Franks v. Bowman Transportation Company Brief for Respondent as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Franks v. Bowman Transportation Company Brief for Respondent as Amicus Curiae, 1974. eb25c25f-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b4e671dd-edbe-41ad-9a2d-b9a7b80e2de0/franks-v-bowman-transportation-company-brief-for-respondent-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

/ T>lJEr

No. 74-72?■ •■»».'' 'itti'ff-via.vK

l \T r; ■ y< i ■>1 :.\ 1 fi la

V. OXX

liC’jiK’E'C C. M .■■ i';;k

7x6 i'iOY.Vlt .!■ jjt'i

-,v -1 r • v j e r • , -yr \rr!., i\ . \ \ .

W.-isliiii.L' if n. D . C . 0 .3

■\ >T) FOi>

, !• ijDE-UATlOX OF LABOK a a n

A *1 '• r V TAT' G.<rp'J * , t

j OKG * aI/'/i r{ [ (* s

A f’ \ A H ( <? I C m .a ) ill'! lAH.'O V. v'■ T> T ‘ T .. xvA i\ i i

MlCH.YKl. 1J. GottkA A LAX',

E i .l t o t B n i ' n i i o i ' p ,

I tOB EKT 7 ' . W e : N V.KRG .

IGr-C* Co)iiK;f!i i'.Mjt .'w e., X.W.

Wasliitietoji, D.C. 20030

i.iA"!:F.XIt*!* •*

■Sii> "'txi!'••*;*ii »St 10('i, XAV.

\ V til-! ' ! 1 i ; v * Nr] ' . i iiO.Ot)

AtiovnevK for AFB-CIQ

Bkkx\j:r> i 7 n,

(Bw,F i!A.nk):l,

Five Gateway Cenier

Pitt rdi, Pa. 15222

.1 !a:i'MI- .\ . CV,i'I’Ki;.

J u ' H X C . FALKKXttKM SV.

1011 Forth 21 - t Hi roct

Birnuauhnn. Ala. 55200

.! a.\i i'.a AY. Don SKY.

100 Peachtree St rear, X.W

Atlanta. Genruia OOhOO

A ttorneys 1 ej* ! SWA

'Z’n p r m s

/■ft - £A* ft-ITT j lv :*■ tp P f r P

v * October Terw, 1S7>

ll.w.onn F*.; \ x !■; . ■ ,Jm;

V. -

'au.- Bow m -,x j ys t̂ oiTATfOA■: OoMVAXT , 1> O., <;/ ol.

1 On VViM'i .>:■■ ( 'Xl! : loe.Alil •} . 1 XI ■ E l i A T O

1 (A)* '*:'' <>K AvPJlAi i J-’OKT'.1: F ifth? CikcuS !•

1 l : ,S 1 t \ 1) .!'.

BK {EF

:! ’ f >: t t g ! >

FOP

s'i’KKLWOTiK EPS OF

,v 1 ca , AP’L-CIO.

!

♦

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ADDITIONAL STATUTORY PROVISION

INVOLVED .................................................................

COUNTER-STATEMENT OF T1IE CASE ........ .

ARGUMENT...............................................................

Introduction and Summary ....................................

I. The “ Rightful Place” Remedy Sought by Peti

tioners Is Called For By The Congressional

Scheme ...............................................................

A. The Congressional Policies Which Bear

Upon The Fashioning Of “ Seniority”

Remedies Under Title V I I ...........................

B. The Relief Sought By Petitioners Is Fully

Consistent With, And Effectuates, The Con

gressional Objectives ....................................

C. The “ Last In, First Out” Layoff Cases,

And The Implications Of The Congressional

Determination To Preclude Preferential

Treatment......................................................

II. This Case Should Not Be Decided On The Basis

Of 42 U.S.C. § 1981.............................................

CONCLUSION ............................................................

Page

3

OO

6

6

24

29

33

36

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Adickes v. S.II. Kress and Co., 398 U.S. 144 (1970) 33

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 43 LAV. 4880 (June

25, 1975) ................................................ 8-9, 23, 26, 27-28

Atlantic Maintenance Co., 134 NLRB 132S (1961),

enforced 305 F.2d 604 (3rd Cir. 1962) ................... 27

Bing v. Roadway Express, Inc., 4S5 F.2d 441 (5th

: Cir. 1973) ........................................................... 28-29, 32

Page

Boive v. Colgate Palmolive Co., 489 F.2d 896 (7th

Cir. 1973) ................................................................. 29

Consolidated Dairy Products, 194 NLRB 701 (1971) 27

Cox v. Allied. Chemical Corp., 392 F. Supp. 309 (M.T).

La. 1974) ................................................................... 32

Delay v. Carling Brewing Co., 10 FEP Cases 164

(N.D. Ga. 1974) ............ 32

EEOC v. Detroit Edison Co., 10 FEP Cases, 239 (6th

Cir. 1975) ................................................................. 29

First National Bank of Chicago v. United Airlines,

342 U.S. 396 (1952) ............. 6

Great Lakes Dredge £ Dock Co., 169 NLRB 631

(1968) ....................................................................... 27

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424

(1971) .................................................... 2-3, 20, 22, 35-36

Hughes Corporation, 135 NLRB 1222 (1962) .......... 27

Jersey Power Central £ Light Co. v. International

Blid. of Electrical I Yorkers, 508 F.2d 687 (3rd Cir.

1975) ............................................................ 31-32

Johnson v. Bailway Express Agency, Inc., 43 L."\V.

4623 (May 19, 1975) .............. 34

Lamar Creamery Co., 115 NLRB 1113 (1956), en

forced 246 F.2d 8 (5th Cir. 1957) ............................. 27

Long v. Ford Motor Co., 496 F.2d 500 (6th Cir. 1974) 35-36

Loy v. City of Cleveland, 8 FEP Cases 614 (N.D.

Ohio, 1974) ............................ 32

Nevada Consolidated Copper Corp., 26 NLRB 1182

(1940), enforced 316 U.S. 105 (1942) ..................... 27

Pacific American Shipowners Association, 98 NLRB

582 (1952) ............................................... 27

Phelps Dodge Corp., 19 NLRB 547 (1940), enforced

313 U.S. 177 (1941) .................................................. 26-27

Pipefitters v. United States, 407 U.S. 385 (1972) .... 21

Porter Co. v. NLRB, 394 U.S. 99 (1970) ................... 22-23

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D.

Va. 1968).............................................. 32

ii

Robinson v. Lorillard Carp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir

1971) ....................................................................‘

Rodriguez v. East Texas Motor Freight, 505 F 2d 40

(5th Cir. 1974) ....................................

29

32-33

Page

Schaefer v. Tannian, 10 FEP Cases 897 (E.D Mich

1975) .......................................... ........................... '

Thornton v. East Texas Motor Freight, 497 F 2d 416

(6th Cir. 1974) ..................................’...........'

U.S. v. Allegheny Ludlum Industries, 8 FEP Cases

198, 63 FED 1 (N.D. Ala., 1974) .......................... .

IJ.S. v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652 (2d Cir

1971) .......................................................... .

b.S. v. Local 189, United Papermakers, 416 F.2d 980

(5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970)

U.S. v. N.L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354 (8th Cir

1973) ...................................................... '

U.S. v. United States Steel Corp., 371 F. Surra 104-5

(N.D. Ala. 1973) ................................

32

29, 32

3

29

32

29

oO

Waters v. Wisconsin■ Steel Works, 502 F.2d 1309 (7th

Cir. 1974) petitions for certiorari pending, Nos. 74-

1064, 74-1350 ............................................... 7-8, 31-32, 34

Watkins v. United Steelivorkers of America 369 F

Supp. 1221 (E.D. La. 1973), pending on appeal to

1* ifth Circuit as Fo. 74-2604 .................... gp gg

W. 11. W. Services, Inc., 190 NLRB 499 (1971) ........

Whitfield v. United Steelworkers, 263 F 2d 546 (5th

Cir. 1959) .................................

Statutes

Civil Rights Act of 1866:

Section 1, 42 U.S.C. § 1981..................

Section 3, 42 U.S.C. § 1.988 ..................

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII:

Section 703(a), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(a)

Section 703(c), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(c)

33-35

34-35

. . . . 10, 20

10-11, 20

m

Section 703(h), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h) .. 9, 18-23, 31, 33

Section 703(;j), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(j) .......... 3, 18-21, 31

Section 706(g), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g) .......... 8-11, 20-23

National Labor Relations Act:

Section 8(d), 29 U.S.C. § 158(d) ............................ 22-23

Section 10(c), 29 U.S.C. $ 160(c) ....................... 22-23, 26

Arbitration Decisions

Amoco Oil Co., 61 LA 10 (Bernard Cushman, 1973) 26

BASF Wyandotte- Carp., 63 LA 121 (Elliot Beitner,

1974) ........................................................................ 26

Inland Lumber Co., 62 LA 1151 (Henry C. Wilmoth,

1974) ......................................................................... 26

Jordanos Markets, Inc., 63 LA 345 (Marshall Ross,

1974) ........................................................................ 26

North American Rockwell Corp., 62 LA 901 (Martin

E. Conway, 1974) .................................................... 26

P.M. Northwest Co., 42 LA 961 (Daniel Lyons, 1964) 26

Legislative Materials

EEOC, Legislative History of Titles VII and XI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ................................ 2, 12-21

Rustic, The Blacks and the Unions, Harper’s Maga

zine, May 1971, pp. 73, 76

Page

2

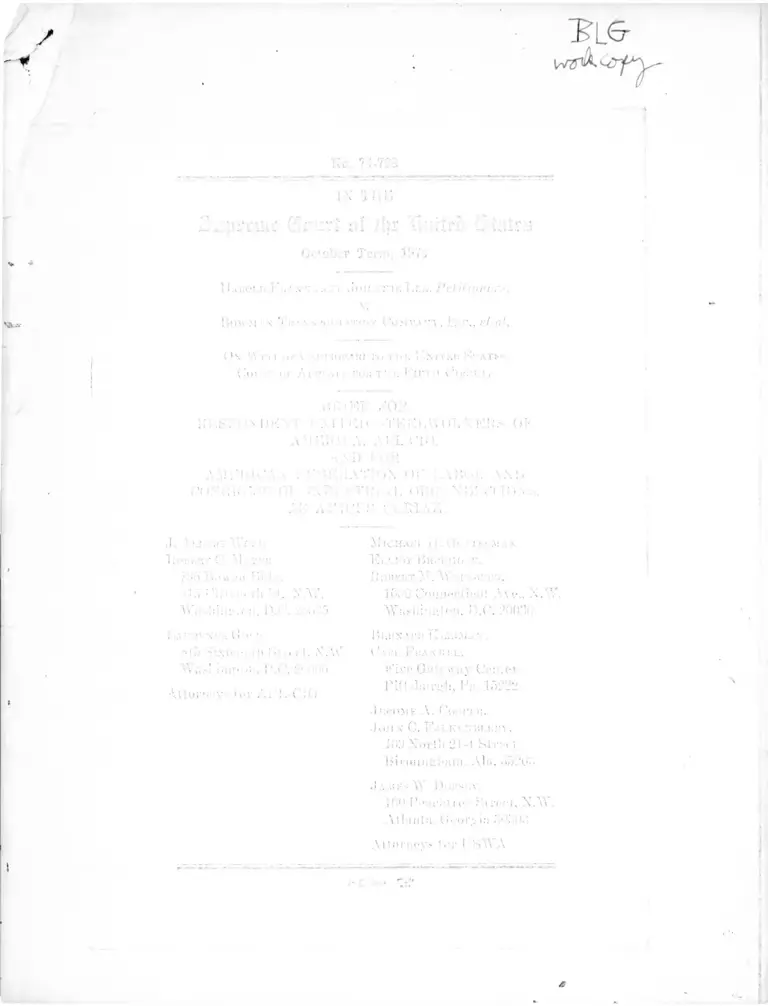

IN THE

g 'n ^ r r u tf ( t a r t n f lb? U n ite d 0 t a t e

October Term, 1074

No. 74-728

H arold F ranks and J o h n n ie L e e , Petitioners,

v.

B owman T ransportation C ompany , I n c ., et al.

O n W rit of Certiorari to t h e U n ited S tates

C ourt of A ppea ls for t h e F if t h C ircuit

BRIEF FOR

RESPONDENT UNITED STEELWORKERS OF

AMERICA, AFL-CIO,

AND FOR

AMERICAN FEDERATION OF LABOR AND

CONGRESS OF INDUSTRIAL ORGANIZATIONS,

AS AMICUS CURIAE

Tliis brief is filed jointly by respondent United Steel

workers of America, AFL-CIO (hereinafter referred to as

“ USWA” ), and by American Federation of Labor and

Congress of Industrial Organizations, as amicus curiae

(hereinafter referred to as “ AFL-CIO” )-1

USWA, which is the AFL-CIO’s largest affiliate, is the

collective bargaining representative of the employees of

respondent Bowman Transportation Company (hereinafter

“ the Company” ). AFL-CIO is a federation of 111 labor

1USWA and AFL-CIO tile this statement of their common posi

tion in a single brief for the convenience of the Court. All parties

have furnished written consent to AFL-CIO to file an amicus

curiae brief.

2

organizations, with a combined membership of 14 million

Both AFL-CIO and USWA actively supported the en

actment of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Presi

dent Mean}', testifying in support of its passage, declared:

"The leadership of the AFL-CIO, and of the separate

federations before merger, has been working ceaselessly

to eliminate those prejudices. The leaders of every

affiliated national and international union are enlisted

in the same effort. We have come a long way in the

last 20 years—a long way farther, I might sav, than

any comparable organization, including'the religious

organizations as a whole, and certainly we are a gener

ation or more ahead of the employers as a whole.

"But we have said repeatedly that to finish the job

we need the help of the TI.S. Government. * * * When

the rank-and-file membership of a local union obsti

nately exercises its right to be wrong, there is very

little we in the leadership can do about it, unaided. * * *

In shoit, I am not here to ask for special exemp

tions for unions; quite the contrary. I hope the law you

draft will cover the whole range we ourselves have

written into our constitution and we hope you will make

sure that the law will also apply to apprenticeship pro

grams of every kind, as I urged this very committee

last August.” 2

Both USWA and AFL-CIO have labored diligently to bring

employment practices throughout American industry into

compliance with Title VII, and to secure judicial interpre

tations which effectuate Title V Il’s statutory objectives.3

2 EEOC, Legislative History of Titles VIT and XI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 [hereinafter “ Leg. Hist,” ] pp. 2158-59. The

President of USWA had likewise testified in support of enactment

of Title VII. Id, 3242. See also Bayard Rustin, the Blacks and the

Unions, Harper’s Magazine, May, 1971, pp. 73 76

3 For example, USWA filed a brief amicus curiae in Griacis v.

Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, urging the statutory interpretation

A

3

ADDITIONAL STATUTORY PROVISION INVOLVED

We believe that another provision of Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, not reproduced in the brief for

petitioners, is important to the analysis of this case. Section

703(j), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(j) provides:

“ (j) Nothing contained in this title shall be inter

preted to require any employer, employment agency,

labor organization, or joint labor-management commit

tee subject to this title to grant preferential treatment

to any individual or to any group because of the race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin of such individ

ual or group on account of an imbalance which may

exist with respect to the total number or percentage of

persons of any race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin employed by any employer, referred or classi

fied for employment by any employment agency or

labor organization, admitted to membership or classi

fied by any labor organization, or admifted to, or em

ployed in, any apprenticeship or other training

program, in comparison with the total number or per

centage of persons of such race, color, religion, sex,

or national origin in any community, State, section, or

other area, or in the available work force in any com

munity, State, section, or other area.”

COUNTER-STATEMENT CF THE CASE

We accept petitioners’ statement of the case, but believe

which this Court adopted, and TJSWA initiated the negotiations

leading to the industry-wide decree bringing employment practices

in the steel industry into compliance with recent judicial interpre

tations of Title VII. See U.S. v. Allegheny Ludl.um Industries, 8

PEP Cases 198, G3 F.R.D. 1 (N.D. Ala., 1974). USWA’s role in

integrating the two largest southern steel plants, prior to passage

of Title VII, is recounted in U.S. v. United States Steel Carp., 371

P. Supp. 104”), 1055 and particularly n. 23 thereat, 1000 n. 39,

1062 (N.D. Ala. 1973), and Whitfield v. United Steelworkers, 263

F.2d 546 (5th Cir. 1959).

4

the Court should have additional information respecting

the role of the Union.

Until 1967, the Company’s employees were unorganized.

International Union of District 50 (hereinafter “ District

50” ) had sought to organize the employees previously, hut

had been rejected in an NLRB-conducted election (43a).

The employment conditions which prevailed during this

non-union period were aptly described in the decision of

the court below: the Company had “followed a conscious

policy of keeping its employees segregated according to

race,” had “ prohibited inter-departmental transfers flat

ly,” and had discriminated against some blacks in hiring,

495 F.2d at 409-411.*

In 1967, District 50 succeeded in organizing the em

ployees, was recognized by the Company as their bargain

ing representative, and commenced negotiations with the

Company for a first collective bargaining agreement (43a).

In accordance with its long-standing policy that “ company

wide seniority is the only true seniority,” District 50 pro

posed that the Company convert its seniority system from

departmental seniority to company-wide seniority, that all

job vacancies be posted, that transfers be allowed on the

basis of plant seniority, and that the Company henceforth

assign newly-hired employees to all departments “ without

regard to race” (44a; 495 F.2d at 410-411). The Company

agreed to abolish its no-transfer policy, and to assign new

employees without regard to race. (495 F.2d at 410-411).

The Company refused, however, to substitute company-

wide seniority for departmental seniority, or to post notices

of job vacancies (44a-45a). District 50, convinced that it

4 The Company was willing to hire blacks who would accept

assignment to the historically “ black” jobs, but refused to hire

those whose sole interest was in “ white” jobs. Id. at 411.

,.W*U*1. ‘taf <ii»̂n.rv,,

5

could not conduct a successful strike, acquiesced in an

agreement which preserved the departmental seniority sys

tem and did not provide for posting of job vacancies (44a;

4!!5 F.2d at 410-411).

The 1967 agreement provided for a reopener, without the

right to strike, in 1968. In the negotiations pursuant to

that reopener, District 50 again demanded company-wide

seniority and posting (45a). This time, the Company agreed

to the posting of job vacancies, but it again refused to

convert to company-wide seniority (45a).

The Company had exclusive authority in determining

who would be hired (45a). The Company continued to dis

criminate against blacks in hiring until 1972. 495 F.2d at

411.

In 1912, District 50 merged with USWA, Accordingly,

USWA has succeeded District 50 as the employee’s bar

gaining representative, and as the union-respondent in this

case.

This suit sought relief for two groups of workers: blacks

who were hired when they first applied but who were as

signed discriminatorily to jobs in the Company’s less de

sirable departments, and blacks who were discriminatorily

denied employment altogether when they first applied.

The decision of the court below granted the first group—

those discriminatorily assigned—all of the relief they

sought, The court held that these employees were entitled

not only to back pay, but also to the right which District 50

had sought unsuccessfully in negotiations: to transfer to

other departments with “ the use of full company seniority

for transfer purposes . . . and for all purposes after trans

fer in the new department” (495 F.2d at 416). The Com

pany’s petition for certiorari from this portion of the

\

6

decision below was denied, 43 L.W. 3330 (1974).

idle decision below did not, however, fully cure the ms-

crimination visited upon those who had initially been re

jected for employment solely because of their race. While

the decision accorded these employees back pay tor the

period during which employment had been discriminator]'ly

withheld, it denied their request that they be awarded the

earlier seniority dates which they would have enjoyed ab

sent discrimination. Id. at 417-418. We agree with petition

ers, and demonstrate herein, that the court below erred in

not granting the seniority relief requested.

ARGUMENT

Introduction and Summary

It is often said that hard cases make bad law. But easy

cases can also make bad law, if the apparent correctness of

a particular result deflects attention from the importance

of the path by which that result is reached. Mr. Justice

Jackson once made the point with characteristic grace in a

concurring opinion:

“ I part company with the Court as to the road we will

travel to reach a destination where all agree we will

stop, at least for the night. But sometimes the path

that we are beating out by our travel is more impor

tant to tlie future wayfarer than the place in which we

choose to lodge.” 5

We agree with petitioners that they are entitled to the

seniority relief which they seek. We believe, however, that

petitioners have arrived at the correct result through an

analysis of Title VII which is incomplete, in that it does

not focus upon the basic objectives which guided Congress

in structuring that statute.

5 First National Bank of Chicago v. United Airlines, 342 U.S.

396, 398 (1952).

—t-'

7

As we will develop herein, Congress had two very clear

objectives: (1) to forbid discrimination and to make whole

those who suffered discrimination; (2) not to confer pref

erential rights upon minorities, either in the substantive or

remedial provisions of the Act.

In our view, these two objectives lead to a dichotomy be-

tueen make whole” remedies, which fully implement the

Congressional design, and “ preferential” remedies, which

Congress clearly intended to forbid. In the seniority con

text, there are two types of remedies which would be

preferential” : (1) conferring enhanced

individuals who are not discriminatees, i.e.

seniority upon

, who have not

been denied employment or perquisites of employment by

the defendants on account of race, creed, color, sex or na

tional origin; and (2) conferring seniority rights upon dis-

criminatees beyond those necessary to place them in the

positions they would be occupying had there been no dis

crimination.

Petitioners are entitled to the relief they seek because

that relief is “ make whole,” not “ preferential.” Were this

Court to reverse the decision below, however, without rec

ognizing the cutting line” drawn by Congress, its opinion

might suggest that other cases be decided in a manner in

consistent with the Congressional!y intended scheme. This

concern is not hypothetical, for there is already on this

Court’s docket a case {Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works,

No. 74-1064, petition for certiorari pending) in which a

“ Preferential” remedy is sought, but which counsel for the

If atos petitioners (who are also counsel for petitioners

here) assert poses “ the same” issue n substance as that

in the instant case.6

0 Reply Brief in Support of Certiorari in Waters, p. 1. The perti-

We begin by analyzing the relevant legislative materials

and showing that they demonstrate that the dichotomy just

noted is an accurate distillation of the Congressional intent

We then draw the lessons which Title VII, read against the

background of its history, provides for this ease, and for

cases such as Waters.

I. The “Rightful Place" Remedy Sought By Petitioners Is

Called for By the Congressional Scheme

A. T h r C ongressional P olicies w h ic h B ear U pon t h e

F ash ion in g op “ S e n io r it y ” R em edies u nder T itle VII

The basic principles governing the fashioning of relief

for Title VII violations were articulated by this Court in

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 43 L.W. 4880 (June 25,

1975). Albemarle involved the remedy of back pay, but the

sentence of § 706(g) which the Court there construed au

thorizes back pay and other equitable relief in the same

terms.7 As this Court made clear in Albemarle, the discre

tion vested in district courts by § 706(g) must be exer

nent paragraph, in full, states:

“ As respondents properly recognize, the certworthiness of

Questions 1 and 2 involves the relationship of the Seventh

Circuit decision in the instant case to the Fifth Circuit deci

sion in Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398

(5th Cir., 1974), cert, granted 43 U.S.L.W. 3515 (1975), No.

74-728. Both the Fifth and Seventh Circuits held that “ last

hired, first fired" seniority systems were immune per se from

legal attack. The Fifth Circuit reached this result by holding

that it lacked the power to give an aggrieved employee the

necessary relief, seniority retreadive to the dale on which he

was denied a job because of his race. The Seventh Circuit

reached this result by holding that such a seniority system

was, as a matter of law, non-discriminatory. The substance of

the Fifth and Seventh Circuit rules is of course the same "

7 Section 706(g), first sentence, provides:

“ If the court finds that the respondent has intentionally

9

cised consistently with “ the purposes which inform Title

V II” (43 L.W. at 4883-84). The essential first step in re

solving this case is, therefore, to identify those Congres

sional objectives which bear upon the formulation of “ sen

iority” remedies.

The court , below held that § 703(h) precludes award

ing- seniority to a discriminatee for any period prior to

his actual date of hire. Respectfully, we submit that be

cause the court below failed to focus on the broad design

of Title VII, it construed that one section out of context

and imported to it a meaning quite different from that in

tended by Congress. As we show, the central concern which

preoccupied Congress in drafting Title VII was to be sure

that it had made sufficiently plain the line between abolish

ing- discrimination, which was its goal, and providing pref

erential treatment, which all members wished to preclude.

The debate on the floor of Congress was not over whether

that line should be drawn—everyone agreed that it should

—but over what language was necessary to make that line

unmistakably clear. Section 703(h) is but one of several

provisions added to confirm this Congressional purpose.

Properly construed, it precludes only “ preferential”

treatment. It does not preclude any remedy which—as we

later show is involved here—merely accords a proven vic-

engaged in or is intentionally engaging in an unlawful em

ployment practice charged in the complaint, the court may

enjoin the respondent from engaging in such unlawful em

ployment practice, and order such affirmative action as may

be appropriate, which may include, but is not limited to, re

instatement or hiring of employees, with or without back pay

(payable by the employer, employment agency, or labor orga

nization, as the case may be, responsible for the unlawful

employment practice), or any other equitable relief as the

court deems appropriate.”

30

tim of discrimination his “ rightful place” : the place in

the seniority system which he would be occupying but for

the prior discrimination against him.

The drafters of the original bill which eventuated in

Title VII sought to make explicit that remedies would be

available only to those who established that they were vic

tims of discrimination. The basic liability provisions,

§§ 703(a), (c), speak of discrimination “against any indi

vidual,” and the key remedial provision, § 700(g), states

m its last sentence that courts may not furnish remedies

to an individual” unless he has proven that he has suf

fered employment disadvantage “ on account of race, color,

religion, sex or national origin.” 7* The drafters believed * 1

7‘ Section 703(a) provides:

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an em

ployer—

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individ-

dual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual

with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privi

leges of employment, because of such individual’s race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin; or

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or ap

plicants for employment in any way which would deprive

or tend to deprive any individual of employment opportuni

ties or otherwise adversely affect his status as an employee

because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex' or

national origin.

Section 703(c) provides:

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for a labor

organization—-

(1) to exclude or to expel from its membership or other

wise to discriminate against, any individual because of his

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin ;

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify its membership or

applicants for membership or to classify or fail or refuse

11

that these provisions, standing alone, made clear the dual

Congressional objectives: on the one hand, to forbid dis

crimination and make discriminatees whole; on the other,

to preclude preferential treatment of minorities qua mi

norities. As Senators Clark and Case, the floor managers of

Title VII in the Senate, explained:

No court order can require hiring, reinstatement,

admission to membership, or payment of back pay for

anyone who was not discriminated against in violation

of this title. This is stated expressly in the last sen

tence of section 707(e) [enacted as 706(g)] which

makes clear what is implicit throughout the whole

title; that employers may hire and lire, promote and

refuse to promote for any reason, good or bad, pro

vided only that individuals may not be discriminated

against because of race, color, religion, sex or national

origin. ’ ’

* * * * * 3

to refer for employment any individual, in any way which

would deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employ

ment opportunities, or would limit such employment oppor

tunities or otherwise adversely affect his status as an em

ployee or as an applicant for employment, because of such

individual s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin; or

(3) to cause or attempt to cause an employer to discrimi

nate against an individual in violation of this section.

The last sentence of Section 700(g) provides:

No order of the court shall require the admission or rein

statement of an individual as a member of a union, or the hir-

ing, reinstatement, or promotion of an individual as an em

ployee, or the payment to him of any back pay, if such

individual was refused admission, suspended, or expelled, or

was refused employment or advancement or was suspended or

discharged for any reason other than discrimination on ac

count of race, color, religion, sex. or national origin or in vio

lation of section 704(a). [Section 704(a) forbids retaliation

against employees for asserting their rights under Title V llj.

12

“ There is no requirement in title VII that an em

ployer maintain a racial balance in his work force.

It must be emphasized that discrimination is

prohibited as to any individual. While the presence or

absence of other members of the same minority group

in the work force may be a relevant factor in deter

mining whether in a given case a decision to hire or

to refuse to hire was based on race, color, etc., it is

only" one factor, and the question in each case would be

whether that individual was discriminated against.” 8

:

But notwithstanding the clarity of the bill’s original lan

guage, there developed a national tide of concern that Title

VII would confer preferential rights upon minorities at

the expense of the majority. Two basic fears were voiced

again and again: that Title VII would force employers to

hite minorities pursuant to quotas in order to achieve

racial balance, and that minorities when hired would be

given special seniority rights boosting them ahead of in

cumbent whites.

The alarums were first sounded in the Minority Report

accompanying the House Judiciary Committee’s Report

recommending adoption of Title VII. The minority mem

bers asserted that the bill “ under the cloak of protecting

the civil rights of certain minorities, will destroy civil

rights of all citizens of the United States who fall within

its scope.” 9 They listed a number of interests which would

be “ seriously impaired] by the passage of the bill.” 10 11

Among these were the “ seniority rights of employees in

corporate and other employment.” 11 They warned that

i

8 Leg. Hist. 3044, 3040.

9 Leg. Hist. 2064.

10 Ibid.

11 Id., 2065.

13

Title VII “ would destroy seniority.” 12 They asserted that

the bill’s “ true interest and purpose” was to achieve racial

balance, not merely to end discrimination.13 Dramatizing

the threat to seniority which they perceived, the minority

members declared:

“The provisions of this act grant the power to de

stroy anion seniority. The action of the Secretary of

Labor already mentioned is merely the beginning, if

this legislation is adopted. With the full statutory

powers granted by this bill, the extent of actions which

would- he taken to destroy the seniority system is un

known and unknowable.

“ To disturb this traditional practice is to destroy a

vital part of unionism. Under the power granted in

this bill, if a carpenters’ hiring hall, say, had 20 men

awaiting call, the first 10 in seniority being white car

penters, the union could be forced to pass them over

in favor of carpenters beneath them in seniority, but

of the stipulated race. And if the union roster did not

contain the names of the carpenters of the race needed

to ‘racially balance’ the job, the union agent must then

go into the street and recruit members of the stipulated

race in sufficient number to comply with Federal or

ders, else his local could be held in violation of Federal

law.

“ Neither competence nor experience is the key for

employment under this bill. Race is the principal, first,

criterion. ’ ’14

These accusations prompted a number of the bill’s spon

sors in the House to submit a statement of “ additional

views,” in which they sought to allay the fears which the

minority members had voiced:

12 Id., 2066.

13 Id., 20G7-68.

u Id. 2071 (emphasis in original).

14

I t must also be stressed that the Commission must

confine its activities to correcting abuse, not promoting

equality with mathematical certainty. In this regard

nothing in the title permits a person to demand em-

pioyment. Of greater importance, the Commission will

only jeopardize its continued existence if it seeks to

impose forced racial balance upon employers or labor

nnions. Similarly, management prerogatives, and un

ion freedoms are to be left undisturbed to the greatest

extent possible. Internal affairs of employers and labor

organizations must not be interfered with except to the

muted extent that correction is required in discrimina

tion practices. Its primary task is to make certain that

the channels of employment are open to persons re-

gaidless of their race and that jobs in companies or

membership m unions are strictly filled on the basis of

qualification.” 15

The sponsors’ reassurances proved sufficient in the

House, which passed the bill without material change. But

m the Senate a. filibuster began on March 9, 1964 and con

tinued for more than three months.16 That filibuster fed on

the fear that Title VII was intended “ to rob all Americans

°f 'mi>° ^ T l nghtS f°r tb° W f i t 0f a of the pop-

11 a ion. The emotional climate was accurately depicted

y enatoi Clark, one of the floor managers of Title VII-

“ There lias been so much oratory, and so many

what'TitleVTT^r1' r r ntS haVG 1)0011 mado aboutohh r VU does< ^ a t it is perhaps difficult to speak

bjectively and carefully about what the title is in-

enc ed to do, without being diverted into an effort to

rebut some of what can only be called fantastic mis-

statemente about what the title does, which have been

made fr0m 111110 10 time> not only on the floor of the

15 Id. 2150.

10 Id. 3092.

15

Senate but also by a large number of individuals ser

ving in the press corps, without their having- taken the

trouble to read the title or being- quite careless in what

they had to say about it.” 18 *

As the filibuster entered its second month, Title VIPs

sponsors submitted three written explanations of the bill

designed specifically to quiet the fears that Title. VII would

require racial quotas and grant special seniority rights to

minorities. Senators Clark and Case, the floor managers,

submitted an interpretative memorandum addressed to

these fears. They explained that Title VII did not mandate

racial balance, indeed it forbade “ any deliberate attempt

to maintain a racial balance” :

“ There is no requirement in Title VII that an em

ployer maintain a racial balance in his work force. On

the contrary, any deliberate attempt to maintain a

racial balance, whatever such a balance may be, would

involve a violation of Title VII because maintaining

such a balance would require an employer to hire or to

refuse to hire on the basis of race. * * * ” 10

With respect to the fears concerning seniority, the mem

orandum declared :

“ Title VII would have no effect on established sen

iority rights. Its effect is prospective and not retro

spective. Thus, for example, if a business has been

discriminating in the past and as a result has an all-

white working force, when the title comes into effect

the employer’s obligation would be simply to fill future

vacancies on a nondiscriminatory basis. He would not

be obliged—or indeed, permitted—to fire whites in

order to hire Negroes, or to prefer Negroes for future

vacancies, or, once Negroes are hired, to give them

18 Id. 3092.

10 Id. 3010.

UM» .x

16

special seniority rights at the expense of the white

workers hired earlier. (However, where waiting lists

for employment or training are, prior to the effective

date ot the title, maintained on a discriminatory basis,

the use of such lists after the title takes effect may be

held an unlawful subterfuge to accomplish discrimi

nation.) ” 20

Senator Clark also introduced a statement prepared by

the Department of Justice “ in rebuttal to the argument

made by the Senator from Alabama [Mr. Hill] to the ef

fect that Title VII Would undermine the vested rights of

seniority * * * and that Title VII would impose the re

quirement of racial balance.” 21 The Department of Justice

memorandum stated:

‘‘First, it has been asserted that title VJI would

undermine vested rights of seniority. This is not cor-

lect. Title VII would have no effect on seniority rights

existing at the time it takes effect. If, for example, a

collective bargaining contract provides that in the

event of layoffs, those who were hired last must be

laid off first, such a provision would not be affected

in the least by title VII. This would be true even in

the case where owing to discrimination prior to the

effective date of the title, white workers had more

seniority than Negroes. Title ATI is directed at dis

crimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or na

tional origin. It is perfectly clear that when a worker

is laid off or denied a chance for promotion because

under established seniority rules he is ‘low man on the

totem pole’ he is not being discriminated against be

cause of his race. Of course, if the seniority rule itself

is discriminatory, it would be unlawful under title VII.

If a rule were to state that all Negroes must be laid off

before any white man, such a rule could not serve as

20 Ibid.

21 Id. 3244.

17

the basis for a discharge subsequent to the effective

date of the title. 1 do not know how anyone could quar

rel with such a result. But, in the ordinary case, assum

ing that seniority rights were built up over a period

of time during which Negroes were not hired, these

rights would not be set aside by the taking effect of

title VII. Employers and labor organizations would

simply be under a duty not to discriminate against

Negroes because of their race. Any differences in treat

ment based on established seniority rights would not

be based on race and would not be forbidden by the

title.

* # * *

“ Finally, it has been asserted that title VII would

impose a requirement for ‘racial balance.’ This is in

correct. There is no provision, either in title VII or in

any other part of this bill, that requires or authorizes

any Federal agency or Federal court to require pref

erential treatment for any individual or treatment for

any individual or any group for the purpose of achiev

ing racial balance. No employer is required to hire an

individual because that individual is a Negro. No em

ployer is required to maintain any ratio of Negroes to

whites, Jews to gentiles, Italians to English, or women

to men. The same is true of labor organizations. On

the contrary, any deliberate attempt to maintain a

given balance would almost certainly run afoul of

title VII because it would involve a failure or refusal

lo hire some individual because of his race, color,

religion, sex, or national origin. What title VII seeks

to accomplish, what (he civil rights bill seeks to ac

complish is equal treatment for all.” 22

Finally, Senator Clark submitted a series of written

answers to questions which had been proffered by Senator

Dirksen as to (he meaning of the bill. With respect to

22 Id. 3244-45.

18

seniority the pertinent question and answer were as

follows:

“ Question. Would the same situation prevail in re

spect to promotions, when that management function

is governed by a labor contract calling for promotions

on the basis of seniority? What of dismissals? Nor

mally, labor contracts call for 'last hired, first fired.’

If the last hired are Negroes, is the employer discrimi

nating if his contract requires they be first fired and

the remaining employees are white?

“ Answer. Seniority rights are in no way affected hv

the bill. If under a 'last hired, first fired’ agreement

a Negro happens to be the ‘last hired,’ he can still be

‘first fired’ as long as it is done because of his status

as ‘last hired’ and not because of his race.” 23

With respect to the concern that the “ hill would require

employers to establish quotas for nonwhites in proportion

to the percentage of nonwhites in the labor market area,”

Senator Clark responded: “ Quotas are themselves dis

criminatory.” 24

Despite these efforts to set fear at rest, it became neces

sary, in order to secure sufficient votes to end the filibuster,

to include express language dealing with the subjects of

racial balance and seniority (the present §§ 703(j) and (h))

as part of the package of amendments known as the Mans-

field-Dirksen compromise. Senator Humphrey explained

the sponsors’ reason for accepting § 703(j) :

“ * * * A new subsection 703(j) is added to deal with

the problem of racial balance among employees. The

proponents of this bill have carefully stated on numer

ous occasions that title VII does not require an em

ployer to achieve any sort of racial balance in his work

23 Id. 3013.

24 Id. 3015.

19

force by giving preferential treatment to any indi

vidual or group. Since doubts have persisted, subsec

tion (j) is added to state this point expressly. This

subsection does not represent any change in the sub

stance of the title. It does state clearly and accurately

what we have maintained all along about the bill’s

intent and meaning. ’ ’25 *

Section 703(h), Senator Humphrey declared, served the

same purpose with respect to the fears which had been

advanced concerning seniority:

“ A new subsection 703(h) has been added, provid

ing- that it is not an unlawful employment practice for

an employer to maintain different terms, conditions,

or privileges of employment either in different loca

tions or pursuant to a seniority, merit, or other incen

tive system, provided the differences are not the result

of an intention to discriminate on grounds of race,

religion, or national origin. * * [This] change does

not narrow application of the title, hut merely clarifies

its present intent and effect. ” 2G

Even after these changes had been approved, Senator

Ervin moved to strike Title VII from the Civil Eights Act

on the ground that it unconstitutionally deprived white

employees of equal protection. Senator Clark responded:

“ Mr. President, this title would not deprive anyone

of any rights. All it does is to say that no American,

individual, labor union, or corporation, has the right

to deny any other American the very basic civil right

of equal job opportunity.

“ The bill does not make anyone higher than anyone

else. It establishes no quotas. II leaves an employer

free to select whomever he wishes to employ. It enables

a labor union to admit anyone it wishes to take in. It

25 Id. 3005.

20 Ibid.

20

tells an employment agency that it can get a job for

anyone for whom it wishes to get a job.

“ All this is subject to one qualification, and that

qualification is to state: ‘In your activity as an em

ploye]’, as a labor union, as an employment agency, you

must- not discriminate because of the color of a man’s

skin. You may not discriminate on the basis of race,

color, religion, national origin, or sex.’

“ That is all this provision does. It would establish

a legislative civil right for what has always been a

sacred American constitutional right, the right to equal

protection of the laws. That phrase does not come from

the commerce clause, but the philosophy behind it is the

philosophy behind the fail' employment practice title.

“ It merely says, ‘When you deal in interstate com

merce, you must not discriminate on the basis of race,

religion, color, national origin, or sex.’

“ Title VII as it presently exists, and as modified—

as many of us agreed, reluctantly, including myself,

that it should be modified by the Dirksen amendment—

is one of the mildest Fair Employment Practices acts

ever to be brought before the Congress.” 27

The legislative history thus confirms that while Congress

wanted the proven victims of discrimination to be made

whole, it did not want anyone to receive preferential treat

ment. “ Discriminatory preference for any group, minority

or majority, is precisely and only what Congress has pro

scribed.” Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 431

(1971). That is what the original substantive (H 703(a),

(c)) and remedial (§ 706(g)) provisions of Title VII de

clared. That is what the legislation’s sponsors stated again

and again throughout the debates. Sections 703(h) and (j)

were added—at the insistence of those whose votes were

27 Ibid,, 3092.

necessary to break the filibuster and enable passage of the

bill—merely to make doubly sure that the statute could not

be subject to any other construction.

In the next section, we will show that the statute, prop

erly construed, entitles petitioners to the remedy they seek.

We pause first, however, to observe that there are two

aspects of petitioners’ analysis of the legislative history

with which we disagree.

First, petitioners urge (brief, pp. 118-30) that the legisla

tive interpretations proffered by Senators Clark and Case

in an effort to quiet the fears that Title VII would accord

preferential rights should be disregarded. In petitioners’

view, these statements are not evidence of “ the legislative

purpose” because they were made “ weeks before §703(1:)

was conceived.” The contention that the interpretations of

a bill submitted in writing by its floor managers should be

disregarded would in any context be a startling one. In the

context of the debate over Title VII it is absurd. Here, as

in Pipefitters v. United States, 407 U.S. 385 (1972), spon

sors struggling to secure a necessary 2/3 majority sought

to reassure colleagues of their bill’s limited reach.28 This

Court recognized that sponsors’ explanations of their bill’s

meaning, which are “ entitled in any event to great weight,

[are] in this instance controlling.” Id. at 409. Moreover,

the legislative history of Title VII, recounted above, shows

clearly the significance of the Clark-Oase materials. They

explained the bill’s meaning before §§ 703(h) and (j) were

added, and as Senator Humphrey explained, the latter pro

visions merely reiterated “ what we have maintained all

along about the bill’s intent and meaning.” Leg. Hist. 3005.

28 In Pipefitters, a 2/3 majority was needed “ to overrule a pre

dictable veto” of the Taft-IIartley Act. Here, a 2/3 majority was

required to terminate an ongoing filibuster.

22

This Court’s analysis of the legislative history in Griggs v.

Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 434-436 (1971), confirms,

albeit in another context, that the Clark-Case materials

constitute authoritative evidence of Congressional intent.

The Brief for the United States and the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Commission as Amici Curiae (p. 18)

likewise recognizes these materials to be autlioiitative.

Second, petitioners contend that § 703(h) applies onL

to the question whether a violation has occurred, and not

to the question of what remedies may be piovided once

violations have independently been found. It is difficult to

perceive what benefit petitioners would derive from this

distinction, since there is an express prohibition of pref

erential remedies contained in the last sentence of § 706(g),

the bill’s remedial provision. In any event the distinction

is unsound. While it is true that $ 703(h), read literally,

talks only in terms of violation, the legislative debates, as

shown above, make clear that the considerations which

eventuated in the addition of that section encompassed con

cern for the scope of remedy as well as for the definition

'o f violation. On this point, this case is analytically indis

tinguishable from Porter Co. v. NLRB, 397 U.S. 99 (1970).

The Court dealt there with the relationship between § 8(d)

of the NLRA, which states that an employer does not vio

late his duty to bargain by refusing to agree to a union

proposal, and § 10(c), which empowers the NLRB to pro

vide such affirmative remedies against violators “ as will

effectuate the purposes of the Act.” The Court of Appeals,

noting that § 8(d) is phrased in terms of violation, held

that it did not preclude the Board from directing an em

ployer to agree to a union proposal as a remedy for viola

tions independently found. This Court rejected the at

tempted distinction, noting that “ the same considerations

— .w

23

5

i

that led Congress” to prohibit findings of violations on that

basis likewise dictated that that result not be accom

plished through remedy-formulation:

“ In reaching this conclusion the Court of Appeals

held that § 8(d) did not forbid the Board from com

pelling agreement. That court felt that “ [sjection 8(d)

defines collective bargaining and relates to a determina

tion of whether a . . . violation has occurred and not to

the scope of the remedy which may be necessary to cure

violations which have already occurred.” 128 U.S. App.

D. C., at 348, 3S9 F.2d, at 299. We may agree with the

Court of Appeals that as a matter of strict, literal

interpretation that section refers only to deciding

when a violation has occurred, but we do not agree that

that observation justifies the conclusion that the reme

dial powers of the Board are not also limited by the

same considerations that led Congress to enact § 8(d).

It is implicit in the entire structure of the Act that the

Board acts to oversee and referee the process of col

lective bargaining, leaving the results of the contest

to the bargaining strengths of the parties. I t would be

anomalous indeed to hold that while §8(d) prohibits

the Board from relying on a refusal to agree as the

sole evidence of bad-faith bargaining, the Act permits

the Board to compel agreement in that same dis

pute.” 28

The Porter analysis is particularly apposite, for § 10(c),

there construed, was the model for Title VIPs remedial

provision, § 706(g). Albemarle, 43 L.W. at 4884-85. Thus,

while § 703(h) literally talks in terms of whether a viola

tion has occurred, it expresses a Congressional policy

which precludes the fashioning of remedies inconsistent

with its underlying purpose.

29 397 U.S. at 107-108 (emphasis in original).

24

B. The R e l ie f S ought jjy P etitio ners is F ully C o n sisten t

w it h , and E ffectu a tes , t h e Congressional Objec tiv es .

This case involves employees who were originally denied

employment because of their race. The court below has fur

nished them a portion of the relief necessary to make them

whole for the discrimination they suffered: it has ordered

that they receive backpay for the period during which they

were unlawfully denied employment. While that remedy

compensates the employees for the period prior to their

obtaining employment, it docs not make them whole for

the period thereafter.

If an employee who was discriminatorily denied employ

ment in 1970, and who instead was hired in 1972, is ac

corded a 1972 seniority date, his employment career in

many respects will be inferior to that which he would have

enjoyed had he been hired in 1970. Seniority serves many

functions in the industrial setting, and a reduced seniority

standing disadvantages an employee as to each.

1. Seniority as a, measure of fringe benefit entitlement.

Although seniority is most often thought of as a means of

resolving competition between employees, it serves impor

tant non-competitive functions as well. In order to earn a

pension an employee must accumulate a designated number

of years of service with his employer. The number of weeks

of vacation which he will receive almost always increases

as his seniority increases. Entitlement to other fringe bene

fits, such as insurance and supplemental unemployment

benefits, may not take effect until he has accumulated a

specified amount of seniority. An employee who is accorded

a 1972 seniority date will not enjoy these benefits as fully

as if he had been hired in 1970 with a 1970 seniority date.

2. Protection in layoff situations. When it becomes neces

sary to reduce a workforce, the nearly universal practice

in American industry is to lay off employees in inverse

order of their seniority. When it later becomes necessary

to increase the workforce, employees are recalled from lay

off in the order of their seniority. The denial of two years’

seniority may spell the difference between an employee

remaining continuously at work or suffering- months or

years of layoff.

3. Promotional opportunities. In most industrial settings,

seniority determines which of several qualified employees

will be awarded a promotional opportunity, and conversely

which will be able to retain a preferred job when it is

necessary that some be reduced to lower-paying jobs. The

employee who is denied two years’ seniority will wait

longer to secure promotions, and will be “bumped” more

quickly to lower-paying jobs during periods of reduced

employment.

4. Seniority for other competitive purposes. Seniority is

also used to resolve other forms of employee competition.

It is often used, for example, to determine which employees

may take their vacations in the more desirable months,

which employees will work the day shift rather than the

night shift, and which employees will have first opportunity

to perform overtime work (or, for that matter, which will

have the right to refuse overtime work). In industries such

as air, rail and trucking, seniority is also used to deter

mine which employees will have the most attractive

“ runs.” It is self-evident that in all of these respects, the

denial of two years’ seniority may substantially affect the

work opportunities and life-style available to an employee.

The only way a discriminatee can be made whole is to

give him the seniority date he would have had but for the

26

refusal to hire him. That “ rightful place” remedy not only

effectuates Congress’ desire lhat discriminatccs be made

whole, it also preserves the integrity of seniority systems.

Unions and employees have favored seniority as the deter

minant of employee competition because it furnishes an

objective and equitable basis for allocating employment

opportunities. But the system remains equitable only if

all employees are given their proper seniority measure.

Equity does not exist if some employees have had their

seniority artifically reduced by the employer’s discrimina

tory behavior. Reflecting this reality, the “ rightful place”

remedy has long been deemed an implicit part of collec

tively bargained seniority. When employees are discharged

in violation of contract, unions invariably demand that they

be reinstated without interruption of seniority, and arbi

trators invariably grant that remedy.30

The correctness of this result in Title VII cases is fur

ther confirmed by the decisions under § l° ( c)> the

remedy provision of the N UR A, upon which Title VII s

remedial provision “ was expressly modeled.” Albemarle,

43 L.W. at 4884. The Board invariably awards “ rightful

place” seniority to applicants discriminatorily denied

employment. In Phelps Dodge Corp v. NLRB, 313 U.S.

177 (1941), this Court affirmed an NLRB order requir-

30 “ An employee who is discharged but later reinstated through

the grievance procedure . . . is to have the work days he lost ap

plied to his seniority.” PM. Northwest Co., 42 L.A. 961, 964

(Daniel Lyons, 1964). See also, Jordanos Markets, Die., 63 LA

345, 350 (Marshal) Ross, 1974) (“ full seniority” ) ; BASF Wyan

dotte Corp., 63 LA 121, 126 (Elliot Beitner, 1974) (“ with full

seniority” ) ; Inland Lumber Co., 62 LA 1151, 1154 (Henry 0. Mil-

moth, 1974) (“ without loss of seniority” ) ; North American Bock-

well Corp., 62 LA 901, 909 (Martin E. Conway, 1974) (“ with

complete seniority” ) ; Amoco Oil Co., 61 LA 10, 14 (Bernard

Cushman, 1973) (“ with seniority rights unimpaired” ).

27

f ta , applicants who had hoop discriminatorily do-

° aw„rfied iobs “ without prejudicenied employment be awarded ,1 ,, iq

“ thoir seniority or other rights and privileges. 1

NLRB 547, COO (19»). In e x p la in in g v*y 1 10 oar '•>

power to order “ reinstatement" of rejected app .cants, s

Court declared: “ E x p e r ie n c e having demolish at

d isc r im in a tio n in hiring is twin to discrimination nr firm ..,

it would indeed he surprising if C o n g ic s s g a re .

for the one which it denied for the otliei. -

T„ Nevada CoveolUated Copper Corp., 26 NLRB U ® .

4231 0 040), enforced, 316 V S . 1 » ( « ) , the Board made

more explicit the reined, to which discriminator,lyie-

jected applicants were entitled: “ the same or substantially

equivalent positions at which they would have been em

ployed, including any seniority or oilier ngh s oi pi

higes they would have acquired had U,e respondent not

unlawfully discriminated against them.

We have shown thus far that Title VII does not

awards of seniority which put disenr.nn^e.s in 0

rightful place. A related question is to what exten

district courts retain discretion to withhold the remedy on

the basis of countervailing considerations in

cases. Here, too, as Albeonarle. explained, the Nl-R

vidcs important guidance, for we “ may assume that Co

gross was aware that the Board, since its inception,

631, 635 (1968, , ^ ™

135 NLRB 1222, 1223 (1362); At T c i r . 1962):

NLRB 1328, 1330 ( 1 9 “ ) , M R B U 13 1U5 (1950), enforced, 246

S ' s W ) ; PacificAm»U « * " • « "

98 NLRB 582, 601 (1952).

28

awarded [‘rightful place’ seniority remedies] as a matter

of course—not randomly or in the exercise of a standard

less discretion, and not merely where employer violations

are peculiarly deliberate, egregious or inexcusable.” 43

L.W. at 4S85.32

In sum, the “ rightful place” remedy has always been rec

ognized as an integral component of an equitable seniority

system. It must be awarded if employees are to be made

whole for the discrimination they have suffered. It is in no

sense “ preferential.” 33 It is, accordingly, wholly consis-

32 In light of this standard, we think there could be few, if any,

cases where there would be justification for denying a discriminatee

his “ rightful place” seniority for fringe benefit, layoff, recall, pro

motion or demotion purposes (categories 1, 2 and 3 discussed at

pp. 24-25, s u p r a ) . There might be instances, however, where a court

could justifiably conclude that it would be unfair to permit the

immediate full use of “ rightful place” seniority for the types of

purposes listed in category 4, supra. For example, if all employees

are required at the outset of their employment to endure adverse

working conditions (e.g., night shift, undesirable runs, etc.), it

might he a windfall to allow one to escape those conditions al

together. Of course, even for these purposes it would be necessary

to invest the discriminatee with his full seniority after some initial

“ running of the gauntlet,” lest he be forever deprived of the more

desirable working conditions available only to the most senior

employees.

33 Ironically, the court below had no difficulty recognizing the

propriety of the rightful place remedy in that portion of this case

which is not before this Court. Those employees who had been clis-

criminatorilv assigned at the time of hire were awarded the right

to transfer with company seniority, so that they would be able to

reach the jobs in their new departments which they would he hold

ing had they never been discriminated against. 495 F.2d at 414-417.

The “ rightful place theory dictates that we give the transferring

discriminatee sufficient seniority carryover to permit the advance

ment he would have enjoyed, and to give him the protection against

layoff he would have had, in the absence of discrimination.” Bimj

v. Roadway Express, Inc., 435 F.2d 441, 450 (5th Cir. 1973).

btcssmmci&mu

29

tent with the congressional objectives embodied in Title

VII.33*

As we have shown, analysis of this case from the proper

perspective—first identifying the dual congressional objec

tives, and then evaluating the remedy sought in light of

those objectives—-leads to the same result in this case as

petitioners reach, albeit by a different path. But as we

noted at the outset, the importance of articulating the cor

rect analytical standard lies in its impact upon other cases,

presenting a different issue, which are already reaching

this Court’s doorstep. So that the Court is aware of that

other issue, and its ramifications, we briefly describe it in

the. next section.

C. T he “ L ast I n , F irst O u t ” L ayoff Cases, and t h e I m

plications of t h e Congressional D eterm ination to

P reclude “ referential T reatm ent

In recent years, as the nation has entered a recession

and employees have begun to be laid off in large numbers,

a new Title VII issue has arisen. Young minority and fe

male workers are contending that they should be afforded

Accord: R o b in s o n v. L o r i l a r d C o r ]) . , 444 F.2d 791, 795-800 (4th

Cir. 1971) ; U .S . v. B e t h l e h e m S t e e l C o r p . , 44G F.2d 652, 660-661

(2nd Cir., 1971) ; U .S . v. N .L . I n d u s t r i e s , Inc.., 479 F.2d 354, 374-

375 (8th Cir., 1973) ; B o iv c v. C o lg a t e P a l m o l i v e C o . , 489 F.2d 896,

901 (7th Cir. 1973) ; T h o r n t o n v. E a s t T e x a s M o t o r F r e i g h t , 497

F.2d 416, 419 (6th Cir. 1974); E E O C v. D e t r o i t E d i s o n C o . , 10

FEP Cases 239, 250 (6th Cir. 1975).

As explained in the Brief for the United States and the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission as Amici Curiae, p. IS, this

statement is not applicable to discriminatory refusals to hire prior

to the effective date of the Act (July 2, 1965), as Congress made

a deliberate judgment to preclude “ rightful place” remedies for

pre-Act discrimination. In the instant ease the discrimination oc

curred after the effective date of the Act, and thus that exception

has no application here.

special seniority protections against layoff, not because

they themselves have been discriminated against, but be

cause discrimination against others has produced a situa

tion in which preferential protection against layoff is the

only way to preserve racial or sexual balance in the work

force.

The decision which has fueled the controversy is Wat

kins v. United Steelworkers of America, 369 F.Supp. 1221

(E.D. La., 1973), pending on appeal to the Fifth Circuit as

No. 74-2604. In Watkins, the company historically bad

hired only white employees, but in recent years began lur

ing young blacks as they graduated high school and entered

the job market. The company came upon hard times, and

found it necessary to lay off half of its workers. Lndor the

terms of the collective bargaining agreement, layoffs were

made in inverse order of seniority. Only those employees

who had been hired before 1952 were kept at work. All

whites hired thereafter, and all the blacks hired in recent

years, -were laid off.

The recently-hired blacks instituted an action contend

ing that the company had violated Title VII by laying them

off. These employees did not contend that they had suffered

any prior discrimination; indeed, they conceded that they

had been hired as soon as they applied. They noted, how

ever, that the company had discriminatorily refused to hiie

a prior generation of blacks, and thus that there were no

blacks in the workforce with sufficient seniority to survive

the layoff. They sought a remedy which would keep them

selves at work, while requiring the layoff of whites who had

been hired in 1951. They reasoned that this remedy was

appropriate in order to preserve the integrated character

of the workforce.

The district court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs. It di-

30

31

vected the company to establish separate black and "hite

seniority lists, and to lay off employees separately from

those two lists in sucli a manner that, the percentage of

black employees in the workforce would remain the same

after layoff as before. The practical effect of the district

court’s order, of course, was to provide a seniority pref

erence to young black workers over whites who had been

hired before they were born.

The district court’s ruling in Watkins is an example of

what Congress intended not to allow under Title VII,

and what $$ 703(h) and (j) were enacted to make doubly

sure could not occur. Manifestly, the plaintiffs in Watkins

were not being awarded their “ rightful place”—they were

already in their “ rightful place”—but rather were being

given special rights to make up for the fact that their

ancestors had been victimized by the company’s prior dis

crimination. The district court acknowledged that its rem

edy was “ preferential,” and that the beneficiaries would

be “ persons other than those who were victims of the origi

nal discrimination.” 369 F.Supp. at 1231. But the court

thought these objections were outweighed by the need “ to

insure that, because the Company hired no blacks for

twenty years, the plant will not operate without black em

ployees for the next decade.” Ibid.

The courts of appeals—including the Seventh Circuit m

the Waters case now pending on petition for certiorari

have rejected the Watkins analysis, and have construed

Title VII as not authorizing remedies for those who cannot

prove that they have suffered discrimination.34 These

courts have concluded that Congress did not intend the

34 Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works, 502 F.2d 1309, 1317-20 (7th

Cir. 1974), petition for certiorari pending, No. 74-1064; Jersey

32

courts to deprive senior employees of tlieir jobs in order

to make room for junior minority and female employees

who, although not themselves the victims of discrimination,

seek reparations for discrimination visited upon others.

These appellate repudiations of the Watkins holding de

rive additional support from the courts’ universal rejec

tion of preferential seniority remedies in the one other

context in which, they have been sought. In several of the

discriminatory assignment cases (see pp. 28-29, n. 33, supt a),

discriminatces have sought remedies which would y i cl cl

them a seniority status superior to their rightful place.

The courts have rejected those requests, and awarded the

discriminatces only rightful place seniority. In Quarles v.

Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F.Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968),

Judge Butzncr, declaring that “ the [legislative] history

leads the court to conclude that Congress did not intend to

require ‘reverse discrimination,’ ” id. at 516, rejected a

portion of plaintiffs’ proposed remedy which “ would pre

fer Negroes even though they might have less seniority

than whites. Nothing in the Act indicates this result was

intended.” Id. at 519. Similarly in Bing v. Roadway Ex

press, Inc., 485 F.2d 441, 451 (5th Cir. 1973), the court re

jected a proposal which would have yielded discriminatces

“ more seniority than they would have had in the absence

of discrimination.” Accord: Thornton v. East Texas Motor

Freight, 497 F.2d 416, 420 (6th Cir. 1974); Rodriguez v.

Pourr Central cO Light Co. v International Bhd. of Electrical

Workers, 508 F.2d 687, 705-710 (3rd Cir. 1975); U.S. v. Local

189, United Papermakers, 416 F.2d 980, 994-995 (5tli Cir. 1969)

(dictum), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970). Accord: Cox v. Allred

Chemical Corp.. 392 F. Supp. 309, 318-320 (M.D. La. 1974).

Contra: Log v. City of Cleveland. 8 FEP Cases 614 (N.D. Ohio

1974); Delay v. Carling Brewing Co., 10 FEP Cases 164 (N.D. Ga.

1974); Schaefer v. Tannian, 10 FEP Cases 897 (E.D. Mich. 1975).

i.

East Texas Motor Freight, 505 F.2d 40, G3-64 and n. 30

thereat (5th Cir. 1974).

II. This Case Should Not Be Decided on the Basis of 42

U.S.C. § 1931.

A. As an alternative ground for reversal petitioners in

voke §1 of the Civil Nights Act of 1806, 42 U.S.C. §1981.

They contend that § 1981 was violated by the refusal to

hire them and that the appropriate remedy for that viola

tion is not affected by § 703(h) of the 1964 Act. As we have

shown, petitioners are entitled to prevail in this case be

cause neither § 703(h) nor any other provision of the 1964

Act prevents giving “ rightful place” seniority to an indi

vidual who was denied a job because of his race. It is

therefore not necessary to consider in this case the in

terrelationship between the 1866 and 1964 statutes. And

it would be entirely inappropriate to decide this case on

the basis of the earlier Act because petitioners relied exclu

sively on the 1964 Act when, in the court of appeals, they

challenged the district court’s denial of seniority credit.

The court of appeals’ failure to discuss §1981, which

petitioners criticize here (hr. 40) is therefore readily un

derstandable. As this Court stated in an earlier civil rights

case, Adict.es v. S. II. Kress and Co., 398 U.S. 144, 147, n.

2 (1970):

“ "Where issues are neither raised before nor con

sidered by the Court of Appeals, this Court will not

ordinarily consider them. Lawn v. 1 nited States, 355

U.S. 339, 362-363, n. 16 (1958); Ilusty v. United States,

282 U.S. 694, 701-702 (1931); Duignan v. United States,

274 U.S. 195, 200 (1927). W’< decline to do so here.”

B. "While we submit that no question under the 1800 Civil

Rights Act need or should be reached in this ease, we briefly

state our understanding ot that statute and its relationship

33

\

a

4

\

34

to the 1964 Act. Here again, our views differ from those of

the petitioners, although not in a .manner which would

affect the outcome of the present action. In Johnson v. Rail

way Express Agency, Inc., 43 L.W. 4623, 4625 (May 19,

1975), this Court joined the courts of 'appeals which had

held “ that 4 1981 affords a federal remedy against dis

crimination in private employment on the basis of race,” 35

and declared that “ [a]n individual who establishes a cause

of action under § 1981 is entitled to both equitable and legal

relief, including compensatory and, under certain circum

stances, punitive damages.”

Where, as here, individuals have been refused a job be

cause of their race, the award to them of “ rightful place”

seniority is, for the reasons stated at pp. 24-29 supra,

“ suitable” (42 U.S.C. §1988). Therefore, there is no in

consistency in this case between the remedial provisions of

the 1866 Act (§3 of which is now 42 U.S.C. § 1988)36 and

any provision of the 1964 Act. Conversely, there is no con

flict between the two statutes with respect to the individual

who, as in the Watkins-type, situation, has not been dis

criminated against on the basis of race. This is true be-

35 Since the present case involves discrimination in hire, we have

no occasion to discuss the scope of the substantive right created

by § 1981 with respect to employment matters other than refusal

to hire. That question is raised in the Cross-Petition for Certiorari

in the W a t e r s litigation, United Order of American Bricklayers,

etc. v. Waters, No. 74-1350, pp. 2, 17.

30 Section 1988 provides:

The jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters conferred on

the district courts by the provisions of this chapter and Title

18, for the protection of all persons in the United States in

tlieir civil rights, and for their vindication, shall be exercised

and enforced in conformity with the laws of the United States,

so far as such laws are suitable to carry the same into effect;

but in all cases where they are not adapted to the object, or

p — ■*.

35

cause one who is not a discriminatee has no cause of

action under the 1866 Act. Plainly, the basic policy of

Title VII against giving anyone preference in employment

because of his race is that of the 1866 Act as well, as

appears from the language of §1, “ all persons * * *

shall have the same right * * * as is enjoyed by white

citizens * * That the 1866 and 1964 Acts, whatever their

other differences (cf. Johnson, 43 LAV. at 1625), are

identical in this particular was well stated by the Court of

Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in Long v. Ford Motor Go.,

496 F.2d 500, 505 (1974) (footnotes omitted) :

“Section 1981 is by its very terms, however, not an