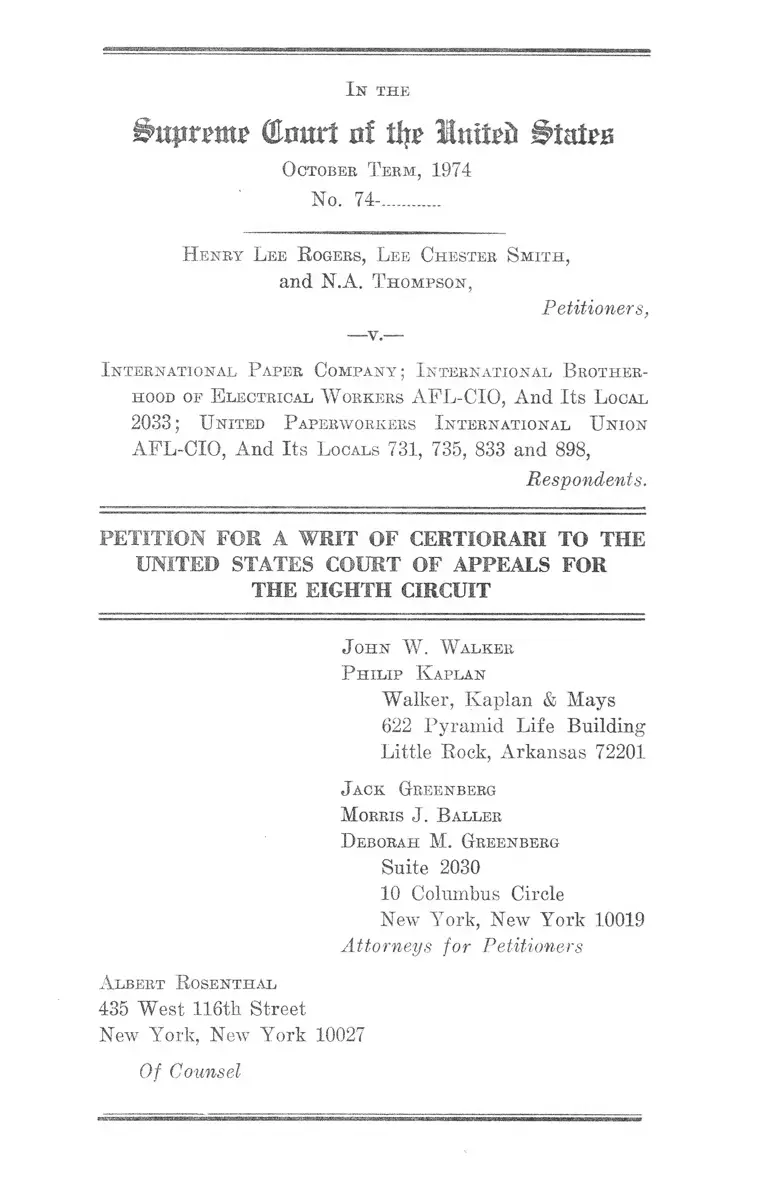

Rogers v International Paper Company Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 7, 1975

92 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rogers v International Paper Company Writ of Certiorari, 1975. 5bd85ec9-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b53c910e-ca55-46c5-a8ed-f12c1938656c/rogers-v-international-paper-company-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

QJmrrt at tip? United States

October Term, 1974

No. 74-..........

I n the

Henry Lee R ogers, Lee Chester. Smith,

and N.A. T hompson,

Petitioners.

— v .—

I nternational, P aper Company; International Brother

hood of E lectrical W orkers AFL-CIO, And Its L ocal

2033; United P aperwoekebs I nternational U nion

AFL-CIO, And Its L ocals 731, 735, 833 and 898,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

J ohn W . W alker

P hilip K aplan

Walker, Kaplan & Mays

822 Pyramid Life Building

Little Bock, Arkansas 72201

Jack Greenberg

Morris J. B aller

Deborah M. Greenberg

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioners

A lbert R osenthal

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinions Below .................-...........-............ ................... 1

Jurisdiction ............ ..... ..... .......................... ................... 2

Questions Presented............................. ..........................~ 2

Statutory Provisions Involved .......... -............ ..... ........ 3

Statement of the Case ...... ................................. ............. 4

Reasons for Granting the Writ—

I—The Case Presents an Important Question

of Federal Law Which Should Be Settled by

This Court .................... ................. ........ ......... 10

II—The Decision Below Is in Conflict With the

Decisions of Other Courts of Appeals on the

Same Matter ....... .............. ............. ......... ..... 12

III—Efficient Judicial Administration Would Be

Served if This Court Will Grant Certiorari,

Vacate the Judgment Below, and Remand

for Further Consideration in the Light of

This Court’s Decision in Albemarle Paver

Company v. Moody and Halifax Local No.

425, United Papermakers and Paperworkers,

AFL-CIO v. Moody ....................................... 14

Conclusion............................................... 15

A ppendix—

Opinion of District Court...................... la

Opinion of Court of Appeals ....... ........................ 35a

Order Modifying Opinion and Denying Respon

dent International Paper Company’s Petition for

Rehearing ................................... 68a

Order Denying Petitioner’s Petition for Rehearing 71a

11

Table of A uthorities

Cases: page

Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody, No. 74-389, ar

gued April 14, 1975 ........ ............ ........ .......... ..... 2, 7,14,15

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711 (7th

Cir. 1969), 489 F.2d 896 (7th Cir. 1973) ................. 13

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ......... 14

Halifax Local No. 425, United Papermakers and

Paperworkers, AFL-CIO v. Moody, No. 74-428, ar

gued April 14, 1975 ........ ................. ..... ....... ..... .... 2,14,15

Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., 484 F.2d 870 (6th

Cir. 1973) .......................................................................... 13

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d

1364 (5th Cir. 1974) ....................... .............................12,14

Local 189, United Papermakers & Paperworkers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert,

denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970) ........................... .............. 5

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ........... 11

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 474 F.2d (4th Cir.

1973), cert, granted, ------ U.S. ------ , 95 S.Ct. 654

(Dec. 16, 1974) ............... 12

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211

(5th Cir. 1974) ........................................... 12

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 319 F. Supp. 835 (M.D.

N.C. 1970) affirmed, 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971),

cert, dismissed, 404 U.S. 1006 (1971) .............. 5,9,13,14

Ill

PAGE

Rosen v. Public Service Gas & Electric Co., 477 F.2d

90 (3rd Cir. 1973) ..... ......... ........ .................................. 13

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652

(2d Cir. 1971) .................................-............................. 5,9

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906 (5th

Cir. 1973) ............. .................. ......................................... 12

United States v. N.L. Industries, 479 F.2d 354 (8th

Cir. 1973) ..................................................................... 5, 7,13

Statutes:

P.L. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103 (Equal Employment Opportu

nity Act of 1972) ..................... ......................................- 11

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) ............ ............................. ................. 2

28 U.S.C. §§ 1343(4), 2201 and 2202 .............................. 5

29 U.S.C. § 151 et seq...................................................... 5

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq. (Title VII, Civil Rights Act

of 1964) .......................... .............................................passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a) (Title VII, § 703(a)) ................ 3

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(c) (Title VII, § 703(c)) ................ 3

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g) (Title VII, § 706 (g )) ............... 4

42 U.S.C. § 1981 .................................................................. 4

Other Authorities:

118 Cong. Rec. 4942 (1972)

118 Cong. Rec. 7168 (1972)

12

12

I n th e

Supreme (tart of % TtHniUb

October Term, 1974

No. 74-...........

H enry Lee R ogers, Lee Chester Smith ,

and N.A. T hompson,

Petitioners,

—v.—

I nternational P aper Company ; I nternational Brother

hood oe E lectrical W orkers AFL-CIO, And Its L ocal

2033; United Paperworkers I nternational Union

AFL-CIO, And Its Locals 731, 735, 833 and 898,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

The petitioners respectfully pray that a writ of certiorari

issue to review the judgment and opinion of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit entered in

this proceeding on January 7, 1975 and modified February

14, 1975.

Opinions Below

The decision of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Eighth Circuit and the order denying the petition for

rehearing of the respondent International Paper Company,

reported at 510 F.2d 1340, are reprinted infra at 35a and

2

68a, respectively.1 The order denying the petition for re

hearing of the petitioners is printed infra at 71a. The

memorandum opinion of the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Arkansas has not been reported,

but is printed infra at la.

Jurisdiction

The judgment and opinion of the Court of Appeals was

entered on January 7, 1975. Separate petitions for rehear

ing timely filed by respondent International Paper Com

pany and by petitioners were denied, respectively, on Feb

ruary 14 and 18, 1975. Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

Questions Presented

1. Whether the future elimination of racial discrimi

nation in opportunities for promotion and transfer, pur

suant to court order under Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, obviates the need for back pay to redress

economic loss suffered in the past by victims of such dis

crimination.

2. Whether the decision of the court below, in denying

back pay to victims of racial discrimination in employment,

is consistent with the disposition that will be made by this

Court of the questions concerning the standards governing

the award of back pay under Title Y U of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 raised in Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody,

No. 74-389, and Halifax Local No, 425, United Paper makers

and Paper workers, AFL-CIO v. Moody, No. 74-428, argued

April 14, 1975 and presently pending before this Court.

1 This form of citation is to pages of the Appendix.

3

Statutory Provisions Involved

The pertinent sections of Title V II of the Civil Eights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq., as amended, provide:

Section 703(a), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a) :

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer—

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any in

dividual, or otherwise to discriminate against any in

dividual with respect to his compensation, terms, con

ditions, or privileges of employment, because of such

individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin; or

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or

applicants for employment in any way which would

deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employ

ment opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his

status as an employee, because of such individual’s

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Section 703(y), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(c):

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for a

labor organization—

(1) to exclude or to expel from its membership, or

otherwise to discriminate against, any individual be

cause of his race, color, religion, -sex, or national

origin;

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify its membership

or applicants for membership, or to classify or fail

or refuse to refer for employment any individual, in

any way which would deprive or tend to deprive any

individual of employment opportunities, or would limit

4

such employment opportunities or otherwise adversely

affect his status as an employee or as an applicant for

employment, because of such individual’s race, color,

religion, sex, or national origin.

Section 706(g), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g):

I f the court finds that the respondent has inten

tionally engaged in or is intentionally engaging in an

unlawful employment practice charged in the com

plaint, the court may enjoin the respondent from en

gaging in such unlawful employment practice, and

order such affirmative action as may be appropriate,

which may include, but is not limited to, reinstatement

or hiring of employees, with or without back pay (pay

able by the employer, employment agency, or labor or

ganization, as the case may be, responsible for the

unlawful employment practice), or any other equitable

relief as the court deems appropriate. . . . No order of

the court shall require the admission or reinstatement

of an individual as a member of a union, or the hiring,

reinstatement, or promotion of an individual as an em

ployee, or the payment to him of any back pay, if such

individual was refused admission, suspended, or ex

pelled, or was refused employment or advancement or

was suspended or discharged for any reason other than

discrimination on account of race, color, religion, sex,

or national origin or in violation of section 704(a).

Statement o f the Case

The petitioners, Henry Lee Rogers, Lee Chester Smith

and N.A. Thompson, black employees of respondent Inter

national Paper Company, brought this suit as a class

action on May 17, 1971, under Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq.; 42 U.S.C. §1981;

5

and 29 U.S.C. § 151 et seq. (prescribing a duty of fair

representation). Federal jurisdiction was predicated upon

28 TT.S.C. §§1343(4), 2201 and 2202. The complaint

alleged racial discrimination in employment by respondent

International Paper Company (hereinafter “the Com

pany” ) with respect to hiring, compensation, promotion

and other terms and conditions of employment at its Pine

Bluff, Arkansas mill, and the maintenance of discrimina

tory employment practices by the respondent unions.2

Following a trial in February and March 1972, the District

Court found that all of the respondents “ openly dis

criminated on the basis of race in the hiring and assign

ment of employees” from the time the Pine Bluff Mill

opened in 1958,3 and that this discrimination and the effects

thereof, as perpetuated by a variety of practices including

a “ job seniority” system,4 continued unabated until August

2 International Brotherhood of Pnlp, Sulphite and Paper Mill

Workers, APL-CIO; Locals 898 and 946 of the International

Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite and Paper Mill Workers; United

Papermakers and Paperworkers, AFL-CIO; Locals 731, 735 and

833, United Papermakers and Paperworkers, Pine Bluff, Arkansas;

International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, AFL-CIO; and

Local 2033, International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers.

Local 946 of the International Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite and

Paper Mill Workers, the local to which all black employees

belonged, was dissolved in 1968. After trial the International

Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite and Paper Mill Workers and United

Papermakers and Paperworkers merged, becoming the United

Paperworkers International Union, AFL-CIO. Their respective

local union numbers remained the same after the merger.

8 The Company reserved certain jobs for whites and other jobs,

the lower-paying, more physically demanding ones, for blacks

(6a). No blacks occupied a previously all-white job until 1967;

no white was assigned to a black job until 1968 (11a).

4 See, e.g., Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397

U.S. 919 (1970) ; United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d

652 (2d Cir. 1971) ; Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791

(4th Cir. 1971), cert, dismissed, 404 U.S. 1006 (1971); United

States v. N.L. Industries, 479 F.2d 354 (8th Cir. 1973).

6

7, 1968, but that on that date such conduct and the effect

thereof ceased. In particular, the court held (a) that the

seniority system as modified in 1968 was adequate to

protect the rights of black employees despite the admitted

continuation of shortcomings requiring further corrective

action in 1972, after this action had been instituted (24a,

25a); (b) that the Company’s testing program was not

discriminatory and was job-related (20a, 27a); and (c)

that there was no evidence of discrimination in mainte

nance, i.e., craft, jobs (18a).5 The opinion made no mention

of the exclusion of blacks from supervisory jobs. The

court concluded that injunctive relief was unnecessary to

assure compliance with Title VII (31a) but retained juris

diction and directed the Company to make periodic reports

to the court “ of its employment activities” (33a). Stating

that “ this litigation has, without doubt, acted as a catalyst

which partially prompted the defendants to take some

action implementing its [sic] own fair employment

policies and seeking compliance with the requirements of

Title V II” , the court awarded the petitioners costs includ

ing counsel fees (34a).

Although petitioners had shown that the class suffered

severe economic loss as a result of respondents’ dis

criminatory practices,6 the court specifically denied back

5 The record shows that at the time of trial there were 253 white

and only two blacks in true craft jobs. Both blacks were appren

tices; there had never been a black journeyman.

6 The District Court found that Black employees had been

assigned lower-paying jobs than white employees (6a). The record

shows 1) that in nearly every department, almost all blacks earned

less than most whites, 2) that in every department the average

hourly rate of whites was higher than the average hourly rate of

blacks, 3) that not one of 112 black hourly-rated employees held

a job with an hourly rate in excess of $4.31, while 404 whites out

of 1081 (37%) held such jobs, and 4) that the average hourly rate

at the time of trial of whites hired in any given year was higher

than the average hourly rate of blacks hired in the same year.

7

pay, relying on United States v. N.L. Industries, 479 F,2d

354 (8th Cir. 1973) (33a-34a).

Petitioners appealed to the United States Court of Ap

peals for the Eighth Circuit,7 which reversed in part,

vacated in part, and remanded (35a-67a). It held as

follows:

(a) Supervisory Personnel: Statistical evidence that

among 160 supervisory employees there was only one black,

an accountant hired in 1969, coupled with the existence of

a selection system that lends itself to racial abuse, was

sufficient to make a prima facie showing of racial dis

crimination, which had not been rebutted by the Company.

Since the District Court in defining the class had excluded

supervisory employees (22a), this aspect of the case was

remanded for further hearings and a determination as to

whether there was racial discrimination in this category

(38a-46a),

(b) Maintenance Craft Jobs: The Company’s use of a

battery of standardized tests as selection devices for main

tenance craft jobs had a disproportionately adverse effect

on black applicants and the Company’s attempt to prove

the tests job-related by means of validation studies was

unsatisfactory in many respects.8 The District Court was

instructed, on remand, to direct the Company to conduct

new validation studies, and if it finds the tests to have

resulted in a racially discriminatory hiring or transfer

policy to devise remedies to give hiring or transfer prefer

ence, as vacancies become available, to those who had

suffered therefrom (48a-55a).

7 Petitioners raised the District Court’s denial of back pay as a

separate point of error in their appeal to the Court of Appeals.

8 Cf. Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody, No. 74-389.

8

The court also found no business necessity for the Com

pany’s present entry level age limitation, together with

a disparate effect on black applicants because of prior

discrimination, and ordered temporary raising of the

maximum age for entry into apprenticeship programs until

the District Court determines that there is sufficient

minority representation in the Company’s maintenance

craft jobs (55a-56a).

(c) Production Jobs: The court held that, in light of the

respondents’ past history of maintaining racially segre

gated lines of progression, with those open to blacks the

lowest paying and least desirable, the continuance of

facially neutral seniority, promotion and transfer policies

continued the effects of past discrimination into the

present. Despite the 1968 changes, which had been deemed

sufficiently curative by the District Court, as well as further

revisions made in 1972, after the trial but before the District

Court decision in the instant case, the Court of Appeals

noted that “no significant movement to rightful places has

been realized by former discriminatees concluded

“that the present transfer, promotion and seniority

practices in the production department at Pine Bluff con

tinue to perpetuate the effects of past discrimination,” and

held that the district court had been in error in denying

injunctive relief (56a-65a).

Accordingly, the Court of Appeals directed that on

remand:

(a) The District Court should ensure full wage pro

tection to affected class members who exercise transfer

opportunities by raising “ red circle” 9 ceilings to realistic

9 “Red Circling” is the name commonly given to the practice

of continuing the wage rates of employees who transfer into other

departments or lines of progression at levels paying lower rates,

so that the temporary drop in wages will not discourage such

9

(b) The District Court should require the Company to

demonstrate which jobs provide essential training for

progression and which could be skipped upon entry and

promotion, so that advancement of victims of previous

discrimination would not be held back by barriers unsup

ported by business necessity.

(c) For the same reason, the District Court should

review the length of the residency requirements in a given

job which employees have to satisfy before being eligible

for advancement to the next higher level, to determine

whether they are the least restrictive means to accomplish

their purpose, and to consider whether functionally equiv

alent experience in former lines of progression may satisfy

those requirements;

(d) The District Court should review the Company’s

practices in advancing victims of racial discrimination to

their rightful place as expeditiously as possible and to the

same extent as it now accords a rightful place to returning

servicemen; and

(e) This relief should be made available to all affected

class members regardless of whether they had declined

transfer offers in the past (65a-66a).

The court then stated: “If these conditions are fully

implemented, the need for a bach pay award will be

o b v ia te d (66a) (Emphasis supplied).

levels (in accordance with a formula set forth by the Court

of Appeals) and extending coverage to class members

previously excluded.

transfers. Apart from its use in other labor-management situa

tions, it has been frequently ordered as an essential ingredient in

the correction of discriminatory seniority and transfer practices.

See, e.g., United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652,

661 (2nd Cir. 1971) ; Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 319 F. Supp.

835, 842 (M. D. N. C. 1970), affirmed, 444 F.2d 791, 796 (4th

Cir. 1971).

10

Both the petitioners and the Company asked the Conrt

of Appeals for rehearing, the petitioners also suggesting

a rehearing en banc. Petitioners specifically sought on re

hearing an award of back pay. In response to the Com

pany’s petition the court made minor changes in the text

of its opinion, and it denied both petitions for rehearing

(68a-71a).

Reasons for Granting the Writ

I

The Case Presents an Important Question of Federal

Law Which Should Be Settled by This Court.

Petitioners and their class suffered loss of income as a

result of employment practices which the Court of Appeals

found to be discriminatory. They will continue to lose

earnings until all present discriminatory practices and

effects of past discrimination have been eradicated. While

the Court of Appeals directed the removal of a number of

racially discriminatory barriers to promotion and transfer,

it denied compensation for the losses they caused in the

past. In holding that the opening up of such opportunities,

in time to come, satisfies the responsibility of the judiciary

to effectuate the purposes of Title VII, the court has ruled

in effect that compensation for monetary loss suffered be

cause of past discrimination may be traded away for

injunctive relief forbidding continued discrimination in the

future.

The rationale of the Court of Appeals, that future in

junctive relief might “ obviate” the “need” for back pay,

is self-contradictory and untenable. Injunctive relief is by

definition-retrospective. No amount of prospective injunc

tive relief can provide class members with compensation

11

for monetary loss suffered in the past (and until the

remedial decree issues). For those older workers who will

be unable to take advantage of the opportunities for ad

vancement which injunctive relief should provide, to deny

back pay is to deny the only meaningful relief afforded by

Title VII for a lifetime of discrimination.

In Title VII cases as in other civil rights areas, “ the

court has not merely the power but the duty to render a

decree which will so far as possible eliminate the dis

criminatory effects of the past as well as bar like dis

crimination in the future.” Louisiana v. United States, 380

U.S. 145, 154 (1965). Back pay, to redress economic harm

caused by unlawful employment discrimination, has here

tofore been unifoi'mly regarded as an essential component

of the remedies available in order to make the victims

whole. In reviewing the judicial construction of Title VII

and recommending the adoption of the Equal Oppor

tunity Act of 1972, P. L. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103,10 the Con

ference Committee, in its section-by-section analysis,

stressed the importance of full remedial relief:

The provisions of this subsection are intended to

give the courts wide discretion exercising their equi

table powers to fashion the most complete relief pos

sible. In dealing with the present section 706(g) the

courts have stressed that the scope of relief under that

section of the Act is intended to make the victims of

unlawful discrimination ivhole, and that the attainment

of this objective rests not only upon the elimination

of the particular unlawful employment practice com

plained of, but also requires that persons aggrieved

i° While the 1972 law amended Title VII of the Civil Eights Act

of 1964 in a number of respects, none of the changes bears upon

the back pay issue as it arises in the instant case, and if the holding

below is allowed to stand it would be equally applicable to the

amended statute.

12

by the consequences and effects of the unlawful em

ployment practice be, so far as possible, restored to a

position where they would have been were it not for

the unlawful discrimination (emphasis supplied). 118

Cong. Rec. 7168 (1972); see also 118 Cong. Rec. 4942

(1972) (Seetion-by-Section Analysis introduced into

Record by Sen. Williams).

The decision of the court below, so long as it stands

unreversed, will constitute a serious threat to the effectua

tion o f a Congressional policy of utmost national im

portance.

II

The Decision Below Is in Conflict With the Decisions

o f Other Courts o f Appeals on the Same Matter.

The courts of appeals of five other circuits have consis

tently awarded both injunctive relief and hack pay in cases

strikingly similar to the instant case. Back pay was

awarded, along with injunctions against continued use of

discriminatory seniority systems and invalid tests, in

Moody v. Albemarle Payer Co., 474 F.2d 134 (4th Cir.

1973) ,11 cert, granted,------ U .S .------- , 95 S.Ct. 654 (Dec. 16,

1974) ; United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906

(5th Cir. 1973),12 Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 11 12

11 “ . . . a plaintiff or a complaining class who is successful in

obtaining an injunction under Title Y U of the Act should

ordinarily be awarded hack pay unless special circumstances would

render such an award unjust.” 474 F.2d at 142.

12 “ Given this Court’s holding that £ [a] n inextricable part of

the restoration to prior [or lawful] status is the payment of back

wages . . .’ it becomes apparent that this form of relief may not

properly be regarded as a mere adjunct of some more basic equity.

It is properly viewed as an integral part of the whole of relief. . . .”

474 F.2d at 921.

13

491 F.2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974),13 and Pettway v. American

Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974). Back pay

was combined with injunctions against invalid seniority

practices in Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th

Cir. 1971), cert, dismissed, 404 U.S. 1006 (1971); and

Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., 484 F.2d 870 (6th Cir.

1973). Back pay, and an injunction against an unwarranted

weight lifting requirement that discriminated against

women and an improper seniority program, were combined

in Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711 (7th Cir.

1969), 489 F.2d 896 (7th Cir. 1973). And in Rosen v. Public

Service Gas & Electric Co., 477 F.2d 90 (3d Cir. 1973),

back pay accompanied an injunction against continuation

of a discriminatory pension system.

All of these cases conflict with the holding of the court

below that comprehensive injunctive relief obviates the

necessity of back pay.13 14

13 “Where employment discrimination has been clearly demon

strated . . . victims of that discrimination must be compensated if

financial loss can be established. . . . To implement the purposes

behind Title VII, a court should give ‘a wide scope to the act in

order to remedy, as much as possible,. the plight of persons who

have suffered from discrimination in employment opportunities.’ ”

(footnote omitted). 491 F.2d at 1375,

14 There is an additional conflict- in the circuits if the denial of

back pay for the reason stated by the Court of Appeals was

intended to apply only to blacks excluded from production jobs.

(It may be noted that the sentence stating that “ the need for a

back pay award will be obviated” appears at the close of the

section of the opinion relating to production jobs (56a-66a). If so,

the failure of the court to reverse the District Court’s blanket

refusal to grant back pay may be deemed an affirmance of that

aspect of the District Court’s decision to the extent that it applied

to other categories of -employment, i.e., supervisory and main

tenance jobs.

That refusal, in turn, was based on an earlier decision of the

Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, United States v. N.L.

Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354, 380 (1973), in which back pay was

withheld because “ [i]n this Circuit the law in regard to back pay

has not been adequately defined to provide employers and unions

14

III

Efficient Judicial Administration W ould Be Served

if This Court Will Grant Certiorari, Vacate the Judg

ment Below, and Remand for Further Consideration in

the Light o f This Court’s Decision in Albemarle Paper

Company v. Moody and Halifax Local No. 425, United

Papermakers and Paperworkers, AFL-CIO v. Moody.

The two petitions for certiorari in Moody referred to

above were granted, and the cases were consolidated,

briefed and argued, and are now awaiting decision. (Doc

ket Nos. 74-389 and 74-428.) The question of the standards

that should govern the awarding of back pay was one of

the two issues raised in the first of these petitions and the

only issue raised in the second. If, as appears probable,

this Court decides that issue, almost inevitably its decision

and opinion will at least cast some light on the propriety

of the denial of back pay in the instant case and may well

be dispositive of it. It would be wasteful of judicial time

and effort and of the labors of counsel to deny certiorari

and thus allow the case to be remanded to the district court

for further proceedings under instructions that take no

account of the rulings to be made by this Court on the

very subject in dispute.

with notice that they will be liable for a discriminatee’s economic

losses. . . Such a limitation on back pay has been expressly

rejected by other circuits: “ [T]he unsettled nature of the law

applicable to a particular employment practice does not constitute

a legally cognizable defense to a claim for back pay in a Title VII

suit.” Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364,

1375 (5th Cir. 1974) Accord: Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444

F.2d 791, 804 (4th Cir. 1971). It is also inconsistent with each of

the cases cited in the text above which was the first in its respective

circuit to hold the practices complained of illegal, and with this

Court’s rejection of “good intent or absence of discriminatory

intent” as defenses, in Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S 424

432 (1971).

15

We therefore respectfully urge that this Court grant the

writ, and that if the Court decides the merits of the afore

mentioned Moody cases in a manner consistent with the

position of petitioners herein, it summarily vacate the

judgment below insofar as it fails to grant back pay and

remand for further consideration in the light of that

decision.

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, a writ of certiorari should be issued

to review the judgment and opinion of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

J ohn W . W alker

P hilip K aplan

Walker, Kaplan & Mays

622 Pyramid Life Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

J ack Greenberg

Morris J. Baller

Deborah M. Greenberg

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioners

A lbert R osenthal

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Of Counsel

A P P E N D I X

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

E astern District oe A rkansas

P ine Blijef D ivision

No. PB 71-047

Opinion o f District Court

H enry Lee R ogers, L ee Chester Smith, and N. A. T homp

son, Individually and on behalf of other persons simi

larly situated,

Plaintiffs,

v.

International P aper Company, P ine Bluff, A rkansas,

and

I nternational Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite and Paper

Mill W orkers, AFL-CIO; L ocals 898 and 946 of T he

International Brotherhood of P ulp, Sulphite and

P aper Mill W orkers; United P apermakers and P aper-

workers, AFL-CIO; L ocals 731, 735 and 833 United

Papermakers and P aperworkers, P ine Bluff, A rkan

sas; and I nternational Brotherhood of Electrical

W orkers,

Defendants.

Memorandum Opinion

The plaintiffs filed this class action proceeding pursuant

to 28 U.S.C. 4 1343(4); 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(e) and ( f ) ; and

28 U.S.C. §§2201 and 2202. The named plaintiffs are

2a

black employees of the defendant, International Paper

Company (hereinafter called “I.P.” ), and bring this action

on behalf of themselves and other blacks similarly situated,

pursuant to Pule 23(b)(2) of the Federal Pules of Civil

Procedure.

In addition, this is a suit in equity under the provisions

of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§§ 2000e, et seq. The plaintiffs invoke the jurisdiction of

this Court to secure protection of and to redress depriva

tion of rights secured by (a) 42 U.S.C. §§ 2Q00e, et seq.,

providing' for injunctive and other relief against racial

discrimination in employment, (b) 42 U.S.C. § 1981, pro

viding for the equal rights of all persons in every state and

territory within the jurisdiction of the United States, and

(c) the duty of fair representation, 29 U.S.C. §§ 151, et seq.

The class which the plaintiffs represent is composed

of black persons employed or who might seek employment

by I.P. at its manufacturing facilities in Pine Bluff,

Arkansas, and who have been and continue to be or might

be adversely affected by the practices complained of. The

plaintiffs also bring this action on behalf of the black mem

bers of the International Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite

and Paper Mill Workers, AFL-CIO, Locals 898 and 946,

International Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite and Paper

Mill Workers, United Papermakers and Paperworkers,

AFL-CIO, and Locals 731, 735, and 833, United Paper-

makers and Paperworkers, Pine Bluff, Arkansas and Inter

national Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, AFL-CIO, and

Local 2033, International Brotherhood of Electrical

Workers, who have been and continue to be or might be

adversely affected by the practices complained of.

The plaintiffs allege that there are common questions of

law and fact affecting the rights of members of their class

who are and continue to be limited, classified, discriminated

Opinion of District Court

3a

against and refused employment and which deprive and

tend to deprive them of equal employment opportunities

and, otherwise adversely affect their status as employees

because of their race and color. These persons are so

numerous that joinder of all members is impracticable.

A common relief is sought, and the interests of the class

are adequately represented by the plaintiffs.

The nature of the claim is for declaratory relief, with

permanent injunction requested, restraining all of the defen

dants from continuing policies and practices discriminating

against the plaintiffs and other blacks with respect to hir

ing, compensation, terms and conditions of employment;

limiting, segregating and classifying employees in ways

that deny the members of the class their equal employ

ment and, otherwise adversely affecting their status as

employees or prospective employees; refusing to promote

because of race; demoting because of race; merging for

merly segregated unions without provision for protection

of the formerly all black unions; and by excluding plain

tiffs and members of their class from union membership

because of their race.

The named plaintiffs are black citizens of the State of

Arkansas, and employees of I.P., located at Pine Bluff,

Arkansas, who have filed charges of discrimination with

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission pursuant

to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 against the

defendant Company and unions and who have received

notice of their right to bring this action.

The defendant, I.P., Pine Bluff, Arkansas, is a branch

of a private corporation doing business in the State of

Arkansas and the City of Pine Bluff. The Pine Bluff facility

is an employer within the meaning of 42 U.S.C. § 20Q0e (b)

in that the Company is engaged in an industry affecting-

commerce and employs at least 25 persons.

Opinion of District Court

4a

The defendants organized as international unions are

labor organizations which exist in whole or in part for the

purpose of dealing with International Paper Company con

cerning grievances, labor disputes, wages, rates of pay,

hours and other terms and conditions of employment of

employees of the Company at its facilities in and around

the City of Pine Bluff in the State of Arkansas. The defen

dant Locals are agents and affiliates of international unions

and exist in whole or in part for the same purposes as the

international union.

On June 29, 1971, I.P. filed a Motion to Dismiss or, alter

natively, a Motion to Stay the Proceeding pending further

conciliation efforts by the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission (EEOC). Although the Motion to Dismiss was

predicated upon several grounds, it was in essence, a chal

lenge to the procedural steps taken by plaintiffs as a proper

basis for the filing of the Complaint in this case. The Pulp

and Sulphite Workers and the Papermakers likewise filed

a Motion to Dismiss the Complaint on the ground that the

Court lacked jurisdiction over the parties. Both of these

motions were denied by the Court in its Order of October

22, 1971.

The defendant, I.P., and defendant unions filed answers,

respectively, consisting of general denials of the material

allegations of the plaintiffs’ complaint with regard to dis

crimination in employment and in union activities but, also,

raised the specific questions of whether or not plaintiffs

have exhausted their remedies prior to invoking the juris

diction of this Court; whether or not they have standing

to represent the class referred to in the Complaint; and

whether or not both I.P. and defendant unions have elim

inated remaining vestiges of alleged prior discrimination

Opinion of District Court

5a

by the adoption and implementation of a document known

as the “ Jackson Memorandum of Understanding” (herein

after Jackson Memorandum).

The trial of the case was scheduled in November, 1971,

but was continued to permit the parties to engage in exten

sive pre-trial discovery in the form of depositions and

interrogatories. Subsequently, the Court scheduled the case

for trial commencing the week of February 7, 1972. Just

prior to the trial of the case, the plaintiffs filed a Motion

to sever all questions pertaining to back pay and requested

that a master be 'appointed by the Court to take evidence

and present findings of fact with respect to that issue. The

defendants, in responding to the Motion, strongly con

tended that the plaintiffs were not entitled to money dam

ages or back pay and affirmatively pleaded the statute of

limitations and the equitable doctrine of laches as a com

plete bar to any back pay claim. The Court, in granting

the Motion to sever, entered an Order on November 28,

1972, but did not grant the request for a master to be

appointed regarding the back pay issue.

The trial of the case consumed the weeks of February 7,

and March 20, 1972. The Court heard extensive oral evi

dence and received innumerable exhibits. Plaintiffs filed

a Motion to Dismiss Pulp and Sulphite Workers and its

Locals 898 and 946, and Papermakers and its Locals 731,

735, and 833, based upon an agreement attached to the

Motion to Dismiss. The basis of the agreement was that

all issues raised in the pleadings with respect to the parties

thereto had been settled and that -the action should, there

fore, be dismissed with respect to these defendants. Defen

dants I.P. and IBEW opposed the Motion and a formal

Order was entered by the Court on November 28, 1972,

denying the Motion.

Opinion of District Court

6a

The Pine Bluff Paper Mill is a substantial operation

primarily engaged in the treatment of wood and, through

extensive process, converts it into paper. It is one of a

number of such facilities maintained and operated by the

defendant I.P.

The Pine Bluff Paper Mill was constructed and began

production in August, 1958. Many of the employees, and

especially skilled and 'supervisory employees were trans

ferred from other facilities operated by the Company. The

remainder of the jobs, including some highly-skilled posi

tions, were filled by employees newly hired by the Com

pany at that time.

Jefferson County, Arkansas, in which the paper mill is

located, has at all times relevant to this litigation had a

'Substantial black population. It is undisputed that the

initial staffing of the paper mill was made along strict racial

lines as a matter of Company policy, with some job cate

gories reserved solely for white employees and some for

blacks.

The job categories assigned to black employees were

generally lower-paying, more physically demanding, and,

generally less desirable than those assigned to whites. Em

ployee facilities at the paper mill, such as lunchrooms and

other service facilities, were operated on a strictly segre

gated basis.

The paper mill and job assignments for its operation

are divided into several departments, each consisting of

various jobs, having a close functional relationship with

each other and usually operating with a distinct geographic

area.

Most job assignments in the paper mill were organized

into lines of progression (hereinafter sometimes referred

to as “LOP’s” ), under which an employee assigned to a

particular LOP would progress from one job assignment

Opinion of District Court

7a

to another along the LOP in a predetermined sequence.

LOP’s were organized in accordance with a number of

criteria including, sometimes in combination and sometimes

singly, location, department, function, relationship of skills,

wages and the traditions of the Southern paper mill in

dustry.

There were a number of jobs in the paper mill which

were not assigned to any line of progression. Among these

were the laborers jobs, some of which were assigned to work

with each of various LOP’s or in various departments, and

managerial and 'supervisory personnel. As an example, the

woodyard department consisted from employees from two

LOP’s, the woodyard LOP and the equipment LOP, to

gether with a laborer complement. The woodyard LOP and

the woodyard labor pool initially were all black, while the

equipment LOP was all white.

Jobs in the woodyard LOP, the equipment LOP, and the

woodyard labor pool, were and are very closely related

functionally, and employees assigned to all those jobs

work in conjunction with each other on a daily basis. The

only distinction between the two LOP’s located within the

woodyard, other than the racial one indicated above, was

that job categories in the equipment LOP received higher

wages than those in the woodyard LOP.

The pulp mill LOP was staffed solely by white employees.

A small number of job assignments functionally related

exclusively to those in the pulp mill LOP were filled solely

by blacks, such as the “ lime wheeler” . These black-staffed

jobs were not included in the pulp mill LOP.

The beater room LOP was staffed solely by white em

ployees............

The paper machine LOP, the most highly paid LOP

in the paper mill, was staffed solely by whites. A group of

Opinion of District Court

8a

black laborers worked with the members of the paper ma

chine LOP but were not assigned to it.

The LOP of the polyethylene extruder, added sometime

after the opening of the paper mill in 1958, was staffed

solely by whites.

This method of assignment and job classification pre

vailed throughout the facility wherein the whites were

assigned to specific jobs and other specific assignments to

blacks. The guard force consisted of white employees as

did the managerial and supervisory employees. Neither of

these were organized into LOP’s, although the testimony

revealed that there were recurring patterns for promotion

from one job assignment to another as is common practice

in managerial structures.

The International Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite, and

Paper Mill Workers represented the employees in the

woodyard and pulp mill. Its Local 946 represented black

employees, and its Local 898 represented whites in the

pulp mill and in the laboratory LOP. In order to bring

the continued operation of their local unions in compliance

with the law, the defendant, International Union of Pulp,

Sulphite, and Paper Mill Workers ordered a merger of the

two locals. They were merged into one local and continues

as Local 898. Local 946 was dissolved.

The defendant, International Brotherhood of United

Papermakers and Paperworkers represented their mem

bers employed by I.P. through their Local 731, 735, and

833. Black members of the union suffered similar dis

crimination in the operations of their labor organization.

The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers

and its Local 2033 represented the employees in the elec

trical, instrument and power plant LOP’s. The guards,

and office and clerical employees, were not represented by

Opinion of District Court

9a

any of the union® as parties to this litigation. The man

agerial and supervisory employees were not, and are not,

represented by any labor organization.

The defendant, I.P., has, at all times pertinent to this

litigation, had exclusive control over the hiring for all jobs,

whether represented or not represented. The Company re

tains for itself the right to establish the minimum require

ments and standards for all applicants for employment as

well as the right to make decisions regarding placement

of employees in labor pools or positions within the plant.

Once hired, an employee’s movements from one job assign

ment to another, among those jobs whose occupants are

represented by any of the labor organizations wrho are

parties defendant, are and have been controlled by pro

visions of a series of collective bargaining agreements

entered into by the defendants. Under the collective bar

gaining agreements, each employee accrues three (3) types

of seniority, to-wit: company seniority, the length of time

he has been continuously employed by I .P .; department

seniority, the length of time he has been permanently and

continuously assigned to a particular LO P; and job senior

ity, the time he has spent permanently and continuously

assigned to a given job slot. Periods during which an em

ployee may have been laid off are included in figuring

company seniority, but not department or job seniority.

In order to enter a LOP, whether from another LOP

or from a job outside any LOP, employees have historically

competed on the basis of company seniority. If there was

a permanent vacancy in a LOP, the employee with the

greatest company seniority, who indicated his desire for

it, would receive the assignment, if he was of the race for

which the LOP was reserved. After the plant was initially

Opinion of District Court

10a

staffed, an employee newly assigned to a LOP entered it

by being assigned to its lowest-paying job.

Once in a LOP, employees competed for progression

from one permanent job assignment to the next highest-

paying one in the LOP on the basis of their job seniority.

The employee with the greatest tenure of permanent as

signment to the job slot immediately below the vacancy

would receive the assignment. If job seniority were equal,

greater departmental seniority would control; if both were

equal, greater company seniority would control. This re

sulted from an entry level job of lower pay to an ascending

scale of pay.

From 1958 until 1962, black employees of the defendant,

I.P., were not permitted entry level jobs in any LOP except

the woodyard. As late as 1971, the woodyard was the next

to lowest pay when measured by LOP hourly wage.

In 1962 Executive Order 10925 was promulgated which,

in effect, prohibited government contractors from discrim

inating against any employee because of race, color, creed

or national origin. The International Paper Company be

came subject to the Executive Order as a substantial con

tractor. I.P. responded promptly to the requirements of

the Executive Order and announced that henceforth there

would be no segregation of its facilities and that all LOP’s

were open to all employees without regard to race, color,

or national origin. It was of such import to I.P. that

officials from the division level toured each of the mills in

its Southern Kraft Division, including Pine Bluff, and met

with local mill management and employee representatives,

including black union leaders, as a means for announcing

the new policy required by Executive Order 10925. The

Company began immediately the desegregation of its facil

Opinion of District Court

11a

ities which has long since been accomplished and is not

an issue in this case. In addition, the Company further

announced a policy of recruitment of individuals without

regard to race or color, and a promotion policy which

eliminated race as a factor.

With these announced changes in policy, black em

ployees, who demonstrated potential ability to perform

jobs in a line of progression under I.P.’s testing program,

and who so desired, could transfer under the Labor Agree

ment with the unions to former predominantly white jobs.

There was some movement of incumbent blacks into some

of the predominantly white positions.

The transition was slow. Desegregation of Company

facilities was not completed until 1966. The first black em

ployee who was permanently assigned to a previously all-

white job did not occur until 1967. The first white em

ployee assigned to a formerly all-black job was made on

a permanent basis in 1968.

Because of the operation of the contract’s seniority pro

visions, any black employee who entered a previously all-

white LOP as late as 1967 would remain behind the white

employees who entered the line of progression before him,

notwithstanding the fact that the white employee may have

been employed several years after the black employee.

As a result of the continuing effect of past discrimina

tion, and a 1968 District Court decision, in TJ.S. v. Local

189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers, 282 F. Supp.

39 (E.D. La. March 1968), the Office of Federal Contract

Compliance (OFCC) undertook the acceptance of an agree

ment, by I.P. and the unions, to modify the effects of the

contract seniority provisions. Discussions took place be

tween OFCC and the Company toward providing incum

bent blacks with additional opportunities for advancement

Opinion of District Court

12a

in employment throughout the Southern Kraft Division

of I.P.

A special conference was called in Jackson, Mississippi,

in June, 1968. Top management of the Company and labor

organizations, which included representatives of manage

ment and labor for each of the mills in the Southern Kraft

Division of I.P., participated in the conference; since the

conference was instigated by OFCC, government repre

sentatives also participated in the discussions. Repre

sentatives of black employees were in attendance at the

conference as delegates and participated in the discussions.

There was some testimony that the blacks were present

as “ observers” and not as official representatives of the

black employees.

During the course of the conference, the Office of Fed

eral Contract Compliance presented twelve points to the

Company and unions as a basis for their discussion of

necessary and appropriate changes which should be made

to their existing Labor Agreements. The negotiations pro

duced an agreement called the “Memorandum of Under

standing” or “Jackson Memorandum” . Pursuant to the

“ Jackson Memorandum”, the parties agreed to revise the

basic Labor Agreements and employment practices, al

leviating some of the continuing effects of the defendants’

past discriminatory practices. The Jackson Memorandum

was circulated at the various mills of the Southern Kraft

Division, including Pine Bluff, and was ratified by the

local unions at all mills.

The OFCC adopted the position that the Jackson Memo

randum was sufficient for compliance with Executive Order

112461 without the need for further collective bargaining

Opinion of District Court

1 Executive Order 11246 superseded Executive Order 10925.

13a

beyond the agreed changes included in the Memorandum.

The primary impact of the Jackson Memorandum was to

identify an “ affected class” of employees (hereinafter re

ferred to as “AC” ), and to displace the old job seniority

system with a mill seniority system, whereby members of

AC compete with other employees for promotion, trans

fer, and other personnel actions on the basis of mill se

niority. This took the place of the old policy of competing

on the basis of job or departmental seniority.

The Jackson Memorandum also contained a provision

to the effect that the Company and the unions, at each

plant, would conduct further negotiations toward an agree

ment on restructuring of the LOP’s, so that the formerly

all-black jobs were integrated into longer LOP’s also con

taining traditionally white jobs. However, if competition

between an affected class member and a non-affected class

member does not exist, the Jackson Memorandum provides

that the traditionally contract seniority applies.

Members of the affected class are identified, or defined,

as those black employees hired prior to September 1, 1962,

or employed thereafter, but prior to the date of the Jack-

son Memorandum, and initially placed in a job or line of

progression which was formerly a predominantly black job

or line.

The Jackson Memorandum contains a further provision

that all current employees are eligible for transfers or ad

vancement into a line of progression if they possess qual

ifications equal to the minimally qualified employee cur

rently working in that line. Testing was deleted as a

requirement for incumbent employees to be eligible for

transfer to or entry into any production line of progres

sion. It further provides for affected class transfer under

Opinion of District Court

14a

a “ red-circle” rate which protects against wage loss in the

event the desired transfer is to a lower paying job.

Subsequently, the OFCC submitted a letter of expla

nation of the Jackson Memorandum written by the acting

Director and became known as the “McCreedy letter” . It

was made clear that no skipping of job assignments within

a LOP or entry to a LOP at other than the lowest-paying

job was to be permitted. Designation of a job opening as

a “ temporary” or “permanent” one had always and was

still made solely by the Company. Assignments upwards

along a LOP designated as “ temporary” had often lasted

long periods of time, and, in some cases, even longer than

a year.

As a result of these practices, some employees spent

large portions of their working time “temporarily” as

signed to jobs one or more steps in a LOP above their

“permanent” assignment. The effect was that some spent

a lot of their time “ temporarily” assigned to higher-level

jobs.

The so-called McCreedy letter gave some significance to

this distinction between a “permanent” and a “temporary”

job assignment. Only an employee “permanently” assigned

to a given job slot was eligible for assignment to the next

higher slot.

Some of the rights granted to black employees by the

Jackson Memorandum depended on some affirmative action

on the part of the employee to obtain them. Shortly after

the adoption of the Jackson Memorandum, August 7, 1968,

the Personnel Department of the Pine Bluff mill of I.P.

interviewed, individually, all affected class employees in

order to advise them of their rights and, in an attempt to

determine from them their interest in transferring from

Opinion of District Court

Opinion of District Court

the line in which they were working, at that time, to another

line of progression. As to those which were not in a line

of progression, an effort was made by the Personnel De

partment to determine the lines of progression into which

they desired to enter, if any.

Written applications were prepared for AC’s who de

sired to transfer, or to he promoted; these applications

were retained in the Personnel Office for reference if va

cancies occurred. There were some instances of job re

fusals by black employees, whereby the employees allegedly

indicated their refusal to be assigned to jobs higher in the

LOP than their then-current assignment. AC’s, who ini

tially said they were not interested in transferring or

moving up were, subsequently, contacted again to deter

mine if they desired then to exercise their rights under

the Jackson Memorandum.

Subsequently, the Company agreed to post throughout

the plant notices for seven days of all permanent vacan

cies in entry level jobs as well as for temporary vacancies

which were expected to last more than thirty days. Copies

of these notices were made available to each of the local

unions. All employees could apply for any vacancy that

was posted. Competition between applicants, e.g., em

ployees who had previously expressed a desire for that

line of progression, and employees in the labor pool serv

ing that line of progression was resolved on the basis of

mill seniority as provided by the terms of the Jackson

Memorandum.

There was substantial statistical data furnished by both

parties. The plaintiffs attempted to show a “ lock in” effect

of prior practices. However, I.P. contends that such re

sult, if any, was from failure of more complete utilization

by affected class employees of opportunities afforded under

16a

the remedial relief measures agreed to by the defendants,

I.P. and unions.

In any event, the Court is impressed with the fact that

there was statistical data which shows some permanent

movement by AC’s into formerly predominantly white jobs

and, also, movement via posted temporary vacancies, i.e.,

those expected to last over thirty days. In view of the fre

quently recurring vacancies, employees classified at one

job level often received temporary promotions to the next

higher job where they may have an opportunity for an

even higher temporary promotion. It is quite clear, how

ever, that there are a great many more temporary vacan

cies of less than thirty days which AC’s fill in accordance

with the terms of the Jackson Memorandum. The Court is

persuaded and concludes, from all the evidence, that a

qualified AC who desires promotion or transfer to better

jobs, under the Jackson Memorandum, has had the oppor

tunity to do so provided his mill seniority was greater than

others applying for the same vacancy. It is further noted,

from the record, that there are those who have not declined

promotion who have received one or more promotions.

Numerous exhibits have been received in the record il

lustrating how effective the Jackson Memorandum has been

in precipitating accelerated movement of the affected class.

The record discloses that, as a result of the Jackson Memo

randum, there has been substantial movement of black em

ployees into the lines of progression. This has not been

without some difficulty. However, it has served substan

tially toward achieving the intended purpose.

Where an affected class member was in competition with

a non-affected class member, under the Jackson Memoran

dum, the AC received the job. There is no substantial evi

dence to the effect that a qualified senior AC failed to re

Opinion of District Court

Opinion of District Court

ceive a job sought by him. There are instances wherein

claims have been made which raise the question of qualifi

cations or, in some cases, fear as to the ultimate result.

Nevertheless, the ultimate result has been that the AC’s

have either received advancement or transfer on their re

quest under the Jackson Memorandum, or have voluntarily

declined transfer and, in some cases, removed themselves

from contention in other jobs. The record discloses, and

the Court concludes, that the Jackson Memorandum has

served as an effectual instrument toward eradication of the

effects of past discrimination.

Even though the Court concludes from the evidence in

the case that the Jackson Memorandum, as modified by the

McCreedy letter, has provided remedial relief against the

residual effects of past practices engaged in by the Com

pany and the unions, and that I.P. and the unions have, in

good faith, undertaken implementation, it developed that

there were yet some steps to be taken toward the elimina

tion of the last vestiges that remained from the effects of

past discrimination.

In recognition of the need for further revision of pro

cedures within the various mills of the defendant, Inter

national Paper Company, a second Jackson conference was

convened in June, 1972, under the auspices of the OECC.

The Southern Kraft Division of the defendant, Inter

national Paper Company, and paper production unions,

representing the various I.P. mills, negotiated a new Memo

randum of Understanding.2 There were some ten (10)

mills, including the Pine Bluff mill, in the Southern Kraft

Division of the International Paper Company affected by

the revisions to the “ Jackson Memorandum” . Although the

2 A revision, supplementing the original Memorandum of Under

standing.

18a

plaintiffs claim they were not represented at these negotia

tions, it is an established fact that members of the black

race were in attendance as observers.

The “McCreedy letter” complained of by the plaintiffs

had been partially nullified to the effect that temporary

service on the jobs began the basis for competition for

permanent vacancies. In fact, the 1972 Memorandum elim

inated the consequences of the distinction between “tem

porary” and “ permanent” job assignments. Further, the

recall provisions of the McCreedy letter were nullified.

The parties were authorized, subject to approval of OFCC,

to identify jobs which may be skipped or jobs which may

be entered at an advanced level in certain lines of pro

gression. The definition of the affected class was enlarged

and a new, substantially higher, red-circle rate was adopted.

Pursuant to the revised Jackson Memorandum, an agree

ment was entered into by the defendants so as to provide

seniority protection for a period of six (6) months for an

affected class employee who transfers from a line of pro

gression to the Maintenance Department as an apprentice.

These additional procedures, included in the revision, were

adopted in order that greater equal employment oppor

tunities, as they evolve, would occur and consequently

remove, voluntarily, any and all vestige of past discrim

ination.

The plaintiffs contend that the revised Jackson Memo

randum was inadequate as a matter of law because it did

not apply to Maintenance Departments. The OFCC had

previously determined that there was no evidence of dis

crimination against blacks in the maintenance crafts. Thus,

OFCC did not request any action be taken in the Jackson

conference affecting employees in the Maintenance De

Opinion of District Court

19a

partments. The testimony fails to disclose that there has

been overt discrimination in these departments.

The defendant, I.P., initiated certain testing require

ments as prerequisites for hiring or promotion. Testing

requirements remain as prerequisites for most of the jobs

at the paper mill today. The test used in the Production

and Maintenance Departments are as follows:

Production

Wonderlic Personnel Test—15

Bennett Test of Mechanical Comprehension

(Form A A )—20

or

Bennett Test of Mechanical Comprehension

(Form BB)— 12

Maintenance

Wonderlic Personnel Test—18

Bennett Test of Mechanical Comprehension

(Form A A )—45

or

Bennett Test of Mechanical Comprehension

(Form B B )— 37

Minnesota Paper Form Board Test—45.

These tests are administered in a controlled atmosphere

by a test coordinator who follows the procedures outlined

in the manuals prepared by the test publishers. Although

there has been no challenge to the manner of administra

tion, or scoring, of the Company’s personnel testing, the

plaintiffs contend that they operate so as to disqualify

blacks at a significantly higher rate than whites from hir

Opinion of District Court

20a

ing, promotion, and transfer. The Court concludes the

evidence is insufficient to show any substantial impact of

the Company’s testing program as to the ability of blacks

to obtain employment at the defendant’s Pine Bluff mill.

More recently, the Company has initiated a comprehensive

process of validating its production and maintenance tests

by the criterion-related method of test validation. Through

this method, the Company has established a reasonable

procedure for a determination of an applicant’s capability

to perform, successfully, particular jobs. This method of

test validation is recognized in the profession and as gov

ernmental guidelines for employee selection. EEOC, Guide

lines on Employee Selection Procedures, 29 C.F.R. § 1607.1,

et seq.; OFCC, Employee Testing Other Selection Proce

dures, 41 C.F.R. § 60-3.1, et seq.

Finally, the plaintiffs presented testimony to the effect

that various members of the class had been the victims of

discrimination on a personal, or individual, basis solely

because of their race. The Court has given special atten

tion, and somewhat critically, to the claims in each in

dividual instance; the Court agrees that, from the testi

mony, it is clear that two basic factors characterize these

charges of discrimination. First, it is apparent that they

stem from misapprehension of the defendant’s, I.P., em

ployment practices. In the second place, they were not

processed through, admittedly, available grievance chan

nels. The Court, therefore, concludes that neither the Com

pany, nor the defendant unions, are now giving any con

sideration to black employees for special treatment in a

discriminatory manner. All employees, both black and

white, are provided protection under present collective bar

gaining agreements, pursuant to the Jackson Memorandum

Opinion of District Court

21a

of Understanding, and are, thus, provided remedy for ap

propriate and good faith complaints.

Numerous witnesses on behalf of the plaintiffs, includ

ing Mr. Henry Lee Rogers, plaintiff, Mr. Fair and Mr.

Randle, admitted that they were members of the union and

were aware of their rights under the Contract as to griev

ance procedures. They testified that they had free access

to the personnel office and the plaintiff, Rogers, admitted

that he had been benefited monetarily by the filing and

processing of the grievance. Although harassment has been

claimed by some of the plaintiffs, the testimony discloses

that, since the adoption of these protective procedures pur

suant to the Jackson Memorandum, no grievances have

been filed by any member of the affected class alleging

harassment or racial discrimination.

From the substantial testimony presented, ore tenus,

during the trial of the ease, innumerable exhibits by all

parties, stipulations, and the entire record, the Court makes

the following conclusions of law:

1. The Court has jurisdiction of this action pursuant to

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f); 42 U.S.C. §1381; 28 U.S.C. §1343

(4 ); 28 U.S.C. §§ 2201 and 2202.

2. International Paper Company is an employer in an

industry affecting interstate commerce within the meaning

of § 701(b) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§2Q00e(b); the defendant labor unions are organizations

engaged in an industry affecting commerce within the

meaning of § 701(d) and (e) of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.'S.C. §2000e(d) and (e).

3. Plaintiffs have complied with the procedural require

ments of § 706(a), (d) and (e) of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(d) and (e).

Opinion of District Court

22a

4. This proceeding is a proper class action pursuant

to Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The

class is defined as follows:

“Those black employees employed and still employed

since the commencement of this cause and all future

employees of International Paper Company at its Pine

Bluff, Arkansas, mill who are members or eligible to

be members of Pulp and Sulphite W orkers; Locals 898

and 946; Papermakers; Locals 731, 735, and 833; and

IBEW ” .

5. The defendants, which are local unions, are for the

purpose of this litigation, the agents of their respective

international unions.

6. The defendant, International Paper Company, has a

historical policy of hiring only blacks for certain jobs in

the production of paper and related products in their

various mills, including Pine Bluff, and only whites for

other jobs within their mill operations, which constituted

racial discrimination against black employees and, would

be black employees. This historical policy of discrimina

tion has been consistently reflected in collective bargaining

agreements between the defendant, I.P., and the defendant

unions.

7. The Pine Bluff paper mill was constructed, and com

menced operation, in 1958. The historical policy of dis

crimination, or effects of such past discrimination, con

tinued unabated until August 7, 1968.

8. Discrimination, as consistently practiced within the

operation of the defendant’s paper mill, constitutes an un

Opinion of District Court

23a

lawful employment practice under the Civil Eights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2Q00e-2(a) and (c).

9. The collective bargaining agreements entered into

periodically between the Company and the unions have had

the effect of perpetuating past discrimination, or the effects

of past discriminatory policies, since, under the terms of

the agreements, qualified black employees employed prior

to white employees remain at job levels on the various lines

of progression below those white employees.

10. Employment practices which perpetuate, or tend to

perpetuate, past discrimination are forbidden, by Title VII,

to the extent that they are not supported by overriding

legitimate, non-racial business necessity. Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971); Rowe v. General Motors

Corp., 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972).

11. The seniority system, as developed during the years

of operation of the International Paper Mill at Pine Bluff,

and which was agreed to by all of the defendants, has con

sistently been a condition of employment which discrim

inates against blacks in violation of Title V II of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964.

In view of the ratification, and becoming parties to var

ious collective bargaining agreements incorporating the

seniority system after the effective date of Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, unlawful, discriminatory em

ployment practices, and the effect of past discriminatory

practices, continued until August 7, 1968.

12. The defendant’s failure to institute adequate re

medial measures, after the adoption of the Civil Rights Act

Opinion of District Court

24a

of 1964, Title VII, was a continuing violation of Title VII

until the adoption of the two Memorandums of Under

standing referred to as “Jackson Memorandum” , first

adopted August 7, 1968, and revised June, 1972.

13. The Court further concludes that the lines of pro

gression at issue are essential to the proper operation of

the defendant, I.P.’s, business and that they are functional

and meet the needs of business necessity. The presently

constructed lines of progression, at the defendant’s Pine

Bluff mill, strike a reasonable balance between the de