Monell v. New York Dept. of Social Services Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Monell v. New York Dept. of Social Services Brief Amici Curiae, 1976. 3ab1c717-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b4c8cb69-29d1-4552-8e33-18ac280774cd/monell-v-new-york-dept-of-social-services-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

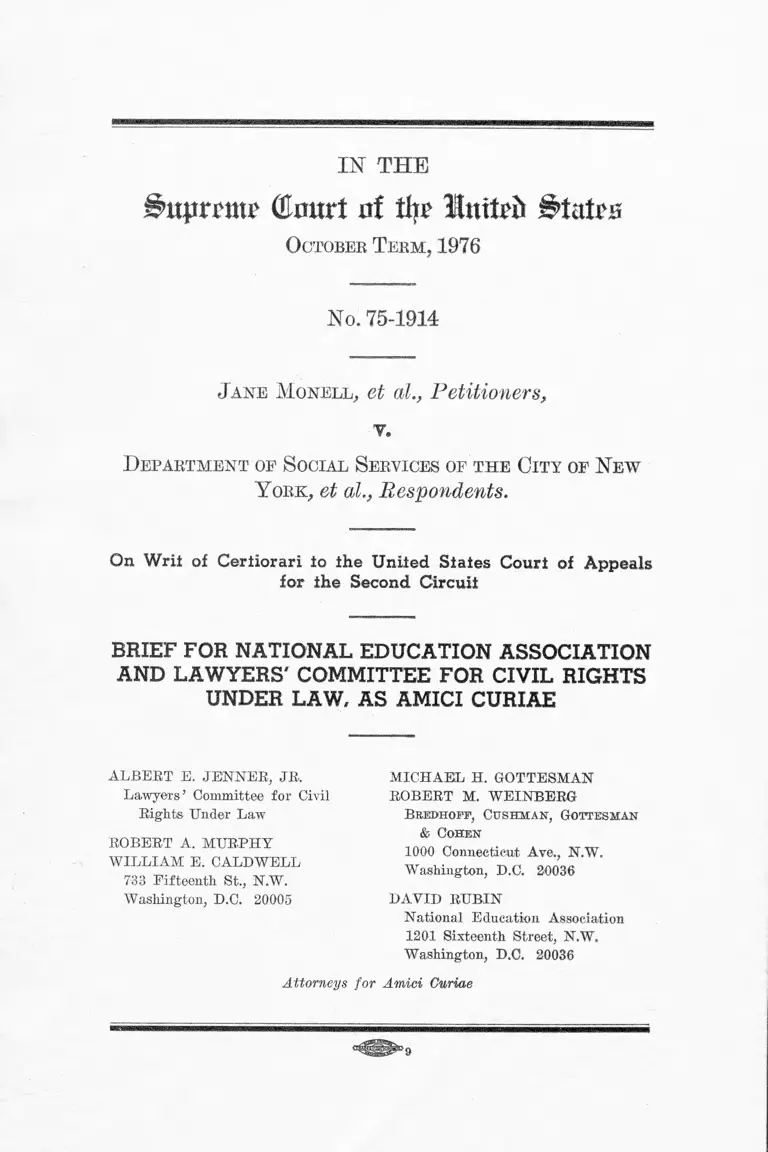

I H T H E

(tort of % Intteft States

O ctober T e r m , 1976

Ho. 75-1914

J a n e M o n e ll , el al., Petitioners,

v.

D e p a r t m e n t op S o cial S ervices op t h e C it y of H e w

Y ork , et al., Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Second Circuit

BRIEF FOR NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION

AND LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

UNDER LAW, AS AMICI CURIAE

ALBERT E. JENNER, JR.

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

ROBERT A. MURPHY

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

733 Fifteenth St., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

MICHAEL H. GOTTESMAN

ROBERT M. WEINBERG

B kedhoff, Cu sh m an , Gottesman

& Cohen

1000 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

DAVID RUBIN

National Education. Association

1201 Sixteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

9

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

I n t e r e s t of t h e A m ic i C u r ia e .................................................. 1

S u m m a r y of A r g u m e n t ............................................ 2

A r g u m e n t .................................................... 6

I. Public Officials in Their Official Capacities Are

“ Persons” Within the Meaning of Section 1983,

No Matter What Relief Is Sought Against Them.

When Public Officials Use the Powers of Their

Office to Violate Constitutional Rights, They

May Be Ordered To Use the Powers of Their

Office To Remedy Their Violations Even Though

the Public Treasury Be Impacted ....................... 6

A. Public Officials in Their Official Capacities

Are “ Persons” Within the Meaning of

§ 1983, No Matter What Relief Is Sought

Against Them, and the Federal Courts Have

Jurisdiction Under 28 U.S.C. §1343 To En

tertain Claims For All Types of Relief

Against Such “ Persons” .................................. 8

B. When Public Officials Use the Powers of

Their Office To Violate Constitutional Rights,

They May Be Ordered To Use the Powers

of Their Office To Remedy Their Violations

Even Though the Public Treasury Be Im

pacted .................................................... 12

II. School Boards Are “ Persons” Within the Mean

ing of § 1983 ................................................................. 27

C o n c l u s i o n ............... ............................................................................... 33

A p p e n d ix : An Analysis of the Legislative History of

the Civil Rights Acts of 1871 As It Relates to the

Issues Presented in This C ase.................................... la

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Abington School Dist. v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203 (1963) 28

Adamson v. California, 332 U.S. 46 (1947) ................... 24

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) . . 13

Aldinger v. Howard, 427 U.S. 1 (1976) ............................ 26

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) .................................. 10

Bell v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678 (1946) ................................... 13

Bemis Bros. Bag Co. v. United States, 289 U.S. 28

(1933) .......... 13

Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 416 U.S. 696

(1974) ............................................................................... 28,29

Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103 (1965) ............... 28

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) . . . 28

Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294 (1962)

4 ,6 ,11,32

Burnet v. Coronado Oil & Gas Co., 285 U.S. 393 (1932) 12

Carter v. West Feliciana School Bd., 396 U.S. 226

(1969) ............................................................................... 28,29

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education,

364 F.2d 189 (4th Cir. 1966)’ ....................................... 21

City of Kenosha v. Bruno, 412 U.S. 507 (1973) . . . .3, 9,10,

11,26

Cleveland Board of Education v. LaFleur, 414 U.S.

632 (1974) ....................................................................2,17, 28

Davis v. Mann, 377 U.S. 678 (1964) ................................ 10

Davis v. School Comm’rs of Mobile County, 402 U.S.

33 (1971) ....................................................."................. 28,29

East Carroll Parish School Bd. v. Marshall, 424 U.S.

636 (1976) .......................................................................... 28

Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974) ....................... 12

17-20

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1880) ....................... 24

Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908) ........................... 19,21

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445 (1976) ................... 19

Flood v. Kuhn, 407 U.S. 258 (1972) ........................... 6,12, 32

Goss v. Lopez, 419 U.S. 565 (1975) .................................... 28

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) . . 28

Griffin v. Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88 (1971) ................... 22

Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) . . . . 7 , 15 ,28

Page

Hagans v. Lavine, 415 U.S. 528 (1974) ........................... 18

Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School District, 427

F.2d 319 (5th Cir. 1970) .............................................. 21

Hatton v. County Board of Education of Maury

County, 422 F.2d 457 (6th Cir. 1970) ....................... 21

Hill v. Franklin County Board of Education of Lincoln

County, 390 F.2d 583 (6th Cir. 1968) ....................... 21

Home Telephone & Telegraph Co. v. Los Angeles, 277

U.S. 278 (1913) ............................................................... 24

Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 1977 (4th Cir. 1966) ___ 21

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colo., 413 U.S.

189 (1973) ............................................................... 28,29

Kramer v. Union School District, 395 U.S. 621 (1969) 28

Lanza v. Wagner, 11 N.Y. 2d 317 (1962) ....................... 27

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U.S. 444 (1938) ................................ 24

McFerren v. County Board of Education of Fayette

County, 455 F.2d 199 (6th Cir.) ................................ 21

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 663 (1963) 28

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) ....................... 27

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450 (1968) 28

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) ...............7, 8,18, 23, 26

Moor v. County of Alameda, 411 U.S. 693 (1973) . . . . 26

Mt, Healthy School Dist. v. Doyle, 45 LAV 4079 (1977) 19

Muzquiz v. City of San Antonio, 528 F.2d 499 (5th

Cir. 1976) ..................................'...................................... 21

North Carolina Teachers A ss’n v. Asheboro City

Board of Education, 393 F.2d 736 (1968) ............... 21

Northcross v. Memphis Board of Education, 412 U.S.

427 (1973) ........................................................ 28

Parden v. Terminal R. Co., 377 U.S. 184 (1963) .......... 19

Pasadena City Bd. of Education v. Spangler, 427 U.S.

424 (1976) ........................................................ 28

People ex rel. Wells & Newton Co. v. Craig, 232 N.Y.

125 (1922) ................................'......................................... 27

Petty v. Tennessee-Missouri Bridge Comm’n, 359 U.S.

275 (1959) ........................................................ 19

Phi]brook v. Glodgett, 421 U.S. 707 (1975) ...................16, 20

Raney v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 443 (1968) . . . . 28

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) ........................... 10

Rizzo v. Goode, 423 U.S. 362 (1976) ............................... 7

Table of Authorities Continued iii

IV Table of Authorities Continued

Page

Rolfe v. County Board of Education of Lincoln

County, 391 F.2d 77 (6th Cir. 1968) ....................... 21

Roman v. Sincock, 377 U.S. 695 (1964) ........................... 10

Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton School Dis-

_ trict, 365 F.2d 770 (8th Cir. 1966) ........................... 20

Smith v. Hampton Training School for Nurses, 360

F.2d 577 (4th Cir. 1966) ............................................ 21

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Part, 396 U.S. 229 (1969). . 13

Swann v. Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ___ 7,28

Swann v. Charlotte-MecMenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1 9 7 1 )........................................................... .. 15

United States v. Price, 383 U.S. 787 (1966) ................... 22

Vlandis v. Kline, 412 U.S. 441 (1973) ........................... 11, 17

Von Hoffman v. City of Quincy, 71 U.S. 535 (1867) . . 25

Wicker v. Hoppock, 6 Wall. 94.(1867) .............................. 13

WMCA, Inc. v. Lomenzo, 377 U.S. 633 (1964) ............... 10

C o n s t it u t io n an d S t a t u t o r y P ro visio n s :

Constitution of the United States:

Fifth Amendment ............................................................. 31

Fourteenth Amendment ........................... 2, 19, 22-24, 26, 31

Eleventh Amendment ..............................4, 5, 9,14,17-19, 21

United States Code:

20 U.S.C. ^ 1601(b)(1), 1605(a)(1) (A) (i)

20 U.S.C. § 1617 . . . .

20 U.S.C. * 1656 ...........

20 U.S.C. § 1702(a)(3) .............

20 U.S.C. $ 1702(b) ' .............

20 U.S.C. 1 1713 ..........

28 U.S.C. i 1343 .................

42 U.S.C. ' 1983 ...................

42 U.S.C. 1 1988 .......................

42 U.S.C. 'U 2000c-6, 2000c-8...........

. 16

16, 30

. 30

15, 31

. 16

.. . 31

passim

passim

. . . 13

. . . 29

L e g isla tiv e M a te r ia ls :

Cong. Globe, 42cl Cong., 1st Sess, passim

IN THE

j3>uprm? (Emtrt of the lulled Stales

O ctober T e r m , 1976

No. 75-1914

J a n e M o n e ll , et al., Petitioners,

v.

D e p a r t m e n t of S ocial S ervices of t h e C it y of N ew

Y o r k , et al., Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Second Circuit

BRIEF FOR NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION

AND LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

UNDER LAW, AS AMICI CURIAE

INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE i

The National Education Association (N EA) is the

largest teacher organization in the United States, with

a membership of approximately 1.5 million educators,

virtually all of whom are employed by public educa

tional institutions. One of N EA ’s purposes is to safe

guard the constitutional rights of teachers and other

public educators.

1 The parties have consented to the filing of this brief and their

letters of consent are being filed with the Clerk of this Court pur

suant to Rule 42(2) of the Rules of this Court.

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under

Law is a non-profit corporation organized in 1963 at the

request of President Kennedy. Its Board of Trustees

includes nine past presidents of the American Bar

Association, two former Attorneys General, and two

former Solicitors General of the United States. The

Committee’s primary mission is to involve private

lawyers throughout the country in the quest of all

citizens to secure their civil rights through the legal

process.

The resolution o f this case will have an important

impact upon the extent to which those who are injured

by the unconstitutional actions of public officials and

entities can secure complete relief in the federal courts.

Both amici have a vital interest in the resolution of

this case.

This brief is filed to provide the Court with the views

of amici, refined through extensive litigation under the

Fourteenth Amendment and 42 U.S.C. § 1983, that

actions can be maintained under § 1983 against public

officials in their official capacities and against school

boards to secure complete relief, including relief which

impacts upon the public treasury.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Plaintiffs brought this action under § 1983 against

a school board, a city department, and various public

officials in their official capacities, alleging that these

defendants had violated plaintiffs’ rights by requiring

them to stop working during their last two months of

pregnancy. Cf. Cleveland Board of Education v.

LaFleur, 414 U.S. 632, 638 (1974). As remedies, plain

tiffs sought declaratory and injunctive relief (now

3

moot, because defendants have rescinded the policies

winch required pregnant employees to stop working),

and payment of the salaries which they would have

received but for the unconstitutional interruption o f

their employment.

The court below held that there is no federal

jurisdiction over this action under 28 U.S.C. § 1343(3),

because none of the defendants is a “ person” who may

be (sued under § 1983. More precisely, the court held

that the school board and city department can never be

“ persons” under § 1983, and that public officials in

their official capacities are “ persons” when sued for

declaratory and injunctive relief, but are not “ per

sons” when sued for retroactive monetary relief.

In Part I-A o f this brief, we (show that the court

ened in holding that the public officials are not “ per

sons” when sued for monetary relief under § 1983.

Public officials in their official capacities are either

“ persons” suable under § 1983 or they are not. There

is no basis for bifurcating their “ person” status de

pending on the nature of the relief sought. City of

Kenosha v. Bruno, 412 U.S. 507 (1973). This Court

has entertained and approved relief in numerous § 1983

eases against public officials in their official capacities.

A finding, implicit or explicit, that such defendants

are ‘ persons” suable under § 1983 was a necessary

predicate to this Court’s resolution of those cases,

particularly in light of this Court’s duty sua sponte

“ to see to it that the jurisdiction of the [district

court] . . . is not exceeded.” City of Kenosha v.

Bruno, supra, 412 U.S. at 511. Moreover, Congress has

closely scrutinized these § 1983 decisions and has

evinced no dissatisfaction wiith the definition of “ per

sons ’ established therein. Too many important de

cisions of this Court have proceeded on the premise

4

that public officials in their official capacities are “ per

sons” under § 1983 for the question to be considered

other than settled. Brown Shoe Co. v. United States,

370 U.S. 294, 306-307 (1962). It follows that there

was jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1343 to entertain

the monetary claim against the public officials.

Of course, even though there he jurisdiction over

the claim, it would be defeated on its merits i f it could

he shown that Congress intended in § 1983 to restrict

the forms of relief available against this category of

“ persons” so as to preclude monetary relief which

would be paid from the public treasury. While

the Court below did not address this “ merits” issue,

we go on in Part I-B to show that Congress did not!

intend to restrict the scope of available relief in this

fashion. On its face, § 1983 creates a cause of action

for “ redress” by the “ party injured” against “ every

person” violating constitutional rights, and creates the

broadest possible avenue to relief: through “ an action

at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding.”

These words do not admit of the interpretation that

Congress meant the “ injured party” to go without

“ redress” when the injury is monetary and the wrong

doing “ persons” are public officials. By logic, if

Congress in enacting § 1983 had intended “ to protect

municipal treasuries,” as the Court below stated, then

it would have permitted no award against public offi

cials which impacts on municipal treasuries. But, this

Court has already decided in numerous cases that relief

may be granted against public officials in their official

capacities, and Congress has accepted, indeed built

upon, these decisions. Further, the Eleventh Amend

ment “ analog}7-” to which the court below refers, has

no application here. The line drawn in Eleventh

Amendment eases between prospective and retroactive

relief is a product of this Court’s effort to reconcile

competing constitutional interests; it makes no sense

as a means to determine the intent of the 1871 Congress

in enacting § 1983, and in fact leads to a distortion of

the manifest congressional purpose. The importation

of the Eleventh Amendment line into § 1983 would

contravene the central purpose of § 1983—to provide

a complete federal remedy for federal constitutional

wrongs committed under color of state law—without-

serving any other purpose which the Congress that

enacted § 1983 meant to achieve. The enactors did not

intend to insulate municipal treasuries from suits to

remedy constitutional wrongs. We detail the legislative

history which proves this.

In Part II, we show that the court below also erred

in holding that school boards are not “ persons” under

§ 1983. As consistently as this Court has treated

other governmental entities as outside the ambit of

§ 1983 and § 1343(3), so equally consistently (and in

far greater volume) has this Court treated school

boards as within the ambit of those provisions. In

case after ease, particularly in the school desegregation

area, this Court has entertained § 1983 action's in

which school boards were defendants, and indeed has

on numerous occasions issued, directed, or approved

orders in such eases against school boards. Congress

has followed these decisions closely and has assumed

from these decisions, and acted upon the assumption,

that school boards are subject to suit by private par

ties. In 1964, 1972, and 1974, Congress enacted into

law statutes founded on that assumption. In addition,

Congress has failed to enact bills introduced from

time to time to withdraw or limit federal court juris

diction to entertain suits against school boards. In

6

the light of this history, the question whether school

boards are “ persons” under § 1983 must be regarded

as settled in the affirmative. See Brown Shoe Co. v.

United States, supra, 370 U.S. at 306-307; Flood v.

Kuhn, 407 U.S. 258, 282-284 (1972). It follows that

there was jurisdiction under 28 U.'S.C. § 1343 to enter

tain the monetary claims against the school board, and

that on the merits such relief may be awarded, where

appropriate, under § 1983.

A R G U M E N T

I. PUBLIC OFFICIALS IN THEIR OFFICIAL CAPACITIES

ARE "PERSONS" WITHIN THE MEANING OF SECTION

1983, NO MATTER W H AT RELIEF IS SOUGHT AGAINST

THEM. WHEN PUBLIC OFFICIALS USE THE POWERS

OF THEIR OFFICE TO VIOLATE CONSTITUTIONAL

RIGHTS, THEY M A Y BE ORDERED TO USE THE

POWERS OF THEIR OFFICE TO REMEDY THEIR VIO

LATIONS EVEN THOUGH THE PUBLIC TREASURY

BE IMPACTED.

As we understand it, the theory of this action, inso

far as it is directed at public officials in their official

capacities, is as follows: when public officials, exercis

ing the powers of their office, violate the federal Con

stitution and thereby injure private parties, the in

jured parties may sue under § 1983, and the court is

empowered to require the wrongdoing officials to exer

cise “ the power that is theirs” 2 to repair the injury

done—here, to pay the back salaries which plaintiffs

would have received but for the officials’ unconstitu

tional actions. The theory depends upon two proposi

tions: (a) that there is jurisdiction to entertain such

a § 1983 claim; and (b) that, on the merits, if the de

fendant public officials have the power to “ make good

2 Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218, 233 (1964).

7

the wrong done,” § 1983 permits remedies which re

quire those officials to exercise that power even where

doing so impacts upon the treasury of the entity which

they serve.1 * 3 The count below found that plaintiffs’

theory foundered on the first proposition—it held that

as the public officials are not “ persons,” there is no

jurisdiction to entertain the claim. The court did not

reach or discuss the second proposition. W e deal with

both propositions herein.

3 The theory is applicable only where the wrongdoing officials

hold positions of responsibility empowering them to provide the

relief sought. Not every act of misconduct by every municipal em

ployee can lead to an order against him in his official capacity

impacting upon the public treasury. The courts can do no more

than order wrongdoing officials to exercise “ the power that is

theirs” to right the wrongs which they have committed through

their offices. Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218, 233 (1964).

See also Swann v. Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 30 (1971).

Although a court may have jurisdiction over a public official, it

cannot instill him with powers to undo his wrong which he does

not possess by virtue of his office. The wrongdoing policemen

in Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961), could not have been

ordered to make their victims whole from the public treasury—

their official powers did not extend that far. Nor could such

relief have been directed at their superiors who did have such

powers, for those superiors were not. wrongdoers. As this Court

explained in Rizzo v. Goode, 423 U.S. 362, 377 (1976), distinguish

ing Swann and Brown, relief may be obtained only against those

responsible for the wrong:

1 ‘ Those against whom injunctive relief was directed in cases

such as Swann and Brown were not administrators and school

board members who had in their employ a small number of

individuals, which latter on their own deprived black students

of their constitutional rights to a unitary school system. They

were administrators and school board members who were found

by their own conduct in the administration of the school system

to have denied those rights. Here, the District Court found

that none of the petitioners had deprived the respondent

classes o f any rights secured under -the Constitution.”

A. Public Officials in Their Official Capacities Are "Persons"

Within the Meaning of § 1983, No Matter What Relief Is

Sought Against Them, and the Federal Courts Have Juris

diction Under 28 U.S.C. § 1343 To Entertain Claims for All

Types of Relief Against Such "Persons."

The court below did not question that there would

have been jurisdiction in the district court to hear and

resolve plaintiffs’ claims against the public officials

had injunctive or declaratory relief been sought:

“ There is no doubt that municipal and state officials,

sued in their official capacities, are ‘ persons’ within

the meaning of [42 U.S.C.] § 1983 when they are sued

for injunctive or declaratory relief.” 4 The court

ruled, however, that these same defendants are not

“ persons” within the meaning of § 1983 when they are

sued for monetary relief, and therefore that “ [w]e

are . . . without jurisdiction to hear this suit.” 5

The court below founded its analysis upon this

Court’s decision in Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167

(1961), which held, inter alia, that in a suit for money

damages a municipality is not a person within the

meaning of what is now codified as § 1983. The court

below reasoned as follows: (a) the Department of So

cial Services and the school board here are in effect

part of the City of New York and thus, under Monroe,

not “ persons” in their own rights; (b) the monetary

relief sought against the public officials in their official

capacities would in fact come out of the treasuries of

the Board of Education and the City of New York:

consequently (c) the real parties in interest are the

City and the Board and not the named public officials;

and (d) suits against public officials may not be used

8

4 Pet. A. 53-54.

5 Pet. A. 60.

9

as a “ subterfuge” to sue non-“ persons,” and thus

jurisdiction does not lie under § 1343(3).® (W e as

sume, for purpose of our argument in Part I, that as

the court below held, school boards are not “ persons.”

Of course i f they are “ persons,” as we show they are

in Part II, there could be no inhibition upon suits

against school boards or their officials for relief im

pacting upon their treasuries.)

Significantly, the court below completed the fore

going analysis without dealing with this Court’s deci

sion in City of Kenosha v. Bruno, 412 TI.S. 507 (1973)

—a decision which cannot be reconciled with the hold

ing below that public officials are “ persons” for de

claratory and injunctive relief but not for monetary

refief. In Kenosha, this Court held that a municipality

is not a “ person” suable under § 1983 for any relief,

declaratory or injunctive as well as monetary. Given

the Kenosha holding, the logic of the court of appeals’

analysis would apply equally to preclude jurisdiction

of a claim for declaratory or injunctive relief against

a public official in his official capacity, where the real

impact of that relief would be felt by the entity which

is not a “ person.” Just as with monetary relief, it

could be said that to entertain a suit against the public

official in his official capacity for such declaratory or

injunctive relief would be sanctioning a “ subterfuge”

to accomplish indirectly what cannot be done directly. 6

6 Pet. A. 55-61. Although recognizing that the Eleventh Amend

ment is inapplicable to this case, the court below thought that the

case law developed under that Amendment furnished “ a com

pelling analogy” for its ruling. Id. at 56. In fact, the analogy

is wholly flawed. We defer our demonstration on. this point to

Part I-B, infra, for even if the analogy were valid it would go to the

scope of the federal court’s remedial power, not to its jurisdiction.

10

Kenosha found no evidence in the legislative history

of § 1983 or in its language “ to suggest that the ge

neric word ‘ person’ was intended to have a bifurcated

application to municipal corporations depending on the

nature of the relief sought against them.” 412 U.S.

at 513. The same is true as to public officials. The

statute prescribes the same cause of action, in the same

terms, against “ every person.” And there is not a

word in the legislative history suggesting that public

officials are '“ persons” for some purposes but not

others. Thus, there is no more basis here than in

Kenosha for bifurcating the “ person” status of the

defendants. Regardless of the relief sought, there must

be but a single answer to the question whether a public

official in his official capacity is a “ person” suable

under § 1983.

That answer has already been provided by this Court

in dozens of cases. For decades, this Court has en

tertained and decided § 1983 actions against public

officials in their official capacities; indeed, all of the

Court’s school desegregation and legislative reappor-

tionment decisions have been rendered in such actions.7

In all of these cases the public entity was the “ real

7 The school desegregation eases are cited infra p. 28, n. 28. The

legislative reapportionment cases include Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S.

186 (1962) ; Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 537 (1964) ; WMCA,

Inc. v. Lomenzo, 377 U.S. 633, 635 (1964) ; Davis v. Mann, 377 U.S.

678, 680 (1964) ; Roman v. Sincock, 377 U.S. 695, 697 (1964).

Of course, in all the school desegregation cases, suit was brought

not only against the public officials in their official capacities,

but also against the school board itself. It is possible, therefore,

that this Court entertained those cases because school boards are

themselves “ persons” under § 1983. In that event, those cases

establish that there is no jurisdictional problem here, at least with

respect to that portion of the case concerning school board em

ployees, for here too suit was brought against the school board

as well as against the public officials. See part II, infra.

11

party in interest,” and in many the relief awarded

impacted directly upon the entity’s treasury.8

It is true that in none of these cases was the issue

whether public officials in their official capacities are

“ persons” directly addressed. But a finding, implicit

or explicit, that such defendants are “ persons” suable

under § 1983 was a necessary predicate to this Court’s

entertaining those cases and approving relief therein,

particularly as this Court has recognized its duty—in

the context of a case brought pursuant to § 1983 and

§ 1343(3)—siia sponte “ to see to it that the jurisdiction

of the [district court] which is defined and limited by

statute, is not exceeded,” City of Kenosha v. Bruno,

supra, 412 U.S. at 511. It is not without significance

that on the very day that Kenosha was decided, holding

sua sponte that public entities may not be sued under

§ 1983, this Court affirmed an order in another § 1983

action directing a public official to reimburse excess

tuition payments which had been improperly collected

from students. Vlandis v. Kline, 412 U.S. 441, 444-445,

454 (1973).

Notwithstanding the absence of express considera

tion, these many decisions by this Court surely con

stitute stare decisis on the issue whether public em

ployees in their official capacities are “ persons” under

§ 1983. Too many important decisions of this Court

have proceeded on that premise for the question to be

considered other than settled. As this Court stated in

Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 306-307

(1962):

“ While we are not bound by previous exercises of

jurisdiction in cases in which our power to act was

8 We cite and describe these cases infra, pp, 15, 17.

12

not questioned but was passed sub silentio, . . .

neither should we disregard the implications of an

exercise of judicial authority assumed to be proper

for over 40 years.”

Adherence to the rule implicitly established by these

§ 1983 cases is particularly appropriate here, for the

rule is one of statutory construction (rather than con

stitutional interpretation).0 Congress has been free to

change it, }ret, despite close congressional scrutiny of

the pertinent decisions, Congress has evinced no dis

satisfaction with the rule.10

In sum, there is no room for a holding that public

officials in their official capacities are not “ persons”

suable under § 1983, and the court below erred in rilling

that there was no § 1343 jurisdiction over plaintiffs’

claim against these defendants. There remains the

“ merits” question, which the court below did not reach,

whether there are special limitations upon the relief

which can be awarded against these defendants, and it

is to that question that we now turn.

B. When Public Officials Use ihe Powers of Their Office To

Violate Constitutional Rights, They May Be Ordered To

Use the Powers of Their Office To Remedy Their Viola

tions Even Though the Public Treasury Be Impacted.

It is a familiar principle of federal law that

when a federal court, has jurisdiction over a defendant

who has violated constitutional rights, it will ordinarily

0 Burnet v. Coronado Oil & Gas Co., 285 U.S. 393, 406-408 (1932)

(Brandeis, J., dissenting), quoted with approval in Edelman v.

Jordan, 415 U.S. 651, 671 n.14 (1974).

10 Cf. Flood v. Kuhn, 407 U.S. 258, 282-284 (1972). We diseuss

the congressional response to the Court’s' desegregation decisions

infra, pp. 15-16, 30-32.

13

require him to do what he can to repair the 'damage.

“ [ I ] t is . . . well settled that where legal rights have

been invaded, and a federal statute provides for a

general right to sue for such invasion, federal courts

may use any available remedy to make good the wrong

done.” Bell v. Hood, 327 TJ.S. 678, 684 (1946).11 On

its face, § 1983 is such a statute. It creates a cause of

action for “ redress” by the “ party injured” against

11 every person” violating constitutional rights, and

prescribes the broadest possible avenue to relief:

through “ an action at law, suit in equity, or other

proper proceeding.” See also 42 U.S.C. § 1988. These

words do not seem to admit of the interpretation that

Congress meant the “ injured party” to go without

“ redress” when the injury is monetary and the wrong

doing “ persons” are public officials. In the face of this

unequivocal statutory language, it is difficult to see any

basis for not applying the ordinary rule that federal

courts “ will make good the wrong done.” Any advo

cate to the contrary should be required to bear a heavy

burden of persuasion.

The couid below did not address this question in

these terms, for it mistakenly disposed of the case on

jurisdictional grounds. But it is easy to see from its

11 ‘ The existence of a statutory right implies the existence of

all necessary and appropriate remedies.” Sullivan v. Little Hunt

ing Park, ,396 II.S. 229, 239 (1969). “ The general rule is, that

when a wrong has been done, and the law gives a remedy, the com

pensation shall be equal to the injury,” Wicker v. Hoppock, 6

Wall. 94, 98 (1867), reaffirmed in Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 TJ.S. 405, 418-19 (1975). Justice Cardozo put the principle

in these words: “ Once let it be ascertained that the amount is

determinable and all that follows is an incident . . . . [Office a

wrong is brought to light [, tffiere can be no stopping after that

until justice is done.” Bemis Bros. Bag Co. v. United States, 289

TT.S. 28, 35-36 (1933).

M

opinion how it would have answered i t : the court below

thought that “ the Reconstruction Congress which en

acted the Civil Rights Act sought to protect municipal

treasuries,” 12 and no doubt would have concluded that

Congress intended to restrict the relief available

against public officials commensurately with that ob

ject. Although the logical implementation of such an

understanding of congressional intent would be to per

mit no award against public officials which impacts on

municipal treasuries, the court below, which perceived

a “ compelling analogy” in the Eleventh Amendment

cases,13 presumably would have precluded only awards

of retroactive monetary relief.

We will show herein that in § 1983 suits against pub

lic officials neither the complete prohibition of awards

which impact upon municipal treasuries nor the pre

clusion only of awards of retroactive monetary relief

from such treasuries is a defensible result. In doing

so, we will proceed as follows: First, this Court has

already decided in numerous cases that relief may be

granted which impacts upon the public treasury in

§ 1983 suits against public officials in their official

capacities, and Congress has accepted, indeed built

upon, those decisions. Second, the Eleventh Amend

ment “ analogy” to which the court below refers is the

product of this Court’s effort to reconcile competing

constitutional interests; it makes no sense as a means

to determine the intent of the 1871 Congress in enact

ing § 1983, and in fact leads to a distortion of the

manifest congressional purpose.

1. A construction that § 1983 precludes all awards

against public officials impacting upon public treas-

12 Pet, A. 59.

13 Pet. A. 56.

15

uries could not be reconciled with the many decisions

of this Court in § 1983 actions against public officials

requiring the expenditure of enormous sums from local

governmental treasuries—decisions which Congress has

followed closely, legislated about, but never chosen to

overturn.

Many of this Court’s school desegregation decisions,

for example, have required large expenditures from

local government treasuries. The leading example is

Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218, 233 (1964), where

the Court authorized issuance of an order requiring

public officials “ to exercise the power that is theirs

to levy taxes to raise funds” if necessary to reopen the

public schools. And, in Swann v. Ckarlotte-Mecklen-

hurg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 30, and n.12

(1971), the Court affirmed a busing order requiring

“ local school authorities” “ to employ 138 more buses

than [the school system] had previously operated.”

Congress, aware that the Court has issued orders

against public officials requiring them to expend public

funds, has not amended either 42 U.S.C. § 1983 or 28

U.S.C. § 1343(3) to withdraw the federal courts’ au

thority and/or jurisdiction to issue such orders; on

the contrary, Congress has expressly declared its inten

tion not to do so.

In 1974, Congress found that “ the implementation of

desegregation plans that require extensive student

transportation has, in many cases, required local edu

cational agencies to expend large amount[s] of funds,

thereby depleting their financial resources . . .” 20

U.S.C. § 1702(a) (3). Congress’ response was not to

withdraw either jurisdiction or judicial power to re

quire such plans, but simply to legislate revised eviden

16

tiary standards and remedial priorities to be employed

by the courts in deciding such cases.14 And lest that

step be misunderstood as a statutory withdrawal of

judicial power or jurisdiction, Congress took care to

declare expressly that “ the provisions of this chapter

are not intended to modify or diminish the authority

of the courts of the United States to enforce fully the

fifth and fourteenth amendments to the Constitution of

the United States.” 20 U.S.C. § 1702(b).15

Either the 1871 Congress really did intend to “ pro

tect municipal treasuries,” or it did not. I f it did, and

if there had been no intervening developments, the

solution would be clear: the Court would be required

to “ give effect to the legislative will,” PMlbrook v.

Glodgett, 421 U.S. 707, 713 (1975), by forbidding all

remedies in § 1983 actions which impact monetarily

upon public treasuries. But, of course, there have

been intervening developments: this Court has re

peatedly approved just such remedies—both “ pros

pective,” as we have just shown, and “ retroactive,”

as we show below—• and the modern Congress has

responded by expressly affirming its desire not to

“ modify or diminish” the power o f the federal courts

14 20 U.S.C. §§ 1703-05, 1712-18, 1752-58.

15 In 1972, Congress had similarly found that “ the process of

eliminating or preventing minority group isolation . . . involves

the expenditure of additional funds to which local educational

agencies do not have access.” 20 U.S.C. § 1601(a). Then, too,

Congress’ response was not to cut back on the federal courts’

statutory powers or jurisdiction, but rather to reaffirm the pro

priety of their exereise. Congress decided “ to provide financial

assistance” to enable local educational agencies to meet the de

mands of these court orders, 20 U.S.C. §§ 1601(b)(1), 1605(a)(1)

(A ) (i), and enlarged upon the remedies available in such actions

by expressly authorizing attorney’s fee awards, 20 U.S.C. § 1617.

17

'to award such remedies. Under these circumstances,

this Court’s prior decisions must be taken to preclude

a holding that public treasuries can never be affected.

2. A construction of § 1983 which would permit

orders requiring public officials to spend public funds

prosepectively, while precluding orders against such

officials directing retroactive monetary payments

from the public treasury, would also collide with

prior decisions of this Court. In Vlandis v. Kline,

supra, 412 U.S. at 444-445, 454, a § 1983 case, this

Court affirmed an order requiring a public official to

reimburse excess tuition payments collected in viola

tion of constitutional rights. Similarly, in Cleveland

Board of Education v. La Fleur, 414 U.S. 632, 638

(1974), a § 1983 case, this Court affirmed as “ appro

priate relief” a backpay award to pregnant teachers

unconstitutionally suspended from employment (see

326 P. Supp. 1159, 1161 (EJD. Va. 1971)). Cf. Edel-

many. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974) (all opinions in this

case either expressly declare or implicitly assume that,

where the Eleventh Amendment is inapplicable, retro

active monetary relief from a public entity’s treasury

may be awarded in a § 1983 action against public offi

cials in their official capacities).16

16 Edelman was a § 1983 action brought against officials of the

State of Illinois seeking, inter alia, an order requiring the defend

ants to provide benefits which would have been paid but for their

unlawful delays.

The Court began its analysis with the recognition that, the

monetary award, although addressed to the public officials, would

in fact be paid from the public treasury— in this instance, the

state treasury. ‘ ‘ These funds will obviously not be paid out of

the pocket of petitioner Edelman . . . The funds to satisfy the

award in this case must inevitably come from the general revenues

of the State of Illinois.” 415 U.S. at 664, 665. The Court then

ruled, by a 5-4 vote, that such an award was precluded by the

Eleventh Amendment.

For present purposes, the important part of Edelman is not

But, even passing these prior decisions, nothing can

be found on the face of § 1983 or in its legislative his

tory to justify distinguishing between prospective and

retroactive relief. Such justification as can be made

for such a distinction must come not from anything

internal to § 1983 or its background but from the

“ compelling analogy” of this Court’s Eleventh

its construction of the Eleventh Amendment— as we show below,

the Eleventh Amendment is inapplicable here because it protects

only state treasuries, not local school board treasuries—but the

apparent unanimity on the Court that but for the Eleventh

Amendment the monetary relief would have been recoverable under

§ 1983 despite the fact that it came from the treasury of a public

entity (the State) not itself a “ person” under § 1983.

Initially, it is apparent that, if § 1983 did not authorize mone

tary awards against public officials payable from public funds,

there would have been no occasion for the Court to discuss the

Eleventh Amendment at all in Edelman. Pursuant to the policy

of avoiding unnecessary constitutional adjudication (see, e.g.,

Hagans v. Lavine, 415 T.T.S. 528, 546-547 (1974)), the Court need

only have declared that 5 1983 itself did not authorize the award,

and the case would have been over. Only if the Court was of

the view that $ 1983 otherwise would reach the public treasury

was it appropriate to reaeh the constitutional question whether the.

Eleventh Amendment dictated a contrary result.

All four dissenters in Edelman (including the author of Monroe

v. Pape) would have allowed the recovery against state officials

even though it was to be paid from state funds. 415 TJ.S. at 678-

687 (Douglas, J., dissenting) ; ul. at, 687-688 (Brennan, J., dissent

ing) ; ul. at. 688-696 (Marshall, J., joined by Blackmnn, J., dissent

ing). The majority, of course, disagreed, but not because of any

limitation found in § 1983 itself. Rather, the majority concluded

that the Eleventh Amendment constituted an independent restric

tion upon the scope of relief available in federal court 415 U S

at 677:

“ Though a § 1983 action may be instituted by public aid re

cipients such as respondent, a federal court’s remedial power,

consistent with the Eleventh Amendment, is necessarily lim

ited to prospective injunctive relief . . . and may not include

a retroactive award which requires the payment of funds

from the state treasury . . (emphasis added; footnotes

omitted).

19

Amendment decisions.17 As we show, this “ analogy”

cannot bear examination.

The distinction between retroactive and prospective

relief for purposes of the Eleventh Amendment does

not purport to be an expression of the will of the fram

ers of that Amendment. Rather, it represents the

culmination of this Court’s effort—begun with the

creation of the fiction of Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123

(1908)—to reconcile the clash of values established by

two constitutional amendments, adopted more than 60

years apart: on the one hand, the “ sword” o f the

Fourteenth Amendment;18 on the other, the “ shield” of

the Eleventh.19 The Eleventh Amendment wais de

signed to insulate state treasuries against federal

court awards;20 the Fourteenth Amendment was de

signed to place limitations upon states in their treat

ment of private persons.21

The line ultimately drawn in Edelman v. Jordan,

supra, evolved from a series of decisions confronting

different aspects of the apparent tension between the

two amendments. This end product—-the line between

prospective and retroactive monetary relief—is one

which “ will not in many instances! be that between

17 As the court below recognized, the Eleventh Amendment has

no direct application to this case, because neither cities nor local

school boards enjoy Eleventh Amendment protection. Edelman v.

Jordan, supra, 415 TJ.S. at 667, n. 12 ; Mt. Healthy School Dist.

v. Doyle, 45 LW 4079, 4081 (1977).

18 Edelman v. Jordan, supra, 415 U.S. at 664.

10 Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445, 448 (1976).

20 Petty v. Tennessee-Missouri Bridge Comm’n, 359 U.S. 275, 276

n. 1 (1959) ; Parden v. Terminal R. Co., 377 U.S. 184, 187 (1963).

21 Fitzpatrick, supra, 427 U.S. at 456.

20

day and night.” Edelmcin, 415 U.S. at 667. This

Court did not attempt in Edelman to explain the re-

sult as a logical distinction which Congress would

have drawn starting from first principles, but as the

evolved harmonization of conflicting constitutional

interests.

To import the line drawn in such fashion into the

meaning of § 1983 would make no sense. W e are

concerned here with the interpretation of a single

enactment of Congress. “ Our objective in a ease such

as this is to ascertain the congressional intent and give

effect to the legislative will.” Philbrool> v. Glodgett,

supra, 421 U.S. at 713. While it is theoretically

possible that a Congress might choose to draw the line

between prospective and retroactive monetary awards

impacting upon a municipal treasury, there is not a

shred of evidence in the legislative debates to suggest

that the Congress of 1871 in fact intended to draw such

a line in § 1983. Nor is there anything so inherently

“ right” about the line to attribute it to Congress with

out any foundation in the language or history of the

Act. Is it likely, for example, that Congress intended

to empower the federal courts to require massive ex

penditures from public treasuries to achieve desegre

gation, while at the same time intending to withhold

power from those courts to award back salaries from

the same treasuries to the black teachers discrimina-

torily selected for dismissal and non-renewal as de

segregation plans were implemented1? 22 It would be a

22 Cases are common in which the lower federal courts have up

held the propriety in § 1983 cases of backpay awards to black

teachers who were discriminatorily selected for dismissal or non-

renewal when school integration necessitated force reductions. See,

e.g., Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton School District, 365

21

most remarkable coincidence if Congress in 1871 bad

drawn the precise line which did not begin to be

drawn in the Eleventh Amendment cases until 1908

and did not reach final shape until 1974 following

decades of litigation.23

More important, the importation of the Eleventh

Amendment line into § 1983 would contravene the cen

tral purpose of that statute— to provide a complete

federal remedy for federal constitutional wrongs com

mitted under color o f state law—without serving any

other purpose which the Congress that enacted § 1983

meant to achieve. The language of § 1983 and its legis

lative history make clear that the competition of values

which led to the distinction between prospective and

retroactive relief for purposes of the Eleventh Amend

ment has no analogous counterpart in § 1983. The lat

ter provision was intended to be broadly remedial and

its enactors did not seek to “ protect municipal treas

1.2d 770, 783-784 (8th Cir. 1966) (Bl'ackmun, J.) ; Chambers v.

Hendersonville City Board of Education, 364 F.2d 189, 193 (4th

Cir. 1966) ( en banc) ; Hill v. Franklin County Board of Educa

tion, 390 F.2d 583 (6th Cir. 1968) ; Rolfe v. County Board of Edu

cation of Lincoln County, 391 F.2d 77, 81 (6th Cir. 1968); Hatton

v. County Board of Education of Maury County, 422 F.2d 457

(6th Cir. 1970) ; Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School District,

427 F.2d 319, 323 (5th Cir. 1970) (Bell, J.) (Compare: Muzquiz

v. City of San Antonio, 528 F.2d 499 (5th Cir. 1976) (en banc)) ;

Mc-Ferren v. County Board of Education of Fayette County, 455

F.2d 199 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 407 U.S. 934 (1972). See also,

Smith v. Hampton Training School for Niirses, 360 F.2d 577 (4th

Cir. 1966) (en banc) ; .Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 1977 (4th Cir.

1966) (en banc), cert, denied, 385 U.S. 1003 (1967) ; North Caro

lina Teachers Ass’n v. Asheboro City Board of Education, 393 F.2d

736 (4th Cir. 1968) (en banc).

The Eleventh Amendment line began to be drawn in Ex parte

Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908), and reached its present contours only

with the decision of Edelman in 1974.

22

uries.” Congress established a sword in § 1983, but no

shield.

Analysis of what Congress meant must begin with

what was enacted. In its terms, as described above,

§ 1983 provides to the “ party injured” a cause of ac

tion for “ redress” “ in an action at law, suit in equity,

or other proper proceeding” against “ [e] very person”

who violates its substantive provisions. This Court, in

the context of interpreting another portion of the Civil

Rights Act of 1871, stated that the approach to Recon

struction civil rights statutes is to “ ‘ accord [them] a

sweep as broad as [their] language.’ ” Griffin v. Breck-

enridge, 403 U.S. 88, 97 (1971), quoting from United

States v. Price, 383 U.S. 787, 801 (1966). On its face,

§ 1983—and it is here the meaning of that provision

alone which is at issue—provides for complete “ re

dress” against “ every person” who violates its terms.

That language in itself, cannot constitute the basis for

finding a prohibition of retroactive monetary relief

against any “ person.”

The legislative history of § 1983 confirms a remedial

purpose as broad as its language. We analyze that

history in great detail in the appendix which follows

this argument. That analysis shows that Congress in

passing what is now § 1983 meant to establish a private

cause of action for redress as broad as it was empow

ered to create by the Fourteenth Amendment. Not a

word said in connection with the enactment of § 1983

indicates the slightest intention to leave a party injured

by a Fourteenth Amendment violation with less than a

full remedy. Indeed, the contrary is true: complete

remedy for such constitutional violations was Congress’

preoccupation. See pp. 5a-13a, infra. In this connec

tion, nothing in the debates over § 1983 indicates any

23

congressional concern to “ protect municipal treas

uries.” I f anything, the evidence is strong that Con

gress meant municipalities to be subject to suit under

§1983 directly as “ persons.” Congress understood

that the Fourteenth Amendment applied to restrict

the actions of municipalities, and § 1983 was intended

to create a private cause of action as broad as the scope

of that Amendment (see pp. 15a-16a, infra) ; and, a

month before the introduction of the bill containing

§ 1983, and less than two months before its passage,

Congress had enacted a definitional statute to assist in

the construction of subsequently enacted statutes, which

provided that except where there was evidence of a

contrary congressional intent the term “ persons”

should be understood to include “ bodies politic and

corporate.” See pp. la, 14a.-15a, infra.

Each of the propositions just set forth regarding

the legislative history is fully supported in the appen

dix. That history, taken together with the unequivocal

language of the statute, is sufficient to dispose of any

effort to read into § 1983 a distinction between pros

pective and retroactive remedies in actions against

public officials in their official capacities.

It would be sufficient to stop here, but for a compli

cation which results from certain statements made

about the legislative debates of 1871 in Monroe v. Pape,

supra, Monroe decided that the enacting Congress did

not mean to include municipalities within the term

“ persons” in § 1983. That conclusion was based not

on the legislative history of those portions of the bill

which Congress enacted into law—indeed, as we show

in the appendix, that legislative history clearly indi

cates the opposite—but on the history of an amendment

to that bill, the Sherman Amendment, which was even

tually defeated. 365 U.S. at 187-192. The Sherman

24

Amendment proposed to make counties, cities, and par

ishes liable in damages for private acts of violence oc

curring within their boundaries, without regard even

to whether those entities had been delegated any police

power by the state with which to deal with such vio

lence. See pp. 17a-19a, infra. The Monroe Court under

stood the defeat of that amendment to have resulted

from Congress ’ doubt as to its constitutional power to

“ impose civil liability on municipalities,” 363 U.S. at

190. In fact, this understanding is incorrect, as is ap

parent from two considerations:

First, Congress did not doubt its power to “ impose

civil liability on municipalities” in the circumstances

governed b y § 1983, i.e. where a municipality in the

exercise of powers delegated to it by the state violates

the prohibitions of Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Congress had voted for the Fourteenth Amend

ment in 1866, and as this Court has repeatedly recog

nized, it meant the prohibitions of Section 1 to apply

to local governmental bodies. Ex parte Virginia, 100

U.S. 339, 346-347 (1880) ; Home Telephone & Tele

graph Co. v. Los Angeles, 227 U.S. 278 (1913); Lovell

v. Griffin, 303 U.S. 444, 450 (1938). We demonstrate

Congress’ awareness of this power in the appendix.

See pp. 15a-16a, infra. We note here only that the 1871

Congress could not have forgotten what it had done

five years earlier, for Representative Bingham (whom

Justice Black called “ the Madison of the First section

of the Fourteenth Amendment” 24) reminded his col

leagues during the debate on § 1983 that in drafting

the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment he had

used the words “ No State shall . . . ” for the precise

purpose of overruling a Supreme Court decision hold-

Adamson v. California, 332 U.S. 46, 74 (1947) (dissenting

opinion). b

25

ing that a city’s taking of personal property without

compensation did not violate the Constitution as it then

stood.25 He went on to explain that he had copied these

words from the Impairment of Obligations of Con

tracts Clause.26 And in 1867, only four years prior to

the debate on § 1983, the Supreme Court had ruled that

the latter clause bound municipalities equally with

states, and affirmed a writ of mandamus compelling

municipal officers to levy taxes if necessary to honor

the contract sought to be impaired. Von Hoffman v.

City of Quincy, 71 U.S. 535, 554-555 (1867).

Second, an examination of the debates over the Sher

man Amendment reveals that while the Amendment

failed owing to a doubt concerning Congress’ power, it

was a doubt germane to the Sherman Amendment’s

unique provisions and wholly irrelevant to the mean

ing of § 1983. See pp. 17a-31a., infra. The Sherman

Amendment had nothing to do with requiring munici

palities to abide by the requirements of the Fourteenth

Amendment in exercising powers delegated by the

states; rather, it would have made municipalities affirm

atively responsible for preventing certain private acts

of violence from occurring within their boundaries.

Congress’ doubt went only to its constitutional power

to impose on local 'government bodies the affirmative

obligation to exercise the police power; it was this

doubt which led to the defeat of the Sherman Amend

ment. The Republican representatives who supported

the bill generally, but whose defection caused the

defeat of the Sherman Amendment, asserted that

20 Cong. Globe, 42 Cong., 1st Session, Appendix (hereinafter

“ Globe App.” ), p. 83-84.

2t' Globe App. 84.

26

it was the prerogative of the states to determine

whether and how to delegate the police power

function to local governments; that Congress could

not bypass the states and impose such functions

directly upon those governments; and consequently

that Congress lacked power to hold municipalities

monetarily liable for failing to exercise such power.

See pp. 21a-31a, infra. That constitutional doubt,

of course, warrants no inference that Congress intended

to insulate municipal treasuries in § 1983, for, unlike

the Sherman Amendment, § 1983 did not purport to

impose any affirmative obligations upon municipalities,

but only to enforce the prohibitions of the Four

teenth Amendment—“ no State 'shall . . —which

Congress knew applied to municipalities in their exer

cise of whatever powers the states chose to delegate to

them. We analyze the meaning of the defeat of the

Sherman Amendment more fully in the appendix.

We do not challenge here the holding of Monroe v.

Pape. Soundly based or not, the decision there that

municipalities are not “ persons” under § 1983, twice

relied upon in recent decisions,27 may well be entitled

to stare decisis effect. But neither stare decisis nor

any other doctrine compels this Court to perpetuate

Monroe’s erroneous reading of the legislative history

when, as here, distinct issues of statutory construction,

not controlled by the actual holding of Monroe, are

presented for decision. Congress did not intend to

“ protect municipal treasuries,” and there is thus no

warrant for limiting the remedies available in a § 1983

action against public officials in their official capacities.

27 Moor V. Comity of Alameda, 411 U.S. 693 (1973); City of

Kenosha v. Bruno, 412 U.S. 507 (1973). See also Aldinger v.

Howard, 427 U.S. 1,16 (1976).

27

II. SCHOOL BOARDS ARE "PERSONS" WITHIN THE

MEANING OF § 1983.

The court below decided that the Board of Educa

tion of the City of New York is not a “ person” within

the meaning of § 1983. The opinion is ambiguous as to

the ground upon which this decision is based. On the

one hand, the opinion indicates that due to institutional

characteristics peculiar to this board of education, it

should be considered a part of the City of New York,

and not an independent entity; therefore, the board

is not a “ person” because the city is not a “ person.”

Pet, A. 44-50. I f this be the court’s holding, it is not

of particular interest to these amici, whose concern is

with the “ person” status of those school boards which

are independent entities. We do note on this issue,

however, that contrary to the apparent conclusion of

the court below, the New York courts have consistently

ruled that the New York City Board of Education is

“ an independent corporation separate and distinct

from the city.” Lanza v. Wagner, 11 N.Y.2d 317, 326

(1962); People ex rel. Wells & Newton Co. v. Craig,

232 N.Y. 125, 135 (1922).

On the other hand, implicit in a portion of the court’s

analysis is a finding that no school boards, regardless

how constituted, are “ persons” within the meaning of

§ 1983. I f this be the court’s holding, we believe it to

be in error. In their typical form, local school boards

are distinct and independent governmental entities not

properly viewed as mere sub-parts of other govern

mental bodies. See Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S.

717, 741-743 (1974). As consistently as this Court

has treated other governmental entities as outside

the ambit of § 1983 and § 1343(3), so equally con

sistently (and in far greater volume) has this

2S

Court treated school boards as within the ambit of those

provisions. In case after case, particularly in the

school desegregation area, this Court has enter

tained § 1983 actions in which school boards were

defendants, without any indication that such boards

were not proper parties.28

Beyond merely entertaining these cases, the Court

has on a number of occasions issued orders against

school boards or directed or approved the issuance of

such orders. For example, in Green, supra, 391 U.S.

at 437-439, 441-442, a unanimous Court declared:

“ 13 years after Brown I I commanded the aboli

tion of dual systems we must measure the effec

tiveness of Respondent School Board’s ‘ freedom

of choice’ plan to achieve that end. The School

Board contends that it has fully discharged its

28 See, e.g., Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ;

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 663 (1963) ; Abington

School Dist. v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203 (1963); Griffin v. School

Board, 377 U.S. 218 (1963) ; Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S.

103 (1965) ; Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) ;

Raney v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 443 (1968) ; Monroe v!

Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450 (1968); Kramer v. Union

School District, 395 U.S. 621 (1969) ; Alexander v. Board of Edu

cation, 396 U.S. 19 (1969) ; Carter v. West Feliciana School Bd., 396

U.S. 226 (1969), 396 U.S. 290 (1970); Swann v. Board of Educa

tion, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ; Davis v. School Comm’rs of Mobile County,

402 U.S. 33 (1971); Northcross v. Memphis Board of Education,

412 U.S. 427 (1973) ; Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colo.,

413 U.S. 189 (1973) ; Cleveland Board of Education v. LaFleur,

414 U.S. 632 (1974) ; Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 416 U.S.

696 (1974) ; Goss v. Lopez, 419 U.S. 565, 568 (1975) ; East Carroll

Parish School Bd. v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976) ; Pasadena

City Bd. of Education v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424 (1976). Several

of these decisions encompassed two1 or more consolidated cases. In

addition to these full decisions, there of course has been an enor

mous number of per curiam decisions in school desegregation eases

against school boards.

29

obligation . . . Bnt that argument ignores the

thrust of Brown I I . . . School boards such as the

respondent . . . were . . . charged with the affirma

tive duty to take whatever steps might be necessary

to convert to a unitary system . . . [ I ] t was to this

end that Brown I I commanded school boards to

bend their efforts.

• • The burden on a school board today is to

come forward with a plan that promises realisti

cally to work, and promises realistically to work

now.

* * *

“ The New Kent School Board’s ‘ freedom-of-

choice’ plan cannot be accepted as a sufficient step

to ‘ effectuate a transition’ to a unitary system . . .

[T ] he plan has operated simply to burden children

and their parents with a responsibility which

Brown I I placed squarely on the School Board.

The Board must be required to formulate a new

plan and, in light of other courses which appear

open to the Board, such as zoning, fashion steps

which promise realistically to convert promptly to

a system without a ‘ white’ school and a ‘ Negro’

school, but just schools.” (emphasis in original;

footnote omitted).

To like effect, see, e.g., Carter, supra, 396 TJ.S. at 228;

Keyes, supra, 413 U.S. at 213-214; Monroe, supra, 391

U.S. at 458-459; Alexander, supra, 396 U.S. at 20;

Davis, supra, 402 U.S. at 35. See also Bradley, supra,

416 U.S. at 699, 718.

Congress has followed these decisions closely and has

assumed from these decisions, and acted upon the as

sumption, that school boards are subject to suit by

30

private parties. In 1964, 1972, and 1974, Congress en

acted into law statutes founded on that assumption.

In 1964, Congress augmented what it took to be an

existing right o f private parties to bring discrimina

tion actions against school boards by providing that,

under certain circumstances, the Attorney General may

bring such actions where he can certify that the ag

grieved private parties are as a practical matter un

able to bring their own suit. 42 U.S.C. § 2000c-6. Con

gress was careful to make clear that it did not intend

to “ affect adversely the right of any person to sue or

obtain relief in any court against discrimination in

public education.” 42 U.S.C. § 2000c-8.

In 1972, Congress passed extensive legislation in re

sponse to the school desegregation decisions of this

Court and the lower federal courts, again building on

the assumption that school boards are proper defend

ants in private actions to enforce constitutional rights.

The 1972 Congress passed, inter alia: (a) a provision

allowing attorney’s fees to the prevailing party, “ other

than the United States,” “ [ujpon entry of a final or

der by a court of the United States against a local edu

cational agency, . . . ” for violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment, 20 U.S.C. § 1617; and (b) a provision

authorizing federal financial assistance to “ local school

agenc[ies] ” which are implementing a desegregation

plan ‘ undertaken pursuant to a final order issued by

a court of the United States, . . . ,” 20 U.S.C. § 1605

(see also 20 U.S.C. § 1601). Once again, Congress

recognized the “ existing power” of federal courts “ to

insure compliance with constitutional standards” in

school desegregation actions, 20 U.S.C. § 1656, and

sought only to prohibit “ enlargement” of that power,

id.

31

In 1974, Congress found, inter alia, that as a result

of court busing orders in suits brought to enforce the

Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, “ local educational

agencies” had been required to “ expend large amounts

of funds, thereby depleting their financial resources.

. . 20 U.S.C. § 1702(a)(3). That finding did not

motivate Congress to withdraw federal jurisdiction

over suits against “ local educational agencies.”

Rather, Congress in 1974 sought to set remedial pri

orities in such suits, so that busing would be a remedy

of last resort. See particularly, 20 U.S.C. § 1713. Far

from removing jurisdiction, Congress made clear that

“ the provisions of this chapter are not intended to

modify or diminish the authority of the courts of the

United States to enforce fully the fifth and fourteenth

amendments to the Constitution of the United States.”

20 U.S.C. § 1702(b).

From time to time bills have been introduced in

Congress designed to withdraw or limit federal court

jurisdiction to entertain suits against school boards.29

No such bill has been enacted. Other bills have been

introduced which proposed to limit the remedies avail

able in school desegregation suits, drafted in a fashion

In the first session of the 93rd Cong., for example, the follow

ing bills were introduced in the Senate: S. 179 (Jan. 4, 1973), a

bill̂ introduced by Senator Griffin to deprive federal courts of

jurisdiction to issue busing orders; S. 287 (Jan. 11, 1973), a bill

introduced by Senator Scott to withdraw all lower federal court

jurisdiction over eases “ involving the public schools” ; S. 1737

(May 8, 1973), a bill introduced by Senators Ervin and Allen

which, in Sec. 1207, would withdraw federal court jurisdiction,

mter aha, to “ issue any order requiring any school board” to

abandon a freedom-of-choice plan, or “ requiring any school board”

to bus, or “ requiring any school board” to close any school.

32

which clearly reflects the sponsors’ belief that school

boards are presently proper defendants in such suits.30

For over twenty years, and in more than that many

cases, this Court has treated school boards as “ per

sons” subject to suit pursuant to § 1983 and § 1343(3).

Congress has understood this Court so to have ruled,

and has after careful consideration accepted, indeed

built upon, that understanding. In the light of this

history, the question whether school boards are “ per

sons” under § 1983 must be regarded as settled in the

affirmative. See Brown Shoe Co. v. United, States,

supra, 370 U.S., at 306-307; Flood v. Kuhn, supra, 407

U.S., at 282-284.

30 See, e.g., S. 619, 93d Cong., 1st Sess. (Jan. 31, 1973), a bill

sponsored by Senators Allen, Baker, Buckley, Helms, Nunn, Scott,

Sparkman, Stennis, Talmadge, and Thurmond, which provided in

Sec. 207:

Sec. 207. Any court, order requiring the desegregation of a

school system shall be terminated, if the court finds the schools

of the defendant educational agency are a unitary school sys-

tem, one within which no person is to be effectively excluded

from any school because of race, color, or national origin,

and this shall be so, whether or not such school system was

in the past segregated de jure or de facto. No additional order

shall he entered against such agency for such purpose unless

the schools of such agency are no longer a unitary school sys

tem.” (emphasis added).

33

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth hereinabove, the decision

below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

A lbert E. J e n n e r , J r .

Lawyers’ Committee

for Civil Rights

Under Law

R obert A . M u r p h y

W il l ia m E. C a l d w e l l

733 Fifteenth St., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

M ic h a e l I I . G o tte sm a n

R obert M . W ein berg

B r e d h o ff , C u s h m a n ,

G o t t e s m a n & C o h e n

1000 Connecticut Ave.,

N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

D avid R u b in

National Education

Association

1201 Sixteenth Street,

N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

APPENDIX

l a

APPENDIX *

An. Analysis of the Legislative History of the Civil Rights Act

of 1871 as It Relates to the Issues Presented in This Case

I.

We begin by briefly describing the course of the legisla

tion which emerged as the Civil Eights Act of 1871, noting

the particular features which bear directly upon the issues

in this case. We then discuss the pertinent legislative his

tory in depth.

The legislative history properly begins on February 25,

1871, one month before the civil rights bill was introduced.

On that day, the “ dictionary act” was enacted, providing,

in pertinent part :

“ That in all Acts hereafter passed . . . the w ord ‘ p e r

s o n ’ m ay ex ten d and he applied to bod ies p o litic and,

co rp o ra te , and the reference to any officer shall include

any person authorized by law to perform the duties of

such office, u n less the co n tex t sh ow s that such w ords

w ere in ten d ed to he used, in a m ore lim ited sen se . . . . ” 1

On March 28, 1871, the House Select Committee reported

H.R. 320, a bill “ to enforce the provisions of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and

for other purposes, ’ ’ which, with such modifications as were

made in the ensuing debates, emerged as the Civil Eights

Act of 1871.2

The bill contained four sections. Section 1— now

codified in 42 TJ.S.C. § 1983—was enacted by Congress in

* Throughout this Appendix, “ Globe” is used to refer to the

Congressional Globe, 42d Cong., 1st Sess., and “ Globe App.” is

used to refer to the Appendix thereto.

1 Aet of Feb. 25, 1871, eh. 71, § 2, 16 Stat. 431 (emphasis added).

2 Globe 317.

2a

the form originally reported, without a single word change.

It provided:

“ That any person who, under color of any law, statute,

ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage of any State,

shall subject, or cause to be subjected, any person with

in the jurisdiction of the United States to the depriva

tion of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by

the Constitution of the United States, shall, any such

law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage of

the State to the contrary notwithstanding, be liable to

the party injured in any action at law, suit in equity,

or other proper proceeding for redress; such proceed

ing to be prosecuted in the several district or circuit

courts of the United States, with and subject to the

same rights of appeal, review upon error, and other

remedies provided in like cases in such courts, under

the provisions of the act of the 9th of April, 1866, en

titled ‘An act to protect all persons in the United States

in their civil rights, and to furnish the means of their

vindication, ’ and the other remedial laws of the United

States which are in their nature applicable in such

cases.” 3

Section 2 of the bill, as introduced, defined certain federal