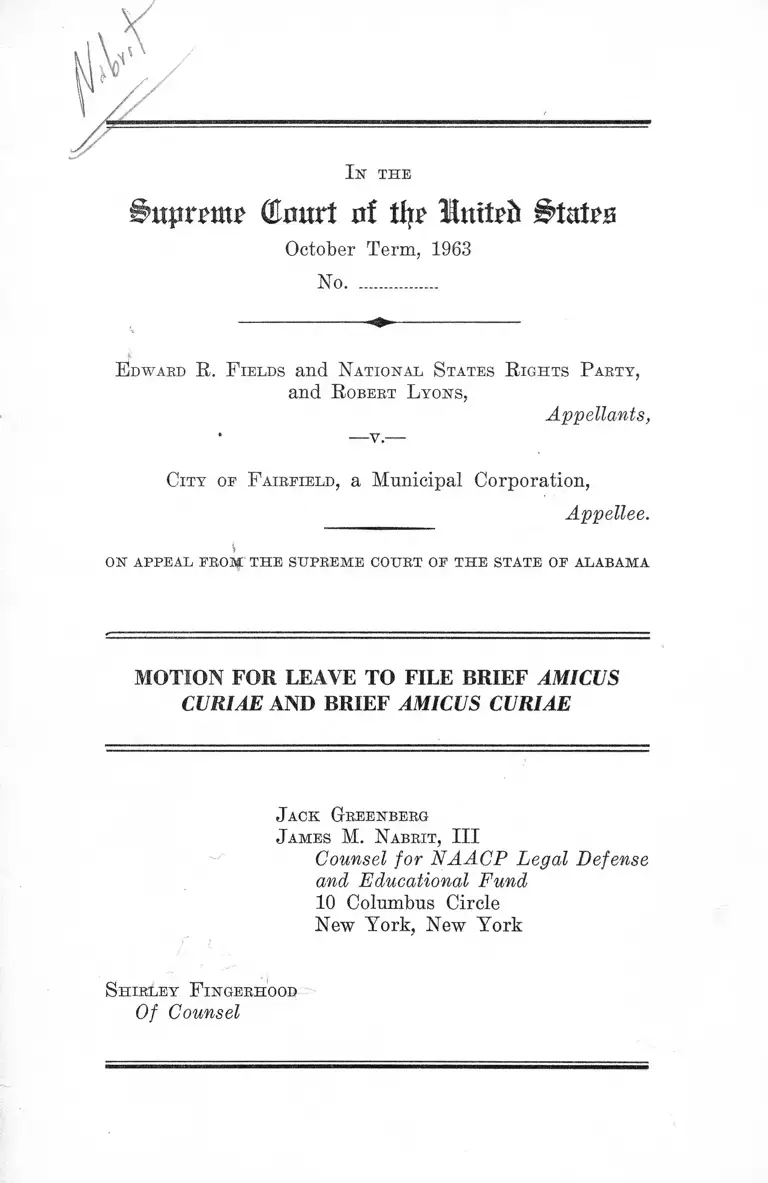

Fields v. City of Fairfield Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Fields v. City of Fairfield Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1963. be432a9c-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b5bd8f79-333e-4ba7-8f6d-4774dfcb7939/fields-v-city-of-fairfield-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 16, 2026.

Copied!

Ihtpreme (Eourt of tffp BUUb

October Term, 1963

No..................

E dward E. F ields and N ational S tates E ights P arty ,

and E obert L yons,

Appellants,

Cit y of F airfield , a Municipal Corporation,

Appellee.

s

ON APPEAL FRO M T H E SU PRE M E COURT OF T H E STATE OF ALABAM A

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS

CURIAE AND BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit , III

Counsel for NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

S h irley F ingerhood

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae............. 1

Brief Amicus Curiae .......................................................... 5

Conclusion ..................................... ............................................... 12

Table of Cases

Bantam Books v. Sullivan, 372 U. S. 5 8 ........................ 6

Bates v. City of Little Bock, 361 U. S. 516..... ............... 6

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 .......................... ....... 6

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 .......................... 6

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 ............... ..... 3, 5

Ex Parte Fisk, 113 U. S. 713............................................ 10

Ex Parte Rowland, 104 U. S. 604 .................................... 10

Ex Parte Sawyer, 124 U. S. 200 ...................................... 10

Fields v. City of Fairfield, 273 Ala. 588, 143 So. 2d 177.. 4

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157.................................. 2

George v. Clemmons, 373 U. S. 241 ................................ 7, 8

In Be Green, 369 U. S. 689 ................................................ 8

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 6 1 .................................... 7, 8

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 .............................. ........... 6

Marcus v. Property Search Warrant, 367 U. S. 717..... 5

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 .................................. 6

NAACP v. Alabama, 360 U. S. 240 ........ .......................... 3

PAGE

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415.................................... 6

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697 ................................. 6

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 .............................. 6

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 ................. 3

Rosenberg v. United States, 346 U. S. 273 ..................... 10

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147 ............. ......................... 6

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 _____ _________ ____ 6

Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313.......................................... 6

Talley v. California, 362 U. S. 6 0 .................................... 5

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154 ................................ 3

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 ................................ 5

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516.................................... 6, 7, 9

United Gas, Coke and Chemical Workers of America

v. Wisconsin Employment Relations Board, 340

U. S. 383 ........................................................................... 8, 9

United States v. Shipp, 203 U. S. 563 .......................... 10,11

United States v. United Mine Workers of America, 330

U. S. 258 ............................................................7, 8, 9,10,11

Worden v. Searls, 121 U. S. 1 4 ........................................ 10

Other Authorities

Note, The Void for Vagueness Doctrine in the Supreme

Court, 109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 6 7 ........................................ 6

ii

I s THE

Bnpvmz Court of the Imteh States

October Term, 1963

No..................

E dward E. F ields and N ational S tates E ights P arty ,

and E obert L yons,

Appellants,

City of F airfield , a Municipal Corporation,

Appellee.

ON APPEAL FROM T H E SU PRE M E COURT OF T H E STATE OF ALABAM A

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF

AMICUS CURIAE

Petitioner, NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., respectfully moves this Court for permission

to file the attached brief amicus curiae and as reasons

therefor sets forth the following:

1. Petitioner is a New York corporation organized for

the purpose, among other things, of securing equality be

fore the law, without regard to race, for all citizens. In

this connection members of petitioner’s staff often have

represented Negro citizens before various courts, including

this Court, on claims that they have been denied equal

protection of the laws, due process of law, and other rights

secured by the constitution and laws of the United States.

Moreover, members of petitioner’s staff have represented

citizens who have been denied First Amendment rights

while attempting to secure equal treatment within society

and before the law without regard to race.

2

2. It goes without saying that petitioner abhors the

anti-Negro, anti-Semitic views and political program of

Edward R. Fields and the National States Rights Party.

They have opposed petitioner’s program vigorously.1 They

embrace a policy of racism diametrically opposed to the

fundamental principles upon which our nation was founded.

At the same time petitioner is compelled to recognize that

if this particular conviction against Fields is upheld, a

precedent in the Alabama courts will be affirmed, and sub

stance will be given to similar proceedings in other courts

directed against proponents of equality, which will deny

rights secured by the Fourteenth Amendment and seriously

impede the movement for equal rights now current in the

nation. While petitioner believes that all lawful measures

should be taken against illegal conduct by Fields and his

party, it does not believe that the state may proceed against

him in a way which denies First Amendment rights. Diffi

cult as it may be to take this position in this case,1 2 3 peti

tioner believes that First Amendment rights must be vig

orously guarded if the proponents of equality are to tri

umph. Injunctions cannot restrain political expression, and

contempt penalties for the violation of such injunctions

must not be sustained or the right to petition for equal

protection of the laws will be violated.

3. Advocates of racial equality have been the victims

of innumerable legal proceedings of various sorts through

out the South. See, e.g. Garner v. Louisiana/ Peterson v.

1 See New York Times, September 24, 1963, p. 1, col. 1.

2 But see Gellhorn, American Bights 50 (1960): “ [Cjonstitu-

tional issues have to be fought out on their own merits, rather

than on the merits of the individual in connection with whom the

issue may have arisen.”

3 368 U. S. 157.

3

City of Greenville,* Edwards v. South Carolina/ Taylor

v. Louisiana/ NAACP v. Alabama.4 5 6 7 8 All of these efforts

to use the criminal law, the common law and various other

powers of government to stifle free expression on behalf

of racial equality have failed. Now it is claimed that by

the device of imposing an injunction, First Amendment

expression on behalf of racial equality can be stifled, at least

until ultimate adjudication of the underlying issues in the

case, which may be a matter of years. See NAACP v.

Alabama. s Pursuant to this new tactic various govern

mental bodies have obtained injunctions against demonstra

tions on behalf of racial equality throughout the South.9

Indeed, within the State of Alabama, a conviction for

contempt for having violated a temporary restraining order

obtained without notice recently was entered against Wyatt

T. Walker, Dr. Martin Luther King and others in the City

4 373 U. S. 244.

5 372 U. S. 229.

6 370 U. S. 154.

7 360 U. S. 240.

8 360 U. S. 240.

9 Alabama v. Robinson, Circuit Court of Etowah County, Ala

bama, amended temporary injunction issued June 18, 1963; Ala

bama ex rel. Flowers v. Zellner, Circuit Court of DeKalb County,

Alabama, May 7, 1963; C.O.R.E. v. Douglas, 318 F. 2d 95, in

junction vacated 5th Circuit, May 13, 1963; Kelley v. Page, M. D.

Ga., July 19, 1963, injunction vacated, 5th Cir., July 24, 1963;

City of Jackson v. Salter, Chancery Court of the First Judicial

District of Hinds County, Mississippi, No. 63,429, June 6, 1963;

Porzio v. Williams, Superior Court of Chatham County, Georgia,

June 19, 1963; City of Clarksdale v. Aaron Henry et al., Coahoma

County Court, Mississippi, July, 1963; City Council of Charles

ton v. NAACP et al., Court of Common Pleas, Charleston, South

Carolina, temporary restraining order entered July 26, 1963; Mes-

selman Theatres v. McLean et al., Superior Court of Cumberland

County, North Carolina, temporary restraining order entered May

29, 1963; Knight v. NAACP et al., County Court, Pine Bluff,

Arkansas, No. 34,703, temporary restraining order entered August

13,1963.

4

of Birmingham, on the authority of Fields v. City of Fair-

field, 273 Ala. 588, 143 So. 2d 177.10

4. Because of this dimension of the case, which may not

adequately appear in argument on behalf of Dr. Fields and

his party, and because of the involvement of the NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund in behalf of the de

fendants in most of the cases cited above, we respectfully

submit that the views of the Fund on this issue may be of

interest to the Court.

5. Petitioner has requested permission of appellants and

appellee to file this brief amicus curiae; these requests have

been denied.

W hekefoee petition er p rays that the attached b rie f

amicus curiae be perm itted to be filed w ith this court.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

Counsel for NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

S h irley F ingerhood

Of Counsel

10p ity of Birmingham v. Walker et al., Circuit Court, Tenth

Judicial Circuit, Alabama, contempt conviction decreed April 26,

1963; brief for respondent City of Birmingham, Supreme Court

of Alabama, pp. 21-24.

I n the

§>uprmr Court of % Imtrft

October Term, 1963

No..................

E dward E . F ields and N ational S tates E ights P arty ,

and R obert L yons ,

Appellants,

City oe F a i r f i e l d , a Municipal Corporation,

Appellee.

ON APPEAL FROM T H E SU PRE M E COURT OF T H E STATE OF ALABAM A

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

The interest of this amicus is set forth in the above

motion for leave to file brief amicus curiae.

Amicus adopts the statement of facts as set forth in

appellants’ brief.

1. Upholding appellants’ conviction, the Alabama Su

preme Court ruled in effect that punishment may be im

posed for violation of a judicial order restraining the

distribution of pamphlets and the holding of a political

meeting. But punishment cannot be inflicted for the peace

ful exercise of First Amendment rights. Edwards v. South

Carolina, 372 U. S. 229; Talley v. California, 362 U. S. 60;

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1. It may, of course, be

imposed for certain activities excluded from First Amend

ment protection although they are closely connected with

speech. But a state is not free to adopt procedures “with

out regard to the possible consequences for constitutionally

protected speech,” Marcus v. Property Search Warrant,

367 U. S. 717, 731, and for that reason the power to impose

6

a prior restraint upon expression has unquestionably been

denied. Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697; cf. Lovell v.

Griffin, 303 IT. S. 444; Schneider v. State, 308 IT. S. 147;

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 304-307; Niemot.ko

v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268; Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313.

Indeed, the reason that vague statutes are unconstitutional

when applied to First Amendment rights is that their very

existence has an inhibitory effect upon expression and,

therefore, in that sense they constitute a prior restraint.

See NAACP v. Button, 371 IT. S. 415; cf. Bantam Books v.

Sullivan, 372 U. S. 58. Note, The Void for Vagueness Doc

trine in the Supreme Court, 109 IT. Pa. L. Rev. 67.

The question on this appeal is whether a state may impose

a criminal penalty for the exercise of free speech by adopt

ing a rule of procedure prohibiting collateral attacks on

injunctions restraining First Amendment rights. If, as the

court below ruled, Fields was required to obey the injunc

tion of the Fairfield Circuit Court until its validity had been

adjudicated or incur certain punishment, then by utilizing

the proscribed device of enjoining expression, a state may

achieve a result otherwise prohibited—criminal punishment

of peaceful expression.

We believe that this Court has made clear its disapproval

of rules so destructive of constitutional rights. Manifestly

no court has the power to achieve by injunction a result

which government may not constitutionally effect. Compare

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 IT. S. 1, with Buchanan v. Warley,

245 IT. S. 60; and compare NAACP v. Alabama, 357 IT. 8.

449 with Bates v. City of Little Rock, 361 IT. S. 516. “ It is

not of moment that the State has here acted solely through

its judicial branch, for whether legislative or judicial, it is

still the application of state power which we are asked to

scrutinize.” NAACP v. Alabama, supra, at p. 462.

In Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. 8. 516, the Court stated at

p .540:

7

If the exercise of the rights of free speech cannot

be made a crime, we do not think this can be accom

plished by the device of requiring previous registration

as a condition of exercising them and making such a

condition the foundation for restraining in advance

their exercise and for imposing a penalty for violating

such a restraining order. If one vrho solicits support

for the cause of labor may be required to register as

a condition to the exercise of his right to make a public

speech, so may he who seeks to rally support for any

social, business, religious or political cause. We think

a requirement that one must register before he under

takes to make a public speech to enlist support for a

lawful movement is quite incompatible with the re

quirements of the First Amendment.

2. As authority for its position that the question of con

stitutionality of a judicial order may not be adjudicated on

an appeal from a judgment of conviction for contempt, the

court below relied on United States v. United Mine Workers

of America, 330 U. S. 258. In that case a majority of the

Court held that the injunction was! lawful/because they

found that the Norris-LaGuardia Act did not apply. (In

this case, amicus contends that the injunction is unlawful.)

The opinion of the Court and that of Mr. Justice Frank

furter concurring in the judgment also stated that the

validity of a criminal conviction for contempt would not

be reversed on the ground that the underlying order was

invalid.

However, in Mine Workers the effect on constitutional

rights of denying collateral attack was not in issue. Where

constitutional rights are affected, the Supreme Court of

the United States has consistently reversed criminal con

tempt convictions for disobedience of judicial orders.

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61; George v. Clemmons,

373 U. S. 241; Thomas v. Collins, supra.

ft**

8

In Johnson v. Virginia, and George v. Clemmons, the

orders underlying the contempt convictions were held to

violate the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. In George v. Clemmons, 373 U. S. 241, the

State argued unsuccessfully that even if the state court’s

order of segregated seating in the courtroom was illegal,

Negroes had no right to violate the order, but instead were

required to obey it pending a challenge of its legality in

other proceedings. U. S. Law Week, April 30, 1963,

p. 3355. In United Gas, Coke and Chemical Workers

of America v. Wisconsin Employment Relations Board, 340

U. S. 383, the injunction which the union disobeyed violated

constitutional prohibition against state interference in a

field pre-empted by federal legislation. Cf. In Re Green,

369 U. S. 689.

Moreover, the opinion of the court in Mine Workers

noted that “a different result would follow were the ques-

LF tion of jurisdiction frivolous and not substantial.” 330

U. S. at p. 293. That exception was described by Mr. Justice

A \.fs -.Frankfurter as follows:

[A]n obvious limitation upon a court cannot be cir

cumvented by a frivolous inquiry into the existence of

a power that has unquestionably been withheld. . . . In

such a case, a judge would not be acting as a court.

He would be a pretender to, not a wielder of, judicial

power. 330 U. S. at p. 310.

As Fields had a clear First Amendment right here, the

court’s inquiry into its power to issue a temporary restrain

ing order was frivolous.1 And we do not believe that the

1 As the inquiry into the court’s power was ex parte, Fields had

no opportunity to contest the jurisdiction of the court prior to

his trial for contempt. If collateral attack on the order is not

permitted at the trial for contempt, the conviction may violate

due process requirements. In Re Green, supra, where the Supreme

Court reversed a conviction for contempt of an ex parte temporary

restraining order as a denial of due process.

9

difficulty inherent in determining the issue of the validity

of the injunction is relevant to the existence of a duty to

obey pending that determination, as was suggested in 'Mine

Workers. (In Thomas v. Collins, supra and United Gas,

Coke and Chemical Workers v. Wisconsin Employment

Relations Board, supra, the issues were extremely com

plicated.) Rather, the sole question is whether the order

is required to be reversed because of constitutional in

firmity.

Constitutional rights are “present rights. . . . The basic

guarantees of our constitution are warrants for the here

and now, and unless there is an overwhelmingly compelling

reason they are to be promptly fulfilled.” Watson v. City

of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 at p. 533. There is no overwhelm

ingly compelling reason which warrants delay of the exer

cise of the First Amendment rights pending judicial con

sideration and reversal of an unconstitutional order. The

reason suggested in Mine Workers, respect for judicial

process, has “ a seductive attractiveness,” Murphy, J. dis

senting in U. 8. v. United Mine Workers of America, supra,

at p. 340, but is not compelling in the sensitive area of

First and Fourteenth Amendment rights on close examina

tion.

If the injunction were valid and the judgment of contempt

were properly imposed the judiciary would be vindicated

and appellant would be required to serve his sentence. But,

it is argued that even an invalid temporary restraining

order must be obeyed to vindicate respect for the judiciary.

If the prior restraint is. as we submit, unconstitutional,

then the courts are not denied respect by reversing a con

tempt conviction any more than when any other conviction

is reversed, as for a. faulty indictment or charge to the jury

or as when a statute or proceeding under the common law

is held to violate similar rights. The fact is that the ulti-

10

mate and underlying respect for the law demands, under

our system, that all men, including those sitting as judges,

act within the limitations of the Constitution of the United

States.

Prior to Mine Workers this Court apparently believed

that respect for the courts would be maintained if it fol

lowed the rule that when a court acted without power its

orders were regarded as a nullity and no penalty could be

imposed for disregard of them. In Ex Parte Sawyer, 124

U. S. 200, a contempt conviction for disobeying a restrain

ing order granted in direct contravention of a federal

statute prohibiting injunctions of state court proceedings

was reversed. The Court held that the statute’s restriction

nullified the injunction.

In Ex Parte Fisk, 113 U. S. 713, a contempt conviction

was reversed because the order which was disobeyed was

in a category which the court could not issue. No penalty

for disobedience was imposed in Ex Parte Rowland, 104

U. S. 604, because the writ of mandamus exceeded the legal

limitation permissible for such orders.

It was only where the court had the power to make the

order that a contempt conviction was upheld. In United

States v. Shipp, 203 U. S. 563, the case which was relied

upon in the Mine Workers opinions,2 the Court had the

power to issue the stay order which was violated. It so

stated at p. 573. There was no doubt then that the Supreme

Court has the power to issue a stay pending its determina

tion of the merits of an appeal. There is no doubt today.

“How could there be doubt about a power that has existed

uninterruptedly ever since Congress gave it by the Act of

September 24, 1789? Section 14 of the Judiciary Act, 1

Stat. 73, 81-82.” Frankfurter, J., dissenting in Rosenberg

v. United States, 346 U. S. 273, 302 fn. 1.

2 Worden v. S earls, 121 U. S. 14, also cited in Mine Workers,

was not a criminal contempt case.

11

Iii Shipp, Mr. Justice Holmes held that the question of

whether or not there was a Federal question raised on

an appeal from a denial of habeas corpus was irrelevant to

the question of the Court’s authority to stay execution pend

ing its decision to hear the appeal. The Court’s authority

to issue stays pending appeal might indeed have been used

erroneously where the appeal was without merit. However,

a decision dismissing the appeal would east no doubt upon

the authority of the Court to issue the stay or vitiate the

authority of the Court to issue stay orders in the future.

Unlike Shipp, in this appeal the constitutional question

is directed to the authority of the Court to issue the in

junction underlying the contempt conviction. If, as we con

tend, the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution prohibited the issuance of the injunction, the in

junction was a nullity and of no effect and the State may

not impose punishment for its violation.

Those pressing for Fourteenth Amendment rights may

well risk punishment if they mistake the area of consti

tutional protection; they should not incur punishment when

their rights are vindicated.

If the decision of the lower courts in this case is not

reversed, we will see the serious consequences of which

Mr. Justice Rutledge warned in his dissent in Mine

W orkers:

Thus, the constitutional rights of free speech and free

assembly could be brought to naught and censorship

established widely over those areas merely by applying

such a rule to every case presenting a substantial

question concerning the exercise of those rights. This

Court has refused to countenance a view so destruc

tive of the most fundamental liberties. Thomas v.

Collins, 323 U. S. 516, 89 L. ed. 430, 65 S. Ct. 315.

12

These and other constitutional rights would be nulli

fied by the force of invalid orders issued in flat viola

tion of the constitutional provisions securing them, and

void for that reason. 330 U. S. at p. 352.

CONCLUSION

If all that were involved here were the merits of Fields’s

obnoxious notions, the result would be simple. But prin

ciples of constitutional law which bear upon his contempt

conviction transcend the particulars of his case. As shown

in the above Motion for leave to file this brief amicus curiae,

far more common than an injunctive suit against a Fields

are the proceedings being conducted throughout the South

against proponents of equality. See cases cited supra,

p. 3. The freedom of speech which petitioners invoke

in those cases is the same which is at issue here. When

Fields breaks the law he should be prosecuted promptly

and vigorously. But the great protections of the Consti

tution which redound to all should not be scrapped in the

course of keeping his conduct within lawful bounds.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

Counsel for NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New’ York

S hirley F ingerhood

Of Counsel

38