Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education of Nashville and Davidson County, TN Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 2, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education of Nashville and Davidson County, TN Brief for Appellees, 1973. 1c5ebdce-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b582f983-193a-43c7-a7de-a1ede3f215ab/kelley-v-metropolitan-county-board-of-education-of-nashville-and-davidson-county-tn-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

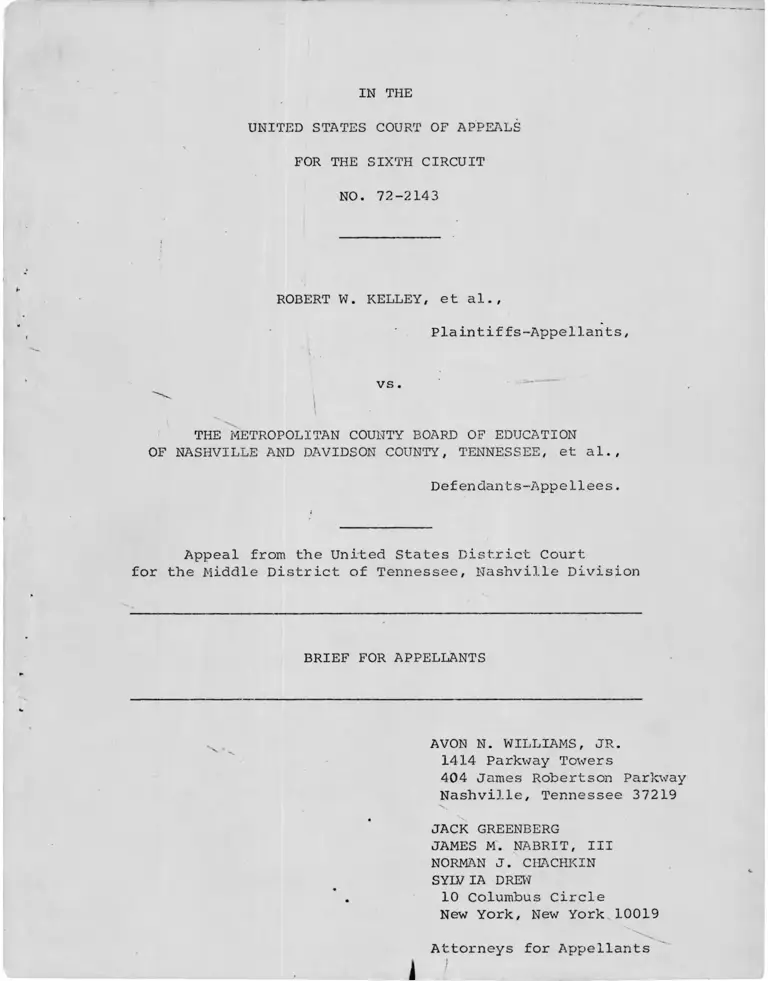

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO. 72-2143

ROBERT W. KELLEY, et al.,

Plaintif fs-Appellants,

vs.

1^ 1

THE METROPOLITAN COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION

OF NASHVILLE AND DAVIDSON COUNTY, TENNESSEE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Tennessee, Nashville Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

1414 Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

SYIV IA DREW

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

1

I N D E X

Page

Issue Presented for Review .......................... 1

Statement.................. ^ 7 i ................... 2

ARGUMENT ............................................ 7

Conclusion.......................................... 15

Appendix............................................ la

Table of Cases

Baskin v. Brown, 174 F.2d 391 (4th Cir. 1949) ......... 10

Berger v. United States, 255 U.S. 22 (1921) ........... 9

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 324 F. Supp.

439 (E.D. Va. 1971) 8-9, 11

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) 12

Harvest v. Board of Public Instruction of Manatee

County, Civ. No. 65-12-T (M.D. Fla., April 11,

1970) 12

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ., 463

F.2d 732 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 41 U.S.L.W.

3254 (November 6, 1972) 2

Knapp v. Kinsey, 232 F.2d 458 (6th Cir. 1956) ......... 9

Laird v. Tatum, No. 71-288, 41 U.S.L.W. 3208

(October 10, 1972) 11

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 466 F.2d

890 (6th Cir. 1972) 12

Oliver v. Kalamazoo Bd. of Educ., 448 F.2d 635

(6th Cir. 1971) .................................. 12

Oliver v. Kalamazoo Bd. of Educ., Civ. No. K-88-71

(W.D. Mich., August 9, 1972) 12

Table of Cases (continued)

Palmer v. United States, 249 F.2d 8 (10th Cir. 1957)

Plaquemines Parish School Bd. v. United States,

415 F.2d 816 (5th Cir. 1969) ......

Paqe

. . 9

Rosen v. Sugarman, 357 F.2d 794 (2d Cir. 1966)

SEC v. Bartlett, 422 F.2d 475 (8th Cir. 1970) ..

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402

U.S. 1 (1971) ............

Tucker v. Kerner, 186 F.2d 79 (7th Cir. 1949)

Tynan v. United States, 376 F.2d 761 (D.C. Cir. 1967) • . 9

United States v. Amick, 439 F.2d 351 (7th Cir. 1971)

United States v. Grinnell Corp., 384 U.S. 563 (1966) .

United States v. Hoffa, 382 F.2d 856 (6th Cir. 1967)

. . 9

• • 9

•• 8, 11

Wolfson v. Palmieri, 396 F.2d 121 (2d Cir. 1968)

ii

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO. 72-2143

ROBERT W. KELLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

THE METROPOLITAN COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION

OF NASHVILLE AND DAVIDSON COUNTY, TENNESSEE, et al.,

j Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Tennessee, Nashville Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Issue Presented for Review

Did the District Judge err when he recused himself

upon the filing, hy one of the defendants in this school

desegregation action, of a motion under 28 U.S.C. §144 —

despite the Judge's clearly correct determination that the

motion and affidavit were legally insufficient, that the

motion was filed as a subterfuge to remove the Judge because

of disagreement with his rulings, and without any indication

that personal embarrassment or other cause existed for a

recusal sua sponte?

Statement

The long history of this school desegregation case

involving the public schools of Nashville, Tennessee, is set

out in this Court's most recent opinion, Kelley v. Metropolitan

County Bd. of Educ., 463 F.2d 732 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 41

U.S.L.W. 3254 (November 6, 1972). In that decision, this Court

said:

The District Court order in this case

specifically retained jurisdiction.

Thus, upon our affirmance, the door of

the District Court is clearly open (as

it has been!) to the parties to present

any unanticipated problems (not

resulting from failure to comply with

its order) which may have arisen or

may arise in the future.

(463 F.2d at 747). Accordingly, on July 17, 1972, the

Metropolitan County Board of Education filed a Petition in the

1/

district court (A. 1-6) alleging, in substance, that serious

practical problems had developed in the administration of the

desegregation order entered by the Court which in the board's

view justified certain modifications to the order. In

particular, the board proposed changes in the plan in order to

1/ Citations are to the Appendix herein.

-2-

free twenty-nine busses which would be

used to transport students attending

other schools . . . [and which would thus]

allow all schools to open no later than

9:30 a.m. and to close no later than 4:00

p .m.

(A. 3)[emphasis added]. To achieve this result, the board was

proposing changes in the junior high school desegregation plan

pursuant to which "Washington and Wharton schools would become

virtually all black walk-in schools and Hillwood Junior High

would become virtually all white" (A. 2).

A hearing on the board's petition was held August 16,

1972. Testimony of the Superintendent and two assistants

indicated that the changes were being proposed only to attempt

to alleviate the problem of school days for elementary children

at twelve facilities ending after 4:00 p.m. (A. 30-31, 58);

that the system considered the resegregation of the junior high

schools to be undesirable (A. 36, 240) and required only because

sufficient transportation facilities did not exist (A. 55-56,

212-13). In turn, the evidence revealed that the school system

had sought funds from the Metropolitan Government and City

Council to purchase additional equipment, but that requests

were denied (A. 16, 60-62) with the clear message from individ

ual Council members that funds for additional buses in order

2/ The Petition also sought to make minor boundary adjustments

for elementary schools, which were unopposed, and which the

district court permitted (See A. 44-54).

-3-

to implement the desegregation plan would not be voted (A. 65).

The Superintendent, on cross-examination, also acknowledged

that the Mayor had expressed opposition to the desegregation

plan because it involved busing (A. 66).

At the conclusion of the hearing, the District

Court ruled from the bench (A. 246-47) that the elementary

school boundary line modifications (see n.2 supra) would be

permitted but the proposed resegregation of junior high schools

would not be allowed. In light of the school board's expressed

concern for the safety of pupils dismissed from classes

after 4:00 p.m., the Court directed the school authorities

to immediately place a purchase order for a sufficient number

of buses to end such scheduling and to make suitable arrange

ments for the rental or other temporary use of such vehicles

until delivery of the new ones. Finally, reflecting the evidence

concerning the role of the City Council members in preventing

an earlier solution of the safety problem by the school

authorities, the court took the occasion to grant a year-old

motion which had been made by plaintiffs seeking the addition

3 /

of the Mayor and Council members as parties defendant, and

they were temporarily restrained pending a hearing a week

thereafter from interfering with execution of the Court's

Orders or putting pressure upon the school board in that regard.

17

See Supplemental Appendix in Nos. 71-1778 & -1779, pp.

78-81 (attached hereto as Appendix A).

-4-

The following day, a written Order, somewhat more precise in

its injunctive provisions, was entered superseding the oral

bench order (A. 249-51) and on August 18 a Memorandum supportive

of the Order was filed (A. 252-63).

Thereafter, on August 22, 1972, the Mayor of Nashville

(C. Beverly Briley) filed a motion pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 144

demanding that the District Court recuse itself. The affidavit

supporting the motion set out numerous excerpts from the

transcript of the August 16, 1972 proceedings which the Mayor

claimed indicated a personal bias on the part of Judge Morton

against him (although the Mayor is nowhere mentioned in the

Court's remarks) and contained quotations from the Court's

rulings (A. 264-84):

The same day, without any response to the motion

having been filed by any of the other parties, the Court issued

an Order finding the motion and affidavit completely legally

insufficient under the statute (A. 285). However, even while

recognizing that the motion was a "subterfuge," the District

Judge determined to recuse himself. Plaintiffs thereupon

filed a Motion to Vacate the Order of Recusal (A. 286-88)

which was denied after a hearing in a Memorandum (A. 292-96)

which concluded as follows:

The Court, upon considering the motion to

recuse and the affidavit, considers the same

to be without merit. The action of the Court

stands, however, on a different basis.

Integrity of the judicial process requires not

only fairness and impartiality, but also the

-5-

appearance of fairness and impartiality. The

motion to recuse is a device to accomplish this

purpose. it is sparingly used by counsel for

the reason that it is usually instantly granted.

It is, however, also available as a subterfuge

ploy and to the Court's surprise, it appears to

be so utilized by counsel in this case. Such

utilization does not, however, change the basis

for the Court's decision.

The quality of justice cannot be dependent upon

the identity of a particular individual who sits

on a particular Court at a particular time. A

general uniformity of justice is effected by the

nature and structure of our judicial system. It

is the process, not the particular person, which

determines the justice applied in our society.

It is the Court's observation that everything

that has occurred to date in this case is the

natural, necessary, inevitable, and fully

predictable consequence of the School Board's

" '^hard-line policy — however induced or influenced.

It is likewise this Court's opinion that

changing the judge won't change anything else

unless the Board seizes the opportunity to modify

its attitudes. Perhaps changing Judges can

operate as it sometimes appears when baseball

clubs change managers -- maybe emotions can be

calmed so intelligence can have an opportunity.

The motion to reconsider is denied.

(A. 295-96) (emphasis added). Subsequently, a hearing was

conducted before the Hon. Frank Gray, Chief Judge of the District

Court, who sustained the propriety of the temporary restraining

order against the Mayor and City Council while vacating it since

bus orders had been placed, the purpose of the order had been

accomplished, and the Court believed "that all defendants in

the case will now proceed, in good faith, to assist in the

implementation of the orders heretofore entered in this action

..." (A. 297-300, at 300). x N

-6-

September 14, 1972, certain members of the City Council

filed a Notice of Appeal from the August 17 Order of Judge

Morton requiring the acquisition of additional buses to alleviate

safety problems (that appeal has since been dismissed) and on

September 15, 1972 plaintiffs appealed the Order of Recusal.

ARGUMENT

This appeal brings before this Court a very serious

problem of federal judicial administration: the substantial

pressures placed upon federal district judges by local or

national politicians in an effort to influence the course of

decision. Not only is the problem arising with greater frequency

than ever in school desegregation actions, but one may hardly

imagine a class of cases in which the character of the judicial

response is as important to the maintenance of strong and inde

pendent federal courts. Additionally, just as vigorous and sus

tained leadership on the part of local school boards plays an

immensely important role in the success of desegregation

efforts, so too may the firm and courageous stand of a federal

district judge in support of his oath of office engender the

respect for the law so essential to the survival of our system.

The situation presented to the District Court in

this case called for— if anything— disciplinary action against

counsel, rather than stepping down from the case. Beyond any

peradventure, the motion and affidavit were so devoid of any

possible merit as to be frivolous, scandalous and designed only

-7-

to diminish public respect for the office of the Court.

The briefest discussion of the law concerning § 144

motions will serve to demonstrate the technical and substantive

sufficiency of that made in this case. In the first place,

counsel were apparently unwilling or unable to accompany the

motion with a certificate of good faith, United States v.

Hoffa, 382 F.2d 856, 860 (6th Cir. 1966); and see, cases cited

by plaintiffs in opposition to motion to recuse (A. 289-90).

Furthermore, the extensive quotations from the August 16

transcript contained in the Mayor's affidavit are hardly suffi

cient to suggest a personal bias. They are in most instances

"taken somewhat out of context [and a]fter reconstruction of

the incidents ... do not ... rise to the level of exhibiting a

bent of mind impeding impartiality of judgment," Wolfson v.

Palmieri, 396 F.2d 121, 125 (2d Cir. 1968). Indeed, the Mayor—

who executed the affidavit— was never mentioned by the District

Court during the hearing.

The affidavit attempts to connect the District Court's

"objectionable comments" with some kind of bias by referring

to the Court's expression of legal opinion contained in the

Memorandum accompanying the temporary restraining order (A. 275) .

Prejudgment as to the law, of course, is

manifestly insufficient by reason of the

fact that every judge presumably knows

his legal premises before the evidence

comes in, and if he is in error the remedy

is by appeal. Indeed, even if a judge

thinks a party's legal position is weak

or in error, this would not in any way impede a judge's ability to conduct a

fair trial.

-8-

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 324 F. Supp. 439, 445 (E.D.

Va. 1971). Accord, Tucker v. Kerner, 186 F.2d 79, 84 (7th

Cir. 1950). The general rule is that the fact of adverse

rulings during the proceedings will not support a § 144 motion

to recuse. Knapp v. Kinsey, 232 F.2d 458, 466 (6th Cir. 1956);

Palmer v. United States, 249 F.2d 8, 9 (10th Cir. 1957); Tynan

v. United States, 376 F.2d 761, 765 (D.C. Cir. 1967); United

States v. Amick, 439 F.2d 351, 369 (7th Cir. 1971).

There may have been some close questioning by the

Court at the August 16 hearing, designed to elucidate all of

the relevant evidence, but that is hardly indicative of the

Court's prejudice. As the Fifth Circuit has said of a some

what analogous situation: "A last ditch, last hour stand in

defense of the racial purity of the public schools of Plaquemines

Parish, could hardly be expected to pass into history without

producing some fireworks," Plaquemines Parish School Bd. v.

United States, 415 F.2d 817, 825 (5th Cir. 1969).

The relevant inquiry is whether the affidavit success

fully reveals a personal bias stemming from an extrajudicial

source, Berger v. United States, 255 U.S. 22 (1921); United

States v. Grinnell Corp., 384 U.S. 563 (1966). But, while the

affidavit correctly quotes instances in the August 16 hearing

in which the District Court attempted to ascertain the occur

rence or correctness of events which had been suggested by the

media prior to the hearing, in every relevant instance the

matters which formed the basis for the Court's August 17 ruling

-9-

were established by sworn testimony at the trial. "A record

which reflects an appropriate ground for a trial court's

observations refutes any claim of personal bias." SEC v.

Bartlett, 422 F.2d 475, 481 (8th Cir. 1970), and cases cited.

The Mayor was in essence complaining that the District

Court was biased and prejudiced because it enforced the

Fourteenth Amendment.

The facts set forth in this affidavit, however,

show no personal bias on the part of the judge

against any of the defendants, but, at most,

zeal for upholding the rights of Negroes under

the Constitution and indignation that attempt

should be made to deny them their rights. A

judge cannot be disqualified merely because he

believes in upholding the law, even though he

says so with vehemence. Personal bias against

a party must be shown.

Baskin v. Brown, 174 F.2d 391, 394 (4th Cir. 1949). While we

commend the District Court's actions and rulings of August 16-17,

we hardly think they are indicative of a bias against the Mayor

and City Council; the situation was brought to the attention

of the Court on October 21, 1971 when plaintiffs filed a motion

to join the Mayor and Council as parties (see n.3 supra) but

was ignored by the Court from that time until the evidence and

testimony of August 16 were received upon a subsequent school

board motion.

We come, then, to question the propriety of the

District Court's action in recusing itself upon the filing of

so inadequate a motion and affidavit. As Mr. Justice Rehnquist

has recently summarized,

-10-

The federal courts of appeals which have

considered the matter have unanimously

concluded that a federal judge has a duty

to sit where not disqualified which is

equally as strong as the duty to not sit

where disqualified. Edwards v. United States,

334 F.2d 360, 362 (CA 5 1964); Tynan v.

United States, 376 F.2d 761 (CADC 1967); In

re Union Leader Corporation, 292 F.2d 381

(CA 1 1961); Wolfson v. Palmieri, 396 F.2d

121 (CA 2 1968); Simmons v. United States,

302 F.2d 71 (CA 3 1962); United States v.

Hoffa, 382 F.2d 856 (CA 6 1967); Tucker v.

Kerner, 186 F.2d 79 (CA 7 1950); Walker v.

Bishop, 408 F.2d 1378 (CA 8 1969).

Laird v. Tatum, No. 71-288, 41 U.S.L.W. 3208, 3210 (October 10,

1972). See also, Rosen v. Sugarman, 357 F.2d 794 (2d Cir. 1966);

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, supra, 324 F. Supp. at 449.

And while a district judge is always free to withdraw from a

case irrespective of the insufficiency of the motion and affidavit,

see United States v. Hoffa, supra, 382 F.2d at 861; Wolfson v.

Palmieri, supra, 396 F.2d at 125, "there are strong counter

vailing considerations which must affect a judge's decision:"

A judge has a duty to decide whatever cases

come before him to the best of his ability.

28 U.S.C. § 453. There is an obligation not

to disqualify one's self, therefore, solely

by reason of the personal burdens related

to the task. The duty is the more compelling

when a single judge has acquired by experience

familiarity with a protracted, complex case,

which could not easily be passed on to a second judge ....

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, supra, 324 F.2d at 448-49.

Two especial considerations in school desegregation

cases enlarge the significance of this principle. First, the

litigation is extraordinarily complex (particularly when its

subject matter is a school system of the size involved herein)

-11-

and calls for the exercise of an enlightened federal equitable

jurisdiction, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402

U.S. 1 (1971), which must be informed by a thorough knowledge.

Second, such cases assume extraordinary significance in the

political arena and are readily perceived as appropriate vehicles

for publicized attempts to influence the course of decision

through pressure. E,g., Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958);

Harvest v. Board of Public Instruction of Manatee County, Civ.

No. 65-12 T. (M.D. Fla., April 11, 1970).

The very magnitude and continuing nature of the problem,

we believe, compels an exercise of this Court's supervisory

power in this instance. The practice of political figures'

| | .attempts to extort :specified results from federal district

judges is not a relic of an antiquarian age, fifteen or even

five years ago. It is a repeatedly recurring problem in the

district courts of this Circuit. A motion to recuse followed

a favorable district court ruling in the Kalamazoo case, Oliver

v. Kalamazoo Bd. of Educ., 448 F.2d 635 (6th Cir. 1971), for

example. See Oliver v. Kalamazoo Bd. of Educ., Civ. No. K-88-71

(W.D. Mich., August 9, 1972).

District judges tend almost unavoidably to respond to

these pressures. In the Memphis case, Northcross v. Board of

Educ. of Memphis, 466 F.2d 890 (6th Cir. 1972), for example,

the district court initiated recusal proceedings by a letter to

counsel in which the Court stated that his son was attending

the Memphis public schools and the Court desired to be informed

-12-

whether either party desires that the Court recuse itself.

Frankly, the plaintiffs viewed this letter as some indication

that the Court was aware of community pressures, and responded

as follows:

After full consideration of the matter

our clients have instructed us to submit

this request that the Court recuse himself

in this case. Because of the community

tension, the campaign last year and this

year of public hostility led by public

officials and the resulting abuse and harass

ment of the Court and counsel, plaintiffs

request that in accordance with the guidelines

for nondisclosure that you communicate our

motion that the Court, pursuant to 28 USC 292 (b) request that the Chief Judge of the

Circuit, in the public interest, designate a

Judge not resident in this district to hear

this case.

The District Court did not recuse itself but transmitted the

response to the chief Judge, who entered an order July 12, 1971

denying the request, stating that no grounds for disqualification

existed.

The point of this recital is not that there should

have been a change of judges in the Memphis case, but that the

problem of judicial response to community pressures in school

desegregation cases merits the attention of this Court.

Appellants here have absolutely no preference as

between Hon. L.Clure Morton and Hon. Frank Gray, the United

States District Judges for the Middle District of Tennessee.

Indeed, Judge Gray's Order (A. 297-300) subsequent to the recusal

of Judge Morton verifies the latter's observation (A. 296) that

-13-

"changing the Judge won't change anything else." However, it

is also undeniable that Judge Gray, already burdened with a

full docket and with additional administrative responsibilities

as Chief Judge of the District Court, will require substantial

additional time to become familiar with the details and intri

cacies of the metropolitan Nashville school system so as to be

in a position to deal with any future request for modification

of the plan, etc. Nor is the goal of a strong and independent

federal judiciary able to effectuate federal Constitutional

guarantees served if parties who disagree with rulings on issues

of public importance can secure the withdrawal of a judge by

the filing of a frivolous motion and affidavit.

Nothing in the comments or Orders of the original

District Judge in this case indicates that personal embarrass

ment, etc., played a part in the decision to recuse. Rather,

the Court states what seems to us a very infelicitous metaphor:

Perhaps changing Judges can operate

as it sometimes appears when baseball

clubs change managers — maybe emotions

can be calmed so intelligence can have

an opportunity.

(A. 296). It seems apparent from this remark that the District

Judge was strongly influenced to recuse himself by the mere

filing of a motion by Mayor Briley, however insubstantial and

insufficient. If that is indeed the case, we think it evident

that Judge Morton should have continued with the matter.

Appellants cannot in good conscience request this

Court to direct Judge Morton to resume jurisdiction in the cause.

-14-

However, it would seem appropriate, in light of the circumstances

and precedent set out above, for the matter to be remanded with

instructions that Judge Morton reconsider his recusal, and

with guidance from this Court to the effect that no obligation

whatsoever toward recusal should be considered to have been

created by the filing of the frivolous motion and affidavit

submitted by Mayor Briley.

CONCLUSION

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons, appellants

respectfully pray that this matter be remanded to the District

Court for reconsideration of the Order of Recusal entered by

Hon. L. Clure Morton in accordance with such suggestions and

guidance as the Court elucidates in its opinion.

Respectfully submitted,

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

1414 Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

SYLVIA DREW

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

-15-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 2nd day of January,

1973, I served two copies of the Brief for Appellants Kelley,

et al. in the above-captioned matter upon the following counsel

for the parties herein by depositing same in the United States

mail, first-class postage prepaid, addressed to each of them as

follows:

James H. Harris, Esq.

Metropolitan Court House

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

Seymour Samuels, Jr., Esq.

Third National Bank Bldg.

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

Larry Snedeker, Esq.

Metropolitan Court House

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

Gilbert S. Merritt, Esq.

Life & Casualty Tower

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

Harland Dodson, Jr., Esq.

900 Nashville Bank & Trust Bldg

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

James F. Neal, Esq.

Third National Bank Bldg.

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

Ogden Stokes, Esq.

1507 Parkway Towers

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

Hon. Charles H. Anderson

United States Attorney

Nashville, Tennessee 37203

Attorney^for Appellants

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT '

NOS. 71-1778 and 71-1779

ROBERT W. KELLEY, et al.,

HENRY C. MAXWELL, JR., et al.,

Piainti ffs-Appellees-Cross

Appellants,

vs . _ ----

METROPOLITAN COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION OF

NASHVILLE and DAVIDSON COUNTY, TENNESSEE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants-Cross

Appellees.

SUPPLEMENTAL APPENDIX

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.Suite 1414, Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

SYLVIA DREW10 Columbus CircleNew York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appellees-Cross Appellants

* (+7T * 6 *o®S imqpqod

-oaqej-;) uopqBOtip© .to pjioq ©qq to qpjouoq pm osn etp joj cpooqog

OTTQTVT utqppodoaqoji eqq jo /qaedojd oqq j o ppx oq epqpq sppotp

‘quoMwoaoo in qTpodonqej.; ‘qmpitojop /qjrd poEodond oqx (g)

•Eopqjid /p;o.ipt oscrqq Shock popjocox oq qouirro popp0.i oqopd

-tcoo sapq,xvd eseqq ro oouosqu oqqup qi/qq ®3oppi sjjpqtzpxpg (p) v-

:qjmoo opqq Moqo ppnoM ptm 'euSpcGi pin. sjoe

-sooons jpoqq ‘pepjppi.Tit iieqn ‘p m qtrotuujOAoo m'Oppodojq op; pp e TO

Xpouuoo /qimoQ 1r.qppodo.130j.; oqq jo saeqrcetc 9i? sopqtOTdto pr-pop j.po

•xpoqq irp pm? /pptnppApptrp '/oqoos ppaxq ptn> ‘pjojaeqqrq- tmppppft *P

'qqvaSOK cox '©u/xdeepo aosrpg '/opzxog ttqop *rop9n> eaepms. •£

**JS 'oqqojjstg ‘q s o S o y 'jponj. *p so cup * m 'nospp// /pm j, ‘Strpp

-jeqpes oopjvno ‘PPPH sop.re;i© ‘couop *o opzpH ' ’Jp ‘secpofi eSjoop

‘qqepjpEqs *o pjv£ 'ill 'oxpSnoa ppopjurreK * *.ip • 'uoqpping *v satnsp

•dm~qs oiccrqx ‘BtrpSSpH *3 •« '.lopppK nqannoa 'Xn/ioq pojj ‘uonjfovp

•q /oupno ‘xopprjp *g spjjcj.; ‘s-crpjptiiH *3 eocrcp ‘jetrosrop •q qjoqop

*m;pj:op stop ‘uoue.13 'o eop.nriio ‘/T;pp.ixpG *d Jfovp ‘jmco *q rrqop

‘qntxtmEc: ©ITTaho ‘jecmj uqop ‘Ejjoojg *3 trcrarrapx 'qq ©300.10 M, ©op

‘dpt{ffU9jjm.'ic '0 pm-d ‘epqpsnSoa *q ppojiH 'uospp/; ’V trqop ' *ap

'oompog *\ qsojjO£ ‘/-DKqog *k uoqp,iT?o ‘stu-ipv *p pjnpopp ‘uqpug /o0

*eouop /ohx 'so^rp cpppg 'qirotiwroAOD m.'qppodo.iqGK ppts jo jo/ipc

/qimoo m. qpxodoHqep; be p m /pptnppApptrr ‘/opT-^ /p.TOAOp ‘( 'bea qo

PO’P ’©eg ‘aeqavqo ireqxpodoaqep;) uopqt xrod̂ po oppqnd n ‘eossetiuex

‘/qxmoo uosppAtp 'opppAqevfl jo qneEaaoAop mqppodoaiop; eqq ©smo

spqq trp qmpnojep sopajid oi Strpirpof ©jnpooojg ppApo .to Boprq.

pnjep©3 oqq ,to pg p m (i)6T sopny oq qumBand aopjo ur jsoue qmioo

Bpqq qvtpq gaoc ‘posimoo p©uSpBaspMm jpoqq /q 'sj.rpr;upr-pg

s a i x n d t ,j:q iij c g \ ao vzc.iu.oc ko,-t s i .n iK iT a j z p koijok

( *it qo'rrsŝ HKirj ‘ziet.oo bosoiavc ( ok> stuauct to 1:01 .v. one?: do Guvo0 /iKnoo KYxi'iodcvjry

9562 *4I602 'soil Biiopqov. ppApo *CA

•pr qo '"UP ‘ITF/XU. *0 /VNHH

( ’ IT TO 'AJTTEX XUIfTOK

EOISIAIG ETUAKS’.K

TuTESHKKTJ.Ii 10 XDIHISIC HHCCIK Oil VO/

SHiVIS CHIIiUl HHX dO xvnoo i o i e i s i g h h i ki

-Bqdura qnq „ .£ jcq 07a ©q ttp q p u ,, jtto up\ © ouoppjuoo p c sa o jd x o ,,

S?upA>q ev zlGX q«u2nv ( z tto jo tn reg ©pppAqatj; ©qq tip p o q o n l r c n

©II ‘ a o p jo p p t s to J ttq s t jo t q jnoo © tfojdos oqq 05 t u i sp to d d v

j o q jn o o ooqvqs poqpqQ oqq °q tropqnoppddr spq Puppuod j o p j o p p t s

j o u o p q tq ua tw pdup ©qq /tp © p oq uopqtonp© j o p j t o q q u rp u e jo p eqq

p©qsenfc©J p u t j e p j o ©qq pT©ddr oq postm oo pupoods Bl s je q q o p m

e jp n ts t j 'u ep s trcq *p 3pop(j -CopduD oq austcnjOAOo m qppodo jqe j.; eqq

p e s n to on ‘ Bpooqos j o u o p q tjS o q trp ©qq qq3no» qp so j t j o o u p jo p jo o

pp«8 prp poApoATtp u o p q tq jo d s tre jq pooqoo ©qq sioopq oq jo /to d o p q t

-p p ?A t sp q j o i p tj j o oim ®qq p eS p sp d ptre < j»pao p p t s 10 p to p q p jo

squo tco q tq s oppqnd ©ptm JJoppjfi j o i tp i ‘q jn o o eptfq j o j e p j o

U O p q tS o jS sssp ©qq 2u p ;to p p o j *,ropx®q p u r u o p q ts u o ju p uo ( 9 )

(*+10*? Ptre CO*? *T0 *? *«o®C

j o q j t q o u tq p p o d o jq o y ) *q«tfpnq ptre a u o p q a p jd o jd d t trp s t» q p jo

oq©A ©qq Suppnpctrp ‘ ppotmoo /q u n o o m q p p o d o jq ©}; eqq / q poqdopr

U opqtpepSop OAOjddrepp j o ©AOjddr. oq p s x p jo q q n r sp oq ‘uopqpppe

trp •qtrcKEjOAOo m qppodojq© }; ©qq j o qoSpnq ptm m n ©qq sq p tq n a

p u t e o j t d e j d pm- *j©opj j o p ip o tn ro p j ptre qtteSr- p to c p j jo p q o oqq sp

'c o p q to r p a j o p j i o e Xqtmoo m qppodo jq*} ; ©qq Jtappnpoup ‘ s p j to q

j o ajoqmata p p t qupoddv e®op p trs oq p o sp jc q q n n sp 'q u o u u j©a 00

m q p p o d o jq o K ®qq TO J e o p j j o © A pqtjqapupw pt p n t OApsnoe'jto ropuo

oqq op ‘ / e p p j£ ^pjOAOg ‘jo f tK Xqunoo treqppodojqop, cqj, ( ? )

* (90*C ‘ 20*2 ‘ 10*2 ‘ 0009

‘j o q j r q o m qppodojq© };) EoqsXc pooqoa eqq © q tjed o oq A rt s c o c a u cpunr

B o q tp jd o jd d B pm ; boo?ppq p p r BOAOjddt ppotmoo p p tg ‘ttopaTonpir 10

p j to q /q tm oo m qppodojq© }; q u v p u o jo p ©qq ^q pozpppqn eq or. squat.

-OAOJdnp p \q p d to j o j oqu©&«2u P j j f x tp o m ftrf j joqq o Supjp tt pm opuoq

StrpxioB Ptre StrpAOjddr ‘ soxpq SupiAop 70 /q u p oqq Bt.q quet-ujOAop

treq p p o d o jq ©}; P P 'S j o ppotmoo /q tm oo m q p io d o jq o > ; o q j ( !j)

•osn-o aqq up

OApqot aXouJoqqt, j o joqtOTt «qq oq pp* /pp jt;B S o o o u ojotojot;?, qou

ppuon quotcujeAoo treqppodojqa^; p p ta j o ppotmoo ilqtmoo tr.qppodojqap .

eqq pm- quswpj»/»oo m qppodojq® }: oqq j o uopqpppt- ©qq ‘quouujeAOO

m qppodojq© }; p p t s j o j o / t>; ‘ /© pp jp ipjaAOpr / q pe/opdu© uoeq

©Auq oq p p v s oXotuioqqt jo q q o p m uopotrep *p ijopc -^q pm y irp o td to

p tp o p j jo cqp up StrpqOT- quewuoAOO m qppodojq«K ©qq j o £ e tuoqqv

m q p p o d o jq o q ©qq j o © o p jjo ©qq j£q © auto «pqq up p o c u e e o jd o j

I

sp uopqtonpg jo pj-»oq /qunoo mqpiodojq©}, qmpuojop ooupg (C)

*l£6T ‘jeqoqoo jo -Sup

^ GT2 Gqq spqq ‘VSKW *ioj ilGxuoqqB 'gosbguuoj, ‘GUXAqs'Eii ‘2 x rp p iitig

jpi-eg XBUOJ^BH p j f t t j ‘ G ajnbsg; ‘ p i g j j j b m SGXJBqo P«® ‘ s jo u g a jg ^ux

joj UexuoqqB GGOSGUtiGx ,gxxTâ b'°N ‘jcottox X^x^nSBO 5? 0JTT ‘oj^nbe^

‘ qqjouoj-r q j G q u o ‘ BqxrepxiGjoa JO j s.£eii.ioqqie ‘ XOZLZ e9esoxrxiGj)v

‘ ®TTJAP BPM ‘ Gsnoqq.iTi.oo /qxm oo txospxA'GQ '/G xw oqqv ^B^TXodo«iqGjj

‘I I I ‘q q j J J I J O '3 s o x jx q o '6 1 Zii GGSBGtxuGj ‘GXTfAP s13N 'STi-ptqng

q stu ii uBOjjQWv ‘ GJ-fnbsft 'T iopstreq *q q o q a oq p o x i^ w sum s u o jq o G fq o

S xqoS G ao j Gqq j o .£doo uoqoreo qxqq bgjjx^joo p o u S iG ao p u n o q j

sjJTXvrpnXtl <ioj s/etijoqqv

6X00T qJOX ̂ ©M '3JOX mgh

OCOZ ©qpns ‘©JOJID Btiqwnxoo 01

KMC VIATZS

MI3H0VHD *f fiVKHOMii i ‘iifflYH *h sawvr

caagNaaHO aovr

6xZLZ oosoetiuGx ‘0XXTAMBBN

• jg jx o J XBJ0UG3 pGqtreaS eq sjj-pqxrfxxd eqq (£ )

•SGxqxxiOBj

uoqq'Bq.iodGxre.iq Xjtggbgoou jo GOTreneqiiXBia pxre xioxqjsxnbOG qdu-ojd oqq

Aq spxm j j o GtXnqjptiQdxG oqq jo xroxqBZf.ioqqnB pun uojqB xadoaddB

eqq guxpnxotij qcmoo sxqq j o SGoaoep pxre s jo p a o uoxq-sSGjSosGp

p j-cs t p w X qjto io juoo xix qxtGKMJGAOO xreqqiodo.iq9j.i PT^’S jo sxooqos

oqxqnd ©qq © qtaedo oq q u o jo j j jn B pxre Ajbsggogxi squom ogurj j b

Xxxoxreuxj tioqqo H ts pxre suoxqBX.ido.iddB j o Sujaxw ©qq Bonssp

puoq jo:'x?A O jddB pxre SxrpSinJj.iT! Gqq ‘o p u n j xsq oxxqnd j o o sn

puis Sxij^agx oqq Sxrppnxoxrp 'poquomopdiiTj •£l©Ai q o®JJ© e<*

PXBX̂ B xsiqsiJs xooqos xroqxTodo.iq9pi ©qq jo TioxqBSG.iSGSGp G A jqoo jjt)

SxiXJjnbGJ: q jn o o s jq q ,£q pGaoqxio QJOjoqe.xGq B^opao GAjqoxmfux Gqq

qtjqq pxre eqq oq xreqxiodo.iqGK pp cs j o skbx pxro jGqaBqo ©qq JGpxm

pGSBGBBod g*ig .foqq q o jq rt j o sjow od j i b P^b q q i^ q q jo j e s jo a o x o

oq poocopjo oq sqxropxtojGp poxtjof ^ x^ gti PT^o J ° TT° (2 )

• exiSjc g b pxre s jo s o o o o n s J jo q q ‘pGUUBTib TiGqw ‘pxre qxiemuJGAOO

xreqxxodojqGH PT^g jo XTotmo0 ^qtmoo TreqxxodojqGj.; Gqq j o saoqiteiu

sb AqjGBdBO x^T °T JJo JTO^q POT JCXT^opxAXptix ‘ j^oqoos PTAiaa

aivoi.ic iffito

SiXGHOJ XBmtJ-Bd t j r t l l•HP ‘SKVICTI/̂ lLJIim