Westberry v. Fisher Opinion and Order of the Court

Public Court Documents

January 12, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Westberry v. Fisher Opinion and Order of the Court, 1970. 478848da-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b62fa154-5909-401e-bcf1-215ab78be296/westberry-v-fisher-opinion-and-order-of-the-court. Accessed March 10, 2026.

Copied!

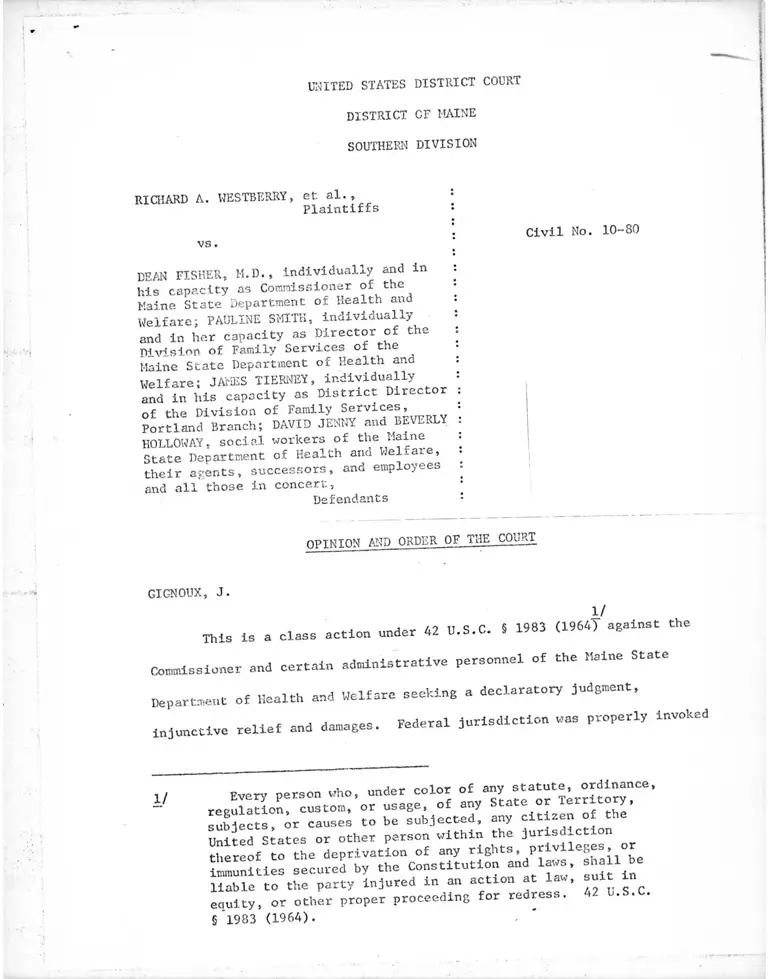

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

DISTRICT CF MAINE

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RICHARD A. WKSTBERRY, et. al. ,Plaintiffs

vs.

DEAN FISHER, M.D., individually and in

his capacity as Commissioner of the

Maine State Department of Health and

Welfare; PAULINE SMITH, individually

and in her capacity as Director of the

Division of Family Services of the

Maine State Department of Health and

Welfare; JAMES TIERNEY, individually

and in his capacity as District Director

of the Division of Family Services,

Portland Branch; DAVID JENNY and BEVERLY

HOLLOWAY, social workers of the Maine

State Department of Health and Welfare,

their agents, successors, and employees

and all those in concert,fart A ary Q

Civil No. 10-80

nPTWTON AND ORDER OF THE COURT

GIGNOUX, J.

1/

This is a class action under 42 U.S.C. 8 1983 (1964) against the

Commissioner and certain administrative personnel of the Heine State

Department of Health and Welfare seeking a declaratory judgment,

injunctive relief and damages. Federal jurisdiction was properly invoked

1/ Every person who, under color of ’

- regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Teiritory,

subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the

United States or other person within the jurisdiction

thereof~to the deprivation of any rights, privileges,0

rvUipc; secured by the Constitution and laws, shall b

S f e 1 e0Sth:Cpa«ybyinjured in an action at law. suit n

equity, or other proper proceeding for redress. 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983 (1964).

2

under 28 U.S.C. § 1343(3) end (4) (1964)! A Three-Judge District Court

was convened as r e a r e d by 28 U.S.C. 5 2281 (1964). That Court held in

an opinion dated March 21. 1969, H e s t b e H i ^ ^ i S T ' 297 F' SuPP' U °9 ̂

(D.Me. 1969), that Maine's so-called "maximum grant" and "maximum budget

regulations, which provided, in substance, that under no circumstances

could a family entitled to benefits under the State's Aid to Families

with Dependent Children Program (AFDC) have a "budgeted need" of more

than $300 per month, or receive a grant from the State in excess of $260

per month, violated the Egual Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States. Accordingly, on April 14,

1969 judgment was entered declaring the challenged regulations unconsti

tutional and void, and enjoining defendants from their further enforcement.

Thereafter, with the agreement of the parties, the Three-Judge Court was

2 /

The district courts shall have original jurisdiction

of S y civil action authorized by law to be commenced by

any person:

* & •k k

(3) To redress the deprivation, under color of any

estate law statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or

s . r s v ’. r * * y-

aTl^persons°within S ^ d ^ of £ UnSed States;

To recover damages or to secure equitable or

other’relief^nder any Act of Congress providing for

the protection of civil rights, Including the right

to vote. 28 U.S.C. § 1343(3) and (4) (1964).

dissolved, and the matter was remanded to the single judge to whom the

complaint was originally presented for a determination of plaintiffs’

damage claims. See P u b l i ^ ^ ^

Freight Lines, 312 U.S. 621, 625 (1941); D a v i ^ ^ ^

142 F. Suop. 616 (E.D.Va. 1956); MechUn£_Ba^

368 U.S. 324, 331, 336 (1961) (dissenting opinion). The present

proceeding is confined to the issues thus presented.

Plaintiffs are members of a class composed of AFDC recipients

who have large families and whose grants were limited by one or both

of the two regulations. The class is now closed and constitutes,

including the original plaintiffs, s e e 53 claimants who have intervened

on behalf of themselves and their minor children. They now seek to

recover damages in the following three categories:

(1) Retroactive AFDC benefits withheld during the period

from the date of the filing of the complaint on April 18,

ia6R until the Department began making corrected payments

- 3 -

1 / On Julv 30 1969 the Court ordered that in accordance with the3/ On July J , 23(d), notice be given by publi-provisions of Fed. K. civ. r. v /> . ( „i

T a i « i r £s l L “ migh^eprirrSt r L T t ^ r f, S*69. intervene

S l h e resenf actfon J d JrLent their claims for damages as ad̂ afsŜ rSenLf S£ 5* ,

and members of the class who have intervened to date.

- 4 -

in the spring of 1969. The total amount of the benefits

so withheld has been stipulated to be $45,903.

(2) Support monies collected by the Department pursuant

to Public Assistance Paymentsjlanual, ch. HI, § A,

at 1-2 (Rev. 7/1/68). These monies were collected from

persons legally obligated to support mothers with dependent

children and were applied against the maximum budget

allowable to any family. The total amount of support

monies thus withheld has been stipulated to be $2,752.

(3) Consequential damages for pecuniary and other losses

sustained as a result of the application to plaintiffs of

the challenged regulations. These include out-of-pocket

expenditures for medical attention and health insurance

payments necessitated by the denial of State Medicaid

coverage, and lost wages claimed to be the result of the

maximum budget regulation. The total amount of these

damages has been stipulated to be $1,958.28.

For the purposes of this litigation, the parties have stipulated

that the $250 maximum grant regulation invalidated in this case was

first promulgated in 1950 by David H. Stevens, then Commissioner of the

Maine Department of Health and Welfare; that defendant Fisher became

commissioner of the Department in 1954; that the $300 maximum budget

LI Ac? of April 21, 1969 the Department of Health and Weifare

- corrected the payments due to all members of the affected

class.

- 5 -

regulation was first promulgated in 1956 by defendant Fisher; and that

prior to their being put into effect, both regulations were submitted to

the United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare and

approved by its duly authorized representatives, although neither

regulation was submitted to the Maine Attorney General for approval

as to legality.

Plaintiffs' principal contention is that they are entitled

42 U.S.C. § 1983 to recover of the defendants, both in their individual

and in their representative capacities, all damages snstained by them

resulting from application of the unconstitutional regulations.

Alternatively, plaintiffs claim that this Court should order the

retroactive payment of the benefits illegally withheld from then, on

the authority of the so-called "Fair Hearing" regulations which were

issued by the United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare

and adopted by the Maine State Department of Health and Welfare during

the pendency of this actiom For the reasons which follow, the Conrt

has concluded that neither Section 1963 nor the "Fair Hearing"

regulations support an award of damages to plaintiffs in this action.

3/ See Federal Handtooh of Public teslstance ^ministration,

- S O T O O T W o T 6500 (eff. July 1, 1968), U. S. IXpt. o

Health, Education and Welfare State Letter so. ’

sept 30, 1968 (eff. July 1 , 1968); Maine Public Assistance

Payments Manual, ch. I, § C (Rev. 7/1/ ).

- 6 -

Plaintiffs seek first to hold defendants personally liable for

damages under Section 1983. Because the record in this case is devoid

of any indication that defendants acted other than in good faith and

within the scope of their authority, no personal liability can attach

to them.

Section 1983 makes liable "every person" who under color of state

law deprives another person of his civil rights. That it imposes liability

on state officials for acts done, either within or without the scope of

their authority, was definitely established by HoJ1SeJn J ’aEe , 365 8.S.

1.67, 171-187 (1961). Furthermore, Section 1983 xs cast xn terms

broad as to indicate that governmental immunity can never be a defense

in suits brought under that section. Nevertheless, despite the broad

sweep of the statutory language, it-has- now been authoritatively

* -s:rs Bfeawr-rars.

1953), the literal language of the statute,

secured by ^Constitution of the United States shall

be liable in damages to the person injured.

S E T g E “. f T ^ everywhere*1 the defendants

may have acted in good faith, in compliance with what

they believe to be their official duty. Id. at 706.

_____ V.M 129. 133 (2d Cir. 1966).

determined that it was not the intention of Congress in enacting

Section 1903 "to abolish wholesale all common-law immunities."

Pierson u. Ray, 386 11.S. 547, 554 (1967). Thus, the Supreme Court

has held that Section 1983 did not abrogate the Immunity of legislators

for acts within their legislative role, Tenney V. Brandhove, 341 U.S.

367 (1951), or the immunity of judges for acts in discharge of th

judicial functions, Pierson v. Ray, supra at 553-555. And the lo.er

federal courts have extended this immunity to a wide variety of

judicial and quasi-judicial officers, including clerks of court,

justices of the peace, prosecuting attorneys, and sometimes even

governors, jailers, and parole board members. See, e ^ , Sullivan_v.

KgUeher, 405 F.2d 486 (1st Cir. 1968); S«»!LVt_fim!Pi, 409 F.2d 341

(7th Cir. 1969); Fanale v. Sheehy, 385 F.2d 866 (2d Cir. 1967); Shades

v, Meyer, 334 F.2d 709 (8th Cir.), cert, denied 379 U.S. 915 (1964);

Kenney v. Fox. 232 F.2d 288 (6th Cir.), cert^_denied 352 U.S. 855

(1956); nelanev v. Shobe, 235 F. Supp. 662 (D.Ore. 1964).

The Supreme Court has not definitively spoken on the applicability

of the doctrine of governmental immunity in actions brought under

Section 1983 against state administrative officials, such as the

defendants in this case. Plainly, such officials are not entitled to

the absolute immunity which has been accorded to legislators and judges,

for "to hold all state officers immune from suit would very largely

frustrate the salutary purpose of this provision." Jobson v. llenne,

supra at 133; Hoffman v. Balden, 268 F.2d 280, 300 (9th Cir. 1959).

- 7 -

- 8 -

However, in addition to reaffirming the common-law immunity of Judges,

the Court in Piers ^ v j f f l specifically held that the defense of good

faith and probable cause was available in an action under section 1983

to police officers who had arrested the petitioners, acting under a

atatute which was subsequently held to be unconstitutional, but which

the officers had probable cause to believe to be valid.

555-557. The Court thus made it clear that state officers, although

not entitled to an absolute and unqualified immunity, have at least a

Umited immunity for acts done by them in good faith within the scope

of their official duties.

In Pierson, the Supreme Court appears to have adopted the test

enunciated more than ten years previously by Judge Magruder in his

landmark opinions in C o M ? _ v ^ C i a u j i M ^ > s m Z -

216 F. 2d 583 (1st Cir. 1954). CobbVaJ*ffi-°tMalden was a civil rights

action by school teachers who claimed to have been wrongfully discharged

against the City of Malden, its mayor, and members of its city council.

i j t-hit- case Judge Magruder stated that:In his concurring opinion m tnat case, ju g

the Act merely expresses a prima facie liability,

l e a ^ / f t h t ^ r t s o w k g m^ase^to^case, the

appropriate “tfthe fartfcSa? case. 202 F.2d at 706.

He then concluded:

Hence I take it as a roughly

that members of a city count , d ' having complete

s r s s r u o£ " elr o££lcialduty as they understood it. Id. at 70 .

- 9 -

A year later, writing for the court in Fr a n c i i ^ y m a i . "hlch

affirmed the dismissal of a complaint under Section 1983 against the

superintendents of two state penal institutions, lodge Hagruder said

that "we think it no longer appropriate" to "give effect to the statute

1 " 216 F 2d at 587; instead, it is the duty ofin its literal wording, 21b i.za au

the court to,

. . . fit the statute as

the familiar and generally accepted legal hackgr

to confine its application, within reason, al o£

i X r l s f t ? i f had

r S ^ r ^ S n l : the *

Continuing, he further stated:

Where the act has been invoked ^Jj^^uction Congress

doubt were a “ ^ “ "^Jolving-race discrimination) .

- fy r ...tS officials that they

may have acted, not maliciously, but in tae goo un,Jer

belief that they were ^ ^ a l e lSls!ation. They are

what they thought was vali c - beyond such situations,

said to act at their peril. • • • B“” ^ ons to restrict

S I . S S S S 5 which^undoubtedl^woul^ensue. Id. at SS8.

Other courts, both before and subsequent to Pierson, have

enunciated similar tests. See, Si£m. Silver v. Dickson, 403

(9th Cir. 1968), S h i S M » * ”-S- (1969)! S S ^ l i i ^ i e d i t h ’

386 F.2d 958, 960-961 (10th Cir. 1967); Hojfma^vjalden, 268 F.2d 280,

298..300 (9th Cir. 1959). «. S S S ^ J S S S * * » *.S. 564, 573 (1959).

As one distinguished commentator has observed, the approach adopted by

Judge Magruder "seems likely to control the law of the fut

. K Aft at 541 (1958). See Jaffe, Suits Administrative Law Treatise, § 2 .

governments and of f i c e r ^ a m a ^ A c t i ^ , 77 Harv. L.

209, 221-222 (1963); Hot., The_fioctr3^oO«l ^

Civil Rights Act, 68 Harv. H. Rev. 1229, 1238-1240 (1955); Note, The

Z T ^ T t h e Clviljlghts^ct. 66 Harv. L. Rev. 1285, 1295-1299

(1953). in the absence of contrary authority, it is accepted as controlling

in this case.

It is not necessary in the present case to fix the limits of the

immunity to which state officials may he entitled in actions under

section 1983, for it is clear that under the foregoing standard the

present defendants should not be denied governmental Immunity. The

record is utterly devoid of any proof of abuse of discretionary authority,

malice or ill-will on the part of any of these defendants. It has been

stipulated that defendant fisher acted within the scope of his authority

in promulgating the maximum budget regulation and in enforcing the

maximum grant regulation promulgated by his predecessor, furthermore,

he was acting within the rule-making power conferred upon him by law.

22 M R.S.A. § 3741 (1964), as amended (Supp. 1968-69); see 42 U.S.C.

§§ 601-602 (1969). The contested regulations had been approved by the

United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare, and tacit

approval of the regulations appears to have been given by the State

of Maine. *,11. high state officials may be expected to be reasonable

, im hP exDected to be seers in the crystal men, they neither can nor should be expected

_ A i rnrtrine They are not “charged with predicting ball of constitutional eoctrine. in y

r Mt„Honal law." Pi arson v. Ray,, su£ra at 557.the future course of constitution -

- 10 -

- 11 -

So far as the defendant lower-echelon officials of the Health

Welfare Department are concerned, it is apparent that the choice before

them was to enforce a long-standing and apparently valid system of

regulations or to disobey them and risk disciplinary action by their

superiors. Like the policemen in Pierson, their lot is not so unhappy

that (they) must choose between being charged with dereliction of duty

if (they do not enforce the regulations), and being mulcted in damages

if (they do).” Id. at 555. And again the record is conspicuously

silent as to any evidence of malice or iU-will shown by any of these

defendants.

Being satisfied that the acts of which plaintiffs complain were

done by defendants "in good faith in performance of their official doty

as they understood it," the Court holds that under the circumstances

of this case defendants are not personally liable for damages under

Section 1983.

II

Plaintiffs seek next to hold defendants liable for damages

under Section 1983 in their official capacities as officers of the

State of Maine. In this aspect, they concede that the purpose of

their suit is to obtain a judgment which will establish a liability

of the State and will be payable out of the public funds of the State

It is clear that such a suit is in actuality one against the State,

even though the State is not named as a'defendant. Kennej^CbPoer

e x p „ grate lax Commission, 327 U.S. 573, 576-577 (1946); Ford

CO V. henartrnent of Treasury of Indiana, 323 U.S. 459, 463-464

12

(1945); Great Northern Life Ins. Co. v. Read, 322 U.S. 47, 51 (1944);

Tn re State of New York, 256 U.S. 490, 500-503 (1921); Smith v. Reaves,

178 U.S. 436, 438-440 (1900); In re Ayers, 123 U.S. 443 (1887); O'Neill

v. Early, 208 F.2d 286 (4th Cir. 1953); Klng^v- McGinnis, 289 F. Supp.

466 (S.D.N.Y. 1968); cf. Larson v. Domestic & Foreign Commerce Cor£.,

337 U.S. 682 (19497. As such, there are two reasons why the suit must

fail for want of jurisdiction.

In the first place, suits under Section 1983 may be maintained

only against a "person" who under color of state law deprives another

of his civil rights. Monroe v. Pape, suora at 187-192, established that

a municipal corporation is not a "person" subject to suit under the Act.

It is equally clear that a state is not a "person" within the meaning of

the Act. Whltner v. Davis, 410 F.2d 24, 29 (9th Cir. 1969); Williford v,

California, 352 F.2d 474, 476 (9th Cir. 1965); King,v. McGinnis, supra at

468; United States ex rel. Gittlemacker v. Pennsylvania, 281 F. Supp.

175, 178 (E.D.Pa. 1968).

7/ As was said in Minnesota v. Hitchcock, 185 U.S. 373, 387 (1902),

. . whether a suit is one against a State is

to be determined, not by the fact of the party named

as defendant on the record, but by the result of the

judgment or decree which may be entered. . . .

8/ In Cobb v. City of Malden, supra at 703, the Court of Appeals

“ for this Circuit had previously arrived at the same conclusion.

I

- 13 -

In the second place, the State o£ Maine Is entitled to the

protection o£ the Eleventh Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States, which provides:

The Judicial power of the Uni ted

construed to extend to any united States by Citizensor prosecuted against one of the United States y

of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects of any foreign

State.

Although the Eleventh Amendment in terms inhibits only federal

court suits against a state by citizens of another state, it has long

been established that a state is equally immune from federal court suits

brought by its own citisens. Hans^Louisiana, 134 U.S. 1 (1890);

_ 1-70 ti c Sift 524-525 (1899); Duhne v. New^Jersey,Fitts v. McGhee, 172 U.S. 51b, 5Z4 ' > --- —

25i u.S.-311, 313 (1920); Great Northern L i f _ ^ a^_Co^va_Rgad, supra

at d. While a state may waive its immunity, see, e^g^, P

----- - n-Hwau of the Alabama^tate^Docks^Degartment, 377 U.S. 184

’(1964); ....... Tennessee-Missourl bridge Commission, 359 U.S. 275

(1959), there is nothing to indicate that the State of Maine has done

so insofar as actions such as the present one are concern

9/ There has been considerable g ^ “ . 3 L S * tI?J.SS 3 S t 0mrt

meant to say in the crucial nan . ,,,, ....tension

whether the basis of that ' common-law conceptsof the Eleventh . ° raditional^c^ ^

of sovereign immunity. Su” *q „„„ citizens

Suits ...Inst States in the Federal teurta, 33 U. an.

331, T34-335 (1966).

Plaintiffs argue strenuously that the line of cases beginning

with Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908), provides the basis for the

recovery of damages against the State in this case, despite the bar of

the Eleventh Amendment. Concededly, it has been settled law

Ex parte Young that suits against state officials to enjoin them from

unconstitutional action are not forbidden by the Eleventh Amendment.

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince. Edward County, 377 U.S. 218,

228 (1964); Georgia Railroad & Banking Co^ ^ d w i n e , 342 U.S. 299,

303-306 (1952). In such cases, the officer is deemed to be stripped

his official capacity and to be acting individually. Davis, Suing.the

nnvemment by Falsely Pretetriln&_TSLS^ 29 U. Chi. L. Rev.

435, 437 (19617. To date, however, the Supreme Court has not seen fit

to extend the doctrine of Ex parte Young to permit the recovery of

monetary damages. In those cases in which the recovery of money from

the state’s treasury has been sought, the Court has consistently adhered

to the rule that a state cannot be sued in a federal court without its

consent. Kennecott Copper Corp. v. StateJ^xtonBrigsi^, su£ra; Ford

Motor Co. v. Department of Treasury of Indiana, supra, Great Northe

- 14 -

10/ In discussing the Young decision, Professor Davis has stated:

[The Court] was deliberately indulging in

fiction’in order to find a way around sovereign

immunity. It knew that the injunction against the

attorney general was in truth a means of preventing

the state from enforcing the statute. The reality

is all too obvious that the suit was in practical

effect a suit against the state. 3 Davis, Adminis

trative Law Treatise § 27.03 at 553 (1958).

'I

_ , ____ _ of New York, supra\ Smitt\

Life Insurance Co. v. Rea_4.» £̂ £̂£5.’ ----- —-- ----- ~

v. Reeves, supra. See nhitner u. Davis, supra; DeLcvav u. Richmond County

School Board, 284 F.2d 340 (4th Cir. 1960); O ^ e i U v ^ r l Z . 208 F.2d 286

11 /

(4th Cir. 1953).

A recent case much urged upon the Court by plaintiffs is Boardof

of Arkansas A 8 (1 College_2A_Davls ■ 396 F. 2d 730 (8 th Cir.),

cert, denied 393 U.S. 962 (1968). That case, however, appears to be more

persuasive of the position urged by defendants than of that sought by

plaintiffs. Plaintiff in that case had brought suit under Section 1983

against the president and board of trustees of a state college for

alleged wrongful discharge from his teaching position. He sought injunctive

relief, back pay and damages. The Court held that the claim for injunctive

relief was not barred by the Eleventh Amendment under the doctrine of

P, parte Young and subseguent cases. Id- at 732-734. However, so far as

the claim for back pay and damages was concerned, the Court held that

plaintiff could only recover of the defendants individually, noting that,

- 15 -

11/ It is perhaps worthy of note that in F^ryland v. kir » coverage

- 183 (1968), the appellant States argued not only that t _

of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 193b, as amenu ,

ia not- V,p extended to state employees, but that

remedial provisions of the Act ^ 1 ! , ! ! ^ piesented! the Court

Eleventh Amendment issue was ..'^sovereign immunity from suit

reserved the question of a f case 392 U.S. at 200.

under the Act for an appropriate future

- 16 -

Our holding in not to be i«erp«ted t° - a n that

the complaint states a claim for rel 8

College or the State of Arkansas. Id. at

in concluding that plaintiffs' claim for damages against defendants

in their representative capacities as state officials is in effect a suit

against the State of Maine of which a federal court does not have Juris-

diction, the Court is aware that in several recent welfare ca^

federal courts have awarded damages - to date, only in the form of retro

active payments of benefits wrongfully withheld. See Gaudis_y^Ja

69 Civ. 258 (S.D.M.Y. October 14, 1969) (3-judge court); Damicojt.

California, Hcs. 46538 6 48462 (M.D.Cal. Sept. 12. 1969)(3-judge court);

Cooly v. Juras, Civ. ho. 67-662 (D.Ore. duly 14, 1969) (3-judge court);

^ 7 ^ , 299 r. Supp. 644, 646 (W.D.Kx. 1969) (3-judge court)

(retroactive benefits limited to named plaintiffs) ; ^ s o n ^ ^ i t o ,

270 F. Supp. 331, 338 (D.Conn. 1967) (3-judge court), affW 394 U.S. 618

(1.969). see RobiH o!L v J « *>• 68-’"-294 ‘S'”' ™ ' ^

1,69) (3-judge court); M U i H ^ a n d r l d s e , 297 F. Supp. 450, 459

(B.Ud. 1968) (3-judge court), appeal docketed Mo. 131 D.S. Sup.

May 19, 1969; Robinson v. Washington. 302 F. Supp. 842, 844 (D.D.C.

1969); noe v Shapiro , 302 F. Supp. 761, 768 (D.Conn. 1969); SolmanJ,.

Shapiro, 300 F. Supp. 409, 416 (D.Conn. 1969), 3 2 - ^ c h e t e d Mo. 215

7 ^ P . Ct„ dune 9, 1969. It is not easy to reconcile the cases

„hich have awarded retroactive payments with the preseht ruling. It

appears, however, that the guestions dealt with in this opinion were

- 17 -

not raised in those cases, either by the parties or by the Court.

The Court holds that insofar as plaintiffs seek to recover

damages of defendants in their representative capacities as officers of

the State of Maine, their suit must be dismissed for want of jurisdiction,

both because it does not come within the purview of Section 1983 and

because it falls within the inhibition of the Eleventh Amendment.

Ill

Plaintiffs finally urge upon the Court the so-called Fair

Hearing" regulations promulgated by the United States Department of

Health. Education and Helfare and adopted by the State of Maine during

the pendency of this litigation, as authority for an award of retroactive

payments here. This contention does not require extended discussion

The "Fair Hearing” regulations provide for an award of

12/

12/ Only one of the cited cases, ^ompsOT V^ Shapiro, discusseSt^

— all the authority for an award of d“”^ ment of Employment v.

Court cites Ex parte Young, S L - j ' and sherbert v. Verner,

S a ^ S r h U i ) ^ 4 proposition that the Eleventh

Amendment is no barrier to/'If^court"?"conclusion that Ex parte at 338, n. 3. The basis of this Court s doncius^ ^

Young does not support such an aw states, it seems clear

As for Department of E^ 1°£'“ "La'Eietenth Amendment affords a

that the ^ uft by the S « d States. 385 U.S. at

state no immunity to a su y (1934). Sherbert v.

358. See Monaco v. Miss_ssippi, • • should also

Clarie^pecifically^dissented from this

aspect of Thompson. 270 F. Supp. at 3 .

13/ See note 5, supra.

18 -

benefits if, as a resuit of an administrative hearing, it is found that

. public assistance claimant was wrongfully refused payments. Plainly,

the regulations in question were designed to furnish an administrative

have been wrongfully denied public

remedy for those who, lxhe plaxntif

, do not purport to, nor could they effectively,assistance grants. They do nor i t

afford the basis for an award of retroactive benefits by this Court.

pnH n Snn v. Washington* su£ra; b q ^ ^ a p i r o , fi-UHra, Solman_v

supra. The problem is not, as plaintiffs seem to suggest, whet

who bas not exhausted an availabUstate administrative remedy ean

„ ♦• 1003 The question here is whether theestablish a claim under Section 1983. The qu

1 pan itself provide a toehold for a federal state administrative remedy can xtsel p

court suit. Clearly, it cannot.

* * * * *

Judgment will be entered for the defendants against the

, 1-stiffs’ Claims for damages, with prejudiceplaintiffs dismxssing plaintiffs

and without costs.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

, cti. Uth day of January 1970. n.rod at Portland, Maine, this IJtn aa>

js/ Edward T. Gignoux

14/

That exhaustion of state _ ̂ ^ ^rative^remedies fis^ ^ McSeese

le% Z r T o t Edufalion! 373 U.S. 668 (1963) and Damico v.

• California, 389 U.S. 416 (1967).

A true copy

Attest: jy

Morris (Cox, Clerk

By Pi orlf