Procunier v. Clutchette Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Procunier v. Clutchette Brief for Appellees, 1971. 27e0a393-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b5a50d6e-0a06-4ff3-a2dd-d5bf50d94e83/procunier-v-clutchette-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

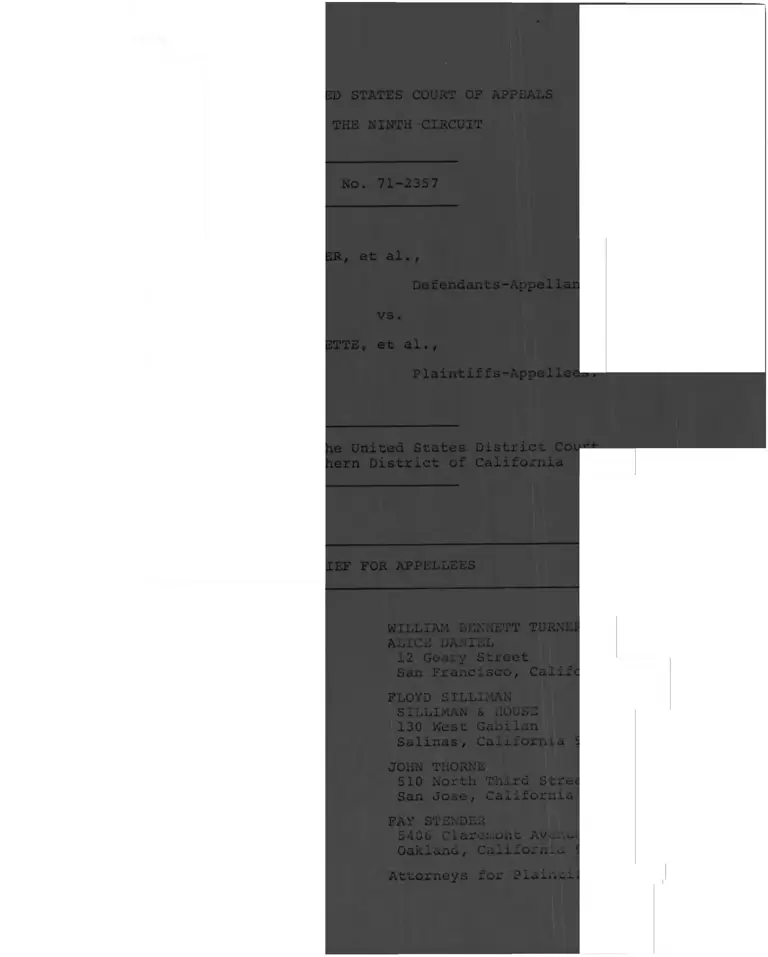

RAYMOND J. PROCUNIER, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants,

v s .

JOHN WESLEY CLUTCHETTE, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees.

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH -CIRCUIT

No. 71-2357

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

ALICE DANIEL

12 Geary Street

San Francisco, California 94108

FLOYD SILLIMAN

SILLIMAN & HOUSE

130 West Gabilan

Salinas, California 93901

JOHN THORNE

510 North Third Street

San Jose, California

FAY STENDER

5406 Claremont Avenue

Oakland, Ciixii.oriUu 9‘̂oj.o

Attorneys for Piaiacif^s-.Vvv---

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................................ iv

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E .......... 1

STATEMENT OF FACTS .................................. 3

ISSUES PRESENTED .................................... 3

ARGUMENT ............................................ 4

I. Introduction .................................. 4

II. The Consequences Of Disciplinary Proceedings

At San Quentin Are Sufficiently Serious To

Require Procedural Safeguards Against Error

Or Arbitrariness .............................. 7

(a) Sentence to Isolation .................... 8

(b) Confinement to the Adjustment

Center or Segregation .................... 8

(c) Referral to the Adult Authority.......... 10

(d) Assessment of Damages or

Forfeiture of Earnings .................. 11

(e) Referral to the District Attorney

for Prosecution.......................... 13

III. The Current Disciplinary Procedures At

San Quentin Are Inadequate To Ensure

Reliable Fact-Finding ........................ 14

1. N o t i c e .................................. 16

2. Impartial Tribunal ...................... 18

3. Counsel, Staff or Other Assistance . . . . 19

4. Confrontation and Witnesses .............. 25

Page

ii

Page

5. A Reasoned Decision Based on the

Evidence Adduced at the Hearing .......... 31

6. Record and Appeal........................ 32

IV. A Prisoner May Not Be Subjected To

Disciplinary Punishment For Conduct That

Constitutes A Crime And That May Be

Referred To The District Attorney For

Prosecution Unless He Is Provided At The

Hearing With Counsel And With The Right

To Cross-Examine And Call Witnesses.......... 38

CONCLUSION.......................................... 42

APPENDIX

ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Arciniega v. Freeman, __ U.S. ___,

10 Cr. L. Rptr. 4050 (Oct. 26, 1971)

Barber v. Page, 390 U.S. 719 (1968)

Baxstrom v. Herola, 383 U.S. 107 (1966)

Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535 (1971)

Berger v. California, 393 U.S. 314 (1969)

Berryhill v. Gibson, ___ F.Supp. ___,

40 U.S.L.W. 2147 (M.D. Ala. Sept. 3, 1971)

Bundy v. Cannon, 328 F.Supp. 165

(D. Md. 1971)

Carothers v. Follette, 314 F.Supp. 1014

(S.D. N.Y. 1970)

Carter v. McGinnis, 320 F.Supp. 1092

(W.D. N.Y. 1970)

Covington v. Harris, 419 F .2d 617

(D.C. Cir. 1969)

Dabney v. Cunningham, 317 F.Supp. 57

(E.D. Va. 1970)

Davis v. Lindsay, 321 F.Supp. 1134

(S.D. N.Y. 1970)

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968)

Ellhamer v. Wilson, 445 F.2d 856

(9th Cir. 1971)

Escalera v. New York City Housing Authority,

425 F.2d 853 (2d Cir. 1970)

Fleming v. Tate, 156 F.2d 848

(D.C. Cir. 1946)

Garrity v. New Jersey, 385 U.S. 493 (1967)

32

28

11

15.36

25,27,28

19

9,18,19,

22,30,32

9.10.18.20.36

9

4

9

9

7,8

23

15,17,18,29,31

37

40

xv

Page

In re Gary W, 5 Cal.3d 296,

___ Cal. Rptr. ___ (1971)

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970)

Gonzales v. United States, 348 U.S. 407 (1955)

Greene v. McElroy, 360 U.S. 474 (1959)

Griffin v. California, 380 U.S. 609 (1965)

11

14,15,18,

24,29,31

27

26

40

Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d 529

(5th Cir. 1968) 5,35

Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483 (1969) 22,36

Kent v. United States, 383 U.S. 541 (1966)

Klim v. Jones, 315 F.Supp. 109

(N.D. Cal. 1970)

Landman v. Peyton, 370 F.2d 135

(4th Cir. 1966)

Landman v. Royster, ___ F.Supp. ___,

U.S.L.W. 2256, No. 170-69-R

(E.D. Va. Oct. 30, 1971)

Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964)

Mathis v. United States, 391 U.S. 1 (1968)

Mayberry v. Pennsylvania, 400 U.S. 455 (1971)

In re McClain, 55 Cal.2d 78,

9 Cal. Rptr. 824 (1960)

McConnell v. Rhay, 393 U.S. 2 (1968)

Mead v. California Adult Authority,

415 F.2d 767 (9th Cir. 1969)

27

12

4

6,9,15,18,22,

29,30,32,36

40

39

19

11

23

24

v

Page

Mempa v. Rhay, 389 U.S. 128 (1967)

Meola v. Fitzpatrick, 322 F .Supp. 878

(D. Mass. 1971)

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966)

Morris v. Travisono, 310 F.Supp. 857

(D. R.I. 1970)

In re Murchison, 349 U.S. 133 (1955)

Nolan v. Scafati, 430 F .2d 548

(1st Cir. 1970), aff'g 306 F .Supp. 1

(D. Mass. 1969)

People v. Dorado, 62 Cal.2d 338,

42 Cal. Rptr. 169 (1965)

Pointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. 400 (1965)

Schuster v. Iierold, 410 F.2d 1071

(2d Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 847 (1969)

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969)

Simmons v. United States, 390 U.S. 377 (1968)

Slochower v. Board of Higher Education,

350 U.S. 551 (1956)

20,21

9

21,39

9,22,30,32

19

5,7,9,32

25,39

25

11

36

40

40

Sniadach v. Family Finance Corp.,

395 U.S. 337 (1969)

Sostre v.

(2d Cir.

McGinnis, 442 F.2d 178

1971), petition for cert, pending

Specht v. Patterson, 386 U.S. 605 (1967)

Spevack v. Klein, 385 U.S. 511 (1967)

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U.S. 199 (1960)

Townsend v. Burke, 334 U.S. 736 (1948) •

United States v. Wade, 383 U.S. 218 (1967)

12,13,15

5

11,33

40

32

11

21

Page

United States v. Weston, F.2d ,

No. 26,850 (9th Cir. Sept. 3, 1971) 11,27,37

United States ex rel Bey v. Connecticut

State Board of Parole, 443 F.2d 1079

(2d Cir. 1971) 20,21,27

United States ex rel Campbell v. Pate,

401 F .2d 55 (7th Cir. 1968) 11

United States ex rel Hancock v. Pate,

223 F.Supp. 202 (N.D. 111. 1963) 10,11

United States ex rel Marcial v. Fay,

249 F .2d 662 (2d Cir. 1957),

cert, denied, 355 U.S. 915 (1958) 36

Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241 (1949) 27

Williams v. Patterson, 389 F.2d 374

(10th Cir. 1968) 24

Williams v. Robinson, 432 F .2d 637

(D.C. Cir. 1970) 9,13,36

Willner v. Committee on Character

and Fitness, 373 U.S. 96 (1963) 26

Wisconsin v. Constantineau,

400 U.S. 433 (1971) 15

Wright v. McMann, 321 F.Supp. 127

(N.D. N.Y, 1970) 9,14,34

STATUTES, RULES AND REGULATIONS

42 U.S.C. Section 1983 1

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 2

Adult Authority Policy Statement No. 16

(June 19, 1964) 10

Vll

Page

Adult Authority Resolution No. 216

(June 5, 1964) 10

California Penal Code, Section 2924 29

Federal Bureau of Prisons,

Policy Statement No. 7400.6

(Dec. 1, 1966) 22,30 f.

San Quentin Institution Plan,

Section ID-III-02 17,26

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Hirschkop & Milleman, The Unconstitutionality

of Prison Life, 55 Va. L. Rev. 795 (1969) 30

Jacob and Sharma, Justice After Trial:

Prisoners' Need for Legal Services in

the Criminal-Correctional Process,

18 Kan. L. Rev. 493 (1970) 22

New York Atty. Gen. Op. 409/70,

Feb. 11, 1971; 8 Cr. L. Rptr. 2486 39

President's Commission on Law Enforcement

and Administration of Justice, Task

Force Report, Corrections, 13 (1967) 35

President's Commission on Law Enforcement

and Administration of Justice, Task

Force Report, Corrections, 86 (1967) 22,23,30

Tobriner, Due Process Behind Prison Walls,

The Nation, Oct. 18, 1971. 4

viii

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

No. 71-2357

RAYMOND J. PROCUNIER, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants,

v s .

JOHN WESLEY CLUTCHETTE, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is a civil action under 42 U.S.C. Section 1983,

brought by state prisoners seeking relief for deprivation of

constitutional rights secured by the due process and equal

protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

-1-

Plaintiffs are California prisoners confined at

San Quentin State Prison. Plaintiffs brought this action

on their own behalf and, pursuant to Rule 23 of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure, on behalf of all other inmates

of San Quentin affected by the disciplinary practices and

punishments challenged in this case.

An evidentiary hearing was held on December 4,

1970, where the court heard live testimony from a prison

administrator and received certain documentary evidence.

After extensive briefing, the court below rendered a decision

1/(CR 118), now reported at 328 F.Supp. 767, granting

plaintiffs (1) a declaratory judgment that the disciplinary

procedures followed at San Quentin were constitutionally

defective where certain serious punishments were imposed on

prisoners, (2) an injunction against further disciplinary

hearings under such defective procedures, (3) an injunction

expunging punishments imposed on the individual plaintiffs,

and (4) an injunction requiring the defendant prison officials

to submit a new plan for the conduct of disciplinary

proceedings in accordance with the court's decision.

Execution of the judgment was stayed pending appeal, except

for the portion requiring submission of a new disciplinary

plan. The officials sought a stay of this provision, which

1/ "CR" refers to the Clerk's Record on Appeal.

V

-2-

was denied by this Court on September 13, 1971, and rehearing

en banc was denied on October 18, 1971.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The appellant prison officials do not challenge

any of the findings of fact made by the district court. The

court's extremely thorough findings are all amply supported

2/

by the evidence.

ISSUES PRESENTED

1. Whether the consequences of disciplinary

proceedings at San Quentin are sufficiently serious to

require procedural safeguards against error or arbitrariness.

2. Whether the disciplinary fact-finding

procedures followed at San Quentin meet rudimentary standards

of due process.

3. Whether a prisoner may be subjected to

disciplinary punishment for conduct that constitutes a crime

and that may be referred to the district attorney for

prosecution unless he is provided at the hearing with counsel

and with the right to cross-examine and call witnesses.

2/ Citations to the record supporting all of the district

court's findings are contained in our post-hearing

memorandum filed December 22, 1970, at pp. 50-65 of the

Clerk's Record.

-3-

ARGUMENT

I. Introduction

In discussing the general problem in this case,

and the decision below in particular, Justice Mathew Tobriner

of the California Supreme Court stated the precise issue

before this Court: "Will inmates be accorded a due process

hearing before being subjected to disciplinary penalties

which are not only onerous in themselves but usually result

1/in an extension of the prison term?"

The issue is an important one because "under our

constitutional system, the payment which society exacts for

the transgression of the law does not include relegating the

transaressor to arbitrary and capricious action." Landman

4/v. Peyton, 370 F.2d 135, 141 (4th Cir. 1966). Indeed, the

3/ Tobriner, Due Process Behind Prison Walls, The Nation,

October 18., 1971, 367 , 369. Because of its relevance

to this case, Justice Tobriner's article is reproduced

in full as an Appendix to this brief.

£/ The Attorney General states that in reviewing prison

disciplinary proceedings the courts should only require

a "clear showing that the punishment was not imposed

arbitrarily or capriciously" (appellants' brief, pp. 11-12).

This may be true as to a particular punishment, but it

seems inappropriate for the courts to sit in review of

individual disciplinary decisions of all kinds. We submit

that the proper judicial function is to insure that

constitutionally sound procedures are followed in the administration of discipline; if the institution

"established internal procedures for reviewing its own

decisions and redressing grievances it could largely

eliminate any occasion for judicial challenges, and any

residual litigation could be readily disposed of on summary

judgment." Covington v. Harris, 419 F.2d 617, 627

(D.C. Cir. 1969) (Bazelon, J.).

-4-

courts have a

"duty to protect the prisoner from unlawful

and onerous treatment of a nature that, of

itself, adds punitive measures to those

legally meted out by the court. . . . Any

further restraints or deprivations in

excess of that inherent in the sentence

and in the normal structure of prison life

should be subject to judicial scrutiny."

Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d 529, 532, 535

(5th Cir. 1968) .

In Nolan v. Scafati, 430 F .2d 548 (1st Cir. 1970),

the court pointed out that procedural safeguards are required

whenever prison authorities may impose a serious punishment

upon a prisoner charged with violating a prison rule.

Admittedly, the question of what punishments are serious

enough to require what procedural safeguards was "largely

unexplored." 430 F.2d at 550. As the Second Circuit has

acknowledged, there is no doubt that prisoners are entitled

to due process in prison disciplinary proceedings: "The

difficult question, as always, is what process was due."

Sostre v. McGinnis, 442 F .2d 178, 196 (2d Cir. 1971),

5/

petition for cert, pending.

5/ The Court in Sostre reversed a district court decision

requiring "trial-type" procedural safeguards in "every"

prison disciplinary proceeding, and declined to state

whether prisoners were entitled to more than "adequate

notice," an opportunity to reply to the charges, and

"reasonable investigation into the relevant facts."

442 F.2d at 203. "[Djecision as to what are wholly

acceptable minimum standards [of procedural due process]

is left for another day through case-by-case development."

Id. at 206. The Court's reluctance to decree general

procedural protections was undoubtedly influenced by the

(continued on next page)

-5-

The appellee prisoners in this case do not dispute

the authority of prison officials to administer prison

discipline. The necessity for, or the appropriateness of

disciplinary controls is not an issue in this case. The

court below gave full deference to the judgment of prison

officials as to the type of prisoner conduct requiring

disciplinary controls and the kinds of disciplinary

punishments that may be imposed. The narrow issue here is

whether prisoners must be afforded procedural safeguards

essential to a fair factual determination before they can

be subjected to punishments substantially altering the nature

of their imprisonment or prolonging the term of their

incarceration.

We do not propose that a full panoply of procedural

6/

safeguards should be required in every case. The district

5/ (continued)

record -- there were no disputed facts in the punishment

of the individual prisoner and the record did not establish

systematic procedural deficiencies. Also, Sostre was not

a class action and did not involve any disciplinary

proceedings of other prisoners. See Landman v. Royster,

___ F.Supp. ___, No. 170-69-R (E.D. Va. Oct. 30, 1971).

6/ Where the prisoner pleads guilty to the charge, or there

are no disputed facts, for example, many safeguards

designed to insure accurate fact-finding are not required.

In no event do we contend that a prison disciplinary

proceeding must be conducted like a criminal trial. Thus,

we do not contend that there, should be a jury trial or

even a judge, that rules of evidence must be followed,

that guilt must be proved beyond a reasonable doubt, that

a verbatim transcript must be made and preserved, etc.

But in no case can the rudimentary safeguards of notice

and a fair hearing be dispensed with.

-6-

court followed the approach of requiring fair procedures

only where warranted by the severity of the consequences

which may flow from a finding of guilty; the possible range

of punishments must be evaluated. Cf. Duncan v. Louisiana,

391 U.S. 145, 159-160 (1968); Nolan v. Scafati, 430 F.2d 548

(1st Cir. 1970). Accordingly, the court considered (1) the

consequences of San Quentin disciplinary proceedings and

(2) the procedural safeguards appropriate to such proceedings.

II. The Consequences Of Disciplinary Proceedings At

San Quentin Are Sufficiently Serious To Require

Procedural Safeguards Against Error Or Arbitrariness.

As the district court found, the most serious

disciplinary punishments that follow a finding of guilt

of some prison infraction are (a) sentence to isolation,

(b) confinement to the Adjustment Center or segregation,

(c) referral to the Adult Authority, (d) assessment of damages

or forfeiture of earnings, and (e) referral to the District

VAttorney for prosecution.

7/ The Attorney General discusses only the disciplinary

proceedings in the case of individual plaintiff Clutchette,

stating the officials' version of the incident and

concluding that Clutchette suffered only minor changes

in his status — transfer to isolation and loss of several

privileges — as a result of the proceedings (appellants'

brief, p. 4). This overlooks not only the fact that

Clutchette's detailed affidavit (P. Exh. 1) sets forth

a very different version of what actually happened but

the crucial considerations that (1) this is a class action

involving punishments that may be imposed on all San

(continued on next page)

-7-

(a) Sentence to Isolation

Isolation is a form of solitary confinement. The

prisoner is transferred from the general prison population

to an extremely restrictive form of confinement that cuts

him off from all prison programs and other prisoners. The

harsh conditions of life in isolation are described in detail

in the district court's findings (CR 130-132).

(b) Confinement to the Adjustment Center or Segregation

Although confinement to isolation could not exceed

thirty days, confinement to the Adjustment Center or segregation

could be indefinite. Indeed, as the district court found, a

prisoner could remain there for the duration of his sentence.

Again, such confinement operates to isolate the prisoner

from all prison programs and meaningful contact with other

prisoners. The conditions of life in the Adjustment Center

or segregation are described in factual detail by the district

court (CR 132-133).

Confinements to isolation, the Adjustment Center or

segregation radically alter the nature of a man's imprisonment.

This has been recognized by federal courts throughout the

7/ (continued)

Quentin prisoners regardless of their status, and (2) the

principal factor in judging what procedural safeguards

are required is the possible range of punishments that

may be imposed, not simply the punishment imposed in a

particular case. Cf. Duncan v. Louisiana, supra, 391 U.S.

at 159-160.

-8-

country and it is now well established that disciplinary

confinement cannot be imposed without rudimentary procedural

due process. See Landman v. Royster/ ___ F.Supp. ___,

No. 170-69-R (E.D. Va. Oct. 30, 1971); Bundy v. Cannon,

328 F.Supp. 165 (D. Md. 1971); Meola v. Fitzpatrick, 322

F.Supp. 878 (D. Mass. 1971); Wright v. McMann, 321 F.Supp.

127 (N.D. N.Y. 1970); Carothers v. Follette, 314 F.Supp.

1014 (S.D. N.Y. 1970); cf. Williams v. Robinson, 432 F.2d

637 (D.C. Cir. 1970); Nolan v. Scafati, 430 F.2d 548 (1st Cir.

£/

1970); Morris v. Travisono, 310 F.Supp. 857 (D. R.I. 1970).

Moreover, the California Director's Rules state

that assignment to segregation or the Adjustment Center

signifies that an inmate is regarded as "a menace to himself

or others, or to property, or to the morale of the general

population" (D4205). Thus, such confinement will almost

inevitably result in denial of parole because the implication

of incorrigibility cannot be overlooked by the Adult Authority.

As one federal court remarked, assignment to segregation is

serious not only because of the harsh conditions but because

8/ Compare Dabney v. Cunningham, 317 F.Supp. 57 (E.D. Va.

1970)(prisoner ordered released from punitive segregation

because the officials made no showing of a factual basis

to justify such confinement); Carter v. McGinnis, 320

F.Supp. 1092, 1097 (W.D. N.Y. 1970) (segregation justified

only "if substantial evidence indicates a danger to the

security of the inmates or the facility"); Davis v. Lindsay,

321 F.Supp. 1134 (S.D. N.Y. 1970) (isolation not justified

where no proof of actual threats of either disruption or

danger to the prisoner or to other prisoners).

-9-

it deprives the inmate "of the opportunity to appear under

more favorable circumstances before the parole board for

consideration for release on parole." Carothers v. Follette,

314 F.Supp. 1014, 1027 (S.D. N.Y. 1970); see also United

States ex rel Hancock v. Pate, 223 F.Supp. 202 (N.D. 111. 1963)

(c) Referral to the Adult Authority

Resolution No. 216 (June 5, 1964) of the California

Adult Authority requires that a report of all disciplinary

actions be presented to the Adult Authority at the time it

makes its annual decision whether to set the term of a

V

prisoner's sentence and grant parole (CR 134; RT 33, 68).

A report of a serious disciplinary infraction will have an

obvious effect on the Adult Authority's determination. As

the district court found, a prisoner's behavior in prison is

a key factor in the Adult Authority's decision-making process

10/

(CR 134).

In addition, if the prisoner is found guilty of a

disciplinary offense occurring after the Adult Authority has

fixed the sentence and parole date, the offense must be

reported to the Adult Authority for immediate action (RT 33, 68

9/ "RT" refers to the Reporter's Transcript of the hearing

held on December 4, 1970.

10/ Where the Adult Authority declines to grant parole at

an annual appearance, its policy is to postpone further

appearance for at least one calendar year. Adult

Authority Policy Statement No. 16, issued June 19, 1964.

A disciplinary infraction may thus cause a prisoner to

serve at least one additional year in prison.

-10-

The disciplinary committee is authorized to recommend that

the Adult Authority rescind the parole date (CR 134-135;

RT 49). The California Supreme Court has held that a single

disciplinary offense is sufficient cause for the Adult

Authority to rescind the parole release order and reset the

prisoner's sentence at the statutory maximum. In re McClain,

55 Cal.2d 73, 9 Cal. Rptr. 824 (1960). Because such a

disciplinary finding can be used as the factual predicate

for rescinding parole and refixing the prisoner's sentence

at the maximum, thus extending the term of incarceration,

the prisoner is entitled to have the fact-finding made in a

procedurally fair and reliable way. Cf. Specht v. Patterson,

386 U.S. 605 (1967); Baxstrom v. Herold, 383 U.S. 107 (1966);

United States v. Weston, ___ F.2d ___, No. 26,850 (9th Cir.

Sept. 3, 1971); Schuster v. Herold, 410 F.2d 1071 (2d Cir.),

cert, denied, 396 U.S. 847 (1969); United States ex rel

Campbell v. Pate, 401 F.2d 55, 57 (7th Cir. 1968); United

States ex rel Hancock v. Pate, 223 F.Supp. 202 (N.D. 111.------------------------- ----

1963); In re Gary W , 5 Cal.3d 296, ___Cal. Rptr. ____ (1971).

(d) Assessment of Damages or Forfeiture of Earnings

Another of the possible sanctions that the

disciplinary committee can impose is to levy upon the earnings

11/ As this Court's recent decision in Weston indicates,

protection against factually unjustified sentence extensions

applies even in the judicial sentencing process and not

only in fact-finding proceedings. See also Townsend v.

Burke, 334 U.S. 736 (1943).

-11-

of a prisoner to pay for repair costs of any property damaged.

The committee can also recommend that a prisoner's future

wages be forfeited, regardless of whether there is any

property damage. The latter sanction is, in effect, a fine

(CR 135). The San Quentin Institution Plan permits assessments

for amounts up to $100 by a hearing officer acting alone

(ID-III-08), while the disciplinary committee is authorized

to impose assessments in excess of that amount and, in effect,

to garnishee the inmate's future earnings to cover the

assessment (Id.).

In Sniadach v. Family Finance Corp., 395 U.S. 337

(196 9) , the Supreme Court held that garnishment of wages

without prior notice and hearing violated due. process. In

his concurring opinion, Justice Harlan said that

"Due process is afforded only by the kinds

of 'notice' and 'hearing' which are aimed

at establishing the validity, or at least

the probable validity, of the underlying

claim against the alleged debtor before

he can be deprived of his property or its

unrestricted use." 395 U.S. at 343-- /

12/ In Klim v. Jones, 315 F .Supp. 109 (N.D. Cal. 1970), the

court held that the Sniadach principle applied to the

taking of property in other situations besides garnishment,

when the deprivation would cause hardship to the individual.

There could be no clearer example of the state's stripping

an individual of everything he owns than where prison

officials order the forfeiture of an indigent prisoner's

savings or earnings.

In Sniadach, the Supreme Court noted that there may be

extraordinary situations in which deprivation of property

by summary administrative action without an adequate prior

hearing may be justifiable because it Is essential to

(continued on next page)

-12-

(e) Referral to the District Attorney for Prosecution

Many disciplinary offenses also constitute crimes.

For example, inmates can be charged in,'disciplinary proceedings

with assault on another inmate, assault on a guard, possession

of a weapon, gambling, possession of drugs, escape, etc., all

of which may be prosecuted as crimes. On the basis of its

findings, the disciplinary committee may refer the case to

the district attorney for prosecution (CR 127-28, 135-37).

Disciplinary charges involving conduct that may

be prosecuted as a crime are obviously serious enough to

require procedural safeguards. Because special considerations

require separate treatment of this kind of disciplinary

offense, we discuss this issue in detail in Point IV below.

* * *

To sura up, in the five types of serious disciplinary

cases identified by the district court, the consequences to

the prisoner require rudimentary procedural safeguards against

error or arbitrariness. We do not understand the Attorney

General seriously to contend otherwise. The only substantial

12/ (continued)

protect a vital governmental interest (395 U.S. at 343).

However, even assuming arguendo that emergency conditions

might sometimes justify other types of summary action by

prison officials (e.g. isolating prisoners leading an

Insurrection), there is no conceivable situation in which

the summary forfeiture of money is essential to protect

any legitimate penal interest. Cf. WTilliams v. Robinson,

432 F .2d 637, 644 (D.C. Cir. 1970).

-13-

question on this appeal is what specific safeguards are

appropriate. We turn, then, to a consideration of the

procedures actually followed at San Quentin and the safeguards

ordered by the district court.

Ill. The Current Disciplinary Procedures At San Quentin

Are Inadequate To Ensure Reliable Fact-Finding.

Disciplinary proceedings at San Quentin are marked

by many of the trappings of a judicial proceeding, without

any of its procedural safeguards. The Institution Plan

speaks in terms of "disciplinary hearing courts," of

"charges," "pleas" and "adjudication" but mandates none of

the procedures generally regarded as essential to a fair

13/and reliable fact-finding.

In Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970), the

Supreme Court held that rudimentary procedural safeguards

are constitutionally required whenever the state proposes

to act in a way that will adversely affect an important

individual interest. The Supreme Court stated that a welfare

recipient threatened with loss of his benefits had sufficient

interest, as against the government's interest in summary

adjudication, to be entitled to a hearing before termination

13/ As one federal court remarked in striking down similar

New York procedures, disciplinary courts are "practically

judicial"; disciplinary officials "really assume the

function of a Judge." Wright v. McMann, 321 F .Supp. 127,

141, 143 (N.D. N.Y. 1970).

-14-

with (1) adequate prior notice; (2) an impartial tribunal;

(3) the right to representation or assistance; (4) the right

to confrontation or cross-examination of adverse witnesses

and to call favorable witnesses; and (5) a reasoned decision

14/based solely on evidence adduced at the hearing. The

Court emphasized that these were no more than "minimum

procedural safeguards" for a pre-termination hearing; because

a full statutory "fair hearing" would be held later on, the

safeguards enumerated by the Court were only those "demanded

15/

by rudimentary due process." 397 U.S. at 266-67.

14/ See also Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535 (1971) (hearing

required for suspension of driver's license); Wisconsin

v. Constantineau, 400 U.S. 433 (1971) (hearing required

before habitual drunkard could be publicly exposed);

Sniadach v. Family Finance Corp., 395 U.S. 337 (1969)

(hearing required before wage garnishment); Escalera v.

New York City Housing Authority, 425 F .2d 853 (2d Cir.

1970) (procedural rights of public housing tenants

threatened with eviction).

15/ The Attorney General misreads Goldberg when he suggests

that fair procedures were required there only because

the withdrawal of government benefits affected the

recipient's very means to live (appellants' brief, p. 7).

The Court in Goldberg made plain that procedural due

process applies to denial of a variety of government

benefits such as tax exemptions, public employment, etc.

397 U.S. at 262. The Court pointed out that some kinds

of benefits may be terminated without a pre-termination

hearing, and the issue in Goldberg was whether the

possible loss to the individual required a due process

hearing prior to termination. 397 U.S. at 260, 264. Because

of threatened irreparable injury to the individual, a

pre-termination hearing was required even though a full

and fair hearing was mandated in any event for final

termination. 397 U.S. at 260, n.7. Similarly, the

threatened injury to a prisoner charged with a disciplinary

(continued on next page)

-15-

The court below found that similar safeguards were

appropriate to prison fact-finding hearings where very serious

punishments could be imposed. Accord, Landman v. Royster,

___ F.Supp. ___, 40 U.S.L.W. 2256, No. 170-69-R (E.D. Va.

Oct. 30 , 1971). We-will consider separately the components

of procedural due process required by the district court, and

discuss why they are necessary and appropriate in this case.

1. Notice

The only notice given San Quentin inmates accused

of a disciplinary offense does not fairly inform them of the

specific misconduct with which they are charged and thus does

not permit the preparation of a defense. The accused may be

given a written "Notice of Complaint," but ail it includes is

the number and title of the rule the prisoner is charged with

having violated; it does not describe the actual misconduct

charged or the particular facts to be proved. Thus, it may

only state "D1201, Inmate Behavior" or "D1202, Disobeying

16/Order," without explication. There need be no hrnt of

15/ (continued)

offense requires a prior hearing; a post-punishment

hearing would provide no protection at all against

undeserved punishments like isolation, segregation

and postponement of parole.

16/ A prison administrator testified that the Notice states

"exactly what the charge is" CRT 19). But, as the

Notice in evidence (.Court's Exh. 2) shows, he referred

only to the "number of the director's rule and then

what the title is" (JRT 20), not the facts of the alleged

offense. The court below properly found that the only

notice given was the uninformative number and general

title (CR 126).

-16

the act or behavior considered to violate some broad general

17/

rule (CR 126).

Notice of the charge is so fundamental a part of

due process that discussion of it seems superfluous. Any

hearing conducted without prior notice to the person whose

interest may be adversely affected would be a sham. See

Escalera v. New York City Housing Authority, 425 F .2d 853

(2d Cir. 1970). We would not expect the prison officials

to quarrel with this notion.

There is no reason why the Notice of Complaint

given to the prisoner could not contain the same information

as the CDC Form 115, which the prisoner is not permitted to

see. Since preparation of Form 115 is the first step in

serious cases and is prepared before the Notice of Complaint

is issued, incorporating the Form 115 information in the

Notice of Complaint (or simply giving the prisoner a copy of

the Form 115) would not require any additional work by staff

18/

members. Written notice of the charge has been required

17/ Yet prison administrators do know how to demand specificity.

Institution Plan Section ID-III-02 instructs staff members

that every CDC Form 115 disciplinary report (which is

not shown to the inmate) must meet these requirements:

"Complete, Concise, Clear, and Correct, as well as

detailing What, When, Where, Who and Why."

18/ It should be noted that the record before this Court does

not establish, that eyen the Inadequate notice required

by the San Quentin Institution Plan Is actually given in

every case. Plaintiff Clutchette's affidavit states that

he received no written notice at all (P. Exh. 1).

-17-

not only by the court below in this case, but also by the

well-reasoned decision in Landman v. Royster, ___ F.Supp. ___,

40 U.S.L.W. 2256, No. 170-69-R (E.D. Va. Oct. 30, 1971), and

adequate notice has been required by all the authorities

cited in text at note 8 , supra.

2. Impartial Tribunal

The San Quentin disciplinary procedures do not

preclude the officer accusing the prisoner from sitting on

the adjudicatory tribunal (CR 127). Although a prison

administrator acknowledged that this was undesirable, it in

fact occurred in plaintiff Clutchette's case, when a

lieutenant whose report was part of the evidence also sat

on the disciplinary committee and when Associate Warden Park,

whose report was also part of the evidence, was consulted as

to the proper disposition and then "reviewed" and approved

the disposition (RT 12, 30, 39-40, 68).

The requirement of an impartial tribunal is

fundamental to American notions of fair play. A hearing

before the inmate's accuser is tantamount to no hearing at

all. See Landman v. Royster, ___ F.Supp. __, 4 0 U.S.L.W.

2256, No. 170-69-R (E.D. Va. Oct. 30, 1971); Bundy v. Cannon,

328 F.Supp. 165 CD. Md. 1971); cf. Goldberg v. Kelly, 397

U.S. 254 C1970); Escalera v. New York City Housing Authority,

425 F .2d 853 C2d Cir. 1970); Carothers v. Follette, 314 F.Supp.

-18-

1014 (S.D. N.Y. 1970) ("relatively objective tribunal").

Yet procedures at San Quentin deny the inmate a finding by

an impartial tribunal. We do not here contend that hearing

officers from outside the institution must be provided, as

in Bundy v. Cannon, supra. We simply say that the same man

cannot be permitted both to accuse and to judge.

3. Counsel, Staff Or Other Assistance

The prisoner's right to be heard by the disciplinary

committee is often meaningless unless he has the assistance

of some other person who can aid him in marshalling the facts

or arguing in mitigation. Prison inmates come from the least

educated segment of our society and are ill-equipped to make

a convincing presentation of their version of the facts.

This is particularly true if the prisoner is inarticulate,

frightened or inexpert in English.

Moreover, prisoners accused of a disciplinary

offense may be placed in isolation for the entire period

between the time of the alleged offense and the hearing,

19/

19/ Even where the decisionmaker is a judge who is presumably

able to put aside extraneous influences, the Supreme

Court has held that participation in the accusatory

process disables the judge from being "wholly

disinterested" in the accused’s case. See Mayberry v.

Pennsylvania, 400 U.S. 455, ___ (1971); In re Murchison,

349 U.S. 133, 137 (1955); cf. Berryhill v. Gibson, ___

F.Supp. ___, 40 U.S.L.W. 2147 (M.D~ Ala. Sept. 3, 1971)

(3-judge court). There is no reason to believe that

prison officials are more able than judges to resist

tendencies to prejudge the facts.

-19-

thus rendering it impossible to prepare any defense without

the assistance of someone free to carry on an investigation

2 0/

(CR 126). This "counsel" can interview the inmate to

learn his version of the facts, attempt to corroborate it

through questioning others, and then assist the inmate at

the hearing.

Further, counsel could perform an important

(although non-adversarial) function by analyzing and

organizing relevant information bearing on the occurrence

or non-occurrence of the facts in issue, and by presenting

"mitigating circumstances and hidden significances not

revealed or immediately obvious on the face" of the

disciplinary report. Cf. United States ex rel Bey v.

Connecticut State Board of Parole, 443 F.2d 1079, 1087

(2d Cir. 1971); Mempa v. Rhay, 389 U.S. 128 (1967). Counsel

could also suggest that the facts do not justify imposing

the most severe punishments in the committee's arsenal of

authorized sanctions, although they might justify a lesser

21/

punishment. Bey, supra, at 1088.

20/ A prison administrator testified that no prison rule

would prohibit an inmate from presenting written

statements of witnesses to the alleged infraction but,

assuming this is true, there is no way that an inmate

confined to isolation could, without assistance, obtain

such statements.

21/ As the court noted in Carothers v. Folletta, 314 F .Supp.

1014 CS.D. N.Y. 1970), a disciplinary proceeding conducted

with regard for due process "may' then well result in a

much lighter sentence."

-20-

The disciplinary committee could of course limit

the function of counsel so as not to disrupt or prolong

proceedings. Id. at 1089. By his presence alone, counsel

can increase the fairness and thus improve the reliability

of the findings without transforming the hearing into a

full-scale adversary proceeding. Cf. United States v. Wade,

383 U.S. 218, 238 (1967); Memoa v. Rhay, supra.

San Quentin prisoners accused of disciplinary

offenses, no matter how serious, are not permitted to have

counsel of any kind (CR 128). The court below required the

prison officials to furnish counsel or "counsel substitute"

depending on the seriousness of the disciplinary charge.

Where the inmate is charged with conduct that would constitute

a crime in thq free world, the court below held that Miranda

v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966), requires that interrogation

in disciplinary proceedings cannot take place unless the

prisoner is furnished with state-appointed counsel. This

point is considered separately and in detail under Point IV

below.

In cases where prisoners are charged with conduct

which would not be criminal in the free world, but wnich may

lead to serious disciplinary punishment, the court below

22/

held that "counsel substitute" may be adequate. See also

22/ Plaintiff Clutchette, of course, had an attorney who

requested to be present at the disciplinary hearing but

was refused. But it will be the rare prisoner who has

retained counsel, and the possibility of providing some

lay advisor must be explored.

-21-

Landman v. Royster, ___ F.Supp. ___, 40 U.S.L.W. 2256,

No. 170-69-R (E.D. Va. Oct. 30, 1971). Thus, it would be

helpful to have the assistance of a staff member, a law

student or oven a fellow inmate to assist in preparing a

defense. Assistance and representation by staff members at

23/

disciplinary hearings is provided for in federal prisons,

24/ 25/

in Rhode Island and in Maryland. Other sources of

26/

non-attorney assistance might include law students. Legal

assistance by fellow inmates is another possibility; this

has been sanctioned by the Supreme Court in Johnson v. Avery,

393 U.S. 483 (1969), authorized in Maryland, Bundy v. Cannon,

328 F.Supp. 165 (D. Md. 1971), and ordered in Virginia,

Landman v. Royster, supra.

Counsel in serious disciplinary cases is not

inconsistent with correctional goals. The President's

Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice

thoroughly considered this problem and recommended that where

disciplinary charges may lead to an increase in the actual

length of imprisonment,

23/ See Federal Bureau of Prisons, Policy Statement No. 7400.6

(Dec. 1, 1966).

24/ See Morris v. Travisono, 310 F.Supp. 857 (D. R.I. 1970).

25/ See Bundy v. Cannon, 328 F.Supp. 165 CD. Md. 1971).

26/ Many law schools now have prison legal assistance programs

that take law students into the prisons. See generally

Jacob and Sharma, Justice After Trial: prisoners1 Need

for Legal Services in the Criminal-Correctional Process,

18 Kan. L. Rev. 493 U970).

-22-

"the prisoner should be given reasonable

notice of the charges, full opportunity

to present evidence and to confront and

cross-examine opposing witnesses, and the

right to representation by counsel. Task

Force Report: Corrections, 86 (.1967)

(emphasis added]-!

Counsel of some kind is clearly required for San

Quentin disciplinary hearings. Because the right to counsel

is central to "the very integrity of the fact-finding process,"

the Supreme Court's decisions establishing that right in the

criminal context have been applied retroactively. See, e.g.

McConnell v. Rhay, 393 U.S. 2 (1968). The Attorney General

in this case does not urge that representation in San Quentin

proceedings would not improve the reliability of the fact

finding, would be inappropriate to the nature of the proceeding

27/

or would unduly burden the administrative staff. The

Attorney General does rely on decisions holding that there

is no right to counsel in parole revocation cases, e.g.

Ellhamer v. Wilson, 445 F.2d 856 (9th Cir. 1971), and argues

that little due process is required to cancel an inmate's

27/ The prison officials offered no evidence that any of

the procedural safeguards ordered by the district court:

would be unfeasible to implement. The record shows that

the disciplinary committee hears an average of only 7

cases a week (CR 127). The record does not show how many

of these involve guilty pleas or how many inyolve disputed

issues of fact. Providing fairer procedures for the

small number of serious cases where there are factual

disputes would not seem to present difficult administrative

problems. It Is open to the officials to establish

different procedures for different categories_of cases

in their disciplinary plan submitted to the district court

(CR 149-150).

-23-

"privilege, conditioned on good behavior, of being confined

under less onerous conditions" (appellants' brief, pp. 5, 6).

This contention must be rejected. The cases denying

procedural rights in parole revocation rely on the theory

that a parolee is in custody and it is a matter of "grace"

that he is permitted to serve part of his sentence outside

of prison. See, e.g. Mead v. California Adult Authority,

415 F .2d 767 (9th Cir. 1969), relying on Williams v. Patterson,

389 F.2d 374 (10th Cir. 1968). The reasoning in such cases

is that the normal status of the convicted person is in prison

and that since parole release is a matter of grace, it can be

revoked without ceremony. But this reasoning has no application

here. The normal status of a prisoner is not in isolation

or segregation. In California, as elsewhere, the normal

status of a prisoner is in the general inmate population where

he can participate in rehabilitative programs. He loses this

normal status only if he is found guilty of a disciplinary

infraction. Accordingly, the parole revocation decisions

2_8/

certainly do not govern here, and the Court should follow

the approach of Goldberg and other cases requiring some form

of representation in serious fact-finding hearings. 397 U.S.

at 270.

28/ A further distinction from parole revocation Is that the

parole decisionmakers are high-ranking authorities

appointed by the Goyernor to perform the sensitive task

of making parole decisions in light of all the relevant

information. But disciplinary decisions are made by prison

officers whose qualifications are unknown and who have no

special distinction making them the safe repositories of

arbitrary power.

24-

Confrontation and Witnesses4 .

At San Quentin, the "evidence" in a disciplinary

hearing consists of written reports. The.complaining guard

is not even required to be present at the hearing, much less

testify or be subject to cross-examination (CR 128). Indeed,

no witnesses at all are present, and the accused prisoner is

not entitled to call any witnesses on his own behalf. This

is true even where a prisoner is accused of a felony offense

29/

and exercises his right to remain silent (RT 115).

The right to confront one's accusers is essential

where the facts are in dispute. Cf. Berger v. California,

393 U.S. 314 (1969); Pointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. 400 (1965).

Indeed, the right has been characterized by the Supreme Court

as so essential to the "integrity of the fact-finding process

as to require retroactive application in the criminal context

Berger v. California, supra, 393 U.S. at 315. Of course the

right is not limited to criminal cases but applies wherever

governmental action seriously injures an individual and the

reasonableness of the action depends on fact findings. See

29/ Where a possible felony is involved, the accused inmate

is warned that anything he says to the disciplinary

committee "can and will" be used against him in court

(Court's Exh. 4). Such warnings are required by the

California Supreme Court's decision in People v. Dorado,

62 Cal.2d 338, 42 Cal. Rptr. 169 (1965). However, if

the prisoner chooses to exercise his right to remain

silent, he is disabled from presenting any defense

whatever to the disciplinary charge (RT 115). In such

a case, the right to appear and be heard is worthless;

the right to call witnesses is indispensable.

-25-

Willner v. Committee on Character and Fitness, 373 U.S. 96

-------------- - 3 0 /

(1963); Greene v. McElroy, 360 U.S. 474 (1959).

Face-to-face with the individual who must suffer

the consequences if he has exaggerated, lied or omitted

modifying details, a prison guard (like any other man) will

be more careful about the facts than when he is dictating

an impersonal written report. The instruction contained in

the San Quentin Institution Plan directing guards to be

"concise" in preparing Form 115 reports, while commendable

in some respects, can encourage a tendency to oversimplify

and omit details whose unperceived significance might prove

crucial when seen from a more detached point of view.

Prison guards are no less fallible than other men,

and it is possible that their perceptions may be faulty or

their judgments influenced by personal friction with the

accused inmate. Their reports are not entitled to an

"irrebuttable presumption of accuracy" and it is important

30/ "Certain principles have remained relatively immutable

in our jurisprudence. One of these is that where

governmental action seriously injures an individual,

and the reasonableness of the action depends on fact

findings, the evidence used to prove the Government's

case must be disclosed to the individual so that he has

an opportunity to show that it is untrue. While this

is important in the case of documentary evidence, it is

even more important where the evidence consists of the

testimony of individuals whose memory might be faulty

or who, in fact, might be perjurers or persons motivated

by malice, vindictiveness, intolerance, prejudice, or

jealousy. We have formalized these protections in the

requirements of confrontation and cross-exaa?.ination."

Greene v. McElroy, 360 U.S. at 496.

-26-

that they be subjected to "examination, criticism and

refutation." Cf. Kent v. United States, 383 U.S. 541, 551

(1966); United States v. Weston, ___ F.2d ___, No. 26,850

(9th Cir. Sept. 3, 1971); United States ex rel Bey v.

Connecticut State Board of Parole, 443 F .2d 1079, 1087

31/

(2d Cir. 1971).

Further, disciplinary charges are often originated

not by guards but by other prisoners, wno may complain about

an assault, or gambling or some other infraction not witnessed

by a guard. Under San Quentin practice, with reliance solely

on written reports, the disciplinary committee does not even

have the opportunity to judge the credibility of the

complaining witness, whether a guard or a prisoner. But

"one of the important objects of the right of confrontation

was to guarantee that the fact finder had an adequate

opportunity to assess the credibility of witnesses." See

31/ The Attorney General relies on Williams v. New York,

337 U.S. 241 (1949), for the proposition that confrontation

and cross-examination are not required (appellants' brief,

p. 10, n.7). Williams held only that use of a probation

report as an aid to the sentencing judge does not deny

due process. Compare this Court's recent decision in

United States v. Weston, supra. Whatever the result in

judicial sentencing, where the judge has wide discretion

in making an appropriate disposition after guilt has been^

found, the fact-finding process leading to the determination

of guilt cannot .be held reliable without the rudimentary

safeguarcjs of confrontation and cross-examination. See

Gonzales v. United States, 348 U.S. 407, 412, n.4 (1955),

distinguishing Williams on the ground that it did not

"involve individualized fact finding and classification,

but. . .the exercise of judicial discretion in the

imposition of sentence."

-27-

Berger v. California, 393 U.S. 314, 315 (1969); Barber v.

Page, 390 U.S. 719, 725 (1968). Fact-finding simply cannot

be reliable without confrontation.

It would not be necessary to accord prison inmates

the same right of cross-examination that is given criminal

defendants. It would be a considerable improvement over

current practice simply to require that the complaining guard

or prisoner be present to recount his version of the incident

in the accused's presence. With the aid of his "counsel,"

the inmate could then attempt to elicit clarification and

32/

additional detail concerning any disputed matters. This

would produce more precise information about what actually

occurred. For example, an inmate charged with disobeying

an order might be able to show that it had been unclear, or

misunderstood. Away from the pressure of the situation in

which the alleged violation occurred, a fair-minded guard

may be expected to acknowledge the possibility of his own

occasional error. Under current practice he is never given

this opportunity. Indeed, the procedures give him^a

conclusive presumption of veracity and accuracy.

32/ Of course, if the prisoner does not dispute any facts

or pleads guilty, there is probably no occasion for

cross-examination.

33/ While the disciplinary committee will probably resolve

most guard-prisoner credibility issues in favor of the

guard, current practice avoids credibility issues

altogether by conclusively presuming the correctness

of the cold words in the Form 115.

-28-

Cross-examination of adverse witnesses may, of

course, be restricted "to relevant matters, to preserve

decorum, and to limit repetition," but where the disciplinary

case turns on an issue of fact the right to confront and

cross-examine is essential. Landman v. Royster, ___ F.Supp.

___, 40 U.S.L.W. 2256 , No. 170-6 9-R (E.D. Va. Oct. 30 , 1971)

(slip op. 66); see also Escalera v. New York City Housing

Authority, 425 F .2d 853, 862 (2d Cir. 1970).

The accused inmate must also be allowed to call

34/

witnesses on his own behalf. A "hearing" cannot be

conducted on written reports, which most prisoners are

ill-equipped to prepare. And "particularly where credibility

and veracity are at issue. . .written submissions are a wholly

insufficient basis for decision." Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S.

254, 269 (1970); Landman v. Royster, supra. Even if the

accused's own version of the facts is true, he is likely to

be disbelieved because of his strong interest in the outcome

of the case; and he cannot count on a guard's admission of

error. Unless the inmate is permitted to call witnesses, the

only evidence before the committee is the "prosecution"

version of the case. Such a one-sided presentation of

34/ Under the statutory good time credit scheme applicable

to those sentenced prior to January 1, 1948, California

prisoners facing the loss of credit as the result of

disciplinary charges were entitled to present evidence

and call witnesses on their own behalf. Penal Code 2924.

Although the provision is largely obsolete today, it

stands as evidence that the right to call witnesses was

not regarded as incompatible with the orderly

administration of prison discipline.

-29-

evidence would not be tolerated in any other kind of fact

finding proceeding. There is no reason to tolerate it here.

In federal prisons, accused prisoners facing a serious

disciplinary charge may call witnesses if it appears that

the facts are reasonably in dispute. See Federal Bureau

of Prisons, Policy Statement No. 7400.6 (Dec. 1, 1966).

Prisoners in Rhode Island are also permitted to call witnesses.

See Morris v. Travisono, 310 F.Supp. 857 (D. R.I. 1970).

Prisoners in Maryland may call and cross-examine witnesses

in serious cases. See Bundy v. Cannon, 328 F.Supp. 165, 176

(D. Md. 1971). And, as noted above, the President's Crime

Commission advocates a right to confront and call witnesses.

Task Force Report, Corrections, at 86. Mr. James V. Bennett,

former Director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons, has testified

that such protections are "an essential ingredient to good

discipline." Hirschkop & Milleman, The Unconstitutionality

of Prison Life, 55 Va. L. Rev. 795, 831, 834 (1969). The

court in Landman v. Royster, ___ F.Supp. ___, 40 U.S.L.W.

2256, No. 170-69-R (E.D. Va. Oct. 30, 1971), ordered essentially

the same procedural safeguards as the district court in this

case, finding that they are "necessary and will not unduly

impede legitimate prison functions." See also Bundy v. Cannon,

328 F.Supp. 165, 173 (D. Md. 1971)(prison officials promulgated

new procedures they deemed "practicable").

-30-

5. A Reasoned Decision Based On The

Evidence Adduced At The Hearing

At San Quentin, the disciplinary committee is not

prohibited from considering evidence outside the record

(CR 128). A prison administrator testified that he felt

free to take into account ex parte information casually

passed along by prison inmates (RT 25). Moreover, the

disciplinary committee is not told what standard of proof

is required to find guilt. The San Quentin Disciplinary

Plan does not specify any standard of proof (CR 129).

Permitting the prisoner to cross-examine adverse

witnesses and to call favorable ones is futile if the

decisionmaker is not prohibited from considering evidence

outside the record. We do not contend that the hearsay rule

applies in prison disciplinary proceedings. We do contend,

however, that disciplinary proceedings must respect the tenet

of due process that decision be based solely on evidence

adduced at the hearing. See Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254,

271 (1970); Escalera v. New York City Housing Authority, 425

F .2d 853, 862-63 (2d Cir. 1970). In other words, decision

must be based on evidence "which the prisoner has the

opportunity to refute. . . . To permit punishment to be

imposed for reasons not presented and aired would invite

arbitrariness and nullify the right to notice and hearing. . .

The practice of going outside the record in search of bases

-31-

for punishment must cease." Landman v. Royster, ___ F .Supp.

___, 40 U.S.L.W. 2256, No. ,170-69-R (E.D. Va. Oct. 30, 1971)

(slip op. 66).

Moreover, the omission of any standard of proof

from the San Quentin Institution Plan leaves the disciplinary

committee free to base its decision on no evidence at all.

Cf. Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U.S. 199 (1960); Arciniega v.

Freeman, U.S. , 10 Cr. L. Rptr. 4050 (Oct. 26, 1971)

------- 35/

("satisfactory evidence" requirement for parole revocation).

In these circumstances, it was clearly proper for the court

below to impose the Goldberg requirement that the committee

state the reasons for its decision and the evidence relied

36/

upon.

6. Record And Appeal

The only record of a San Quentin disciplinary

proceeding consists of the notations made on the face of the

35/ Even the district court in Nolan v. Scafati, 306 F.Supp.

1 (D. Mass. 1969), which was reversed and remanded for

plenary consideration of the prisoner's procedural

rights (430 F.2d 548 (1st Cir. 1970)), assumed that the

decisionmaker must base the decision on "substantial

evidence." Requiring that the finding rest on substantial

evidence reminds the disciplinary committee of its duty

fairly to weigh any opposing evidence, and should

contribute to more reliable findings. See also Bundy

v. Cannon, 328 F.Supp. 165 (D. Md. 1971); Morris v.

Travisono, 310 F.Supp. 857 (D. R.I. 1970).

36/ This is also required in federal prisons, see Federal

Bureau of Prisons, Policy Statement No. 7400.6 (Dec. 1,

1966) , and by the decisions in Landman v. Royster, supra,

and Bundy v. Cannon, supra..

-32-

Form 115 (CR 129). This includes simply the title of the

rule violated, the name of the complaining officer, the

inmate's plea, the committee's finding and the disposition

ordered.

The "record" is forwarded to the Associate Warden

for his review and approval. A prison administrator testified

that if the prisoner were dissatisfied with the committee's

action, he could write to the Associate Warden, Custody

(who had already approved the action) requesting further

consideration of the case. There is no requirement that

prisoners be informed of this possibility of "appeal" (CR 129).

Adequate findings and a record are essential "to

make meaningful any appeal that is allowed" to a higher

authority within the administrative process. Cf. Specht v.

Patterson, 386 U.S. 605, 610 (1967). But the Form 115 does

not even have a space provided for briefly recording the

evidence tending either to support or oppose the committee's

findings. The prisoner's version of the facts or explanation

of mitigating circumstances is not recorded at all, even

though in most cases the record that goes to the Adult

Authority will consist solely of the Form 115.

The provision for automatic review by the Associate

Warden is thus an illusory safeguard. The record submitted

to him is entirely inadequate to permit meaningful

consideration of the correctness of the committee's findings.

-33-

He must assume the accuracy of the committee's findings of

fact. The only "review" possible is of the appropriateness

of the disposition, based on the assumption that the finding

37/

of guilt is correct.

The district court did not require appellate review

of disciplinary proceedings as a matter of constitutional law.

It simply required that, as long as review is provided for

some prisoners, all must be notified of this possibility.

The Attorney General has advanced no argument here to justify

providing fair procedures for only some prisoners, and the

court below properly required uniformity of treatment.

* * *

In summary, the procedural safeguards ordered by

the court below are both essential to reliable fact-finding

and appropriate to disciplinary hearings at San Quentin.

Moreover, they not only protect the prisoner's interest in

37/ Even this limited review has no guarantee of impartiality.

Review of the committee's action in plaintiff Clutchette's

case was made by Warden Park, who had been consulted by

the committee before it reached its decision, and whose

report on the infraction was part of the evidence in

the case.

The right to fair review by a disinterested official may

result in a quite different disposition. As Judge Foley

noted in Wright v. McMann, 321 F .Supp. 127, 145 (N.D. N.Y.

1970), "procedural safeguards with meaningful review and

formal right to appeal in this instance might have averted

or corrected this improper punishment."

-34-

avoiding a longer prison term and abnormally severe conditions

of confinement but they also advance the correctional system's

interest in rehabilitation.

The prison officials presumably do not claim the

right to impose serious punishments arbitrarily. Certainly

no legitimate penal interest is served by punishing an inmate

for charges of which he is innocent. To the contrary,

undeserved punishment is likely to cause resentment and

mistrust of any form of authority. Sporadic and uneven

enforcement of prison discipline "is more likely to breed

contempt for the law than respect for it and obedience to it"

and arbitrary treatment discourages prisoners from cooperating

in their rehabilitation. See Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d 539,

535 (5th Cir. 1968).

The unreliable fact-finding procedures challenged

38/

here, which are so antithetical to rehabilitation, are

not required by the need for prison security. If emergencies

arise, they may be dealt with by emergency measures; but

summary methods which would be justifiable only in an

38/ The President's Crime Commission states that "the

necessity of procedural safeguards should not be viewed

as antithetical to the treatment concerns of corrections."

Task Force Report, Corrections, 13 (.1967) . The Commission

emphasizes that prison procedures should be fair in fact

and perceived as fair by the prisoners; it says: "A

person who receives what he considers unfair treatment

from correctional authorities is likely to become a

difficult subject for reformation." Id. at 83.

-35-

emergency will not suffice for the daily running of the

prison. Cf. Williams v. Robinson, 432 F .2d 637, 644

3 9 / ~

(D.C. Cir. 1970).

We do not contend that the officials may not

isolate or imp'ose controls on a prisoner who is in fact

disruptive. There is no urgency, however, about placing an

inmate in punitive isolation as opposed to merely separating

him from the prison population. Such an extreme punishment

should await a reliable fact-finding proceeding. See Landman

v. Royster, F.Supp. ___, 40 U.S.L.W. 2256, No. 170-69-R

(E.D. Va. Oct. 30, 1971).

Even if summary isolation can be justified, referral

to the Adult Authority of findings of disciplinary infractions

is not justified by any need for urgent action. Since the

prisoner's sentence was based on a conviction originally made

by a judge or jury with all the procedural safeguards of a

judicial proceeding, and since the Adult Authority cannot

39/ The officials here have shown no strong governmental

interest in summary adjudication. Indeed, they introduced

no evidence whatever to show that fairer and more careful

procedures could not easily be implemented. It is now

clear that considerations of administrative convenience,

however legitimate, do not justify summary treatment

resulting in infringement of constitutional rights. See

Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 531 (1971); Shapiro v. Thompson,

394 U.S. 618 0-969); Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483

(1969); United States ex rel Marcial v. Fay, 249 F.2d

662 (2d Cir. 19 57) , cert, denied, 355 U.S. 915 (195 8);

Carothers v. Follette, 314 F.Supp. 1014 (S.D. N.Y. 1970).

-36-

make de novo findings of fact in disciplinary matters,

findings of infractions that may be used to extend the period

of imprisonment must be made with scrupulous regard for

40/

procedural fairness.

No doubt a disciplinary proceeding in which the

prisoner is accorded basic procedural safeguards might take

longer than the current method. However, such a change would

enhance, rather than detract from, its value as a part of the

total correctional process. The goal of our penal system is

rehabilitation, and as the court observed in Fleming v. Tate,

156 F.2d 848, 850 (D.C. Cir. 1946),

"Certainly no circumstance could further that

purpose to a greater extent than a firm belief

on the part of such offenders in the impartial,

unhurried, objective and thorough processes

of the machinery of the law. And hardly any

circumstances could with greater effect impede

progress toward the desired end than a belief

on their part that the machinery of the law is

arbitrary, technical, too busy, or impervious

to facts."

40/ See authorities cited in text at note 11, supra. As

this Court added in United States v. Weston, ___ F.2d

, No. 26,850 C9th Cir. Sept. 3, 1971), "a rational

penal system must have some concern for the probable

accuracy of the informational inputs in the sentencing

process."

-37-

IV. A Prisoner May Not Be Subjected To Disciplinary

Punishment For Conduct That Constitutes A Crime

And That May Be Referred To The District Attorney

For Prosecution Unless He Is Provided At The

Hearing With Counsel And With The Right To

Cross-Examine And Call Witnesses.

When the subject of the disciplinary proceeding is

in-prison conduct that constitutes a crime, the accused

prisoner is brought before the disciplinary committee and

advised of his constitutional rights to remain silent and to

have an attorney present during interrogation. He is also

specifically advised that anything he says "can and will" be

used against him in a court of law (CR 127) . However, if the

prisoner then requests an attorney, he is told he cannot see

one until the District Attorney interviews him. If he

exercises his right to remain silent, the committee nevertheless

proceeds to adjudicate the disciplinary infraction, relying

solely on any written reports filed against him (CR 127-128;

135-136). The district court found that "the trap is

unavoidable" — the prisoner, warned that anything he says

may be used against him in a criminal prosecution,

"definitionally prejudices himself" by either (1) remaining

silent, sacrificing any defense to the disciplinary charge

(especially a mitigating circumstances defense) and thus

incurring severe punishment, or (2) speaking in his own

defense and risking self-incrimination in a later criminal

prosecution (CR 137).

The court below invalidated this procedure, pointing

out that it presents more serious constitutional infirmities

-38-

I *

than those in Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966). The

Attorney General has not contested this part of the court's

decision; the district court was plainly correct.

The Supreme Court in Miranda declared that when

an individual is taken into custody and "is subjected to

questioning, the privilege against self-incrimination is

jeopardized." 384 U.S. at 478. It is well-established that

in-prison questioning of a suspect is custodial interrogation

under Miranda. See Mathis v. United States, 391 U.S. 1

(1968). Indeed, San Quentin officials give the Miranda

warnings to accused prisoners in response to the California

Supreme Court's decision in People v. Dorado, 62 Cal.2d 338,

42 Cal. Rptr. 169 (1965).

The Supreme Court made plain in Mathis, supra,

that it makes no difference that the interrogation is not

for the purpose of gathering evidence for criminal prosecution

or that the person being questioned is in custody for an

entirely separate offense:

"These differences are too minor and shadowy

to justify a departure from the well-

considered conclusions of Miranda with

reference to warnings to be given to a

person held in custody. . . . There is no

substance to such a distinction, and in

effect it goes against the whole purpose

of the Miranda decision which was designed

to give meaningful protection to Fifth

Amendment rights." 391 U.S. at 4.— '

41/ The Attorney General of New York has rendered an opinion

to this effect, expressly concluding that the Miranda_

warnings must be given in prison disciplinary proceedings.

See Atty. Gen. Op. 409/70, Feb. 11, 1971, reported in

8 Cr. L. Rptr. 2486.

-39-

It is clear, therefore, that the prison officials

are required to give the Miranda warnings and advise the

accused prisoner of his right to remain silent and to have

an attorney. If the prisoner knowingly waives such rights

and chooses to defend himself, the disciplinary committee

may proceed with the questioning at the hearing. But where

the prisoner does not waive such righis and elects to exercise

the privilege against self-incrimination, the committee

cannot proceed to adjudicate the offense and impose a

disciplinary punishment with the prisoner "stripped of any

possible means of defense" (CR 138). This is because it is

impermissible to impose any penalty for exercising the right

to remain silent or any sanction whatever that makes assertion

of the Fifth Amendment privilege "costly." See Spevack v.

Klein, 385 U.S. 511, 515 (1967); Garrity v. New Jersey, 385

U.S. 493 (1967); Griffin v. California, 380 U.S. 609, 614

(1965); Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964); Slochower v.

Board of Higher Education, 350 U.S. 551 (1956); cf. Simmons

v. United States, 390 U.S. 377, 394 (1968).

Thus, unless the prisoner waives his Miranda rights,

the disciplinary committee cannot, using its current procedures,

impose punishment. It may be, however, that the prison

authorities consider disciplinary controls essential and an

offense too serious to permit a suspected disruptive prisoner

to return to the general prison population. In other words,

they may take the position that security requires imposition

-40-

of discipline without awaiting the outcome of criminal

prosecution. If so, they can conduct a disciplinary

proceeding, but only if — as the court below held — the

accused is furnished with counsel and given the right to

cross-examine and call witnesses (CR 138-39). Counsel must

be furnished not only for all the reasons discussed at

pp. 19-24, supra, but because Miranda requires it. Cross-

examination and the right to call witnesses are required not

only for all the reasons discussed at pp.. 25-30 , supra, but

because if the accused exercises his privilege to remain

silent he would be defenseless without these rights. The

district court's decision on this point, not challenged by

the Attorney General, must be affirmed.

r*

-41-

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, the judgment of the

district court should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

___________

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

ALICE DANIEL

12 Geary Street

San Francisco, California 94108

FLOYD SILLIMAN

Silliman & House

130 West Gabilan

Salinas, California 93901

JOHN THORNE

510 North Third Street

San Jose, California

FAY STENDER

5406 Claremont Avenue

Oakland, California 94618

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

I

-42-

APPENDIX

VENGEANCE OR HOPE?

MATHEW O. T0B3INER

Mr. Tobriner is an associate justice o f the Supreme Court