Terrell Jr. v. International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Terrell Jr. v. International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, 1981. 6dc453e6-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b5958ae9-2224-4fdb-8437-bb06fd34c046/terrell-jr-v-international-association-of-machinists-and-aerospace-workers. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

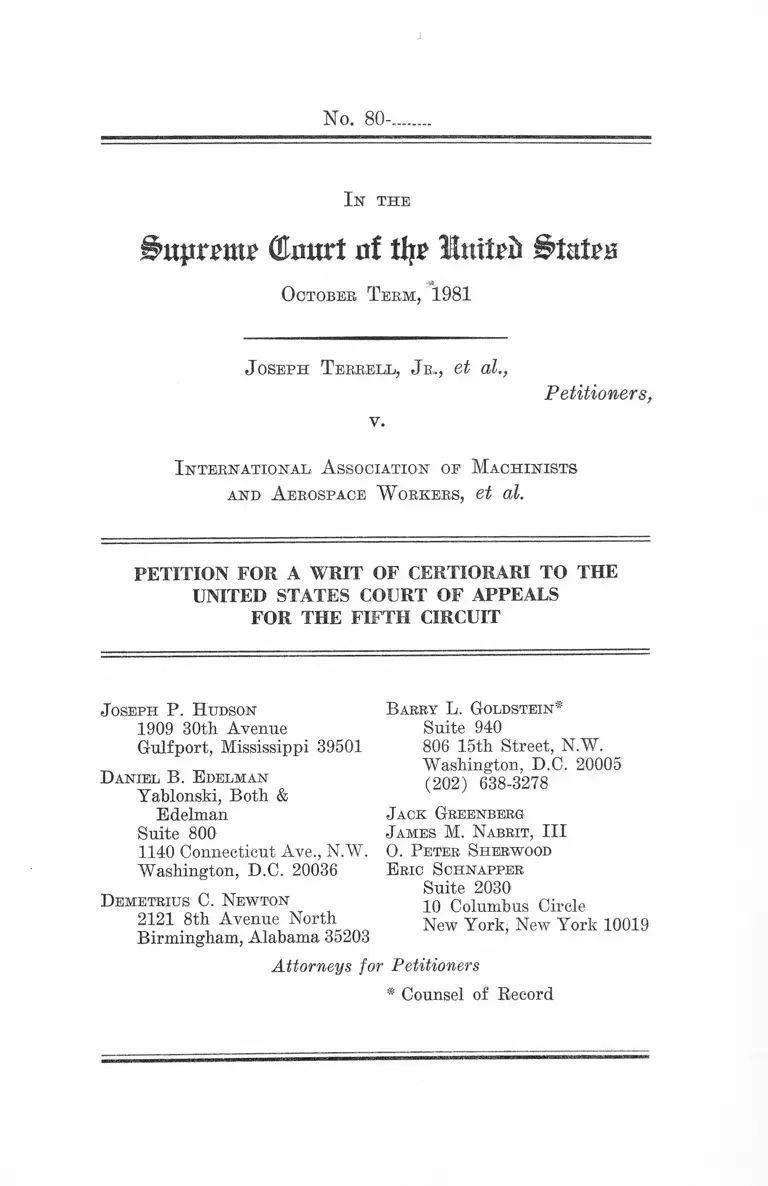

No. 80-.

I n the

(tart of tfyr luitrtt Btuim

-vS.

October T erm , 1981

Joseph Terrell, Jr., et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

I nternational A ssociation oe Machinists

and A erospace W orkers, et al.

PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Joseph P. Hudson

1909 30th Avenue

Gulfport, Mississippi 39501

Daniel B. Edelman

Tablonski, Both &

Edelman

Suite 800

1140 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

Demetrius C. Newton

2121 8th Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Barry L. Goldstein*

Suite 940

806 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 638-3278

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

O. Peter Sherwood

Eric Schnapper

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioners

* Counsel of Record

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Which of the 9 conflicting and over

lapping standards announced by 7

different circuits should be applied

to determine how and when a defendant

must be "named" in a charge filed with

the EEOC in order to be subject to

suit under Title VII of the 1964

Civil Rights Act?

2. Did the court of appeals err in

holding that petitioners failed

adequately to name any international

unions in their pro se charges filed

with the EEOC where the charges in

fact named the alleged union discrimi

nators as follows:

a. "International Molders & Allied

Workers, Local 342";

l

b. "International Association of Ma

chinists & Aerospace Workers,

Lodge 3 59";

c. "Brotherhood of Boilermakers,

Blacksmiths, Forgers, Helpers,

Local 583"; and

d. "Patternmakers Association of

Birmingham, affiliated with the

Patternmakers League of North

America A.F.L."

- 1 1 -

Parties Below

The following includes all of the

parties to the proceeding below:

1. International Association of

Machinists and Aerospace Workers

and its Lodge 359.

2. Brotherhood of Boilermakers,

Blacksmiths, Forgers and Helpers

and its Local 583.

3. International Molders and Allied

Workers Union and its Local

342.

4. Patternmakers League of North

America and the Patternmakers

Association of Birmingham.

5. United Steelworkers of America

Local 2140.

- iii -

and its

7. United States Pipe and Foundry

Company, a subsidiary of Jim

Walter Resources, Inc.

8. Local 136, International Brother

hood of Electrical Workers.

9. Joseph Terrell, Walter Dudley,

Thomas Green, Johnny Long,

Albert Mason, Marcus Oakes, Sam

Walker, and the class of black

workers at U.S. Pipe plant whom

they represent.

10. Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission, Amicus Curiae.

IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Questions Presented ................ i

Parties Below ...................... iii

Table of Authorities ............... vi

Opinions Below ..................... 1

Jurisdiction .................. 2

Statutory Provisions Involved ...... 2

Statement of the Case .............. 3

Reasons for Granting the Writ ....... 17

Conclusion ......................... 47

Attachment A, EEOC Charges Filed

in 1969 ..................

APPENDIX

Order of Court of Appeals

Denying Rehearing, August

7, 1981 ....................... 1a

Opinion of Court of Appeals,

May 14, 1981 .................. 3a

Judgment of District Court,

January 1 4 , 1 980 .............. 54a

v

Page

Rule 54(b) Certification of

District Court, January 14,

1980 ........................ 56a

Opinion of District Court,

October 1 6 , 1 979 .............. 58a

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Page

Batis v. Great American Federal

Savings & Loan Ass'n,

452 F. Supp. 588 (W.D. Pa.

1 978) ......................... 32

Bernstein v. National Liberty In

ternational Corp., 407 F. Supp.

709 (E.D. Pa. 1 976) .......... 1 8,33

Braxton v. Virginia Folding Box

Co., 72 F.R.D. 124 (E.D. Va.

1976) 40

Butler v. Local No. 4, Laborers

International Union, 308

F. Supp. 528 (N.D. 111.

1 969 ) ......................... 19,37

Byron v. University of Florida, 403

F. Supp. 49 (N.D. Fla.

1 975) .................. . 1 9,36

Canavan v. Beneficial Finance

Corp., 553 F.2d 860 (3d

Cir. 1977) 18,25,36

Chastang v. Flynn & Emrich Co. ,

365 F. Supp. 957 (Md. 1973) ..19,33-34

Coley v. M & M Mars, Inc., 461

F. Supp. 1073 (M.D. Ga. 1978) .. 34

- vii -

Page

Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41

(1957) ........................ 43

Curran v. Portland Superintending

School Committee, 435 F. Supp.

1 063 (Me. 1 977) ........ 18,31,33,37

Davis v. Weidner, 596 F.2d 726 (7th

Cir. 1 979) .................... 1 8,26

Delaware State College v. Ricks,

449 U.S. 250 ( 1 980) ........... 22

EEOC v. Brotherhood of Painters,

384 F. Supp. 1264 (S.D.

1 974 ) ........................ 41

EEOC v. International Brotherhood of

Electrical Workers, 476 F. Supp.

341 (Mass. 1 979) .............. 34,40

EEOC v. McLean Trucking Co., 525

F.2d 1007 (6th Cir. 1975) ..... 30

Eggleston v. Plumbers' Local 130,

26 FEP Cases 1192 (7th Cir.

1 981) .................. 9,26,28,30

Eldredge v. Carpenters Joint

Apprenticeship Committee,

440 F. Supp. 506 (N.D. Cal.

1977 ) ........................ 1 9,34

Escamilla v. Mosher Steel Co.,

386 F. Supp. 101 (S.D.

Tex. 1 975) .................... 1 8

- viii -

Page

Evans v. Sheraton Park Hotels,

503 F.2d 177 (D.C. Cir.

1974) ......................... 29,30

Flesch v. Eastern Pennsylvania

Psychiatric Institute, 434

F. Supp. 963 (E.D. Pa.

1977) ......................... 19,36

Friedman v. Weiner, 515 F. Supp.

563 (Colo. 1981) ............ 18

Gibson v. Local 40, Supercargoes,

etc., Union, 543 F.2d 1259

(9th Cir. 1 976) 27,61

Glus v. G.C. Murphy, 629 F.2d

248 (3d 1989), vac. and rem.

on other grounds, 1 0 1

S.Ct. 201 3 (1 981) .... 28

Glus v. G.C. Murphy 562 F.2d 880

(3d Cir. 1 977) ............. 28-30,40

Goodman v. Bd. of Trustees of Com

munity College, 498 F. Supp.

1 329 (N.D. 111. 1 980) ......... 1 8,33

Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Corp.,

498 F.2d 641 (5th Cir. 1974) ... 36

Hanshaw v. Delaware Technical and

Community College, 405 F. Supp.

292 (Del. 1 975) ............... 1 9,31

Haines v. Kerner, 404 U.S. 519

(1 972) ........................ 44

IX

Page

Hardison v. TWA, 375 F. Supp, 877

(W.D. Mo. 1974), rev'd on

other grounds, 527 F.2d 22

(8th Cir. 1975), rev'd, 432

U.S. 63 (1977) ............... 34,40

Henry v. Texas Tech. University,

466 F. Supp. 141 (W.D.

Tex. 1 979) .................. 18,37

Hochstadt v. Worchester Foundation,

425 F. Supp. 318 (Mas. 1976) ... 19,35

Hughes v. Rowe, 449 U.S. 5

(1980) ........................ 44

International Brotherhood of Team

sters v. United States, 431

U.S. 324 (1977) ............... 7

I.U.E. v. Robbins & Myers Co.,

429 U.S. 229 (1976) ........... 22

Jackson v. University of Pittsburgh,

405 F. Supp. 607 (W.D. Pa.

1975 ) ......................... 19,35

Jacobs v. Board of Regents, 472 F.

Supp. 663 (S.D. Fla. 1979) .... 18,32

Jamison v. Olga Coal Co. , 335

F. Supp. 454 (S.D.W. Va.

1971 ) ......................... 35,39

Kaplan v. International Alliance

of Theatrical Workers,

525 F.2d 1354 (9th Cir.

1975) ......................... 24,40

x

Kelly v. Richland School Dist.

Page

No. 2, 463 F. Supp. 216

(S.C. 1 978) ............... 18,31,33

LeBeau v. Libby-Owens-Ford Co.,

484 F.2d 798 (7th Cir.

1973) .......................

Lewis v. Southeastern Pennsylvania

Transp. Authority, 440 F.

Supp. 887 (E.D. Pa. 1977) ___ . . 18,31

Love v. Pullman Co., 404 U.S.

522 (1972) ..................

McDonald v. America Federation of

Musicians, 308 F. Supp. 664

(N.D. 111. 1 970 ) ........... 1 9,33,37

Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems,

Inc., 478 F.2d 979 (D.C.

Cir. 1 973) ..................

Martin v. Easton Publishing Co.,

478 F. Supp. 796 (E.D. Pa.

1979) ....................... 19

Mohasco Corp. v. Silver, 447

U.S. 807 (1980) .............

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 271

F. Supp. 27 (E.D.N.C.

1967) .......................

Oscar Mayer & Co. v. Evans, 441

U.S. 750 (1979) .............

xi

Page

Plummer v. Chicago Journeyman

Plumbers, 452 F. Supp. 1127

(N.D. 111. 1978), rev'd on

other grounds sub. nom.,

Eggleston v. Plumbers' Local

No. 130, 26 FEP Cases 1192

(7th Cir. 1981) ............... 32

Puntolillo v. New Hampshire Racing

Commission, 390 F. Supp. 231

(N.H. 1 975) ..................,. 34,36

Ricks v. Delaware State College,

605 F.2d 710 (3rd Cir. 1979),

rev'd on other grounds,

449 U. S . 250 ( 1 980) .......... . 27

Roberts v. Western Airlines, 424

F. Supp. 416 (N.D. Cal.

1976) ........................ . 40

Romero v. Union Pacific R.R., 615

F.2d 1303 (10th Cir. 1980) ____. 28-29

Scott v. Univ. of Delaware, 385

F. Supp. 937 (Del. 1 974 ) ....... 19,33

Shehadeh v. Chesapeake & Potomac

Telephone Co., 595 F.2d

711 (D.C. Cir. 1 978) .......... 25

Schick v. Bronstein, 447 F. Supp.

333 (S.D.N.Y. 1 978) ............. 18,33

Skyers v. Port Authority of New

York and New Jersey, 431

F. Supp. 79 (S.D.N.Y. 1976) ..... 19,31

- xii -

Page

Stevenson v. International Paper Co.,432 F. Supp. 390 (W.D. La.

1 977) ..................... 32,37,41

Stith v. Manor Baking Co., 418

F. Supp. 150 (W.D. Mo.

1 976) ................... 1 8,31 ,33,37

Stringer v. Commonwealth of Penn-

slyvania Department of Com

munity Affairs, 446 F. Supp.

704 (M.D. Pa. 1 978) .......... 32

Taylor v. Armco Steel Corp., 373

F. Supp. 885 (S.D. Tex. 1973) .. 39

Thornton v. East Texas Motor

Freight, Inc., 497 F.2d 416

(6th Cir. 1 974) ............... 46

Torockio v. Chamberlin Mfg. Co.,

51 F.R.D. 517 (W.D. Pa. 1070) .. 40

United Air Lines v. Evans, 431

U.S. 553 ( 1 977) ............... 22

Vanguard Justice Society, Inc.

v. Hughes, 471 F. Supp. 670

(Md . 1 9 7 9) ................... 1 8,31

Van Hoomissen v. Xerox Corp., 368

F. Supp. 829 (N.D. Cal. 1973) .. 19

Vogel v. Torrence Bd. of Educ.,

447 F. Supp. 258 (C.D.

Cal. 1978)

- xiii -

18,35

Page

Wallace v. International Paper Co.,

426 F. Supp. 352 (W.D. La.

1 977 ) ........... .............. 35

Watson v. Gulf & Western Industries,

650 F.2d 990 (9th Cir. 1981) ... 19,24

Wells v. Hutchinson, 499 F. Supp.

174 (E.D. Tex. 1 980) .......... 1 8,33

Williams v. General Foods Corp.,

492 F.2d 399 (7th Cir. 1974) ... 26

Williams v. Massachusetts General

Hospital, 449 F. Supp. 55

(Mass. 1978) .................. 32

Women in City Government United

v. City of New York, 515

F. Supp. 295 (S.D.N.Y. 1981) ... 18

Statutes and Other Authorities

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 (as amended 1972),

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq. .... passim

28 U.S.C. § 1 254(1 ) ................ 2

xiv

Page

Annual Report of the Director of

Administrative Office of the

United States Courts

(Wash. 1981) 23

Equal Employment Opportunity Com-

mission, 12th and 13th Annual

Reports (1981) 45

EEOC Compliance Manual, § 2......... 45

Statistical Abstract of the United

states, 1 980 777777777777777... 38

XV

No. 81-

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1981

JOSEPH TERRELL, JR., et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF MACHINISTS

AND AEROSPACE WORKERS, et al.

Petition For A Writ of Certiorari To The

United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

The petitioners, Joseph Terrell, Jr.,

et al. , respect fully pray that a Writ of

Certiorari issue to review the judgment and

opinion of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit entered in

this proceeding on May 14, 1981.

2

OPINIONS BELOW

The May 14, 1981 opinion of the court

of appeals is reported at 644 F.2d 1112,

and is set out in the Appendix hereto, pp.

3a-53a. The decision of the district court

of October 16, 1979, which is not official

ly reported, is reprinted in 22 FEP Cases

1695, and is set out in the Appendix

hereto, pp. 58a-110a.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals

was entered on May 14, 1981. A timely

petition for rehearing was denied on

August 7, 1981. On October 19, 1981, Mr.

Justice Powell granted an order extending

the time in which to file a petition for

writ of certiorari until December 7, 1981.

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

28 U.S.C., § 1254(1) .

3

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

Section 706(b) of the 1964 Civil

Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(b), pro

vides in pertinent part:

Whenever a charge is filed by or

on behalf of a person claiming to be

aggrieved, or by a member of the

Commission, alleging that an employer,

employment agency, labor organization,

or joint labor management committee

controlling apprenticeship or other

training or retraining, including

on-the-job training programs, has

engaged in an unlawful employment

practice, the Commission shall serve a

notice of the charge (including the

date, place and circumstances of the

alleged unlawful employment practice)

on such employer, employment agency,

labor organization, or joint labor-

management committee (hereinafter

referred to as the "respondent")

within ten days and shall make an

investigation thereof. Charges shall

be in writing under oath or affirma

tion and shall contain such informa

tion and be in such form as the

Commission requires.

Section 706(f)(1) of that Act, 42 U.S.C.

2 0 0 0e-5(f ) (1 ) , provides in pertinent

part:

4

If a charge filed with the

Commission pursuant to subsection

(b) is dismissed by the Commission,

or if within one hundred and eighty

days from the filing of such charge or

the expiration of any period of ref

erence under subsection (c) or (d),

whichever is later, the Commission has

not filed a civil action under this

section or the Attorney General has

not filed a civil action in a case

involving a government, governmental

agency, or political subdivision, or

the Commission has not entered into a

conciliation agreement to which the

person aggrieved is a party, the

Commission, or the Attorney in a case

involving a government, governmental

agency, or political subdivision,

shall so notify the person aggrieved,

and within ninety days after the

giving of such notice a civil action

may be brought against the respondent

named in the charge (A) by the person

claiming to be aggrieved or (B) if

such charge was filed by a member of

the Commission, by any person whom the

charge alleges was aggrieved by the

alleged unlawful employment practice.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This action was commenced on October

4, 1972, against the United States Pipe and

Foundry Company and several local and

5

international unions. The complaint al

leged systematic discrimination in job as

signment, training and promotion of black

employees.

Following extensive discovery, all

parties to the litigation agreed upon

injunctive relief, including modification

of the seniority system at the plant. The

company agreed to pay $510,000 in back pay

in settlement of any monetary claims

against it by the class members. Plain

tiffs agreed not to seek back pay against

1/ Twelve unions were named as defen

dants. Brotherhood of Boilermakers,

Blacksmiths, Forgers, and Helpers and its

Local 583; International Association of

Machinists and Aerospace Workers and its

Lodge 359; International Molders and

Allied Workers Union and its Local 342;

Patternmakers League of North America and

its affiliate, Patternmakers Association

of Birmingham; United Steelworkers of

America and its Local 2140; and Interna

tional Brotherhood of Electrical Workers

and its Local 136. Prior to trial Summary

Judgment was granted in favor of the IBEW.

No appeal was taken from this Judgment.

6

Local 136, IBEW. The issue reserved

for trial was the monetary liability of the

remaining union locals and internationals.

Black employees had for decades been

assigned on the basis of race to poorly

paid "dead end" jobs. Under the seniority

system in operation at the plant prior to

the pretrial settlement, an employee's

seniority was based on his length of

service in a particular department or

seniority unit, rather than service at the

plant. A black worker with decades of

service in one of the poorly paid predomi

nantly black positions necessarily for

feited his seniority upon transferring to

a traditionally white job. The seniority

system effectively locked blacks into

positions to which they had been assigned

on the basis of race.

7

The critical issue regarding union

liability was whether the seniority system

to which they were parties was created

or maintained with the intention to dis

criminate. International Brotherhood of

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324

(1977). The separate seniority units

into which employees were segregated

largely coincided with the six distinct

bargaining units represented by the six

unions at the plant. Five of these unions

were virtually all-white; on the other

hand the Steelworkers, which represented

the poorly paid black workers, was predom

inantly black. Plaintiffs advanced

three basic claims regarding the intention

behind the establishment and maintenance of

the seniority system.

Plaintiffs urged, first, that a

realignment of the seniority system which

had occurred in 1950 was racially moti

8

vated. In that year 1 0 positions repre

sented by the Steelworkers, but staffed by

whites, were transferred to the bargaining

units represented by the Boilermakers and

Machinists. At the same time all the black

workers represented by the Boilermakers

and Machinists were transferred to the

bargaining unit represented by the predomi

nantly black Steelworkers. As a result of

this realignment the Boilermakers and

Machinists joined the Patternmakers and

Electrical Workers in having all white

memberships. The blacks formerly repre

sented by the Boilermakers and Machinists

were precluded from promotion into the

positions represented by these unions,

while whites in the positions switched to

those unions were afforded an opportunity

to promote into jobs from which the

blacks who remained in the Steelworkers

9

were effectively excluded. The district

court held that the 1 9 50 realignment

was racially motivated, and that this

aspect of the seniority system was illegal.

This finding was upheld on appeal.

Plaintiffs also attacked those aspects

of the seniority system created prior to

1950. The record showed that, when

the plant was first organized in 1939, four

of the unions, whose bargaining units were

to define the seniority units, sought only

to represent all or overwhelmingly white

positions; none of them attempted to rep

resent the predominantly black positions.

In 1949 the Molders union successfully

sought NLRB approval to represent the

molders and the apprentices, all of whom

were white, but did not seek to represent

the molder helpers, who were black.

During the period when the seniority system

was created the Boilermakers, Machinists,

Molders, and Patternmakers each maintained

"overtly discriminatory policies .... [t]he

Machinists barred blacks from union member

ship, the Boilermakers relegated blacks to

inferior 'auxiliary' locals, the Molders

segregated the few blacks in their Alabama

locals, and the Patternmakers claimed that

there were no 'qualified niggers' in that

state." App. 28a-29a. Nonetheless, the

district court held that the decisions of

these unions to seek to represent only

white workers — decisions which led to the

creation of the correspondingly all-white

bargaining and seniority units — were not

racially motivated. The court of appeals

reversed, holding that this aspect of

the seniority system, like the 1950 re-

alighment, was the result of intentional

discrimination. App. 29a-31a,

- 10 -

Finally, the plaintiffs argued that

the seniority system was maintained with

an intent to discriminate. The record

shows that the all-white unions, Boiler

makers, Machinists, Molders and Pattern

makers opposed the efforts by the company

and the Steelworkers to modify the senior

ity system so as to permit blacks to

transfer to traditionally white jobs. While

acknowledging that "[rjacial considerations

were involved in the 1968, 1971, 1975, and

1977 negotiations concerning the modifica

tion of seniority," the district court

held that the unions had not intentionally

discriminated in refusing to modify the

system. App. 102a-04a. The Fifth Circuit

reversed and found that "the collective

bargaining process tracked and reinforced

the purposefully segregated job classifies-'

tion scheme ... and the conclusion is

- 1 1 -

12

inescapable that the seniority system

itself shared in that same unlawful pur

pose. " App. 26a.

The aspect of the ligitation below

with which this petition is concerned is

the extent to which the international

unions are liable for back pay awards for

2/this proven illegality. The initial 1969

EEOC charges, prepared by plaintiffs without

the assistance of counsel, referred in only

general terms to the union responsibility

for the discriminatory seniority system.

In 1973, with the assistance of counsel,

plaintiffs amended their EEOC charges to

2/ The international unions affected by

this question are the Boilermakers, Machin

ists, Molders, and Patternmakers. The Fifth

Circuit ruled that these internationals

were liable for the discriminatori1y

unlawful seniority system. The Fifth

Circuit found that the Steelworkers were

not liable and the plaintiffs do not seek

review of this determination.

name expressly both the intentionals /s

I

well as their local affiliates. The

district court held that the 1969 charges

did not adequately name the internationals,

and that the internationals' Title VII

liability therefore only commenced 180 days

before the 1973 amendment to the charge,

while the locals were held liable for

damages beginning 180 days before the

original 1969 charges. App. 68a-69a. The

district court also held that the interna

tional unions were subject to suit under

42 U.S.C. § 1981, and concluded that the

§ 1981 liability of the internationals

commenced in 1971, one year prior to the

filing of this action. App. 67a. The

court of appeals affirmed the district

court's decision that the 1969 EEOC charges

had not adequately named the interna

tional unions. App. 51a. Thus, whether

the 1969 charges were in fact sufficient to

provide a basis for a Title VII action

against the internationals controls whether

those internationals can be held liable for

back pay claims for the period from Jan

uary, 1969 through October, 1971.

The charges in a variety of ways

implicated the international unions. There

is some minor variations in the charges

filed against each of the four interna

tionals and in the relationships between

each international and its local. However,

the record indicates that the charges

reasonably read refer to the internationals

and that the internationals were closely

involved in the affairs of their locals and

the establishment and maintenance of the

unlawful seniority system. First, the

charges all but expressly name the inter

nationals and expressly state that

"unions," not just a local, were involved

1/in the discrimination. Second, the

charges referred to the role of "unions" in

the discriminatory division of the plant

into bargaining units. This reference

necessarily implicates the internationals

because the division of the plant into

bargaining units resulted from actions

taken by the internationals since locals

did not exist at the plant prior to the

1/

3/ For example, in one charge the

alleged discriminator is listed as "Inter

national Association of Machinists &

Aerospace Workers, Lodge 359." The peti

tioners have attached to this petition a

chart which sets forth the name of the

alleged discriminator and the substance of

the charge exactly as it appears on the

1969 charges. Attachment A.

4/ For example, one charge states that

T [t]he Patternmakers Union, along with

other Unions, and the Company, have the

departments divided up so Negroes would

lose their seniority if they bid on some

better jobs." Attachment A.

certifications of the bargaining units by

the National Labor Relations Board.

Third, the bargaining units and the

seniority system which were alleged to be

discriminatory in the 1969 charges were

maintained in collective bargaining agree

ments to which the internationals were

1 /parties. Finally, the international

representatives took major roles in the

collective bargaining negotiations and the

constitution for each international

establishes close supervision and control

of the locals by the internationals.

5/ For example, the 1971 Machinists

Agreement provides that "[t]his Agreement

... is made ... between [the Company] and

the International Association of Machinists

and Aerospace Workers on behalf of itself

and Lodge 359 (hereinafter called the

Union) ...." Plaintiffs' Exhibit 6 , p. 3;

see Plaintiffs' Exhibits 5-8 (Machinists);

Plaintiffs' Exhibits 9-12 (Boilermakers);

Plaintiffs' Exhibits 19-20 (Patternmakers).

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

This case is among the latest in over

70 reported decisions on a problem of

substantial and growing importance to the

enforcement of Title VII of the 1964 Civil

Rights Act. Title VII authorizes aggrieved

persons to file suit against "the respon

se/

dent named in" an administrative charge

of employment discrimination filed earlier

with the EEOC. Among the 40,000 charges

filed with the EEOC each year, the vast

majority are prepared by workers who

have limited education and who lack legal

counsel. Unschooled in the intricacies of

the law, these charging parties frequently

do not distinguish among closely associated

entities -- between corporations and

6/ Section 706(f)(1); 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5-

( f ) ( 1 ) .

18

7/ 8/

their parent or sister companies, be -

tween inter-related agencies of the same

1 / 1 0 /city or state , between public or pr i-

]_/ Stith v. Manor Baking Co. ,418 F.

Supp, 150 (W.D. Mo. 1976); Bernstein v .

National Liberty International Corp., 407

F. Supp. 709 (E.D. Pa. 1976); see also

Escamilla v. Mosher Steel Co., 386 F. Supp.

101 (S.D. Tex. 1975).

8/ Canavan v. Beneficial Finance Corp.,

55 3 F.2d 860 (3d Cir. 19 77 ) .

9/ Davis v. Weidner, 596 F.2d 726 (7th

Cir. 1979); Wells v. Hutchinson, 499 F.

Supp. 174 (E.D. Tex. 1980); Henry v. Texas

Tech. University, 466 F, Supp. 141 (N.D.

Tex. 1 9 7 9); Schick v. Brons t e _i ri , 447

F. Supp. 333 (S.D.N.Y. 1978); Curran v .

Portland Superintending School Committee,

435 F. Supp. 1063 (Me. 1977).

10/ Friedman v, Weiner, 515 F. Supp. 563

(Colo. 1981); Women in City Government

United v. City of New York, 515 F. Supp.

295 (S.D.N.Y. 1981); Goodman v. Bd . of

Trustees of Community College, 498 F. Supp.

1329 (N.D. 111. 1980); Jacobs v. Board of

Regents, 473 F. Supp. 663 (S.D. Fla. 1979);

Vanguard Justice Society, Inc, v. Hughes,

471 F. Supp. 670 (Md. 1979); .

Richland School Dist. No. 2, 463 F. Supp.

216 (S.C. 1978); Vogel v. Torrence Bd. of

Educ.,447 F. Supp. 258 (C.D. Cal. 1978);

Lewis v. Southeastern Pennsylvania Transp.

19

vate entities and their chief executives

or officials, between local unions and

12/

councils or committees of locals, and es-

11/

1 0/ continued

Authority, 440 F. Supp. 887 (E.D. Pa.

1977); Skyers v. Port Authority of New York

and New Jersey, 431 F. Supp. 79 (S.D.N.Y.

19 7 6 ) ; Jackson v. University of Pittsburgh,

405 F. Supp. 607 (W.D. Pa. 1975); Hanshaw

v. Delaware Technical and Community Col

lege , 405 F. Supp. 292 (Del. 1975); Byron

v. University of Florida, 403 F. Supp. 49

(N.D. Fla. 1975); Scott v. University of

Delaware, 385 F. Supp. 937 (Del. 1974).

11/ Watson v. Gulf S Western Industries,

650 F.2d 990 (9th Cir. 1981); Martin v .

Publishing Co. , 478 F. Supp.

796 (E.D. Pa. 1979); Flesch v. Eastern

Pennsylvania Psychiatric Institute, 434 F.

Supp. 963 (E.D. Pa. 1977); Hochstadt v .

Worchester Foundation, 425 F. Supp. 318

(Mass. 1 9 7 6 ); _Xerox

Corp. , 368 F. Supp. 829 (N.D. Cal. 1973);

Chastang v, Flynn & Enrich Co. , 3 6 5 F.

Supp. 957 (Md. 1973); M_c D o n a 1 d __ v .

American Federation of Musicians, 3 0 8 F.

Supp. 664 (N.D. 111. 1970).

12/ Eggleston v. Plumbers' Local 130, 26

FEP Cases 1192 (7th Cir. 1981); Eldredge

v. Carpenters Joint Apprenticeship Commit

tee , 440 F. Supp. 506 (N.D.Cal. 1977); But

ler v. Local No., 4, Laborers International

Union, 308 F. Supp. 528 (N.D. 111. 1969).

20

pecially between local unions and the in

ternational unions with which they are

13/

connected.

In the ensuing Title VII litigation

defense counsel understandably insist that

each legal entity must have been listed

separately in the EEOC charge with the same

precision one might expect of a skilled

attorney drafting a civil complaint. The

instant case is just one of the rapidly

increasing number of decisions concerning

when and how such related entities and

individuals must be named in the charge.

The law in the lower courts on this

important issue is not merely in a state of

conflict; it borders on chaos. There are

no fewer than nine different court of

appeals' standards for deciding this

13/ See nn. 58-71, infra.

21

question. Three Circuits have established

conflicting standards for determining

whether a charge adequately "names" a

particular respondent. Another three

appellate rules have established varying

standards for subjecting an unnamed party

to suit because of events occurring

in the EEOC investigation and conciliation

process. A final three appellate rules

provide that under certain conditions a

defendant neither named in an EEOC charge

nor involved in the administrative charge

may nonetheless be sued in a Title VII

action. The district courts, under

standably confused by this diversity of

appellate opinion, have formulated at least

18 other standards of their own. Each year

witnesses the creation of still different,

overlapping and conflicting standards.

Certiorari should be granted to bring to an

end this outpouring of legal creativity.

22

This Court has repeatedly recognized

the importance of eliminating confusion

arising from conflicting judicial inter

pretation of administrative filing require

ments under Title VII. Love v. Pullman

Co. , 404 U.S. 522 (1972 ) (requirement of

filing with a state agency); I . U .E. v .

Robbins & Myers Co., 429 U.S. 229 (1976)

(tolling of time period); United Air Lines

v. Evans, 431 U.S. 553 (1977) (timeliness

of charge); Mohasco Corp. v. Silver, 447

U.S. 807 (1980) (interpretation of when a

charge is "filed"); Delaware State College

v. Ricks, 449 U.S 250 (1980) (commencement

of the time period). Having resolved

conflicting interpretations of the provi

sions requiring a timely filing and a

proper deferral to state agencies, the

Court should resolve the conflicts regard

ing when an employer or union is properly

"named in" an administrative charge.

23

Moreover, the large and increasing number

of fair employment cases ensures that the

confusion arising from varying judicial

approaches to the interpretation of the

requirement that a defendant be named in an

administrative charge will increase unless

this Court establishes the proper standard.

In the twelve month period which ended June

30, 1981, 6,245 Title VII cases were filed.

Annual Report of the Director of Adminis

trative Office of the United States Courts

(Wash. 1981), p. 75. These filings reflect

a 350% increase over filings in 1973 and a

more than 2 0 % increase over filings in

1980. Id.

The courts of appeals have announced

three different standards for deciding

whether a charge adequately "names" a

particular respondent. The Ninth Circuit

will "read sympathetically" the language of

the charge; thus a complaint was held

to name an international union where it

identified the party alleged to have

discriminated as:

I.A.T.S.E. Local 659 — Interna

tional Photographers of the

Motion Picture Industries 15/

In the instant case the Fifth Circuit ruled

that charge must "allege specific conduct

which clearly implicate[s]" the disouted

16/party. Thus the Fifth Circuit concluded

that the charges had not named the interna

tional unions although they were actually

listed in language hardly distinguishable

from that approved in the Ninth Circuit:

- 24 -

11/

14/ Watson v. Gulf & Western Industries,

¥50 F. 2d at 9"93Z

15/ Kaplan v. International Alliance of

Theatrical Workers, 525 F.2d 1354, 1359

(9th Cir. 1975).

16/ App. 51a.

25

Brotherhood of Boilermakers,

Blacksmiths, Forgers, Helpers,

Local 583

International Association of

Machinists and Aerospace Workers,

Lodge 359

International Holders & Allied

Workers, Local 342, 17/

11/ 11/The District of Columbia and Third

Circuits apply yet a third rule requiring

that the language of a charge, including

the specific allegations of discrimination,

be sufficient to provide the EEOC with a

"reasonable" opportunity to investigate the

conduct of the putative defendant and at-

20/

tempt conciliation. Thus in the Third

17/ Plaintiffs' Exhibit 6 6; see Attachment

A to this Petition,

18/ Shehadeh v. Chesapeake & Potomac Tele

phone Co., 595 F. 2d 711 , 728 (D.C. Cir.

1978 ) .

19/ Canavan v. Beneficial Finance Corp.,

supra.

20/ Id. 863-64.

26

Circuit expressly listing a defendant in

the portion of the EEOC charge form for

"Others Who Discriminated Against You" is

not by itself necessarily sufficient.

Furthermore, there are three different

appellate rules regarding whether, even

where a defendant is not named in the EEOC

charge, events occurring in the EEOC

investigation and conciliation process

which follows the filing of the charge may

render it subject to suit. In the Seventh

21/

Circuit it is sufficient that such a

defendant have received both notice

of the pending charge of discrimination and

been given an opportunity to participate in

the conciliation process, regardless of

21/ Eggleston v. Plumbers' Local 130, 26

FEP Cases at 1203; Davis v. Weidner, supra;

see also Williams v. General Foods Corp.,

492 F . 2 d 399, 404-05 (7th Cir. 197 4).

27

itself would have provided such a notice.

In the Ninth Circuit an unnamed defendant

may later be sued if it was actually served

with the charge and treated as a party

22/

to the EEOC proceeding In the Third

Circuit an unnamed defendant is subject to

suit if its interests were adequately

represented during the EEOC proceeding by a

23_

party that was named.

Finally, there are three different

rules regarding whether a defendant

neither named in an EEOC charge nor

involved d_e facto in the EEOC proceeding

may nonetheless be sued in a subsequent

whether a literal reading of the charge

22/ Gibson v. Local 40, Supercargoes,

etc., Union, 543 F.2d 1259, 1263, n. 1 (9th

Cir. 1976).

23/ Ricks v. Delaware State College, 605

F.2d 710 (3rd Cir. 1979), rev1 d on other

grounds, 449 U.S. 250 (1980).

28

24/ _25/

Title VII action. The Third, Seventh

2_6/

and Tenth Circuits allow such suits if

the four-part test announced in Glus v. G.

C. Murphy, 562 F.2d 880, 888 (3rd Cir.

1977), is met. Under Glus a court con

siders each of the following factors,

no one of which appears to be either

necessary or sufficient:

(1 ) whether the role of the unnamed party could through the reason

able effort by the complainant be

ascertained at the time of the

filing of the EEOC complaint;

(2 ) whether, under the circumstances,

the interests of a named party

are so similar as those of the

unnamed party's that for the

24/ Glus v. G. C. Murphy, 562 F.2d 880 (3d

Cir. 1977); see Glus v. G. C. Murphy 629

F.2d 248 (3d 1980), vac. and rem. on other

grounds, 101 S. Ct. 2013 (1981).

25/ Eggleston v. Plumbers' Local 130, 26

FEP Cases at 1205.

26/ Romero v. Union Pacific R.R., 615 F.2d

1303, 1312 (10th Cir. 1980).

29

purpose of obtaining conciliation

and compliance it would be

unnecessary to include the

unnamed party in the EEOC pro

ceedings ;

(3) whether its absence from the EEOC

proceedings resulted in actual

prejudice to the interests of the

unnamed party;

(4) whether the unnamed party has in

some way represented to the

complainant that its relationship

with the complainant is to be

through the named party.

In the Tenth Circuit, in addition to these

criterion, "additional factors may be

27/ 28/

relevant." The Sixth and Seven-

29/

th Circuits follow a decision in the

District of Columbia Circuit in Evans v.

Sheraton Park Hotel, 503 F.2d 177, 180-83

27_/ Id.

28/ EEOC v. McLean Trucking Co., 525 F.2d

TTT07 {6th Cir. 1975)/

29/ Eggleston v. Plumbers' Local 130, 26

FEP Cases at 12715 n7 TIZ

30

3 0 /

(D.C. Cir. 1974) , which permits joinder

of a party unnamed in the EEOC charge if

its presence in the Title VII lawsuit is

necessary to provide complete relief. In

the instant case petitioner repeatedly

11/urged the Fifth Circuit to follow Glus,

but it declined to do so.

Faced with these conflicting and

overlapping appellate standards, the

district courts, rather than attempting to

follow one line of decisions or another,

have fashioned new criteria of their own,

sometimes drawing on the reasoning of

the appellate decisions, often breaking new

30/ See also Macklin v. Spector Freight

Systems, Inc., 478 F.2d 979 (D.C. Cir.

1973 ) .

31/ Brief for Appellants, pp. 82, 84;

Appellants' Petition for Rehearing, pp. 14,

16; Appellants' Suggestion for En Banc

Consideration, pp. 13, 15.

31

ground. The circumstances under which the

district courts will permit a defendant not

literally named in the EEOC charge to be

sued under Title VII include: (1) the

unnamed defendant had actual notice of the

32/

EEOC charge, (2) the unnamed defen

dant had notice and the named defendant was

3 3/

its agent (3) the unnamed defendant

had notice and was an agent of the named

34/defendant (4) the unnamed defendant

had notice and had a legal relationship

32/ Vanguard Justice Society, Inc, v .

Hughes, 471 F. Supp. at 688-89; Willi jams

v. Massachusetts General Hospital, 449 F.

Supp. 55 (Mass. 197’8) ; Hanshaw v. Delaware

Technical and Community College, 405 F.

Supp. at 2 96 ; Skyers v~. Port Authority of

New York and New Jersey, 431 F. Supp. at

81 ; Lewis v. Southeastern Pennsylvania

Transportation Authority, supra.

33/ Kelly v. Richland School District No.

2, 463 F/ Supp. at 219; Stith v. Manor

Bakina Co., supra.

34/ Curran v. Portland Superintending

School Committee, 435 F. Supp, at 1074.

32

unnamed defendant had notice and its

interests were adequately represented by

36/

the named defendant, (6) the unnamed

defendant had notice, the named defendant

was its agent, and the unnamed defendant

had an opportunity to participate in

3/7/

conciliation, (7) the unnamed defen

dant had notice and an opportunity to com-

38/

ply voluntarily with the law, (8 ) the

35/

with the named defendant, (5) the

35/ Stevenson v. International Paper Co.,

432 F. Supp. 390 , 398 (W.D. La. 197 7 ).

36/ Jacobs v. Board of Regents, supra;

Stringer v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

Department of Community Affairs, 446 F.

Supp. 704, 706 (M.D. Pa. 1978).

37/ Plummer v. Chicago Journeyman Plumb

ers , 452 F. Supp. 1127, 1134 (N.D. 111.

1978), rev'd on other grounds sub nom.,

Eggleston v. Plumbers' Local No. 130, 26

FEP Cases 1192 (7th Cir. 1981).

38/ Batis v. Great American Federal Sav

ings & Loan Ass 'n, 452 F. Supp. 588 , 590

(W.D. Pa. 1978).

33

was a substantial identity between it and

39/

the named defendant, (9) the unnamed

defendant had notice and actually partici-

40/

pated in conciliation, (1 0 ) the unnamed

defendant had notice and its joinder is

41/

necessary for complete relief, (1 1 )

there is a substantial identity between the

4 2/

named and unnamed defendants, (1 2 )

unnamed defendant had notice and there

39/ Kelly v. Richard School District No.

2, 463 F. Supp. at 219.

40/

336;

Schick v. Bronstein,

Bernstein v. National

447 F.

Liberty

Supp. at

Interna-

tional Corp., 407 F. Supp. at 715.

41/ Kelly v. Richland School District No.

2, 463 F. Supp. at 219.

42/ Stith v. Manor Baking Co . , 41 8 F .

Supp . at 156-57; Wells v. Hutchinson, 499

F. Supp. at 190; Goodman v. Board of Trus-

tees of Community College, 498 F. Supp. at

1333 ; Curran v. Portland Superintending

School Committee, 435 F. Supp. at 1074 ;

Scott v. University of Delaware, 3 8 5 F.

Supp. at 941; Chastang v. Flynn & Emrich

Co., 365 F. Supp. at 964 ; McDonald v. Am

erican Federation of Musicians, 308 F.

Supp. at 669.

34

the named and unnamed defendants are not

11/

"autonomous," (13) the unnamed defen

dant was a necessary party for concilia-

44/

tion, (14) the unnamed defendant was a

45/necessary party for voluntary compliance,

(15) the charge was sufficient to notify

EEOC of the involvement of the unnamed

46/

party, (16) the named defendant was act

ing as an agent of the unnamed defendant

, . . 47/when it engaged in the discrimination,

43/ Hardison v TWA, 375 F. Supp. 877, 880

(W.D. MoT 1974) , rev'd on other grounds,

527 F .2d 33 (8th Cir. 1975), rev'd, 432

U.S. 63 (1977); Moody v. Albemarle Paper

Co•/ 271 F. Supp. 27 (E.D.N.C. 1967).

44/ Coley v. M & M Mars, Inc., 461 F.

Supp. 1073, 1075 (M.D. Ga. 1978).

I V Chastang v, Flynn & Emrich Co., 365 F. Supp. at 963.

46/ Eldredge v. Carpenters Joint ApDren-

ticeship Committee/ 41T0 FT Supp. at " 525.

11/ EEOC v. International Brotherhood of

!A.ectr leal Workers/ 471 FI Supp. 3 41,

346-47 (Mass. 1979); Puntolillo v. New

Hampshire Racing Commission, 390 FT Supp.

231, 236, n. 4 (N.H. 1975).

35

the discriminatory scheme and was repre

ss!/

sented at conciliation. Some courts

require that the respondents be precisely

named and reject the inclusion of unnamed

parties under any of these seventeen

49/

circumstances. Which standard a par

ticular district court will choose to

apply in a given case simply cannot be

predicted.

The conflict which has spawned this

diversity of standards among the federal

courts is widely recognized. The Third

and (17) the unnamed defendant was part of

48/ Hochstadt v. Worchester Foundation,

425 F. Supp. at 323.

49/ Vogel v. Torrence Board of Education,

Tf7 F̂ Supp. at 266 ; Wallace v. Interna

tional Paper Co., 426 F. Supp. 352, 357

(W.D. La. 1977); Jackson v. University of

Pittsburgh, 405 F. Supp. at 617; Jamison

v. Olga Coal Co., 335 F. Supp. 454 (S.D.

W.Va. 1971).

36

Circuit observed that while the Sixth

Circuit has followed the District of

Columbia Circuit's joinder practice, other

courts "have held to the contrary under

5 0 /

similar circumstances." The Fifth Cir

cuit noted this same conflict in reserving

judgment on this issue several years

5 1 /

ago. The district courts have taken

notice of the "divergence of authority" as

to whether a Title VII defendant must have

5 2 /

been literally named in the EEOC charge

and regarding whether any naming require-

50/ Canavan v. Beneficial Finance Corp., 553 F. 2 <3 at 865. ’

51/ Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Corp.

T9 8 F . 2 d~6TI7 "647 n. 6 ( 5TF—CY'rl 1974); see

also Flesch v. Eastern Pennsylvania Psy

chiatric Institute, 434 F. Supp. at 971;

Puntolillo v. New Hampshire Racing Commis

sion , 390 F. Supp. at 235-36.

52/ Byron v. University of Florida, 403 F.

Supp. at 53.

37

ment is jurisdictional in nature.

District court opinions expressly disap

proving contrary appellate or district

court decisions announcing differing

54/

rules are common.

The largest and most important cate

gory of cases in which this issue arises

concerns whether, and if so how, an

aggrieved employee must separately name the

international union as well as the union

local in order to be able to sue the

international in a Title VII action; "[t]he

11/cases are divided" over the issue. This

1 1 /

53/ Henry v. Texas Tech University, 4 6 6 F.

Supp. at 150.

54/ Curran v. Portland Superintending

Fchool Committee, 4 3 5 FT Supp. ah 10 7 4 ;

Stith v. Manor Baking Co., 418 F. Supp. at

155-57; see also, Butler v. Local No. 4,

Laborers International Union, 308 F. Supp.

at 531; McDonald v. American Federation of

Musicians, 308 F. Supp. at 669.

55/ Stevenson v. International Paper Co.,

432 F. Supp. at 396.

38

is a frequently recurring problem for two

reasons. First, in most class action

litigation union locals are effectively

judgment proof; the average local treasury

has less than $50,000 and over 8,000 locals

of the approximately 46,000 locals which

file reports with the Department of Labor

56/

have no assets at all. The typical

international, by comparison, has almost

$ 1 0 million in assets, and over 1 1 million

_57/

in annual income.

Second, while the availability of the

international as a defendant is often of

vital legal importance, this is not

a distinction that would necessarily be

made by the ordinary charging party. In

court union attorneys may understandably

56/ Statistical Abstract of the United

States, 1980, p. 430 Table 717.

57/ Id.

39

seek to minimize the relationship between

an international and its locals; but on the

shop floor, and in representation elec

tions, both union members and union offi

cials take a very different approach.

Among the international unions which have

sought to thus disassociate themselves from

their locals, and have urged that they must

be listed separately in a pro se Title VII

charge, are the International Brotherhood

58/

of Teamsters, the United Steelworkers

59/ 60/

of America, the United Mine Workers,

the International Longshoremen ' s and Ware-

61/

housemen's Union, the International As-

58/ Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems,

Inc., 478 F.2d at 993, n. 25.

59/ Taylor v. Armco Steel Corp., 373

F. Supp. 885 (S.D. Tex. 1973).

60/ Jamison v. Olga Coal Co., 335 F. Supp.

at 460.

61/ Gibson v. Local 40, Supercargoes,

Union, 543 F.2d at 1 2 63, n. 1.

40

sociation of Machinists, the Interna-

63tional Brotherhood of Electrical Workers,

the United Electrical, Radio and Machine

64/

Workers, the Brotherhood of Railway and

65/

Airline Clerks, the International Print-

66/ing and Graphic Communications Union,

the International Wholesale and Department

67/

Store Union, the International Alliance

62

62/ Hardison v. TWA, supra.

63/ EEOC v. International Brotherhood of ETectrical Workers, supra/ "

64/ Torockio v . Chamberlin Mfg. Co. 51

F.R.D. 517 (W.D. Pa. 1970).

65/ Roberts v. Western Airlines, 425 F.

Supp. 416'(N.D. Cal. 1976).

66/ Braxton v. Virginia Folding Box Co.,

72 F.R.D. 124 (E.D. Va. 1976). ‘ ‘

67/ Glus v. G. C. Murphy Co.,

(3rd Cir. 1977). 562 F.2d 880

41

6 8/

of Theatrical Workers, the United

6 9 /

Glass and Ceramic Workers, the Inter-

7 0 /

national Brotherhood of Painters, and

the International Brotherhood of Pulp,

21/Sulphite and Paper Mill Workers.

The standard established by the Fifth

Circuit in this case conflicts, not only

with the plethora of lower court decisions

on the same subject, but with the general

principles established by this Court for

construction of Title VII. The Fifth

Circuit standard is unique in its harsh-

6 8/ Kaplan v. International Alliance of

TKeatrical Workers, supra/

69/ LeBeau v. Libby-Owens-Ford Co., 484

F.2d 798 (7th Cir. 1973) .

70/ EEOC v. Brotherhood of Painters, 384

F. Supp. 1264 (S.D. 1974).

71/ Stevenson v. International Paper Co.,

supra.

42

ness. The 1969 charges which the court of

appeals held failed to adequately name any

international union in fact listed among

the parties which had engaged in discrimi

nation :

International Association of

Machinists & Aerospace Workers,

Lodge 359

International Holder & Allied Workers, Local 342

Brotherhood of Boilermakers,

Blacksmiths, Forgers, Helpers,

Local 583 72/

The purported deficiency of these charges

apparently must consist in the use of a

comma, rather than a semicolon, after the

word "workers." "Such technicalities are

particularly inappropriate in a statutory

scheme in which laymen, unassisted by

trained lawyers, initiate the process."

Love v. Pullman Co., 404 U.S. at 527; see

72/ Plaintiffs' Exhibit 6 6; Attachment A.

43

750, 761 (1979); Mohasco Corp. v. Silver,

447 U.S. at 816 n. 19. Four of the charges

alleged broadly that the discrimination had

been by the "union," not limiting the ac

cusation to the locals, and one charge ex-

73/

pressly complained of a union contract

which had in fact been negotiated and

74/

signed by an international. In holding

that these charges "failed to allege

specific conduct which clearly implicated

1 1 /the Internationals" the Fifth Cir

cuit set a standard far more stringent

than any court would apply under the Fed

eral Rules of Civil Procedure to a civil

complaint , Conley v ._Gj.bson , 35 5 U.S.

also Oscar Mayer & Co v . Evans, 441 U.S.

73/ Id.

74/ See nn.3-5, supra, and accompanying

text.

75/ Appendix App. 51a.

- 44

41 , 45-46 (1957 ), and far beyond what can

reasonably be asked of such pro se allega

tions. Haines v. Kerner, 404 U.S. 519

520 (1972); Hughes v. Rowe, 449 U.S. 5,

(1980).

Regardless of what standard this Court

believes should apply to these cases,

certiorari should be granted to end

the extraordinarily complex and widespread

differences which exist among the lower

courts. The present confusion in the

law invites defendants to challenge, and

prompts plaintiffs to support the adequacy

of the allegations in virtually any charge.

This necessarily prolongs and complicates

the judicial resolution of any case, and

reduces the likelihood that these cases can

be settled short of trial.

The EEOC, which receives more than

40,000 charges a year, several thousand of

45

them regarding discrimination by unions,

is in need of guidance as to the parties it

can or should investigate in the face of a

typically broadly written charge. EEOC

employees in offices throughout the coun

try who are directed by the Commission

to assist complainants in drafting their

77/

charges must have a clear standard in

order to assure that they do not mislead

complainants, as apparently occurred in

28this case. Further decisions by the lower

76/

7 6/ Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion, 12th and 13th Annual Reports, pp. 48,

59 (1981).

77/ EEOC Compliance Manual, § 2.

78/ The same ambiguities are apparent in

all the 1969 charges, each of which was

sworn to and drafted in the hand of a

single EEOC Field Representative, Jerry

Swift. Plaintiffs Exhibit 6 6. It was the

EEOC Field Representative who failed

precisely to distinguish between the

respective locals and internationals and

unambiguously to name both as discriminat

ing respondents. As clear as it is that

46

courts will only deepen and exacerbate the

many-sided conflict which already exists

among the more than 70 reported decisions.

Only action by this Court can establish a

clear and uniformly applied standard.

78/ continued

plaintiffs should not be penalized for

layman's lack of verbal precision, it

is equally unfair to penalize them "for

administrative laxity or ineptness on the

part of the EEOC." Thornton v. East Texas

Motor Freight, Inc., 497 F.2d 416, 424 (6th

Cir. 1974).

47

CONCLUSION

For the

Certiorari

judgment and

foregoing reasons, a Writ of

should issue to review the

opinion of the Fifth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted

JOSEPH P. HUDSON

1909 30th Avenue

Gulfport, Mississippi

39501

DANIEL B. EDELMAN

Yablonski, Both &

Edelman

Suite 800

1140 Connecticut

Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

DEMETRIUS C. NEWTON

2121 8th Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN-/

Suite 940

806 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

202-638-3278

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

0. PETER SHERWOOD

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New7 York

10019

Attorneys for Petitioners

*/ Counsel of Recor

ATTACHMENT A

Complainant

Jackson

Dudley

Mason

Long

EEOC CHARGES FILE D IN 1969

Alleged Union Discriminators Allegations

“ Brotherhood of Boilermakers,

Blacksmiths, Forgers, Helpers,

Local 583”

“ The Boilermakers Union does not admit Ne

groes and is party to a contract and a dis

tribution of bargaining units that perpe

trates segregated departments and dead end

jobs for Negroes.”

“ International Association o f “ The Union fails to admit Negroes and is

Machinists & Aerospace Workers, party to a discriminatory division o f jobs.”

Lodge 359”

“ International Molders & Allied “ The Local does not press grievances for Ne-

W orkers, Local 342” groes and treats Negroes discriminatorily

in other ways.”

“United Steelworkers of America, “ The Company and the Union along with

AFL-CIO ” other Unions are party to a discriminatory

division of the Plant and its departments

into different bargaining units.”

SO U R C E : Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 66.

Complainant

Walker

Adams

Alleged Union Discriminators

“ Patternmakers Association of

Birmingham, affiliated with the

Patternmakers League of North

America, A FL-C IO ”

“ International Brotherhood of

Electrical Workers, Local No.

136”

ATTACHMENT A, Page 2

Allegations

“ There are no Negro members of Pattern

makers Union at U.S. Pipe, Bessemer Pipe

Plant.”

“ The Patternmakers Union, along with other

Unions, and the Company, have the depart

ments divided up so Negroes would lose

their seniority if they bid on some better

jobs.”

“ The Electrician’s Union, along with several

other Unions and the Company, have the

Pipe Plant divided up into different bargain

ing units so that Negroes lose their seniority

if they bid on some jobs even in their own

department.”

APPENDIX

ORDER OF COURT OF APPEALS DENYING REHEARING

August 7, 1981

No. 80-7107, 80-7256

JOSEPH TERRELL, Walter Dudley,

Thomas Green, Johnny Long, Albert

Mason, Marcus Oakes, Sam Walker,

on behalf of themselves and the

class they represent,

Plaint iffs-Apellants,

v .

UNITED STATES PIPE & FOUNDRY CO.,

et al., Defendants,

LOCAL 2140, UNITED STEELWORKERS UNION

LOCAL 342, INTERNATIONAL MOLDERS,

APPLIED WORKERS UNION, et al. ,

Defendants-Appellees.

JOSEPH TERRELL, JR., et al. ,

Plaint iffs-Appellants ,

v.

UNITED STATES PIPE & FOUNDRY CO.

et al. ,

Defendants,

T

LOCAL 2140, UNITED STEELWORKERS UNION,

Defendant-Appellees.

2a

Appeals from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Alabama

ON PETITION FOR REHEARING AND PETITION FOR

REHEARING EN BANC (Opinion May 14, 1081,

5 Cir., 1 98_, __ F. 2d ___).

(August 7, 1981)

PER CURIAM:

( ) The Petition for Rehearing is

DENIED and no member of this panel nor

Judge of this Administrative Unit in

regular active service having requested

that the Court be polled on rehearing en

banc (Rule 35, Federal Rules of Appellate

Procedure; Local Fifth Circuit Rule 16;

Fifth Circuit Judicial Council Resolution

of January 14, 1981), the suggestion for

Rehearing En Banc is DENIED.

ENTERED FOR THE COURT:

/s/ Joseph W. Hatchett_____

United States Circuit Judge *

*District Judge of the Norther District of Alabama, sitting by designation.

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT JUDGE

3a

DECISION OF COURT OF APPEALS,

May 14, 1981

JOSEPH TERRELL, Walter Dudley,

Thomas Green, Johnny Long, Albert

Mason, Marcus Oakes, Sam Walker,

on behalf of themselves and the

class they represent, Plaintiffs,

Apellants,

v.

UNITED STATES PIPE & FOUNDRY CO.,

et al., Defendants,

LOCAL 2140, UNITED STEELWORKERS UNION

LOCAL 342, INTERNATIONAL MOLDERS,

APPLIED WORKERS UNION, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

JOSEPH TERRELL, JR., et al. ,Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

LOCAL 2140, UNITED STEELWORKERS UNION, Defendant-Appellee.

Nos.7107, 80-7256

UNITED STATES COURT OF APEALS

Fifth Circuit

Unit B

May 14, 1981.

Rehearing and Rehearing En Banc

Denied Aug. 7, 1981.

4a

Before FAY and HATCHETT, Circuit

Judges, and Grooms*, District Judge.

HATCHETT, Circuit Judge:

This appeal stems from a class action

employment discrimination suit brought

in 1 972 under Title VII of the 1 964 Civil

Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(c),

and section 1981 of the 1 866 Civil Rights

Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1981, by black employees

at the Bessemer, Alabama plant of U.S. Pipe

and Foundry Company against their employer

1/and their union representatives. Due to

pretrial settlements by the Company and the

electrical workers union, along with the

agreement of all parties to a form of in-

* District Judge of the Northern District

of Alabama, sitting by designation.

_]_/ This is a consolidated interlocutory

appeal under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b) and

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 54(b).

5a

junctive relief and the postponement of

trial on the allocation of any back pay

liability, this litigation now focuses upon

the alleged illegality of the Bessemer

seniority system and any resulting liabil

ity on the part of five unions. These

unions include one industrial union, the

United Steelworkers of America (Steel

workers), Local 2140, and four craft

unions: the Brotherhood of Boilermakers,

Blacksmiths, Forgers, and Helpers (Boiler

makers), Local 583; the International

Association of Machinists & Aerospace

Workers (Machinists), Lodge 359; the

International Holders & Allied Workers

Union (Molders), Local 342 ; and the

Pattern Makers League of North America

(Patternmakers), Birmingham Association.

Appellants, the class of black employ

ees, challenge the decision of the trial

6a

court that all but one aspect of the Besse

mer seniority system was bona fide within

the meaning of § 703 (h) of Title VII and

thus immunized from attack as a seniority

system whose discriminatory effects were

unintended. See 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h).

In addition, appellants challenge the

court's procedural ruling that their

charges filed with the EEOC in 1 969 failed

to name as respondents the international

unions at the plant so as to permit any

Title VII liability on their part to

commence 180 days prior to the filing of

these charges. See 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)

(1). One of the appellees, the Steel

workers, cross-appeals the refusal of the

district court to excuse them from legal

responsibility for the seniority system on

the separate ground that this predominantly

black industrial union actively opposed the

7a

largely white, craft unions in the estab

lishment of a seniority system which worked

to the disproportionate disadvantage of

the Steelworkers. See 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2

(c)(3).

We agree with two of these three

challenges. We hold that the seniority

system at Bessemer was not bona fide under

§703 (h), that the Steelworkers bear no

legal responsibility for this discrimina

tory seniority system, but that the Inter

nationals were insufficiently identified by

the 1 969 EEOC charges to trigger their

Title VII liability at that time.

FACTUAL BACKGROUND

U.S. Pipe Co. has a plant in Bessemer,

Alabama which manufactures pipe for water

and sewage projects. Production and main

tenance workers at the plant have elected

as their bargaining representatives various

8a

craft unions associated with the American

Federation of Labor, as well as the

non-craft steelworkers union affili

ated with the Congress of Industrial

Organizations. The district court found

that the craft unions represent workers in

the higher-skilled, better-paying jobs from

which employees have the opportunity to

move up in the company. The Steelworkers

union represents workers in the least

desirable, "dead-end" jobs. The craft

unions are virtually all white. The

Steelworkers union is predominately black.

The district court also found that the

racial division between the unions stems

partly from the company's historical

practice of making job assignments on the

basis of race. Discriminatory job assign

ments reflected the general racism which

permeated all aspects of plant operations

prior to 1 965 , from the segregation of

9a

employee facilities to the prevention of

equal employment opportunities.

After passage of the 1964 Civil Rights

Act, a major cause of continuing inequality

was the seniority system in effect at the

Bessemer plant until 1975. The overall

seniority system was a composite of sep

arate bargaining agreements negotiated by

the company with each union. These agree

ments were similar, however, in providing

that seniority would be measured on the

basis of length of service in the applic

able seniority unit, with seniority units

generally defined by the bargaining units.

With few exceptions, an employee who

transferred to a new unit received no

credit for service to the company in his

prior unit. As recognized by the district

court, this inhibition upon transfers

disproportionately prejudiced those workers

in the predominately black Steelworkers

union who had been assigned to the least

desirable, "dead-end" jobs. The appellants

describe the discouraging effect of this

system upon black advancement at the plant

by pointing to the fate of one black em

ployee who did transfer into a craft unit,

losing twenty-six years of plant seniority,

only to then lose his job completely as

part of a reduction in plant employees

which left on the job two white workers

with just a few years of seniority in the

craft unit. See our recent decisions in

U.S. v. Gerogia Power Co., 634 F.2d 929

(5th Cir. 1981), and Swint v, Pullman-Stan

dard , 624 F.2d 525 (5th Cir. 1980), for

descriptions of the discriminatory opera

tion of seniority systems with "lock-in"

provisions such as those at the Bessemer

plant.

In the early years of plant opera

tions, various craft unions attempted with

- 1 1 a -

little success to represent employees in

negotiating a collective bargaining agree

ment. In 1939, six international unions

competed strenuously to represent some or

all of the employees at the plant. The

Steelworkers associated with the CIO,

sought to represent all production and

maintenance employees at the plant. Four

unions affiliated with the AFL sought to

represent employees based primarily upon

their craft: the Boilermakers, Machinists,

Patternmakers, and Electrical Workers. One

other AFL union, the Molders, claimed not

only those employees skilled in that craft,

but all other production and maintenance

employees except those claimed by the other

AFL unions.

Elections supervised by the NLRB

resolved this confrontation between the

newly formed CIO, with its strategy of

heterogeneous, plant-wide industrial or-

12a

ganization, and the older AFL, with its

traditional approach of organizing sep

arate, homogeneous craft unions. The

Boilermakers, Machinists, Patternmakers and

Electrical Workers prevailed over the

Steelworkers among these largely white

craft employees. The Steelworkers defeated

the Molders among the remaining, predomin

ately black group of employees. "That the

elections had racial implications cannot be

doubted," according to the district court.

Passage of the Taft-Hartley Act

enabled the Molders to return to the

Bessemer plant in 1949 to attempt "craft

severance" from the industrial union

represented by the Steelworkers. See 29

U.S.C. § 159(b)-(2). Following an NLRB

election among the all white employees with

molder skills, the Molders union was

certified as a separate craft unit.

In 1950, the unions formalized exist

13a

ing practices, without the sanction of the

NLRB, by switching representation of thir

teen positions from one unit to another.

Ten jobs given to the Boilermakers and Ma

chinists by the Steelworkers were staffed

by white workers. Three positions given to

the Steelworkers by the two craft unions

were staffed by black workers. Though it

continued to represent some white employ

ees, the Steelworkers represented an even

higher percentage of black workers as a re

sult of this "swap." The Boilermakers and

Machinists joined the Patternmakers and the

Electrical Workers in having all white mem

berships .

The bargaining units at Bessemer re

tained this racially divided structure

until the time appellants filed discrimina

tion charges with the EEOC in 1969. In the

period directly covered by this lawsuit,

U.S. Pipe negotiated collective bargaining

14a

agreements with each of the unions in 1968,

1971, and 1974. Prior to this time the

Steelworkers had repeatedly advocated

plant-wide seniority. Armed in 1968 with

the recently enacted Civil Rights Act, the

Steelworkers proposed plant-wide seniority

on the first day of negotiations. The com

pany expressed a willingness to make the

requested changes, but noted the need for

the approval of the other unions. The

craft unions strongly disapproved of any

change, and the "lock-in" provisions re

mained intact.

In 1971, the company initiated the

proposal of plant-wide seniority. The

Steelworkers met privately with the other

unions several times in an effort to gain

their agreement to such a system. Again

the craft unions prevented any change.

In 1974, the Steelworkers met with the

craft unions in advance of their separate

15a

negotiations with the company in order to

advocate plant-wide seniority. The craft

unions were intransigent. The Steelworkers

then agreed to a united union proposal to

the company for plant-wide seniority

qualified by a "unit preference" scheme

which gave unit members priority considera

tion for job vacancies. While the Steel

workers and the company continued to

express their preference for a complete

plant-wide seniority system, both agreed to

the compromise proposal.

THE DISTRICT COURT DECISION

The district court upheld the validity

of the seniority system except for the 1950

"swap" of positions between the Steelwor

kers and the Boilermakers and Machinists.

The court correctly recognized that in

order for a seniority system to be bona

fide under § 703(h) of Title VII, it

must not have been created or maintained

- 1 6 a -

with the intention to discriminate. Inter-

national Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 , 97 S . Ct. 1843, 52

L.Ed.2d 396 (1977). The d i s t r i (:t court

properly looked to the four fact:or s ex -

tracted by us from the Supreme Court ' s

opinion in Teamsters and s>et forth in James

v. Stockham Valves & Fitti.ngs Co. , 559 F.2d

310 (5th Cir . 1977), cert. denied, 434 U.S.

O u> 00 S . Ct. 767, 54 L.Ed.2d 781 ( 1978 ) ,

to assist in determining whether a particu

lar seniority system stems from nondiscrim-

inatory motivations:

( 1 ) whether the seniority system op

erates to discourage all employees equally

from transferring between seniority units;

(2) whether the seniority units are

in the same or separate bargaining units

(if the latter, whether that structure is

rational and in conformance with industry

practice);

(3) whether the seniority system had

its genesis in racial discrimination; and

(4) whether the system was negotiated

and has been maintained free from any ille

gal purpose.

James, 559 F.2d at 352.

The district court found that one of

the James factors weighed in favor of ap

pellants: The seniority system had its

genesis in racial discrimination. Speci

fically, the court found that racial con

siderations played a major role in the

election which produced the original

bargaining and seniority units, and in the

1950 "swap" of employee positions between

several units.

The district court ruled, however,

that none of the other three James factors

suggested an intent to discriminate through

the Bessemer seniority system. Regarding

the equality with which the system operated

- 17a -

upon all employees, the court noted that

the "lock-in" provisions were neutral on

their face and as applied. The court

acknowledged that "a much larger percentage

of blacks than whites would have reason to

desire transfer but for the loss of senior

ity under the rules," and that "the senior

ity system has been shown to have a dis

criminatory impact upon black employees."

The court believed these facts to be ir

relevant to the determination of any ra

cially discriminatory intent.

The court also found general rational

ity in the Bessemer bargaining structure,

and thus weighed this factor against a

finding of discriminatory purpose. Though

fraught with racial overtones, the original

configuration of the units was deemed ra

tional when viewed in light of the divi