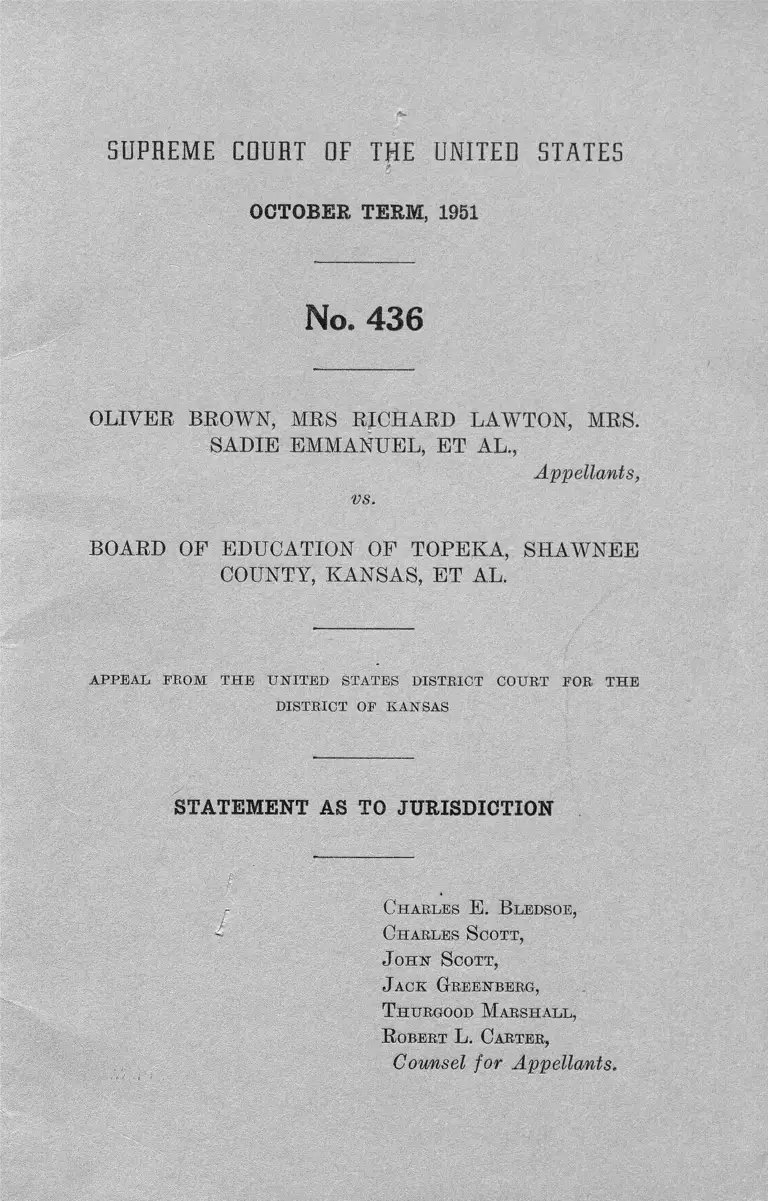

Brown v Board of Education of Topeka Statement as to Jurisdiction

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1951

35 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v Board of Education of Topeka Statement as to Jurisdiction, 1951. 4cae19ee-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b5f23342-8ef9-4009-8c0d-51f36dbc9c26/brown-v-board-of-education-of-topeka-statement-as-to-jurisdiction. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

S U P R E M E E D U R T OF T H E U N I T E D S T A T E S

OCTOBER TERM, 1951

No. 436

OLIVER BROWN, MRS RICHARD LAWTON, MRS.

SADIE EMMANUEL, ET AL.,

vs.

Appellants,

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA, SHAWNEE

COUNTY, KANSAS, ET AL.

A PPE A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR TH E

DISTRICT OF KANSAS

STATEMENT AS TO JURISDICTION

Charles E. B ledsoe,

Charles Scott,

John Scott,

Jagk Greenberg,

T hurgood M arshall,

R obert L. Carter,

Counsel for Appellants.

INDEX

Subject I ndex

Page

Statement as to jurisdiction........................................ 1

Opinion below ........................................................ 1

Jurisdiction............................................................... 2

Questions presented.............................................. 2

Statutes involved .................................................. 2

Statement ............................................................... 2

The questions are substantial.............................. 5

Appendix “ A ” —Opinion, findings of fact, conclu

sions of law and decree of the United States Dis

trict Court .................................................................. 17

Appendix “ B ” —Applicable statutes......................... 26

T able of Cases Cited

Briggs v. Elliott, No. 273, October Term, 1951 (now

pending) ..................................................................... 5

Dominion Hotel v. Arizona, 294 U.S. 265................... 12

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78.................................... 5

HirabayasM v. U.S., 320 U.S. 81................................... 12

Korematsu v. U.S., 323 U.S. 214................................... 12

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. (2d) 649................. 10

McLaurin v. Board of Regents, 339 U.S. 637............. 2, 5

Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633.............................. 12

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537................................ 5

Rescue Army v. Municipal Court, 331 U.S. 549......... 10

Rice v. Arnold, 340 U.S. 848 (decided October 17,

1950) ........................................ 11

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 .................................... 12

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535............................... 12

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629..................................... 5

Takahashi v. Fish, and Game Com,mission, 334 U.S.

410 ............................................................................... 12

Wilson v. Board of Supervisors, 94 L. ed. 200......... 2

—8589

11 IN D E X

Statutes Cited

Page

“ American Divided” , Rose: Minority Group Rela

tions in the United States, (1948)........................... 12

“ An American Dilemma” Gunnar Mydral, Hayes,

New York, 1944 .......................................................... 8

Constitution of the United States, 14th Amendment. 12,15

“ Development of Attitudes Towards Negroes,” Eu

gene Horowitz in Readings in Social Psychology,

Holt, 1947, pp. 561, 517.............................................. 7

General Statutes of Kansas, 1949:

Section 12-713 ........................................................ 14

Section 21-2424 ...................................................... 14

Section 21-2461 ............. 14

Section 21-2462 ...................................................... 14

Section 21-2463 ...................................................... 14

Chapter 7-1724 ...................................................... 2,3,12

Section 76-307 ........................................................ 13

“ Harlan Fiske Stone—Teacher, Scholar and Dean,”

Young B. Smith in Columbia Law Review, Vol.

XLYI, Sept. 1946 ...................................................... 7

House Joint Resolution No. 1 of the House of Repre

sentatives of the State of Kansas (L. 1949, Ch.

289, p. 253) .................................................................. 14

“ Main types and causes of discrimination” (memo

randum submitted by the Secretary-General,

United Nations— Commission on Human Rights,

Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination

and Protection of Minorities, Lake Success, New

York, p. 50) ................................................................ 6

“ Man’s Most Dangerous Myth—The Black & White

of Rejections of Military Service,” Montague-5

(1944) at 29...................................................... ‘ . . . . 13

“ New Trends in the Investigation of Prejudice,”

Annals o f ' the American Academy of Political

Science, 1946, p. 244.................................................... 6

“ Post War Prospects of Equitable Educational Op

portunities for Negroes” in Race Relations and.

Human Relations, Fisk Univ. 1945, p. 86............... 6

Page

“ Psychological Effects'of Enforced Segregation, A

Survey of Social Science Opinion, ’ ’ Max Deutscher

and Isidor Chein, Journal of Psychology, 1948;

26; 259-287 ...................................... 6

“ Pace Differences’ ’ , Klineberg, 343 (1935)............... 13

“ Theory and Problems of Social,Psychology’ ’, New

York, David Krech and Richard S. Crutchfield,

McGraw-Hill-1948, Chapters X II and X I I I .......... 6

United States Code, Title 28:

Section 1253 ............................................................ 2

Section 2101(b) ...................................................... 2

Section 2281 ............................................................ 3

Section 2284 .............................................. 3

IN D E X 111

OCTOBER TERM, 1951

S U P R E M E C O U R T OF T H E U N I T E D S T A T E S

No. 436

OLIVER BROWN, MRS RICHARD LAWTON, MRS.

SADIE EMMANUEL, ET AL.,

vs.

Appellants,

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA, SHAWNEE

COUNTY, KANSAS, ET AL.

APPEAL FHOM T H E U N ITED STATES D ISTRICT COURT FOR TH E

DISTRICT OF KANSAS

STATEMENT AS TO JURISDICTION

In compliance with Rule 12 of the Rules of the Supreme

Court of the United States, as amended, plaintiffs-appel-

lants submit herewith their statement particularly disclos

ing the basis upon which the Supreme Court has jurisdiction

on appeal to review the judgment of the district court

entered in. this cause.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the United States District Court for the

District of Kansas is not yet reported. A copy of the

2

opinion, findings of fact, conclusions of law and final decree

are attached hereto as Appendix A.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the district court was entered on August

3, 1951. A petition for appeal is presented to the District

Court herewith, to wit, on September 28, 1951. The juris

diction of the Supreme Court to review this decision by

direct appeal is conferred by Title 28, United States Code,

Sections 1253 and 2101(b). The following decisions sustain

the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court to review the judg

ment on direct appeal in this case: McLaurin v. Board of

Regents, 339 U. S. 637; Wilson v. Board of Supervisors,

— U. S. 94 L. ed. (Ad. Op.) 200.

Questions Presented.

1. Whether Chapter 72-1724 of the General Statutes of

Kansas, 1949, is unconstitutional in that it gives to defend-

ants-appellees the power to organize and maintain separate

public elementary schools for the education of white and

colored children in the City of Topeka, Kansas.

2. Whether after having shown that the maintenance of

racially segregated elementary schools in Topeka, pursuant

to Chapter 72-1724 of the General Statutes of Kansas, 1949,

is harmful and deprives them of the benefits they would

receive under a racially integrated school system, plaintiffs-

appellants are necessarily entitled to the relief prayed for

in their complaint.

Statutes Involved

Chapter 72-1724 of the General Statutes of Kansas, 1949,

as set forth in Appendix B attached hereto.

Statement

Appellants are here seeking to enjoin appellees from

maintaining separate public elementary schools for Negro

3

and white pupils in the City of Topeka, pursuant to au

thority conferred by Chapter 72-1724 of the General Stat

utes of Kansas, 1949. The asserted right to injunctive

relief is based upon the unconstitutionality of Chapter 72-

1724, in that the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution strips the state of power to either au

thorize or require the maintenance of racially segregated

public schools. A district court of three judges was con

vened, as provided in Title 28, United States Code, Sections

2281 and 2284, and on June 25, 26, 1951 a hearing on the

merits took place.

The evidence there presented disclosed that the City of

Topeka is divided into eighteen territories for school pur

poses. One elementary school is maintained by appellees

in each of these eighteen territories for the exclusive use of

white children, and in addition four separate elementary

schools are maintained for the exclusive use of Negro

children. Negro children must attend one of the four segre

gated schools maintained for them, even though they may

live considerably closer to one of the schools maintained for

white children. Segregation is enforced only in elementary

schools which in Topeka ends with the completion of the

sixth grade. After the sixth grade a student enters junior

high school, which along with senior high schools, is oper

ated as part of a racially integrated school system.

With respect to teacher qualifications, class size, teacher-

pupil load and courses prescribed, there is little material

difference between the eighteen schools for white children

and the four schools for colored children. Appellants intro

duced evidence to show, however, that on the average the

Negro schools were older, of lower insured value per class

room and had inferior library holdings. Evidence was also

introduced to show that Negro children, who lived close to

Gage, State Street and Oakland schools, which were new,

4

luxurious, modern educational plants maintained for white

children, were required, nonetheless, to travel a considerable

distance in order to attend one of the Negro schools which

were inferior to these in terms of physical facilities. Forty-

five percent of the white children attended schools which

were newer than the newest Negro school, and only 14%

attended schools older than the oldest Negro school. These

differences in physical facilities were brought out in the

testimony of Dr. Hugh Speer and Dr. James Buchanan who

had made a survey of the schools on behalf of appellants.

Seven additional expert witnesses testified on behalf of

appellants. In substance their testimony was that racial

segregation for school purposes is unreasonable and arbi

trary; that Negro children are relegated to an inferior

status by virtue of being required to attend segregated

schools, are confused and made personally insecure, and

that the legally enforced isolation of Negro children in

segregated public schools made it impossible for them to

receive educational opportunities equal to those presently

available to all other students.

Although the court below, in its findings of fact, found

no material difference between the Negro and white schools

with respect to physical facilities, it found that the segrega

tion complained of has a detrimental effect upon colored

children and that the “ impact is greater when it has the

sanction of law; for the policy of separating the races is

usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the Negro

group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a

child to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, there

fore, has a tendency to retard the educational and mental

development of Negro children, and to deprive them of some

of the benefits they would receive in a racially integrated

school system.”

The district court, on August 3,1951, entered a final order

and decree denying appellants’ injunctive relief on the

grounds that Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 and Gong

Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78 upheld the constitutionality of the

statute in question and that these cases had not been over

ruled by McLaurin v. Board of Regents, 339 U. S. 637 and

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 IT. S. 629. Appellants on direct

appeal are now seeking a review of this judgment by the

Supreme Court of the United States.

The Questions Are Substantial

The issues involved in this appeal are similar to those

raised in Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629; McLaurin v.

Board of Regents, 339 U. S. 637 and in Briggs v. Elliott,

now pending before the United States Supreme Court on

direct appeal from the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of South Carolina. The issues are

of vital importance especially at this time because the

preservation of strong democratic institutions necessarily

depends upon the intelligence and enlightenment of our

citizenry. When the educational and mental development

of a portion of our population is retarded by state practices

which violate the Constitution, it becomes impossible to

fully muster the capabilities and energies of the country

to meet whatever crises lie ahead.

1. We are here concerned with state power to impose

racial segregation in the broad field of public education

at the elementary school level. In the McLaurin and Sweatt

cases the United States Supreme Court dealt with the per

missible limits of such state power at the professional and

graduate school level. The issues in this appeal, how

ever, raise questions of a greater importance and of more

basic concern then the question of racial segregation in

graduate and professional schools.

The sine qua non of education in a democratic society is

the teaching of a belief in and loyalty to democratic ideals.

6

It is at the elementary or primary educational level that

children, along with their acquisition of facts and figures,

integrate and formulate basic ideas and attitudes about

the society in which they live. When these early attitudes

are born and fashioned within a segregated educational

framework, students of both the majority and minority

groups are not only limited in a full and complete inter

change of ideas and responses, but are confronted and

influenced by value judgments, sanctioned by their society

which establishes qualitative distinctions on the basis of

race. Education cannot be separated from the social

environment in which the child lives. He cannot attend

separate schools and learn the meaning of equality.1

One eminent authority in the field of educational segre

gation has summed up the role of the separate Negro

school as follows:

“ The separate school is an instrument of social

policy and a symbol of inferior status.” 2

Segregated education, particularly at the elementary

level, where the emotional aspects of learning are inex

tricably tied up with the learning process itself, must and

does have a definite and deleterious effect upon the Negro

child.3 It is particularly true that when segregation exists

1 The Main Types and Causes of Discrimination (Memorandum sub

mitted by the Secretary-General, United Nations-Commission on Human

Rights, Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection

of Minorities, Lake Success, New York, p. 50.

2 Charles H. Thompson, “ Post War Prospects of Equitable Educational

Opportunities for Negroes” in Mace Relations and Human Relations, Fisk

Univ. 1945, p. 86.

3 Max Deutscher and Isidor Chein, “ The Psychological Effects of En

forced Segregation: A Survey of Social Science Opinion,” Journal of

Psychology, 1948; 26; 259-287; David Kreeh and Richard S. Crutchfield,

Theory and Problems of Social Psychology, New York, McGraw-Hill

1948, Chapters X II and X III ; M. Radke “New Trends in the Investiga

tion of Prejudice,” Annals of the American Academy of Political Science,

1946, p. 244.

7

at the elementary level it is hard to distinguish between

fact and fiction—the fiction, in this instance, being an ar

bitrary classification on the basis of race. A recent study

of the development of attitudes towards Negroes concludes

that prejudice begins early in the life spam and develops

gradually, and that “ attitudes towards Negroes are now

chiefly determined not by contact with Negroes, but by

contact with prevalent attitudes toward Negroes.” 4

Appellants have demonstrated to the satisfaction of the

court below that segregation at the elementary school level

prejudices the Negro child in his pursuit of knowledge.

It is common knowledge that the number of persons attend

ing public elementary schools is far greater than that

attending public graduate and professional schools. It

logically follows, therefore, that the injuries which segre

gation causes in the elementary grades is more far reach

ing and devastating and affects more people than is the

case with respect to graduate and professional education.

It affects young children by creating prejudicial attitudes

which by virtue of their extreme youth they can in no

way identify.5 Since elementary education is absorbed

during the formative years of a child’s life, it assumes a

peculiar and more important role than education at any

other level. It is true that most professions and occupa

tional fields require skills and information that can only

be acquired through higher and professional education,

but it is not the skill or professional knowledge alone

that makes a good doctor, lawyer, engineer, or teacher.6

It is an integrated, intelligent and open-minded personality

4 Eugene Horowitiz, “ Development of Attitudes Towards Negroes,” in

Readings in Social Psychology, Holt, 1947, pp. 561, 517.

5 op. cit.

6 Young B. Smith, Harlan Fiske Stone: Teacher Scholar and Bean,

Col. Law Review, Yol. XLVI, Sept. 1946.

8

that can best benefit from education at any level. It is hard,

if not impossible, to build a durable building on a weak

framework. The educational process is cumulative in

nature, a person’s “ knowledge” or “ education” can never

be separated from the total personality. If a young student

can learn in a democracy and at the same time learn the

significance of democracy, he must be able to do so freely'—•

unhampered by such arbitrary and limiting factors as

distinctions on the basis of race.7 Negro children cannot

be afforded the opportunity to develop fully their intelli

gence and their mental capabilities if their training is

circumscribed and their development stunted by state prac

tices which, at the very outset of their search for education,

places them at a disadvantage with children belonging

to other racial groups.

2. Having established that racial segregation in the public

elementary schools of Topeka had a detrimental effect

upon appellants and other Negro students, affected their

motivation to learn, their educational and mental develop

ment, and deprived them of benefits which would have

been forthcoming in a racially integrated school system,

appellants were entitled to the relief prayed for in their

complaint under the rationale, of the Sweatt and McLaurin

cases. In those cases the United States Supreme Coui’t

found that equal educational opportunities in law and in

graduate training could not be obtained in a racially segre

gated educational system.

One of the chief considerations, which led the court

to conclude that equal educational opportunities were not

offered at the segregated Negro law school in the Sweatt

case, was that members of racial groups comprising 85%

7 Grunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma, Hayes, New York, 1944

(passim).

9

of the population of Texas were excluded from its student

body. The court said, at page 634:

. . With such a substantial and significant

segment of the population excluded, we cannot con

clude that the education offered petitioner is substan

tially equal to that he would receive if admitted to the

University of Texas law school.”

Thus, without regard to physical facilities, the opinion

in the Sweatt case means that equal educational oppor

tunities in law cannot be afforded a Negro applicant where

he is required to take his training in isolation from law

students who are representative of a “ substantial and

significant segment of the population.” It must have been

felt in that case, we submit, that a student who obtains an

education under circumstances such as to require daily

contact and competition with members of racial groups

comprising the dominant and more advantaged majority

would necessarily receive a better education than a student

who must get his training under conditions which would

limit him to daily contact and competition from members

of a single racial group comprising the state’s most

disadvantaged minority.

In the McLaurin case, although no question of the in

equality in physical facilities could have been raised, the

court found the state, in requiring McLaurin to sit apart

from other students in the classrooms, cafeteria and library

solely because of race, handicapped him in his pursuit of

effective graduate instruction. “ Such restrictions,” said

the court at page 641, “ impair and inhibit his ability to

study, to engage in discussions and to exchange views with

other students and, in general, to learn his profession.”

We take these two decisions to mean that any form of

state imposed racial segregation at the graduate and pro

fessional school levels of state universities contravenes

10

the Fourteenth Amendment because such restrictions handi

cap the applicant in his pursuit of knowledge and neces

sarily deprive him of equal educational opportunities. This

analysis is confirmed by Wilson v. Board of Supervisors,

supra, and McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (CCA

4th 1951) cert. den. — U.S. —, June 4, 1951.

In the McLaurin case, moreover, the court recognized

that not only would their decision affect McLaurin per

sonally but that the quality of his education had more

far-reaching implications. The court said, at page 641,

that as a trainer of others,

“ [tjhose who will come under his guidance and

influence must be directly affected by the education

he receives. Their own education and development

will necessarily suffer to the extent that his training

is unequal to that of his classmates.”

Thus the court was not only concerned with the question of

McLaurin’s personal right to equal educational oppor

tunities but was aware that his inferior training would

necessarily mean inferior training for his students. Now,

in this case, we are directly confronted with the question

with which the Court was indirectly concerned in the

McLaurin case.

At the outset of the opinion in the Sweatt case, at page

631, it was made clear that the court was deciding only the

question of the power of the state to distinguish between

students of different races in professional and graduate

education of state universities. This statement meant no

more than that the court was deciding the constitutional

question within the narrowest limits essential to the dis

position of the case at hand. This is not new but normal

Supreme Court procedure, Rescue Army v. Municipal Court,

331 U. S. 549, 568-575, and cases cited. The assertion by the

Court that it was following this practice and hence deciding

11

only the constitutionality of state-imposed segregation at

the graduate and professional school levels cannot properly

be interpreted to mean that segregation at the elementary

school level is thereby validated. Nor did the Court’s re

fusal to reexamine Plessy v. Ferguson infer that the “ sepa

rate but equal” doctrine of that case was approved as the

yardstick to determine constitutionality of racial segrega

tion in areas other than professional and graduate educa

tion. We take this refusal to mean merely that the Court

had found segregation unconstitutional at the graduate and

professional school levels and, therefore, deemed it unneces

sary to meet the question of whether Plessy v. Ferguson

had general application. The Court, without first having

facts before it, was in no position to say that segregation in

areas other than graduate and professional education was a

denial of equal protection of the laws. Where the facts

show such denial, the Court, we submit, would strike down

segregation as was done in the McLaurin and Swealt cases.

Attention is directed to Rice v. Arnold, 340 U. S. 848, dec.

Oct. 17, 1950. That case was reversed and remanded to the

Supreme Court of Florida for reexamination in the light of

the Sweatt and McLaurin cases. It is true that this case

may not necessarily mean that racial segregation on public

golf courses is considered by the Supreme Court as a denial

of equal protection of the laws. Rice v. Arnold does con

clusively indicate, we submit, that the Court’s statement in

the Sweatt case with respect to Plessy v. Ferguson was not

intended to imply that the “ separate but equal” formula

was to be used to dispose of questions involving racial seg-

gation except for graduate and professional schools. More

over, Rice v. Arnold indicates that the constitutionality of

state sanctioned racial segregation must now be deter

mined by the courts on the basis of an inquiry into its actual

effect as was done in the McLaurin and Sweatt cases. Here

the district court made such an inquiry and concluded that

12

the effect of racial segregation in this case was as perni

cious as it had been found to be in the McLaurin and Sweatt

cases. Having determined, in fact, that equal educational

opportunities were not afforded in the segregated schools

of Topeka, the court, in the light of the McLaurin and

Sweatt cases was obligated to hold that Chapter 72-1724

was unconstitutional and that appellees could not continue

to maintain separate elementary schools for Negroes and

whites.

3. Chapter 72-1724 of General Statutes of Kansas, 1949,

is clearly an arbitrary and unreasonable exercise of state

power in violation of the guarantees of the Fourteenth

Amendment for the following reasons:

A. This statute authorizes governmental classifications

and distinctions based upon race for school purposes. In

order for such classifications and distinctions to conform

with the requirements of the Federal Constitution, they

must be based upon a real or substantial difference which

has pertinence to a legitimate legislative objective. Do

minion Hotel v. Arizona, 294 U. S. 265; Skinner v. Okla

homa, 316 IT. 8 . 535. This statute cannot be sustained under

this constitutional yardstick. Certainly, the statute cannot

be sustained if based upon race alone. See Hirabayashi v.

United States, 320 U. S. 81, 100; Korematsu v. United

States, 323 U. S. 214, 216; Takahashi v. Fish and Game

Commission, 334 U. 8 . 410, 420; Oyama v. California, 332

II. S. 633, 640; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 21, 23.

There is no difference between Negro children and white

chilren with respect to ability to learn or to absorb knowl

edge based upon the racial factor alone. Whatever differ

ences exist in this regard are individual and not racial.

This is an uncontroverted scientific fact. See: Testimony

of Horace B. English. See also: Rose, America Divided:

Minority Group Relations in the United States (1948);

13

Montague, Man’s Most Dangerous. Myth— The Black &

White of Rejections for Military Service, 5 (1944) at 29;

Klineberg, Race Differences, 343 (1935). Thus, the statute

cannot be sustained if based upon a mistaken assumption

that such racial differences do in fact exist.

This statute authorizes racial segregation in the ele

mentary grades only. In Topeka, elementary school ends

with completion of the sixth grade. Thereafter, at the

junior and senior high school level, the Topeka school sys

tem is racially integrated. Moreover, the segregation au

thorized can only be imposed in cities of the first class.

Thus, whatever the basis for the classification, about which

appellants can only wildly speculate, if not based upon race

or ability to learn and absorb knowledge, it must be some

factor which is: (1) present in the first six grades of public

schools in Kansas, but not present thereafter, and (2) it

must be present in some communities in Kansas, but not in

others. This is impossible. In short, the statute cannot be

sustained under the constitutional formula, as being based

on a real and substantial difference which has pertinence to

a legitimate legislative objective to which state classifica

tions and distinctions must adhere.

B. This statute cannot be said to sustain an important

state interest particularly in view of the fact that Kansas

has a history of freedom and equality, and legally enforced

segregation is contrary to its deep-rooted traditions and

customs.

The General Statutes of Kansas, Annotated, (Corrick)

1949, outlaw discrimination in a wide variety of circum

stances.8 Section 76-307, which applies to schools of arts,

engineering, pharmacy, law and medicine, states:

“ No person shall be debarred from membership of

the university on account of age, race, sex, or religion.”

8 The statutes cited herein are set forth in Appendix B hereto.

14

Section 12-713, dealing with planning, zoning and city

planning commissions, provided:

“ Nothing herein contained shall be construed as

authorizing the governing body to discriminate against

any person by reason of race or color.”

Section 21-2424 makes it a misdemeanor punishable by a

fine of $10 to $10,000 and makes the misdemeanant liable to

a suit for damages, for any person to make a distinction on

account of race, color or previous condition of servitude in

a state university, college or other school of public instruc

tion; in a hotel, boarding house, place of entertainment or

amusement for which a license is required by municipal

authorities of the state; or in a steamboat, railroad, stage

coach, omnibus, streetcar, or other means of public car

riage.

Section 21-2461 provides that no citizen of the United

States shall be refused employment in any capacity on the

ground of race or color nor be discriminated against in any

manner in connection with any public work by or on behalf

of the state or any governmental subdivision thereof.

Section 21-2462 provides that the act of which Section

21-2461 is a part shall be included in all contracts made by

governmental subdivisions which involve the employment

of laborers and shall apply to all contractors and subcon

tractors.

Section 21-2463 provides that any officer violating the

latter two sections shall be punishable by a fine of $50-

$1,000 and by imprisonment of not more than six months

or both.

House Joint Resolution No. 1 of the House of Representa

tives of the State of Kansas [L. 1949, Oh. 289, p. 253] states

that:

15

“ • • • The state of Kansas is traditionally and his

torically opposed to discrimination against any of its

citizens in employment; and

“ • _ • • It is the public policy of this state that all of

the citizens of this state are entitled to work without

restrictions or limitations based on race, religion, creed

or national origin; . .

The final and most telling statutory provision in the laws

of the State of Kansas is the very statute here under attack,

which, by its very terms, recognizes that the distinction

herein practiced is wdiat the Fourteenth Amendment was

designed to destroy: discrimination. That statute states:

“ No discrimination on account of color shall be

made in high schools except as provided herein.”

By plain meaning and context, it is clear that this statute

recognized that segregation is discrimination.

16

Conclusion

The importance of the issues raised, the mistaken notion

of the district court that Plessy v. Ferguson and Gong hum

v. Rice required them to sustain the constitutionality of

Chapter 72-1724 of the General Statutes of Kansas, 1949, in

spite of their own findings that segregated schools in

Topeka were detrimental to appellants and to Negro chil

dren generally, the arbitrary and unreasonable nature of

the statute and the utter lack of any real state interest in

maintaining racially segregated elementary schools in Kan

sas where legally enforced racial segregation is an anomaly,

all present compelling reasons which warrant review of this

judgment on appeal by the United States Supreme Court.

Respectfully submitted,

Charles E. B ledsoe,

Charles S cott,

John S cott,

Jack Greenberg,

T httrgood M arshall,

(Signed) R obert L. Carter,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, New York,

Counsel for Plaintiff's-Appellants.

17

APPENDIX “A ”

Opinion op the Court

H uxm an , Circuit Judge, delivered the opinion of the Court.

Chapter 72-1724 of the General Statutes of Kansas, 1949,

relating to public schools in cities of the first class, so far

as material, authorizes such cities to organize and maintain

separate schools for the education of white and colored

children in the grades below the high school grades. Pur

suant to this authority, the City of Topeka, Kansas, a city of

the first class, has established and maintains a segregated

system of schools for the first six grades. It has established

and maintains in the Topeka School District eighteen

schools for white students and four schools for colored

students.

The adult plaintiffs instituted this action for themselves,

their minor children plaintiffs, and all other persons simi

larly situated for an interlocutory injunction, a permanent

injunction, restraining the enforcement, operation and exe

cution of the state statute and the segregation instituted

thereunder by the school authorities of the City of Topeka

and for a declaratory judgment declaring unconstitutional

the state statute and the segregation set up thereunder by

the school authorities of the City of Topeka.

As against the school district of Topeka they contend that

the opportunities provided for the infant plaintiffs in the

separate all negro schools are inferior to those provided

white children in the all white schools; that the respects in

which these opportunities are inferior include the physical

facilities, curricula, teaching resources, student personnel

services as well as all other services. As against both the

state and the school district, they contend that apart from

all other factors segregation in itself constitutes an inferi

ority in educational opportunities offered to negroes and

that all of this is in violation of due process guaranteed them

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Consti

tution. In their answer both the state and the school district

defend the constitutionality of the state law and in addition

18

the school district defends the segregation in its schools

instituted thereunder.

We have found as a fact that the physical facilities, the

curricula, courses of study, qualification of and quality of

teachers, as well as other educational facilities in the two

sets of schools are comparable. It is obvious that absolute

equality of physical facilities is impossible of attainment in

buildings that are erected at different times. So also abso

lute equality of subjects taught is impossible of maintenance

when teachers are permitted to select books of their own

choosing to use in teaching in addition to the prescribed

courses of study. It is without dispute that the prescribed

courses of study are identical in all of the Topeka Schools

and that there is no discrimination in this respect. It is

also clear in the record that the educational qualifications

of the teachers in the colored schools are equal to those in

the white schools and that in all other respects the educa

tional facilities and services are comparable. It is obvious

from the fact that there are only four colored schools as

against eighteen white schools in the Topeka School Dis

trict, that colored children in many instances are required to

travel much greater distances than they would be required

to travel could they attend a white school, and are required

to travel much greater distances than white children are

required to travel. The evidence, however, establishes that

the school district transports colored children to and from

school free of charge. No such service is furnished to white

children. We conclude that in the maintenance and opera

tion of the schools there is no willful, intentional or sub

stantial discrimination in the matters referred to above

between the colored and white schools. In fact, while plain

tiffs’ attorneys have not abandoned this contention, they

did not give it great emphasis in their presentation before

the court. They relied primarily upon the contention that

segregation in and of itself without more violates their

rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

This contention poses a question not free from difficulty.

As a subordinate court in the federal judicial system, we

seek the answer to this constitutional question in the deci

sions of the Supreme Court when it has spoken on the sub

19

ject and do not substitute our own views for the declared

law by the Supreme Court. The difficult question as always

is to analyze the decisions and seek to ascertain the trend

as revealed by the later decisions.

There are a great number of cases, both federal and state,

that have dealt with the many phases of segregation. Since

the question involves a construction and interpretation of

the federal Constitution and the pronouncements of the

Supreme Court, we will consider only those cases by the

Supreme Court with respect to segregation in the schools.

In the early case of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 IT. S. 537, the

Supreme Court said:

“ The object of the amendment was undoubtedly to

enforce the absolute equality of the two races before

the law, but in the nature of things it could not have

been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color,

or to enforce social, as distinguished from political

equality, or a commingling of the two races upon terms

unsatisfactory to either. Laws permitting, and even

requiring, their separation in places where they are

liable to brought into contact do not necessarily imply

the inferiority of either race to the other, and have been

generally, if not universally, recognized as within the

competency of the state legislatures in the exercise of

their police power. The most common instance of this

is connected with the establishment of separate schools

for white and colored children, which has been held to

be a valid exercise of the legislative power even by

courts of States where the political rights of the colored

race have been longest and most earnestly enforced.”

It is true as contended by plaintiffs that the Plessy case

involved transportation and that the above quoted state

ment relating to schools was not essential to the decision of

the question before the court and was therefore somewhat

in the nature of dicta. But that the statement is considered

more than dicta is evidenced by the treatment accorded it

by those seeking to strike down segregation as well as by

statements in subsequent decisions of the Supreme Court.

On numerous occasions the Supreme Court has been asked

20

to overrule the Plessy case. This the Supreme Court has

refused to do, on the sole ground that a decision of the ques

tion was not necessary to a disposal of the controversy

presented. In the late case of Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S.

629, the Supreme Court again refused to review the Plessy

case. The Court said:

“ Nor need we reach petitioner’s contention that

Plessy v. Ferguson should be reexamined in the light

of contemporary knowledge respecting the purposes of

the Fourteenth Amendment and the effects of racial

segregation. ’ ’

Gong Lum v. Eice, 275 U. S. 78, was a grade school segre

gation case. It involved the segregation law of Mississippi.

Gong Lum was a Chinese child and, because of color, was

required to attend the separate schools provided for colored

children. The opinion of the court assumes that the educa

tional facilities in the colored schools were adequate and

equal to those of the white schools. Thus the court said:

“ The question here is whether a Chinese citizen of the

United States is denied equal protection of the laws when

he is classed among the colored races and furnished facili

ties for education equal to that offered to all, whether white,

brown, yellow or black.” In addition to numerous state

decisions on the subject, the Supreme Court in support of

its conclusions cited Plessy v. Ferguson, supra. The Court

also pointed out that the question was the same no matter

what the color of the class that was required to attend

separate schools. Thus the Court said: Most of the cases

cited arose, it is true, over the establishment of separate

schools as between white pupils and black pupils, but we

cannot think that the question is any different or that any

different result can be reached, assuming the cases above

cited to be rightly decided, where the issue is as between

white pupils and the pupils of the yellow race. ’ ’ The court

held that the question of segregation was within the discre

tion of the state in regulating its public schools and did not

conflict with the Fourteenth Amendment,

It is vigorously argued and not without some basis there

for that the later decisions of the Supreme Court in Me-

Laurin v. Oklahoma, 339 II. S. 637, and Sweatt v. Painter,

339 U. 8 . 629, show a trend away from the Plessy and Lum

eases. McLaurin v. Oklahoma arose under the segregation

laws of Oklahoma. McLaurin, a colored student, applied

for admission to the University of Oklahoma in order to

pursue studies leading to a doctorate degree in education.

He was denied admission solely because he was a negro.

After litigation in the courts, which need not be reviewed

herein, the legislature amended the statute permitting the

admission of colored students to institutions of higher

learning attended by white students, but providing that such

instruction should be given on a segregated basis; that the

instruction be given in separate class rooms or at separate

times. In compliance with this statute McLaurin was ad

mitted to the university but was required to sit at a separate

desk in the ante room adjoining the class room; to sit at a

designated desk on the mezzanine floor of the library; and

to sit at a designated table and eat at a different time from

the other students in the school cafeteria. These restric

tions were held to violate his rights under the federal Con

stitution. The Supreme Court held that such treatment

handicapped the student in his pursuit of effective graduate

instruction.9

9 The court said: “ Our society grows increasingly complex, and our

need for trained leaders increases correspondingly. Appellant’s case

represents, perhaps, the epitome of that need, for he is attempting to

obtain an advanced degree in education, to become, by definition, a leader

and trainer of others. Those who will come under his guidance and

influence must be directly affected by the education he received. Their

own education and development will necessarily suffer to the extent that

his training is unequal to that of his classmates. State imposed restric

tions which produce such inequalities cannot be sustained.”

“ It may be argued that appellant will be in no better position when

these restrictions are removed, for he may still be set apart by his fellow

students. This we think irrelevant. There is a vast difference—a Con

stitutional difference—between restrictions imposed by the state which

prohibit the intellectual commingling of students, and the refusal of

individuals to commingle where the state presents no such bar. * * *

having been admitted to a state supported graduate school, [he] must

receive the same treatment at the hands of the state as students of other

races.

22

In Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629, petitioner, a colored

student, filed an application for admission to the Univer

sity of Texas Law School. His application was rejected

solely on the ground that he was a negro. In its opinion

the Supreme Court stressed the educational benefits from

commingling with white students. The court concluded

by stating: “ We cannot conclude that the education offered

petitioner in a separate school is substantially equal to

that which he would receive if admitted to the University

of Texas Law School.” If segregation within a school

as in the McLaurin case is a denial of due process, it is

difficult to see why segregation in separate schools would

not result in the same denial. Or if the denial of the

right to commingle with the majority group in higher

institutions of learning as in the Sweatt case and gain

the educational advantages resulting therefrom, is lack

of due process, it is difficult to see why such denial would

not result in the same lack of due process if practiced in

the lower grades.

It must however be remembered that in both of these

cases the Supreme Court made it clear that it was con

fining itself to answering the one specific question, namely:

“ To what extent does the equal protection clause limit

the power of a state to distinguish between students of

different races in professional and graduate education in

a state university?” , and that the Supreme Court refused

to review the Plessy case because that question was not

essential to a decision of the controversy in the case.

We are accordingly of the view that the Plessy and Lum

cases, supra, have not been overruled and that they still

presently are authority for the maintenance of a segregated

school system in the lower grades.

The prayer for relief will be denied and judgment will

be entered for defendants for costs.

Entered August 3, 1951.

23

F indings op F act

I

This is a class action in which plaintiffs seek a decree,

declaring Section 72-1724 of the General Statutes of Kansas

1949 to be unconstitutional, insofar as it empowers the

Board of Education of the City of Topeka “ to organize

and maintain separate schools for the education of white

and colored children” and an injunction restraining the

enforcement, operation and execution of that portion of

the statute and of the segregation instituted thereunder

by the School Board.

II

This suit arises under the Constitution of the United

States and involves more than $3,000 exclusive of interest

and costs. It is also a civil action to redress an alleged

deprivation, under color of State law, of a right, privilege

or immunity secured by the Constitution of the United

States providing for equal rights of citizens and to have

the court declare the rights and other legal relations of

the interested parties. The Court has jurisdiction of the

subject matter and of the parties to the action.

III

Pursuant to statutory authority contained in Section

72-1724 of the General Statutes of Kansas 1949, the City

of Topeka, Kansas, a city of the first class, has established

and maintains a segregated system for the first six grades.

It has established and maintains iri the Topeka School Dis

trict, eighteen schools for white children and four for

colored children, the latter being located in neighborhoods

where the population is predominantly colored. The City

of Topeka is one school district. The colored children

may attend any one of the four schools established for

them, the choice being made either by the children or by

their parents.

24

IV

There is no material difference in the physical facilities

in the colored schools and in the white schools and such

facilities in the colored schools are not inferior in any

material respect to those in the white schools.

V

The educational qualifications of the teachers and the

quality of instruction in the colored schools are not inferior

to and are comparable to those of the white schools.

VI

The courses of study prescribed by the State law are

taught in both the colored schools and in the white schools.

The prescribed courses of study are identical in both

classes of schools.

VII

Transportation to and from school is furnished colored

children in the segregated schools without cost to the

children or to their parents. No such transportation is

furnished to the white children in the segregated schools.

VIII

Segregation of white and colored children in public

schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children.

The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law;

for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted

as denoting the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of

inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segre

gation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to

retain the educational and mental development of negro

children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they

would receive in a racial integrated school system.

IX

The court finds as facts the stipulated facts and those

agreed upon by counsel at the pre-trial and during* the

course of the trial.

25

Conclusions of Law

I

This court lias jurisdiction of the subject matter and of

the parties to the action.10

II

We conclude that no discrimination is practiced against

plaintiffs in the colored schools set apart for them because

of the nature of the physical characteristics of the build

ings, the equipment, the curricula, quality of instructors

and instruction or school services furnished and that they

are denied no constitutional rights or privileges by reason

of any of these matters.

III

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, and Gong Lum v. Rice,

275 U.S. 78, upholds the constitutionality of a legally segre

gated school system in the lower grades and no denial of due

process results from the maintenance of such a segregated

system of schools absent discrimination in the maintenance

of the segregated schools. We conclude that the above cited

cases have not been overruled by the later cases of Mc-

Laurin v. Oklahoma, 339 U.S. 637, and Sweatt v. Painter,

339 U.S. 629.

IV

The only question in the case under the record is whether

legal segregation in and of itself without more constitutes

denial of due process. We are of the view that under the

above decisions of the Supreme Court the answer must be

in the negative. We accordingly conclude that plaintiffs

have suffered no denial of due process by virtue of the man

ner in which the segregated school system of Topeka, Kan-

10 Title 28 U.S.C. § 1331; idem §1343; idem Ch. 151.

Title 8 U.S.C. Ch. 3. Title 28 U.S.C. Ch. 155.

2G

sas, is being operated. The relief sought is therefore de

nied. Judgment will be entered for defendants for costs.

Entered August 3, 1951.

W alter A . H ijxman,

Circuit Judge;

A rthur J. M ellott,

Chief District Judge;

D elmas C. H ill,

District Judge.

Decree

Now, on this 3rd day of August, 1951 this cause comes

regularly on for hearing before the undersigned Judges,

constituting a three-judge court duly convened pursuant to

the provisions of Title 28 U.S.C. 2281 and 2284.

The Court has heretofore filed its Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law together with an opinion and has held

as a matter of law that the plaintiffs have failed to prove

they are entitled to the relief demanded.

Now, T h er efo re , I t I s by t h e Court, considered, ordered,

adjudged and decreed that judgment be and it hereby is

entered in favor of the defendants.

W alter A. I I u x m a s ,

Circuit Judge;

A rthur J. M ellott,

Chief District Judge;

D elmas C. H ill,

District Judge.

Entered August 3, 1951.

APPENDIX “B”

General Statutes of Kansas, 1949

72-1724—Public Schools in Cities of First Class.—The

board of education shall have power to elect their own

officers, make all necessary rules for the government of

the schools of such city under its charge and control and of

the board, subject to the provisions of this act and the laws

27

of this state; to organize and maintain separate schools

for the education of white and colored children, including

the high schools in Kansas City, Kan.; no discrimination

on account of color shall be made in high schools except

as provided herein; to exercise the sole control over the

public schools and school property of such city; and shall

have the power to establish a high school or high schools

in connection with manual training and instruction or other

wise, and to maintain the same as a part of the public-school

system of said city.”

76-307—Tuition and fees; persons not debarred on ac

count of age, race, sex or religion.— . . . No person shall

be debarred from membership of the university on account

of age, race, sex, or religion.

12-713—Race discriminations.—Nothing herein contained

shall be construed as authorizing the governing body to

discriminate against any person by reason of race or color.

21-2424—Denying civil rights on account of race or color;

penalty-—That if any of the regents or trustees of any state

university, college, or other school of public instruction,

or the state superintendent, or the owner or owners, agents,

trustees or managers in charge of any inn, hotel or board

ing house, or any place of entertainment or amusement for

which a license is required by any of the municipal authori

ties of this state, or the owner or owners or person or

persons in charge of any steamboat, railroad, stage coach,

omnibus, streetcar, or any other means of public carriage

for persons or freight within the state, shall make any

distinction on account of race, color, or previous condition

of servitude, the person so offending shall be deemed guilty

of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction thereof in any

court of competent jurisdiction shall be fined in any sum

not less than ten ($10.00) nor more than one thousand

($1,000.00) dollars, and shall also be liable to damages in

any court of competent jurisdiction to the person or persons

injured thereby.

21-2461—Denying public work employment on account of

race or color.—No person a citizen in the United States

shall be refused or denied employment in any capacity on

the ground of race or color, nor be discriminated against in

any manner by reason thereof, in connection with any

public work, or with the contracting for or the performance

of any work, labor or service of any kind on any public work

by or on behalf of the state of Kansas, or of any depart

ment, bureau, commission, board or official thereof, or by

or on behalf of any county, city, township, school district

or other municipality of said state.

21-2462—The provisions of this act shall apply to and

become a part of any contract hereafter made by or on

behalf of the state, or of any department, bureau, commis

sion, board or official thereof, or by or on behalf of any

county, city, township, school district, or other municipality

of said state, with any corporation, association or person

or persons, which may involve the employment of laborers,

workmen, or mechanics on any public work; and shall apply

to contractors, sub-contractors, or other persons doing or

contracting to do the whole or a part of any public work

contemplated by said contract.

21-2463—Any officer of the state of Kansas or of any

county, city, township, school district, or other municipality,

or any person acting under or for such officer, or any con

tractor, sub-contractor, or other person violating the pro

visions of this act shall for each offense be punished by fine

of not less than fifty ($50.00) dollars nor more than one

thousand ($1,000.00) dollars, or by imprisonment of not

more than six (6) months or by both fine and imprisonment.

House Joint Resolution No. 1—Approved April 5, 1949

A joint Resolution creating a temporary commission to

study and make a report on acts of employment discrimina

tion against citizens because of race, creed, color, religion

or national origin, prescribing its powers and duties and

making appropriations therefor.

Whereas, It has been brought to the attention of the

legislature of the State of Kansas that probable cause exists

for the belief that acts of discrimination in employment are

29

being perpetrated against some of the citizens of the United

States because of race, creed, color, religion or national

origin; and

Whereas, The state of Kansas is traditionally and histori

cally opposed to discrimination against any of its citizens

in employment ; and

Whereas, It is the public policy of this state that all of

the citizens of this state are entitled to work without re

strictions or limitations based on race, religion, creed or

national origin; and

Whereas,The legislature does not have sufficient informa

tion upon which to enact adequate and proper laws and

there is a difference of opinion as to whether the alleged

discriminatory employment conditions actually exist: Now,

therefore

Be it resolved by the House of Representatives of the State

of Kansas, the Senate agreeing thereto:

§ 1. There is hereby created a temporary commission,

hereinafter referred to as the commission, to be known as

the “ Kansas commission against employment discrimina

tion” consisting of five (5) members to be appointed by the

governor.

§ 2. The commission shall organize and elect a chairman,

vice-chairman and secretary on or before June 1, 1949, and

is hereby authorized to hold such meeting at such times and

places within this state as may be necessary to carry out

the provisions of this resolution. The commission shall

complete its duties as speedily as possible and shall submit

its report to the governor and to the members of the Kansas

legislative council on or before October 15, 1940.

§ 3. The commission shall have full, power and authority

to receive and investigate complaints and to hold hearings

relative to alleged discrimination in employment of persons

because of race, creed, color or national origin.

§ 4. The commission is hereby authorized to employ such

clerical and other assistants as may be necessary to enable

30

it to properly carry out the provisions of this resolution

and to fix their compensation.

§ 5. The members of the commission shall receive as com

pensation for their services the sum of fifteen dollars ($15)

per diem and their actual and necessary expenses for time

actually spent in carrying out the provisions of this resolu

tion: Provided, That in no case shall any member receive

more than a total of five hundred dollars ($500) as per

diem allowance.

§ 6. The commission shall have all the powers of the legis

lative committee as provided by law, and shall have power

to do all things necessary to carry out the intent and

purposes of this resolution and the preamble thereto.

§ 7. There is hereby appropriated to the Kansas com

mission against discrimination, out of any moneys in the

state treasury not otherwise appropriated, the sum of five

hundred dollars ($500) for the fiscal year ending June 30,

1949, and the sum of three thousand five hundred dollars

($3,500) for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1950, for the

purpose of carrying out the provisions of this resolution:

Provided, That any unexpended and unencumbered balances

of said appropriations as of June 30, 1949, and June 30,

1950, respectively, are hereby reappropriated for the same

purposes for the next succeeding fiscal year.

§ 8. The auditor of state shall draw his warrants upon

the state treasurer for the purposes provided for in this

resolution upon duly itemized vouchers, executed as now or

may hereafter be provided for by law, assigned in his office

and approved by the chairman of the Kansas commission

against discrimination.

§ 9. This act shall take effect and be in force from and

after its publication in the official state paper.

Filed October 1, 1951.

(8589)