Robinson v FL Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1963

70 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Robinson v FL Brief for Appellants, 1963. 718b54b7-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b5382975-10cc-4c38-bbb6-52be9a098e0b/robinson-v-fl-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

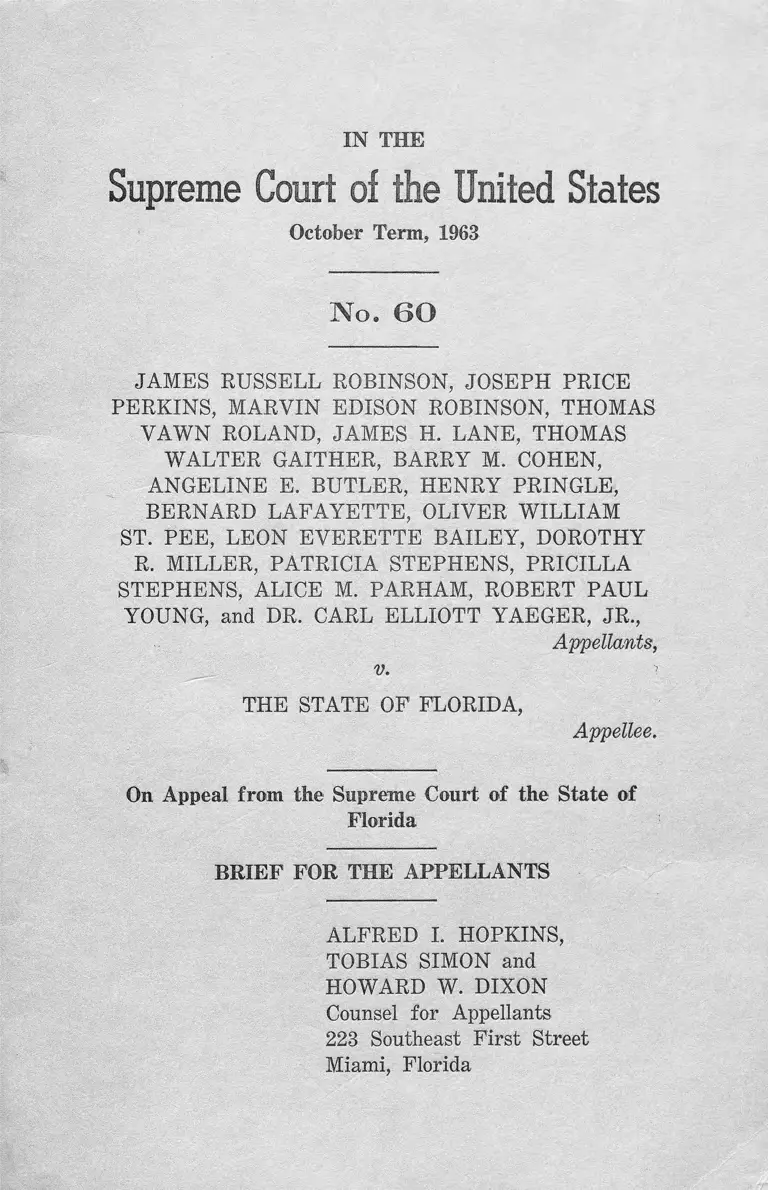

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1963

No. 6 0

JAMES RUSSELL ROBINSON, JOSEPH PRICE

PERKINS, MARVIN EDISON ROBINSON, THOMAS

VAWN ROLAND, JAMES H. LANE, THOMAS

WALTER GAITHER, BARRY M. COHEN,

ANGELINE E. BUTLER, HENRY PRINGLE,

BERNARD LAFAYETTE, OLIVER WILLIAM

ST. PEE, LEON EVERETTE BAILEY, DOROTHY

R. MILLER, PATRICIA STEPHENS, PRICILLA

STEPHENS, ALICE M. PARHAM, ROBERT PAUL

YOUNG, and DR. CARL ELLIOTT YAEGER, JR.,

v.

Appellants,

THE STATE OF FLORIDA,

Appellee,

On Appeal from the Supreme Court of the State of

Florida

BRIEF FOR THE APPELLANTS

ALFRED I. HOPKINS,

TOBIAS SIMON and

HOWARD W. DIXON

Counsel for Appellants

223 Southeast First Street

Miami, Florida

I N D E X

Page

Opinion below ______________________________ 1

Jurisdiction ________________________________ 2

Question presented __________________________ 2

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved__ 3

Statement of the case_________________ 4

Summary of Argument

Argument:

I The participation by the police and courts

below in arresting and convicting Appel

lants for alleged violation of Florida Stat

utes § 509.141, in aid of the restaurant’s

policy of racial discrimination, constituted

state enforcement of racial discrimina

tion and, consequently, a denial of Appel

lants’ rights to the equal protection of the

laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment. _______________________ 6

II Apart from the participation of the po

lice and the state courts herein, the dis

criminatory action of Shell’s City itself

constituted state action, since by virtue

of the Florida restaurant licensing law,

Florida Statutes Chapter 509, together

with the regulations promulgated there

under, the State has, within the meaning

of the Burton v. Wilmington Parking Au

thority, “so far insinuated itself into a po

sition of interdependence” with restau

rants “that it must be recognized as a

joint participant in the challenged ac

tivity.” ____________________________

III The racial discrimination practiced by

Shell’s City is engendered by racial cus

toms prevalent in Miami and throughout

the State of Florida, and the pressures of

state and local customs which were

brought to bear upon the Appellants, nec

essarily constituted a denial by state ac

tion of Appellants’ rights to the equal pro

tection of the laws within the meaning of

INDEX (cont.)

the Fourteenth Amendment.__________ 27

Conclusion _________________________________ 30

Page

19

Appendix App. 1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases: Page

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir., 1961) 24

Barrows v. Jackson,, 846 U.S. 249; 97 L.Ed, 1586;

73 S. Ct. 1031 (1953)___________________ 5,7

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454; 5 L.Ed. 2d 206;

81 S. Ct. 182 (1960)_____________________ 7

Burton V. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S.

715; 6 L.Ed. 2d 46; 81 S.Ct. 856 (1961) _ 6, 9,18, 23

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296; 84 L.Ed.

1213; 60 S. Ct. 900 (1940)________________ 17

Commonwealth v. Alger, 7 Cush. 53; 61 Mass. 53—_ 1.5

District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Com

pany, Inc., 346 U.S. 100; 97 L.Ed. 1480; 73

S.Ct. 1007 (1952)_______________ 15

Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1; 91 L.

Ed. 711; 67 S. Ct. 504 (1947)_____________ 17

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157; 7 L. Ed. 2d 207;

82 S. Ct. 248 (1961)___________________ 7,22,29

Hirabayashi v. United States,. 320 U.S. 81; 87 L.Ed.

1774; 63 S. Ct. 1375 (1943)_______________ 17

Hurdv. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24; 92 L.Ed. 1187; 68 S.Ct.

847 (1948) _____________________________ 7,14

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267; 31 Law Week

4476 (1963) ___________________________ 13

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED (conk)

Cases: Page

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501; 90 L.Ed. 265; 66

S. Ct. 265 (1946)________________________ 16,25

McGoivan v, Maryland, 336 U.S. 420; 6 L.Ed. 2d

393; 81 S. Ct. 1101 (1961)_______________ 17

Miller Y. Schoene, 276 U.S. 272; 72 L.Ed. 568; 48

S.Ct. 246 (1928) _______________________ 16

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370; 26 L. Ed. 567

(1881) ________________________________ 29

Nebbia v. New York, 291 U.S. 502; 78 L.Ed. 940;

54 S. Ct. 505 (1934)_____________________ 15

Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U.S. 319; 82 L.Ed. 288;

58 S. Ct. 149 (1937)_____________________ 17,19

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244; 31

Law Week 4475 (1963)__________________ 7,29

Public Utilities Commission V. Poliak, 343 U.S. 451;

97 L.Ed. 1068; 72 S. Ct. 813 (1952)________ 24

Robinson v. State,. 144 So. 2d 811 (Fla., 1962)----- 1

Rylands v. Fletcher, 1868, L.R. 3 H.L. 330, 338----- 15

School District of Abington V. Schempp, 374 U.S.

203; 32 Law Week 4683 (1963)___________ 13,18

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1; 92 L.Ed. 1161; 68

S.Ct. 836 (1948)_________________ _____ 5,7

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED (cont.)

Cases: Page

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649; 88 L.Ed. 987; 64

S. Ct. 757 (1944)_______________________ 25

Southern Pacific Co. v. Arizona, 325 U.S. 761; 89

L.Ed. 1915; 65 S. Ct. 1515 (1945)_________ 17

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville Railroad Company,

323 U.S. 192; 89 L.Ed. 173; 65 S. Ct. 226

(1944) ________________________________ 26

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461; 97 L.Ed. 1152; 73

S. Ct. 809 (1953)________________________ 28

The Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3; 27 L.Ed. 835;

3 S. Ct. 18 (1883)_______________________ 22,27

Valle v. Stengle, 176 F. 2d 697 (3rd Cir., 1949)_ 10

Constitutional Provisions, Statutes and Regulations:

Page

Federal Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment, § 1_ 3

R. S. § 1977 (42 U.S.C.A. § 1981)______________ 11

Florida Constitution, Declaration of Rights, § 2__ 30

Florida Constitution, Article XII, § 12__________ 28

Florida Constitution, Article XYI, § 24_________ 28

Florida Statutes, §§ 352.03 - 353.18_____________ 28

Florida Statutes, Chapter 509_________________ 20-22

Florida Statutes, Chapter 608_________________ 22

Florida Statutes, §§ 741.11 -741.16____________ 28

Florida Statutes, §§ 798.04 and 798.05__________ 28

Florida Statutes, §§ 948.01(1) and 948.01(3)____ 4

Florida Statutes, §§ 950.05-950.08_____________ 28

Florida Administrative Code, Chapter 175_______ 21

Text:

Henkin: “Shelley v. Kraemer: Notes for a Revised

Opinion”, 110 U. of Pa. L.R. 473 (1962)____ 12

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1963

No. 6 0

JAMES RUSSELL ROBINSON, JOSEPH PRICE

PERKINS, MARVIN EDISON ROBINSON, THOMAS

YAWN ROLAND, JAMES H. LANE, THOMAS

WALTER GAITHER, BARRY M. COHEN,

ANGELINE E. BUTLER, HENRY PRINGLE,

BERNARD LAFAYETTE, OLIVER WILLIAM

ST. PEE, LEON EVERETTE BAILEY, DOROTHY

R. MILLER, PATRICIA STEPHENS, PRICILLA

STEPHENS, ALICE M. PARHAM, ROBERT PAUL

YOUNG, and DR. CARL ELLIOTT YAEGER, JR.,

Appellants,

v.

THE STATE OF FLORIDA,

Appellee.

On Appeal from the Supreme Court of the State of

Florida

BRIEF FOR THE APPELLANTS

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Florida is re

ported in 144 So. 2d 811. (R. 46) The opinion of the trial

court, delivered orally at the conclusion of the trial, is set

forth in the Record. (R. 36)

2

JURISDICTION

The State of Florida filed a criminal information

against Appellants on August 17, 1960, pursuant to Flor

ida Statutes § 509.141. (R. 1) Appellants were tried and

were found by the trial court to have violated said statute

and judgments were entered against them on August 26,

1960. (R. 36, 37) Appellants filed a Notice of Appeal to

the Circuit Court for the Eleventh Judicial Circuit in

and for Dade County, Florida, on September 21, 1960 (R.

8), and the judgments of the trial court were ultimately

affirmed by the Supreme Court of Florida in its Order

and Opinion filed September 19, 1962. (R. 46) Appellants

filed their Jurisdictional Statement herein on January

16, 1963, and this Court entered its Order Noting Prob

able Jurisdiction on June 10, 1963.

Jurisdiction of this Appeal is invoked pursuant to

28 U.S.C. § 1257(2).

QUESTION PRESENTED

Where a group of Negroes and white persons in asso

ciation with Negroes remain in a restaurant after the

manager has refused to serve them and has requested

them to leave the premises; and where the manager’s re

fusal to serve and his request to leave are based upon the

fact that the group comprises Negroes and white persons

in association with Negroes; and where the police, at the

manager’s request, arrest the group because of their re

fusal to comply with the manager’s request to leave the

premises; are the arrests and subsequent convictions of

the group for alleged violations of Florida Statutes

§ 509.141 in violation of the equal protection of the laws

3

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal

Constitution?

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS AND STATUTES

INVOLVED

1. § 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal

Constitution.

2. R. S. § 1977 (42 U.S.C.A. § 1981), which provides

that:

“All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State

and Territory to make and enforce contracts . . .

and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and

proceedings for the security of persons and prop

erty as is enjoyed by white citizens. . . . ”

3. § 2 of the Declaration of Rights of the Florida

Constitution, which provides that: “All political power is

inherent in the people.”

4. The following Sections of Chapter 509 of the

Florida Statutes, which are set forth in full in the Appen

dix hereto: § 509.012; § 509.032(1) ; § 509.092; § 509.141;

§ 509.211; § 509.221; § 509.241; § 509.261; § 509.271; and

§ 509.291 (App. 6-25).

5. Florida Statutes §§ 352.03-353.18; 741.11-741.16;

798.04 and 798.05; and 950.05-950.08, set forth in full in

the Appendix hereto. (App. 1-2; 26-31).

6. Florida Statutes § 948.01(1) and § 948.01(3),

set forth in full in the Appendix hereto (App. 28).

4

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The State of Florida filed an information against Ap

pellants pursuant to Florida Statutes § 509.141(3), (App.

8) which charged that on August 17, 1960, they entered

Shell’s City Restaurant in Miami, Florida, seated them

selves as guests at tables in the restaurant and unlawfully

remained in the restaurant after having been requested

by the management to leave, the management being of the

opinion that if Appellants were served it would be detri

mental to the restaurant. (R. 1-2) Trial was held in the

Criminal Court of Record in and for Dade County, Flor

ida, on August 26, 1960. Following the presentation of

the State’s case, Appellants moved for a judgment of ac

quittal, but their motion was denied. (R. 35) The Appel

lants presented no evidence. The trial court then entered

judgments pursuant to Florida Statutes, Chapter 948

(App. 28), wherein it ordered that adjudications of guilt

and the imposition of sentence be stayed, and placed Ap

pellants on probation. (R. 36-37)

The record contains no conflict as to the material

facts alleged in the information. The Appellants, com

prising both colored and white persons, entered the res

taurant and sat at several tables, and asked to be served.

The manager refused to serve them, and called the police.

A police officer arrived and the manager, accompanied

by the officer, went to each table and again requested Ap

pellants to leave, and they again refused. The police offi

cer then advised them to leave and when they did not, he

placed them under arrest. (R. 16, 17, 18, 23)

The manager stated that it was his opinion that the

presence of Appellants was detrimental to his business for

5

the reason that they were Negroes and white persons in

association with Negroes. (R. 22) The restaurant consti

tutes one of nineteen departments in the Shell’s City de

partment store, and the manager admitted that other

patrons were being served in the restaurant at this time,

and also admitted that it was not detrimental to the busi

ness for Negroes to purchase products in other parts of

the store. (R. 23, 24) Although Negroes are invited to

purchase in eighteen departments in the store, they are

not allowed in the nineteenth, the restaurant. (R. 29)

A vice-president of the store stated that Shell’s City’s

policy of not serving Negroes is based upon the customs,

habits and traditions of the majority of the white people

in the county and the state not to serve white and colored

people seated in the same restaurant and that if Shell’s

City tried “to break that barrier”, it “might have real

trouble”. (R. 29, 30)

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The actions of the police and the courts of the State

of Florida in evicting Appellants from the restaurant and

in arresting and convicting them for alleged violations of

Florida Statutes § 509.141 constituted state enforcement

of racial discrimination and a denial of Appellants’ rights

to the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment. Neither the State nor the restaurant

owner can claim that the discrimination was purely “pri

vate” inasmuch as the arrests, prosecution and convictions

were all effectuated by organs of state power. Shelley y.

Kraemer and Barrows v. Jackson, post.

Further, since restaurants under Florida law are sub

6

ject to the licensing, regulatory and supervisory authority

of the Florida Hotel and Restaurant Commission, they

operate as quasi-public instrumentalities of the State. Thus,

the State has, within the meaning of Burton v. Wilmington

Parking Authority, post, so far insinuated itself into a

position of interdependence with restaurants that the dis

criminatory practices cannot be deemed so purely private

as to fall outside the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Consequently, Shell’s City has the affirmative constitu

tional obligation to serve the public without discriminations

based upon race.

Finally, the discrimination practiced by Shell’s City

was the result of local racial customs, and the mass pres

sures of such customs, exerted by the people of Dade

County and the State of Florida, thus coercing the restau

rant to discriminate, constituted state action within the

meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment and in violation

thereof.

ARGUMENT

I

The participation by the police and courts be

low in arresting and convicting Appellants for

alleged violation of Florida Statutes § 509.141,

in aid of the restaurant’s policy of racial discrim

ination, constituted state enforcement of racial

discrimination and, consequently, a denial of Ap

pellants’ rights to the equal protection of the

laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

1. In order to narrow and define the issues involved

7

in this appeal, Appellants would first show to the Court

that unlike other “sit-in” cases recently decided by the

Court, (1) the issue here is not that of lack of evidence

to support a conviction for disorderly conduct or unlawful

assembly or the like, as in Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S.

157; 7 L.Ed.2d 207; 82 S.Ct. 248 (1961), and companion

cases; (2) we are not here confronted with any statute,

ordinance, or administrative policy expressly requiring

racial segregation in restaurants, as in Peterson v. City of

Greenville, and companion cases, 373 U.S. 244: 31 Law

Week 4475 (1963) ; and (3) there is no assertion that the

activities in question involve interstate commerce, as in

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454; 5 L.Ed.2d 206; 81 S.Ct.

182 (1960).

2. Appellants rely first upon Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U.S. 1, 22; 92 L.Ed. 1161, 1185; 68 S.Ct. 836 (1948),

where the Court held that:

“The Constitution confers upon no individual the

right to demand action by the State which results

in the denial of the equal protection of the laws

to other individuals. And it would appear beyond

question that the power of the State to create and

enforce property interests must be exercised

within the boundaries defined by the Fourteenth

Amendment.”

Accord: Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249; 73 S.Ct. 1031;

97 L.Ed. 1586 (1953). Cf. Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24; 92

L.Ed. 1187; 68 S.Ct. 847 (1948). In these cases, the Court

refused to permit an arm of government to protect or give

effect to a private party’s asserted contractual property

right, in the form of a restrictive covenant, where such

8

protection or assistance would have resulted in unlawful

racial discrimination. In the case at bar Shell’s City called

upon the police of Miami to evict Appellants from the res

taurant solely for the reason of racial discrimination.

Thereupon the police in conjunction with the office of the

State Attorney for Dade County, invoked the criminal

jurisdiction of the Florida judiciary, and this aggregation

of state authority succeeded in effectuating the restau

rant’s racial policy. Appellants, predicating their position

upon Shelley and Barrows, submit that the Court should

prohibit the public authorities of the State of Florida from

lending their coercive power to protect or effectuate Shell’s

City alleged “property right” to refuse to serve patrons

who are Negroes or in association with Negroes.

The State’s position appears to be that the restaurant

owner, as a “private party”, has the unfettered right to

select its customers and patrons by virtue of and in ac

cordance with Florida Statutes § 509.141. (App. 8) Sub

section (1) of the statute authorizes the restaurant owner

to remove or cause to be removed any guest “who, in the

opinion of the management, is a person whom it would be

detrimental to such . . . restaurant . . . for it any longer

to entertain.”1 Sub-section (3) provides that any guest

who shall remain in the restaurant after being requested to

leave shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be deemed

to be unlawfully within the restaurant. Sub-section (4)

provides that the management may call any law enforce

iA similar legislative assertion of the right to private choice is

contained in Florida Statutes § 509.09, which provides that:

“Public lodging and public food service establishments are declared

to be private enterprises and the owner or manager of public

lodging and public food service establishments shall have the right

to refuse accommodations or service to any person who is objec

tionable or undesirable to said owner or manager.”

9

ment officer to its assistance, who shall forthwith eject

such person from the premises.

§ 509.141 may be valid on its face, as it does not by

its terms define race as a criterion of undesirability, and

Appellants do not contest the State’s right to assist a res

taurateur in evicting patrons who refuse to leave where

their undesirability is predicated upon appropriate rea

sons other than race. If a Negro were boisterous, intoxi

cated, or improperly attired, the restaurateur and the po

lice would be justified in ejecting him, for these would be

criteria of undesirability unrelated to the patron’s race.

However, the State’s information did not charge, nor does

the record contain, any allegations or evidence that any

of the Appellants were unmannerly, or improperly attired,

or engaged in any disorderly conduct. It is clear from the

testimony of the managers that they considered Appellants

undesirable and their presence detrimental to the restau

rant’s business for one reason alone, namely, that they

were Negroes or persons in association with Negroes, Ac

cordingly, it is Appellants’ position that while the Statute

may be valid on its face, the State invalidly applied it in

the instant case by effectuating and enforcing racial dis

crimination. And the ruling of the Florida Supreme Court,

below, in permitting the application of the statute in this

case in effect authorized “discriminatory classification

based exclusively on color.” Stewart, J., concurring in

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, post, 365 U.S.

715, 727; 6 L.Ed.2d 45, 53.

The State’s argument that the restaurant owner, as a

“private party”, has the right to select its customers, even

on the basis of race, is sophistic. The entire transaction—

from its inception, when the management requested Ap

10

pellants to leave, to its conclusion, when the Appellants

were convicted—was programmed and consummated pur

suant to Florida Statutes § 509.141 and the statute was,

in practical effect, applied to them solely because they

are Negroes or were in association with Negroes. It is a

sophistry to suggest that the discrimination was “private”

when Appellants were arrested by police officers of the

City of Miami, were incarcerated in a public jail awaiting

trial, were prosecuted by the State Attorney’s office, and

were convicted of a criminal offense in a criminal court

and under and by virtue of the criminal statutes of the

State of Florida. The very participation of the office of

the Attorney General of the State of Florida in this appeal

further repudiates any notion that this is simply a “pri

vate” issue.

If, as in Shelley and Barrows, the civil sanctions of

injunction and common law judgments are not available

to one who would assert a property right for racial reasons,

then a fortiori the exercise of the public power in the form

of criminal sanctions should be prohibited. In the instant

case the State injected itself into the restaurant owner’s

affairs to the extent of carrying out a mass arrest, staging

a mass criminal trial and placing the Appellants in jeop

ardy of mass incarceration in the public jail. But for the

issue of race, this entire drama would not have been

enacted, and such blatant racial discrimination cannot be

characterized as simply a private affair when this formid

able arsenal of State power is brought to bear to enforce it.

The judgment below is also in direct conflict with the

decision of the Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit in

Valle v. Stengle,. 176 F.2d 697 (1949). Plaintiffs there

brought suit under the Civil Rights Acts alleging a denial

11

of equal protection of the laws. Their complaint alleged

that they were both Negroes and whites; and that the de

fendants, being the corporate owner of a private amuse

ment park, the individual managers thereof, and the local

chief of police, denied plaintiffs admission to the swim

ming pool therein and ejected them from the park on the

ground that their party contained Negroes. In sustaining

their complaint against a motion to dismiss the Court

stated that:

“ . . . the plaintiffs were denied equal protection

of the laws, within the purview of the Fourteenth

Amendment because they were Negroes or acting

in association with Negroes when they attempted

to gain admission to the pool at Palisade Park.

They, or some of them, were ejected from the

park, were assaulted and were imprisoned falsely,

as alleged in the complaint, because they were Ne

groes or were in association with Negroes, and

were denied the right to make or enforce con

tracts, all within the purview of and prohibited

by R. S. Section 1977”. 176 F.2d 697, 702.

The Court held that the right to solicit contracts may

not be violated by State action where such action is

prompted by the fact that the soliciting parties are Ne

groes or persons acting in association with Negroes. Ap

pellants here, like the plaintiffs in Valle, were denied the

right to trade with Shell’s City because of the fact that

they are Negroes or persons in association with Negroes.

R. S. § 1977, cited above, provides that:

“All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State

12

and Territory to make and enforce contracts

. . . and to the full and equal benefit of all laws

and proceedings for the security of persons and

property as is enjoyed by white citizens. . . . ”

3. Concern has been voiced by some writers2 that

if the rule in Shelley and Barrows be extended to cases

like the one at bar, then by further extension none could

discriminate in their own homes against unwanted persons

who happened to be Negroes, and that Negroes would

thereby be accorded a special status as privileged tres

passers. In reply, Appellants state first that it tortures

the imagination to conceive of a hypothetical case coming

to pass in which a private householder would invite the

entire public, or a substantial segment of it, to enter his

private premises on an otherwise indiscriminate basis,

but refuse to admit Negroes and solely because of their

race. Such a hypothetical case would involve not merely

the right to turn a Negro away from one’s door under

any circumstances; rather, this special case must posit a

householder inviting all persons similarly situated onto

his premises, but excluding Negroes and solely because of

their race. Such would indeed be a rare and extraordinary

occurrence, but even if it should eventuate, its social sig

nificance would be trivial when compared with the whole

sale discriminations in places of public accommodation

which occur daily and in hundreds of communities through

out the country. It hardly needs repeating that racial dis

crimination by restaurants, which are otherwise open to

the general public, constantly subject members of the Ne

gro minority to public humiliation and indignities, and

2For a scholarly analysis of Shelley, its consequences, and its de

tractors, see Henkin, “Shelley v. Kraemer: Notes for a Revised Opin

ion”, 110 U. of Pa. L.R. 473 (1962).

13

publicly proclaim them to be, in effect and en masse, in

ferior members of American society. Any such racial dis

crimination, as suggested above, by a private home-owner,

while manifesting a pathetic prejudice, would be an iso

lated event and would not subject its victims to the noto

rious humiliation occasioned by restaurant discriminations;

indeed, a Negro intruding upon the intimacy of a private

home would hardly command serious social concern.3

Further, to argue the applicability vel non of Shelley

and Barrows in the case at bar on the basis of the case of

the hypothetical homeowner would be to argue ignotum per

ingnotius and to lose touch with reality; the problem of

the private home-owner should therefore not control the

disposition of the actual case now before the Court. “It

is of course true that great consequences can grow from

small beginnings, but the measure of constitutional adjudi

cation is the ability and willingness to distinguish between

real threat and mere shadow.” Goldberg, J., concurring in

School District of Abington v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203; 31

Law Week 4683, 4715 (1963)

4. The circumstances in the case at bar are of criti

cal immediacy and the application of the principle involved

to places of public accommodation are of national impor

tance. The Shell’s City restaurant is located in a large de

partment store, its business purpose is to serve the public,

and it solicits the business of the public indiscriminately,

except in one regard—that of race. “Access by the public

is the very reason for its existence.” Douglas, J., concur

ring in Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267; 31 Law Week

4476, 4478 (1963). The scope of the indignities and dis

3Cf. Henkin, op. cit., pp. 498, 499.

14

criminations which are practiced thus becomes a measure

of their constitutional consequences. The issue, therefore,

viewed realistically, is one of reconciling the restaurant

owner’s asserted proprietary rights with the constitutional

guarantee of equal protection of the laws. Appellants con

tend that in this central issue that fundamental guarantee

of racial equality should and must prevail over the as

serted property right of private commercial choice. In

choosing between similar conflicting claims of constitu

tional and equitable preferences, this Court has heretofore

declared, in a related case, that the enforcement of re

strictive racial covenants is not only violative of constitu

tional and statutory guarantees, but is “contrary to the

public policy of the United States.” Hurd v. Hodge, supra,

334 U.S. 24, 34; 92 L.Ed 1187, 1195. That same public

policy should require an end to racial discrimination in

restaurants. Indeed, that same public policy was dramat

ically manifested on August 2, 1963 when Ambassador

Stevenson announced to the Security Council of the United

Nations that our government would end the sale of military

equipment to the Union of South Africa by the end of

1963, because of “the evil business of apartheid”. Ambas

sador Stevenson, in referring to the many manifestations

of apartheid in South Africa, including segregation in pub

lic accommodations, declared that “such indignities are an

anachronism that no progressive society can tolerate, and

the last vestige must be abolished with all possible speed.”4

With our public policy thus nobly proclaimed to the rest

of the world, it is inconceivable that, where the choice is

before us, we could assume a posture any less noble within

our own nation.

*The New York Times, August 3, 1963, p. 6.

15

5. The State begs the question when it asserts that

the restaurant owner has the “right” to select his cus

tomers on the basis of race. First, such “rights” as he may

possess and which are legally enforceable, derive their

operable force from the State, and the participation of the

State in this situation has already been discussed at length.

Second, the private use of private property has at com

mon law always been subject to a variety of judge-made

restrictions, and thus the hoary maxim, sic utere tuo, ut

alienum non laedas. In further illustration, it is a com

monplace of the common law that the use of one’s property

for a noxious purpose will subject one to civil liability for

maintaining a nuisance, and will also justify the exercise of

the State’s police power to terminate or control that use,

cf. Commonwealth v. Alger, 7 Cush. 53; 61 Mass. 53; and

strict liability, regardless of care, follows from the main

tenance on one’s property of an extraordinary hazard,

Rylands v. Fletcher, 1868, L. R. 3 H.L. 330, 338. Again,

one cannot deprive the community of the alienable use of

one’s own property in violation of the judge-made rules

against perpetuities and accumulations, and other exam

ples of common law restrictions abound in the field of fu

ture interests. Indeed, as a principle of federal constitu

tional law, a municipality may affirmatively prohibit

racial dismrimination by restaurants and provide criminal

sanctions for violations, and without doing constitutional

violence to the owners’ asserted rights of liberty and prop

erty. District of Columbia V. John R. Thompson Company,

Inc., 346 U.S. 100; 97 L.Ed. 1480; 83 S.Ct. 1007 (1952).

As the Court said in Nebbia v. New York, 291 U.S.

502, 525; 78 L.Ed. 940, 948; 54 S.Ct. 505 (1934) :

“Under our form of government the use of prop-

16

erty and the making of contracts are normally

matters of private and not of public concern. The

general rule is that both shall be free of govern

mental interference. But neither property rights

nor contract rights are absolute; for govern

ment cannot exist if the citizen may at will use

his property to the detriment of his fellows, or

exercise freedom of contract to work them harm.”

A striking illustration of choice between conflicting

property rights occurred in Miller v. Schoene, 276 U.S.

272; 72 L.Ed. 568; 48 S.Ct. 246 (1928), where the State

of Virginia had ordered the destruction of ornamental

cedar trees to prevent contamination of nearby apple or

chards with cedar rust. In upholding the State’s action,

the Court said that:

“When forced to such a choice the state does not

exceed its constitutional powers by deciding upon

the destruction of one class of property in order to

save another which, in the judgment of the legis

lature, is of greater value to the public.” 276 U.S.

272, 279; 72 L.Ed. 568, 571.

In the case at bar, not merely property rights, but signifi

cant human rights are at stake. Appellants submit that

the Court here can and should make the kind of accommo

dation between property rights and human rights as it

made in Marsh V. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501, 539; 90 L.Ed.

265, 270; 66 S.Ct, 276 (1946), where the Court concluded

that:

“When we balance the Constitutional rights of

owners of property against those of the people to

17

enjoy freedom of press and religion, as we must

here, we remain mindful of the fact that the lat

ter occupy a preferred position.”

Surely the right to racial equality, at this juncture of

America’s historical development, shares with the freedom

of press and religion an equally elevated position in the

hierarchy of preferred constitutional rights.

Such accommodations of conflicting constitutional

pressures have, of course, characterized the Court’s deter

minations in a variety of situations. Freedom of speech

and assembly is typically weighed against an asserted

clear and present danger. Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310

U.S. 296; 84 L.Ed. 1213; 60 S.Ct. 900 (1940). The com

mand of religious disestablishment has been leavened to

accommodate the needs of public safety. Everson V. Board

of Education, 330 U.S. 1; 91 L.Ed. 711; 67 S.Ct. 504

(1947). The many meanings of procedural due process de

fine and modify our criminal jurisprudence in a system of

ordered liberty. Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U.S. 319; 82

L.Ed. 288; 58 S.Ct. 149 (1937). How far a state may go

in regulating interstate commerce without unduly burden

ing it is a recurrent paradox. Cf. Southern Pacific Co. v.

Arizona, 325 U.S. 761; 89 L.Ed. 1915; 65 S.Ct. 1515

(1945). And the reasonableness of classifications and dis

criminations under the equal protection clause itself has

frequently required resolution by the Court. McGoivan v.

Maryland, 366 U.S. 420; 6 L.Ed.2d 393; 81 S.Ct. 1101

(1961).* 5

5But of course only the most extraordinary circumstances, such as

the exigencies of wartime security, can justify discrimination based on

race. Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81; 87 L.Ed. 1774; 63

S. Ct. 1375 (1943).

18

In the instant case the conflict between property-

rights and civil rights should and must be resolved against

the use of state laws such as § 509.141 which aid racial dis

crimination by restaurant owners. Moreover, such a res

olution need not imply the assertion of any absolutist prin

ciples which would necessarily embarrass judicial flexi

bility where it may be needed in the future. As the Court

said in Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S.

715, 725; 6 L.Ed.2d 45, 52; 81 S.Ct. 856 (1961) :

“ . . . respondent’s prophecy of nigh universal ap

plication of a constitutional precept so peculiarly

dependent for its invocation upon appropriate

facts fails to take into account ‘Differences in cir

cumstances [which] beget appropriate differences

in law,’ Whitney v State Tax Com. 309 US 530,

542, 84 L ed 909, 915, 60 S Ct 635.”

This same approach, in the area of religious disestablish

ment, is embodied in Mr. Justice Brennan’s opinion in

School District of Abington V. Schempp, supra:

“These considerations bring me to a final con

tention of the school officials in these cases: that

the invalidation of the exercises at bar permits

this Court no alternative but to declare unconsti

tutional every vestige, however slight, of coopera

tion or accommodation between religion and gov

ernment. I cannot accept that contention. While

it is not, of course, appropriate for this Court to

decide questions not presently before it, I venture

to suggest that religious exercises in the public

schools present a unique problem. For not every

involvement of religion in public life violates the

19

Establishment Clause. Our decision in these cases

does not clearly forecast anything about the con

stitutionality of other types of interdependence

between religious and other public institutions.”

31 Law Week, 4683, 4710.

Appellants offer, then, no startling novelty of the

law, either in substance or approach. The precedents are

bountiful, the approach is traditional. “There is here no

seismic innovation. The edifice of justice stands, its sym

metry to many, greater than before.” Cardozo, J., in Palko

V. Connecticut, 302 U.S. 319, 328; 82 L.Ed. 288, 294.

II.

Apart from the participation of the police and

the state courts herein, the discriminatory ac

tion of Shell’s City itself constituted state action,

since by virtue ©f the Florida restaurant licens

ing law, Florida Statutes Chapter 509, together

with the regulations promulgated thereunder,

the State has, within the meaning of the BUR

TON y. WILMINGTON PARKING AUTHOR

ITY, “so far insinuated itself into1 a position of

interdependence” with restaurants “that it must

be recognized as a joint participant in the chal

lenged activity.”

The Florida legislature has declared that the restau

rant business is intimately affected with the public in

terest and Chapter 509 describes in great detail the pub

lic duties and responsibilities of the restaurants. The

legislature has established the Florida Hotel and Restau

20

rant Commission,6 which has continuing regulatory super

vision over “public food establishments”, and the legisla

ture requires that the Commissioner shall execute the

laws governing their inspection and regulation “for the

purpose of safeguarding the public health, safety, and wel

fare.”7 8 Having thus stated the public interest of the State

of Florida in the restaurant business, Chapter 509 then

proceeds to elaborate upon the details of its regulation.

Thus, it requires approval by the Commissioner of the

architect’s plans for the erection or remodeling of any

restaurant.s It regulates fire escapes, stairways and

exits.9 It regulates plumbing, lighting, heating, cooling

and ventilation facilities.10 It requires every restaurant to

obtain a license as a “public food service establishment”,11

makes it a misdemeanor for such an establishment to

operate without a license, and sets forth the procedure

for revocation of such licenses.12 It forbids a municipality

or county from issuing any occupational license unless the

Commissioner has first licensed the restaurant.13 And it

establishes an advisory council of private restaurants and

hotels for the purpose of and “to suggest means of better

protecting the health, welfare and safety of persons util

izing the services offered by the industries represented

on the council.”14

The statute pursuant to which Appellants were ar

rested, § 509.141, is an integral part of the above Chap

6Florida Statutes § 509.012 (App. 6).

7Florida Statutes § 509.032(1) (App. 7).

8Florida Statutes § 509.211(4) (App. 11).

’Florida Statutes § 509.211(1) (App. 10).

10Florida Statutes § 509.221 (App. 15).

u Florida Statutes § 509.241 (App. 18).

12Florida Statutes § 509.261 (App. 21).

13Florida Statutes § 509.271 (App. 24).

1+Florida Statutes § 509.291 (App. 25).

21

ter and an integral part of this elaborate legislative

schema and program encompassing “public food estab

lishments.”

In addition, extensive regulations have been pro

mulgated by the Commissioner, prescribing in minute de

tail the health and safety measures by which every res

taurant must abide. Florida Administrative Code, Chap

ters 175-1, 175-2 and 175-4. And it is especially important

to note that the regulations are not concerned solely with

health and safety measures, but in order to promote and

safeguard the public welfare, also, inter alia, (1) provide

that licenses may be issued only “to establishments op

erated, managed or controlled by persons of good moral

character” ;15 (2) prohibit publication or advertisement of

false or misleading statements relating to food or bev

erages offered to the public on the premises;16 and (3)

provide that “achievement rating cards be conspicuously

displayed”.17

Moreover, Chapter 509 is obviously not designed

merely to raise revenue or merely compel compliance with

zoning ordinances, as in the case of the typical occupa

tional licensing statute. And even though the grant of an

occupational license as such may be a condition precedent

15Florida Administrative Code, § 175 - 1.02. The 1963 session

of the Florida Legislature further implemented the law by authorizing

the Commission to revoke or suspend a license when “Any person

interested in the operation of any such establishment, whether owner,

agent, lessee, or manager, has been convicted within the past five years

in this state or any other state or the United States of soliciting for

prostitution, pandering, letting premises for prostitution, keeping a

disorderly place, illegally dealing in narcotics, or any other crime in

volving moral turpitude.” Chapter 63-63, Florida Statutes, § 509.261

(4) (a).

16Florida Administrative Code § 175-4.02.

17Florida Administrative Code § 175-1.03.

22

to engaging in the restaurant business, nevertheless, un

like the usual licensing requirements for merchants and

tradesmen, Chapter 509 provides for the exercise of con

tinuing administrative supervisory oversight and control,

comparable to the supervision of businesses normally de

scribed as public utilities.

In addition, Shell City, Inc., qua corporation, exists

only by virtue of state law, and is subject to the general

Florida laws governing the creation, regulation, and dis

solution of corporate entities. Florida Statutes, Chapter

608.

A restaurant, therefore, so linked to the state, and

so involved in matters of obvious public concern, is a

quasi-public instrumentality and cannot hide behind the

gossamer defense of “private” action.

“A license to establish a restaurant is a license

to establish a public facility and necessarily im

ports, in law, equality of use for all members of

the public . . . . Those who license enterprises for

public use should not have under our Constitution

the privilege to license it for the use of only one

race. For there is the overriding constitutional

requirement that all state power be exercised so

as not to deny the equal protection of any group.”

Douglas, J., concurring in Garner v. Louisiana,

368 U.S. 157, 184, 185; 7 L.Ed.2d 207, 226.

And as Harlan, J., observed, dissenting in The Civil Rights

Cases, with regard to state-licensed enterprises:

“The authority to establish and maintain them

23

comes from the public. The colored race is a part

of that public. The local government granting

the license represents them as well as all other

races within its jurisdiction. A license from the

public, to establish a place of public amusement,

imports, in law, equality of right, at such places,

among all the members of that public. This must

be so, unless it be—which I deny—-that the com

mon municipal government of all the people may,

in the exertion of its powers, conferred for the

benefit of all, discriminate or authorize discrimi

nation against a particular race, solely because

of its former condition of servitude.” 109 U.S.

3, 41; 27 L.Ed. 835, 849.

In Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, supra,

the Delaware statute in question was not unlike Florida

Statutes § 509.141, for it provided that:

“No keeper of an inn, tavern, hotel, or restaurant,

or other place of public entertainment or refresh

ment of travelers, guests, or customers shall be

obliged, by law, to furnish entertainment or re

freshment to persons whose reception or enter

tainment by him would be offensive to the major

part of his customers, and would injure his busi

ness.” 365 U.S. 715, 717; 6 L.Ed.2d 46, 47.

Notwithstanding this statutory provision, the Court con

cluded in Burton that the restaurant, because of its status

as the city’s lessee and because of its many other intimate

involvements with the city, was not, even though pri

vately owned, insulated from the scope of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

24

Burton was, of course, only one of many instances in

which the Court has held the action of an ostensibly pri

vate party to be, in constitutional contemplation, the act

of the government. Thus in Public Utilities Commission

V. Poliak, 343 U.S. 451; 96 L.Ed. 1068; 72 S.Ct. 813

(1952), the Court held that action of the Capital Transit

Company constituted governmental action by virtue of its

operating under the regulatory supervision of the Public

Utilities Commission of the District of Columbia. To like

effect was Baldwin V. Morgan, 287 F.2d 750 (5th Cir.,

1961), where the Court of Appeals held that the Birming

ham Terminal Company, albeit a private corporation, could

not effect racial segregation in its waiting rooms, since the

“terminal was admittedly a public utility holding itself

out to serve all of the traveling public desiring to use the

railroads operating through this station in Birmingham.”

287 F.2d 750, 755. The Court added that:

“When in the execution of that public function

it is the instrument by which state policy is to be,

and is, effectuated, activity which might other

wise be deemed private may become state action

within the Fourteenth Amendment.” 287 F.2d

750, 755.

Appellants submit that where racial discrimination is prac

ticed, there should be no difference in constitutional con

sequences between such traditional “public utilities” as a

transit company or a railroad terminal company, and a

“public food service establishment” licensed and regulated

under state law, for the extent of state involvement is no

less significant in the latter case. ,

Moreover, the constitutional consequences of racial

25

discrimination by the restaurant should be no different

than those determined by the Court in the case of the com

pany town in Marsh v. Alabama, supra, where the Court

stated that:

“In our view the circumstance that the property

rights to the premises where the deprivation of

liberty, here involved, took place, were held by

others than the public, is not sufficient to justify

the State’s permitting a corporation to govern a

community of citizens so as to restrict their fun

damental liberties and the enforcement of such

restraint by the application of a state statute.”

326 U.S. 501, 509; 90 L.Ed. 265, 270.

Appellants further contend that the discrimination

by Shell’s City was no more “an individual invasion of in

dividual rights” than was the action of the Democratic

Party in Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649; 88 L.Ed. 987;

64 S.Ct. 757 (1944), where the Court outlawed the Texas

white primary and ruled that even though the Democratic

party in Texas had been characterized as a “voluntary as

sociation” under Texas law, nevertheless, since the me

chanics of the primary were prescribed in detail by State

law and since the party performed duties Imposed by State

statutes, the duties it performed did not become matters

of private law merely because performed by a “private

political party”. The Court stated that:

“If the state requires a certain electoral proce

dure, prescribes a general election ballot made up

of party nominees so chosen and limits the choice

of the electorate in general elections for state of

fices, practically speaking, to those whose names

26

appear on such a ballot, it endorses, adopts and

enforces the discrimination against Negroes,

practiced by a party entrusted by Texas law with

the determination of the qualifications of partici

pants in the primary. This is state action within

the meaning of the Fifteenth Amendment.” 321

U.S. 649, 664; 88 L.Ed. 987, 997.

To like effect were the obligations imposed upon the “pri

vate” collective bargaining agent in Steele v. Louisville

& Nashville Railroad Company, 323 U.S. 192; 89 L.Ed.

173; 65 S.Ct. 226 (1944).

Appellants submit that the interdependence of the

restaurant and the State imposes a positive Constitutional

duty upon the restaurant to respect the rights of all cus

tomers to be treated and served without regard to their

race. Shell’s City has nineteen departments in its em

porium. It invites the entire public, white and colored

alike, to buy its wares in eighteen of the departments,

without discrimination. Only in the nineteenth, the res

taurant, does it draw the line. Whatever may be its Con

stitutional obligations vel non to sell or not sell notions,

hardware, clothing or the like to persons of color in the

other eighteen departments, it clearly has the Constitu

tional obligation to refrain from racial discrimination in

its restaurant.

If it be concluded that the majority in The Civil

Rights Cases may have rejected Justice Harlan’s view with

respect to the effect of state licensing laws, then and to

that extent Appellants pray that the Court no longer fol

low the majority’s ruling. Indeed, the rulings of the Court

in the subsequent cases of Burton, Poliak, and Smith V.

27

Allwright, above, depart from any such implications con

tained in Justice Bradley’s opinion, and it would appear,

therefore, that the Court need no longer be bound thereby.

III.

The racial discrimination practiced by Shell’s

City is engendered by racial customs prevalent

in Miami and throughout the State of Florida,

and the pressures, of state and local customs

which were brought to bear upon the Appel

lants, necessarily constituted a denial by state

action of Appellants’ rights to the equal protec

tion of the laws within the meaning of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

In The Civil Rights Cases, supra, the Court stated

that:

“civil rights such as are guaranteed by the Con

stitution against state aggression, cannot be im

paired by the wrongful acts of individuals, un

supported by state authority in the shape of law,

customs, or judicial or executive proceedings.”

109 U.S. 1, 17; 27 L.Ed. 835, 841 (Emphasis sup

plied.)

The existence and force of such customs was made strik

ingly clear by one of the State’s own witnesses in the case

at bar. Mr. Warren C. Williams, vice-president of Shell’s

City, testified that the policy of Shell’s City not to serve

colored people is “based upon the customs, the habits and

what we believe to be the desire of the majority of the

white people of this county” ; that “it goes back to what

28

is the custom, that is, the tradition of what is basically

observed in Dade County would be the bottom of it” ; that

“it is the customs and traditions and practice in this

county—not only in this county but in this part of the

state and elsewhere, not to serve whites and colored peo

ple seated in the same restaurant” ; and that “if we went

into a thing of trying to break that barrier, we might have

racial trouble, which we don’t want.” (R. 29, 30)

Not only do these customs exist, but their underlying

prejudices have been perpetuated and reinforced by a va

riety of enactments of the State of Florida which restrict

the liberties of colored people and humiliate them as human

beings. The Florida Constitution provides that white and

colored children shall not be taught in the same school.18

Separation of the races is required on railroads and in

railroad waiting rooms.19 Segregation of the races is re

quired by county jails.20 21 And marital and sexual congress

between the races is prohibited and restricted with such

elaborate reiteration as to suggest involvement in a para

noid ritual.31

But even apart from these enactments, “long-accepted

customs and the habits of a people may generate ‘law’ as

surely as a formal legislative declaration, and indeed, some

times even in the face of it.” Frankfurter, J., concurring

in Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461, 475; 97 L.Ed. 1152, 1163;

73 S.Ct. 809 (1953).

18Florida Constitution, Article X II, § 12 (App. 1).

19Florida Statutes §§ 352.03-352.18 (App. 1-6).

20Florida Statutes §§ 950.05-950.08 (App. 30-31).

21Florida Constitution, Article XVI, § 24 (App. 1 ); Florida

Statutes §§ 798.04; 798.05; 741.11-741.16 (App. 26-28).

29

And as Mr. Justice Douglas observed, concurring in

Garner v. Louisiana, supra:

“Though there may have been no State law or mu

nicipal ordinance that in terms required segrega

tion of the races in restaurants, it is plain that

the proprietors in the instant cases were segre

gating blacks from whites pursuant to Louisi

ana’s custom. Segregation is basic to the struc

ture of Louisiana as a community; the custom

that maintains it is at least as powerful as any

law.” 368 U.S. 157, 181; 7 L.Ed.2d 207, 224.

It is Appellants’ position that the word “state” as

used in the Fourteenth Amendment need not be confined

to the political representatives of the people, i.e., the exec

utive, the legislature and the judiciary. Obviously, the peo

ple themselves can act politically and directly by constitu

tional enactment, and by such enactment, violate guaran

tees of the Federal Constitution. Thus, in Neal v. Dela

ware, 103 U.S. 370; 26 L.Ed. 567 (1881) the Court con

cluded that the Fifteenth Amendment nullified a provi

sion of the constitution of Delaware which had purported

to restrict the sufferage to white persons. Appellants sub

mit that if action by the people themselves, as in the case

of a constitutional enactment, amounts to state action, then

action by the people themselves, even though not mani

fested in the legal formalism of a constitutional enactment,

may likewise constitute state action where it is in the form

of the mass pressure of customs and prejudices which

coerce the individual private party into compliance.22 In

22And the “mental urges” behind the restaurant owner’s decision

to discriminate would be irrelevant. Peterson v. Louisiana, supra, 31

Law Week 4475, 4476.

30

deed, if the agents and delegates of the people—the legis

lators, the administrators and the judges—are restrained

from effectuating racial discrimination, then it should fol

low a fortiori, and it would be a strange anomaly if it were

otherwise, that the principal, namely the people them

selves, should be subject to the same Federal Constitutional

prohibitions. Section 2 of the Declaration of Rights of the

Florida Constitution explicitly provides that “All political

power is inherent in the people.” Translated into the terms

of the instant case, the people of the State of Florida, act

ing as the “state”, compelled the restaurant owner to dis

criminate and thus the people of the state, constituting the

“state”, denied Appellants the equal protection of the laws.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, Appellants pray the Court

to reverse the judgments below and order that judgments

of acquittal be entered as to all of the Appellants.

Respectfully submitted,

ALFRED I. HOPKINS,

TOBIAS SIMON and

HOWARD W. DIXON

Counsel for Appellants

223 S. E. First Street

Miami, Florida

By-

Alfred I. Hopkins

31

CERTIFICATE OF MAILING

I, ALFRED I. HOPKINS, counsel for Appellants and

a member of the Bar of the Supreme Court of the United

States, hereby certify that on August__ , 1963, I served

copies of the foregoing Brief for the Appellants on the

Appellee, STATE OF FLORIDA, by mailing a copy there

of in a duly addressed envelope with postage prepaid to

the office of RICHARD E. GERSTEIN, State Attorney,

Dade County Courthouse, Miami, Florida, and by further

mailing a copy thereof to the Honorable RICHARD

ERVIN, Attorney General of the State of Honda, Capitol

Building, Tallahassee, Florida.

Alfred I. Hopkins

A P P E N D I X

TO BRIEF FOR THE APPELLANTS

Florida Constitution, Article XII, § 12 provides as

follows:

“White and colored children shall not be taught

in the same school, but impartial provision shall

be made for both.”

Florida Constitution, Article XVI, § 24, provides as

follows:

“All marriages between a white person and a

negro, or between a white person and a person

of negro descent to the fourth generation, inclu

sive, are hereby forever prohibited.”

Set forth below are the sections of the Florida Stat

utes cited in the foregoing brief:

352.03 First-class tickets and accommodations for

negro persons.—All railroad companies doing business in

this state shall sell to all respectable negro persons first-

class tickets, on application, at the same rates that white

persons are charged, and shall furnish and set apart for

the use of such negro persons who purchase such first-

class tickets a car or cars in each passenger train, as may

be necessary, equally as good and provided with the same

facility for comfort as shall or may be provided for whites

using and traveling as passengers on first-class tickets.

No conductor or person in charge of any passenger

train on any railroad shall suffer or permit any white

person to ride, sit or travel, or to do any act or thing to

insult or annoy any negro person who shall be sitting,

App. 2

riding and traveling, in said car so set apart for the use

of negro persons, nor shall he or they, while in charge of

such train, suffer or permit any negro person, nor shall

such person attempt to, ride, sit or travel in the car or

cars set apart for the use of the white persons traveling

as first-class passengers; but female colored nurses, hav

ing the care of children or sick persons, may ride and

travel in such car.

352.04 Separate accommodations for white and

colored passengers.—-All railroad companies and other

common carriers doing business in this state shall provide

equal separate accommodations for white and colored

passengers on railroads, and all white and colored passen

gers occupying passenger cars which are operated in this

state by any railroad company or other common carrier

are hereby required to occupy the respective cars, or

divisions of cars, provided for them, so that the white

passengers shall occupy only the cars or divisions of cars,

provided for white passengers, and the colored passengers

only the cars, or division of cars, provided for colored

passengers; provided, that no railroad shall use divided

cars for the separation of the races without the permis

sion of the railroad commission, nor any car divided for

that purpose in which the divisions are not permanent.

352.05 Passenger occupying part of car set apart for

opposite race; penalty.—Any white person unlawfully and

willfully occupying, as a passenger, any car or part of car

not so set apart and provided for white passengers, and

any colored passenger unlawfully and willfully occupying,

as a passenger, any car or part of car not so set apart and

provided for colored passengers, shall, upon conviction, be

punished by a fine not exceeding five hundred dollars, or

App. 3

imprisonment not exceeding six months. Nothing in this

section shall apply to persons lawfully in charge of or

under the charge of persons of the other race.

352.08 Penalty for violations §352.04.—If any rail

road company or other common carrier shall violate any

of the provisions of §352.04, or any rule, order or regula

tion prescribed by the railroad and public utilities com

missioners under the authority of §350.20, such company

or common carrier shall thereby incur for each such of

fense a penalty of not more than five hundred dollars, to

be fixed, imposed and collected by said railroad and public

utilities commissioners in the manner provided in §350.28.

352.07 Separate accommodations for w h i t e and

negro passengers on electric cars.—All persons operating

urban and suburban (or either) electric cars as common

carriers of passengers in this state, shall furnish equal

but separate accommodations for white and negro passen

gers on all cars so operated.

352.08 Method of division in electric cars.—The

separate accommodations for white and negro passengers

directed in §352.07 shall be by separate cars, fixed divi

sions, movable screens, or other method of division in the

cars.

352.09 Divisions to be marked “For White” or “For

Colored.”—The car or division provided for white passen

gers shall be marked in plain letters in a conspicuous

place, “For White,” and the car or division provided for

negro passengers shall be marked in plain letters in a

conspicuous place, “For Colored.”

App. 4

352.10 Not to apply to nurses.—Nothing in §§352.07,

352.08, 352.09, 352.12, 352.13, 352.14, or 352.15 shall be so

construed as to apply to nurses of one race attending chil

dren or invalids of the other race.

352.11 Operating extra cars for exclusive use of

either race.—Sections 352.07-352.15 shall not be so con

strued as to prevent the running of special or extra cars,

in addition to the regular schedule cars, for the exclusive

accommodation of either white or negro passengers.

352.12 Separation of races; penalty.—Any person

operating urban and suburban (or either) electric cars as

common carriers of passengers in this state, failing, re

fusing or neglecting to make provisions for the separa

tion of the white and negro passengers on such cars as

required by law, shall, for each offense, be deemed guilty

of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction thereof shall be

fined not less than fifty dollars nor more than five hun

dred dollars. This penalty may be enforced against the

president, receiver, general manager, superintendent or

other person operating such cars.

352.13 Duty of conductors ; penalty.—The conductor

or other person in charge of any such car shall see that

each passenger is in the car or division furnished for the

race to which such passenger belongs, and any conductor

or other person in charge of such car who shall permit

any passenger of one race to occupy a car or division pro

vided for passengers of the other race, shall be deemed

guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction thereof

shall be punished by a fine of not exceeding twenty-five

dollars, or by imprisonment in the county jail for not ex

ceeding sixty days.

App. 5

352.14 Violation by passengers; conductor may ar

rest and eject; penalty.—Any passenger belonging to one

race who willfully occupies or attempts to occupy any

such car, or division thereof, provided for passengers of

the other race, or who occupying such car or division

thereof, refuses to leave the same when requested so to

do by the conductor or other person in charge of such car,

shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon con

viction thereof shall be punished by a fine of not exceed

ing fifty dollars, or by imprisonment in the county jail

for not exceeding three months. The conductor or other

person in charge of such car is vested with full power and

authority to arrest such passenger and to eject him or her

from the car.

352.15. Each day of refusal separate offense.—Each

day of refusal, failure or neglect to provide for the sepa

ration of the white and negro passengers as directed in

this chapter shall constitute a separate and distinct of

fense.

352.16. Separate waiting rooms and ticket windows

for white and negro passengers.—All railroad companies

and terminal companies in this state shall provide sep

arate waiting rooms and ticket windows of equal accom

modation for white and colored passengers at all depots

along lines of railway owned, controlled or operated by

them, and at terminal passenger stations controlled and

operated by them.

357.17 Penalty for refusal to comply with law or

regulations.-—If any railroad company or terminal com

pany in this state shall refuse to comply with any provi

sion of §352.16, or to comply with any rule, order or regu

App. 6

lation provided or prescribed by the railroad and public

utilities commissioners under the authority of §350.21,

such company shall thereby incur a penalty for each such

offense of not more than five thousand dollars, to be

fixed, imposed and collected by said railroad and public

utilities commissioners in the manner provided by law.

352.18 Penalty for not providing separate cars for

white and negro persons—If any railroad company or any

conductor or other employee thereof, or any person what

ever, shall violate the provisions relating to the accommo

dation of white or negro passengers, he or they shall be

punished by a fine not exceeding five hundred dollars,

unless otherwise provided for.

If any railroad company shall fail to comply with said

provisions of law the punishment herein prescribed may

be inflicted upon the president, receiver, general manager

or superintendent thereof, or upon each and every one of

them.

509.012 Hotel and restaurant commission.—There is

created a hotel and restaurant commission, for which the

usual facilities for transacting its business shall be fur

nished the same as for other executive departments of

the state government.

509.022 Appointment of hotel and restaurant com

missioner; term of office; bond and salary.—The governor

shall appoint a hotel and restaurant commissioner whose

term of office shall begin and run concurrently with the

regular terms of office of the successive governors of

this state and who shall give bond in the sum of ten thou

sand dollars for the faithful performance of his duties, to

App. 7

be approved by the governor. He shall receive a salary

as provided in the general biennial appropriations act, or

as hereafter provided by law, and shall be reimbursed for

travel in connection with the duties of the office in ac

cordance with the provisions of §112.061.

509.032 Duties.—

(1) GENERAL.—The hotel and restaurant commis

sioner shall carry out and execute all of the provisions of

this chapter and all other laws now in force or which may

hereafter be enacted relating to the inspection or regula

tion of public lodging and public food service establish

ments for the purpose of safeguarding the public health,

safety and welfare. The commissioner shall be responsible

for ascertaining that no establishment licensed by this

commission shall engage in any misleading advertising or

unethical practices as defined by this chapter and all

other laws now in force or which may hereafter be en

acted. He shall keep accurate account of all expenses

arising out of the performance of his duties and shall file

monthly itemized statements of such expenses with the

comptroller, together with an account of all fees collected

under the provisions of this chapter.

(2) SEMI-ANNUAL INSPECTION.—The hotel and

restaurant commissioner shall inspect, or cause to be in

spected, at least twice annually, every public lodging and

food service establishment in this state, and for that pur

pose he shall have the right of entry and access to such

establishments at any reasonable time.

(3) AUTHORIZED TO MAKE RULES.—The hotel

and restaurant commissioner shall make such rules and

App. 8

regulations as are necessary to carry out the provisions of

this chapter in accordance with its true intent.

509.141 Ejection of undesirable guests; notice, pro

cedure, etc.—

(1) The manager, assistant manager, desk clerk or

other person in charge or in authority in any hotel, apart

ment house, tourist camp, motor court, restaurant, room

ing house or trailer court shall have the right to remove,

cause to be removed, or eject from such hotel or apart

ment house, tourist camp, motor court, restaurant, room

ing house or trailer court in the manner hereinafter pro

vided, any guest of said hotel, apartment house, tourist

camp, motor court, restaurant, rooming house or trailer

court, who, while in said hotel, apartment house, tourist

camp, motor court, restaurant, rooming house or trailer

court premises is intoxicated, immoral, profane, lewd,

brawling, or who shall indulge in any language or conduct

either such as to disturb the peace and comfort of other

guests of such hotel, apartment house, tourist camp,

motor court, restaurant, rooming house or trailer court

or such as to injure the reputation or dignity or standing

of such hotel, apartment house, tourist camp, motor court,

restaurant, rooming house or trailer court, or who, in the

opinion of the management, is a person whom it would be

detrimental to such hotel, apartment house, tourist camp,

motor court, restaurant, rooming house, or trailer court

for it any longer to entertain.

(2) The manager, assistant manager, desk clerk or

other person in charge or in authority in such hotel,

apartment house, tourist camp, motor court, restaurant,

rooming house or trailer court shall first orally notify

App. 9

such guest that the hotel, apartment house, tourist camp,

motor court, restaurant, rooming house or trailer court no

longer desires to entertain him or her and request that

such guest immediately depart from the hotel, apartment

house, tourist camp, motor court, restaurant, rooming

house or trailer court. If such guest has paid in advance

the hotel, apartment house, tourist camp, motor court,

restaurant, rooming house or trailer court shall, at the

time oral or written request to depart is made, tender to

said guest the unused or unconsumed portion of such ad

vance payment. Said hotel, apartment house, tourist camp,

motor court, restaurant, rooming house or trailer court

may, if its management so desires, deliver to such guest

written notice in form as follows:

“You are hereby notified that this establishment no

longer desires to entertain you as its guest and you are

requested to leave at once and to remain after receipt of

this notice is a misdemeanor under the laws of this state.”

(3) And any guest who shall remain or attempt to

remain in such hotel, apartment house, tourist camp,

motor court, restaurant, rooming house or trailer court

after being requested, as aforesaid, to depart therefrom,

shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be deemed to

be illegally upon such hotel, apartment house, tourist

camp, motor court, restaurant, rooming house or trailer

court premises.

(4) In case any such guest, or former guest, of such

hotel, apartment house, tourist camp, motor court, res

taurant, rooming house or trailer court, or any other per

son, shall be illegally upon any hotel, apartment house,

tourist camp, motor court, restaurant, rooming house or

App. 10

trailer court premises, the management, or any employee

of such hotel, apartment house, tourist camp, motor court,

restaurant, rooming house or trailer court, may call to its

assistance any policeman, constable, deputy sheriff,

sheriff or other law enforcement officer of this state, and

it shall be the duty of each member of the aforesaid

classes of officers, upon request of such hotel, apartment

house, tourist camp, motor court, restaurant, rooming

house or trailer court management, or hotel, apartment

house, tourist camp, motor court, restaurant, rooming

house or trailer court employee, forthwith and forceably,

if necessary, to immediately eject from such hotel, apart

ment house, tourist camp, motor court, restaurant, room

ing house or trailer court, any such guest, or former

guest, or other person, illegally upon such hotel, apart

ment house, tourist camp, motor court, restaurant, room

ing house or trailer court premises, as aforesaid.

509.211 Safety regulations.—

(1) Every public lodging or public food service

establishment shall have signs displayed in all hallways

indicating all fire escapes, stairways and exits.

(2) Whenever it shall be proposed to erect a build

ing three stories or more in height, intended for use as a

public lodging establishment in this state, the owner, con

tractor or builder of such establishment shall construct

said establishment so that one main hall, on each floor

above the ground floor, shall extend to the outside wall

at each end; or such main hall may turn at either or both

ends, provided the distance from the main hall to the out

side of the building, at any point, is no more than the

depth of the room facing the outside of the building, and

App. 11

provided further that the hall so turned shall extend to