84 S.Ct.

1554, 377 U.S. 426, 12 L.Ed. 423; Great Atlantic & Pacific

Tea Co. v. Supermarket Equipment Corp., 1950, 71 S.Ct.

127, 340 U.S. 147, 95 L.Ed. 162; Berenyi v. District Director,

1967, 87 S.Ct. 666, 335 U.S. 630, 17 L.Ed. 656. In Meredith

v. Fair, supra, Mr. Justice Black said:

I further agree with the Court of Appeals that there

is very little likelihood that this Court will grant

certiorari to review the judgment of the Court of

Appeals, which essentially involves only factual is-

sues. (9 L.Ed.2d, p. 44).

26

The Supreme Court is reluctant to interfere with fac-

tual decisions of the lower Courts. United States Alkali

Export Ass’n v. United States, 1945, 325 U.S. 196, 89 L.Ed.

1554. In Cumberland Telephone & Telegraph Co. v. Loui-

siana Public Service Commission, 1922, 67 L.Ed. 217, the

Supreme Court said:

But the court which is best and most conveniently

able to exercise the nice discretion needed to deter-

mine this balance of convenience is the one which has

considered the case on its merits, and therefore, is

familiar with the record. (67 L.Ed., p. 224).

The action desired, if the present petition is granted,

is easily distinguishable from that in Lucy v. Adams, supra,

wherein the Supreme Court was asked to implement the

findings of fact of the District Court (134 F.Supp. 235).

In so doing the Supreme Court was not called upon to

reverse or set aside the findings of fact of the lower Court,

as would be the case if the present motion were granted.

To the contrary, this matter falls within the teaching

of Brown v. Board of Education, supra, Cooper v. Aaron,

1958, 358 U.S. 1, and Green v. County School Board, supra,

that the District Courts can best perform the necessary

judicial appraisal for the implementation of desegregation

of schools.

7. Vacating the Amendment of August 28th Will Ac-

complish No Appreciable Expedition of Action in

These School Suits and Would Be Detrimental to

the Interest of All Students

If the mandate which was in effect prior to August

28th were to be reinstated at this time, the original time-

table would have to be revised to permit the District

Court to carry out its function. All that could be gained

from reinstating such mandate would be a hurried entry

at some future date of partially completed and admittedly

27

inadequate plans, which future date might approach closely

the December 1st to December 31st dates set in the amend-

ment of August 28th. However, such order specifically

requires ‘significant action toward disestablishment of

the dual school system during the school year September,

1969-June, 1970.”

The effect of reinstating the earlier order of the

Court of Appeals would be to direct the District Court to

hold hearings for each district and to enter new plans for

desegregation (under whatever new timetable the Court

of Appeals would deem appropriate). The only plans

before the District Court are those submitted by HEW

and those submitted by the school districts. The District

Court is now confronted with the opinion of Secretary

Finch that the plans HEW prepared should not be entered

or implemented at this time, as the Secretary stated:

I am gravely concerned that the time allowed for the

development of these terminal plans has been much

too short for the educators of the Office of Education

to develop terminal plans which can be implemented

this year. The administrative and logistical difficul-

ties which must be encountered and met in the ter-

ribly short space of time remaining must surely in

my judgment, produce chaos, confusion, and a cata-

strophic educational setback to the 135,700 children,

black and white alike, who must look to the 222

schools of these 33 Mississippi districts for their only

available educational opportunity.

8. The Petition for Writ of Certiorari Being Directed

to the Amendment of a Judgment, the Same Should

Be Dismissed or, in the Alternative, Granted As

Being Applicable to the Entire Judgment

Under the statutes and the rules of this Court, a Writ

of Certiorari will not lie to review the amendment of a

judgment entered by a Court of Appeals. The statutes

28

were adopted and the rules were promulgated to permit

the review of any judgment of a Court of Appeals. A

piecemeal review of one or more amendments to a judg-

ment cannot be sustained. Hence, this Petition for Writ of

Certiorari should either be dismissed, or, in the alterna-

tive, should be construed to be a petition to bring before

this Court the entire judgment entered on July 3, 1969,

including the amendments of July 25, 1969 and August 28,

1969, together with all matters therein involved.

As will be set forth in the Cross-Petition for Writ of

Certiorari herein filed, if such review is granted these re-

spondents and cross-petitioners will move for an expedited

hearing consistent with the full record being filed with

this Court, sufficient time being allowed for preparation

of appropriate appendices, and for full, complete and

proper briefs by all parties.

For the foregoing reasons the respondents respect-

fully submit that their objections to the Petition for Writ

of Certiorari herein filed and the Motion to Advance the

same should be sustained and both such Petition and Mo-

tion should be denied.

FE

CROSS-PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

And now having fully responded to and answered the

Petition for Writ of Certiorari herein filed and the Motion

to Advance the same, all of the respondents named in the

caption hereto (other than the United States of America)

file this, their Cross-Petition for Writ of Certiorari under

Rule 21 of the Rules of this Court against the Petitioners

and the United States of America, subject to the reserva-

tion of rights hereinafter set forth. Cross-Petitioners adopt

all of the allegations above set forth in their Response and

make such allegations a part hereof by reference.

29

Cross-Petitioners pray that a Writ of Certiorari issue

to review the judgment of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit entered on July 3, 1969, as

modified by order dated July 25, 1969, and by order dated

August 28, 1969. Said judgment of the Court of Appeals

of the Fifth Circuit is the same judgment which is the

subject of the Petition for Writ of Certiorari filed by the

Petitioners.

1. Judgment and Opinion Below

The original judgment with the opinion appended

thereto was rendered on July 3, 1969 (Petitioners’ Ap-

pendix B, page 28a). Said judgment has been amended by

order entered by the said court on July 25, 1969 and later

amended by order entered by the said court on August 28,

1969. Neither of said orders has been reported. As copies

of the said judgment and the said amendments are at-

tached to the Petition for Writ of Certiorari herein filed,

the same are embodied herein by reference and copies are

not attached to this Cross-Petition for Writ of Certiorari,

under the provisions of Supreme Court Rule 21.

2. Jurisdiction

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit was dated and entered on July 3,

1969. Opinion and mandate were issued on that date.

Such judgment was amended by order entered July 25,

1969 and by order entered August 28, 1969. Petition for

Rehearing En Banc was filed in the said Court of Appeals

in accordance with and within the time limited by the

Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, having been filed

on July 16, 1969.

Petition for Rehearing En Banc is still pending and

undisposed of by the said Court of Appeals. A copy of

30

said Petition for Rehearing En Banc is a part of this

record in the Supreme Court and pertinent extracts there-

from have been attached as Exhibit A to the above Re-

sponse filed herein by these Cross-Petitioners. Said Pe-

tition for Rehearing is made a part hereof by reference.

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to the

provisions of Title 28 U.S.C. § 1254 (1).

3. Reservation of Rights

The Cross-Petitioners reserve their objections filed

to the original Petition for Writ of Certiorari and to the

Motion to Advance the same. This Cross-Petition for Writ

of Certiorari is filed to protect the rights of Cross-Peti-

tioners and to assure that if a Writ of Certiorari is issued

it will bring the entire matter before this Court as dis-

tinguished from one amendment to one portion of the

judgment of the Court of Appeals. It is also filed taking

cognizance of the fact that the Petition for Rehearing En

Banc is under consideration by the Court of Appeals of

the Fifth Circuit and that should such Petition be over-

ruled during the pendency of this proceeding, Rule 20

would become inapplicable as of that date. The Cross-

Petitioners further reserve their objection to the original

Petition for Writ of Certiorari on the ground that it at-

tempts to obtain a review of an amendment to a judgment

and not of the entire judgment. It can only be sustained

if construed to be a Petition for Writ of Certiorari to re-

view the judgment of July 3, 1969, as amended on July

25, 1969 and August 28, 1969.

4. Questions Presented for Review

(1) Is a freedom of choice plan a proper vehicle to

set up and maintain schools conforming to all Constitu-

tional guarantees, where such plan is properly formulated

31

complying with all requirements laid down by the courts,

administered fairly and without discrimination, and which

permits truly free and uninfluenced choice by students and

their parents? If so, what are the vestiges of a dual sys-

tem which must be eradicated in order to maintain a

freedom of choice plan?

(2) Do the decisions of the Court of Appeals of the

Fifth Circuit construing, implementing and broadening

Jefferson I and Jefferson II, or any other decisions thereof

applying Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

administration of public schools, conflict with the decisions

of other Courts of Appeal on the same question?

(3) Does Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment

require enforced integration of the public schools as dis-

tinguished from prohibiting enforced segregation thereof

to the extent that any plan is unconstitutional under which

there are schools composed of students of only the Negro

race, or only a small fraction of Negroes are enrolled in

formerly white schools, or there are schools with faculties

composed chiefly of teachers of one race?

(4) Has the Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit in

Hinds County and other cases announced by various panels

applied Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

administration of public schools so that it has decided a

Federal question in a way which conflicts with applicable

decisions of this Court, or so as to determine important

questions of Federal law which have not been, but should

be, settled by this Court?

(5) Have the Cross-Petitioners been accorded due

process of law or did the Court of Appeals of the Fifth

Circuit err in reversing and remanding the consolidated

cases in Hinds County without an opportunity for the

32

record to be considered, for full briefs to be filed, and

for the Court to consider the differing local situations and

differing attainments in the districts involved?

5. Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved

The following are the Constitutional provisions and

statutes involved with citation of the volume and page

where they may be found in the official edition:

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States,

Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the

United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof,

are citizens of the United States and of the State

wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce

any law which shall abridge the privileges or immu-

nities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any

State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property,

without due process of law; nor deny to any person

within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Section 5. The Congress shall have power to enforce,

by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this

article.

CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964, SUBCHAPTER 1V.

PUBLIC EDUCATION

Section 401 (b) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, being

Pub.L. 88-352, Title IV, § 401, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat. 246,

and appearing as Title 42, Section 2000c-(b), U.S.C.A.:

“Desegregation” means the assignment of students to

public schools and within such schools without regard

to their race, color, religion, or national origin, but

“desegregation” shall not mean the assignment of stu-

dents to public schools in order to overcome racial im-

balance.

33

Section 410 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, being Pub.

L. 88-352, Title IV, § 410, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat. 249, and

appearing as Title 42, Section 2000c-9, U.S.C.A.:

Nothing in this subchapter shall prohibit classification

and assignment for reasons other than race, color, re-

ligion, or national origin.

Section 407 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, being Pub.

L. 88-352, Title IV, § 408, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat. 249, appear-

ing as Title 42, Section 2000c-6 (a), U.S.C.A.:

. . . provided that nothing herein shall empower any

official or court of the United States to issue any order

seeking to achieve a racial balance in any school by

requiring the transportation of pupils or students from

one school to another or one school district to another

in order to achieve such racial balance or otherwise

enlarge the existing power of the court to insure com-

pliance with constitutional standards.

CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964, SUBCHAPTER V.

FEDERALLY ASSISTED PROGRAMS

Section 604 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, being Pub.L.

88-352, Title VI, § 604, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat. 253, and ap-

pearing as Title 42, § 2000d-3, U.S.C.A.:

Nothing contained in this subchapter shall be con-

strued to authorize action under this subchapter by

any department or agency with respect to any employ-

ment practice of any employer, employment agency, or

labor organization except where a primary objective

of the Federal financial assistance is to provide em-

ployment.

CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964, SUBCHAPTER VI.

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITIES

Section 702 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, being

Pub.L. 88-352, Title VII, § 702, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat. 255,

and appearing as Title 42, Section 2000e-1, U.S.C.A.:

34

This subchapter shall not apply to an employer with

respect to the employment of aliens outside any State,

or to a religious corporation, association, or society

with respect to the employment of individuals of a

particular religion to perform work connected with

the carrying on by such corporation, association, or so-

ciety of its religious activities or to an educational in-

stitution with respect to the employment of individuals

to perform work connected with the educational ac-

tivities of such institution.

In addition to the above statutes directly applicable

to these suits, the Congressional intent concerning these

matters has been expressed repeatedly since 1964. An il-

lustration thereof is Public Law 90-557, 82 Stat. 969, which

included the current appropriations for the Departments

of Health, Education and Welfare and Labor. The section

relating to elementary and secondary education, contain-

ing the following clear prohibition is as follows:

No part of the funds contained in this Act may be used

to force bussing of students, abolishment of any school

or to force any student attending any elementary or

secondary school to attend a particular school against

the choice of his or her parents or parent in order to

overcome racial imbalance.

6. Preliminary Statement

Due to the limited time involved it has been impossible

to obtain and file with the Clerk of this Court a transcript

of the entire record of these nine consolidated cases,

which the original Petitioners failed to do. However, for

the purposes of this Response and Cross-Petition, we have

filed under Rule 21.4 transcripts and other portions of the

record originally made in the District Court necessary to

give this Court a full understanding of the necessity of a

full review of the entire record upon which the judgment of

July 3, 1969, as amended, is based, which, upon appeal, be-

35

came a part of the record of the Court of Appeals. These

portions of the record are illustrative of the facts proved

in the District Court and involved in the judgment of the

District Court dated May 16, 1969, and of the Court of Ap-

peals rendered July 3, 1969.

We have chosen the transcript of proceedings in three

typical cases:

(1) John Barnhardt, et als. v. Meridian Separate

School District, et als., Civil Action No. 1300. Meridian is

the largest school district among the fourteen included in

the nine suits now before this Court. See Note 1 on pages