Texas v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Brief Amici Curiae in Support of No Party and Reversal

Public Court Documents

September 12, 2018

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Texas v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Brief Amici Curiae in Support of No Party and Reversal, 2018. 0d3072ec-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b532abe1-eb2e-428c-b343-b859fa3ef44b/texas-v-equal-employment-opportunity-commission-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-no-party-and-reversal. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

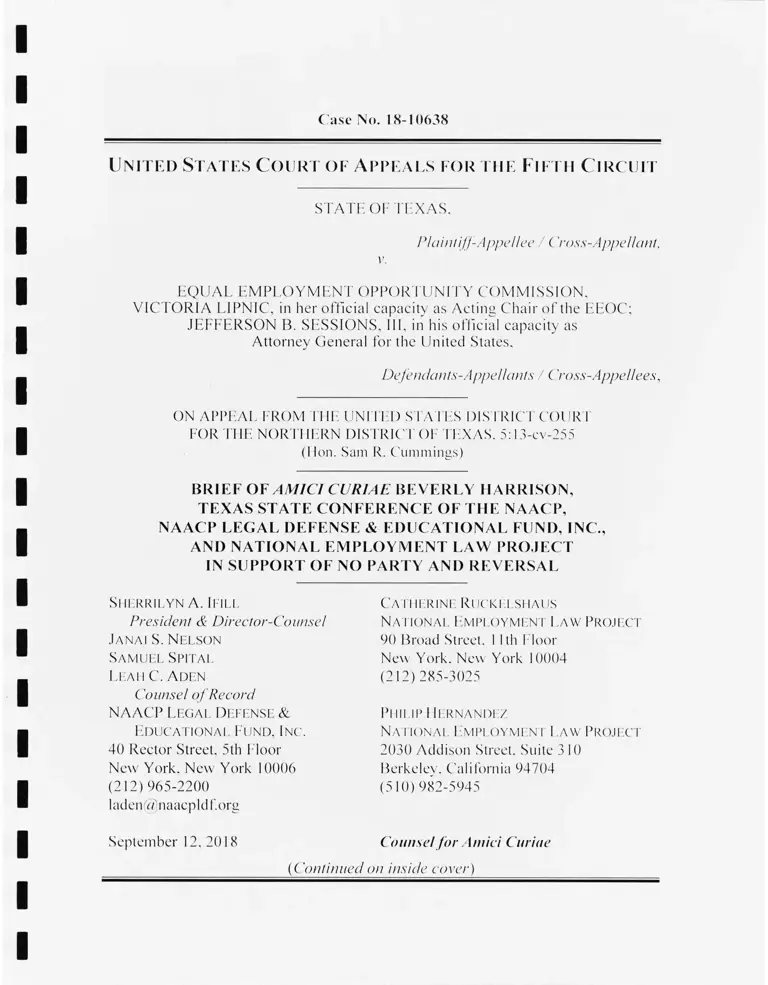

Case No. 18-10638

United States Court of Appears for hie Fifth Circuit

STATE OF TEXAS.

Plaintiff-Appellee / ( 'ross-Appellant,

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION,

VICTORIA LIPNIC, in her official capacity as Acting Chair of the EEOC;

JEFFERSON B. SESSIONS, III, in his official capacity as

Attorney General for the United States,

Defendants-Appellants / ( 'ross-AppeUees,

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNI I I I) S PA IIS DIS PR1C I COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRIC f OF TEXAS. 5:13-cv-255

(Hon. Sam R. Cummings)

BRIEF OF AMICI C URIAE BEVERLY HARRISON,

TEXAS STATE CONFERENCE OF THE NAACP,

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AND NATIONAL EMPLOYMENT LAW PROJECT

IN SUPPORT OF NO PARTY AND REVERSAL

Sill RRILYN A. 1FILL

President & Director-Counsel

Ja n a i S. N e l so n

S a m u e l S pital

E lam C. A d en

Counsel o f Record

NAACP L eg a l D e fe n se &

Ed u c a t io n a l Fu n d . In c .

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York. New York 10006

(212)965-2200

laden 4/ naacpld f.org

September 12. 2018

__________________ (Continued

LAI I ILIUM RUCK EL SH A US

N a t io n a l E m p l o y m e n t La w Project

90 Broad Street. 1 1th Floor

New York. New York 10004

(212)285-3025

Philip I Ie r n a n d l z

N a t io n a l E m p l o y m e n t La w Project

2030 Addison Street. Suite 3 10

Berkeley. California 94704

(510)982-5945

Counsel for Amici Curine

i inside cover)

How a r d B. C i.o d i m a n . Ill

Cl ()l OMAN cY Cl <)(0 MAN. I I P

3 3 0 1 1 ;.lm Street

Dallas. Texas 75226

( 214 ) 939-9222

R< )0 i:r i 11. S troi r

(N.Y. Bar No. 2824712)

I )ana Bosnia

(N.Y. Bar No. 706482)

I i vy Ra t n k r . P.C.

80 I ighth A venue

New York. New York 1001 1

( 212 ) 627-8100

SUPPLEMENTAL CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

AND CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Pursuant to Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 26.1 and Fifth Circuit Rule

29.2, amici curiae provide this supplemental certificate of interested persons to fully

disclose all the persons and entities as described in the fourth sentence of Fifth

Circuit Rule 28.2.1 that have an interest in the outcome of this case. These

representations are made in order that the judges of this Court may evaluate possible

disqualification or recusal.

1. Beverly Harrison (amicus curiae)

2. NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (PDF) (amicus curiae)

3. National Employment Law Project (NELP) (amicus curiae)

4. Texas State Conference of the NAACP (Texas NAACP) (amicus curiae)

5. Sherri lyn A. I fill (LDF) (counsel for amici curiae)

6. Samuel Spital (LDF) (counsel for amici curiae)

7. Leah C. Aden (LDF) (counsel for amici curiae)

8. Catherine Ruckelshaus (NELP) (counsel for amici curiae)

9. Philip Hernandez (NELP) (counsel for amici curiae)

10. Edward B. Cloutman, III (counsel for amici curiae)

1 1. Robert 11. Stroup (counsel for amici curiae)

Dana Lossia (counsel {'ox amici curiae)

Amici NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund. Inc., and National

Employment Law Project, Inc. certify that they are 501(c)(3) non-profit

corporations. Amicus Texas State Conference of the NAACP is a nongovernmental

corporation. None of these amici has a corporate parent or is owned in whole or in

part by any publicly held corporation.

s/ Leah C. Aden

Leah C. Aden

Counsel of Record for Amici Curiae

u

I ABLE OF CONTENTS

PACE

SUPPLEMENTAL CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS AND

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT........................................................ i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.....................................................................................v

IDENTITY & INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE.......................................................1

INTRODUCTION & SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.............................................. 2

ARGUMENT.............................................................................................................. 4

I. TEXAS HAS FAILED TO ESTABLISH ARTICLE III STANDING

TO CHALLENGE THE GUIDANCE............................................................ 4

II. THE 2012 GUIDANCE REPRESENTS A VALID INTERPRETATION

OF TITLE VII................................................................................................... 6

A. The Department’s New Views on Disparate Impact Liability

Find No Support in Title VII’s Language or Jurisprudence.................6

B. Courts Have Long I leld that Facially-Neutral I Iiring Policies that

Exclude Applicants with Conviction or Arrest Records Can

Violate Title VII.....................................................................................8

C. The Guidance is Entitled to Deference................................................12

III. EMPLOYMENT POLICIES THAT CATEGORICALLY EXCLUDE

INDIVIDUALS WITH FELONY AND OTHER CONVICTION

RECORDS ARE COUNTERPRODUCTIVE IN EVERY RESPECT........13

A. Policies that Render Employment Unattainable for People with

Records Weaken Our Economy...........................................................15

PAGE

B. Policies that Render Employment Unattainable for People with

Records Undermine Public Safety...................................................... 19

C. Policies that Render Employment Unattainable for People with

Records Come at the Expense of Communities and Families........... 20

D. The Texas Legislature—Aware of the Damage to the Economy,

Public Safety, and Families Wrought by Its Policies— Has Begun

Taking Steps to Address Employment Barriers for Individuals

with Records......................................................................................... 22

CONCLUSION......................................................................................................... 23

APPENDIX............................................................................................................ A -1

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE..................................................................... C-l

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE...............................................................................C-2

I V

t a b u : o f a u t h o r i t i e s

PACE(S)

CASES:

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975).......... ................................................................................A-4

Avoyelles Sportsmen's League, Inc. v. Marsh,

715 T.2d 897 (5th Cir. 1983)................................................................................. 5

City o f Los Angeles v. Lyons

461 U.S. 95 (1983)................................................................................................ 4

DaimlerChrysler Corp. v. Cuno,

547 U.S. 332 (2006)...............................................................................................4

Edelman v. Lynchburg College,

535 U.S. 106 (2002),...........................................................................................4-5

EEOC v. Com. Office Prod. Co.,

486 U.S. 107 (1988)........................................................................................... 12

El v. Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA),

479 F.3d 233 (3d Cir. 2007)................................................................................ 10

Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976).......................................................................................... A-4

Green v. Missouri Pacific Railroad,

523 F.2d 1290 (8th Cir. 1975)................................................................... 7, 10. 1 1

Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971).......................................................................... 8, 9, A-4, A-5

v

PACE(S)

Guerrero v. Cal. Dept o f Cons. & Rehab..

1 19 F. Supp. 3d 1065 (N.D. Cal. 2015),

aff’d in part, rev 'd in part and remanded.

No. 15-17001,2017 WL 2963531 (9th Cir. .Inly 12, 2017)....................... 12, A-6

Hithon v. Tyson Foods. Inc..

144 F. App’x 795 (11th Cir. 2005)....................................................................A-4

Houser v. Pritzker,

28 F. Supp. 3d. 222 (S.D.N.Y. 2014).................................................................. 11

Lewis v. City o f Chicago,

560 U.S. 205 (2010)............................................................................................A-4

Lujan v. Defs. o f Wildlife.,

504 U.S. 555 (1992).......................................................................................... 4, 5

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union,

491 U.S. 164 (1989)............................................................................................A-4

Perez v. Mortg. Bankers Ass n,

135 S. Ct. 1199 (2015)............................................................................................5

Richardson v. Llotel Corp. o f Am.,

332 F. Supp. 519 (E.D. La. 1971),

aff'd, 468 1 .2d 951 (5th Cir. 1972)..................................................................... 10

Rogers v. Pearland Indep. Sell. Dist.,

827 F.3d 403 (5th Cir. 2016).........

Simon v. E. Kentucky Welfare Rights Org.,

426 U.S. 26 (1976)............................. ....................................................................5

Skidmore v. Swift & Co.,

323 U.S. 134 (1944)............................................................................................ 12

VI

Waldon v. Cine in noli Pub. Schs.,

941 F. Supp. 2d 884 (S.D. Ohio 2013)..........................................................7, A-4

Watson v. Fort Worth Bank & Trust.,

487 U.S. 977 (1988).............................................................................................. 8

Williams v. Parker,

843 F.3d 617 (5th Cir. 2016)................................................................................. 4

PAGE(S)

STATUTES & REGULATIONS:

42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e et seq......................................................................................................... 1

§ 2000c-2 ................................................................................................................. 5

§ 2000e-2(k)( 1 )(A)(i)................................................................................................ 9

§ 2000e-2(k)( 1 )(A)(ii).............................................................................................. 9

Civil Rights Act of 1991, Pub. L. No. 102-166, 105 Stat 1071............................... 9

Tex. Occ. Code §§ 53.022 53.02.3......................................................................... 22

PAG E(S)

OTHER AUTHORITIES:

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the

Age o f Colorblindness (The New Press 2010) ................................................... 14

Am. Civil Liberties Union, Back to Business: How Hiring Formerly

Incarcerated Job Seekers Benefits Your Company (2017) ............................... 19

Beth Avery & Michelle Natividad Rodriguez, Nat'l Emp't I.aw Project,

Unlicensed and Untapped: Removing Barriers to State Occupational

Licenses for People with Records (April 2016).................................................. 17

PAG FTS)

vii

Mark T. Berg & Beth M. I Iuebner, Reentry and the Ties that Bind: An

Examination o f Social Ties. Employment, and Recidivism.

28 Just. Q. 382 (Apr. 2011) ................................................................

PAGE(S)

19

Cherrie Bucknor & Alan Barber, Ctr. for Econ. & Policy Research,

The Price We Pay: Economic Costs o f Barriers to Employment for

Former Prisoners and People Convicted o f Felonies (June 2016) ................... 18

E. Ann Carson, U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Full Report, Prisoners

in 2016 (Aug. 2018)........................................................................................... 13

Maurice Chammah, Business Association Scores Victories on Criminal

Justice Agenda, Tex. Trib. (May 23, 2013)........................................................ 22

Anastasia Christman & Michelle Natividad Rodriguez, Nat'l Emp’t

Law Project, Research Supports Fair Chance Policies (Aug. 1,2016) ........... 13

Class Lawsuit Settlement Agreement, WMATA,

No. l:14-cv-01289-RMC (D.D.C. Dec. 20. 2017), ECF No. 230-1.......... 11, A-4

Lucius Couloute & Daniel Kopf, Prison Policy Initiative, Out o f Prison &

Out o f Work: Unemployment Among Formerly Incarcerated People

(July 2018)........................................................................................................... 16

Scott H. Decker, et ah, Nat’l Inst, of Justice, Criminal Stigma, Race, Gender,

and Employment: An Expanded Assessment o f the Consequences o f

Imprisonment for Employment (Jan. 2014).........................................................21

Le’Ann Duran, et ah. The Council of State Gov’ts Justice Ctr., Integrated

Reentry and Employment Strategies: Reducing Recidivism and Promoting

Job Readiness (Sep. 2013) ............................................................................

Econ. League of Greater Ph i la., Economic Benefits o f Employing Formerly

Incarcerated Individuals in Philadelphia (Sept. 2011)

vn

19

p a ( ; e (S)

Exec. Office of the President, Economic Perspectives on Incarceration

and the Criminal Justice System (Apr. 2016) .................................................... 14

Fed. Bureau of Investigation, Crime in the United States, 20/6: Table

2IA (2017).............7. ............................................................................................ 14

Helen Gaebler, Criminal Records in the Digital Age: A Review’ o f

Current Practices and Recommendations for Reform in Texas

(William Wayne Justice Ctr. for Public Interest Law, Univ. of Tex.

School of Law, Mar. 2013)............................................................................ 14, 15

I I.B. 1188, 85th Leg. (Tex. 2017)........................................................................... 22

Jennifer Lundquist, et ah. Does a Criminal Past Predict Worker

Performance? (Dec. 2, 2016).............................................................................. 18

Michael Massoglia, Sarah K.S. Shannon, Jason Schnittker, Melissa

Thompson, Christopher Uggen, & Sara Wakelleld, The Growth, Scope,

and Spatial Distribution o f People with Felony Records in the United

States, 1948 to 2010 (Demography, Vol. 54, Sept. 2017).................................. 14

Mem. & Op., Little v. Wash. Metro Area Transit Auth. (WMATA),

No. 1:14-cv-01289-RMC (D.D.C. Apr. 18, 2017), ECF No. 186............. 1 1. A-4

Dylan Minor, Nicola Persico & Deborah M. Weiss, Criminal Background

and Job Performance? Evidence from America's Largest Employer

(May 1.2017) ...................................................................................................... 18

Rebecca L. Naser & Christy A. Visher, Family Members ’ Experiences

with Incarceration and Reentry, 7 W. Criminology Rev. 20 (2006) ................ 21

Ryan Nunn, The Brookings Institution, How Occupational Licensing

Matters for Wages and Careers (Mar. 2018) ..................................................... 17

Devah Pager, The Mark o f a Criminal Record,

108 Am. J. Soc. 937 (Mar. 2003) ....................................................................... 16

I X

PAGFYS)

The Sentencing Project. Incarcerated Women and Girls (Nov. 2015) ................ 2 1

The Sentencing Project, Trends in U.S. Corrections (June 2018)................... 14, 15

Soc’y for I Inman Res. Mgmt., Background Checking The Use o f

Criminal Background Checks in Hiring Decisions (Jul. 19, 2012)................... 16

Tex. Dep't of Criminal Justice, Statistical Report Fiscal Year 2016.................... 13

Senfronia Thompson, Judiciary & Civ. Juris. Comm. Rep.,

Bill Analysis ofH.B. 1188 (2013)........................................................................ 16

U.S. Census Bureau, Comparative Demographic Estimates.................................. 14

U.S. DepT of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Survey o f State

Criminal History Information Systems, 2016: A Criminal Justice

Information Policy Report, Table 1 (Feb. 2018) .......................................... 13, 14

Rebecca Valias, et ah, Ctr. for Am. Progress, Removing Barriers to

Opportunity for Parents with Crim inal Records and Their

Children (Dec. 2015) .......................................................................................... 20

Christy Visher, et ah, Urban Inst., Employment after Prison: A Longitudinal

Study o f Releasees in Three States (October 2008)............................................ 20

Peter Wagner & Wendy Sawyer, Prison Policy Initiative, States o f

Incarceration: The Global Context 2018 (June 2018) ....................................... 13

Bruce Western & Becky Pettit, Pew Charitable Trusts, Collateral Costs:

Incarceration's Effect on Economic Mobility (2010) ........................... 15, 16, 20

Chrystal S. Yang, Local Labor Markets and Criminal Recidivism,

147 .1. Pub. Econ. 16 (Dec. 2016) ....................................................................... 19

x

DENTITY & INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

Amici curiae are civil lights organizations and a directly impacted individual

in Texas, all of whom have a demonstrated interest in protecting the rights of those

who seek employment in the State ofTexas, pursuant to Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq. ("Title VII”).

Amicus Beverly Harrison is a 62-year-old Black woman who resides in Dallas,

Texas and was terminated from a job with Dallas County Schools in 2013 because

of a conviction in 1975. Amicus the Texas State Conference of the NAACP is a non

profit civil rights organization in Texas that advocates for the rights of Black

Americans, including those with conviction records. Amicus the NAACP Legal

Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. is a non-profit, non-partisan law organization,

which advocates for racial justice, including the civil rights of Black people with

records to have opportunities for employment. Amicus the National Employment

Law Project is a non-profit legal research and advocacy organization that specializes

in the employment rights of people with arrest and conviction records.

Additional information about Amici appears in the Appendix. All parties

consent to the filing of this brief.1

No party's counsel authored this brief either in whole or in part. No party, party's counsel, or

person or entity other than Amici. Amici '.v members, and their counsel contributed money intended

to fund preparing or submitting this brief. See Fed. R. App. P. 29(a)(4)(E).

INTRODUCTION & SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

At precisely no point in the life of this nearly five-year-old litigation has the

State of Texas properly established as is its burden Article III standing to pursue

its claims. Texas has, in effect, sought an advisory opinion declaring that its hiring

practices related to conviction records—covering potentially thousands of existing

policies as well as hypothetical, future policies—are lawful pursuant to Title VII.

But without a real case or controversy, the State of Texas has had no business in

federal court on its claims, whether today or in November 2013, when it first filed

this litigation.

While this case therefore can and should- be decided on its many technical

deficiencies, Amici also write, in the event that this Court reaches the merits, to

defend the Guidance, particularly in light of the Department of Justice’s

(“Department”) recent about-face on the issue of disparate impact analysis under

Title VII. As the Department readily acknowledged as recently as 2017, and on many

prior occasions, the Guidance is reasonable and consistent with decades-old Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission (“EEOC”) policy and reflects longstanding

federal case law from multiple circuits. As such, the 2012 Enforcement Guidance on

the Consideration of Arrest and Conviction Records in Employment Decisions

(“Guidance”) deserves far more than a sterile, pro-forma defense.

i

Beyond the technically deficient and meritless claims in this litigation. Texas

has ignored the many harms that flow from blanket hiring exclusions of people with

felony records, like those that it has preemptively and prematurely sought to have

declared lawful. Amici believe it is critical for the Court—again, should it reach the

merits to have an understanding of the breadth and depth of the case’s impact on

millions of Americans, including the disproportionate number of Black and Latino

Texans who have criminal histories.

People with records are not simply “felons” or “criminals,” as Texas has

labeled them throughout this litigation. They are family members, friends, and

neighbors. They form a large portion of the U.S. population: nearly 1 in 3 adults.

Employment barriers faced by people with records too often deprive them of

a means to support themselves, their families, and their communities. Their resulting

unemployment weakens our national, state, and local economies and drives up

recidivism rates. Furthermore, through overbroad hiring restrictions, employers

needlessly screen out a hard-working segment of the talent pool, as exemplified by

the experiences o{'Amicus Ms. Harrison.

Justice is not served when laws are assessed blindly, without knowledge of

their disparate and negative impacts, including on communities of color. Amici offer

information to assist this Court in fully reckoning with the legal and public policy

implications of its decision and the district court’s ruling below. Amici respectfully

oJ)

request that the district court's grant of partial summary judgment in favor of Texas

be reversed and the injunctive relief afforded to T exas be vacated.

a r g u m e n t

1. TEXAS MAS FAILED TO ESTABLISH ARTICLE MI

STANDING TO CHALLENGE THE GUIDANCE.

T exas has not —and cannot establish standing in this ease, which is fatal to

its efforts to obtain relief in this litigation. The “core component of standing is an

essential and unchanging part of the case-or-eontroversy requirement of Article III."

Lujan v. Defs. o f Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555, 560 (1992). “If a dispute is not a proper

case or controversy, the courts have no business deciding it, or expounding the law

in the course of doing so.” DaimlerChrysler Corp. v. Cuno, 547 U.S. 332, 341

(2006). The State of Texas, as the party asserting federal jurisdiction, carries the

burden of establishing standing. See id. at 342; Williams v. Parker, 843 F.3d 617,

620 (5th Cir. 2016) (noting that “[standing is a threshold issue,” which courts

“consider before examining the merits.”).

In many respects, Amici agree with the arguments made by the Department

demonstrating that Texas's allegations are insufficient to establish an injury-in-fact

required for standing. See City o f Los Angeles v. Lyons, 461 U.S. 95, 95, (1983)

(“[T]he injury or threat of injury must be Teal and immediate,’ not ‘conjectural’ or

‘hypothetical.’”) For example, the EEOC is not permitted under Title VII to issue

substantive rules, Edelman v. Lynchburg College, 535 U.S. 106, 122 (2002). which

4

necessarily means that the Guidance is not binding on Texas because it lacks the

"force and effect of law.” See Perez v. Mortg. Bankers Ass > 7 , 1 35 S. Ct. 1 199, 1200-

01 (2015) (citation omitted); see also DOJ Br. 18. In addition, a world without the

Guidance would not remedy the alleged injury articulated by Texas because existing

federal law namely, Title VI1- prohibits racial discrimination in hiring and

establishes disparate impact liability.2 See DOJ Br. 18. 19; see also 42 U.S.C. §

2000e-2; Lujan, 504 U.S. at 560-61 (explaining that an injury must be redressable

by a court for a plaintiff to establish standing). Texas, therefore, has not left the realm

of the hypothetical, and has not satisfied the “irreducible constitutional minimum of

standing.” Lujan, 504 U.S. at 560.

Amici also underscore that it is of no consequence—at least for purposes of

standing that the Department is expressing different views than the EEOC with

respect to the analysis of disparate impact claims in the Guidance. DOJ Br. 20-23.

Whether there is disagreement or consensus, the crux of the issue is that Texas has

not demonstrated any cognizable injury, much less one that "fairly can be traced” to

the actions of the EEOC or the Department. See Simon v. E. Kentucky Welfare Rights

Org., 426 U.S. 26, 41 (1976).

2 As the Department argues, the Guidance is not (Inal agency action because it is not "determinative

of issues or rights" nor does it "foreclose alternate courses o f action or conclusively affect rights

of private parties." DOJ Br. 28-30; Avoyelles Sportsmen's League. Inc. r. Marsh. 715 F.2d 897.

908-09 (5th Cir. 1983).

5

II. THE 2012 GUIDANCE REPRESENTS

INTERPRETATION OF TITLE VII.

A VALID

Given that Texas lacks standing, Amici contend, as does the Department, that

this Court does not have jurisdiction to examine the merits of the Guidance. DOJ Br.

23. But in the event that the Court does reach the merits, and in light of the

Department's newly professed differences with the EEOC regarding disparate

impact liability, Amici write to support the EEOC’s view of Title VII as expressed

in the Guidance, which is both reasonable and entitled to deference.

A. The Department’s New Views on Disparate Impact Liability Find

No Support in Title VIPs Language or Jurisprudence.

As an initial matter, it bears emphasizing that the Department's abrupt shift in

position on disparate impact liability is exactly that: abrupt and in tension with its

own recently held views, including in this very case. In its brief for this Court, the

Department states—rather remarkably— that it “does not believe that nationwide

data regarding arrest or conviction rates is probative of whether a particular

employer’s policy has a prohibited disparate impact.” DOJ Br. at 22. Yet in

September 2017. the Department persuasively argued to the district court in this case

that:

“[T]he Guidance is also reasonable in its discussion of disparate impact

liability. First, the Guidance sets forth the basic legal standards

applicable to Title VII disparate impact claims, citing the statute and

Supreme Court precedent. It then goes on to apply that analysis to the

use of criminal background information in employment decisions,

reasoning that Title VII disparate impact liability would be shown

6

where "a covered employer's criminal record screening policy or

practice disproportionately screens out a Title Vll-protected group and

the employer does not demonstrate that the policy or practice is job

related for the positions in question and consistent with business

necessity." This statement, again, is an elementary legal proposition.”3

Moreover, in 2014, the Department contended in this litigation that “depriving

individuals of employment opportunities on the basis of their criminal histories can

constitute disparate-impact race discrimination”4 and, in support of that point, cited

several cases in which the probative value of statistical trends in showing disparate

impact was acknowledged. See Green v. Missouri Pac. R.R., 523 F.2d 1290, 1293-

94 (8th Cir. 1975) (outlining three ways to establish a prima facie case of disparate

racial impact, including statistical evidence showing that “blacks as a class (or at

least blacks in a specified geographical area) are excluded by the employment

practice in question at a substantially higher rate than whites.”); Waldon v.

Cincinnati Pub. Sch., 941 F. Supp. 2d 884, 888 (S.D. Ohio 2013) (explaining that

“[disparate impact results from facially neutral employment practices that have a

disproportionately negative effect on certain protected groups and which cannot be

3 See ROA. 1 552-53. As o f the filing o f this brief. Amici could not access the full record on appeal,

even after tiling a Notice o f Appearance and contacting the Clerk's office. Amici attempted to

identify the precise record cites based on a review of the district court's docket sheet liled by

Defendants-Appellants which identified the ROA starting page number for each document. To the

extent that Amici have mis-calculated these record cites by one or more pages. Amici welcome the

opportunity to file a supplemental brief correcting those cites.

1 See ROA.526: see also supra note 3.

7

justified by business necessity” and that “[ujnlike disparate treatment, disparate

impact ... is based on statistical evidence of systematic discrimination”).

In short, while the Department's position has drastically changed, the relevant

statutory provisions of Title VII have not. Nor have there been—despite the

Department’s reliance on a single decades-old plurality opinion in Watson v. Fort

Worth Bank & Trust, 487 U.S. 977 (1988)—any significant new developments in

Title VII jurisprudence that would support a departure from the EEOC’s views on

disparate impact liability, as articulated in the Guidance. DOJ Br. 21. The discussion

of Title VII below fortifies this point.

B. Courts Have Long Held that Facially-Neutral Hiring Policies that

Exclude Applicants with Conviction or Arrest Records Can Violate

Title VII.

Nearly 50 years ago, the Supreme Court in Griggs v. Duke Power Co. first

acknowledged that disparate impact claims challenging facially-neutral employment

policies could succeed under Title VII. 401 U.S. 424 (1971). There, Duke Power

Company adopted a facially-neutral policy requiring individuals to pass two aptitude

tests and have a high school education. Id at 428. Noting that Congress’s aim in

enacting Title VII was to “achieve equality of employment opportunities and remove

barriers” favoring white employees over other employees, the Court held that Title

VII allows for disparate impact and disparate treatment claims. Id. at 429-31.

8

Congress later codified disparate impact analysis through the 1991

amendments to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Civil Rights Act of 1991. Pub. L. No.

102-166, 105 Stat 1071 (stating that the purposes of the act include “codify[ing] the

concepts o f ‘business necessity' and ‘job related' enunciated by the Supreme Court

in Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 IJ.S. 424 (1971), and in . . . other Supreme Court

decisions”). Title VII now expressly protects against employment practices that are

facially neutral yet have a disparate impact on the basis of race, color, religion, sex,

or national origin unless the employer can show that the practice or policy is “job

related for the position in question and consistent with business necessity.” 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-2(k)( 1 )(A)(i) (2017). If the employer can show that the practice is job-

related and consistent with business necessity, the complainant can still prevail by

demonstrating the availability of a less discriminatory alternative employment

practice. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(k)( 1 )(A)(ii) (2017).

After Griggs, federal courts have held that an employer’s race-neutral policy

against hiring individuals with a conviction record may violate Title VII under a

disparate impact framework. Regardless of the outcome of this litigation, Title VII

continues to prohibit any policy that Texas may employ to bar applicants with felony

convictions- if such policies have a racially disparate impact and are not job related

and consistent with business necessity -as even the Department concedes. DOJ Br.

at 18, 19.

9

Indeed, more than 40 years ago, the Eighth Circuit in Green v. Missouri

Pacific Railroad further refined the analysis in Griggs by identifying three factors

which are relevant to performing a business necessity analysis of the link between a

criminal conviction and a particular employment position: (1) the nature and gravity

of the offense or conduct; (2) the time that has passed since the offense, conduct,

and/or completion of the sentence; and (3) the nature of the job held or sought. 523

F.2d 1290, 1297 (8th Cir. 1975).'' The Green court performed this analysis in the

context of holding that Missouri Pacific Railroad’s absolute bar on hiring any person

convicted of a crime other than a minor traffic offense was discriminatory on the

basis of race under Title VII. Id. at 1298-99.

More recently, in El v. Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority

(SEPTA), the Third Circuit reiterated that hiring policies excluding people with

records can violate Title VII if they have a disparate impact on people of color and

are not job-related and consistent with business necessity. 479 F.3d 233, 239 (3d Cir.

2007). Although the panel affirmed summary judgment for the employer on grounds 5

5 Prior to Green, federal courts recognized that an employer policy that was not “reasonable and

related to job necessities" could violate Title VII. Richardson v. Hole! Corp. o f Am., 332 F. Supp.

519. 521 (E.D. La. 1971). aff'd. 468 F.2d 951 (5th Cir. 1972). In Richardson, a Black individual

with a prior conviction for theft was hired as a bellman, but was asked to take another position

within the company upon discovery of his conviction. Id. at 520. Mr. Richardson rejected the offer

and was discharged. Id. While recognizing that whether such a termination passes Title VII muster

depends on the particular job. the court held in favor of the defendant, finding that the evidence

presented demonstrated that the hotel rejected individuals with conviction records from positions

that were considered “security sensitive." such as a bellman. Id. at 521.

10

of business necessity, it did so only after noting the relevance of the age, nature of

the offense, and nature of the job. among other things, to a proper business necessity

analysis. Specifically, the Third Circuit tailored its previous standard for business

necessity from the “minimum qualifications necessary for successful performance

of the job in question” to one that allows for a policy that “can distinguish between

individual applicants that do and do not pose an unacceptable level of risk.” Id. at

243, 245. The panel noted that summary judgment might have been properly denied

if only the plaintiff had introduced certain additional evidence (such as expert

testimony) undermining the defendant’s business necessity defense.6

Thus, federal courts have long applied disparate impact analysis to cases

where employers rejected job applicants because of their conviction record. The

Eighth and Third Circuits, as well as numerous district courts, have acknowledged

6 Job applicants and employees have increasingly filed challenges to hiring decisions based on

background checks. Just last year, in Little v. Washington Metro Area Transit Authority ( WMATA),

a federal court certified a class o f affected job applicants with respect to plaintiffs' claim that

WMATA's criminal background check policy is facially neutral, but has a disparate impact on

Black applicants. Mem. & Op.. WMATA at I. 46-47. No. 1:14-cv-01289-RMC (D.D.C. Apr. 18,

201 7), ECF No. I 86; see also Class Lawsuit Settlement Agreement, WMATA. No. I: l4-cv-01289-

RMC (D.D.C. Dec. 20. 2017). ECF No. 230-1 (settling claims o f individuals and class

representatives terminated, suspended, or denied employment as a result o f the application o f a

criminal background screening policy).

Similarly, in Houser v. Pritzker, a federal court denied a defendant’s motion to dismiss and

granted the plaintiffs' class certification motion in a challenge to the U.S. Census Bureau’s

consideration o f arrest and conviction records in its hiring process. 28 F. Supp. 3d. 222, 254-55

(S.D.N.Y. 2014): see also Rogers v. Pearland Indep. Sch. Dist., 827 F.3d 403 (5th Cir. 2016)

(considering, but granting summary judgment on. pro se plaintiffs claims that defendant’s hiring

policy related to felony convictions resulted in an improper disparate impact on people o f color

pursuant to Title VII).

that such policies violate Title VII. as they must, when they have a disparate impact

on people of color and are not job related and consistent with business necessity.

C. The Guidance Is Entitled to Deference.

As discussed above, the Guidance reflects the EEOC’s longstanding and

reasonable interpretation of Title VII and federal jurisprudence. On this point, and

in the event that this Court reaches the merits, Amici underscore that the EEOC’s

interpretation of Title VII, as embodied in the Guidance, is entitled to Skidmore

deference. Skidmore v. Swift & Co., 323 U.S. 134, 140 (1944); see also EEOC v.

Com. Office Prod. Co., 486 U.S. 107, 115 (1988) (“EEOC’s interpretation of Title

VII, for which it has primary enforcement responsibility . .. need only be reasonable

to be entitled to deference.”). Indeed, a recent district court concluded that the

Guidance was worthy of such deference. See Guerrero v. Cal. Dep’t o f Corrs. &

Rehab., 1 19 F. Supp. 3d 1065, 1079 (N.D. Cal. 2015), a ff’d in part, rev’d in part

and remanded, No. 15-17001,2017 WL 2963531 (9th Cir. July 12, 2017) (holding

the Guidance is “entitled to deference because thoroughness is clearly evident in its

consideration, its reasoning is valid, and it is consistent with earlier

pronouncements.”).

IN. EMPLOYMENT POLICIES THAT CATEGORICALLY

EXCLUDE INDIVIDUALS WITH FELONY AND OTHER

CONVICTION RECORDS ARE COUNTERPRODUCTIVE IN

EVERY RESPECT.

Finally, Amici write to situate this case in a real-world context. Barriers to

employment for people with records serve none of us well. These individuals form

a significant share of the U.S. population: across the country, more than 70 million

people—or nearly 1 in 3 adults—have an arrest or conviction record, and 700,000

people re-enter their communities following a term of incarceration each year.7 * In

Texas, which has one of the highest rates of incarceration in the world* nearly

164,000 individuals are behind bars,9 and 375,000 people are under community

supervision, including parole and probation.10 In 2016 alone, more than 76,000

people were released from Texas incarceration to rejoin their communities.11 All

told, across the state, more than 14 million people have an arrest or a conviction

7 Anastasia Christman & Michelle Natividad Rodriguez, Nat'l Emp't Law Project, Research

Supports Fair Chance Policies 1 & n.l (Aug. 1.2016). http://bit.ly/lsk48Nn; see also IJ.S. Dep't

of Justice, Bureau o f Justice Statistics. Survey o f State Criminal History Information Systems,

2016: A Criminal Justice Information Policy Report. Table 1 (Feb. 201 8), https://bit.ly/2pnzMKx.

s Peter Wagner & Wendy Sawyer. Prison Policy Initiative, States o f Incarceration: The Global

Context 201S (June 201 8). https://bit.ly/2JwCN7e.

9 E. Ann Carson. U.S. Bureau o f Justice Statistics. Full Report, Prisoners in 2016. at 4 (Aug. 2 0 1 8).

https://bit.Iy/2qUGY4Y.

111 Tex. Dep't o f Criminal Justice. Statistical Report Fiscal Year 2016 6. http://bit.ly/2hPaQvo.

11 Carson, supra note 9. at I 1.

http://bit.ly/lsk48Nn

https://bit.ly/2pnzMKx

https://bit.ly/2JwCN7e

https://bit.Iy/2qUGY4Y

http://bit.ly/2hPaQvo

record,12 * approximately 2 million people have a felony record, and more than

670,000 people have a prison record.12.

But these already large numbers are likely to grow, as more than one million

Texans are arrested, for the first time, every year.14 These trends— decades in the

making— have landed the most direct blow to Black and Latino communities, largely

due to the widely discredited “war on drugs” and the era of mass incarceration.1"

Nationally, Black individuals are arrested at a rate that is two times their proportion

of the general population,16 such that, overall, 1 in 3 Black men can expect to go to

prison in their lifetime.17 Moreover, 1 in 87 working-age white men are currently in

12 Survey o f Slate Criminal History Information Systems, supra note 7, at Table 1.

Michael Massoglia. Sarah K.S. Shannon. Jason Schnittker. Melissa Thompson, Christopher

IJggen, & Sara Wakefield, The Growth. Scope, anti Spatial Distribution o f People with Felony

Records in the United States, 1948 to 2 0 /0 (Demography, Vol. 54, Sept. 2017),

https://bit.ly/2CH25NM (The estimates cited, which span from 1980-2010, are based on an

unpublished dataset provided to NELP by the authors o f the paper. Raw numbers are estimates

based on life table analysis, not a census-like enumeration.)

14 Helen Gaebler, Criminal Records in the Digital Age: A Review o f Current Practices and

Recommendations fo r Reform in Texas 4 (William Wayne Justice Ctr. for Public Interest Law,

Uni v. o f Tex. School of Law, Mar. 2013), http://bit.ly/2yOAwej.

15 See. e.g.. Exec. Office o f the President. Economic Perspectives on Incarceration and the

Criminal Justice System 27-30 (Apr. 2016), http://bit.ly/2yOVMko; Michelle Alexander, The New

Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age o f Colorblindness (The New Press 2010).

16 Compare I:ed. Bureau o f Investigation, Crime in the United States, 2016: Table 21A (2017),

https://bit.ly/2gqjj4N (noting 26.9% of 2016 arrests were o f Black or African American people),

with U.S. Census Bureau. Comparative Demographic Estimates, https://bit.ly/2NZnONt

(approximately 13% of the U.S. population was Black or African American in 2016).

17 The Sentencing Project. Trends in U.S. Corrections 5 (June 2018). https://bit.ly/2Cw7pUl.

14

https://bit.ly/2CH25NM

http://bit.ly/2yOAwej

http://bit.ly/2yOVMko

https://bit.ly/2gqjj4N

https://bit.ly/2NZnONt

https://bit.ly/2Cw7pUl

prison or jail, compared with 1 in 36 Hispanic men and 1 in 12 Black men of the

same age range.Is More than 60% of people in prison today are people of color.14

Texas is not immune from the racial disparities that permeate the criminal

justice system: Black Texans constitute 27% of drug arrests and 36% of the state

prison and jail population; yet they make up only 11% of the state's adult

population.* * * 20 In light of these statistics, employment policies that ban individuals

with conviction records from securing jobs, which Texas thus far unsuccessfully has

sought court sanction of through this litigation, potentially harm millions of Texans

and disproportionately harm communities and individuals of color.

A. Policies that Render Employment Unattainable for People with

Records Weaken Onr Economy.

Public policies that exclude people with records from employment represent

a triple threat to individual workers, employers, and the economy.

At the individual level, the importance of keeping people who have been

involved in the criminal justice system connected to the workforce cannot be

overstated because the stigma associated with a conviction record—even for minor

offenses- is difficult to wash away, particularly in the employment context.

According to one recent study, the unemployment rate in 2008 (the most recent year

lx Bruce Western & Becky Pettit. Pew Charitable Trusts, Collateral Costs: Incarceration's Effect

on Economic Mobility 4 (2010). http://bit.ly/) YjcAau.

11 Ira n is in U.S. Corrections, supra note 17. at 5.

20 See. e.g ., Gaebler. supra note 14. at 10.

15

http://bit.ly/

for which data are available) of formerly incarcerated people was nearly five times

higher than the general unemployment rate, and even higher than the worst years of

the Great Depression.21 This should not be entirely surprising: today, nearly 9 in 10

employers conduct background checks on some or all job candidates.22 * When these

background checks reveal a record, the applicant's job prospects plummet: the

callback rate for white applicants drops by half, from 34% to 17%, and by almost

two-thirds, from 14% to 5%, for Black candidates.22. This is not news in Texas. The

Legislature has recognized that job seekers with conviction records receive less than

half as many job offers as other applicants.24 *

Even for individuals who are able to find work following release, there is a

price to be paid, as a history of incarceration operates as a lifelong drag on economic

security. Formerly incarcerated men can expect to work nine fewer weeks per year

and earn 40% less annually, for an overall loss of $179,000 even before the age of

50.2:1 In the year after an incarcerated father is released, family income drops by 15%

2 Lucius Couloute & Daniel Kopf, Prison Policy Initiative, Out o f Prison & Out o f Work:

Unemployment Antony Formerly Incarcerated People (July 2 0 1 8), https://bit.ly/2Jbib0t.

22 Soc'y for 1 tuman Res. Mgmt.. Background Checking— The Use o f Criminal Background Checks

in Hiring Decisions 3 (Jul. 19. 2012). http://bit.ly/2mhlrzh.

Devah Pager. The Mark o f a Criminal Record, 108 Am. J. Soc. 937. 955-58 (Mar. 2003).

http://bit.ly/IvNQBJk.

24 Senfronia Thompson. Judiciary & Civ. Juris. Comm. Rep.. Bill Analysis o f H.B. / 188 (2013).

http://bit.ly/2ijNbUb.

24 Western & Pettit, supra note I 8. at 11-12.

16

https://bit.ly/2Jbib0t

http://bit.ly/2mhlrzh

http://bit.ly/IvNQBJk

http://bit.ly/2ijNbUb

relative to pre-incarceration levels.26 People with records also are often excluded (on

account of state law) from occupations that require a license to work, which tend to

be some of the fastest growing and highest paying careers.27 * This exacerbates

income inequality: the wage advantage enjoyed by licensed workers relative to

comparable unlicensed workers increases with age, rising from about $1.60 per hour

at age 25 to $3.50 per hour at age 64.2S That same study also indicates that “[bjecause

employers tend to pay lower wages to workers with felony convictions, a licensing

requirement that bans those with criminal records can produce a larger wage

premium by separating those with convictions from those without them.”29 * In other

words, employment policies of the sort that Texas has enacted make a bad problem

worse.

Such policies also disadvantage employers, who are left with a smaller pool

of qualified workers. An emerging body of research demonstrates that people with

records make good employees. One study found that employees with criminal

records are less likely to leave voluntarily, generally have a longer tenure, and are

26 Id. at 21.

27 Beth Avery & Michelle Natividad Rodriguez, Nat'l Emp‘t Law Project, Unlicensed and

Untapped: Removing Barriers to State Occupational Licenses fo r People with Records 1 1 (April

2016), https://bit.ly/2Mm53af (noting that Texas has more than 100 occupational license laws that

automatically disqualifies people with records.)

2X Ryan Nunn. The Brookings Institution, How Occupational Licensing Matters for Wages and

Careers. (Mar. 2018). https://brook.gs/2oQwcJ5

27 Id.

17

https://bit.ly/2Mm53af

https://brook.gs/2oQwcJ5

no more likely than people without records to be terminated involuntarily.'° Another

study of individuals with a felony record serving in the U.S. military found that they

were promoted more quickly and to higher ranks than other enlistees and were no

more likely than service members without records to be discharged for negative

reasons.’1 Amicus Ms. Harrison’s post-conviction employment record— as a

dedicated professional for 28 years with the City of Dallas and thereafter as a home

health aide for several years— -bolsters the conclusion that this research supports.

Moreover, these consequences, which How directly from policies excluding

people with records from employment, accrue and impair overall economic vitality.

Specifically, the stigmatization of people with felony records effectively reduces the

annual U.S. gross domestic product by an estimated $78 to $87 billion.* 32 Under these

punitive policies, taxpayers lose as well. A 201 1 study found that putting just 100

formerly incarcerated persons back to work increased their lifetime earnings by $55

million, their income tax contributions by $1.9 million, and government sales tax

revenues by $770,000, while saving more than $2 million annually by keeping them

,0 Dylan Minor. Nicola Persico & Deborah M. Weiss, Criminal Background and Job

Performance? Evidence from Am erica's Largest Employer 2. 14 (May 1. 2017).

http://bit.ly/2vJT5jR.

11 Jennifer Lundquist. et ah. Does a Criminal Past Predict Worker Performance? 2 (Dec. 2. 2016)

(unpublished manuscript), http://bit.ly/2lloRle.

32 Cherrie Bucknor & Alan Barber, Ctr. for Econ. & Policy Research, The Price We Pay: Economic

Costs o f Barriers to Employment for Former Prisoners and People Convicted o f Felonies 1 (June

2016). http://bit.lv/2atNJBu (relying on 2014 data).

18

http://bit.ly/2vJT5jR

http://bit.ly/2lloRle

http://bit.lv/2atNJBu

out of the justice system.33 * * Another study estimated that increasing employment for

individuals released from Florida prisons by 50% would save $86 million annually

in costs related to future recidivism.vt

B. Policies that Render Employment Unattainable for People with

Records Undermine Public Safety.

Prohibitions against hiring individuals with conviction records, such as those

implemented by Texas, do not make communities safer. To the contrary, empirical

evidence shows that employment reduces crime.’'' Indeed, research published in

2011 revealed that employment was the single most important influence on reducing

recidivism by the formerly incarcerated subjects of the study; two years after release,

nearly twice as many employed individuals had avoided another interaction with the

criminal justice system when compared with their unemployed counterparts.36

It also matters—from a public safety perspective—that people with records

have access to good-paying jobs because higher wages translate to lower recidivism.

One study calculated that the likelihood of re-incarceration was 8% for those earning

” Econ. League of Greater Phila., Economic Benefits o f Employing Formerly Incarcerated

Individuals in Philadelphia 11-13. 18 (Sept. 201 1). http://bit.ly/2m2dei3.

’4 Am. Civil Liberties Union, Back to Business: How Hiring Formerly Incarcerated Job Seekers

Benefits Your Company 10 (2017), http://bit.ly/2sforzk (citing a study finding that providing job

training and employment to previously incarcerated individuals in the State o f Washington

returned more than $2,600 to taxpayers).

° See, e.g., Chrystal S. Yang, Local Labor Markets and Criminal Recidivism. 147 J. Pub. Econ.

16 (Dec. 2016). http://bit.ly/2zilSLQ (finding that releasing incarcerated individuals into a local

labor market with lower unemployment and higher wages decreased the risk o f recidivism).

■’6 Mark T. Berg & Beth M. Huebner, Reentry and the Ties that Bind: An Examination o f Social

Ties, Employment, and Recidivism. 28 Just. Q. 382, 397-98 (Apr. 201 1). http://bit.ly/2kirpkj.

19

http://bit.ly/2m2dei3

http://bit.ly/2sforzk

http://bit.ly/2zilSLQ

http://bit.ly/2kirpkj

more than $10 per hour, 16% for those earning less than $7 per hour, and 23% for

those who remained unemployed.37 * Public safety is not advanced by exclusionary

hiring policies such as those that Texas defends.

C. Policies that Render Employment Unattainable for People with

Records Come at the Expense of Communities and Families.

Blanket exclusions of people with felony and other conviction records harm

families—men, women, and children—all across the State of Texas. Today, nearly

half of all children in America have at least one parent with a record, which on

account of the counterproductive policies that Texas maintains necessarily means

that the damaging impacts of a record touch multiple generations.lS In the context of

one family, an incarcerated parent is has devastating effects. But in the aggregate,

mass incarceration destabilizes entire communities; more than 120,000 mothers and

1.1 million fathers are behind bars across the United States.39 When these individuals

return to their communities, economic strife is the natural result of state policies that

dangle employment out of reach. For example, interviews with family members of

formerly incarcerated men revealed that 83% had provided the recently released

person with financial support, half described providing this support as “pretty or very

'7 Christy Visher. et ah. Urban Inst., Employment after Prison: A Longitudinal Study o f Releasees

in Three States. 8 (October 2008), http://urbn.is/2yPIXI IN.

,s Rebecca Valias, et ah, Ctr. for Am. Progress, Removing Barriers to Opportunity for Parents

with Criminal Records and Their Children I (Dec. 2 0 1 5), http://ampr.gs/2g9hdWF.

'l) Western & Pettit, supra note 18. at 18.

2 0

http://urbn.is/2yPIXI

http://ampr.gs/2g9hdWF

hard." and 30% were facing “financial hardships."40 41 Policies that erect barriers to

employment for people with records take their toll at the worst possible time: the

very moment when these individuals are seeking to regain their footing.

Women in particular are hit hard by the kinds of hiring policies that Texas

trumpets. The incarceration of women surged by 700% between 1980 and 2014.11

This trend is compounded by another harsh reality: “women with a prison record are

seen as having committed two offenses, one against the law and one against social

expectations of how women are supposed to behave.”42 This has been demonstrated

empirically, as one experimental study evidenced that nearly 60% of men with a

prison record would have been called back for a job interview, whereas only 30% of

women with the same record would have received such a callback.43

In sum, Texas advocates for counterproductive hiring bans at its own peril.

Individuals with meaningful job opportunities are more likely to succeed as thriving,

law-abiding, and contributing members of their families and communities.44

111 Rebecca L. Naser & Christy A. Visher, Family M em bers' Experiences with Incarceration and

Reentry. 7 W. Criminology Rev. 20. 26 (2006). http://bit.ly/2xjaOT2.

41 The Sentencing Project, Incarcerated Women and Girls 1 (Nov. 2015). http://bit.ly/2xXkccx.

42 Scott II. Decker, et ah, Nat'l Inst, o f Justice, Criminal Stigma. Race. Gender, and Employment:

An Expanded Assessment o f the Consequences o f Imprisonment fo r Employment 57 (Jan. 2014);

http://bit.ly/2w3mVTl.

43 Id.

44 Le'Ann Duran, et ah. The Council of State Gov'ts Justice Ctr.. Integrated Reentry and

Employment Strategies: Reducing Recidivism and Promoting Job Readiness 2 (Sep. 2013),

http://bit.ly/2gNND9F.

21

http://bit.ly/2xjaOT2

http://bit.ly/2xXkccx

http://bit.ly/2w3mVTl

http://bit.ly/2gNND9F

I). The Texas Legislature—Aware of the Damage to the Economy,

Public Safety, and Families Wrought by Its Policies— lias Begun

Taking Steps to Address Employment Barriers for Individuals with

Records.

In the proceedings below, the State of Texas touted the “over 300 ways" in

which a record can impact a person's “access to the privileges of everyday society.”

ROA. 1678. This misreads, or misrepresents, the Zeitgeist in Texas.

In some respects, Texas has begun to understand that removing obstacles to

employment for people with records is beneficial to the state. For example, in 2013,

with the backing of the Texas Association of Business, then-Governor Rick Perry

signed into law House Bill I 188, which was passed with near unanimous bipartisan

support in the Texas Legislature.4'1 The law encourages employers to hire qualified

applicants with records by limiting potential civil liability facing employers based

on employee misconduct; the law makes clear that negligent hiring lawsuits cannot

be based solely on an employee's conviction history. T he State Legislature also

amended the Texas Occupations Code nearly two decades ago to require licensing

authorities to consider several factors when deciding whether to grant certain

occupational licenses to people with conviction histories many of the same factors

contained in the Guidance.46

4:1 H.B. 1 1 88. 85th beg. (Tex. 201 7). http://bit.Iy/2hQmwOz; see also Maurice Chainmah. Business

Association Scores Victories on Criminal Justice Agenda, l ex. Trib.. May 23. 2013. 6:00 AM.

http://bit.ly/2wAODUh.

4(1 Compare Guidance § 6, with Tex. Occ. Code 53.022-53.023 (effective Sept. 1. 1999).

n

http://bit.Iy/2hQmwOz

http://bit.ly/2wAODUh

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, Amici respectfully request that this Court reverse

the district court's grant of partial summary judgment in favor of Texas and vacate

that court’s grant of injunctive relief.

Dated: September 12, 2018

Respectfully submitted,

s/ Leah C. Aden

Sherrilyn A. 11111

Janai S. Nelson

Samuel Spital

Leah C. Aden

Counsel o f Record

NAACPLEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York, New York 10006

Telephone: (212) 965-2200

Facsimile: (212) 226-7592

laden@naacpldf.org

Catherine Ruckelshaus

NATIONAL EMPLOYMENT LAW

PROJECT

90 Broad Street, 11th Floor

New York, New York 10004

Telephone: (212) 285-3025

Facsimile: (866) 665-5705

cruckelshaus@nelp.org

Philip Hernandez

NATIONAL EMPLOYMENT LAW

PROJECT

2030 Addison Street, Suite 3 10

Berkeley, California 94704

2 3

mailto:laden@naacpldf.org

mailto:cruckelshaus@nelp.org

Telephone: (510) 982-5945

Facsimile: (866) 665-5705

phernandez@nelp.org

Edward B. Cloutman 111

CLOUTMAN & CLOUTMAN. L.L.P.

3301 Elm Street

Dallas, Texas 75226

Telephone: (214) 939-9222

Facsimile: (214) 939-9229

crawfish 1 l@prodigy.net

Robert H. Stroup (N.Y. Bar No. 2824712)

Dana Lossia (N.Y. Bar No. 706482)

LEVY RATNER, P.C.

80 Eighth Avenue

New York, New York 10011

Telephone: 212.627.8100

Facsimile: 212.627.8182

rstroup@levyratner.com

Counsel for Amici Curiae

2 4

mailto:phernandez@nelp.org

mailto:l@prodigy.net

mailto:rstroup@levyratner.com

APPENDIX

List of Amici Curiae

Amicus curiae Beverly Harrison resides in Dallas, Texas. She is a 62-year-

old Black woman, mother, and grandmother who retired from the Dallas City

Marshal’s Office in 2009 after 28 years of service to the City of Dallas. Ms. 1 Iarrison

has continued to work since her retirement to serve her community and supplement

her income, including by serving as a certified nursing assistant and home health

aide between 2009 and 2013 and working as a nursing attendant beginning in 2017.

Until mid-September 2017, Ms. Harrison worked for the Dallas Independent School

District as a school cafeteria employee.

In 2013, Ms. Harrison applied for a job with Dallas County Schools (“DCS”)

as a school crossing guard or bus monitor. Ms. Harrison received a conditional offer

of employment from DCS and began work as a school crossing guard. After eight

days on the job, however, DCS terminated Ms. Harrison’s employment because of

an entry that appeared on her background check report. In 1975, when she was 19

years old, Ms. Harrison pleaded no contest to the offense of aggravated assault, a

third-degree felony, and was sentenced to five years of probation. However, in 1977,

after two years of satisfactory compliance with the terms of her probation, the Dallas

County Criminal Court issued an order discharging Ms. Harrison from probation

early, setting aside the judgment of conviction, and “releasing her] from all

penalties and disabilities resulting from the Judgment of Conviction.” In the more

A-1

than 40 years since then. Ms. i larrison has never been convicted of a crime.

Nonetheless, the entry from 1975 has rendered her ineligible to secure employment

with DCS. DCS's denial of employment to Ms. Harrison, based on her decades-old

conviction record, is the basis of a pending complaint with the EEOC alleging a

violation of Title VII. Moreover, Ms. Harrison has been barred from other

employment in Texas due to her criminal history. In 2017, Ms. Harrison learned that

a home health agency would not employ her after it conducted a background check,

even though, as above, she had already worked as a home health aide for several

years. Ms. Harrison has reasonable fear that her conviction record may continue to

render her ineligible for employment in Texas.

Amicus curiae the Texas State Conference of the NAACP (“Texas

NAACP”) is the oldest and one of the largest and most significant non-profit civil

rights organizations in the State of Texas that promotes and protects the rights of

Black Americans and other people of color. With over 70 adult branches across

Texas and dozens more youth units, it has thousands of members who reside in every

region of the state. Nationally, the NAACP has worked for over ten years to reduce

barriers to employment for those with criminal records, advocating for “ban the box”

laws and policies, engaging national employers, and educating communities across

the country. Following this national directive, the Texas NAACP and its branches

have worked to eliminate employers’ categorical bans on hiring applicants with

A-2

felony convictions and other barriers faced by people with conviction and arrest

records, including Texas NAACP members and other people of color. For example,

during legislative sessions, the Texas NAACP has advocated for individuals with

records in various ways, including by expending resources and time by staff and

members lighting back against efforts to preempt fair chance hiring ordinances;

advocating for Senate Bill 578 (2015), which would have required the Texas

Department of Criminal Justice to provide comprehensive, county-specific reentry

and reintegration resources to individuals released from prison; and advocating for

House Bill 1510 (2015), which would have increased housing options for individuals

with conviction records. Where Texas defends policies that categorically deny jobs

to people with convictions, the Texas NAACP is forced to redirect resources away

from its affirmative reentry work of conducting job searches and providing training

for individuals and reallocate those resources toward helping its members and

constituents secure employment and defending and enforcing antidiscrimination

statutes such as Title VII, which renders such categorical bans illegal.

Amicus curiae the NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

(“LDF”) is a non-profit, non-partisan law organization, founded in 1940 under the

leadership of Thurgood Marshall to achieve racial justice and ensure the full, fair,

and free exercise of constitutional and statutory rights for Black people and other

communities of color. LDF has been involved in precedent-setting and other

important litigation challenging employment discrimination before federal and state

courts. See, e.g.. Lewis v. City o f Chicago, 560 U.S. 205 (2010); Hithon v. Tyson

Foods. Inc., 144 F. App'x 795 (1 1th C'ir. 2005); Patterson v. McLean Credit Union,

491 U.S. 164 (1989); Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976);

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975); Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971). In the unanimous decision in Griggs v. Duke Power Co., which

LDF litigated, the U.S. Supreme Court recognized the disparate impact theory of

liability in the employment context. LDF also challenges policies that exclude

individuals with criminal records from jobs. See. e.g., Waldon v. Cincinnati Pub.

Sells., 941 F. Supp. 2d 884 (S.D. Ohio 2013) (denying defendants' motion to dismiss

a disparate impact case alleging that Black former public school employees were

terminated for having been convicted of specified crimes under Ohio law); Mem. &

Op., Little v. Wash. Metro Area Transit Auth. (WMATA) at 1,46-47, No. l:14-cv-

01289-RMC (D.D.C. Apr. 18, 2017), ECF No. 1 86 (certifying a class of affected job

applicants with respect to plaintiffs’ claim that WMATA’s criminal background

check policy is facially neutral, but has a disparate impact on Black applicants); see

also Class Lawsuit Settlement Agreement, WMATA, No. 1; 14-cv-01289-RMC

(D.D.C. Dec. 20. 2017), ECF No. 230-1 (settling claims of individuals and class

representatives terminated, suspended, or denied employment as a result of the

application of a criminal background screening policy). LDF' contributed to the

A-4

efforts that led a bipartisan EEOC to adopt the Guidance in 2012. At the heart of this

case is Texas's challenge to the legality of the Guidance, which memorializes case

law, like Griggs, and decades of EEOC policies that show that categorical bans on

hiring people w ith convictions, such as the ones that Texas has asked be declared

lawful, may violate Title Vll to the extent that they disproportionally impact Black

people and other protected groups and are not job-related and consistent with

business necessity.

Amicus curiae the National Employment Law Project, Inc. (“NELP”) is a

non-profit legal research and advocacy organization with 45 years of experience

advancing the rights of low-wage workers and those struggling to access the labor

market. NELP seeks to ensure that vulnerable workers across the nation receive the

full protection of employment laws. Specializing in the employment rights of people

with arrest and conviction records, NELP has helped to lead the national movement

to restore fairness to employment background checks. NELP works with allies in

Texas and across the country to promote enforcement of antidiscrimination laws,

like Title VII, and to reduce the barriers to employment faced by workers with

records, such as categorical bans on hiring people with felony conviction histories

or other records. NELP has litigated and participated as amicus in numerous cases

addressing the rights of workers with records. Like LDF, NELP was a leader in the

efforts to encourage a bipartisan EEOC to adopt the 2012 Guidance. Both LDF and

A-5

NHLP served as amici in Guerrero v. Cal. Dep't of Cons. & Rehab., arguing that

the court should rely on the Guidance in determining whether particular employers'

criminal background check policies unfairly exclude applicants of color. 119 F.

Supp. 3d 1065 (N.D. Cal. 2015), aff'd in part, rev'd in part and remanded, No. 15-

17001,2017 WL 2963531 (9th Cir. July 12, 2017).

A-6

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

Pursuant to 5th Circuit R. 32, the undersigned certifies this brief complies with

the type-volume limitations.

1. EXCLUSIVE OF THE EXEMPTED PORTIONS IN 5TH CIR. R. 32. THE

BRIEF CONTAINS (select one):

A. 5825________words, OR

B. N/A________ lines of text in monospaced typeface.

2. THE BRIEF HAS BEEN PREPARED (select one):

A. in proportionally spaced typeface using:

Software Name and Version: Microsoft Word v. 2016 in (Typeface Name

and Font Size): Times New Roman 14 pt„ OR

B. in monospaced (nonproportionally spaced) typeface using: N/A

Typeface name and number of characters per inch:

3. IF THE COURT SO REQUESTS, THE UNDERSIGNED WILL PROVIDE

AN ELECTRONIC VERSION OF THE BRIEF AND/OR A COPY OF THE

WORD OR LINE PRINTOUT.

4. THE UNDERSIGNED UNDERSTANDS A MATERIAL

MISREPRESENTATION IN COMPLETING THIS CERTIFICATE OR

CIRCUMVENTION OF THE TYPE-VOLUME LIMITS IN 5TH CIR. R. 32,

MAY RESULT IN THE COURTS STRIKING THE BRIEF AND

IMPOSING SANCTIONS AGAINST THE PERSON SIGNING THE

BRIEF.

s/ Leah C. Aden

Leah C. Aden

C-l

CERTIFICAT E OF SERVICE AND EEECTRONIC SUBMISSION

On September 12, 2018, this brief was served via CM/ECF on all registered

counsel and transmitted to the Clerk of the Court. I hereby certify that: (1) required

privacy redactions have been made; (2) the electronic submission of this document

is an exact copy of the corresponding paper document; and (3) the document has

been scanned for viruses with the most recent version of a commercial virus scanning

program and is free of viruses.

s/ Leah C. Aden

Leah C. Aden

C - 2